Abstract

AIMS

Prescribing errors are an important cause of patient safety incidents, generally considered to be made more frequently by junior doctors, but prevalence and causality are unclear. In order to inform the design of an educational intervention, a systematic review of the literature on prescribing errors made by junior doctors was undertaken.

METHODS

Searches were undertaken using the following databases: MEDLINE; EMBASE; Science and Social Sciences Citation Index; CINAHL; Health Management Information Consortium; PsychINFO; ISI Proceedings; The Proceedings of the British Pharmacological Society; Cochrane Library; National Research Register; Current Controlled Trials; and Index to Theses. Studies were selected if they reported prescribing errors committed by junior doctors in primary or secondary care, were in English, published since 1990 and undertaken in Western Europe, North America or Australasia.

RESULTS

Twenty-four studies meeting the inclusion criteria were identified. The range of error rates was 2–514 per 1000 items prescribed and 4.2–82% of patients or charts reviewed. Considerable variation was seen in design, methods, error definitions and error rates reported.

CONCLUSIONS

The review reveals a widespread problem that does not appear to be associated with different training models, healthcare systems or infrastructure. There was a range of designs, methods, error definitions and error rates, making meaningful conclusions difficult. No definitive study of prescribing errors has yet been conducted, and is urgently needed to provide reliable baseline data for interventions aimed at reducing errors. It is vital that future research is well constructed and generalizable using standard definitions and methods.

Keywords: drug prescription, medication error, physicians

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS SUBJECT

Prescribing errors account for a substantial proportion of medication errors and cause the most significant problems.

There is a dearth of accurate information on the prevalence of prescribing errors, with estimates from 1 to 100% of all patients admitted to hospital.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This review reports the wide ranges of error rates seen, which cannot be compared due to differences in methodology and error definitions used.

A well-conducted study of prescribing errors by junior doctors using standard definitions and methodology is urgently needed to allow development and assessment of appropriate interventions.

Introduction

Medication errors are the second most common cause of patient safety incidents [1], with prescribing errors an important component of these [2]. Using Human Error Theory [3], errors can be divided into individual and systems factors. Although much of the current emphasis in patient safety is on systems factors, individual doctors' actions are also important. In a study of prescribing errors using Human Error Theory, Dean et al.[4] reported that 43% of errors were mistakes or violations, whereas 57% were lapses. This suggests that knowledge-based errors are important and could potentially be addressed by educational interventions at undergraduate or postgraduate level. Focusing interventions on medical students and junior doctors is appropriate for two reasons. First, junior doctors are responsible for the majority of actual prescribing in hospitals (having been reported as responsible for 91% of prescribing errors [4]), although they may not be responsible for all prescribing decisions. Second, training at these stages may be more effective and efficient than at a later point in a doctor's career. In order to design interventions, it is important to understand the nature of individual factors and the size of the problem. However, there is a dearth of consistent information on the prevalence of prescribing errors. Prescribing errors are reported to affect 1–100% of all patients admitted to hospital [5].

In order to clarify the situation, a systematic review of the current published evidence to answer the research question ‘how many prescribing errors are committed by junior doctors’ was undertaken.

Methods

We included studies of any experimental design that addressed prescribing errors, involved junior doctors, were published since 1990 in English, from the UK, Europe, North America, Australia or New Zealand, and were conducted in primary or secondary care. Junior doctors are defined as foundation doctors, junior house officers, senior house officers or registrars in the UK and interns, residents or fellows in other countries.

The search strategy included the terms prescription, prescribing, junior doctors and error (see Appendix 1). Searches were undertaken in July 2007 using the following databases: MEDLINE; EMBASE; Science and Social Sciences Citation Index; Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL); Health Management Information Consortium; PsychINFO; ISI Proceedings; The Proceedings of the British Pharmacological Society; Cochrane Library; National Research Register; Current Controlled Trials; Index to Theses; and Internet via Google. Subsequent automatic alerts were generated. In addition, hand searching of the reference lists from included studies was carried out by one researcher (S.R.).

Citation titles retrieved in the search were each independently reviewed against the inclusion criteria by two researchers (S.R. and M.J.M. or C.B.). Abstracts associated with included titles were then retrieved and again each reviewed by two researchers (S.R. and C.B.). Finally, full papers for potentially eligible studies were retrieved and independently reviewed by two researchers (H.R. and S.T.). Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Data abstraction from full papers was undertaken independently by two researchers (H.R. and S.T.) with differences resolved by consensus with a third researcher (S.R.). A form, based on the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network [6] and the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme [7], was developed to support consistent abstraction of data to answer the research question. It contained the following information: study design, study aim, participants, setting, possible confounding, methods of data collection, blinding, statistical analysis, definitions used and outcomes. The form was piloted, refined and finalized by consensus.

The methodological quality of the studies was subjectively rated independently by S.T. and H.R. using a modified version of the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies [8]. The following aspects were assessed: study aim, participant selection, control of confounding, data collection, assessor blinding, participant blinding, statistical analysis and withdrawals. A summary grade – strong, moderate or weak – was then assigned to each criterion. Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

It was anticipated that the selected studies would not be amenable to meta-analysis, and narrative qualitative analysis was planned. Where possible, published data were computed to a ‘common unit of measurement’.

