Abstract

Objectives

We sought to promote myocardial repair using urinary bladder matrix (UBM) incorporated with a fusion protein which combined hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and fibronectin collagen-binding-domain (CBD) in a porcine model. CBD acted as an intermediary to promote HGF binding and enhance HGF stability within UBM.

Methods

UBM incorporated with CBD-HGF was implanted into the porcine right ventricular wall (F-group) to repair a surgically created defect. Untreated UBM patches (U-group) and Dacron patches (D-group) served as controls (N=5/group). Electromechanical mapping was performed at 60-days after surgery. Linear local shortening (LLS) was used to assess regional contractility, and electrical activity was recorded.

Results

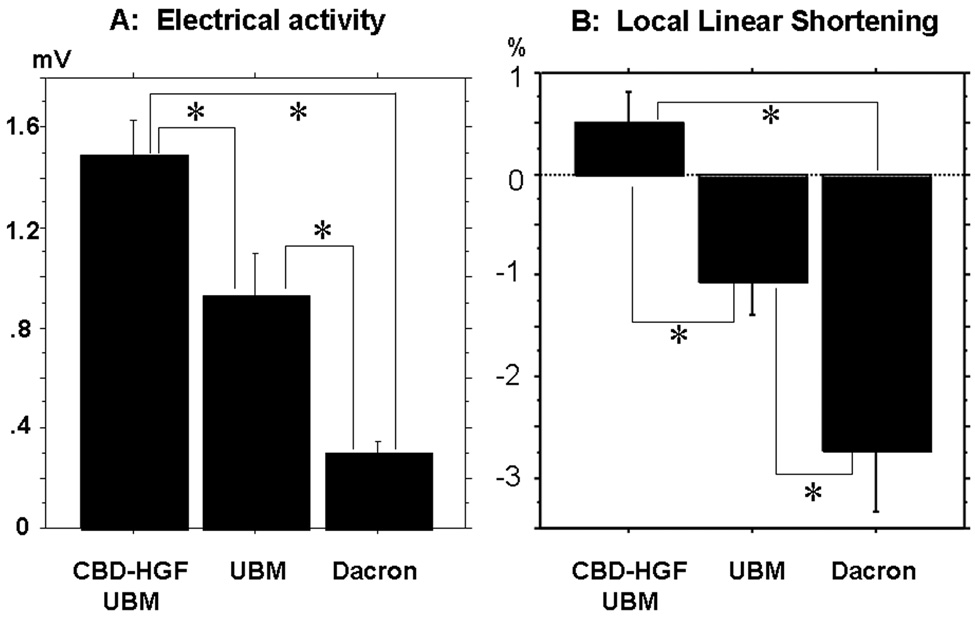

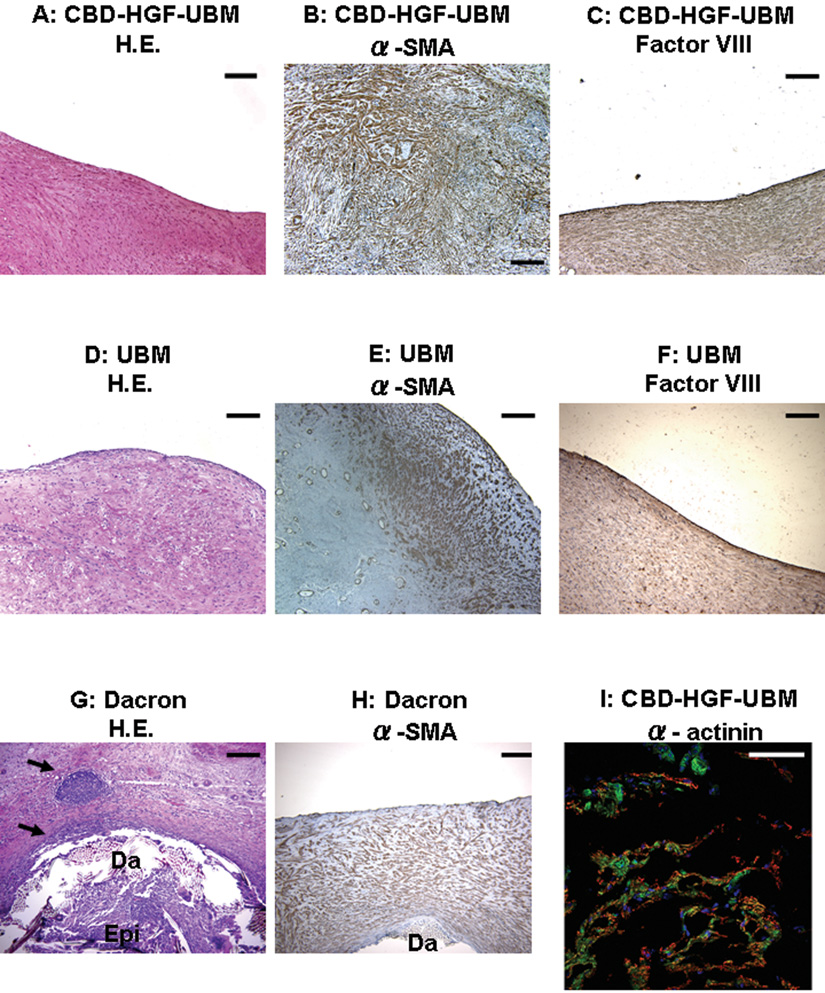

The LLS was significantly improved in the F group compared with controls (F:0.51 ± 1.57%*, U:− 1.06 ± 1.84%, D: −2.72 ± 2.59%; *p<0.05), while they were inferior to the normal myocardium(13.7 ± 4.3%)*. Mean electrical activity was 1.49±0.82mV in the F group, which was statistically greater than control groups (U:0.93 ± 0.71mV; D:0.30 ± 0.22mV)* and less than the normal myocardium (8.24±2.49mV)*. Histological examination showed predominant α-smooth muscle actin positive cells with the F group showing the thickest layer and the D group the thinnest layer, with an endocardial endothelial monolayer. Scattered isolated islands of α-actinin positive cells were observed only in the F group, but not in the controls, suggesting the presence of cardiomyocytes.

Conclusions

The CBD-HGF-UBM patch demonstrated increased contractility and electrical activity compared to UBM alone or Dacron, and facilitated a homogeneous repopulation of host cells. UBM incorporated with CBD-HGF may contribute to constructive myocardial remodeling.

