Abstract

Morinda citrifolia L. (noni) is one of the most important traditional Polynesian medicinal plants. The primary indigenous use of this plant appears to be of the leaves, as a topical treatment for wound healing. The ethanol extract of noni leaves (150 mg kg−1 day−1) was used to evaluate the wound-healing activity on rats, using excision and dead space wound models. Animals were randomly divided into two groups of six for each model. Test group animals in each model were treated with the ethanol extract of noni orally by mixing in drinking water and the control group animals were maintained with plain drinking water. Healing was assessed by the rate of wound contraction, time until complete epithelialization, granulation tissue weight and hydoxyproline content. On day 11, the extract-treated animals exhibited 71% reduction in the wound area when compared with controls which exhibited 57%. The granulation tissue weight and hydroxyproline content in the dead space wounds were also increased significantly in noni-treated animals compared with controls (P < 0.002). Enhanced wound contraction, decreased epithelialization time, increased hydroxyproline content and histological characteristics suggest that noni leaf extract may have therapeutic benefits in wound healing.

Keywords: excision and dead space wound, hydroxyproline, Morinda citrifolia, wound healing

Introduction

Wound healing occurs in three stages: inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling. The proliferative phase is characterized by angiogenesis, collagen deposition, granulation tissue formation, epithelialization and wound contraction. In angiogenesis, new blood vessels grow from endothelial cells. In fibroplasia and granulation tissue formation, fibroblasts grow and form a new, provisional extracellular matrix by excreting collagen and fibronectin. Collagen, the major component which strengthens and supports extracellular tissue, contains substantial amounts of hydroxyproline, which has been used as a biochemical marker for tissue collagen (1). In epithelialization, epithelial cells proliferate and spread across the wound surface. Wound contraction occurs as the myofibroblasts contract. Platelets release growth factors and other cytokines (2). Chronic wounds are wounds that fail to heal despite adequate and appropriate care. Such wounds are difficult and frustrating to manage (3). Current methods used to treat chronic wounds include debridement, irrigation, antibiotics, tissue grafts and proteolytic enzymes, which possess major drawbacks and unwanted side effects.

Morinda citrifolia Linn (Rubiaceae), also known as noni or Indian mulberry, is a small evergreen tree. The leaves are 8–10 inches long oval shaped, dark green and shiny, with deep veins. Traditional Polynesian healers used parts of the plant for many purposes including bowel disorders (4). Morinda has been heavily promoted for a wide range of uses; including arthritis, atherosclerosis, bladder infections, boils, burns, cancer, chronic fatigue syndrome, circulatory weakness, colds, cold sores, congestion, constipation, diabetes, drug addiction, eye inflammations, fever, fractures, gastric ulcers, gingivitis, headaches, heart disease, hypertension, immune weakness, indigestion, intestinal parasites, kidney disease, malaria, menstrual cramps and irregularities, mouth sores, respiratory disorders, ringworm, sinusitis, sprains, stroke, skin inflammation and wounds (4,5). The primary indigenous use of this plant is leaves as a topical treatment for wound healing. Several animal studies suggest noni may have anti-cancer (6,7), immune-enhancing (8) and pain-relieving properties (9). Most recently Takashima et al. (10) demonstrated the medicinal uses of new constituents isolated from noni leaves (10). The crude leaf extract of noni has been used traditionally to promote wound healing. However, there are no experimental reports on wound-healing activities of noni in literature. In this article, we report for the first time, the efficacy of noni extract in the treatment of wounds.

Methods

Plant Material

Noni leaves were collected from Trinidad in April 2006 and identified by Mrs Yasmin S, plant taxonomist and curator, National herbarium of Trinidad and Tobago, The University of the West Indies, St Augustine, Trinidad. The voucher specimen was deposited at the herbarium (Specimen number: 36456).

Extraction

The noni leaves (200 g) were washed with water, air dried and powdered in an electric blender. Then 180 g of the powder was suspended in 200 ml of ethanol for 20 h at room temperature. The mixture was filtered using a fine muslin cloth followed by filter paper (Whatman No 1). The filtrate was placed in an oven to dry at 40°C. The clear residue obtained was used for the study. The extract was subjected to preliminary phytochemical analysis.

