Abstract

Background

Racial disparities in survival from breast and prostate cancer are well established; however the roles of societal/socio-economic factors and innate/genetic factors in explaining the disparities remain unclear. One approach for evaluating the relative importance of societal and innate factors is to quantify how the magnitude of racial disparities changes according to the geographic scales at which data are aggregated. Disappearance of racial disparities for some levels of aggregation would suggest that modifiable factors not inherent at the individual level are responsible for the disparities.

Methods

The Michigan Cancer Surveillance Program compiled a dataset from 1985-2002 that included 124,218 breast cancer and 120,615 prostate cancer cases with 5-year survival rates of 78% and 75%, respectively. Absolute and relative differences in survival rates for whites and blacks were quantified across different geographic scales using statistics that adjust for population size to account for the small numbers problem common with minority populations.

Results

Whites experienced significantly higher survival rates for prostate and breast cancer compared with blacks throughout much of southern Michigan in analyses conducted using federal House legislative districts; however, in smaller geographic units (state House legislative districts, and community-defined neighborhoods), disparities diminished and virtually disappeared.

Conclusions

These results suggest that modifiable societal factors are responsible for apparent racial disparities in breast and prostate cancer survival observed at larger geographic scales. This research presents a novel strategy for taking advantage of inconsistencies across geographic scales to evaluate the relative importance of innate and societal-level factors in explaining racial disparities in cancer survival.

Keywords: neoplasms, geography, African Americans, Michigan, prostate, breast, survival

INTRODUCTION

The elimination of health disparities according to race, ethnicity, geographic location, and other factors is a goal of Healthy People 2010.1 Cancer mortality rates are one arena where racial, ethnic, and geographic disparities continue to persist, and prostate and breast cancer are of particular concern.2 On average in the US, 78% of black women survive five years after diagnosis of breast cancer, compared with 90% of white women.3 Black males prostate cancer incidence and mortality rates are twice those of whites, and black male survival following diagnosis is less than that of white males, although survival has improved dramatically in recent years.3

Despite considerable research to understand the causes of racial disparities in survival from breast and prostate cancers, the relative importance of innate and societal factors is still not clear. After accounting for socioeconomic factors, differences in tumor stage and grade, differences in treatment, mortality from comorbid conditions, or a combination of these factors, racial disparities in both breast and prostate cancer survival are reported to largely diminish and in some cases, vanish.4-13 A time trend analysis of racial disparity in breast cancer mortality indicates that calendar period rather than birth cohort effects are at play, suggesting that calendar-related changes (e.g., screening and treatment practices) are likely to account for the disparities.14 However, several studies have also shown strong persistence of disparities even after accounting for these potential explanatory factors. A meta-analysis of more than 10,000 black breast cancer cases and 40,000 white cases concluded that African American ethnicity is an independent predictor of a worse breast cancer outcome, and that biological determinants of disease therefore are plausible.15

Others note racial differences in breast density and corresponding differential performance of screening technology as a factor.16 Still others have argued for the presence of genetic differences,17 including tumor biology,18 as well as differences in diet19 when explaining racial disparities in survival from breast and prostate cancer.

One approach for improving our understanding of racial disparities in breast and prostate cancer mortality is to investigate how racial disparities change for different geographic scales. For example, we know that racial disparities in breast cancer survival are found in large geographic units (e.g., cities, counties, and states);20 however, we do not know if these disparities remain when the analysis is repeated using smaller geographic units. As the geographic scale of analysis decreases (e.g., from counties to neighborhoods), the population becomes more homogenous in terms of socioeconomic position (SEP) and other characteristics, such as proximity to screening facilities. Therefore, if racial disparities diminish at smaller geographic scales of analysis, one plausible hypothesis is that modifiable factors not innately part of an individual are responsible for the racial disparities. In this paper we investigate whether analyses of disparities across different geographic scales (federal House legislative districts, State House legislative districts, and community-defined neighborhoods) can provide insights into factors contributing to racial disparities in breast and prostate cancer survival. To our knowledge, this is the first examination of racial disparities in cancer survival at different geographic scales. Furthermore, the majority of work dealing with the science of scale21-23 concerns itself with inconsistency of results across different levels of scale;24-27 here, we are proposing a strategy which takes advantage of inconsistency across various scales to evaluate the hypothesis that modifiable, as opposed to genetic factors, are contributing to racial disparities in cancer mortality.

METHODS

Data

The Michigan Cancer Surveillance Program (MCSP) compiles cancer records for the state. MCSP is funded in part by the National Program of Cancer Registries within the Centers for Disease Control and is nationally certified by the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries at its highest level. Since 1985, external audits have found a completeness percentage of 95% or higher on the population-based data collected by the MCSP. From 1985 to 2002, 139,508 women were diagnosed with breast cancer, and 129,451 men with prostate cancer in Michigan.