Results

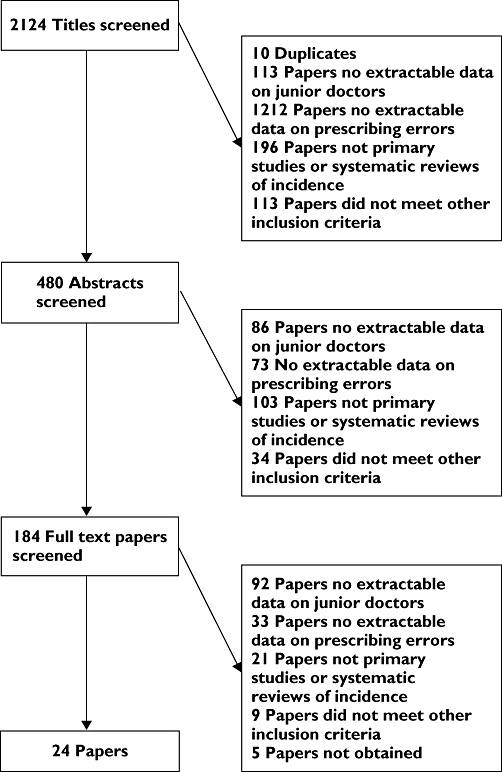

Initial searching identified 2091 studies. A further 28 were added from MEDLINE/EMBASE alerts and five from hand-searching of references, giving a total of 2124. A flowchart illustrating the progressive study selection and numbers at each stage is shown (Figure 1). Five papers, not available via interlibrary loan within the UK, were excluded. Twenty-four studies met the inclusion criteria.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of included studies

Eight studies were undertaken in the UK, 10 in the USA, four in Canada and one each in Australia and the Netherlands. The majority were conducted in a hospital environment.

The majority of studies were observational; two were described as randomized controlled trials but were judged to be observational studies. Eighteen studies were prospective and six retrospective.

Seven papers were categorized as methodologically strong with regard to study aim, none in selection of participants, three for controlling confounding, five for data collection, four for blinding of assessors, five for blinding of participants, three for statistical analysis and seven for withdrawals (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Overall methodological quality of included studies

| Overall grade n (%) | Study aim | Selection of participants | Control of confounding | Data collection | Blinding of assessors | Blinding of participants | Statistical analysis | Withdrawals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strong | 7 (29) | 0 | 3 (13) | 5 (21) | 4 (17) | 5 (21) | 3 (13) | 7 (29) |

| Moderate | 16 (67) | 19 (79) | 7 (29) | 14 (58) | 15 (62) | 7 (29) | 6 (25) | 0 |

| Weak | 1 (4) | 5 (21) | 14 (58) | 5 (21) | 5 (21) | 12 (50) | 15 (62) | 17 (71) |

A number of specific issues were identified that limit comparisons. First, there was no consistent definition of error across studies, with different combinations of 35 possible criteria being used. Of these, wrong dose was the most commonly used (15 studies), nine criteria were only used by two studies and 12 by only one study. Table 2 shows an abbreviated list of possible criteria used in defining prescribing errors. These could be grouped into those that are a potential danger to the patient (wrong drug, dose, allergy), those that may be a danger or merely require clarification (e.g. some interactions, or medicines causing computer alerts), and those that increase the cost of the medicine (e.g. brand name use, nonformulary items).

Table 2.

Error definitions

| Criteria | Number of studies using |

|---|---|

| Wrong dose | 15 |

| Wrong frequency | 14 |

| Omitted information | 11 |

| Wrong route | 8 |

| Contraindicated due to allergy | 6 |

| Wrong drug | 6 |

| Inaccurate information | 5 |

| Other contraindication | 5 |

| Definition from Dean [32] | 4 |

| Illegibility | 4 |

| Interaction | 4 |

| Unclear quantity | 4 |

| Illegality | 3 |

| Wrong patient | 3 |

Second, data collection methods varied between studies, leading to possible biases and different error rates. Units for reporting of error rates or numbers varied, but could be roughly grouped into three types: errors made by junior doctors per single medication item (n = 11); errors made by junior doctors per whole drug chart (multiple medications) or per patient (n = 9); and absolute numbers of errors made by junior doctors (n = 4). Even within these groups, there were inconsistencies. For example, those reporting per item rates report either for items written by the junior doctors or all items prescribed by any doctor. One study reported the percentage of errors made by juniors of all errors made by any doctor. For these reasons, the data are presented by individual study expanding on each issue, with a summary of the findings reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of included primary studies

| Study | Study design | Setting and subjects | Error definition | Intervention (if applicable) | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lesar et al. (1990) [9] | Prospective observational | Setting: 640-bed tertiary care teaching hospital (secondary care) Subjects: Adult and paediatric patients (21 464 admissions during study period; Physicians (n = 840, of which 378 house staff and fellows) | Incorrect patient, drug, dosage, frequency, form, route, inappropriate or redundant indication, contraindicated medications (including allergies), or orders with critical information missing | None | 905 errors out of 289 411 orders were identified (3.1 per 1000 items). 864 errors were made by junior staff (95.7%), giving a calculated error rate of 3 errors made by junior staff per 1000 items prescribed by all doctors |

| Bordun and Butt (1992) [10] | Retrospective observational | Setting: children's hospital Subjects: paediatric patients (n = 202) admitted to a multidisciplinary ICU; doctors (n = not reported) prescribing in the ICU | Wrong patient, wrong drug, wrong dose, wrong frequency, incompatibility or a recognized drug–drug interaction | None | During the study period, 68 of 1518 medication orders were judged to be errors (45 per 1000). Only 53 errors could be traced to the prescriber, of which 46 (87%) were made by junior staff. After adjustment for those errors not accounted for, this gives a calculated error rate of 38 errors made by junior staff per 1000 items prescribed by all doctors |

