Summary

PTF1-J is a trimeric transcription factor complex essential for generating the correct balance of GABAergic and glutamatergic interneurons in multiple regions of the nervous system, including the dorsal horn of the spinal cord and the cerebellum. Although the components of PTF1-J have been identified as the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) factor Ptf1a, its heterodimeric E-protein partner, and Rbpj, no neural targets are known for this transcription factor complex. Here we identify the neuronal differentiation gene Neurog2 (Ngn2, Math4A, neurogenin 2) as a direct target of PTF1-J. A Neurog2 dorsal neural tube enhancer localized 3′ of the Neurog2 coding sequence was identified that requires a PTF1-J binding site for dorsal activity in mouse and chick neural tube. Gain and loss of Ptf1a function in vivo demonstrate its role in Neurog2 enhancer activity. Furthermore, chromatin immunoprecipitation from neural tube tissue demonstrates that Ptf1a is bound to the Neurog2 enhancer. Thus, Neurog2 expression is directly regulated by the PTF1-J complex, identifying Neurog2 as the first neural target of Ptf1a and revealing a bHLH transcription factor cascade functioning in the specification of GABAergic neurons in the dorsal spinal cord and cerebellum.

Keywords: bHLH transcription factor, Cerebellum development, Dorsal neural tube development, Gene regulation, Spinal cord development, Mouse

INTRODUCTION

Cascades of transcription factor function combined with elaborate feedback and feedforward mechanisms are fundamental to generating nervous system circuitry. These processes ensure the generation of the appropriate balance of specific neuronal subtypes. In the development of the dorsal spinal cord, a transcription factor network is beginning to be defined that regulates the balance of inhibitory and excitatory neurons generated from progenitor cells. Central to this network are transcription factors from the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) and homeodomain (HD) class of proteins (Cheng et al., 2005; Cheng et al., 2004; Glasgow et al., 2005; Gowan et al., 2001; Gross et al., 2002; Helms et al., 2005; Kriks et al., 2005; Mizuguchi et al., 2006; Müller et al., 2002; Wildner et al., 2006). The bHLH factor Ptf1a is particularly important for promoting GABAergic inhibitory neurons while suppressing glutamatergic excitatory neurons in both the dorsal horn of the spinal cord and the cerebellum (Glasgow et al., 2005; Hori et al., 2008; Hoshino et al., 2005; Pascual et al., 2007). Whereas it has been shown that Ptf1a is required for expression of the HD factors Pax2, Lhx1 and Lhx5, and suppression of Tlx3 and Lmx1b, no direct downstream targets of Ptf1a have been identified in the nervous system. We demonstrate that the gene encoding the bHLH factor Neurog2 is a direct target of Ptf1a.

Ptf1a is a component of a unique transcription complex called PTF1-J that includes two bHLH factors, Ptf1a and an E-protein such as Tcfe2a-E12, and Rbpj (Beres et al., 2006; Hori et al., 2008; Masui et al., 2007). Ptf1a is the tissue-specific component of the PTF1-J complex, and thus its pattern of expression defines domains of PTF1-J function. In mouse embryos between embryonic days (E) 10.5 and 13.5, Ptf1a is largely restricted to the dorsal neural tube from the hindbrain to the tail, and to the pancreatic anlage (Glasgow et al., 2005; Obata et al., 2001). Other domains of expression include the embryonic retina in progenitors to amacrine and horizontal neurons and a subset of cells in the developing hypothalamus (Fujitani et al., 2006; Glasgow et al., 2005; Nakhai et al., 2007). Within the caudal neural tube, Ptf1a is restricted to the progenitor domain that gives rise to dI4 and dILA interneurons, which contribute to the GABAergic inhibitory neural network in the dorsal horn (Glasgow et al., 2005) (Fig. 1B). The requirement for Ptf1a in the generation of many of these cell types has been demonstrated in mice and humans mutant for the gene (Dullin et al., 2007; Fujitani et al., 2006; Glasgow et al., 2005; Hoshino et al., 2005; Kawaguchi et al., 2002; Nakhai et al., 2007; Pascual et al., 2007; Sellick et al., 2004; Yamada et al., 2007).

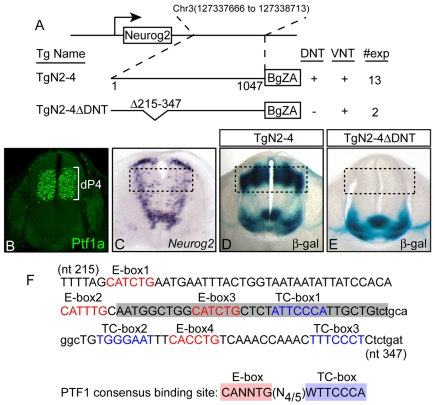

Fig. 1.

A dorsal-neural-tube-specific enhancer for Neurog2. (A,D,E) Diagram of the Neurog2 gene and transgenic constructs (A) showing the location on mouse chromosome 3 of the 3′ enhancer (TgN2-4) that directs expression of a lacZ reporter (BgZA) to both a dorsal (DNT) and a ventral (VNT) region in the E11.5 neural tube of transgenic mice (β-gal stained neural tube section shown in D) (Simmons et al., 2001), and a deletion that specifically disrupts the dorsal pattern (TgN2-4ΔDNT; β-gal-stained neural tube section shown in E). # exp is the number of independently derived transgenic embryos analyzed that expressed the transgene. (B) Ptf1a immunofluorescence on a transverse section of the neural tube illustrates Ptf1a is restricted to and defines the dorsal progenitor domain 4 (dP4) that will give rise to dorsal interneuron population 4 (dI4) (Glasgow et al., 2005). (C) The complex pattern of endogenous Neurog2 in the neural tube is shown by mRNA in situ hybridization. The dashed boxes in C-E indicate the Neurog2 expression domain that is the focus of this study. (F) Mouse sequence (133 bp) from the Neurog2 3′ enhancer that contains the dorsal-specific regulatory region deleted in TgN2-4ΔDNT. The nucleotides conserved between mouse and human are shown in uppercase letters, and non-conserved nucleotides are in lowercase. E-boxes (red), TC-boxes (blue) and the PTF1-binding site (shaded) that were tested in transgenic mouse assays (see Fig. 6) are indicated.

The PTF1-binding site is unique in that it contains both an E-box for bHLH heterodimer binding, and a TC-box for Rbpj binding (Beres et al., 2006; Masui et al., 2007). This bipartite consensus sequence was defined for a form of PTF1 (PTF1-L) that contains the Rbpj homolog Rbpj-l. PTF1-L controls pancreas specific targets in the adult pancreas (Beres et al., 2006). We identify a sequence similar to the PTF1 consensus site in a 3′ regulatory enhancer for Neurog2. The bHLH factor Neurog2 (Ngn2, Math4A) functions in neuronal differentiation and is expressed in a precise spatial and temporal pattern during the development of the vertebrate sensory ganglia, spinal cord and brain (Fode et al., 1998; Gradwohl et al., 1996; Kele et al., 2006; Ma et al., 1999; Sommer et al., 1996). We provide evidence that the PTF1-J complex controls Neurog2 transcription in the dorsal neural tube and cerebellum through its 3′ enhancer. Furthermore, we demonstrate that regulation of Neurog2 by Ptf1a in the PTF1-J complex is direct. The identification of direct targets of PTF1-J is the first step in providing mechanistic insight into the transcriptional control generating the balance of inhibitory and excitatory neuronal circuitry.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse strains

Mutant mouse strains have been previously described, including Ascl1null (Mash1null) (Guillemot et al., 1993), Ptf1aCre (p48Cre) (Kawaguchi et al., 2002) used here as the Ptf1a null, and Ptf1aW298A (Masui et al., 2007). Transgenic mice were generated by standard procedures (Brinster et al., 1985) using fertilized eggs from B6D2F1 (C57BL/6×DBA) or B6SJLF1 (C57BL/6J×SJL) crosses. The TgN2-4 transgenes and variants were isolated from vector sequences using standard procedures and injected into the pronucleus of fertilized mouse eggs at 1-3 ng/μl in 10 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 0.1 mM EDTA. Transgenic embryos were identified by PCR for the lacZ gene using yolk sac DNA. Embryos were staged based on assumed copulation halfway through the dark cycle, designated E0. All procedures on animals follow NIH Guidelines and were approved by the UT Southwestern Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

DNA constructs

TgN2-4 transgene was previously published and contains a 1047 bp enhancer located 226 bp 3′ of the Neurog2 coding sequence stop codon, and when paired with a β-globin heterologous basal promoter [in BGZA (Yee and Rigby, 1993)] it directs expression of a lacZ reporter gene to the dorsal neural tube as well as a small ventral neural tube domain at E11.5 in transgenic mice (Simmons et al., 2001). Mutant variations of this transgene were generated by PCR; E-boxes (CANNTG) were mutated to (atNNTG) and TC-boxes (WTTCCCA) were mutated to (WTagaCA). The 4×PTF1 transgene has four copies of the sequence AATGGCTGGCATCTGCTCTATTCCCATTGCTGTCT, which contains a PTF1 consensus sequence (underlined) plus some flanking nucleotides cloned in the 5′ polylinker of the BGZA reporter. The Ptf1a expression construct for the chick electroporations was in the expression vector pMiWIII, as previously described (Hori et al., 2008). All plasmids were sequence verified.

