Summary

An understanding of the molecular mechanisms of cell fate determination in the nervous system requires the elucidation of transcriptional regulatory programs that ultimately control neuron-type-specific gene expression profiles. We show here that the C. elegans Tailless/TLX-type, orphan nuclear receptor NHR-67 acts at several distinct steps to determine the identity and subsequent left/right (L/R) asymmetric subtype diversification of a class of gustatory neurons, the ASE neurons. nhr-67 controls several broad aspects of sensory neuron development and, in addition, triggers the expression of a sensory neuron-type-specific selector gene, che-1, which encodes a zinc-finger transcription factor. Subsequent to its induction of overall ASE fate, nhr-67 diversifies the fate of the two ASE neurons ASEL and ASER across the L/R axis by promoting ASER and inhibiting ASEL fate. This function is achieved through direct expression activation by nhr-67 of the Nkx6-type homeobox gene cog-1, an inducer of ASER fate, that is inhibited in ASEL through the miRNA lsy-6. Besides controlling bilateral and asymmetric aspects of ASE development, nhr-67 is also required for many other neurons of diverse lineage history and function to appropriately differentiate, illustrating the broad and diverse use of this type of transcription factor in neuronal development.

Keywords: C. elegans, Left/right asymmetry, Neuronal development, Transcriptional regulation

INTRODUCTION

In acquiring a specific identity, a neuron must interpret spatial, temporal and lineal information throughout its development, from its birth as a neural precursor until its postmitotic state. The ASE chemosensory neurons of the nematode C. elegans have proven to be a useful system with which to study the regulatory mechanisms that define neuronal identity (Hobert, 2005; Hobert, 2006). The identity of the ASE neuron class can be broken down into individual components, which are controlled by distinct regulatory programs. ASE neurons express pan-neuronal features, shared by all neurons; they also express features that are specific to all sensory neurons and they express features that assign a unique identity to ASE. The unique identity determinant of ASE fate is the terminal selector gene che-1 (Chang et al., 2003; Etchberger et al., 2007; Uchida et al., 2003). Its loss results in a failure to express ASE-specific features, but leaves expression of pan-sensory and pan-neuronal features intact. The RFX-box transcription factor daf-19 controls pan-sensory features of ASE and all other sensory neurons (Swoboda et al., 2000). As yet unknown regulatory factors may act through a common cis-regulatory motif to control the expression of pan-neuronal features of a neuron (Ruvinsky et al., 2007). Whether and to what extent these regulatory programs are coupled to one another is not known.

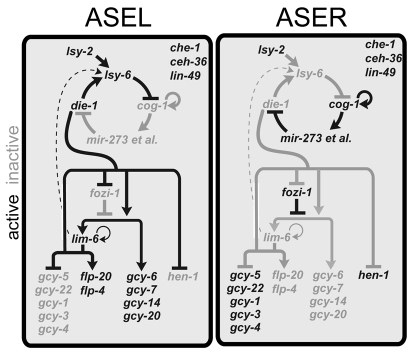

After adoption of their initial, bilaterally symmetric identity, the ASE neurons undergo an additional diversification program that occurs across the L/R axis, the least understood axis during nervous system development. This diversification program results in the L/R asymmetric expression of a family of putative chemoreceptors of the guanylyl cyclase (gcy) family, with some gcy genes being exclusively and stereotypically expressed in ASEL and others in ASER (Ortiz et al., 2006; Yu et al., 1997). This molecular asymmetry endows the left and right ASE neuron with the ability to sense and discriminate a distinct set of chemosensory cues (Ortiz et al., 2009; Pierce-Shimomura et al., 2001; Suzuki et al., 2008). The L/R asymmetric gene expression program of ASEL and ASER is brought about by a complex gene regulatory network of several transcription factors and miRNAs that act in a bistable feedback loop (Fig. 1) (Hobert, 2006). This loop provides a transcriptional output that feeds into gcy gene expression. The input into the loop that determines which loop components predominate in ASEL versus ASER is not molecularly known, but is dependent on the distinct lineage history of the two ASE neurons and a Notch signal received differentially by the precursors of ASEL and ASER (Poole and Hobert, 2006).

Fig. 1.

Gene regulatory mechanisms that control ASEL/R development in C. elegans. ASEL and ASER fate are controlled by a bistable, double-negative feedback loop. All genes shown here are also directly controlled by the terminal selector gene che-1, an overall ASE fate inducer.

In order to uncover additional components of this L/R asymmetric gene regulatory program, we undertook a large-scale genetic screen in which the ASE L/R fate decision was inappropriately executed (Sarin et al., 2007). One mutant locus isolated from this screen, lsy-9, displays a highly unusual phenotype. In what appears to be an intriguing reversal of asymmetry, a fraction of animals express the left fate marker lim-6::gfp exclusively in the ASER rather than the ASEL neuron (Sarin et al., 2007). No other such `reversal' mutant was retrieved from the screen. In addition to the `reversal' category, some animals also display a complete loss of the ASEL marker, whereas others display a `bilateralization', in that both ASEL and ASER express the left fate marker (Sarin et al., 2007). Here, we describe this mutant phenotype in more detail and show that this gene is allelic to the orphan nuclear receptor encoding gene nhr-67, a homolog of Drosophila tailless, previously identified by genome sequence analysis (Sluder et al., 1999). We find that the unusual nhr-67/lsy-9 phenotype is caused by two independent activities of nhr-67 early and late in ASE development. We also show that nhr-67 function controls the identity of various different neuronal cell types.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and transgenes

N2 Bristol wild-type (Brenner, 1974) and CB4856 Hawaiian wild-type (Hodgkin and Doniach, 1997) isolates were used. Transgenes that label ASEL and ASER fates included: ASEL markers otIs3V=Is[gcy-7prom::GFP; lin-15 (+)], otIs114I=Is[lim-6prom::gfp; rol-6(d)] and otIs160IV=Is[lsy-6prom::gfp; unc-122prom::GFP]; ASER markers ntIs1V=Is[gcy-5prom::GFP; lin-15 (+)] and syIs73 [cog-1prom::GFP; dpy-20 (+)]; and ASEL/R markers otIs151V=Is[ceh-36prom::DsRed2; rol-6(d)], otIs125=Is[flp-6prom::GFP], oyIs59=Is[osm-6::GFP; lin-15 (+)], otIs188=Is[che-1::YFP; rol-6(d)] and otIs217=Is[che-1prom::HIS-3::mCherry; rol-6(d)]. Reporters for other cell types included: pkIs531=Is[gpa-9::GFP; lin-15 (+)], ynIs2022III= Is[flp-8prom::GFP; rol-6(d)], oyIs17=Is[gcy-8prom::GFP; lin-15 (+)], kyIs104X=Is[str-1::GFP; lin-15 (+)], kyIs140=Is[str-2::GFP; rol-6(d)], gmIs12=Is[srb-6::GFP; rol-6(d)], otIs182=Is[inx-18prom::GFP], oyIs14V=Is[sra-6::GFP; lin-15 (+)], mgIs18=Is[ttx-3::GFP; lin-15 (+)], otIs138=Is[ser-2prom::GFP; rol-6(d)], vtIs1=Is[dat-1::GFP; rol-6(d)], bgIs312I=Is[pes-6::GFP], mgIs20=Is[lim-6::GFP; rol-6(d)], oxIs12X= Is[unc-47prom::GFP; lin-15 (+)] and otIs173=Is[F25B3.3::DsRed2; ttx-3::GFP]. Other transgenic lines: otEx3362=Ex[nhr-67::mCherry; elt-2::GFP], otEx3910=Ex[cog-1promAnhr-67sitedel::gfp; elt-2::gfp] and otEx3761=Ex[cog-1promA::gfp; elt-2::gfp].

