Abstract

Introduction

Medicaid recipients are disproportionately affected by tobacco-related disease because their smoking prevalence is approximately 53% greater than that of the overall US adult population. This study estimates state-level smoking-attributable Medicaid expenditures.

Methods

We used state-level and national data and a 4-part econometric model to estimate the fraction of each state's Medicaid expenditures attributable to smoking. These fractions were multiplied by state-level Medicaid expenditure estimates obtained from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to estimate smoking-attributable expenditures.

Results

The smoking-attributable fraction for all states was 11.0% (95% confidence interval, 0.4%-17.0%). Medicaid smoking-attributable expenditures ranged from $40 million (Wyoming) to $3.3 billion (New York) in 2004 and totaled $22 billion nationwide.

Conclusion

Cigarette smoking accounts for a sizeable share of annual state Medicaid expenditures. To reduce smoking prevalence among recipients and the growth rate in smoking-attributable Medicaid expenditures, state health departments and state health plans such as Medicaid are encouraged to provide free or low-cost access to smoking cessation counseling and medication.

Introduction

Medicaid is a means-tested entitlement program that provides health care coverage to approximately 58 million low-income Americans, many of whom would otherwise be uninsured (1,2). The Medicaid program is jointly financed by the federal and state governments. In 2005, depending on a state's average personal income level, the federal Medicaid matching rate ranged from 50% to 83% (1). The Congressional Budget Office estimates that federal Medicaid expenditures were $191 billion in 2007 (3). Assuming an average Medicaid matching rate of 57%, program expenditures for all 50 states and the District of Columbia are projected to have exceeded $144 billion in 2007 (4,5). By 2018, total federal Medicaid spending is projected to be $445 billion, and assuming a 57% matching rate, total state Medicaid spending is projected to exceed $335 billion (3).

As a percentage of state budgets, Medicaid expenditures increased from 8% in 1985 to 21.5% in 2006, surpassing elementary and secondary education as the largest single budget item (2,5). Medicaid expenditures are expected to consume an ever-increasing share of state budgets, and many states will have difficulty meeting their Medicaid commitments without cutting other state-funded programs (1,5,6). In response to growing concern among state governments, the chairman and vice-chairman of the National Governors Association, in testimony before the US Senate Finance Committee, recommended placing a greater emphasis on disease prevention as a means to contain rising Medicaid costs (6).

Tobacco-cessation programs are effective in lowering the prevalence of cigarette smoking and its consequent serious and costly medical conditions, including pregnancy-related complications, heart disease, respiratory illness, and several types of cancer (7-9). Tobacco-cessation programs should target Medicaid recipients because smoking prevalence in the adult Medicaid population is approximately 53% greater than that of the overall US adult population (34.5% vs 22.6% in 2006) (10).

We used data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) and the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) to update previous estimates of Medicaid smoking-attributable medical expenditures at the state level (11). These estimates might assist state health departments and Medicaid in formulating effective smoking-cessation polices to help reduce the high prevalence of cigarette use among their recipients.

Methods

Data

We used the 2001 and 2002 MEPS to develop a model that predicts smoking-attributable medical expenditures for the Medicaid population. MEPS is a nationally representative survey of the civilian, noninstitutionalized population that quantifies each participant's total annual medical spending, including expenditures from public- and private-sector health insurers and out-of-pocket payments. The data also include information about each participant's source of health insurance (eg, any evidence of Medicaid coverage during the year) and sociodemographic characteristics (such as race/ethnicity, sex, and education). Information about MEPS is available at www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/.