Immunofluorescence and β-gal staining

For immunofluorescence, E11.5 mouse embryos were dissected in ice-cold 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.4, fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 2 hours at 4°C and washed three times in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.4 for 2 hours. Embryos were sunk overnight in 30% sucrose in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.4, embedded in OCT and cryosectioned at 30 μm. All sections of neural tubes were from the upper limb level. Immunofluorescence was performed using the following primary antibodies: chick anti-β-gal (1:250; Abcam), rabbit anti-Pax2 (1:1,000; Zymed), guinea pig anti-Brn3a (Pou4f1 - Mouse Genome Informatics) (1:10,000; generated for this study using GST-Brn3a from E. Turner, UCSD), guinea pig anti-Ptf1a (1:10,000) (Hori et al., 2008) and mouse anti-Neurog2 (1:10; D. Anderson, Caltech). Fluorescence conjugated species-specific secondary antibodies were used from Molecular Probes. Fluorescence imaging was carried out on a Bio-Rad MRC 1024 confocal microscope. For each experiment multiple sections from at least three different animals were analyzed.

For β-gal staining, E10.5 embryos or E17.5 brains were dissected in ice-cold 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.4, fixed in 4% formaldehyde and processed in whole mount for β-gal staining as described (Simmons et al., 2001). After imaging, embryos and brains were agarose embedded and vibratome sectioned at 100 μm and mounted on slides for imaging.

Chicken in ovo electroporation

Fertilized White Leghorn eggs were obtained from the Texas A&M Poultry Department (College Station, TX) and incubated at 39°C for 5 days. Solutions of supercoiled plasmid DNA (2 μg/μl) in PBS/0.02% Trypan Blue were injected into the lumen of the closed neural tube at stage HH14-16, and embryos were electroporated as previously described (Timmer et al., 2001). Embryos were harvested 48 hours later, fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 1 hour and processed as above for β-gal staining or for immunofluorescence. Embryos were embedded in OCT, cryosectioned at 30 μm and mounted on slides. Images shown in Fig. 7 are representative of expression seen in more than eight embryos per condition.

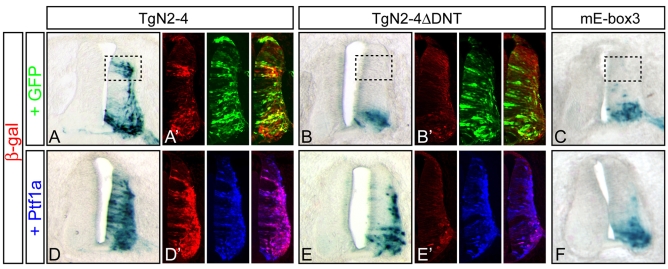

Fig. 7.

Ptf1a induces activity of the Neurog2 3′ enhancer through the PTF1 site. (A-F) TgN2-4, TgN2-4ΔDNT and TgN2-4mE-box3 reporter constructs were electroporated into the chick neural tube at HH14-16 with a control vector (A-C) or with a Ptf1a expression vector (D-F). Embryos were harvested 48 hours later, β-gal stained and sectioned, or processed for immunofluorescence (A′,B′,D′,E′). The activity of each construct mimics that seen in transgenic mouse neural tube. Dashed boxes indicate the specific loss of the dorsal domain of expression in the mutants relative to the wild-type enhancer reporter. Misexpression of Ptf1a along the entire dorsoventral axis results in ectopic β-gal staining in the wild-type enhancer construct (D,D′) but not when the PTF1 site is deleted or mutated (E,E′,F). (A′,B′) Transgene expression (β-gal, red) has restricted expression relative to an electroporation control from a CMV-GFP expression vector (GFP, green). (D′,E′) Ectopic expression of Ptf1a (blue) induces expression from TgN2-4 but not TgN2-4DNT (pink/blue in D′ versus E′).

EMSA analysis

In vitro translated mouse Tcfe2a-E12, mouse Ptf1a, the mutant Ptf1aW298A and human Rbpj proteins were synthesized in vitro using SP6 and T7 TNT Quick Coupled lysate systems (Promega, Madison, WI), and were quantified using 35S-Met according to the manufacturer's directions. TNT lysates were incubated in binding buffer (10 mM Hepes pH 7.9, 4 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 80 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol, 5 mM DTT, 2 μg Poly dI/dC and 6 μg BSA) along with (γ-32P) end-labeled oligo probe (50,000 cpm) in a total volume of 20 μl at 30°C for 30 minutes. Reactions were transferred to ice for 15 minutes before separating on a 4.5% polyacrylamide matrix gel run at 4°C in 1× TGE at 30 mA. The oligonucleotide sequence used for probe contains the predicted PTF1 site from the Neurog2 enhancer 5′-GGCTGGCATCTGCTCTATTCCCATTGCTG-3′ (top strand). The E-box3 and TC-box1 are underlined.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay

Neural tubes were collected from E11.5 mouse embryos and dissociated in PBS at low speed using an IKA model T8.01 probe blender. Formaldehyde was added to a final concentration of 1%, and dissociated tissue was incubated for 10 minutes at room temperature. The fixation reaction was stopped by adding glycine to a final concentration of 0.125 M followed by washing twice with PBS. Nuclei were obtained using a CelLytic NuCLEAR Extraction Kit (Sigma). Chromatin was enzymatically sheared to an average length of 800-1000 bp using Active Motif's ChIP-IT Express Kit. ChIP was performed as described previously using protein-A agarose beads (Upstate) and affinity-purified rabbit anti-Ptf1a antibody (Masui et al., 2007). DNA was purified from each reaction using QIAQuick purification columns (Qiagen) and quantified by qPCR with Fast SYBRGreen mix (ABI). % ChIP efficiency equals [2(Threshold Cycle Input - Threshold Cycle ChIP)] × 1/dilution factor × 100. Data are shown as fold enrichment relative to that for the Mrps15 control. Primers used in qPCR: (A) Control 1.5 kb 5′ of the Neurog2 enhancer PTF1 site forward-CACATCTGGAGCCGCGTAGGTAAGTGTG and reverse-TCACTGCGTCTAGAGCGATGGAG; (B) Neurog2 enhancer PTF1 site forward-CAGGCTGTGGGAATTTCACCTGTC and reverse-GACAATAGGCATTGTGACGAATCTGG; (C) Control 1.7 kb 3′ of the Neurog2 enhancer PTF1 site forward-AATGATGGCCGACTAGACCATCTTCTG and reverse-TCTGCAACCCTATAGGAGGAGCAGCAA; Mrps15 control primers forward-CTGGGACATAGTGGGTGCTT and reverse-GAGCCTAGAGATGGGCTGTG.

