Abstract

The Arabidopsis sog1-1 (suppressor of gamma response) mutant was originally isolated as a second-site suppressor of the radiosensitive phenotype of seeds defective in the repair endonuclease XPF. Here, we report that SOG1 encodes a putative transcription factor. This gene is a member of the NAC domain [petunia NAM (no apical meristem) and Arabidopsis ATAF1, 2 and CUC2] family (a family of proteins unique to land plants). Hundreds of genes are normally up-regulated in Arabidopsis within an hour of treatment with ionizing radiation; the induction of these genes requires the damage response protein kinase ATM, but not the related kinase ATR. Here, we find that SOG1 is also required for this transcriptional up-regulation. In contrast, the SOG1-dependent checkpoint response observed in xpf mutant seeds requires ATR, but does not require ATM. Thus, phenotype of the sog1-1 mutant mimics aspects of the phenotypes of both atr and atm mutants in Arabidopsis, suggesting that SOG1 participates in pathways governed by both of these sensor kinases. We propose that, in plants, signals related to genomic stress are processed through a single, central transcription factor, SOG1.

Keywords: Arabidopsis, ATM, ATR, checkpoint response, XPF

DNA damage and replication blocks induce a variety of programmed responses in bacteria, fungi, animals, and plants. In eukaryotes, recognition of persisting ssDNA, stalled replication forks, and double-strand breaks (DSBs) occurs through the actions of 2 phosphotidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)-related protein kinases: ATM and ATR (1, 2). These sensor kinases trigger the activation, stabilization, or degradation of a number of transducer and effector proteins. Acting in concert, damage response regulators affect the progression of the cell cycle, the activity of repair proteins, and, in animals, senescence and/or apoptosis. Many of the molecules (the sensors, transducers, and effectors) required for damage response are conserved in all model eukaryotes. Animals (vertebrates, insects, and worms) possess a critical transcription factor, p53, that governs most aspects of the cell's response to damage. Because p53 can be modified in many ways and interacts with a variety of protein cofactors, it can integrate a number of environmental signals (as well as signals related to DNA metabolism) to produce a response appropriate to the cell's developmental state (3). p53 homologs can be traced back in the animal lineage as far as the unicellular Choanoflagellates (4), although neither the expression nor the function of these distant homologs has been investigated. p53 homologs have not been identified in yeasts or plants. Although the regulation of damage response has been abundantly characterized in model yeasts (Schizosaccharomyces pombe and Saccharomyces cerevisiae), these fungi lack any known single transcription factor that governs the majority of the transcriptional response to DNA damage (5). Thus, although the sensors and many of the transducers and effectors are conserved between fungi and animals, the model yeasts appear to lack that additional layer of integration and regulation that is provided by p53 in animals. It has been hypothesized that yeasts do not possess a p53-like regulator because of the lack of an apoptotic DNA damage response in these single-celled organisms; this critical and lethal response would be expected to be kept under particularly stringent environmental and developmental control, and thus may require this additional integrating regulatory factor.

Plants, like yeasts, possess functional homologs of most of the DNA-repair and damage-response genes of animals. In plants, as in animals, double-strand breaks are sensed by ATM, and stalled replication forks are detected by ATR (1, 2), although it must be kept in mind that these 2 lesions, once generated, can be processed into alternative forms that are detected by the alternate sensor kinase (i.e., resection of a break, or collapse of a replication fork). Plant homologs of the genes encoding the 9-1-1 (Rad9/Rad1/Hus1) sensor complex have been identified (6) and are required for resistance to DNA damaging agents. Arabidopsis exhibits the robust induction of a variety of transcripts in response to ionizing radiation, and this response is entirely dependent on the presence of ATM (7, 8). Arabidopsis also exhibits programmed responses to DNA polymerase poisons, crosslinking agents, depletion of nucleotides, ionizing radiation (IR), and to the persistence of DNA damage products in repair-defective backgrounds (9, 10).

We have previously described the isolation of a mutant (suppressor of gamma response1, sog1-1) defective in the programmed developmental arrest observed in gamma-irradiated xpf and ercc1 seeds (11). After irradiation at 100 Gy, seeds defective in the XPF/ERCC1 repair endonuclease exhibit normal germination, cell expansion, and light response. However, they experience a transient arrest of cell division at the apical meristem, and so exhibit an ≈8 day delay in the production of true leaves, after which plants continue to develop normally. Mutants defective in the XPG endonuclease, which (like ercc1 and xpf mutants) are deficient in NER, do not exhibit this response, indicating that the response is not induced by a defect in NER. In mammals, the XPF/ERCC1 endonuclease, unlike XPG, plays an important role in interstrand crosslink repair (12, 13). It is possible that the developmental arrest observed may be triggered by the persistence of this replication-blocking lesion. Here, we show that this arrest requires the protein kinase ATR, but not ATM, consistent with the notion that this 8 day IR-induced developmental arrest is a response to a replication-blocking lesion, rather than to a frank break.

