Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To determine whether a simple, nonsurgical treatment for congenital ear abnormalities (lop-ear, Stahl’s ear, protruding ear, cryptotia) improved the appearance of ear abnormalities in newborns at six weeks of age.

METHODS

This is a descriptive case series. All newborns with identified abnormalities were referred by their family physician to one paediatrician (WGS) in a small level 2 perinatal centre. The ears were waxed and taped in a standard manner within 10 days of birth. Pictures were taken before taping and at the end of taping (one month). All patients and pictures were assessed by one plastic surgeon (JWT) at six weeks of age and scored using a standard scoring system. A telephone survey of the nontreatment group was conducted.

RESULTS

The total number of ears assessed was 90. Of this total, 69 ears were taped and fully evaluated in the study (77%). The refusal rate was 23%. In the treatment group, 59% had lop-ear, 19% had Stahl’s ear, 17% had protruding ear and 3% had cryptotia. Overall correction (excellent/improved) for the treatment group was 90% (100% for lop-ear, 100% for Stahl’s ear, 67% for protruding ear and 0% for cryptotia). In the nontreatment (refusal) group, 67% of the ears failed to correct spontaneously. No complications were recognized by the authors or parents by six weeks. The percentage of newborns in one year in the perinatal centre with recognized ear abnormalities was 6% (90 of 1600).

CONCLUSIONS

A simple, nonsurgical treatment in a Caucasian population appeared to be very effective in correcting congenital ear abnormalities with no complications and high patient/parent satisfaction.

Keywords: Abnormality, Auricle, Congenital, Ear

Abstract

OBJECTIF

Déterminer si un traitement non chirurgical simple des anomalies congénitales de l’oreille (oreille en anse, oreille de Stahl, oreille décollée, cryptotie) améliore l’apparence des anomalies de l’oreille chez les nouveau-nés à six semaines.

MÉTHODOLOGIE

Il s’agit d’une série descriptive de cas. Tous les nouveau-nés ayant une anomalie diagnostiquée ont été aiguillés par leur médecin de famille vers un pédiatre (WGS) d’un petit centre périnatal de soins secondaires. Les oreilles ont été cirées et fixées à l’aide de ruban adhésif de manière standard dans les dix jours suivant la nais-sance. Des photos ont été prises avant l’installation de l’adhésif et à la fin du traitement (un mois). Tous les patients et toutes les photos ont été évalués par un plasticien (JWT) lorsque les nouveau-nés avaient six semaines et ont été classés selon un système de classement standard. Une enquête téléphonique auprès du groupe non traité a été exécutée.

RÉSULTATS

Quatre-vingt-dix oreilles ont été évaluées au total. De ce nombre, 69 oreilles ont été fixées à l’aide d’adhésif et ont fait l’objet d’une évaluation complète pendant l’étude (77 %). Le taux de refus était de 23 %. Au sein du groupe traité, 59 % avait des oreilles en anse, 19 %, des oreilles de Stahl, 17 %, des oreilles décollées et 3 %, une cryptotie. La correction globale (excellente, améliorée) du groupe de traitement était de 90 % (100 % dans le cas des oreilles en anse et des oreilles de Stahl, 67 % dans celui des oreilles décollées et 0 % dans celui de la cryptotie). Au sein du groupe non traité (ayant refusé le traitement), 67 % des oreilles ne se sont pas corrigées spon-tanément. Aucune complication n’avait été observée par les auteurs ou les parents à l’âge de six semaines. En un an, le pourcentage de nouveau-nés présentant une anomalie dépistée de l’oreille au sein du centre périnatal était de 6 % (90 sur 1 600).

CONCLUSIONS

Un traitement non chirurgical simple auprès de la population blanche semble très efficace pour corriger les anomalies congénitales de l’oreille, sans complication. Il s’associe à une satisfaction élevée des patients et des parents.

