Abstract

To optimize the hydrolysis conditions to prepare hydrolysates of jellyfish umbrella collagen with the highest hydroxyl radical scavenging activity, collagen extracted from jellyfish umbrella was hydrolyzed with trypsin, and response surface methodology (RSM) was applied. The optimum conditions obtained from experiments were pH 7.75, temperature (T) 48.77 °C, and enzyme-to-substrate ratio ([E]/[S]) 3.50%. The analysis of variance in RSM showed that pH and [E]/[S] were important factors that significantly affected the process (P<0.05 and P<0.01, respectively). The hydrolysates of jellyfish umbrella collagen were fractionated by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), and three fractions (HF-1>3000 Da, 1000 Da<HF-2<3000 Da, and HF-3<1000 Da) were collected. The HF-2 fraction had the highest hydroxyl radical scavenging activity with the highest yield compared with the other two fractions. Furthermore, HF-2 also showed the strongest Cu2+-chelating ability and the best tyrosinase-inhibitory activity.

Keywords: Jellyfish umbrella collagen, Hydrolysis, Antioxidant activity, Response surface methodology (RSM)

INTRODUCTION

The jellyfish, Rhopilema esculentum, widely distributes in the Bohai Sea, the Yellow Sea, and the South China Sea, and is abundant in the late summer to the early autumn. It is one of the most abundant and important species in Asian jellyfish fishery. Chinese people have used jellyfish as a seafood for more than a thousand years. Jellyfish has high nutritional values and pharmacological activities. It is utilized as a treatment for bronchitis, high blood pressure, tracheitis, asthmas, and gastric ulcers in China (Yu et al., 2006).

Antioxidant activity has recently been reported in peptides from enzymatic hydrolysates of food proteins, such as milk casein (Suetsuna et al., 2000), herring (Sathivel et al., 2003), mackerel (Wu et al., 2003), porcine myofibrillar protein (Saiga et al., 2003), yellow fin sole frame (Jun et al., 2004), soy protein (Moure et al., 2006), wheat protein (Zhu et al., 2006), and yellow stripe trevally (Klompong et al., 2007). However, the process of generating these peptides from original raw material requires optimizing the conditions to obtain antioxidant activity. Levels and compositions of free amino acid and peptides were reported to determine the antioxidant activities of protein hydrolysate (Wu et al., 2003). Collagen is rich in hydrophobic amino acids, and the abundance of these amino acids favors higher affinity to oil and better emulsifying ability (Rajapakse et al., 2005; Lin and Li, 2006). Therefore, collagen is expected to provide natural antioxidant peptides and exert higher antioxidant effects than other proteins.

Jellyfish umbrella is rich in collagenous protein (Nagai et al., 1999) and can be considered as a potential collagen source. However, there are few investigations on the antioxidant effect of collagen hydrolysates from jellyfish umbrella by enzymatic treatment. The objective of this study was to optimize the hydrolysate conditions (pH, temperature (T), and enzyme-to-substrate ratio ([E]/[S])) by response surface methodology (RSM) to have maximal hydroxyl radical scavenging activity from the hydrolysis of jellyfish umbrella collagen. Moreover, the Cu2+-chelating ability and tyrosinase inhibitory activity of hydrolysates were also evaluated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Jellyfish, Rhopilema esculentum, was obtained from Aoshan Bay in Qingdao, China and immediately stored at −20 °C until use. Multifect neutral, gc106, trypsin, and flavorzyme were purchased from Genencor International Co., China. Papain, pepsin, and tyrosinase were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co., USA. Acetonitrile and trifluoroacetic acid were chromatographic grade, and all other reagents used in this study were analytical grade chemicals.

Preparation of collagen from jellyfish umbrella

Collagen was extracted from jellyfish umbrella using the previous method (Nagai et al., 1999) with a slight modification. Jellyfish umbrella was rinsed, cleaned, and treated with 0.1 mol/L NaOH for 2 d. The alkali-extraction was performed to effectively remove non-collagenous proteins. The insoluble fraction was suspended in 0.5 mol/L acetic acid, and then digested with 10% (w/v) pepsin at 4 °C for 2 d. The liquor was centrifuged at 10 000 r/min for 30 min and the supernatant was dialyzed against 0.02 mol/L Na2HPO4 (pH>8.0) for 2 d. The resultant precipitate was obtained by centrifugation at 4000 r/min for 10 min and dissolved in 0.5 mol/L acetic acid, and then against distilled water and lyophilized to get jellyfish umbrella collagen.