Phytochemical Screening Methods

Saponins

Extract (300 mg) was boiled with 5 ml water for 2 min; the mixture was cooled and mixed vigorously and left for 3 min. The formation of frothing indicates the presence of saponins (11).

Tannins

To 1 ml of extract (300 mg ml−1) was added to 2 ml of sodium chloride (2%), filtered and mixed with 5 ml 1% gelatin solution. Precipitation indicates the presence of tannins (11).

Triterpenes

Extract (300 mg) was mixed with 5 ml chloroform and warmed at 80°C for 30 min. Few drops of concentrated sulfuric acid was added and mixed well. The appearance of red color indicates the presence of triterpenes (12,13).

Alkaloids

Extract (300 mg) was digested with 2 M HCl, and the acidic filtrate was mixed with amyl alcohol at room temperature. Pink color of the alcoholic layer indicates the presence of alkaloids (13,14).

Flavonoids

The presence of flavonoids was determined by using 1% aluminum chloride solution in methanol, concentrated HCl, magnesium turnins and potassium hydroxide solution (11). The thin layer chromatography of the aqueous extract on silica gel was done using the medium chloroform: methanol (9:1 vol/vol) and chloroform: acetone (1:1 vol/vol) as the mobile phase.

Rats

Healthy inbred Sprague Dawley male rats weighing between 200 and 220 g were procured from the University of the West Indies, School of Veterinary Medicine, St Augustine, Trinidad. They were individually housed and maintained on normal food and water ad libitum. Animals were periodically weighed before and after experiments. All the animals were closely observed for any infection and those which showed signs of infection were separated and excluded from the study. Rats were randomly distributed into two groups of six for each model as follows.

Control group

This group of rats received plain drinking water orally.

Test group

This group of rats was provided with the extract (mixed in water) orally at a dose of 150 mg kg−1daily.

Animal Ethical Committee Approval

The study was carried out with prior approval of the animal Ethical Committee, Faculty of Medical Sciences, The University of The West Indies (AHC06/07/01).

Acute Toxicity Study

An acute toxicity study was conducted for the extract by the stair-case method (15). The rats of either sex were fed with increasing doses (1, 2, 4 and 8 g kg−1 body weight) of ethanol extract of noni dissolved in water for 14 days. The doses up to 4 g kg−1 body weight did not produce any sign of toxicity and mortality. The animals were physically active and were consuming food and water in a regular way.

Wound Healing Activity

Excision and dead space wound models were used to evaluate the wound-healing activity of noni.

Excision Wound Model

Animals were anesthetized prior to and during creation of the wounds, with intravenous ketamine hydrochloride (120 mg kg−1 body wt). The rats were inflicted with excision wounds as described by Morton and Malone (16). The dorsal fur of the animals was shaved with an electric clipper and the anticipated area of the wound to be created was outlined on the back of the animals with methylene blue using a circular stainless steel stencil. A full thickness of the excision wound of circular area of 300 mm2 and 2 mm depth was created along the markings using toothed forceps, scalpel and pointed scissors. The animals were randomly divided into two groups of six each. The control group animals were provided with plain drinking water. The test group rats were given extract orally in their drinking water at a dose of 150 mg kg−1daily until complete healing. Since an average rat consumes 110 ml of water kg−1 day−1, we dissolved 150 mg of extract in 100 ml of drinking water. The wound closure rate was assessed by tracing the wound on days 1, 5 and 11 postwounding using transparency paper and a permanent marker. The wound areas recorded were measured using graph paper. The day of eschar falling off, after wounding, without any residual raw wound was considered as the time until complete epithelialization.

Dead Space Wound Model

Dead space wounds were inflicted by implanting sterile cotton pellets (5 mg each), one on either side of the groin and axilla on the ventral surface of each rat by the technique of D’Arcy etal. as described by Turner (17). The animals were randomly divided into two groups of six each. The control group animals were provided with plain drinking water. The test group rats were given extract orally in their drinking water at a dose of 150 mg kg−1daily. On the 10th postwounding day, the granulation tissue formed on the implanted cotton pellets was carefully removed under anesthesia. The wet weight of the granulation tissue collected was noted. These tissues samples were dried at 60°C for 12 h and weighed to determine the dry granulation tissue weight. Dried tissue was added with 5 ml 6N HCl and kept at 110°C for 24 h. The neutralized acid hydrolysate of the dry tissue was used for the determination of hydroxyproline (18). Additional piece of wet granulation tissue was preserved in 10% formalin for histological studies.