The concept of correcting congenital ear malformations in the newborn using a nonsurgical method has been presented in the world literature with good success (1–3). A MEDLINE review (1960–2002; key words ‘congenital ear/auricular abnormality’, ‘lop’, ‘Stahl’s’, ‘protruding’, ‘cryptotia’) revealed few North American studies, specifically, one review article (4), one case series of four cases (5) and one small study of 19 patients (6), all of which recommended different materials and techniques to correct the abnormalities. The remainder of the studies were predominately of Japanese origin. A recent report from Denmark looking at older children aged three months to five years had a termination rate of 37%, a complication rate of 30% and a mean treatment length of 5.5 months. In the study, good to fair correction was achieved in 86% of ears (7). After a review of the literature, a method was adopted and found to be successful over the next eight years. There appeared to be a high degree of patient/parent satisfaction with this method and it involved a small amount of intervention. We were impressed with the desire of our patients’ parents to correct these abnormalities and recognized the lengths that some adult patients go to improve their cosmetic appearance (8). We were also impressed with the emotional and psychological effects that these ear abnormalities can have on children, considering the large catalogue of derogatory names (bat, cat, clown, cup, devils, donkey, Dumbo, droopy, etc) used to describe these conditions (9–11). Intervention in this manner has some support in the paediatric literature (4,5,12–14). Taping and other modalities have been used as both initial therapy and in conjunction with surgery (15–18). There are recognized complications from the surgical approach to this problem, including pain, hematoma, malposition of the pinna, infection and scarring (19). Some physicians have extended their management to children beyond the newborn period but have found this to be less effective (6,20,21). Although the literature indicates success in children up to 14 years of age, we have previously reviewed this method in cases of protruding ears beyond the newborn period (22), and have found that children do not tolerate the taping or splint (dental wax or OTOFORM-K/c [Dreve-Otoplastik GMBH, Germany]) after three years of age. This finding has made it imperative to make sure that if we are to intervene in a nonsurgical manner, it should occur in the newborn period. The objective of the present study was to determine the effectiveness of a new and simple intervention strategy in the newborn age range compared with the natural history course as documented in the literature (2,21,23).

METHODS

Setting

Orillia is a small community of 30,000 people in central Ontario. The Orillia Soldiers’ Memorial Hospital serves the town and surrounding communities for primary care, while the Regional Paediatric and Perinatal unit serves five other community hospitals within a large geographical region with a population of approximately 150,000. The average yearly birth rate in the unit is 800 births/year with 50% of these being high-risk births. The average number of births in the region is 2500 births/year, with low-risk deliveries occurring in the community hospitals.

Participants

All newborns born at the Orillia Regional Perinatal Centre were possible candidates for the trial. They were selected for the trial after referral by their primary care physician after an abnormality of the external ear was identified.

Design

All patients born in the Orillia Soldiers’ Memorial Hospital from October 7, 2002, to October 8, 2003, who were identified by their family physician as having lop-ear, Stahl’s ear, protruding ear or cryptotia were referred to one of the authors (WGS). On confirmation of the congenital abnormality, the patient was enrolled in the study after appropriate consent was obtained. Approval for the study was received from the Ethics Committee of the Orillia Soldiers’ Memorial Hospital.

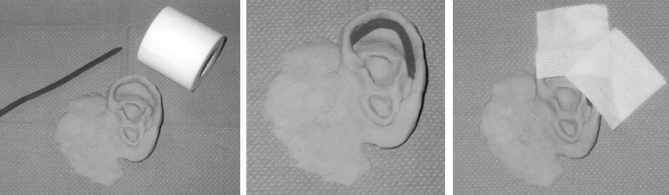

An initial photograph was taken by one of the authors (WGS) within 10 days of life and before any intervention. Wax (Utility Wax Rods Round-KERR, Sybron, USA) was placed within the outer helix of the ear and tape (Medipore, 3M, USA) was applied to the ear to hold it in place (Figure 1). If excessive hair was present around the ear, it was removed by shaving two inches around the ear. The hair was saved and given to the mother as the patient’s first haircut. Based on the authors’ experiences over the past eight years, the tape was left in place for one month and removed by the parent just before the one-month follow-up. At the follow-up visit, a second photograph was taken. Both the pretreatment and one-month post-treatment photographs were labelled with the patient’s clinical patient information number, left or right status, and pre- or post-treatment status. All pictures and patients were then sent to one of the authors (JWT) to evaluate their outcome at six weeks of age. The outcomes were rated as per the literature as excellent (the auricle was delicately corrected into a desirable form and satisfied the patient/parent), improved (the auricle was corrected into a rough form that did not attain a desirable shape and an irregular form still remained; however, its improvement satisfied the patient/parent), recurrent (the auricle was initially corrected but the deformity recurred), not improved (the auricle was not corrected to the desired form and the result did not satisfy the patient/parent) or gave up (the patient/parent gave up before treatment could be completed) (20).

Figure 1.

Nonsurgical method used to correct congenital ear malformations in the newborn period. Wax (Utility Wax Rods Round-KERR, Sybron, USA) was placed within the outer helix of the ear, and tape (Medipore, 3M, USA) was applied to the ear to hold it in place

Complications were noted and reported by the treating author, evaluating author and parents.

