Abstract

Objective To evaluate whether systemic corticosteroids improve symptoms of sore throat in adults and children.

Design Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data sources Cochrane Central, Medline, Embase, Database of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE), NHS Health Economics Database, and bibliographies.

Outcome measures Percentage of patients with complete resolution at 24 and 48 hours, mean time to onset of pain relief, mean time to complete resolution of symptoms, days missed from work or school, recurrence, and adverse events.

Results We included eight trials, consisting of 743 patients in total (369 children, 374 adults). 348 (47%) had exudative sore throat, and 330 (44%) were positive for group A β-haemolytic streptococcus. In addition to antibiotics and analgesia, corticosteroids significantly increased the likelihood of complete resolution of pain at 24 hours (four trials) by more than three times (relative risk 3.2, 95% confidence interval 2.0 to 5.1), and at 48 hours (three trials) to a lesser extent (1.7, 1.3 to 2.1). Corticosteroids (six trials) reduced mean time to onset of pain relief by more than 6 hours (95% confidence interval 3.4 to 9.3, P<0.001), although significant heterogeneity was present. The mean time to complete resolution was inconsistent across trials and a pooled analysis was not undertaken. Reporting of other outcomes was limited.

Conclusions Corticosteroids provide symptomatic relief of pain in sore throat, in addition to antibiotic therapy, mainly in participants with severe or exudative sore throat.

Introduction

Sore throat is a common reason for people to seek medical care, accounting for about one in 50 of all ambulatory care visits and resulting in considerable costs.1 2 3 4 Most sore throats are self limiting5 and are caused by rhinovirus, coronavirus, or adenovirus. Group A β-haemolytic streptococcus is responsible for about 10% of sore throats in adults and 15–30% of those in children.1 6

Treatment of sore throat with antibiotics provides only modest beneficial effect in reducing symptoms and fever.7 87 8 However, prescribing rates remain disproportionately high.6 High rates of antibiotic prescriptions contribute to antibiotic resistance9 and also lead to the “medicalising” of sore throat, which can result in increased rates of patient (re)attendance.10 11 In developed countries, prescribing is no longer justified to prevent complications from group A β-haemolytic streptococcus infection. Peritonsillar abscess occurs in fewer than two in 10 000 patients presenting with acute respiratory tract infections,12 whereas non-suppurative complications (such as rheumatic fever and glomerulonephritis) are extremely rare.8 13 14

The pressure for clinicians to reduce antibiotic prescriptions for sore throat leaves a therapeutic vacuum. Corticosteroids inhibit transcription of proinflammatory mediators in human airway endothelial cells which cause pharyngeal inflammation and ultimately symptoms of pain.15 Corticosteroids are beneficial in other upper respiratory tract infections such as acute sinusitis, croup, and infectious mononucleosis.16 17 18 We therefore hypothesised that corticosteroids would offer similar symptomatic relief from sore throat because of their anti-inflammatory effects, and undertook a systematic review to examine the effect of systemic corticosteroids on adults and children with sore throat.

Methods

Search strategy and selection

We included only randomised controlled trials comparing systemic corticosteroids with placebo, in children or adults, in outpatient (ambulatory) settings. We also included studies of patients with clinical signs of acute tonsillitis or pharyngitis (inflammation of the tonsils or oropharynx) and patients with a clinical syndrome of “sore throat” (painful throat, odynophagia). We excluded studies of infectious mononucleosis, sore throat following tonsillectomy or intubation, or peritonsillar abscess.

We searched Medline (1966 to 2008), Embase (1983 to 2008), the Cochrane Library including the Cochrane Central register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), the Database of reviews of effectiveness (DARE), and the NHS Health Economics Database from the beginning of each database until August 2008 using a maximally sensitive strategy.19 Terms used included “upper respiratory tract infection”, “pharyngitis”, “tonsillitis”, “sore throat”, and “corticosteroids” (including “dexamethasone”, “betamethasone”, “prednisone”, and all variations of these terms) and viral and bacterial upper respiratory pathogens (full search strategy available from authors). Two authors independently reviewed the title and abstracts of electronic searches, obtaining the full articles to assess for relevance where necessary. Disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third author. We did citation searches of all full-text papers retrieved.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two authors independently assessed study quality and extracted data using an extraction template. Disagreements were documented and resolved by discussion with a third author. We assessed methodological quality of studies by allocation concealment, randomisation, comparability of groups on baseline characteristics, blinding, treatment adherence, and percentage participation.

