Abstract

The E2F transcription factors are key downstream targets of the retinoblastoma protein tumor suppressor. They are known to regulate the expression of genes that control fundamental biological processes including cellular proliferation, apoptosis and differentiation. However, considerable questions remain about the precise roles of the individual E2F family members. This study shows that E2F3 is essential for normal cardiac development. E2F3-loss impairs the proliferative capacity of the embryonic myocardium and most E2f3−/− mice die in utero or perinatally with hypoplastic ventricular walls and/or severe atrial and ventricular septal defects. A small fraction of the E2f3−/− neonates have hearts that appear grossly normal and they initially survive. However, these animals develop ultrastructural defects in the cardiac muscle and ultimately die as a result of congestive heart failure. These data demonstrate a clear link between E2F3’s role in the proliferative capacity of the myocardium and cardiac function during both development and adulthood.

Keywords: E2f, proliferation, cardiac, hypoplastic, congestive heart failure

Introduction

The E2F transcription factors function as key regulators of proliferation by controlling the synthesis of genes that regulate entry into and passage through the cell cycle 1–3. E2F activity is regulated by a family of proteins, called the pocket proteins, which includes the retinoblastoma protein (pRB) tumor suppressor, p107 and p130. When hypo-phosphorylated, the pocket proteins can bind to E2F and inhibit the expression of E2F-responsive genes in two ways. First, the pocket proteins bind to a small motif within the transactivation domain and this appears to be sufficient to block its function. Second, the resulting pocket protein E2F complex can recruit factors such as histone deacetylases, nucleosome remodeling enzymes, and histone methyltransferases to the promoters of E2F target genes and actively repress their transcription 4. Phosphorylation of the pocket proteins by the cyclin-dependent kinases (cdks) triggers the release of E2F and the activation of responsive genes. Most, if not all, human tumors contain mutations that lead to the functional inactivation of pRB 5. This strongly suggests that deregulation of E2F is a key step in the tumorigenic process.

To date, nine E2F proteins have been identified 1, 2. These can be divided into several distinct subclasses based on differences in sequence homology and, in many cases, demonstrated differences in functional properties. Two of the E2F proteins, E2F3a and E2F3b, are encoded by a single locus through the use of different promoters and 5’ coding exons 6–8. These proteins share the domains required for DNA binding, heterodimerization, pocket protein binding and transactivation but they have distinct N-termini comprising either 123 (E2F3a) or 6 (E2F3b) amino acids. E2F3a has been extensively characterized. Based on its properties it has been classified as a member of an E2F subgroup, called the activating E2Fs, that includes E2F1, E2F2 and E2F3a. These E2Fs are all potent transcriptional activators and their over-expression is sufficient to drive quiescent cells to re-enter the cell cycle 9, 10. Their activity is specifically regulated by pRB, not p107 or p130, in normal cells 11. Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays show that the activating E2Fs associate with E2F-responsive promoters in late G1, consistent with the timing of activation of these genes 12. E2F3b is less well characterized, however, analyses of E2f3a and E2f3b specific knockouts shows that these two isoforms have largely overlapping properties in vivo 13, 14.

We have previously generated an E2f3 mutant mouse strain that lacks both the E2F3a and E2F3b proteins 15. For simplicity, we will refer to these mice as E2f3−/− or E2F3-deficient. Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) derived from E2f3−/− animals have a severe defect in cellular proliferation and in the mitogen-induced activation of E2F-responsive genes 15. E2F3-loss also has a profound effect on the viability of the mice 15, 16. In a pure 129/Sv background, it causes embryonic lethality with complete penetrance. However, in a mixed (C57BL/6 × 129/Sv) background, approximately 30% of E2f3−/− mice die in utero, 45% of the animals die within 24 hours of birth, and 25% survive to adulthood. Surprisingly, the adult E2f3−/− mice develop congestive heart failure with high penetrance (∼85%) with an average age of 17 months. In this study, we have analyzed the heart defect and show that E2F3 is required for normal heart morphology, the proliferative capacity of myocardium, as well as for establishing normal muscle ultrastructure and therefore plays an essential role in heart development during both embryonic and perinatal phases.

Results

E2F3-Loss Impairs the Proliferation of the Developing Myocardium

The predisposition of adult E2f3−/− mice to develop congestive heart failure revealed an unexpected role for E2F3 in adult cardiac function. We have previously shown that E2F3 plays a key role in both asynchronous proliferation and cell cycle re-entry from the quiescent state, at least in MEFs and that E2f3a and E2f3b contribute to this process 13, 15. Cardiomyocytes are known to undergo two distinct growth phases during normal development. They proliferate extensively in mid-gestation and then undergo hypertrophic growth (essentially a variant cell cycle that involves cell growth and typically binucleation without cell division) during the perinatal period 17, 18. Strikingly, the time of death of most of the E2f3−/− mice coincides exactly with these two timepoints 16. Based on these observations, we hypothesized that this might reflect a requirement for E2F3 in ensuring the appropriate cell cycle capacity of the developing cardiac muscle.

