Abstract

Diets high in trans fats are associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and components of the metabolic syndrome. The influence of these toxic fatty acids on the development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease has not been significantly examined. Therefore, we sought to compare the effect of a murine diet high in trans fat to a standard high-fat diet that is devoid of trans fats but high in saturated fats. Male AKR/J mice were fed a calorically identical trans fat diet or standard high-fat diet for 10 days, 4 wk, and 8 wk. Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), lipid, insulin, and leptin levels were determined and the quantitative insulin-sensitivity check index (QUICKI) was calculated as a measure of insulin resistance. Additionally, hepatic triglyceride content and gene expression of several proinflammatory genes were assessed. By 8 wk, trans fat-fed mice exhibited higher ALT values than standard high-fat-fed mice (126 ± 16 vs. 71 ± 7 U/l, P < 0.02) despite similar hepatic triglyceride content at each time point. Trans fat-fed mice also had increased insulin resistance compared with high-fat-fed mice at 4 and 8 wk with significantly higher insulin levels and lower QUICKI values. Additionally, hepatic interleukin-1β (IL-1β) gene expression was 3.6-fold higher at 4 wk (P < 0.05) and 5-fold higher at 8 wk (P < 0.05) in trans fat-fed mice compared with standard high-fat-fed mice. Trans fat feeding results in higher ALT values, increased insulin resistance, and elevated IL-1β levels compared with standard high-fat feeding.

Keywords: elaidic acid; nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, interleukin-1β; quantitative insulin-sensitivity check index, trans fat

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common cause of liver disease in the United States with an estimated prevalence of 6–14% (10). NAFLD describes a range of disease, from simple steatosis to fibrosing steatohepatitis that can progress to cirrhosis. NAFLD is associated with insulin resistance, central adiposity, dyslipidemia, and hypertension and is considered by many to be the hepatic manifestation of the metabolic syndrome (10, 31, 39).

Trans fats are a form of unsaturated fats that are relatively rare in nature but are present in abundance in “fast food” and many processed foods that are excessively consumed in developed nations. Trans fats differ from the majority of unsaturated fatty acids because of a double bond in the “trans” configuration instead of the standard “cis” configuration. This structural change results in a fatty acid species that is straighter and more closely resembles the structure of a saturated fatty acid. This structural change is thought to play a particularly important role in the toxicity of trans fats (41). The major source of trans fats in our diet is from the partial hydrogenation of vegetable oils, which is an industrial process used to convert oils into semisolid fats for use in baked goods, deep-fried fast foods, and margarines. Consumption of just one or two servings of these products can often exceed the recommended daily intake of trans fats. Trans fats account for ∼2–3% of total calories consumed by Americans, but it has been recommended that intake be no greater than 1% of total calorie consumption (2, 35).

Trans fat consumption is associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease (5, 36, 37). Additionally, trans fats may exacerbate diabetes, as suggested by increased insulin resistance in trans fat-fed rodents, although data linking trans fats to diabetes in humans are conflicting (16, 18, 34, 51). Insulin resistance and vascular disease are commonly found in persons with NAFLD, and these diseases share common risk factors. Several recent studies have demonstrated an increase in cardiovascular events in patients with NAFLD independent of conventional risk factors (4, 13, 19, 49). Although consumption of a high-fat diet by rodents leads to the development of experimental fatty liver disease, the specific importance of trans fats on either experimental or human fatty liver disease has not been previously addressed. Therefore, we sought to compare the effect of a trans fat diet consisting primarily of trans-18:1, n-6, the species found in greatest abundance in trans fats consumed from industrial sources, with a calorically identical standard high-fat (trans fat-free) diet on the development of experimental fatty liver disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and experimental protocol.

Male AKR/J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME), and mice were 9–10 wk of age at the start of each experiment. Animals were housed in a temperature-controlled room (22°C) with 14-h light:10-h dark cycling and fed Harlan Teklad chow (Madison, WI) prior to experimentation, with free access to food and water. Mice were administered either a trans fat, standard high-fat, or control diet (Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ) for 10 days (n = 6–8 per group), 4 wk (n = 5–6 per group), or 8 wk (n = 4–5 per group). Separate cohorts of mice were used for each experimental time point.

The high-fat and trans fat diets were calorically identical; both consisting of 20 kcal% protein, 35 kcal% carbohydrate, and 45 kcal% total fat (Table 1). The diets differed in their content of trans fatty acids: the high-fat diet contained no trans fats, whereas the trans fat diet contained 20 kcal% trans fat; the most common species of trans fat was trans-18:1, n-6 (elaidic acid). The fatty acid composition of the diets has been provided by Research Diets and can be found in Supplemental Table S1. The source of fat for the standard high-fat diet was lard, whereas the source of fat for the trans fat diet was shortening. The ratio of polyunsaturated to saturated fatty acids was identical between the trans fat and standard high-fat diet (Table 1). All diets were low in cholesterol, and the cholesterol content (wt/wt) of the control diet, the standard high-fat diet, and the trans fat diet was 0.01, 0.02, and 0.01%, respectively. The control diet contained 20 kcal% protein, 70 kcal% carbohydrate, and 10 kcal% fat with no trans fats. After completion of 10 days, 4 wk, or 8 wk on an experimental diet, mice were fasted for 4 h and euthanized by CO2 narcosis. Blood was obtained by cardiac puncture and livers were removed and weighed. A portion of liver was fixed in 10% formalin for histological analysis, and the remainder was frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C until further analysis. Protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees, and euthanasia was consistent with recommendations of the American Veterinary Medical Association.

