Abstract

Context

Since drug-involved women are among the fastest growing groups with AIDS, sexual risk reduction intervention for them is a public health imperative.

Objective

Test effectiveness of HIV/STD safer sex skills building (SSB) groups for women in community drug treatment.

Design

Randomized trial of SSB versus standard HIV/STD Education (HE); assessments at baseline, 3- and 6- months

Participants

Women recruited from 12 methadone or psychosocial treatment programs in NIDA’s Clinical Trials Network. 515 women with ≥ one unprotected vaginal or anal sex occasion (USO) with a male partner in the past 6 months were randomized.

Interventions

In SSB, five 90-minute groups used problem-solving and skills rehearsal to increase HIV/STD risk awareness, condom use and partner negotiation skills. In HE, one 60-minute group covered HIV/STD disease, testing, treatment, and prevention information.

Main Outcome

Number of USOs at follow up.

Results

A significant difference in mean USOs was obtained between SSB and HE over time (F=67.2, p<.0001). At 3 months, significant decrements were observed in both conditions. At 6 months SSB maintained the decrease, HE returned to baseline (p<.0377). Women in SSB had 29% fewer USOs than those in HE.

Conclusions

Skills building interventions can produce ongoing sexual risk reduction in women in community drug treatment.

Keywords: HIV Prevention Intervention, Drug Treatment, Skills Building, Randomized Control, Trial

INTRODUCTION

Women in high drug use communities are among the fastest growing groups of people with AIDS in the U.S.1, 2 While the proportion of female AIDS cases due to injection drug use has declined in recent years, the proportion due to heterosexual transmission has increased. Unsafe sex also carries the risk of infection with other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). Female drug users are at especially high risk for heterosexual transmission of HIV, even during drug treatment, as they are often in primary sexual relationships with male drug users, and their own substance use often continues.3, 4 Under the influence of drugs, especially cocaine or crack, they are vulnerable to hypersexuality, disinhibition, and drug hunger that can compel trading sex for drugs.5, 6 Thus, development of interventions to reduce HIV risk behavior among drug abusing women is a critical public health imperative. This is especially true in the light of the recent halting of HIV vaccine trials due to lack of effectiveness. Effective interventions are needed that can be implemented across a range of drug treatment and primary care settings.

Drug treatment offers an ideal opportunity to engage women in interventions to improve self-care, including HIV/STD safer sexual behavior. However, while drug treatment has had an important role in reducing HIV risk by reducing drug use and injection,7, 8 sexual risk behavior has been slower to change and has received less attention as a component of drug treatment. A 2001 survey conducted among community-based drug treatment programs participating in the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Clinical Trials Network (CTN) showed that most programs offered HIV education in a single 30 to 90 minute, group informational session.9 The evidence to date suggests that such brief, didactic sessions are inadequate to influence sexual risk behavior. Rather, meta-analyses and reviews of controlled trials of HIV risk reduction interventions among drug users,4, 10, 11 and women at high risk for heterosexual transmission12, 13 suggest that efficacious interventions have certain core features, including gender specific groups, intensity of at least 4 sessions, a focus on skills building. This is especially true for sexual risk reduction interventions because effect sizes have been modest.10, 13 Among women, suggestions for improvement including more emphasis on helping women exert control over sexual encounters, challenging cultural norms wherein men are in control, and increasing the comprehensiveness of HIV-prevention interventions in part by combining them with drug treatment.13

The NIDA CTN therefore conducted a randomized trial to test the effectiveness of an evidence-based HIV/STD safer sex skills building (SSB) intervention for female drug users.14, 15 The SSB intervention is a female-specific, 5-session group intervention emphasizing risk reduction skills. In addition, it addresses female-male control issues and negotiation of condom use, and can be integrated into drug treatment programs. In a previous, single-site randomized clinical trial among women in methadone maintenance treatment, SSB compared to a single session HIV/STD education control condition produced significant increases in frequency of condom use and self-efficacy to use condoms, both immediately after intervention and at 15-month follow-up.14, 15 A larger trial was indicated to test the effectiveness of this intervention when conducted by front-line counselors across a diverse sample of community-based treatment settings.

This study was conducted in 12 community-based outpatient substance abuse treatment programs affiliated with the NIDA CTN, seven methadone maintenance programs and five outpatient programs. The primary outcome was number of unprotected (vaginal and anal) sex occasions during the prior 3 months and was assessed at baseline and at 3- and 6-month post-intervention. It was hypothesized that SSB compared to control would result in long-lasting reductions in unsafe sexual behavior. The control condition was a standard HIV/STD education session chosen to reflect treatment as usual (TAU), as identified in the investigators’ aforementioned survey of HIV education delivered in CTN community treatment programs.9 In using this TAU comparison, while observing key methodological requirements for randomized efficacy trials, this study embodied Carroll and Rounsaville’s “hybrid” efficacy/effectiveness model, targeting critical questions about the treatment’s utility in standard clinical practice.16

In addition, monogamy is widely acknowledged to pose one of the greatest obstacles to practicing safer sex among women,17–19 since women in relationships perceived to be monogamous are less likely to use condoms, despite the possibility that the male partner may be at risk of HIV or STDs, or may have other partners. Perceived monogamy was therefore included as a covariate in the analysis.

METHODS

The 12 participating treatment programs were distributed geographically across 9 states, and included both methadone maintenance (MM) programs, serving opiate dependent women, and outpatient treatment (OPT) programs serving mainly cocaine dependent women, a setting less studied with regard to HIV risk reduction. Sites were half urban and half rural, and were variously located in the West (2 sites), Midwest (2 sites), Northeast (4 sites), and Southeast (4 sites).

Study Population

Women in treatment were recruited between May 2004 and October 2005 through fliers and announcements and word of mouth. Women were paid $5 for their time to complete a brief screening interview, with broad eligibility criteria and few exclusions, in an effort to minimize burden and maximize representativeness of the sample. Women were eligible for the trial if they were: (1) ≥ 18 years old; (2) able to understand and speak English; (3) participating in drug treatment (i.e. for women in MM, for at least 30 days, to assure methadone dose stability); and (4) had unprotected vaginal or anal intercourse with a male partner within the past 6 months, ascertained with the Risk Behavior Survey (RBS).20, 21 Women were excluded if they were: (1) exhibiting significant cognitive impairment, denoted by < 25 on the Mini-Mental Status Exam (MMSE);22, 23 or (2) currently pregnant, or immediately planning pregnancy. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Columbia University/New York State Psychiatric Institute and at all 12 clinical sites, as well as an independent Data Safety and Monitoring Board appointed by NIDA. All participants gave written informed consent at screening and, if eligible, again at study entry.

