Abstract

5,6,7,8-Tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) is an essential cofactor of nitric oxide synthases (NOSs). Oxidation of BH4, in the setting of diabetes and other chronic vasoinflammatory conditions, can cause cofactor insufficiency and uncoupling of endothelial NOS (eNOS), manifest by a switch from nitric oxide (NO) to superoxide production. Here we tested the hypothesis that eNOS uncoupling is not simply a consequence of BH4 insufficiency, but rather results from a diminished ratio of BH4 vs. its catalytically incompetent oxidation product, 7,8-dihydrobiopterin (BH2). In support of this hypothesis, [3H]BH4 binding studies revealed that BH4 and BH2 bind eNOS with equal affinity (Kd ≈ 80 nM) and BH2 can rapidly and efficiently replace BH4 in preformed eNOS-BH4 complexes. Whereas the total biopterin pool of murine endothelial cells (ECs) was unaffected by 48-h exposure to diabetic glucose levels (30 mM), BH2 levels increased from undetectable to 40% of total biopterin. This BH2 accumulation was associated with diminished calcium ionophore-evoked NO activity and accelerated superoxide production. Since superoxide production was suppressed by NOS inhibitor treatment, eNOS was implicated as a principal superoxide source. Importantly, BH4 supplementation of ECs (in low and high glucose-containing media) revealed that calcium ionophore-evoked NO bioactivity correlates with intracellular BH4: BH2 and not absolute intracellular levels of BH4. Reciprocally, superoxide production was found to negatively correlate with intracellular BH4:BH2. Hyperglycemia-associated BH4 oxidation and NO insufficiency was recapitulated in vivo, in the Zucker diabetic fatty rat model of type 2 diabetes. Together, these findings implicate diminished intracellular BH4:BH2, rather than BH4 depletion per se, as the molecular trigger for NO insufficiency in diabetes.

Keywords: nitric oxide, diabetes, endothelial dysfunction

NITRIC OXIDE (NO) is a biological messenger that is produced by enzymes of the nitric oxide synthase (NOS) gene family, comprising endothelial (eNOS), inducible (iNOS), and neuronal (nNOS) isoforms. In the vasculature, eNOS-derived NO plays a pivotal role in physiological regulation of vessel tone and inflammatory status (58). Diminished availability of eNOS-derived NO is common to chronic vascular disorders that share endothelial dysfunction as a hallmark, e.g., diabetes (11, 37, 60), hypertension (28), and atherosclerosis (28, 46). While the mechanistic basis for this attenuated NO bioavailability is uncertain, both slowed NO synthesis and accelerated NO scavenging by reactive oxygen species (ROS) have been implicated as causes (16). In contrast, levels of eNOS protein are typically unchanged or paradoxically increased. Oxidative stress, imposed by excessive ROS production, constitutes a unifying feature and likely generic trigger for endothelial dysfunction in chronic vascular conditions (1).1

The redox-sensitive NOS cofactor (6R)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) is required for NO synthesis by all NOS isoforms. Whereas fully reduced tetrahydropterins support catalysis by NOSs, oxidized pterin species are catalytically incompetent (e.g., 7,8-dihydrobiopterin, BH2) (14, 27, 47). Electroparamagnetic resonance (EPR) studies showed that in the absence of BH4 (or presence of excess BH2), superoxide is the sole in vitro product of recombinant eNOS (51). In the absence of BH4, electron transfer within eNOS becomes “uncoupled” from l-arginine oxidation and ferrous dioxygen releases superoxide with a finite probability (51).

BH4 is prone to oxidation in vitro, readily occurring in laboratory solutions unless suppressed by chemical reductants and low temperature (10, 25). BH4 oxidation has also been found to occur in vascular cells, in the setting of oxidative stress associated with hypertension (28), atherosclerosis (29), and diabetes (33). Depletion of BH4 in oxidatively stressed endothelial cells (ECs) can result in product switching from NO to O2•−. Moreover, uncoupled eNOS may initiate a futile feed-forward cascade whereby the reaction product of NO and O2•−, ONOO−, elicits further BH4 oxidation (26, 34), progressively more eNOS uncoupling (61), and a downward spiral in levels of vascular NO bioactivity.

Oxidant stress, such as that associated with hyperglycemia, can potentially overwhelm the natural antioxidant defense mechanisms that serve to maintain BH4 in its reduced form, resulting in endothelial dysfunction. Glutathione (GSH), vitamin C, and vitamin E are key cellular antioxidants that preserve BH4, and diminished levels of these antioxidants are evident in diabetic patients (57, 59). Vitamin C treatment was shown to increase eNOS activity in ECs specifically via chemical stabilization of BH4 (9, 21). Augmentation of endothelial BH4 levels by adenovirus-mediated overexpression of the rate-limiting enzyme for BH4 synthesis, GTP cyclohydrolase 1 (GTPCH), was similarly found to restore eNOS activity in high-glucose-treated human ECs in culture (7) in rodent blood vessels of ApoE-null (42) and streptozotocin models (36) of atherosclerosis and diabetes, respectively. BH4 supplementation was also shown to acutely improve endothelial dysfunction in chronic smokers (20) and patients with hypercholesterolemia (46), diabetes (37, 44), or ischemia-reperfusion injury (48). In aortas of mice with deoxycorticosterone acetate salt-induced (DOCA-salt) hypertension, production of NOS-derived ROS is markedly increased and BH4 oxidation is evident (28). Treatment of DOCA-salt mice with oral BH4 attenuated vascular ROS production, increased NO levels, and blunted hypertension compared with non-hypertensive control mice (28). Thus multiple lines of evidence implicate BH4 oxidation as a basis for eNOS uncoupling in vascular conditions associated with oxidative stress.

We hypothesized that the accumulation of BH2 in ECs may bind eNOS with significant avidity and hence directly suppress eNOS activity, rather than being an inert product of BH4 oxidation. If so, the intracellular ratio of BH4 to BH2, rather than the level of intracellular BH4 per se, could be the key determinant of eNOS-derived NO vs. production. To test this possibility, we examined the influence of BH4 oxidation on binding to eNOS and the extent to which BH4 oxidation occurs in ECs and animal tissues after exposure to diabetic levels of glucose. We show that eNOS binds BH4 and BH2 with equal affinity and that BH2 displaces eNOS-bound BH4 in vitro. We also demonstrate a glucose-induced switch from NO to superoxide production through eNOS uncoupling in ECs, determined by the BH4-to-BH2 ratio. Our findings implicate the intracellular BH4-to-BH2 ratio, not simply BH4 amount, as a critical in vivo determinant of eNOS product formation. Accordingly, diminished BH4:BH2 is likely to be the fundamental molecular link between oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction in diabetes and other chronic vasoinflammatory conditions.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Pterin analogs were purchased from B. Schircks (Jona, Switzerland). Additional chemicals and solvents, unless otherwise stated, were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). HPLC mobile phase and samples were prepared with water with >18-MΩ resistance water (Millipore, MA).

Cell culture

Murine ECs (sEnd.1) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, GIBCO Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. This cell line was a gift from Dr. Patrick Vallance (University College, London) and originally established from a mouse skin capillary endothelioma induced by infection with a retrovirus harboring an insert that encodes polyoma middle T antigen (56). Notably, sEnd.1 cells have not been reported to display features inconsistent with their EC origin. Cells were grown to confluence in T75 flasks or six-well plates and harvested immediately before use. RFL-6 fibroblasts were a gift from Dr. Ferid Murad (University of Texas at Houston) and were grown in Ham’s F-12 medium (Invitrogen) containing 10% fetal calf serum. All cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. All culture media were supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen).

Purification of recombinant eNOS

Bovine eNOS was purified from BL21 E. coli harboring both pGroELS and pCW-eNOS expression plasmids (31, 32). Purified eNOS was assayed for enzyme activity based on NOx accumulation with the Griess assay method (55) and shown to be >90% pure by protein staining of polyacrylamide gels with Coomassie blue (data not shown).

[3H]BH4 synthesis

To quantify and characterize BH4 binding (6R)-[3H(6)]BH4 ([3H]BH4) was custom synthesized by complete reduction of 7,8-BH2 with sodium borotritide (New England Nuclear/Perkin Elmer). Although the initial product was (6R,6S)-[3H(5,6)]BH4, exchange of N5 tritium on the biopterin ring with solvent protons, followed by HPLC purification by cation exchange chromatography on a Partisil 10 SCX column, allowed isolation of [3H]BH4 stereoisomers labeled at the 6 position. The R stereoisomer was used in the present study and is designated [3H]BH4 throughout this report. [3H]BH4 was stored as a 1 mM stock solution in equimolar HCl at −70°C.

