Summary

Visual images that convey threatening information can automatically capture attention [1-4]. One example is an object looming in the direction of the observer—presumably because such a stimulus signals an impending collision [5]. A critical question for understanding the relationship between attention and conscious awareness is whether awareness is required for this type of prioritized attentional selection [6]. Although it has been suggested that visual spatial attention can only be affected by consciously perceived events [7], we show that automatic allocation of attention can occur even without conscious awareness of impending threat. We used a visual search task to show that a looming stimulus on a collision path with an observer captures attention but a looming stimulus on a near-miss path does not. Critically, observers were unaware of any difference between collision and near-miss stimuli even when explicitly asked to discriminate between them in separate experiments. These results counter traditional salience-based models of attentional capture, demonstrating that in the absence of perceptual awareness, the visual system can extract behaviorally relevant details from a visual scene and automatically categorize threatening versus non-threatening images at a level of precision beyond our conscious perceptual capabilities.

Experiment 1 Results

Each trial began with a looming stimulus followed by a search display where participants were instructed to quickly locate and discriminate the orientation of a target oval amongst a field of distracting circular discs. Targets and distractors were placed in eight possible positions in a circular array around the point of fixation. Trials varied by (1) path: whether or not the looming stimulus was on a collision path with the boundary of the observer's head, (2) position: whether or not the final position of the looming stimulus coincided with the target oval (versus a distractor disc), and (3) display size: the size of the search array (either 3 or 6 items). Looming stimuli on collision and near-miss paths had the same final positions. This paradigm allowed us to measure the effects of the path of looming stimuli on search rates when their final positions either did or did not coincide with the spatial location of the target oval.

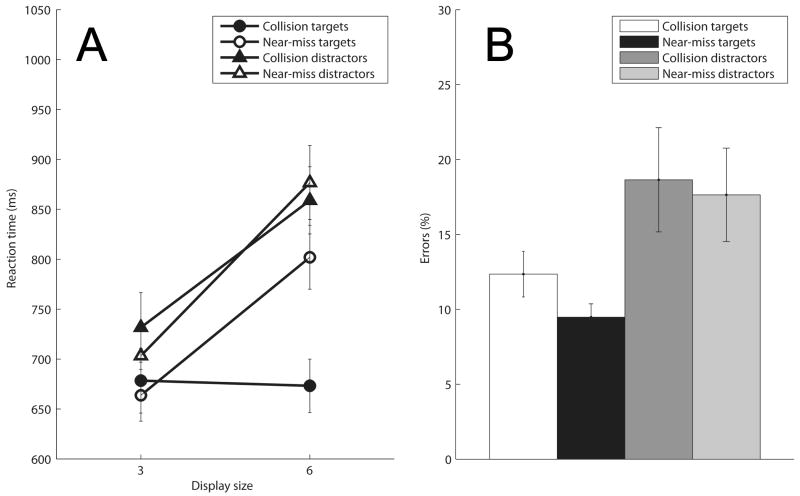

Figure 1A shows mean response times (RT) for trials on which participants correctly determined the orientation of the target oval. Figure 1B shows mean error rates. Individual results for each subject are also available (see Supplemental Data). Increased search efficiency for collision targets (targets at locations that followed looming stimuli on a collision path) was evident in the absolute search times for a set size of six items (128.8 ms difference between collision targets and near-miss targets). Increased search efficiency was also evident in the rate of search as indexed by search slopes: rates of search were fastest for collision targets (-1.7 ms/item), and were much slower for near-miss targets (46.1 ms/item), collision distractors (42.4 ms/item) and near-miss distractors (57.8 ms/item).

Figure 1. Mean correct response times and error rates in Experiment 1.

(A) Collision targets and near-miss targets represent trials where the final position of the looming items coincided with the location of the target ovals. Collision distractors and near-miss distractors represent trials where the final position of the looming item was at a location away from the location of the target oval. Increased search efficiency was evident in the rate of search as indexed by search slopes: rates of search were fastest for collision targets (-1.7 ms/item), and were much slower for near-miss targets (46.1 ms/item), collision distractors (42.4 ms/item) and near-miss distractors (57.8 ms/item). A significant three-way interaction of position, path, and display size (F(2,7) = 7.56, p = 0.019, MSE = 2005.71) indicates significant differences in the slopes across the four path/position combinations. Error bars represent s.e.m.