Table 1.

Diet compositions

| Control Diet, kcal % | Standard High-Fat Diet, kcal % | Trans-Fat Diet, kcal % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Carbohydrate | 70 | 35 | 35 |

| Overall fat | 10 | 45 | 45 |

| Saturated | 2.5 | 16.2 | 10 |

| Polyunsaturated | 4 | 8.6 | 4.5 |

| PUFA-to-SFA ratio | 1.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Monounsaturated (Cis-) | 3.5 | 20.3 | 10.5 |

| Trans- | 20 |

PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acids; SFA, saturated fatty acids.

Determination of chemistry and hormone levels.

Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels were determined using a spectrophotometric kit purchased from Biotron Diagnostics (Hemet, CA). Serum and hepatic triglyceride levels were determined using a spectrophotometric assay kit purchased from Thermo Electron (Louisville, CO). Protein concentration of liver homogenate was determined with a Coomassie assay reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL) and BSA as a standard. Liver triglyceride content was normalized to the protein content of the homogenate. Serum insulin, leptin, and hepatic interleukin-1β (IL-1β) levels were analyzed with multiwell plates purchased from Meso Scale Discovery (MSD) (Gaithersburg, MD), utilizing the SECTOR Imager 2400 (MSD), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Liver was homogenized in lysis buffer (pH 7.4, 50 mM Tris·HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 25 mM EDTA, 5 mM EGTA, 0.25% Na-deoxycholate, 1% Igepal-630, 0.5 mM DTT, 1% BSA) for determination of hepatic IL-1β levels. Fasting glucose levels were determined using a reflectance glucometer (One Touch II, Lifescan, CA). Quantitative insulin-sensitivity check index (QUICKI) was calculated as a measure of insulin sensitivity; QUICKI = 1/[log (fasting insulin) + log(fasting glucose)].

Fast-protein liquid chromatography and serum cholesterol.

Serum lipoproteins were fractionated with an AKTA fast-protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) system by using equal volumes of pooled plasma from mouse cohorts on tandem Superose 6 FPLC columns (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). The columns were then eluted with 200 mmol/l sodium phosphate (pH 7.4), 50 mmol/l NaCl, 0.03% (wt/vol) EDTA, and 0.02% (wt/vol) sodium azide at a flow rate of 0.4 ml/min. The content of cholesterol in the eluted fractions was measured with a microplate assay technique. The cholesterol of the serum and of the eluted fractions was determined with an enzymatic assay reagent kit (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Apo B-100 levels of pooled LDL fractions were determined by using rabbit polyclonal antibodies (1:500) directed against mouse apoB-100 (Biodesign International, Saco, ME) as described previously (40).

Quantitative real-time PCR.

RNA was isolated from livers by using Trizol reagent purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). First strand cDNA synthesis was performed by reverse transcription of 2 μg of total RNA with an iScript cDNA synthesis kit from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA). Real-time PCR was performed using 2 μl of the total cDNA in a 25-μl reaction containing QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) (primer sequences listed in Table 2). Amplification was performed in duplicate for each sample in an Applied Biosystems 7300 Sequence Detector (Foster City, CA) and the amount of mRNA was normalized with GAPDH used as the endogenous control.

Table 2.

Primers for quantitative real-time PCR

| Forward Primer | Reverse Primer | |

|---|---|---|

| IL-1β | 5′-CCA GCA TGA GGA CAT GAG CAC-3′ | 5′-TTC TCT GCA GAC TCA AAC TCC AC-3′ |

| IL-6 | 5′-TAG TCC TTC CTA CCC CAA TTT CC-3′ | 5′-TTG GTC CTT AGC CAC TCC TTC-3′ |

| TNF-α | 5′-CTG GGA CAG TGA CCT GGA CT-3′ | 5′-GCA CCT CAG GGA AGA GTC TG-3′ |

| IL-10 | 5′-CAC AAA GCA GCC TTG CAG AA-3′ | 5′-AGA GCA GGC AGC ATA GCA GTG-3′ |

| SOCS-1 | 5′-TCC GAT TAC CGG CGC ATC ACG-3′ | 5′-CTC CAG CAG CTC GAA AAG GCA-3′ |

| SOCS-3 | 5′-CAC AGC AAG TTT CCC GCC GCC-3′ | 5′-GTG CAC CAG CTT GAG TAC ACA-3′ |

| GAPDH | 5′-ACC ACC ATG GAG AAG GCC GG-3′ | 5′-CTC AGT GTA GCC CAA GAT GC-3′ |

Statistical analysis.

Data are presented as means ± SE. Comparisons between groups were performed with one-way ANOVA and the Holm-Sidak method for multiple pairwise comparisons. SigmaStat 3.0 was utilized to calculate results, and significance was defined as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

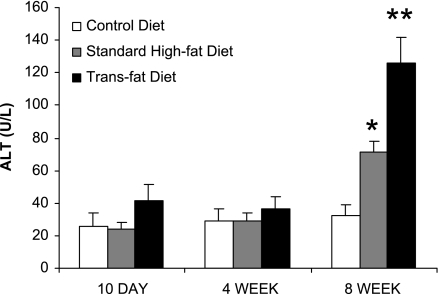

Trans fat-fed mice have higher ALT values compared with standard high-fat-fed mice after 8 wk.

