Abstract

Recognizing religiosity and spirituality as related-yet-distinct phenomena, and conceptualizing psychological well-being as a multi-dimensional construct, this study examines whether individuals’ frequency of formal religious participation and spiritual perceptions are independently associated with diverse dimensions of psychological well-being (negative affect, positive affect, purpose in life, positive relations with others, personal growth, self-acceptance, environmental mastery, and autonomy). Data came from 1,564 respondents in the 2005 National Survey of Midlife in the U.S. (MIDUS). Higher levels of spiritual perceptions were independently associated with better psychological well-being across all dimensions, and three of these salutary associations were stronger among women than men. Greater formal religious participation was independently associated only with more purpose in life and (among older adults) personal growth; greater formal religious participation was also associated with less autonomy. Overall, results suggest a different pattern of independent linkages between formal religious participation and spiritual perceptions across diverse dimensions of psychological well-being.

A long-standing critique of empirical studies on the health implications of individuals’ religious and spiritual involvement has centered on their relatively unidimensional approach to conceptualizing and examining religiosity/spirituality (Idler et al. 2003). Many studies have focused on a single aspect of religious/spiritual engagement, such as religious service attendance, without considering the potential simultaneous psychological effects of other aspects, such as religious coping. Furthermore, although studies in this area have focused on several aspects of psychological well-being—including life satisfaction, affect, and feelings of meaning and life purpose (Koenig and Larson 2001)—other types of experiences of psychological well-being that could be derived from religious/spiritual experiences have been relatively under-explored, such as feelings of personal growth and self-acceptance.

This study adopts a systematically multidimensional approach to examining the extent to which two specific aspects of religiosity/spirituality—frequency of religious participation and spiritual perceptions—are independently associated with a diverse set of theoretically-derived dimensions of psychological well-being. We focus on individuals’ frequency of religious participation and spiritual perceptions because in contrast to each other, these aspects of religiosity/spirituality represent more distinguishable dimensions of institutional-religious engagement and individual-spiritual experiences. This study also explores whether associations between formal religious participation, spiritual perceptions, and psychological well-being differ by gender and age.

Religiosity and Spirituality as Related-Yet-Distinct Constructs and Their Potentially Independent Linkages with Better Psychological Well-Being

Integrating across previous theoretical conceptualizations of religiosity and spirituality (e.g., Berry 2005; Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging Working Group 1999; Hill and Pargament, 2003; James 1902 [1912]; Underwood and Teresi 2002), we use the term religiosity to refer to the interpersonal and institutional aspects of religiosity/spirituality that are derived from engaging with a formal religious group’s doctrines, values, traditions, and co-members. By contrast, we use the term spirituality to refer to the psychological experiences of religiosity/spirituality that relate to an individual’s sense of connection with a transcendent; integration of self; and feelings of awe, gratitude, compassion, and forgiveness. To clarify this distinction between religiosity and spirituality, we offer, as an example, an individual reciting a formal prayer in a community service. The religious aspects of this behavior include the fact that the prayer is derived from and recited with a larger social group. The spiritual aspects of this behavior include the sense of transcendence and awe that the individual might feel while praying.

Theorizing on religiosity, spirituality, and individual well-being provide a strong foundation for positing that the more distinguishable aspects of religiosity and spirituality would exhibit independent linkages with better psychological well-being. Regarding religiosity, Emile Durkheim’s (1897 [1951]) theorizing on social integration suggests how religious participation—net of its potential association with individuals’ spirituality—might lead to individuals’ better psychological well-being, such as by protecting individuals from egoism (when an individual is insufficiently connected to broader social groups) and anomie (when an individual is insufficiently constrained by social institutions). Furthermore, scholars’ conceptualization of spirituality as an experience that results from a sense of connection with a transcendent and that involves positive emotions—such as faith, hope, and love—suggest strong linkages between spirituality and better psychological well-being, regardless of individuals’ religious participation (e.g., Underwood & Teresi 2002; Vaillant, 2008).

Few studies have examined the potentially independent associations between more institutional-religious and individual-spiritual aspects of religiosity/spirituality with diverse dimensions of psychological well-being. Two recent exceptions are studies that have used data from the 1998 and 2004 General Social Surveys (GSS; Ellison and Fan, 2008; Maselko and Kubzansky 2006); both studies used multivariate regression analyses to estimate the independent associations linking prayer, religious service attendance, and daily spiritual experiences with several aspects of psychological well-being. Collectively, results from these studies are inconsistent as to whether religious participation and spiritual experiences have independent associations with better psychological well-being. Findings descriptively differ according to the assessment of spiritual experiences used, whether the analyses examined data from men and women together, the particular wave of GSS data used, and the psychological well-being outcome under consideration. For example, using data from the 1998 GSS stratified by gender, Maselko and Kubzansky (2006) reported that weekly religious activity and having a daily spiritual experience (e.g., feeling God’s love directly or through others, feeling inner peace, feeling God’s presence) are independently associated with greater happiness among men, but that only spiritual experience is associated with greater happiness among women. Ellison and Fan (2008), however, using data from the 2004 GSS and analyzing data from men and women together, reported that greater frequency of non-theistic daily spiritual experiences (e.g., finding strength in religion and spirituality, feeing spiritually touched by the beauty of creation, feeling selfless caring for others)—but not religious attendance—is associated with greater happiness for both men and women.

In addition to examining the potentially independent linkages between particular aspects of religiosity/spirituality and psychological well-being by using data from an alternative national survey, the current study aims to build on these studies by conceptualizing experiences of spirituality in a way that does not necessitate any degree of religious engagement. Not only does this study’s focal domain of spirituality exclude references to God (to which Maselko and Kubzanksy’s [2006] index of spiritual experiences made reference), but it further excludes other religious references, including mentions of religion, creation, and blessings (to which Ellison and Fan’s [2008] non-theistic index of spiritual experiences made reference). This approach is consistent with the idea that although some individuals experience spirituality by connecting with a more institutionally or religiously defined set of beliefs, others might experience spirituality by connecting with a more personally defined spiritual force (Fuller 2001). To clarify our study’s focus on a domain of spirituality that does not necessitate any religiosity, in contrast to previous studies’ focus on spiritual experiences (which includes at least some degree of religiosity in its assessment), we refer to our study’s dimension of spirituality as spiritual perceptions.

Differences by Age and Gender in the Associations between Religiosity/Spirituality and Diverse Dimensions of Psychological Well-Being

In addition to scholars noting the importance of studies that examine linkages between particular aspects of religiosity/spirituality and psychological well-being (Idler et al. 2003), scholars also have called for additional studies in this area that explicitly examine subgroup differences in the mental health effects of religious/spiritual engagement (e.g., Pargament 2002). Although studies that have investigated subgroup differences by gender have yielded mixed results (see, for example, Ellison and Fan 2008; Maselko and Kubzanky 2006; Mirola 1999; and Norton et al. 2006), studies consistently indicate that in the U.S., women, on average, report being more religious/spiritual than do men (de Vaus and McAllister 1987). Scholars have posited several reasons as to why religiosity/spirituality might be more salient for women than men. For example, congruent with the idea that social relationships more strongly influence women’s mental health than men’s, some have suggested that women might benefit more from social aspects of religious/spiritual connection—such as congregational sources of social support—than men (e.g., Mirola 1999). Others have focused on role socialization processes. Levin (1994), for example, suggested that women have been socialized to more strongly internalize traits and behaviors—such as cooperation and nurturance—that are more congruent with general religious values, which might make enhanced religiosity/spirituality more important for their psychological well-being.