Primary outcomes included the proportion of participants with improvement or complete resolution of symptoms, mean times to onset of pain relief, and complete resolution of pain. Secondary outcomes included the reduction in pain measured by visual analogue scale, adverse events necessitating discontinuation of treatment, relapse rates, and days missed from school or work. Where necessary, data were extracted from graphs with the Grab It XP Microsoft Excel program (www.datatrendsoftware.com)

We did sensitivity analyses, excluding each study in turn, to determine the stability of the effect. A priori subgroup analyses included age, route of corticosteroid, presence of positive bacterial culture or direct antigen test, and severity of sore throat including presence of exudate. Meta-regression in STATA tested subgroup interaction on the outcomes. We selected the data closest to a single-dose regimen from those studies that used different dosing regimens in a single trial as our conservative strategy. Similarly, if both oral and intramuscular data were available, we used oral data for our overall analysis and intramuscular data for appropriate subgroup analysis.

Data synthesis and analysis

We expressed dichotomous outcomes as relative risks and 95% confidence intervals and expressed continuous variables as weighted mean difference and 95% confidence intervals. If data were sufficient for primary outcomes, we calculated the number needed to treat using the relative risk and the pooled event rates, in addition to the risk difference as calculated in RevMan 4.2. We used the I2 statistic to measure the proportion of statistical heterogeneity for each outcome.20 Where no heterogeneity was present, we undertook a fixed effect meta-analysis. If substantial heterogeneity (I2 above 50%) was detected, we looked for the direction of effect and where applicable used a random effects analysis. We also performed a sensitivity analysis by removing single trials to investigate the extent to which they contributed to the heterogeneity, particularly looking at baseline characteristics including severity.

Results

Study characteristics

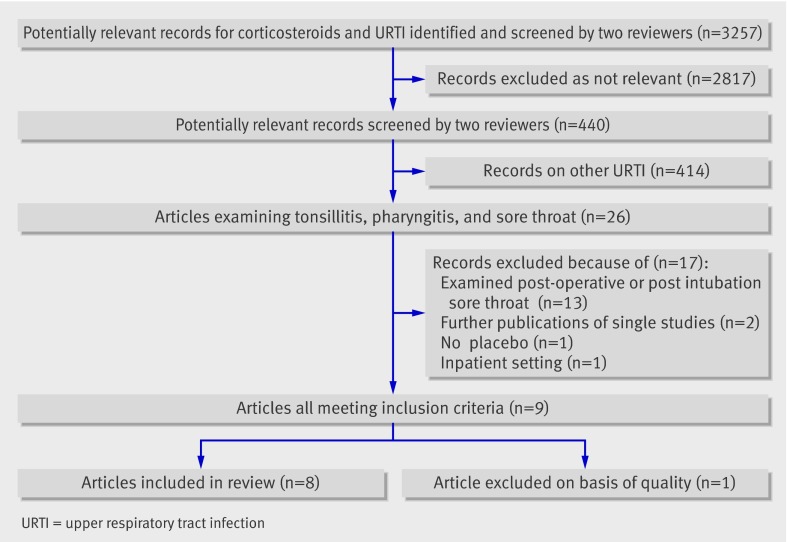

Of 3257 potentially relevant records identified, 26 were relevant to sore throat, tonsillitis, or pharyngitis (fig 1). A further 17 studies were excluded because they examined postoperative or postintubation sore throat (13 studies), included inpatients (one), did not have a placebo group (one), or were duplicate publications (two). Of the nine that met our inclusion criteria, one was excluded for not describing the method of randomisation.21

Fig 1 Flowchart of search results

The eight studies included 743 patients (369 children, 374 adults): 348 (47%) had exudative sore throat, and 330 (44%) were positive for group A β-haemolytic streptococcus. Patients were recruited from emergency department and general practice settings in four countries: United States (five studies), Canada (one), Israel (one), and Turkey (one) (table 1). Corticosteroids used included betamethasone 2 ml (estimated dose 8 mg, one study), dexamethasone (up to 10 mg, six studies; or prednisone 60 mg, one study): doses were reasonably comparable for their potency. Corticosteroids were administered either intramuscularly (three studies), orally (four), or both (one). Six trials used one dose of corticosteroids, and two trials prescribed more than one dose of corticosteroids to a subgroup of participants.w1 w2 In the eight included studies, methodological quality was high with a low risk of bias (for example, all trials reported adequate allocation concealment and clear methods of randomisation). Table 2 reports the specific elements of methodological quality in the selected studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of trials included in meta-analysis (see web appendix for references)

| Study | Age range (mean)* | No of patients analysed | Severity of sore throat | Intervention | Control | Antibiotics used | Analgesia | Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | ||||||||