The MEPS sampling frame is drawn from participants in the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). NHIS is a nationally representative survey that collects data on selected health topics. Although MEPS does not capture information on smoking, self-reported smoking variables are available for a subset of adult NHIS participants (the Adult Sample File) and can be merged with MEPS data. We used responses to the question "Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your entire life?" to differentiate between ever smokers and nonsmokers. We excluded from the analysis sample respondents with missing data on smoking variables (≈1% of respondents aged ≥18 years and all respondents aged <18 at the time of the NHIS interview) and those who did not receive Medicaid coverage. Our final MEPS-NHIS population included 1,588 adults with weighting variables that allowed us to generate nationally representative estimates of the adult, civilian, noninstitutionalized Medicaid population (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Adult MEPS-NHIS (2001 and 2002) and BRFSS (1998-2000) Medicaid Recipients With Data on Smoking Statusa

| Characteristic | MEPS-NHIS | BRFSS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Nonsmokers (n = 768) | Ever Smokers (n = 820) | Nonsmokers (n = 7,701) | Ever Smokers (n = 8,500) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 21 | 33 | 23 | 32 |

| Female | 79 | 67 | 77 | 68 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 32 | 60 | 32 | 58 |

| Black | 34 | 23 | 28 | 21 |

| Hispanic | 26 | 12 | 35 | 17 |

| Asian | 6 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| Other | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| Mean age, y | 36 | 40 | 36 | 38 |

| Region of residence | ||||

| Northeast | 20 | 19 | 36 | 29 |

| Midwest | 21 | 24 | 11 | 18 |

| South | 35 | 38 | 28 | 28 |

| West | 24 | 18 | 25 | 25 |

| Weight category | ||||

| Underweight | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Normal | 24 | 31 | 33 | 37 |

| Overweight | 36 | 31 | 29 | 30 |

| Obese | 36 | 34 | 30 | 26 |

| Missing data | 2 | 1 | 6 | 3 |

| Education | ||||

| Less than high school graduate | 35 | 34 | 33 | 38 |

| High school graduate | 56 | 58 | 61 | 58 |

| College graduate | 9 | 8 | 6 | 4 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 34 | 24 | 37 | 32 |

| Widowed | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 |

| Divorced/separated | 24 | 35 | 18 | 27 |

| Single | 39 | 38 | 40 | 37 |

Abbreviations: MEPS, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey; NHIS, National Health Interview Survey; BRFSS, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

All data are percentages, except age.

Before constructing our national model, we used the Medical Care component of the Consumer Price Index to inflate all MEPS annual medical spending data to 2004 dollars.

State-level representative data

The BRFSS is a state-based telephone survey of the adult (aged ≥18), noninstitutionalized population that tracks health risks in the United States. The most recent BRFSS surveys do not allow for stratifying participants by type of health insurance. This information was, however, available before 2001. Therefore, we used 1998-2000 BRFSS data to predict state-level medical expenditures for the Medicaid population. Information about BRFSS is available at www.cdc.gov/BRFSS/. Although BRFSS does not collect medical expenditure data, it includes information about each participant's smoking status, insurance status (before 2001), and sociodemographic characteristics (such as race/ethnicity, sex, and education). Because these variables match those from MEPS-NHIS, we were able to construct an expenditure prediction model with MEPS-NHIS data and use the results to generate expenditure estimates for smokers and nonsmokers on the basis of state-representative population characteristics of BRFSS participants.

As we did with our MEPS-NHIS restrictions, we excluded those with missing smoking data (≈1%) and those who did not receive Medicaid coverage. Our final BRFSS population included 16,201 adults with weighting variables that allowed us to generate state-representative estimates of the adult, noninstitutionalized Medicaid population (Table 1).

Estimating state-specific smoking-attributable medical expenditures for the Medicaid population involved 3 steps. First, we used MEPS-NHIS data to create a model that predicts annual medical expenditures for Medicaid recipients as a function of smoking status, body weight, and sociodemographic characteristics. Second, we used state-representative BRFSS data and results from our MEPS-NHIS national model to estimate the fraction of medical expenditures for Medicaid recipients that was attributable to smoking for each state. Third, we multiplied these fractions by previously published estimates of state-specific Medicaid expenditures to compute smoking-attributable Medicaid expenditures for each state. These steps are described in detail below.