(B) Error rates for the different conditions of Experiment 1 are presented in Figure 1B. Error bars represent s.e.m.

A repeated-measures ANOVA on RTs from correct trials indicated main effects of looming position (RTs were faster for collision targets than collision distractors, F(1,11) = 29.7, p < 0.0001, MSE = 8080.17), path (RTs were faster for collision targets than near-miss targets, F(1,11) = 8.68, p = 0.013, MSE = 1658.68), and display size (RTs were smaller for set size three than for set size six, F(1,11) = 60.7, p < 0.0001, MSE = 3852.03). A significant three-way interaction of position, path, and display size (F(2,7) = 7.56, p = 0.019, MSE = 2005.71) indicates significant differences in the slopes across the four path/position combinations.

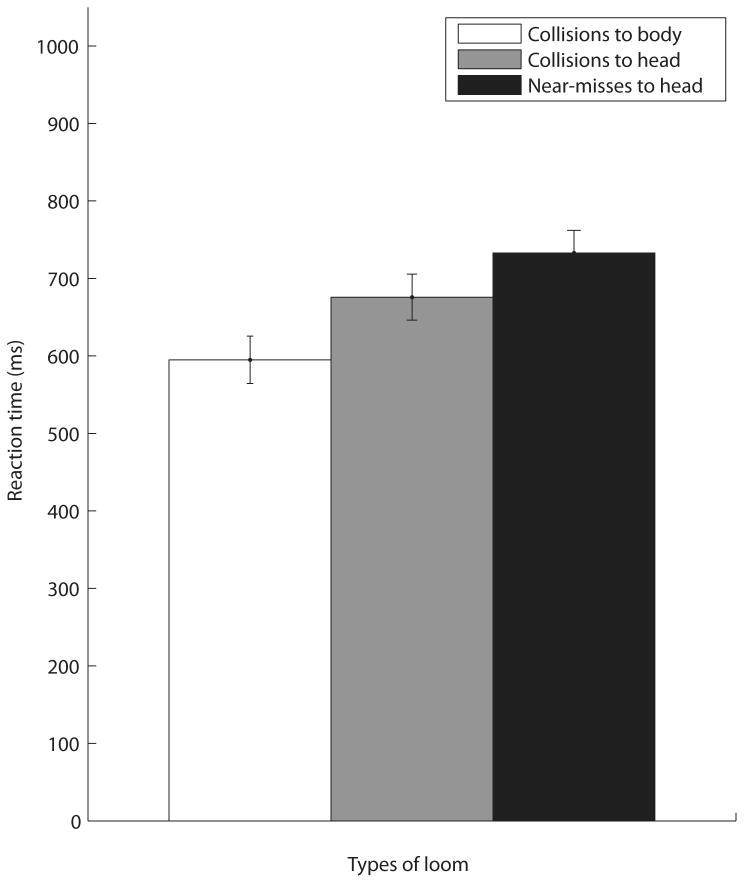

These results show that the location of a looming stimulus that was on a collision course with the subject's head received prioritized attention in the visual search process that followed. Due to the nature of the paradigm, all looming items that originated in the 6 o' clock (downward) location traveled on a path upward towards the observer's body. Figure 2 shows that response times for collision targets at the 6 o'clock position (595.01 ms) were significantly faster than response times for collision targets towards the head (675.94 ms), t(33) = -3.08, p < 0.0001.

Figure 2. Mean correct response times for collisions to the body versus the collisions to the head in Experiment 1.

Body collisions and head collisions represent trials where looming items coincided as the target ovals; body collisions represented looming items that originated from the 6 o' clock location and traveled towards the observer's body, while head collisions represented looming items in every other location that traveled toward the observer's head. Reaction times to body collisions (595.01 ms) were significantly faster than reaction times to head collisions (675.84 ms), t(33) = -3.08, p < 0.0001. Error bars represent s.e.m.