Preparation of enzymatic hydrolysates of jellyfish collagen

50 mg collagen was dissolved with 100 ml phosphate-buffered saline (0.02 mol/L, pH 7.5) and the hydrolyzing process was adjusted to optimum of the respective enzyme used (Table 1) and the hydrolysis was stopped after heating the samples above 90 °C for 5 min, and then the hydrolysates were cooled by cold flowing water and centrifuged at 4000 r/min for 15 min. The supernatants were collected and their volumes were measured. Hydrolysate nitrogen contained all nitrogens derived from proteins, peptides, and free amino acids. Protein content was measured according to the Kjeldahl procedure and multiplying the nitrogen value by 5.79.

Table 1.

Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity of collagen hydrolysate using six commercial food grade proteases

| Proteases | Optimal hydrolysis conditions | Scavenging OH· activity (%) |

| Blank | – | 4.3±0.1 |

| Multifect neutral | pH 7, 45 °C | 45.0±0.7 |

| Papain | pH 6, 37 °C | 60.2±1.7 |

| Pepsin | pH 2, 37 °C | 27.2±0.9 |

| Flavorzyme | pH 7.2, 50 °C | 47.5±1.1 |

| Trypsin | pH 8, 45 °C | 69.5±0.9 |

| Gc106 | pH 4.5, 45 °C | 25.1±0.4 |

The conditions (0.5 mg/ml of substrate concentration, 3% of [E]/[S], and 3 h of hydrolysis time) were the same for all enzymes. Every experiment was carried out in triplicate

Optimization of hydrolysis of collagen

The RSM (Box et al., 1978) was applied to investigate optimum conditions of three variables pH, T, and [E]/[S] on the hydroxyl radical scavenging activity of the hydrolysates prepared using trypsin (Table 2). A three-level-three-factor Box-Behnken design was employed and a set of 15 experiments was carried out as shown in Table 2. According to the labeled suitable enzymatic hydrolysis conditions of trypsin, the three levels of three variables were: pH (7.5, 8.0, and 8.5), T (35, 45, and 55 °C), and [E]/[S] (1.5%, 3.0%, and 4.5%), respectively. The experimental design is shown in Table 2. The experimental results were fitted with the following equation:

| Y=β0+β1X1+β2X2+β3X3+β11X12+β12X1X2+β13X1X3+ β22X22+β23X2X3+β33X32. |

Table 2.

Experimental design and responses of the dependent variables to the hydrolysis conditions

| Design point | T (°C), X1 | [E]/[S] (%), X2 | pH, X3 | Scavenging OH· activity (%) |

| 1 | 35 | 1.5 | 8.0 | 54.9 |

| 2 | 35 | 4.5 | 8.0 | 63.9 |

| 3 | 55 | 1.5 | 8.0 | 55.8 |

| 4 | 55 | 4.5 | 8.0 | 63.3 |

| 5 | 45 | 1.5 | 7.5 | 56.5 |

| 6 | 45 | 1.5 | 8.5 | 53.9 |

| 7 | 45 | 4.5 | 7.5 | 68.4 |

| 8 | 45 | 4.5 | 8.5 | 54.6 |

| 9 | 35 | 3.0 | 7.5 | 57.3 |

| 10 | 55 | 3.0 | 7.5 | 69.1 |

| 11 | 35 | 3.0 | 8.5 | 61.6 |

| 12 | 55 | 3.0 | 8.5 | 59.7 |

| 13 | 45 | 3.0 | 8.0 | 70.2 |

| 14 | 45 | 3.0 | 8.0 | 70.9 |

| 15 | 45 | 3.0 | 8.0 | 70.8 |

Molecular weight (M W) distribution

The molecular weight distribution of hydrolysates obtained under the optimal conditions was measured by gel permeation chromatography (Tamaru et al., 2007) using a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (Agilent 1100, USA). A TSK gel 3000 PWXL column (30 mm i.d.×7.8 mm, Tosoh, Tokyo, Japan) was equilibrated with acetonitrile-water (1:1, v/v) in the presence of 0.1% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid. The flow rate was 0.6 ml/min and the hydrolysates were monitored at 220 nm at 30 °C. A calibration curve of molecular weight was prepared according to the following standards: cytochrome C (12 500 Da), insulin (5734 Da), vitamin B12 (1355 Da), hippuryl-histydilleucine (429.5 Da), and glutathione (309.5 Da) (Sigma Co., St. Louis, MO, USA). The logarithm of molecular weight (M W) tested and the respective retention time (t R) were a linear relationship (R 2=0.9945, P<0.01) and the molecular weight of hydrolysates could be calculated according to the following formula: lgM W=−0.2721t R+7.7887.

