Aboriginal peoples in Canada have been providing health care to children and youth for thousands of years. Not unlike today, Indigenous peoples turned to nature to develop pharmacological solutions to ailments and injuries. This medical know-how has benefited people around the world – ipecac, quinine to treat malaria and vitamin C to treat scurvy are just a few examples. Despite these similarities, there are significant differences between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal conceptions of health.

There are many different Aboriginal groups in Canada, including First Nations, Métis and Inuit peoples. Even within each group, there is a wide variety of cultures, languages and beliefs. Indeed, every separate Nation considers itself to be unique and different from the other Nations, but they share much more in common with each other than with the non-Aboriginal population. One of those commonalities is their holistic approach to health.

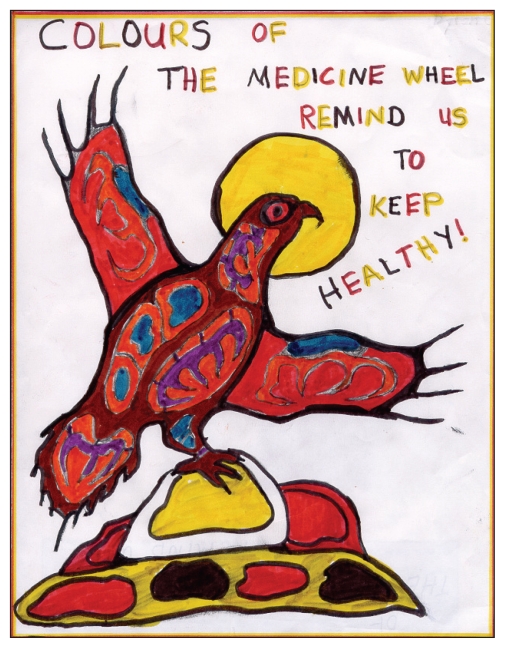

As reflected in the articles in this special issue of Paediatrics & Child Health, Aboriginal peoples believe that health goes beyond the physical body to the spirit, the emotions and the mind. It goes beyond the individual to encompass the relationships one has with family, the community, the world, the spirit and the land. It exists as much in the past and future as it does in the present, so decisions regarding health must be reflective and prognostic at the same time.

Donald Warne (pages 542–544) emphasizes the importance of holism in Aboriginal health by encouraging medical practitioners to treat the whole patient in his/her context. This means understanding that patients may have different concepts and priorities in health care, such as putting as much emphasis on spiritual and emotional health as on physical health. An unfortunate outcome of colonization was an illegitimating or romanticizing of Aboriginal health care in favour of western medical knowledge. Over time, western medicine itself has come to appreciate the wisdom of holistic health care, creating an opportunity to bridge traditional and western medicine to optimize health care outcomes for Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal patients.

We get a very realistic view of the importance of the community on a child’s health in Gloria Nelson and Joyce Bonspiel-Nelson’s commentary (pages 533–535). We learn the stories of how Kanesatake’s youth were affected by the Oka Crisis and the community’s ongoing struggles to deal with the emotional aftermath of an assault on their community. They describe how a traumatic event can upset the delicate balance between a healthy and unhealthy community. They argue that the long-lasting effects of this trauma have infiltrated all aspects of their community and have affected its most innocent members, the children and young people.

Jeannine Carriere (pages 545–548) outlines the importance of family, both natural and adoptive, in shaping the identities of Aboriginal children and young people placed for adoption. She makes the case that our genetic code does more than just shape our physical bodies – it embodies the spirit, knowledge and emotions of our ancestors. Children who are adopted may be placed in loving homes, but only the natural family can affirm and support the growth of this natural shaping of personal identity. Carriere makes the case that open adoption is essential for Aboriginal children because they can draw mutually upon the strength of their birth family and community and their adoptive family and community to shape an integrated and healthy identity. Her work indicates how cutting off children and youth from knowledge of who they are and where they come from affects their physical and emotional health.

Trudy Lavallee’s advocacy piece (pages 527–529) reminds us of how bureaucratic wrangling on issues that appear important to institutions and governments can result in unnecessary tragedies for children and young people. She tells the story of how Jordan, a young boy born with complex medical needs, remained unnecessarily in hospital for over two years while two federal government departments argued over who should pay for his home care needs. They argued over costs as modest as a showerhead while Jordan remained in hospital. The jurisdictional dispute was settled after legal action was initiated by First Nations but, sadly, not in time for Jordan to spend a part of his short life in a family home. He died without having lived in a family home – not because his health care needs demanded it or because there was not a suitable home to care for him, but because two government departments sharing part of an $8 billion surplus budget put their needs first and Jordan’s second.

Jocelyn and Karen Formsma (page 531) emphasize that young people need to make an informed choice to be healthy. They must have access to information, confront stereotypes, get grounded in concepts of health that reflect their identities and take responsibility for having a healthy body, mind, spirit and emotions. Improved health for Aboriginal peoples begins with a conviction that good health is possible and worth working for. Then it needs to be supported by equitable and culturally based health care.

Achieving equitable and culturally based health care means that organizations and individuals must ask courageous questions and pursue the answers with vigour. Elizabeth Moreau (pages 536–538) describes when the Canadian Paediatric Society (CPS) asked if it could do more to support Aboriginal children and answered a resounding YES. This is perhaps not so unique, but the respectful process that followed is. Instead of drumming up solutions on its own, the CPS went out and spoke to Aboriginal health organizations to find out what solutions they had and how the CPS could support those solutions. This culminated in a joint envisioning of Aboriginal children’s health and a health summit to initiate a movement of change in health care itself to better support Aboriginal children. As this article notes, non-Aboriginal organizations need not stress over finding solutions to the grave risk factors that Aboriginal children and young people face alone – simply by asking Aboriginal peoples, many of the solutions are found, and together they can be implemented.

This issue of Paediatrics & Child Health has strikingly different articles from those normally seen in medical journals. There is no talk of bacteria, no talk of laboratory investigations and no talk of computed tomography scans. The only thing that is ‘sick’ is the overall approach to delivering health care to Aboriginal people. There is too much focus on the physical without regard for the spiritual, the mental and the emotional. Many Aboriginal physicians trained in a western approach struggle with this battle everyday. Our tools typically attack the physical. We have few tools to tackle the spiritual, emotional and mental issues, and that is the reason the system does not work for Aboriginal people.

Some look at the landscape of health risks faced by Aboriginal children and young people in Canada and wonder if anything can be done to change it. The good news is, there is. By reconceptualizing health from a holistic perspective, integrating the best of traditional and western medicine, providing equal access to resources and affirming community decision-making in health care, substantial progress can be made. A major aspect in this approach would be to have Aboriginal communities make their own decisions regarding their health care delivery. Health care for Aboriginals can and should be run by Aboriginal people starting from the core model of traditional health care delivery to having a complementary mixture of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal staff. These simple steps would mean healthier Aboriginal children, young people and communities, but they also would put in place a foundation for western medicine to learn from Aboriginal peoples. Just as in the beginning, western medicine can turn to Aboriginal peoples for solutions to some of the health care challenges facing people of all cultures, but this time they can acknowledge the source of the wisdom.

By Dylon, Notre Dame du Nord, Quebec