Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis (AIT) develops in 3% of amiodarone-treated patients in North America. AIT is classified as type 1 or type 2. Type 1 AIT occurs in patients with underlying thyroid pathology such as autonomous nodular goiter or Graves’ disease. Type 2 AIT is a result of amiodarone causing a subacute thyroiditis with release of preformed thyroid hormones into the circulation.

OBJECTIVES:

To review the literature and present an overview of the differentiation between and management of type 1 and type 2 AIT.

METHODS:

PubMed, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature and Medscape searches of all available English language articles from 1983 to 2006 were performed. Search terms included ‘amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis’, ‘complications’, ‘management’, ‘treatment’ and ‘colour flow Dopper sonography’.

RESULTS:

There is evidence to suggest that to differentiate between type 1 and type 2 AIT, a careful history and physical examination should be performed to identify pre-existing thyroid disease. An iodine-131 uptake test and colour flow Doppler sonography should be performed. Patients with type 2 AIT should receive a trial of glucocorticoids, whereas those with type 1 should receive antithyroid therapy. For patients in whom the mechanism of the thyrotoxicosis is unclear, a combination of prednisone and antithyroid therapy may be considered.

Keywords: Amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis, Colour flow Doppler sonography, Complications, Management, Treatment

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

Une thyrotoxicose induite par l’amiodarone (TIA) se déclare chez 3 % des patients traités à l’amiodarone en Amérique du Nord. La TIA se classe en type 1 et en type 2. La TIA de type 1 se manifeste chez des patients ayant une pathologie thyroïdienne sous-jacente comme un goitre nodulaire autonome ou une maladie de Graves. La TIA de type 2 se produit lorsque l’amiodarone provoque une thyroïdite subaiguë en libérant dans la circulation des hormones thyroïdiennes préformées.

OBJECTIFS :

Procéder à une analyse biographique et présenter un aperçu de la différenciation entre la TIA de type 1 et de type 2 ainsi que de la prise en charge de ces deux manifestations de la TIA.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

On a effectué des recherches de tous les articles anglophones disponibles entre 1983 et 2006 dans PubMed, le Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature et Medscape. Les termes de recherche étaient amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis, complications, management, treatments et colour flow Dopper sonography.

RÉSULTATS :

Selon les données probantes, pour distinguer la TIA de type 1 de celle de type 2, il faut procéder à une anamnèse et à un examen physique attentifs afin de repérer une maladie thyroïdienne préexistante. Il faudrait effectuer un test à l’iode 131 et une sonographie Doppler codage couleur. Les patients atteints de TIA de type 2 devraient recevoir des glucocorticoïdes à l’essai, tandis que ceux atteints de TIA de type 1 devraient recevoir des antithyroïdiens. Dans le cas des patients chez qui le mécanisme de thyrotoxicose n’est pas clair, on peut envisager une association de prednisone et d’antithyroïdiens.

Amiodarone is a class III antiarrhythmic drug used in the treatment of recurrent severe ventricular arrhythmias, paroxysmal atrial tachycardia, atrial fibrillation and maintenance of sinus rhythm after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation (1). Amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis (AIT) develops in 3% of amiodarone-treated patients in North America. For those living in iodine-depleted areas, the incidence is higher (10%) (2). This risk also increases with increased dosage (3).

The thyrotoxicosis is mediated by amiodarone’s iodine content. In each 200 mg tablet, there is 75 mg of iodine; approximately 10% of the iodine is released as free iodide daily (4). Amiodarone is very lipophilic and accumulates in adipose tissue, cardiac and skeletal muscle, and the thyroid. With long-term treatment, there is a 40-fold increase in plasma and urinary iodide levels, and an elimination half-life of 50 to 100 days (5,6). The pharmacological concentration of iodide associated with amiodarone treatment causes inhibition of thyroidal T4 and T3 production and release within the first two weeks of treatment (the Wolff-Chaikoff effect) (7). Amiodarone also inhibits type 1 5′-deiodinase activity in peripheral tissue (8). Amiodarone and its metabolites demonstrate direct toxicity to cultured thyroid cells exposed to media with concentrations above those normally found in patients (9).