Regarding an additional potential subgroup difference, studies have found that older adults rate religion as more important in their lives than do younger adults (Beit-Hallahmi and Argyle 1998). Scholars have posited that aspects of both religiosity and spirituality are important resources in helping individuals productively cope with age-related losses (Krause and Tran 1989). Spirituality, for example, might be increasingly beneficial with advancing age as many older adults face the developmental challenges of transcending their physical self (Peck 1968) and coming to better terms with their mortality (Havighurst 1972). Engagement with religious communities might also benefit older adults in particular by providing social relationships and support in later life (Neill and Kahn 1999). Associations between religiosity/spirituality and psychological well-being might also be larger for older adults than younger adults because of a cohort effect, specifically, the tendency for adults born earlier in the 20th century to have been socialized to value religiosity and spirituality more than adults born later in the century (Levin and Taylor 1997).

Linkages between Religiosity/Spirituality and Diverse Dimensions of Psychological Well-Being

Building on theorizing regarding psychological well-being as a multi-dimensional construct (Ryff and Keyes 1995; Keyes, Shmotkin and Ryff 2002), this study investigates linkages between formal religious participation, spiritual perceptions, age, gender, and psychological well-being across several theoretically derived dimensions of well-being. In addition to focusing on positive and negative affect, which have been the primary focus of social research on individuals’ quality of life (Hughes 2006), we also examine other dimensions of psychological well-being that address more engagement-based aspects of well-being. (For a framework regarding differences in scholarly approaches to conceptualizing psychological well-being, refer to Ryan and Deci [2001]). Specifically, we investigate six dimensions of psychological well-being that were identified by integrating across theoretical insights from developmental, clinical, and social psychological theorizing (see Ryff and Keyes 1995, for a discussion), including autonomy (sense of self-determination), environmental mastery (the capacity to manage effectively one's life and surrounding world), personal growth (feelings of continued growth and development as a person), positive relations with others (having quality relations with others), purpose in life (the belief that one's life is purposeful and meaningful), and self-acceptance (positive evaluations of oneself and one's past life). Theoretical attention to the influence of spirituality and religiosity in processes of optimal human development (Maslow 1971) suggests the importance of examining linkages between religiosity and spirituality and these more psychosocial-developmental aspects of psychological well-being.

Findings from previous studies on associations between religiosity/spirituality and multiple dimensions of psychological well-being suggest that different patterns of associations are likely to emerge across diverse dimensions of psychological well-being. For example, Ellison and Fan (2008) found that spiritual experiences were more consistently associated with positive (e.g., excitement with life), as opposed to negative (e.g., psychological distress), aspects of mental health. Furthermore, in one of the few studies that have examined linkages between religiosity/spirituality and all six of Ryff’s (1995) dimensions of psychological well-being, Frazier, Mintz, and Mobley (2005) found that organizational, nonorganizational, and subjective religiosity were associated with all dimensions, except autonomy, among a convenience sample of older African American adults in New York City. These findings suggest the importance of testing associations between religiosity/spirituality and diverse dimensions of psychological well-being.

Hypotheses

Building on previous scholarship on religiosity/spirituality, gender, age, and multiple dimensions of psychological well-being, we formulated the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Higher levels of formal religious participation and spiritual perceptions will have independent associations with adults’ better psychological well-being across a diverse array of dimensions.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Associations between formal religious participation, spiritual perceptions, and better psychological well-being will be stronger for women than men.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Associations between formal religious participation, spiritual perceptions, and better psychological well-being will be stronger for older adults than younger adults.

Method

Data

This study used data from the 2005 National Survey of Midlife in the U.S. (MIDUS). These data were collected as part of a 10-year follow-up study of a U.S. national sample of English-speaking, non-institutionalized adults ages 25 through 74 when first interviewed in 1995. This study did not use data collected in 1995 because measures of key analytic variables—including the spiritual perceptions index—were not included at that time of measurement. The original MIDUS national probability sample was obtained through random digit dialing, with an oversampling of older respondents and men to ensure the desired distribution on the cross-classification of age and gender. In 1995, 3,485 individuals responded to a telephone survey (70% response rate), and in 2005, 1,801 respondents (approximately 55% of the Time 1 respondents who were still alive at Time 2) completed both a telephone survey and self-administered questionnaire.

To account for the fact that non-respondents to the MIDUS tended to have lower levels of education and income and to be from non-majority racial/ethnic groups, as well as the fact that the survey design involved oversampling older adults and men, sampling weights that correct for selection probabilities, non-response, and attrition were created that allow this sample to match the population on these sociodemographic factors in 2005. Multivariate regression analyses were conducted with both the weighted and unweighted data, and results based on the weighted data were similar to those based on the unweighted data. Estimates from analyses with the unweighted data are reported because these analyses provide estimates with more reliable standard errors (Winship and Radbill 1994).

Measures

Table 1 provides a summary description of the measures for the main analytic variables, including: (1) the eight dimensions of psychological well-being (positive affect, negative affect, personal growth, purpose in life, positive relations with others, self-acceptance, environmental mastery, and autonomy), (2) frequency of formal religious participation, and (3) spiritual perceptions. As noted in Table 1, the five items used to assess respondents’ spiritual perceptions were based on Underwood and Teresi’s (2002) 16-item Daily Spiritual Experiences scale. The MIDUS scale eliminated several of the original items’ references to God, religion, creation, and blessings. Bivariate correlations between the spiritual perceptions index and other measures, as well an exploratory factor analysis, provided evidence for the construct validity of this five-item scale.1 Furthermore, the bivariate correlation between spiritual perceptions and formal religious participation scores was r = .34, which supports the idea that these constructs are related yet distinct from each other. (A correlation matrix across all analytic variables is available from the authors upon request.)

Table 1.

Variable definitions and descriptive statistics for main analytic variables

| Variable Name | Summary Description | Mean | S.D. | Range | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | |||||

| Negative Affect (Mroczek and Kolarz 1998) | Six items asked respondents how often during the past 30 days (5 = none of the time; 1 = all of the time) they felt indicators of negative affect, such as “so sad nothing could cheer you up” and “nervous”a,b | −.02 | 1.00 | −.89 – 5.92 | .86 |

| Positive Affect (Mroczek and Kolarz 1998) | Six items asked respondents how often during the past 30 days (5 = none of the time; 1 = all of the time) they felt indicators of positive affect, such as “extremely happy” and “calm and peaceful”a,b | .00 | 1.00 | −3.35 – 2.23 | .89 |

| Personal Growth (Ryff and Keyes 1995) | Seven items asked respondents the degree to which they agree or disagree (1 = strongly agree; 7 = strongly disagree) with statements indicating personal growth, such as “For me, life has been a continuous process of learning, changing, and growth.”a,b | .00 | 1.00 | −3.86 – 1.53 | .76 |

| Purpose in Life (Ryff and Keyes 1995) | Seven items asked respondents the degree to which they agree or disagree (1 = strongly agree; 7 = strongly disagree) with statements indicating purpose in life, such as “I have a sense of direction and purpose in life.”a,b | .00 | 1.00 | −3.50 – 1.56 | .75 |

| Self-Acceptance (Ryff and Keyes 1995) | Seven items asked respondents the degree to which they agree or disagree (1 = strongly agree; 7 = strongly disagree) with statements indicating self-acceptance, such as “I like most aspects of my personality.”a,b | .00 | 1.00 | −3.73 – 1.34 | .85 |