MEPS-NHIS national model

We used a 4-part regression model to predict annual medical expenditures for each MEPS-NHIS Medicaid recipient. The 4-part regression approach was pioneered by authors of the RAND Health Insurance Experiment to control for several unique characteristics of the medical expenditures distribution and is now commonly applied to medical expenditures data (12,13). The model estimates predicted expenditures by using the following functional form: EXP = Pr(C × EXPIP + [1 − C]EXPNIP ), where EXP represents predicted annual expenditures; Pr represents the predicted probability of positive medical expenditures during the year and is estimated with a logistic regression model; C represents the conditional probability of positive inpatient expenditures, given positive expenditures, and is estimated with a logistic regression model; EXPIP represents ordinary least squares (OLS)-predicted medical expenditures, given positive inpatient expenditures during the year; and EXPNIP represents OLS-predicted medical expenditures, given positive expenditures but no inpatient expenditures.

All OLS regression models are estimated on the logged expenditure variable to adjust for the skewness in annual expenditures (mean annual expenditures are significantly greater than the median). Logged expenditures are converted back to expenditures by using the homoscedastic smearing factor (14).

Including dummy variables that indicate smoking status (ever smoked set equal to 1 and the referent group, never smoked, set equal to 0) in each regression model allowed us to quantify the effect of smoking on annual medical expenditures. In addition to smoking status, all regressions controlled for other variables assumed to influence annual medical expenditures, including self-reported body weight, sex, race/ethnicity, age, region of residence, education, and marital status. Regression models were estimated by using SUDAAN version 8 (RTI International, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina) to control for the complex survey design used in MEPS-NHIS. Table 2 presents results from the 4-part regression model.

Table 2.

Four-Part Model Regression of the Effect of Smoking on Annual Medical Expenditures

| Variable | Correlation (Standard Error) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Probability of Positive Expenditures | Probability of Positive Inpatient Expenditures | Logged Expenditures for Users of Inpatient Services | Logged Expenditures for Nonusers of Inpatient Services | |

| Intercept | 4.19 (1.62) | −1.51 (1.21) | 9.39 (0.80) | 5.41 (0.70) |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Nonsmoker | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Ever smoker | 0.06 (0.24) | 0.22 (0.14) | 0.13 (0.11) | 0.05 (0.12) |

| Weight category | ||||

| Underweight | 0.06 (0.89) | 0.35 (0.56) | 0.64 (0.51) | 0.45 (0.38) |

| Normal weight | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Overweight | −0.08 (0.27) | −0.24 (0.27) | −0.16 (0.20) | −0.04 (0.16) |

| Obese | 0.28 (0.26) | 0.34 (0.26) | −0.02 (0.20) | 0.21 (0.13) |

| Missing data | −0.88 (0.48) | −1.71 (0.72) | 0.62 (0.22) | 0.79 (0.34) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Female | 0.81 (0.24) | −0.29 (0.24) | 0.01 (0.16) | 0.33 (0.18) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Black | −0.79 (0.30) | −0.34 (0.22) | −0.26 (0.16) | −0.57 (0.18) |

| Hispanic | −0.85 (0.28) | −0.08 (0.26) | −0.19 (0.13) | −0.55 (0.17) |

| Asian | −1.17 (0.54) | −0.72 (0.63) | −0.76 (0.35) | −0.85 (0.39) |

| Other | −0.96 (0.70) | −0.26 (0.59) | 0.59 (0.36) | 0.62 (0.30) |

| Age | −0.22 (0.10) | −0.04 (0.06) | −0.01 (0.04) | 0.01 (0.04) |

| Age squared | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | −0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) |

| Region of residence | ||||

| Northeast | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Midwest | −0.22 (0.40) | 0.17 (0.28) | 0.23 (0.17) | 0.14 (0.25) |

| South | −0.33 (0.33) | 0.37 (0.24) | 0.10 (0.15) | 0.19 (0.20) |

| West | 0.12 (0.31) | −0.17 (0.28) | 0.20 (0.20) | 0.09 (0.21) |

| Education | ||||

| Less than high school diploma | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| High school diploma | 0.37 (0.22) | 0.18 (0.19) | −0.03 (0.12) | 0.15 (0.12) |

| College | 0.87 (0.65) | 0.06 (0.31) | −0.21 (0.24) | 0.03 (0.25) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Widowed | 0.44 (0.77) | 0.28 (0.48) | 0.24 (0.28) | 0.71 (0.33) |