[3H]BH4 binding to eNOS

[3H]BH4 binding assays were performed with polyvinylidene difluoride membrane-bottom 96-well filtration plates (Millipore). Before the assay, filtration membranes were sequentially washed under vacuum once with 100 µl of ethanol-water (50%) and then twice with 200 µl of Tris (50 mM) pH 7.6. All binding reactions contained Tris (50 mM) pH 7.6, DTT (1 mM), eNOS (10 pmol), the desired concentration of [3H]BH4, and other specified additions, comprising a final volume of 100 µl. Pseudoequilibrium binding was analyzed after sample incubation for 20 min at 23°C. Binding reactions were initiated by the addition of eNOS. For measurements of association rate, binding was initiated by addition of [3H]BH4. In dissociation experiments, eNOS (10 µl) was added to a 90-µl binding mixture including [3H]BH4; after a 15-min preincubation period, dissociation was initiated by addition of unlabeled BH4 at 100 µM final concentration. Displacement binding assays were performed after preincubation of [3H]BH4 with eNOS for 15 min, followed by incubation with desired concentrations of BH2 or BH4 for a further 30 min and then quantification of residual [3H]BH4-NOS complexes. All binding reactions were terminated by rapid filtration of the 96-well filter plates, followed by three washes with iced Tris buffer (50 mM, pH 7.6). Plates were air dried for 30 min, followed by the addition of 25 µl of scintillation cocktail (Optiphase, Wallac) and radioactivity counting in a MicroBeta plus scintillation counter (Perkin Elmer).

Analysis of [3H]BH4 binding

Equilibrium binding data, as well as association and dissociation kinetics, were analyzed with Prism (Graphpad Software) and Ligand (Biosoft, Cambridge, UK) programs. Binding isotherms were calculated based on the equation , where B is the concentration of bound ligand, Bmax is the total eNOS concentration, T is the total ligand concentration, and Kd is the concentration of [3H]BH4 that gives half-maximal binding. This formula derives from the basic equilibrium equation: [L][R]/[LR] = Kd, when L (total ligand concentration) is significantly greater than the free ligand concentration (R).

Western blotting

Cells were suspended in RIPA lysis buffer (in mM: 20 Tris ·HCl, 150 NaCl, 1 Na2EDTA, and 1 EGTA, with 1% Triton, 0.1% SDS, and 0.1 sodium deoxycholate, pH 7.4) containing a cocktail of protease inhibitors and subjected to four cycles of freezing-thawing in liquid nitrogen. Western blotting was carried out by standard techniques with anti-eNOS (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-GTPCH, and anti-GTPCH feedback regulatory protein (GFRP) antibodies.

Detection of endothelium-derived NO with RFL-6 cell cGMP reporter bioassay

Endothelium-derived NO bioactivity was measured based on the increase in cGMP elicited in RFL-6 reporter cells, after exposure to preconditioned media from sEnd.1 endothelial cells, as previously described (24).

Pterin quantification by HPLC and electrochemical detection

Cellular pterin levels were quantified with a modified HPLC method that utilizes sequential electrochemical and fluorescence detectors in series (15). Cells were harvested in PBS (pH 7.4) and pelleted by centrifugation (2,000 g, 1 min). Supernatants were discarded, and cells were resuspended in 300 µl of ice-cold acid precipitation buffer (0.1 M phosphoric acid, 0.23 M trichloroacetic acid), followed by centrifugation (12,000 g at 4°C) for 1 min. Two aliquots of supernatant (120 µl) were transferred into HPLC vials for the analysis of total biopterin, BH4, the quinonoid isoform of BH2 (qBH2), and 7,8-BH2, as described previously (15). Quantitation of BH4 and 7,8-BH2 was done by comparison with external standards after normalization for total protein content.

GSH measurement

For quantitation of GSH, a modified microtiter plate enzymatic recycling assay was used, adapted from the standard spectrophotometric assay (13).

Superoxide quantitation by lucigenin chemiluminescence

The production of ROS in response to elevated levels of glucose was measured by lucigenin-dependent chemiluminescence, as previously described (2).

Experimental animals

Studies used Zucker diabetic fatty (ZDF) and nondiabetic lean control (ZL) rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA), aged 8, 16, and 22 wk. Animals were allowed free access to rat chow and water throughout the study and housed in animal quarters maintained at 22°C with a 12:12-h light-dark cycle. ZDF rats were randomly divided into two groups. One group was treated daily with ebselen (Daiichi) dissolved in 5% CM-cellulose (Sigma) and administered by gavage in two daily doses of 5 mg/kg body weight commencing at 8 wk of age. A second group of ZDF and ZL rats received a similar amount and dosing schedule of unmedicated vehicle (5% CM-cellulose) by gavage. After death, rat lungs were harvested for pterin analysis as described above, and plasma was assayed for glucose content. Plasma glucose was quantified with a kit based on the modified Trinder color reaction, according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Raichem, San Diego, CA). The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

RESULTS

Characterization of [3H]BH4 binding to eNOS

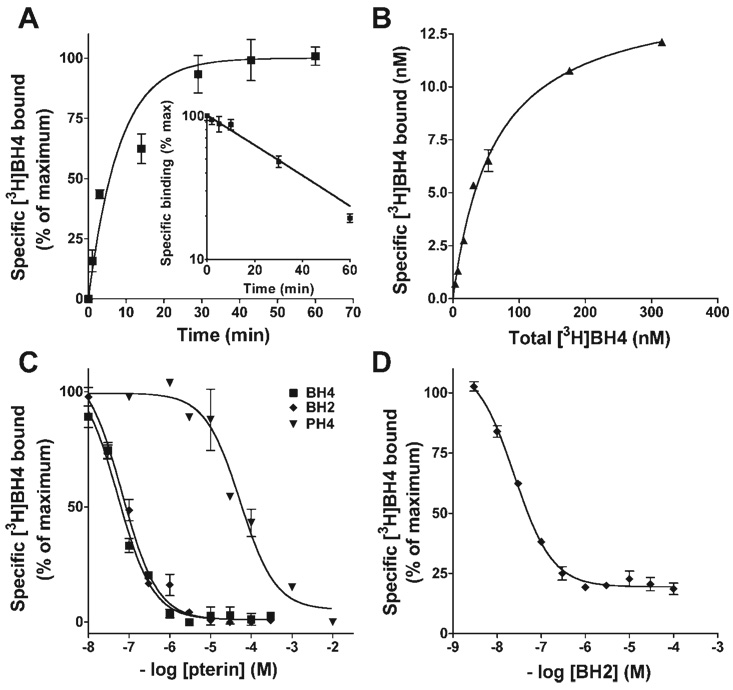

Studies were performed to define the kinetics of [3H]BH4 binding to purified recombinant bovine eNOS and the relative ability of unlabeled pterins to compete for binding. All binding assays were performed in the presence of 0.1 mM DTT to minimize [3H]BH4 oxidation. As shown in Fig. 1A, [3H]BH4 rapidly associates with eNOS; under the study conditions tested (50 nM [3H]BH4 and 10 pmol eNOS, at 22°C) half-maximal occupancy was obtained in 5.3 ± 1.4 min and binding was >95% complete by 20 min (n = 5). The dissociation of preformed [3H]BH4-eNOS complexes occurred with monophasic kinetics and was 50% complete at (T1/2) = 28.1 ± 2.5 min (see Fig. 1A, inset).

Fig. 1.

Characterization of 3H-labeled 5,6,7,8-tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) binding to purified recombinant bovine endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and competition by pterin analogs. A: kinetics of association and dissociation (inset) of [3H]BH4 binding (50 nM) to eNOS (10 pmol). For dissociation studies, [3H]BH4-eNOS complexes were formed during a 15-min preincubation, and residual complexes were analyzed at varying times after addition of a 2,000-fold molar excess of unlabeled BH4. B: pseudoequilibrium binding of [3H]BH4 to eNOS (10 pmol) after 15-min incubation. Calculated apparent BH4Kd = 82.1 ± 17.8 nM (n = 3). C: competition of unlabeled pterins for [3H]BH4 binding to eNOS. [3H]BH4 (50 nM) and eNOS (10 pmol) were incubated with indicated concentrations of 7,8-dihydrobiopterin (BH2), BH4, or tetrahydropterin (PH4); binding was terminated and analyzed after 15 min. D: displacement by BH2 of [3H]BH4 from preformed eNOS-[3H]BH4 complexes. Complexes were formed by preincubating eNOS (10 pmol) with [3H]BH4 (50 nM) for 15 min, and residual complexes were quantified 30 min after addition of indicated concentrations of BH2. All binding reactions were conducted at 22°C. Points are means ± SE of triplicate determinations.

Pseudoequilibrium binding of [3H]BH4 to eNOS was analyzed after incubation of purified eNOS (10 pmol) with indicated concentrations of [3H]BH4 for 20 min at 22°C (Fig. 1B). Binding was found to be saturable and reconciled by a single class of sites with apparent BH4Kd = 82.1 ± 17.8 nM. Competition binding studies were performed to compare the ability of nonradiolabeled pterins to vie for [3H]BH4 binding to eNOS. As shown in Fig. 1C, BH4 and BH2 bound eNOS with indistinguishable affinities; EC50 values were 59.3 ± 19.0 and 67.4 ± 11.1 nM, respectively. In contrast, tetrahydropterin (PH4), a BH4 analog that differs only in the lack of a 6-position dihydroxypropyl side chain, bound eNOS with >1,000-fold lower affinity (EC50 = 112 µM) versus BH4 or BH2. These results demonstrate that partial oxidation of the biopterin ring, from tetrahydro- to dihydro-, does not diminish the affinity for eNOS binding, whereas the 6-position side chain of biopterins is essential for high-affinity binding to eNOS.