The effects of amiodarone on the thyroid can be seen as early as a few weeks after starting treatment and/or up to several months after its discontinuation (10). Because thyroid dysfunction is relatively common in amiodarone therapy, all patients should have free thyroxine and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels measured before starting therapy, at three- to four-month intervals during treatment and for at least one year after the amiodarone is discontinued. A diagnosis of AIT can also be considered at any time in a patient who develops clinical signs of thyrotoxicosis (Table 1) (10). Cardiac manifestations may be absent due to amiodarone’s effect on the heart. Any patient who is taking amiodarone or has discontinued it within the previous year should be evaluated for AIT if they develop cardiac decompensation such as ventricular tachycardia (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Signs and symptoms of amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis

|

Noncardiac signs |

| Unexplained weight loss |

| Tremor |

| Muscle weakness |

| Low-grade fever |

| Restlessness |

| Enlarging goiter |

|

Cardiac signs |

| Sinus tachycardia |

| Atrial fibrillation |

| Ventricular tachycardia |

| Angina |

| Heart failure |

|

Laboratory signs |

| Total and free T4 levels increased |

| Total and free T3 levels increased |

| Thyroid-stimulating hormone dramatically decreased |

Data from reference 10

The differential diagnoses of AIT are classified as type 1 and type 2. Type 1 AIT occurs in patients with an underlying thyroid pathology such as autonomous nodular goiter or Graves’ disease. In these patients, there is accelerated thyroid hormone synthesis secondary to the iodide load from the amiodarone therapy (the Jod-Basedow phenomenon) (11). In type 2 AIT, the thyrotoxicosis is a destructive thyroiditis that results in excess release of preformed T4 and T3 into the circulation (11). It typically occurs in patients without underlying thyroid disease, and is caused by a direct toxic effect of amiodarone on thyroid follicular cells. The thyrotoxic phase may last several weeks to several months, and it is often followed by a hypothyroid phase with eventual recovery in most patients. For unclear reasons, the toxic effects of amiodarone may take two to three years to manifest. The majority of cases of AIT in North America are type 2, whereas type 1 AIT predominates in iodine-deficient areas of the world.

DIFFERENTIATING BETWEEN TYPE 1 AND TYPE 2 AIT

We reviewed the literature to assess the methods of differentiating between type 1 and type 2 AIT, as well as the management strategies for both conditions. PubMed, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature and Medscape searches of all available English language articles published from 1983 to 2006 were performed. Search terms included ‘amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis’, ‘complications’, ‘management’, ‘treatment’ and ‘colour flow Dopper sonography’ (CFDS).

Differentiating type 1 from type 2 is important because it has therapeutic implications. However, this may be difficult because many patients have a mixture of both mechanisms (12). Thyroid function tests are not helpful in differentiating type 1 from type 2 AIT. Evaluation should include a careful history and physical examination to determine whether the patient has a pre-existing thyroid condition. Physical examination may reveal a goiter or exophthalmos. Ultrasonography of the thyroid may show an enlarged gland or a nodular goiter.

The iodine-131 uptake test can help differentiate type 1 from type 2 AIT. The uptake is typically normal or high in type 1 AIT, whereas in type 2, there is very little or no uptake of the iodine due to destruction or damage to the thyroid tissue (13). However, some patients with type 1 AIT may have uptake values below 3% because the uptake of radioiodine tracer is inhibited by high intrathyroidal iodine concentrations, even with accelerated thyroid activity (14–17). This is common in iodine-sufficient areas and can lead to a misdiagnosis of patients with type 1 AIT (13).

Biochemical markers to detect destruction of the thyroid gland can provide further information but may not assist with the diagnosis. For example, serum thyroglobulin levels may be elevated in both type 1 and type 2 AIT. Elevation in type 2 AIT is due to thyroid gland destruction, whereas in type 1, it may simply be due to the goiter, regardless of whether there is hyperthyroidism or autoimmunity (14). The presence of thyrotropin receptor antibodies suggests Graves’ disease. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is thought to be a better marker because it has been found to be normal or mildly elevated in patients with type 1 AIT and significantly elevated in patients with type 2 AIT (18). IL-6 may be elevated in patients with other coexisting illnesses such as heart failure, nonthyroidal conditions and other thyroid conditions such as Graves’ disease (18). Additionally, some patients with type 2 AIT have been reported to have unexpectedly low IL-6 levels, which may be related to the commercial assay used (10). Overall, it is believed that IL-6 testing should be used to follow patients with type 2 AIT who present with significantly elevated levels of IL-6, or have exacerbations during weaning of treatment and in cases of type 1 AIT that recur or fail to respond to treatment.

