Abstract

Extranodal marginal zone lymphomas of mucosa associated lymphoid tissue type (MALT lymphomas) develop from acquired reactive infiltrates directed against external or auto-antigens. Although some European cases of ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma have been associated with Chlamydia psittaci infections, C. psittaci has not been detected in large studies of U.S. based cases. To evaluate whether the growth of U.S. based ocular adnexal MALT lymphomas may be promoted by a similar antigen, the expressed immunoglobulin VH genes were identified and analyzed in 10 cases. Interestingly, the VH genes in 2 cases used the same VH1 family V1-2 gene segment, and 3 cases used the same VH4 family V4-34 gene segment. The other five cases all used different gene segments V4-31, V5-51, V3-23, V3-30, and V3-7. All of the VH genes were mutated from germline, with percent homologies ranging between 96.9% to 89.0%. The distribution of replacement and silent mutations within the VH genes was non-random consistent with the maintenance of immunoglobulin function and also strongly suggestive of antigen selection in the 6 VH genes with highest mutation loads. The CDR3 sequences in 2 of 3 VH-34 cases were the same size (15 amino acids), and had similar sizes in the 2 VH1-2 cases (18 & 16 amino acids). In conclusion, U.S. based MALT lymphomas of the ocular adnexa preferentially express a limited set of VH gene segments not frequently used by other MALT lymphomas and consistent with some recognizing similar antigens. Analysis of somatic mutations present within the VH genes is also consistent with antigen binding stimulating the growth of these lymphomas.

Keywords: MALT lymphoma, ocular adnexa, immunoglobulin VH gene

Introduction

Extranodal marginal zone lymphomas of mucosa associated lymphoid tissue type (MALT lymphomas) are typically indolent B-cell neoplasms that develop out of acquired reactive infiltrates associated with localized long standing autoimmune diseases or chronic infections 1,2. The growth of early MALT lymphomas is thought to be dependent on antigen stimulation but may become antigen independent over time with the acquisition of additional genetic abnormalities 1,3. Antigen stimulation of MALT lymphoma growth is strongly supported by studies of gastric MALT lymphomas which develop out of infiltrates associated with chronic H. pylori associated infections and can often be cured with H. pylori eradicating antibiotics 4–6. Studies by an Italian group have suggested Chlamydia psittaci may play a similar role in ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma and reported tumor regressions in patients receiving C psittaci eradicating antibiotic treatment 7,8. However, studies of U.S. based cases have not found evidence for C psittaci in ocular adnexal MALT lymphomas using sensitive PCR techniques 9,10.

Analysis of expressed immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region (VH) genes can provide strong support for surface immunoglobulin mediated direct antigen stimulation of lymphoma growth without prior identification of the reactive MALT antigenic trigger 11–15. For example, studies of salivary gland MALT lymphoma VH genes have demonstrated that approximately 60% of cases use a single VH gene segment, V1–69, which is suggestive of antigen selection since there are approximately 40 different functional VH gene segments that can potentially be used16. In addition, antigen selection of salivary gland MALT lymphoma growth is further supported from finding non-random distributions of point mutations typically present in the expressed VH genes and stretches of similar CDR3 amino acid sequences in VH genes from different patients 12,16. Evidence supporting antigen stimulation of low grade B-cell neoplasm growth is not limited to MALT lymphomas as recent studies of chronic lymphocytic leukemias have documented nearly identical expressed heavy and light chain variable genes from different patients suggesting that some of these cases recognize the same antigens or epitopes14,17–19.

In this study, we identified and analyzed the VH genes used by 10 U.S. based ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma cases to look for evidence of antigen stimulation. Our findings provide support that direct antigen stimulation by a common antigen is playing a role in the growth of these neoplasms that are not associated with C psittaci.