| Positive Relations with Others (Ryff and Keyes 1995) | Seven items asked respondents the degree to which they agree or disagree (1 = strongly agree; 7 = strongly disagree) with statements indicating positive relations with others, such as “Most people see me as loving and affectionate.”a,b | .00 | 1.00 | −3.69 – 1.26 | .78 |

| Environmental Mastery (Ryff and Keyes 1995) | Seven items asked respondents the degree to which they agree or disagree (1 = strongly agree; 7 = strongly disagree) with statements indicating environmental mastery, such as “In general, I feel I am in charge of the situation in which I live.”a,b | .00 | 1.00 | −3.34 – 2.30 | .63 |

| Autonomy (Ryff and Keyes 1995) | Seven items asked respondents the degree to which they agree or disagree (1 = strongly agree; 7 = strongly disagree) with statements indicating autonomy, such as “My decisions are not usually influenced by what everybody else is doing.”a,b | .00 | 1.00 | −3.48 – 1.66 | .73 |

| Explanatory Variables | |||||

| Formal Religious Participation | Average score across two items that asked respondents about the frequency (1 = never; 4 = at least a few times a week) by which they attend “religious or spiritual services” and participate in “church/temple activities (e.g., dinners, volunteer work, and church related organizations)” | 2.23 | .95 | 1.00 – 4.00 | .78 |

| Spiritual Perceptions (Based on Underwood and Teresi’s [2002] Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale) | Five items asked respondents how frequently they experience each of the following on a daily basis (1 = often; 4 = never): “a feeling of deep inner peace or harmony, a feeling of being deeply moved by the beauty of life, a feeling of strong connection to all life, a sense of deep appreciation, and a profound sense of caring for others”a | 3.16 | .63 | 1.00 – 4.00 | .88 |

Note: Data are from the 2005 National Survey of Midlife in the U.S. (MIDUS; N = 1,801).

Scores were reverse coded.

Scores were standardized.

Table 2 displays descriptive statistics for measures of sociodemographic factors and other statistical control variables. In addition to measures for age and gender, these variables included respondents’ race/ethnicity, education, marital status, parental status, religious denomination, and household income. Previous studies have demonstrated that these sociodemographic factors are associated with aspects of religiosity/spirituality (e.g., Levin, Taylor and Chatters 1994; Peacock and Poloma 1999) as well as with psychological well-being (e.g., Ryff 1995). This study also included statistical controls for other individual characteristics—specifically, levels of extraversion, openness to experience, and functional limitations—which previous studies have similarly found to be associated with aspects of religiosity/spirituality, as well as psychological well-being (e.g., Kelley-Moore and Ferraro 2001; Leach and Lark 2004; Mroczek and Kolarz 1998). To assess extraversion and openness to experiences, participants were asked to indicate the extent to which adjectives—such as outgoing and friendly for extraversion and creative and imaginative for openness to experience—described them on a 4-point scale (1 = a lot; 4 = not at all). To assess functional limitations, participants were asked to indicate on the same 4-point scale how much their health limits them when performing tasks, such as lifting or carrying groceries or walking several blocks.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for sociodemographic and other control variables

| Mean | (S.D.) | Range | Cronbach’s Alpha | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Femalea | .55 | .50 | .00 – 1.00 | -- |

| Age | 56.89 | 12.60 | 33.00 – 84.00 | -- |

| Race/Ethnicitya,b | ||||

| White | .85 | .36 | .00 – 1.00 | -- |

| Black | .06 | .23 | .00 – 1.00 | -- |

| Latino | .04 | .19 | .00 – 1.00 | -- |

| Other Race/Ethnicity | .06 | .24 | .00 – 1.00 | -- |

| Respondents’ Educationa | ||||

| < 12 years | .07 | .264 | .00 – 1.00 | -- |

| 12 years | .27 | .45 | .00 – 1.00 | -- |

| 13 – 15 years | .29 | .45 | .00 – 1.00 | -- |

| 16+ years | .37 | .48 | .00 – 1.00 | -- |

| Household Income (in $1,000 units) | 75.09 | 54. 98 | .00–300.00 | -- |

| Marrieda | .67 | .47 | .00 – 1.00 | -- |

| Has a Childa | .87 | .34 | .00 – 1.00 | -- |

| Religious Denominationa, b | ||||

| No Religious Preference | .14 | .35 | .00 – 1.00 | -- |

| Conservative/Moderate Protestant | .34 | .47 | .00 – 1.00 | -- |

| Liberal Protestant | .05 | .22 | .00 – 1.00 | -- |

| Latter-Day Saint | .08 | .27 | .00 – 1.00 | -- |

| Catholic | .23 | .42 | .00 – 1.00 | -- |

| Other Christian | .12 | .33 | .00 – 1.00 | -- |

| Jewish | .02 | .15 | .00 – 1.00 | -- |

| Other Non-Christian/Missing | .03 | .16 | .00 – 1.00 | -- |

| Functional Limitations | 1.83 | .89 | 1.00 – 4.00 | .94 |

| Extraversion | 3.11 | .58 | 1.00 – 4.00 | .77 |

| Openness to Experience | 2.92 | .54 | 1.00 – 4.00 | .65 |

Note: Data are from the 2005 National Survey of Midlife in the U.S. (MIDUS; N = 1,801).

Dichotomous variables are reported as proportions.

Proportions do not sum to 1.00 because of rounding.

Analysis Plan

Multivariate regression models were estimated to test the proposed linkages among the variables. The multivariate models used listwise deletion, which excluded 237 respondents who had any missing data across the main analytic variables, sociodemographic variables, and other covariates.2 To test H1, each of the dependent variables were regressed on the covariates, as well as the measures of formal religious participation and spiritual perceptions. To examine H2 and H3, four interaction terms were added to each of the models, including Female × Formal religious participation, Female × Spiritual perceptions, Age × Formal religious participation and Age × Spiritual perceptions. To interpret statistically significant interaction terms, predicted scores with respect to a given outcome were computed for respondents belonging to relevant subgroups (e.g., men and women whose scores on the spiritual perceptions index were one standard deviation below or above the sample mean). The baseline multivariate model used for these computations included scores for persons at the mean on all continuous variables and zero on all categorical variables.

Because models were estimated across eight related aspects of psychological well-being, we conducted Breusch-Pagan tests to determine the value of estimating models such that error terms were allowed to correlate with each other. Results from these tests indicated that estimating models permitting these correlations fit better with the data than traditional ordinary least squares models that constrained these correlations to be zero. Therefore, we report results from seemingly unrelated regression models (Zellner 1962), which allow for correlated error terms across the models for each psychological well-being outcome.

Results

Linkages between Formal Religious Participation, Spiritual Perceptions, and Diverse Dimensions of Psychological Well-Being

Models 1a, 1b, and 1c in Table 3 and Table 4, as well as Models 1a and 1b in Model 5, display results with respect to H1. Results indicated that reporting more frequent spiritual perceptions was consistently and independently associated with better psychological well-being across all outcomes examined, including lower levels of negative affect (β = −.05, p ≤ .05), as well as higher levels of positive affect (β = .21, p ≤ .001), personal growth (β = .22, p ≤ .001), purpose in life (β = .18, p ≤ .001), positive relations with others (β = .21, p ≤ .001), self-acceptance (β = .24, p ≤ .001), environmental mastery (β = .13, p ≤ .001), and autonomy (β = .07, p ≤ .01).3

Table 3.