| Ho et al. (1992) [11] | Prospective observational | Setting: 580-bed tertiary care teaching hospital Subjects: patients and doctors and in this hospital (n = not reported). | Any order that contained an inaccuracy or omission, or commenced potentially detrimental therapy and was captured as error or discussed and changed with the prescriber. Errors already detected and addressed by the ward pharmacy staff were not included in the study | None | In the study period, 237 798 items were prescribed, giving an overall rate of 5 errors per 1000 items. Residents had a reported error rate of 2 per 1000 items prescribed by all doctors |

| Howell and Jones (1993) [12] | Prospective observational | Setting: family practice centre (primary care) Subjects: patients (n = not reported) at a family practice centre; 1st year family practice residents (n = 8) | Omitted prescription information, wrong dose or frequency, unclear quantity or directions, a prescription for a nonprescription product or failure to comply with legislation | In-service training was provided to all 1st year residents in prescription writing and to review common prescription writing errors | At baseline, 23 errors were identified in 128 medication orders and 34 out of 172 post intervention. This is reported as 179 per 1000 items written by juniors pre intervention and 197 per 1000 items written by juniors post intervention |

| Bizovi et al. (2002) [13] | Retrospective observational | Setting: teaching hospital Emergency Department (secondary care) Subjects: patients (n = 1459 + 1056) attending department; doctors (n = not reported): faculty physician, residents | Any prescription that required clarification by the pharmacy department, which were subsequently shown to be related to missing or incorrect information (drug, dose, frequency, route or formulation), incorrect dose, legibility or use of nonformulary medication | Introduction of computer-assisted prescription writing | Pre-intervention there were 32 errors in 1280 items made by residents, which calculates as 25 errors per 1000 items written by juniors. Post intervention, 6 of 1114 were made by residents (calculated 5 errors made by junior staff per 1000 items prescribed by all doctors) |

| Dean et al. (2002) [14] | Prospective observational | Setting: teaching hospital (single centre) Subjects: inpatients (n = 459 hospital episodes); doctors (n = not reported) in a 550-bed teaching hospital | In accordance with Dean's Delphi study of prescribing errors [32] | None | In 36 168 orders, there were 538 errors. Of these errors, the prescriber could be identified in 482, of which 472 errors (98%) were made by junior staff (calculated rate is 15 errors per 1000 total items) |

| Fijn et al. (2002) [15] | Retrospective cross-sectional | Setting: two teaching hospitals. Subjects: patients (n = not reported) requiring a prescription; clinicians (senior doctors) and clinician assistants (junior doctors) (n = not reported) | Errors in dose, therapeutic errors, illegible prescription, missing data on date, patient or prescriber, unclear drug name, wrong drug, unauthorized abbreviation use, or route missing/inaccurate | None | There were 449 errors in 1913 prescription items written by any doctor (assumed as not explicit in paper), giving a rate of 235 errors per 1000 items. Junior doctors were 1.57 times more likely to cause an error than senior staff (calculated as 143 errors made by junior staff per 1000 items prescribed by all doctors) |

| Anton et al. (2004) [16] | Prospective observational | Setting: 64-bed renal unit in a teaching hospital Subjects: renal patients (n = 257); doctors (n = 42; 9 consultants, 13 registrars, 6 SHOs, 14 PRHOs) prescribing in the renal unit | Alerts generated by a computerized prescribing system were used as a proxy measure for potential errors | Routine use of a computerized prescribing system by doctors and nurses on a renal unit | There were 6592 alerts, of which junior doctors received 5462 warning alerts. Of these warnings, 2820 were ignored, suggesting that 2642 warnings reflected true errors (calculated as 514 errors made by junior staff per 1000 items prescribed by juniors) |

| Hendey et al. (2005) [17] | Retrospective observational | Setting: university affiliated community teaching hospital (secondary care) Subjects: adult inpatients (n = not reported) in medical/surgical wards and critical care areas; doctors: (n = 57) residents of various grades | Any error identified by the pharmacist, excluding simple clarifications that did not result in a change | None | There were 177 errors in 8195 medication orders (reported as 22 errors made by junior staff per 1000 items prescribed by juniors) |

| Stubbs et al. (2006) [18] | Retrospective observational | Setting: eight acute or mental health trust centres and one independent psychiatric hospital Subjects: patients (n = not reported) attending psychiatric hospitals; consultant and nonconsultant psychiatrists (n = not reported) | In accordance with Dean's Delphi study of prescribing errors [32] | None | Nonconsultant staff made 329 of the 523 errors (63%), calculated as a rate of 15 errors made by junior staff per 1000 items prescribed by all doctors |

| Walsh et al. (2006) [19] | Retrospective observational | Setting: urban teaching hospital (secondary care) Subjects: patient admissions (n = 352); paediatric and surgical residents (n = not reported) | All medication errors, defined as all errors in drug ordering, transcribing, dispensing, administering or monitoring | None | There were 104 errors in 6916 medication orders made by residents for 352 admissions, calculated as 15 medication errors per 1000 total items. No breakdown of errors is given, therefore prescribing error data cannot be extracted |

| Shaughnessy et al. (1991) [20] | Prospective observational | Setting: university-affiliated outpatient family medicine teaching centre (primary care) Subjects: patients attending (n = not reported); family practice residents (n = 20) in their 1st, 2nd or 3rd year of training | Major or minor omissions of critical information, dose or direction error, failure to meet legal requirements, nonprescription product, unclear quantity, or incomplete chart | Physician education using copies of prescriptions written by study participants to provide feedback on prescription-writing skills | 21% of charts contained an error prior to the intervention and 17% after the intervention |

| Shaughnessy and D'Amico (1994) [21] | Prospective observational | Setting: community hospital outpatient family medicine teaching centre (primary care) Subjects: patients attending (n = not reported); family practice residents (n = 12) in their 1st or 2nd year of training | Major or minor omissions of critical information, dose or direction error, failure to meet legal requirements, nonprescription product, unclear quantity, or incomplete chart | An educational programme consisting of evaluation and feedback of prescription writing by a clinical pharmacist | At baseline 14.4% of drug charts contained an error, with 6% post intervention |