There were no differences in serum ALT values between any of the groups at 10 days or 4 wk, but after 8 wk both trans fat-fed and standard high-fat-fed mice had significantly higher ALT values compared with mice on the control diet (Fig. 1). At 8 wk, the trans fat group also had a significantly higher ALT value than the high-fat group (126 ± 16 vs. 71 ± 7 U/l, P < 0.05). No significant histological differences were noted between the high-fat and trans fat groups. After 8 wk on the diet both groups demonstrated significant steatosis compared with the control group, but there was no inflammatory infiltrate or fibrosis identified in either group.

Fig. 1.

Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) values. At 10 days and 4 wk there was no significant difference in the ALT values between the groups. At 8 wk, the trans fat group had higher ALT values compared with both the standard high-fat and control diet group (*P < 0.05 vs. control diet; **P < 0.05 vs. standard high-fat diet and control diet).

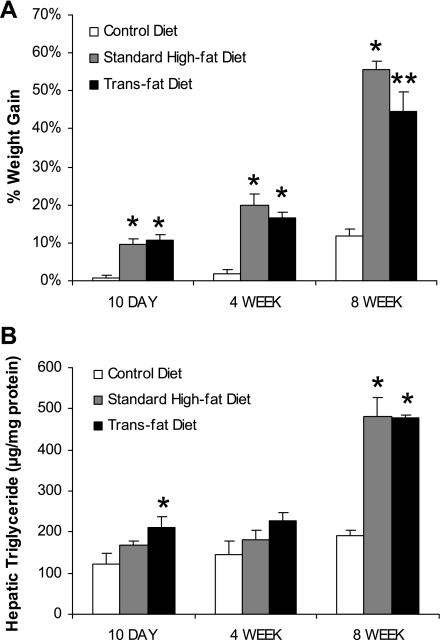

Trans fat-fed mice gained less weight after 8 wk compared with standard high-fat-fed mice but had a similar increase in hepatic steatosis.

After 10 days, 4 wk, and 8 wk on their respective diets, the standard high-fat and trans fat-fed mice both had increased weight gain compared with the mice fed the control diet. However, by 8 wk the high-fat-fed mice had gained more weight than the trans fat-fed mice (Fig. 2A). After 8 wk, the high-fat and trans fat groups had a similar increase in hepatic triglyceride content and both groups had significantly higher hepatic triglyceride content than the control group (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Weight gain and liver steatosis. A: after 10 days, 4 wk, and 8 wk of feeding both trans fat and standard high-fat groups had a greater weight increase compared with the control group. At 8 wk the high-fat group gained more weight than the trans fat group (*P < 0.05 vs. control diet, **P < 0.05 vs. standard high-fat diet and control diet). B: at 8 wk the trans fat and high-fat groups had significantly greater triglyceride content compared with the control diet group (*P < 0.05 vs. control diet).

Serum cholesterol and triglyceride levels in trans fat-fed mice and standard high-fat-fed mice.

Serum cholesterol levels of the high-fat-fed mice were higher than the trans fat-fed mice after 10 days but were not statistically different than the control group (Table 3). After 4 wk and 8 wk of feeding, cholesterol levels were higher in the standard high-fat-fed mice compared with control, but there was no significant difference in the trans fat-fed group compared with the high-fat or control group. Lipoprotein analysis was performed with FPLC and the majority of cholesterol in all groups was high-density lipoprotein (HDL). Levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol were very low and similar in all groups and there did not appear to be any difference in the amount of apoB-100 in the LDL fraction, suggesting no substantial alteration in the density of LDL particles (Supplemental Fig. S1). Serum triglyceride levels were similar between the trans fat and high-fat group at each time point (Table 3).

Table 3.

Serum cholesterol and triglyceride

| Control Diet | Standard High-Fat Diet | Trans-Fat Diet | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cholesterol, mg/dl) | |||

| 10 day | 95±6 | 113±8 | 83±5* |

| 4 wk | 85±3 | 108±7† | 94±2 |

| 8 wk | 79±4 | 100±5† | 93±2 |

| Triglyceride, mg/dl) | |||

| 10 day | 105±6 | 112±6 | 116±9 |

| 4 wk | 86±4 | 96±1 | 124±14 |

| 8 wk | 123±9 | 128±6 | 127±12 |

Values are means ± SE (P < 0.05)

trans-fat vs. standard high-fat,

standard high-fat vs. control diet.

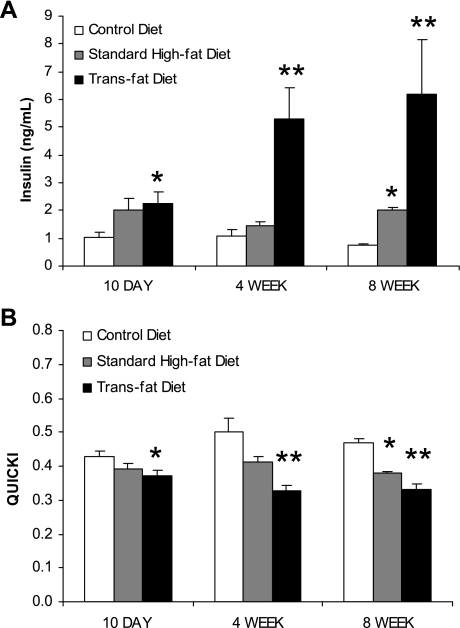

Trans fat-fed mice demonstrate more insulin resistance than high-fat-fed mice.