Seemingly Unrelated Regression Coefficient Estimates of the Effects of Formal Religious Participation and Spiritual Perceptions on Adults’ Positive Affect, Negative Affect, and Personal Growth

| Positive Affect |

Negative Affect |

Personal Growth |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a | Model 2a | Model 1b | Model 2b | Model 1b | Model 2b | |||||||||||||

| B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | |

| Female | −.09 | (.04) | −.05* | −.54 | (.22) | −.05* | .09 | (.05) | .05* | .62 | (.23) | .05 | .07 | (.04) | .04 | −.24 | (.20) | .04 |

| Age | .02 | (.00) | .21*** | .02 | (.01) | .21*** | −.02 | (.00) | −.26*** | −.03 | (.01) | −.26*** | −.00 | (.00) | −.02 | −.00 | (.01) | −.02 |

| Formal Religious Participation | .00 | (.03) | .00 | .09 | (.12) | −.01 | −.01 | (.03) | −.01 | −.16 | (.12) | −.00 | .04 | (.02) | .04 | −.19 | (.11) | .04 |

| Spirit Perceptions | .33 | (.04) | .21*** | .21 | (.17) | .21*** | −.08 | (.04) | −.05* | −.11 | (.18) | −.05 | .34 | (.04) | .22*** | .43 | (.16) | .22*** |

| Female X Formal Relig Participation | -- | -- | -- | −.02 | (.05) | −.01 | -- | -- | -- | −.08 | (.05) | −.04 | -- | -- | --- | .02 | (.04) | −.01 |

| Female X Spiritual Perceptions | -- | -- | -- | .16 | (.07) | .05* | -- | -- | -- | −.11 | (.07) | −.04 | -- | -- | -- | .12 | (.06) | .04 |

| Age X Formal Relig Participation | -- | -- | -- | −.00 | (.00) | −.02 | -- | -- | -- | .00 | (.00) | .04 | -- | -- | -- | .00 | (.00) | .05* |

| Age X Spiritual Perceptions | -- | -- | -- | .00 | (.00) | .01 | -- | -- | -- | .00 | (.00) | .01 | -- | -- | -- | −.00 | (.00) | −.02 |

| Constant | −3.17 | (.19) | −2.98 | (.54) | 1.84 | (.20) | 2.31 | (.56) | −3.83 | (.17) | −3.56 | (.49) | ||||||

| Valid N | 1564 | 1564 | 1564 | 1564 | 1564 | 1564 | ||||||||||||

Note: Data are from adults who completed both a telephone interview and self-administered questionnaire in the 2005 National Survey of Midlife in the U.S. (MIDUS). All models included as covariates measures of respondents’ race/ethnicity, education, household income, marital status, parental status, religious denomination, functional limitations, extraversion, and openness to experience.

p≤.05

p≤.01

p≤.001 (two tailed).

Table 4.

Seemingly Unrelated Regression Coefficient Estimates of the Effects of Formal Religious Participation and Spiritual Perceptions on Adults’ Purpose in Life, Positive Relations with Others, and Self-Acceptance

| Purpose in Life |

Positive Relations with Others |

Self-Acceptance |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a | Model 2a | Model 1b | Model 2b | Model 1b | Model 2b | |||||||||||||

| B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | |

| Female | −.04 | (.04) | −.02 | −.57 | (.22) | −.02 | .13 | (.04) | .07** | .03 | (.21) | .07** | −.13 | (.04) | −.07** | −.80 | (.21) | −.07** |

| Age | .00 | (.00) | .02 | .00 | (.01) | .02 | .01 | (.00) | .09*** | .00 | (.01) | .08*** | .01 | (.00) | .17*** | .01 | (.01) | .16*** |

| Formal Religious Participation | .06 | (.03) | .06* | −.03 | (.12) | .06* | .02 | (.03) | .02 | −.10 | (.11) | .02 | −.04 | (.03) | −.04 | .01 | (.11) | −.045 |

| Spirit Perceptions | .29 | (.04) | .18*** | .25 | (.17) | .18*** | .33 | (.04) | .21*** | .30 | (.17) | .21*** | .37 | (.04) | .24*** | .25 | (.17) | .24*** |

| Female X Formal Relig Participation | -- | -- | -- | .00 | (.05) | .00 | -- | -- | -- | .01 | (.05) | .00 | -- | -- | -- | .01 | (.05) | .00 |

| Female X Spiritual Perceptions | -- | -- | -- | .17 | (.07) | .05* | -- | -- | -- | .03 | (.07) | .01 | -- | -- | -- | .21 | (.07) | .07** |

| Age X Formal Relig Participation | -- | -- | -- | .00 | (.00) | .02 | -- | -- | -- | .00 | (.00) | .03 | -- | -- | -- | −.00 | (.00) | −.01 |

| Age X Spiritual Perceptions | -- | -- | -- | −.00 | (.00) | −.01 | -- | -- | -- | .00 | (.00) | .00 | -- | -- | -- | .00 | (.00) | .00 |

| Constant | −3.44 | (.19) | −3.11 | (.53) | −4.34 | (.18) | −3.98 | (.21) | −4.12 | (.19) | −3.83 | (.53) | ||||||

| Valid N | 1564 | 1564 | 1564 | 1564 | 1564 | 15645 | ||||||||||||

Note: Data are from adults who completed both a telephone interview and self-administered questionnaire in the 2005 National Survey of Midlife in the U.S. (MIDUS). All models included as covariates measures of respondents’ race/ethnicity, education, household income, marital status, parental status, religious denomination, functional limitations, extraversion, and openness to experience.

p≤.05

p≤.01

p≤.001 (two tailed).

By contrast, although more frequent formal religious participation was associated with higher levels of purpose in life (β = .06, p ≤ .05), frequency of formal religious participation was not independently associated with levels of positive affect (β = .00, n.s.), negative affect (β = −.01, n.s.), personal growth (β = .04, n.s., but note age interaction below), positive relations with others (β = .02, n.s.), self-acceptance (β = −.04, n.s.), or environmental mastery (β = −.05, n.s.). Furthermore, more frequent formal religious participation was associated with lower levels of autonomy (β = −.05, p ≤ .05).

Recognizing that individuals’ spiritual perceptions are oftentimes likely to be derived through formal engagement in religious communities, we conducted post-hoc analyses to examine the possibility that formal religious participation promotes individuals’ psychological well-being through enhancing their spiritual perceptions. Findings from supplementary mediation analyses (not shown) support this interpretation with respect to positive affect, positive relations with others, and, among younger adults (i.e., respondents whose age was at or below the sample mean; see age interaction below), personal growth. When formal religious participation was entered into models that did not include the measure of spiritual perceptions, formal religious participation was associated with higher levels of positive affect (β = .06, p ≤ .05), positive relations with others (β = .07, p ≤ .001), and, among younger adults, personal growth (β = .07, p ≤ .05). These supplementary models, in conjunction with the primary results of this study, suggest that more frequent spiritual perceptions mediates the association between more frequent formal religious participation and these three aspects of psychological well-being. We also conducted moderation analyses to investigate the extent to which having more frequent spiritual perceptions enhances the associations between more frequent formal religious participation and psychological well-being and vice-versa. Results did not provide evidence in support of multiplicative effects.