| Kozer et al. (2002) [22] | Retrospective observational | Setting: paediatric hospital emergency department Subjects: patient (n = 1532) attending department; doctors (n > 80) defined as staff and trainees (interns, residents and fellows) | Wrong dose, wrong route of administration, wrong timing or wrong units | None | The authors report that junior doctors were 1.5 times more likely to commit an error than senior doctors, this would calculate as 162 errors of the total 271, written in 154 charts (2.1 errors made by junior staff per 1000 charts written by all doctors) |

| McFadzean et al. (2003) [23] | Prospective observational | Setting: medical admissions unit in a district general hospital Subjects: patients admitted as medical emergencies (n = 120); junior doctors (n = 12) towards the end of the preregistration house officer year/clinical pharmacists (n = 4) | Prescribing errors were defined as drugs omitted or prescribed in error, errors in dosage or frequency, or known drug allergies not recorded. Drug chart errors were defined as: illegible hand writing, use of lower case, inappropriate use of drug trade names, abbreviation of micrograms or units, omission of date, prescriber's signature, site for topical preparations, frequency, maximum dose and no reason for ‘as required’ medicines | None | The total no. of errors made by junior doctors in 60 patients was 110 errors in 39 patients (65% of patients), equalling an error rate of 1.8 per patient. 49 (82%) of drug charts written by junior doctors had errors, and 12 (20%) were illegible |

| Kozer et al. (2005) [24] | Prospective observational | Setting: paediatric hospital emergency department Subjects: patients attending on study days (2157 visits); doctors (n = not reported) defined as staff and trainees (interns, residents and fellows) | Wrong dose, wrong route of administration, wrong timing or wrong units | Preprinted order form vs. regular order form | At baseline, 411 orders were written on regular charts. 68 errors were identified from the 411 orders, giving a rate of 16.6%. Post intervention 376 orders on new form contained 37 (9.8%) errors. No actual data are reported on junior doctors, although the paper states there was no statistically significant difference between the rates of error |

| Kozer et al. (2006) [25] | Prospective observational | Setting: tertiary paediatric hospital emergency department (secondary care) Subjects: patients (n = 2157) attending department; doctors (n = 22) in the ED (interns, 1st–4th year residents, fellows) | Wrong dose, wrong route of administration, wrong timing or wrong units | A short educational tutorial aimed at reducing the incidence of prescribing errors among trainees | 976 drug orders were written by junior doctors, but only 899 were included in the study (unable to identify prescriber). Of these 112 errors were identified, giving a rate of 12.5% No difference was seen between error rates of doctors attending (12.7%) and not attending (12.4%) the tutorial |

| Mandal and Fraser (2005) [26] | Prospective observational | Setting: single ophthalmic hospital Subjects: patients (n = not reported) attending either outpatients, A&E, day care or as inpatients; doctors (n = not reported) working within these areas | Errors of prescription writing (incorrect patient details, illegibility, incorrect format, scripts where prescriber could not be identified) or drug-related errors (wrong dose, frequency, route) | None | Junior doctors were responsible for 83 charts with at least one error, which calculates to 4.2% of all charts |

| Taylor et al. (2005) [27] | Retrospective observational | Setting: suburban academic tertiary care children's hospital Emergency Department (secondary care) Subjects: patients (n = not reported) attending department; residents (n = 49) | Major or minor omissions of critical information, wrong dose or directions, unclear quantity, incomplete directions or allergy error (no documentation of known allergy or use of a drug for which an allergy has been reported) | None | 212 (59%) charts out of 358, contained a total of 311 errors per chart. This calculates as 1.47 errors per affected patient |

| Webbe et al. (2007) [28] | Prospective observational | Setting: 800-bed associate teaching hospital with catchment population of 320 000. Subjects: patients (n = not reported) on four wards admitting general medical emergencies; junior doctors on medical wards (n = 13) | Transcription errors; failure to take into account pharmaceutical issues (intravenous drug incompatibilities, drug interactions, contraindications, lack of monitoring of drug or patient parameters); failure to communicate essential information (such as omissions in medication history taking); use of drugs or doses inappropriate for the patient | A clinical teaching pharmacist programme to improve prescribing skills among newly qualified (PRHOs) | Pre-intervention: control group: 31.8% (34/107); intervention group: 20% (39/195). Post intervention: control group: 25.8% (41/159); intervention group: 12.5% (12/96). Average baseline incidence of errors 24.2% |

| Dean et al. (2002) [4] | Prospective observational | Setting: UK hospital (single centre) Subjects: inpatients (n = not reported); doctors (n = 41) in a 550-bed teaching hospital | In accordance with Dean's Delphi study of prescribing errors [32] | None | Total of 88 errors made. Doctor identifiable in only 50. Of these 44 errors were studied, 40 were made by junior doctors (91%) |

| Haw and Stubbs (2003) [29] | Prospective observational | Setting: 400-bed psychiatric tertiary referral centre Subjects: patients (n = not reported) at a psychiatric tertiary referral centre; consultant and junior psychiatrists (n = not reported) at this hospital | In accordance with Dean's Delphi study of prescribing errors [32] | None | Of 311 errors identified in 260 prescribed items, 120 were attributed to junior doctors and 172 to consultants (for 19 errors the prescriber was not identified) |

| Larson et al. (2004) [30] | Retrospective observational | Setting: 360-bed community-based teaching hospital Subjects: patients not specified (n = not reported); surgical house staff (PGY1–5; n = 22) | Orders contraindicated due to allergy, duplicate or incomplete orders, failure to take into account laboratory results or patient weight (where necessary), inappropriate dose, route or frequency, or wrong patient | None | A total of 75 errors were made by 22 surgical residents |

| Galanter et al. (2005) [31] | Retrospective observational | Setting: university hospital (secondary care) Subjects: patients (n = 233) with renal dysfunction; prescribers (n = not reported): medical house staff, nurses, pharmacists, medical students and attending physicians | Alerts were taken as a proxy measure for errors | Introduction of automated Decision Support Alerts on a Computerized Physician Order Entry system | The likelihood of a patient receiving at least one dose of the contraindicated medication decreased from 89% to 47% after alert implementation. Medical house staff made up 70% (n = 226) of clinicians receiving alerts |