Materials and Methods

Cases

Cases of MALT lymphoma involving the ocular adnexa as defined by the WHO2 with available frozen tissue were identified by searching the pathology files of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and the Cleveland Clinic. Ten of the identified 13 cases were included in our previous study of ocular MALT lymphoma 10, and three cases are new to this study. The hematoxylin and eosin stained slides were reviewed on all cases. Immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry studies (done on all cases) preformed as described 10 were also reviewed. Two independent real-time nested PCR assays for detection of C psittaci were previously performed on 7 of the cases as described 10. The research use of these specimens was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Pittsburgh (no. 0505102), the Cleveland Clinic (no. 81008), and the University of Utah (no. 13172).

VH Gene Analysis

Genomic DNA was prepared from frozen tissues using the Gentra Puregene kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA) or the Genomic DNA Purification kit (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, MN) following the manufacture’s directions. Rearranged immunoglobulin heavy chain variable regions were amplified from the isolated DNA using a reverse 3’ JH primer and seven different 5’ VH leader region primers, 6 of which were previously described20, with an additional primer that perfectly matches the leader sequence of the VH3–21 gene segment, 5’- CCATGGAACTGGGGCTCCGC . Genomic DNA (20 ng) was amplified in 1x GoTaq flexi PCR buffer (Promega Corp., Madison, WI), 3 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM each dNTP, 0.2 µM leader prime, 0.2 µM J primer, and 1 unit GoTaq Flexi DNA polymerase in a final volume of 20 µL. Cycling conditions were 2 minutes at 94°C followed by 35 cycles of 20 seconds at 94 °C, 10 seconds at 55°C, 30 seconds at 72°C followed by a hold 2 minutes at 72°C and cool down. The PCR reactions were run on a 2% agarose gel and the DNA was visualized with ethidium bromide (0.5 µg/mL). Prior to sequencing, primers and dNTP were removed from the reactions with the most prominent bands by mixing 10 µL of reaction with 2 µL ExoSAP-IT (USB Corp., Cleveland, OH) and incubating at 37°C for 45 minutes followed by 15 minutes at 85°C. The treated samples were appropriately diluted in water and 6 µL was mixed with 8 µL of the appropriate leader primer (0.8 µM) and subjected to DNA sequence analysis using BigDye Terminator chemistry (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, CA). The readable DNA sequences were searched against the IMGT database (http://imgt.cines.fr/) to identify the most closely related VH, DH and JH germline segments and to confirm a productive VDJ rearrangement.