RESULTS

A PTF1-binding site is identified in the dorsal neural tube enhancer of Neurog2

The PTF1 trimeric complex binds a 17 bp site that contains both an E-box and a TC-box (Beres et al., 2006) (Fig. 1F). In searching for downstream targets of PTF1, we identified a match to a PTF1-binding site in a previously characterized regulatory region 3′ of the Neurog2 gene (Scardigli et al., 2001; Simmons et al., 2001). The 1047 bp 3′ enhancer (TgN2-4) directs transcription of a lacZ reporter gene to a portion of the Neurog2 pattern in the dorsal neural tube as well as a small ventral domain in transgenic mice (Fig. 1A,D) (Simmons et al., 2001). The PTF1 site was identified within a 133 bp sequence highly conserved between multiple vertebrate species (Fig. 1F). When a mutation of TgN2-4 with the 133 bp sequence deleted was tested in transgenic mice (TgN2-4ΔDNT), the dorsal-neural-tube activity of the enhancer was ablated, whereas the ventral domain activity was unaffected (Fig. 1A,D,E). Thus, the 133 bp sequence containing the putative PTF1-binding site is absolutely required for enhancer activity in the dorsal neural tube.

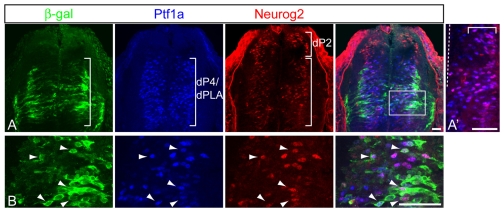

Comparison of endogenous Ptf1a and Neurog2 expression patterns with β-gal from TgN2-4 in the dorsal neural tube further supports the conclusion that Ptf1a regulates Neurog2 expression through the 3′ enhancer. In the dorsal domain of the E10.5/11.5 neural tube where Ptf1a is expressed, Neurog2 was enriched in lateral regions relative to the ventricular zone (Fig. 1C, boxed region). Co-expression of Neurog2 and Ptf1a in the dorsal progenitor domain dP4, the domain that will give rise to dI4 neurons, was demonstrated by immunofluorescence (Fig. 2A,A′). Most Neurog2-expressing cells co-expressed Ptf1a in the dP4 region, and these cells were enriched in the lateral region of the ventricular zone (Fig. 2A′, pink). By contrast, Ptf1a single positive cells were found enriched at more medial regions, a finding consistent with Ptf1a functioning upstream of Neurog2 in this domain. Furthermore, many of the Neurog2/Ptf1a co-expressing cells also expressed β-gal from the TgN2-4 transgene (Fig. 2B, arrowheads). These results suggest that Ptf1a may regulate the expression of Neurog2 through the 3′ enhancer.

Fig. 2.

Ptf1a, Neurog2 and TgN2-4 overlap in the dorsal neural tube. (A) Immunofluorescence for β-gal (green), Ptf1a (blue) and Neurog2 (red) on a transverse section of an E11.5 neural tube from the TgN2-4 transgenic mouse line. Brackets indicate the approximate progenitor domains for dI4 and dILA neurons (dP4/dPLA), or dI2 neurons (dP2). (A′) Higher magnification view of the bracketed dP4/dPLA region showing the extensive overlap (pink) of Neurog2 and Ptf1a. The dashed line indicates the ventricular zone. Note that most Neurog2 cells in this domain co-express Ptf1a and these cells are enriched in the lateral half of this region (top bracket), with Ptf1a single-positive cells enriched more medially. (B) Higher magnification of the region boxed in A. Arrowheads indicate cells co-expressing the three proteins. Scale bars: 50 μm.

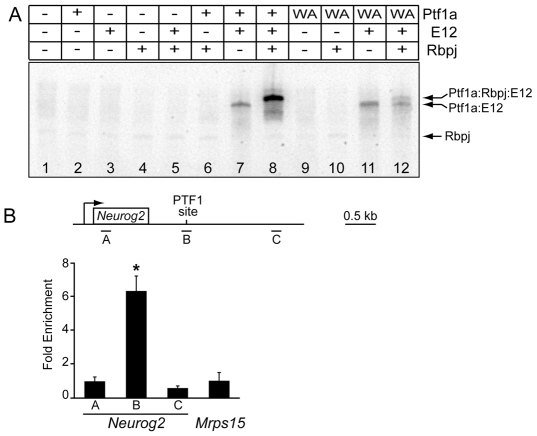

PTF1-J trimer components bind the Neurog2 enhancer in vitro and in vivo

We next determined whether the PTF1-J transcription complex bound the PTF1 site within the Neurog2 enhancer. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) using in vitro translated proteins confirmed PTF1-J trimer binding to the site (Fig. 3A). Singly, Ptf1a, E12 (Tcf3 - Mouse Genome Informatics) and Rbpj did not efficiently bind the site (Fig. 3A, lanes 2-4). Of the heterodimer combinations, only the classic bHLH heterodimer of Ptf1a/E12 formed efficiently (Fig. 3A, lanes 5-7). Adding all three PTF1-J components resulted in an efficient shift of the heterodimer band to the heterotrimer (Ptf1a/E12/Rbpj) (Fig. 3, lane 8). A mutant form of Ptf1a, Ptf1aW298A, that is unable to interact with Rbpj efficiently (Beres et al., 2006; Hori et al., 2008), bound as heterodimer on the PTF1 site but had lost its ability to efficiently form trimer (Fig. 3, lanes 9-12).

Fig. 3.

PTF1-J trimeric complex binds the Neurog2 3′ enhancer in vitro and in vivo. (A) EMSAs with combinations of in vitro translated Ptf1a, Ptf1aW298A (WA), Tcfe2a-E12 (E12) and Rbpj, using the PTF1 site in the Neurog2 3′ enhancer as a probe, show the site can be bound by Ptf1a-E12 heterodimer and Ptf1a-E12-Rbpj heterotrimer (lanes 7,8). Mutant Ptf1aW298A is inefficient at forming the trimer (lane 12) but can bind as a heterodimer with E12 (lane 11). (B) ChIP from E11.5 neural-tube tissue with Ptf1a-specific antibodies followed by qPCR with a series of primers (A-C) across the Neurog2 gene either encompassing the PTF1 site (B) or at a distance of >1.5 kb from this site (A and C). Primers from Mrps15, the gene encoding ribosomal protein 28S, were used as negative control. Enrichment is shown relative to the Mrps15 control. *P<0.0015.

The presence of a binding site for PTF1 in the Neurog2 enhancer suggests that this transcription factor complex functions directly to regulate Neurog2 in the dorsal neural tube. We used chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis to determine whether Ptf1a is bound to the Neurog2 enhancer in vivo. Chromatin from formaldehyde-cross-linked E11.5 neural tubes was immunoprecipitated with antibodies specific to Ptf1a. The immunoprecipitated chromatin was enriched for the Neurog2 enhancer approximately sixfold over that measured for genomic regions ∼1.5 kb away from the PTF1 site or for a negative control gene, Mrps15, encoding the 28S ribosomal protein (Fig. 3B). These results demonstrate that Ptf1a is bound to the Neurog2 enhancer in embryonic neural tubes.

Neurog2 expression in the dI4 progenitor domain requires the PTF1-J transcription complex