Studies reporting errors per item

Lesar [9] quantified prescribing errors made by physicians in a US teaching hospital, to determine associated risk factors and to assess the risk to patients from errors. All orders written were reviewed by centralized staff pharmacists prior to dispensing and potential errors identified in these were then discussed with prescribing staff. Of 289 411 orders, 905 errors were reported (3.13 per 1000 orders). Junior staff made 864 errors (95.5%), giving a calculated error rate of three errors made by junior staff per 1000 items prescribed by all doctors.

Bordun [10] studied prescribing errors in a single paediatric intensive care unit in Australia and evaluated the incidence, type and significance of prescribing errors. The Intensive Care Unit ward pharmacist reviewed every medication order and noted errors, which were then agreed and categorized by a consultant physician. During the study period, 68 of 1518 medication orders were judged to be errors (45 per 1000). Only 53 errors could be traced to the prescriber, of which 46 (87%) were made by junior staff. After adjustment for those errors not accounted for, this gives a calculated error rate of 38 errors made by junior staff per 1000 items prescribed by all doctors.

Ho [11] characterized the number, frequency, origin and outcome of prescribing errors in a Canadian tertiary care teaching hospital. There were 1330 prescribing errors over a 25-week period. Residents were responsible for 479 errors (36%). In the study period, 237 798 items were prescribed, giving an overall rate of five errors per 1000 items. Residents had a reported error rate of two per 1000 items prescribed by all doctors.

Howell [12] studied the effect of an educational intervention for residents in a US family care centre. At baseline, 23 errors were identified in 128 medication orders and 34 out of 172 post intervention. This is reported as 179 per 1000 items written by juniors pre-intervention and 197 per 1000 items written by juniors post intervention.

Bizovi [13] determined whether the introduction of computer-aided prescribing reduced prescribing errors in a US emergency department. Pre-intervention there were 54 errors in 2326 medication items ordered by any doctor (reported as 23 errors per 1000 items) and 32 errors in 1280 items made by residents, which calculates as 25 errors per 1000 items written by juniors. Post intervention, 11 errors in 1594 items were made by any doctor (reported as seven per 1000), and six in 1114 were made by residents (calculated as five errors made by junior staff per 1000 items prescribed by all doctors).

Dean [14] studied the incidence, type and significance of prescribing errors in a UK teaching hospital. In 36 168 orders, there were 538 errors. Of these errors, the prescriber could be identified in 482, of which 472 errors (98%) were made by junior staff (calculated rate is 15 errors per 1000 total items).

Fijn [15] explored an epidemiological framework to assess predictors of prescribing errors in two teaching hospitals in the Netherlands. Data collection included all new prescriptions over a 14-day period. There were 449 errors in 1913 prescription items written by any doctor (assumed as not explicit in paper), giving a rate of 235 errors per 1000 items. Junior doctors were 1.57 times more likely to cause an error than senior staff (calculated as 143 errors made by junior staff per 1000 items prescribed by all doctors).

Anton [16] studied a computerized physician order entry system in a UK renal medicine ward. Alerts generated by the system were used as a proxy measure for potential errors. Data were collected from the computer system for a 2-month period. Of 5995 prescription items ordered, 5136 were made by junior doctors. There were 6592 alerts, of which junior doctors received 5462 warning alerts. Of these warnings, 2820 were ignored, suggesting that 2642 warnings reflected true errors (calculated as 514 errors made by junior staff per 1000 items prescribed by juniors).

Hendey [17] compared the error rates of residents in a community-based teaching hospital in the USA, between on call or post on call junior staff. Errors were logged by the pharmacy department, then a retrospective chart review was undertaken by researchers. There were 177 errors in 8195 medication orders (reported as 22 errors made by junior staff per 1000 items prescribed by juniors).

Stubbs [18] examined the nature, frequency and severity of prescribing errors in nine UK psychiatric hospitals. There were 880 errors in 22 036 items; however, 357 did not meet the inclusion criteria (e.g. errors relating to the whole chart such as missing information, or which did not fit the definition but were off formulary, off license or other errors). Nonconsultant staff made 329 of the 523 errors (63%), calculated as a rate of 15 errors made by junior staff per 1000 items prescribed by all doctors.

Walsh [19] determined the frequency and types of medication errors attributable to a computerized physician order entry system in a US study of a paediatric intensive care unit. There were 104 errors in 6916 medication orders made by residents for 352 admissions, calculated as 15 medication errors per 1000 total items. No breakdown of errors is given, therefore prescribing error data cannot be extracted. However, the paper does report that 71% of the 71 serious errors were at the drug ordering (prescribing) stage.

Studies reporting error per patient or drug chart

Shaughnessy [20] tested whether educational intervention improved the prescription writing skills of residents in a US family medicine centre. Data were collected from residents over three 4-monthly periods by pharmacy staff, pre, during and post intervention; 21% of charts contained an error prior to the intervention and 17% after the intervention.