Here, we clone the SOG1 locus and find that it encodes a member of a very large, plant-specific family of putative transcription factors, termed NAC domain [petunia NAM (no apical meristem) and Arabidopsis ATAF1,2 and CUC2] proteins. We find that the sog1-1 mutant, like atm mutants (but not atr mutants), is defective in the rapid (1.5-h peak) and robust transcriptional induction response to IR observed in repair-proficient seedlings. The dependence of the transcriptional induction response on ATM, but not ATR, indicates that SOG1 participates in signaling pathways governed by both ATR and ATM. Based on this evidence, we suggest that plants, like animals, direct the flow of information related to damage response through a central regulatory transcription factor.

Results

Identification of the SOG1 Gene Sequence.

sog (suppressor of gamma response) mutants were originally isolated as recessive suppressors of the transient (8 day) growth arrest induced by gamma radiation in Arabidopsis mutants defective in the excision repair endonuclease XPF. The specific lesion(s) that induce this response have not been identified. To gain insight into the biochemical function of the SOG1 gene product, we used a map-based cloning approach to isolate the SOG1 locus. Mapping of recombination breakpoints localized the SOG1 locus to a 45-Kb region between nucleotides 8,976,528 and 9,021,427 of chromosome 1. Sequencing of the 8 predicted ORFs within this interval revealed a single base change (G to A) at the At1g25580 locus. Transformation of the xpf-2 sog1-1 mutant with a cloned wild-type (Col) genomic copy of the At1g25580 locus, carrying the ORF plus 1840 bp of upstream sequence, resulted in complementation of the sog phenotype, restoring both the gamma sensitivity characteristic of xpf−/− SOG1+/+ seeds and the transcriptional induction response to IR (discussed below) (SI Text, Fig. S1, and Table S1).

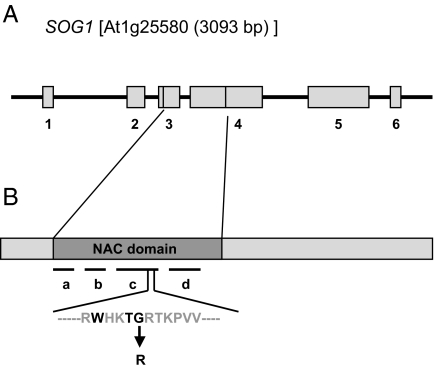

The coding sequence of SOG1 consists of 6 exons and 5 introns (Fig. 1A). Four independently derived full-length cDNA sequences from this gene are available online (http://signal.salk.edu/cgi-bin/tdnaexpress). All of these sequences share the same splicing pattern, although both the 5′-UTR and 3′-UTR were variable; thus the gene model is well supported. This locus is predicted to encode one of the 105 NAC domain transcription factors encoded in the Arabidopsis genome (14). No other motifs were recognized. The sog1-1 mutant carries a missense mutation affecting a highly conserved amino acid in the NAC domain, changing Gly (GGA)-155 to Arg (AGA) (Fig. 1B). The few NAC domain transcription factors that have been investigated have been found to regulate functions ranging from developmental patterning to response to environmental stress (14). Members of the NAC protein family are not present in the unicellular eukaryotic green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii or the colonial Volvox carteri, but are present in a wide range of land plants ranging from the moss Physcomitrella patens to flowering plants. Clear SOG1 homologs can be identified in most land plants (Fig. S2), but we do not know whether the function of the SOG1 gene is conserved in these species.

Fig. 1.

Structure of the SOG1 gene. (A) Intron-exon organization of the SOG1 gene. Numbered gray boxes represent exons, lines indicate introns. (B) cDNA structure shows the location of the highly conserved NAC domain. Conserved subdomains are indicated by a–d. A conserved Gly was changed into Arg in the sog1-1 mutant.

Effect of SOG1 on the Transcriptional Induction Response to Gamma Radiation.

We previously reported that the expression of hundreds of genes is up-regulated in response to gamma irradiation in wild-type Arabidopsis (expression of the SOG1 gene itself is not induced by IR) (7). Given that SOG1 appears to encode a transcription factor, we used microarray analysis to determine what fraction of the transcriptional induction response depended on SOG1. Wild-type [Columbia (Col)/Ler (Landsberg erecta) CYCB1;1:GUS] and sog1-1 mutant (Col/Ler CYCB1;1:GUS) 5-day-old seedlings were irradiated at 100 Gy. RNA was prepared 1.5 h after the completion of irradiation. Table 1 displays the 30 transcripts that were most highly induced (14- to 66-fold) in wild-type plants. Strikingly, the irradiated sog1-1 seedlings were almost completely defective in induction of gene expression by IR. The 249 of 282 genes induced in the wild-type control [with a percentage of false prediction (pfp) value < 0.1] were not induced in the sog1-1 mutant (Table S2). Of the 33 transcripts that were significantly gamma-induced in the sog1-1 line, 14 were still dependent to some degree on SOG1, as they were induced to less than half their SOG1+ value. This result indicates that the great majority of the transcriptional activation response to gamma irradiation is regulated through SOG1. This aspect of the sog1-1 mutant phenotype is very similar to that of the atm mutant, which is also required for the transcriptional induction response to gamma irradiation at 1.5 h (7, 8); all of the genes that require SOG1 for their transcriptional induction also require ATM for their full induction. However, 9 of 249 of these SOG1-dependent transcripts were partially induced in our atm−/− line (7).