Design and Procedures

After determination of eligibility and consent, participants were asked to complete a two to three hour baseline interview, which consisted of the CTN Common Assessment Battery and the primary outcome assessment, the Sexual Experiences and Risk Behavior Assessment Schedule (SERBAS).24 The CTN Common Assessment Battery, built around a simplified version of the Addiction Severity Index,25 collects information on demographics, drug and alcohol use, and related problem areas. Follow up interviews, taking about one hour, were conducted 3- and 6-months after randomization, consisting of a shorter version of the Common Assessment Battery and the SERBAS. Participants were paid $25 (or a regionally equivalent amount) for their time and effort for each baseline and follow-up interview.

The SERBAS24 ascertains the number of unprotected vaginal and anal intercourse occasions (i.e. without condom use) by partner type (main versus non-main partners), number of partners, and gender of partners for the 3-months prior to each assessment, using timeline-follow back type cues for recall. The SERBAS is a widely used sexual risk behavior assessment with good evidence of reliability and validity among both injection drug users,26 and women at high risk for HIV,27 among other groups. For this study, the SERBAS was administered using an audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) format (i.e. similar to that used in the multi-site NIMH Healthy Living Project for diverse HIV seropositive people28). Several studies have suggested that research participants report higher, and likely more accurate, rates of sexual risk behaviors using ACASI format, compared to face to face interviews with a researcher.29, 30

Randomization

Cohorts of 3 to 8 participants, receiving baseline assessment within successive 3-week periods, were randomly assigned in blocks to Safer Sex Skills Building (SSB) or HIV/STD Health Education (HE) groups. Under the direction of Veteran Affairs Perry Point Cooperative Studies Coordinating Center, Project Coordinators at each site received the random assignment via an automated telephone system. Procedures used to protect the blinding of the research assistants conducting the assessments included: (1) instructing intervention counselors, site Project Coordinators, and study participants not to disclose randomization to research staff; and (2) using highly structured assessments and computer assisted self-interviews to minimize spontaneous discussion between research assistants and participants. These procedures were largely effective in protecting blinding: at 3-month follow-up, research assistants reported knowing the intervention assignment of 17.5% of participants; at 6-month follow-up, this rate was 13.2%.

Interventions

Safer Sex Skills Building (SSB), the experimental condition, and HIV/STD Education (HE), the control condition, shared common operational features. Both were manual-driven interventions, conducted in groups of 3 to 8 women, co-led by a pair of female counselors working at the participating sites. Counselors were trained in, and conducted, both interventions. Although use of the same counselors to conduct both interventions poses the risk of cross-intervention contamination, it avoids confounding of counselor characteristics between the two interventions that occurs when separate counselors conduct each intervention.31 Systematic training and ongoing supervision of counselors around manual adherence (see below) were employed to protect against cross-contamination. Women in both interventions received $10 for each session attended. Otherwise, the 2 interventions differed in number of sessions (HE: 1 session; SSB: 5 sessions) and content (HE: information only; SSB: information plus skills building). Table 1 presents an outline of each intervention.

Table 1.

Outlines of the Safer Sex Skills Building (SSB) and HIV/STD Education (HE) Interventions

| SSB Intervention | |

|---|---|

| Session 1 | HIV/STD Education, including transmission, testing and counseling, prevention, and treatment |

| Session 2 | HIV Personal Risk Assessment and Awareness Building, including triggers for sexual risk, sources of support and ways of seeking help |

| Session 3 | Condom Skill-Building and Safer Sex Problem-Solving Skill Building, including male and female condom demonstration and rehearsal, and problem-solving |

| Session 4 | Safer Sex Negotiation Skill Building and Partner Abuse Risk Assessment and Safety Planning Skill Building |

| Session 5 | Wrap-up, Review and Graduation, including practice vignettes focusing on “slip” behavior and resource discussion |

| HE Intervention | |

| Session 1 | HIV/STD Education, including transmission, testing and counseling, prevention, and treatment |

Safer Sex Skills Building (SSB)

SSB14 consisted of five 90-minute group sessions, designed to build cognitive, affective and behavioral skills for safer sexual decision making and behavior through active problem-solving, behavioral modeling, role play rehearsal, interval practice, troubleshooting, and peer feedback and support. Through collaboration between the study development team, drug treatment providers, and the developer (Dr El-Bassel), the SSB manual was updated to place more emphasis on women’s negotiation skills around safer sex and safeguards against the risk of partner abuse as the potential result of assertiveness around safer sex.

HIV/STD Education (HE)

HE, conducted in a single 60-minute group session, consisted of discussion of HIV/STD definitions, transmission, testing and counseling, treatment and prevention. The counselors used a didactic presentation style and question-and-answer format along with flip chart visual materials and handouts.

Intervention Training and Quality Control

Training in both SSB and HE took place over 2 ½ days at a centralized location. Both counselors who would conduct the interventions and supervisors from community treatment programs were trained simultaneously. The local supervisors were primarily responsible for ongoing supervision of the interventions during the trial with guidance and support from the Lead Study Team. This train-the-trainer model is advantageous for effectiveness trials since it simulates how the intervention would perform if disseminated into community-based treatment where on-site supervision would be the norm. During the training, counselors and supervisors practiced intervention skills. Additionally, supervisors practiced supervision skills and rated counselors on adherence to the manuals using the SSB and HE adherence rating scales.14 For each intervention, counselors and supervisors were certified if they demonstrated at least adequate proficiency on mock exercises. Thereafter, on an alternate-week basis, all counselors and supervisors participated in conference calls with Lead Study Team trainers to share intervention experiences and problem-solve difficult situations. All group sessions were audiotaped. Local supervisors rated 150 audiotaped intervention sessions and conducted weekly supervision meetings with counselors at their sites. Lead Study Team trainers co-rated 42% of the audiotapes. Among these audiotapes, rates of adherence were 80.2% (SSB, n=107) and 87.2% (HE, n=37). Corrective action was taken, in the form of explicit instruction and increased session review, when either counselor ratings or supervisor-Lead Study Team reliability on ratings fell below adequate proficiency levels.

