Abstract

After the ingestion of nutrients, secretion of the incretin hormones glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) by the enteroendocrine cells increases rapidly. Previous studies have shown that oral ingestion of fat stimulates secretion of both incretins; however, it is unclear whether there is a dose-dependent relationship between the amount of lipid ingested and the secretion of the hormones in vivo. Recently, we found a higher concentration of the incretin hormones in intestinal lymph than in peripheral or portal plasma. We therefore used the lymph fistula rat model to test for a dose-dependent relationship between the secretion of GIP and GLP-1 and dietary lipid. Under isoflurane anesthesia, the major mesenteric lymphatic duct of male Sprague-Dawley rats was cannulated. Each animal received a single, intraduodenal bolus of saline or varying amounts of the fat emulsion Liposyn II (0.275, 0.55, 1.1, 2.2, and 4.4 kcal). Lymph was continuously collected for 3 h and analyzed for triglyceride, GIP, and GLP-1 content. In response to increasing lipid calories, secretion of triglyceride, GIP, and GLP-1 into lymph increased dose dependently. Interestingly, the response to changes in intraluminal lipid content was greater in GLP-1- than in GIP-secreting cells. The different sensitivities of the two cell types to changes in intestinal lipid support the concept that separate mechanisms may underlie lipid-induced GIP and GLP-1 secretion. Furthermore, we speculate that the increased sensitivity of GLP-1 to intestinal lipid content reflects the hormone's role in the ileal brake reflex. As lipid reaches the distal portion of the gut, GLP-1 is secreted in a dose-dependent manner to reduce intestinal motility and enhance proximal fat absorption.

Keywords: lymph, lipid-induced incretin secretion, glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide, glucagon-like peptide-1, enteroendocrine cells

several investigators in the 1960s observed a 30–40% lower plasma insulin response to an intravenous rather than an oral glucose load. Accordingly, an alimentary mechanism, in addition to circulating blood glucose levels, was suggested to regulate insulin release from pancreatic β-cells (26). The postprandial enhancement of insulin secretion by gut factors was termed the incretin effect. Over the next 40 years, glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) were determined to be the hormones involved in the incretin effect. GIP is released from enteroendocrine K cells, which are located primarily in the duodenum and proximal jejunum, and is secreted in response to the absorption of nutrients. GLP-1 is secreted by intestinal L cells, which are located mainly in the distal ileum and colon, in response to a variety of nutrient, neural, and endocrine factors (33). Additionally, it has been reported that a small subset of duodenal endocrine cells contain both GIP and GLP-1 (23, 31).

As an incretin hormone, one of the primary functions of GIP is enhancement of postprandial insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells. GIP also upregulates β-cell insulin gene transcription and biosynthesis (35), stimulates β-cell proliferation, and reduces β-cell apoptosis. Of additional importance are the anabolic effects of GIP on adipocytes. Signaling through the GIP receptor increases fatty acid synthesis and incorporation into triglycerides (TGs) and downregulates lipolysis (1). GLP-1 exhibits similar insulinotropic effects by enhancing insulin secretion, stimulating β-cell proliferation, and decreasing β-cell apoptosis. GLP-1 additionally improves glycemic control by decreasing gastrointestinal motility via the ileal brake reflex, thereby reducing the delivery of absorbed nutrients to the circulation over time (17, 20, 29, 30). Interestingly, Nauck and colleagues (24) demonstrated that the insulinotropic effects of GLP-1 are outweighed by the hormone's ability to inhibit gastric emptying. Finally, it has been documented that exogenous administration of GLP-1 induces satiation (16, 32) and satiety (11, 25).

The primary stimulus for incretin secretion is the ingestion of nutrients. Carbohydrate, fat, and protein alone, as well as mixed meals, have been documented to induce the release of GIP and GLP-1 from enteroendocrine cells. However, the mechanisms underlying nutrient-induced incretin secretion are not clear. Studies suggest that nutrient absorption is required for GIP secretion, whereas the presence of nutrients in the lumen is sufficient to induce GLP-1 secretion. For example, GIP, but not GLP-1, secretion was affected in patients with intestinal malabsorption (2) and in studies using pharmacological agents that impede nutrient uptake (9, 10). Additionally, several G protein-coupled receptors involved in sugar sensing and fatty acid signaling have been detected on GLP-1-secreting cells (6, 12, 14, 21).

