Abstract

Zearalenone, a fungal macrocyclic polyketide, is a member of the resorcylic acid lactone family. Herein, we characterize in vitro the thioesterase from PKS13 in zearalenone biosynthesis (Zea TE). The excised Zea TE catalyzes macrocyclization of a linear thioester activated model of zearalenone. Zea TE also catalyzes the cross coupling of a benzoyl thioester with alcohols and amines. Kinetic characterization of the cross coupling is consistent with a ping-pong bi-bi mechanism, confirming an acyl-enzyme intermediate. Finally, the substrate specificity of the Zea TE indicates the TE may help control iterative cycling on PKS13 by rapidly off loading the final resorcylate containing product.

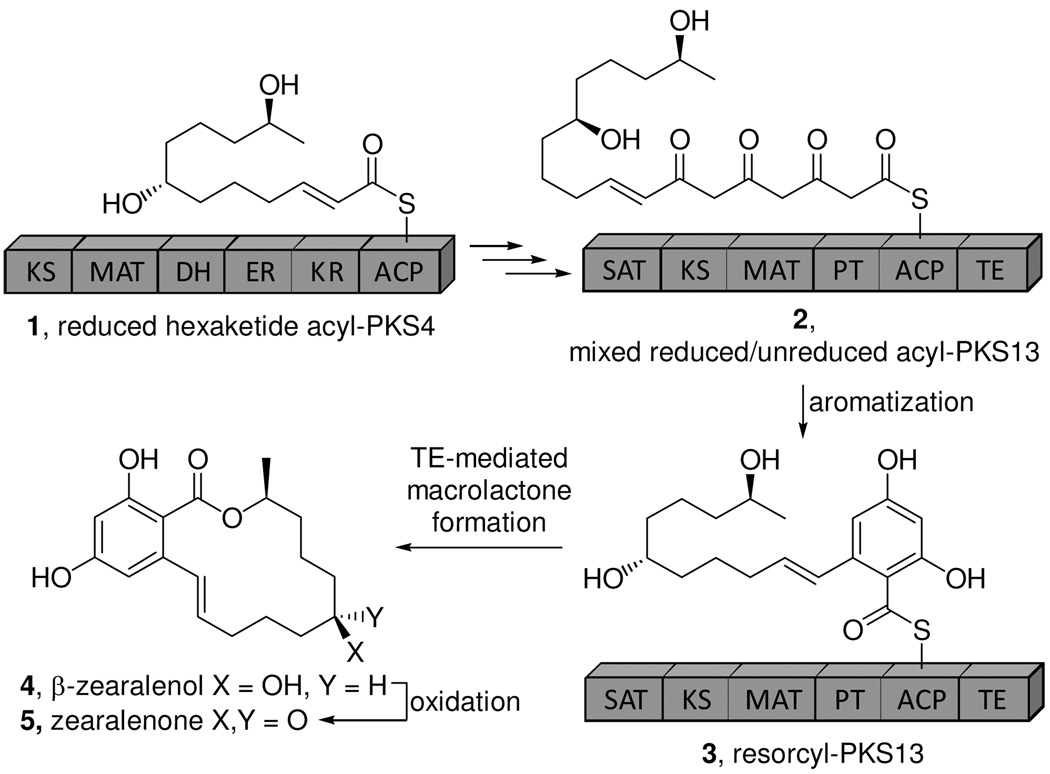

Resorcylic acid lactones (RALs)1 are a large family of polyketide macrolactones with diverse biological activity (1). They include the estrogen receptor agonist zearalenone 5 and the HSP90 inhibitor, radicicol (2, 3). The carbon framework of 5 is generated in the fungus Gibberella zeae by the actions of two iterative polyketide synthases (PKS) (Figure 1). PKS4 produces a highly reduced hexaketide intermediate 1, which is transferred to the megasynthase PKS13. PKS13 functions iteratively, adding three unreduced ketide units to generate 2, and, subsequently, catalyzes aromatization to produce 3 (4, 5). The thioesterase (TE) domain of PKS13 is then postulated to generate the macrolactone 4, releasing the macrocycle. FAD-dependent oxidation then gives 5 (4). In this study, we show that the TE of PKS13 (Zea TE) is responsible for macrocyclization of 3 and can catalyze rapid cross-coupling to generate esters and amides. Characterization of the in vitro substrate specificity of the Zea TE suggests that the TE acts as a gatekeeper in vivo, ensuring cleavage of the growing polyketide from the synthase only after aromatization of the unreduced intermediate 2. This model represents a new mechanism for controlling iterative processing in polyketide biosynthesis.

Figure 1.

The biosynthesis of zearalenone, an archetypical RAL.