Fasting insulin levels of the trans fat-fed mice were higher than those of the control diet-fed mice at each time point and after 8 wk of feeding the standard high-fat-fed mice also had significantly higher insulin levels than the control group. At 4 wk and 8 wk, trans fat feeding resulted in significantly higher fasting insulin levels compared with standard high-fat feeding (4 wk: 5.3 ± 1.2 vs. 1.4 ± 0.2 ng/ml, P < 0.05; 8 wk: 6.2 ± 2.0 vs. 2.0 ± 0.1 ng/ml, P < 0.05) (Fig. 3A). Although there was a trend toward higher glucose levels in the standard high-fat and trans fat groups compared with control, this did not reach statistical significance and there were no significant differences between the trans fat and standard high-fat groups. At 8 wk, the serum glucose levels were 188 ± 13, 215 ± 6, and 215 ± 6 mg/dl in the control, standard high-fat, and trans fat groups, respectively. QUICKI determinations were made based on the fasting glucose and insulin levels at each time point. Although QUICKI determinations were lower in the high-fat group than in the mice fed the control diet, consistent with greater insulin resistance, this only reached statistical significance at 8 wk. The trans fat-fed group, however, demonstrated significantly more insulin resistance at each time point compared with the mice on the control diet. At 4 wk and 8 wk the trans fat-fed mice also demonstrated significantly more insulin resistance compared with the mice on the standard high-fat diet (4 wk: 0.32 ± 0.01 vs. 0.41 ± 0.01, P < 0.05; 8 wk: 0.33 ± 0.02 vs. 0.38 ± 0.00, P < 0.05) (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Serum insulin levels and quantitative insulin-sensitivity check index (QUICKI) values. A: fasting insulin levels of the trans fat group were significantly higher than the standard high-fat group at 4 wk and 8 wk. Both groups had higher insulin levels than the control diet group at 10 days and 8 wk (*P < 0.05 vs. control diet, **P < 0.05 vs. standard high-fat diet and control diet). B: QUICKI values were determined with fasting insulin and glucose levels. The trans fat group demonstrated more insulin resistance compared with the high-fat group at 4 wk and 8 wk. At each time point the trans fat group demonstrated more insulin resistance than the control diet group (*P < 0.05 vs. control diet, **P < 0.05 vs. standard high-fat diet and control diet).

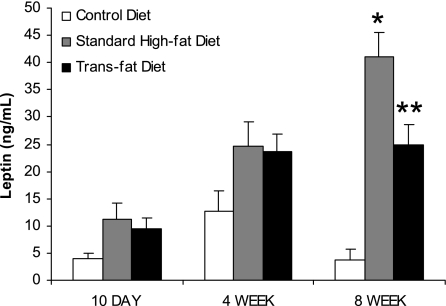

Trans fat-fed mice demonstrate altered leptin levels at 8 wk.

Serum leptin levels were determined at each time point (Fig. 4). Both standard high-fat feeding and trans fat feeding resulted in higher leptin levels at each time point compared with control diet feeding; however, this only reached significance at 8 wk. Additionally, at 8 wk serum leptin was significantly lower in the trans fat-fed mice compared with the high-fat-fed mice (24.8 ± 3.7 vs. 41.0 ± 4.5 ng/ml, P < 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Serum leptin levels. Leptin levels were higher in the trans fat and standard high-fat groups compared with control at 8 wk. At 8 wk, the trans fat group also demonstrated lower leptin levels than the high-fat group (*P < 0.05 vs. control diet, **P < 0.05 vs. standard high-fat diet and control diet).

Trans fat-fed mice demonstrate significantly increased hepatic IL-1β gene expression as well as increased hepatic IL-1β levels.

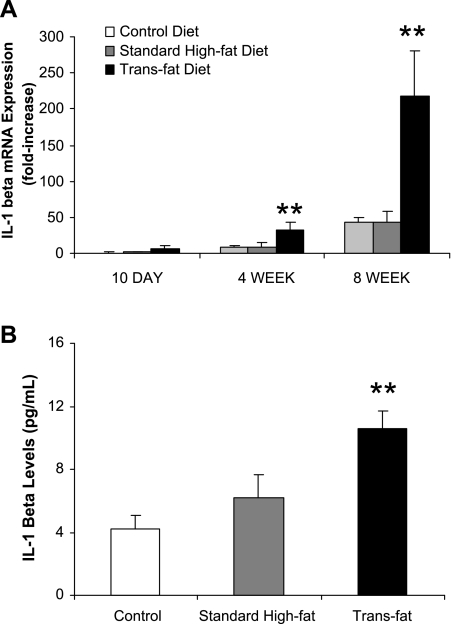

Hepatic gene expression of several pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines was determined by quantitative real-time PCR. IL-1β gene expression increased with time in each experimental group. At 4 wk and 8 wk there was a significant elevation in hepatic IL-1β gene expression in the trans fat-fed mice relative to both the high-fat-fed mice and the mice fed the control diet (Fig. 5A). Hepatic IL-1β gene expression of the trans fat-fed mice was 3.6-fold higher at 4 wk (P < 0.05) and 5-fold higher at 8 wk (P < 0.05) compared with standard high-fat-fed mice. The increase in hepatic gene expression of IL-1β was accompanied by increased hepatic IL-1β protein levels at 8 wk (Fig. 5B). Gene expression of additional cytokines and factors implicated in NAFLD and insulin resistance were also determined [tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-10 (IL-10), suppressor of cytokine signaling-1 (SOCS-1), and suppressor of cytokine signaling-3 (SOCS-3)]. No substantial trends were identified in the other genes analyzed related to time course or between the groups (Table 4).