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome measure was the number of unprotected (vaginal or anal) sex occasions over the 3 months prior to assessment, as derived from the SERBAS. Using the intent-to-treat (ITT) sample of all randomized women for whom at least one follow-up data point was available, Mixed Effects Modeling (MEM)32, 33 was used to test the effects of the two intervention conditions (SSB vs HE), on the primary outcome, observed at 3- and 6-months after randomization. MEM was considered an optimal approach for analyzing the effect of treatment condition on repeated outcome measures, while estimating random effects due to site, intervention cohort, and individual subject,34 and it accommodates missing data, provided they are missing at random.35 Since the primary outcome is a count and follows the Poisson distribution, a Poisson link function was used. Baseline log(number of unprotected sexual occasions) was entered as a covariate. In the primary outcome analysis, three factors – site, intervention cohort, and subject – were treated as random effects. Four factors, intervention condition, assessment time, baseline unprotected sexual occasions, and contemporaneous monogamy status (a time-dependent covariate measured at the 3- and 6 month follow-up points), were treated as fixed effects. Monogamy status was included, a priori, as a covariate because of the widely observed association between primary relationships and reduced levels of condom use.17–19 Monogamy status is determined from the SERBAS, based on the woman’s self-report of whether she considers any male partner to be her “main” partner, and whether or not she reports any other (male or female) partners. Women with a “main” male partner only were considered monogamous; women with other male and/or female partners were considered non-monogamous. In a secondary outcome analysis, completion status (defined as whether or not participants attended the single HE session, or at least 3 sessions of the SSB condition) was added as additional fixed effect to examine whether participation intensity in the SSB intervention would be specifically associated with improvement in sexual risk behavior. SAS PROC GLIMMIX36 was used to conduct these analyses.

RESULTS

Participant Flow

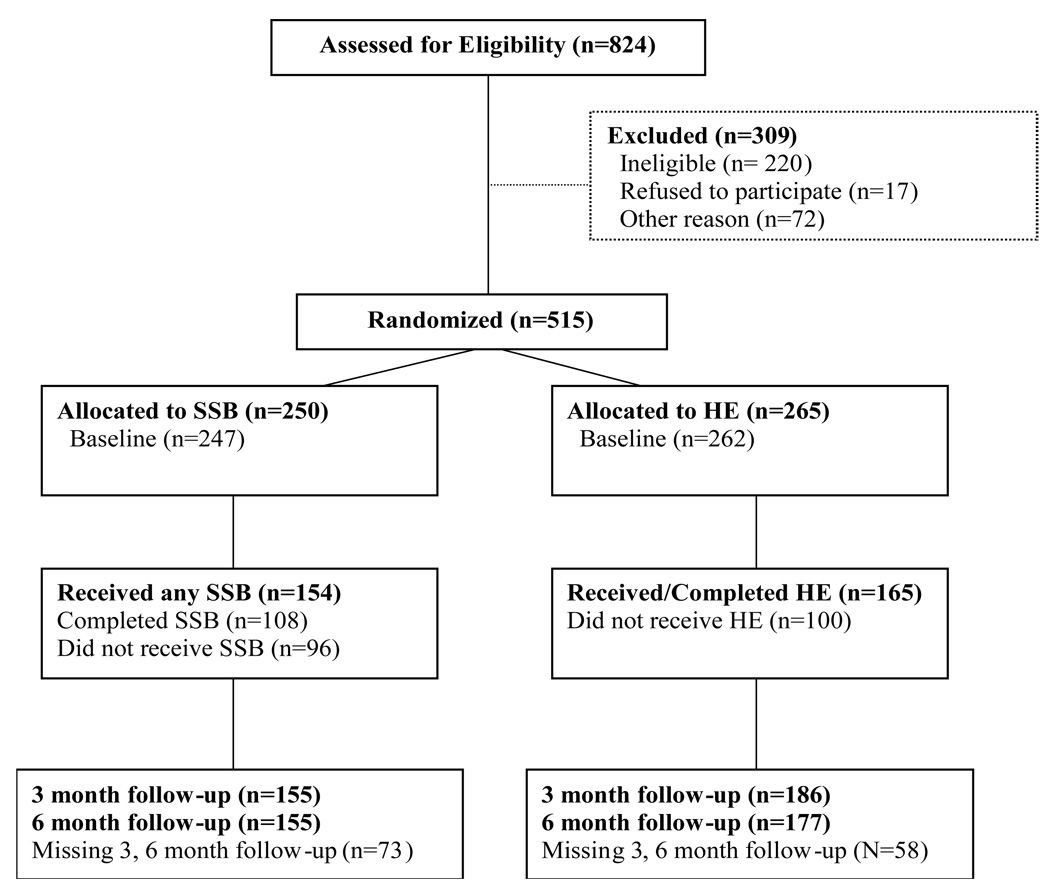

Figure 1 presents subject flow through the course of the trial. A total of 824 women were screened for eligibility. Of these, 309 were not randomized. The primary reason for non-randomization was ineligibility on inclusion or exclusion criteria (n = 220). Reasons for ineligibility were abstinence from sexual activity (n=115), or lack of unprotected sex occasions over the prior six months (n=71). Among women who were eligible but not randomized (n=89), 48 dropped out from their drug treatment program and 17 refused to enter the trial. Other less common reasons for non-randomization included loss to follow-up, moving, starting a new job, jail, childcare conflicts, or acute psychiatric problems. Thus, 515 women were randomized to the trial, of whom 3 did not complete the baseline assessment, and 131 did not complete either follow-up assessment, leaving 384 participants available in the intent to treat sample for the primary outcome analysis (74.6% of those randomized, 70.8% (177/250) in the SSB condition, and 78.1% (207/265) in the HE condition). A logistic regression model was fit to determine whether loss to follow-up was associated with intervention condition or patient characteristics measured at baseline, the results are displayed in Table 2. Loss to follow-up was more likely among non-monogamous participants (compared to those reporting a monogamous relationship) (F = 5.03, p < .03) and among participants in outpatient psychosocial treatment (compared to those in methadone maintenance) (F = 30.71, p < .0001). Neither age (F = 0.06, p = .80), race/ethnicity (F = 2.10, p = .08), nor years of education (F = 0.23, p = .63) were significantly associated with loss to follow-up. There was a trend toward greater loss to follow-up in the SSB condition (F = 3.62, p = .06). Rates of follow-up for each intervention condition at each assessment were: (1) SSB: 62% (155/250) = 3-month follow-up and 6-month follow-up; and (2) HE: 70% (186/265); 66% (177/265) = 6-month follow-up.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Flow Diagram of Participants through Study

Table 2.