Estimation of Hydroxyproline

Dry granulation tissue from both control and treated group were used for the estimation of hydroxyproline. Hydroxyproline present in the neutralized acid hydrolysate was oxidized by sodium peroxide in presence of copper sulfate, and subsequently complexed with p-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde to develop a pink color that was measured spectrophotometrically at 540 nm.

Histological Study

Granulation tissues obtained on day 10 from the test and control group animals were sectioned for histological study and stained for collagen with Van Gieson's stain.

Statistical Analysis

The means of wound area measurements at different time intervals, epithelialization period, wet and dry weight and hydroxyproline content of the granulation tissue between the test and control groups were compared using nonparametric Mann–Whitney U-tests. Data were analyzed using SPSS (Version 12.0, Chicago, USA) and P-value was set as <0.05 for all analysis.

Results

Phytochemical Analysis

The phytochemical analysis of the extract both by qualitative and thin layer chromatography showed the presence of phenols, alkaloids, triterpenoids, steroids and carboxylic acids.

Excision Wound Model

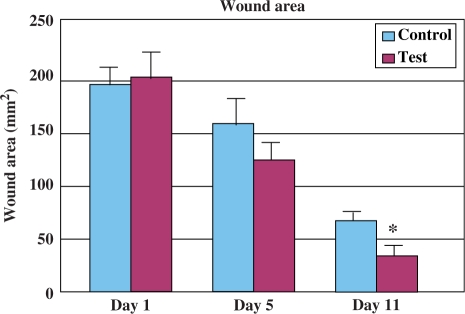

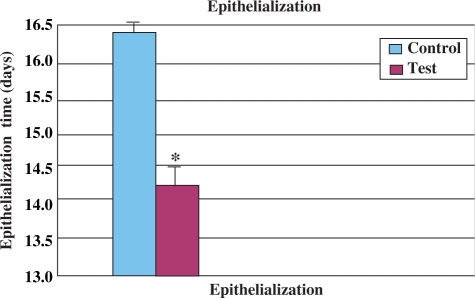

A significant increase in the wound-healing activity was observed in the animals treated with the noni extract compared with those who received the placebo control treatments. Figures 1 and 2 show the effect of the ethanolic extract of noni on wound-healing activity in rats inflicted with excision wound. In this model, the extract-treated animals showed a more rapid decrease in wound size (Fig. 1) and a decreased time to epithelialization (Fig. 2) compared with the control rats which received plain water.

Figure 1.

Wound-healing activity of Noni leaf extract in male rats in comparison withcontrol (excision wound model, n = 6). Each bar represents mean ± SE. *P < 0.002 versus control (nonparametric Mann–Whitney U-test).

Figure 2.

Epithelialization time of noni leaf extract-treated male rats in comparison withcontrol (excision wound model, n = 6). Each bar represents mean ± SE. *P < 0.002 versus control (nonparametric Mann–Whitney U-test).

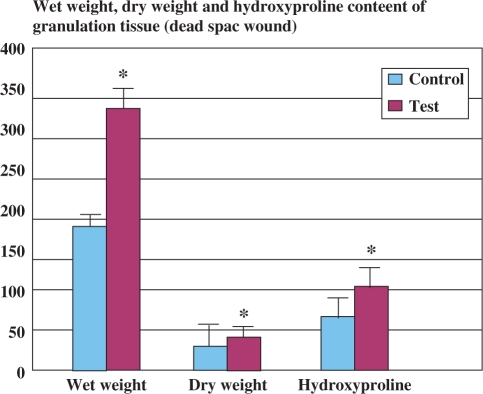

Dead Space Wound Model

In the dead space wound model, tissue from the extract-treated animals had significantly greater levels of hydroxyproline than animals in control group (P < 0.002). The weight of the granulation tissue in extract-treated rats also was significantly greater (P < 0.002) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Wet weight, dry weight and hydoxyproline content of the granulation tissue in comparison with control (dead space wound model, n = 6). Each bar represents mean ± SE. *P < 0.002 versus control (nonparametric Mann–Whitney U-test).