lsy-9/nhr-67 alleles

In several previously described genetic screens, we identified four alleles of lsy-9, ot85, ot136, ot202 and ot210, which display a heterogeneous class V Lsy phenotype (Sarin et al., 2007). We have since found that three other mutant alleles, ot158, ot190 and ot247, previously considered separate genetic loci (Sarin et al., 2007) are in fact allelic to lsy-9. ot158 was considered a separate genetic locus owing to its distinct phenotype (class I `2 ASEL' phenotype). Mapping of ot158 revealed it to be linked to the lsy-9 locus, and allele sequencing, transformation rescue and complementation tests determined that ot158 is an allele of lsy-9. ot190 was initially mapped onto a separate chromosome (Sarin et al., 2007), yet further analysis revealed that the SNP marker used for this analysis, F32B5, provided misleading mapping data. ot190 was found to be allelic to lsy-9 by allele sequencing and complementation tests. ot247 was placed into a distinct complementation group from lsy-9 owing to its failure to complement another lsy gene, lsy-18. However, allele sequencing, additional complementation tests and rescue analysis showed that ot247 is an allele of nhr-67. The genome knockout consortia generated three separate deletion alleles of lsy-9 that are very similar in molecular nature and we therefore only analyzed one of them, ok631. One additional lsy-9/nhr-67 allele, ot407, was retrieved by a non-complementation screen. For this screen, a balanced strain with the genotype nhr-67(ok631)/mgIs18 unc-24; Ex[nhr-67-fosmid; elt-2::gfp] was generated. Heterozygous animals are viable, non-Unc, express gfp in the AIY interneuron (mgIs18/+), and express, with limited penetrance, elt-2::gfp in the intestine, which marks a rescuing array with the nhr-67-containing fosmid. Progeny of this balanced strain will be of the same genotype, will be of the genotype mgIs18 unc-24/mgIs18 unc-24 (and therefore Unc) or will be ok631/ok631, and all viable adults will display green intestinal cells as they need the array to rescue the ok631 lethality. We mutagenized several populations of this strain using EMS as previously described (Brenner, 1974; Gengyo-Ando and Mitani, 2000). We selected for animals in the next generation that are heterozygous, i.e. non-Unc, and displayed expression of gfp in AIY (from mgIs18), but nevertheless contain the elt-2::gfp marked rescuing array with complete penetrance. Such animals are supposedly of the nhr-67(ok631)/mgIs18 nhr-67(new allele) unc-24 genotype, as they require the rescuing array to live to adulthood. We then homozygosed nhr-67(new allele) by selecting for Unc animals in the next generation and subsequently sequenced the nhr-67 locus in inviable, non-transgenic progeny. We retrieved one allele from this screen, ot407.

Reporter genes

che-1 and nhr-67 reporter genes were created using λ-Red-mediated recombineering in bacteria as described (Dolphin and Hope, 2006; Tursun et al., 2009). Briefly, the che-1-containing fosmid (WRM066bC03) and the nhr-67-containing fosmid (WRM0613bE08) were each electroporated and maintained in the E. coli strain EPI-300 T1R (Epicentre). Using tetA recombineering cassettes for two-step counter selection with tetracycline and streptomycin, or using the more efficient flp recombinase-removable galK-based cassettes, we inserted yfp (che-1) or mCherry (nhr-67, che-1) immediately preceding the stop codon at the C terminus of the respective gene, which resulted in a translational fusion at each locus. Recombineered fosmids were sequenced at their recombineered junctions. For the che-1::yfp and che-1::mCherry fosmid injection, the fosmid was digested with SacII and injected at 10 ng/μl, together with ScaI-digested rol-6(d) (pRF4; 2 ng/ul) and PvuII-digested N2 genomic DNA (100 ng/μl) to generate a complex array. The DNA was injected into che-1(ot94); ntIs1. After integration of the che-1::yfp fosmid array by gamma irradiation ntIs1 was outcrossed during backcrossing. The resulting array is called otIs188. For the nhr-67::mCherry fosmid injection, the fosmid was injected at 50 ng/μl, together with 30 ng/μl elt-2::gfp (pJM67) and 50 ng/μl pBluescript carrier DNA. The DNA was injected into nhr-67(ok631)/nT1. The resulting array is called otEx3362.

Expression analysis of nhr-67

The nhr-67::mCherry fusion DNA was co-injected (50 ng/μl) with elt-2::GFP (30 ng/μl) into balanced ok631/nT1 animals to ascertain rescuing ability. Cells expressing nhr-67 were identified using 4D microscopy and SIMI BioCell software as described (Schnabel et al., 1997). Briefly, otEx3362 (nhr-67::mCherry; elt-2::GFP) gravid adults were dissected and single two-cell embryos were mounted and visualized on a Zeiss Axioplan 2 compound microscope. Nomarski stacks were taken every 35 seconds and images within a stack at ∼1 μm apart. Embryos were flashed with TRIT-C-filtered fluorescence at pre-determined time points corresponding to periods between divisions within the AB lineage. After a fluorescent flash, the movie was suspended and embryos were scored for presence of elt-2::GFP (and therefore the array). Movies of embryos not containing the array were discarded. At least two movies were taken per ABx cell stage, i.e. AB4 cells, AB8 cells, AB16 cells, etc., until the bean stage. Movies were lineaged using the SIMI BioCell program. Two nhr-67-expressing blastomeres at the mid-gastrulation stage could not be identified owing to technical limitations. Larval and adult nhr-67 expression was determined by nuclei position and cell body morphology of mCherry-expressing cells. The transgene osm-6::gfp (oyIs59) was also used in the background to help establish the relative positions of these cells. One pair of neurons just posterior to the RIR neuron showed dim expression and were likely to be the RICL/R neurons, but could not be reliably identified owing to their variable positioning. Three cells anterior to the anterior ring ganglia were not identified but were likely to be socket and/or pharyngeal neurons.

Yeast one-hybrid analysis

Yeast one-hybrid experiments were conducted as described previously (Deplancke et al., 2004). A 1.8-kb fragment including the conserved NR2E motif and ASE motifs was amplified from two constructs, cog-1promA (O'Meara et al., 2009) and cog-1promA nhr-67 del., in which the conserved sequence AAGTCA had been deleted. The resulting constructs were named cog-1promD and cog-1promD nhr-67site del. Each construct was cloned by the Gateway recombination system into pMW2 (Addgene), which contains the His3 reporter. Each vector was subsequently linearized with XhoI and integrated into the Y1H strain YM4271 at the his3-200 locus. Integrants were selected on Sc-His media. Transformations and integrations were performed as described (Deplancke et al., 2004). One hundred nanograms of AD-NHR-67 Destination clone DNA and empty vector DNA (OpenBiosystems) were transformed into each DNAbait:reporter strain. Transformations were plated on SC-Trp media. Thirty-two transformants were randomly selected from each transformation and diluted in 100 μl of water. Four microliters of each dilution were plated on SC -Trp, SC -Trp -His, and SC -Trp -His + 40 mM 3-AT plates. Plates were incubated for 5 days at 30°C and then scored.

RESULTS

lsy-9 mutants display a complex phenotype in the development of left/right asymmetric ASE neurons

lsy-9(ot85) mutant animals were retrieved in a screen for mutants in which the L/R asymmetric fate of the ASE neurons fails to be appropriately executed (Sarin et al., 2007). lsy-9 mutants display a disruption of L/R asymmetric gene expression profiles in ASEL/R, as has previously been shown with a single allele, ot85, using the ASEL fate marker lim-6::gfp and the ASER fate marker gcy-5::gfp (Sarin et al., 2007) (Table 1, Fig. 2A). We have broadened this analysis to include several more alleles of lsy-9, some newly isolated and not described before (Table 1; see also Materials and methods). All alleles are recessive. Four of the six available lsy-9 alleles are homozygous viable, two of them display an early larval arrest phenotype (phenotypic categories of all alleles are summarized in Fig. 2B). With the exception of ot158, discussed in more detail below, all alleles display a similar wide range of phenotypes: in larval and adult animals, the ASEL fate marker lim-6::gfp is either unaffected, bilaterally expressed in both ASEL and ASER, expressed in neither ASEL nor ASER, or expressed exclusively in ASER (Table 1). We used a subset of the available alleles to analyze an additional panel of reporters. We found that the ASEL marker gcy-7 shows a similar range of phenotypes as the lim-6 fate marker (Fig. 2A, Table 1). Moreover, expression of the miRNA lsy-6, an essential trigger of ASEL fate, which is normally only expressed in ASEL, is de-repressed in ASER and/or is lost in ASEL (Fig. 2A, Table 1).

Table 1.