Amino acid composition

Samples were hydrolyzed under reduced pressure with 6 mol/L HCl at 110 °C for 24 h and hydrolysates were analyzed on a Hitachi amino acid analyzer 835-50 (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity assay

Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity was assessed using an ascorbic acid-Cu2+-hydrogen superoxide-yeast suspension system (Zhao et al., 2004) with a slight modification. 0.2 ml of freshly prepared ascorbic acid solution (2 mmol/L), 0.4 ml CuSO4 (2 mmol/L), 50 μl luminal (1 mmol/L, in 0.1 mol/L NaCO3), 0.2 ml yeast suspension (7.5 g/100 ml), and 0.6 ml collagen hydrolysates were injected into the reaction tube and kept in a water bath at 37 °C for 30 min, and 0.6 ml H2O2 solution (6.8 mmol/L) was then added to start the reaction. Luminol chemiluminescence of the system was measured using an ultraweak luminescence analyzer (BPCL, Beijing, China). Phosphate-buffered saline (50 mmol/L, pH 7.8) was used as control. The percentage inhibition was calculated according to the following equation:

| %inhibition=(C0−C1)/C0×100%, |

where C 1 was the sample chemiluminescence and C 0 was the blank chemiluminescence.

Cu2+-chelating ability assay

Cu2+-chelating ability was determined using the dual-wavelength spectrophotometric tetramethylmurexide (TMM) method described by Wijewickreme and Kitts (1997) with some modifications. The reaction mixture contained 0.5 ml of hydrolysates of jellyfish collagen fractions, 1.5 ml of hexamine buffer (10 mmol/L, pH 6.8) containing 10 mmol/L KCl, and 0.5 ml of CuSO4 (2 mmol/L) in a tube, and was incubated for 30 min at room temperature. After incubation, the reaction mixture was treated with 0.1 ml of TMM (1 mmol/L) in hexamine buffer. The amount of free copper in the solutions was determined by the absorbance ratio A 460/A 530. The amount of Cu2+ chelated was calculated as the difference between total copper added and free copper present in the solutions.

Tyrosinase inhibitory activity assay

Tyrosinase inhibitory activity was measured using pervious method with a slight modification (Kim et al., 2005). 120 μl of hydrolysates of jellyfish collagen in phosphate buffer (20 mmol/L, pH 7.2), 20 μl of freshly prepared mushroom tyrosinase (0.33 U/ml, Sigma Co., St. Louis, MO, USA), and 60 μl of L-dopa (0.1 mol/L) were mixed in a reaction tube. The absorbance was read every 5 min for 30 min at 37 °C and the absorbance of each well was read at 475 nm using a BioRad model 3550 microplate reader (BioRad, GMI Inc., USA). The final activity was expressed in the change of optical density (ΔOD) per min for each condition. The percentage of tyrosinase inhibitory activity of collagen hydrolysate was calculated according to the following equation:

| %inhibition=(1−ΔOD1/ΔOD0)×100%, |

where ΔOD 1 was the absorbance of the sample, and ΔOD 0 was the absorbance of the control.

Statistical analysis

Statistical evaluations were carried out in the statistical analysis system (SAS) windows version 6.21 (SAS Institute Inc., USA). Least significant difference (LSD) test was used to make comparisons among mean values. Means were accepted as significantly different at 95% confidence interval (P<0.05).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Screening of proteases on production of collagen hydrolysates

Six commercial food grade proteases were selected to digest the jellyfish collagen, and each hydrolysis was carried out under the optimum of the respective enzyme (Table 1). As shown in Table 1, collagen hydrolysates showed much higher hydroxyl radical scavenging activity than collagen. Meanwhile, among the hydrolytic groups, significant differences in hydroxyl radical scavenging activity were observed and the highest hydroxyl radical scavenging activity (69.5%) was observed in trypsin hydrolytic group. It indicates that hydrolysate obtained from trypsin-hydrolyzing collagen might exhibit the better antioxidant activity. Therefore, trypsin was chosen to be used in subsequent experiments.