Table 1.

sog1–1 displays a severe defect in the induction of a variety of genes by γ-radiation

| Locus identifier | Annotation | Wild-type, 100 Gy | sog1-1, 0 Gy | sog1-1, 100 Gy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT5G48720 | Unknown protein | 66 | - | - |

| AT4G02390 | APP | 59 | - | - |

| AT4G21070 | BRCA1 | 58 | - | - |

| AT5G24280 | ATP binding | 43 | - | - |

| AT5G60250 | Zinc finger family protein | 40 | - | - |

| AT1G07500 | Unknown protein | 36 | - | - |

| AT3G10930 | Unknown protein | 35 | - | - |

| AT5G55490 | GEX1 | 35 | - | - |

| AT5G20850 | RAD51 | 31 | - | - |

| AT3G50930 | AAA-type ATPase family protein | 30 | - | - |

| AT5G40840 | SYN2 | 27 | - | - |

| AT5G03780 | TRFL10 | 23 | - | - |

| AT2G45460 | FHA domain-containing protein | 21 | - | - |

| AT5G02220 | Unknown protein | 21 | - | - |

| AT3G07800 | Thymidine kinase, putative | 20 | - | - |

| AT5G39670 | Calcium-binding EF hand family | 19 | - | 3 |

| AT5G23910 | Microtubule motor | 19 | - | - |

| AT4G37290 | Unknown protein | 18 | - | 2.6 |

| AT3G25250 | AGC2-1 | 18 | - | - |

| AT2G47680 | Zinc finger helicase family protein | 18 | - | - |

| AT5G67460 | Glycosyl hydrolase family protein 17 | 17 | - | - |

| AT5G11460 | Senescence-associated protein-related | 17 | - | - |

| AT4G29170 | ATMND1 | 17 | - | - |

| AT5G18470 | Curculin-like lectin family | 16 | - | - |

| AT4G37490 | CYCB1;1 | 15 | - | - |

| AT4G22960 | Unknown protein | 14 | - | - |

| AT3G45730 | Unknown protein | 14 | - | - |

| AT4G25330 | Unknown protein | 14 | - | - |

| AT3G60420 | Unknown protein | 14 | - | - |

| AT5G64060 | ANAC103 transcription factor | 14 | - | - |

Five-day-old seedlings were irradiated at 100 Gy and harvested 1.5 h after the end of the irradiation period. Number shown here is normalized fold-change with respect to unirradiated wild-type. All values shown are significant (pfp) value is < 0.1). This table shows the top 30 gamma-induced genes. “-” = no significant change in expression.

The Effect of the sog1-1 Defect on IR-Induced Suppression of 2 Cell-Cycle-Related Transcripts.

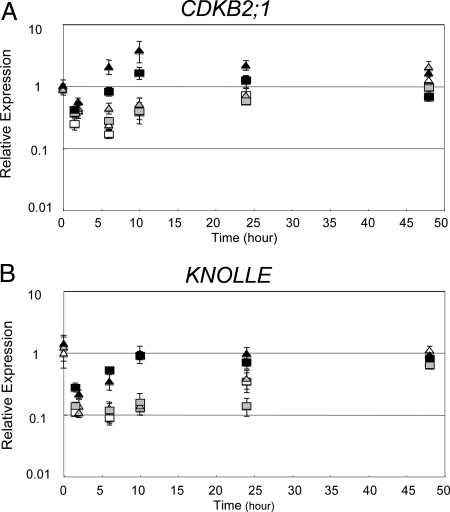

Irradiation of Arabidopsis inhibits the expression of genes that promote progression through the cell cycle. Full suppression of these transcripts has been previously shown to depend on both ATM and ATR; mutations in one or the other signal transduction kinase result in only partial suppression of the IR-induced down-regulation of these transcripts (7). Given the xpf-2 sog1-1 mutants' gamma-resistant growth phenotype, one would expect that irradiated xpf-2 sog1-1 seedlings would exhibit gamma-resistant expression of cell-cycle-related genes. We used QRT-PCR to measure the expression of CDKB2;1 (a G2 associated transcript encoding a protein required for progression from G2 to M) and KNOLLE (a G2/M transcript encoding a protein required for cytokinesis) in 5-day-old wild-type (Ler), xpf- 2, and xpf-2 sog1-1 seedlings, over a 2-day period after irradiation at 100 Gy. As shown in Fig. 2, at 1.5 h after irradiation, CDKB2;1 and KNOLLE transcripts are suppressed by 3- to 10-fold in wild-type and xpf-2 seedlings (white and gray symbols, respectively), and this suppression is completely alleviated within 24 h after irradiation. In the xpf-2 sog1-1 mutant (black symbols), suppression of CDKB2;1 and KNOLLE does occur at 1.5 h after irradiation, but the plants recover more quickly, by 6 h and 10 h after irradiation, respectively. These observations suggest that xpf-2 sog1-1 mutants are impaired in the transcriptional component of IR-induced cell-cycle arrest in seedlings.