Introduction

Biologic scaffold materials derived from naturally occurring extracellular matrix (ECM) have shown the ability to promote site-specific, constructive remodeling in a variety of body systems in both pre-clinical studies and clinical practice1,2. Recently, an ECM scaffold derived from the basement membrane and lamina propria layers of the porcine urinary bladder, referred to as urinary bladder matrix (UBM), was evaluated for repair of myocardial tissue. UBM showed some promise for myocardial repair, with early regeneration of cardiomyocytes and evidence of electrical activity and mechanical function, but was inferior to normal myocardial tissue at 60 days after repair3,4,5. The purpose of the present study was to determine whether the addition of a biologically active factor, specifically hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), may accelerate the remodeling response of injured myocardial tissue.

HGF was chosen for investigation in this model because it possesses a potent mitogenic effect on endothelial cells and stimulates angiogenesis6,7. Urbanek et al. reported that the intra-myocardial injection of HGF facilitated migration and proliferation of c-kit positive cells, which differentiate into small, functional myocytes8. HGF also enhances “cell-to-cell” and “cell-to-ECM” adhesion through activation of a matrix degradation pathway, which facilitates repopulation of tissues with cells9. In addition, HGF has been shown to suppress fibrosis that is characteristic of maladaptive remodeling of infarcted hearts10,11.

The direct addition of HGF to UBM would be expected to yield only transient effects since HGF would likely rapidly elute from the UBM surface. To prolong the presence of HGF in the UBM, a fusion protein combining fibronectin collagen-binding domain (CBD) and HGF was utilized in this study12. CBD has a high affinity exclusively for collagen and gelatin. In a previous study using CBD-HGF, enhanced early endothelialization and site-specific remodeling were observed in a decellularized porcine aortic valve13. We hypothesize here that CBD-HGF will alter the phenotypic profile of cells that populate the remodeled UBM cardiac patch and enhance cardiac function.

Methods

UBM Scaffold Preparation

UBM scaffolds were prepared as described previously3. Briefly, the basement membrane of the tunica epithelialis mucosa and the subjacent tunica propria of the porcine urinary bladder, collectively termed UBM, was mechanically isolated and then decellularized and disinfected by immersion in 0.1% (v/v) peracetic acid, 4% (v/v) ethanol, and 96% (v/v) deionized water for 2 hours. The UBM material was then washed twice for 15 min with PBS (pH=7.4) and twice for 15 minutes with deionized water.

Four hydrated sheets of UBM were stacked in such a manner that the basement membrane surface was the outer most surface on the top and bottom of the stack. This orientation of sheets was chosen to promote endothelial cell growth on the luminal aspect of the scaffold regardless of the orientation of the scaffold14. The four-layer construct was laminated by a vacuum-pressing technique. The construct was placed between two perforated stainless steel sheets, and the stainless steel plates were placed between sheets of sterile gauze. The entire construct was then sealed in vacuum bagging and subjected to a vacuum of 710–730 mmHg for approximately 8 hours. It was finally sterilized by exposure to ethylene oxide. The thickness of each UBM scaffold was approximately 1 mm in the dry form and 1.5 mm in the rehydrated form.

Preparation of CBD-HGF

CBD was fused to the amino terminus of mature HGF with an inserted amino acid sequence using the baculovirus technique, and CBD-HGF was purified as previously described12. The amount of CBD-HGF present was measured by ELISA and expressed as the amount of recombinant HGF (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ).

Incorporation of CBD-HGF and UBM

The incorporation of CBD-HGF to UBM was performed under sterile conditions. CBD-HGF (50µg) was incubated at 37°C for 15 minutes after adding fetal bovine serum (20µl), which transformed single chains of the CBD-HGF into heterodimers (active form). The UBM scaffolds (25×25mm) were rehydrated with saline and then soaked into an activated CBD-HGF solution (1µg/ml; 25ml/patch) for 24 hours at 4°C. Finally, the CBD-HGF solution was decanted, and the patches were rinsed with PBS (50ml/patch) prior to surgery.

Quantitative Determination of HGF

The amount of HGF in preimplant CBD-HGF-UBM patches (N=5) was measured by ELISA (HGF Immunoassay Kit, Biosource, Camarillo, CA) after protein extraction of homogenized patches using a lysis buffer (Tissue Extraction Reagent I, Biosource). rHGF-UBM patches (N=5), which were subjected to the same incorporation process except for the use of recombinant HGF (rHGF, PeproTech) in place of CBD-HGF, and untreated UBM patches (N=5) served as controls.

Cell Proliferation Assay

UBM discs (5mm in diameter, thickness of 0.3mm) were washed with PBS and then placed in wells of 96-well plates (Nunclon, Nalge Nunc International, Denmark). The discs were incubated for 2-hour at 37°C in solutions of CBD-HGF or rHGF (0, 80 or 400ng/disc in PBS). Each scaffold was washed several times. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs, Lonza, Walkersville, MD) were seeded (5000cells/well) and cultured for 7 days in EBM2 medium (Lonza) supplemented with 0.5% serum and IGF but without other angiogenic factors (EGF, FGF-2 and VEGF). Cell number was measured using WST-1 reagent (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan) as previously described12.