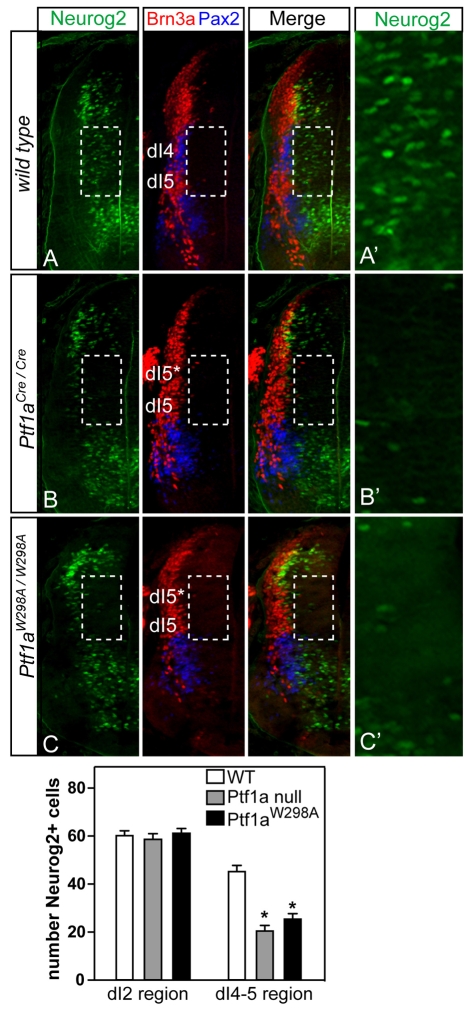

Before pursuing PTF1-J regulation of the Neurog2-lacZ reporter gene, we verified that the endogenous Neurog2 expression requires PTF1-J. Neurog2 is expressed broadly along the dorsoventral axis in the caudal neural tube in neuronal progenitor cells (Gradwohl et al., 1996; Helms et al., 2005; Sommer et al., 1996) (see also Fig. 1C; Fig. 4A). The dorsal half of the neural tube at E10.5 can be subdivided into subdomains (dI1-dI6) based on the expression of neurally expressed homeodomain factors (Helms and Johnson, 2003). With respect to these subdivisions, Neurog2 expression was somewhat uniform in the progenitor region that gives rise to dI2 interneurons, whereas it was expressed in a punctate pattern in the progenitor region that will give rise to dI4 interneurons (Fig. 4A, dashed box). The dI4 domain was defined by the absence of Brn3a (a marker for dI1-3 and dI5) and the presence of Pax2 (a marker for dI4 and dI6-V2) (Fig. 4A). In the Ptf1a null (Ptf1aCre/Cre), Neurog2 was dramatically reduced specifically in the dI4 region (Fig. 4B, compare A′ with B′). For comparison, Neurog2 cells in the dP2/dI2 region were not affected (Fig. 4, see bar chart). Neurog2 was also reduced in this domain in mice with the DNA-binding mutant form of Ptf1a (Ptf1aW298A/W298A) (Fig. 4C, compare A′ with C′). This mutation in Ptf1a disrupts its ability to form the trimeric complex on DNA (Beres et al., 2006; Hori et al., 2008; Masui et al., 2007) (see also Fig. 3A, lane 12). In the Ptf1a mutants, the dI4 neurons marked by Pax2 were mis-specified to Brn3a-expressing dI5-like neurons (Fig. 4B,C, dI5*) (see also Glasgow et al., 2005). Thus, Ptf1a and the PTF1-J transcription complex are required for normal levels of Neurog2 specifically in the dI4 progenitor domain, whereas Neurog2 outside this region is independent of Ptf1a.

Fig. 4.

A Ptf1a-dependent domain of Neurog2 expression is shown in vivo. (A-C) Immunofluorescence for Neurog2 (green) on transverse sections of E10.5 neural tube from wild-type (A), Ptf1aCre/Cre (B), or Ptf1aW298A/W298A (C) embryos (only the left half is shown). The area in the dashed box is the dI4/5 regions delineated using the neuronal-subtype-specific markers Brn3a (dI1-3, dI5; red) and Pax2 (dI4, dI6-V2; blue). In the Ptf1a mutants, dI4 neurons are mis-specified to dI5 (dI5*) (Glasgow et al., 2005). Neurog2 expression is attenuated in the Ptf1a mutants in the dI4 domain (dashed boxes). (A′-C′) Higher magnification of the regions boxed in A-C. (Bottom) The number of Neurog2 cells in the dP2/dI2 or the dP4-5/dI4-5 regions in the wild type and each mutant are shown. *P<0.001.

The Neurog2 3′ enhancer requires the PTF1-J transcription complex for activity in the dorsal neural tube and cerebellum

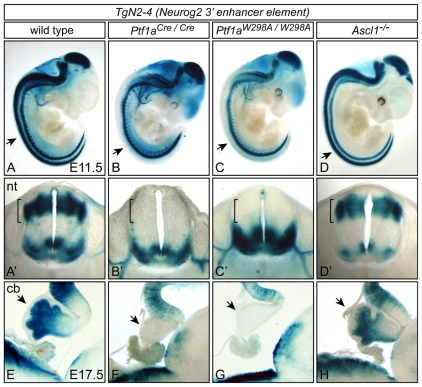

To gain confirmation of a role for PTF1-J in the activity of the Neurog2 3′ enhancer in vivo, we crossed a Neurog2-lacZ transgenic line TgN2-4 into Ptf1a and Ptf1aW298A mutant backgrounds. When lacZ expression was examined in these mutants the absolute requirement of Ptf1a and the PTF1-J complex was confirmed. No β-gal was detected in the dorsal neural tube at E11.5, whereas the ventral neural tube expression was left unaffected (Fig. 5B,C compare with 5A). By contrast, the activity of the enhancer was not disrupted in mutants null for Ascl1 (previously Mash1), a gene encoding a bHLH transcription factor required in the dorsal neural tube for specification of the dI3 and dI5 interneurons (Helms et al., 2005) (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

The Neurog2 3′ enhancer requires Ptf1a but not Ascl1 for activity in the dorsal neural tube and cerebellum. Activity of the TgN2-4 transgene is shown by β-gal staining at E11.5 (A-D′) and E17.5 (E-H) in wild type (A,A′,E), Ptf1aCre/Cre (B,B′,F), Ptf1aW298A/W298A (C,C′,G) or Ascl1-/- (D,D′,H) genetic backgrounds. (A-D) Whole-mount images showing that dorsal-neural-tube expression is lost in the Ptf1a mutants (arrows). (A′-D′) Transverse sections of the neural tube of the embryos shown in A-D; brackets highlight the dorsal-neural-tube expression that is specifically lost in the Ptf1a mutants. (E-H) Sagittal sections of E17.5 cerebellum showing loss of transgene activity in the Ptf1a mutants in this region as well (arrows). In contrast to the Ptf1a mutants, TgN2-4 transgene activity is similar between wild type and the Ascl1 mutant. cb, cerebellum; nt, neural tube.

Ptf1a is present in progenitors to GABAergic neurons in the cerebellum (Glasgow et al., 2005; Hoshino et al., 2005; Pascual et al., 2007), and the PTF1-J trimeric complex is required for the generation of these neurons (Hori et al., 2008). Domains of Ptf1a and Neurog2 expression overlap in the embryonic cerebellum (Zordan et al., 2008), and we found that at E17.5, TgN2-4 expressed lacZ in the cerebellar anlage (Fig. 5E, arrow). When TgN2-4 activity was examined in the Ptf1a null and Ptf1aW298A mutants, lacZ expression was specifically lost in the cerebellum (Fig. 5F,G). By contrast, transgene expression was not altered in the Ascl1 null (Fig. 5H). It should be noted that although some Ptf1a lineage cells get respecified to a granule cell-like lineage in Ptf1a mutants (Pascual et al., 2007), the cerebellar anlage in the mutants was significantly reduced, and this could account for some of the loss of TgN2-4 expression. Nevertheless, together these results demonstrate that the activity of the Neurog2 3′ enhancer in the dorsal neural tube and the cerebellar anlage requires the function of Ptf1a in the PTF1-J transcription complex.

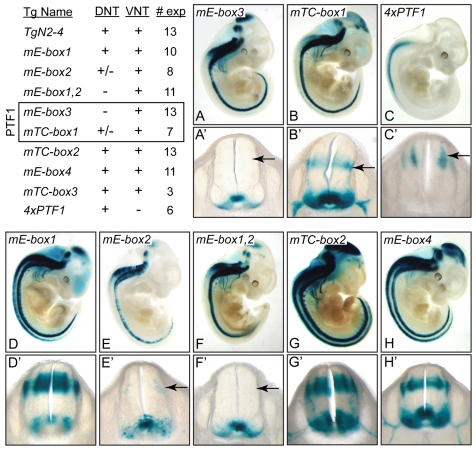

The PTF1 site in the Neurog2 enhancer is required for activity in the dorsal neural tube

To determine whether the PTF1 site is required for the Neurog2 enhancer activity, E-box3 and TC-box1 that make up the PTF1 site were mutated separately in the context of the 1047 bp TgN2-4 enhancer and tested in transgenic embryos at E11.5. When either site was mutated there was a dramatic and specific loss of enhancer activity in the dorsal neural tube relative to activity in the ventral neural tube (Fig. 6A,B). Furthermore, a multimer of the PTF1 site (4×PTF1) was sufficient to direct dorsal-neural-tube-specific expression of the transgene, albeit with less efficiency than the full-length 1047 bp TgN2-4 (Fig. 6C). Together these results demonstrate that the identified PTF1 site is both necessary and sufficient to direct dorsal-neural-tube expression of a reporter gene in transgenic mice.