Fig. 5.

Hepatic IL-1β gene expression and levels. A: IL-1β gene expression increased within each group over time. At 4 wk and 8 wk, IL-1β expression was significantly higher in the trans fat group (**P < 0.05 vs. standard high-fat diet and control diet). There was no significant difference between the high-fat and control diet groups at any time point. B: IL-1β levels were determined and found to be significantly higher in the trans fat group compared with the high-fat group at 8 wk (**P < 0.05 vs. standard high-fat diet and control diet).

Table 4.

Hepatic cytokine gene expression

| Control Diet | Standard High-Fat Diet | Trans-Fat Diet | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α | |||

| 10 day | 1.0±0.1 | 1.9±0.4 | 2.1±0.3 |

| 4 wk | 3.0±0.6d | 2.9±0.8 | 2.1±0.2 |

| 8 wk | 2.2±0.2 | 4.3±0.6c,e | 3.9±0.3e,f |

| IL-6 | |||

| 10 day | 1.0±0.1 | 1.8±0.2c | 1.2±0.2 |

| 4 wk | 8.2±1.1 | 4.8±0.8c,d | 2.9±0.4b,d |

| 8 wk | 0.7±0.1f | 1.3±0.4f | 1.1±0.1f |

| IL-10 | |||

| 10 day | 1.0±0.1 | 1.4±0.2 | 0.9±0.1a |

| 4 wk | 1.8±0.2d | 1.2±0.2 | 0.9±0.1 |

| 8 wk | 0.6±0.1f | 1.3±0.3 | 0.8±0.2 |

| SOCS-1 | |||

| 10 day | 1.0±0.1 | 1.5±0.2 | 1.7±0.2b |

| 4 wk | 1.1±0.2 | 0.8±0.2 | 1.2±0.1 |

| 8 wk | 1.2±0.2 | 1.6±0.2 | 1.0±0.1e,a |

| SOCS-3 | |||

| 10 day | 1.0±0.2 | 1.8±0.6 | 1.6±0.5 |

| 4 wk | 0.5±0.1 | 0.5±0.2 | 1.0±0.2 |

| 8 wk | 0.5±0.1 | 0.9±0.2 | 0.5±0.0 |

Values are means ± SE (P < 0.05)

trans-fat vs. standard high-fat,

trans-fat vs. control diet,

standard high-fat vs. control diet,

4 wk vs. 10 day,

8 wk vs. 10 day,

8 wk vs. 4 wk.

DISCUSSION

Although trans fats have been linked with coronary heart disease, dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance, the specific impact of trans fats on the liver has not been well studied (5, 16, 18, 34, 36, 37, 51). These experiments demonstrate that mice fed a trans fat diet have increased insulin resistance and higher ALT levels compared with mice fed a standard experimental high-fat diet. This occurs despite developing a similar degree of obesity and hepatic steatosis. These observations are accompanied by a substantial increase in IL-1β gene expression and IL-1β cytokine levels in the liver. The increased insulin resistance and more dramatic ALT elevation observed in the trans fat-fed mice suggests this model may translate better to human fatty liver disease than the standard high-fat diet.

Insulin resistance is critical to the development of NAFLD, and the severity of insulin resistance correlates with more advanced liver disease (12, 15, 47). A diet high in saturated fats and low in polyunsaturated fats has been associated with increased insulin resistance. However, there is conflicting evidence regarding the influence of dietary trans fats on the development of insulin resistance and whether they lead to more insulin resistance compared with saturated fats (16, 17). Ibrahim et al. (18) demonstrated that replacing 2% of energy from saturated fatty acids and 1% from cis-monounsaturated fatty acids with 3% trans fats resulted in ∼17% higher fasting insulin levels and reduced adipocyte insulin sensitivity in rats. They also showed that trans fats reduced the adipocyte membrane fluidity and suggested this as a possible mechanism of increased insulin resistance in their model. Alstrup et al. (3) also showed that the trans-conformations of 18:1delta-9 and 18:1delta-11 fatty acids led to significantly higher insulin output from isolated mouse islet cells compared with their cis-configurations.

In our experiments, trans fat-fed mice became obese and demonstrated higher insulin levels and more insulin resistance than mice fed a calorically identical diet high in saturated fats. Large human observational studies have examined the association between trans fat intake and the risk of diabetes. The largest study, the Nurses' Health Study, determined that intake of trans fats was an independent risk factor for developing diabetes (43). Two other studies, however, found no direct association between trans fat intake and the risk of diabetes (34, 52). In addition to having the largest sample size, strengths of the Nurses' Health Study were its adjustment for the types of fat ingested and a reported intake of trans fats more consistent with previous dietary studies (2, 14). There have been only a few randomized studies in a small number of patients comparing consumption of meals high in trans fats, monounsaturated fats, or saturated fats on the development of insulin resistance. Two studies found no difference in postprandial insulin levels between subjects that consumed a high-trans fat meal vs. a meal high in cis-monounsaturated fats; however, these studies involved healthy, lean subjects (28, 29). In the two studies that have been performed with obese subjects, one of which included diabetic subjects, greater elevations in postprandial insulin levels were demonstrated in meals containing trans fats compared with meals containing cis-monounsaturated fats (8, 25).