Myocardial Repair in a Porcine Model

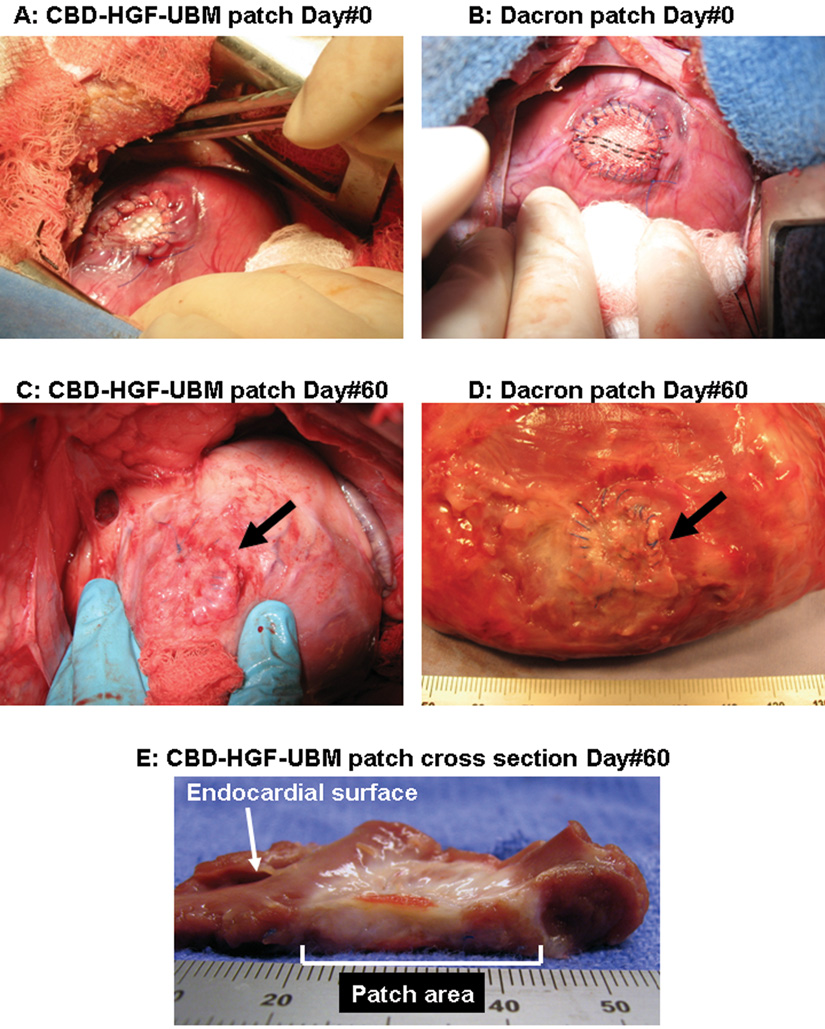

Yorkshire swine (40–50 kg) were anesthetized and placed in a left recumbent position. The pericardiotomy was performed and accordingly the heart was exposed through a right anterolateral thoracotomy in the fourth intercostal space. After the positioning of a tangential clamp on the right ventricle, a small portion in full thickness of the right ventricular (RV) free wall was substituted with a CBD-HGF-UBM patch (25mm in diameter) with a 5-0 continuous polypropylene suture (F group, N=5) (Figure 1A). Routine chest closure was performed. At 60-day after implantation, the animals were subjected to electromechanical mapping, and were euthanized for further examination. Swine similarly receiving untreated UBM (U group, N=5) or Dacron (thickness of 0.76 mm) (D group, N=5) were used as controls (Figure 1B). The 60-day time point was chosen as naturally occurring extracellular matrix was typically degraded by this time15,16.

Figure 1.

A,B: Intraoperative view after implantation (A:CBD-HGF-UBM patch, B:Dacron patch). C: CBD-HGF-UBM patch at 60-day after implantation. The patch is covered with a thin connective tissue with little adhesion. No aneurysm is seen (Arrow). D: Dacron patch at 60-day after implantation (excised heart). A severe adhesion (already removed) and deformity of the patch are observed (Arrow). E: Cross section of CBD-HGF-UBM patch. The thickness of the patch area approaches that of the normal myocardium.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pittsburgh. All animals received humane care in compliance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, published by the National Institutes of Health (1996).

Electromechanical Mapping

Electromechanical mapping was performed with the NOGA mapping system. The system uses synchronous extracorporeal magnetic fields projected into the thoracic space to determine the location and orientation of a sensor mounted near the distal electrode of a deflectable bipolar mapping catheter (NOGA-Star, Biosense Webster Inc., Diamond Bar, CA), which can be used to access the endocardial surface17. An intracardiac echocardiography system (AcuNAV; Acuson Siemens, Mountain View, CA) was use together with NOGA to ensure proper placement of the NOGA-Star catheter. The AcuNAV system consists of a 10F deflectable catheter incorporating a phased-array transducer with programmable operating frequency18,19. Endocardial mapping of the entire endocardial surface was performed during sinus rhythm. The acquired point density for non-free RV walls was 5/cm2; the density for the RV free wall was 10/cm2.

Regional contractility was evaluated by calculating the linear local shortening (LLS) (LLS>9%; normal contractility, 9%>LLS>0%; hypokinetic, 0% >LLS; dyskinetic). The algorithm calculated the fractional shortening of regional endocardial surface at end-systolic phase as previously described20.

Quantitative Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed to quantify the expression of a variety of gene transcripts to have greater insight into the relative presence of various cell types and growth factor expression in the patches at 60-day after implantation (N=5 for each group), using the TaqMan probe and Applied Biosystems 7700 sequence detector system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), as described21. The tissues were taken from the center of the patches and stored in a RNA stabilization reagent (RNAlater, QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). Transcripts that were analyzed included von Willebrand factor (vWF), vascular smooth muscle α-actin 2 (ACTA2), smooth muscle 22α (SM22α), vimentin, beta-myosin heavy chain (MHC), HGF, basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Beta-MHC was chosen because it was expressed in the early phase of cardiac growth as opposed to alpha-MHC, while they were both positive in adult hearts22,23. Results were normalized to the level of porcine glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) transcripts. Relative expression to GAPDH was quantified with standard curves for both a target gene and GAPDH, ranging from 102 to 107 copies, which was created for each sample and each assay. The sequences of the specific primers are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers and Probes for Quantitative Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction

| GAPDH | Forward | 5′-CTGCACCACCAACTGCTTAGC-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GCCATGCCAGTGAGCTTCC-3 | |

| Probe | 5′-CCTGGCCAAGGTCATCCATGACCACTTC-3′ | |

| vWF | Forward | 5′-ATGGAGTACACGGCTTTGCTG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-CAGGCACATGCTGTGACACAT-3′ | |

| Probe | 5′-ATGAATGTCCACCTCCTCTTCAGACCGG-3′ | |

| SM22α | Forward | 5′-GCTCCATTTGCTTGAAGACCAT-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GTAATGCAGTGTGGCCCTGA-3′ | |

| Probe | 5′-CTCAAAATCACGCCGTTCTTCAGCCA-3′ | |

| ACTA2 | Forward | 5′-TATGTGGCTATTCAGGCGGTG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-AGGATCTTCATGAGGTAGTCGGTG-3′ | |

| Probe | 5′-ATGGTGTCACCCACAACGTGCCCATT-3′ | |

| Vimentin | Forward | 5′-AGGTGGCAATCTCAATGTCGA-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-AAATGAGTACCGGAGACAGGTGC-3′ | |

