Abstract

Immune correlates of vaccine protection from HIV-1 infection would provide important milestones to guide HIV-1 vaccine development. In a proof of concept study using mucosal priming and systemic boosting, the titer of neutralizing antibodies in sera were found to correlate with protection of mucosally exposed rhesus macaques from SHIV infection. Mucosal priming consisted of two sequential immunizations at 12-week intervals with replicating host range mutants of adenovirus type 5 (Ad5hr) expressing the HIV-189.6p env gene. Following boosting with either heterologous recombinant protein or alphavirus replicons at 12-week intervals animals were intrarectally exposed to infectious doses of the CCR5 tropic SHIVSF162p4. Heterologous mucosal prime systemic boost immunization elicited neutralizing antibodies (Nabs), antibody dependent cytotoxicity (ADCC), and specific patterns of antibody binding to envelope peptides. Vaccine induced protection did not correlate with the type of boost nor T-cell responses, but rather with the Nab titer prior to exposure.

Keywords: HIV vaccine, animal model, mucosal challenge, Nabs, ADCC

Introduction

The development of a prophylactic HIV-1 vaccine appears to be the most effective means to combat the continued transmission of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections estimated to be around 7.000 newly infected individuals per day world wide (http://www.unaids.org). Infection of rhesus macaques via the mucosal route with either SIV or SHIV has been used extensively to model mucosal transmission of HIV in humans. The development of vaccine strategies which induce neutralizing antibodies is a particularly daunting challenge, given the primarily mucosal route of transmission and the remarkable diversity of HIV-1 variants (Burton et al., 2004). A limited number of HIV/SIV vaccine strategies have revealed the potential to generate immune responses sufficient to protect against infection/disease progression (Amara et al., 2001; Bertley et al., 2004; Crotty et al., 2001; Doria-Rose et al., 2003; Mossman et al., 2004; Negri et al., 2004; Patterson et al., 2003; Polacino et al., 1999; Zhao et al., 2003). Despite the recent failure of a single modality T-cell based Ad5-vector vaccine strategy to prevent infection and control virus loads in phase 2b trials (Shiver et al., 2002) (http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v449/n7161/full/449390c.html), alternative Adenovirus based prime-boost vaccine strategies for inducing neutralizing antibodies remain viable vaccine candidates. The use of replication-competent Ad4-, 5-, and 7-HIVenv recombinants to prime immune responses followed by protein booster immunizations has successfully protected chimpanzees from homologous and heterologous HIV-1 challenges (Gomez-Roman et al., 2006b; Lubeck et al., 1997; Peng et al., 2005; Robert-Guroff et al., 1998; Zolla-Pazner et al., 1998). In the rhesus model, these combinations were successful as well resulting in reduced viral loads following mucosal SIV challenge (Buge et al., 1997; Patterson et al., 2004; Zhao et al., 2003).

Other vaccine vectors capable of inducing humoral as well as cellular immune responses to HIV-1 or SIVmac include alphavirus replicon particle vaccines derived from Venezuelan equine encephalitis (VEE) virus, Sindbis (SIN) virus, or Semliki virus (Caley et al., 1997; Charles et al., 1997; Davis, Brown, and Johnston, 1996; Davis et al., 2000; Johnston et al., 2005; Mossman et al., 1996; Perri et al., 2003). Each of these vector systems offers distinct advantages based on their unique biological properties. Chimeric alphavirus replicon particles derived from both SIN and VEE have been engineered with the goal of combining optimal potency and safety (Perri et al., 2003). These chimeras combined with recombinant Env protein booster immunizations elicited potent immune responses in non-human primates (Quinnan et al., 2005; Xu et al., 2006). However, no clear immune correlates of protection were observed.

Here we report on a “proof of concept” study incorporating mucosal priming with Ad5hr-HIV-189.6P Env, and at 12 week intervals boosting with either recombinant gp140 HIV-1SF162 Env protein, or VEE/SIN chimeric alphavirus replicon particles expressing ΔV2gp140 HIV-1SF162 Env. The induction of Nabs and their contribution to protection of Indian rhesus macaques from intrarectal (IR) challenge with R5-tropic SHIVSF162p4 revealed protection from infection in five of eight vaccinees.

Results

Pre-challenge Immune responses

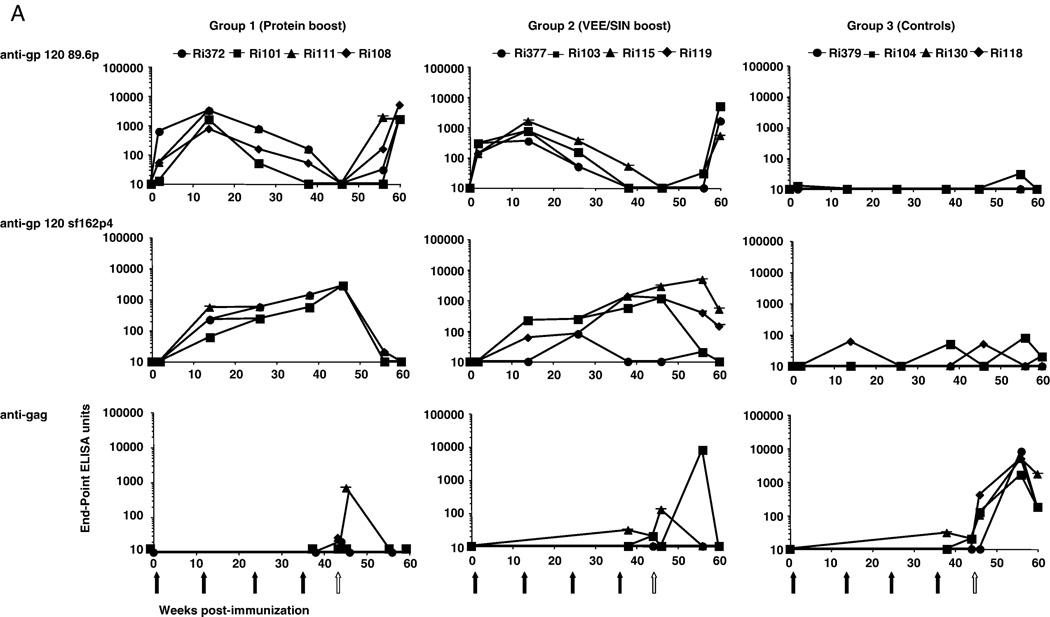

Binding Ab titers to a peptide pool (pp) spanning the entire gp120 of HIV-189.6P were found after both Ad immunizations (Fig. 1A). To a limited extent these Abs could also bind to gp120 peptides of SHIVSF162P4 (Fig. 1A). Booster immunizations with recombinant HIVSF162 gp140 or recombinant VEE/SIN replicons, induced SHIVSF162P4-specific Abs, which increased in both groups after a second booster immunization (Fig. 1A). To determine the epitopes to which the Abs bind, individual peptide binding was studied by pepscan analysis from sera taken at the day of challenge (Langedijk et al., 1997; Slootstra et al., 1996). The reactivity of sera from group 1 to overlapping 15-mer peptides of HIV-1SF162 revealed that Abs were induced that bound to V1 (position 51–55 corresponding to β1–α1 region), V2 (position 60–70, corresponding to the N-terminal part and/or to the center of the V2 loop) and V3 region (the tip of the loop and N-terminal to the tip, position 130–140) (Fig. 1B). Analysis of sera from group 2 showed that all animals lack Abs towards the V2 region as expected since they were boosted with a V2 deleted antigen while two animals showed reactivity to V1 and V3 region. Serum Ri377 showed an unusually high background, a characteristic associated with low affinity binding. Further characteristics of the induced Abs were evaluated by determining the avidity binding towards the envelope antigens. High avidity titers were observed in the protein boosted group (sera taken 2 weeks pre-challenge) followed by lower avidity titers by the VEE/SIN boosted group and the control group (Fig. 1 C).