When briefly questioned after the experiment, all participants reported being subjectively unaware of any differences in the trajectories of looming stimuli. Surprisingly, most subjects also reported being able to ignore the looming stimuli since they provided no information about the target detection task and were only present over 125 ms.

Experiment 2 Results

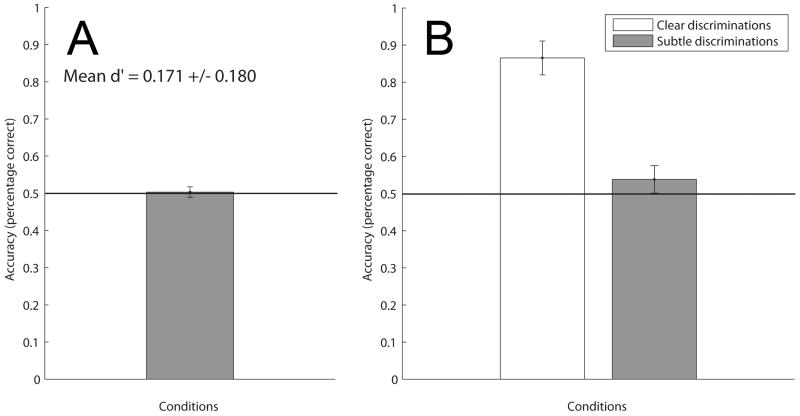

Two versions of a control experiment were conducted to directly test subjects' ability to discriminate between the two looming paths used in Experiment 1. In Experiment 2A the 6 o'clock position was removed because all looming items originating from this location traveled on paths towards the observer's body and were easily identified during pilot testing. The display was otherwise identical to Experiment 1. Participants were instructed to attend to the looming item in each display while fixating at the center and discriminate the trajectory of the looming stimulus as either a collision or a near-miss with their head or body. Figure 3A shows mean accuracy (50.33 +/- 0.0141%) and mean sensitivity (d' = 0.171 +/- 0.180) for discriminating the trajectory of the looming item in each trial. No feedback was provided. Figure S2 shows individual mean accuracies and sensitivity measures (see Supplemental Data, available online, for more details).

Figure 3. Mean accuracies for Experiment 2.

(A) Mean accuracy (50.33 +/- 0.0141%) and mean sensitivity (d′ = 0.171 +/- 0.180) for discriminating the trajectory of the subtle looming items are plotted from the results of Experiment 2A. Participants were instructed to fixate at the center, attend to the looming items and identify whether the looming trajectory was closer to a collision or near-miss with their head. Error bars represent s.e.m (p = 0.001).

(B) Mean accuracy (86.54 +/- 0.0457%) for discriminating between the “clear trajectories” and mean accuracy (53.82 +/- 0.0370%) for discriminating between the “subtle trajectories” used in Experiment 1 are plotted from the results of Experiment 2B. Error bars represent s.e.m. Results suggest that participants understood the task and could discriminate clear collision from miss trajectories; however, participants were unable to categorize the subtle looming trajectories presented in Experiment 1, p < 0.05.

In Experiment 2B, there were four critical additions: (1) we re-introduced the 6 o'clock position, making the displays identical to the displays used in Experiment 1, (2) we implemented two additional trajectories representing a clear miss and clear collision trajectory and randomized them with the subtly different trajectories used in Experiment 1 for a total of four trajectories in the experiment, (3) we added feedback to every trial, and (4) we doubled the number of trials each participant conducted. Given every opportunity to learn this task, the results were surprising. Figure 3B shows mean accuracy (86.54 +/- 0.0457%) for discriminating between the “clear trajectories” and mean accuracy (53.82 +/- 0.0370%) for discriminating between the “subtle trajectories” used in Experiment 1. These results suggest that subjects understood the task and could easily discriminate clear collisions from clear miss trajectories; however, participants were unable to accurately classify the subtly different trajectories presented in Experiment 1.

Discussion

Attentional capture can be operationally defined as speeded search performance that is independent of set size when a nonpredictive stimulus happens to be at the target location. A classic example is a visual onset that is searched with priority, even when it is irrelevant to the main task [8, 9]. Reaction time for detecting a target plotted as a function of the number of distractors can be used as an index for attentional capture: flat search slopes indicate attentional capture and steep slopes a failure to capture attention.