Optimization of enzymatic hydrolysis by RSM

RSM was drawn to illustrate the influence of different hydrolysis factors such as pH, T, and [E]/[S] on hydroxyl radical scavenging activity of the hydrolysate of jellyfish collagen using trypsin. The experimental designs and results are shown in Table 2. The analysis of variance (Table 3) showed that the Prob>F value of the hydroxyl radical scavenging activity was 0.0094, which demonstrates that the model itself was significant at a 99% confidence level. The degree of fitness of the model could be also checked by the coefficient (R 2) of determination. The R 2 value of radical scavenging activity was 94.95%, indicating that the statistical models could represent the actual relationships between the parameters chosen.

Table 3.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) for hydroxyl radical scavenging activity in quadratic model

| Source | df | Sum of squares | Mean of squared | F-value | Prob>F | R2 |

| Linear | 3 | 176.64 | 58.88 | 9.92 | 0.0151 | |

| Quadratic | 3 | 302.36 | 100.79 | 16.99 | 0.0047 | |

| Cross product | 3 | 78.85 | 26.28 | 4.43 | 0.0714 | |

| Model | 9 | 557.84 | 61.98 | 10.44 | 0.0094 | 0.9495 |

As shown in Table 4, [E]/[S] exerted the highest significant effect within a 99% confidence interval (P<0.01) among the three independent variables, followed by pH within a 95% confidence interval (P<0.05). The effect of reaction temperature had no significant influence (P>0.05). Moreover, the quadratic terms of ([E]/[S])2, T 2, and pH2, as well as the interaction term of T×pH, were also significant (P<0.05), whereas the effects of T×([E]/[S]) and ([E]/[S])×pH were not significant (P>0.05). These results are consistent with other researches. Guerard et al.(2007) reported that pH showed the significant effect on antiradical activity in the hydrolysis of shrimp. Ren et al.(2008) found that [E]/[S] exerted the significant effect on antioxidant activity of the hydrolysate derived from grass carp sarcoplasmic protein.

Table 4.

Analysis of variance for the response of hydroxyl radical scavenging activity in the hydrolysate

| Source | Scavenging OH· activity |

|

| F-ratio | P-value | |

| T | 2.19 | 0.1988 |

| [E]/[S] | 17.84 | 0.0083** |

| pH | 9.74 | 0.0262* |

| T2 | 8.95 | 0.0304* |

| T×([E]/[S]) | 0.09 | 0.7706 |

| T×pH | 7.91 | 0.0375* |

| ([E]/[S])2 | 33.77 | 0.0021** |

| ([E]/[S])×pH | 5.28 | 0.0699 |

| pH2 | 15.04 | 0.0117* |

Significant at 5% level

Significant at 1% level

According to the model regression analysis, the best explanatory model equation was given as follows:

| %inhibition=70.63+3.64([E]/[S])−2.69pH−3.79T2−3.425T×pH+7.37([E]]/[S])2−4.92pH2. |