| Divorced/separated | 1.30 (0.30) | −0.05 (0.21) | 0.07 (0.16) | 0.24 (0.13) |

| Single | 0.35 (0.22) | −0.09 (0.21) | 0.01 (0.14) | 0.19 (0.14) |

| Pregnancy | ||||

| Not pregnant | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Pregnant | 3.67 (1.09) | 3.77 (1.17) | −1.69 (0.59) | −0.64 (0.54) |

| R 2 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.17 |

BRFSS state-level estimates

We used the coefficient estimates from the MEPS-NHIS models to predict annual medical expenditures for each BRFSS Medicaid recipient. To do this, we multiplied each person's characteristics (the independent variables) by his respective coefficients generated from the 4 MEPS-NHIS regression models and combined the results with the equation above. Using the BRFSS weighting variables and each person's predicted medical expenditures, we computed total predicted medical expenditures for each state's Medicaid population.

We estimated smoking-attributable medical expenditures as the difference between predicted expenditures for ever smokers and predicted expenditures for nonsmokers, leaving all other variables unchanged. This method allowed us to isolate the effect of smoking while maintaining any other population characteristics that may contribute to higher annual medical expenditures among smokers.

For the Medicaid population in each state, the percentage of aggregate medical expenditures attributable to smoking was calculated by dividing aggregate predicted expenditures attributable to smoking by total predicted expenditures for adult Medicaid recipients in each state. Because BRFSS is limited to adults, our results should be interpreted as the fraction of adult medical expenditures that are attributable to smoking among adults in each state.

Estimating total and public-sector expenditures

For a variety of reasons, including the lack of data on institutionalized populations, MEPS national spending estimates (and state-level spending estimates based on MEPS) underestimate actual US health care spending (15). Therefore, to quantify annual adult smoking-attributable medical expenditures for each state, we multiplied our state-by-state smoking-attributable fractions by published estimates of 2001 state-specific Medicaid expenditures, available from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (16). We used 2001 because it is the most recent year that annual, state-specific Medicaid expenditure estimates are available. To match our regression population, we limited Medicaid expenditures to those accrued by adult recipients (≥18 years). We then inflated medical expenditure estimates to 2004 by using a national adjustment factor (1.31). This adjustment factor, calculated as the ratio of 2004 projected expenditures (actual expenditures not yet available) to 2001 actual expenditures, was based on data from Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services National Health Expenditure Accounts, generally considered the standard for measuring annual health care spending (17).

Results

State-specific estimates of smoking prevalence among Medicaid recipients vary considerably across states and range from 35% (Mississippi) to 80% (New Hampshire) (Table 3). Nationally, approximately 11% (95% confidence interval, 0.4%-17.0%) of adult Medicaid expenditures are attributable to smoking. At the state level, smoking-attributable fractions range from 6% (New Jersey) to 18% (Arizona and Washington).

Table 3.

Smoking Prevalence and Estimated Fraction and Total Annual Medicaid Expenditure Attributable to Smoking, by State

| State | Smoking Prevalence, % | SAF, %a | SAE, million, 2004 $ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 52 | 9 | 285 |