Perceptual saliency is often considered to be a primary factor in determining whether or not a target captures attention [10-12]. Typically, a saliency map is calculated by assigning each visual location a saliency value obtained by the summation of activation values from separate feature maps [13-16]. Indeed, stimulus-driven perceptual saliency models with maps for features such as color, contrast and motion can account for a wide variety of behavioral effects observed in search tasks [17]. However, not all attention-capturing differences between stimuli can be described by saliency models. For example, visual stimuli that convey threatening information can capture attention because of their obvious behavioral relevance, but may share similar features with non-threatening stimuli. In fact, the appearance and behavior of predators in natural environments has typically evolved to minimize visual salience.

To maximize survival, threatening information should quickly and automatically capture attention even when this information is perceptually non-salient. However, traditional perspectives on attentional selection have also suggested that for an event to capture attention, the event needs to be consciously perceived by the observer. For example, there are numerous cases of exogenous cues that enhance sensitivity to visual input at a cued location [18, 19]. We reasoned that not only should threatening information automatically prioritize attention, but may even rely on separate, unique neural processes that are independent of conscious perception [20-23].

Recently, it has been shown that an otherwise uninformative motion stimulus at the target location can capture attention provided it is on a collision path with the observer [3]; however, the two types of looming stimuli used in this previous study traveled in completely opposite directions - either towards fixation or away from fixation - and were thus easily distinguishable. Here, we report a dissociation between attention and awareness in which a looming object on a collision path with the observer captures attention (Experiment 1) even though it is perceptually indistinguishable from a looming stimulus that just misses the observer (Experiment 2). It should be noted that attentional priority was given to a looming stimulus on a collision path only when the looming stimulus coincided with the target oval. Collision or near-miss distractors were equally effective in drawing attention away from stationary target ovals and delaying reaction times. This means that the attentional effects reported here were very specific in spatial location and not a general effect of arousal due to the presence of a threatening stimulus. This spatial specificity shows that this automatic attentional process has spatially-selective detectors and is therefore more sophisticated than a simple general threat-detecting mechanism.

Surprisingly, looming targets from the 6 o' clock position that traveled towards the observer's body produced the fastest response times relative to looming targets that traveled towards the observer's head. This lends support to the idea that attentional capture without awareness is not a binary process, but rather can vary continuously in strength [24]. For some reason, looming stimuli from the 6 o'clock position appears to have the most threatening direction of motion. This is consistent with the idea that relative threat is assessed from a center-of-mass model. It is important to note that when using a manual response paradigm to study the attentional effects of behaviorally relevant stimuli, there is always the possibility of eye saccade influences upon the manual responses. For example, some studies have shown that threatening stimuli only capture attention when presented for 50 ms when using eye saccade measurements, while threatening stimuli only capture attention when presented for 500 ms when using manual responses [25].

Our results have two significant implications for models of visual processing and attention. First, the results extend recent empirical demonstrations of a dissociation between attention and awareness. There are at least three ways in which attention might operate without awareness. First, cues may influence attention by virtue of contingencies between the cue and target for which the subject was unaware. For example, Bartolomeo et al. (2007) demonstrated increased performance in a target detection task utilizing valid cues even though subjects were not explicitly aware that the cues were valid. Second, a target may be processed more effectively by virtue of being attended while the subject remains unaware of it. For example, research has shown that attending to color cues that were rendered invisible through metacontrast masking resulted in enhanced discrimination in a subsequent color discrimination task. [26]. Third, attention may be directed by cues the subject is unaware of. Structurally, such experiments are similar to traditional attention cueing paradigms except that the attentional cues are presented in such a way that subjects are unaware of their presence. For example, Jiang et al. (2006) used inter-ocular suppression to show that “invisible” erotic images that presumably never reach conscious awareness managed to repel or attract attention. Zhaoping (2008) used inter-ocular suppression to show that an eye-of-origin or ocular singleton can attract attention even though observers were unaware that an item was presented to the left eye among background items presented to the right eye. Notably, these previous experiments have relied on rather unnatural stimulus masking manipulations to render the cues invisible. Though our experiment also falls under the category of using a cue the subject is unaware of, our stimuli are unique because our motion cue itself is fully visible. Even though subjects are fully aware of the presence of motion stimuli, differences below discrimination thresholds still produce differential effects on detection.