| O’Brien et al 1993 (US)w8 | 12–65 (26.4) | 26† | 25† | Severe (GABHS not tested, 100% exudative) | Dexamethasone 10 mg (IM) | Saline 1 ml (IM) | Penicillin G or erythromycin | Unregulated, no differences recorded, type not reported | Reduction in pain VAS, time to onset of pain relief, time to complete pain resolution |

| Marvez-Valls et al 1998 (US)w4 | 14-65 (29.1) | 46 | 46 | Severity not stated (53% GABHS‡, 100% exudative) | Betamethasone 8 mg/2 ml§ (IM) | Saline, 2 ml (IM) | Penicillin G or erythromycin (similar proportion in each group) | Unregulated, unrecorded, paracetamol or ibuprofen recommended | Reduction in pain VAS, time to onset of pain relief, time to complete pain resolution, days missed from school or work, percentage of recurrence |

| Wei et al 2002 (US)w6 | ≥15 (28) | 42¶ | 37 | Severity not stated (27% GABHS, 43% exudative) | Dexamethasone 10 mg (PO) + placebo (IM)¶ | Placebo (PO, IM) | Penicillin V or erythromycin | Paracetamol for first 24 hours as required, no differences recorded | Reduction in VAS, complete pain resolution at 24 hours, return to normal activity, ability to take liquids and solids, percentage of recurrence |

| Bulloch et al 2003 (Canada)w3 | 5-16 (9.74) | 92 | 92 | Severity not stated (46% GABHS, 37% exudative) | Dexamethasone, 0.6 mg/kg (PO, maximum 10 mg) | Placebo (PO) | Penicillin V if DAT positive | Unregulated, unrecorded | Reduction in pain VAS, time to onset of pain relief, time to complete pain resolution, percentage of recurrence |

| Olympia et al 2005 (US)w5 | 5–18 (11.9) | 57 | 68 | Severe (56% GABHS, exudative not stated) | Dexamethasone, 0.6 mg/kg (PO, maximum 10 mg) | Placebo (PO) | Penicillin G, erythromycin or azithromycin if DAT positive or culture positive | Unregulated, no differences recorded, paracetamol or NSAIDs recommended | Reduction in pain, McGrath score, time to onset of pain relief, time to complete pain resolution, fever, associated symptoms, need for further medical care |

| Kiderman et al 2005 (Israel)w1 | 18-65 (33.9) | 40 | 39 | Severe (57% GABHS, 87% exudative) | Prednisone, 60 mg for 1 or 2 days (PO)** | Placebo (PO) | Penicillin V, amoxicillin, erythromycin, none at GP’s discretion, or stopped if culture negative | Unregulated, unrecorded | Reduction in VAS score, proportion of individuals being pain-free at various time points, percentage of recurrence, complete pain resolution at 24 and 48 hours, days missed from school or work |

| Niland et al 2006 (US)w2 | 4-21 (median 7.7) | 30†† | 30 | Severity not stated (100% GABHS, 57% exudative) | Dexamethasone, 0.6 mg/kg for 1 day (PO, maximum 10 mg) + 2 days placebo | Placebo (PO) | 50% received IM and 50% received PO antibiotic, type not stated | Unregulated, no differences recorded | Return of general health, return of normal activity level, days missed from school or work, time to complete pain resolution, complete pain resolution at 24 and 48 hours, percentage of recurrence |

| Tasar et al 2008 (Turkey)w7 | 18-65 (31.3) | 31 | 42 | Severity not stated (GABHS not stated, exudative not stated) | Dexamethasone, 8 mg (IM) | Saline (IM) | Azithromycin, 500 mg daily for 3 days | Paracetamol for 3 days as required, unrecorded | Time to onset of pain relief, time to complete pain resolution, complete pain resolution at 24 and 48 hours |

GABHS=group A β-haemolytic streptococcus. IM=intramuscular delivery. PO=oral delivery. DAT=direct antigen test. VAS=visual analogue scale.

*Age in years. Value in parentheses is the mean unless stated otherwise.

†13 participants in each arm available for follow-up at 7 days to determine complete resolution.

‡84% of participants had throat cultures taken, percentage is reported as if all participants had cultures.

§Dose is a best guess from US formularies.

¶Third arm of trial examining IM dexamethasone not included in general analysis.

**Data from two doses of corticosteroid versus one dose not presented separately.

††Third arm of trial evaluating three daily doses of dexamethasone not included in meta-analysis.

Table 2.