A tool that is considered to be the best for rapid and early diagnosis of type 1 and 2 AIT is CFDS (19,20). This test determines the amount of blood flow within the thyroid and provides information about the morphology of the thyroid. Eighty per cent of patients can be classified as having type 1 or 2 AIT by CFDS (19,20). The four major patterns are described in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Colour flow Doppler sonography of the thyroid in amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis (AIT)

| Pattern 0: Absent vascularity, gland destruction |

| Pattern 1: Uneven patchy parenchymal flow |

| Pattern 2: Diffuse, homogeneous distribution of increased flow, similar to Graves’ disease |

| Pattern 3: Markedly increased signal and diffuse homogeneous distribution |

Pattern 0 is associated with type 2 AIT. Patterns 1 to 3 are associated with type 1 AIT

TREATMENT AND MANAGEMENT

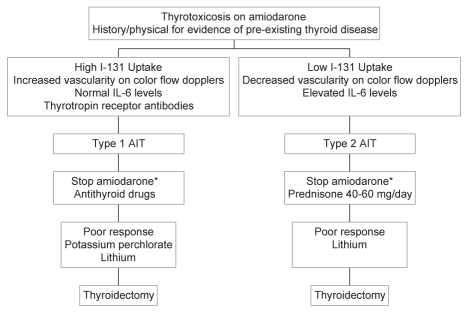

Treatment of AIT is difficult, especially when the type is uncertain. Factors complicating the treatment decision include the importance of amiodarone in the management of the patient’s arrhythmia. Additionally, amiodarone’s long drug elimination half-life and the large total-body iodine stores indicate that the thyrotoxicosis may not resolve for months. The management of AIT is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1).

Management of amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis (AIT). *If possible. I-131 Iodine-131; IL-6 Interleukin 6

Overall, mild AIT resolves spontaneously in approximately 20% of cases (20). Type 1 AIT is treated with a thionamide because it is caused by increased hormonal synthesis (10). Higher than average doses are often required (eg, propylthiouracil 450 mg to 600 mg daily, or methimazole 30 mg to 40 mg daily). The dose is gradually tapered to a low maintenance dose. If the amiodarone is stopped, the thionamide can be discontinued after six to 18 months, when the urine iodide level returns to normal; however, if amiodarone is continued and the thyrotoxicosis is thought to be secondary to the iodide load, the patient should remain on the thionamide.

Another therapy for type 1 AIT is potassium perchlorate, which minimizes intrathyroidal iodine content by competitively inhibiting thyroidal iodine intake (21). Potassium perchlorate must be used with caution, because high doses are associated with aplastic anemia (20). It is recommended that daily doses be less than 1000 mg, or dosages be tapered or stopped after 30 days (21). Perchlorate is also not currently available in Canada. Lithium carbonate has also been used in addition to a thionamide to speed recovery if the thyrotoxicosis is severe (ie, more than 23 months on amiodarone, thyroxine at least 50% above the upper limit of normal) (22). If the radioiodine uptake is high enough, treatment with radioiodine may be considered; however, this is not usually an option because the radioiodine uptake is typically low (23,24). If thyrotoxicosis worsens after initial control, the possibility of overlap with type 2 AIT should be considered and treatment for type 2 AIT should be initiated. Differences in patient responses to treatment may also indicate the possibility that patient-specific factors are involved in the development of AIT. AIT has a complex pathogenesis that is still being investigated.

Type 2 AIT is treated with glucocorticoids for anti-inflammatory and membrane-stabilizing effects (20). Prednisone is started at 40 mg to 60 mg daily and tapered over two to three months. During the taper, exacerbations can occur, which should be treated by increasing the steroid dose again. Patients may develop transient hypothyroidism when the thyrotoxicosis resolves and may benefit from thyroid hormone replacement therapy. Lithium has also been used in patients with type 2 AIT. It is believed that lithium inhibits thyroid hormone secretion (22).

For patients who fail to respond to therapy, total thyroidectomy should be considered (25–27). Often, the risk of surgery under careful cardiovascular monitoring is less than the risk of several months of uncontrolled thyrotoxicosis. The use of plasmapheresis has only been described in case reports (28).