The fungal Zea TE is unique in both primary sequence and function. Alignment (SI) shows it to be substantially different (≤ 20% identity) from the well-characterized macrocyclizing bacterial PKS TEs (6–10) and the fungal TEs responsible for Claisen-like condensation activity (11, 12). The proposed macrocylization catalyzed by Zea TE has been shown to be chemically challenging under Corey-Nicolaou and Yamaguchi conditions (13). Furthermore, in vivo data suggests the Zea TE may be able to catalyze highly useful cross-coupling with alcohol nucleophiles (5).

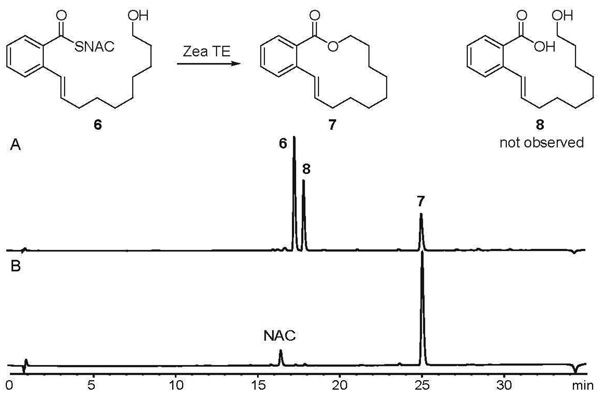

To demonstrate unambiguously that the Zea TE is responsible for macrocyclization of 4, we synthesized a model macrocyclization precursor and evaluated the ability of the excised Zea TE to catalyze macrocyclization. N-acetyl cysteamine (NAC) thioester 6 and the macrocyclic product 7 were synthesized following a short sequence (SI). Excised Zea TE was expressed in E. coli and purified to homogeneity by affinity chromatography (SI). Incubation of Zea TE with 6 led exclusively and rapidly to the formation of 7 as determined by HPLC (Figure 2) and 1H NMR analysis (SI). To kinetically characterize Zea TE activity, release of NAC was monitored using Ellman's reagent and quantified spectrophotometrically. Kinetic analysis indicates that the TE catalyzes macrocyclization of 6 with a specificity constant of kcat/KM = 2.92 ± 0.16 × 103 M−1s−1. Due to the limited solubility of 6, kcat and KM could not be independently determined. This specificity constant is ten to one hundred-fold greater than those reported for macrocyclization by the TE from the pikromicin biosynthetic pathway (14, 15) and one-thousand fold greater than those seen for the TEs from epothilone (Epo TE) and 6-deoxyerythronolide biosynthesis (10, 15). Unlike Epo TE (10) and TEs from non-ribosomal peptide synthetase pathways (16), the Zea TE does not catalyze detectable levels of hydrolysis to the linear carboxylic acid, making it an excellent potential tool for synthetic transformations involving macrolide macrocyclizations.

Figure 2.

Zea TE catalyzes macrocyclization of 14-member rings. A: HPLC analysis of authentic standards. B: HPLC analysis of a 30 min incubation of 15 µM Zea TE with 5 mM 6 in 50 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7.4, 23 °C. Negative controls lacking Zea TE showed no detectable macrocyclization activity.