Methodological quality of included studies (see web appendix for references)

| Study | Allocation concealment | Randomisation | Comparability of groups at baseline | Blinding | Participation (%) | Provision of care apart from intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O’Brien et al (1993)w8 | Adequate | Random number table | Comparable | Double | 88 | Equal |

| Marvez-Valls et al (1998)w4 | Adequate | Randomised list | Comparable | Double | 100 | Equal |

| Wei et al (2002)w6 | Adequate | Randomisation scheme held at central pharmacy | Comparable | Double | 92.5 | Equal |

| Bulloch et al (2003)w3 | Adequate | Block randomisation, held at central pharmacy | Comparable | Double | 97 | Equal |

| Olympia et al (2005)w5 | Adequate | Block randomisation | Comparable | Double | 83 | Equal |

| Kiderman et al (2005)w1 | Adequate | Random number table | Comparable | Double | 100 | Equal |

| Niland et al (2006)w2 | Adequate | Block randomisation | Comparable, apart from gender, which had no significant effect on results | Double | 93 | Equal |

| Tasar et al (2008)w7 | Adequate | Random number table | Comparable | Double | 100 | Equal |

Outcome measures included complete pain resolution at 24 hours (four studies) and 48 hours (three studies), mean time to onset of pain relief (five), mean time to complete resolution of pain relief (six), reduction in visual analogue scale pain score (five), number of days missed from school or work (three), and recurrence rates (four). All eight trials prescribed antibiotics to both intervention and placebo groups and allowed simple analgesia. In four trials, analgesia use was recorded, which was not significantly different between placebo and corticosteroid groups. Two trials restricted analgesia to paracetamol for 24 hours or 72 hours, recording no difference in usew6 and not reporting usew7 respectively. Four trials reported outcomes separately for patients positive and negative for bacterial pathogens.w3-w6

Complete resolution of pain at 24 or 48 hours

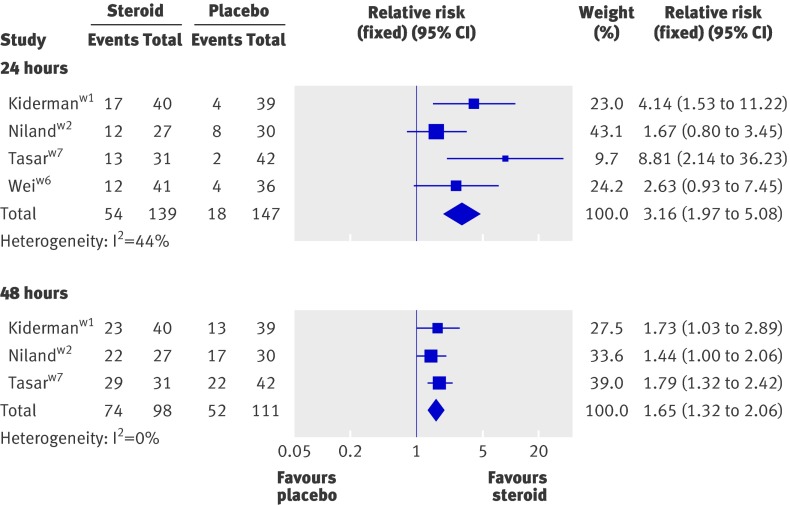

In a pooled analysis of four trialsw1 w2 w6 w7 patients treated with corticosteroids were three times more likely to have complete resolution of pain at 24 hours (relative risk 3.2, 95% confidence interval 2.0 to 5.1, P<0.001, I2=44%) (fig 2). The number needed to treat was 3.7 (2.8 to 5.9). Significant effects were recorded in adult patients only (relative risk 4.3, 2.3 to 8.1, P<0.001)w1 w6 w7 and in those receiving oral corticosteroids only (2.6, 1.6 to 4.3, P<0.001).w1 w2 w6 Data were insufficient to undertake further subgroup analysis.

Fig 2 Effect of corticosteroids on number of patients experiencing complete pain relief at 24 and 48 hours. See web appendix for references

In three trialsw1 w2 w7 corticosteroids also increased the likelihood of complete resolution of pain at 48 hours (relative risk 1.7, 95%CI 1.3 to 2.1, P<0.001), number needed to treat was 3.3 (2.4 to 5.6) (fig 2). Results were similar in trials with adult patients only (1.8, 1.3 to 2.3, P<0.001)w1 w7 and in those receiving oral corticosteroids only (1.6, 1.2 to 2.1, P=0.004).w1 w2