Given our findings that BH2 binds eNOS with nanomolar affinity (equivalent to that of BH4) and BH4 dissociates from eNOS complexes in minutes at 22°C, we hypothesized that BH2 could efficiently replace BH4 when complexed with eNOS. To test this possibility, [3H]BH4-eNOS complexes were formed and remaining complexes were quantified 30 min after the addition of specified concentrations of BH2. As shown in Fig. 1D, [3H]BH4-eNOS complexes were progressively lost with increasing BH2 concentration, to a maximum extent of 80%; half-maximal [3H]BH4 displacement was observed when the concentrations of BH2 and [3H]BH4 approached equivalence (50 nM). Together, these binding studies indicate that if BH2 were to accumulate in ECs, it should effectively compete with BH4 for eNOS occupancy. Since BH2 binding to eNOS is known to cause enzyme uncoupling, this association would predictably result in a decrease in eNOS-derived NO and increase in eNOS-derived superoxide.

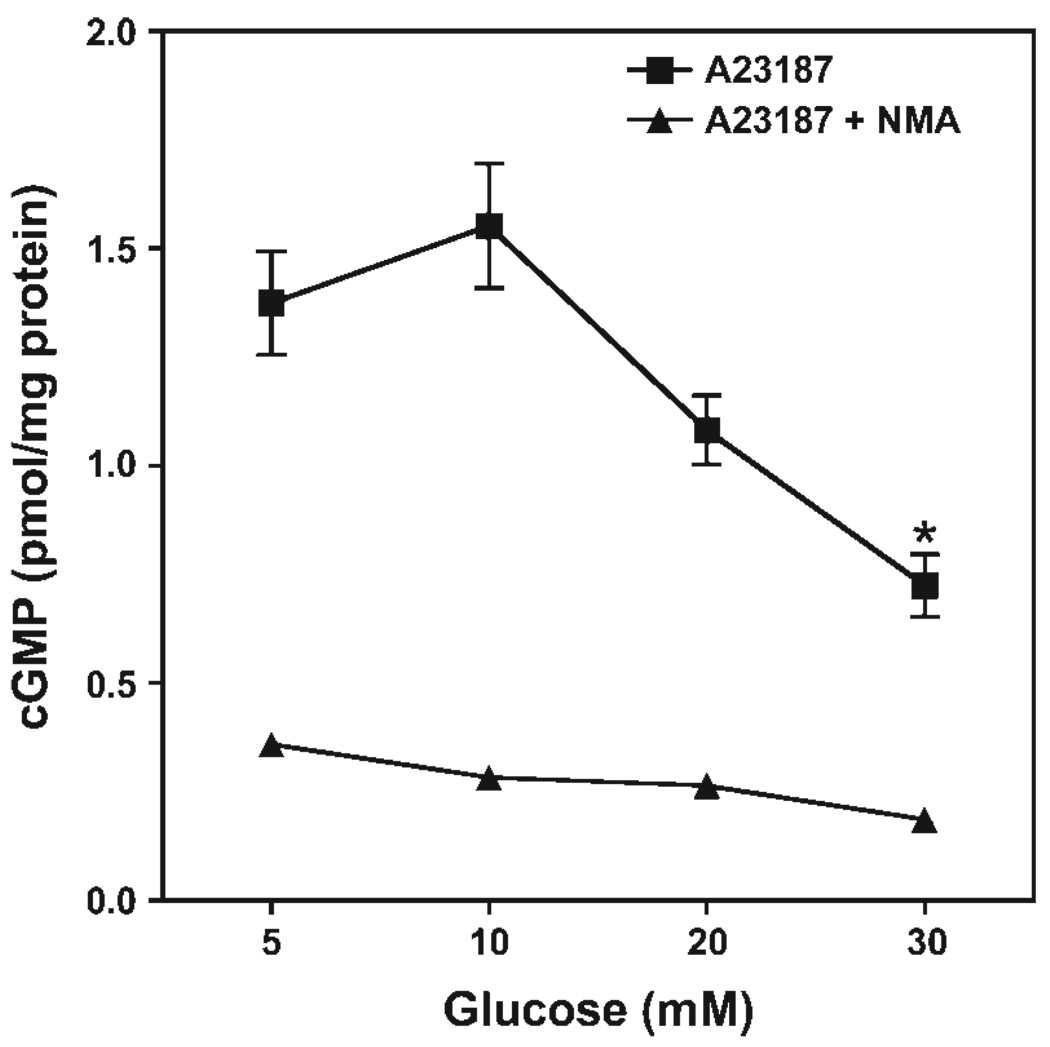

Attenuation of EC-derived NO production by elevated glucose

NO bioactivity was measured in the culture medium of murine endothelial cells (sEnd.1 line) after 20-min incubation with calcium ionophore (A-23187; 5 µg/ml). Quantification of NO bioactivity was determined based on the extent of increase in cGMP content following a 5-min incubation of phosphodiesterase-inhibited RFL-6 reporter cells (a soluble guanylyl cyclase-rich cell line) with EC-conditioned medium. As shown in Fig. 2, treatment of ECs for 48 h with progressively increasing glucose concentrations (from 5 to 30 mM) resulted in a concentration-dependent decrease in ionophore-elicited release of NO bioactivity. A ≈50% decrease in released NO bioactivity was observed in cells pretreated for 48 h with 30 mM relative to 5 mM glucose (P < 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Glucose-induced attenuation of nitric oxide (NO) production by endothelial cells. sEnd.1 cells were exposed to indicated concentrations of glucose for 48 h, and NO bioactivity was quantified in culture medium based on ability to elicit cGMP accumulation in the RFL-6 reporter cell line. sEnd.1 endothelial cells were incubated in the absence or presence of Nω-methyl-l-arginine (l-NMA, 3 mM) for 20 min before activation with A-23187 (5 µg/ml). High levels of glucose (30 mM) were found to markedly attenuate endothelial cell-derived NO bioactivity (*P < 0.05). Symbols are means ± SE of 3 replicate measurements.

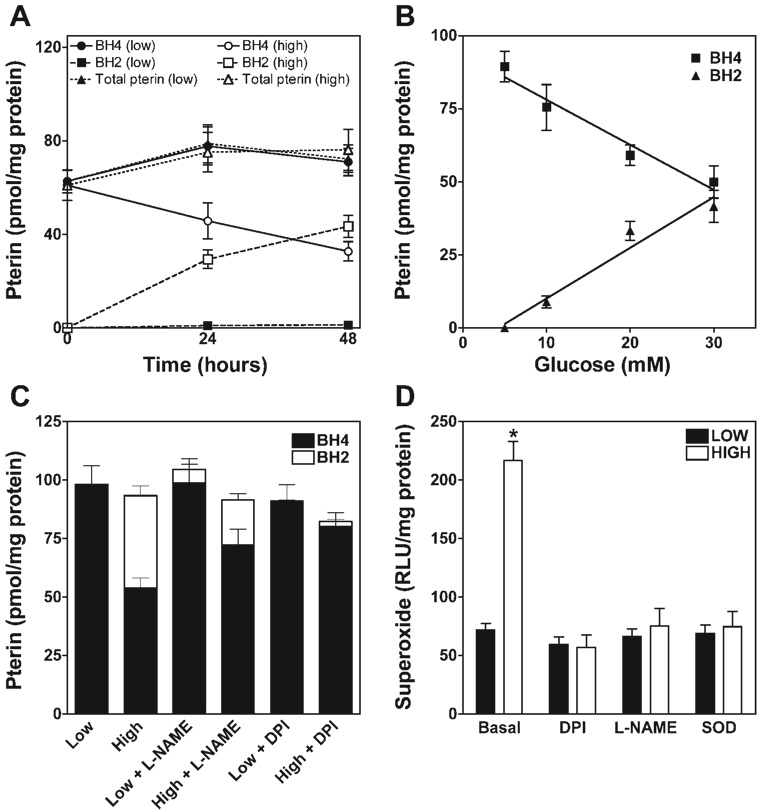

eNOS-dependent BH4 oxidation occurs in ECs after exposure to elevated glucose

The BH4 redox status in ECs was analyzed by HPLC, with combined electrochemical and fluorescence detection (15). Total pterin (BH4 + BH2 + biopterin) was indistinguishable in high (30 mM)- and low (5 mM)- glucose-treated ECs. This notwithstanding, high glucose was found to decrease intracellular BH4 by 40–50% in association with a reciprocal increase in BH2 content (P < 0.01; Fig. 3). The accumulation of BH2 was almost exclusively as 7,8-BH2; a significant contribution of the quinonoid tautomer, qBH2 (also known as 5,6-BH2), was not detected (not shown). Also, fully oxidized BH4 (i.e., biopterin) and its side chain cleaved product (pterin) were not detected in ECs after 48-h incubation in high-glucose medium (not shown).

Fig. 3.

Glucose elevation increases oxidation of BH4 to BH2 in a time-, concentration- and eNOS-dependent manner. sEnd.1 endothelial cells were exposed to glucose at low (5 mM), intermediate (10 and 20 mM), or high (30 mM) levels for 0, 24, or 48 h. A: time course of changes in levels of total pterins (BH4 and more oxidized species, circles), BH4 (squares), and BH2 (triangles) in cells exposed to low (open symbols) vs. high (closed symbols) levels of glucose. Whereas total pterin was unaffected, high glucose elicited significant oxidation of BH4 by 24 h (P < 0.05), and this was potentiated at 48 h. B: glucose concentration dependence for oxidation of BH4 to BH2 after 48-h exposure. BH4 oxidation in cells was not evident with low glucose medium but accelerated progressively as levels of medium glucose were increased. C: influence of the NOS-selective inhibitor Nω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME, 3 mM) and the flavoprotein-selective inhibitor diphenyleneiodonium (DPI, 10 µM) on high glucose-elicited BH4 oxidation to BH2 after 48-h exposure. Note that l-NAME significantly attenuated (P < 0.05) and DPI abolished high-glucose-elicited BH4 oxidation. D: rate of superoxide production, as determined by lucigenin chemiluminescence. High-glucose treatment significantly accelerated O2 •− production (P < 0.01), and this acceleration was abolished by treatment with DPI (10 µM), l-NAME (3 mM), or SOD (10,000 U). All indicated values are means ± SE of pterin levels as determined by HPLC-EC/fluorescence detection (n = 4–5). RLU, relative light unit.