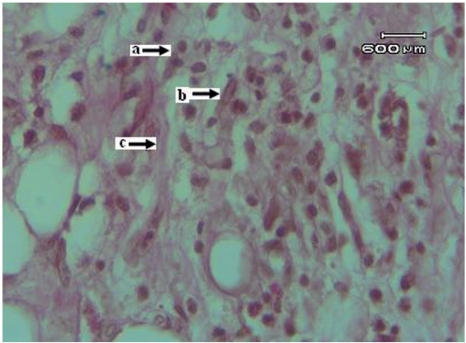

Histological Study

Histological sections of granulation tissue from extract-treated rats showed increased and well-organized bands of collagen, more fibroblasts and few inflammatory cells (Fig. 4). Granulation tissue sections obtained from control rats revealed more inflammatory cells and less collagen fibers and fibroblasts (Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

Histology of the granulation tissue obtained from the test group rats treated with noni extract (Van Gieson stain), a: macrophages, b: fibroblasts, c: collagen fibres.

Figure 5.

Histology of the granulation tissue obtained from the control rats received plain water (Van Gieson stain), a: macrophages, b: fibroblasts, c: collagen fibres.

Discussion

Wound healing is a process by which damaged tissue is restored as closely as possible to its normal state. Wound contraction is the process of shrinkage of the area of the wound. It is mainly dependent upon the type and extent of damage, the general state of health and the ability of the tissue to repair. The granulation tissue of the wound is primarily composed of fibroblasts, collagen and new small blood vessels. The undifferentiated mesenchymal cells of the wound margin differentiate into fibroblasts, which start migrating into the wound gap along with the fibrin strands.

Effect of Extract on Wound Healing

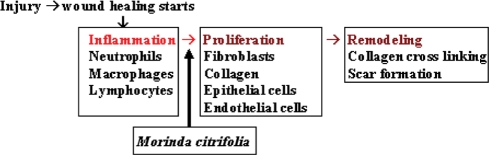

In our study, the ethanol extract of noni significantly increased the rate of wound contraction, the rate of epithelialization and weight of the granulation tissue. Granulation tissue formed in the final part of the proliferative phase is primarily composed of fibroblasts, collagen, edema and new small blood vessels. The increase in dry granulation tissue content of wounds in extract treated animals suggests higher collagen content. The constituents present in the noni extract may be responsible for promoting the collagen formation at the proliferative stage of wound healing (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

The schematic diagram showing the possible effect of the M. citrifolia leaf extract in promoting wound-healing activity.

Possible Role of Phytochemical Constituents of Noni on Wound Healing

Possibly, the constituents like triterpenoids and alkaloids of the noni may play a major role in the process of wound healing, however; further phytochemical studies are needed to find out the active compound(s) responsible for wound healing promoting activity. Triterpenoids and flavanoids are known to promote the wound-healing process mainly due to their astringent and antimicrobial property, which seems to be responsible for wound contraction and increased rate of epithelialization (19,20). Several studies, including our earlier work with other plant materials demonstrated the presence of similar phytochemical constituents which were responsible for promoting wound-healing activity in rats (21,22).

Conclusion

Our data demonstrate that the ethanolic extract of noni may be capable of promoting wound-healing activity. However, it needs further evaluation in clinical settings before consideration for the treatment of wounds.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their sincere thanks to Caribbean Health Research Council for funding this project. The authors are also grateful to The University of the West Indies, Faculty of Medical Sciences (St Augustine) Trinidad for the constant support and encouragement throughout this study. The authors sincerely thank Mrs S Yasmin for identifying and depositing the specimen at national herbarium, Trinidad and Tobago. We personally thank Mrs Simone Quintyne Walcott, Mr Mathew, Mrs Beverly Moore and Mr Vernie Ramkissoon for their technical assistance.