For our analyses, approximately 92% of breast cancer cases and 91% of prostate cancer cases were successfully geocoded at residence at time of diagnosis under the oversight of the MCSP. The percentage of addresses successfully geocoded was greater for blacks than whites but did not differ within race or by year of diagnosis. Our geocoded dataset contained 97,414 breast cancer cases who survived 5+ years and 26,804 who did not survive 5+ years (78% 5-year survival); and 90,214 prostate cancer cases who survived 5+ years and 30,401 who did not survive 5+ years (75% 5-year survival). Among those who died from breast cancer, 15% were black, compared with 10% of those who survived (5+ years). Similarly, 18% of those who died from prostate cancer were black whereas 14% of those who survived (5+ years) were black.

Data were spatially aggregated into current federal House legislative districts, State House legislative districts, and neighborhoods within Michigan's major urban centers. The boundaries for urban neighborhoods were developed as a tool to monitor infant mortality through a collaborative process that involved community health leaders in each municipality to divide each city into regions with similarities in school education, access to health care and other factors thought relevant by the health leaders in each city. These neighborhood units were chosen because of their importance to local health planners and the likelihood that findings of public health significance within neighborhoods can be more easily used by local policy makers. Legislative districts were chosen because they are useful for communicating findings with legislators and provide a wide range of scale for comparison with neighborhoods. There are 15 federal House legislative districts in Michigan, 110 State House Districts, and 212 neighborhoods (as defined by community members) in the urban areas of Detroit, Pontiac, Flint, Saginaw, Jackson, Lansing, Battle Creek, Kalamazoo, Grand Rapids, Muskegon, and Benton Harbor. Data were temporally aggregated into nine-year moving windows, e.g., 1985-1993, 1986-1994, etc. Nine-year windows were selected so that the first and last groupings (1985-1993, 1994-2002) would contain entirely distinct datasets.

Analysis

Racial differences in survival of breast and prostate cancers were calculated within each geographic region vj. Survival rates were defined as the number of surviving cases divided by the total number of cases. Absolute racial disparities (rate differences)28 were calculated by subtracting the survival rate of whites zref(vj) from that of blacks ztarg(vj), while adjusting for the population-weighted average of survival rates using the following statistic:

where ntarg(vj) and nref(vj) denote the size of the target (black) and reference (white) populations, respectively, and z̄j is the population-weighted average of rates:

This adjustment for population size in the disparity statistic DispAbs is required to address the small numbers problem common in health geography.29 This problem arises when rates are unduly influenced by small changes in number of cases (e.g., 1/1 vs. 0/1), and is more common in minority populations where few cases are found in small geographic areas.

Relative disparity statistics (rate ratios) were also calculated using the following expression28 :

where z̄j is the population-weighted average of rates defined earlier. Both test statistics follow a standard normal distribution.

For both absolute and relative disparity statistics, statistical significance was determined using an alpha level of 0.05 and without multiple testing corrections as recommended by simulation studies.28 The statistical analysis and mapping were conducted using Space-Time Intelligent System (STIS, TerraSeer, Inc., Ann Arbor, MI). Results were highly consistent between the two statistics (97% agreement), therefore, only the disparities that were found significant for both absolute and relative measures are reported. There were insufficient numbers of blacks in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan to permit meaningful analysis in these areas; only results for the Lower Peninsula are presented.

RESULTS

Breast Cancer Survival

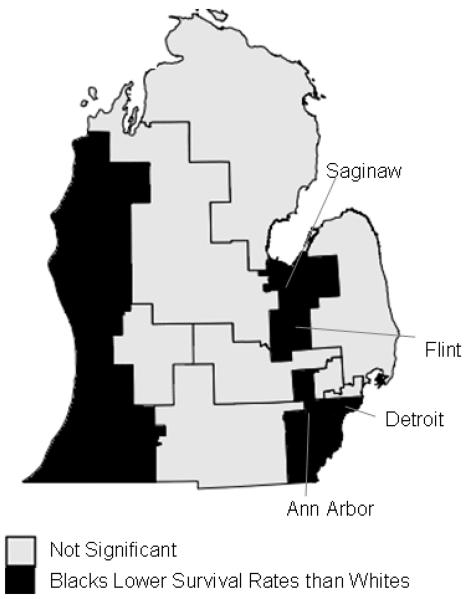

Regions and time periods with significant racial disparities in breast cancer survival are in Table 1. In Federal House Legislative Districts, eight of the fifteen regions (53%) displayed significantly higher survival rates for whites compared with blacks across the time periods; no regions displayed higher survival rates for blacks (Figure 1). Southern Detroit, Flint, Saginaw, and the southeastern and southwestern corners of Michigan showed significant disparities for the entire time period from 1985-2002. The Michigan Thumb Region, Ann Arbor and vicinity, and the northwestern suburbs of Detroit exhibited significant disparities for parts of the study period.