BH2 accumulation in EC increased progressively with an increasing duration of glucose exposure (Fig. 3A) and with increasing glucose concentrations for a fixed duration (Fig. 3B). High-glucose-elicited oxidation of BH4 was prevented by >50% in the presence of a NOS-specific inhibitor, 3 Mm Nω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME), and abolished by diphenyleneiodonium (DPI), an agent that inhibits superoxide production by NOS and other flavoproteins (including NADPH oxidase) (Fig. 3C). These findings suggest a key role for superoxide and/or derived species in the oxidation of BH4 and implicate uncoupled eNOS as a key contributor. Accordingly, treatment of ECs with high glucose (30 mM) was associated with a significant increase in release (200%, Fig. 3D). The authenticity of this apparent superoxide was confirmed by its disappearance when cells were treated with 100 U of CuZn-SOD (Fig. 3D). High-glucose-induced superoxide formation was also blocked by treatment with a selective NOS inhibitor (l-NAME; Fig. 3D), identifying uncoupled eNOS as the source. Moreover, an identical degree of suppression of superoxide formation was observed in cells treated with either l-NAME or the general flavoprotein inhibitor DPI. Thus products of uncoupled eNOS are necessary for the increases in BH4 oxidation and production that we observe in high-glucose-treated ECs.

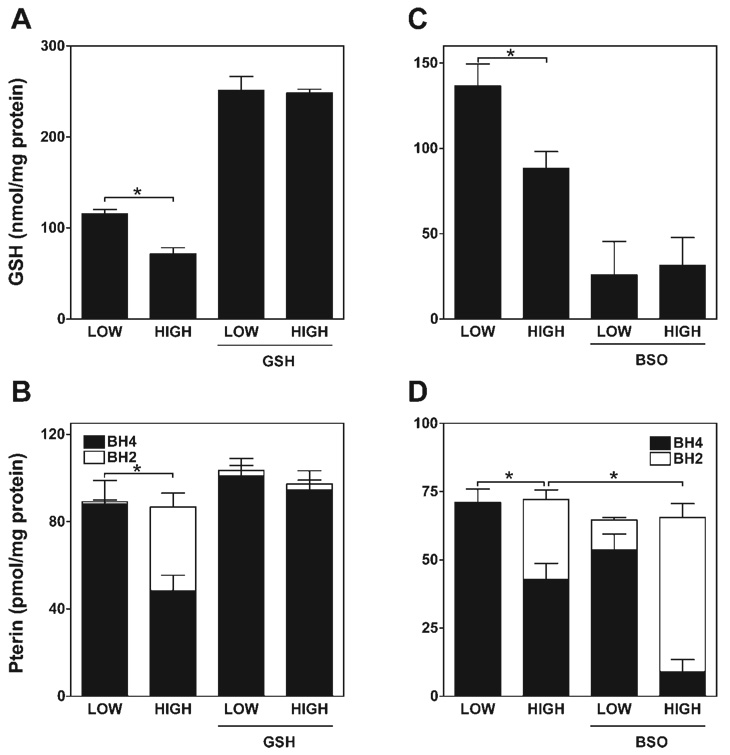

GSH levels determine extent of BH4 oxidation by glucose in ECs

Since GSH is the major EC reservoir of reduced thiols, we investigated whether glucose-elicited BH4 oxidation is concomitant with GSH oxidation and whether intracellular GSH levels determine the extent of BH4 oxidation. As shown in Fig. 4, A and B, 48-h treatment with 30 mM glucose resulted in a 35–40% relative decrease in both intracellular GSH and BH4, relative to levels observed in cells grown in 5 mM glucose. Intracellular GSH levels in ECs in 5 mM glucose medium were increased by 220% after incubation in medium containing 2 mM GSH ester (Fig. 4A). Notably, this level of GSH repletion in ECs afforded complete protection against both high-glucose-elicited BH4 oxidation and GSH depletion (Fig. 4B). Reciprocally, depletion of GSH to 20% of basal levels found in cells cultured in 5 mM glucose was obtained after pretreatment with a selective γ-glutamylcysteinyl synthase inhibitor, buthionine sulfoximine (BSO; Fig. 4C). This level of GSH depletion sensitized ECs to high-glucose-induced BH4 oxidation (from 40% BH4 oxidation without prior GSH depletion to 85% BH4 oxidation with GSH depletion) and was sufficient to elicit BH4 oxidation even in low-glucose medium (20%), where BH4 oxidation was not otherwise detected (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

Intracellular glutathione (GSH) protects against high-glucose-elicited BH4 oxidation. sEnd.1 cells were cultured with medium containing either low (5 mM) or high (30 mM) levels of glucose. Cells were then harvested after 48 h, and both GSH and pterin content were measured. A and C: impact of high glucose on GSH levels and effects of GSH repletion (by cotreatment with 1 mM GSH ethyl ester) and depletion [by block of GSH synthesis with 100 µM buthionine sulfoximine (BSO)]. Results show that high glucose exposure significantly diminishes GSH content in endothelial cells (ECs) on its own (*P < 0.05), and this is prevented by GSH supplementation and potentiated by inhibition of GSH synthesis. B and D: impact of GSH repletion and depletion on high glucose-elicited BH4 oxidation. Results show that BH4 oxidation is prevented when GSH levels in ECs are enhanced and accentuated (*P < 0.01) when GSH is depleted. All indicated values are means ± SE (n = 5).

BH4-to-BH2 ratio determines extent of eNOS coupling in high-glucose-treated EC

If BH4 oxidation is the primary basis for eNOS uncoupling, one would predict that BH4 supplementation would rapidly reinstate NO synthesis by uncoupled eNOS. This prediction is supported by results from multiple in vitro and in vivo studies showing that administration of BH4 acutely enhances NO bioactivity and suppresses eNOS-derived superoxide generation (1). Nonetheless, the possibility exists that progressive oxidation of administered BH4 would ultimately result in intracellular BH2 buildup, leading to increased binding of BH2 to eNOS and a consequent long-term worsening of eNOS uncoupling. To evaluate the more long-lived consequences of biopterin supplementation, we investigated the extent to which eNOS coupling and biopterin oxidation in EC were influenced by 24-h incubation with either BH4 or BH2 (Fig. 5).

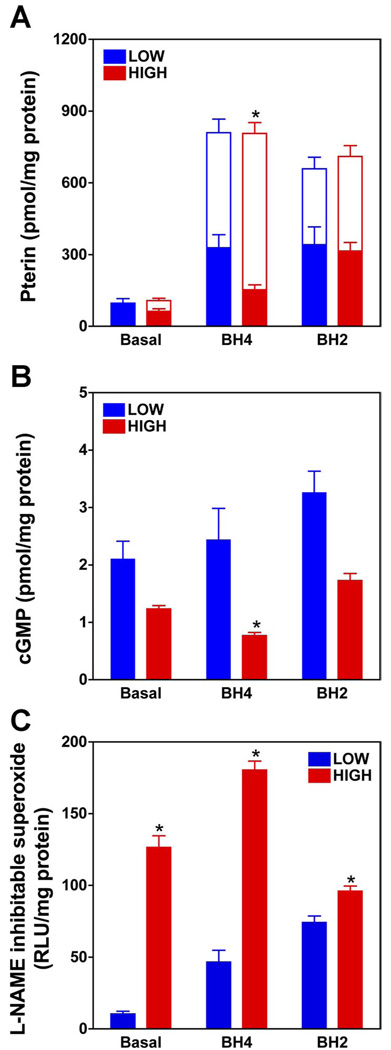

Fig. 5.

Pterin supplementation (24 h) increases intracellular BH4 levels in low- and high-glucose-treated ECs; however, this is associated with BH2 accumulation and failure to improve or worsened eNOS coupling. sEnd.1 cells were grown in high (30 mM) or low (5 mM) glucose-containing media, and after 24 h cells were either supplemented with BH4 (10 µM) or BH2 (10 µM) or left unsupplemented (basal). After a further 24 h, assays were performed to quantify intracellular biopterins (BH4 and BH2; A), release of NO (B), and production of superoxide (C). Intracellular levels of BH4 (filled bars) and BH2 (open bars) were quantified by HPLC, and release of NO bioactivity was assessed based on cGMP accumulation in RFL-6 reporter cells. Superoxide production was quantified based on the difference in lucigenin chemiluminescence in the absence and presence of 3 mM l-NAME. Values are means ± SE (n = 5). *P < 0.05.