References

- 1.Kumar R, Katoch SS, Sharma S. β–Adrenoceptor agonist treatment reverses denervation atrophy with augmentation of collagen proliferation in denervated mice gastrocnemius muscle. Indian J Exp Biol. 2006;44:371–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawrence WT, Diegelmann RF. Growth factors in wound healing. Clin Dermatol. 1994;12:157–69. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(94)90266-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Falanga V. The Chronic wound; impaired wound healing and solutions in the context of wound bed preparation. Blood cells Mole dis. 2004;32:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2003.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elkins R. Hawaiian Noni (Morinda citrifolia) Pleasant Grove, UT: Woodland Publishing; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirazumi A, Furusawa E, Chou SC, Hokama Y. Immunomodulation contributes to the anticancer activity of Noni (noni) fruit juice. Proc West Pharmacol Soc. 1996;39:7–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McClatchey W. From Polynesian healers to health food stores: changing perspectives of Morinda citrifolia (Rubiaceae) Integr Cancer Ther. 2002;1:110–20. doi: 10.1177/1534735402001002002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirazumi A, Furusawa E. An immunomodulatory polysaccharide-rich substance from the fruit juice of Noni(noni) with antitumour activity. Phytother Res. 1999;13:380–7. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1573(199908/09)13:5<380::aid-ptr463>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hiramatsu T, Imoto M, Koyano T, Umezawa K. Induction of normal phenotypes in ras-transformed cells by damnacanthal from Morinda citrifolia. Cancer Lett. 1993;73:161–66. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(93)90259-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Younos C, Rolland A, Fleurentin J, Lanhers MC, Misslin R, Mortier F. Analgesic and behavioral effects of Morinda citrifolia. Planta Med. 1990;56:430–34. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-961004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takashima J, Ikeda Y, Komiyama K, Hayashi M, Kishida A, Ohsaki A. New constituents from the leaves of Morinda citrifolia. Chem Pharm Bull. 2007;55:343–5. doi: 10.1248/cpb.55.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kapoor LD, Singh A, Kapoort SL, Strivastava SN. Survey of Indian medicinal plants for saponins. Alkaloids and flavonoids. Lloydia. 1969;32:297–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Said IM, Din LB, Samsudin MW, Zakaria Z, Yusoff NI, Suki U, et al. A phytochemical survey of Uku Kincin, Pahang, Malaysia. Mal Nat J. 1990;43:260–66. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harborne JB. Photochemical Methods: A Guide to Modern Techniques of Plant Analysis. London: Chapman A & Hall; 1973. p. 279. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trease GE, Evans WC. A Text-book of Parmacognosy. London: Bailliere Tinall Ltd; 1989. p. 53. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jalalpure SS, Patil MB, Prakash NS, Hemalatha K, Manvi FV. Hepatoprotective activity of fruits of Piper longum L. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2003;65:363–6. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morton JJ, Malone MH. Evaluation of vulnerary activity by an open wound procedure in rats. Arch. Int. Pharmacodyn. 1972;196:117–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turner RA. Inflammatory agent in screening methods of pharmacology. 2nd. New York: Academic press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neuman RE, Logan MA. The determination of hydroxyproline. J Biol Chem. 1950;184:299–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scortichini M, Pia Rossi M. Preliminary in vitro evaluation of the antimicrobial activity of triterpenes and terpenoids towards Erwinia amylovora (Burrill) J Bacteriol. 1991;71:109–12. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsuchiya H, Sato M, Miyazaki T, Fujiwara S, Tanigaki S, Ohyama M, et al. Comparative study on the antibacterial activity of phytochemical flavanones against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Ethnopharmacol. 1996;50:27–34. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(96)85514-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nayak BS. Cecropia peltata L (Cecropiaceae) has wound healing potential-a preclinical study in Sprague Dawley rat model. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2006;5:20–26. doi: 10.1177/1534734606286472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haque MM, Rafiq, Sherajee S, Ahmed Q, Hasan, Mostofa M. Treatment of external wounds by using indigenous medicinal plants and patent drugs in guinea pigs. J Biol Sci. 2003;3:1126–33. [Google Scholar]