Shaughnessy [21] also conducted a further study in the same setting, over a longer time frame. At baseline 14.4% of drug charts contained an error, with 6% post intervention.

Kozer [22] studied the incidence and type of prescribing errors in a Canadian paediatric hospital emergency department. Prescribing errors were identified in 154 out of 1532 charts (10.1%), or of 766 charts where medicines were prescribed (20.1%). There were 271 different prescribing errors in the 154 charts, calculated as 1.8 errors per chart. Three hundred and forty-six patients were treated by juniors, but no indication is given of the number of errors in these patients. However, the authors do report that junior doctors were 1.5 times more likely to commit an error than senior doctors, which would calculate as 162 errors of the total 271, written in 154 charts (2.1 errors made by junior staff per 1000 charts written by all doctors).

McFadzean [23] compared the accuracy of drug history and chart writing between 12 junior doctors and four clinical pharmacists in a UK medical admissions unit. Prescribing errors and drug chart errors were defined as separate categories. Prescribing errors were defined as drugs omitted or prescribed in error, errors in dosage or frequency, or known drug allergies not recorded. Drug chart errors were defined as: illegible hand writing, lower case, inappropriate use of trade names, abbreviation of micrograms or units, or omission of date, signature, site for topical preparations, frequency, maximum dose and reason for ‘as required’ medicines. Of the 60 patients seen by the junior doctors, there were prescribing errors identified for 39 patients. Forty-nine patients had drug chart errors identified (82%). There were 110 errors in total. The authors report a rate of 1.8 errors made by juniors per patient chart.

In a further study in a Canadian paediatric hospital emergency department, Kozer [24] tested an intervention to see if a structured drug order sheet reduced the incidence of medication errors. At baseline, 68 errors were identified from the 411 charts, giving a rate of 16.6%. No actual data are reported on junior doctors, although the paper states there was no statistically significant difference between the rates of error committed by junior and senior doctors.

Kozer [25] determined whether a short tutorial on prescribing (based on previous study results) reduced the incidence of prescribing errors by 22 junior doctors, comparing those who did and did not attend (in the same setting as before). As there was no difference in performance, the results are combined here. There were 976 drug charts written by junior doctors. In 899 the prescriber was identifiable, and 112 drug charts containing at least one error were identified, calculated as 12.5% of charts.

Mandal [26] studied the number of prescribing errors, where they occurred most commonly and who was most likely to have committed them made over a 4-week period in a single UK ophthalmic hospital. Of the 1952 drug charts screened, 144 (7%) had an error in prescription writing (defined as incorrect patient details or illegibility). The prescriber could be identified in 126 of the 144 charts with an error. Of the charts where the prescriber could be identified, 68 (54%) were attributable to junior doctors. Of the remaining 1808 charts with no writing error, 15 (1%) contained a drug error (defined as incorrect dose, timing or route of administration); all of which were attributable to junior doctors. Junior doctors were therefore responsible for 83 charts with at least one error, which calculates as 4.2% of all charts.

Taylor [27] determined the frequency, type and severity of prescribing errors in a paediatric emergency department in a US tertiary care teaching hospital. There were 311 errors in 212 charts out of 358 written by juniors, giving a rate of 59% of charts with errors and 1.5 errors per affected patient.

Webbe [28] studied the effect of a pharmacist intervention for 13 preregistration house officers (PRHOs) in a UK teaching hospital on improving prescribing skills. Baseline errors for all PRHOs were 73 errors in 302 charts, giving a rate of 24%.

Studies reporting total errors

Dean [4] defined prescribing errors and determined their incidence and causes using Human Error Theory in a UK hospital. There were 88 potentially serious errors in a 2-month period. In 50 of these the prescriber was identified (46 individuals). Forty-four errors were investigated, with junior doctors responsible for 40 errors (91%).

Haw [29] studied the nature, frequency and severity of prescribing errors in a UK psychiatric hospital over 1 month. During the month long data study period, 311 prescribing errors in 260 prescribed items were identified. The number of prescription items or charts written in that study period are not reported. Instead, the authors report a separate estimate was made of the error rate (2.2% of charts written by all staff). During the study period, junior doctors were noted to make 120 errors and consultants 172 errors from the 311 identified (it appears that 19 errors were made where the prescriber was not identified). No calculations of error rate could be made from this study.

Larson [30] assessed the relative frequency of different types of error made by 22 residents in a surgical training programme in a community-based teaching hospital in the USA. Seventy-five errors were identified over a 2-year period.

Studies reporting percentage of errors by juniors

Galanter [31] evaluated the introduction of an automated Decision Support Alerts in a computerized physician order entry system in a US teaching hospital, focusing on reducing contraindicated drugs in renal insufficiency. Alerts were taken as a proxy measure for errors. A reduction in the likelihood of the patient receiving a dose of a contraindicated medication was demonstrated; medical house staff (junior doctors) were reported to have prescribed 70% of all orders that generated an alert.

Discussion

Twenty-four studies meeting the inclusion criteria were identified and data abstracted. The range of error rates was 2–514 per 1000 items prescribed and 4.2–82% of charts reviewed.

This review reports the wide ranges of error rates seen, which cannot be compared due to differences in methodology and error definitions used. Even within similar methods and definitions, large differences may be seen by, for example, using errors made by juniors of all items or patients, or only errors in patients that junior doctors have treated. Moreover, settings and grades of junior doctors vary across studies, and comparisons with more senior staff are not made consistently.