As shown in Fig. 5A, incubation of ECs with a 10 µM concentration of either BH4 or BH2, in both low- and high-glucose-containing medium (5 and 30 mM, respectively), resulted in a similar 10-fold increase in total intracellular biopterin (BH4 + BH2), compared with ECs grown in non-biopterin-supplemented medium. Whereas total biopterin in low-glucose-grown ECs was found to be exclusively BH4 in non-biopterin-supplemented medium (i.e., BH2 was undetectable), in both BH4- and BH2-supplemented ECs BH4 levels constituted ≤60% of total biopterin (with BH2 as the remainder). In high-glucose medium, BH4 supplementation of ECs was associated with markedly greater levels of intracellular BH2 than in ECs in low-glucose medium (85% and 40% of total biopterin as BH2, respectively). Despite the enhanced accumulation of BH2 in ECs maintained in BH4-supplemented high-glucose medium, it is notable that the absolute level of BH4 in these cells was more than twofold that measured in high-glucose-treated ECs that were not BH4 supplemented (see Fig. 5A).

Treatment of non-biopterin-supplemented ECs with high glucose (30 mM) vs. low glucose (5 mM) resulted in a 40–50% decrease in A-23187-elicited NO bioactivity (Fig. 5B) and a ≈500% increase in superoxide generation that was fully prevented by addition of a selective NOS inhibitor (l-NAME) to the superoxide assay mix (Fig. 5C). Whereas supplementation of ECs with BH4 had no significant effect on NO bioactivity elicited in low-glucose medium, in high-glucose medium a paradoxical 40% decrease in NO bioactivity was observed, relative to non-biopterin-supplemented ECs (FIG. 5B). Notably, this apparent increase in eNOS uncoupling was concomitant with a paradoxical doubling of absolute levels of intracellular BH4 (Fig. 5A). Despite a BH4 supplementation-evoked doubling of BH4 levels, it is notable that a far greater decrease in the intracellular ratio of BH4 to BH2 was observed in non-supplemented vs. BH4-supplemented ECs (1:1 vs. 1:6, respectively). These findings reveal that the extent of eNOS coupling correlates inversely with the ratio of intracellular BH4 to BH2, but not absolute levels of intracellular BH4.

In contrast to findings with BH4-supplemented ECs in high-glucose medium, supplementation with BH2 resulted in a similar extent of total biopterin accumulation, but substantially greater accumulation as BH4 (BH4:BH2 ≈ 1:6 vs. 1:1, respectively). Accordingly, BH2 supplementation of ECs was associated with a twofold increase in absolute BH4 levels, relative to levels observed in ECs supplemented with an identical concentration of BH4. The relative increase in accumulation of BH4 in BH2-supplemented vs. BH4-supplemented ECs was associated with a modestly enhanced extent of eNOS coupling, as evidenced by a 45% increase in evoked NO bioactivity and a 25% decrease in superoxide generation (Fig. 5, B and C).

Contribution of mitochondrion-derived superoxide to high-glucose-elicited BH4 oxidation in ECs

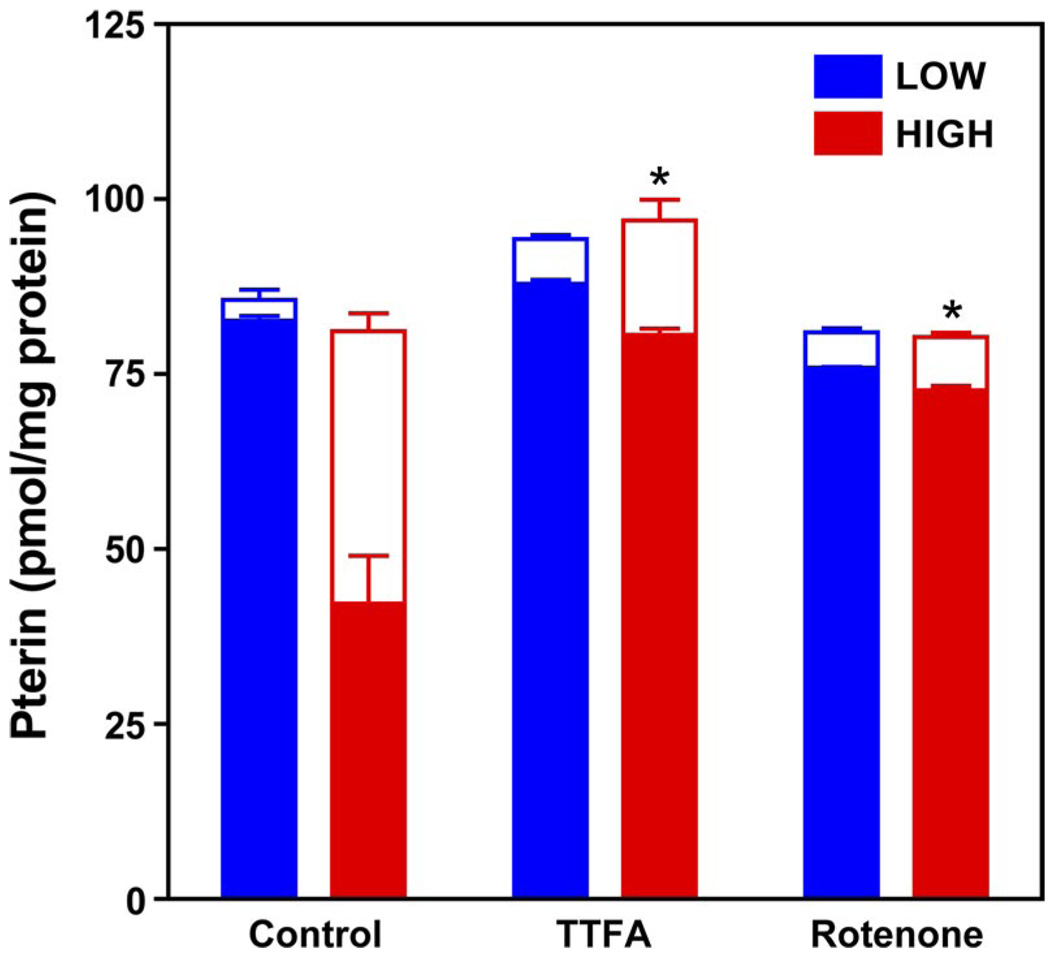

Having found that eNOS-derived superoxide is necessary for sustained BH4 oxidation in high-glucose-treated ECs, we questioned whether mitochondrion-derived superoxide is required to initiate BH4 oxidation and eNOS uncoupling. Notably, the mitochondrial electron transport chain is considered to be the predominant source of superoxide in normally respiring cells, and elevated glucose is known to increase mitochondrial respiration and thereby accelerate mitochondrion-derived superoxide generation (35, 45). To test whether mitochondrion-derived superoxide plays a role in high-glucose-induced BH4 oxidation, we assessed whether selective inhibitors of the mitochondrial electron transport chain afford protection against high-glucose-induced BH4 oxidation in ECs. As shown in Fig. 6, glucose-elicited BH4 oxidation was markedly and significantly prevented by coincubation of ECs with selective inhibitors of mitochondrial electron transport complexes I or II [2 µM rotenone and 5 µM thenoyltrifluoroacetone (TTFA), respectively]. These findings implicate a role for mitochondrion-derived superoxide in the genesis of high-glucose-induced BH4 oxidation, leading to eNOS uncoupling.

Fig. 6.

Prevention of BH4 oxidation by mitochondrial electron transport chain inhibitors. Cells were grown in low (5 mM; black bars) or high (30 mM; red bars) glucose-containing media for 48 h. Rotenone (2 µM) and thenoyltrifluoroacetone (TTFA, 5 µM), inhibitors of complexes I and II of the mitochondrial electron transport chain, respectively, were added after the initial 24 h, and cells were harvested for assay of BH4 and BH2 by HPLC-EC. BH4 (filled bars) oxidation to BH2 (open bars) was significantly attenuated by both TTFA and rotenone treatment (*P < 0.01). Values are means ± SE (n = 3).