Results

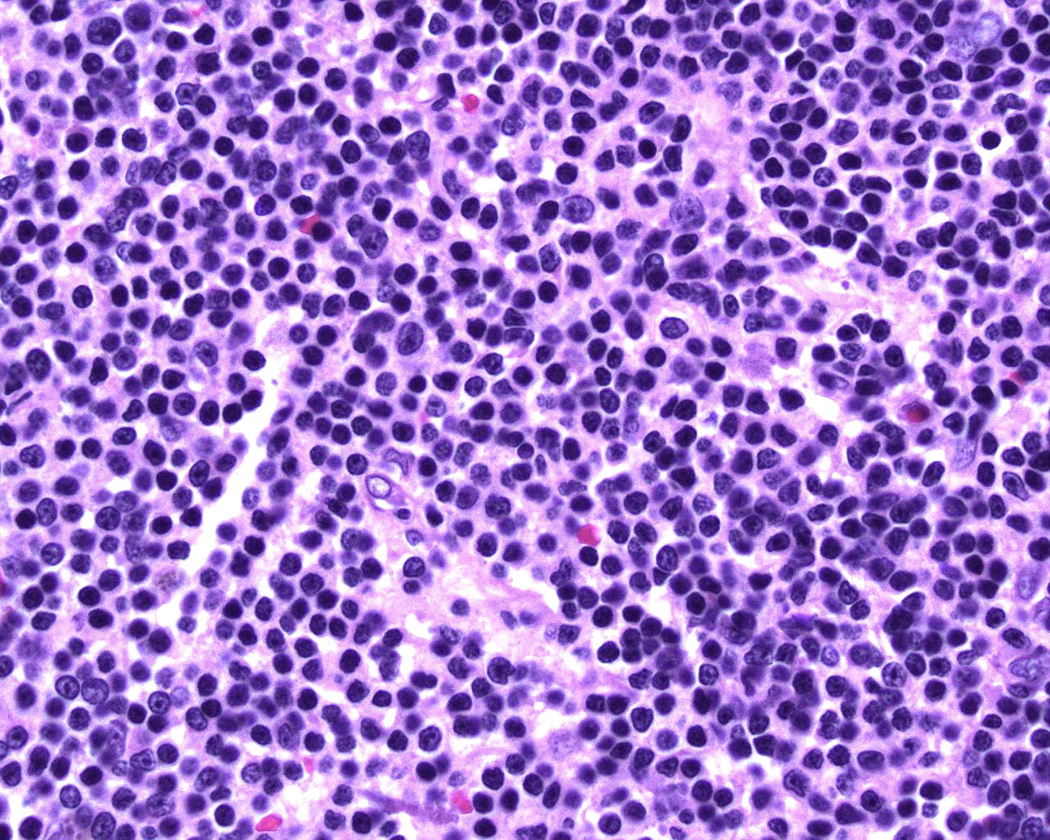

Of the 13 ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma cases initially identified with available frozen tissue, the expressed VH genes were successfully obtained from the 10 cases further described in Table 1. The patients mean age was 60 years old, range 43 years to 82 years, and included 6 males and 4 females. Evaluated biopsies were from orbital soft tissue in 9 cases, the lacrimal gland in 2 cases, with one case (#9) having both orbit and lacrimal gland biopsies. All showed morphological features typical of orbital MALT lymphoma, namely a predominance of small lymphocytes admixed with variable numbers of monocytoid appearing cells and sometimes smaller numbers of plasma cells (Figure 1). Flow cytometry which was performed in all cases revealed populations of CD5 negative, CD10 negative B-cells with monotypic expression of kappa (8/10 cases) or lambda (2/10 cases) light chains. Sensitive PCR testing for C. psittaci was negative in all 7 cases evaluated. Only one patient (# 4) had a prior history of lymphoma, reportedly a diffuse large cell lymphoma of the small bowel treated with R-CHOP 2 years prior to the orbit biopsy, and 9 months later a cutaneous low grade lymphoma with a follicular growth pattern treated with radiation. Slides were not available for review from either biopsy, but the patient was clinically thought to represent a stage 1 orbital MALT lymphoma and received only radiation treatment.

Table 1.

Ocular MALT lymphoma case information

| Case # | Age/Sex | Biopsy Site | Light Chain | C. Psittaci Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 54 / M | R Lacrimal | Kappa | Neg |

| 2 | 74 / F | R Orbit | Kappa | Neg |

| 3 | 55 / F | L Orbit | Lambda | Neg |

| 4 | 81 / M | L Orbit | Kappa | ND* |

| 5 | 82 / M | L Orbit | Kappa | ND |

| 6 | 76 / M | L Orbit | Kappa | Neg |

| 7 | 43 / F | R Orbit | Kappa | Neg |

| 8 | 68 / M | L Orbit | Lambda | Neg |

| 9 | 58 / F | R Orbit/Lacrimal | Kappa | ND |

| 10 | 80 / M | L Orbit | Kappa | Neg |

ND , Not determined

Figure 1.

Hematoxylin and eosin stained section of a representative case (#4) showing morphologic features typical of ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma.

A single rearranged functional VH gene without stop codons was identified in the 10 cases by directly sequencing PCR products generated by amplifying lymphoma DNA with VH leader and JH primers. Comparing the lymphoma VH genes to germline genes in the IMGT database revealed that 2 used VH gene segments from the VH1 family, 4 used VH4 family gene segments, 3 used VH3 family gene segments, and one used a VH5 family segment (Table 2). Interestingly, the 2 VH1 family cases used the same V1–2 gene segment, while 3 of the 4 VH4 family cases used the same V4–34 gene segment. The 3 VH3 family cases all used different V3 gene segments.