Analysis of Potential Predictors of Missing Data at 3-Month and 6-Month Follow-Up

| Effecta | F-value | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.06 | .80 |

| Race/Ethnicity | 2.10 | .08 |

| Education (years) | 0.23 | .63 |

| Monogamy Status | 5.03 | .03 |

| Program (methadone vs. outpatient psychosocial) |

30.71 | <.001 |

| Intervention (SSB vs. HE) | 3.62 | .06 |

Degrees of freedom(df) = (1,413), except race/ethnicity, df = (4,413)

Baseline Data

Table 3 presents the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the SSB and HE samples for all randomized patients. There were no significant differences between treatment conditions and none of these baseline features was significantly associated with the outcome measure. About half of the sample was less than 40 years old. The majority were white (58%), with smaller proportions of African-Americans (24%), Hispanic/Latinos (9%) and other minorities (9%). Two-thirds (66%) had 12 years of education or less. The sample was split about evenly between those reporting monogamy and those reporting multiple male sexual partners, as well as methadone treatment versus outpatient psychosocial treatment. The sample had a mean of 19.3 unprotected sex occasions in the 3-month period before baseline. The sample had a mean of 2.22 days of the past 30 of cocaine use, and a mean of 1.30 days of heroin use.

Table 3.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants Randomized to Safer Sex Skills Building (SSB) and HIV Education (HE)a

| Effect | SSB (N=250) | HE (N=265) n (%) or M (SD) |

Total (N=515) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (%) | ||||

| ≤ 40 | 131 (52.4) | 148 (55.9) | 279 (54.2) | |

| > 40 | 119 (47.6) | 117 (44.2) | 236 (45.8) | |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | ||||

| White | 142 (56.8) | 156 (58.9) | 298 (57.9) | |

| Black/African American | 58 (23.2) | 67 (25.3) | 125 (24.3) | |

| Hispanic/Latina | 26 (10.4) | 20 (7.6) | 46 (8.9) | |

| Mixed or Other | 24 (9.6) | 22 (8.3) | 46 (8.9) | |

| Monogamy Status (% yes) | 139 (55.6) | 137 (51.7) | 276 (53.6) | |

| Program: Methadone (% yes) | 121 (48.4) | 134 (50.6) | 255 (49.5) | |

| Education (%) | ||||

| <12 | 66 (26.4) | 79 (29.2) | 145 (28.2) | |

| =12 | 90 (36.0) | 103 (39.0) | 193 (37.6) | |

| >12 | 94(37.6) | 82 (31.1) | 176 (34.2) | |

| Unprotected Sex Occasions | 18.60 (27.8) | 19.96 (33.4) | 19.3 (30.8) | |

| Cocaine Use Days In Past 30 Days | 1.96 (5.45) | 2.47 (6.03) | 2.22(5.75) | |

| Heroin Use Days In Past 30 Days | 1.54 (5.32) | 1.08 (4.61) | 1.30(4.97) | |

No significant differences between SSB and HE on any characteristic

Effects of Intervention on Sexual Risk Behavior

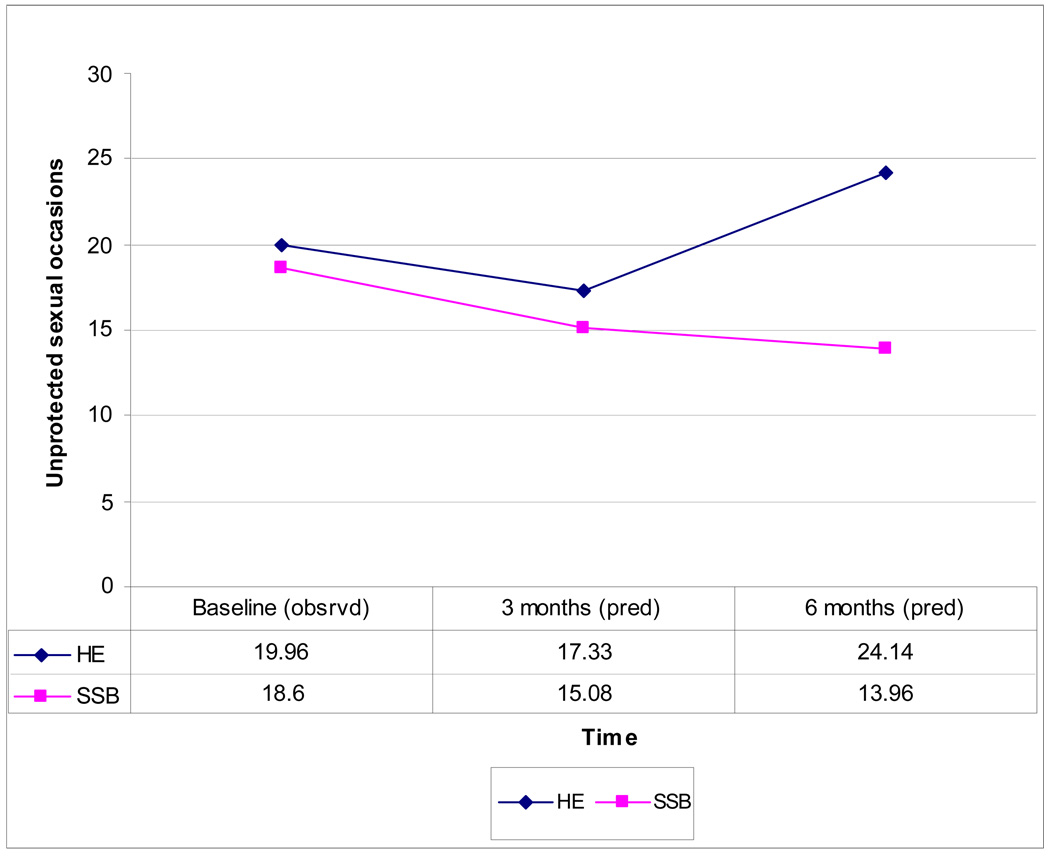

Table 4 presents a Mixed Effect Model showing the effects of intervention condition, time, and monogamy status, and baseline unprotected sexual occasions (USOs) on the primary outcome measure, number of USOs at 3- and 6 month follow-up. There is a significant time by intervention interaction (F = 67.2, p<.0001), which is displayed in Figure 2. At 3-month follow-up, both interventions produced significant declines in USOs from 18.6 to 15.08 in the SSB condition and 19.96 to 17.33 in the HE control condition. The interventions did not significantly differ from baseline to 3-month follow-up. However, at 6-month follow-up, the interventions did significantly differ (p <.0377). That is, participants in the SSB condition further reduced USOs to 13.96, while in the HE condition USOs increased to 24.14. This represents an effect size (standardized difference between predicted means) of 0.42. Based on the marginal model, women in the SSB condition had 29% fewer USOs than those in the HE condition at 6-month follow-up. As predicted, the main effect of monogamy status was significant (F = 24.42, p < .0001), reflecting that women reporting a single male sexual partner had 34% more USOs than those reporting multiple male partners.

