Abstract

The tigrina (tig)-d.12 mutant of barley is impaired in the negative control limiting excess protochlorophyllide (Pchlide) accumulation in the dark. Upon illumination, Pchlide operates as photosensitizer and triggers singlet oxygen production and cell death. Here, we show that both Pchlide and singlet oxygen operate as signals that control gene expression and metabolite accumulation in tig-d.12 plants. In vivo labeling, Northern blotting, polysome profiling, and protein gel blot analyses revealed a selective suppression of synthesis of the small and large subunits of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RBCSs and RBCLs), the major light-harvesting chlorophyll a/b-binding protein of photosystem II (LHCB2), as well as other chlorophyll-binding proteins, in response to singlet oxygen. In part, these effects were caused by an arrest in translation initiation of photosynthetic transcripts at 80S cytoplasmic ribosomes. The observed changes in translation correlated with a decline in the phosphorylation level of ribosomal protein S6. At later stages, ribosome dissociation occurred. Together, our results identify translation as a major target of singlet oxygen-dependent growth control and cell death in higher plants.

Keywords: cell death, photooxidative stress, ribosome structure, S6 phosphorylation, ribosome dissociation

The biosynthesis of chlorophyll (Chl) is a light-dependent reaction in angiosperms (1). Several independent mechanisms regulate the activity of the C5 pathway leading to Chl. The first regulatory circuit operates at the level of 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) synthesis. Expression of key enzymes of 5-ALA synthesis is depressed in dark-grown plants (2, 3). Moreover, a negative feedback loop exerted by heme and protochlorophyllide (Pchlide) at the level of glutamyl-tRNA reductase (4, 5) reduces 5-ALA synthesis in the dark. Another factor was recently identified to be the FLUORESCENT (FLU) protein (6).

The tigrina (tig)-d.12 locus of barley is orthologous to the flu locus in Arabidopsis thaliana (7, 8). The tig-d.12 is a conditional cell death mutant. When tig-d.12 plants are grown in continuous white light, they are fully viable and do not show any signs of damage. However, tig-d.12 seedlings develop transverse-striped leaves with green and white sectors under alternate light/dark cycles. Free Pchlide synthesized in the dark operates as photosensitizer and, by triplet–triplet interchange, provokes singlet oxygen production and photooxidative damages during subsequent light periods, whereas the pigment is continuously converted to chlorophyllide by virtue of the NADPH:protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase in leaf sectors emerging during the light period (7). Similarly, etiolated tig-d.12 seedlings accumulate excessive amounts of Pchlide and die rapidly when illuminated (7). Cell death triggered in flu and, presumably, also in tig-d.12 plants is a combined effect of the cytotoxic properties of singlet oxygen and the operation of a genetic pathway involving the EXECUTER 1 and EXECUTER 2 genes (9, 10). Transcription of singlet oxygen-responsive genes has been reported previously (11). Whether translation also may contribute to singlet oxygen-triggered growth control and cell death was thus far undetermined, and this motivated us to perform the current study. In animals and humans, translation is a major target for cell size and growth control as well as programmed cell death and apoptosis (12–14). In the present work, we report on changes in transcript accumulation, translation, and metabolite profiles in tig-d.12 plants in response to singlet oxygen.

Results

Pchlide-Dependent and Singlet Oxygen-Dependent Changes in Protein Synthesis in tig-d.12 and Wild-Type Plants.

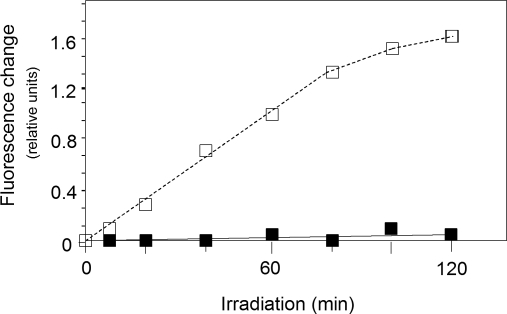

Seedlings of tig-d.12 and wild-type were grown in the dark for 5 days and exposed to white light of approximately 125 micro-Einsteins (≈125 μE) m−2 sec−1 for variable periods. To see whether or not tig-d.12 plants would respond to illumination with the generation of singlet oxygen, DanePy measurements were carried out (15–17). The DanePy reagent is a dansyl-based singlet oxygen sensor whose green fluorescence is quenched upon reacting with singlet oxygen. Fig. 1 shows that irradiation of etiolated tig-d.12 plants gave rise to generation of singlet oxygen. Singlet oxygen production was linear for at least 1 h in tig-d.12 plants, and then it reached a plateau. The linear relationship between singlet oxygen generation and time in the early period of irradiation excluded the possibility that the nitroxide radicals formed from DanePy were partly reduced and transformed into inactive states in the samples (17). At later stages, DanePy may be converted into an inactive state or disintegrate spontaneously. On the other hand, singlet oxygen production may cease because of the destruction of Pchlide operating as a photosensitizer. It has been reported that photooxidative stress easily leads to a rapid pigment bleaching (18). In wild-type seedlings, no singlet oxygen production was measurable over the time course of the experiment (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Singlet oxygen production in dark-grown tig-d.12 and wild-type seedlings after irradiation. The tig-d.12 and wild-type seedlings were grown in the dark for 5 days. Then, DanePy was applied to the leaf tissues by infiltration. For estimation of singlet oxygen levels on an equal leaf surface area, singlet oxygen trapping was measured as relative fluorescence quenching at the 532-nm emission maximum of DanePy. The curves show fluorescence quenching in leaf tissues of irradiated tig-d.12 (□) and wild-type (■) seedlings.