Fig. 6.

The PTF1 site is necessary and sufficient for dorsal-neural-tube activity of the Neurog2 3′ enhancer. The function of E-box and TC-box sites were tested for enhancer activity in transgenic embryos at E11.5. A summary of the number of transgene-expressing embryos analyzed (# exp), and whether expression was detected in the dorsal domain (DNT) or ventral domain (VNT) for each transgene is shown. The sites mutated are shown in Fig. 1F. (A-H′) Representative whole-mount β-gal-stained E11.5 embryo for each transgene. Note the differences in the dorsal- and ventral-neural-tube expression visible in the whole-mount images and highlighted in transverse sections (A′-H′). (A-C) The function of the PTF1 site for enhancer activity was tested by mutating E-box3 and TC-box1 within the context of the TgN2-4 construct, and by 4×PTF1, which contains four copies in tandem of the PTF1 sequence highlighted in the shaded box in Fig. 1F. (D-H) The function of the other E-boxes and TC-boxes within TgN2-4 were tested. Arrows indicate the embryos in which the activity of the transgene is altered relative to that of the wild-type TgN2-4 transgene (shown in Fig. 5A,A′).

Additional regulatory sequences outside the PTF1 site

Other combinations of E-boxes and TC-boxes in the 133 bp conserved sequence did not serve as PTF1-binding sites (data not shown). However, E-box2, but not the other E-boxes (E-box1 and E-box4), is required for dorsal-neural-tube activity. A mutation of this single site dramatically disrupted enhancer activity in the dorsal domain (Fig. 6E,F). It is not known which E-box binding protein(s) use this site, but it is unlikely to be Ascl1, because no disruption to enhancer activity was seen in the Ascl1 mutant (Fig. 5). Mutation of the other sites, TC-box2 and TC-box3, had no obvious affect on enhancer activity beyond a tendency for embryos to express the transgene at higher levels in the correct domains (Fig. 6G,H). Although this may suggest a role for Rbpj repression through these sites, the data are not conclusive.

Ptf1a drives activity of the Neurog2 enhancer through the PTF1 site

Another test of the responsiveness of the Neurog2 enhancer to Ptf1a function is through co-expression of the TgN2-4 reporter with an expression vector for Ptf1a using in ovo electroporation of chick neural tubes. In this assay, although plasmid DNA entered ventricular zone cells across the whole dorsoventral axis, TgN2-4 reporter gene activity was restricted to characteristic domains, identical to its activity in transgenic mice (compare Fig. 7A with Fig. 1D). When electroporated at HH stage 14-16 and harvested 48 hours later, embryos revealed TgN2-4 directed expression of lacZ to a dorsal and a ventral domain (Fig. 7A) even though cells all along the dorsoventral axis took up the DNA (Fig. 7A′). The two mutants TgN2-4ΔDNT and TgN2-4mEbox3 that delete or mutate the PTF1 site had no activity in the dorsal neural tube, but retained ventral-neural-tube expression, just as in transgenic mice (Fig. 7B,B′,C). To determine if the TgN2-4 regulatory region is responsive to Ptf1a, the reporter constructs and a Ptf1a expression vector were co-electroporated. Then, TgN2-4 was expressed ectopically along the whole dorsoventral axis that received the Ptf1a expression vector (Fig. 7D,D′). By contrast, TgN2-4ΔDNT and TgN2-4mEbox3, which lack the PTF1 site, were not induced along the whole dorsoventral axis as was seen for TgN2-4 (Fig. 7E,E′,F). Thus, Ptf1a can induce the activity of the Neurog2 3′ enhancer, but it requires an intact PTF1 site for this activity.

DISCUSSION

The PTF1-J transcription complex is essential for generating the balance of inhibitory and excitatory neurons in multiple regions of the nervous system, including the dorsal spinal cord and cerebellum. The effects of mutations in mice and humans of the tissue-specific component of this complex, Ptf1a, reveal its importance to postnatal viability (Glasgow et al., 2005; Hoshino et al., 2005; Kawaguchi et al., 2002; Krapp et al., 1998; Sellick et al., 2004). Here we identify the first neural target for the PTF1-J complex as Neurog2, a gene encoding a bHLH transcription factor, itself required for neuronal differentiation and postnatal viability (Fode et al., 1998). The results of a comprehensive set of in vivo and in vitro experiments demonstrate that Ptf1a controls Neurog2 expression in a major portion of the developing dorsal spinal cord and cerebellum. Furthermore, this regulation is direct via the PTF1-J transcription complex through a PTF1 site in an enhancer located 3′ of the Neurog2 gene.

Transcriptional mechanisms integrate neuronal differentiation and specification

Neuronal differentiation and neuronal subtype specification are linked during neural development. When neural progenitor cells in the ventricular zone initiate differentiation, they exit the cell cycle, migrate laterally out of the ventricular zone and induce cell-type-specific patterns of gene expression. The Notch signaling pathway regulates neuronal differentiation by playing a primary role in maintaining progenitor cells (Bolos et al., 2007; Kageyama et al., 2008; Louvi and Artavanis-Tsakonas, 2006). Although Notch signaling may also modulate specification of neuronal subtype (Del Barrio et al., 2007; Mizuguchi et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2006), bHLH and HD transcription factors are the major regulators of this process in the dorsal neural tube (Cheng et al., 2004; Glasgow et al., 2005; Gowan et al., 2001; Gross et al., 2002; Müller et al., 2002). The action of Rbpj within the PTF1-J complex and Neurog2 as a direct target of this complex provide insight into how these two processes can be coupled mechanistically, as Rbpj and Neurog2 are also both players in Notch signaling.

Rbpj is the sole DNA-binding transcriptional effector of the canonical Notch pathway. In the absence of Notch signaling, Rbpj can be bound with a co-repressor complex to target genes. When the Notch pathway is activated, the Notch intracellular domain NICD translocates to the nucleus, where it forms a complex with Rbpj, displaces the co-repressor complex and activates transcription. Known targets of the Rbpj-NICD complex include the bHLH factors of the Hes family that repress transcription of proneural bHLH genes such as Ascl1 and Neurog2. And finally, Ascl1 and Neurog2 directly activate transcription of Notch ligands Dll1 and Dll3 (Castro et al., 2006; Henke et al., 2009), which in turn activate Notch signaling. In this way a balance between neural induction via proneural bHLH factors such as Ascl1 and Neurog2, and neural suppression through Notch signaling via Rbpj, controls the rate that progenitor cells commit to a differentiation program.

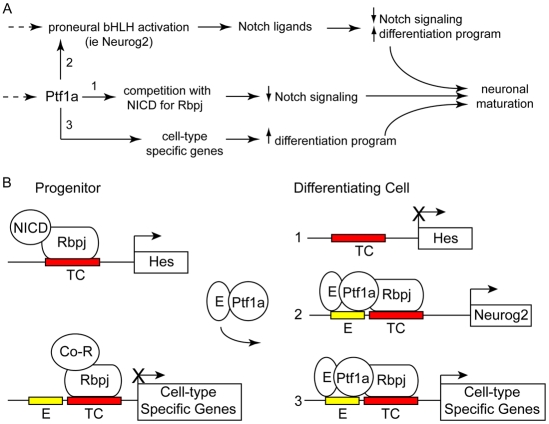

Combining the role of Rbpj in Notch signaling with our studies on PTF1-J, a model begins to emerge that describes the transition of a cell from the progenitor state to specified neuron (Fig. 8A). One defining feature of this model is that Ptf1a and NICD binding to Rbpj is competitive (Beres et al., 2006). In the progenitor zone, Notch signaling is high, and Rbpj is in a complex with NICD. The balance shifts as proneural bHLH expression, such as that of Ascl1, increases. This increase in Ascl1 reflects a decrease in Notch signaling in the cell, freeing up Rbpj to form PTF1-J with Ptf1a to directly induce Neurog2. An increase in Neurog2 levels ensures NICD levels remain low in the cell, leaving Rbpj available for the PTF1-J complex. Persistence of the PTF1-J complex activates cell-type-specific genes that commit cells to the GABAergic lineage.