Table 1.

Regions of Significant Racial Disparities in Breast Cancer Survival Rates

| Region | Periods1 When Absolute and Relative Disparity Statistics are Both Significant |

White Survivors2 No. (%) |

Black Survivors2 No. (%) |

Population- Weighted Rate Ratio Statistic2 (Black Survival / White Survival) |

P-value2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Federal House Legislative Districts | |||||

| #13 (S Detroit) | 1985-1993,…, 1994-2002 | 1627 (73%) | 1308 (65%) | 0.87 | <0.001 |

| #9 (NW suburbs of Detroit) | 1989-1997 | 3566 (80%) | 114 (70%) | 0.88 | 0.010 |

| #14 (S Detroit) | 1985-1993,…, 1994-2002 | 1513 (73%) | 1583 (69%) | 0.93 | 0.002 |

| #11 (Ann Arbor + Vicinity) | 1985-1993,…,1992-2000 | 2990 (78%) | 46 (60%) | 0.77 | 0.008 |

| #5 (Flint and Saginaw) | 1985-1993,…, 1994-2002 | 2677 (78%) | 349 (68%) | 0.88 | <0.001 |

| #2 (MI Thumb Region) | 1988-1996,…, 1990-1998, 1992-2000 |

2644 (78%) | 81 (68%) | 0.87 | 0.038 |

| #6 (SW Corner of MI) | 1985-1993,…, 1994-2002 | 2734 (78%) | 164 (66%) | 0.83 | 0.001 |

| #15 (SE Corner of MI) | 1985-1993,…, 1994-2002 | 2483 (78%) | 220 (68%) | 0.89 | 0.007 |

| State House Legislative Districts | |||||

| #3 (Detroit) | 1992-2000,…,1994-2002 | 166 (58%) | 74 (71%) | 1.22 | 0.038 |

| #18 (S Detroit) | 1986-1994,…,1990-1998 | 422 (75%) | 16 (50%) | 0.66 | 0.024 |

| #14 (S Detroit) | 1986-1994, 1987-1995 | 493 (77%) | 32 (60%) | 0.78 | 0.031 |

| #16 (S Detroit) | 1985-1993 | 422 (70%) | 66 (59%) | 0.84 | 0.032 |

| #54 (W Detroit) | 1992-2000,…, 1994-2002 | 307 (85%) | 62 (73%) | 0.86 | 0.038 |

| #53 (Ann Arbor) | 1988-1996 | 387 (81%) | 20 (61%) | 0.74 | 0.037 |

| #49 (Flint Region) | 1989-1997,…, 1991-1999 | 437 (79%) | 52 (66%) | 0.83 | 0.031 |

| #60 (Battle Creek) | 1985-1993, 1987-1995,…, 1991-1999 |

349 (72%) | 39 (57%) | 0.80 | 0.037 |

| #78 (SW Corner of MI) | 1985-1993, 1987-1995,…, 1989-1997, 1991-1999, 1992- 2000, 1994-2002 |

426 (80%) | 10 (48%) | 0.61 | 0.037 |

| #79 (SW Corner of MI) | 1985-1993, 1987-1995, 1994- 2002 |

412 (77%) | 61 (65%) | 0.86 | 0.046 |

| Neighborhoods in Urban Centers | |||||

| Harmony Village (Detroit) | 1985-1993, 1986-1994 | 13 (93%) | 119 (65%) | 0.70 | <0.001 |

| Rosedale Park (Detroit) | 1985-1993 | 26 (50%) | 38 (75%) | 1.49 | 0.013 |

| Condon (Detroit) | 1986-1994, 1988-1996, 1990- 1998 |

21 (73%) | 24 (48%) | 0.66 | 0.027 |

| Lafayette (Detroit) | 1987-1995,…, 1989-1997 | 25 (83%) | 44 (58%) | 0.70 | 0.006 |

| Pershing (Detroit) | 1989-1997, 1990-1998 | 20 (55%) | 75 (76%) | 1.38 | 0.045 |

| Denby (Detroit) | 1992-2000,…, 1994-2002 | 36 (62%) | 59 (82%) | 1.34 | 0.013 |

Data were aggregated into moving 9-year windows; “…” refers to significant time windows in between the outer time windows.

Average number of survivors, rate ratio, and p-value over significant periods.

Figure 1.