FIG. 1.

Development of humoral binding responses pre and post SHIVSF162p4 challenge.

A: Titers of binding antibodies for each animal against peptide pools covering the gp120 of 89.6p or SHIVSF162p4 or against SIV Gag peptides were detected by ELISA. Binding titers were measured 2 weeks after each immunization and at various time points post-challenge. Black arrows indicate immunizations and the white arrow indicates IR SHIVSF162p4 challenge.

B: Pepscan analysis of sera from the individual animals. Reactivity with all overlapping 15-mer peptides of HIV-1SF162 gp120 were tested at a serum dilution of 1:100.

C: Quality (Antibody Avidity Index: HN4SCN concentration in M) of antibody responses induced by various immunization regimen. Sera before 1st immunization and after the 4th immunization (= 2 weeks pre-challenge) are shown.

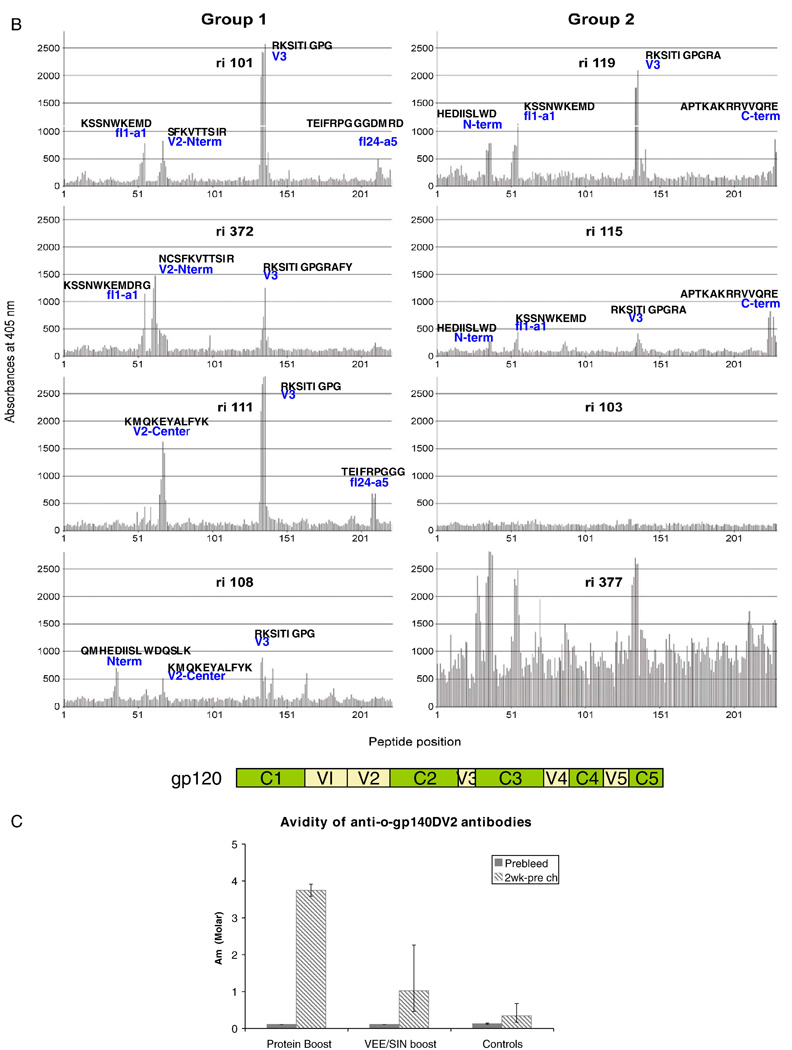

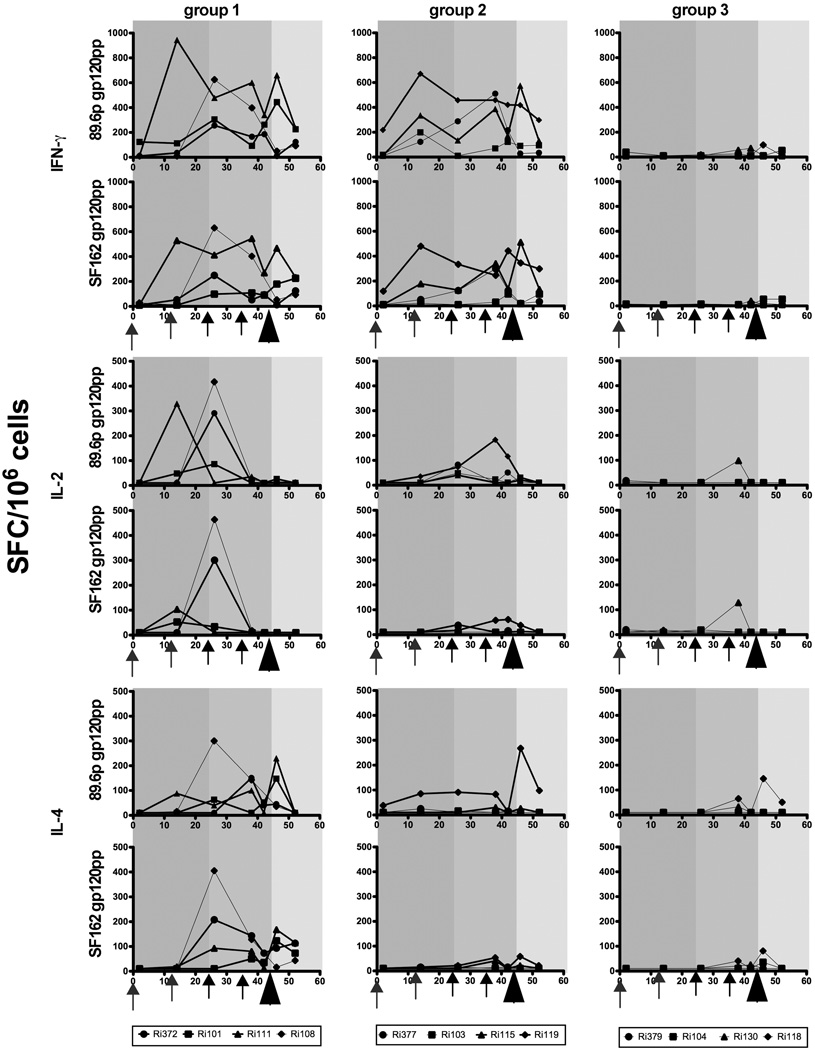

Functionality of the Abs were determined in two different assays. Virus-neutralizing capacity of sera was measured as a function of reduction (50% inhibition) in the standardized TZMbl luciferase reporter assay after a single round of infection (Wei et al., 2003) against pseudoviruses derived from clade B SHIV89.6p, SHIVSF162p3 and SHIVSF162p4 (Li et al., 2005; Montefiori, 2004). After the first booster immunization with either recombinant protein or VEE/SIN replicons, neutralization activity to SHIVSF162p4 developed in three of four and two of four animals respectively, and was boosted in all animals following the second booster immunization (Fig. 2A). Neutralizing Abs to SHIV89.6p and the SHIVSF162p3 pseudoviruses were not observed (data not shown). The outcome of the pseudotype neutralization assays with sera from the day of challenge were confirmed using rhesus PBMC-based assays (data not shown). In addition, we examined ADCC as collaborative functionality of the Abs induced by these immunization protocols. Target cells were coated with either HIV-189.6P gp140 or HIV-1SF162 gp120 protein and incubated with serial dilutions of the sera as described (Gomez-Roman et al., 2006a). All animals boosted with recombinant protein developed Abs which mediated ADCC to both antigens tested as did most of the animals in the VEE/SIN group (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Development of functional humoral responses pre and post SHIVSF162p4 challenge.