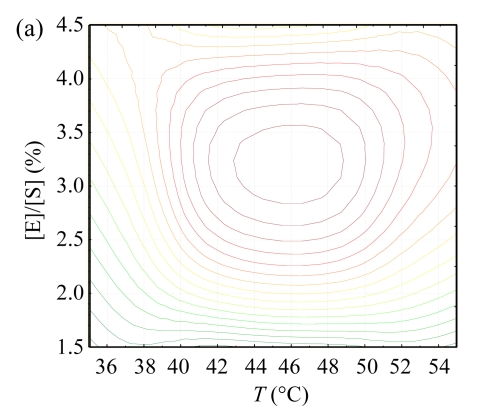

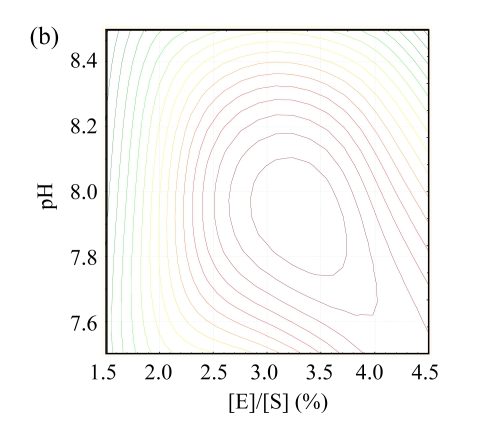

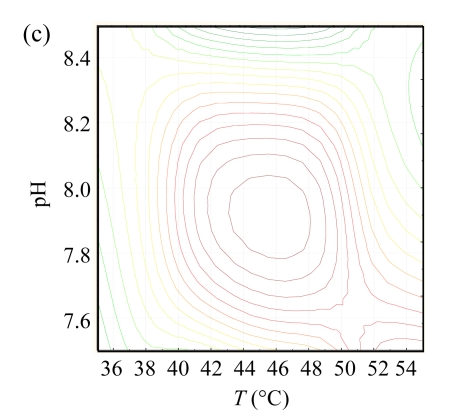

The contour plots for hydroxyl radical scavenging activity are shown in Fig.1. These plots display the responses to two independent variables and locate the point of maximum activity (Wu et al., 2008). There was an ellipse in each contour plot, indicating that the maximum point was exactly within the experimental range. The optimum conditions of different independent variables were analyzed by using ‘Numerical Optimization’ of the Design-Expert16 software. The results indicate that the optimal conditions were pH of 7.75, T of 48.77 °C, and the [E]/[S] of 3.50%, and that the highest hydroxyl radical scavenging activity was predicted to be 72.15%. To confirm the accuracy of the model, hydrolysis experiment under the deduced optimum was conducted, and the hydroxyl radical scavenging activity under the optimal hydrolysis conditions was found to be 72.04%, indicating that the response model was adequate to predict the reaction optimization.

Fig.1.

The contour plots for hydroxyl radical scavenging activity as functions of (a) [E]/[S] vs T at the pH of 8.0, (b) pH vs [E]/[S] at T of 45 °C, and (c) pH vs T at the [E]/[S] of 3%

Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity of jellyfish collagen hydrolysates

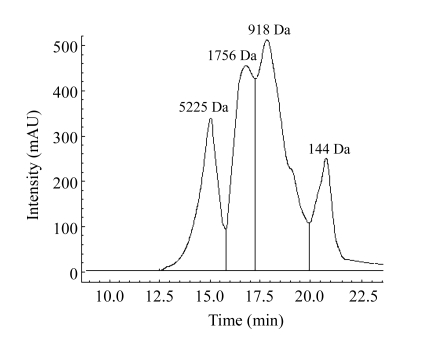

The molecular weight distribution of jellyfish collagen hydrolysates obtained with trypsin is shown in Fig.2. The molecular mass of the hydrolysates was lower than 8000 Da. The collagen hydrolysates were fractionated and collected by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), noting HF-1 (>3000 Da), HF-2 (1000~3000 Da), and HF-3 (<1000 Da). Based on the peak area, HF-1, HF-2, and HF-3 accounted for 20.3%, 47.2%, and 32.5%, respectively. For the fragmented hydrolysates, the fraction HF-2 had higher yield and hydroxyl radical scavenging activity (Table 5). Scavenging effect of HF-2 was 87.4% at a dose of 0.5 mg/ml, while those of HF-1 and HF-3 were 51.2% and 76.7%, respectively.

Fig.2.

Chromatogram of collagen hydrolysate by gel permeation chromatography

Table 5.

Antioxidant activity and tyrosinase inhibition effects of three fractions

| Fractions | Scavenging OH· activity (%)a | Cu2+-chelating activity (%)b | Tyrosinase inhibition (%)c |

| HF-1 | 51.2±1.2 | 31.7±0.7 | 21.7±1.2 |

| HF-2 | 87.4±1.7 | 56.5±1.2 | 53.9±2.1 |

| HF-3 | 76.7±0.8 | 49.3±0.8 | 47.2±2.5 |

Values expressed as mean±SD

Antioxidant activities were tested at 0.5 mg/ml

Antioxidant activities were tested at 0.5 mg/ml

Tyrosinase inhibition was tested at 5.0 mg/ml

Generally, there is no direct relationship between antioxidant activity and molecular weight (Kong and Xiong, 2006). However, many studies have shown that the antioxidant activity of protein hydrolysate is related to its molecular weight distribution; e.g., the low molecular weight peptide fraction (<3000 Da) from the jumbo squid skin gelatin hydrolysate showed the highest antioxidant activity (Mendis et al., 2005), and Li et al.(2008) obtained antioxidant hydrolysates with a molecular weight 200~3000 Da from chickpea protein. However, some researches showed that excessive hydrolysis reduced the antioxidant ability of hydrolysates. Wu et al.(2003) reported that the antioxidant activity of protein hydrolysate reached the highest value when hydrolyzed for 10 h, and a peptide with 1400 Da from mackerel protein hydrolysates showed higher antioxidant activity than 900- or 200-Da peptide.