Although it is known that the ingestion of nutrients stimulates GIP and GLP-1 release, it is unclear whether there is a dose-dependent relationship between the amount of nutrient ingested and the secretion of the incretin hormones in vivo. Furthermore, it is not well defined whether the dose-response patterns are affected by the type of ingested macronutrient. In the present study, we used the lymph fistula rat model to specifically investigate how GIP and GLP-1 output is affected by increasing doses of intraduodenally infused lipid.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 250–350 g were purchased from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN). During a 2-wk acclimation period, the animals were allowed free access to water and standard chow (LM-485 Mouse/Rat Sterilizable Diet, Harlan Laboratories). The animals were housed in a room with a 12:12-h light-dark cycle (lights on at 6 AM and off at 6 PM); humidity was maintained at 50% and temperature at 21°C. The University of Cincinnati Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all procedures.

Surgical procedure and recovery.

Before surgery, the animals were fasted overnight with free access to water. Under isoflurane anesthesia, the superior mesenteric lymphatic duct was cannulated with polyvinyl chloride tubing (0.5 mm ID, 0.8 mm OD; Tyco Electronics, Castle Hill, Australia), with slight modifications to the procedure described by Bollman and colleagues (4). Instead of suture, the cannula was secured with a drop of cyanoacrylate glue (Krazy Glue, Columbus, OH). A silicone feeding tube (1.02 mm ID, 2.16 mm OD; VWR International, West Chester, PA) was introduced into the fundus of the stomach and advanced ∼2 cm beyond the pylorus into the duodenum. The feeding tube was secured by a purse-string ligature in the stomach. The lymph cannula and the duodenal feeding tube were exteriorized through the right flank. After surgery, the animals were placed in Bollman restraint cages (3) and allowed to recover overnight (18–22 h); the animals were kept in a temperature-regulated chamber (24°C) to prevent hypothermia. To compensate for fluid and electrolyte loss due to lymphatic drainage, we infused a 5% glucose-saline solution into the duodenum at 3 ml/h for 6–7 h and then saline only overnight at 3 ml/h.

Lipid infusion.

To test the effects of dietary fat on GIP and GLP-1 secretion, we provided a 3-ml bolus of a mixture of lipid emulsion (Liposyn II 20%, Hospira, Lake Forest, IL) and 0.9% saline as a single meal via the duodenal feeding tube. Five experimental doses (0.275, 0.55, 1.1, 2.2, and 4.4 kcal) were studied (Table 1). The caloric amount of the full dose (4.4 kcal) is equivalent to half of the total daily fat intake of the rat. Liposyn II 20% contains a 50:50 blend of safflower and soybean oil and has a caloric content of 2 kcal/ml. A 3-ml bolus of 0.9% saline was provided to a group of control animals.

Table 1.

Lipid infusion doses

| Dose | Lipid, ml | Saline, ml | kcal | TG, mg | No. of Animals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saline | 0 | 3.0 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| Lipid | |||||

| 1/16 | 0.1375 | 2.8625 | 0.275 | 30.5 | 9 |

| 1/8 | 0.275 | 2.725 | 0.55 | 61.0 | 8 |

| 1/4 | 0.55 | 2.45 | 1.1 | 122.0 | 8 |

| 1/2 | 1.1 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 244.0 | 8 |

| 1 | 2.2 | 0.8 | 4.4 | 488.0 | 9 |

TG, triglyceride.

Lymph collection.

Lymph was collected in a conical centrifuge tube on ice for 1 h to establish fasting lymph output and TG, GIP, and GLP-1 secretion. The animals (n = 50, 8–9 animals per group; Table 1) were then given the 3-ml lipid-saline bolus. At 30 min after the nutrient bolus, 0.9% saline was infused at 3 ml/h for the remainder of the study period. Lymph samples were collected on ice at 0.5, 1, 2, and 3 h after the lipid bolus. Each sample contained 10% by volume of an antiproteolytic cocktail (0.25 M EDTA, 0.80 mg/ml aprotinin, and 80 U/ml heparin).