Fig. 8.

Model illustrating Ptf1a activities. (A) Ptf1a may compete with the Notch intracellular domain (NICD) for Rbpj binding (1) to push the balance away from the progenitor state to the differentiation state. In addition, direct targets of Ptf1a transcription activation through the PTF1 complex include Neurog2 (2), a neuronal differentiation bHLH factor, and as yet unidentified cell-type-specific targets (3). (B) Different combinations of the PTF1 components have the potential to form on gene targets with distinct cis elements (E-box and/or TC-box sites). For example, Hes genes (inhibitors of differentiation) are induced by Notch signaling, not PTF1-J (1). Whereas some target genes such as Neurog2 are activated by PTF1-J through a E-box/TC-box site where the TC-box is not efficiently bound by Rbpj alone and thus is not a target for NICD (2). Still other target genes are predicted to be regulated by Rbpj repressor activity (Co-R) and/or Notch signaling (NICD) before Ptf1a expression through TC-box binding, then activated by PTF1-J once threshold levels of Ptf1a are obtained (3). This network of transcription factor activity ensures that cells transition from progenitors to differentiating neurons. Note numbers 1-3 in A correspond to 1-3 in B.

The specific characteristics of individual PTF1 sites in different gene targets are also likely to influence how each target responds to PTF1-J or Notch signaling (Fig. 8B). The complex nature of the PTF1 site allows for different combinations of Ptf1a-E12 heterodimer, Rbpj repressor, NICD-Rbpj or PTF1-J to compete for binding. For example, PTF1-J but not Rbpj alone efficiently binds the PTF1 site in the Neurog2 enhancer (Fig. 3A), suggesting that this site would not be a target for Rbpj repression or Notch signaling (Fig. 8B). By contrast, one of the autoregulatory PTF1 sites in the Ptf1a enhancer is efficiently bound by Rbpj monomer, leaving open the possibility that Rbpj repression and Notch signaling could regulate Ptf1a levels through this site (Masui et al., 2008). Thus, the ultimate spatial and temporal expression pattern of a given target may be modulated with distinct characteristics by a changing combination of these complexes. Identification of additional PTF1-J targets in the developing nervous system will be needed to validate this molecular model.

Function of Neurog2 downstream of Ptf1a

The bHLH factor Neurog2 (Ngn2, Math4A) functions in neuronal differentiation and is essential for postnatal life (Fode et al., 1998; Kele et al., 2006; Ma et al., 1999). It is expressed in a precise spatial and temporal pattern during the development of the sensory ganglia in the peripheral nervous system and in specific progenitor domains throughout the developing central nervous system (Gradwohl et al., 1996; Sommer et al., 1996). A mouse null for Neurog2 has been used to demonstrate a role for this bHLH factor in the generation of sensory neurons, spinal cord motoneurons, glutamatergic neurons in the cerebral cortex and dopaminergic neurons in the ventral midbrain (Fode et al., 1998; Fode et al., 2000; Kele et al., 2006; Ma et al., 1999; Mizuguchi et al., 2001; Novitch et al., 2001; Scardigli et al., 2001; Schuurmans et al., 2004). It largely functions in inducing neuronal differentiation; however, roles in neuronal specification and migration have also been demonstrated (Hand et al., 2005; Helms et al., 2005; Parras et al., 2002; Schuurmans et al., 2004; Seibt et al., 2003).

Ptf1a is crucial for the formation of GABAergic neurons and the suppression of glutamatergic neurons in the dorsal spinal cord and the cerebellum (Glasgow et al., 2005; Hori et al., 2008; Hoshino et al., 2005; Pascual et al., 2007). The identification of Neurog2 as a direct downstream target of PTF1-J suggests that Neurog2 should also function in these specific domains for generating inhibitory neurons. Indeed, in the dorsal spinal cord of Neurog2 mutant mice, dI4 neurons were lost, a phenotype revealed in Ascl1:Neurog2 double mutant embryos (Helms et al., 2005). Results from further experiments indicated that neither Neurog2 nor Ascl1 is singly required for generation of the dI4 population. As Ascl1 is not lost in the Ptf1a mutant (R.M.H. and J.E.J., unpublished observations), other unknown Ptf1a targets in addition to Neurog2 need to be identified to understand the dramatic loss of the dI4 population in Ptf1a mutants.

A role for Neurog2 in the formation of the GABAergic interneurons in the cerebellum is even less clear, as there have been no reports of a cerebellar phenotype in Neurog2 null mice. The expression pattern of Neurog2 compared to other neural bHLH factors including Ptf1a was recently reported for the embryonic cerebellum (Zordan et al., 2008). Similar to expression in the dorsal neural tube, Neurog2 overlaps domains of Ptf1a and Ascl1. Thus, as for the dorsal spinal cord, a compound mutant may be required to reveal a phenotype for Neurog2 in Ptf1a lineage cells in this brain region.

Regulation of Neurog2 expression in the dorsal neural tube

The distinct temporal and spatial characteristics of Neurog2 expression throughout the developing neural tube is regulated by multiple, separable regulatory sequences located 5′ and 3′ of the Neurog2 coding region (Scardigli et al., 2001; Simmons et al., 2001). To achieve the complexity of Neurog2 expression, these regulatory sequences are likely targets of field- and lineage-specific transcription factors. In the dorsal neural tube, Neurog2 is expressed in cells that give rise to multiple dorsal interneuron populations, including dI2 and dI4. However, the only known enhancer with activity in the dorsal neural tube (TgN2-4) is active only in progenitors that give rise to the dI4 population. This is evident from the complete loss of β-gal signal from the TgN2-4 reporter in the Ptf1a mutants in which dI4 neurons are lost but the other dorsal interneurons are still present (Glasgow et al., 2005). Not all Neurog2 cells in the dP4/dI4 domain have detectable levels of β-gal from the TgN2-4 transgene (Fig. 2), possibly indicating that regulatory elements even for this restricted domain are missing from this enhancer. These regulatory elements, and the regulatory sequences directing Neurog2 expression to the other dorsal interneuron lineages, have yet to be located and must be in gene regions not yet tested.

Several upstream regulatory factors controlling dorsal-neural-tube-expressed Neurog2 have been reported. The paired homeodomain factors Pax6 and Pax3 modulate Neurog2 levels in the dorsal neural tube, as determined by decreased Neurog2 expression in Pax6 and Pax3 mutant embryos, distinct Pax6 and Pax3 sites in the 3′ enhancer, and Pax3 ChIP revealing direct binding to the enhancer (Nakazaki et al., 2008; Scardigli et al., 2003; Scardigli et al., 2001). However, regulation of dorsal Neurog2 by the Pax factors does not map to the 133 bp DNT element examined here (Fig. 1F). Wnt signaling via β-catenin (Ctnnb1 - Mouse Genome Informatics) activation also appears to modulate Neurog2 expression, although the responsive element in the Neurog2 gene was not identified (Ille et al., 2007). One possibility that warrants further study is whether the canonical Wnt signaling pathway modulates Neurog2 levels via regulating Ptf1a expression and thus the presence of the PTF1-J complex.

As described above, PTF1-J is not the only regulator of Neurog2 expression in the dorsal neural tube. In addition to a role for Pax6, Pax3 and Wnt, the loss of dorsal enhancer activity with the E-box2 mutation (Fig. 6E,E′) suggests additional transcriptional components function through this enhancer. Interestingly, a sequence element including E-box2 is similar to a consensus site for Pou3f2 (Brn2) binding, and the mutation used here that disrupted enhancer activity is predicted to disrupt binding of both E-box binding proteins and Pou proteins. Thus, a Pou family transcription factor may also function through the 133 bp conserved sequence within the Neurog2 3′ enhancer. A model delineating the molecular mechanisms regulating Neurog2 expression is being revealed that incorporates multiple transcription factors and signaling pathways that act through distinct regulatory sequences surrounding the Neurog2 gene.