Fig. 2.

Expression levels of G2 (CDKB2;1) and M (KNOLLE) phase transcripts after gamma-irradiation. Five-day-old seedlings were irradiated and then harvested for RNA preparation at the indicated times. All values were normalized to the expression level of ElF4A-1. Results are reported relative to the expression level in the 0-h untreated wild-type sample. Error bars indicate the standard deviation for technical triplicates. (A) CDKB2;1 expression. (B) KNOLLE expression. White, gray, and black symbols indicate wild-type, xpf-2, and xpf-2 sog1-1, respectively. Triangles and squares show biological repeats #1 and #2. Unirradiated controls are shown in Fig. S5.

H2AX γ-Phosphorylation in the sog1-1 Mutant.

We have previously demonstrated that the transcriptional induction response to 100 Gy at 1.5 h after gamma irradiation depends on ATM. One simple explanation for the lack of IR-induced transcriptional activation in sog1-1 mutants might be a lack of functional ATM protein. For example, SOG1 might be required for the transcription of ATM. However, our microarray experiments indicate that ATM (and ATR) transcripts are expressed at normal levels in sog1-1 mutants. Alternatively, SOG1 may be required for the expression of another protein involved in activation of ATM kinase activity. To determine whether the ATM kinase could be functionally activated in sog1-1 mutants, we assayed the phosphorylation of γ-H2AX after gamma irradiation. In mammals, the histone variant H2AX is rapidly phosphorylated to form γ-H2AX at the site of DSBs; this event helps to stabilize and transmit signals to downstream target proteins. In plants, γ-phosphorylation of H2AX occurs within 20 min of irradiation and is largely dependent on ATM (15). To determine whether SOG1 is required for the phosphorylation of H2AX in response to IR, we examined γ-H2AX formation in xpf-2 sog1-1 plants via immunoblotting. We observed equal levels of IR-dependent γ-H2AX formation in wild-type, xpf-2, and xpf-2 sog1-1 lines (Fig. S3). This indicates that SOG1 is not required for ATM activation. This result is consistent with a model in which the ATM protein kinase activity is activated by IR-induced DNA damage and subsequently works with SOG1 to induce IR-responsive target genes.

A Defect in ATR, but Not in ATM, Phenocopies the Radioresistant-Growth Phenotype of the xpf sog1-1 Double Mutant.

The observations described above suggest that ATM, once activated by DNA damage, directly or indirectly activates SOG1, which then regulates the expression of target genes. However, a second observation suggests that SOG1 may also respond to, or act in concert with, additional regulatory factors. For example, ATR encodes a protein kinase closely related to ATM. Whereas ATM is activated by double-strand breaks, ATR is activated, through adaptor proteins, by ssDNA. The function of ATR as a sensor for replication blocks is conserved in Arabidopsis (10). ATR is often said to be associated with long-term responses to IR and ATM to be associated with short-term responses. Although this model is a simplification, it is probably correct to say that ATM responds to the breaks induced directly by ionizing radiation, wheras ATR responds to damage detected over the long term, as the (unsynchronized) population of plant cells gradually progresses from G1 to S phase and encounters lesions that result in replication fork arrest or collapse. Thus, a “long-term” response reflects both the time required to repair a response-inducing lesion and the time required to detect it. The requirement for ATR, but not ATM, for longer-term responses to gamma radiation in Arabidopsis has already been established (7).

xpf seedlings grown from irradiated seeds, although healthy and normal in morphology, experience an 8-day delay in the onset of meristematic cell division and so exhibit an 8-day delay in the production of postembryonic leaves (16). This tissue-specific G2 arrest, without other deleterious effects on growth, is probably induced by a replication-blocking lesion (such as a crosslink) that specifically requires the XPF/ERCC1 endonuclease for its repair, as it is not observed at any dose of gamma radiation, in seedlings grown from wild-type, xpg−/−, lig4−/−, or ku−/− seeds (16, 17). Not unexpectedly, considering its relatively long-term nature, this delay depends on ATR, not ATM (Table 2 and Fig. S4). Given the fact that this tissue-specific arrest does not require ATM, does require ATR, and also requires SOG1, we can therefore conclude that, in this case, SOG1 is responding primarily to the activation of ATR, rather than the activation of ATM. Thus, SOG1 can act in concert with either of the 2 damage-sensor kinases.

Table 2.