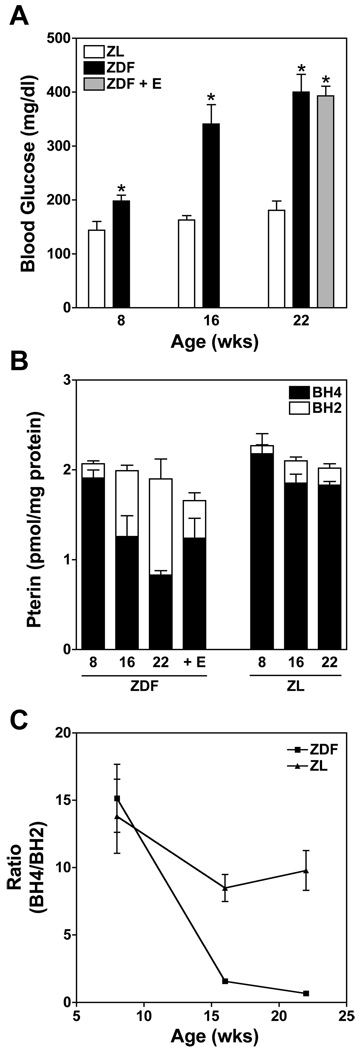

BH4oxidation in vivo

To assess whether the high-glucose-evoked BH4 oxidation that we observed in EC culture studies has relevance in vivo, we sought to determine the relationship between plasma glucose and tissue BH4 oxidation in a rodent model of type II diabetes and metabolic syndrome, the Zucker diabetic fatty (ZDF) rat. Unlike Zucker lean (ZL) control rats, ZDF rats develop moderate hyperglycemia by 8 wk of age, with glucose levels of 197.9 ± 11.7 mg/dl vs. 144.8 ± 26.2 mg/dl in age-matched ZL controls (Fig. 7A). By 16 wk of age, ZDF rats become severely hyperglycemic, with resting glucose levels of 341.6 ± 35.9 mg/dl (vs. 162.8 ± 8.2 mg/dl in ZL) that reach 400.2 ± 33.6 mg/dl by 22 wk (vs. 180.9 ± 17.8 in ZL). These increases in plasma glucose are mirrored by a progressive oxidation of BH4 without any detected change in total pterin content. This is shown for lung tissue in Fig. 7B; similar increases in BH4 oxidation were observed in heart, kidney, and brain (not shown). This aging-associated decrease in the BH4-to-BH2 ratio in ZDF rat lungs (but not ZL controls) was apparent by 16 wk (Fig. 7C; P < 0.05). Notably, we previously reported that at 16 wk and beyond, ZDF rats exhibit marked NO insufficiency, loss of endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation, and accumulation of 3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT) in tissue proteins, and that each of these measures of endothelial dysfunction was protected by cotreatment with the peroxynitrite scavenger ebselen (30). As shown in Fig. 7B, ebselen similarly protected against BH4 oxidation in 22-wk ZDF rats, consistent with a role for peroxynitrite or a related oxidant in the mediation of glucose-elicited BH4 oxidation.

Fig. 7.

Oxidation of BH4 in association with increasing plasma glucose levels in the Zucker diabetic fatty (ZDF) rat model of type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome. Comparison between age-dependent changes in plasma glucose and pterin redox status in ZDF, ZDF + ebselen treatment (E; 5 mg/kg by gavage twice daily) and Zucker nondiabetic lean (ZL) control rats. A: progressive increase in plasma glucose levels as ZDF rats age, while no change is observed in age-matched ZL rats. Increased plasma glucose in ZDF rats is unaffected by ebselen, a peroxynitrite scavenger and antioxidant (*P < 0.05). B: progressive oxidation of BH4 in lungs of aging ZDF rats but not ZL control rats. Ebselen affords significant protection against BH4 oxidation in ZDF rats. C: relationship between age and ratio of BH4 to BH2 in ZDF compared with ZL control rats. At 22 wk the BH4-to-BH2 ratio is significantly decreased in ZDF compared with ZL rats (n = 6). Values are means ± SE (n = 6).

DISCUSSION

Diminished NO bioactivity is a significant predictor of cardiovascular risk (4, 40) and a hallmark of endothelial dysfunction (18). NO insufficiency has been implicated in the etiology and progression of major chronic vasoinflammatory conditions, including diabetic vasculopathy (54). Mitochondrial superoxide overproduction is considered to provide a trigger for metabolic derangements that mediate diabetic complications (6). While scavenging of NO by superoxide offers a simple explanation for consumption of NO bioactivity in diabetic blood vessels, the peroxynitrite product of this reaction can further compromise NO bioactivity by promoting the oxidation of BH4, leading to eNOS uncoupling. Oxidation of BH4 and eNOS uncoupling has previously been observed in genetic models of type 1 and type 2 diabetes (3, 41). An earlier report by Vasquez-Vivar and colleagues (52) provided the first evidence of BH2 binding to recombinant eNOS in vitro, based on an EPR-detectable increase in superoxide formation. Here we extend this finding with the first direct quantitative analysis of biopterin binding to eNOS.

Using an EC model of hyperglycemia-elicited eNOS uncoupling, we provide evidence for in vivo binding of BH2 to eNOS, implicating BH2-eNOS assembly as a key effector of diabetic vasculopathies. Analysis of [3H]BH4 binding revealed that catalytically incompetent BH2 competes for eNOS occupancy with an affinity identical to that of the active cofactor, BH4. Furthermore, BH2 exchanges rapidly with BH4 on preformed eNOS complexes in vitro, achieving half-maximal substitution within 20 min at 22°C—this exchange rate is likely to be still more rapid at 37°C in cells. Importantly, levels of glucose known to be common in diabetic patients (30 mM) were found to elicit oxidant stress in ECs in culture to an extent that markedly perturbs EC pterin redox balance in favor of BH2 accumulation. Accumulated BH2 in ECs increases with increasing concentrations of glucose in the extracellular milieu, is progressive with time (for a given glucose concentration), and is coupled to levels of intracellular GSH. The accumulated BH2 in high-glucose-treated ECs was implicated as a trigger for eNOS uncoupling. Notably, high-glucose-elicited superoxide production was eradicated within minutes of exposure to a NOS-selective inhibitor, confirming eNOS as the dominant source. Accelerated peroxynitrite formation, inferred from accumulated 3-NT modification of proteins, provides further support for a switch in eNOS toward oxidant generation, rather than NO.

Our findings argue for a revised mechanistic view regarding the role of BH4 oxidation in endothelial dysfunction. The results suggest that the fundamental determinant of NO bioactivity conveyed by ECs in blood vessels is the balance between intracellular BH4 and its primary two-electron oxidation product BH2—not absolute quantities of BH4 as has generally been thought (1). This conclusion is supported by in vitro analyses of [3H]BH4 binding to purified recombinant eNOS and cell culture studies of the consequences of biopterin supplementation on total biopterin levels, BH4:BH2 redox balance, and associated changes in eNOS function. Notably, despite a two-fold increase in intracellular BH4 in 24-h BH4-supplemented, high-glucose-treated ECs, an even greater accumulation of BH2 was observed (12-fold), accompanied by hallmark features of increased eNOS uncoupling, i.e., diminished NO bioactivity (40%) and increased superoxide generation (200%). Thus eNOS uncoupling was found to worsen with BH4 supplementation of ECs, despite an increase in absolute levels of BH4. In contrast, while BH2 supplementation of high-glucose-treated ECs also resulted in a substantial increase in total biopterin (equal to that observed with BH4 supplementation), this was not associated with a decrease in the BH4-to-BH2 ratio vs. non-biopterin-supplemented ECs (BH4:BH2 ≈ 1:1 in each case) and resulted in a modest improvement in eNOS coupling (enhanced release of NO bioactivity and diminished superoxide production). The opposite consequences of BH4 and BH2 supplementation on eNOS coupling are best reconciled by a model in which BH4-to-BH2 ratios are the primary determinant of eNOS coupling in EC, rather than absolute levels of BH4.

Predictably, intracellular BH4:BH2 would determine eNOS coupling in all biological settings where eNOS approaches saturation with biopterin cofactor (BH4 or BH2). Thus, with cofactor saturation, any perturbation in BH4:BH2 balance, up or down, would be expected to modulate the extent of eNOS coupling in the same direction. The condition of BH4 sufficiency would appear to be met in the present BH4 supplementation studies, where eNOS coupling was apparently diminished despite a doubling of BH4 content (owing to a >10-fold increase in BH2 and hence an overall decrease in BH4:BH2). In contrast, under conditions in which eNOS is subsaturated with its biopterin cofactor, administered biopterins could potentially improve eNOS coupling even under circumstances in which the balance of BH4:BH2 is somewhat diminished. Detailed modeling studies will be needed to define boundary conditions that predict the consequences of changing intracellular levels of BH4, BH2, and eNOS on levels of [eNOS-BH4] versus [eNOS-BH2] and hence eNOS coupling efficiency. In any case, it is evident that BH2 binding to eNOS can constitute a major contributor to hyperglycemia-induced eNOS uncoupling, as observed for ECs in the present study.

Concomitant increases in plasma glucose and tissue levels of BH2 in ZDF diabetic rats provide in vivo validation of results obtained with ECs in culture. Notably, we previously showed (5) that the peroxynitrite scavenger ebselen, administered to ZDF rats in the same regimen as in the present study, inhibits peroxynitrite production (evidenced by protection against protein 3-NT accumulation in plasma and blood vessels). In the present study, we show that ebselen similarly attenuates the progressive accumulation of tissue BH2. Protection against BH2 accumulation provides a likely explanation for ebselen’s effectiveness in limiting the progressive hyperglycemia-associated loss of endothelium-dependent vasodilatation and diminished NO bioactivity in ZDF rat blood vessels (5, 8).

Peroxynitrite is likely to be the biologically relevant oxidant of BH4 in high-glucose-treated ECs. Although superoxide reacts with BH4 in vitro, the rate constant is >10,000-fold slower (3.9 × 105 mol·l−1·s−1) (53) than its near-diffusion limited reaction with NO (6.7 × 109 mol·l−1·s−1) (22). Accordingly, NO would predictably outcompete BH4 for reaction with superoxide. Peroxynitrite formed by the NO/superoxide reaction could then oxidize BH4 as previously described (29, 34) and thereby promote eNOS uncoupling. Notably, the reaction of peroxynitrite with BH4 occurs via the intermediacy of the BH3 radical cation and with a first-step rate constant that is several times faster than the reaction with thiols (6 × 103 mol·l−1·s−1) (26). Inasmuch as intracellular thiol levels (millimolar) far exceed the estimated levels of BH4 in ECs (0.05–0.2 µM), thiol oxidation is expected to predominate over BH4 oxidation. This competition between thiols and BH4 for peroxynitrite-mediated oxidation provides one explanation for our observation that the extent of glucose-elicited BH4 oxidation in ECs is inversely related to GSH levels (Fig. 4).