Mean time to onset of pain relief

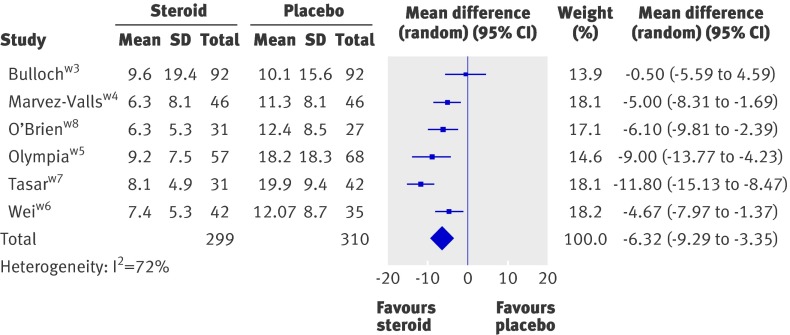

Six trials reported the mean time to onset of pain relief, which occurred at an average of 6.3 hours earlier with corticosteroids than without (95% CI 9.3 to 3.4, P<0.001) (fig 3).w3-w8 The wide variation in individual response times caused high heterogeneity (I2=73%). A sensitivity analysis, which excluded each trial in turn, demonstrated a range of weighted mean difference of 5.1 to 7.2 hours, but no loss of significance. The majority of the heterogeneity arose from the trial by Tasar et al, which showed the largest benefit of corticosteroids with small standard deviations.w7 Removal of this trial from the meta-analysis gave a mean time to onset of pain relief 5.1 hours earlier in patients given corticosteroids.

Fig 3 Effect of corticosteroids on mean time to onset of pain relief in hours. See web appendix for references

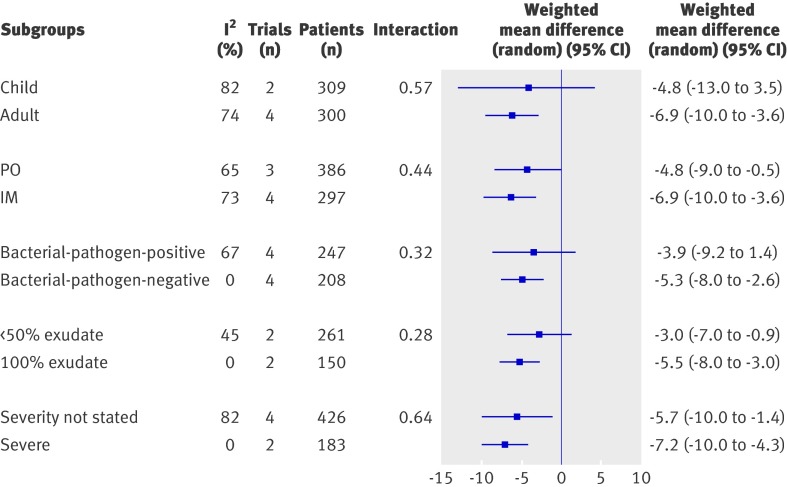

In patients with an exudative sore throat, corticosteroids also reduced the mean time to onset of pain relief (weighted mean difference 6.2 hours, 8.4 to 4.0). Similarly, we recorded a reduction in mean time to pain relief in sore throat that was bacterial pathogen positive (5.3, 8.0 to −2.6) and in trials selecting for severe sore throat (7.2, 10.1 to 4.3). All three categories of sore throat (exudative, bacterial pathogen positive, and severe) were significant (P<0.001) with no heterogeneity (I2=0) (fig 4).

Fig 4 Effect of corticosteroids on mean time to onset of pain relief analysed by subgroup using meta-regression. PO=oral delivery. IM=intramuscular delivery

The direction of effect for mean time to onset of pain relief was similar in trials with adults only, in trials with intramuscular and oral routes of steroid administration, and in trials in which severe sore throat was not selected. The effect on children only, those with less than 50% exudative sore throat, and non-bacterial pathogen positive only did not reach significance .We did not find significant changes in mean time to onset of pain relief in trials with children only, trials with less than 50% exudative sore throat, and in the subgroup of patients with sore throat not positive for bacterial pathogens. Meta-regression analysis revealed no significant differences across all subgroups (fig 4).