ASE fate in Isy-9/nhr-67 mutant animals

|

Percentage of animals with gfp expression in

ASEL/R*

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fate marker | Genotype | n | |||||||

| ASEL markers | gcy-7 (otls3) | Wild type | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | >100 |

| ot85 | 45.3 | 0 | 16.3 | 23.3 | 0 | 15.1 | 86 | ||

| ok631 | 32.8 | 0 | 24.6 | 28.7 | 0 | 11.5 | 80 | ||

| lim-6 (otls114) | Wild type | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | >100 | |

| ot85 | 54.8 | 1.2 | 13.1 | 23.8 | 0 | 7.1 | 84 | ||

| ok631 | 32 | 0 | 28 | 30 | 0 | 10 | 50 | ||

| ot136 | 80 | 0 | 10 | 8 | 0 | 2 | 50 | ||

| ot202 | 41.4 | 5.2 | 24.1 | 17.2 | 0 | 12.1 | 58 | ||

| ot210 | 79.2 | 1.9 | 3.8 | 11.3 | 0 | 3.8 | 53 | ||

| ot158 | 77.5 | 0 | 21 | 1.5 | 0 | 0 | 137 | ||

| ot190 | 66.7 | 0 | 12.3 | 17.5 | 0 | 3.5 | 57 | ||

| lsy-6 (otls160) | Wild type | 91.4 | 0 | 0 | 8.6 | 0 | 0 | 35 | |

| ot85 | 62.5 | 16.7 | 2.1 | 14.6 | 0 | 4.2 | 48 | ||

| ASER markers | gcy-5 (ntls1) | Wild type | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | >100 |

| ot85 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 0 | 67 | 97 | ||

| ok631 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 61.2 | 1.2 | 37.6 | 82 | ||

| ot407 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 69 | 0 | 31 | 51 | ||

| ot158 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 84 | 50 | ||

| cog-1 (syls73) | Wild type | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 24.6 | 72.4 | 29 | |

| ot85 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 51.4 | 0 | 48.6 | 37 | ||

| or | |||||||||

| ASEL/R bilateral markers | ceh-36 (otls151) | Wild type | 100 | 0 | 0 | >100 | |||

| ok631 | 44 | 24 | 31 | 86 | |||||

| ot85 | 59 | 9 | 32 | 98 | |||||

| ot158 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 25 | |||||

| che-1 (otls188) | Wild type | 100 | 0 | 0 | >100 | ||||

| ok631 | 28 | 35 | 37 | 51 | |||||

| ot158 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 40 | |||||

| flp-6 (otls125) | Wild type | 100 | 0 | 0 | 20 | ||||

| ok631 | 53.7 | 9.3 | 37.0 | 54 | |||||

| ot85 | 72 | 10 | 17 | 98 | |||||

| osm-6 (oyls59) | Wild type | 100 | 0 | 0 | >100 | ||||

| ok631 | 71.4 | 0 | 29.6 | 27 | |||||

Circles indicate gfp expression levels in the pair of left and right ASE neurons.

Fig. 2.

Defects observed in lsy-9/nhr-67 mutant animals. (A) lsy-9/nhr-67 regulates ASEL-, ASER-specific and bilateral cell fate markers. Quantification of these data can be found in Table 1. Strains presented from the second row down contain lsy-9(ot85) in the background. Animals were scored as adults. (B) Allelic series of lsy-9 alleles. (C) Apparent L/R reversal defects are caused by a mixture of class I (`2 ASEL') and class III (`no ASE') mutant phenotypes, as revealed by a correlation analysis in which lim-6 (ASEL fate) and ceh-36 (ASEL+ASER bilateral fate) are simultaneously scored with reporter transgenes (lim-6::gfp-otIs114; ceh-36::rfp-otIs151) in a lsy-9(ot85) mutant background. (D) lsy-9/nhr-67 positively regulates expression of the ciliated sensory marker osm-6, as scored with osm-6::gfp (oyIs59). White arrow indicates presence or absence of osm-6 expression in ASE, which was identified by its location relative to surrounding amphid sensory cells. Nomarski image indicates that the ASE nucleus is still present, immediately posterior to ASH. (E) lsy-9/nhr-67 does not affect expression of the pan-neuronal marker F25B3.3. Colored dots indicate cell types as in D. D, dorsal; V, ventral; A, anterior; P, posterior.

In contrast to the variety of phenotypes observed with ASEL markers, ASER markers show only one phenotype: ASER marker expression (the terminal differentiation marker gcy-5 or the ASER inducer cog-1) is either normal or lost (Fig. 2A, Table 1). ASER marker expression does not therefore present the mirror image of ASEL marker expression, i.e. in those cases in which ASEL marker expression is lost, there is no concomitant gain of ASER marker expression.

The analysis of bilaterally expressed markers, the homeobox gene ceh-36 and the FMRFamide gene flp-6, displayed an unexpected phenotype. Expression of the bilateral markers was unaffected, lost in either ASEL or ASER, or lost in both (Fig. 2A, Table 1). This observation raised the possibility that the loss of asymmetric fate markers, such as lim-6::gfp, might not be a reflection of a laterality defect in which left fate has converted to the right fate, but might rather be reflective of an overall differentiation defect of ASE. To assess this possibility, we analyzed ASEL fate and bilateral fate simultaneously, using rfp-tagged ceh-36 (bilateral marker) and gfp-tagged lim-6 (ASEL marker). We found a perfect correlation of loss of ASEL fate and loss of the bilateral fate marker (Fig. 2C). Moreover, whenever ASE fate was executed in either ASEL or ASER, as assessed by normal ceh-36 expression, the neuron was likely to express the ASEL fate marker lim-6 (Fig. 2C). This observation provides an explanation for what appears to be a `reversal defect' in which ASEL fate is only expressed in ASER. In those animals, the left neuron does not differentiate (no ceh-36 expression), but the right neuron differentiates and aberrantly executes the left fate. In conclusion, the lsy-9 phenotype is a mixture of what we previously termed a class III phenotype (`no correct bilateral ASE fate specification') and a class I phenotype (`2 ASEL', instead of `1 ASEL+ 1 ASER') (Sarin et al., 2007).

lsy-9 acts both upstream and downstream of che-1

The failure of ASE to express asymmetric and bilateral markers could reflect an inability to differentiate or could indicate a fate transformation in which ASEL or ASER have adopted the fate of their respective sister cell, which normally undergoes programmed cell death (see Fig. S1 in the supplementary material). To test this possibility, we generated a lsy-9; ced-4 double mutant in which cell death is inhibited. In those animals, the loss of marker gene expression is not alleviated. Instead, ectopic ASE marker expression is occasionally observed in the now undead sisters of ASEL and ASER (see Fig. S1 in the supplementary material).

The other possibility for a loss of ASE fate marker expression is that lsy-9 acts upstream of the ASE fate inducer che-1, which encodes a C2H2 zinc-finger transcription factor (Chang et al., 2003; Etchberger et al., 2007; Uchida et al., 2003). A loss of che-1 would be expected to lead to a loss of expression of both bilateral and asymmetric features of ASE (class III phenotype) (Chang et al., 2003; Etchberger et al., 2007; Uchida et al., 2003). We tested this possibility by examining che-1 expression in lsy-9 mutants, using a fosmid-recombineered che-1 reporter construct (Tursun et al., 2009). This construct, che-1::yfp, contains the entire che-1 locus together with three upstream and two downstream genes, is engineered to contain yfp fused to the last exon of che-1 and rescues the che-1 mutant phenotype. Postembryonically, this reporter is exclusively expressed in ASEL and ASER throughout larval and adult stages. In the embryo, expression is also exclusively observed in a pair of cells, starting at the ABalppppppa/ABpraaapppa stage (Fig. 3A). These two cells are the mothers of the two ASE neurons. Expression persists throughout cell division of the ASE mother, which produces ASE(L/R) and a cell that undergoes programmed cell death. Similar expression was observed with a che-1::mCherry construct (data not shown). In lsy-9 mutants, che-1 expression is lost in a large fraction of animals (Fig. 3A; see also Fig. S2 in the supplementary material), suggesting that lsy-9 positively regulates che-1, which then induces general ASE fate. By contrast, lsy-9 expression is not affected in che-1 mutants (see below). It is formally possible that after che-1 induction, lsy-9 and che-1 might cooperate to induce ASE fate, but this appears unlikely as ectopic, gpa-10 promoter-driven expression of che-1 in cells that do not normally express lsy-9 (as described below) is sufficient to induce the expression of ASE-specific terminal differentiation markers (Uchida et al., 2003). Moreover, lsy-9 expression is not maintained in ASE (as described below), whereas che-1 expression is, and this maintained che-1 expression is crucial to maintain ASE fate (Etchberger et al., 2009). che-1 therefore does not appear to need lsy-9 to control bilateral ASE fate.