A second major implication of our results is that they support the influential theory of visual processing that suggests two independent systems within the visual system; one supporting conscious perception while the other unconsciously guiding our actions [27-29]. Evidence for this has typically involved illusions that affect perception but not the sensorimotor systems [30-33] or involved special populations such as patients with posterior cerebral lesions [34]. Intuitively, reacting to threatening stimuli, such as a predator attack, should not require the time-consuming process of consciously identifying the species or identity of the predator. The present study shows that indeed the unconscious action of directing attention to the location of a potentially threatening looming stimulus appears to be automatic and unconscious and is, surprisingly, more accurate at calculating an object's path of motion than the conscious perception pathway.

Methods

Participants

12 undergraduates at the University of Washington (8 females, 4 males) received financial compensation for participating in Experiment 1. 20 undergraduates (12 females, 8 males) received financial compensation for participating in either Experiment 2A or 2B. All reported normal or corrected-to-normal visual acuity and maintained an overall accuracy better than 80%. All subjects gave informed consent to participate in this experiment, which was approved by the University of Washington Human Subjects Institutional Review Board.

Apparatus, stimuli and procedure

Displays were generated in Matlab (Mathworks) using the psychophysics toolbox [35, 36] and were presented on a 51-cm (diagonal) Samsung Syncmaster 1100DF CRT monitor at 1024×768 resolution, refreshed at 60 Hz in a room with no ambient lighting. Participants used a chinrest and sat with their eyes 50 cm from the screen. The background of the displays was gray (15 cd/m2). Display items consisted of discs (4.6 degrees of visual angle) filled with a linear shading gradient that ran from white (30 cd/m2) in the top right to black (0.1 cd/m2) in the bottom left, giving the impression that they were spheres lit from above and to the right.

A video clip of a typical trial is available online (see Supplemental Data). Each trial in Experiment 1 consisted of four stages. (1) The initial preview display lasted 33 ms and consisted of a small fixation dot and a display of three or six spheres in the locations that would be used for the final search display. (2) This was followed by a looming display where a sphere expanded uniformly from a small size (2.1 deg) to the standard sphere size (4.6 deg) in 125 ms across 7 frames of motion (60 frames/sec) towards one of eight locations around the boundaries of the observer's head. Looming stimuli were defined in 3D real-world coordinates and rendered on a monitor 50 cm from the observer using perspective geometry. Looming stimuli were spheres 8 cm in diameter that moved from a distance of 350 cm from the observer to 175 cm from the observer over 125 ms; this motion corresponded with a degree change of 2.1 to 4.6 degrees of visual angle. Looming stimuli that represented a collision with the observer's head had an initial position 6 cm from the center of the monitor (6.9 deg) and the trajectory simulated a point of impact 3 cm from the center of the observer's head. Looming stimuli that represented a near-miss had an initial position 5 cm from the center of the monitor (5.7 deg) and simulated a final impact point 6 cm from the center of the observer's head. At the end of the looming animation, both collision and near-miss stimuli had identical end points 8 cm from the center of the monitor (9.1 deg). Half of the trials displayed a looming item on a path representing a collision with the observer, and the other half of the trials displayed a looming item on a path that represented a near-miss with the observer. The eight final locations of the spheres were positioned evenly around fixation with radii of 9.1 deg (clock positions: 12, 1:30, 3, 4:30, 6, 7:30, 9, and 10:30). (3) This looming motion display was followed by a 16-ms blank screen which was inserted before the presentation of the search display to mask the local pop-out deformation that occurred when the target item transformed from a sphere into an oval. (4) The blank screen was followed by the search display, which remained in view until participants responded or 2000 ms elapsed. In all search displays, a target oval was created by narrowing spheres by 5.5% (from 4.6 to 4.3 deg) along either the horizontal or vertical dimension. Different conditions were counterbalanced and randomized in every block for every participant.