Requirements for gamma-resistant growth after irradiation of xpf seeds

| Line | Genotype | Fraction γ-resistant | % γ-resistant |

|---|---|---|---|

| KY364 | Wild type | 26:26 | 100 |

| KY415 | xpf-2 | 0:22 | 0 |

| KY474 | xpf-2 sog1-1 | 25:27 | 93 |

| KY494–5 | xpf-2 atm-2 | 1:26 | 4 |

| KY494–43 | xpf-2 atm-2 | 2:28 | 7 |

| KY368 | xpf-2 atr-4 | 21:22 | 95 |

| KY516–21 | xpf-2 sog1-1 atm-2 | 19:19 | 100 |

| KY516–23 | xpf-2 sog1-1 atm-2 | 22:22 | 100 |

Imbibed seeds were gamma-irradiated with 100 Gy, or left untreated, then sown on MS plates and grown for 9 days. The number of plants that are gamma-resistant (plants having one or more true leaves) and gamma-sensitive (plants with no true leaves) was scored by eye. All unirradiated seedlings formed true leaves.

Gamma-Induced Loss of Heterozygosity (LOH).

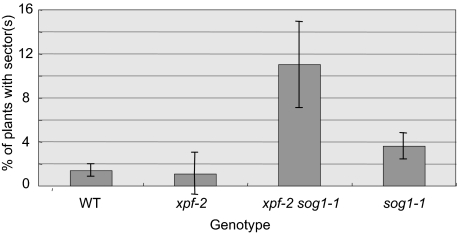

Given that sog1-1 lacks the robust transcriptional induction response to IR and is defective in aspects of checkpoint activation, it is of interest to determine whether the transcriptional response to IR in plants has a significant effect on radioresistance. sog1-1 seedlings do not exhibit hypersensitivity to the effects of radiation on either root growth or the rate of production of true leaves. In contrast, they are hypersensitive to the effects of radiation on genetic stability. Plants heterozygous for a recessive defect in the APG3 (Albino/pale green) locus were used to measure the rate of somatic LOH after irradiation as seeds. In these plants, loss of the wild-type APG3-locus results can be scored as the formation of an albino sector. We determined the effect of 100-Gy irradiation on the rate of LOH in wild-type, sog1-1, xpf, and xpf-2 sog1-1 lines (Fig. 3). We found that, both in combination with xpf and as a single mutant, the sog1-1 defect significantly enhanced the rate of gamma-induced LOH. Thus, the transcriptional response to IR contributes to the maintenance of genetic stability after irradiation at 100 Gy.

Fig. 3.

Loss of heterozygosity in response to gamma irradiation. Wild-type, xpf-2, xpf-2 sog1-1, and sog1-1 seeds carrying a heterozygous albino mutation were gamma irradiated (100 Gy) and scored for the number of plants with sector(s) (because of the loss of the wild-type APG3 allele). Error bars indicate the standard deviation for biological triplicates of 100 plants each for each genotype. No sectors were observed in unirradiated controls or in APG3+/+ plants.

Discussion

The sog1-1 mutant was isolated as a suppressor of IR sensitivity in the DNA repair defective xpf mutant: xpf sog mutants irradiated as seeds exhibited radio-resistant leaf production (vs. mutants carrying the xpf mutation alone) (11). Consistent with a defect in a damage-induced checkpoint response, xpf sog mutants also exhibit enhanced IR-induced loss of heterozygosity vs. xpf single mutants. The molecular nature of the SOG gene has not been previously described. Here, we find that SOG1 (At1g25580) encodes one of the 105 members of the Arabidopsis NAC domain family of proteins. These proteins are putative transcription factors, and the NAC domain family of proteins is restricted to land plants. Thus, SOG1 is a regulator of damage response that is unique to plants.

Treatment of Arabidopsis seedlings with clastogenic agents induces the expression of many transcripts (7, 8, 18). At a dose of 100 Gy, this induction, for most genes, peaks at ≈1.5 h after irradiation, and has a half life of ≈4 h. This up-regulation of gene expression in response to IR depends on ATM (but not ATR), and therefore probably reflects a response to the induction of DSBs rather than some other IR-induced lesion. Here, we show that the sog1-1 mutant is defective in the induction of 249 of 282 of these transcripts, indicating that SOG1 is required for this clastogen-specific transcriptional up-regulation. The SOG1-dependent expression of several other transcription factors (Table 1, SI Text) indicates that SOG1 induces a cascade of transcriptional regulators that work together to determine the extent of the cell's response to IR. The promoters that are direct targets of SOG1, as opposed to the targets of other transcription factors that are themselves induced by IR in a SOG1-dependent manner, remain to be determined. It is also possible that SOG1 does not act alone and that other transcription factors may be required to initiate this response.

Expression of the ATM transcript is not affected either by IR or by the sog1-1 mutation (SI Text). Similarly, the sog1-1 defect does not impede the activation of the ATM protein kinase in response to ionizing radiation; IR-induced H2AX gamma phosphorylation, which depends on ATM in Arabidopsis (15), appears to occur normally in the sog1-1mutant. Thus, SOG1-1 does not play a role in the activation of ATM kinase activity. Given that both ATM and SOG1 are required for the transcriptional induction response, these 2 proteins may act sequentially or simultaneously to activate transcription. A simple, but unproven, model would therefore be that constitutively expressed SOG1 protein is functionally activated in response to the activation of the ATM kinase. The SOG1 amino acid sequence has an SQ motif that could act as a substrate for ATM (or ATR) kinase activity.