Fig. 3.

lsy-9/nhr-67 acts upstream of che-1. (A) Embryonic che-1 expression. Nomarski images (top row); fluorescence (bottom row). Three genotypically distinct embryos are highlighted at sequential time points postfertilization at 20°C, from the onset of che-1 expression (∼280 minutes) to almost complete engulfment of the dead sister cell of ASE (∼380 minutes). che-1::yfp (otIs188) expression is shown in a wild-type embryo (blue), in an lsy-9/nhr-67(ok631) mutant embryo (green) and in an lsy-9/nhr-67(ok631) mutant embryo rescued by a nhr-67(+) array [otEx3103=Ex(nhr-67fosmid; elt-2::gfp), red]; note that the strong gfp signal is the elt-2::gfp injection marker. Arrows indicate ASE expression of che-1::yfp; arrowheads indicate the ASE sister cell, which eventually undergoes apoptosis and is consumed by the ASE cell. For quantification, see Fig. S1 in the supplementary material. (B) lsy-9/nhr-67 mutants display ASE dendrite defects. Fluorescent and Nomarski images of ASEL dendrites of wild-type and lsy-9/nhr-67 mutant adult hermaphrodites are shown. Dendrites were visualized using the ASEL-specific transgene lim-6prom::gfp (=otIs114). The penetrance of defects is 16% (n=50) in lsy-9/nhr-67(ot85) and 7% (n=55) in lsy-9/nhr-67(ok631). (C) Cilia defects of ASE neurons in adult lsy-9/nhr-67 mutants. The ASE sensory ending (a thin line immediately following the thicker projection) was visualized using the ASEL-specific transgene lim-6prom::gfp (=otIs114). The cilium is full length in wild-type animals but stubby and bloated in lsy-9/nhr-67 mutant animals. Defects were observed in 9% (n=44) of nhr-67(ot85) animals.

The role of lsy-9 is not restricted to controlling che-1 expression, as lsy-9 defects are more severe than che-1 null mutant effects. In a fraction of lsy-9 animals, the ASE dendrites do not develop appropriately; they are either too short or they overextend (Fig. 3B). In those cases in which the dendrites appear to be appropriately established, the ciliated ultrastructure is defective (Fig. 3C). Moreover, expression of the cilia marker osm-6 is lost in lsy-9 mutants (Fig. 2D). These defects extend beyond those of che-1 mutants, which express osm-6 normally and have normally extended dendrites and ciliated endings (Lewis and Hodgkin, 1977; Uchida et al., 2003) (data not shown). In che-1 mutants, ASE is able to take up the dye DiI through exposed sensory endings (Uchida et al., 2003); this ability is abrogated in lsy-9 mutants (data not shown). In both lsy-9 and che-1 mutants, pan-neuronal fate is executed normally (Uchida et al., 2003) (Fig. 2E). These findings suggest that lsy-9 and che-1 progressively define the identity of ASE. lsy-9 controls broad aspects of ASE fate, including the ciliated sensory neuron identity of ASE, whereas che-1 defines the type of ciliated sensory neuron.

As noted above, the fraction of lsy-9 animals that expresses che-1 and bilateral terminal ASE features will execute the `ASEL fate' on both sides of the animal (class I phenotype), indicating that lsy-9 has a separate role in inducing ASER fate. The ot158 allele appears to genetically separate these two functions, as ot158 mutants execute bilateral ASE fate normally (normal che-1 and ceh-36 expression), but these animals display the class I phenotype (ASER to ASEL switch) that is reflective of a participation in the bistable feedback loop that controls ASEL versus ASER fate (Table 1).

We considered the possibility that the asymmetry defects observed in lsy-9 mutants are a mere reflection of reduced che-1 activity. Several lines of evidence indicate that this possibility is unlikely. First, we raised the levels of che-1 activity in lsy-9(ot158) mutants (in which bilateral fate is executed properly, but asymmetry of fate is not), using a transgene that expresses che-1 under the control of a heterologous promoter (ceh-36prom::che-1), and found that this did not rescue the lsy-9 defects (data not shown). Second, we have recently identified a hypomorphic, partial loss-of-function allele of che-1 that results in the opposite defect to the one we observe in lsy-9 animals - a `2 ASER' phenotype, rather than the lsy-9-type `2 ASEL' phenotype (Etchberger et al., 2009). nhr-67 therefore appears to have separable functions in first inducing ASE fate and then controlling ASEL/R asymmetry.

To assess in more detail how lsy-9 fits into the previously described bistable feedback loop that controls ASEL versus ASER fate, we generated double mutants of lsy-9 with several mutants in components of the bistable feedback loop controlling ASEL/R asymmetry (shown in Fig. 1). We found that the completely penetrant loss of ASEL fate in animals lacking the miRNA lsy-6 was suppressed in lsy-9 mutants (Table 2). Moreover, the ASER neuron still ectopically executed ASEL fate in lsy-9 mutants in the absence of lsy-6 (Table 2). These epistasis data suggest that the asymmetry-determining role of lsy-9 lies, at least in part, downstream of lsy-6. Ectopic expression of the ASER fate inducer cog-1 in ASEL, observed in the gain-of-function allele cog-1(ot123), a 3′UTR deletion, results in a partially penetrant conversion of ASEL to ASER fate (Sarin et al., 2007). This effect was suppressed by lsy-9(ot85), indicating that lsy-9 is required for cog-1 function (Table 2). The completely penetrant loss of ASEL fate in animals defective in die-1, the output regulator of the bistable feedback loop (Fig. 1), was not suppressed by lsy-9 (Table 2), indicating that lsy-9 may act upstream of die-1. In summary, this genetic analysis places lsy-9 into the bistable regulatory loop, at a position downstream of the miRNA lsy-6, but upstream of the output regulator die-1.

Table 2.

Genetic interaction tests

|

ASEL

|

ASER

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | % animals with lim-6::gfp* | % animals with gcy-5::gfp† | % animals with lim-6::gfp | % animals with gcy-5::gfp |

| Wild type | 100 (n>100) | 0 (n>100) | 0 (n>100) | 100 (n>100) |

| lsy-9(ot85)‡ | 100 (n=68) | 0 (n=97) | 44 (n=68) | 67 (n=97) |

| lsy-9(ok631)§ | 100 (n=50) | 0 (n=82) | 64 (n=50) | 36 (n=82) |

| lsy-6(ot71) | 0 (n=25) | 100 (n=43) | 0 (n=25) | 100 (n=43) |

| lsy-6(ot71); lsy-9(ot85)‡ | 22 (n=52) | nd | 21 (n=52) | nd |

| lsy-6(ot71); lsy-9(ok631)§ | 67 (n=60) | 43 (n=61) | 67 (n=60) | 55 (n=61) |

| die-1(ot26) | 0 (n=50) | 100 (n=50) | 0 (n=50) | 100 (n=50) |

| die-1(ot26); lsy-9(ot85)‡ | 0 (n=34) | nd | 0 (n=34) | nd |

| die-1(ot26); lsy-9(ok631)§ | nd | 100 (n=30) | nd | 100 (n=30) |

| cog-1(ot123) | nd | 100 (n=50) | nd | 100 (n=50) |

| cog-1(ot123); lsy-9(ok631)§ | nd | 56 (n=105) | nd | 74 (n=105) |

nd, not determined.

Transgene used was otls114 (lim-6prom::gfp).

Transgene used was ntls1 (gcy-5prom::gfp).

ceh-36::rfp (otls151) is in the background and only those animals that showed normal ceh-36::rfp expression were scored. Animals showed consistent numbers for L1 and adult scoring. L1 numbers are presented.

che-1::mCherry (otls217) is in the background and only those animals that showed normal che-1::mCherry expression were scored. These animals were scored as L1s due to lethality of ok631

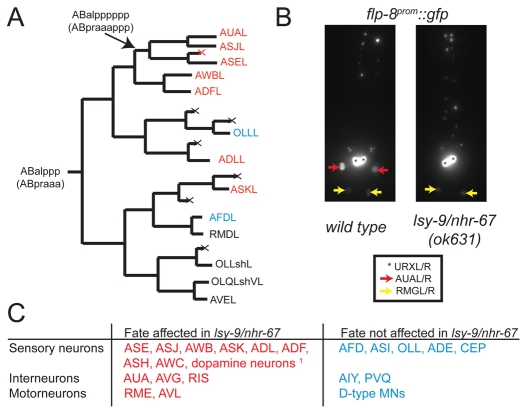

lsy-9 affects the identity of many distinct neuron types

We also investigated whether the effect of lsy-9 is restricted to the ASE neurons or extends to lineally related cells. We examined neuron-type-specific fate markers for a number of different neuronal lineages that emanate from the ABalppp neuroblast, which generates ASEL and 11 other neurons, plus two glial-like cells (Fig. 4A). We found that the expression of fate markers for the neurons closely related to ASE (sister, cousins) was affected (Fig. 4A,B; see Table S1 in the supplementary material). A subset of more distally related neurons was also affected, whereas several other neuron classes were not (Fig. 4A,C; see Table S1 in the supplementary material). We extended this fate marker analysis to a variety of distinct neuron classes throughout the AB lineage (which generate >90% of the C. elegans nervous system) and found that lsy-9 affects the development of 13 out of the 22 neuron classes tested (see Table S1 in the supplementary material). There appears to be no common theme in the type of neurons affected. Defects were observed in sensory, inter- and motoneurons (Fig. 4C). Affected neurons do not fall into a specific neurotransmitter class and affected neurons do not derive from a single common lineage branch. However, many of the cells affected were sister or cousin cells (Figs 4, 6), which suggests that lsy-9 might affect the identity of the neuroblasts that generate them. This notion conforms to the expression pattern of lsy-9, as described further below.