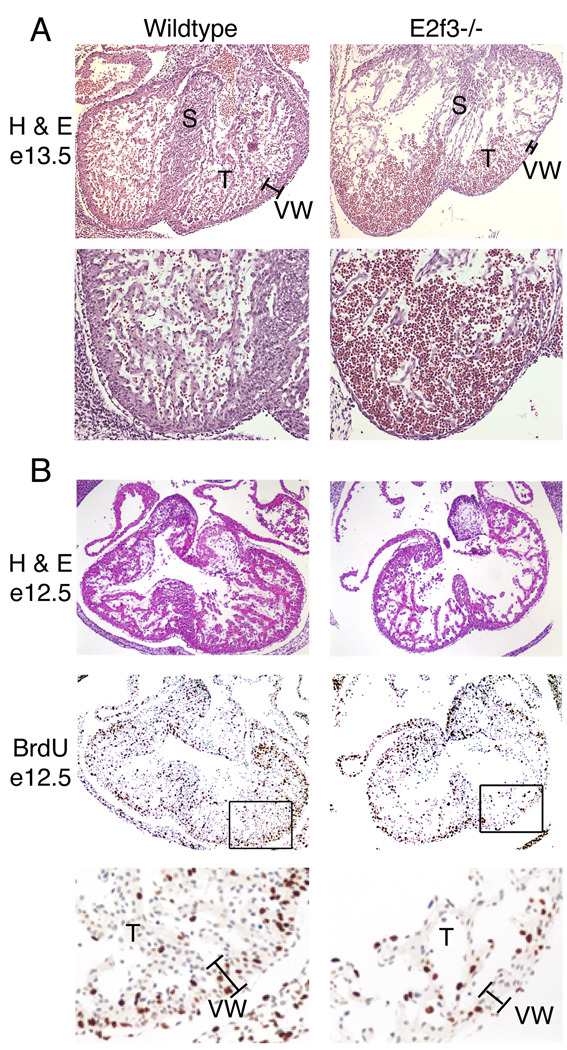

To test our hypothesis, we first examined the consequences of E2F3-deficiency on embryonic heart development. For this analysis, we compared matching serial sections from wildtype and E2f3−/− littermates in the pure 129/sv genetic background, where the E2f3 mutant phenotype is most severe. At embryonic day 13.5 (e13.5), a significant fraction of the E2f3−/− embryos had severely hypoplastic right and left ventricular walls, hypoplastic septa, and a reduction in the amount of trabeculation (Figure 1A). Consistent with the large window of lethality of 129/sv E2f3−/− embryos (e12.5 – e18.5) 16, there was considerable variation in the degree of this defect. In the most extreme cases, the E2f3−/− ventricular wall myocardium was reduced to a single cell layer compared to the six cell layer present in the controls also, blood pooling within the ventricle was observed consistent with impaired heart function (Figure 1A). In other animals, the ventricular walls were clearly hypoplastic but less severely affected, while yet others looked more like the wildtype controls (data not shown).

Figure 1. Proliferation defects in hearts of E2f3−/− mice in utero.

(A) Hematoxylin and eosin stained sections of e13.5 wildtype and E2f3−/− hearts at 100X (top) and 200X (bottom) magnification. VW, ventricular wall. S, septum. T, trabeculae. (B) Hematoxylin and eosin staining (top, 100X magnification) and BrdU immunhistochemistry (middle 100X, bottom 200X) on serial sections of e12.5 hearts. Experiments were performed in the pure 129/sv background where the phenotype is completely penetrant.

To determine whether the observed structural defects were related to alterations in proliferative capacity, we measured cell proliferation by injecting females from 129/Sv E2f3+/− intercrosses with BrdU one hour prior to harvesting e12.5 embryos. The percentage of cycling cells in the myocardium was considerably lower in some of the E2f3−/− embryos (26.1% vs. 41.5%, Figure 1B). Importantly, the degree of this defect varied considerably from one animal to the next, correlating well with both the degree of hypoplasia and the large window of lethality in the animals. Furthermore, TUNEL assays showed no change in the level of apoptosis in the E2f3−/− embryos (data not shown). We therefore conclude that E2F3 is essential for the proliferation of the embryonic myocardium and thus cardiac development during embryogenesis.

E2F3 is critical for Morphogenesis and Hypertrophic Growth During Heart Development