Moreover, compositions of amino acids play an important role in antioxidant activities of protein hydrolysate. High content of hydrophobic amino acids could increase the solubility of collagen peptides in lipid and then enhance their antioxidant activities (Kim et al., 2001). Rajapakse et al.(2005) found that fish skin gelatin peptides possessed higher antioxidant activity than peptides derived from other fish proteins because of the high percentage of Gly and Pro. Chen et al.(1995) reported that His and Pro played important roles in the antioxidant activity of synthetic peptides. The amino acid compositions of three fractions showed that they were rich in Gly, Glu, Pro, Asp, Val, and Arg (Table 6). Therefore, the antioxidant activities of collagen hydrolysates were inherent to their characteristic amino acid sequences.

Table 6.

Amino acid composition of three fractions separated by HPLC (g/100 g)

| Amino acid | Amino acid content (g/100 g) |

||

| HF-1 | HF-2 | HF-3 | |

| Asp | 8.06 | 8.86 | 8.51 |

| Thr | 3.65 | 2.88 | 2.47 |

| Ser | 4.39 | 4.62 | 6.40 |

| Glu | 10.52 | 10.01 | 9.47 |

| Pro | 11.92 | 12.80 | 16.01 |

| Gly | 26.17 | 25.26 | 19.39 |

| Ala | 8.02 | 7.71 | 7.02 |

| Val | 4.22 | 4.66 | 4.51 |

| Met | 1.26 | 1.36 | 1.55 |

| Ile | 2.21 | 2.30 | 3.27 |

| Leu | 2.92 | 3.28 | 4.70 |

| Tyr | 0.91 | 1.07 | 3.00 |

| Phe | 1.36 | 1.64 | 3.33 |

| Lys | 2.73 | 3.33 | 3.60 |

| His | 0.35 | 0.44 | 0.52 |

| Arg | 5.44 | 7.72 | 5.93 |

| Hyp | 5.87 | 2.06 | 0.32 |

| Total | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

Cu2+-chelating ability of hydrolysates

The Cu2+-chelating activity of three fractions of jellyfish collagen hydrolysates was investigated. The results indicate that HF-2 had the highest Cu2+-chelating activity, 56.5% at 0.5 mg/ml at the molecular weight of 1000~3000 Da (Table 5).

Hydroxyl radical can be formed from superoxide anion and hydrogen peroxide in the presence of transition metal ions, such as Fe2+ and Cu2+. Chelating metal ions may inhibit the formation of the hydroxyl radical (Zhou et al., 2008). Megías et al.(2007) reported that molecular weights of peptides played a key role in chelating metals. If the length of peptides is too short, chelation is unstable; otherwise, the utilization of peptides is depressible. Klompong et al.(2007) and Dong et al.(2008) reported that the metal-chelating ability and molecular weight had a linear relation, and that metal-chelating ability increased with the decrease of molecular weight. Wu et al.(2008) indicated that the metal-chelating ability of sericin hydrolysate was high among the range of 8.0%~15.0% for the degree of hydrolysis (DH); however, when DH was lower than 8.0% or higher than 15.0%, the metal-chelating ability was decreased obviously.

Tyrosinase inhibitory activity of hydrolysates

The tyrosinase inhibition of collagen hydrolysates was also investigated. The results show that the inhibitory effect of HF-2 was higher than 50% at 5 mg/ml (Table 5), indicating the high antioxidant activity and strong Cu2+ -chelating activity. Tyrosinase, a copper-containing mixed-function oxidase, is widely distributed in micro-organisms, plants, and animals, and it is a key enzyme in melanin biosynthesis. Additionally, enzymatic browning in fruits and vegetables is related to the tyrosinase in plant tissues, so tyrosinase inhibitors have recently attracted more and more attention (Xie et al., 2003). Concerning the action mechanism of inhibitors, blocking oxidative pathway (Curto et al., 1999) and bonding the enzyme activity sites (Kim, 2007) may be mainly involved to inhibit the activity of tyrosinase. Some researches showed that proteins and peptides from natural resources such as honey, wheat, milk, silk, and housefly are able to inhibit tyrosinase activity because of their Cu2+-chelating ability (Schurink et al., 2007). Our results suggest that HF-2 could inhibit tyrosinase activity via the high antioxidant activity and Cu2+-chelating ability. Therefore, HF-2 from jellyfish umbrella collagen hydrolysate might be a natural and novel tyrosinase inhibitor in medicine and food industries.