RESULTS

The number of newborns born at the centre during the study was 800 (1600 ears). The total number of ears detected as abnormal by the nurses and primary family physicians was 90. This represents a rate of congenital ear malformation of 6% (90 of 1600). Of this group, 21 ears were not taped (refusal rate of 23%) because the parents did not wish to participate in the study. The only reason cited for refusing participation was a lack of interest in changing the cosmetic appearance of the ear. One parent who originally agreed to participate changed her mind regarding the trial and withdrew after two weeks. This patient’s ear was labelled as ‘gave up’. The study, therefore, treated 69 ears (77%).

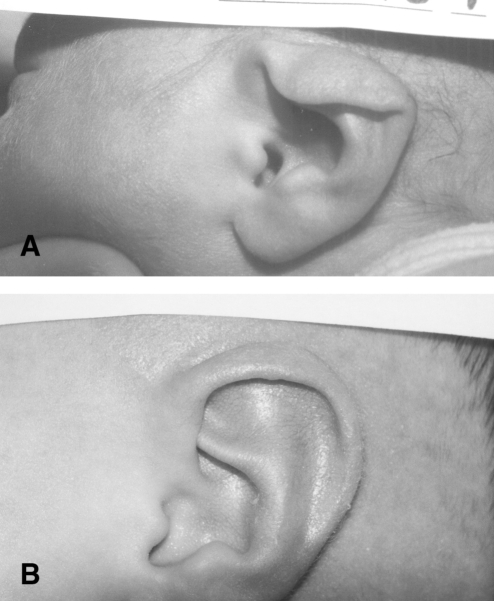

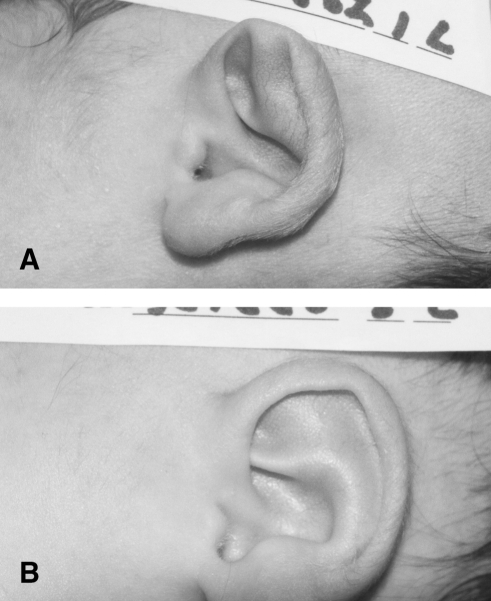

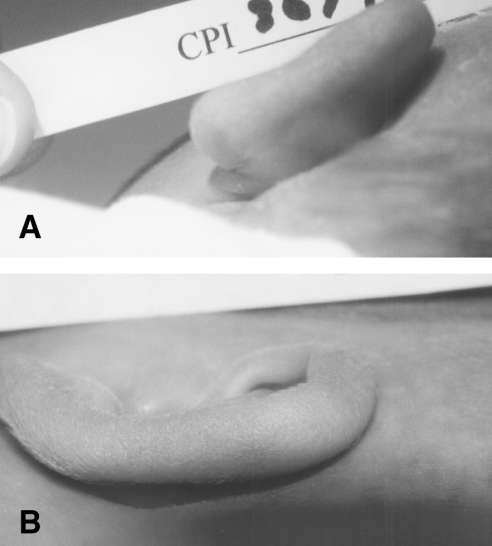

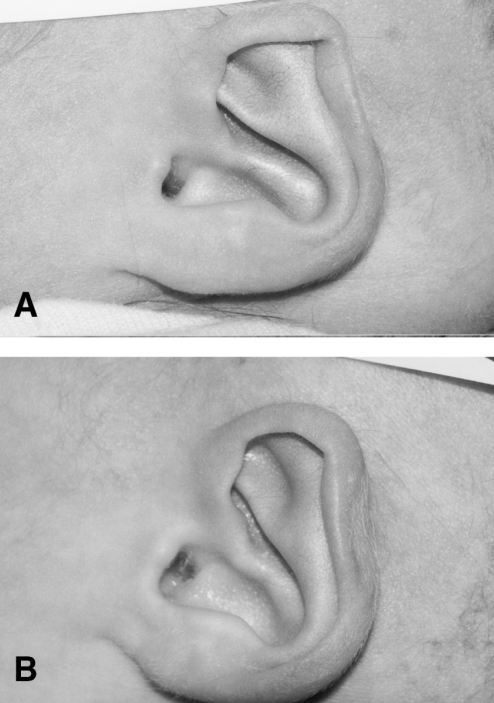

The overall correction rate of ears to excellent or improved was 90%. The breakdown of this group by diagnosis was as follows: 59% lop-ear, 19% Stahl’s ear, 17% protruding ear and 3% cryptotia. Using the same criteria (excellent/improved), the following subgroup analysis revealed correction rates of 100% for lop-ear (Figure 2), 100% for Stahl’s ear (Figure 3), 67% for protruding ear (Figure 4) and 0% for cryptotia (Figure 5) (Table 1). There were no complications (bruising, infection or general trauma to the ear) reported by parents, the author taping the ears or the surgeon evaluator at the six-week mark. All parents were asked to call back if the ear returned to the pretreatment state; none did.