A: Neutralizing antibody responses against pseudovirus SHIVSF162p4 cl5.1B were evaluated throughout the immunization schedule. The serum dilutions giving 50% inhibition of SHIVSF162p4 cl5.1B infection of TZM-bl cells (Wei et al., 2003) are shown. Black arrows indicate immunizations and the white arrow indicates IR SHIVSF162p4 challenge.

B: ADCC using targets coated with 89.6P gp140 protein and SF162 gp120 protein. Expressed are titers giving specific lysis of target cells. The cut off for positive activity and determination of endpoint titer was 15.62% and was calculated from the mean of the means of all dilutions at week 0 for each sample plus 3 S.D.

C: Avidity of anti-o-gp140ΔV2 antibodies. Preserum and serum from week 42 were analysed for avidity.

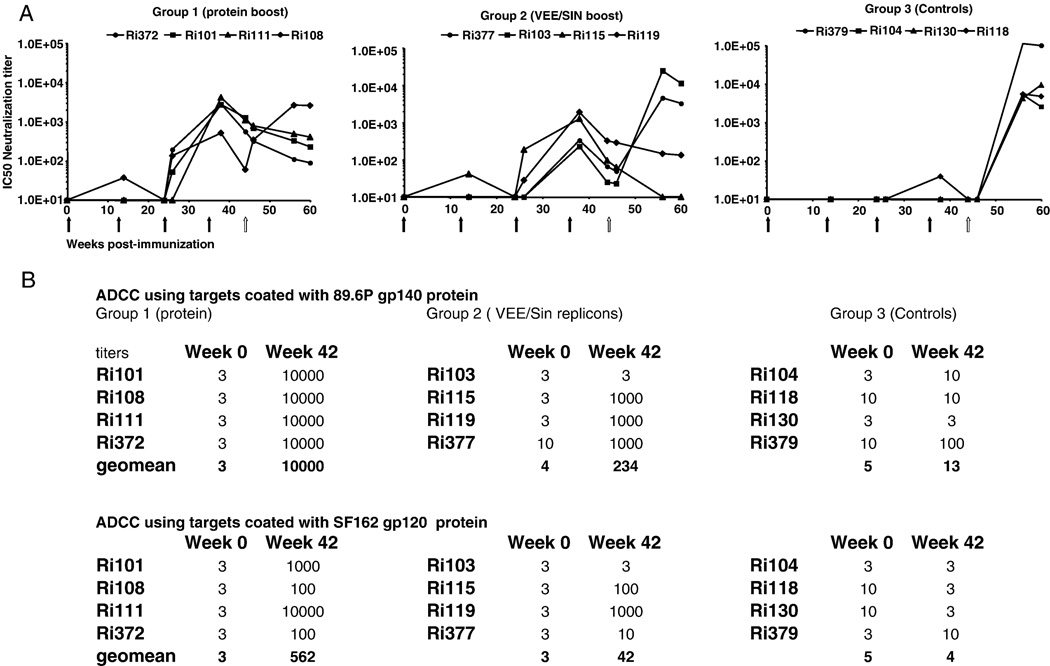

In addition to humoral responses, the induction of cellular immune responses were evaluated as well by quantification of antigen-specific cytokine-secreting cells (IFN-γ, IL-2 and IL-4) performed on freshly isolated PBMC by enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISpot) assays (Fig 3). Ad5hr priming resulted in IFNγ secreted cells in almost all vaccinated animals after they have been stimulated with the homologous antigen (Env pp of 89.6p) or by the Env pp of SF162. Boosting with recombinant glycoprotein (group 1) sustained high IFN-γ in all 4 animals while boosting with VEE/SIN replicons resulted in increased number of IFN-γ secreting cells in most of the animals (Fig 3). One booster immunization with recombinant protein resulted in an increase in IL-2 producing cells in most of the animals (responding to both 89.6p and SF126 antigens) but these population decreased in number after the second booster immunization. Booster with VEE/SIN replicons had only limited effect in the number of IL-2 producing cells. IL4 secreting cells were not induced after prime immunizations, but mainly induced after boosting with recombinant glycoproteins (Fig 3).

FIG 3.

T-cell ELISpot responses elicited over time. Shown are IFN-γ (upper panels), IL-2 (middle panels), and IL-4 (lower panels) ELISpots from individual animals immunized with Ad5hr vectors followed by recombinant glycoprotein (group 1) as a booster, VEE/SIN replicons (group 2) or MF59 only or empty VEE/SIN replicons (group 3). Background responses (mean numbers of SFC plus twice the standard deviations of triplicate assays with medium alone) were substracted. Responses after stimulation with either pp of 89.6p gp120 or SF162 gp120) are presented as the number of SFC per 106 PBMC. Arrows indicate immunizations, arrow head indicate the challenge. Bold lines indicate protected animals. The Y-ax scale for IFN-γ differs from IL-2 and IL-4 Y-axes.