TG measurement.

TG concentrations were determined using an assay kit that measures the amount of glycerol released from the hydrolysis of TGs (Randox, Crumlin, UK). After a 1:10 dilution with sterile water, 2 μl of diluted lymph sample were combined with 200 μl of reagent and incubated for 10 min at 21°C. The optical absorbance was read at 500 nm. Final concentrations were calculated using standards provided by Randox.

GIP and GLP-1 measurements.

GIP and GLP-1 concentrations were determined using commercially available ELISA kits (LINCO Research, St. Charles, MO). The GIP ELISA measures active GIP-(1–42) and nonactive GIP-(3–42). Lymph sample (10 μl) was added to each well of a microtiter plate precoated with anti-GIP monoclonal antibodies. After 1.5 h of incubation, 100 μl of detection antibody (biotinylated anti-GIP polyclonal antibody) were added to the captured molecules, the sample was incubated for 1 h, and 100 μl of enzyme solution (streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase conjugate) were added. For quantification of the immobilized antibody-enzyme conjugates, the horseradish peroxidase activity was monitored at 450 and 590 nm in the presence of 100 μl of substrate solution (3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine) and 100 μl of stop solution (0.3 M HCl). The final concentrations (pg/ml) were calculated using standards from LINCO Research.

The GLP-1 ELISA measures biologically active GLP-1-(7–37) and GLP-1-(7–36)NH2 and does not cross-react with glucagon, GLP-2, and inactive GLP-1-(9–37) and GLP-1-(9–36)NH2. Lymph sample (100 μl) was added to a microtiter plate precoated with anti-GLP-1 monoclonal antibodies and incubated overnight at 4°C. To each well, 200 μl of detection conjugate (anti-GLP-1 alkaline phosphatase conjugate) were added, and the sample was incubated for 2 h. For quantification of the antibody-enzyme conjugates, the fluorescent product formation was monitored after addition of 200 μl of diluted substrate (4-methylumbelliferyl phosphate). The phosphatase activity was measured at excitation and emission wavelengths of 355 and 460 nm, respectively, in the presence of 50 μl of stop solution. The final concentrations (pM) were calculated using standards provided by LINCO Research.

Data and statistical analysis.

We calculated hourly outputs by multiplying the hourly lymph volume by TG, GIP, or GLP-1 concentration. Hourly lymph, TG, GIP, and GLP-1 outputs were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA. Bonferroni's t-test was used as the posttest analysis. Differences were considered significant if P < 0.05. Total 3-h secretion for each parameter was determined by summing the hourly outputs for TG, GIP, or GLP-1 above the fasting level. Total lymph output was examined using a one-way ANOVA, whereas total TG, GIP, and GLP-1 outputs were analyzed using a Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA on ranks with Dunn's method as the posttest analysis. Differences were considered significant if P < 0.05. Additionally, cumulative GIP and GLP-1 outputs were plotted as a function of infused lipid dose after normalization of the data to saline levels. For each data set, best-fit lines were generated and subjected to linear regression analysis. Slopes were considered significantly different from zero if P < 0.05 (SigmaPlot, version 10.0).

RESULTS

Effect of lipid dose on lymph flow.