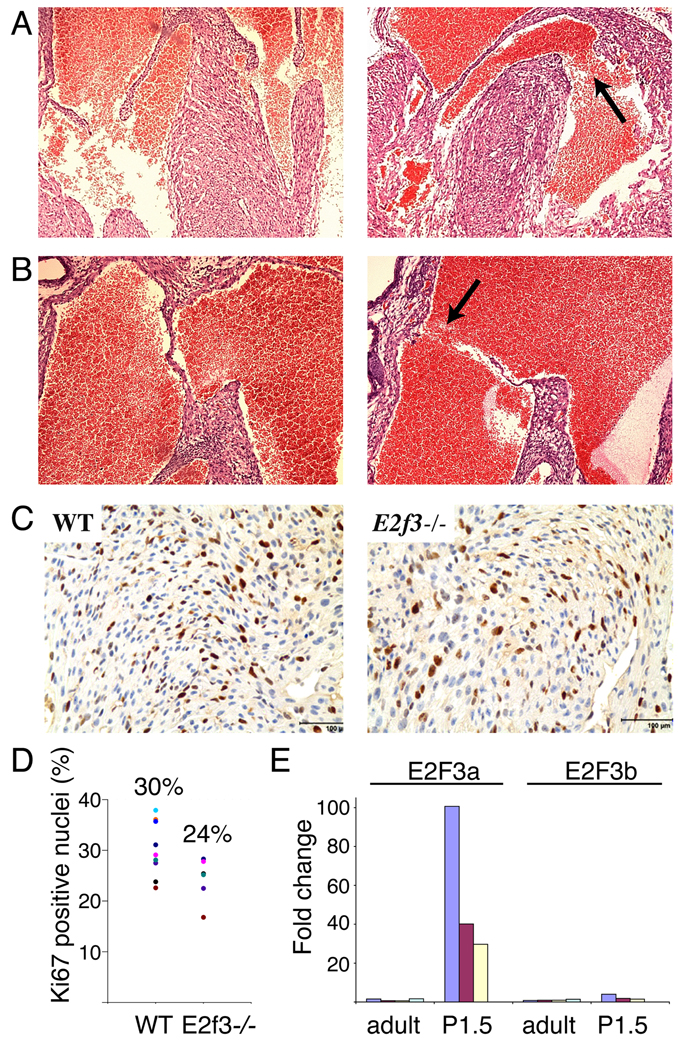

Given the embryonic phenotype, we wished to determine whether defects in cardiac development might also account for the partial perinatal lethality of E2f3−/− mice that we have observed in the mixed (129/sv x C57BL/6) genetic background. To address this issue, we collected three viable and eight non-viable E2f3−/− neonates on postnatal day 1.5 along with wild-type littermate controls and performed a blind screen of serial histological sections for evidence of any structural abnormalities. Upon decoding, we found that the viable and non-viable E2f3−/− animals could be segregated on the basis of structural defects with 100% predictive accuracy. Every one of the inviable E2f3−/− neonates had significant structural atrial and/or ventricular septal defects. 7/8 inviable E2f3−/− mice displayed ventricular septal defects (VSDs), with 5/7 demonstrating high muscular VSDs adjacent to the membranous septum (Figure 2A) and 1/7 demonstrating an inlet muscular VSD (data not shown). 6/8 inviable E2f3−/− animals displayed atrial septal defects (ASDs; Figure 2B). Hypoplasia of the septum primum was observed in each case and hypoplasia of the cristea terminalis (the muscular infolding between the two atria) was also seen in 2/6, resulting in very large atrial septal defects. The presence of hypoplastic atrial and ventricular septa in the non-viable E2f3−/− neonates clearly implicates E2F3 in expansion of myocardium.

Figure 2. Loss of E2f3 causes structural defects in the developing heart.

(A–B) Ventricular (A) and atrial (B) septal defects are present in E2f3−/− (right) but not control (left) neonates (100X). Arrows point to the septal defects. (C–D) Quantitation of cycling cells by Ki67 staining in E2f3−/− and control heart muscle. Dark brown stain indicates Ki67 positive nuclei. The remaining nuclei are counterstained with blue hematoxylin. Numbers above the graph represent the average percentage. (E) Real time RT-PCR analysis of E2f3a and E2f3b transcripts in adult (n=4) and day 1.5 (n=3) ventricular heart tissue. Fold change = 2ˆ(ΔΔCt).

In contrast to the unviable cohort, the surviving day 1.5 E2f3−/− neonates all had grossly normal heart morphology. Since this is a critical timepoint for the cardiac myocytes to undergo hypertrophic growth, we used these sections to determine whether E2F3 contributes to this process. The production of binucleate cells in the hypertrophic growth phase is dependent upon cell cycle re-entry and the activation of DNA replication. We therefore used immunohistochemical staining to screen wild-type versus viable E2f3−/− neonatal hearts for the proliferation markers Ki67 and PCNA (Figure 2C, 2D, data not shown). In each case, the percentage of cycling cells in the E2f3−/− ventricular myocardium was reduced compared with that observed in littermate controls. While this difference does not quite reach statistical significance, it is important to note that we could only to examine the fraction of E2f3−/− animals that survive and therefore have the weakest heart phenotype. These data suggest that E2F3 plays a key role in triggering the cell cycle entry required for neonatal hypertrophic growth.

Previous studies have shown that E2f3 mRNA is present in the proliferating embryonic heart 19, but its expression patterns during the neonatal period have not been examined. Using real time RT-PCR, we screened for the presence of the two E2f3 mRNAs in the postnatal ventricular cardiac tissue (Figure 2E). The E2f3b transcript was detected at a consistently low level, however we observed a significant increase in E2f3a mRNA levels during the hypertrophic growth phase. These observations are consistent with previous findings that E2f3b is ubiquitously expressed while E2f3a is specifically expressed in cells undergoing DNA replication and that E2f3a makes a greater contribution to the E2f3 mutant phenotype that E2f3b 8, 13, 14. Taken together, the induction of E2f3a expression in the wild-type neonates and the cell cycle defect in the viable E2f3−/− neonates suggest that E2F3 activity plays a critical role in hypertrophic growth of the cardiomyocyte.