Challenge outcome

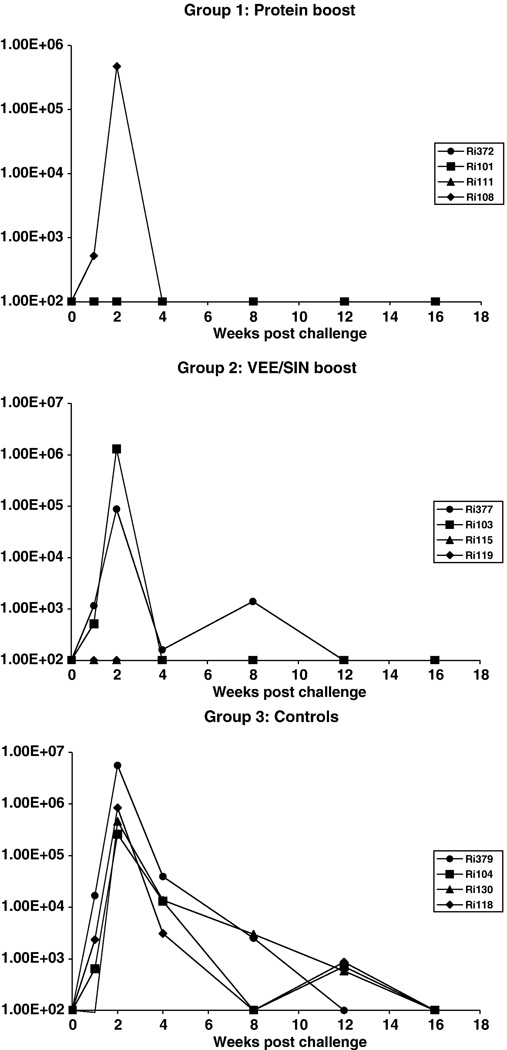

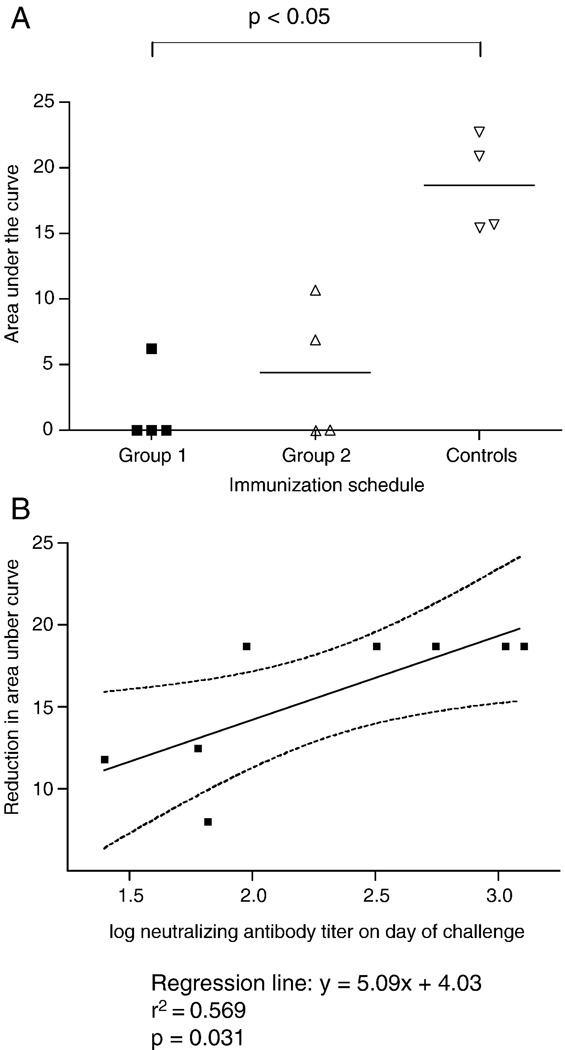

All control animals (group 3) became infected and developed peak viral loads between 2.6 × 105 and 5.6 × 106 RNA copies/ml in the acute phase of infection (Fig. 4). In 3 out of 4 animals of group 1 and 2 out of 4 animals of group 2, cell-free virus could not be detected in plasma. Furthermore, in these five animals no provirus containing PBMCs were detected with nested DNA-PCR (Bogers et al., 1995) at wk 2, 8 and 16 post challenge (data not shown). The infected animals in both immunized groups developed comparable maximum peak viral loads as the control group. However, by 4 weeks post challenge, vaccinees had already controlled the infection to undetectable levels. In contrast, the control group retained plasma viral burdens between 3.1 × 103 and 1.4 × 104 copies/ml at this same time point. Statistical comparison between the three groups (Kruskal-Wallis test) revealed a significant reduction (p=0.0157) in the area under the viral load curve. Application of Dunn’s Multiple Comparison test indicated a significant difference between group 1 and the controls (Fig. 5A).

FIG. 4.

Plasma viremia following IR challenge with SHIVSF162p4 of all animals from the recombinant glycoprotein boost group (upper panel), the VEE/SIN boost group (middle panel) and the control group (lower panel).

FIG. 5.

Reduction in virus load under the curve up to week 16 post challenge and correlation with neutralizing antibodies.

A: Area under the curve (of FIG. 4) up to week 16 post challenge. The horizontal lines indicate the median level of area under the curve of each group. Differences in area under the curve (log-transformed values) were analyzed and compared using the Kruskal-Wallis test. (H=8.312; p=0.0157).

B: Correlation between the neutralizing antibody titers at the day of challenge and the reduction in area under the curves (of FIG. 4).

Neutralizing antibody responses and reduced viral load

All immunized animals which exhibited Nab (IC50) titers greater than 1/80 at the time of challenge were protected by all parameters (negative plasma RNA and provirus in PBMC and tissues at all time points). Protection was independent of the booster immunization strategy. The immunized animals which did become infected developed neutralizing antibodies lower than 1/70 on the day of challenge (1/60 for Ri108, 1/66 for Ri377 and 1/25 for Ri103; Fig. 2A). Linear regression analysis of all macaques revealed a highly significant correlation between neutralisation titers on the day of challenge and protection (P=0.031) as well as reduced viral load over the 16 week post challenge period (Fig. 5B). This demonstrated a strong correlation between systemic Nabs titers, independent of the two booster immunisations, and protection against mucosal infection.

A protective correlation with cellular responses was not observed. Vaccinated but infected animals did show equal numbers of IFN-γ producing cells as produced by some of the protected animals. Also for IL-2 and IL-4 secreting cells, no clear protective correlation could be observed (Fig 3).

Post-challenge immune responses

To further explore the role of humoral immune responses in reduction of viral burden, we examined the anti-Env and anti-Gag Ab kinetics following intrarectal challenge (Fig. 1). Abs which bound SF162 peptides exhibited a booster response shortly after challenge, followed by a decrease in almost all immunized animals over time. In the protected animals this correlated with the absence of any plasma RNA antigen due to complete protection from infection. Peptide responses correlated with decreased neutralization activity in these protected animals in contrast to infected animals. The immunized, infected macaques exhibited increasing neutralizing titers which reached 1/2,500 – 1/24,000 by wk 12 post challenge, while uninfected macaques showed declining titers. In contrast de novo responses in the unvaccinated control group reached titers of 1/4,000 – 1/100,000 (Fig. 2A). Notably, neutralizing Abs titers in infected vaccinees correlated with accelerated clearance of plasma viral RNA from circulation. No clear contribution of cellular responses to viral clearance was observed in vaccinated infected animals (Fig 3). In contrast to vaccinated protected animals, all infected animals developed systemic anti-Gag responses (Fig. 1A) and mucosal anti-Gag responses (data not shown) after challenge. To determine whether local infections had possibly occurred in the protected animals, we carefully sampled multiple mucosal (colon, jejunum and ileum) and draining lymphoid (mesenteric lymph nodes, inguinal, and draining iliac lymph nodes) tissues on the day of necropsy (week 20). These tissues were processed and examined for the presence of provirus by nested DNA-PCR. Importantly, no provirus was detected in any of these multiple tissue samples from protected vaccinees. In contrast, the tissues taken from infected animals were routinely provirus positive.