Figure 2.

Patient with lop-ear (A) pre- and (B) postcorrection

Figure 3.

Patient with Stahl’s ear (A) pre- and (B) postcorrection

Figure 4.

Patient with protruding ear (A) pre- and (B) postcorrection

Figure 5.

Patient with cryptotia (A) pre- and (B) postcorrection

TABLE 1.

Congenital ear abnormalities

| Abnormality (n [%]) | Excellent, n (%) | Improved, n (%) | Not improved, n (%) | Gave up, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (69 [100]) | 50 (72) | 12 (17) | - | 1 (1) |

| Lop-ear (41 [59]) | 34 (83) | 7 (17) | - | 1 (0.02) |

| Stahl’s ear (13 [19]) | 11 (85) | 2 (15) | - | |

| Protruding ear (12 [17]) | 5 (42) | 3 (25) | 4 (33) | |

| Cryptotia (2 [3]) | - | - | 2 (100) |

Parents in the nontreatment (refusal) group (21 ears) were contacted by telephone at the end of the study. A large proportion (43% [nine ears]) was lost to follow-up (Table 2). Of the remaining group (13 ears), 33% showed spontaneous improvement according to parental observation. Subgroup analysis of the spontaneous improvement group indicated that 29% (two of seven ears) were lop-ears and 40% (two of five ears) were Stahl’s ears. Of the remaining eight ears in this untreated group, 67% had not improved (71% lop-ears and 60% Stahl’s ears).

TABLE 2.

Nontreatment (refusals)

| Abnormality (n [%]) | Excellent, n (%) | Improved, n (%) | Not improved, n (%) | Lost to follow-up, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (21 [100]) | - | 4 (33) | 8 (67) | 9 (43) |

| Lop-ear (14 [67]) | - | 2 (29) | 5 (71) | 7 (50) |

| Stahl’s ear (7 [33]) | - | 2 (40) | 3 (60) | 2 (29) |

| Protruding ear (0 [0]) | - | - | - | - |

| Cryptotia (0 [0]) | - | - | - | - |

DISCUSSION

The natural history of congenital ear deformities has been extensively reviewed in the world literature (mainly Japanese). In a large review (2) of 1000 auricles of babies in Japan during the 1980s, 55.2% were found to be abnormal at birth (lop-ear, Stahl’s ear, protruding ear and other). Without intervention, at one month of age, 31.7% remained abnormal. By one year of age, 16.1% of the newborns continued to show significant abnormalities in ear structure. Furthermore, the predominate abnormality was lop-ear (38%), with Stahl’s ear (8.7%) being much less frequent. There are no similar large studies in a Caucasian population.

The results of the present study indicate a much lower rate of congenital ear abnormality (6% versus 55%) in newborns in this predominately Caucasian North American population. It is possible that some ears were overlooked; however, this is a small perinatal unit and the numbers missed would be small. The proportion of abnormalities (lop-ear, Stahl’s ear, protruding ear and cryptotia) was similar to that in the Japanese literature. The intervention technique was very user-friendly, requiring minimal materials and time. There were no complications with this procedure in the newborn. The correction rate for the two most common abnormalities (lop-ear and Stahl’s ear) was 100%. The failures occurred in two distinct groups. Protruding ears failed to correct in 33% of cases (four ears). Having reported on this technique in protruding ears in the older infant (22), this is of interest, and not our experience in general. Analysis of the failed cases revealed that these four ears had both protruding and cup abnormalities. The only other failed group was that of pure cryptotia. In this group, all (100% or two ears) failed to respond to the wax and taping. The nature of this abnormality makes it unlikely to respond to molding in this fashion. The literature suggests that there is no spontaneous correction of this abnormality.

The natural history of spontaneous correction in the Japanese studies is significant, with an initial rate of abnormality of 55% and a one-year rate of abnormality of 16.9% (hence, an improvement of almost 70%). However, it is impossible to predict which ear will improve and which will not. Follow-up of our nontreatment group indicated a high degree of unchanged abnormality (67%) based on parental observation.

Treatment after the newborn period takes much longer and, according to the literature, may result in complications during treatment, with a high dropout rate.