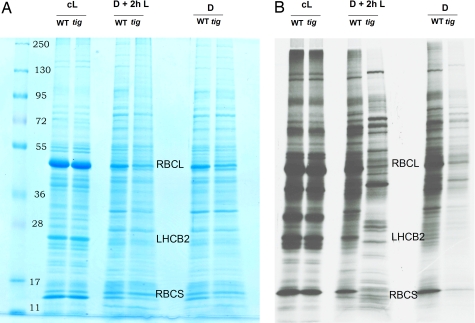

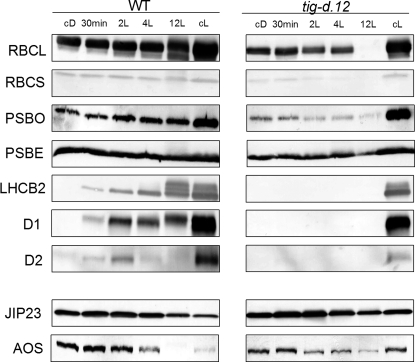

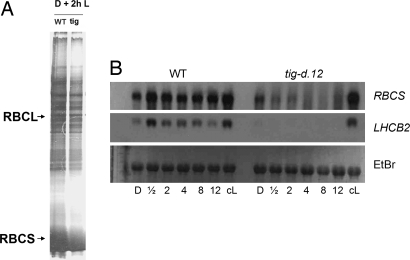

Next, pulse labeling of protein with [35S]methionine was carried out for 2 h before seedling harvest. Fig. 2 shows that already in the dark, differences occurred in the polypeptide patterns of wild-type and tig-d.12 plants. Reductions in the synthesis and accumulation were observed for the large and small subunits of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RBCL and RBCS gene products). These differences were further enhanced upon illumination. After 2 h of irradiation, a number of proteins were synthesized in tig-d.12 plants that were weakly labeled in wild-type plants (Fig. 2). Protein gel blot analyses revealed that Chl-binding proteins, such as LHCB2, D1, and D2, which encode major components of photosystem II, did not accumulate in irradiated tig-d.12 seedlings (Fig. 3). By contrast, stress-induced proteins, such as allene oxide synthase (AOS), a key enzyme of jasmonic acid (JA) biosynthesis, and other, major jasmonate-induced proteins, such as JIP5 (thionin) and JIP23, were present both in tig-d.12 and wild-type plants, although their amounts were different after 12 h of greening (Fig. 3). When etiolated tig-d.12 seedlings were exposed to white light for periods longer than 24 h, total protein synthesis dropped to undetectable levels (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Pchlide- and singlet oxygen-dependent changes in the protein patterns of etiolated and irradiated tig-d.12 and wild-type plants. (A) Pattern of Coomassie-stained proteins in dark-grown tig-d.12 and wild-type seedlings (D) and in etiolated tig-d.12 and wild-type seedlings that had been exposed to white light of 125 μE m−2 sec−1 for 2 h before harvest (D + 2h L). For comparison, the pattern of proteins is shown for tig-d.12 and wild-type seedlings that had been cultivated in continuous white light for 5 days (cL). (B) As in A, but depicting the patterns of [35S]methionine-labeled proteins. Positions of molecular mass markers are highlighted. RBCL and RBCS designate the large and small subunits of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase; LHCB2 designates the light-harvesting chlorophyll a/b-binding protein 2 of photosystem II.

Fig. 3.

Western blot analysis of abundant photosynthetic proteins in etiolated tig-d.12 and wild-type plants after different lengths of irradiation with white light of 125 μE m−2 sec−1. RBCL and RBCS, large and small subunits of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase, respectively; PSBO and PSBE, O and E subunits of photosystem II, respectively; LHCB2, light-harvesting chlorophyll a/b-binding protein 2 of photosystem II; D1 and D2, reaction center polypeptides of photosystem II; JIP23, jasmonate-induced 23-kDa protein; AOS, allene oxide synthase.

Metabolite Profiles of tig-d.12 and Wild-Type Plants.