| Alaska | 68 | 15 | 67 |

| Arizona | 49 | 18 | 377 |

| Arkansas | 54 | 11 | 167 |

| California | 45 | 11 | 2,254 |

| Colorado | 61 | 17 | 338 |

| Connecticut | 49 | 7 | 249 |

| Delaware | 58 | 10 | 55 |

| District of Columbia | 51 | 11 | 95 |

| Florida | 46 | 11 | 951 |

| Georgia | 42 | 10 | 372 |

| Hawaii | 62 | 11 | 69 |

| Idaho | 62 | 14 | 97 |

| Illinois | 58 | 11 | 905 |

| Indiana | 68 | 15 | 521 |

| Iowa | 61 | 10 | 166 |

| Kansas | 54 | 12 | 171 |

| Kentucky | 65 | 12 | 390 |

| Louisiana | 43 | 12 | 364 |

| Maine | 63 | 14 | 190 |

| Maryland | 51 | 12 | 386 |

| Massachusetts | 53 | 11 | 696 |

| Michigan | 64 | 13 | 727 |

| Minnesota | 54 | 11 | 423 |

| Mississippi | 35 | 9 | 197 |

| Missouri | 66 | 14 | 514 |

| Montana | 70 | 15 | 70 |

| Nebraska | 64 | 15 | 167 |

| Nevada | 62 | 11 | 66 |

| New Hampshire | 80 | 15 | 103 |

| New Jersey | 36 | 6 | 309 |

| New Mexico | 50 | 12 | 159 |

| New York | 54 | 11 | 3,343 |

| North Carolina | 63 | 11 | 622 |

| North Dakota | 63 | 12 | 53 |

| Ohio | 65 | 13 | 1,171 |

| Oklahoma | 58 | 12 | 233 |

| Oregon | 67 | 15 | 290 |

| Pennsylvania | 70 | 11 | 849 |

| Rhode Island | 48 | 8 | 94 |

| South Carolina | 41 | 11 | 336 |

| South Dakota | 69 | 16 | 68 |

| Tennessee | 58 | 11 | 443 |

| Texas | 43 | 11 | 987 |

| Utah | 54 | 14 | 149 |

| Vermont | 67 | 15 | 74 |

| Virginia | 58 | 11 | 294 |

| Washington | 67 | 18 | 464 |

| West Virginia | 67 | 11 | 180 |

| Wisconsin | 63 | 13 | 440 |

| Wyoming | 62 | 16 | 40 |

| US total | 51 | 11 | 21,951 |

Abbreviations: SAF, smoking-attributable fraction; SAE, smoking-attributable expenditure.

Estimates for states are based on Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System state-representative data and the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey and National Health Interview Survey (MEPS-NHIS) national model. The fraction for the United States as a whole is based solely on the MEPS-NHIS national model.

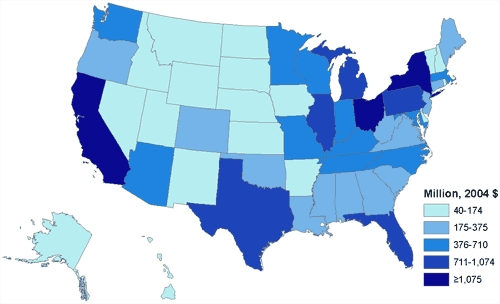

Smoking-attributable medical expenditures in the adult Medicaid population total $22 billion. State-level smoking-attributable medical expenditures among adult Medicaid recipients range from $40 million (Wyoming) to $3.3 billion (New York) (Figure).

Figure 1.

State-by-state distribution of Medicaid smoking-attributable medical expenditures.

Discussion

The 2000 Public Health Service (PHS) clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco dependence recommends individual, group, and telephone counseling, as well as 5 medications (18). Treating tobacco dependence is more cost-effective than commonly covered preventive services such as mammography or treatment of mild to moderate hypertension (19). In 2002, however, only 10 states reported using the 2000 PHS guideline to design treatment benefits and programs for Medicaid recipients or to train Medicaid health care providers. Moreover, only 5 states required providers or health plans to document tobacco use in patients' medical charts, and only 2 states offered all counseling and pharmacotherapy treatments recommended by the guideline to their Medicaid recipients (20).

The growth rate in Medicaid expenditures has led the National Governors Association to propose a bipartisan plan to reform the program. A key element of this plan is to make Medicaid more effective and efficient by developing policies that will "maintain or even [improve] health outcomes while potentially saving money for both the states and the federal government" (6). One way to improve the health of Medicaid recipients and potentially reduce the rate of growth in Medicaid program expenditures is by covering PHS-recommended treatments, including individual and group telephone counseling and approved drugs (9,21-24).