The present study is limited by the lack of a control group and long-term outcome studies. Comparison with the Japanese literature may be misleading given the large discrepancies of incidence in these two populations. There are no comparable epidemiological studies in the Caucasian population. The study was very short-term; however, there is an indication in the literature that once correction is achieved, there is a very low recurrence rate (7).

CONCLUSIONS

A safe, user-friendly, nonsurgical intervention for congenital ear abnormalities was found to be highly effective and received high levels of parent satisfaction. Specific ear abnormalities (lop-ear and Stahl’s ear) were uniformly corrected with this technique.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Lori Fotherby, Research Coordinator, Orillia Soldiers Memorial Hospital, Orillia, Ontario, for her assistance. Special thanks to the nurses and family doctors for participating in and supporting the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Matsuo K, Hirose T, Tomono T, et al. Nonsurgical correction of congenital auricular deformities in the early neonate: A preliminary report. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;73:38–51. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198401000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matsuo K, Hayashi R, Kiyono M, Hirose T, Netsu Y. Nonsurgical correction of congenital auricular deformities. Clin Plast Surg. 1990;17:383–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurozumi N, Ono S, Ishida H. Non-surgical correction of a congenital lop ear deformity by splinting with Reston foam. Br J Plast Surg. 1982;35:181–2. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(82)90160-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Furnas DW. Nonsurgical treatment of auricular deformities in neonates and infants. Pediatr Ann. 1999;28:387–90. doi: 10.3928/0090-4481-19990601-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown FE, Colen LB, Addante RR, Graham JM., Jr Correction of congenital auricular deformities by splinting in the neonatal period. Pediatrics. 1986;78:406–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tan ST, Abramson DL, MacDonald DM, Mulliken JB. Molding therapy for infants with deformational auricular anomalies. Ann Plast Surg. 1997;38:263–8. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199703000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sorribes MM, Tos M. Nonsurgical treatment of prominent ears with the Auri method. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:1369–76. doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.12.1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perez-Barrero P, Rodrigo J, Elena E, Marques MD. Auto-otoplasty using cyanoacrylate. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:2157–8. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200112000-00062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rogers BO. Microtic, lop, cup and protruding ears: Four directly inheritable deformities? Plast Reconstr Surg. 1968;41:208–31. doi: 10.1097/00006534-196803000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stark RB, Saunders DE. Natural appearance restored to the unduly prominent ear. Br J Plast Surg. 1962;15:385–97. doi: 10.1016/s0007-1226(62)80063-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Macgregor FC. Ear deformities: Social and psychological implications. Clin Plast Surg. 1978;5:347–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spinelli HM. Congenital ear deformities. Pediatr Rev. 1993;14:473–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tan ST, Shibu M, Gault DT. A splint for correction of congenital ear deformities. Br J Plast Surg. 1994;47:575–8. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(94)90144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merlob P, Eshel Y, Mor N. Splinting therapy for congenital auricular deformities with the use of soft material. J Perinatol. 1995;15:293–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohmori S, Matsumoto K. Treatment of cryptotia, using Teflon string. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1972;49:33–7. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197201000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muraoka M, Nakai Y, Ohashi Y, Sasaki T, Maruoka K, Furukawa M. Tape attachment therapy for correction of congenital malformations of the auricle: Clinical and experimental studies. Laryngoscope. 1985;95:167–76. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198502000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirose T, Tomono T, Matsuo K, et al. Cryptotia: Our classification and treatment. Br J Plast Surg. 1985;38:352–60. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(85)90241-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan ST, Gault DT. When do ears become prominent? Br J Plast Surg. 1994;47:573–4. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(94)90143-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Furnas DW. Complications of surgery of the external ear. Clin Plast Surg. 1990;17:305–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yotsuyanagi T, Yokoi K, Urushidate S, Sawada Y. Nonsurgical correction of congenital auricular deformities in children older than early neonates. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;101:907–14. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199804040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yotsuyanagi T, Yokoi K, Sawada Y. Nonsurgical treatment of various auricular deformities. Clin Plast Surg. 2002;29:327–2. ix. doi: 10.1016/s0094-1298(01)00011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith WG, Toye JW, Smith RW. Nonsurgical treatment of protruding ears: A case report and review of literature. Can J Plast Surg. 2003;11:87–9. doi: 10.1177/229255030301100202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirose T, Satoh R, Matsuo K, et al. Studies on the shape of the auricle –changes of the shape of the auricle after birth. In: Maneksha RJ, editor. Transactions of the 9th International Congress of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery; New Delhi: Tata McGraw Hill; 1983. [Google Scholar]