| Probe | 5′-CTCTTCCATTTCCCGCATCTGGCGTT-3′ | |

| MHC | Forward | 5'-CTGAAGGACACCCAGATCCA-3' |

| Reverse | 5'-GTTGATGAGGCTGGTCTGG-3' | |

| Probe | 5'-ACGCGGTCCGTGCCAATGATGACC-3' | |

| HGF | Forward | 5'-ATGATGTCCACGGAAGAGGAGA-3' |

| Reverse | 5'-CACTCGTAATAGGCCATCATAGTTGA-3' | |

| Probe | 5'-TGCAAACAGGTTCTCAATGTTTCCCAGC-3' | |

| bFGF | Forward | 5'-TGTGTGCAAACCGTTATCTTGCTA-3' |

| Reverse | 5'-CAGTGCCACATACCAACTGGAGTA-3' | |

| Probe | 5'-CTACAATACTTACCGGTCGAGG-3' | |

| VEGF | Forward | 5'-GACGTCTACCAGCGCAGCTACT-3' |

| Reverse | 5'-TTTGATCCGCATAATCTGCATG-3' | |

| Probe | 5'-TTCCAGGAGTACCCCGATGAGATCGA-3' |

ACTA2=vascular smooth muscle α-actin 2; bFGF= basic fibroblast growth factor; GAPDH = glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; HGF=hepatocyte growth factor; MHC= beta-myosin heavy chain; SM22α = smooth muscle 22α; VEGF=vascular endothelial growth factor; vWF=von Willebrand factor.

Histology and Immunohistochemistry

Excised tissues were fixed in 10% formalin for paraffin processing or frozen and cut into 5-µm sections. The paraffin sections were deparaffinized and stained with Hematoxylin & Eosin (H&E) or prepared for immunohistochemical staining. Monoclonal antibodies specific for factor VIII–related antigen (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) (Dako) were used. The immunoreaction was detected with 3,3-diaminobenzidine. In addition, cryosections of the tissues were interacted with α-sarcomeric actinin (Sigma) and visualized with fluorescein isothiocyanate labeled secondary antibody, using a confocal microscope to detect cardiomyocytes.

Capillary Density

The factor-VIII positive capillaries were counted under x200 microscopy. Twenty fields were randomly selected in each patch. Capillary density was expressed as the mean number of vessels per square millimeter24.

Statistical Analysis

All values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. The statistical differences in all data were determined by a Mann-Whitney test. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

In Vitro Analyses

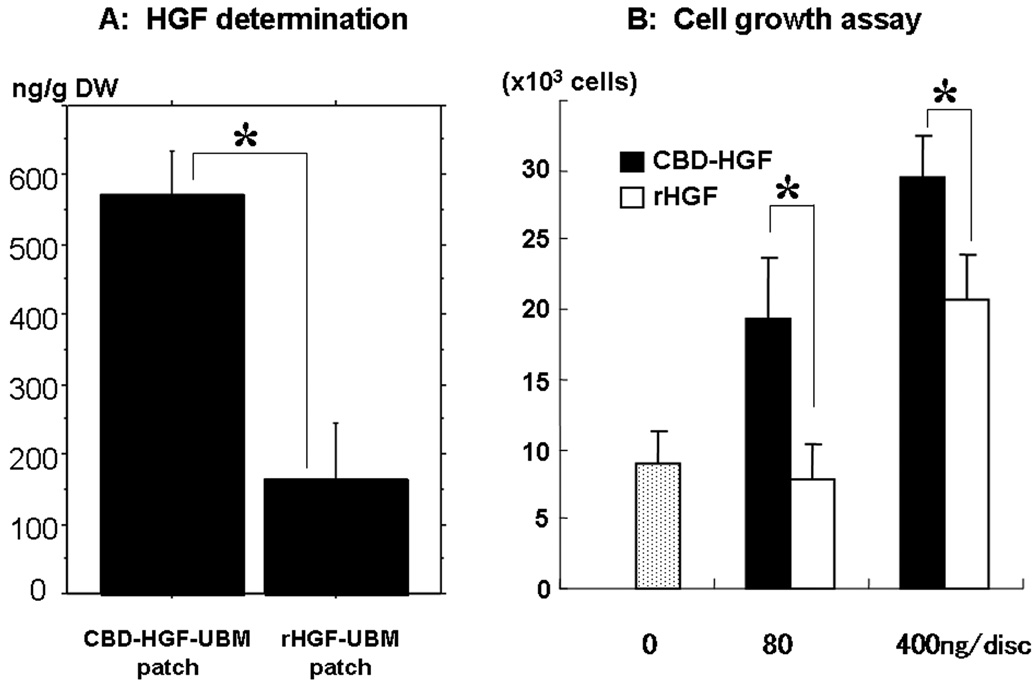

HGF concentration was 571.8±246.7 ng/g dry weight in the CBD-HGF-UBM patches and 163.9 ± 183.3 ng/g dry weight in the rHGF-UBM patches (p<0.05) (Figure 2A). HGF was not detected in the untreated UBM patches.

Figure 2. In-vitro testing.

A: HGF determination in pre-implant patches. The amount of HGF in the CBD-HGF-UBM patch was significantly higher than that of the rHGF-UBM (*p<0.05). (DW; dry weight). B: Growth of Human endothelial cells on UBM discs. CBD-HGF shows significantly greater proliferation potential than HGF in each concentration (*p<0.05).

CBD-HGF treatment of the UBM significantly increased cell proliferation as compared to HGF alone in both 80ng/disc (CBD-HGF 19.3 ± 4.4(×103) cells vs. HGF 7.9 ± 2.4(×103) cells; p<0.05) and 400ng/disc (CBD-HGF 29.5 ± 2.8(×103) cells vs. HGF 20.8 ± 3.2(×103) cells; p<0.05) (Figure 2B). The cell proliferation for UBM treated with HGF alone at a concentration of 80ng/disc was not significantly different to that of the untreated UBM disc (9.1 ± 2.3(×103) cells; p=0.58). In contrast, both treatments with CBD-HGF showed statistically increased cell proliferation compared to the untreated UBM.