Strengths and limitations

The MEPS-NHIS national model that was used to calculate our state-level estimates is an improvement on a previous study that used data from the 1987 National Medical Expenditure Survey (NMES) to estimate smoking-attributable Medicaid expenditures (11). Results from the 1987 NMES are dated, and unlike NHIS, many of the key smoking variables that NMES used were imputed (25). Using recent data and actual, as opposed to imputed, smoking information in our calculations provides states with updated and accurate information that may better inform policy decisions. In addition, these differences may, in part, explain why the nationwide Medicaid smoking-attributable fraction of 11.0% is more conservative than the previous estimate of 14.5% generated for 1993 (11). Other changes that may account for the difference in our estimated smoking-attributable fraction include potential changes in the number of people treated for smoking-related illness from 1993 to 2002 and any change in treatment disposition from inpatient to outpatient care. Finally, our estimates differ from previous estimates, and probably understate Medicaid smoking-attributable expenditures, because they exclude expenditures for nursing home care, which are not available in the MEPS-NHIS model.

Despite these strengths, our study has several limitations. First, both the MEPS-NHIS and BRFSS are limited to noninstitutionalized populations, but we apply the resulting smoking-attributable fractions to expenditure estimates that include both institutionalized and noninstitutionalized populations. If these fractions are different for the institutionalized population, our expenditure estimates would be biased. Second, data limitations precluded us from quantifying smoking-attributable medical expenditures for smokers younger than 18 years and nonsmokers exposed to secondhand smoke. The effects of secondhand smoke on children's health are considerable (7). Secondhand smoke exposure can lead to acute lower respiratory infections, such as bronchitis and pneumonia in infants and young children, and can cause children who already have asthma to experience more frequent and severe attacks (26). Although health care expenditures attributable to secondhand smoke exposure may be high, quantifying these expenditures is difficult. As a consequence, our estimates understate smoking-attributable expenditures. Third, our analysis is limited to health care expenditures and therefore does not address other expenses (eg, disability, decreased productivity, absenteeism) that result from smoking (7). Finally, because our focus was not to test statistically whether smoking-attributable expenditures were larger in some states than others, we did not calculate standard errors at the state level.

Conclusions

An estimated 443,000 Americans die prematurely each year as a result of smoking or exposure to secondhand smoke (27). Medicaid recipients are disproportionately affected by tobacco-related disease because their smoking prevalence is approximately 53% greater than that of the overall US adult population (10). In addition to the individual health toll, the disproportionately higher smoking prevalence among Medicaid recipients imposes substantial costs on society. We estimate that smoking accounts for approximately 11% of Medicaid program expenditures. To improve the health of Medicaid recipients and potentially reduce the growth rate of expenditures, Medicaid programs in all 50 states and the District of Columbia are encouraged to follow the 2000 PHS guidelines and cover all recommended tobacco-dependence treatments and approved medications (18). The cost-effectiveness of these programs, combined with the high cost of smoking, suggests that such coverage may provide cost savings to the financially strapped Medicaid programs.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. We thank Ann Malarcher, Robert Merritt, Terry Pechacek, Corinne Husten, Rick Hull, and seminar participants at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for helpful comments.

Footnotes

The opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the US Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the authors’ affiliated institutions. Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by any of the groups named above. URLs for nonfederal organizations are provided solely as a service to our users. URLs do not constitute an endorsement of any organization by CDC or the federal government, and none should be inferred. CDC is not responsible for the content of Web pages found at these URLs.

Suggested citation for this article: Armour BS, Finkelstein EA, Fiebelkorn IC. State-level Medicaid expenditures attributable to smoking. Prev Chronic Dis 2009;6(3). http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2009/jul/08_0153.htm. Accessed [date].

Contributor Information

Brian S. Armour, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Email: barmour@cdc.gov, 1600 Clifton Rd NE, Mailstop E-88, Atlanta, GA 30329, Phone: 404-498-3014.

Eric A. Finkelstein, RTI International, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina.