CONCLUSIONS

To differentiate between type 1 and type 2 AIT, a careful history and physical examination should be performed to identify pre-existing thyroid disease. An iodine-131 uptake test and CFDS should be performed. Patients with type 2 AIT should receive a trial of glucocorticoids, whereas those with type 1 should receive antithyroid therapy. For patients in whom the mechanism of the thyrotoxicosis is unclear, a combination of prednisone and antithyroid therapy may be considered.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 69-year-old man was referred with amiodarone-associated thyrotoxicosis. His medical history was significant for coronary artery disease with a myocardial infarction 15 years previously as well as a mechanical aortic valve replacement 10 years previously. His medical history also included hypertension and dyslipidemia. He had been treated with amiodarone for the previous three years to manage paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. He had no personal or family history of thyroid disease.

After the patient initiated the amiodarone treatment, his cardiologist routinely measured free thyroxine and TSH levels at six-month intervals. The levels remained normal for the first three years of therapy; however, his most recent tests revealed an elevated free thyroxine of 53 pmol/L (normal range 9 pmol/L to 25 pmol/L) and a suppressed TSH of less than 0.02 mU/L (normal range 0.25 mU/L to 5 mU/L).

The patient reported a three-month history of increasing fatigue. He also experienced an unintentional 7 kg weight loss, and noticed increased perspiration and sensitivity to heat. He denied any tremor, mood changes or a change in bowel habit.

His medications included 300 mg of amiodarone, 25 mg of hydrochlorothiazide, 2 mg of warfarin, 10 mg of ramipril and 10 mg of atorvastatin, all daily.

On physical examination, his weight was 79 kg and his height was 1.76 m (body mass index of 25.5 kg/m2). His blood pressure was 118/52 mmHg and his heart rate was 64 beats/min and regular. There were no signs of left or right heart failure, and his aortic valve prosthesis had normal sounds. His thyroid gland was not palpable. There was no hand tremor or signs of thyroid eye disease.

The initial laboratory results confirmed hyperthyroidism with a free thyroxine of 49.9 pmol/L and a TSH of less than 0.02 mU/L. A technetium thyroid scan showed no discernable uptake against the background activity in the neck. Iodine-131 uptake at 24 h was minimal at 0.31%. CFDS revealed absent intraparenchymal vascularity (pattern 0). IL-6 levels were 514 fmol/L (normal level less than 100 fmol/L). Thyrotropin-binding inhibitory immunoglobulins were undetectable.

The patient was diagnosed with type 2 AIT. His cardiologist requested that he remain on the amiodarone because his paroxysmal atrial fibrillation was difficult to manage with other antiarrhythmic agents. He was started on 30 mg of prednisone daily. After three months, his free thyroxine and TSH had normalized, and his thyrotoxic symptoms had resolved (Table 3). His prednisone therapy was tapered over two weeks and stopped. Thyroid function tests remained normal off prednisone.

TABLE 3.

Clinical course of a patient with type 2 amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis

| Clinical course | Free thyroxine, pmol/L* | TSH, mU/L† |

|---|---|---|

| Preprednisone‡ | 53 | <0.02 |

| Preprednisone§ | 49.9 | <0.02 |

| After 1 month of prednisone | 34 | <0.02 |

| After 2 months of prednisone | 28.5 | 0.04 |

| After 3 months of prednisone (final day of prednisone) | 15.3 | 2.7 |

| 1 month after stopping prednisone | 16.3 | 3.91 |

| 6 months after stopping prednisone | 16.6 | 3.91 |

| 12 months after stopping prednisone | 17.8 | 3.03 |

Normal range is 9 pmol/L to 25 pmol/L;

Normal range is 0.25 mU/L to 5 mU/L;

Recent test by the cardiogist;