Our finding that BH2 avidly binds eNOS and engenders uncoupling has important implications for possible uses of BH4 for therapy of endothelial dysfunction. Prior studies suggest a therapeutic potential of BH4 for reversal of endothelial dysfunction. While administration of high doses of BH4 has been shown to acutely restore endothelium-dependent (NO mediated) vasoactivity (12, 17, 19, 43, 46), studies have not yet addressed the more long-term consequences of BH4 administration in the setting of oxidative stress. The results reported here suggest that ongoing oxidative and nitrosative stress may elicit significant BH2 accumulation in ECs that opposes the desired NO-restoring action of administered BH4. Thus desensitization to the benefits of BH4 administration, or frank worsening, would result if BH2 was to progressively accumulate in ECs after repeated BH4 treatments. Accumulation of BH2 and consequent eNOS uncoupling also provides a likely explanation for paradoxical reports that BH4 treatment of vessel segments ex vivo (49) or animals (50) can worsen, rather than improve, endothelial dysfunction.

While BH4 is generally considered to be antioxidant, it can also be prooxidant. Indeed, BH4 undergoes autooxidation, yielding the quinonoid isoform of BH2 (qBH2, an isomer of 7,8-BH2) via reaction with molecular oxygen, generating superoxide in this process that can lead to oxidation of another molecule of BH4 (25). Once formed, qBH2 is nonenzymatically recycled to BH4, at the expense of extracellular thiols or other available reductants, creating a cycle of extracellular BH4 oxidation/reductant consumption. Oxidant stress imposed by this autooxidation of BH4 is a likely explanation for the paradoxical finding that high-glucose-treated ECs accumulate more BH4 when grown in BH2-supplemented medium compared with BH4-supplemented medium. Notably, an extracellular autooxidation chain reaction would predictably operate for BH4, but not BH2. Inasmuch as BH4 accumulation in tissues was also shown to be more efficient in mice treated with BH2, as opposed to BH4 (39), BH4 oxidation is likely to be important in vivo. Once in the cell, enzymatic regeneration of BH4 from BH2 will further consume pools of reducing potential (in the immediate form of reduced pyridine nucleotides) for support of the combined actions of dihydrofolate reductase (for substrate 7,8-BH2) and dihydropteridine reductase (for substrate qBH2). In contrast to extracellular redox cycling of BH4, intracellular redox cycling of BH4 would predictably impose an equivalent degree of oxidative stress in ECs supplemented with either BH2 or BH4. Thus, owing to the above-mentioned oxidative processes, BH4 supplementation therapy may have limited long-term benefit in improving eNOS coupling, despite the promise of reports suggested from the results of studies showing acute benefits.

Together, our findings recommend the following model for the initiation and progression of endothelial dysfunction in the setting of chronic vasoinflammation: Exposure of vascular endothelium to a prooxidative stimulus, including but not limited to diabetic levels of plasma glucose, triggers superoxide overproduction. This superoxide may derive from electron transport “leak” in mitochondria driven by high-glucose-accelerated metabolism in diabetes (as indicated by results depicted in Fig. 6) or other cell sources, such as inflammation-associated activation of NADPH oxidase (28). Reaction of superoxide with eNOS-derived NO will result in increased peroxynitrite synthesis that promotes BH4 oxidation and hence accumulation of BH2. Replacement of BH4 with BH2 in eNOS complexes would result in sustained eNOS-derived oxidant formation, perpetuating BH4 oxidation. At this stage, even after full resolution of the initiating oxidative insult, uncoupled eNOS could sustain the production of peroxynitrite, promote BH4 oxidation, and self-limit NO biosynthesis. According to this view, therapeutic approaches that can transiently recouple eNOS would provide a preferred means to interrupt the vicious cycle of endothelial dysfunction, engendering a sustained restoration of eNOS-derived NO production and a restoration of vascular health.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Paul Lane (Pharmacology Dept., Weill Medical College) for critical reading and assessment of this manuscript.

GRANTS

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HL-80702 (S. S. Gross), HL-46403 (S. S. Gross), and DK-45462 (M. S. Goligorsky).