To confirm that the observed macrocyclization reaction is catalytic, the putative active site nucleophile S163 and the putative catalytic base H332 were mutated and the mutants were kinetically characterized. The S163A and H332A mutants were generated by site-directed mutagenesis, expressed and purified to homogeneity by affinity chromatography (SI). Both the S163A and H332A mutants showed no detectable catalytic activity, indicating S163 and H332 play key roles in catalysis.

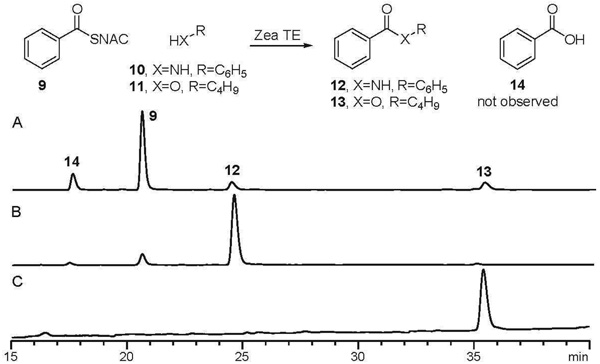

In vivo characterization of PKS13 had shown that ethanol and butanol could be coupled to acyl chains, produced by PKS13 to generate esters (5). To determine if Zea TE was responsible for this cross-coupling activity, we investigated the consumption of 9 by Zea TE in the presence of exogenous nucleophiles. The Zea TE was incubated with 9 and varying concentrations of butanol. LCMS analysis of the reaction mixtures showed conversion exclusively to butyl benzoate without formation of benzoic acid even when stoichiometric butanol was present. Kinetic analysis performed at varying butanol concentrations showed Michaelis-Menten behavior and parallel Lineweaver-Burk plots were obtained (SI). These results are consistent with a ping-pong bi-bi mechanism, fully supporting the postulated acyl-enzyme intermediate in the reaction mechanism.

A number of additional alcohol and amine based nucleophiles cross-coupled with 9 to generate the corresponding benzoates and benzamides (Table 1 and Figure 3). Primary and secondary alcohols cross coupled with 9, as did allyl amine and aniline. Tertiary alcohol (t-butanol) and amino acids (glycine and methyl glycinate) were not cross-coupled to 9. In the absence of any exogenous nucleophile, the Zea TE used water to effect hydrolysis of 9, generating benzoic acid. In general, α/β hydrolases such as esterases, lipases, and proteases catalyze cross-coupling (transesterification) without hydrolysis when the exogenous nucleophile is provided in high concentration or water is excluded from the solvent system (17). The ability of the Zea TE to catalyze cross-coupling in aqueous buffer with low concentration exogenous nucleophile is thus particularly advantageous and complementary to existing α/β hydrolases. Characterized aroyltransferases, which can catalyze cross coupling in aqueous buffer, require CoA thioesters as substrates (18–20), limiting their utility for in vitro chemistry. The use of the easy to prepare NAC thioesters by the Zea TE makes this an attractive enzyme for chemoenzymatic synthesis of commodity and fine chemicals.

Table 1.

Relative velocities for Zea TE mediated cross coupling with exogenous nucleophilesa

| nucleophile | νrel |

|---|---|

| butanol | 1.00 |

| benzyl alcohol | 0.84 |

| aniline | 0.58 |

| ethanol | 0.50 |

| isopropanol | 0.38 |

| allylamine | 0.38 |

| glycerol | 0.34 |

| water | 0.20 |

0.1 µM Zea TE with 1 mM 9, 6 mM nucleophile (except for water at 55 M) at pH 7.4, 23 °C. Negative controls lacking Zea TE showed no reactivity.

Figure 3.

HPLC analysis of Zea TE catalyzed cross-coupling reactions. A: Products and standards. B: Cross-coupling reaction with aniline. C: Cross-coupling reaction with butanol. Enzymatic reactions were incubated 3h with 5 µM Zea TE, 10 mM 9, 20 mM analine or butanol in 50 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7.4, 23 °C. Negative controls lacking Zea TE showed no detectable cross coupling products.