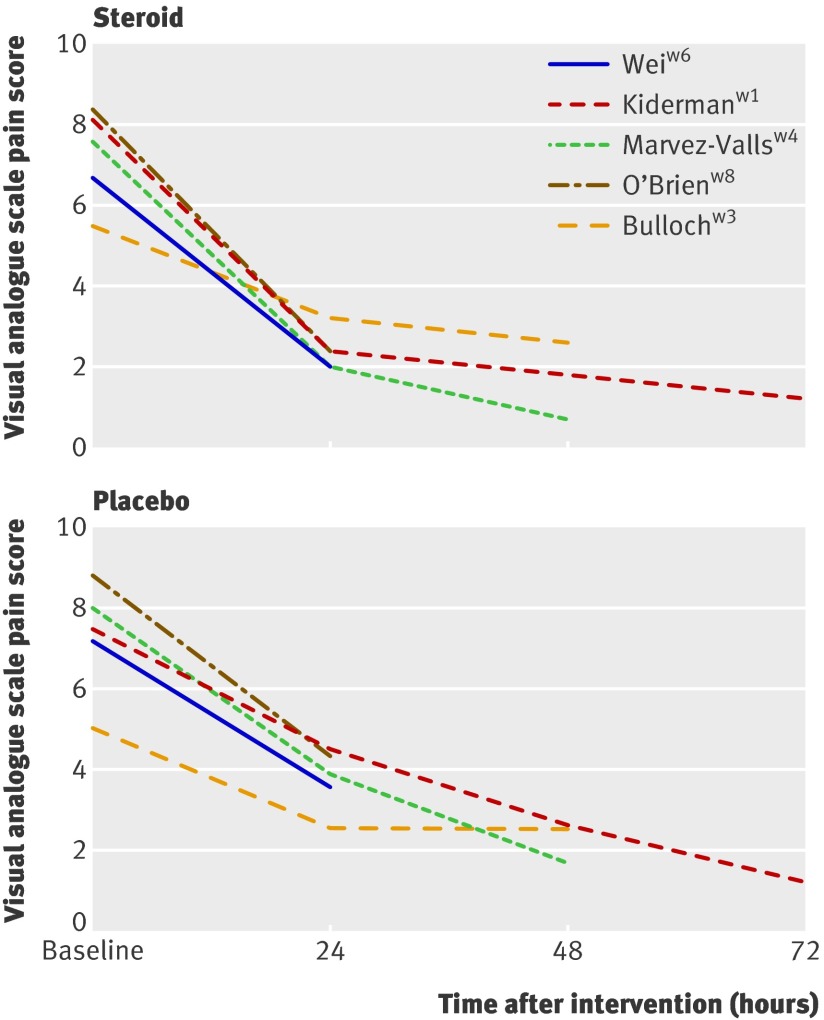

Figure 5 shows the change in visual analogue scale at baseline to 72 hours. The data from Bulloch et al’s trial display the lowest baseline visual analogue scale score (that is, less severe) and the least response at 24 and 48 hours.w3 This finding is reflected in the non-significant effect (and the smallest effect) observed in the mean time to onset of pain relief for this trial.

Fig 5 Mean pain score on visual analogue scale at baseline and after corticosteroids or placebo. See web appendix for references

Time to complete resolution of symptoms

Five trials assessed the mean time to complete resolution of pain.w3-w5 w7 w8 High heterogeneity prevented pooling: three studies showed a benefit of corticosteroids,w5 w7 w8 and two showed non-significant effects in opposing directions. Time to complete resolution ranged from 15 to 45 hours in the corticosteroid group and 35 to 54 hours in the placebo group.

Adverse events, relapse rates, and days missed from school or work

Only one trialw5 of 125 participants reported adverse events: five patients (three steroid, two placebo) were hospitalised for fluid rehydration, and three patients developed peritonsillar abscess (one steroid, two placebo). Three studies reported no significant differences in days missed from school or work.w1 w2 w4 Four trials reported no difference in the incidence of recurrent symptomsw1-w4 (measured between 5 days and 1 month after treatment), whereas one trial found significantly increased recurrence in the placebo group.w6

Discussion

Corticosteroids significantly increase the proportion of patients with sore throat who will experience complete resolution of pain at both 24 and 48 hours. Fewer than four patients need to be treated to prevent one patient continuing to experience a painful sore throat at 24 hours. Although corticosteroids decreased the mean time to onset of pain relief by 6 hours, pooled analysis showed significant heterogeneity. All effects were in addition to antibiotic use.

We found that the effects of corticosteroids on mean time to onset of pain relief were homogenous in severe, exudative, or bacterial pathogen positive sore throat alone. Our data do not support an effect in mild sore throat because only one study included patients with milder symptoms at baseline, and showed no significant effect. A meta-regression analysis showed no evidence of interactions across different subgroups (such as route of corticosteroid, age, severity) on the outcome of mean time to onset of pain relief.