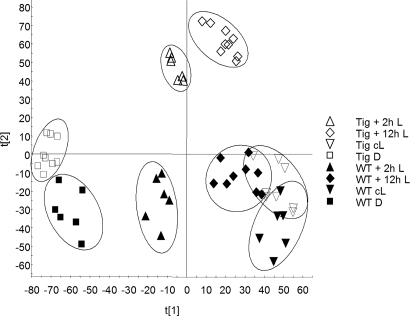

In order to gain insight into singlet oxygen-dependent changes in gene expression, a metabolite-profiling approach was taken. Methanol extracts were prepared from tig-d.12 and wild-type plants and subjected to ultraperformance liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization/quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS) analyses. This profiling approach is capable of resolving several hundred to a few thousand features (mass–retention time pairs)—i.e., metabolites or their mass fragments—in one run (19–21). Studies carried out for A. thaliana have shown that this method can resolve known classes of Arabidopsis secondary metabolites, such as indole-derived compounds (e.g., indole acetic acid derivatives), degradation products of glucosinolates (sulfinyl nitriles and isothiocyanates), phenylpropanoids (sinapoylmalate), and flavonoids, as well as their glycosides (e.g., kaempferol-3-O-α-l-rhamnopyranosid-7-O-α-l-rhamnopyranosid) (19). The individual metabolite profiles obtained for barley wild-type and tig-d.12 plants were compared by principal component analysis (PCA), a data reduction and visualization technique (22). Fig. 4 and Fig. S1 depict the overall similarity/dissimilarity of the respective entities for etiolated, irradiated, and light-grown tig-d.12 and wild-type seedlings. A pairwise orthogonal partial least-squares to latent structures analysis of tig-d.12 and wild-type samples allowed the identification of markers that significantly contribute to the separation of the groups (cL, D, and 2-h L). The entries were sorted according to their covariance (magnitude) and correlation (reliability) (23). In summary, the metabolite profiles of tig-d.12 plants grown under continuous light closely resembled those of the corresponding wild-type plants. However, marked differences occurred between dark-grown tig-d.12 and wild-type plants. These differences were further pronounced when etiolated tig-d.12 and wild-type seedlings were irradiated.

Fig. 4.

Compilation of changes in the metabolite levels of etiolated tig-d.12 and wild-type seedlings after irradiation. PCA (scores plot) of the metabolite profiles obtained in the positive ionization mode, illustrating the overall metabolic differences between tig-d12 and wild-type plants, depending on the light conditions.

Depression of Nucleus-Encoded Photosynthetic Transcripts in tig-d.12 Versus Wild-Type Plants.

To assess whether the observed large differences in the in vivo-labeling pattern of proteins in tig-d.12 versus wild-type plants were caused by corresponding changes of their respective mRNAs, in vitro translation experiments were carried out. A rabbit reticulocyte lysate was programmed with mRNA prepared from etiolated tig-d.12 and wild-type plants that had been exposed to white light for 2 h. Fig. 5A shows that this approach did not reveal gross differences in the patterns of translatable mRNAs for irradiated tig-d.12 and wild-type plants. Northern blot analyses showed that RBCS mRNA was reduced in amount in mutant compared with wild-type plants both in the dark and after illumination (Fig. 5B). In either case, this reduction in RBCS synthesis was much lower than that measured in vivo (compare with Fig. 2). LHCB2 transcript levels were drastically reduced and were in most experiments below the limit of detection, and no LHCB2 protein accumulated in irradiated tig-d.12 seedlings (Figs. 3 and 5). When light-grown tig-d.12 plants were subjected to a nonpermissive 12-h dark to 12-h light shift, reductions in the synthesis of RBCS and LHCB2 similar to those reported for etiolated plants were observed, whereas only little changes were detectable in the pattern of in vitro-translatable mRNAs (Fig. S2). DanePy measurements confirmed singlet oxygen production in response to the 12-h dark to 12-h light shift (Fig. S3).

Fig. 5.

mRNA levels in etiolated tig-d.12 and wild-type plants after a 2-h light shift. (A) Patterns of polypeptides translated in a rabbit reticulocyte lysate from RNA of 2-h irradiated tig-d.12 and wild-type plants. RBCL and RBCS mark the large and small subunits of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase, respectively. (B) Northern blot analysis of RBCS and LHCB2 transcript levels in dark-grown and irradiated tig-d.12 and wild-type plants after different periods of illumination. The lower part shows the ethidium bromide (EtBr)-stained 28S rRNA used as loading control.

Polysome Binding of Stress and Defense Versus Photosynthetic Messengers in tig-d.12 and Wild-Type Plants.

The drastic reduction in RBCS synthesis in vivo and only moderate reduction in the level of its respective messenger in vitro in tig-d.12 seedlings subjected to nonpermissive dark-to-light shifts suggested a posttranscriptional mode of control. To explore this possibility, polysomes were isolated from etiolated and illuminated tig-d.12 and wild-type plants and were subjected to sucrose density gradient centrifugation. Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) material contained in the different fractions was recovered by ethanol precipitation and used for Northern blot hybridization and in vitro translation. In parallel, RBCS, AOS, thionin, and actin protein levels present in the different polysomal fractions were quantified by Western blotting using large-scale polysome preparations. Thionins are small fungitoxic proteins localized in the plant cell wall that accumulate in etiolated plants and reappear in illuminated plants in response to pathogens and adverse conditions (24). AOS encodes a key enzyme of JA biosynthesis; its expression is induced after abiotic and biotic stress (summarized in ref. 25).