Without consistent methods, reporting units and error definitions it is hard to draw meaningful conclusions. Coherent arguments can be made in favour of error per prescribed item or per patient/chart written as the ideal outcome. These two pieces of information tell researchers, clinicians and users of the data working towards improving patient safety two different things. First, how common is an error each time a prescription item is ordered, and second, what is the risk to each individual patient. As such, both pieces of data should be collected and reported. Many studies reported only one rate, and methods of calculating that rate were not consistent or always explicit. No study considered rates of error per individual prescriber, or clustering effects. Such data would provide another useful stream of information about the causes of prescribing errors, which would inform future interventions. For example, if all prescribers make similar errors at similar rates, an intervention should be targeted to all prescribers. If, however, most errors are made by a few prescribers, a different approach would be needed. To date, scant literature has been identified that explores the process leading to errors.

Agreement on a standard definition is urgently required, as demonstrated by the wide range of definitions used in the studies we reviewed. Thirty-five separate criteria were noted from studies, which used varying combinations of these. A strong contender for the ‘ideal’ definition is Dean's Delphi derived definition [32], which represents the result of an expert consensus (doctors, pharmacists and nurses). This definition has the benefit of describing both elements of prescription writing and of decision making, but where all elements are a possible danger to patients.

Other possible reasons for variation in the error range should be considered. No effect of a change in error rates with time of study was seen, suggesting that there has been no rationalizing of methodology over time or improvement in prescribing competence. Nor was a geographical effect observed, suggesting neither a consistency of methodology nor of error rates in particular countries. In fact, the review reveals a very widespread problem that does not appear to be affected by different training models, healthcare systems or infrastructure and automation.

This study was limited by the above methodological differences, and the difficulties in obtaining all papers identified by the search. A number of potentially relevant studies were also excluded due to lack of reporting of the grade of prescriber. It is unlikely given the wide range of error rates and the difficulties in comparison that further data would have added to the overall interpretation of this review.

Interventions aimed at improving prescribing and reducing errors are a vital component in improving patient safety. The size of the problem that should be addressed is no clearer following this review. Baseline data should be collected as a priority in order to evaluate potential interventions. Two directions for future research are suggested that will provide the information needed. First, future research in prescribing error rates should be well constructed and generalizable using standard definitions and methodology. A well-conducted study of prescribing errors by junior doctors is urgently needed. Second, further in-depth research into the reasons for errors using Human Error Theory is required, building on the work done by Dean et al.[4]. Although attention should continue to be focused on systems factors, individual factors should not be discounted. Future research should concentrate on providing the theoretical foundations prior to developing and validating actual interventions.

Appendix 1

Example search using MEDLINE database.

Ovid MEDLINE(R) 1950 to July week 3 2007 was searched with the following terms:

(prescribing adj4 error$).tw.

(prescription adj4 error$).tw.

((prescription or prescribing) adj4 mistake$).tw.

(drug adj1 error$).tw.

(medication adj error$).tw.

(adverse adj2 drug$ adj2 event$).tw.

(adverse adj2 drug$ adj2 reaction$).tw.

(medication adj2 adverse adj2 event$).tw.

exp Prescriptions, Drug/

exp Medication Errors/

Patient Care/

exp Physicians/

exp Medical Staff/

exp Hospitals/

exp Primary Health Care/

junior.tw.

doctor$.tw.

medical staff.tw.

1 or 2 or 3

4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10

11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18

20 and 21

19 or 22

limit 23 to (english language and years = ‘1990–2007’)

Appendix 2

Dean's definition of a prescribing error

Prescribing a drug for a patient for whom, as a result of a co-existing clinical condition, that drug is contraindicated

Prescription of a drug to which the patient has a documented clinically significant allergy

Not taking into account a potentially significant drug interaction

Prescribing a drug in a dose that, according to British National Formulary or data sheet recommendations, is inappropriate for the patient's renal function

Prescription of a drug in a dose below that recommended for the patient's clinical condition

Prescribing a drug with a narrow therapeutic index, in a dose predicted to give serum levels significantly above the desired therapeutic range

Writing a prescription for a drug with a narrow therapeutic range in a dose predicted to give serum levels significantly below the desired therapeutic range

Not altering the dose following steady-state serum levels significantly outside the therapeutic range

Continuing a drug in the event of a clinically significant adverse drug reaction

Prescribing two drugs for the same indication when only one of the drugs is necessary

Prescribing a drug for which there is no indication for that patient

Prescribing a drug to be given by intravenous infusion in a diluent that is incompatible with the drug prescribed

Prescribing a drug to be infused via an intravenous peripheral line, in a concentration greater than that recommended for peripheral administration

Failure to communicate essential information

Prescribing a drug, dose or route that is not that intended

Writing illegibly

Writing a drug's name using abbreviations or other nonstandard nomenclature

Writing an ambiguous medication order

Prescribing ‘one tablet’ of a drug that is available in more than one strength of tablet

Omission of the route of administration for a drug that can be given by more than one route

Prescribing a drug to be given by intermittent intravenous infusion, without specifying the duration over which it is to be infused

Omission of the prescriber's signature

On admission to hospital, unintentionally not prescribing a drug that the patient was taking prior to their admission

Continuing a GP's prescribing error when writing a patient's drug chart on admission to hospital

Transcribing a medication order incorrectly when rewriting a patient's drug chart

Writing ‘milligrams’ when ‘micrograms’ was intended

Writing a prescription for discharge medication that unintentionally deviates from the medication prescribed on the inpatient drug chart

On admission to hospital, writing a medication order that unintentionally deviates from the patient's pre-admission prescription

Prescribing a drug in a dose above the maximum dose recommended in the British National Formulary or data sheet

Misspelling a drug name

Prescribing a dose that cannot readily be administered using the dosage forms available

Prescribing a dose regime (dose/frequency) that is not that recommended for the formulation prescribed

Continuing a prescription for a longer duration than necessary

Prescribing a drug that should be given at specific times in relation to meals without specifying this information on the prescription

Unintentionally not prescribing a drug for a clinical condition for which medication is indicated

The criteria in italics may be errors depending on the circumstances.