Table 2.

Ocular MALT Lymphomas use of VH gene segments

| Case | Family | Name | # Mutations | % Homology* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | VH1 | V1-2 | 19 | 93.5 |

| 2 | VH1 | V1-2 | 20 | 93.1 |

| 3 | VH4 | V4-34 | 17 | 94.2 |

| 4 | VH4 | V4-34 | 32 | 89.0 |

| 5 | VH4 | V4-34 | 19 | 93.5 |

| 6 | VH4 | V4-31 | 9 | 96.9 |

| 7 | VH3 | V3-30 | 21 | 92.9 |

| 8 | VH3 | V3-74 | 24 | 91.8 |

| 9 | VH3 | V3-23 | 10 | 96.9 |

| 10 | VH5 | V5-51 | 23 | 91.8 |

Relative to the most closely related germline gene

All of the lymphoma VH gene segments showed significant numbers of point mutations from the most closely related germline counterparts, with percent homologies ranging between 96.9% to 89.0% homology, mean percent homology 93.4% +/− 2.4%. The mutation locations, complementarity determining regions (CDRs) or framework regions (FWRs), and type, those causing an amino acid replacement (R) or not, i.e. silent (S) are listed in Table 3. All of the lymphoma VH genes segments had fewer replacement mutations in the FWRs than would be expected by chance alone21, i.e. random mutation, consistent with the maintenance of immunoglobulin functionality 22. The 5 cases with higher numbers of mutations (#2,4,5,8, & 10) also had fewer replacement mutations than would be expected by chance alone in the CDRs, suggestive of negative selection or selection against replacement mutations in these areas. In only one case (#1) were mutations above what would be expected by chance alone in the CDRs that could be suggestive of positive selection.

Table 3.

Distribution of mutations in lymphoma VH segments

| Case # | CDR 1&2 |

FWR 1,2&3 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R* | S | R/S | Random R/S | R | S | R/S | Random R/S | |

| 1 | 8 | 1 | 8.0 | 4.3 | 6 | 4 | 1.5 | 3.0 |

| 2 | 5 | 3 | 1.7 | 4.3 | 5 | 7 | 0.7 | 3.0 |

| 3 | 3 | 1 | 3.0 | 4.5 | 9 | 11 | 0.8 | 2.7 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 1.0 | 4.5 | 13 | 11 | 1.2 | 2.7 |

| 5 | 4 | 3 | 1.3 | 4.5 | 6 | 6 | 1.0 | 2.7 |

| 6 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 4.1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2.7 |

| 7 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 3.9 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 2.9 |

| 8 | 5 | 3 | 1.7 | 4.2 | 11 | 5 | 2.2 | 2.8 |

| 9 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 3.6 | 3 | 2 | 1.5 | 2.9 |

| 10 | 6 | 5 | 1.2 | 3.5 | 5 | 7 | 0.7 | 3.3 |

Columns headed by “R” or “S” give the number of replacement or silent mutations, respectively, relative to the most closely related germline VH gene segment. “Random R/S” refers to the ratio of all possible replacement to silent mutations.

The CDR3 regions of the lymphoma VH genes appeared to be encoded by a variety of different D segments and to have variable sizes (Table 4). Most used either J4 or J6 joining segments, which are also employed the majority of normal B-cells23. No conserved amino acid motifs in the CDR3 regions were appreciated among the different cases.

Table 4.