E2F3-Loss Disrupts the Structure and Function of the Adult Myocardium

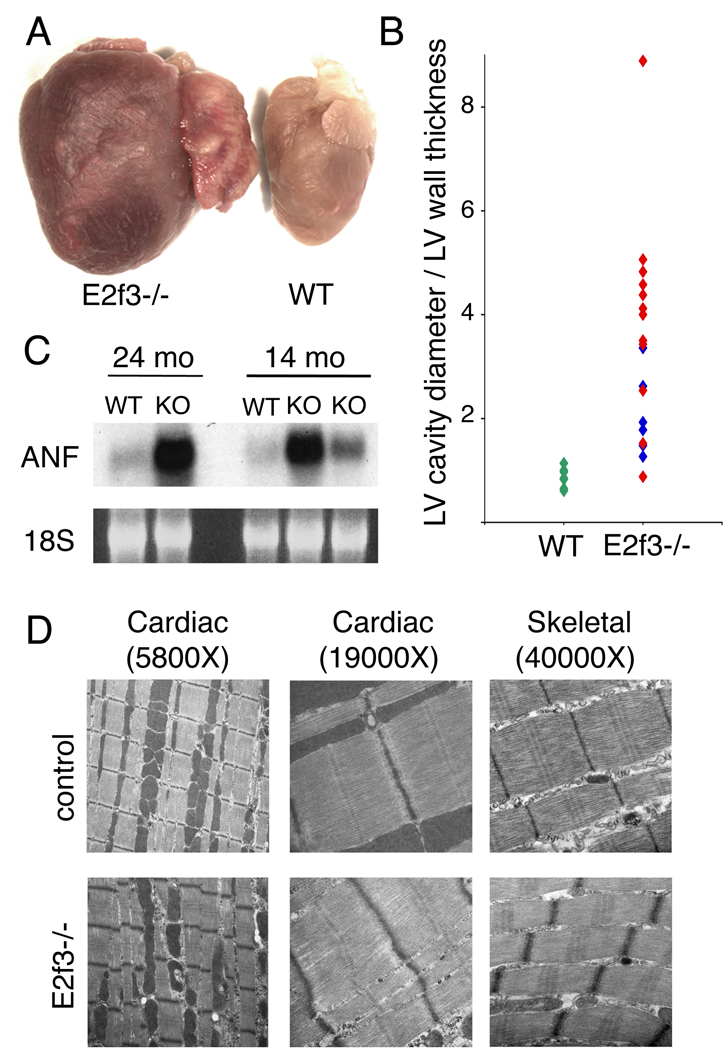

The E2f3−/− mice that survived the perinatal period developed late-onset congestive heart failure with high penetrance. We therefore placed considerable emphasis on characterizing this defect. Autopsy revealed that the hearts of E2f3−/− adults were greatly enlarged and displayed both biventricular and biatrial dilation, often with large atrial thrombi (Figure 3A, 3B). The dilation was greatest in animals that had died from congestive heart failure, and was accompanied by edema in the chest cavity, but dilated hearts were also observed in sacrificed E2f3−/− adults. A molecular marker of cardiac failure, atrial natriuretic factor (ANF), was up-regulated both in sick E2f3−/− adults and in younger, apparently healthy animals (Figure 3C). Other assays provided little additional insight into the physiological changes that lead to the congestive heart failure. There was no significant difference in the systolic blood pressure of wild-type (111.8 ± 8.5 for controls, n=4) versus E2f3−/− (106.4 ± 7.2, n=4) mice, as judged by tail cuff measurements. Two lead EKG analysis of six month old animals provided no evidence for a primary conduction defect in the E2f3−/− mice (data not shown). Finally, echocardiography on E2f3−/− mice greater than 1 year of age found that only 2/12 animals had significant left ventricular contraction defects (fractional shortening of 37% and 39% versus >50% in controls) and one of these animals had an accompanying electrical conduction defect (data not shown). Based on these data, it appears that left ventricular dysfunction arises only shortly before the death of the E2f3−/− animals.

Figure 3. E2f3−/− mice develop congestive heart failure.

(A) Whole mount pictures of hearts from E2f3−/− mice and a wildtype littermate which were sacrificed at 15 months of age. (B) Cardiac dilation of E2f3−/− animals measured by left ventricular cavity diameter/left ventricular wall thickness from histology sections. Red diamonds indicate mice that died from congestive heart failure and blue diamonds indicate mice that were sacrificed while still healthy. (C) Northern blot analysis for ANF on total RNA prepared from ventricular tissue of littermate animals at 14 or 24 months of age. (D) Electron micrographs of muscular ultrastructure from 3.5 month old (cardiac) and 15.5 month old (skeletal) E2f3−/− animals and 19 month old (cardiac) and 15.5 month old (skeletal) controls.

Our embryonic and neonatal studies show that E2F3 contributes to the developing myocardium in both the proliferative and hypertrophic growth phases. Given these observations, we performed a blind comparison of wild-type and E2f3−/− hearts by electron microscopy (EM) to screen for ultrastructural heart muscle defects. Analysis of 19 month old animals detected myofiber disarray and disorganization of the sarcomeres as well as misshapen mitochondria within the E2f3−/− hearts. In particular, the E2f3−/− sections had disorganized Z-disks showing punctate changes, broadening, and loss of the distinct adjacent thin-filament zone. Significantly, these ultrastructural abnormalities were also evident at 3.5 months of age (Figure 3D) indicating that the heart defect is established in the E2f3−/− animals long before their death. Based on these observations, it is formally possible that these ultrastructural defects arise as a secondary consequence of mechanical stress that is caused by some other cardiac defect. However, we also observed broadened, disorganized Z-disks in the skeletal muscle in older E2f3−/− animals (Figure 3D). Thus E2F3-loss affects sarcomere structure in both cardiac and skeletal muscle. Given these findings, we conclude that E2F3 is essential for normal muscle ultrastructure and that its disruption leads to cardiac dysfunction and failure.