Clinical Outcome

All animals (N=15) survived with no complications until elective euthanasia at 60-day after initial surgery. No aneurysmal change in the implanted patches was observed in any of the groups at necropsy (Figure 1C). Connective tissues covered the epicardial side of the patch area with a slight adhesion in the F and U groups. Severe adhesion was observed between the Dacron patch and pericardium/lung (D group) with deformity of the patch (Figure 1D). A thin fibrous encapsulation was present on the endocardial side in the D group that was easily separated from the patch. In the F and U groups, the patches were completely replaced with a white connective tissue with a thickness comparable to that of the adjacent normal myocardial wall (Figure 1E).

Electromechanical Mapping

Local unipolar and bipolar voltage electrograms were recorded. More than 200 discrete points were used to map the right ventricle. Mean electrical activity in the patch regions was 1.49±0.82 mV in the F group, which was statistically greater than 0.93±0.71 mV in the U group and 0.30±0.22 mV in the D group (p<0.05), and less than the normal myocardium (8.24±2.49mV; p<0.05) (Figure3A). The LLS was significantly improved in the F group (0.51±1.57 %) compared with the U group (−1.06±1.84 %; p<0.05) and the D group (−2.72±2.59 %; p<0.05), while they were significantly inferior to the normal myocardium (13.7±4.3 %; p<0.05) (Figure3B).

Figure 3.

A: Electrical activity in the patches. CBD-HGF-UBM patch shows the greatest electrical activity compared to the others(*p<0.05). B: LLS of the patch regions. CBD-HGF-UBM patch is positively contractile, whereas the UBM and Dacron patches are dyskinetic(*p<0.05).

Histology and Immunohistochemistry

Histological examinations of the F group tissue showed numerous cells through the entire patch, with a monolayer of factor VIII positive cells on the endocardial surface of the remodeled patch (endothelial cells), and predominantly α-SMA positive cells homogenously distributed through the entire remodeled patch (Figure 4A–C). In the U group, the distribution and phenotypic expression of cells in the remodeled patch, as well as the thickness of the remodeled tissue, were similar to those of the F group, with the exception that α-SMA positive cells were predominantly localized at the endocardial aspect and edges of the patch area (Figure 4D–F). In both the F and U group, there was no UBM remnant visible. In the D group, while α-SMA positive cells were found through the entire patch region, the thickness of the tissue was much less than that of the F or U group (Figure 4H). The host response to the Dacron patch was consistent with a foreign body response (Figure 4G). Within the tissue that infiltrated the patch, scattered isolated islands of α-sarcomeric actinin positive cells were observed in the F group (approximately 17.1 % of the tissue fields out of the entire patch region in the F group showed the presence of α -actinin positive cells), but not in the U and D groups (Figure 4I).

Figure 4. Histological preparation of the patches at 60-day after implantation.

A,B,C: The CBD-HGF-UBM patches show a monolayer of factor VIII positive cells, and predominantly α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) positive cells homogenously spread to the entire patch area beneath the endothelial monolayer. D,E,F: The UBM patches show α-SMA positive cells predominantly distributed in the endocardial aspect and in the edge of the patch area with a endocardial monolayer of factor VIII positive cells. G,H: The thickness of α-SMA positive cells is much less than those of the CBD-HGF-UBM or UBM patches. Inflammatory reaction was seen along the Dacron patch (Da)(arrow).(Epi; epicardial side) I:CBD-HGF-UBM patch stained with α-sarcomeric actinin stain. Blue, green, and red indicate nuclei, phalliodin, and α-sarcomeric actinin, respectively.(A,D,G:H&E stain, B,E,H: α-SMA, C,F:Factor VIII, I: α-sarcomeric actinin, Black bar:200µm (×100), White bar:100µm (×200))

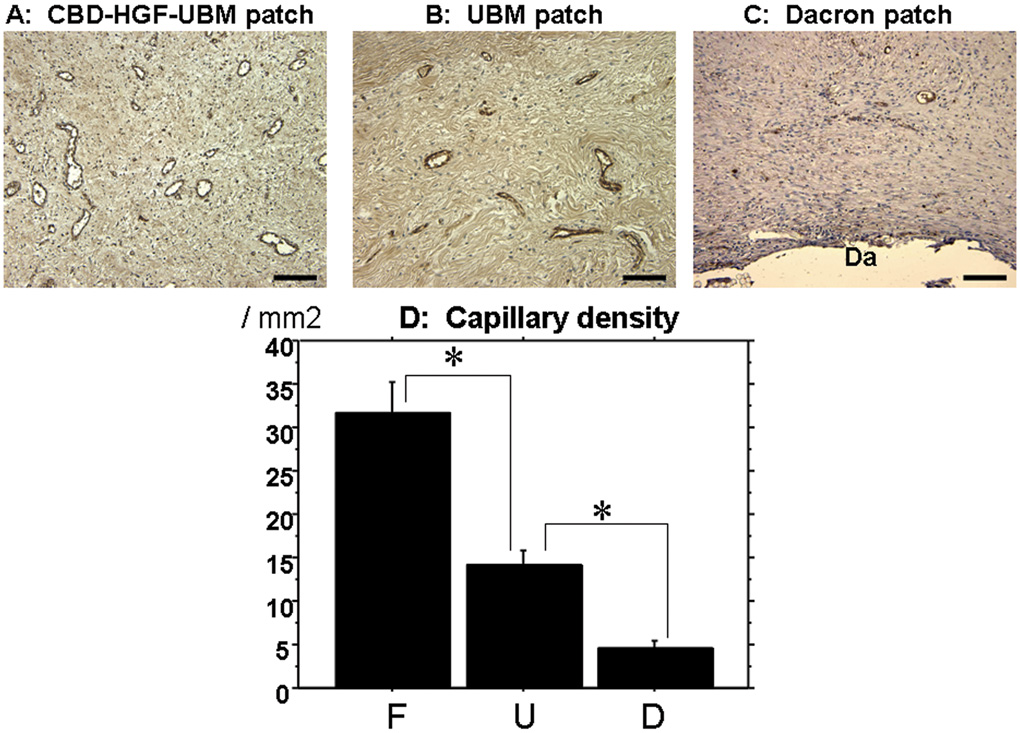

Capillary Density

The capillary density was the highest in the F group (31.7 ± 20.0/mm2) with statistically significant difference, compared with 14.3±10.5/mm2 in the U group and 4.6±4.4/mm2 in the D group (Figure 5). A common characteristic in the three groups was that the capillary structures were predominantly distributed in epicardial aspect of the patches.