Discussion

Accumulating evidence indicates that an effective vaccine against HIV will likely need to induce broad humoral, cellular and mucosal immunity to a wide diversity of viral variants. The use of replicating Adeno vectors as vaccine candidates has been proven to induce potent cellular immunity and prime high-titer Abs (Peng et al., 2005; Zhao et al., 2003). HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein is a vaccine immunogenic of particular interest because it can serve as a potent target antigen for both T-lymphocyte and antibody responses (Letvin et al., 2004; Mascola et al., 2005). Especially the HIV-1SF162 gp140ΔV2 vaccine used in this study has proven to elicite broad, potent neutralizing Abs capacities (Barnett et al., 2001). The use of VEE/SIN chimeric alphavirus replicon particles has also been shown to elicit the generation of robust neutralizing Ab responses as well as cell-mediated responses to multiple viral antigens (Xu et al., 2006). The current proof of concept study confirmed that a mucosal adeno priming and systemic recombinant glycoprotein boosting regimen is capable of eliciting immunity sufficient to reduce acute-phase and set point viremia after mucosal challenge (Patterson et al., 2004; Zhao et al., 2003). However, we extend these observations and demonstrate that these strategies are able to elicit neutralizing antibodies and ADCC systemically which correlate with protection from mucosal infection.

In recent studies with VEE replicon or chimeric VEE/SIN replicon particles as vaccine vectors, Nabs were generated either after 3 systemic immunizations with the corresponding vector only (Johnston et al., 2005) or after a booster with recombinant gp140 protein (Xu et al., 2006). However, despite the fact that VEE or VEE/SIN immunization resulted in reduction of viral loads in both studies (after an intrarectal or intravenous challenge respectively), no sterilizing immunity (Johnston et al., 2005) or limited control (Xu et al., 2006) was achieved. Here we demonstrate that also with a mucosal adeno-prime and systemic VEE/SIN boosting regimen, it is possible to eliciting immunity sufficient to protect from mucosal challenge. The lack of detectable viral DNA in PBMC, various mucosal tissues and lymphoid organs in the protected animals indicate that sterilizing immunity can be obtained. As observed with the recombinant glycoprotein booster regimen, the VEE/SIN booster regimen induced Nab threshold which correlated with protection from detectable infection in the majority of immunized animals. In the remaining immunized animals lower Nab titers correlated with control of plasma viral RNA load.

All animals protected from infection showed peptide binding responses towards both V1 and V3 epitopes (Fig 1B). Binding towards V2 epitopes does not seem to be essential because of the absence of V2 binding seen in the two protected animals which were boosted with VEE/SIN replicons expressing the HIV-1SF162 gp140 with a V2 deletion. It is likely that the Pepscan analysis may not detect conformational epitopes (Davis et al., 1990) especially those similar to the known neutralizing human antibodies. The current analysis was limited to the external envelope glycoprotein since peptides to the transmembrane glycoprotein (gp41) were not available at the time of this study. Srivastava et al (Srivastava et al., 2002) have shown that not only the magnitude (binding) but also the quality (avidity) of antibody responses induced by protein vaccination increased after subsequent boosts indicating a maturation in the functionality of the antibodies. We have only analyzed the avidity of the induced antibodies to SF162 gp140 after the final immunization. This differed between both groups. Protein boosting resulted in higher avidity as compared to the VEE/SIN boosting.

During the prime phase, homologous binding Abs were induced in all 8 animals (Fig 1A) but these Abs could not neutralize homologous SHIV89.6p (data not shown) nor SHIVSF162p4 (Fig 2A). Already after one booster immunization with recombinant glycoproteins, the induction of neutralization Abs (towards the booster vaccine strain) started to increase in parallel with the induction of IFN-γ, IL-2 as well as IL-4 secreting cells. The apparent collaborative functionality (ADCC titers) with Nab responses was not statistically supported due to the low numbers of ‘partially protected’ animals. Both functional assays were conducted to determine cross-reactivity against the various vaccine antigens. In contrast to Nab responses, which did not neutralize 89.6p, ADCC reactivity could be determined against both antigens. The higher titers with the 89.6p gp140 protein might have resulted from priming with the matched Ad-recombinant. However, it is possible that we could have seen higher titers if we used SF162 gp140 protein as it has been shown that some epitopes for ADCC are also located on gp41 (Ahmad et al., 1994; Nixon et al., 1992). Both humoral and cellular responses were also induced in the VEE/SIN group but here cellular responses were limited to IFN-γ responses. In summary, we have shown that heterologous vaccination strategies with two different booster immunogens induces NAbs which, when reached a certain threshold level, correlates with protection from infection. The induced Nabs responses were limited to the booster vaccine strain. This in contrast to generated homologous and heterologous ADCC antibodies as well as cellular immunity which responded after both homologous and heterologous antigen stimulations. These studies indicate that sequential immunizations with different envelope antigens may not generate broad immune responses (especially the lack of broad neutralizing activity) needed for (heterologous) efficacy. Instead, combined applications of different (envelope) antigens in both prime as well as booster immunizations simultaneously may be required for even broader immune responses (Demberg et al., 2007; Patterson et al., 2004; Seaman et al., 2007).

Materials and Methods

Rhesus macaques

Twelve rhesus macaques of Indian origin (9 males and 3 females; age > 4 years; weight 5–15 kg) housed in environmentally controlled conditions at the BPRC were included in the study and divided in three groups (each with 3 males and 1 female). All animals were negative for SIV, simian retrovirus and simian T-cell leukemia virus. During the course of the study, animals were checked twice daily for appetite and general behavior and stools were checked for consistency. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved the study protocol according to international ethical and scientific standards and guidelines.

Immunization and challenge schedule

Two groups of 4 animals each were primed first via the intranasal (IN) route and twelve weeks later via the intratreacheal (IT) route. Both immunizations involved 5×108 pfu with replication-competent Ad5hrΔE3-HIV-189.6PEnv gp140 (Demberg et al., 2007). Animals from the first group were boosted twice intramuscularly (IM) with 100 µg recombinant gp140 of HIV-1SF162 in MF59 at weeks 24 and 36 (Barnett et al., 2001; Srivastava et al., 2003), while the second group received 2x IM 108 pfu VEE/SIN replicons expressing the HIV-1SF162 gp140 with a V2 deletion (ΔV2) (Xu et al., 2006). Control animals (group 3) received empty Ad5hr vectors followed by either adjuvant only (n=2) or empty VEE/SIN replicons (n=2). Efficacy was evaluated utilising the IR mucosal challenge of a R5-tropic SHIVSF162p4 mucosal challenge stock (Harouse et al., 1999) at week 44 (1 ml =1800 TCID50).

Quanitation of plasma viral RNA and proviral DNA in peripheral blood and tissues

SHIV viral loads were determined using an adaptated version of a published SIV-gag-based real-time PCR assay (Leutenegger et al., 2001). The SIV-probe used was identical to the probe described by Leutenegger et al., except that we used the quencher dye Black Hole Quencer 2 instead of TAMRA. The forward (SIV31) and reverse (SIV41) primers were essentially identical to primers SIV.510f and SIV.592r (Leutenegger et al), with minor modifications to improve the sensitivity of the assay. The SIV31 and SIV41 primer sequences were 5’-CCAGGATTTCAGGCACTGTC-3’ AND 5’-GCTTGATGGTCTCCCACACA-3’, respectively. The PCR was carried out using the Brilliant® QRT-PCR Core Reagent Kit, 1-Step (Stratagene Europe, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) in a 25 µl volume with final concentrations of 160 nM for each primer, 200 nM for the probe, 5.5 nM MgCl2, and using 10 µl RNA. RNA was reverse transcribed for 30 min at 45°C. Then, after a 10 min incubation step at 95°C, the cDNA was amplified for 40 cycles, consisting of 15 sec denaturation at 95°C, followed by a 1 min annealing-extension step at 60°C. All the reactions were carried out with an iQ™5 Multicolor Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories BV, Veenendaal, The Netherlands). Detection limit is 100 RNA copies/ml.