In addition to the very robust and relatively short-term induction of transcripts observed in irradiated seedlings, a smaller set of genes is suppressed by IR treatment (7, 8). Many of these transcripts are predicted to encode proteins that drive cell-cycle progression. The suppression of these cell-cycle-related transcripts probably reflects cell-cycle arrest. The suppression of these genes follows a different time course than the activation response described above; the suppression occurs relatively slowly, and persists longer, than the induction response. However, in wild-type seedlings irradiated at 100 Gy, the levels of transcript are back to normal within 24 h of irradiation. Not surprisingly, given its radioresistant growth phenotype (in the xpf double mutant), the sog1-1 defect also affects IR-induced suppression of at least 2 transcripts associated with cell-cycle progression. In otherwise wild-type lines, both ATM and ATR were previously shown to be required for the suppression of these cell-cycle-associated transcripts; defects in either protein partially restored expression of 4 genes investigated (7). sog1-1mutants, like atr and atm lines, exhibit a partial defect in the IR-induced suppression of CDKB2;1 and KNOLLE. In this case, we do not know whether SOG1 acts in concert with ATM, ATR, neither protein, or both proteins.

It is clear that SOG1 is a required participant in ATM-dependent signal transduction during the transcriptional induction response to IR. This observation raises the question of whether SOG1 can act independently of ATM. ATM is not required for the suppression of leaf formation in seedlings grown from irradiated xpf seeds. ATR, however, is required: xpf atr mutants exhibit a “sog” phenotype. Thus, in this example, SOG1 functions in conjunction with ATR, not ATM, to induce cell-cycle arrest in xpf seedlings grown from irradiated seeds. Again, a simple model would suggest that SOG1 is activated in response to the activation of ATR by some replication-blocking lesion. And once again, it remains to be determined how, and even if, SOG1 protein is “activated.” Although the protein carries many potential modification sites, it is possible that it is not modified at all, and instead requires the presence of modified partner protein, which is itself activated by IR.

SOG1 Is Unique to Plants.

SOG1 plays an important role in cell-cycle response to gamma radiation. This single transcription factor is required for the induction of hundreds of transcripts in response to gamma radiation. The set of genes induced by DNA damage in plants does not resemble the set induced by a variety of other types of environmental stresses (7, 8), and the ATM-dependence of this response suggests that it is induced directly by DNA damage, rather than by the deleterious effects of either mutagenesis or damage to targets other than DNA. Bacteria, like plants, possess a robust transcriptional response to DNA damage (the SOS response) that is governed through the activation of a single protein (the RecA protease). Although genes required for some aspects of transcriptional response to IR (including one encoding a transcriptional repressor) have been identified in yeast (5, 19), this single-celled eukaryote appears to lack a single transcription factor that acts as a “master regulator” of IR response. In contrast, p53 appears to be required for the majority of the transcriptional response to IR in the early drosophila embryo (20). The extent of the contribution of p53 to the transcriptional response to IR in mammalian tissues varies (no doubt in part because of variation in experimental design) (21, 22), and other transcription factors also play major roles (23, 24). However, p53 clearly regulates the critical choice between apoptosis, cell-cycle arrest, and cell-cycle progression.

The mammalian response to DNA damage is largely, although not exclusively, governed by p53 in animals. In mammals, the subcellular location, stability, and even the set of target genes for p53 are determined not only by the persistence of DNA damage, but also by tissue type (3). Here, we demonstrate that plants, like animals, possess a transcription factor required for the transcriptional response to ionizing radiation. This transcription factor is unrelated to p53 and seems to have appeared only after the origin of multicellularity in plants. It is interesting that whereas the most proximal detectors of DNA damage (ATM, ATR, and their homologs) have been conserved in plants, animals, and fungi, the transcriptional regulators have not. This lack of conservation may reflect the fact that the appropriate response to DNA damage, whether the cell should choose to arrest (or die) to preserve genomic integrity, will vary with the developmental strategy of the organism and with the nature of the tissue type. Although the response of a unicellular species to DNA damage is elaborate and sophisticated, the response of a complex organism carrying many different tissue types may require yet another level of coordination and differentiation of response between cell types to maximize reproductive success. It will be interesting to determine whether in plants, as in mammals, this regulator of transcriptional response can be differentially modified to induce the particular mode of damage response that is most appropriate for each tissue type.

Materials and Methods

Arabidopsis Strains.