Gender and Age Differences in the Associations between Spiritual Perceptions, Formal Religious Participation, and Psychological Well-Being

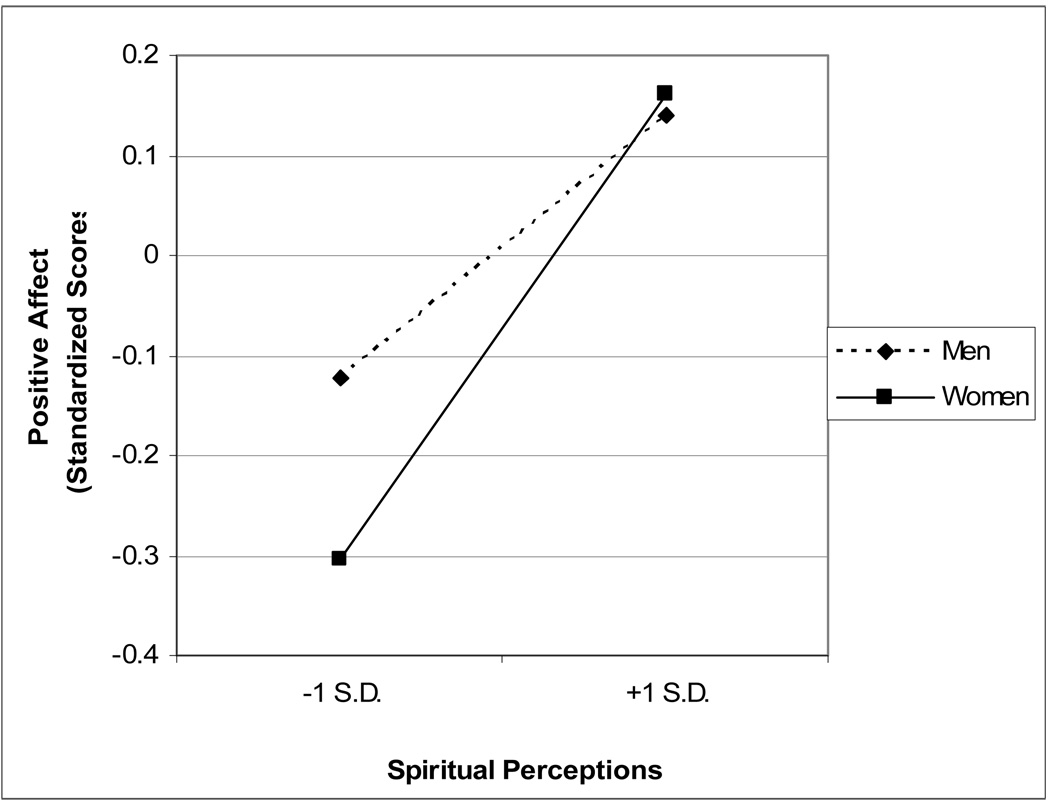

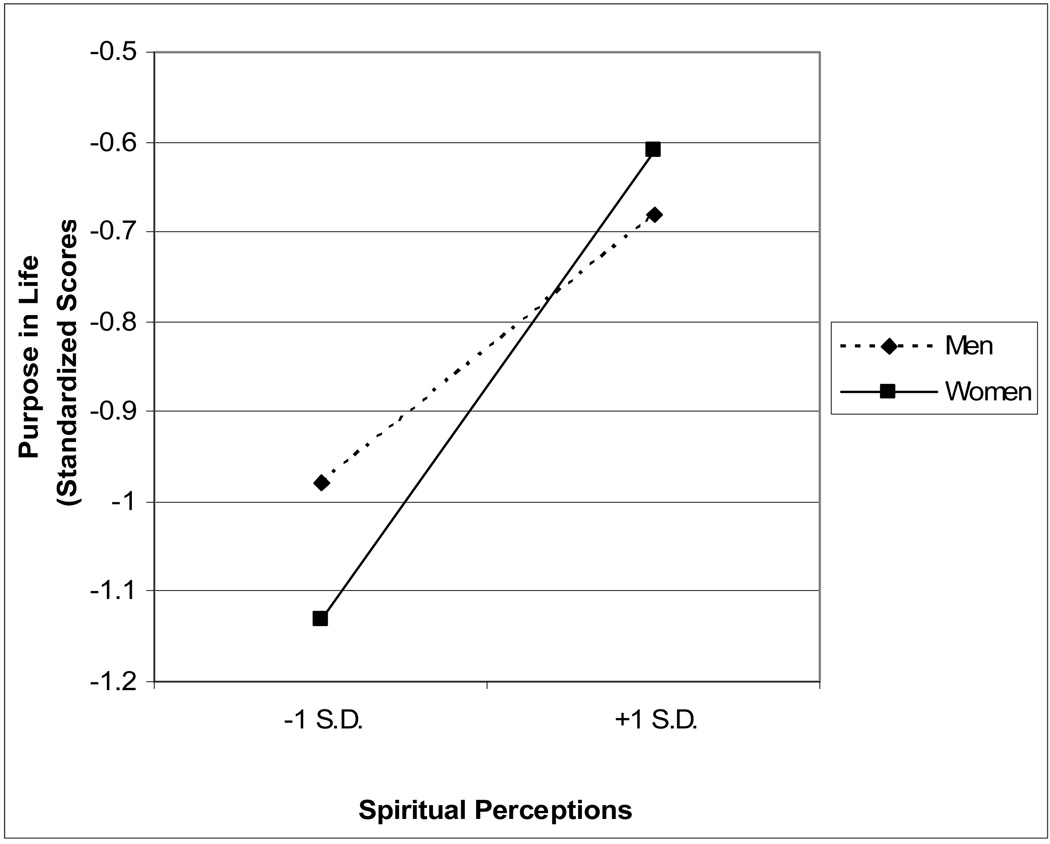

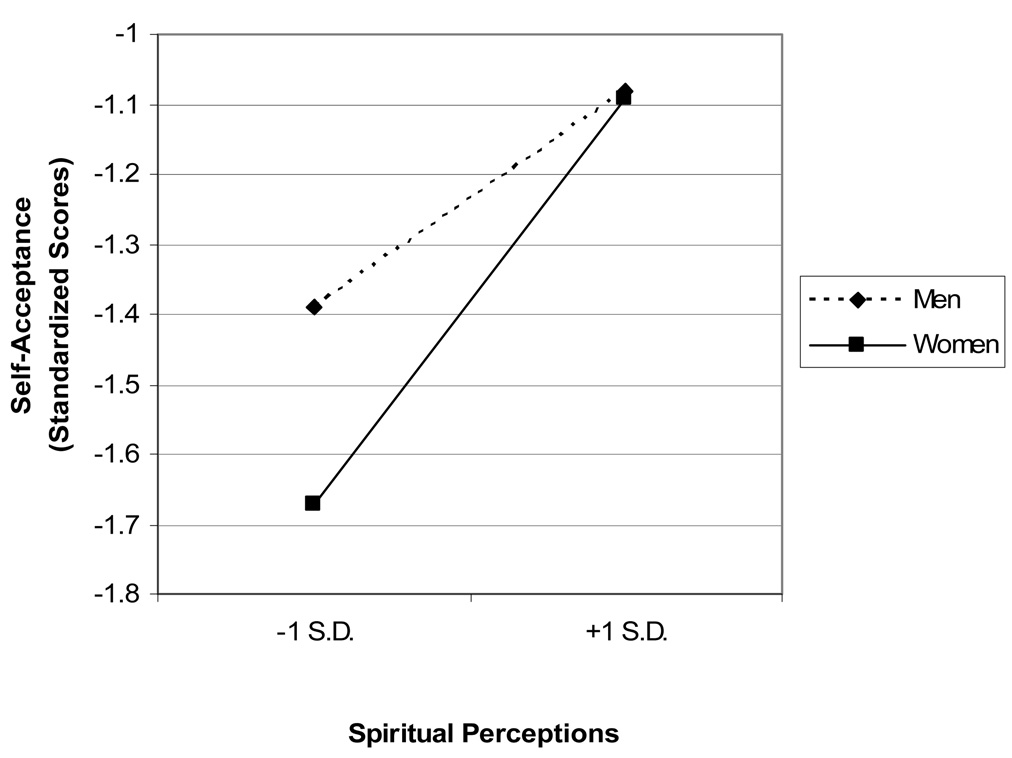

To test H2 and H3, interaction variables were added to each of the previously estimated models (Models 2a, 2b, and 2c in Table 3 and Table 4, as well as Models 2a and 2b in Table 5). Statistically significant interactions of Female × Spiritual perceptions were found in models estimated for positive affect, purpose in life, and self-acceptance (β = .05, p ≤ .05; β = .05, p ≤ .05; β = .07, p ≤ .001, respectively). As Figure 1, Figure 2, and Figure 3 demonstrate, among both men and women, respondents who scored one standard deviation above the mean on spiritual perceptions reported higher levels of positive affect, purpose in life, and self-acceptance than respondents who scored one standard deviation below. However, the difference in level of positive affect among respondents who scored one standard deviation above the mean on spiritual perceptions (in contrast to respondents who scored one standard deviation below) was 43% larger among women than men. Similarly, the difference in levels of purpose in life was 42% larger among women than men, and the difference in levels of self-acceptance was 47% larger among women than men.

Table 5.

Seemingly Unrelated Regression Coefficient Estimates for the Effects of Formal Religious Participation and Spiritual Perceptions on Adults’ Environmental Mastery and Autonomy

| Environmental Mastery |

Autonomy |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a | Model 2a | Model 1b | Model 2b | |||||||||

| B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | |

| Female | −.21 | (.05) | −.11*** | −.67 | (.23) | −.10*** | −.36 | (.05) | −.18*** | −.49 | (.23) | −.18*** |

| Age | .02 | (.00) | .24*** | .03 | (.01) | .24*** | .01 | (.00) | .12*** | .00 | (.01) | .13*** |

| Formal Religious Participation | −.05 | (.03) | −.05 | .01 | (.13) | −.05 | −.06 | (.03) | −.05* | .12 | (.12) | −.06* |

| Spirit Perceptions | .20 | (.04) | .13*** | .32 | (.19) | .12*** | .12 | (.04) | .07** | −.12 | (.19) | .08** |

| Female X Formal Relig Participation | -- | -- | -- | .07 | (.05) | .03 | -- | -- | -- | −.03 | (.05) | −.01 |