DNA-PCR were performed in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) at different timepoints after challenge as well as multiple mucosal (colon, jejunum and ileum) and draining lymphoid (mesenteric lymph nodes, inguinal, and draining iliac lymph nodes) tissues on the day of necropsy (week 20) by nested DNA PCR as described (Bogers et al., 1995). This assay is able to detect a single proviral copy in a background of 1 µg template DNA.

Measurement of immune responses

Antibodies specific for peptide pools (pp) spanning the entire gp120 of HIV-189.6P and for gp120 peptides of SHIVSF162P4 as well as SIV gag peptides (NIH AIDS Research and ReferenceReagent Program, Rockville, MD) were determined in serum using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay technique as previously described (Mooij et al., 2000). Individual peptide binding analyses were performed on a solid support and screening of antibody binding was studied by pepscan analysis as described (Langedijk et al., 1997; Slootstra et al., 1996). Furthermore, the antibody avidity index was determined using an ammonium thiocyanate displacement (NH4SCN) ELISA as described elsewhere in detail (Srivastava et al., 2002). Virus-neutralizing capacity of sera was measured as a function of reduction (50% inhibition) in the standardized TZMbl luciferase reporter assay after a single round of infection (Wei et al., 2003) against pseudoviruses derived from clade B SHIV89.6p, SHIVSF162p3 and SHIVSF162p4 (Li et al., 2005; Montefiori, 2004).

Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) was performed using the rapid fluorometric assessment as described previously (Gomez-Roman et al., 2006a). The quantification of antigen-specific cytokine-secreting cells was performed on freshly isolated PBMC by IFN-γ, IL-2 and IL-4 enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISpot) assays as described (Koopman et al., 2008; Mooij et al., 2008)

Statistical analysis

A non-parametric ANOVA Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare virus load between the control group of unvaccinated animals and the different vaccinated groups. Statistical analysis was performed for differences in area’s under the viral load curves of the various groups. Correlation between neutralizing Ab titers and reduction in area under the curve was calculated by using linear regression analyses.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, and by Federal funds from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract No. 1 P01 AI48225-01A2 and No. 5 PO1 AI066287-02.