The effects of corticosteroids on resolution of pain were most apparent in the initial 24 hours, which implies that a single dose of corticosteroids may be sufficient. This effect is similar to that seen in croup where a single dose is generally adequate.17 Furthermore, the one trial comparing three daily doses of dexamethasone with a single dose found no difference in effect.w2

Limitations

Our analysis had some limitations. Firstly, and most importantly, all of the included trials provided antibiotics to patients in both corticosteroid and placebo groups (either to all participants, or to all participants with group A β-haemolytic streptococcus culture or a positive rapid antigen test). Therefore, we do not know the effects of corticosteroids on sore throat symptoms independent of antibiotics.

Secondly, various outcome measures were reported, in some cases with inadequate reporting, no standard deviations, or use of graphical representation only. Thirdly, significant heterogeneity occurred in some of our analyses; this was attributable mainly to one trial,w7 which demonstrated increased benefit of corticosteroids with small standard deviations. However, our results remained robust to the removal of this trial.

Fourthly, the outcome measure of mean time to onset of pain relief was limited by recall bias, because the estimation of the time when pain relief begins relies on patients’ subjective recall and recording. The mean time could also be skewed by a few participants who had sore throat pain for especially long or short periods. A median time may have been more appropriate, although there were insufficient data for us to calculate this.

Finally, the limited number of trials meant that we were unable to assess publication bias using funnel plots, although we attempted to address this issue by using citation searching. Included studies were also underpowered to detect rare adverse effects of corticosteroid therapy, as well as relapse rates and days missed from work or school.

Implications for practice

Our findings suggest that in patients with severe or exudative sore throat, pain can be reduced and resolution hastened by use of corticosteroids in conjunction with antibiotic therapy. Current UK practice is to assess the likelihood of group A streptococcus infection using the Centor criteria22 (tender lymphadenopathy, exudate, fever, absence of cough). Our research suggests that patients with severe or high Centor scoring sore throat would benefit from a single dose of corticosteroids. The use of corticosteroids will triple the likelihood of resolution at 24 hours and hasten this resolution by more than 6 hours, even in patients who have also been given antibiotics and analgesics.

Our finding that the duration of pain is reduced by 6 hours seems modest. However, the decision to use any treatment involves balancing the benefit and potential harms of the therapy. Although our included studies were not sufficiently powered to detect adverse effects of short courses of oral corticosteroids, the treatment has been associated with little morbidity in the management of croup and asthma. Moreover, treatment is commonplace for other short lasting illnesses that cause distress for patients, such as antibiotics for cystitis. In this context, onset of pain relief 6 hours earlier may be an acceptable benefit to many patients, and may prevent antibiotic use (particularly in the context of delayed prescriptions).

We could not fully assess the best type, route, or dosing regimen of corticosteroids because of small sample sizes. Two studies which directly compared intramuscular and oral routes found no differences, and our subgroup comparison also showed no differences.23 w6 Therefore, the current evidence shows that oral corticosteroids are as beneficial as intramuscular preparations and are more acceptable to patients.

In the included studies antibiotic use could reflect clinical practice in North America, where most of the trials were performed. Prescribing and consultation patterns may be different in the UK or Europe, where no trials were undertaken. Therefore, additional trial data are warranted in European populations before the results can be deemed generalisable. We are also unsure of the benefits of corticosteroids in children because of the limitations on the reporting in these trials.

Recommendations for research

Future trials should be in antibiotic naïve patients, and include the number of patients who have resolution of symptoms at 24, 48, and 72 hours and standardised pain scores. They should be large enough to adequately assess adverse events and days missed from school or work. Use of the Centor criteria at baseline will facilitate classification of severity. Any effects of corticosteroids on potentially reducing antibiotic use will need to be balanced by the risk of medicalising what is usually a self limiting and short lasting infection. Further research should focus on the effects of corticosteroids on antibiotic use as well as longer term measures such as reattendance with recurrent sore throats. Additionally, further trials in children are warranted that adequately report the outcome measures outlined above.

Summary

Corticosteroids, in addition to antibiotics, provide symptomatic relief of pain in sore throat. In the current analysis, most participants had severe or exudative sore throat. Subgroup analyses showed no significant differences between trials, including severe sore throats and those in which severity was not stated. We found no evidence of significant benefit in children. Further research should target corticosteroid use in antibiotic-naïve patients.

What is already known on this topic

Corticosteroids are beneficial for symptoms of upper respiratory tract infections

Sore throat is a common condition in primary care

Recent guidelines recommend that antibiotics should not be prescribed for sore throat

What this study adds

At 24 hours, patients with severe sore throat who are given corticosteroids in addition to antibiotics are three times more likely to report complete resolution of symptoms than those who do not receive corticosteroids

Corticosteroids also reduce the time to mean onset of pain relief in this patient group by about 6 hours

The effect of corticosteroids independent of antibiotics is unknown and should be the focus of future research

We thank Nia Roberts, Ed Diggines, and Emma Meats for their assistance with literature searching and organisation.