CONCLUSION

In order to utilize jellyfish to produce bioactive peptides, jellyfish umbrella collagen was hydrolyzed by trypsin. By relating RSM with hydroxyl radical scavenging activity, the optimal hydrolysis conditions (pH of 7.75, T of 48.77 °C, and [E]/[S] of 3.50%) were obtained, in which the highest hydroxyl radical scavenging activity (72.04%) was achieved. The jellyfish umbrella collagen hydrolysate was fractionated by HPLC. The fraction HF-2 (1000~3000 Da) had the highest radical scavenging activity with the highest yield. Meanwhile, the fraction HF-2 showed the strongest Cu2+-chelating ability and the best tyrosinase inhibitory activity. The results of this study show that the hydrolysate of jellyfish umbrella collagen may be used as functional ingredient in the medicine and food industries. Jellyfish is rich in collagen and can be utilized for economical benefits and human health.

Footnotes

Project (No. 2008BAD94B07) supported by the Hi-Tech Research and Development Program (863) of China

References

- 1.Box G, Hunter WG, Hunter JS. Statistics for Experimenters. New York: John Wiley and Sons Inc; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen HM, Muramoto K, Yamauchi F. Structural analysis of antioxidative peptides from soybean-conglycinin. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 1995;43(3):574–578. doi: 10.1021/jf00051a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curto EV, Kwong C, Hermersdörfer H, Glatt H, Santis C, Virador V. Inhibitors of mammalian melanocyte tyrosinase: in vitro comparisons of alkyl esters of gentisic acid with other putative inhibitors. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1999;57(6):663–672. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(98)00340-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dong SY, Zeng MY, Wang DF, Liu ZY, Zhao YH, Yang HC. Antioxidant and biochemical properties of protein hydrolysates prepared from Silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) Food Chemistry. 2008;107(4):1485–1493. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.10.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guerard F, Sumaya-Martinez MT, Laroque D, Chabeaud A, Dufosse L. Optimization of free radical scavenging activity by response surface methodology in the hydrolysis of shrimp processing discards. Process Biochemistry. 2007;42(11):1486–1491. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2007.07.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jun SY, Park PJ, Jung WK, Kim SK. Purification and characterization of an antioxidative peptide from enzymatic hydrolysate of yellow fin sole (Limanda aspera) frame protein. European Food Research and Technology. 2004;219(1):20–26. doi: 10.1007/s00217-004-0882-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim SK, Kim YT, Byun HG, Nam KS, Joo DS, Shahidi F. Isolation and characterization of antioxidative peptides from gelatin hydrolysate of Alaska pollack skin. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2001;49(4):1984–1989. doi: 10.1021/jf000494j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim YJ. Anti-melanogenic and antioxidant properties of gallic acid. Biological & Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2007;30(6):1052–1055. doi: 10.1248/bpb.30.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim YJ, No JK, Lee JH, Chung HY. 4,4′-Dihydroxybiphenyl as a new potent tyrosinase inhibitor. Biological & Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2005;28(2):323–327. doi: 10.1248/bpb.28.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klompong V, Benjakul S, Kantachote D, Shahidi F. Antioxidative activity and functional properties of protein hydrolysate of yellow stripe trevally (Selaroides leptolepis) as influenced by the degree of hydrolysis and enzyme type. Food Chemistry. 2007;102(4):1317–1327. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.07.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kong BH, Xiong YL. Antioxidant activity of zein hydrolysates in a liposome system and the possible mode of action. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2006;54(16):6059–6068. doi: 10.1021/jf060632q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li YH, Jiang B, Zhang T, Mu WM, Liu J. Antioxidant and free radical-scavenging activities of chickpea protein hydrolysate. Food Chemistry. 2008;106(2):444–450. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.04.067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin L, Li BF. Radical scavenging properties of protein hydrolysates from Jumbo flying squid (Dosidicus eschrichitii steenstrup) skin gelatin. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2006;86(14):2290–2295. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2600. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Megías C, Pedroche J, Yust MM, Girón-Calle J, Alaiz M, Millán F, Vioque J. Affinity purification of copper chelating peptides from Chickpea protein hydrolysates. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2007;55(10):3949–3954. doi: 10.1021/jf063401s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mendis E, Rajapakse N, Byun HG, Kim SK. Investigation of jumbo squid (Dosidicus gigas) skin gelatin peptides for their in vitro antioxidant effects. Life Sciences. 