Figure 5. Capillary density and representative images.

A,B,C: Representative factor VIII staining in each patch for capillary density study (A:CBD-HGF-UBM patch, B:UBM patch, C:Dacron patch)(Black bar:100µm). D:Capillary density. CBD-HGF-UBM patch shows highest capillary density of all (*p<0.05). (Da;Dacron patch, F;CBD-HGF-UBM patch group, U;UBM patch group, D;Dacron patch group)

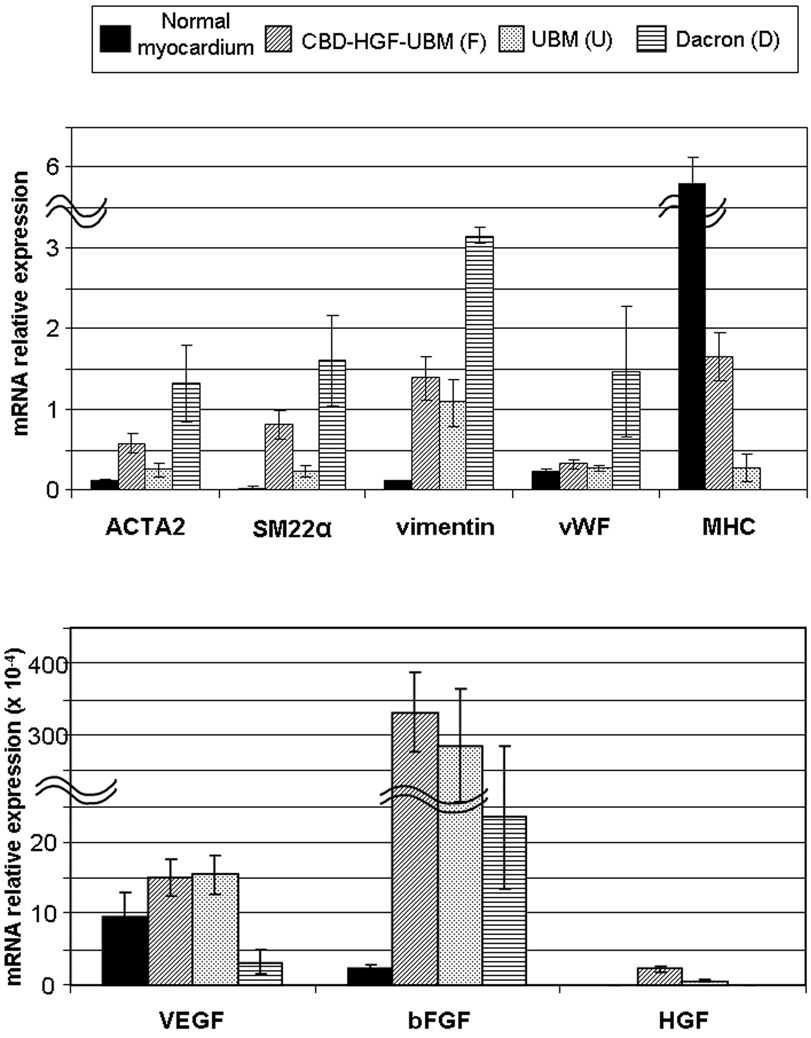

Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR

mRNA expression was normalized by the expression of a housekeeping gene (GAPDH). The results are summarized in Table 2 and Figure 6. In the F and U groups, the early mesenchymal markers (i.e.,ACTA2, SM22α, Vimentin) were expressed significantly higher than in the normal myocardium. There was also higher expression of mesenchymal markers in the F group as compared to the U group. Expression of vWF was similar in the F and U groups and was not statistically different from the normal myocardium. In contrast, the expression levels of vWF, ACTA2, SM22α, and Vimentin were significantly higher in the D group than the other groups including the normal myocardium, which is consistent with the hyperplasic scar formation observed histologically in the D group. The expression of MHC in the F and U groups was detected with significantly higher level in the F group, while it was not detected in the D group. Both VEGF and bFGF were expressed significantly higher in the F and U groups than in the D group. The expression of HGF was higher in the F group than in the U group (p<0.05), while there was no HGF detected in the normal myocardium and the D group.

Table2.

Results of Quantitative Real-time RT-PCR

| Normal myocardium |

CBD-HGF-UBM (F) |

UBM (U) | Dacron (D) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACTA2 | 0.13±0.04 | 0.58±0.45 * ** *** | 0.25±0.25 *** | 1.32±0.98 * |

| SM22α | 0.032±0.034 | 0.81±0.61 * ** *** | 0.23±0.22 * *** | 1.61±1.13 * |

| Vimentin | 0.11±0.03 | 1.39±1.03 * *** | 1.09±0.98 * *** | 3.15±2.47 * |

| vWF | 0.23±0.11 | 0.32±0.19 *** | 0.27±0.07 *** | 1.47±1.84 * |

| MHC | 5.82±1.24 | 1.65±0.67 * ** | 0.28±0.37 * | - |

| VEGF (×10−4) | 9.68±11.27 | 14.97±11.4 *** | 15.46±8.77 *** | 3.14±3.36 * |

| bFGF (×10−4) | 2.31±1.82 | 339±198 * *** | 282±260 * *** | 23.4±24.2 * |

| HGF (×10−4) | - | 2.24±0.82 | 0.6±0.27 | - |

(Expressed with the mRNA level / GAPDH)

ACTA2=vascular smooth muscle α-actin 2; bFGF= basic fibroblast growth factor; GAPDH = glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; HGF=hepatocyte growth factor; MHC= betamyosin heavy chain; SM22α = smooth muscle 22α; VEGF=vascular endothelial growth factor; vWF=von Willebrand factor.

(p<0.05; *vs Normal myocardium, **vs UBM (U),*** vs Dacron (D))

Figure 6. Graphs of quantitative real-time RT-PCR.

ACTA2=vascular smooth muscle α-actin 2;bFGF=basic fibroblast growth factor; GAPDH = glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; HGF=hepatocyte growth factor; MHC= beta-myosin heavy chain; SM22α = smooth muscle 22α; VEGF=vascular endothelial growth factor; vWF=von Willebrand factor.