Examination after referral. TSH Thyroid-stimulating hormone

REFERENCES

- 1.Goldschlager N, Epstein AE, Naccarelli G, et al. Practical guidelines for clinicians who treat patients with amiodarone. Practice Guidelines Subcommittee, North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1741–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.12.1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martino E, Aghini-Lombardi F, Mariotti S, et al. Environmental iodine intake and thyroid dysfunction during chronic amiodarone therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1984;101:28–34. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-101-1-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouvy ML, Heerdink ER, Hoes AW, Leufkens HG. Amiodarone-induced thyroid dysfunction associated with cumulative dose. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2002;11:601. doi: 10.1002/pds.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kennedy RL, Griffiths H, Gray TA. Amiodarone and the thyroid. Clin Chem. 1989;35:1882–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roa RH. Iodine kinetic studies during amiodarone treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1986;62:563–8. doi: 10.1210/jcem-62-3-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pollak PT, Bouillon T, Shafer SL. Population pharmacokinetics of long-term oral amiodarone therapy. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2000;67:642–52. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2000.107047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lambert MJ, Unger J, De Nayer P, et al. Are selective increases in serum thyroxine (T4) due to iodinated inhibitor of T4 monodeiodination indicative of hyperthyroidism? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1982;55:1058–65. doi: 10.1210/jcem-55-6-1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sogol PB, Hershman JM, Reed AW, et al. The effects of amiodarone on serum thyroid hormones and hepatic 5′-deiodinase. Endocrinology. 1983;113:1464–9. doi: 10.1210/endo-113-4-1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiovato L, Martino E, Tonacchera M, et al. Studies on the in vitro cytotoxic effects of amiodarone. Endocrinology. 1994;134:2277–82. doi: 10.1210/endo.134.5.8156930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cardenas GA, Cabral JM, Leslie CA. Amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis: Diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Cleve Clin J Med. 2003;70:624–31. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.70.7.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newman CM, Price A, Davies DW, et al. Amiodarone and the thyroid: A practical guide to the management of thyroid dysfunction induced by amiodarone therapy. Heart. 1998;79:121–7. doi: 10.1136/hrt.79.2.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brennan MD, Erickson DZ, Carney JA, et al. Nongoitrous (type 1) amiodarone-associated thyrotoxicosis; evidence of follicular disruption in vitro and in vivo. Thyroid. 1995;5:177. doi: 10.1089/thy.1995.5.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martino E, Aghini-Lombardi F, Lippi F, et al. Twenty-four hour radioactive iodine uptake in 35 patients with amiodarone associated thyrotoxicosis. J Nucl Med. 1985;26:1402–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martino E, Bartalena L, Bogazzi F, Braverman LE. The effects of amiodarone on the thyroid. Endocrine Rev. 2001;22:240–54. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.2.0427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daniels GH. Amiodarone induced thyrotoxicosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:3–8. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.1.7119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harjai KJ, Licata AA. Effects of amiodarone on thyroid function. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:63–73. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-1-199701010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ludica-Souza C. Amiodarone-induced thyroid dysfunction. Endocrinologist. 1999;9:216–27. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bartalena L, Grasso L, Brogioni S, et al. Serum interleukin-6 in amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;789:423–7. doi: 10.1210/jcem.78.2.8106631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bogazzi F, Martino E, Dell’Unto E, et al. Thyroid color flow Doppler sonography and radioiodine uptake in 55 consecutive patients with amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis. J Endocrinol Invest. 2003;26:635. doi: 10.1007/BF03347021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eaton SE, Euinton HA, Newman CM, et al. Clinical experience of amiodarone induced thryotoxicosis over a 3-year period: Role of colour-flow Doppler sonography. Clin Endocrinol. 2002;56:33–8. doi: 10.1046/j.0300-0664.2001.01457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolf J. Perchlorate and the thyroid gland. Pharmacol Rev. 1998;50:89–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dickstein G, Schechner C, Adawi F, et al. Lithium treatment in amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis. Am J Med. 1997;102:454–8. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(97)00047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hermida JS, Jarry G, Tcheng E, et al. Radioiodine ablation of the thyroid to allow the reintroduction of amiodarone treatment in patients with a prior history of amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis. Am J Med. 2004;116:345. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matino E, Bartalena L, Mariotti S, et al. Radioactive iodine thyroid uptake in patients with amiodarone-iodine-induced thyroid dysfunction. Acta Endocrinol. 1988;119:167–73. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.1190167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Houghton SG, Farley DR, Brennan MD, et al. Surgical management of amiodarone-associated thyrotoxicosis: Mayo Clinic experience. World J Surg. 2004;28:1083–7. doi: 10.1007/s00268-004-7599-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farwell AP, Abend SL, Huang SK, et al. Thyroidectomy for amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis. JAMA. 1990;263:1526–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams M, Lo Gerfo P. Thyroidectomy using local anesthesia in critically ill patients with amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis: A review and description. Thyroid. 2002;12:523–5. doi: 10.1089/105072502760143926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diamond TH, Rajagopal R, Ganda K, Manoharan A, Luk A. Plasmapheresis as a potential treatment option for amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis. Int Med J. 2004;34:369–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1444-0903.2004.00600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]