Significant racial disparities in breast cancer survival in federal House legislative districts in Michigan, 1990-1998

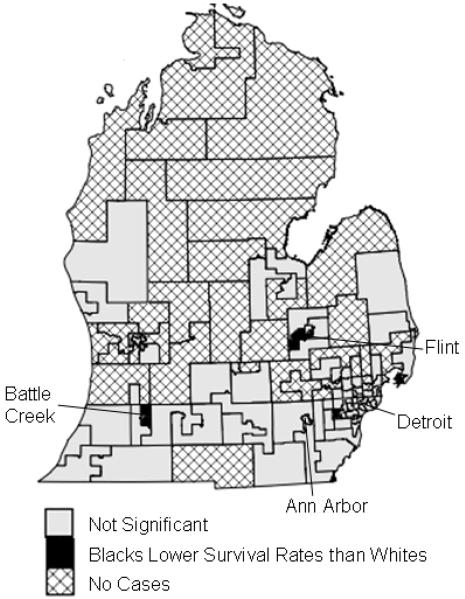

Using smaller geographic units, State House legislative districts, a smaller proportion of the regions had significant disparities (9%) (Figure 2). Nine regions exhibited better survival for whites, and one region had better survival for blacks. No region experienced significant disparities throughout the entire study period. Districts #18 in southern Detroit and #78 in the southwestern corner of the state were significant for the longest periods of time, five and seven years, respectively, showing better survival rates for whites.

Figure 2.

Significant racial disparities in breast cancer survival in State House legislative districts in Michigan, 1990-1998

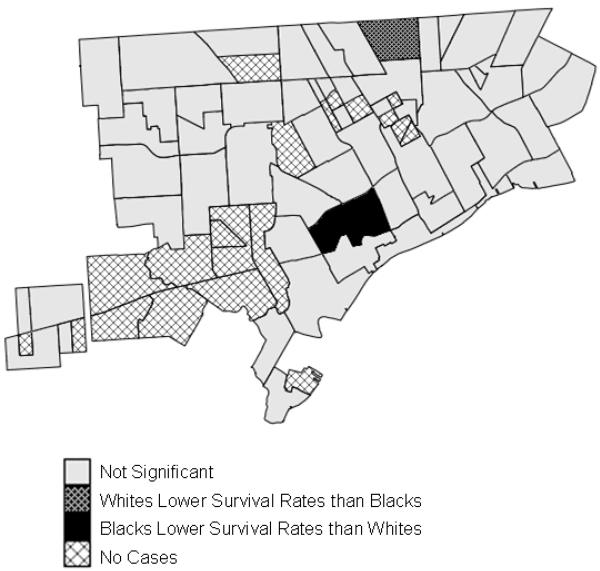

In the smallest geographic units examined, neighborhoods in urban centers, 3% of the regions showed significant racial disparities, and all of these were in Detroit (Figure 3). No region experienced significant disparities throughout the entire study period. Three areas had significantly greater survival for whites and three areas had greater survival for blacks. Overall, when the geographic scale of analysis decreased, fewer areas exhibited significant disparities and whites no longer experienced a clear health advantage.

Figure 3.

Significant racial disparities in breast cancer survival in neighborhoods in Detroit, Michigan, 1990-1998

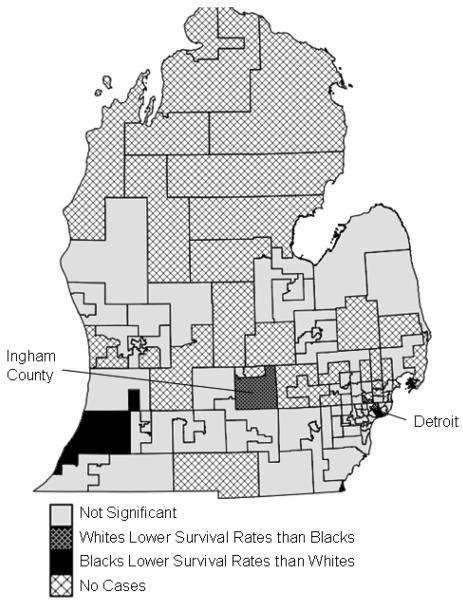

Prostate Cancer Survival

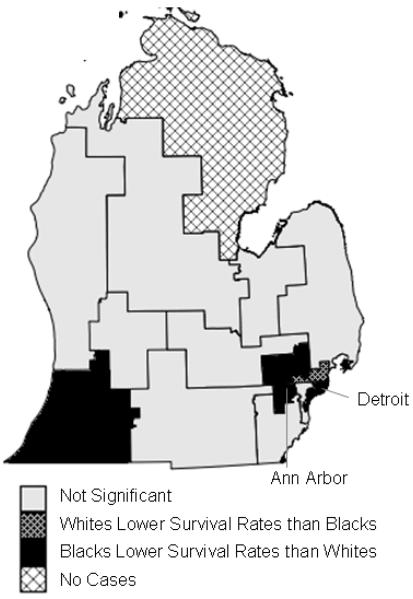

In federal House legislative districts (Figure 4), seven of the fifteen regions (47%) experienced significant racial disparities in prostate cancer survival (Table 2). Six regions showed better survival rates for whites, in areas surrounding Detroit, Ann Arbor, the Michigan Thumb region, and the southwestern corner of Michigan. One region in northern Detroit exhibited better survival rates for blacks. Two regions showed significant disparities for the entire study period from 1985-2002: southern Detroit and the southwestern corner of Michigan, both showing higher survival for whites.