PTF1-J target sites fit the consensus for PTF1-L sites in pancreatic targets

Ptf1a is essential for pancreas development and function. Two distinct forms of PTF1 are found in pancreas: PTF1-J, which functions during development, and PTF1-L, which functions in the adult to regulate transcription of genes encoding most, if not all, of the pancreatic digestive enzymes (Beres et al., 2006; Masui et al., 2007). PTF1-L contains Rbpj-like (Rbpjl), whereas PTF1-J contains Rbpj. The PTF1 target site consensus is CANNTG(N4/5)WTTCCCA (Beres et al., 2006). In the developing pancreas before the appearance of Rbpjl, the PTF1-J form of PTF1 is active on targets that include Rbpjl and Ptf1a itself (Masui et al., 2007; Masui et al., 2008). Examination of the PTF1-J target sites, including the neural PTF1-J target identified in Neurog2, shows that there is no obvious distinction in consensus site for PTF1-J versus PTF1-L. Thus, it is unclear why pancreatic PTF1-target genes are not expressed in the developing neural tube, and Neurog2 is not expressed in the embryonic or adult pancreas. Organ-specific co-factors or binding-affinity characteristics not detected in this study may be involved. Alternatively, organ-specific silencers may be present that suppress transcription of neuronal genes in the pancreas and vice versa. A full understanding of how Ptf1a controls different sets of genes in the pancreas in contrast to how it controls genes specifying the balance of inhibitory and excitatory neurons in the dorsal neural tube and cerebellum must await a more comprehensive identification of direct transcriptional targets of the PTF1-J complex in each tissue.

We thank Dr Robert Hammer and the outstanding service of the UT Southwestern Transgenic Core Facility for generating the transgenic mice for this study. We acknowledge Drs G. Swift, K. Zimmerman, H. Lai and E. J. Kim for critical comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH Public Health Service grants R01-HD37932 (J.E.J.), R01-DK61220 (R.J.M.) and T32-MH076690 (D.M.M.). Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