Ocular lymphoma VH gene CDR3 sequences

| Case # | DH* | JH | Amino Acid Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2-2 | 4b | GPRQCSSITCLSYFHY |

| 2 | 3–16 | 6b | AARVVRLFNPDRSSGMDV |

| 3 | 6–13 | 6b | GEAVTGPPRSDDMDV |

| 4 | 5-5 | 4b | TGGPHLGNSDGVTHS |

| 5 | 2–15 | 4b | ITEIIDVHYCSGGDCNEGGFDY |

| 6 | 4-4 | 6b | VHSNYYYRMDV |

| 7 | 3–9 | 4b | QYDILTDYYKWGVFDY |

| 8 | 1-1 | 4b | GNGY |

| 9 | 5–24 | 4b | AWAYIAGNYFDY |

| 10 | 2–21 | 3b | PYCGGDCYSGDAPFHI |

DH and JH refer to the germline heavy chain diversity and joining segments used in the CDR3 , respectively

Discussion

The development and early growth of MALT lymphomas appears to be dependent on antigen stimulation, which can be direct, mediated by surface immunoglobulin, and/or indirect and mediated by T-cells. The antigens playing key roles in MALT lymphomagenesis are mostly unknown, but are likely dependent on the type of tissue the lymphomas arise from and could also vary with different geographical areas. We analyzed the VH genes expressed by 10 cases of ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma to look for evidence of direct antigen stimulation. An important finding along this line was observing preferential use of certain VH gene segments with 2 cases using the same V1–2 gene segment and 3 other cases using the same V4–34 VH gene segment. Since there are approximately 40 different functional VH gene segments that can potentially be used 23,24, the probability that 2 or 3 of the 10 cases evaluated would use the same VH gene segments by chance alone is 0.023 and 0.002, respectively. By contrast, approximately 3% of normal peripheral blood B-cells use V1–2 and V4–34, which is the expected frequency if use is random23. One of the other 10 cases expressed a VH4 family gene segment different from V4–34, V4–31, which further suggests orbital MALT lymphomas may also display preferential use of VH4 family gene segments.

Non-random or preferential use of certain VH gene segments suggests that these encode important determinants that have been selected by an antigen binding to surface immunoglobulin leading to stimulation of B cell growth. Besides our study, preferential use of V4–34 and V1–2 has been reported for other types of low grade B-cell neoplasms. The V4–34 gene segment is used by approximately 20% of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) cases with mutated VH genes 25, and by approximately 60% of primary central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma cases 26,27 (Table 5). Preferential use of V1–2 is seen in splenic marginal zone lymphomas and used by approximately 40% of cases 28,29. It is interesting that the expression of V1–2 and V4–34 does not appear to be increased above random use levels in MALT lymphomas that occur at other sites such as the stomach, lung, or salivary gland 12,30,31. This is consistent with the concept that antigens stimulating MALT lymphoma growth in the ocular adnexal will be different than those at other MALT lymphoma sites. It may be significant regarding the antigen specificity of ocular adnexal MALT lymphomas that both V1–2 and V4–34 are used by auto-antibodies, and almost all cold agglutinin auto-antibodies employ V4–34 32.

Table 5.

Differential use of V1-2 and V4-34 segments

| Cell Types | V1-2 | V4-34 |

|---|---|---|

| Peripheral blood B-cells | 3%** | 3%** |

| Mutated CLL | 7% (3/46)* | 20% (9/46)* |

| Unmutated CLL | 8% (3/38)* | 3% (1/38)* |

| Splenic Marginal Zone Lymphoma | 42% (20/48)§ | 15% (7/48) § |

| 1° CNS Lymphoma | 0% (0/15)¶ | 60% (9/15) ¶ |

| Other MALT Lymphomas (gastric, salivary gland, lung) | 1% (1/76)¥ | 4% (3/76) ¥ |