Table 4.

Analysis of Intervention (SSB vs HE) Effects on Unprotected Sex Occasions (USO)

| Effecta | F-value | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline USOb | 71.55 | <.001 |

| Monogamy Statusc | 24.42 | <.001 |

| Intervention | 0.73 | ns |

| Time | 39.60 | <.001 |

| Time*Intervention | 67.18 | <.001 |

Degrees of freedom (df) = (1,177)

Baseline USO = logarithm transformed baseline count of unprotected sex occasions

Monogamy status = time dependent covariate measured at 3- and 6-month follow up

Figure 2.

Observed (Baseline) and Predicted Means (3- and 6-Month Follow Up) for Unprotected Sex Occasions

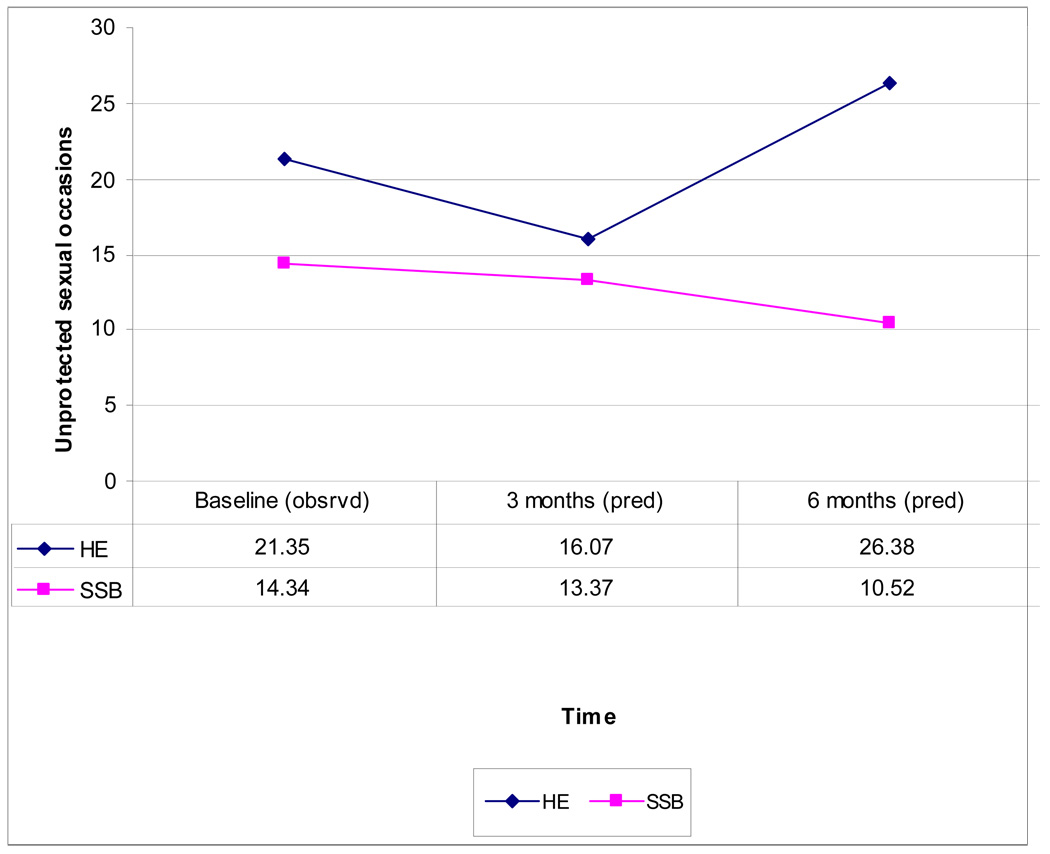

Although vigorous efforts (e.g. appointment cards, phone reminders, incentives, and other outreach) were made to engage and retain women in the interventions, dropout rates were sizeable. In HE, 62% completed the one group session. In SSB, 61% completed at least one group session, while 43% completed 3 or more sessions. When completer status (3 or more sessions of the 5-session SSB condition) was added as a covariate to the Mixed Effect Model, a significant intervention by completion status by time effect (F = 46.1, p < .0001) was obtained. As predicted, among treatment completers the advantage for the SSB condition was enhanced (predicted mean USOs in SSB at 3 month follow-up: 13.37, at 6-month follow-up: 10.52; compared to HE at 3 month follow-up: 16.07, at 6-month follow-up: 26.38). This reflects an effect size of 0.60 at 6-month follow-up. Based on the marginal model, women in the SSB condition had 43% fewer USOs than those in the HE condition at 6-month follow-up. This reflects a significant difference between the two intervention conditions (p<.0093).

There were a total of 52 serious adverse events (26 in each intervention condition). None of the adverse events were determined to be study-related.

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrates the effectiveness of a brief, gender-specific, group intervention, oriented toward safer sex skills building and condom use (SSB), in reducing unprotected sexual encounters among a high risk group of women in treatment for drug dependence. Both the SSB intervention and the HIV/STD education control condition, designed to reflect current usual care in the community, reduced unprotected sexual occasions at 3 months after the intervention. At 6 months after the intervention, the SSB and HE interventions significantly differed in change in USOs, from 3-month to 6-month follow-up. Unprotected sex returned to baseline level in the control condition, while the reductions in high-risk sex were sustained, and even further decreased, at 6 months among patients who received SSB, with an effect size (standardized difference between means) of 0.42 favoring SSB over control. This exceeds the smaller effect size of 0.26 noted in meta-analyses of prior clinical trials of HIV risk reduction interventions in similar at-risk populations.10, 13 This also surpasses the tendency for deterioration over time frequently observed.4, 13

These results demonstrate an important caution in this literature. While psychoeducational intervention can be successful in initiating safer sexual behavior, maintenance of this behavior requires more hands-on, evocative and empowering methods of intervention.4, 5, 13 Due to gendered constraints in heterosexual relationships this may be especially true for women. Thus, while both interventions were effective in prompting initial post-intervention change in USOs, only SSB skills building maintained this change in the complex sexual risk outcomes of the study. A possible mechanism for this may be a so-called sleeper effect - used to describe the ‘delayed emergence of effects for cognitive-behavioral therapy over a psychotherapy control condition’ in a trial of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy for cocaine dependence.37 Sleeper effects have also been observed in trials of contraception outreach in heterosexual couples in Ethiopia.38 Thus, the persistence of reduced sexual risk behavior after 6 months among patients receiving the SSB intervention in this trial is particularly encouraging.