We used Ler (Landsberg erecta), Col (Columbia), and Ler/Col hybrid backgrounds as “wild-type.” xpf-2 (= uvh1-2) and xpf-2 sog1-1 mutants were isolated in the Ler background in our lab (11, 25). Here, we used a xpf-2 sog1-1 line, which is a Ler/Col hybrid, which happens to carry cycB1;1:GUS (11). Our own microarray transcriptional experiments indicate that there is no significant different in transcriptional induction response to IR in the cycB1;1:GUS Col/Ler hybrid vs. a pure Col line. Our LOH assay was performed in these lines, into which we introduced a recessive allele of APG3 (At3g62910) derived from Arabidopsis stock CS16118 and acquired from the Arabidopsis Stock Center. This allele carries Basta resistance, and uniformly heterozygous populations can be selected as photosynthetic, Basta-resistant seedlings.

Double Mutant Generation: Detection of Wild-Type and Mutant Alleles.

Isolation of double mutants (xpf-2 atr-4, xpf-2 atm-2) and the primers used to genotype these lines are described in SI Text and Table S3.

Growth and Gamma-Irradiation of Arabidopsis.

Plants were grown on either soil (Sunshine Mix #1; Sungro) or 1 × MS (SIGMA) Phytoagar (PlantMedia), pH 6.1. Cool-white lamps filtered although UV-absorbing protective sleeves (Clear UV-filtering Protect-o-sleeves, cutoff 385 nm; McGill Electrical Product Corp.) were used as a light source, with a 16-h day and 8-h night at 20 °C. When grown on plates, seeds were sterilized in 20% bleach solution, washed, and imbibed in ddH2O for 2–4 days at 4 °C. Arabidopsis seeds and 5-day-old seedlings were gamma-irradiated by using a 137Cs source (Institute of Toxicology and Environmental Health, University of California, Davis, CA) at a dose rate of 6.9 Gy/min. For irradiation of seeds, sterilized seeds were imbibed in water at 4 °C for 2 days, irradiated, sown on 1 × MS plates, and placed in the growth chamber. For irradiation of seedlings, sterilized seeds were imbibed in water for 2 days at 4 °C, grown on MS plates for 5 days in the growth chamber, all plates (including unirradiated controls) transported to the irradiation site (on campus), then returned to the growth chamber. Irradiations occurred between the first and second hours of the seedlings' subjective dawn.

Quantitative RT-PCR.

Seedlings were grown on MS plates for 5 days, then either gamma-irradiated at 100 Gy, or not irradiated, as a control. Whole seedlings were harvested at the times indicated. Plants (≈50–80) were harvested and pooled together for each total RNA extraction (RNeasy MiniPrep; Qiagen). Technical details and primers used are provided in Table S3 and SI Text.

Affymetrix ATH1 GeneChip Analysis.

Duplicate batches of 5-day-old wild-type seedlings containing cycB1;1:GUS (Ler/Col hybrid) and sog1-1 (Ler/Col hybrid) mutant were gamma-irradiated with 100 Gy, or left untreated, and harvested for total RNA preparation 1.5 h after irradiation (unirradiated plants were also harvested at this time). Details of RNA preparation, cRNA production, hybridization, and statistical analysis are provided in SI Text.

Histone Extraction and Immunoblotting.

Plants for histone extraction were planted on soil, kept at 4 °C for 2 days, and then transferred to the growth chamber. Two-week-old plants were irradiated at 100 Gy with 137Cs source. Plants were harvested at 15 min after the completion of irradiation, placed into liquid nitrogen, and then stored at −80 °C until protein extraction. Histone extraction and immunoblotting were done as previously described (15) with the some modification (see SI Text).

Map-Based Cloning of SOG.