Competing interests

None to declare.

This study was supported by a grant from NHS Grampian Endowments. The authors thank Pam Royle for undertaking the majority of the database searching.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Patient Safety Agency. Patient safety incident reports in the NHS: National Reporting and Learning System Data Summary. Issue 7. Available at http://www.npsa.nhs.uk/patientsafety/patient-safety-incident-data/quarterly-data-reports (last accessed 19 May 2008.

- 2.Barber N, Rawlins M, Franklin BD. Reducing prescribing error: competence, control, and culture. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12:29–32. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.suppl_1.i29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reason J. Human Error. Cambridge: University of Cambridge; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dean B, Schachter M, Vincent C, Barber N. Causes of prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: a prospective study. Lancet. 2002;359:1373–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08350-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Franklin BD, Vincent C, Schachter M, Barber N. The incidence of prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: an overview of the research methods. Drug Saf. 2005;28:891–900. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200528100-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Available at http://www.sign.ac.uk (last accessed 21 October 2007.

- 7.Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. Available at http://www.phru.nhs.uk/Pages/PHD/resources.htm (last accessed 21 October 2007.

- 8.Effective Public Health Practice Project. Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies 2003 (Effective Practice, Informatics and Quality Improvement) Available at: http://www.myhamilton.ca/NR/rdonylres/6B3670AC-8134-4F76-A64C-9C39DBC0F768/0/QATool.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lesar TS, Briceland LL, Delcoure K, Parmalee JC, Masta-Gornic V, Pohl H. Medication prescribing errors in a teaching hospital. JAMA. 1990;263:2329–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bordun LA, Butt W. Drug errors in intensive care. J Paediatr Child Health. 1992;28:309–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1992.tb02674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ho L, Brown GR, Millin B. Characterization of errors detected during central order review. Can J Hosp Pharm. 1992;45:193–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howell RR, Jones KW. Prescription-writing errors and markers: the value of knowing the diagnosis. Fam Med. 1993;25:104–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bizovi KE, Beckley BE, McDade MC, Adams AL, Lowe RA, Zechnich AD, Hedges JR. The effect of computer-assisted prescription writing on emergency department prescription errors. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:1168–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2002.tb01572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dean B, Schachter M, Vincent C, Barber N. Prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: their incidence and clinical significance. Qual Saf Health Care. 2002;11:340–4. doi: 10.1136/qhc.11.4.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fijn R, van den Bemt PM, Chow M, De Blaey CJ, de Jong-van den Berg LT, Brouwers JR. Hospital prescribing errors: epidemiological assessment of predictors. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;53:326–31. doi: 10.1046/j.0306-5251.2001.bjcp1558.doc.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anton C, Nightingale PG, Adu D, Lipkin G, Ferner RE. Improving prescribing using a rule based prescribing system. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13:186–90. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2003.006882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hendey GW, Barth BE, Soliz T. Overnight and postcall errors in medication orders. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:629–34. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stubbs J, Haw C, Taylor D. Prescription errors in psychiatry – a multi-centre study. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20:553–61. doi: 10.1177/0269881106059808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walsh KE, Adams WG, Bauchner H, Vinci RJ, Chessare JB, Cooper MR, Hebert PM, Schainker EG, Landrigan CP. Medication errors related to computerized order entry for children. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1872–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shaughnessy AF, D'Amico F, Nickel RO. Improving prescription-writing skills in a family practice residency. DICP. 1991;25:17–21. doi: 10.1177/106002809102500103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shaughnessy AF, D'Amico F. Long-term experience with a program to improve prescription-writing skills. Fam Med. 1994;26:168–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kozer E, Scolnik D, Macpherson A, Keays T, Shi K, Luk T, Koren G. Variables associated with medication errors in pediatric emergency medicine. Pediatrics. 2002;110:737–42. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.4.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McFadzean E, Isles C, Moffat J, Norrie J, Stewart D. Is there a role for a prescribing pharmacist in preventing prescribing errors in a medical admission unit? Pharm J. 2003;270:896–9. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kozer E, Scolnik D, Macpherson A, Rauchwerger D, Koren G. Using a preprinted order sheet to reduce prescription errors in a pediatric emergency department: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1299–302. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kozer E, Scolnik D, Macpherson A, Rauchwerger D, Koren G. The effect of a short tutorial on the incidence of prescribing errors in pediatric emergency care. Can J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;13:e285–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mandal K, Fraser SG. The incidence of prescribing errors in an eye hospital. BMC Ophthalmol. 2005;5:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-5-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor BL, Selbst SM, Shah AE. Prescription writing errors in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2005;21:822–7. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000190239.04094.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Webbe D, Dhillon S, Roberts CM. Improving junior doctor prescribing – the positive impact of a pharmacist intervention. Pharm J. 2007;278:136–8. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haw C, Stubbs J. Prescribing errors at a psychiatric hospital. Pharm Pract. 2003;13:64–6. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Larson KA, Wiggins EF, Goldfarb MA. Reducing medication errors in a surgical residency training program. Am Surg. 2004;70:467–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galanter WL, Didomenico RJ, Polikaitis A. A trial of automated decision support alerts for contraindicated medications using computerized physician order entry. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2005;12:269–74. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dean B, Barber N, Schachter M. What is a prescribing error? Qual Health Care. 2000;9:232–7. doi: 10.1136/qhc.9.4.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]