References

- Beres, T., Masui, T., Swift, G. H., Shi, L., Henke, R. M. and MacDonald, R. J. (2006). PTF1 is an organ-specific and Notch-independent bHLH complex containing the mammalian Suppressor of Hairless (RBP-J) or its paralogue RBP-L. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 117-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolos, V., Grego-Bessa, J. and de la Pompa, J. L. (2007). Notch signaling in development and cancer. Endocr. Rev. 28, 339-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinster, R. L., Chen, H. Y., Trumbauer, M. E., Yagle, M. K. and Palmiter, R. D. (1985). Factors affecting the efficiency of introducing foreign DNA into mice by microinjecting eggs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82, 4438-4442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro, D. S., Skowronska-Krawczyk, D., Armant, O., Donaldson, I. J., Parras, C., Hunt, C., Critchley, J. A., Nguyen, L., Gossler, A., Gottgens, B. et al. (2006). Proneural bHLH and Brn proteins coregulate a neurogenic program through cooperative binding to a conserved DNA motif. Dev. Cell 11, 831-844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, L., Arata, A., Mizuguchi, R., Qian, Y., Karunaratne, A., Gray, P. A., Arata, S., Shirasawa, S., Bouchard, M., Luo, P. et al. (2004). Tlx3 and Tlx1 are post-mitotic selector genes determining glutamatergic over GABAergic cell fates. Nat. Neurosci. 7, 510-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, L., Abdel-Samad, O., Xu, Y., Mizuguchi, R., Luo, P., Shirasawa, S., Goulding, M. and Ma, Q. (2005). Lbx1 and Tlx3 are opposing switches in determining GABAergic versus glutamatergic transmitter phenotypes. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 1510-1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Barrio, M. G., Taveira-Marques, R., Muroyama, Y., Yuk, D. I., Li, S., Wines-Samuelson, M., Shen, J., Smith, H. K., Xiang, M., Rowitch, D. et al. (2007). A regulatory network involving Foxn4, Mash1 and delta-like 4/Notch1 generates V2a and V2b spinal interneurons from a common progenitor pool. Development 134, 3427-3436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dullin, J. P., Locker, M., Robach, M., Henningfeld, K. A., Parain, K., Afelik, S., Pieler, T. and Perron, M. (2007). Ptf1a triggers GABAergic neuronal cell fates in the retina. BMC Dev. Biol. 7, 110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fode, C., Gradwohl, G., Morin, X., Dierich, A., LeMeur, M., Goridis, C. and Guillemot, F. (1998). The bHLH protein NEUROGENIN 2 is a determination factor for epibranchial placode-derived sensory neurons. Neuron 20, 483-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fode, C., Ma, Q., Casarosa, S., Ang, S. L., Anderson, D. J. and Guillemot, F. (2000). A role for neural determination genes in specifying the dorsoventral identity of telencephalic neurons. Genes Dev. 14, 67-80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujitani, Y., Fujitani, S., Luo, H., Qiu, F., Burlison, J., Long, Q., Kawaguchi, Y., Edlund, H., MacDonald, R. J., Furukawa, T. et al. (2006). Ptf1a determines horizontal and amacrine cell fates during mouse retinal development. Development 133, 4439-4450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow, S. M., Henke, R. M., Macdonald, R. J., Wright, C. V. and Johnson, J. E. (2005). Ptf1a determines GABAergic over glutamatergic neuronal cell fate in the spinal cord dorsal horn. Development 132, 5461-5469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowan, K., Helms, A. W., Hunsaker, T. L., Collisson, T., Ebert, P. J., Odom, R. and Johnson, J. E. (2001). Crossinhibitory activities of Ngn1 and Math1 allow specification of distinct dorsal interneurons. Neuron 31, 219-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gradwohl, G., Fode, C. and Guillemot, F. (1996). Restricted expression of a novel murine atonal-related bHLH protein in undifferentiated neural precursors. Dev. Biol. 180, 227-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross, M. K., Dottori, M. and Goulding, M. (2002). Lbx1 specifies somatosensory association interneurons in the dorsal spinal cord. Neuron 34, 535-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillemot, F., Lo, L. C., Johnson, J. E., Auerbach, A., Anderson, D. J. and Joyner, A. L. (1993). Mammalian achaete-scute homolog 1 is required for the early development of olfactory and autonomic neurons. Cell 75, 463-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hand, R., Bortone, D., Mattar, P., Nguyen, L., Heng, J. I., Guerrier, S., Boutt, E., Peters, E., Barnes, A. P., Parras, C. et al. (2005). Phosphorylation of Neurogenin2 specifies the migration properties and the dendritic morphology of pyramidal neurons in the neocortex. Neuron 48, 45-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helms, A. W. and Johnson, J. E. (2003). Specification of dorsal spinal cord interneurons. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 13, 42-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helms, A. W., Battiste, J., Henke, R. M., Nakada, Y., Simplicio, N., Guillemot, F. and Johnson, J. E. (2005). Sequential roles for Mash1 and Ngn2 in the generation of dorsal spinal cord interneurons. Development 132, 2709-2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henke, R. M., Meredith, D. M., Borromeo, M. D., Savage, T. K. and Johnson, J. E. (2009). Ascl1 and Neurog2 form novel complexes and regulate Delta-like3 (Dll3) expression in the neural tube. Dev. Biol. 328, 529-540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori, K., Cholewa-Waclaw, J., Nakada, Y., Glasgow, S. M., Masui, T., Henke, R. M., Wildner, H., Martarelli, B., Beres, T. M., Epstein, J. A. et al. (2008). A nonclassical bHLH Rbpj transcription factor complex is required for specification of GABAergic neurons independent of Notch signaling. Genes Dev. 22, 166-178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshino, M., MNakamura, S., Mori, K., Kawauchi, T., Terao, M., Nishimura, Y., Fukuda, A., Fuse, T., Matsuo, N., Sone, M. et al. (2005). Ptf1a, a bHLH transcriptional gene, defines GABAergic neuronal fates in cerebellum. Neuron 47, 201-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ille, F., Atanasoski, S., Falk, S., Ittner, L. M., Marki, D., Buchmann-Moller, S., Wurdak, H., Suter, U., Taketo, M. M. and Sommer, L. (2007). Wnt/BMP signal integration regulates the balance between proliferation and differentiation of neuroepithelial cells in the dorsal spinal cord. Dev. Biol. 304, 394-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kageyama, R., Ohtsuka, T., Shimojo, H. and Imayoshi, I. (2008). Dynamic Notch signaling in neural progenitor cells and a revised view of lateral inhibition. Nat. Neurosci. 11, 1247-1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi, Y., Cooper, B., Gannon, M., Ray, M., MacDonald, R. J. and Wright, C. V. E. (2002). The role of the transcriptional regulator Ptf1a in converting intestinal to pancreatic progenitors. Nat. Genet. 32, 128-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kele, J., Simplicio, N., Ferri, A. L., Mira, H., Guillemot, F., Arenas, E. and Ang, S. L. (2006). Neurogenin 2 is required for the development of ventral midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Development 133, 495-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krapp, A., Knofler, M., Ledermann, B., Burki, K., Berney, C., Zoerkler, N., Hagenbuchle, O. and Wellauer, P. K. (1998). The bHLH protein PTF1-p48 is essential for the formation of the exocrine and the correct spatial organization of the endocrine pancreas. Genes Dev. 12, 3752-3763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriks, S., Lanuza, G. M., Mizuguchi, R., Nakafuku, M. and Goulding, M. (2005). Gsh2 is required for the repression of Ngn1 and specification of dorsal interneuron fate in the spinal cord. Development 132, 2991-3002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louvi, A. and Artavanis-Tsakonas, S. (2006). Notch signalling in vertebrate neural development. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 7, 93-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Q., Fode, C., Guillemot, F. and Anderson, D. J. (1999). Neurogenin1 and neurogenin2 control two distinct waves of neurogenesis in developing dorsal root ganglia. Genes Dev. 13, 1717-1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masui, T., Long, Q., Beres, T. M., Magnuson, M. A. and MacDonald, R. J. (2007). Early pancreatic development requires the vertebrate Suppressor of Hairless (RBPJ) in the PTF1 bHLH complex. Genes Dev. 21, 2629-2643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masui, T., Swift, G. H., Hale, M. A., Meredith, D. M., Johnson, J. E. and Macdonald, R. J. (2008). Transcriptional autoregulation controls pancreatic Ptf1a expression during development and adulthood. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 5458-5468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuguchi, R., Sugimori, M., Takebayashi, H., Kosako, H., Nagao, M., Yoshida, S., Nabeshima, Y., Shimamura, K. and Nakafuku, M. (2001). Combinatorial roles of olig2 and neurogenin2 in the coordinated induction of pan-neuronal and subtype-specific properties of motoneurons. Neuron 31, 757-771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuguchi, R., Kriks, S., Cordes, R., Gossler, A., Ma, Q. and Goulding, M. (2006). Ascl1 and Gsh1/2 control inhibitory and excitatory cell fate in spinal sensory interneurons. Nat. Neurosci. 9, 770-778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller, T., Brohmann, H., Pierani, A., Heppenstall, P. A., Lewin, G. R., Jessell, T. M. and Birchmeier, C. (2002). The homeodomain factor Lbx1 distinguishes two major programs of neuronal differentiation in the dorsal spinal cord. Neuron 34, 551-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazaki, H., Reddy, A. C., Mania-Farnell, B. L., Shen, Y. W., Ichi, S., McCabe, C., George, D., McLone, D. G., Tomita, T. and Mayanil, C. S. (2008). Key basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor genes Hes1 and Ngn2 are regulated by Pax3 during mouse embryonic development. Dev. Biol. 316, 510-523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakhai, H., Sel, S., Favor, J., Mendoza-Torres, L., Paulsen, F., Duncker, G. I. and Schmid, R. M. (2007). Ptf1a is essential for the differentiation of GABAergic and glycinergic amacrine cells and horizontal cells in the mouse retina. Development 134, 1151-1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novitch, B. G., Chen, A. I. and Jessell, T. M. (2001). Coordinate regulation of motor neuron subtype identity and pan-neuronal properties by the bHLH repressor Olig2. Neuron 31, 773-789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obata, J., Yano, M., Mimura, H., Goto, T., Nakayama, R., Mibu, Y., Oka, C. and Kawaichi, M. (2001). p48 subunit of mouse PTF1 binds to RBP-Jk/CBF-1, the intracellular mediator of Notch signalling, and is expressed in the neural tube of early stage embryos. Genes Cells 6, 345-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parras, C. M., Schuurmans, C., Scardigli, R., Kim, J., Anderson, D. J. and Guillemot, F. (2002). Divergent functions of the proneural genes Mash1 and Ngn2 in the specification of neuronal subtype identity. Genes Dev. 16, 324-338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual, M., Abasolo, I., Mingorance-Le Meur, A., Martinez, A., Del Rio, J. A., Wright, C. V., Real, F. X. and Soriano, E. (2007). Cerebellar GABAergic progenitors adopt an external granule cell-like phenotype in the absence of Ptf1a transcription factor expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 5193-5198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scardigli, R., Schuurmans, C., Gradwohl, G. and Guillemot, F. (2001). Crossregulation between neurogenin2 and pathways specifying neuronal identity in the spinal cord. Neuron 31, 203-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scardigli, R., Bäumer, N., Gruss, P., Guillemot, F. and Le Roux, I. (2003). Direct and concentration-dependent regulation of the proneural gene Neurogenin2 by Pax6. Development 130, 3269-3281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuurmans, C., Armant, O., Nieto, M., Stenman, J. M., Britz, O., Klenin, N., Brown, C., Langevin, L. M., Seibt, J., Tang, H. et al. (2004). Sequential phases of cortical specification involve Neurogenin-dependent and -independent pathways. EMBO J. 23, 2892-2902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seibt, J., Schuurmans, C., Gradwhol, G., Dehay, C., Vanderhaeghen, P., Guillemot, F. and Polleux, F. (2003). Neurogenin2 specifies the connectivity of thalamic neurons by controlling axon responsiveness to intermediate target cues. Neuron 39, 439-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellick, G. S., Barker, K. T., Stolte-Dijkstra, I., Fleischmann, C., Coleman, R. J., Garrett, C., Gloyn, A. L., Edghill, E. L., Hattersley, A. T., Wellauer, P. K. et al. (2004). Mutations in PTF1A cause pancreatic and cerebellar agenesis. Nat. Genet. 36, 1301-1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, A. D., Horton, S., Abney, A. L. and Johnson, J. E. (2001). Neurogenin2 expression in ventral and dorsal spinal neural tube progenitor cells is regulated by distinct enhancers. Dev. Biol. 229, 327-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, L., Ma, Q. and Anderson, D. J. (1996). Neurogenins, a novel family of atonal-related bHLH transcription factors, are putative mammalian neuronal determination genes that reveal progenitor cell heterogenity in the developing CNS and PNS. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 8, 221-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmer, J., Johnson, J. and Niswander, L. (2001). The use of in ovo electroporation for the rapid analysis of neural-specific murine enhancers. Genesis 29, 123-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildner, H., Muller, T., Cho, S. H., Brohl, D., Cepko, C. L., Guillemot, F. and Birchmeier, C. (2006). dILA neurons in the dorsal spinal cord are the product of terminal and non-terminal asymmetric progenitor cell divisions, and require Mash1 for their development. Development 133, 2105-2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, M., Terao, M., Terashima, T., Fujiyama, T., Kawaguchi, Y., Nabeshima, Y. and Hoshino, M. (2007). Origin of climbing fiber neurons and their developmental dependence on Ptf1a. J. Neurosci. 27, 10924-10934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X., Tomita, T., Wines-Samuelson, M., Beglopoulos, V., Tansey, M. G., Kopan, R. and Shen, J. (2006). Notch1 signaling influences v2 interneuron and motor neuron development in the spinal cord. Dev. Neurosci. 28, 102-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee, S. and Rigby, P. W. J. (1993). The regulation of myogenin gene expression during the embryonic development of the mouse. Genes Dev. 7, 1277-1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zordan, P., Croci, L., Hawkes, R. and Consalez, G. G. (2008). Comparative analysis of proneural gene expression in the embryonic cerebellum. Dev. Dyn. 237, 1726-1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]