Map-based cloning was carried out by using standard techniques (26). The xpf-2 sog1-1 (Ler/Col hybrid) line was crossed to an xpf-3 (SALK 096156, Col) line. F3 seeds harvested from individual F2 plants were screened for the sog (gamma-resistant leaf production) phenotype to determine which F2 individuals were homozygotes. The xpf sog1-1−/− and xpf SOG1+/+ families were then assayed for linkage to Col vs. Ler sequence polymorphisms. SOG1 was localized to a 45-kb region between nucleotides 8,976,528 and 9,021,427 of chromosome I containing 8 predicted genes. Sequence analysis of the coding regions of these genes revealed only one mutation: a G to A mutation in At1g25580. We then generated xpf-2 sog1-1 plants transgenic for the wild-type (Col) At1g25580 locus [a 4778 bp wild-type Col genomic fragment containing the complete At1g25580 transcribed region (3093 bp) with an additional 1579 bp upstream and 106 bp downstream]. We found that this fragment was sufficient to complement the radio-resistant leaf growth phenotype characteristic of the xpf-2 sog1-1 mutant. Details of the mapping and transgenic complementation experiments are provided in SI Text.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank undergraduate researchers Sarah Chin, Sigourney Woltjen, and Nargis Kohgadai for their assistance with genotyping and plant propagation; graduate students Ryan Kirkbride and Brad Townsley for their assistance with phylogenetic analysis; and both Dr. Kazunari Nozue and Dr. Jose M. Jimenez-Gomez for their assistance with data analysis. The xpf-3 line was a generous gift of the Hong Ma laboratory (Huck Institute of Life Science, Pennsylvania State University, State College, PA). We thank the 2 anonymous reviewers of this manuscript for their extensive and helpful comments. K.Y. was supported by a Postdoctoral Fellowship for Researcher Abroad from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS). This work was supported by Grant DE-FG02–05ER15668 (to A.B.B.) from the Chemical Sciences, Geosciences and Bioscience Division, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Office of Science, U.S. Department of Energy.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0810304106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Sancar A, Lindsey-Boltz LA, Unsal-Kaccmaz K, Linn S. Molecular mechanisms of mammalian DNA repair and the DNA damage checkpoints. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:39–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cimprich KA, Cortez D. ATR: An essential regulator of genome integrity. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:616–627. doi: 10.1038/nrm2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rozan LM, El-Deiry WS. p53 downstream target genes and tumor suppression: A classical view in evolution. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:3–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nedelcu AM, Tan C. Early diversification and complex evolutionary history of the p53 tumor suppressor gene family. Dev Genes Evol. 2007;217:801–806. doi: 10.1007/s00427-007-0185-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gasch A, et al. Genomic expression responses to DNA damaging agents and the regulatory role of the yeast ATR homolog Mec1p. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:2987–3003. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.10.2987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heitzeberg F, et al. The Rad17 homologue of Arabidopsis is involved in the regulation of DNA damage repair and homologous recombination. Plant J. 2004;38:954–968. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Culligan K, Robertson C, Foreman J, Doerner P, Britt A. ATR and ATM play both distinct and additive roles in response to ionizing radiation. Plant J. 2006;48:947–961. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ricaud L, et al. ATM-mediated transcriptional and developmental responses to gamma-rays in Arabidopsis. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e430. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia V, et al. AtATM is essential for meiosis and the somatic response to DNA damage in plants. Plant Cell. 2003;15:119–132. doi: 10.1105/tpc.006577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Culligan KM, Tissier A, Britt AB. ATR regulates a G2-phase cell-cycle checkpoint in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 2004;16:1091–1104. doi: 10.1105/tpc.018903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Preuss SB, Britt AB. A DNA damage induced cell cycle checkpoint in Arabidopsis. Genetics. 2003;164:323–334. doi: 10.1093/genetics/164.1.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niedernhofer LJ, et al. The structure-specific endonuclease Ercc1-Xpf is required to resolve DNA interstrand cross-link-induced double-strand breaks. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5776–5787. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.13.5776-5787.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dronkert MLG, Kanaar R. Repair of DNA interstrand cross-links. Mutat Res. 2001;486:217–247. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(01)00092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ooka H, et al. Comprehensive analysis of NAC family genes in Oryza sativa and Arabidopsis thaliana. DNA Res. 2003;10:239–247. doi: 10.1093/dnares/10.6.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friesner JD, Liu B, Culligan K, Britt AB. Ionizing radiation-dependent gamma-H2AX focus formation requires ataxia telangiectasia mutated and ataxia telangiectasia mutated and Rad3-related. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:2566–2576. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-10-0890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hefner E, Huefner N, Britt AB. Tissue-specific regulation of cell-cycle responses to DNA damage in Arabidopsis seedlings. DNA Repair. 2006;5:102–110. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hefner EA, Preuss SB, Britt AB. Arabidopsis mutants sensitive to gamma radiation include the homolog of the human repair gene ERCC1. J Exp Bot. 2003;54:669–680. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erg069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen I, Haehnel U, Altschmied L, Schubert I, Puchta H. The transcriptional response of Arabidopsis to genotoxic stress: A high density colony array study (HDCA) Plant J. 2003;35:771–786. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang M, Zhou Z, Elledge SJ. The DNA replication and damage checkpoint pathways induce transcription by inhibition of the Crt1 repressor. Cell. 1998;94:595–605. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81601-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brodsky MH, et al. Drosophila melanogaster MNK/Chk2 and p53 regulate multiple DNA repair and apoptotic pathways following DNA damage. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:1219–1231. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.3.1219-1231.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amundson SA, et al. Stress-specific signatures: Expression profiling of p53 wild-type and -null human cells. Oncogene. 2005;24:4572–4579. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kis E, et al. Microarray analysis of radiation response genes in primary human fibroblasts. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66:1506–1514. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stankovic T, et al. Microarray analysis reveals that TP53- and ATM-mutant B-CLLs share a defect in activating preapoptotic responses after DNA damage but are distinguished by major differences in activating prosurvival responses. Blood. 2004;103:291–300. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rashi-Elkeles S, et al. Parallel induction of ATM-dependent pro- and antiapoptotic signals in response to ionizing radiation in murine lymphoid tissue. Oncogene. 2006;25:1584–1592. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang CZ, Yen CN, Cronin K, Mitchell D, Britt AB. UV- and gamma-radiation sensitive mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics. 1997;147:1401–1409. doi: 10.1093/genetics/147.3.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lukowitz W, Gillmor C, Scheible W-R. Positional cloning in Arabidopsis. Why it feels good to have a genome initiative working for you. Plant Physiol. 2000;123:795–805. doi: 10.1104/pp.123.3.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.