Fig. 4.

lsy-9/nhr-67 broadly affects neuronal fate. (A) Lineage diagram of the ABalppp neuroblast. Neurons whose fate was affected in lsy-9/nhr-67 mutants are indicated in red, those unaffected are in blue, and those untested are in black. See Materials and methods for fate markers used. (B) Representative image of a fate marker lost in lsy-9/nhr-67 mutants. The transgene used to visualize AUA is flp-8prom::gfp (=ynIs2022). ynIs2022 is normally expressed in three cell types: URX, AUA and RMG. nhr-67 mutants specifically affect flp-8 expression in AUA (L/R; red arrows). For quantification, see Table S1 in the supplementary material. (C) Summary of all neuronal fates tested in lsy-9/nhr-67 mutant background. 1The dopamine neuron marker was expressed ectopically in unidentified cells. For markers and alleles used and penetrance of defects, see Table S1 in the supplementary material.

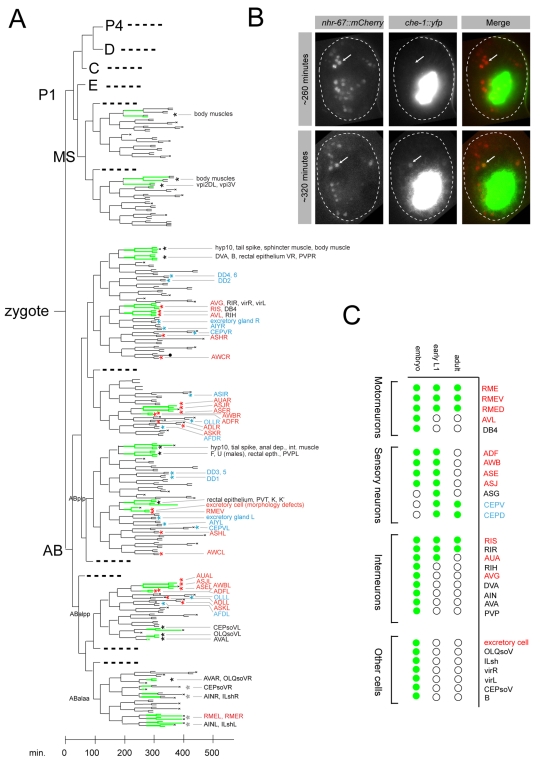

Fig. 6.

Expression and function of nhr-67. (A) Lineage origin of nhr-67-expressing cells. nhr-67 expression is indicated by green lines. Lines begin at the earliest point at which expression was detected within that lineage. Cell identities were determined using 4D microscopy and SIMI software (see Materials and methods). Lineage branches not leading to nhr-67-expressing cells are represented by dotted lines. Asterisks denote cells for which we detected (red) or did not detect (blue) defects in fate marker expression in nhr-67 mutants. Black asterisks denote nhr-67-expressing cells for which fate markers were not tested. `x' indicates apoptotic cell death. (B) nhr-67 is expressed earlier than che-1 in the ASE lineage. The two rows are pictures of two genotypically identical (otEx3362, otIs188) embryos; pictures were taken at different developmental stages. First column shows red-filtered fluorescence, second column shows yellow-filtered fluorescence and third column is the merged product. Arrows indicate ASE; minutes indicate time postfertilization at 20°C. The observed temporal expression patterns were confirmed in 14 out of 14 scored embryos. (C) nhr-67 expression (green dots) is transient in some, but maintained in other, cells. Cells shown in A are depicted here. Color coding of cell names is as in A.

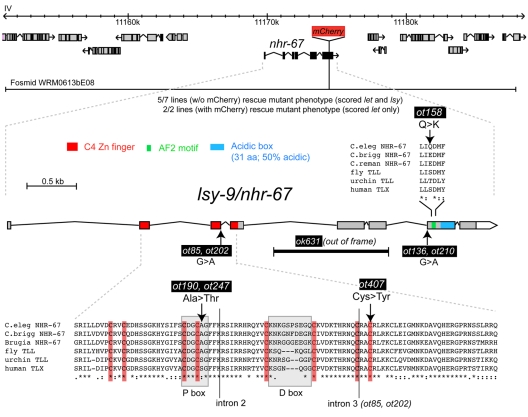

lsy-9 is allelic to the Tailless-related orphan nuclear receptor nhr-67

We mapped ot85 to a small chromosomal interval on linkage group 4. Transformation rescue experiments revealed rescue of lsy-9 mutants with a single fosmid containing 11 predicted genes (Fig. 5). One gene on the fosmid is the orphan nuclear hormone receptor nhr-67, first identified by a genome-wide sequence analysis of nuclear hormone receptor genes (Sluder et al., 1999). Sequencing all available lsy-9 alleles, we found mutations in the coding region of nhr-67 in all mutant strains (Fig. 5). Moreover, a deletion allele generated by the Oklahoma C. elegans knockout consortium (kindly provided by R. Barstead), as well as RNAi directed against nhr-67, recapitulated the lsy-9 mutant phenotype (Table 1; data not shown). We conclude that lsy-9 is nhr-67, and from here on refer to this gene as nhr-67.

Fig. 5.

Cloning of lsy-9/nhr-67. The chromosomal location of lsy-9/nhr-67, the fosmid used for transformation rescue and expression pattern analysis, and the location of individual mutant alleles are indicated. An nhr-67::mCherry fusion was created using recombineering into the rescuing fosmid. Alleles with the same molecular identity were independently isolated.

Reciprocal BLAST searches, phylogenetic analysis and specific sequence features show that NHR-67 is an ortholog of the fly Tailless and the vertebrate TLX transcription factors (Fernandes and Sternberg, 2007; Sluder et al., 1999). Several mutant alleles, the first yet described for nhr-67, illustrate the importance of individual domains of NHR-67 (Fig. 5). Besides a mutation in a Zn-coordinating Cys residue in the DNA-binding C4-type zinc-finger domain, one allele, ot190, contains a missense mutation that affects a residue in the P-box, a crucial component of DNA-binding specificity (Yu et al., 1994). Another missense mutation, ot158, affects the so-called AF2 motif, which is involved in transcriptional activation in other nuclear hormone receptors (Durand et al., 1994) (Fig. 5). It was this mutation that resulted specifically in a loss of ASEL/ASER asymmetry (class I `2 ASEL' phenotype), without affecting the bilateral specification of ASE (Table 1).

The deletion allele provided by the knockout consortium, ok631, results in an out-of-frame deletion of C-terminal exons and might destabilize the whole message. This allele is similar in severity to the other five class V alleles, i.e. it produces a mixed class I (`2 ASEL neurons') and class III (`no ASE neuron') phenotype. In contrast to other alleles, however, ok631 animals are inviable, with death occurring at a range of different stages from post-gastrulation embryos to the first larval (L1) stage. This pleiotropy could be rescued by the nhr-67-containing fosmid (data not shown). Postembryonic death is likely to be caused, at least in part, by dysfunction of the excretory system, as at least one cell of the excretory system, the excretory canal cell, displayed cystic phenotypes (see Fig. S3 in the supplementary material), which is reminiscent of other excretory canal cell mutants (Buechner et al., 1999).

None of the initially identified nhr-67 alleles (ot85, ot136, ot158, ot190, ot202, ot210), nor the deletion allele, is a definitive molecular null allele. The ASE phenotype of the canonical ot85 allele was not enhanced by RNAi against nhr-67 (using a sensitized nre-1 lin-15b; nhr-67(ot85) strain) or by placing ot85 over a deficiency (data not shown), which is consistent with ot85 being a very strong loss-of-function allele. To further explore the null allele issue, we also undertook a non-complementation screen for additional nhr-67 alleles (see Materials and methods), isolating a mutant allele, ot407, in one of the Zn co-ordinating Cys residues of the C4 zinc-finger domain. Like ok631, ot407 animals arrest as embryos or L1, yet their ASE phenotype is no more severe than that of other available strong loss-of-function mutants.