Several features of the study design suggest that the effectiveness of the SSB intervention should have broad generalizability. The use of a hybrid efficacy/effectiveness trial, comparing SSB to treatment-as-usual HE, provided the research frame in which to pose the question of whether or not SSB was effective under real world circumstances.16 To account for variation between different treatment programs and to be able to infer the statistical results to larger populations of clinical programs, site was treated as a random effect 39, 40, as recommended for effectiveness trials. The participating programs were all affiliates of the NIDA CTN and thus do not represent a purely random sample of all U.S. programs. Nonetheless, these were all community-based treatment programs, not otherwise university-affiliated, nor part of tertiary care centers. The effect of the random factor site was significant, meaning there is variation in outcome overall across treatment programs. The current analysis does not assess variation in the intervention effect size (SSB vs HE difference) across program type (e.g., methadone versus outpatient psychosocial) or region. Importantly, the interventions in this trial were conducted by local drug counselors, after a brief initial training and with some ongoing supervision. This suggests that the SSB intervention does not necessarily require advanced degrees or specialized expertise, but rather is effective in the hands of practicing community-based clinicians.

The study also has limitations and highlights opportunities for further improvement of HIV risk reduction efforts. While the use of the (1-session) HE control condition provided comparison of (5-session) SSB with standard community practice, it also presented the problem of imbalance in intensity. This design does not permit definitive attribution of outcome differences between these conditions to intervention modality, rather than dose. Research, comparing SSB skill modules (e.g. male and female condom use skill, safer sex negotiation skill, etc.) is needed to unpack the impact of the major components of SSB, of equal attention.

As hypothesized, and consistent with prior observations,17–19 women reporting only a main male partner had more unprotected sexual occasions at follow-up than those reporting multiple partners. Monogamy itself may be protective against risk of contracting HIV or STDs, especially in regions where the prevalence of disease is low. However, high rates of hidden male infidelity or seropositivity may undermine the protective effects of monogamy.41, 42 Thus, future interventions should focus more on monogamy and condom use.

The rate of non-adherence to treatment was greater than desired and may have reflected, in part, the well-known difficulty of engaging drug dependent patients in treatment due to chaotic lifestyles. At the same time, the effect size of 0.60 achieved among women who attended at least 3 of 5 group sessions represents an impressive reduction in high-risk behavior, and suggests what might be achieved with greater adherence. It is likely that if, as meta-analyses suggest,4, 10 these interventions could be fully integrated into the core substance abuse treatment curriculums of these programs, adherence would be greatly enhanced. There are precedents for this in the adoption of Contingency Management and Motivational Interviewing in community-based drug treatment settings.43, 44 Further, adding Contingency Management or Motivational Interviewing, to improve adherence to safer sex skills building intervention, would be a worthwhile next step for future study.

Loss to follow-up was also greater than anticipated or desired, and poses a potential threat to the external validity of the outcome results. To attempt to correct for this, we conducted intent to treat analyses, incorporating the broadest possible sample and affording us the most realistic view of the effectiveness of the intervention. It should also be noted that much of the attrition was linked to drop-out from the drug treatment program itself, rather than from the trial alone. This observation offers an important practical caution for the integration of HIV prevention intervention into standard community practice. That is, it is probably more practical to initiate adjunct HIV prevention intervention once attendance in drug treatment has been established. Had there been an attendance criterion for entry into the trial, attrition would likely have been reduced, and the sample would have been more representative of individuals engaged in community drug treatment. One might expect an increased intervention dose to result in more robust treatment effects.

The study did not measure actual disease transmission (new incidence of HIV or other STDs), as this would have required a much larger sample. However, the primary outcome of unprotected vaginal or anal intercourse has been clearly linked to transmission risk. Further, even modest reductions in unprotected sex have been shown to have public health significance in reducing disease transmission.10

HIV and other STDs remain a substantial and costly threat to public health. By demonstrating the effectiveness of a brief, gender specific, skills oriented risk reduction intervention, delivered by drug treatment staff at community-based clinics, this study suggests a model that could be applied more widely in primary care settings where high risk women are treated (i.e., urban primary care, obstetrics-gynecology, or HIV clinics). A key ingredient of the effectiveness observed here, in addition to the design of the intervention itself, may have been the ongoing supervision the counselor-interventionists received. This is consistent with the literature on continuing medical education, which shows that feedback and supervision are essential to the development of new clinical skills.45 The train-the-trainer model implemented here, where local clinicians trained and functioned as supervisors with backup from experts, has particular promise for sustainability. Future research should examine the effectiveness of this or similar HIV risk reduction interventions conducted by nursing or other allied health care workers across various primary care settings.

Figure 3.

Observed (Baseline) and Predicted Means (3- and 6- Month Follow-up) for Unprotected Sex Occasions (Non-Completers)

Figure 4.

Observed (Baseline) and Predicted Means (3- and 6- Month Follow-up) for Unprotected Sex Occasions (Completers)

Table 5.

Analysis of Intervention (SSB vs HE) and Completion Effects on Unprotected Sex Occasions (USO)

| Effecta | F-value | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline USO b | 70.36 | <.001 |

| Monogamy Status c | 35.38 | <.001 |

| Intervention | 0.61 | ns |

| Completion | 3.83 | .05 |

| Time | 4.75 | .03 |

| Intervention*Time | 15.76 | .001 |

| Completion*Time | 48.50 | <.001 |

| Intervention*Completion | 0.87 | ns |

| Intervention*Time*Completion | 46.12 | <.001 |

Degrees of freedom (df) = (1,175)

Baseline USO = logarithm transformed baseline count of unprotected sex occasions

Monogamy status = time dependent covariate measured at 3- and 6-month follow up

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the women who participated in all phases of the study and for sharing information with us about their lives. The authors also thank the two anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful and constructive suggestions.

Role of the Sponsor: The NIDA CTN collaborated in the design and conduct of the study, and NIDA CTN staff assisted in the management, analysis, and interpretation of the data and provided comments for consideration in drafts of the manuscript.