Figure 4.

Significant racial disparities in prostate cancer survival in federal House legislative districts in Michigan, 1990-1998

Table 2.

Regions of Significant Racial Disparities in Prostate Cancer Survival Rates

| Region | Periods1 When Absolute and Relative Disparity Statistics are Both Significant |

White Survivors2 No. (%) |

Black Survivors2 No. (%) |

Population- Weighted Rate Ratio Statistic2 (Black Survival / White Survival) |

P-value2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Federal House Legislative Districts | |||||

| #13 (S Detroit) | 1985-1993,…, 1994-2002 | 1557 (68%) | 1987 (62%) | 0.91 | < 0.001 |

| #9 (NW suburbs of Detroit) | 1986-1994,…, 1994-2002 | 3408 (79%) | 185 (70%) | 0.88 | 0.005 |

| #14 (S Detroit) | 1985-1993,…, 1990-1998 | 1465 (67%) | 1795 (64%) | 0.95 | 0.011 |

| #12 (N Detroit) | 1989-1997,…, 1994-2002 | 3470 (75%) | 382 (82%) | 1.10 | <0.001 |

| #11 (Ann Arbor + Vicinity) | 1991-1999 | 3213 (78%) | 63 (67%) | 0.86 | 0.037 |

| #10 (MI Thumb Region) | 1985-1993,…, 1990-1998 | 1931 (70%) | 13 (45%) | 0.65 | 0.023 |

| #6 (SW Corner of MI) | 1985-1993,…, 1994-2002 | 2385 (74%) | 190 (64%) | 0.85 | <0.001 |

| State House Legislative Districts | |||||

| #6 (Detroit) | 1985-1993,…, 1988-1996 | 68 (68%) | 553 (56%) | 0.83 | 0.011 |

| #4 (Detroit) | 1988-1996,…, 1994-2002 | 123 (74%) | 582 (62%) | 0.83 | 0.003 |

| #2 (Detroit) | 1988-1996,…, 1994-2002 | 102 (59%) | 141 (75%) | 1.26 | 0.018 |

| #5 (Detroit) | 1991-1999, 1994-2002 | 115 (60%) | 399 (71%) | 1.18 | 0.012 |

| #10 (Detroit) | 1994-2002 | 128 (72%) | 198 (81%) | 1.13 | 0.038 |

| #27 (N Detroit) | 1989-1997,…, 1994-2002 | 385 (74%) | 53 (90%) | 1.23 | <0.001 |

| #67 (Ingham County) | 1989-1997,…, 1991-1999 | 223 (67%) | 21 (89%) | 1.32 | 0.002 |

| #80 (SW Corner of MI) | 1985-1993,…, 1987-1995, 1990-1998,…, 1993-2001 |

294 (72%) | 19 (495) | 0.68 | 0.023 |

| #79 (SW Corner of MI) | 1986-1994,…, 1991-1999 | 381 (72%) | 67 (60%) | 0.83 | 0.046 |

| Neighborhoods in Urban Centers | |||||

| Denby (Detroit) | 1985-1993, 1987-1995 | 47 (55%) | 22 (77%) | 1.47 | 0.022 |

| Connor (Detroit) | 1985-1993,…, 1988-1996 | 20 (47%) | 59 (70%) | 1.49 | 0.033 |

| University (Detroit) | 1985-1993,…, 1988-1996, 1990-1998, … 1994-2002 |

61 (87%) | 60 (54%) | 0.63 | <0.001 |

| Mack (Detroit) | 1987-1995,…1989-1997, 1993-2001 |

12 (77%) | 51 (49%) | 0.62 | 0.004 |

| Grant (Detroit) | 1989-1997,…, 1992-2000 | 9 (45%) | 34 (78%) | 1.71 | 0.038 |

| Cerveny (Detroit) | 1989-1997, 1990-1998 | 14 (94%) | 99 (67%) | 0.72 | <0.001 |

| Pershing (Detroit) | 1990-1998,…, 1992-2000 | 21 (54%) | 142 (77%) | 1.44 | 0.019 |

| Mt Olivet (Detroit) | 1992-2000,…, 1994-2002 | 24 (50%) | 66 (79%) | 1.58 | 0.004 |

| Pontiac Plant (Pontiac) | 1992-2000,…, 1994-2002 | 33 (55%) | 10 (85%) | 1.54 | 0.017 |

| Civic Park (Flint) | 1989-1997 | 30 (69%) | 24 (89%) | 1.30 | 0.032 |

| Garfield School (Flint) | 1985-1993, 1987-1995 | 9 (90%) | 23 (47%) | 0.53 | 0.001 |

Data were aggregated into moving 9-year windows; “…” refers to significant time windows in between the outer time windows.