Kinetic characterization of Zea TE with thioester substrates that model the intermediates in 2 and 3 (Figure 1), shows the enzyme to be highly specific for aromatic thioesters. 9, a model of the resorcylate intermediate 3, was consumed very rapidly in the presence of 6 mM butanol, with an apparent specificity constant of kcat/KM = 12.2 ± 1.6 × 103 M−1s−1 (kcat = 9.8 ± 0.6 s−1, KM = 0.80 ± 0.09 mM). In the absence of butanol (and any other exogenous nucleophile, such as glycerol), Zea TE catalyzed the hydrolysis of 9 to benzoic acid with a comparable specificity constant, kcat/KM = 16.0 ± 1.7 × 103 M−1s−1 (kcat = 1.18 ± 0.03 s−1, KM = 78 ± 8 µM). This specificity constant is approximately ten thousand times of that seen for thioester hydrolysis by bacterial PKS TEs (6, 7, 21–24). The NAC thioester of 3-ketopentanoate was originally selected as a representative model of intermediate 2. However, the rapid rate of background hydrolysis precluded accurate kinetic characterization of the enzymatic reaction from this substrate. The NAC thioester of α-methyl-β-ketopentanoate, was thus used as a surrogate of the poly-β-keto intermediate 2. The pentanoate underwent hydrolysis to generate the corresponding carboxylic acid with a one hundred fold lower specificity constant, kcat/KM = 0.088 ± 0.023 × 103 M−1s−1 (kcat = 0.39 ± 0.05 s−1, KM = 4.4 ± 1.0 mM,) and the rate was not dependant on butanol concentration. The similarity of the α-methyl-β-ketopentanoate NAC thioester to the intermediate in 2 suggests that the Zea TE may not be able to process the growing polyketide until C2-C7 cyclization and the subsequent aromatization have occurred. The Zea TE may thus act as a gatekeeper ensuring rapid release of aromatized intermediate during biosynthesis of 5. Kinetic characterization of the substrate specificity of the Zea TE with more native-like substrates is needed to rigorously test hypothesis.

This gatekeeper activity may play a role in controlling iterative cycling on PKS13. Evidence supports iterative cycling in fungal PKSs (25), type II PKSs (26, 27) and chalcone synthases (28) as being controlled by the overall chain length of the growing polyketide product. Iterative processing of the polyketide intermediate by the synthase is terminated when the growing polyketide fills the cavity available in the synthase. PKS13 has been shown not to use this well-characterized mechanism for controlling iterative cycling (5). Instead, the gatekeeper activity of the Zea TE (which is triggered by aromatization of the growing polyketide) may play a role in ensuring correct termination of iterative cycling and cleavage of the polyketide from PKS13. Recently, PLP-mediated off loading of a highly reduced polyketide has been shown to play a role in controlling iterative cycling of a fungal PKS (29, 30). In conjunction with our results on the Zea TE, we propose that substrate selectivity in the off loading step may control iterative cycling in some iterative PKS systems.

In summary, we have characterized the first macrolactone forming fungal PKS TE in vitro. In addition to macrocyclization the Zea TE catalyzes cross coupling to form esters and amides. We have also shown that the substrate specificity of the Zea TE suggests that it may play a role as a gatekeeper in the biosynthesis of zearalenone, ensuring that only appropriately functionalized intermediates can be released from the synthase. This may be a general mechanism seen in RAL biosynthesis.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This work was supported by Syracuse University, the University of Ottawa, and the Canadian Foundation for Innovation (CNB) and NIH R01GM085128 (YT)

Abbreviations: ACP, acyl carrier protein; DH, dehydratase; ER, enoyl reductase; KR, ketoreductase; KS, ketosynthase; MAT, malonyl-CoA:ACP acyltransferase; NAC, N-acetylcysteamine; PKS, polyketide synthase; PLP, pyridoxal 5′-phosphate; PT, product template; RAL, resorcylic acid lactone; SI, supporting information; SAT, starter unit:ACP transacylase; TE, thioesterase.