| Female X Spiritual Perceptions | -- | -- | -- | .10 | (.08) | .03 | -- | -- | -- | .06 | (.08) | .02 |

| Age X Formal Relig Participation | -- | -- | -- | −.00 | (.00) | −.02 | -- | -- | -- | −.00 | (.00) | −.03 |

| Age X Spiritual Perceptions | -- | -- | -- | −.00 | (.00) | −.03 | -- | -- | -- | .00 | (.00) | .03 |

| Constant | −2.79 | (.20) | −3.33 | (.58) | −2.91 | (.20) | −2.56 | (.58) | ||||

| Valid N | 1564 | 1564 | 1564 | 1564 | ||||||||

Note: Data are from adults who completed both a telephone interview and self-administered questionnaire in the 2005 National Survey of Midlife in the U.S. (MIDUS). All models included as covariates measures of respondents’ race/ethnicity, education, household income, marital status, parental status, religious denomination, functional limitations, extraversion, and openness to experience.

p≤.05

p≤.01

p≤.001 (two tailed).

Figure 1.

Predicted scores of positive affect for men and women who report spiritual perceptions at levels one standard deviation (S.D.) below or above the sample mean

Source: 2005 National Survey of Midlife in the U.S. (MIDUS).

Figure 2.

Predicted scores of purpose in life for men and women who report spiritual perceptions at levels one standard deviation (S.D.) below or above the sample mean

Source: 2005 National Survey of Midlife in the U.S. (MIDUS).

Figure 3.

Predicted scores of self-acceptance for men and women who report spiritual perceptions at levels one standard deviation (S.D.) below or above the sample mean

Source: 2005 National Survey of Midlife in the U.S. (MIDUS).

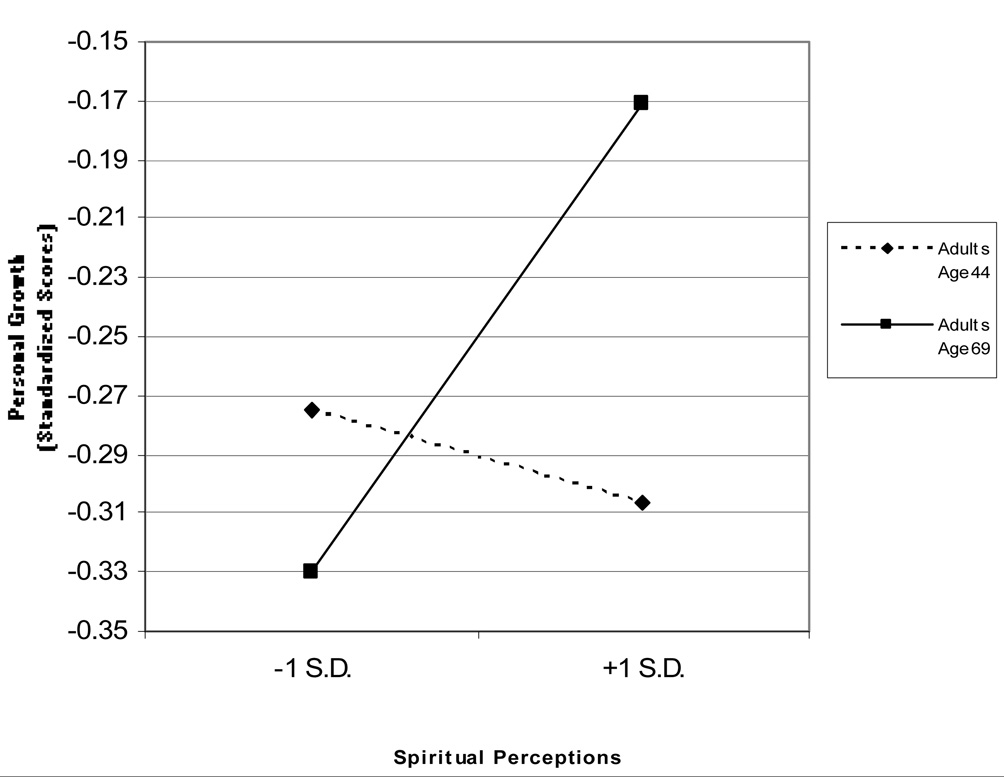

Regarding interactions by age, the Age × Formal religious participation variable in the model for personal growth achieved statistical significance (β = .05, p ≤ .05). As Figure 3 demonstrates, for adults whose age was one standard deviation below the sample mean (age 44), levels of personal growth were relatively comparable among respondents who scored one standard deviation above, or below, the mean on formal religious participation. Among adults whose age was one standard deviation above the sample mean (age 69), however, respondents who reported higher levels of formal participation demonstrated levels of personal growth almost one-fifth of a standard deviation greater than respondents who reported lower levels of formal religious participation.