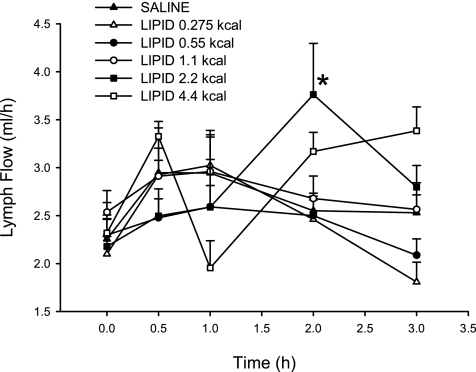

The lymph flow rate for the five experimental lipid doses and the saline control is shown in Fig. 1. The fasting lymph flow ranged from 2.10 ± 0.18 to 2.53 ± 0.23 ml/h and was similar for the five experimental groups, as well as the saline control. All the infusions, including the saline control, increased lymph flow slightly above fasting levels. Only the lymph flow for the 2.2-kcal lipid dose at 2 h was statistically different from saline (3.76 ± 0.53 and 2.55 ± 0.18 ml/h, respectively). However, there was no statistically significant difference in the total 3-h lymph output for any of the lipid groups (data not shown). The total lymph output ranged from 6.81 ± 0.50 to 9.20 ± 0.56 ml over the 3-h collection period.

Fig. 1.

Hourly lymph flow rate after administration of a duodenal bolus of lipid emulsion (0.275, 0.55, 1.1, 2.2, and 4.4 kcal) or saline. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. saline.

Effect of lipid dose on TG secretion.

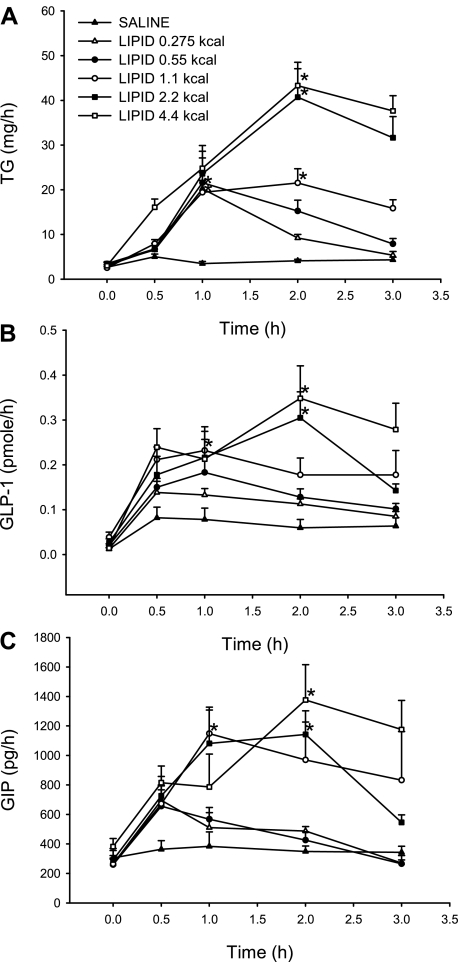

Lymph TG output was examined in response to increasing caloric doses of lipid infused into the duodenum. All five doses raised the level of lymphatic TG above that of the saline control at the 1- and 2-h time points (Fig. 2A). TG secretion peaked at 1 h for lipid doses of 0.275 and 0.55 kcal (20.23 ± 1.91 and 21.61 ± 5.54 mg/h, respectively) but peaked later, at 2 h, for lipid doses of 1.1, 2.2, and 4.4 kcal (21.55 ± 3.18, 40.73 ± 7.80, and 43.32 ± 3.77 mg/h, respectively). TG output was significantly different from saline for all five doses at the time of peak secretion. By 3 h, TG secretion was decreasing toward baseline or had returned to baseline for all doses.

Fig. 2.

Lymphatic triglyceride (TG, A), glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1, B), and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP, C) output after a duodenal bolus of lipid emulsion (0.275, 0.55, 1.1, 2.2, and 4.4 kcal) or saline plotted as a function of time. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. saline at time of peak secretion.