Relationships between the inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-10 and the SOCS-1 and SOCS-3 with insulin resistance are well described (9, 21, 22, 24, 44, 45, 50). Systemically administered IL-1β has been shown to increase hepatic gluconeogenesis; however, the link between IL-1β and insulin resistance has been primarily characterized in adipocytes and pancreatic islet beta cells (20, 23, 26, 30). In our experiments, the marked increase in hepatic IL-1β gene expression at 4 wk and 8 wk, in addition to the significantly higher hepatic IL-1β levels at 8 wk in the trans fat-fed group, suggests a role for IL-1β in the higher ALT and increased insulin resistance observed. In humans, genetic polymorphisms in IL-1β have been reported to be associated with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes in North Indians and also associated with an increased risk of the metabolic syndrome in those with low polyunsaturated fat intake (1, 46). TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10, SOCS-1, and SOCS-3 have also been implicated as links between inflammation and insulin resistance, but there were no significant differences observed in mice fed the trans fat diet.

Leptin levels were greater in the standard high-fat and trans fat groups, but only after 8 wk were they significantly greater than the control group. Leptin levels in the trans fat group, however, remained lower than the standard high-fat group. Leptin levels mirrored percent weight gain and may parallel overall body fat mass. Whereas hepatic fat content was found to be identical between the trans fat and high-fat groups, we cannot exclude the possibility that the fat distribution was different between the groups. The interplay between leptin and insulin is quite complex. Insulin has been shown to directly increase leptin secretion; however, leptin has also been demonstrated to decrease insulin production and the lower leptin levels at 8 wk may have contributed to the higher insulin levels observed in the mice fed the trans fat diet (7, 42). Two studies have directly examined the influence of trans fat consumption on leptin levels. Bray et al. (6) showed unchanged leptin levels in overweight men who ingested a single meal high in trans fats compared with calorically identical meals that were devoid of trans fats. This study, however, involved only a single feeding. Another study demonstrated that rats fed a diet high in trans fats while pregnant and during lactation resulted in significantly lower leptin levels of their offspring despite similar body weights and increased adipose content compared with a control group (38).

Differences in serum cholesterol appear to primarily be related to an increased HDL fraction in the high-fat-fed group relative to the trans fat and control diet groups. Although it is possible that trans fat feeding results in lower HDL levels compared with standard high-fat feeding, the small difference in cholesterol content of the diets limits the conclusions one can draw from this finding. The cholesterol content was low in all of the diets and there was no additional cholesterol added to the diets, but there was a slightly greater amount of cholesterol in the standard high-fat diet compared with the trans fat and control diets. This difference was due to the source of fat used in the diets: lard (i.e., animal) for the high-fat compared with vegetable for the trans fat.

One of the known limitations of the standard high-fat diet model of NAFLD is its lack of histological evidence of inflammation or fibrosis in mice despite the development of steatosis and insulin resistance. We have also performed an experiment feeding mice trans fats and a standard high-fat diet for up to 6 mo, which did not result in any liver fibrosis. The purpose of our experiment was to compare the effect of trans fats to that of saturated fats on the liver. Although feeding mice a trans fat diet for 8 wk does not invoke progressive steatohepatitis, it does result in a more pronounced elevation of ALT and insulin resistance, sine qua nons of human fatty liver disease.

NAFLD is an independent predictor of cardiovascular disease, even after controlling for other features of the metabolic syndrome (13, 48, 49). Several studies correlate trans fat consumption with cardiovascular events, and trans fats have also been implicated as an independent risk factor for endothelial dysfunction, systemic inflammation, and dyslipidemia, frequent comorbid conditions in patients with NAFLD (11, 27, 33, 35). No dietary studies concerning trans fat intake and NAFLD have been performed, and only a few studies involving a small number of patients exist examining dietary fat intake as it relates to NAFLD (32). These data indicate that mice fed a trans fat diet exhibit higher serum ALT values, increased insulin resistance, and increased IL-1β compared with mice fed a standard high-fat diet, despite similar amounts of hepatic steatosis. Additional work is needed to understand the molecular mechanisms by which trans fats may be more hepatotoxic.

GRANTS

Research supported by American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Research Scholar Award (S. W. P. Koppe) and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant RO1DK059580 (R. M. Green).