Discussion

This study contributes to an emerging literature on the extent to which different aspects of religiosity and spirituality are independently associated with various dimensions of individuals’ psychological well-being. Overall, results suggest that institutional religious activity, as indicated by the frequency of individuals’ formal religious participation, and individual spiritual activity, as indicated by the frequency of individuals’ spiritual perceptions, are independently associated with diverse dimensions of psychological well-being to different degrees. Notably, results indicated that higher levels of spiritual perceptions were associated with better levels of psychological well-being across all eight dimensions investigated, whereas associations between more frequent formal religious participation and psychological well-being were largely contingent upon the dimension of psychological well-being under examination.

Although results suggest the primacy of spiritual perceptions over formal religious participation in promoting diverse aspects of individuals’ psychological well-being, results of this study are not to be interpreted so as to minimize the potential psychological benefits of formal religious participation. First, formal religious participation was independently and beneficially linked with two of the psychological well-being outcomes—purpose in life and (among older adults) personal growth. These findings suggest that in terms of these two dimensions of psychological well-being, formal religious participation and spiritual perceptions exhibit independently important associations with better psychological well-being. Furthermore, although more formal religious participation was associated with lower levels of psychological well-being specifically with respect to autonomy, experiencing a lesser sense of self-determination might not be psychologically maladaptive for many religiously engaged individuals; these individuals might derive comfort from perhaps having a sense of divine influence on their lives or experience well-being from sensing interdependence with others. Also, post-hoc analyses regarding spiritual perceptions as an explanatory factor for associations between more frequent formal religious participation and better psychological well-being provided evidence for spiritual perceptions as a mediator for higher levels of positive affect, positive relations with others, and, for younger adults, personal growth. In this way, formal religious participation and spiritual perceptions likely contribute to a single path toward some aspects of better psychological well-being, rather than indicating two independent paths.

Results from this study also further the understanding of patterns of associations between religiosity/spirituality and psychological well-being across diverse dimensions of psychological well-being. Similar to the results of previous studies (Ellison and Fan, 2008; Maselko and Kubzansky 2006), findings from the current study indicate that linkages between spiritual perceptions and several aspects of positive mental health—such as positive affect and positive relations with others—were larger than linkages between spiritual perceptions and indicators of negative mental health—namely, negative affect. Still, the sizes of the associations between spiritual perceptions and psychological well-being varied even among positive indicators of psychological well-being. For example, the association between spiritual perceptions and autonomy was about one-third of the size of the association between spiritual perceptions and positive affect, purpose in life, positive relations with others, and self-acceptance. These findings collectively suggest that spiritual perceptions are likely to promote some aspects of psychological well-being more strongly than others.

In addition to providing evidence that linkages among spiritual perceptions, formal religious participation, and psychological well-being vary across different dimensions of psychological well-being, this study also provides limited, but suggestive, evidence that linkages differ by sociodemographic subgroups. Although analyses detected only one age difference in the association between religious participation and personal growth, gender differences emerged across associations between spiritual perceptions and three aspects of psychological well-being—positive affect, purpose in life, and self-acceptance. More exploratory work on the ways in which men and women, as well as older and younger adults, experience spiritual perceptions and formal religious participation would help to further elucidate the processes through which sociodemographic differences emerged for these specific aspects of psychological well-being.

Although our study demonstrates notable strengths, important limitations remain. First, this study’s cross-sectional design makes causal conclusions tenuous. Given the dearth of longitudinal studies on spiritual perceptions specifically, the extent to which spiritual perceptions cause better psychological well-being or are caused by better psychological well-being remains uncertain. Similarly, few longitudinal studies on linkages between formal religious participation and psychological well-being have considered diverse dimensions of psychological well-being. It seems particularly likely that for some aspects of well-being, processes of reverse causation may well be operative. For example, the finding that more frequent religious participation is associated with less autonomy might reflect the fact that people with lesser feelings of self-determination might be more motivated to attend religious services.

Second, while this study examines subgroup differences in the associations among formal religious participation, spiritual perceptions, and psychological well-being in terms of gender and age, this study does not address other potentially important subgroup differences, such as differences by education and denominational affiliation. Furthermore, this study does not investigate how associations between spiritual perceptions, formal religious participation, and psychological well-being might differ across even more specific subgroups of respondents, such as between men and women with different levels of education or income.

Third, while the multi-item index assessing spiritual perceptions provides a measure of spirituality that closely fits with this study’s theoretical treatment of spirituality, this index does not distinguish between highly spiritual individuals who have arrived at their spirituality through possibly very different means. For example, the current measure of spirituality does not allow for identifying individuals whose spiritual perceptions have been derived from experiencing a close relationship with a religiously defined deity versus individuals whose spiritual perceptions have been rooted in a more secular sense of transcendence or unselfish love. Additional studies are necessary to determine whether divergent sources of spirituality have differential implications for psychological well-being (see Ellison and Fan 2008, for an example), as well as to examine other subdimensions of both religiosity and spirituality, such as individuals’ frequency of private prayer and strength of identification with one’s denominational affiliation.

Fourth, although this study’s measure of spiritual perceptions, which purposively excludes reference to individuals’ religious engagement, offers the advantage of capturing a wide range of spirituality, the use of this adapted measure makes it difficult to compare this study’s results to others that have used measures of spirituality with religious references, such as the more widely used Daily Spiritual Experiences scale (Underwood and Teresi 2002). Also, this study uses a self-report instrument to assess formal religious participation that asked respondents about the “usual” frequency of their participation; using alternative question wordings or methods other than self-report might yield different results regarding linkages between formal religious participation and psychological well-being. Finally, another limitation of this study is its use of data from a 10-year follow-up survey. This use of later-wave data from a longitudinal study raises concerns over biased estimates of population parameters because of attrition and compounded nonresponse across waves of data collection (Acock 2005).

Despite these limitations, results of this study suggest that formal religious participation and spiritual perceptions have independent linkages with psychological well-being to different degrees; in contrast to formal religious participation, spiritual perceptions demonstrated more robust independent associations with better psychological well-being. By drawing on theoretically-derived conceptualizations of religiosity, spirituality, and psychological well-being, this study helps contribute to a “new generation of studies” (Maselko and Kubzansky 2006, p. 2848) aimed at providing a more nuanced understanding of the religious and spiritual contexts for optimal adult psychological health.

Figure 4.

Predicted scores of personal growth for adults ages 44 and 69 who report formal religious participation at levels one standard deviation (S.D.) below or above the sample mean

Source: 2005 National Survey of Midlife in the U.S. (MIDUS).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the John Templeton Foundation (11286) and the National Institute on Aging (AG206983; AG20166).

Footnotes

To examine whether the spirituality scale assesses another component of well-being and not spirituality per se, we conducted an exploratory factor analyses that included scores on the five items of the spiritual perceptions scale and each set of items comprising one of the eight psychological well-being scales. We used an oblique rotation method that allowed the factors to correlate and specified the analyses to estimate two factors (which is consistent with theorizing that scores on each of the psychological well-being scales and the spiritual perceptions index should load onto two correlated factors). Across analyses for all outcomes, the spiritual perceptions items clearly loaded onto one factor and the well-being items loaded onto the other. These analyses provide additional evidence that scores on the spiritual perceptions scale assess something relatively distinct from the psychological well-being scales.