Expression pattern of nhr-67

How does the expression pattern of nhr-67 fit with the multiple roles of nhr-67 in ASE development? Previously described nhr-67 reporter genes did not incorporate the full nhr-67 locus and therefore provided no rescuing gene activity (Fernandes and Sternberg, 2007; Gissendanner et al., 2004). We engineered the mCherry coding region into the last exon of nhr-67 within the context of a ∼40-kb fosmid that contains the nhr-67 locus and 5 genes upstream and downstream of the nhr-67 fosmid using bacterial recombineering. The resulting nhr-67::mCherry reporter rescues both the ASE phenotype and larval arrest phenotype of nhr-67(ok631) mutants (7 out of 9 transgenic lines).

Within the ASEL/R generating lineages, nhr-67::mCherry was first observed in the grandmother cells of ASEL and ASER. Those grandmother cells divide twice more to yield the respective ASE neuron and a sibling cell that undergoes programmed cell death (Sulston et al., 1983) (Fig. 6A). To compare nhr-67::mCherry expression with the onset of che-1 expression, we used the che-1::yfp fosmid described above. Transgenic animals that co-express a functional nhr-67::mCherry reporter and a functional che-1::yfp reporter revealed that nhr-67 precedes che-1 expression (Fig. 6B). Consistent with a role of nhr-67 upstream of che-1, we found that nhr-67 expression is unaffected in che-1 mutants (data not shown). nhr-67 expression was maintained in the ASEL and ASER neurons until the first larval stage after which it became undetectable, whereas che-1 expression was maintained throughout the life of the animal. In spite of its genetically deduced role in asymmetric gene expression in ASEL and ASER, nhr-67 expression is bilaterally symmetric in ASEL and ASER.

Apart from cells in the neuroblast lineage that generate ASE, nhr-67::mCherry was expressed in multiple other neuroblast lineages in the developing embryo. Expression was usually observed in the grandmother or mother of a neuron, but not earlier (Fig. 6A). Within the ASEL and ASER-generating lineage branches, nhr-67 was expressed in neuroblasts that generate closely or distantly related cousins of ASEL and ASER and this expression was highly consistent with defects observed in those lineages. For example, the sister neuroblast of the ASE-generating neuroblast creates the AUA and ASJ neurons and it expressed nhr-67 (Fig. 6). Both AUA and ASJ failed to undergo the normal differentiation program in nhr-67 mutants (Fig. 4; see Table S1 in the supplementary material). The cousin of the ASE-mother cell generates the AWB and ADF sensory neurons. nhr-67 was expressed in these cells and its loss resulted in differentiation defects, as assessed by examining the serotonergic fate of ADF and chemoreceptor expression in AWB. These differentiation defects could be explained by nhr-67 regulating expression of the LIM homeobox gene lim-4 (see Table S1 in the supplementary material), a regulator of ADF and AWB cell fate (Sagasti et al., 1999; Zheng et al., 2005). However, nhr-67 function extends beyond regulating lim-4, because the partially penetrant loss of ADF fate, as measured by tph-1 expression, in lim-4 null mutants was enhanced by nhr-67 (see Table S1 in the supplementary material).

In late stage embryos, a few other, postmitotic neurons started to express nhr-67 (Fig. 6C). Embryonic nhr-67 expression was not restricted to the nervous system, but was observed in a small subset of mesodermal and hypodermal cells (Fig. 6A). No expression was detected in endodermal cells or the germ line. Consistent with its excretory canal cell mutant phenotype (see Fig. S3 in the supplementary material), nhr-67 was expressed in the excretory canal cell.

Postembryonically, nhr-67 expression persisted only in a few neurons in the head ganglia until the first larval stage and faded shortly thereafter in most, but not all, of these neurons, with expression persisting through adulthood only in the CEPD/V, RMED/V, AVL and RIS neurons (Fig. 6C). During mid-larval development, nhr-67 was transiently and dynamically expressed in the AC cells of the vulva, as previously described (Fernandes and Sternberg, 2007). Expression was also found in the VU cells and somatic gonad, but not in vulA, vulB or vulC, as has been previously shown with smaller reporter constructs that might not contain all of the relevant cis-regulatory information (Fernandes and Sternberg, 2007).

The cellular expression profile of nhr-67 largely overlapped with the profile of cellular defects (Fig. 4C, Fig. 6A; see also Table S1 in the supplementary material), with some exceptions. For example, even though the AWC neurons failed to show their normal pattern of cell fate marker expression, a phenotype that was rescued by re-introducing wild-type copies of nhr-67 (data not shown), we could not detect expression of nhr-67 in AWC. This might be due to a non-autonomous role of nhr-67 or might be a reflection of technical limitations in observing very low levels of nhr-67 expression. Taken together, the mutant phenotypic analysis and the expression pattern analysis both support the notion that nhr-67 acts in a specific subset of diverse neuron types to control their correct development.

nhr-67 controls ASE asymmetry by directly activating cog-1 expression

Having identified both the molecular identity and the expression pattern of nhr-67, we revisited the question of the bimodal activity of nhr-67 in ASE development. As nhr-67 expression precedes and is required for che-1 expression (but not vice versa), nhr-67 is likely to activate che-1 expression, either directly or indirectly. But how does the bilateral expression of nhr-67 in both ASEL and ASER fit with its function as an ASER fate inducer, which, as we have shown, is genetically required for cog-1 function? We examined the sequence of the cog-1 promoter and found a phylogenetically conserved, consensus binding site for Tailless-type orphan nuclear receptor (NR2E motif) (DeMeo et al., 2008; Yu et al., 1994) embedded in between two binding sites for the CHE-1 transcription factor (`ASE motif') that are required to induce cog-1 expression in ASE (O'Meara et al., 2009) (Fig. 7A). Deletion analysis demonstrated that the NR2E motif is required for the initial, embryonic expression of cog-1 in ASE (Fig. 7B). Moreover, yeast one-hybrid analysis showed that NHR-67 can directly bind to the cog-1 promoter and that this binding is dependent on the presence of the NR2E motif (Fig. 7C). The function of NHR-67 as an activator of cog-1 expression is consistent with the genetic data described above, in which we have shown that nhr-67 suppresses the cog-1(ot123) gain-of-function allele. In this allele, owing to a deletion of its miRNA-controlled 3′UTR, endogenous cog-1 is ectopically expressed in ASEL, and its ASER fate-inducing effect in ASEL is dependent on the activation of its transcription by nhr-67. Taken together, bilaterally expressed nhr-67 exerts its function in controlling ASE laterality by activating the ASER fate inducer cog-1. This function occurs postmitotically after the birth of the ASE neurons and is subsequent to the earlier role of inducing che-1 expression, which happens in the mother of ASE.

Fig. 7.

nhr-67 controls cog-1 expression. (A) Genomic representation of the intergenic region between cog-1 and the immediate upstream gene. Numbers next to sequences indicate positions relative to the ATG start codon of the longer cog-1 isoform. Dotted lines bracket the 6-kb region sufficient to drive cog-1 expression in ASE (O'Meara et al., 2009). (B) Reporter constructs show that the NR2E motif is required for the initiation of cog-1 expression. Three independent transgenic lines were isolated and scored for each construct in two-fold embryos (when cog-1 expression is first observed) and in young adults (not shown). Arrows indicate the position of the ASER cell body. Black asterisks indicate intestinal gfp expression resulting from the co-injection marker elt-2::gfp. Deletion of the NR2E motif does not affect adult expression of cog-1, which is likely to be due to cog-1 autoregulation. (C) Yeast one-hybrid interaction between NHR-67 and the cog-1 promoter. cog-1promD is a 1.8-kb fragment of the cog-1 promoter region that contains the NR2E motif, and cog-1promD-nhr-67site del is the same fragment but with the NR2E site deleted. Thirty-two transformants were selected for each transformation and plated on SC -Trp -His with or without 40 mM 3AT. Representatives for each are shown here. All transformants grew on media lacking 3AT. Scoring for strains plated on 40 mM 3AT is as follows: cog-1promD alone, 0/32 grew; cog-1promD and AD-NHR-67, 25/32 grew; cog-1promD-nhr-67site del alone, 0/32 grew; cog-1promD-nhr-67site del and AD-NHR-67, 0/32 grew. (D) Summary of nhr-67 function.