Supporting Information Available Experimental details including, synthesis of substrates and standards, and all kinetic data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

REFERENCES

- 1.Winssinger N, Barluenga S. Chem. Commun. 2007:22–36. doi: 10.1039/b610344h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang S, Xu Y, Maine EA, Wijeratne EMK, Espinosa-Artiles P, Gunatilaka AAL, Molnár I. Chem. Biol. 2008;15:1328–1338. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reeves CD, Hu Z, Reid R, Kealey JT. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008;74:5121–5129. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00478-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim YT, Lee YR, Jin J, Han KH, Kim H, Kim JC, Lee T, Yun SH, Lee YW. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;58:1102–1113. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou H, Zhan J, Watanabe K, Xie X, Tang Y. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:6249–6254. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800657105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu HX, Tsai SC, Khosla C, Cane DE. Biochemistry. 2002;41:12590–12597. doi: 10.1021/bi026006d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsai SC, Miercke LJW, Krucinski J, Gokhale R, Chen JCH, Foster PG, Cane DE, Khosla C, Stroud RM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:14808–14813. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011399198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akey DL, Kittendorf JD, Giraldes JW, Fecik RA, Sherman DH, Smith JL. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006;2:537–542. doi: 10.1038/nchembio824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giraldes JW, Akey DL, Kittendorf JD, Sherman DH, Smith JL, Fecik RA. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006;2:531–536. doi: 10.1038/nchembio822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boddy CN, Schneider TL, Hotta K, Walsh CT, Khosla C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:3428–3429. doi: 10.1021/ja0298646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crawford JM, Thomas PM, Scheerer JR, Vagstad AL, Kelleher NL, Townsend CA. Science. 2008;320:243–246. doi: 10.1126/science.1154711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linnemannstons P, Schulte J, del Mar Prado M, Proctor RH, Avalos J, Tudzynski B. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2002;37:134–148. doi: 10.1016/s1087-1845(02)00501-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burckhardt S, Ley SV. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2002;1:874–882. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aldrich CC, Venkatraman L, Sherman DH, Fecik RA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:8910–8911. doi: 10.1021/ja0504340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He WG, Wu JQ, Khosla C, Cane DE. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006;16:391–394. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.09.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kohli RM, Walsh CT, Burkart MD. Nature. 2002;418:658–661. doi: 10.1038/nature00907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klibanov AM. Nature. 2001;409:241–246. doi: 10.1038/35051719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nevarez DM, Mengistu YA, Nawarathne IN, Walker K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:5994–6002. doi: 10.1021/ja900545m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walker K, Long R, Croteau R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:9166–9171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082115799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walker K, Croteau R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:13591–13596. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250491997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang M, Boddy CN. Biochemistry. 2009;47:11793–11803. doi: 10.1021/bi800963y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma KK, Boddy CN. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007;17:3034–3037. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gokhale RS, Hunziker D, Cane DE, Khosla C. Chem. Biol. 1999;6:117–125. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(99)80008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weissman KJ, Smith CJ, Hanefeld U, Aggarwal R, Bycroft M, Staunton J, Leadlay PF. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1998;37:1437–1440. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980605)37:10<1437::AID-ANIE1437>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma SM, Zhan J, Watanabe K, Xie X, Zhang W, Wang CC, Tang Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:10642–10643. doi: 10.1021/ja074865p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicholson TP, Winfield C, Westcott J, Crosby J, Simpson TJ, Cox RJ. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 2003:686–687. doi: 10.1039/b300847a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tang Y, Lee TS, Khosla C. PLOS Biol. 2004;2:227–238. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jez JM, Bowman ME, Noel JP. Biochemistry. 2001;40:14829–14838. doi: 10.1021/bi015621z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu X, Vogler C, Du L. J. Nat. Prod. 2008;71:957–960. doi: 10.1021/np8000514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gerber R, Lou L, Du L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:3148–3149. doi: 10.1021/ja8091054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.