References

- Ahmad A, Morisset R, Thomas R, Menezes J. Evidence for a defect of antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxic (ADCC) effector function and anti-HIV gp120/41-specific ADCC-mediating antibody titres in HIV-infected individuals. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1994;7(5):428–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amara RR, Villinger F, Altman JD, Lydy SL, O’Neil SP, Staprans SI, Montefiori DC, Xu Y, Herndon JG, Wyatt LS, Candido MA, Kozyr NL, Earl PL, Smith JM, Ma HL, Grimm BD, Hulsey ML, Miller J, McClure HM, McNicholl JM, Moss B, Robinson HL. Control of a mucosal challenge and prevention of AIDS by a multiprotein DNA/MVA vaccine. Science. 2001;292(5514):69–74. doi: 10.1126/science.1058915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett SW, Lu S, Srivastava I, Cherpelis S, Gettie A, Blanchard J, Wang S, Mboudjeka I, Leung L, Lian Y, Fong A, Buckner C, Ly A, Hilt S, Ulmer J, Wild CT, Mascola JR, Stamatatos L. The ability of an oligomeric human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) envelope antigen to elicit neutralizing antibodies against primary HIV-1 isolates is improved following partial deletion of the second hypervariable region. J Virol. 2001;75(12):5526–5540. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.12.5526-5540.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertley FM, Kozlowski PA, Wang SW, Chappelle J, Patel J, Sonuyi O, Mazzara G, Montefiori D, Carville A, Mansfield KG, Aldovini A. Control of simian/human immunodeficiency virus viremia and disease progression after IL-2-augmented DNA-modified vaccinia virus Ankara nasal vaccination in nonhuman primates. J Immunol. 2004;172(6):3745–3757. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogers WM, Niphuis H, ten Haaft P, Laman JD, Koornstra W, Heeney JL. Protection from HIV-1 envelope-bearing chimeric simian immunodeficiency virus (SHIV) in rhesus macaques infected with attenuated SIV: consequences of challenge. Aids. 1995;9(12):F13–F18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buge SL, Richardson E, Alipanah S, Markham P, Cheng S, Kalyan N, Miller CJ, Lubeck M, Udem S, Eldridge J, Robert-Guroff M. An adenovirus-simian immunodeficiency virus env vaccine elicits humoral, cellular, and mucosal immune responses in rhesus macaques and decreases viral burden following vaginal challenge. J Virol. 1997;71(11):8531–8541. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8531-8541.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton DR, Desrosiers RC, Doms RW, Koff WC, Kwong PD, Moore JP, Nabel GJ, Sodroski J, Wilson IA, Wyatt RT. HIV vaccine design and the neutralizing antibody problem. Nat Immunol. 2004;5(3):233–236. doi: 10.1038/ni0304-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caley IJ, Betts MR, Irlbeck DM, Davis NL, Swanstrom R, Frelinger JA, Johnston RE. Humoral, mucosal, and cellular immunity in response to a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 immunogen expressed by a Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus vaccine vector. J Virol. 1997;71(4):3031–3038. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.3031-3038.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles PC, Brown KW, Davis NL, Hart MK, Johnston RE. Mucosal immunity induced by parenteral immunization with a live attenuated Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus vaccine candidate. Virology. 1997;228(2):153–160. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.8381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crotty S, Miller CJ, Lohman BL, Neagu MR, Compton L, Lu D, Lu FX, Fritts L, Lifson JD, Andino R. Protection against simian immunodeficiency virus vaginal challenge by using Sabin poliovirus vectors. J Virol. 2001;75(16):7435–7452. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.16.7435-7452.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis D, Stephens DM, Willers C, Lachmann PJ. Glycosylation governs the binding of antipeptide antibodies to regions of hypervariable amino acid sequence within recombinant gp120 of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Gen Virol. 1990;71(Pt 12):2889–2898. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-12-2889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis NL, Brown KW, Johnston RE. A viral vaccine vector that expresses foreign genes in lymph nodes and protects against mucosal challenge. J Virol. 1996;70(6):3781–3787. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3781-3787.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis NL, Caley IJ, Brown KW, Betts MR, Irlbeck DM, McGrath KM, Connell MJ, Montefiori DC, Frelinger JA, Swanstrom R, Johnson PR, Johnston RE. Vaccination of macaques against pathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus with Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus replicon particles. J Virol. 2000;74(1):371–378. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.1.371-378.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demberg T, Florese RH, Heath MJ, Larsen K, Kalisz I, Kalyanaraman VS, Lee EM, Pal R, Venzon D, Grant R, Patterson LJ, Korioth-Schmitz B, Buzby A, Dombagoda D, Montefiori DC, Letvin NL, Cafaro A, Ensoli B, Robert-Guroff M. A replication-competent adenovirus-human immunodeficiency virus (Ad-HIV) tat and Ad-HIV env priming/Tat and envelope protein boosting regimen elicits enhanced protective efficacy against simian/human immunodeficiency virus SHIV89.6P challenge in rhesus macaques. J Virol. 2007;81(7):3414–3427. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02453-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doria-Rose NA, Ohlen C, Polacino P, Pierce CC, Hensel MT, Kuller L, Mulvania T, Anderson D, Greenberg PD, Hu SL, Haigwood NL. Multigene DNA priming-boosting vaccines protect macaques from acute CD4+-T-cell depletion after simian-human immunodeficiency virus SHIV89.6P mucosal challenge. J Virol. 2003;77(21):11563–11577. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.21.11563-11577.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Roman VR, Florese RH, Patterson LJ, Peng B, Venzon D, Aldrich K, Robert-Guroff M. A simplified method for the rapid fluorometric assessment of antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity. J Immunol Methods. 2006a;308(1–2):53–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2005.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Roman VR, Florese RH, Peng B, Montefiori DC, Kalyanaraman VS, Venzon D, Srivastava I, Barnett SW, Robert-Guroff M. An adenovirus-based HIV subtype B prime/boost vaccine regimen elicits antibodies mediating broad antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity against non-subtype B HIV strains. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006b;43(3):270–277. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000230318.40170.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harouse JM, Gettie A, Tan RC, Blanchard J, Cheng-Mayer C. Distinct pathogenic sequela in rhesus macaques infected with CCR5 or CXCR4 utilizing SHIVs. Science. 1999;284(5415):816–819. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston RE, Johnson PR, Connell MJ, Montefiori DC, West A, Collier ML, Cecil C, Swanstrom R, Frelinger JA, Davis NL. Vaccination of macaques with SIV immunogens delivered by Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus replicon particle vectors followed by a mucosal challenge with SIVsmE660. Vaccine. 2005;23(42):4969–4979. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopman G, Mortier D, Hofman S, Mathy N, Koutsoukos M, Ertl P, Overend P, van Wely C, Thomsen LL, Wahren B, Voss G, Heeney JL. Immune-response profiles induced by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vaccine DNA, protein or mixed-modality immunization: increased protection from pathogenic simian-human immunodeficiency virus viraemia with protein/DNA combination. J Gen Virol. 2008;89(Pt 2):540–553. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83384-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langedijk JP, Meloen RH, Taylor G, Furze JM, van Oirschot JT. Antigenic structure of the central conserved region of protein G of bovine respiratory syncytial virus. J Virol. 1997;71(5):4055–4061. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.4055-4061.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letvin NL, Huang Y, Chakrabarti BK, Xu L, Seaman MS, Beaudry K, Korioth-Schmitz B, Yu F, Rohne D, Martin KL, Miura A, Kong WP, Yang ZY, Gelman RS, Golubeva OG, Montefiori DC, Mascola JR, Nabel GJ. Heterologous envelope immunogens contribute to AIDS vaccine protection in rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 2004;78(14):7490–7497. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.14.7490-7497.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leutenegger CM, Higgins J, Matthews TB, Tarantal AF, Luciw PA, Pedersen NC, North TW. Real-time TaqMan PCR as a specific and more sensitive alternative to the branched-chain DNA assay for quantitation of simian immunodeficiency virus RNA. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2001;17(3):243–251. doi: 10.1089/088922201750063160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Gao F, Mascola JR, Stamatatos L, Polonis VR, Koutsoukos M, Voss G, Goepfert P, Gilbert P, Greene KM, Bilska M, Kothe DL, Salazar-Gonzalez JF, Wei X, Decker JM, Hahn BH, Montefiori DC. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 env clones from acute and early subtype B infections for standardized assessments of vaccine-elicited neutralizing antibodies. J Virol. 2005;79(16):10108–10125. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10108-10125.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubeck MD, Natuk R, Myagkikh M, Kalyan N, Aldrich K, Sinangil F, Alipanah S, Murthy SC, Chanda PK, Nigida SM, Jr, Markham PD, Zolla-Pazner S, Steimer K, Wade M, Reitz MS, Jr, Arthur LO, Mizutani S, Davis A, Hung PP, Gallo RC, Eichberg J, Robert-Guroff M. Long-term protection of chimpanzees against high-dose HIV-1 challenge induced by immunization. Nat Med. 1997;3(6):651–658. doi: 10.1038/nm0697-651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascola JR, Sambor A, Beaudry K, Santra S, Welcher B, Louder MK, Vancott TC, Huang Y, Chakrabarti BK, Kong WP, Yang ZY, Xu L, Montefiori DC, Nabel GJ, Letvin NL. Neutralizing antibodies elicited by immunization of monkeys with DNA plasmids and recombinant adenoviral vectors expressing human immunodeficiency virus type 1 proteins. J Virol. 