Contributors: GH performed the study appraisal, meta-analysis, wrote the first draft of the article, made critical revisions to the article, and is guarantor for this article. MT obtained grant funding, organised the research study, supervised the searching, appraisal, interpretation, and made critical revisions to the article. CH assisted with the searching, appraisal, meta-analysis, and made critical revisions to the article. RP supervised the meta-analysis, revised and commented on various drafts of the article, and provided methodological support. CDM drafted, revised, and commented on various drafts of the article and read and approved the final draft. PG drafted, revised, and commented on various drafts of the article; and read and approved the final draft.

Funding: Funding for this work was provided in part by a grant from the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy Systematic Review Grant (GA722SRG). The Department of Primary Health care is part of the NIHR School of Primary Care Research. The study sponsors had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; nor in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Competing interests: None.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;339:b2976

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Reference list of included studies

References

- 1.Bisno AL. Acute pharyngitis. N Engl J Med 2001;344:205-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vincent MT, Celestin N, Hussain AN. Pharyngitis. Am Fam Physician 2004;69:1465-70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woodwell DA. National ambulatory medical care survey: 1998 summary. Adv Data 2000;295:1-25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. SIGN guideline 34. Management of sore throat and indications for tonsillectomy. 1999.

- 5.Del MC. Managing sore throat: a literature review. I. Making the diagnosis. Med J Aust 1992;156:572-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linder JA, Stafford RS. Antibiotic treatment of adults with sore throat by community primary care physicians: a national survey, 1989-1999. JAMA 2001;286:1181-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Del Mar CB, Glasziou PP, Spinks AB. Antibiotics for sore throat. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(4):CD000023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. NICE guideline. Respiratory tract infections—antibiotic prescribing. Prescribing of antibiotics for self limiting respiratory tract infections in adults and children in primary care. 2008. [PubMed]

- 9.Standing Medical Advisory Committee S-GoAR. The path of least resistance. London: Department of Health, 1998.

- 10.Little P, Gould C, Williamson I, Warner G, Gantley M, Kinmonth AL. Reattendance and complications in a randomised trial of prescribing strategies for sore throat: the medicalising effect of prescribing antibiotics. BMJ 1997;315:350-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas M, Del MC, Glasziou P. How effective are treatments other than antibiotics for acute sore throat? Br J Gen Pract 2000;50:817-20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Little P, Watson L, Morgan S, Williamson I. Antibiotic prescribing and admissions with major suppurative complications of respiratory tract infections: a data linkage study. Br J Gen Pract 2002;52:187-90, 193. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howie JG, Foggo BA. Antibiotics, sore throats and rheumatic fever. J R Coll Gen Pract 1985;35:223-4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petersen I, Johnson AM, Islam A, Duckworth G, Livermore DM, Hayward AC. Protective effect of antibiotics against serious complications of common respiratory tract infections: retrospective cohort study with the UK General Practice Research Database. BMJ 2007;335:982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mygind N, Nielsen LP, Hoffmann HJ, Shukla A, Blumberga G, Dahl R, et al. Mode of action of intranasal corticosteroids. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001;108(1 suppl):S16-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zalmanovici A, Yaphe J. Steroids for acute sinusitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(2):CD005149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Russell K, Wiebe N, Saenz A, Ausejo SM, Johnson D, Hartling L et al. Glucocorticoids for croup. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(1):CD001955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Candy B, Hotopf M. Steroids for symptom control in infectious mononucleosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;3:CD004402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dickersin K, Manheimer E, Wieland S, Robinson KA, Lefebvre C, McDonald S. Development of the Cochrane Collaboration’s CENTRAL Register of controlled clinical trials. Eval Health Prof 2002;25:38-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahn J, Woo W, Kim Y, Song Y, Jeon I, Jung J, et al. Efficacy of adjuvant short term oral steroid therapy for acute pharyngitis. SO: Korean Journal of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery 2003;46:971-4. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centor RM, Witherspoon JM, Dalton HP, Brody CE, Link K. The diagnosis of strep throat in adults in the emergency room. Med Decis Making 1981;1:239-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marvez-Valls EG, Stuckey A, Ernst AA. A randomized clinical trial of oral versus intramuscular delivery of steroids in acute exudative pharyngitis. Acad Emerg Med 2002;9:9-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Reference list of included studies