Discussion

Taken together, our data indicate that E2F3 plays a key role in cardiac development and function that appears to fully account for the lethality of the E2f3−/− mice. In the embryonic heart, E2F3 loss clearly causes a reduction in myocardial proliferation that results in a thin ventricular septum, thin ventricular walls, and decreased trabeculation. Significantly, a number of mutant mouse strains including N-myc 20, 21, cyclin E 22 and EGF receptor family members 23, 24 show a similar link between reduced cardiomyocyte proliferation and defects in embryonic heart development. These proliferation-related mouse models have defects in the growth of the atrial and ventricular septa and they all die in utero. In contrast, the window of lethality of the E2f3−/− animals is much larger: some animals display embryonic lethality but almost half die perinatally with atrial and/or ventricular septal defects that resulted from myocardial hypoplasia. Human studies have shown that a variety of the transcription factors involved in cardiac differentiation, such as Nkx2.5, Tbx5 and Gata4, are linked to congenital atrial and ventricular septal defects 25. Our analysis of the E2f3−/− mice provides more evidence that proliferation regulators can play a role in congenital heart disease.

In addition to proliferative growth, the observed correlation between upregulation of E2f3a mRNA and the fraction of cycling cells in day 1.5 hearts indicates that E2F3 also contributes to the hypertrophic growth of the myocardium during the neonatal period. Since no cardiac defects were detected in E2f3a mutant mice, E2F3b along with other members of the E2F family must be able to accomplish the functions of total E2f3 activity in the absence of E2f3a 13, 14. Supporting this model, studies in skeletal muscle shows that activating E2F family members also control myoblast hypertrophy through the regulation of a distinct subset of E2F target genes 26. E2F3 is thus required for the two distinct phases of cardiomyocyte development, hyperplastic and hypertrophic growth. There is considerable evidence to suggest that this key role reflects the concerted action of the Rb/E2F pathway. The window of lethality of the E2f3−/− embryos is shifted to either earlier or later time-points by the mutation of E2f1 (a close relative of E2f3a) or Rb (a negative regulator of E2F1 and E2F3a) respectively 16, 27. The hypertrophic growth of cultured rat neonatal cardiomyocytes correlates with the induction of multiple E2F proteins and can be impaired by a pan-E2F inhibitor 28. In addition, in vitro, ectopic expression of E2Fs can induce S-phase entry in cardiomyocytes 29–31. Finally, embryos deficient for cyclin E (a positive regulator and downstream target of E2F3) or all of the D-type cyclins (upstream regulators of the Rb/E2F pathway) also display thin myocardial walls and/or embryonic atrial and ventricular septal defects 22, 32. Taken together, all of these findings suggest that the Rb/E2F pathway is critical for multiple stages of heart growth and development.

The small fraction of E2f3−/− mice that escape the embryonic and perinatal heart problems, develop late onset congestive heart failure with high penetrance. This finding was highly unexpected because analysis of both human patients and mouse models has consistently linked congestive heart failure to mutations within genes that regulate blood pressure, electrical conduction, muscle contraction or cell survival 33, 34. We cannot rule out the possibility that the requirement for E2F3 in this setting reflects a currently unrecognized, non-proliferative role. However, in an analogous manner to the embryonic defects, we have shown that the congestive heart failure in adult E2f3 mutant mice is either increased or completely suppressed by the mutation of E2f1 or Rb (a single allele) respectively indicating that this is influenced by the Rb/E2F pathway 16. Given this finding, E2F3’s role in adult cardiac function likely reflects its proliferation function.

The underlying physiological cause of the heart failure is not entirely clear, but the observed disorganization of the Z-disks in the skeletal, as well as cardiac, muscle argues for a primary defect in muscle function. We envisage that this could arise through four possible mechanisms. Given E2F3’s key role in both hyperplastic and hypertrophic growth, it seems highly plausible that a reduction in cardiomyocyte proliferation or ability to enter the cell cycle during the embryonic and/or neonatal period could lead to a subtle defect in the myocardium that does not manifest its effects until adulthood. This model is directly supported by our ability to detect ultrastructural abnormalities in E2f3−/− hearts well before the time of death. Although we favor this hypothesis, it entirely possible that the congestive heart failure reflects a role for E2F3 in the hypertrophic growth response that occurs in adult cardiomyocytes in response to stress 35. In this scenario, the heart could have an underlying weakness such that its inability to respond to stress would initiate the ventricular dysfunction. Interestingly, loss of E2F3 impairs the proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells that occurs following blood vessel injury indicating that E2F3 activity is important for muscle cell proliferation in adult animals 36. Thirdly, while most investigators believe that the adult heart is non-proliferative, there is some support for the existence of a small population of cycling adult cardiomyocytes 37, 38. If this notion is correct, E2F3-loss might adversely affect these stem cell-like progenitors. In support of this idea, one group demonstrated that E2F loss compromised skeletal muscle regeneration due to the inability of the muscle precursors to proliferate 39. Finally, we are open minded to the possibility that the loss of E2F3 disrupts placental function and influences heart development via an non cell-autonomous mechanism. This possibility is supported by two observations: firstly, mutations of other genes exclusively in the placenta for example, PPARγ 40 or p38α 41 or other disruptions in placental function 42 clearly can result in heart defects. Mutation of E2f3 largely suppresses the placental defects that are responsible for the early embryonic lethality of pRb mutant embryos 43 indicating that E2f3 does play a role in the placenta however, no placental phenotype in E2f3 mutant embryos has been described so whether loss of E2F3 function in the placenta is important for the heart defects remains to be formally proven. Secondly, chimeric mice generated from E2f3 mutant embryonic stem cells do not exhibit cardiac defects 44. In chimeric embryos the embryonic stem cells do not contribute significantly to extraembryonic tissues, such as the placenta, indicating that mutation of E2f3 in the placenta may contribute to the heart defects. In these E2f3 mutant chimeric mice, however, we cannot rule out that a small percentage of wild-type cells may be sufficient to prevent the heart defects.