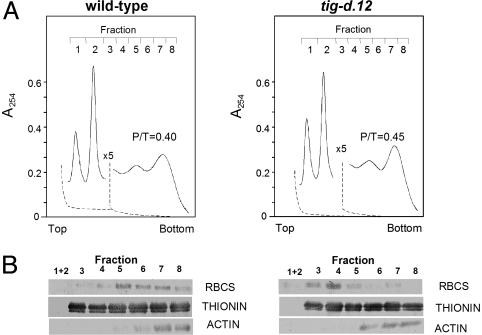

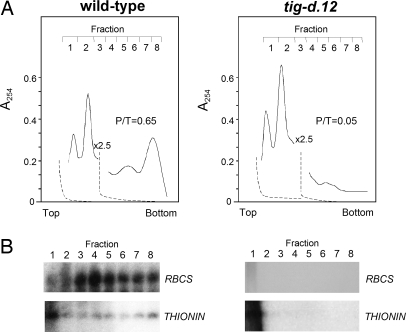

Fig. 6A shows absorbance profiles of RNP material that had been extracted from etiolated tig-d.12 and wild-type plants after 2 h of irradiation. Based on the absorbance readings, no major difference was apparent in the polysome profiles. However, upon analyzing individual polysomal fractions by Western blotting, a massive reduction in polysome binding of RBCS transcripts was found for tig-d.12 seedlings. RBCS transcripts, in fact, were confined to smaller polysomes in irradiated tig-d.12 plants compared with wild-type seedlings (Fig. 6B). This result suggested a depression in translation initiation to occur in tig-d.12 plants in response to singlet oxygen. Similarly, RBCS transcript binding to polysomes was reduced in 4.5-day-old, light-grown tig-d.12 plants that had been subjected to a 12-h dark to 12-h light shift (Fig. S4). This effect correlated with the observed drop in RBCS synthesis but was at variance with the unchanged level of translatable RBCS mRNA in vitro (Fig. S2). Both etiolated and light-adapted tig-d.12 seedlings reacted to nonpermissive conditions causing singlet oxygen production with similar dissociations of their 80S cytoplasmic polysomes into the respective ribosomal subunits when the illumination period was extended to 24 h (Fig. 7 and Fig. S5).

Fig. 6.

Polysome profiles of dark-grown tig-d.12 and wild-type plants after a 2-h white light exposure. RNP material was extracted from irradiated tig-d.12 and wild-type seedlings and resolved on sucrose gradients. (A) Absorbance readings at 254 nm of polysomes (fractions 3–8) and the 40S and 60S ribosomal subunits (fractions 1 and 2). A 5-fold decrease in full-scale absorbance is indicated by a break in the absorbance tracing of each profile. Dashed lines represent baselines. The top of the gradients is to the left. Note that absorbance at the top of the gradient is not included because of the high absorbance of Triton X-100. (B) Western blot used to determine RBCS, THIONIN, and ACTIN protein levels in the different polysomal fractions. The P/T ratios are given.

Fig. 7.

Polysome profiles of dark-grown tig-d.12 and wild-type plants after a 24-h white light shift. RNP material was extracted from irradiated tig-d.12 and wild-type seedlings and resolved in sucrose gradients. (A) Absorbance tracings at 254 nm of polysomes (fractions 3–8) and the 40S and 60S ribosomal subunits (fractions 1 and 2). A 2.5-fold decrease in full-scale absorbance is indicated by a break in the absorbance tracing of each profile. Dashed lines represent baselines. The top of the gradients is to the left. Note that absorbance at the top of the gradient is not included because of the high absorbance of Triton X-100. (B) Northern blot analysis used to determine RBCS and THIONIN transcript levels in the different polysomal fractions. P/T ratios are indicated.

S6 Dephosphorylation in tig-d.12 and Wild-Type Plants.

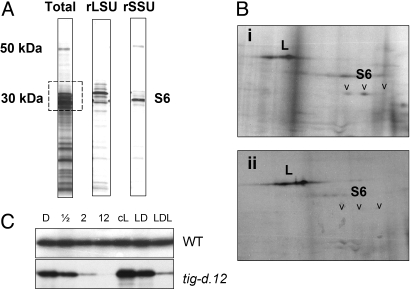

Ribosomal protein S6 is a major mediator of translational control and changes its phosphorylation state under a variety of adverse conditions in animals and plants (26–28). To determine whether singlet oxygen may trigger changes in S6 phosphorylation, pulse-labeling studies were carried out with [32P]phosphate. Leaf tissues were incubated with [32P]phosphate; then, ribosomes were isolated, and their phosphoprotein pattern was analyzed by 1D and 2D SDS/PAGE. Fig. 8 shows the phosphorylation status of ribosomal protein S6 for etiolated wild-type and tig-d.12 plants after different periods of irradiation. The results revealed a decline in the phosphorylation of S6 in tig-d.12 but not wild-type plants (Fig. 8 B and C). When light-grown tig-d.12 seedlings were exposed to a 12-h dark to 12-h light shift, a similar decline in the phosphorylation level of S6 became apparent (Fig. 8C, LDL).