Our findings of preferential use of V1–2 and V4–34 differ from the 2 earlier studies of ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma VH genes. In the study by Coupland et al. 33 that involved 26 cases, 2 (8%) used V4–34 and only 1 (4%) used V1–2, while none of the 12 cases analyzed by Hara et al. 34 used V1–2 or V4–34. Since the cases analyzed in Coupland’s study were European and those in Hara’s study were Japanese, it is possible that antigens driving ocular adnexal MALT lymphomagenesis vary depending on geographical location. This possibility is also supported by reports showing an association of C. psittaci with mostly Italian orbital MALT lymphoma cases 7,8,35, while U.S. based orbital MALT cases using sensitive PCR techniques appear to be C. psittaci negative 9,10,35. Technical considerations could also have complicated positive lymphoma VH gene identification in the study by Coupland et al. 33 since paraffin extracted DNA was used in nested PCR reactions involving consensus FW1 and FW2 primers and 65 total cycles of amplification.

All of the lymphoma VH genes identified in this study were mutated relative to their most closely related germline counterparts consistent with the proposed post-germinal center B-cell origin. In addition, the level of mutation we observed in the orbital MALT lymphoma VH gene segments (mean percent homology to germline of 93% +/- 2.4%) is also close to the mutation load values reported for MALT lymphomas that occur at other locations 12,16. Analysis of the point mutation types (replacement or silent) and distribution (FWRs or CDRs) within many of the VH gene segments suggested there is selection against mutations occurring in CDR1 and CDR2, or negative selection. Finding evidence of negative selection in these CDRs was not an artifact related to analyzing small numbers of mutations since the 5 cases showing clear negative selection also had some of the highest mutation loads. Negative selection observed in the CDRs of these cases is similar to the negative selection that was observed in the FWRs of all these cases which is an indicator of functionality in that many FWR residues cannot withstand replacement mutations if immunoglobulin function is to be maintained 22. Selection against replacement mutations in the CDRs is also a feature of VH genes expressed by MALT lymphomas that occur at other sites such as the salivary gland 36,37, and could function in preventing the disruption of antigen mediated signaling which may be detrimental to lymphoma cell survival 38,39. Negative selection is also seen with antibodies that display reactivity towards autoantigens and may play a role in preventing the emergence of high affinity variants 40.

The CDR3 nucleotide sequence, made up of randomly templated nucleotides and diversity and joining segments that have been shortened by nuclease trimming, is the most variable part of a VH gene and serves as a clonal marker 41. Because of the tremendous variability, antibodies that recognize the same antigens typically do not have similar CDR3 sequences 42–44. As such, not finding similarities of CDR3 sequences among our MALT lymphoma cases does not alter the possibility that some may recognize similar or common antigens. Since the size of the CDR3 sequence also plays an important role in antigen binding 45, it may be significant that the CDR3 of 2 cases using V4–34 are the same size, while the CDR3 sequences for the 2 V1–2 cases differ by only 2 amino acids.

In summary, our study suggests that U.S. based ocular adnexal MALT lymphomas that are not associated with C. psittaci preferentially express a limited set of VH gene segments not frequently used by MALT lymphomas that occur at other sites. This finding is consistent with these cases recognizing a common antigen that is responsible for selecting and promoting the transformation of B-cells with the frequently expressed VH gene segments via immunoglobulin mediated growth stimulation. Although the nature of the antigen is unknown, frequent use of the V4–34 and V1–2 gene segments as well as selection against replacement point mutations occurring in the CDRs, favors these cases recognizing a self or auto-antigen.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the ARUP Institute of Pathology.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no financial interests or conflicts with anything mentioned in this manuscript.