To provide further evidence for the validity of the spiritual perception scale, we also estimated the bivariate correlation between scores on the 5-item spiritual perceptions scale and a single item that asked respondents to rate on a 4-point scale how spiritual they are. This correlation (r = .46) was larger than the correlation between scores on the spiritual perceptions scale and a single item that asked respondents to rate how religious they are (r = .32). Also, the correlation between the single item regarding self-assessed religiosity and formal religious participation (r = .52) was much larger than that between scores on the self-assessed religiosity item and the spiritual perceptions index (r = .29).

Missing data on any one of the variables did not exceed 4.5%. Having missing data on either or both of the explanatory variables was not associated with scores on any of the eight psychological well-being variables.

The spiritual perceptions item regarding “deep inner peace or harmony” paralleled the positive affect item regarding feeling “calm and peaceful.” Also, the spiritual perceptions item regarding “profound sense of caring for others” was conceptually similar to several items on the positive relations with others scale. To ensure that results from models for positive affect and positive relations with others were not entirely a function of conceptual overlap among these items, we estimated models for positive affect and positive relations with the potentially overlapping spiritual perceptions item removed. Results based on the reduced set of spiritual perceptions items were similar to results based on the full set of spiritual perceptions items; to maintain analytic consistency across outcomes, we report results based on the full set of spiritual perceptions items in all models.

Contributor Information

Emily A. Greenfield, School of Social Work and Institute for Health, Health Care Policy, and Aging Research Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey.

George E. Vaillant, Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School

Nadine F. Marks, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison

REFERENCES

- Acock Alan C. Working with Missing Values. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:1012–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Beit-Hallahmi Benjamin, Argyle Michael. Religious Behavior, Belief, and Experience. New York: Routledge; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Berry Devon. Methodological Pitfalls in the Study of spirituality. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2005;27:628–647. doi: 10.1177/0193945905275519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vaus David, McAllister Ian. Gender Differences in Religion: A Test of the Structural Location Theory. American Sociological Review. 1987;52:472–481. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim Emile. In: The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life: A Study in Religious Sociology. Swain JW, translator. New York: The Free Press; 1912 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison Christopher G, Fan Daisy. Daily Spiritual Experiences and Psychological Well-Being Among U.S. Adults. Social Indicators Research. 2008;88:247–271. [Google Scholar]

- Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging Working Group. Multidimensional Measurement of Religiousness, Spirituality for Use in Health Research: A Report of a National Working Group. Kalamazoo, MI: Fetzer Institute; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier Charlotte, Mintz Laurie B, Mobley Michael. Multidimensional Look at Religious Involvement and Psychological Well-Being among Urban Elderly African Americans. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2005;52:583–590. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller RC. Spiritual, but Not Religious: Understanding Unchurched America. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Havighurst Robert J. Developmental Tasks and Education. New York: David McKay Company; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Hill Peter C, Pargament Kenneth I. Advances in the Conception and Measurement of Religion and Spirituality: Implications for Physical and Mental Health Research. American Psychologist. 2003;58:64–74. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes Michael. Affect, Meaning, and Quality of Life. Social Forces. 2006;85:611–629. [Google Scholar]

- Idler Ellen L, Musick Marc A, Ellison Christopher G, George Linda K, Krause Neal, Ory Marcia G, Pargament Kenneth I, Powell Lynda H, Underwood Lynn G, Williams David R. Measuring Multiple Dimensions of Religion and Spirituality for Health Research. Research on Aging. 2003;25:327–365. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley-Moore Jessica A, Ferraro Kenneth F. Functional Limitations and Religious Service Attendance in Later Life: Barrier and/or Benefit Mechanism? The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2001;56:S365–S373. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.6.s365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes Corey L, Shmotkin Dov, Ryff Carol D. Optimizing Well-Being: The Empirical Encounter of Two Traditions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82:1007–1022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig Harold G, Larson David B. Religion and mental health: evidence for an association. International Review of Psychiatry. 2001;13:67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Krause Neal, Van Tran Thanh. Stress and religious involvement among older blacks. Jounal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1989;44:S4–S13. doi: 10.1093/geronj/44.1.s4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach Mark M, Lark Russell. Does spirituality add to personality in the study of trait forgiveness? Personality and Individual Differences. 2004;37:147–156. [Google Scholar]

- Levin Jeffrey S. Religion in aging and health. Theoretical Foundations and Methodological Frontiers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Levin Jeffrey S, Taylor Robert Joseph. Age Differences in Patterns and Correlates of the Frequency of Prayer. The Gerontologist. 1997;37:75–89. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin Jeffrey S, Taylor Robert Joseph, Chatters LM. Race and Gender Differences in Religiosity among Older Adults: Findings from Four National Surveys. Journal of Gerontology. 1994;49:S137–S145. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.3.s137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maselko Joanna, Kubzansky Laura D. Gender Differences in Religious Practices, Spiritual perceptions and Health: Results from the General Social Survey. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;62:2848–2860. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslow Abraham H. The Farther Reaches of Human Nature. New York: Viking Press; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Mirola William A. A Refuge for Some: Gender Differences in the Relationship between Religious Involvement and Depression. Sociology of Religion. 1999;60:419–437. [Google Scholar]

- Mroczek Dan K, Kolarz Christian M. The Effect of Age on Positive and Negative Affect: A Developmental Perspective on Happiness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:1333–1349. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.5.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neill Christina M, Kahn Arnold S. The Role of Personal Spirituality and Religious Social Activity on the Life Satisfaction of Older Widowed Women. Sex Roles. 1999;40:319–329. [Google Scholar]

- Norton Maria C, Skoog Ingmar, Franklin Lynn M, Corcoran Christopher, Tschanz JoAnn T, Zandi Peter P, Breitner John CS, Welsh-Bohmer Kathleen A, Steffens David C. Gender Differences in the Association between Religious Involvement and Depression: The Cache County (Utah) Study. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2006;61:P129–P136. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.3.p129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament Kenneth I. The Bitter and the Sweet: An Evaluation of the Costs and Benefits of Religiousness. Psychological Inquiry. 2002;13:168–181. [Google Scholar]

- Peck Robert. Psychological Developments in the Second Half of Life. In: Neugarten BL, editor. Middle Age and Aging. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1968. pp. 88–92. [Google Scholar]

- Peacock James R, Poloma Margaret M. Religiosity and Life Satisfaction Across the Life Course. Social Indicators Research. 1999;48:321–349. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan Richard M, Deci Edward L. On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52:141–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff Carol D. Psychological Well-Being in Adult Life. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1995;4:99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff Carol D, Keyes Corey LM. The Structure of Psychological Well-Being Revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:719–727. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.4.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawatzky Rick, Ratner Pamela A, Chiu Lyren. A Meta-Analysis of the Relationship between Spirituality and Quality of Life. Social Indicators Research. 2005;72:153–188. [Google Scholar]

- Smith Timothy B, McCullough Michael E, Poll Justin. Religiousness and Depression: Evidence for a Main Effect and the Moderating Influence of Stressful Life Events. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:614–634. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.4.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood Lynn G, Teresi Jeanne A. The Daily Spiritual Experience Scale: Development, Theoretical Description, Reliability, Exploratory Factor Analysis, and Preliminary Construct Validity Using Health-Related Data. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2002;24:22–33. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2401_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillant George E. Spiritual Evolution: A Scientific Defense of Faith. New York: Doubleday Broadway; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Winship Christopher, Radbill Larry. Sampling weights and regression-analysis. Sociological Methods and Research. 1994;23:230–257. [Google Scholar]

- Zellner Arnold. An Efficient Method of Estimating Seemingly Unrelated Regressions and Tests for Aggregation Bias. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1962;57:348–368. [Google Scholar]