Fig. 8.

Ribosomal protein S6 dephosphorylation in irradiated tig-d12 plants. (A) 1D pattern of 32P-labeled proteins present in total ribosomes (Total) and in large (rLSU) and small (rSSU) ribosomal subunits isolated from 5-day-old, dark-grown wild-type plants. (B) 2D pattern of ribosomal 32P-labeled proteins in dark-grown wild-type seedlings (Bi) and tig-d.12 seedlings (Bii) after a 4-h period of irradiation. The autoradiogram shows 32P-labeled proteins of the molecular mass range boxed in A. Arrowheads mark ribosomal protein S6 isoforms. (C) S6 dephosphorylation in dark-grown tig-d.12 and wild-type (WT) plants after various periods of irradiation (in hours) and in light-adapted plants before (cL) and after a 12-h dark (LD) and subsequent 12-h light (LDL) shift.

Discussion

In the present work, changes occurring at the transcript, translational, and metabolite levels in response to Pchlide and singlet oxygen were analyzed for the tig-d.12 mutant of barley. We show that dark-grown tig-d.12 seedlings synthesize a pattern of polypeptides and metabolites that is distinct from that of wild-type plants. Lower levels of RBCS and LHCB2 transcripts were found on Northern blots. It is likely that Pchlide operated as a signal that affected the expression of nuclear genes. Also, other tetrapyrroles have documented effects on transcription of nucleus-encoded genes for plastid proteins (29–34).

Once illuminated, Pchlide accumulating in dark-grown tig-d.12 seedlings operated as a photosensitizer and provoked generation of singlet oxygen. Both Pchlide synthesis and singlet oxygen production appear to be confined to the plastid compartment in irradiated tig-d.12 plants and flu (11) plants, suggesting the presence of intermediates that leave the plastid to control gene expression in the nucleocytoplasmic space. Given that the plastid envelope is a site of Pchlide synthesis (35, 36), it seems likely that membrane-derived signals, such as oxygenated fatty acid derivatives, including JA (see below), function in the complex signaling network controlling protein synthesis at 80S ribosomes. As shown here, polysomes isolated from etiolated tig-d.12 plants that had been irradiated for 2 h contained fewer RBCS transcripts than polysomes from wild-type plants. These RBCS transcripts were confined to smaller polysomes, suggesting a depression of translation initiation occurs in response to singlet oxygen. Because translation initiation is rate-limiting for protein synthesis under most physiological conditions (37, 38), we exclude an effect of singlet oxygen on translation elongation of RBCS transcripts in irradiated tig-d.12 plants. In line with this view, THIONIN and AOS transcripts were equally distributed to small and large polysomes and gave rise to protein.

Singlet oxygen is both a powerful cytotoxin and a potent signaling compound (6, 9–11, 39, 40). Pioneering work performed by Apel and coworkers (see ref. 41 for review) for the flu mutant has provided valuable insights into the complexity of cell death regulation by singlet oxygen and other reactive oxygen species. Transcriptome analyses identified genes that differentially responded to singlet oxygen and hydrogen peroxide (11, 42). Among the genes specifically induced by singlet oxygen were those for ERF/AP2, MYB, WRKY and other transcription factors, calmodulin-like proteins, and the ENHANCED DISEASE SUSCEPTIBILITY 1 and BONZAI 1 proteins, 2 key components operating in defense signaling and growth control (11, 43). Genes that were down-regulated by singlet oxygen included those for components operating in auxin synthesis and transport, as well as constituents of the photosynthetic apparatus (11).

The results presented in this work add to the understanding of singlet oxygen action in higher plants and reveal its role in the regulation of translation. We show that singlet oxygen can provoke a rapid dephosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6. Whether this is a direct effect caused by the cytotoxicity of singlet oxygen or an indirect effect caused by the operation of specific signaling pathways is unknown. Precedents for photodynamic regulation of protein synthesis exist in the literature. For example, Yang and Hoober (44) reported on a Ca2+-dependent, 14-kDa surface protein in the bacterium Arthrobacter photogonimos that was inactivated under photodynamic conditions provoking the generation of singlet oxygen. The 14-kDa protein operates as repressor of the light-inducible lipA gene (45). Removal of the 14-kDa protein constitutively activated lipA expression in the dark (44). For irradiated tig-d.12 plants, two possible explanations of how singlet oxygen may act on translation are (i) inhibition of S6 and upstream TOR or NPDK1 kinases, or (ii) activation of protein phosphatases dephosphorylating S6. Both reactions are prone to adverse conditions (46–48) and may involve Ca2+ and calmodulin-like proteins to be explored in future work.