Average number of survivors, rate ratio, and p-value over significant periods.

In State House legislative districts (Figure 5), nine regions (8%) exhibited significant racial disparities: five areas showed higher survival rates for blacks, and four areas higher survival for whites. Blacks experienced higher survival rates in parts of Detroit and Ingham County; whites exhibited higher survival rates in parts of Detroit and the southwestern corner of Michigan.

Figure 5.

Significant racial disparities in prostate cancer survival in State House legislative districts in Michigan, 1990-1998

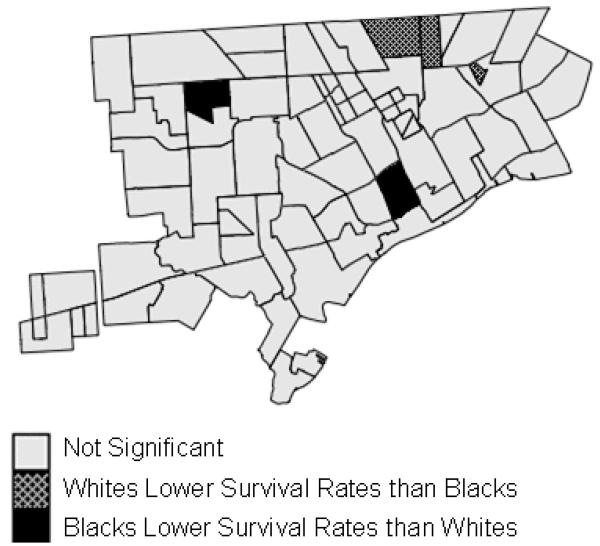

In neighborhoods in urban centers (Figure 6), 5% of the regions showed significant racial disparities. Whites and blacks both exhibited higher survival rates in different sections of Detroit and Flint. As was the case with breast cancer, fewer areas exhibited significant disparities and whites no longer experienced clear health benefits in smaller geographic units.

Figure 6.

Significant racial disparities in prostate cancer survival in neighborhoods in Detroit, Michigan, 1990-1998

DISCUSSION

Whites experienced significantly higher survival rates compared with blacks for prostate and breast cancer throughout much of southern Michigan in analyses conducted using federal House legislative districts; however, in smaller geographic units (state House legislative districts and urban neighborhoods), these disparities diminished and virtually disappeared. In smaller geographic units, the population at risk is more uniform with regard to modifiable risk factors, such as SEP and proximity to screening facilities. Therefore, when racial disparities diminish or vanish in small geographic areas, it suggests that modifiable factors are responsible for apparent racial disparities observed at larger geographic scales.

Conducting a spatial analysis across multiple aggregation levels is analogous to comparisons between unadjusted analyses (large geographic units) and analyses that adjust for key covariates and risk factors (small geographic units). This type of geographic analysis lends support to the existing literature suggesting that racial disparities in survival from prostate and breast cancer are attributable to modifiable risk factors, including socioeconomic factors, differences in tumor stage and grade, differences in treatment, mortality from comorbid conditions, or a combination of these factors.4-13 This type of geographic analysis cannot identify which among this set of explanatory factors is the most important; however, our findings suggest that genetic factors are not likely to play a large role in disparities of survival from prostate and breast cancer. Previous findings that evoked innate individual characteristics as responsible for observed disparities (e.g., genetic factors associated with race) may have failed to adjust for key modifiable factors associated with racial differences.

By comparing results across geographic scales to differentiate between modifiable risk factors and innate characteristics, the findings can also be interpreted to identify areas of racial disparities attributable to modifiable risk factors. For example, findings of higher survival rates for whites in eight of the fifteen federal House districts for breast cancer, and in six federal House districts for prostate cancer may suggest that factors associated with access to and quality of care and screening/diagnostic resources favored whites, compared with blacks, in these regions of Michigan. Specifically, whites had advantages in parts of Detroit, Ann Arbor, the Michigan Thumb region, and the southwestern corner of the state for survival from both cancers. Similarly, blacks experienced advantages in northern Detroit, compared to whites, for prostate cancer survival, suggesting modifiable factors in this region contribute to these disparities. In particular, survival rates were better for blacks compared with whites from both prostate and breast cancer in the Detroit neighborhoods of Denby and Pershing, albeit not during overlapping years. These two neighborhoods were previously used for recruiting disadvantaged whites from regions of persistent poverty30, suggesting that SEP may help explain the few disparities that remain even in the neighborhood-level analysis.