References

- 1.Isaacson PG, Du MQ. MALT lymphoma: from morphology to molecules. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:644–653. doi: 10.1038/nrc1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Stein H, et al. WHO Classification. Tumors of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. IARC Press. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suarez F, Lortholary O, Hermine O, et al. Infection-associated lymphomas derived from marginal zone B cells: a model of antigen-driven lymphoproliferation. Blood. 2006;107:3034–3044. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bayerdorffer E, Neubauer A, Rudolph B, et al. Regression of primary gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type after cure of Helicobacter pylori infection. Lancet. 1995;345:1591–1594. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90113-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parsonnet J, Hansen S, Rodriguez L, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric lymphoma. N Eng J Med. 1994;330:1267–1271. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199405053301803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wotherspoon AC, Doglioni C, Diss TC, et al. Regression of primary low-grade B-cell gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Lancet. 1993;342:575–577. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91409-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferreri AJ, Guidoboni M, Ponzoni M, et al. Evidence for an association between Chlamydia psittaci and ocular adnexal lymphomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:586–594. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferreri AJ, Ponzoni M, Guidoboni M, et al. Regression of ocular adnexal lymphoma after Chlamydia psittaci-eradicating antibiotic therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5067–5073. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosado MF, Byrne GE, Jr, Ding F, et al. Ocular adnexal lymphoma: a clinicopathologic study of a large cohort of patients with no evidence for an association with Chlamydia psittaci. Blood. 2006;107:467–472. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruiz A, Reischl U, Swerdlow SH, et al. Extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphomas of the ocular adnexa: multiparameter analysis of 34 cases including interphase molecular cytogenetics and PCR for Chlamydia psittaci. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:792–802. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000249445.28713.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bahler DW, Zelenetz AD, Chen TT, et al. Antigen selection in human lymphomagenesis. Cancer Res. 1992;52 5547s–5551s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bende RJ, Aarts WM, Riedl RG, et al. Among B cell non-Hodgkin's lymphomas, MALT lymphomas express a unique antibody repertoire with frequent rheumatoid factor reactivity. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1229–1241. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stevenson F, Sahota S, Zhu D, et al. Insight into the origin and clonal history of B-cell tumors as revealed by analysis of immunoglobulin variable region genes. Immunol Rev. 1998;162:247–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1998.tb01446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiorazzi N, Ferrarini M. B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: lessons learned from studies of the B cell antigen receptor. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:841–894. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lossos IS, Tibshirani R, Narasimhan B, et al. The inference of antigen selection on Ig genes. J Immunol. 2000;165:5122–5126. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.5122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miklos JA, Swerdlow SH, Bahler DW. Salivary gland mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma immunoglobulin V(H) genes show frequent use of V1-69 with distinctive CDR3 features. Blood. 2000;95:3878–3884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stamatopoulos K, Belessi C, Moreno C, et al. Over 20% of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia carry stereotyped receptors: Pathogenetic implications and clinical correlations. Blood. 2007;109:259–270. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-012948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tobin G, Thunberg U, Johnson A, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemias utilizing the VH3-21 gene display highly restricted Vlambda2-14 gene use and homologous CDR3s: implicating recognition of a common antigen epitope. Blood. 2003;101:4952–4957. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Widhopf GF, 2nd, Goldberg CJ, Toy TL, et al. Nonstochastic pairing of immunoglobulin heavy and light chains expressed by chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells is predicated on the heavy chain CDR3. Blood. 2008;111:3137–3144. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-073130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bahler DW, Campbell MJ, Hart S, et al. Ig VH gene expression among human follicular lymphomas. Blood. 1991;78:1561–1568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang B, Casali P. The CDR1 sequences of a major proportion of human germline Ig VH genes are inherently susceptible to amino acid replacement. Immunol Today. 1994;15:367–373. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90175-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shlomchik MJ, Aucoin AH, Pisetsky DS, et al. Structure and function of anti-DNA autoantibodies derived from a single autoimmune mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:9150–9154. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.9150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brezinschek HP, Brezinschek RI, Lipsky PE. Analysis of the heavy chain repertoire of human peripheral B cells using single-cell polymerase chain reaction. J Immunol. 1995;155:190–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lefranc MP, Lefranc G. The immunoglobulin factsbook. Academic press. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamblin TJ, Davis Z, Gardiner A, et al. Unmutated Ig V(H) genes are associated with a more aggressive form of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 1999;94:1848–1854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montesinos-Rongen M, Kuppers R, Schluter D, et al. Primary central nervous system lymphomas are derived from germinal-center B cells and show a preferential usage of the V4-34 gene segment. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:2077–2086. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65526-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thompsett AR, Ellison DW, Stevenson FK, et al. V(H) gene sequences from primary central nervous system lymphomas indicate derivation from highly mutated germinal center B cells with ongoing mutational activity. Blood. 1999;94:1738–1746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Algara P, Mateo MS, Sanchez-Beato M, et al. Analysis of the IgV(H) somatic mutations in splenic marginal zone lymphoma defines a group of unmutated cases with frequent 7q deletion and adverse clinical course. Blood. 2002;99:1299–1304. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.4.1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bahler DW, Pindzola JA, Swerdlow SH. Splenic marginal zone lymphomas appear to originate from different B cell types. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:81–88. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64159-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lenze D, Berg E, Volkmer-Engert R, et al. Influence of antigen on the development of MALT lymphoma. Blood. 2006;107:1141–1148. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sakuma H, Nakamura T, Uemura N, et al. Immunoglobulin VH gene analysis in gastric MALT lymphomas. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:460–466. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Y, Spellerberg MB, Stevenson FK, et al. The I binding specificity of Human VH4–34 (VH4–21) encoded antibodies is determined by both VH framework region 1 and complementarity determining region 3. J Mol Biol. 1996;256:577–589. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coupland SE, Foss HD, Anagnostopoulos I, et al. Immunoglobulin VH gene expression among extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphomas of the ocular adnexa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:555–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hara Y, Nakamura N, Kuze T, et al. Immunoglobulin heavy chain gene analysis of ocular adnexal extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:2450–2457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Decaudin D, de Cremoux P, Vincent-Salomon A, et al. Ocular adnexal lymphoma: a review of clinicopathologic features and treatment options. Blood. 2006;108:1451–1460. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-005017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bahler DW, Miklos JA, Swerdlow SH. Ongoing Ig gene hypermutation in salivary gland mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue-type lymphomas. Blood. 1997;89:3335–3344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bahler DW, Swerdlow SH. Clonal salivary gland infiltrates associated with myoepithelial sialadenitis (Sjogren's syndrome) begin as nonmalignant antigen- selected expansions. Blood. 1998;91:1864–1872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Friedman DF, Cho EA, Goldman J, et al. The role of clonal selection in the pathogenesis of an autoreactive human B cell lymphoma. J Exp Med. 1991;174:525–537. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.3.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lam KP, Kuhn R, Rajewsky K. In vivo ablation of surface immunoglobulin on mature B cells by inducible gene targeting results in rapid cell death. Cell. 1997;90:1073–1083. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80373-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Borretzen M, Randen I, Zdarsky E, et al. Control of autoantibody affinity by selection against amino acid replacements in the complementarity-determining regions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12917–12921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sanz I. Multiple mechanisms participate in the generation of diversity of human H chain CDR3 regions. J Immunol. 1991;147:1720–1729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Caton AJ, Brownlee GG, Staudt LM, et al. Structural and functional implications of a restricted antibody response to a defined antigenic region on the influenza virus hemagglutinin. Embo J. 1986;5:1577–1587. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04399.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Borretzen M, Chapmen C, Stevenson FK, et al. Structural analysis of VH4-21 encoded human IgM allo- and autoantibodies against red blood cells. Scand J Immunol. 1995;42:90–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1995.tb03630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mariette X, Brouet JC, Danon F, et al. Nucleotide sequence analysis of the VL and VH domains of five human IgM directed to lamin B. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36:1315–1324. doi: 10.1002/art.1780360916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rock EP, Sibbald PR, Davis MM, et al. CDR3 length in antigen-specific immune receptors. J Exp Med. 1994;179:323–328. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.1.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]