A third, remarkable result of this study is the demonstration of ribosome dissociation occurring in tig-d.12 plants in response to singlet oxygen. This result is reminiscent of our previous findings for leaf tissues of barley treated with the methyl ester of JA, methyl jasmonate (49–51). Endogenous JA accumulates under various stress conditions, such as heat shock, UV light exposure, and desiccation, as well as in response to wounding and bacterial and fungal pathogens (see ref. 25 for review). Singlet oxygen rapidly activates the expression of JA biosynthetic genes, such as those for lipoxygenase, AOS, and allene oxide cyclase, and thereby boosts JA generation in flu plants (52, 53). It is therefore attractive to suppose a role of JA in reprogramming translation in response to singlet oxygen. Work is underway to dissect the mechanism of singlet oxygen-dependent translational control in higher plants.

Materials and Methods

Plant Growth.

The tig-d.12 mutant has been described previously (7). Tig-d.12 and wild-type seeds were germinated on moist vermiculite under the following conditions. In a first set of experiments, seedlings were grown in the dark for 5 days and exposed to white light (125 μE m−2 sec−1), provoking singlet oxygen production. In a second set of experiments, seedlings were germinated for 4.5 days in continuous white light and subsequently subjected to a 12-h dark shift before being reilluminated. As controls, wild-type seedlings were treated identically.

Singlet Oxygen Measurements.

Singlet oxygen generation was measured with the DanePy method developed by Hideg et al. (15) and Kálai et al. (16, 17). Fluorescence emission spectroscopy was performed at an excitation wavelength of 330 nm and collecting fluorescence emission between 515–550 nm using a spectrometer (model LS50; Perkin–Elmer).

Protein Analyses.

Pulse labeling of protein was carried out with [35S]methionine (37 TBq/mmol; Amersham-Pharmacia) for 2 h before seedling harvest. After extraction, leaf protein was precipitated with trichloroacetic acid and subjected to SDS/PAGE on 10–20% polyacrylamide gradients (46, 47). Immunodetection of electrophoretically resolved proteins (54) was carried out by using an enhanced chemiluminescene system (Amersham-Pharmacia) and the indicated antisera that were obtained from Agrisera.

RNA Analyses.

Total RNA was prepared from leaf segments by phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol extraction (49). After precipitation with lithium chloride, high-molecular mass RNAs were translated into polypeptides in a rabbit reticulocyte system or wheat germ system. Assays for 1D and 2D polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis contained 11.2 MBq l-[35S]methionine (37 TBq mmol−1; Amersham-Pharmacia). For Northern blotting, RNA was separated on agarose gels and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (BA-45; Schleicher and Schuell) before being hybridized with [32P]dATP-labeled and [32P]dCTP-labeled cDNA probes under high-stringency conditions (49).

Polysome Isolation and Analysis.

Polysomes were isolated by Mg2+ precipitation and sucrose density gradient centrifugation as described previously (49). Details on the buffers and conditions used can be found in the SI Methods. After centrifugation at 60,000 rpm in a Beckman Spinco L75 centrifuge, rotor Ti 60, for 1 h at 4 °C, the gradient was harvested from bottom to top in a modified Beckman harvesting device, with continuous monitoring of the absorbance at 254 nm (2138 Uvicord S; LKB). After integration of the areas below the curves, the ratio of polysomes to total ribosome (P/T) was calculated as follows: (area of polysomes)/(area of polysomes + ribosomal subunits + monosomes). From the arbitrarily defined gradient fractions, each corresponding to 10 drops (≈0.35 mL), the RNAs were recovered by ethanol precipitation and subsequently used for Northern blot hybridization or in vitro translation (see above). In parallel assays, protein was extracted from the polysomal fractions with trichloroacetic acid and washed extensively with ethanol and diethyl ether. All of these operations were performed at 4 °C. Ribosomal protein phosphorylation was studied as described by Scharf and Nover (46) and Nover and Scharf (47) by using [32P]phosphate as tracer. The 2D electrophoresis of 32P-labeled ribosomal proteins included isoelectric focusing in the first dimension and SDS/PAGE on 10–20% polyacrylamide gradients in the second dimension. Basic ribosomal proteins were separated by the Kaltschmidt–Wittmann technique that is described in ref. 46.

Metabolite Profiling.