A major strength of this study is that the numerator (surviving cases) and denominator (all cases) come from the same cancer registry dataset, precluding the need for census-derived estimates of population at risk. Failure to account for error in census-derived denominators has confounded studies for decades, with geographic analyses only the latest victim.31-33 For example, in the 1990s a series of health indicators suggested unusually poor health among blacks and unusual differences in disease rates between blacks and whites in Atlanta; however, it was later discovered that the population of blacks was underestimated by approximately 18% and the population of whites overestimated by about 10%, meaning that Atlanta's health did not markedly differ from that of the nation as a whole.34

This study focused on disparities in cancer survival only between whites and blacks because there were too few individuals of other races or ethnicities in Michigan to calculate reliable estimates of cancer survival. The approach, however, could be adopted to compare disparities across more than two racial/ethnic groupings. In States with sufficient populations of Hispanics, for example, a similar approach could be conducted using multiple two-way comparisons of non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks, and Hispanics.

Notwithstanding the strengths of this work, this study does have limitations. Seven percent of breast cancers and nine percent of prostate cancers were not successfully geocoded with cases for whites less likely to be geocoded than blacks. For breast cancer, 7.8 percent of whites were not geocoded compared to 3.0 percent of blacks while for prostate cancer, these percentages were 9.2 and 4.3 percent, respectively. This is consistent with proportionately lower populations of blacks in rural areas of the state that do not geocode as completely. Cases successfully geocoded did not differ by survival status overall nor within race. Geocoding accuracy diminished in northern Michigan, including the Upper Peninsula, but there are so few blacks in the Upper Peninsula as to preclude meaningful analysis in these areas. As geographic scale becomes smaller and population size decreases, chances of detecting significant disparities also decrease. For this reason, it is not surprising that fewer areas are significant at smaller geographic scales. However, significant disparities in favor of both whites and blacks at the smallest geographic scale suggest that widespread racial disparities were not evident. Temporal trends were not evident in the significance of disparities; had this not been the case, differences between absolute and relative disparity statistics would have been worthy of scrutinization.35 While the disparity statistics allow us to quantify and visually display racial disparities on maps, they do not permit us to specifically identify those determinants of health that may warrant closer scrutiny at the local level, including but not limited to socio-economic status, variations in access to and quality of medical care and health insurance, cultural influences, and racial/ethnic sub-groupings. In particular, this work did not investigate how results may vary across subpopulations of whites and blacks based on country of origin prior to migration to the US. If individual-level information on health care access, use of screening clinics, SEP, racial/ethnic sub-grouping, etc., were routinely collected by cancer registries, then these factors could be examined to better understand the relative contributions of these determinants of health. In addition, future studies could investigate the use of GIS and census data to provide proxies for these individual-level measures.

This work represents a cross-disciplinary collaboration between health geographers, spatial statisticians, epidemiologists, and the Michigan Cancer Surveillance Program (which includes the state cancer registry) seeking to develop a protocol for the spatial analysis of racial disparities making use of cancer registry data. There was special interest from cancer registry staff to investigate racial disparities in small geographic areas to help identify models to guide the selection of targeted areas for improvement. Our findings indicate that racial disparities in survival from breast and prostate cancer are attributable to modifiable factors in the local environment. We highlight regions where disparities in modifiable societal factors are contributing to racial disparities in survival from these cancers. Collaborating in this research-practice partnership enabled us to identify and illustrate a practical approach for detecting racial disparities in cancer registry data. The approach illustrated here, of comparing results across geographic scales to differentiate between innate and modifiable characteristics responsible for racial disparities, should be applied more broadly.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by CDC grant 5U58DP000812 and NCI grant 2R44CA110281-02. The perspectives are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official positions of the funding agencies.