Discussion

The present study showed that the addition of CBD-HGF to UBM increased proliferation of endothelial cells to a greater extent than the untreated UBM. Histological analyses showed that the implanted CBD-HGF-UBM patches resulted in constructive remodeling that consisted of a monolayer of endothelial cells, well-organized myofibroblasts, and scattered cells that are tentatively identified as cardiomyocytes. One of the most important findings in this study was that CBD-HGF-UBM patch showed an improved recovery of mechanical and electrophysiological functions. The CBD-HGF-UBM patches were positively contractile, whereas the untreated UBM and Dacron patches were dyskinetic. Likewise, recovery of the electrical activity in the patches was the greatest in the CBD-HGF-UBM, although it was far less than the normal myocardium.

The morphological observations and gene expression analyses suggest that the reparative pathways for untreated UBM patches and CBD-HGF-UBM patches were the same, but that the rate of repair occurred more slowly for the untreated UBM. In contrast, the host response to the Dacron patch was more consistent with a chronic foreign body hyperplastic response with scar tissue formation and the presence of inflammatory cells. The results of histology and RT-PCR indicate that the repaired tissues in the untreated UBM and CBD-HGF-UBM patches are different from the typical myocardial scar. For example, healed wound tissue from the Dacron patch-treated hearts had no evidence for MHC gene expression or α-actinin positive cells, markers that are commonly utilized to identify cardiomyocytes. The high expression of growth factors (i.e., VEGF, bFGF, HGF) in the CBD-HGF-UBM and untreated UBM patches compared to those in normal myocardium and Dacron patches suggest that cells present in the UBM patches are participating in the remodeling response.

The results emphasize the importance of rapid and aggressive angiogenesis in the remodeled scaffold. In the untreated UBM, the repopulated cells are localized on the endocardial aspect and at the edges of the patch where blood supplies exist. The more uniform distribution of cells throughout the remodeled CBD-HGF-UBM was associated with an increased vascularity which implied increased blood supply. The mechanisms by which HGF promotes angiogenesis and the source of the cells that populate the scaffold remain unclear. However, there is evidence that there is a circulating source of progenitor cells, including cells from the bone marrow, that are recruited to the site of ECM remodeling25,26,27.

Recent studies have shown that non-crosslinked ECM scaffolds promote an anti-inflammatory, accommodative immune response, with an accumulation of macrophages expressing the M2 phenotype28. The treatment of ECM scaffolds and tissues with crosslinking agents (i.e., Periguard™) has been advocated to slow degradation and increase mechanical integrity of the graft. The crosslinking process necessarily eliminates the release of bioactive peptides that are beneficial to the remodeling response (e.g., bacteriostasis, chemotaxis, angiogenesis). Furthermore, chemically crosslinked ECM scaffolds induce macrophages to express a pro-inflammatory phenotype that results in increased fibrous connective tissue formation28.

There are several limitations to the present study. First, no effort was made to examine electrical couplings and gap junctions to prove regeneration of the conducting system. Given the nascent signs of electrical remodeling (i.e., sparse myocytes, significant but slight electrical activity in the patches), however, those electrical signals might be attributed to the aggregation of electrophysiologic activity by immature mesenchymal cells29,30. Second, the study only evaluated a single time point. It is not clear how the remodeling progresses in the period immediately after implantation or in the long term, which should be our next tasks to be investigated to fully characterize the remodeled tissues. However, it is known that naturally occurring ECM scaffolds degrade within 60–90 days after implantation15,16, so any subsequent adaptations of the myocardium would likely be a consequence of remodeling in response to local environmental cues. Third, a RV model was utilized to decrease mortality and morbidity for the animal, and as a comparison to previous results. Although a UBM patch manufactured by the identical method described for the control patch has been shown to be effective and durable for repair of the left ventricle4, further studies including the left ventricular model and a diseased model (i.e., infarction) are needed to determine the efficacy of the CBD-HGF treatment to UBM. It is also important to test our patch in a infarcted heart model because blood supplies to the implanted patch from the surrounding tissue would significantly be reduced or be completely shut off, which might negatively influence myocardial remodeling in the patch. Fourth, we did not investigate the impact of the remodeled tissues on the global cardiac function. Given the results of electrical activity and regional contractility in this study, the functional contribution of the patch area might be insignificant at 60 days after implantation. To make it clear, we plan to utilize a catheter-based pressure-volume assessment at sequential time points in the future study. Likewise, it is important to evaluate the synchronization between the remodeled tissue and the surrounding myocardium using such an echocardiography. Finally, the gene expression and immunofluorescent staining is consistent with the appearance of cells with cardiomyocyte characteristics in the cardiac wounds repaired with CBD-HGF-UBM. The current results cannot prove whether HGF-UBM patch actually stimulated cardiomyocyte regeneration in the cardiac wound. Thus, a more rigorous analysis of additional cardiomyocyte and cell proliferation markers will be necessary to definitively identify the presence of newly regenerated cardiomyocytes in these repaired wounds.

Conclusion

The CBD-HGF-UBM patch demonstrated significantly increased contractility and electrical activity compared to UBM alone or Dacron, and facilitated a homogeneous repopulation of host cells which may include cardiomyocytes. UBM incorporated with CBD-HGF may contribute to site-specific constructive myocardial remodeling as a substitute for synthetic materials that are currently used for applications such as surgical ventricular restoration.

Acknowledgements

The expert assistance of Kazuro L. Fujimoto, MD, PhD, Kimimasa Tobita, MD, Gregory Gibson, BS, Jennifer Gabany, MSN,CRNP-C,CCRC, Stacy Cashman, LVT, David Fischer, BS, Melanie O'Malley, LVT, and Masako Yokoyama, BS is gratefully acknowledged.