Participants were instructed to search for the oval (while maintaining fixation at the center fixation point) and to discriminate its orientation (vertical or horizontal) as rapidly as possible by pressing one of two keys. A small plus sign (correct), minus sign (incorrect), or circle (no response) provided feedback, and was replaced by a circle to serve as the new fixation point and signal the start of the next display. Participants were informed that every display would have a looming item and a target oval, but that the final location of the looming item provided no information about the location of the target oval. The locations of the looming item and target oval were determined randomly and independently in every trial such that the looming item and the target oval coincided at the same location every 1/n trials (with “n” being the display size of either three or six). Participants were instructed to respond as quickly as possible while maintaining an accuracy of at least 80%. Prior to testing, participants received 54 practice trials. Each participant was tested for a total of 540 trials, in 5 blocks of 108 trials. Blocks were separated by brief breaks.

For Experiment 2A, looming stimuli from the 6 o'clock position were removed due to the fact that all looming stimuli from this location were classified as collisions in pilot testing; displays were otherwise identical to those in Experiment 1. Participants were told that each display contained one of two types of looming items—collision looms that would travel a path towards a collision with their head or body and miss looms that would travel a wider path and miss their head or body. Participants were then instructed to fixate at the center, attend to the looming items and report which type of looming stimulus was displayed in the trial. Conditions were randomized in every block and feedback was not provided in this version of the experiment. Prior to testing, participants received 54 practice trials, and each participant was tested for a total of 216 trials, in two blocks of 108 trials.

For Experiment 2B, the displays were identical to those used in Experiment 1. Critically, two trajectories clearly representing a collision and a miss were added to the displays and randomized with the subtle trajectories used in Experiment 1. Collision stimuli in Experiment 2B simulated points of impact of 1 cm and 3 cm from the center of the observer's head while miss stimuli simulated points of impact of 6 cm and 12 cm from the center of the observer's head. In addition, feedback was provided in this experiment. The task was identical to the task in Experiment 2A. Prior to testing, participants received 54 practice trials. Each participant was tested for twice the number of trials as the participants in Experiment 2A for a total of 432 trials, in 2 blocks of 216 trials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ione Fine and Sung Jun Joo for helpful discussion. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant EY12925.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Jeffrey Y. Lin, Email: jytlin@u.washington.edu.

Scott O. Murray, Email: somurray@u.washington.edu.

Geoffrey M. Boynton, Email: gboynton@u.washington.edu.