REFERENCES

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services . Healthy People 2010: understanding and improving health. US Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Clegg LX, Ward E, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2001, with a special feature regarding survival. Cancer. 2004;101:3–27. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ries LAG, Melbert D, Krapcho M, et al., editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2005. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: Available from URL: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2005/ [accessed April 23, 2008] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bach PB, Schrag D, Brawley OW, Galaznik A, Yakren S, Begg CB. Survival of blacks and whites after a cancer diagnosis. JAMA. 2002;287:2106–2113. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.16.2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chu KC, Miller BA, Springfield SA. Measures of racial/ethnic health disparities in cancer mortality rates and the influence of socioeconomic status. Journal Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99:1092–1104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Curtis E, Quale C, Haggstrom D, Smith-Bindman R. Racial and ethnic differences in breast cancer survival: How much is explained by screening, tumor severity, biology, treatment, comorbidities, and demographics? Cancer. 2007;112:171–80. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Du W, Simon MS. Racial disparities in treatment and survival of women with stage I-III breast cancer at a large academic medical center in metropolitan Detroit. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;91:243–248. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-0324-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LI CI. Racial and ethnic disparities in breast cancer stage, treatment and survival in the United States. Ethn Dis. 2005;15:5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maloney N, Koch M, Erb D, Schneider H, Goffman T, Elkins D, Laronga C. Impact of race on breast cancer in lower socioeconomic status women. Breast J. 2006;12:58–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2006.00184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robbins AS, Yin D, Parikh-Patel A. Differences in prognostic factors and survival among white men and black men with prostate cancer, California, 1995-2004. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166:71–78. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simon MS, Banerjee M, Crossley-May H, Vigneau FD, Noone A-M, Schwartz K. Racial differences in breast cancer survival in the Detroit metropolitan area. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;97:149–155. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9103-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tewari A, Horninger W, Pelzer AE, et al. Factors contributing to the racial differences in prostate cancer mortality. BJU Int. 2005;96:1247–1252. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Underwood W, DeMonner S, Ubel P, Fagerlin A, Sanda MG, Wei JT. Racial/ethnic disparities in the treatment of localized/regional prostate cancer. J Urol. 2004;171:1504–1507. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000118907.64125.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jatoi I, Anderson WF, Rao SR, Devesa SS. Breast cancer trends among black and white women in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7836–7841. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.0421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newman LA, Mason J, Cote D, et al. African-American ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and breast cancer survival. Cancer. 2002;2002;94:2844–2854. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.del Carmen MG, Hughes KS, Halpern E, et al. Racial differences in mammographic breast density. Cancer. 2003;98:590–596. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White RWD, Deitch AD, Jackson AG, et al. Racial differences in clinically localized prostate cancers of black and white men. J Urol. 1998;159:1979–1983. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)63216-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amend K, Hicks D, Ambrosone CB. Breast Cancer in African-American Women: Differences in Tumor Biology from European-American Women. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8327–8330. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferdowsian HR, Barnard ND. The role of diet in breast and prostate cancer survival. Ethn Dis. 2007;17:S18–S22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grann V, Troxel AB, Zojwalla N, Hershman D, Glied SA, Jacobson JS. Regional and racial disparities in breast cancer-specific mortality. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:337–347. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goodchild MF, Quattrochi DA. Scale, multiscaling, remote sensing, and GIS. In: Quattrochi DA, Goodchild MF, editors. Scale in Remote Sensing and GIS. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 1997. pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marceau DJ. The scale issue in social and natural sciences. Can J Remote Sens. 1999;25:347–356. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meentemeyer V, Box EO. Scale effects in landscape studies. In: Turner MG, editor. Landscape Heterogeneity and Disturbance. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1987. pp. 15–34. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Rehkopf DH, Subramaniam SV. Race/Ethnicity, and monitoring socioeconomic gradients in health: a comparison of area-based socioeconomic measures—the Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1655–1671. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.10.1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schuurman N, Bell N, Dunn JR, Oliver L. Deprivation indices, population health and geography: an evaluation of the spatial effectiveness of indices at multiple scales. J Urban Health. 2007;84:591–603. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9193-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soobader M, LeClere FB. Aggregation and the measurement of income inequality: effects on morbidity. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48:733–744. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00401-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soobader M, LeClere FB, Hadden W, Maury B. Using aggregate geographic data to proxy individual socioeconomic status: does size matter? Am J Public Health. 2001;91:632–636. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.4.632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goovaerts P, Meliker J, Jacquez GM. A comparative analysis of aspatial statistics for detecting racial disparities in cancer mortality rates. Int J Health Geogr. 2007;6:32. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-6-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Waller LA, Gotway CA. Applied Spatial Statistics for Public Health Data. John Wiley and Sons; New Jersey: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Geronimus AT, Bound J, Waidmann TA, Hillemeier MM, Burns PB. Excess mortality among blacks and whites in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1552–1558. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199611213352102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boscoe FP, Miller BA. Population Estimation Error and Its Impact on 1991–1999 Cancer Rates. Prof Geogr. 2004;56:516–529. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Freedman D, Wachter K. Heterogeneity and Census Adjustment for the Intercensal Base. Stat Sci. 1994;9:476–485. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kennedy S. The small number problem and the accuracy of spatial databases. In: Goodchild M, Gopal S, editors. Accuracy of Spatial Databases. Taylor & Francis Ltd; London: 1989. pp. 187–196. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anonymous Faulty estimates led NCI to overstate black-white cancer disparity in Atlanta. The Cancer Letter. 2002 Sep 20;28 Available at: http://www.cancerletter.com. [Last accessed: July 21, 2008.]

- 35.Harper S, Lynch J, Meersman SC, Breen N, Davis WW, Reichman ME. An overview of methods for monitoring social disparities in cancer with an example using trends in lung cancer incidence by area-socioeconomic position and race-ethnicity, 1992–2004. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:889–899. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]