2005;77(17):2166–2178. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moure A, Dominguez H, Parajo JC. Antioxidant properties of ultrafiltration recovered soy protein fractions from industrial effluents and their hydrolysates. Process Biochemistry. 2006;41(2):447–456. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2005.07.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagai T, Ogawa T, Nakemura T, Ito T, Nakagawa H, Fujiki K, Nakao M, Yano T. Collagen of edible jellyfish exumbrella. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 1999;79(6):855–858. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0010(19990501)79:6<855::AID-JSFA299>3.3.CO;2-E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rajapakse N, Mendis E, Byun HG, Kim SK. Purification and in vitro antioxidative effects of giant squid muscle peptides on free radical-mediated oxidative systems. Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 2005;16(9):562–569. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ren JY, Zhao MM, Shi J, Wang JS, JIang YM, Cui C, Kakuda Y, Xue SJ. Optimization of antioxidant peptide production from grass carp sarcoplasmic protein using response surface methodology. Food Science and Technology. 2008;41(9):1624–1632. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2007.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saiga A, Tanabe S, Nishimura T. Antioxidant activity of peptides obtained from porcine myofibrillar proteins by protease treatment. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2003;51(12):3661–3667. doi: 10.1021/jf021156g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sathivel S, Bechtel PJ, Babbitt J, Smiley S, Crapo C, Reppond KD. Biochemical and functional properties of herring (Clupea harengus) byproduct hydrolysates. Journal of Food Science. 2003;68(7):2196–2200. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2003.tb05746.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schurink M, Willem JH, Wichers HJ, Boeriu CG. Novel peptides with tyrosinase inhibitory activity. Peptides. 2007;28(3):485–495. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suetsuna K, Ukeda H, Ochi H. Isolation and characterization of free radical scavenging activities peptides derived from casein. The journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 2000;11(3):128–131. doi: 10.1016/S0955-2863(99)00083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tamaru S, Kurayama T, Sakono M, Fukuda N, Nakamori T, Furuta H, Tanaka K, Sugano M. Effects of dietary soybean peptides on hepatic production of ketone bodies and secretion of triglyceride by perfused rat liver. Bioscience, Biotechnology, Biochemistry. 2007;71(10):2451–2457. doi: 10.1271/bbb.70221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wijewickreme AN, Kitts DD. Influence of reaction conditions on the oxidative behavior of model Maillard reaction products. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 1997;45(12):4571–4576. doi: 10.1021/jf970040v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu HC, Chen HM, Shiau CY. Free amino acids and peptides as related to antioxidant properties in protein hydrolysates of mackerel (Scomber austriasicus) Food Research International. 2003;36(9-10):949–957. doi: 10.1016/S0963-9969(03)00104-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu JH, Wang Z, Xu SY. Enzymatic production of bioactive peptides from sericin recovered from silk industry wastewater. Process Biochemistry. 2008;43(5):480–487. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2007.11.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xie LP, Chen QX, Huang H, Liu XD, Chen HT, Zhang RQ. Inhibitory effects of cupferron on the monophenolase and diphenolase activity of mushroom tyrosinase. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 2003;35(12):1658–1666. doi: 10.1016/S1357-2725(03)00006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu HH, Liu XG, Xing RE, Liu S, Guo ZY, Wang PB, Li PC. In vitro determination of antioxidant activity of proteins from jellyfish Rhopilema esculentum . Food Chemistry. 2006;95(1):123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.12.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao X, Xue CH, Li ZJ, Cai YP, Liu HY, Qi HT. Antioxidant and hepato protective activities of low molecular weight sulfated polysaccharide from Laminaria japonica . Journal of Applied Physics. 2004;16(2):111–115. doi: 10.1023/B:JAPH.0000044822.10744.59. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou J, Hu N, Wu Y L, Pan YJ, Sun CR. Preliminary studies on the chemical characterization and antioxidant properties of acidic polysaccharides from Sargassum fusiforme . Journal of Zhejiang University SCIENCE B. 2008;9(9):721–727. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B0820025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu KX, Zhou HM, Qian HF. Antioxidant and free radical scavenging activities of wheat germ protein hydrolysates (WGPH) prepared with alcalase. Process Biochemistry. 2006;41(6):1296–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2005.12.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]