Regardless of the mechanism of the adult phenotype, this study provides strong evidence implicating a proliferation regulator in three different stages of cardiac disease. Whether genetic lesions or polymorphisms in E2F3, or other key components of the pRB/E2F pathway, are responsible for a subset of cases of human congestive heart failure or congenital heart disease remains a subject for further investigation.

Materials and Methods

Animal Maintenance, Histology, and Immunohistochemistry

The E2f3 mutant mouse strains were genotyped using common primer 5’-GTCCCCACTAACGTGAACTTACG-3’, E2F3 primer 5’-AGTGCAGCTCTTCCTTTGCCTTG-3’, and targeting construct primer 5’-GCTCATTCCTCCCACTCATGATC-3’ as described previously 15. All animal procedures were approved by the Institute’s Committee on Animal Care. Timed pregnancies were established detection of vaginal plugs (e 0.5), embryos were harvested by caesarean section, and viability was assessed by heartbeat detection. Embryos and tissues were fixed overnight in 10% formalin or 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, embedded in paraffin blocks and 5 µm sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. For immunohistochemistry, primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4°C and ABC kits (Vector, Burlingame, CA) were used for secondary antibodies and detection. Antigen demasking was performed by incubating slides twice for 5 minutes in boiling .01M sodium citrate, pH 6.0 (for Ki67 staining) or sequentially with 0.2µg/µl pepsin in .01M HCl for 10 minutes and then 2M HCl for 45 minutes (for BrdU staining). The antibody for Ki67 staining was NCL-L-Ki67-MM1 (Novocastra/Vector, Burlingame, CA) at 1:200 dilution, for PCNA was 13–3490 (Zymed, S. San Francisco, CA) at 1:20, and for BrdU was MD5215 (Caltag, Burlingame, CA) at 1:50.

RNA Analysis

Total RNA was prepared from ventricular mouse tissue using Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen, Burlingame, CA). Northern blots were performed as previously described 15. For RT-PCR, the RNA was further purified using the RNAEasy clean up protocol with an on-column DNase step, following the manufacturer’s directions (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Adult RNA samples (n=4) were made from ventricular tissue of a wildtype adult heart and day 1.5 samples (n=3) were each made from ventricular tissue of 2 pooled wildtype littermate animals. Reverse transcription reactions were performed with Superscript First Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen, Burlingame, CA). Real time PCR reactions using SYBR Green dye (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) were run in triplicate on an ABI Prism 7000 real time PCR machine (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). ΔCt values were calculated by normalizing cycle threshold values to control eukaryotic18S rRNA reactions (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), also run in triplicate. Fold change was calculated as 2ˆ(ΔΔCt) where ΔΔCt = ΔCt(sample) – (average ΔCt of adult samples). Primer sequences for E2f3a were 5’-GTGGCCCACCGGCAA-3’ and 5’-ACCATCTGAGAGGTACTGATGGC-3’ and for E2f3b were 5’-TGCTTTCGGAAATGCCCTTA-3’ and 5’-CCAGTTCCAGCCTTCGCTT-3’.

Electron Microscopy

Tissue was processed for electron microscopy at room temperature using a standard procedure, as described below. Samples were originally fixed in 10% formalin and then small fragments of tissue were re-fixed in Karnovskys's half strength glutaraldehyde/paraformaldehyde mixture (2.5g/dl glutaraldehyde; 2g/dl paraformaldehyde) in 0.1M sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.4. Following a brief rinse (3× 5 minutes) in 5g/dl sucrose in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.4, the tissue was post-fixed in osmium-S-collidine solution (1.33g/dl osmium tetroxide in 0.066M S-collidine buffer, pH 7.4) for 2 hours. The tissue was then dehydrated in graded ethyl alcohol solutions (70% for 10 minutes; 80% for 10 minutes; 95% for 15 minutes; 100% 3 changes for 20 minutes each). The tissue was cleared in propylene oxide (2 changes, 30 minutes each) and infiltrated first in a 1:1 mixture (by volume) of propylene oxide and poly-Bed mixture for 60 minutes followed by infiltration in undiluted poly-bed for 30 minutes. The tissue blocks were then placed in plastic molds filled with poly-Bed and cured overnight at 60°C. 1 µm sections were stained on a hot plate with alkaline toluidine blue (1g/dl toluidine blue solution and 1g/dl borax). Ultra thin sections with silver to light golden interference color were cut on an ultra-microtome, picked up on 200 mesh copper grids, and stained on the grid with saturated uranyl acetate solution for 15 minutes and 0.1 to 0.4 g/dl of lead citrate for 45 seconds. The grids were then examined in a Jeol JEM 1010 electron microscope at 80KV acceleration voltage. Images were recorded with an AMT digital camera.