References

- 1.Ball W, Tronick E. Infant responses to impending collision: optical and real. Science. 1971;171:818–820. doi: 10.1126/science.171.3973.818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koster EH, Crombez G, Van Damme S, Verschuere B, De Houwer J. Does imminent threat capture and hold attention? Emotion. 2004;4:312–317. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.4.3.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin JY, Franconeri S, Enns JT. Objects on a collision path with the observer demand attention. Psychol Sci. 2008;19:686–692. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schiff W, Caviness JA, Gibson JJ. Persistent fear responses in rhesus monkeys to the optical stimulus of “looming”. Science. 1962;136:982–983. doi: 10.1126/science.136.3520.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Franconeri SL, Simons DJ. Moving and looming stimuli capture attention. Percept Psychophys. 2003;65:999–1010. doi: 10.3758/bf03194829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koch C, Tsuchiya N. Attention and consciousness: two distinct brain processes. Trends Cogn Sci. 2007;11:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanai R, Tsuchiya N, Verstraten FA. The scope and limits of top-down attention in unconscious visual processing. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2332–2336. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yantis S, Jonides J. Abrupt visual onsets and selective attention: evidence from visual search. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform. 1984;10:601–621. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.10.5.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yantis S, Jonides J. Abrupt visual onsets and selective attention: voluntary versus automatic allocation. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform. 1990;16:121–134. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.16.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Itti L, Koch C. A saliency-based search mechanism for overt and covert shifts of visual attention. Vision Res. 2000;40:1489–1506. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(99)00163-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Itti L, Koch C. Computational modelling of visual attention. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:194–203. doi: 10.1038/35058500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenholtz R. A simple saliency model predicts a number of motion popout phenomena. Vision Res. 1999;39:3157–3163. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(99)00077-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Julesz B. Textons, the elements of texture perception, and their interactions. Nature. 1981;290:91–97. doi: 10.1038/290091a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koch C, Ullman S. Shifts in selective visual attention: towards the underlying neural circuitry. Hum Neurobiol. 1985;4:219–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Treisman AM, Gelade G. A feature-integration theory of attention. Cognit Psychol. 1980;12:97–136. doi: 10.1016/0010-0285(80)90005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolfe JM, Cave KR, Franzel SL. Guided search: an alternative to the feature integration model for visual search. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform. 1989;15:419–433. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.15.3.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duncan J, Humphreys GW. Visual search and stimulus similarity. Psychol Rev. 1989;96:433–458. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.96.3.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakayama K, Mackeben M. Sustained and transient components of focal visual attention. Vision Res. 1989;29:1631–1647. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(89)90144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Posner MI. Orienting of attention. Q J Exp Psychol. 1980;32:3–25. doi: 10.1080/00335558008248231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Esteves F, Parra C, Dimberg U, Ohman A. Nonconscious associative learning: Pavlovian conditioning of skin conductance responses to masked fear-relevant facial stimuli. Psychophysiology. 1994;31:375–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1994.tb02446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ohman A, Soares JJ. Emotional conditioning to masked stimuli: expectancies for aversive outcomes following nonrecognized fear-relevant stimuli. J Exp Psychol Gen. 1998;127:69–82. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.127.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pessoa L. To what extent are emotional visual stimuli processed without attention and awareness? Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15:188–196. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Regan D, Vincent A. Visual processing of looming and time to contact throughout the visual field. Vision Res. 1995;35:1845–1857. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(94)00274-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jonides J, Irwin DE. Capturing attention. Cognition. 1981;10:145–150. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(81)90038-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bannerman RL, Milders M, de Gelder B, Sahraie A. Orienting to threat: faster localization of fearful facial expressions and body postures revealed by saccadic eye movements. Proc Biol Sci. 2009;276:1635–1641. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kentridge RW, Nijboer TC, Heywood CA. Attended but unseen: visual attention is not sufficient for visual awareness. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46:864–869. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Georgeson M. Vision and action: you ain't seen nothin' yet. Perception. 1997;26:1–6. doi: 10.1068/p260001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Milner AD, Goodale MA. Visual pathways to perception and action. Prog Brain Res. 1993;95:317–337. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)60379-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Milner AD, Goodale MA. The visual brain in action. 2nd. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aglioti S, DeSouza JF, Goodale MA. Size-contrast illusions deceive the eye but not the hand. Curr Biol. 1995;5:679–685. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00133-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bridgeman B. Cognitive factors in subjective stabilization of the visual world. Acta Psychol (Amst) 1981;48:111–121. doi: 10.1016/0001-6918(81)90053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daprati E, Gentilucci M. Grasping an illusion. Neuropsychologia. 1997;35:1577–1582. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(97)00061-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haffenden AM, Goodale MA. The effect of pictorial illusion on prehension and perception. J Cogn Neurosci. 1998;10:122–136. doi: 10.1162/089892998563824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Newcombe F, Ratcliff G, Damasio H. Dissociable visual and spatial impairments following right posterior cerebral lesions: clinical, neuropsychological and anatomical evidence. Neuropsychologia. 1987;25:149–161. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(87)90127-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brainard DH. The Psychophysics Toolbox. Spat Vis. 1997;10:433–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pelli DG. The VideoToolbox software for visual psychophysics: transforming numbers into movies. Spat Vis. 1997;10:437–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhaoping L. Attention capture by eye of origin singletons even without awareness--a hallmark of a bottom-up saliency map in the primary visual cortex. J Vis. 2008;8(1):1–18. doi: 10.1167/8.5.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jiang Y, Costello P, Fang F, Huang M, He S. A gender- and sexual orientation-dependent spatial attentional effect of invisible images. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17048–17052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605678103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bartolomeo P, Decaix C, Sieroff E. The phenomenology of endogenous orienting. Conscious Cogn. 2007;16:144–161. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.