Plant material was essentially extracted as described previously and subjected to UPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS analyses (19–21). Signals from 0.5 to 16 min within 80 to 1,000 Da were taken into account. Based on these discriminatory markers (i.e., mass–retention time pairs), PCA and partial least-squares to latent structures were performed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We are grateful to K. Kálai and E. Hideg (Institute for Plant Biology, Biological Research Centre, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Szeged, Hungary) for a gift of the DanePy reagent. This study was supported by the Chaire d'Excellence program of the French Ministry of Research (C.R.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0903522106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.von Wettstein D, Gough S, Kannangara CG. Chlorophyll biosynthesis. Plant Cell. 1995;7:1039–1057. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.7.1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Batschauer A, Apel K. An inverse control by phytochrome of the expression of two nuclear genes in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) Eur J Biochem. 1984;143:593–597. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1984.tb08411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huq E, et al. Phytochrome-interacting factor 1 is a critical bHLH regulator of chlorophyll biosynthesis. Science. 2004;305:1937–1941. doi: 10.1126/science.1099728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pontoppidan B, Kannangara CG. Purification and partial characterisation of barley glutamyl-tRNA(Glu) reductase, the enzyme that directs glutamate to chlorophyll biosynthesis. Eur J Biochem. 1994;225:529–537. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.00529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vothknecht U, Kannangara CG, von Wettstein D. Barley glutamyl tRNAGlu reductase: Mutations affecting haem inhibition and enzyme activity. Phytochemistry. 1998;47:513–519. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(97)00538-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meskauskiene R, et al. FLU: A negative regulator of chlorophyll biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:12826–12831. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221252798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.von Wettstein D, Kahn A, Nielsen OF, Gough S. Genetic regulation of chlorophyll synthesis analyzed with mutants in barley. Science. 1974;184:800–802. doi: 10.1126/science.184.4138.800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee KP, Kim C, Lee DW, Apel K. TIGRINA d, required for regulating the biosynthesis of tetrapyrroles in barley, is an ortholog of the FLU gene of Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett. 2002;553:119–124. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00983-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wagner D, et al. The genetic basis of singlet oxygen-induced stress responses of Arabidopsis thaliana. Science. 2004;306:1183–1185. doi: 10.1126/science.1103178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee KP, Kim C, Landgraf F, Apel K. EXECUTER1- and EXECUTER2-dependent transfer of stress-related signals from the plastid to the nucleus of Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:10270–10275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702061104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.op den Camp RG, et al. Rapid induction of distinct stress responses after the release of singlet oxygen in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2004;15:2320–2332. doi: 10.1105/tpc.014662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bommer UA, Thiele BJ. The translationally controlled tumour protein (TCTP) Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:379–385. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(03)00213-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kozma SC, Thomas G. Regulation of cell size in growth, development and human disease: PI3K, PKB and S6K. BioEssays. 2002;24:65–71. doi: 10.1002/bies.10031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dufner A, Thomas G. Ribosomal S6 kinase signalling and the control of translation. Exp Cell Res. 1999;253:100–109. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hideg E, Kálai T, Hideg K, Vass I. Photoinhibition of photosynthesis in vivo results in singlet oxygen production: Detection via nitroxide-induced fluorescence quenching in broad bean leaves. Biochemistry. 1998;37:11405–11411. doi: 10.1021/bi972890+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kálai T, Hankovszky O, Hideg E, Jeko J, Hideg K. Synthesis and structure optimization of double (fluorescent and spin) sensor molecules. ARKIVOC. 2002;iii:112–120. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kálai T, Hideg E, Vass I, Hideg K. Double (fluorescent and spin) sensor for detection of reactive oxygen species in the thylakoid membranes. Free Radical Biol Med. 1998;24:649–652. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(97)00339-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reinbothe S, Reinbothe C, Apel K, Lebedev N. Evolution of chlorophyll biosynthesis: The challenge to survive photooxidation. Cell. 1996;86:703–705. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80144-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.von Roepenack-Lahaye E, et al. Profiling of Arabidopsis secondary metabolites by capillary liquid chromatography coupled to electrospray ionization quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Plant Physiol. 2004;134:548–559. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.032714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Böttcher C, von Roepenack-Lahaye EV, Willscher E, Scheel D, Clemens S. Evaluation of matrix effects in metabolite profiling based on capillary liquid chromatography electrospray ionization quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2007;79:1507–1513. doi: 10.1021/ac061037q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Böttcher C, et al. Metabolome analysis of biosynthetic mutants reveals a diversity of metabolic changes and allows identification of a large number of new compounds in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2008;147:2107–2120. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.117754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wiklund S, et al. Visualization of GC/TOF-MS-based metabolomics data for identification of biochemically interesting compounds using OPLS class models. Anal Chem. 2007;80:115–122. doi: 10.1021/ac0713510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fiehn O, et al. Metabolite profiling for plant functional genomics. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:1157–1161. doi: 10.1038/81137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bohlmann H, et al. Leaf-specific thionins of barley - a novel class of cell wall proteins toxic to plant-pathogenic fungi and possible involvement in the defence mechanism of plants. EMBO J. 1988;7:1559–1565. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02980.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wasternack C. Jasmonates: An update on biosynthesis, signal transduction and action in plant stress response, growth and development. Ann Bot (London) 2007;100:681–697. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcm079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas G. The S6 kinase signalling pathway in the control of development and growth. Biol Res. 2002;35:305–313. doi: 10.4067/s0716-97602002000200022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dennis PB, Fumagalli S, Thomas G. Target of rapamycin (TOR): Balancing the opposing forces of protein synthesis and degradation. Curr Opin Genet. 1999;9:49–54. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(99)80007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Menand B, Meyer C, Robaglia C. Plant growth and the TOR pathway. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2004;279:97–113. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-18930-2_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strand A, Asami T, Alonso A, Ecker JR, Chory J. Chloroplast to nucleus communication triggered by accumulation of Mg-protoporphyrin IX. Nature. 2003;423:79–83. doi: 10.1038/nature01204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mochizuki N, Brusslan JA, Larkin R, Nagatani A, Chory J. Arabidopsis genomes uncoupled 5 (GUN5) mutant reveals the involvement of Mg-chelatase H subunit in plastid-to-nucleus signal transduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:2053–2058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.4.2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Larkin RM, Alonso JM, Ecker JR, Chory J. GUN4, a regulator of chlorophyll synthesis and intracellular signaling. Science. 2003;299:902–906. doi: 10.1126/science.1079978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koussevitzky S, et al. Signals from chloroplasts converge to regulate nuclear gene expression. Science. 2007;316:715–719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moulin M, McCormac AC, Terry MJ, Smith AG. Tetrapyrrole profiling in Arabidopsis seedlings reveals that retrograde plastid nuclear signaling is not due to Mg-protoporphyrin IX accumulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:15178–15183. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803054105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mochizuki N, Tanaka R, Tanaka A, Masuda T, Nagatani A. The steady-state level of Mg-protoporphyrin IX is not a determinant of plastid-to-nucleus signaling in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:15184–15189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803245105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joyard J, Block M, Pineau B, Albrieux C, Douce R. Envelope membranes from mature spinach chloroplasts contain a NADPH:protochlorophyllide reductase on the cytosolic side of the outer membrane. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:21820–21827. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pineau B, Gerard-Hirne C, Douce R, Joyard J. Identification of the main species of tetrapyrrolic pigments in envelope membranes from spinach chloroplasts. Plant Physiol. 1993;102:821–828. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.3.821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vassart G, Dumont JE, Cantraine FRL. Translational control of protein synthesis: a simulation study. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1971;247:471–485. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(71)90034-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lodish HF. Translational control of protein synthesis. Annu Rev Biochem. 1976;45:39–73. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.45.070176.000351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kochevar I. Singlet oxygen signalling: From intimate to global. Sci STKE. 2004;221:pe7. doi: 10.1126/stke.2212004pe7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maugh TH. Singlet oxygen: A unique microbicidal agent in cells. Science. 1973;182:44–45. doi: 10.1126/science.182.4107.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim C, Meskauskiene R, Apel K, Laloi C. No single way to understand singlet oxygen signalling in plants. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:435–439. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Laloi C, et al. Cross-talk between singlet oxygen- and hydrogen peroxide-dependent signaling of stress responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:672–677. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609063103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gadjev I, et al. Transcriptomic footprints disclose specificity of reactive oxygen species signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2006;141:436–445. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.078717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang H, Hoober JK. Regulation of lipA gene expression by cell surface proteins in Arthrobacter photogonimos. Curr Microbiol. 1999;38:92–95. doi: 10.1007/s002849900409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoober JK, Phinney DG. Induction of a light-inducible gene in Arthrobacter photogonimos sp. by exposure of cells to chelating agents and pH5. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;950:234–237. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(88)90016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scharf KD, Nover L. Heat-shock-induced alterations of ribosomal protein phosphorylation in plant cell cultures. Cell. 1982;30:427–437. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90240-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nover L, Scharf KD. Synthesis, modification and structural binding of heat-shock proteins in tomato cell cultures. Eur J Biochem. 1984;139:303–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1984.tb08008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bailey-Serres J, Freeling M. Hypoxic stress-induced changes in ribosomes of maize seedling roots. Plant Physiol. 1990;94:1237–1243. doi: 10.1104/pp.94.3.1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reinbothe S, Reinbothe C, Parthier B. Methyl jasmonate-regulated translation of nuclear-encoded chloroplast proteins in barley (Hordeum vulgare L. cv. Salome) J Biol Chem. 1993;268:10606–10611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reinbothe S, Reinbothe C, Parthier B. Methyl jasmonate represses translation initiation of a specific set of mRNAs in barley. Plant J. 1993;4:459–467. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reinbothe S, et al. JIP60, a methyl jasmonate-induced ribosome-inactivating protein involved in plant stress reactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7012–7016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Danon A, Miersch O, Felix G, op den Camp RG, Apel K. Concurrent activation of cell death-regulating signalling pathways by singlet oxygen in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2005;41:68–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Przybyla D, et al. Enzymatic, but not non-enzymatic 1O2-mediated peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids forms part of the EXECUTER1-dependent stress response program in the flu mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2008;54:236–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Towbin M, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: Procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.