DISCUSSION

nhr-67 regulates neuronal identity on several different levels

We have delineated here a set of cellular functions of the C. elegans Tailless/TLX ortholog NHR-67 in controlling neuronal development. nhr-67 controls the identity of several different neuronal classes. There is no obvious unifying common theme in the function (sensory versus inter versus motoneurons), neurotransmitter identity, position or morphology of the neurons affected. The cellular fate markers affected by nhr-67 also tend to be diverse. Some neurons are related by lineage and, based on the nhr-67 expression pattern, nhr-67 might affect the identity of the neuroblast from which these affected neurons are derived.

Through their placement in a complex network of regulatory interactions, the ASE gustatory neurons have served as our model to better understand nhr-67 function (Fig. 7D). We find that nhr-67 exhibits a unique phenotype characterized by multiple roles in the ASE developmental pathway. In both left and right ASEs, nhr-67 is required for the induction of ASE fate, as it positively regulates embryonic expression of the ASE selector gene, che-1. che-1 expression is turned on shortly after nhr-67 expression can be observed in the ASE mother cell, which would be consistent with a direct role of NHR-67 in activating the che-1 promoter. The che-1 promoter contains no perfect match to the AAGTCA core binding sequence of TLX-type transcription factors [which was also found to bind NHR-67 in a heterologous yeast system (DeMeo et al., 2008)], but it is possible that NHR-67 might bind to a phylogenetically conserved derivative of this sequence in the che-1 promoter (cAGTtA), which we find to be required for embryonic induction of che-1 expression (our unpublished data). The che-1 promoter also contains several other conserved motifs that are required for the initiation of che-1 expression (our unpublished data), suggesting that che-1 integrates several regulatory inputs, of which NHR-67 is likely to be one. The partially penetrant effects of a loss of NHR-67 on che-1 expression are consistent with other regulatory inputs into the che-1 locus.

The function of nhr-67 in controlling the induction of ASE fate extends beyond regulating che-1 function (Fig. 7D). In che-1 null mutants, ASE loses its specific neuronal identity, but still persists as a sensory neuron, as indicated by the unaffected expression of ciliated markers and by its overall morphology, as assessed by the ability of ASE to take up the dye DiI and by electron microscopy (Lewis and Hodgkin, 1977; Uchida et al., 2003). By contrast, in nhr-67 mutants, ASE fails to take up DiI, fails to express a ciliated marker gene and displays morphological defects. Pan-neuronal features of ASE appear to be unaffected by nhr-67. These findings reveal a regulatory hierarchy in which nhr-67 couples the adoption of two identity-defining features of ASE (Fig. 7D). nhr-67 controls broad, pan-sensory features of ASE, but then also induces the expression of a terminal selector gene that assigns a unique identity to ASE that distinguishes it from other sensory neurons. The lim-4 LIM homeobox gene is a putative terminal selector of AWB fate (Sagasti et al., 1999), and its regulation by nhr-67 might indicate that nhr-67 activity in neuroblasts generally involves the initiation of terminal selector gene expression, which in turn drives the `nuts-and-bolts' gene expression programs that define individual neuron types (Hobert, 2008).

After induction of ASE bilateral fate by promoting che-1 expression, nhr-67 plays a further role in inducing ASER and repressing ASEL fate, a decision made long after the birth of the ASE neurons and therefore temporally `downstream' of the earlier role in ASE fate induction in the ASE mother cell. In this additional function, NHR-67 cooperates with the ASE fate-inducer CHE-1; both proteins act through defined cis-regulatory elements to activate the asymmetry regulator cog-1, an ASER fate inducer. Bilaterally expressed CHE-1 and NHR-67 transcriptionally activate cog-1 in both ASEL and ASER, yet COG-1 protein expression is inhibited in ASEL post-transcriptionally by the miRNA lsy-6 (Johnston and Hobert, 2003). Transcription factors therefore produce a transcriptional program that is refined by miRNA function.

Taken together, nhr-67 acts at distinct steps in ASE specification. Reiterative uses of a transcription factor in neuronal lineages comparable to the one shown here for nhr-67 tend to be hard to identify, often because earlier functions of a transcription factor might mask its later roles. It was only through the partial penetrance of the earlier role of nhr-67 that we were able to uncover its later role. Similarly separable functions of neuronal identity determinants have been described for the unc-86 homeobox gene and the lin-32 bHLH gene (Duggan et al., 1998; Portman and Emmons, 2000), and might reflect a common theme of transcription factor activity controlling neuronal development at several distinct steps.

Diverse roles of nhr-67 and other NR2E nuclear receptors

The function of nhr-67 is not restricted to the nervous system. In the developing vulva, nhr-67 controls the identity of several vulval cell types, acting in conjunction with several distinct regulatory factors (Fernandes and Sternberg, 2007). As is the case in the ASE neurons, nhr-67 acts within the context of a bistable system in which two factors, cog-1 and nhr-67, cross-inhibit the activity of one another to generate distinct vulval cell types. The interaction of nhr-67 and cog-1 in ASE neurons is, however, strikingly distinct from the interaction in the vulva, because in ASE nhr-67 activates cog-1, whereas in the vulva it inhibits its expression, presumably because it co-operates with factors other than CHE-1 to control cog-1 expression. Also, in contrast to in the vulva, cog-1 has no comparable transcriptional impact on nhr-67 in ASER. cog-1 and nhr-67 therefore are striking examples of regulatory factors wired together in distinct configurations in different cell types.

A nuclear receptor closely related to NHR-67, FAX-1, also controls neuronal identity and morphology in C. elegans (Much et al., 2000; Wightman et al., 2005). Similarly, its vertebrate homolog, PNR, promotes proper photoreceptor cell fate specification (Haider et al., 2000). In other species, the orthologs of NHR-67, Drosophila Tailless and vertebrate TLX, are also involved in various aspects of neuronal development. Tailless promotes the formation of large regions of the Drosophila brain by activating expression of the proneural gene lethal of scute, rendering the cells competent to form neural precursors (Strecker et al., 1986; Younossi-Hartenstein et al., 1997). Tailless mutants result in the loss of several brain regions owing to a lack of neuroblast production. Similarly, vertebrate TLX is a key regulator of the cell cycle in neuronal stem cell populations. Tlx-/- mice are unable to maintain an undifferentiated population of stem cells and, consequently, lose several parts of outer brain regions (Miyawaki et al., 2004; Roy et al., 2004; Shi et al., 2004; Stenman et al., 2003). Our finding of NHR-67 acting at several independent steps late in neuronal differentiation suggests that Tailless-like proteins in other organisms may also have late differentiation roles that might have been obscured by their earlier roles in neuronal precursor formation.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://dev.biologists.org/cgi/content/full/136/17/2933/DC1

Supplementary Material

We thank M. O'Meara for providing otIs158 and ot190, E. Flowers for ot247, V. Marrero for yeast manipulation assistance, M. Walhout for the yeast one-hybrid strain, Q. Chen for expert DNA injection and members of the Hobert lab for comments on the manuscript. We acknowledge funding by the NIH to O.H. (R01NS039996-05, R01NS050266-03) and to S.S. (NS054540-01). B.T. is funded by the Francis Goelet Fellowship. O.H. is an Investigator of the HHMI. Deposited in PMC for release after 6 months.