Safer Sex for Women Study Research Group: The NIDA Clinical Trials Network (CTN) is made up of “nodes” comprised of a Regional Research and Training Center (RRTC) housed at an academic institution and 5–10 Community Treatment Programs (CTP). The Long Island Node served as the lead node. The contributions from each participating CTN node are provided: Washington Node RRTC, University of Washington Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute, Seattle, Washington. Co-Lead investigator and RRTC investigator: Donald Calsyn; national project managers, Sara Berns, Mary Hatch-Maillette; local project manager, Mary Hatch-Maillette; lead quality assurance, Donna Hertel; lead data management, Molly Carney, Michael Dudley, Brooke Leary, Viki Stanmour, Katie Weaver; lead node coordinator, Brenda Stuvek; lead training director, John Baer. Washington Node CTP, Evergreen Treatment Services, Seattle, WA. Site investigator, T. Ron Jackson; research coordination, Megan Swan Foster, Esther Ricardo-Bullis; intervention therapists and supervisors, Carol Davidson, Denise Ledbetter, Lorna McKenzie. Delaware Valley Node RRTC, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. Data/QA/protocol management, Charlotte Royer-Malvestuto. Delaware Valley Node CTP, The Consortium, Philadelphia, PA. Site investigator, Mark Hirschman; research coordination, Sheila Clark, Evette Wilson; intervention therapists and supervisors, Shahidah Faruqui, Marie Guerrier, Tyra Hadley, Evette Wilson. Delaware Valley Node CTP, Thomas Jefferson Intensive Substance Abuse Treatment Program, Philadelphia, PA. Site investigators, Robert Sterling, Stephen Weinstein; research coordination, Ellen Fritch, Carolynn Laurenza, Diane Losardo; intervention therapists and supervisor, Tomeka Ragin, Sari Trachtenberg, Debora Wittington. Long Island Node RRTC, Columbia University, New York, NY. Co-lead investigator and RRTC investigator, Susan Tross; protocol/data/quality assurance management, Aimee Campbell, Terri DeSouza, Megan Ghiroli, Jennifer Lima, Karen Loncto, Jennifer Manual, Jim Robinson. Long Island Node CTP, Staten Island University Hospital, Staten Island, NY. Research coordination, Megan Ghiroli, Marissa Malick; intervention therapists and supervisors, Joe Grossman. North Carolina Node RRTC, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC. RRTC investigator, Leonard Handelsman*; data/QA/protocol management, Tammy Day, Tamara Owens; North Carolina Node CTP, Alcohol Drug Services, Highpoint, NC. Site investigator, Jackie Butler; research coordination, Makeba Casey, Lester Flemming*. Intervention therapists and supervisors, Allanda Edwards. North Carolina Node CTP, Southlight, Inc., Raleigh, NC. Site investigator, Tad Clodfelter; research coordination, Allison Hartsock, Denise McRae, Tracey Vann. New England Node RRTC, Yale University, New Haven, CT. RRTC investigator, Samuel Ball; data/QA/protocol management, Julie Matthews, Kristie Smith. New England Node CTP, Hartford Dispensary, Hartford, CT. Research coordination, Brandi Buchas, Nicole Moodie; intervention therapists and supervisors, Leyla Miranda, Sarah Sperrazza, Denisse Vazquez. Ohio Valley Node, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinatti, OH. RRTC investigator, Judy Harrer; data/QA/protocol management, Emily DeGarmo, Peggy Samoza. Ohio Valley Node CTP, Comprehensive Addiction Services System, Toledo, OH. Research coordination, Al Woods; intervention therapists and supervisors, Al Woods. Ohio Valley Node CTP, Prestera Center for Mental Health Services, Inc., Huntington, WV. Site investigator, Genise Lalos; research coordination, Parrish Harless, Tara Lee; intervention therapists and supervisors, April Fetty. Pacific Node RRTC, University of California-Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA. RRTC investigator, Sara Simon; data/QA/protocol management, David Bennett, Sara Simon. Pacific Node CTP, Bay Area Addiction Research & Treatment, Los Angeles, CA. Site Investigator, Al Cohen. South Carolina Node RRTC, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC. RRTC Investigator, Therese Killeen; Data/QA/protocol management, Stephanie Gentilin, Royce Sampson. South Carolina Node CTP, Lexington/Richland Alcohol and Drug Council, Columbia, SC. Site investigator, Louise Haynes; research coordination, Beverly Holmes, Kimberly Pressley; intervention therapists and supervisors, Louise Haynes, Susan H. Coggins, Cynthia Longworth.**

*At the time of manuscript preparation, these study staff members were deceased and written permission to be acknowledged could not be obtained.

**Many additional investigators, research staff, and intervention therapists and supervisors across sites contributed to this project, but could not be contacted for written permission to be acknowledged in this paper.

Sources of Support: This study was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Clinical Trials Network grants: U10 DA13035 (Edward Nunes, PI), U10 DA13714 (Dennis Donovan, PI), U10 DA13043 (George Woody, PI), U10 DA13038 (Kathleen Carroll, PI), U10 DA13711 (Robert Hubbard, PI), U10 DA13732 (Eugene Somoza, PI), U10 DA13045 (Walter Ling, PI), U10 DA13727 (Kathleen Brady, PI)

Footnotes

Portions of this data were presented at the 69th Annual Scientific Meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence, Quebec City, Quebec, June 2007; The American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry 18th Annual Meeting and Symposium, Coronado, CA, November 2007; The American Psychological Association 115th Annual Convention, San Francisco, CA, August 2007

Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov, A Service of the US National Institutes of Health, Number NCT00084188, http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/