Funding Source:

The project described was supported in part by NIHAR053603.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Badylak SF. Xenogeneic extracellular matrix as a scaffold for tissue reconstruction. Transplant Immunol. 2004;12:367–377. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2003.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ota T, Taketani S, Iwai S, Miyagawa S, Furuta M, Hara M, et al. Novel method of decellularization of porcine valves using polyethylene glycol and gamma irradiation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83(4):1501–1507. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.11.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kochupura PV, Azeloglu EU, Kelly DJ, Doronin SV, Badylak SF, Krukenkamp IB, et al. Tissue-engineered myocardial patch derived from extracellular matrix provides regional mechanical function. Circulation. 2005;112 Suppl:I144–I149. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.524355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robinson KA, Li J, Mathison M, Redkar A, Cui J, Chronos NA, et al. Extracellular matrix scaffold for cardiac repair. Circulation. 2005;112 suppl:I135–I143. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.525436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ota T, Gilbert TW, Badylak SF, Schwartzman D, Zenati MA. Electromechanical characterization of a tissue-engineered myocardial patch derived from extracellular matrix. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;133(4):979–985. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bussolino F, Di Renzo MF, Ziche M, Bocchietto E, Olivero M, Naldini L, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor is a potent angiogenic factor which stimulates endothelial cell motility and growth. J Cell Biol. 1992;119(3):629–641. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.3.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morishita R, Aoki M, Yo Y, Ogihara T. Hepatocyte growth factor as cardiovascular hormone: role of HGF in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease. Endocr J. 2002;49:273–284. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.49.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Urbanek K, Rota M, Cascapera S, Bearzi C, Nascimbene A, De Angelis A, et al. Cardiac stem cells possess growth factor-receptor systems that after activation regenerate the infracted myocardium, improving ventricular function and long-term survival. Circ Res. 2005;97(7):663–673. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000183733.53101.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trusolino L, Cavassa S, Angelini P, Andó M, Bertotti A, Comoglio PM, et al. HGF/scatter factor selectively promotes cell invasion by increasing integrin avidity. FASEB J. 2000;14(11):1629–1640. doi: 10.1096/fj.14.11.1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takimoto Y, Teramachi M, Okumura N, Nakamura T, Shimizu Y. Relationship between stenting time and regeneration of neoesophageal submucosal tissue. ASAIO J. 1994;40(3):M793–M797. doi: 10.1097/00002480-199407000-00107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miyagawa S, Sawa Y, Taketani S, Kawaguchi N, Nakamura T, Matsuura N, et al. Myocardial regeneration therapy for heart failure: hepatocyte growth factor enhances the effect of cellular cardiomyoplasty. Circulation. 2002;105(21):2556–2561. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000016722.37138.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kitajima T, Terai H, Ito Y. A fusion protein of hepatocyte growth factor for immobilization to collagen. Biomaterials. 2007;28(11):1989–1997. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ota T, Sawa Y, Iwai S, Kitajima T, Ueda Y, Coppin C, et al. Fibronectin-hepatocyte growth factor enhances reendothelialization in tissue-engineered heart valve. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80(5):1794–1801. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown B, Lindberg K, Reing J, Stolz DB, Badylak SF. The basement membrane component of biologic scaffolds derived from extracellular matrix. Tissue Eng. 2006;12(3):519–526. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilbert TW, Stewart-Akers AM, Simmons-Byrd A, Badylak SF. Degradation and remodeling of small intestinal submucosa in canine Achilles tendon repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(3):621–630. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Record RD, Hillegonds D, Simmons C, Tullius R, Rickey FA, Elmore D, et al. In vivo degradation of 14C-labeled small intestinal submucosa (SIS) when used for urinary bladder repair. Biomaterials. 2001;22(19):2653–2659. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gepstein L, Hayam G, Shpun S, Ben-Haim SA. Hemodynamic evaluation of the heart with a nonfluoroscopic electromechanical mapping technique. Circulation. 1997;96:3672–3680. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.10.3672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Packer DL, Stevens CL, Curley MG, Bruce CJ, Miller FA, Khandheria BK, et al. Intracardiac phased-array imaging: methods and initial clinical experience with high resolution,under blood visualization: initial experience with intracardiac phased-array ultrasound. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:509–516. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01764-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwartzman D, Bonanomi G, Zenati MA. Epicardium-based left atrial ablation: impact on electromechanical properties. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2003;14:1087–1092. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2003.03230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gepstein L, Goldin A, Lessick J, Hayam G, Shpun S, Schwartz Y, et al. Electromechanical characterization of chronic myocardial infarction in the canine coronary occlusion model. Circulation. 1998;98:2055–2064. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.19.2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iwai S, Sawa Y, Taketani S, Torikai K, Hirakawa K, Matsuda H. Novel tissue-engineered biodegradable material for reconstruction of vascular wall. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80(5):1821–1827. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.03.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lyons GE, Schiaffino S, Sassoon D, Barton P, Buckingham M. Developmental regulation of myosin gene expression in mouse cardiac muscle. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:2427–2436. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.6.2427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang KC, Figueredo VM, Schreur JH, Kariya K, Weiner MW, Simpson PC, et al. Thyroid hormone improves function and Ca2+ handling in pressure overload hypertrophy. Association with increased sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase and alpha-myosin heavy chain in rat hearts. J Clin Invest. 1997;100(7):1742–1749. doi: 10.1172/JCI119699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kobayashi T, Hamano K, Li TS, Katoh T, Kobayashi S, Matsuzaki M, et al. Enhancement of angiogenesis by the implantation of self bone marrow cells in a rat ischemic heart model. J Surg Res. 2000;89(2):189–195. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2000.5828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brountzos E, Pavcnik D, Timmermans HA, Corless C, Uchida BT, Nihsen ES, et al. Remodeling of suspended small intestinal submucosa venous valve: an experimental study in sheep to assess the host cells' origin. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2003;14(3):349–356. doi: 10.1097/01.rvi.0000058410.01661.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Badylak SF, Park K, Peppas N, McCabe G, Yoder M. Marrow-derived cells populate scaffolds composed of xenogeneic extracellular matrix. Exp Hematol. 2001;29(11):1310–1318. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(01)00729-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zantop T, Gilbert TW, Yoder MC, Badylak SF. Extracellular matrix scaffolds are repopulated by bone marrow-derived cells in a mouse model of Achilles tendon reconstruction. J Orthop Res. 2006;24(6):1299–1309. doi: 10.1002/jor.20071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Badylak SF, Gilbert TW. Immune response to biologic scaffold materials. Semin Immunol. 2007 Dec;11 doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.11.003. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heubach JF, Graf EM, Leutheuser J, Bock M, Balana B, Zahanich I, et al. Electrophysiological properties of human mesenchymal stem cells. J Physiol. 2004;554(3):659–672. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.055806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Halbach M, Pfannkuche K, Pillekamp F, Ziomka A, Hannes T, Reppel M, et al. Electrophysiological maturation and integration of murine fetal cardiomyocytes after transplantation. Circ Res. 2007;101(5):484–492. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.153643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]