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1.Achyut BR, Srivastava A, Bhattacharya S, Mittal B. Genetic association of interleukin-1beta (-511C/T) and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (86 bp repeat) polymorphisms with Type 2 diabetes mellitus in North Indians. Clin Chim Acta 377: 163–169, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allison DB, Egan SK, Barraj LM, Caughman C, Infante M, Heimbach JT. Estimated intakes of trans fatty and other fatty acids in the US population. JAMA 99: 166–174; quiz 175–166, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alstrup KK, Gregersen S, Jensen HM, Thomsen JL, Hermansen K. Differential effects of cis and trans fatty acids on insulin release from isolated mouse islets. Metabolism 48: 22–29, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arslan U, Turkoglu S, Balcioglu S, Tavil Y, Karakan T, Cengel A. Association between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and coronary artery disease. Coron Artery Dis 18: 433–436, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ascherio A, Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Spiegelman D, Stampfer M, Willett WC. Dietary fat and risk of coronary heart disease in men: cohort follow up study in the United States. BMJ 313: 84–90, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bray GA, Most M, Rood J, Redmann S, Smith SR. Hormonal responses to a fast-food meal compared with nutritionally comparable meals of different composition. Ann Nutr Metab 51: 163–171, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cases JA, Gabriely I, Ma XH, Yang XM, Michaeli T, Fleischer N, Rossetti L, Barzilai N. Physiological increase in plasma leptin markedly inhibits insulin secretion in vivo. Diabetes 50: 348–352, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christiansen E, Schnider S, Palmvig B, Tauber-Lassen E, Pedersen O. Intake of a diet high in trans monounsaturated fatty acids or saturated fatty acids. Effects on postprandial insulinemia and glycemia in obese patients with NIDDM. Diabetes Care 20: 881–887, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cintra DE, Pauli JR, Araujo EP, Moraes JC, de Souza CT, Milanski M, Morari J, Gambero A, Saad MJ, Velloso LA. Interleukin-10 is a protective factor against diet-induced insulin resistance in liver. J Hepatol 48: 628–637, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark JM The epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in adults. J Clin Gastroenterol 40: S5–S10, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Roos NM, Bots ML, Katan MB. Replacement of dietary saturated fatty acids by trans fatty acids lowers serum HDL cholesterol and impairs endothelial function in healthy men and women. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 21: 1233–1237, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dixon JB, Bhathal PS, O'Brien PE. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: predictors of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and liver fibrosis in the severely obese. Gastroenterology 121: 91–100, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamaguchi M, Kojima T, Takeda N, Nagata C, Takeda J, Sarui H, Kawahito Y, Yoshida N, Suetsugu A, Kato T, Okuda J, Ida K, Yoshikawa T. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is a novel predictor of cardiovascular disease. World J Gastroenterol 13: 1579–1584, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harnack L, Lee S, Schakel SF, Duval S, Luepker RV, Arnett DK. Trends in the trans fatty acid composition of the diet in a metropolitan area: the Minnesota Heart Survey. JAMA 103: 1160–1166, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haukeland JW, Konopski Z, Linnestad P, Azimy S, Marit Loberg E, Haaland T, Birkeland K, Bjoro K. Abnormal glucose tolerance is a predictor of steatohepatitis and fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 40: 1469–1477, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu FB, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Colditz G, Liu S, Solomon CG, Willett WC. Diet, lifestyle, and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. N Engl J Med 345: 790–797, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu FB, van Dam RM, Liu S. Diet and risk of Type II diabetes: the role of types of fat and carbohydrate. Diabetologia 44: 805–817, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ibrahim A, Natrajan S, Ghafoorunissa R. Dietary trans fatty acids alter adipocyte plasma membrane fatty acid composition and insulin sensitivity in rats. Metabolism 54: 240–246, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ioannou GN, Weiss NS, Boyko EJ, Mozaffarian D, Lee SP. Elevated serum alanine aminotransferase activity and calculated risk of coronary heart disease in the United States. Heptology 43: 1145–1151, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jager J, Gremeaux T, Cormont M, Le Marchand-Brustel Y, Tanti JF. Interleukin-1beta-induced insulin resistance in adipocytes through down-regulation of insulin receptor substrate-1 expression. Endocrinology 148: 241–251, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim JH, Kim JE, Liu HY, Cao W, Chen J. Regulation of interleukin-6-induced hepatic insulin resistance by mammalian target of rapamycin through the STAT3-SOCS3 pathway. J Biol Chem 283: 708–715, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klover PJ, Clementi AH, Mooney RA. Interleukin-6 depletion selectively improves hepatic insulin action in obesity. Endocrinology 146: 3417–3427, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lagathu C, Yvan-Charvet L, Bastard JP, Maachi M, Quignard-Boulange A, Capeau J, Caron M. Long-term treatment with interleukin-1beta induces insulin resistance in murine and human adipocytes. Diabetologia 49: 2162–2173, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larsen CM, Faulenbach M, Vaag A, Volund A, Ehses JA, Seifert B, Mandrup-Poulsen T, Donath MY. Interleukin-1-receptor antagonist in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 356: 1517–1526, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lefevre M, Lovejoy JC, Smith SR, Delany JP, Champagne C, Most MM, Denkins Y, de Jonge L, Rood J, Bray GA. Comparison of the acute response to meals enriched with cis- or trans-fatty acids on glucose and lipids in overweight individuals with differing FABP2 genotypes. Metabolism 54: 1652–1658, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ling PR, Bistrian BR, Mendez B, Istfan NW. Effects of systemic infusions of endotoxin, tumor necrosis factor, and interleukin-1 on glucose metabolism in the rat: relationship to endogenous glucose production and peripheral tissue glucose uptake. Metabolism 43: 279–284, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lopez-Garcia E, Schulze MB, Meigs JB, Manson JE, Rifai N, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Hu FB. Consumption of trans fatty acids is related to plasma biomarkers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. J Nutr 135: 562–566, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Louheranta AM, Turpeinen AK, Vidgren HM, Schwab US, Uusitupa MI. A high-trans fatty acid diet and insulin sensitivity in young healthy women. Metabolism 48: 870–875, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lovejoy JC, Smith SR, Champagne CM, Most MM, Lefevre M, DeLany JP, Denkins YM, Rood JC, Veldhuis J, Bray GA. Effects of diets enriched in saturated (palmitic), monounsaturated (oleic), or trans (elaidic) fatty acids on insulin sensitivity and substrate oxidation in healthy adults. Diabetes Care 25: 1283–1288, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maedler K, Sergeev P, Ris F, Oberholzer J, Joller-Jemelka HI, Spinas GA, Kaiser N, Halban PA, Donath MY. Glucose-induced beta cell production of IL-1beta contributes to glucotoxicity in human pancreatic islets. J Clin Invest 110: 851–860, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marchesini G, Bugianesi E, Forlani G, Cerrelli F, Lenzi M, Manini R, Natale S, Vanni E, Villanova N, Melchionda N, Rizzetto M. Nonalcoholic fatty liver, steatohepatitis, and the metabolic syndrome. Heptology 37: 917–923, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mensink RP, Plat J, Schrauwen P. Diet and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Curr Opin Lipidol 19: 25–29, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mensink RP, Zock PL, Kester AD, Katan MB. Effects of dietary fatty acids and carbohydrates on the ratio of serum total to HDL cholesterol and on serum lipids and apolipoproteins: a meta-analysis of 60 controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr 77: 1146–1155, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meyer KA, Kushi LH, Jacobs DR Jr, Folsom AR. Dietary fat and incidence of type 2 diabetes in older Iowa women. Diabetes Care 24: 1528–1535, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mozaffarian D, Katan MB, Ascherio A, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC. Trans fatty acids and cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med 354: 1601–1613, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oh K, Hu FB, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC. Dietary fat intake and risk of coronary heart disease in women: 20 years of follow-up of the nurses' health study. Am J Epidemiol 161: 672–679, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oomen CM, Ocke MC, Feskens EJ, van Erp-Baart MA, Kok FJ, Kromhout D. Association between trans fatty acid intake and 10-year risk of coronary heart disease in the Zutphen Elderly Study: a prospective population-based study. Lancet 357: 746–751, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pisani LP, Oyama LM, Bueno AA, Biz C, Albuquerque KT, Ribeiro EB, Oller do Nascimento CM. Hydrogenated fat intake during pregnancy and lactation modifies serum lipid profile and adipokine mRNA in 21-day-old rats. Nutrition 24: 255–261, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rector RS, Thyfault JP, Wei Y, Ibdah JA. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and the metabolic syndrome: an update. World J Gastroenterol 14: 185–192, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rinella ME, Elias MS, Smolak RR, Fu T, Borensztajn J, Green RM. Mechanisms of hepatic steatosis in mice fed a lipogenic methionine choline-deficient diet. J Lipid Res 49: 1068–1076, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roach C, Feller SE, Ward JA, Shaikh SR, Zerouga M, Stillwell W. Comparison of cis and trans fatty acid containing phosphatidylcholines on membrane properties. Biochemistry 43: 6344–6351, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saladin R, De Vos P, Guerre-Millo M, Leturque A, Girard J, Staels B, Auwerx J. Transient increase in obese gene expression after food intake or insulin administration. Nature 377: 527–529, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salmeron J, Hu FB, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Rimm EB, Willett WC. Dietary fat intake and risk of type 2 diabetes in women. Am J Clin Nutr 73: 1019–1026, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sauter NS, Schulthess FT, Galasso R, Castellani LW, Maedler K. The anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-1Ra protects from high fat diet-induced hyperglycemia. Endocrinology 149: 2208–2218, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Senn JJ, Klover PJ, Nowak IA, Mooney RA. Interleukin-6 induces cellular insulin resistance in hepatocytes. Diabetes 51: 3391–3399, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shen J, Arnett DK, Peacock JM, Parnell LD, Kraja A, Hixson JE, Tsai MY, Lai CQ, Kabagambe EK, Straka RJ, Ordovas JM. Interleukin1beta genetic polymorphisms interact with polyunsaturated fatty acids to modulate risk of the metabolic syndrome. J Nutr 137: 1846–1851, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Svegliati-Baroni G, Bugianesi E, Bouserhal T, Marini F, Ridolfi F, Tarsetti F, Ancarani F, Petrelli E, Peruzzi E, Lo Cascio M, Rizzetto M, Marchesini G, Benedetti A. Post-load insulin resistance is an independent predictor of hepatic fibrosis in virus C chronic hepatitis and in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gut 56: 1296–1301, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Targher G, Bertolini L, Padovani R, Rodella S, Tessari R, Zenari L, Day C, Arcaro G. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and its association with cardiovascular disease among type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 30: 1212–1218, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Targher G, Bertolini L, Poli F, Rodella S, Scala L, Tessari R, Zenari L, Falezza G. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and risk of future cardiovascular events among type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes 54: 3541–3546, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ueki K, Kondo T, Tseng YH, Kahn CR. Central role of suppressors of cytokine signaling proteins in hepatic steatosis, insulin resistance, and the metabolic syndrome in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 10422–10427, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Van Dam RM, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, Hu FB. Dietary patterns and risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus in U. S. men. Ann Intern Med 136: 201–209, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van Dam RM, Willett WC, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Hu FB. Dietary fat and meat intake in relation to risk of type 2 diabetes in men. Diabetes Care 25: 417–424, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.