2005;79(2):771–779. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.2.771-779.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montefiori DC. Coligan AMKJE, Margulies DH, Shevach EM, Strober W, Coico R. Current Protocols in Immunology. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 2004. Evaluating neutralizing antibodies against HIV, SIV, and SHIV in luciferase reporter gene assays; pp. 12.11.1–12.11.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooij P, Balla-Jhagjhoorsingh SS, Koopman G, Beenhakker N, van Haaften P, Baak I, Nieuwenhuis IG, Kondova I, Wagner R, Wolf H, Gomez CE, Najera JL, Jimenez V, Esteban M, Heeney JL. Differential CD4+ versus CD8+ T-cell responses elicited by different poxvirus-based human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vaccine candidates provide comparable efficacies in primates. J Virol. 2008;82(6):2975–2988. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02216-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooij P, Bogers WM, Oostermeijer H, Koornstra W, Ten Haaft PJ, Verstrepen BE, Van Der Auwera G, Heeney JL. Evidence for viral virulence as a predominant factor limiting human immunodeficiency virus vaccine efficacy. J Virol. 2000;74(9):4017–4027. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.9.4017-4027.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossman SP, Bex F, Berglund P, Arthos J, O’Neil SP, Riley D, Maul DH, Bruck C, Momin P, Burny A, Fultz PN, Mullins JI, Liljestrom P, Hoover EA. Protection against lethal simian immunodeficiency virus SIVsmmPBj14 disease by a recombinant Semliki Forest virus gp160 vaccine and by a gp120 subunit vaccine. J Virol. 1996;70(3):1953–1960. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1953-1960.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossman SP, Pierce CC, Watson AJ, Robertson MN, Montefiori DC, Kuller L, Richardson BA, Bradshaw JD, Munn RJ, Hu SL, Greenberg PD, Benveniste RE, Haigwood NL. Protective immunity to SIV challenge elicited by vaccination of macaques with multigenic DNA vaccines producing virus-like particles. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2004;20(4):425–434. doi: 10.1089/088922204323048177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negri DR, Baroncelli S, Catone S, Comini A, Michelini Z, Maggiorella MT, Sernicola L, Crostarosa F, Belli R, Mancini MG, Farcomeni S, Fagrouch Z, Ciccozzi M, Boros S, Liljestrom P, Norley S, Heeney J, Titti F. Protective efficacy of a multicomponent vector vaccine in cynomolgus monkeys after intrarectal simian immunodeficiency virus challenge. J Gen Virol. 2004;85(Pt 5):1191–1201. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.79794-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon DF, Broliden K, Ogg G, Broliden PA. Cellular and humoral antigenic epitopes in HIV and SIV. Immunology. 1992;76(4):515–534. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson LJ, Malkevitch N, Pinczewski J, Venzon D, Lou Y, Peng B, Munch C, Leonard M, Richardson E, Aldrich K, Kalyanaraman VS, Pavlakis GN, Robert-Guroff M. Potent, persistent induction and modulation of cellular immune responses in rhesus macaques primed with Ad5hr-simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) env/rev, gag, and/or nef vaccines and boosted with SIV gp120. J Virol. 2003;77(16):8607–8620. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.16.8607-8620.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson LJ, Malkevitch N, Venzon D, Pinczewski J, Gomez-Roman VR, Wang L, Kalyanaraman VS, Markham PD, Robey FA, Robert-Guroff M. Protection against mucosal simian immunodeficiency virus SIV(mac251) challenge by using replicating adenovirus-SIV multigene vaccine priming and subunit boosting. J Virol. 2004;78(5):2212–2221. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.5.2212-2221.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng B, Wang LR, Gomez-Roman VR, Davis-Warren A, Montefiori DC, Kalyanaraman VS, Venzon D, Zhao J, Kan E, Rowell TJ, Murthy KK, Srivastava I, Barnett SW, Robert-Guroff M. Replicating rather than nonreplicating adenovirus-human immunodeficiency virus recombinant vaccines are better at eliciting potent cellular immunity and priming high-titer antibodies. J Virol. 2005;79(16):10200–10209. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10200-10209.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perri S, Greer CE, Thudium K, Doe B, Legg H, Liu H, Romero RE, Tang Z, Bin Q, Dubensky TW, Jr, Vajdy M, Otten GR, Polo JM. An alphavirus replicon particle chimera derived from venezuelan equine encephalitis and sindbis viruses is a potent gene-based vaccine delivery vector. J Virol. 2003;77(19):10394–10403. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.19.10394-10403.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polacino P, Stallard V, Montefiori DC, Brown CR, Richardson BA, Morton WR, Benveniste RE, Hu SL. Protection of macaques against intrarectal infection by a combination immunization regimen with recombinant simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmne gp160 vaccines. J Virol. 1999;73(4):3134–3146. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.3134-3146.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinnan GV, Jr, Yu XF, Lewis MG, Zhang PF, Sutter G, Silvera P, Dong M, Choudhary A, Sarkis PT, Bouma P, Zhang Z, Montefiori DC, Vancott TC, Broder CC. Protection of rhesus monkeys against infection with minimally pathogenic simian-human immunodeficiency virus: correlations with neutralizing antibodies and cytotoxic T cells. J Virol. 2005;79(6):3358–3369. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.6.3358-3369.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert-Guroff M, Kaur H, Patterson LJ, Leno M, Conley AJ, McKenna PM, Markham PD, Richardson E, Aldrich K, Arora K, Murty L, Carter L, Zolla-Pazner S, Sinangil F. Vaccine protection against a heterologous, non-syncytium-inducing, primary human immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1998;72(12):10275–10280. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.10275-10280.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaman MS, Leblanc DF, Grandpre LE, Bartman MT, Montefiori DC, Letvin NL, Mascola JR. Standardized assessment of NAb responses elicited in rhesus monkeys immunized with single- or multi-clade HIV-1 envelope immunogens. Virology. 2007;367(1):175–186. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiver JW, Fu TM, Chen L, Casimiro DR, Davies ME, Evans RK, Zhang ZQ, Simon AJ, Trigona WL, Dubey SA, Huang L, Harris VA, Long RS, Liang X, Handt L, Schleif WA, Zhu L, Freed DC, Persaud NV, Guan L, Punt KS, Tang A, Chen M, Wilson KA, Collins KB, Heidecker GJ, Fernandez VR, Perry HC, Joyce JG, Grimm KM, Cook JC, Keller PM, Kresock DS, Mach H, Troutman RD, Isopi LA, Williams DM, Xu Z, Bohannon KE, Volkin DB, Montefiori DC, Miura A, Krivulka GR, Lifton MA, Kuroda MJ, Schmitz JE, Letvin NL, Caulfield MJ, Bett AJ, Youil R, Kaslow DC, Emini EA. Replication-incompetent adenoviral vaccine vector elicits effective anti-immunodeficiency-virus immunity. Nature. 2002;415(6869):331–335. doi: 10.1038/415331a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slootstra JW, Puijk WC, Ligtvoet GJ, Langeveld JP, Meloen RH. Structural aspects of antibody-antigen interaction revealed through small random peptide libraries. Mol Divers. 1996;1(2):87–96. doi: 10.1007/BF01721323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava IK, Stamatatos L, Kan E, Vajdy M, Lian Y, Hilt S, Martin L, Vita C, Zhu P, Roux KH, Vojtech LDCM, Donnelly J, Ulmer JB, Barnett SW. Purification, characterization, and immunogenicity of a soluble trimeric envelope protein containing a partial deletion of the V2 loop derived from SF162, an R5-tropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate. J Virol. 2003;77(20):11244–11259. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.20.11244-11259.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava IK, Stamatatos L, Legg H, Kan E, Fong A, Coates SR, Leung L, Wininger M, Donnelly JJ, Ulmer JB, Barnett SW. Purification and characterization of oligomeric envelope glycoprotein from a primary R5 subtype B human immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 2002;76(6):2835–2847. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.6.2835-2847.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei X, Decker JM, Wang S, Hui H, Kappes JC, Wu X, Salazar-Gonzalez JF, Salazar MG, Kilby JM, Saag MS, Komarova NL, Nowak MA, Hahn BH, Kwong PD, Shaw GM. Antibody neutralization and escape by HIV-1. Nature. 2003;422(6929):307–312. doi: 10.1038/nature01470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu R, Srivastava IK, Greer CE, Zarkikh I, Kraft Z, Kuller L, Polo JM, Barnett SW, Stamatatos L. Characterization of immune responses elicited in macaques immunized sequentially with chimeric VEE/SIN alphavirus replicon particles expressing SIVGag and/or HIVEnv and with recombinant HIVgp140Env protein. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2006;22(10):1022–1030. doi: 10.1089/aid.2006.22.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Pinczewski J, Gomez-Roman VR, Venzon D, Kalyanaraman VS, Markham PD, Aldrich K, Moake M, Montefiori DC, Lou Y, Pavlakis GN, Robert-Guroff M. Improved protection of rhesus macaques against intrarectal simian immunodeficiency virus SIV(mac251) challenge by a replication-competent Ad5hr-SIVenv/rev and Ad5hr-SIVgag recombinant priming/gp120 boosting regimen. J Virol. 2003;77(15):8354–8365. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.15.8354-8365.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolla-Pazner S, Lubeck M, Xu S, Burda S, Natuk RJ, Sinangil F, Steimer K, Gallo RC, Eichberg JW, Matthews T, Robert-Guroff M. Induction of neutralizing antibodies to T-cell line-adapted and primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates with a prime-boost vaccine regimen in chimpanzees. J Virol. 1998;72(2):1052–1059. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1052-1059.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]