References

- Brenner, S. (1974). The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77, 71-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buechner, M., Hall, D. H., Bhatt, H. and Hedgecock, E. M. (1999). Cystic canal mutants in Caenorhabditis elegans are defective in the apical membrane domain of the renal (excretory) cell. Dev. Biol. 214, 227-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, S., Johnston, R. J., Jr and Hobert, O. (2003). A transcriptional regulatory cascade that controls left/right asymmetry in chemosensory neurons of C. elegans. Genes Dev. 17, 2123-2137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMeo, S. D., Lombel, R. M., Cronin, M., Smith, E. L., Snowflack, D. R., Reinert, K., Clever, S. and Wightman, B. (2008). Specificity of DNA-binding by the FAX-1 and NHR-67 nuclear receptors of Caenorhabditis elegans is partially mediated via a subclass-specific P-box residue. BMC Mol. Biol. 9, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deplancke, B., Dupuy, D., Vidal, M. and Walhout, A. J. (2004). A gateway-compatible yeast one-hybrid system. Genome Res. 14, 2093-2101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolphin, C. T. and Hope, I. A. (2006). Caenorhabditis elegans reporter fusion genes generated by seamless modification of large genomic DNA clones. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, e72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggan, A., Ma, C. and Chalfie, M. (1998). Regulation of touch receptor differentiation by the Caenorhabditis elegans mec-3 and unc-86 genes. Development 125, 4107-4119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand, B., Saunders, M., Gaudon, C., Roy, B., Losson, R. and Chambon, P. (1994). Activation function 2 (AF-2) of retinoic acid receptor and 9-cis retinoic acid receptor: presence of a conserved autonomous constitutive activating domain and influence of the nature of the response element on AF-2 activity. EMBO J. 13, 5370-5382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etchberger, J. F., Lorch, A., Sleumer, M. C., Zapf, R., Jones, S. J., Marra, M. A., Holt, R. A., Moerman, D. G. and Hobert, O. (2007). The molecular signature and cis-regulatory architecture of a C. elegans gustatory neuron. Genes Dev. 21, 1653-1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etchberger, J. F., Flowers, E. B., Poole, R. J., Bashllari, E. and Hobert, O. (2009). Cis-regulatory mechanisms of left/right asymmetric neuron-subtype specification in C. elegans. Development 136, 147-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, J. S. and Sternberg, P. W. (2007). The tailless ortholog nhr-67 regulates patterning of gene expression and morphogenesis in the C. elegans vulva. PLoS Genet. 3, e69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gengyo-Ando, K. and Mitani, S. (2000). Characterization of mutations induced by ethyl methanesulfonate, UV, and trimethylpsoralen in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 269, 64-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gissendanner, C. R., Crossgrove, K., Kraus, K. A., Maina, C. V. and Sluder, A. E. (2004). Expression and function of conserved nuclear receptor genes in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 266, 399-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haider, N. B., Jacobson, S. G., Cideciyan, A. V., Swiderski, R., Streb, L. M., Searby, C., Beck, G., Hockey, R., Hanna, D. B., Gorman, S. et al. (2000). Mutation of a nuclear receptor gene, NR2E3, causes enhanced S cone syndrome, a disorder of retinal cell fate. Nat. Genet. 24, 127-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobert, O. (2005). Specification of the nervous system. WormBook, www.wormbook.org. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hobert, O. (2006). Architecture of a MicroRNA-controlled gene regulatory network that diversifies neuronal cell fates. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 71, 181-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobert, O. (2008). Regulatory logic of neuronal diversity: terminal selector genes and selector motifs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 20067-20071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin, J. and Doniach, T. (1997). Natural variation and copulatory plug formation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 146, 149-164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, R. J. and Hobert, O. (2003). A microRNA controlling left/right neuronal asymmetry in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 426, 845-849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, J. A. and Hodgkin, J. A. (1977). Specific neuroanatomical changes in chemosensory mutants of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Comp. Neurol. 172, 489-510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyawaki, T., Uemura, A., Dezawa, M., Yu, R. T., Ide, C., Nishikawa, S., Honda, Y., Tanabe, Y. and Tanabe, T. (2004). Tlx, an orphan nuclear receptor, regulates cell numbers and astrocyte development in the developing retina. J. Neurosci. 24, 8124-8134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Much, J. W., Slade, D. J., Klampert, K., Garriga, G. and Wightman, B. (2000). The fax-1 nuclear hormone receptor regulates axon pathfinding and neurotransmitter expression. Development 127, 703-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Meara, M. M., Bigelow, H., Flibotte, S., Etchberger, J. F., Moerman, D. G. and Hobert, O. (2009). Cis-regulatory mutations in the caenorhabditis elegans homeobox gene locus cog-1 affect neuronal development. Genetics 181, 1679-1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz, C. O., Faumont, S., Takayama, J., Ahmed, H. K., Goldsmith, A. D., Pocock, R., McCormick, K. E., Kunimoto, H., Iino, Y., Lockery, S. et al. (2009). Lateralized gustatory behavior of C.elegans is controlled by specific receptor-type guanylyl cyclases. Curr. Biol. 19, 996-1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce-Shimomura, J. T., Faumont, S., Gaston, M. R., Pearson, B. J. and Lockery, S. R. (2001). The homeobox gene lim-6 is required for distinct chemosensory representations in C. elegans. Nature 410, 694-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole, R. J. and Hobert, O. (2006). Early embryonic programming of neuronal left/right asymmetry in C. elegans. Curr. Biol. 16, 2279-2292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portman, D. S. and Emmons, S. W. (2000). The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors LIN-32 and HLH-2 function together in multiple steps of a C. elegans neuronal sublineage. Development 127, 5415-5426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy, K., Kuznicki, K., Wu, Q., Sun, Z., Bock, D., Schutz, G., Vranich, N. and Monaghan, A. P. (2004). The Tlx gene regulates the timing of neurogenesis in the cortex. J. Neurosci. 24, 8333-8345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruvinsky, I., Ohler, U., Burge, C. B. and Ruvkun, G. (2007). Detection of broadly expressed neuronal genes in C. elegans. Dev. Biol. 302, 617-626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagasti, A., Hobert, O., Troemel, E. R., Ruvkun, G. and Bargmann, C. I. (1999). Alternative olfactory neuron fates are specified by the LIM homeobox gene lim-4. Genes Dev. 13, 1794-1806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarin, S., O'Meara, M. M., Flowers, E. B., Antonio, C., Poole, R. J., Didiano, D., Johnston, R. J., Jr, Chang, S., Narula, S. and Hobert, O. (2007). Genetic screens for Caenorhabditis elegans mutants defective in left/right asymmetric neuronal fate specification. Genetics 176, 2109-2130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnabel, R., Hutter, H., Moerman, D. and Schnabel, H. (1997). Assessing normal embryogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans using a 4D microscope: variability of development and regional specification. Dev. Biol. 184, 234-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y., Chichung Lie, D., Taupin, P., Nakashima, K., Ray, J., Yu, R. T., Gage, F. H. and Evans, R. M. (2004). Expression and function of orphan nuclear receptor TLX in adult neural stem cells. Nature 427, 78-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sluder, A. E., Mathews, S. W., Hough, D., Yin, V. P. and Maina, C. V. (1999). The nuclear receptor superfamily has undergone extensive proliferation and diversification in nematodes. Genome Res. 9, 103-120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenman, J. M., Wang, B. and Campbell, K. (2003). Tlx controls proliferation and patterning of lateral telencephalic progenitor domains. J. Neurosci. 23, 10568-10576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strecker, T. R., Kongsuwan, K., Lengyel, J. A. and Merriam, J. R. (1986). The zygotic mutant tailless affects the anterior and posterior ectodermal regions of the Drosophila embryo. Dev. Biol. 113, 64-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston, J. E., Schierenberg, E., White, J. G. and Thomson, J. N. (1983). The embryonic cell lineage of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 100, 64-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, H., Thiele, T. R., Faumont, S., Ezcurra, M., Lockery, S. R. and Schafer, W. R. (2008). Functional asymmetry in Caenorhabditis elegans taste neurons and its computational role in chemotaxis. Nature 454, 114-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swoboda, P., Adler, H. T. and Thomas, J. H. (2000). The RFX-type transcription factor DAF-19 regulates sensory neuron cilium formation in C. elegans. Mol. Cell 5, 411-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tursun, B., Cochella, L., Carrera, I. and Hobert, O. (2009). A toolkit and robust pipeline for the generation of fosmid-based reporter genes in C. elegans. PLoS ONE 4, e4625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida, O., Nakano, H., Koga, M. and Ohshima, Y. (2003). The C. elegans che-1 gene encodes a zinc finger transcription factor required for specification of the ASE chemosensory neurons. Development 130, 1215-1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wightman, B., Ebert, B., Carmean, N., Weber, K. and Clever, S. (2005). The C. elegans nuclear receptor gene fax-1 and homeobox gene unc-42 coordinate interneuron identity by regulating the expression of glutamate receptor subunits and other neuron-specific genes. Dev. Biol. 287, 74-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younossi-Hartenstein, A., Green, P., Liaw, G. J., Rudolph, K., Lengyel, J. and Hartenstein, V. (1997). Control of early neurogenesis of the Drosophila brain by the head gap genes tll, otd, ems, and btd. Dev. Biol. 182, 270-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, R. T., McKeown, M., Evans, R. M. and Umesono, K. (1994). Relationship between Drosophila gap gene tailless and a vertebrate nuclear receptor Tlx. Nature 370, 375-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S., Avery, L., Baude, E. and Garbers, D. L. (1997). Guanylyl cyclase expression in specific sensory neurons: a new family of chemosensory receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 3384-3387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X., Chung, S., Tanabe, T. and Sze, J. Y. (2005). Cell-type specific regulation of serotonergic identity by the C. elegans LIM-homeodomain factor LIM-4. Dev. Biol. 286, 618-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.