Ian C. Fiebelkorn, RTI International, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina

References

- 1.Smith VK, Moody G. Medicaid in 2005: principles and proposals for reform. A report prepared for the National Governors Association. Lansing (MI): Health Management Associates; 2005. [Accessed June 4, 2008]. http://www.healthmanagement.com/files/NGA-HMA-23Feb2005.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 2.State expenditure report 2006. Washington (DC): National Association of State Budget Officers; 2007. [Accessed June 4, 2008]. http://www.nasbo.org/Publications/PDFs/fy2006er.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 3.The budget and economic outlook: fiscal years 2008 to 2018. Washington (DC): Congressional Budget Office; [Accessed June 4, 2008]. 2008. http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/89xx/doc8917/01-23-2008_BudgetOutlook.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medicaid formula: differences in funding ability by states often are widened. A report to the Honorable Dianne Feinstein, US Senate. Washington (DC): US General Accounting Office; 2003. [Accessed June 4, 2008]. http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d03620.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 5.State expenditure report 2003. Washington (DC): National Association of State Budget Officers; 2004. [Accessed June 4, 2008]. http://www.nasbo.org/Publications/PDFs/2003ExpendReport.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 6.Medicaid reform: statement of Governor Mark R. Warner, chairman, and Governor Mike Huckabee, vice chairman, before the Committee on Finance of the United States Senate. Washington (DC): National Governors Association; Jun 15, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.The health consequences of smoking: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Annual smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and productivity losses — United States, 1997-2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54(25):625–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Issue brief: state employee wellness initiatives. Washington (DC): National Governors Association Center for Best Practices; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pleis JR, Lethbridge-Çejku M. Summary health statistics for US adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2006. Vital Health Stat 10. 2007;10(235):1–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller LS, Zhang X, Novotny T, Rice DP, Max W. State estimates of Medicaid expenditures attributable to cigarette smoking, fiscal year 1993. Public Health Rep. 1998;113(2):140–151. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manning W, Newhouse J, Duan N. Health insurance and the demand for medical care: evidence from a randomized experiment. Am Econ Rev. 1987;77:251–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finkelstein E, Fiebelkorn I, Wang G. National medical spending attributable to overweight and obesity: how much and who's paying? Health Aff (Millwood) 2003;(Suppl):W3-219-26. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manning W. The logged dependent variable, heteroscedasticity, and the retransformation problem. J Health Econ. 1998;17:283–295. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(98)00025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seldon T. Reconciling medical expenditure estimates from the MEPS and the NHA, 1996. Health Care Financ Rev. 2001 ;23(1):161–178. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. FY 2001 Medicaid medical vendor payments by age group of beneficiaries. [Accessed June 4, 2008]. http://www.cms.hhs.gov/medicaid/msis/01_table19.pdf .

- 17.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. National health care expenditures projections: 2004-2014. [Accessed June 4, 2008]. http://www.cms.hhs.gov/NationalHealthExpendData/ downloads/nheprojections2004-2014.pdf .

- 18.Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ, Dorfman SF, Goldstein MG, Gritz ER, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: clinical practice guideline. Rockville (MD): Public Health Service, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eddy DM. David Eddy ranks the tests. Harv Health Lett 1992;(Suppl):10–11. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention State Medicaid coverage for tobacco-dependence treatments — United States, 1994-2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53:54–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warner KE. Smoking out the incentives for tobacco control in managed care settings. Tobacco Control. 1998;7(Suppl):S50–S54. doi: 10.1136/tc.7.2008.s50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Partnership for Prevention. Priorities for America's health: capitalizing on life-saving, cost-effective preventive services. [Accessed June 4, 2008]. http://www.prevent.org/content/view/46/96/

- 23.Hopkins DP, Husten CG, Fielding JE, Rosenquist JN, Westphal LL. Reviews of evidence regarding interventions to reduce tobacco use and exposure to environmental tobacco smoke. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20(2 Suppl):67–87. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00298-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Solberg LI, Maciosek MV, Edwards NM, Khanchandani HS, Goodman MJ. Repeated tobacco-use screening and intervention in clinical practice: health impact and cost effectiveness. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(1):62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cutler DM, Epstein AM, Frank RG, Hartman R, King III, C, Newhouse JP, et al. How good a deal was the tobacco settlement? Assessing payments to Massachusetts. NBER Working Paper. 2000. No. 7747.

- 26.The health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and productivity losses — United States, 2000-2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(45):1226–1228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]