Acknowledgements

We thank Robb MacLellan for providing the ANF plasmid and Alejandro Sweet-Cordero and Han You for their advice in establishing the real time PCR techniques. We are grateful to Michael Yaffe, Paul Danielian and members of the Lees lab for helpful discussions during this study and the preparation of this manuscript. J.E.C. was supported by a David Koch predoctoral fellowship. I.M. was supported by a post-doctoral training grant from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. J.A.L. is a Daniel K. Ludwig Scholar. This work was supported by grants from the NIH (PO1-CA42063) to J.A.L.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Attwooll C, Lazzerini Denchi E, Helin K. The E2F family: specific functions and overlapping interests. Embo J. 2004;23:4709–4716. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dimova DK, Dyson NJ. The E2F transcriptional network: old acquaintances with new faces. Oncogene. 2005;24:2810–2826. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trimarchi JM, Lees JA. Sibling rivalry in the E2F family. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:11–20. doi: 10.1038/nrm714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blais A, Dynlacht BD. E2F-associated chromatin modifiers and cell cycle control. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19:658–662. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adams MR, Sears R, Nuckolls F, Leone G, Nevins JR. Complex transcriptional regulatory mechanisms control expression of the E2F3 locus. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:3633–3639. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.10.3633-3639.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He Y, Armanious MK, Thomas MJ, Cress WD. Identification of E2F-3B, an alternative form of E2F-3 lacking a conserved N-terminal region. Oncogene. 2000;19:3422–3433. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leone G, Nuckolls F, Ishida S, Adams M, Sears R, Jakoi L, Miron A, Nevins JR. Identification of a novel E2F3 product suggests a mechanism for determining specificity of repression by Rb proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:3626–3632. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.10.3626-3632.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lukas J, Petersen BO, Holm K, Bartek J, Helin K. Deregulated expression of E2F family members induces S-phase entry and overcomes p16INK4A-mediated growth suppression. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1047–1057. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.3.1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson DG, Schwarz JK, Cress WD, Nevins JR. Expression of transcription factor E2F1 induces quiescent cells to enter S phase. Nature. 1993;365:349–352. doi: 10.1038/365349a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lees JA, Saito M, Vidal M, Valentine M, Look T, Harlow E, Dyson N, Helin K. The retinoblastoma protein binds to a family of E2F transcription factors. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:7813–7825. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.12.7813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takahashi Y, Rayman JB, Dynlacht BD. Analysis of promoter binding by the E2F and pRB families in vivo: distinct E2F proteins mediate activation and repression. Genes Dev. 2000;14:804–816. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Danielian PS, Friesenhahn LB, Faust AM, West JC, Caron AM, Bronson RT, Lees JA. E2f3a and E2f3b make overlapping but different contributions to total E2f3 activity. Oncogene. 2008 doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsai SY, Opavsky R, Sharma N, Wu L, Naidu S, Nolan E, Feria-Arias E, Timmers C, Opavska J, de Bruin A, Chong JL, Trikha P, Fernandez SA, Stromberg P, Rosol TJ, Leone G. Mouse development with a single E2F activator. Nature. 2008;454:1137–1141. doi: 10.1038/nature07066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Humbert PO, Verona R, Trimarchi JM, Rogers C, Dandapani S, Lees JA. E2f3 is critical for normal cellular proliferation. Genes Dev. 2000;14:690–703. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cloud JE, Rogers C, Reza TL, Ziebold U, Stone JR, Picard MH, Caron AM, Bronson RT, Lees JA. Mutant mouse models reveal the relative roles of E2F1 and E2F3 in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:2663–2672. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.8.2663-2672.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacLellan WR, Schneider MD. Genetic dissection of cardiac growth control pathways. Annu Rev Physiol. 2000;62:289–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.62.1.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pasumarthi KB, Field LJ. Cardiomyocyte cell cycle regulation. Circ Res. 2002;90:1044–1054. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000020201.44772.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dagnino L, Fry CJ, Bartley SM, Farnham P, Gallie BL, Phillips RA. Expression patterns of the E2F family of transcription factors during murine epithelial development. Cell Growth Differ. 1997;8:553–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charron J, Malynn BA, Fisher P, Stewart V, Jeannotte L, Goff SP, Robertson EJ, Alt FW. Embryonic lethality in mice homozygous for a targeted disruption of the N-myc gene. Genes Dev. 1992;6:2248–2257. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.12a.2248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moens CB, Stanton BR, Parada LF, Rossant J. Defects in heart and lung development in compound heterozygotes for two different targeted mutations at the N-myc locus. Development. 1993;119:485–499. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.2.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geng Y, Yu Q, Sicinska E, Das M, Schneider JE, Bhattacharya S, Rideout WM, Bronson RT, Gardner H, Sicinski P. Cyclin E ablation in the mouse. Cell. 2003;114:431–443. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00645-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gassmann M, Casagranda F, Orioli D, Simon H, Lai C, Klein R, Lemke G. Aberrant neural and cardiac development in mice lacking the ErbB4 neuregulin receptor. Nature. 