REFERENCES

- 1.Des Jarlais D, Arasteh K, Perlis T, et al. Convergence of HIV seroprevalence among injecting and non-injecting drug users in New York City. AIDS. 2007;21(2):231–235. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3280114a15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Latkin C, Curry A, Hua W, Davey M. Direct and indirect associations of neighborhood disorder with drug use and high-risk sexual partners. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(6):5234–5241. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ball J, Ross A. The effectiveness of methadone maintenance treatment. New York: Springer Verlag; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prendergast M, Urada D, Podus D. Meta-analysis of HIV risk-reduction interventions within drug abuse treatment programs. J Consult Clin Psych. 2001;69(389–405) doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.3.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeHovitz J, Kelly P, Feldman J. Sexually transmitted diseases, sexual behavior, and cocaine use in inner-city women. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;140:1125–1134. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edlin B, Irwin K, Faruque S. Intersecting epidemics: Crack cocaine use and HIV infection among inner-city young adults. New Engl J Med. 1994;(331):1422–1427. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199411243312106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Metzger D, Navaline H, Woody G. Drug abuse treatment is AIDS prevention. Pub Health Report. 1998;113(suppl 1):97–106. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sorensen J, Copeland A. Drug abuse treatment as an AIDS prevention strategy: A review. Drug Alcohol Depen. 2000;59:17–31. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00104-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shoptaw S, Tross S, Stephens M, Tai B the NIDA CTN HIV/AIDS Workgroup. A snapshot of HIV/AIDS-related services in the clinical treatment providers for NIDA’s Clinical Trials Network. Drug Alcohol Depen. 2002;66(suppl 1):S163. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Copenhaver M, Johnson B, Lee I, Harman J, Carey M the SHARP Research Team. Behavioral HIV risk reduction among people who inject drugs: Meta-analytic evidence of efficacy. J Subst Abuse Trea. 2006;31:163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Semaan S, Des Jarlais D, Sogolow E, et al. A meta-analysis of the effect of HIV prevention interventions on the sex behaviors of drug users in the United States. J Acq Immun Def Synd. 2002;30(suppl 1):S73–S93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Exner T, Seal D, Ehrhardt A. A review of HIV interventions for at-risk women. AIDS Beh. 1997;2:93–124. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Logan T, Cole J, Leukefeld C. Women, sex, and HIV: Social and contextual factors, meta-analysis of published interventions, and implications for practice and research. Psychol Bull. 2002;128(6):851–885. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.6.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Bassel N, Schilling R. 15-month follow-up of women methadone patients taught skills to reduce heterosexual HIV transmission. Pub Health Report. 1992;107:500–504. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schilling R, El-Bassel N, Schinke S, Gordon K, Nichols S. Building skills of recovering women drug users to reduce heterosexual AIDS transmission. Pub Health Report. 1991;106(3):297–304. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carroll K, Rounsaville B. Bridging the gap: A hybrid model to link efficacy and effectiveness research in substance abuse treatment. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54:333–339. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.3.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Exner T, Hoffman S, Dworkin S, Ehrhardt A. Beyond the male condom: The evolution of gender-specific HIV interventions for women. Annu Rev Sex Res. 2003;14:114–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Misovich S, Fisher J, Fisher W. Close relationships and elevated HIV risk behavior: Evidence and possible underlying psychological processes. Rev Gen Psychol. 1997;1:72–107. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simoni J, Walters K, Nero D. Safer sex among HIV+ women: The role of relationships. Sex Roles. 2000;42(7/8):691–708. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Needle R, Fisher D, Weatherby N, et al. Reliability of self-reported HIV risk behaviors of drug users. Psychol Addict Behav. 1995;9(4):242–250. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weatherby N, Needle R, Cesari H, et al. Validity of self-reported drug use among injection drug users and crack cocaine users recruited through street outreach. Eval Program Plann. 1994;17:347–355. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cockrell J, Folstein M. Mini-Mental State Examination. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24:689–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Folstein M, Folstein S, McHugh P. ‘Mini-Mental State’: A practical method for grading cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiat Res. 1975;12:196–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meyer-Bahlburg H, Ehrhardt A, Exner T, et al. Sexual Risk Behavior Assessment Schedule—Adult—Armory Interview. New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 25.McLellan A, Kushner H, Metzger D, et al. The fifth edition of the Addiction Severity Index. J Subst Abuse Trea. 1992;9(3):199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dolezal C, Meyer-Bahlburg H, Liu X, et al. Longitudinal changes in sexual risk behavior among HIV+ and HIV− male injecting drug users. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1999;25(2):281–303. doi: 10.1081/ada-100101861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ehrhardt A, Exner T, Hoffman S, et al. A gender-specific HIV/STD risk reduction intervention for women in a health care setting: short- and long-term results of a randomized clinical trial. AIDS Care. 2002;14(2):147–161. doi: 10.1080/09540120220104677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.NIMH Healthy Living Project Team. Effects of a behavioral intervention to reduce risk of transmission among people living with HIV: The Healthy Living Project randomized controlled study. J Acq Immun Def Synd. 2007;44(2) doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31802c0cae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Des Jarlais D, Paone D, Milliken J, et al. Audio-computer interviewing to measure risk behavior for HIV among injecting drug users: A quasi-randomized trial. Lancet. 1999;353:1657–1661. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)07026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Metzger D, Koblin B, Turner C, et al. Randomized clinical trial of audio computer-assisted self-interviewing: Utility and acceptability in longitudinal studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(2):99–106. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Najavits L, Crits-Cristoph P, Dierberger A. Clinicians’ impact on the quality of substance abuse disorder treatment. Subst Use Misuse. 2000;35:2161–2190. doi: 10.3109/10826080009148253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown H, Prescott R. Applied Mixed Models In Medicine. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bryk A, Raudenbush SW. Hierarchical Linear Models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diggle P, Liang K, Zeger S. Analysis of Longitudinal Data. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Little R, Rubin D. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. New York: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 36.SAS software system for windows [computer program]. Version 9.1. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carroll K, Rounsaville B, Nich C, Gordon L, Wirtz P, Gawin F. One year follow-up of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for cocaine dependence: Delayed emergence of psychotherapy effects. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:989–997. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950120061010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Terefe A, Larson C. Modern contraception use in Ethiopia: Does involving husbands make a difference? Am J Public Health. 1993;83(11):1567–1571. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.11.1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feaster D, Robbins M, Horrigan V, Szapocznik J. Statistical issues in multi-site effectiveness trials: The case of Brief Strategic Family Therapy for adolescent drug abuse treatment. Clin Trial J. 2004;1:1–12. doi: 10.1191/1740774504cn041oa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Littell R, Stroup W, Freund R. SAS for linear models. 4th ed. SAS Publishing; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hirsch J, Higgins J, Bentley M, Nathanson C. The social constructions of sexuality: Marital infidelity and sexually transmitted disease - HIV risk in a Mexican migrant community. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(8):1227–1237. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.8.1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sobo E. Choosing unsafe sex: AIDS-risk denial among disadvantaged women. Philadephia: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carroll K, Ball S, Nich C, et al. Motivational interviewing to improve treatment engagement and outcome in individuals seeking treatment for substance abuse: A multisite effectiveness study. Drug Alcohol Depen. 2006;81(3):301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Petry N, Simcic F. Recent advances in the dissemination of contingency management techniques: clinical and research perspectives. J Subst Abuse Trea. 2002;23(2):81–86. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00251-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davis D, O'Brien M, Freemantle N. Impact of formal continuing medical education: Do conferences, workshops, rounds, and other traditional continuing education activities change physician behavior or health care outcomes? JAMA. 1999;282(9):867–874. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.9.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]