Footnotes

This paper was presented at the 9th Cardiovascular-Kidney Interactions in Health and Disease Meeting at Amelia Island Plantation, Florida, on May 26–29, 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alp NJ, Channon KM. Regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by tetrahydrobiopterin in vascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:413–420. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000110785.96039.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antoniades C, Shirodaria C, Crabtree M, Rinze R, Alp N, Cunnington C, Diesch J, Tousoulis D, Stefanadis C, Leeson P, Ratnatunga C, Pillai R, Channon KM. Altered plasma versus vascular biopterins in human atherosclerosis reveal relationships between endothelial nitric oxide synthase coupling, endothelial function, and inflammation. Circulation. 2007;116:2851–2859. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.704155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bitar MS, Wahid S, Mustafa S, Al-Saleh E, Dhaunsi GS, Al-Mulla F. Nitric oxide dynamics and endothelial dysfunction in type II model of genetic diabetes. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;511:53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Britten MB, Zeiher AM, Schachinger V. Effects of cardiovascular risk factors on coronary artery remodeling in patients with mild atherosclerosis. Coron Artery Dis. 2003;14:415–422. doi: 10.1097/00019501-200309000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brodsky SV, Gealekman O, Chen J, Zhang F, Togashi N, Crabtree M, Gross SS, Nasjletti A, Goligorsky MS. Prevention and reversal of premature endothelial cell senescence and vasculopathy in obesity-induced diabetes by ebselen. Circ Res. 2004;94:377–384. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000111802.09964.EF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brownlee M. Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature. 2001;414:813–820. doi: 10.1038/414813a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cai S, Khoo J, Channon KM. Augmented BH4 by gene transfer restores nitric oxide synthase function in hyperglycemic human endothelial cells. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;65:823–831. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chander PN, Gealekman O, Brodsky SV, Elitok S, Tojo A, Crabtree M, Gross SS, Goligorsky MS. Nephropathy in Zucker diabetic fat rat is associated with oxidative and nitrosative stress: prevention by chronic therapy with a peroxynitrite scavenger ebselen. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:2391–2403. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000135971.88164.2C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.d’Uscio LV, Milstien S, Richardson D, Smith L, Katusic ZS. Long-term vitamin C treatment increases vascular tetrahydrobiopterin levels and nitric oxide synthase activity. Circ Res. 2003;92:88–95. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000049166.33035.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis MD, Kaufman S, Milstien S. The auto-oxidation of tetrahydrobiopterin. Eur J Biochem. 1988;173:345–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb14004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drexler H, Hornig B. Endothelial dysfunction in human disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1999;31:51–60. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gori T, Burstein JM, Ahmed S, Miner SE, Al-Hesayen A, Kelly S, Parker JD. Folic acid prevents nitroglycerin-induced nitric oxide synthase dysfunction and nitrate tolerance: a human in vivo study. Circulation. 2001;104:1119–1123. doi: 10.1161/hc3501.095358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griffith OW. Determination of glutathione and glutathione disulfide using glutathione reductase and 2-vinylpyridine. Anal Biochem. 1980;106:207–212. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90139-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gross SS, Jaffe EA, Levi R, Kilbourn RG. Cytokine-activated endothelial cells express an isotype of nitric oxide synthase which is tetrahydrobiopterin-dependent, calmodulin-independent and inhibited by arginine analogs with a rank-order of potency characteristic of activated macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;178:823–829. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)90965-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heales S, Hyland K. Determination of quinonoid dihydrobiopterin by high-performance liquid chromatography and electrochemical detection. J Chromatogr. 1989;494:77–85. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)82658-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heerdt PM, Holmes JW, Cai B, Barbone A, Madigan JD, Reiken S, Lee DL, Oz MC, Marks AR, Burkhoff D. Chronic unloading by left ventricular assist device reverses contractile dysfunction and alters gene expression in end-stage heart failure. Circulation. 2000;102:2713–2719. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.22.2713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heitzer T, Brockhoff C, Mayer B, Warnholtz A, Mollnau H, Henne S, Meinertz T, Munzel T. Tetrahydrobiopterin improves endothelium-dependent vasodilation in chronic smokers : evidence for a dysfunctional nitric oxide synthase. Circ Res. 2000;86:E36–E41. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.2.e36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heitzer T, Schlinzig T, Krohn K, Meinertz T, Munzel T. Endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and risk of cardiovascular events in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2001;104:2673–2678. doi: 10.1161/hc4601.099485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higashi Y, Sasaki S, Nakagawa K, Fukuda Y, Matsuura H, Oshima T, Chayama K. Tetrahydrobiopterin enhances forearm vascular response to acetylcholine in both normotensive and hypertensive individuals. Am J Hypertens. 2002;15:326–332. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(01)02317-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higman DJ, Strachan AM, Buttery L, Hicks RC, Springall DR, Greenhalgh RM, Powell JT. Smoking impairs the activity of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in saphenous vein. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1996;16:546–552. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.16.4.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang A, Vita JA, Venema RC, Keaney JF., Jr Ascorbic acid enhances endothelial nitric-oxide synthase activity by increasing intracellular tetrahydrobiopterin. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:17399–17406. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002248200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huie RE, Padmaja S. The reaction of NO with superoxide. Free Radic Res Commun. 1993;18:195–199. doi: 10.3109/10715769309145868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hurshman AR, Krebs C. Edmondson DE, Huynh BH, Marletta MA. Formation of a pterin radical in the reaction of the heme domain of inducible nitric oxide synthase with oxygen. Biochemistry. 1999;38:15689–15696. doi: 10.1021/bi992026c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishii K, Sheng H, Warner TD, Forstermann U, Murad F. A simple and sensitive bioassay method for detection of EDRF with RFL-6 rat lung fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1991;261:H598–H603. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.261.2.H598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirsch M, Korth HG, Stenert V, Sustmann R, de Groot H. The autoxidation of tetrahydrobiopterin revisited. Proof of superoxide formation from reaction of tetrahydrobiopterin with molecular oxygen. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:24481–24490. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211779200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuzkaya N, Weissmann N, Harrison DG, Dikalov S. Interactions of peroxynitrite, tetrahydrobiopterin, ascorbic acid, and thiols: implications for uncoupling endothelial nitric-oxide synthase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:22546–22554. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302227200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwon NS, Nathan CF, Stuehr DJ. Reduced biopterin as a cofactor in the generation of nitrogen oxides by murine macrophages. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:20496–20501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Landmesser U, Dikalov S, Price SR, McCann L, Fukai T, Holland SM, Mitch WE, Harrison DG. Oxidation of tetrahydrobiopterin leads to uncoupling of endothelial cell nitric oxide synthase in hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1201–1209. doi: 10.1172/JCI14172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laursen JB, Somers M, Kurz S, McCann L, Warnholtz A, Freeman BA, Tarpey M, Fukai T, Harrison DG. Endothelial regulation of vasomotion in apoE-deficient mice: implications for interactions between peroxynitrite and tetrahydrobiopterin. Circulation. 2001;103:1282–1288. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.9.1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li H, Brodsky S, Kumari S, Valiunas V, Brink P, Kaide J, Nasjletti A, Goligorsky MS. Paradoxical overexpression and translocation of connexin43 in homocysteine-treated endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H2124–H2133. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01028.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martasek P, Liu Q, Liu J, Roman LJ, Gross SS, Sessa WC, Masters BS. Characterization of bovine endothelial nitric oxide synthase expressed in E. coli. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;219:359–365. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McMillan K, Bredt DS, Hirsch DJ, Snyder SH, Clark JE, Masters BS. Cloned, expressed rat cerebellar nitric oxide synthase contains stoichio-metric amounts of heme, which binds carbon monoxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:11141–11145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.23.11141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meininger CJ, Marinos RS, Hatakeyama K, Martinez-Zaguilan R, Rojas JD, Kelly KA, Wu G. Impaired nitric oxide production in coronary endothelial cells of the spontaneously diabetic BB rat is due to tetrahydrobiopterin deficiency. Biochem J. 2000;349:353–356. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3490353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Milstien S, Katusic Z. Oxidation of tetrahydrobiopterin by peroxynitrite: implications for vascular endothelial function. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;263:681–684. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nishikawa T, Edelstein D, Du XL, Yamagishi S, Matsumura T, Kaneda Y, Yorek MA, Beebe D, Oates PJ, Hammes HP, Giardino I, Brownlee M. Normalizing mitochondrial superoxide production blocks three pathways of hyperglycaemic damage. Nature. 2000;404:787–790. doi: 10.1038/35008121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ono S, Ichikura T, Mochizuki H. The pathogenesis of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome and compensatory anti-inflammatory response syndrome following surgical stress. Nippon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 2003;104:499–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pieper GM, Siebeneich W, Moore-Hilton G, Roza AM. Reversal by l-arginine of a dysfunctional arginine/nitric oxide pathway in the endothelium of the genetic diabetic BB rat. Diabetologia. 1997;40:910–915. doi: 10.1007/s001250050767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pryor WA, Squadrito GL. The chemistry of peroxynitrite: a product from the reaction of nitric oxide with superoxide. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 1995;268:L699–L722. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1995.268.5.L699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sawabe K, Wakasugi KO, Hasegawa H. Tetrahydrobiopterin uptake in supplemental administration: elevation of tissue tetrahydrobiopterin in mice following uptake of the exogenously oxidized product 7,8-dihydrobiopterin and subsequent reduction by an anti-folate-sensitive process. J Pharmacol Sci. 2004;96:124–133. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fp0040280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schachinger V, Britten MB, Zeiher AM. Prognostic impact of coronary vasodilator dysfunction on adverse long-term outcome of coronary heart disease. Circulation. 2000;101:1899–1906. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.16.1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmidt TS, Alp NJ. Mechanisms for the role of tetrahydrobiopterin in endothelial function and vascular disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 2007;113:47–63. doi: 10.1042/CS20070108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schock BC, Van der Vliet A, Corbacho AM, Leonard SW, Finkelstein E, Valacchi G, Obermueller-Jevic U, Cross CE, Traber MG. Enhanced inflammatory responses in alpha-tocopherol transfer protein null mice. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;423:162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Setoguchi S, Hirooka Y, Eshima K, Shimokawa H, Takeshita A. Tetrahydrobiopterin improves impaired endothelium-dependent forearm vasodilation in patients with heart failure. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2002;39:363–368. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200203000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shinozaki K, Nishio Y, Okamura T, Yoshida Y, Maegawa H, Kojima H, Masada M, Toda N, Kikkawa R, Kashiwagi A. Oral administration of tetrahydrobiopterin prevents endothelial dysfunction and vascular oxidative stress in the aortas of insulin-resistant rats. Circ Res. 2000;87:566–573. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.7.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Srinivasan S, Hatley ME, Bolick DT, Palmer LA, Edelstein D, Brownlee M, Hedrick CC. Hyperglycaemia-induced superoxide production decreases eNOS expression via AP-1 activation in aortic endothelial cells. Diabetologia. 2004;47:1727–1734. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1525-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stroes E, Kastelein J, Cosentino F, Erkelens W, Wever R, Koomans H, Luscher T, Rabelink T. Tetrahydrobiopterin restores endothelial function in hypercholesterolemia. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:41–46. doi: 10.1172/JCI119131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tayeh MA, Marletta MA. Macrophage oxidation of l-arginine to nitric oxide, nitrite, and nitrate. Tetrahydrobiopterin is required as a cofactor. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:19654–19658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tiefenbacher CP, Chilian WM, Mitchell M, DeFily DV. Restoration of endothelium-dependent vasodilation after reperfusion injury by tetrahydrobiopterin. Circulation. 1996;94:1423–1429. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.6.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsutsui M, Milstien S, Katusic ZS. Effect of tetrahydrobiopterin on endothelial function in canine middle cerebral arteries. Circ Res. 1996;79:336–342. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.2.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vasquez-Vivar J, Duquaine D, Whitsett J, Kalyanaraman B, Rajagopalan S. Altered tetrahydrobiopterin metabolism in atherosclerosis: implications for use of oxidized tetrahydrobiopterin analogues and thiol antioxidants. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:1655–1661. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000029122.79665.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vasquez-Vivar J, Kalyanaraman B, Martasek P, Hogg N, Masters BS, Karoui H, Tordo P, Pritchard KA., Jr Superoxide generation by endothelial nitric oxide synthase: the influence of cofactors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9220–9225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vasquez-Vivar J, Martasek P, Whitsett J, Joseph J, Kalyanaraman B. The ratio between tetrahydrobiopterin and oxidized tetrahydrobiopterin analogues controls superoxide release from endothelial nitric oxide synthase: an EPR spin trapping study. Biochem J. 2002;362:733–739. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3620733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vasquez-Vivar J, Whitsett J, Martasek P, Hogg N, Kalyanaraman B. Reaction of tetrahydrobiopterin with superoxide: EPR-kinetic analysis and characterization of the pteridine radical. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;31:975–985. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00680-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Warnholtz A, Wendt M, August M, Munzel T. Clinical aspects of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Biochem Soc Symp. 2004:121–133. doi: 10.1042/bss0710121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weissman BA, Gross SS. Measurement of NO and NO Synthase. New York: Wiley; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Williams RL, Courtneidge SA, Wagner EF. Embryonic lethalities and endothelial tumors in chimeric mice expressing polyoma virus middle T oncogene. Cell. 1988;52:121–131. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90536-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wolff DJ, Datto GA, Samatovicz RA. The dual mode of inhibition of calmodulin-dependent nitric-oxide synthase by antifungal imidazole agents. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:9430–9436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yetik-Anacak G, Catravas JD. Nitric oxide and the endothelium: history and impact on cardiovascular disease. Vascul Pharmacol. 2006;45:268–276. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yoshida A, Pozdnyakov N, Dang L, Orselli SM, Reddy VN, Sitaramayya A. Nitric oxide synthesis in retinal photoreceptor cells. Vis Neurosci. 1995;12:493–500. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800008397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zanetti M, Sato J, Katusic ZS, O’Brien T. Gene transfer of endothelial nitric oxide synthase alters endothelium-dependent relaxations in aortas from diabetic rabbits. Diabetologia. 2000;43:340–347. doi: 10.1007/s001250050052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zou MH, Shi C, Cohen RA. Oxidation of the zinc-thiolate complex and uncoupling of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by peroxynitrite. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:817–826. doi: 10.1172/JCI14442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]