1995;378:390–394. doi: 10.1038/378390a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee KF, Simon H, Chen H, Bates B, Hung MC, Hauser C. Requirement for neuregulin receptor erbB2 in neural and cardiac development. Nature. 1995;378:394–398. doi: 10.1038/378394a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olson EN. Gene regulatory networks in the evolution and development of the heart. Science. 2006;313:1922–1927. doi: 10.1126/science.1132292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hlaing M, Spitz P, Padmanabhan K, Cabezas B, Barker CS, Bernstein HS. E2F-1 regulates the expression of a subset of target genes during skeletal myoblast hypertrophy. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:43625–43633. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408391200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ziebold U, Reza T, Caron A, Lees JA. E2F3 contributes both to the inappropriate proliferation and to the apoptosis arising in Rb mutant embryos. Genes Dev. 2001;15:386–391. doi: 10.1101/gad.858801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vara D, Bicknell KA, Coxon CH, Brooks G. Inhibition of E2F abrogates the development of cardiac myocyte hypertrophy. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:21388–21394. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212612200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agah R, Kirshenbaum LA, Abdellatif M, Truong LD, Chakraborty S, Michael LH, Schneider MD. Adenoviral delivery of E2F-1 directs cell cycle reentry and p53-independent apoptosis in postmitotic adult myocardium in vivo. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2722–2728. doi: 10.1172/JCI119817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.von Harsdorf R, Hauck L, Mehrhof F, Wegenka U, Cardoso MC, Dietz R. E2F-1 overexpression in cardiomyocytes induces downregulation of p21CIP1 and p27KIP1 and release of active cyclin-dependent kinases in the presence of insulin-like growth factor I. Circ Res. 1999;85:128–136. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.2.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ebelt H, Liu Z, Muller-Werdan U, Werdan K, Braun T. Making omelets without breaking eggs: E2F-mediated induction of cardiomyoycte cell proliferation without stimulation of apoptosis. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:2436–2439. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.21.3402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kozar K, Ciemerych MA, Rebel VI, Shigematsu H, Zagozdzon A, Sicinska E, Geng Y, Yu Q, Bhattacharya S, Bronson RT, Akashi K, Sicinski P. Mouse development and cell proliferation in the absence of D-cyclins. Cell. 2004;118:477–491. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chien KR. Genomic circuits and the integrative biology of cardiac diseases. Nature. 2000;407:227–232. doi: 10.1038/35025196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chien KR. Genotype, phenotype: upstairs, downstairs in the family of cardiomyopathies. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:175–178. doi: 10.1172/JCI17612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frey N, Olson EN. CARDIAC HYPERTROPHY: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Annu Rev Physiol. 2003;65:45–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Giangrande PH, Zhang J, Tanner A, Eckhart AD, Rempel RE, Andrechek ER, Layzer JM, Keys JR, Hagen PO, Nevins JR, Koch WJ, Sullenger BA. Distinct roles of E2F proteins in vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and intimal hyperplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:12988–12993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704754104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anversa P, Leri A, Kajstura J, Nadal-Ginard B. Myocyte growth and cardiac repair. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34:91–105. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nadal-Ginard B, Kajstura J, Leri A, Anversa P. Myocyte death, growth, and regeneration in cardiac hypertrophy and failure. Circ Res. 2003;92:139–150. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000053618.86362.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yan Z, Choi S, Liu X, Zhang M, Schageman JJ, Lee SY, Hart R, Lin L, Thurmond FA, Williams RS. Highly Coordinated Gene Regulation in Mouse Skeletal Muscle Regeneration. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8826–8836. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209879200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barak Y, Nelson MC, Ong ES, Jones YZ, Ruiz-Lozano P, Chien KR, Koder A, Evans RM. PPAR gamma is required for placental, cardiac, and adipose tissue development. Mol Cell. 1999;4:585–595. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80209-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adams RH, Porras A, Alonso G, Jones M, Vintersten K, Panelli S, Valladares A, Perez L, Klein R, Nebreda AR. Essential role of p38alpha MAP kinase in placental but not embryonic cardiovascular development. Mol Cell. 2000;6:109–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jansson T, Powell TL. Role of the placenta in fetal programming: underlying mechanisms and potential interventional approaches. Clin Sci (Lond) 2007;113:1–13. doi: 10.1042/CS20060339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wenzel PL, Wu L, de Bruin A, Chong JL, Chen WY, Dureska G, Sites E, Pan T, Sharma A, Huang K, Ridgway R, Mosaliganti K, Sharp R, Machiraju R, Saltz J, Yamamoto H, Cross JC, Robinson ML, Leone G. Rb is critical in a mammalian tissue stem cell population. Genes Dev. 2007;21:85–97. doi: 10.1101/gad.1485307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parisi T, Yuan TL, Faust AM, Caron AM, Bronson R, Lees JA. Selective requirements for E2f3 in the development and tumorigenicity of Rb-deficient chimeric tissues. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:2283–2293. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01854-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]