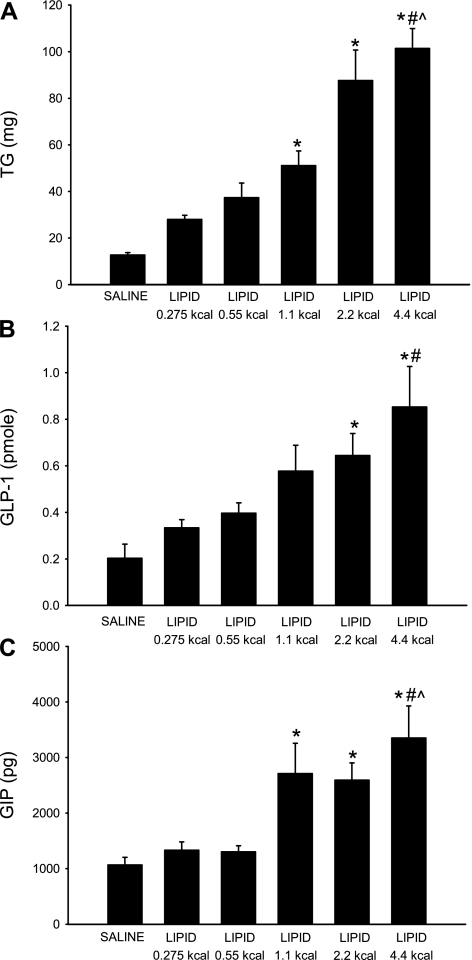

Cumulative TG secretion was calculated by summing the hourly TG outputs over the 3-h lymph collection period (Fig. 3A). As expected, the total TG secretion increased in response to larger amounts of dietary lipid: from 28.00 ± 1.77 mg for the 0.275-kcal lipid dose to 101.45 ± 8.46 mg for the 4.4-kcal lipid dose. Multiple comparison analysis detected five significant differences among the saline and lipid dose groups: 4.4 kcal vs. saline, 4.4 kcal vs. 0.275 kcal, 4.4 kcal vs. 0.55 kcal, 2.2 kcal vs. saline, and 1.1 kcal vs. saline. As the caloric content of each lipid dose increased, the cumulative TG secretion also increased, signifying a dose-dependent relationship.

Fig. 3.

Cumulative lymphatic TG (A), GLP-1 (B), and GIP (C) output after a duodenal bolus of lipid emulsion (0.275, 0.55, 1.1, 2.2, and 4.4 kcal) or saline. Cumulative secretion was calculated by summing hourly TG, GLP-1, or GIP output values over the 3-h collection period. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. saline. #P < 0.05 vs. 0.275-kcal lipid dose. ^P < 0.05 vs. 0.55-kcal lipid dose.

Effect of lipid dose on GLP-1 secretion.

Hourly lymphatic GLP-1 output was computed by multiplying lymph flow rate by hourly GLP-1 concentration (Fig. 2B). All lipid doses stimulated GLP-1 release above baseline. For the 0.275-kcal lipid dose, GLP-1 secretion peaked at 0.5 h (0.14 ± 0.03 pmol/h). Lipid doses of 0.55 and 1.1 kcal produced peak GLP-1 release at 1 h (0.18 ± 0.05 and 0.23 ± 0.03 pmol/h, respectively). GLP-1 output peaked at 2 h for the largest two lipid doses: 2.2 and 4.4 kcal (0.30 ± 0.06 and 0.35 ± 0.07 pmol/h, respectively). GLP-1 secretion was significantly different from saline at 2 h (peak output) for lipid doses of 2.2 and 4.4 kcal and was returning or had decreased to baseline for all lipid doses by 3 h.

Summing the hourly GLP-1 outputs over the collection period yielded the total 3-h GLP-1 output (Fig. 3B). Total GLP-1 secretion increased contemporaneously as the caloric amount of lipid increased: from 0.33 ± 0.04 pmol for the 0.275-kcal lipid dose to 0.85 ± 0.17 pmol for the 4.4-kcal lipid dose. GLP-1 secretion was ∼1.5- and 4-fold higher for the lowest and the highest lipid dose, respectively, than for the saline dose (0.20 ± 0.06 pmol). Multiple comparisons were made to determine whether there were statistical differences in the cumulative GLP-1 secretion among the five doses and the saline control. The total GLP-1 secretion for the 4.4-kcal lipid dose was significantly different from that for the 0.275-kcal lipid dose and the saline control; additionally, the total GLP-1 secretion for the 2.2-kcal lipid dose (0.64 ± 0.09 pmol) was significantly different from that for the saline control. Although significant differences were not detected for each dose comparison, cumulative GLP-1 output increased as the caloric content of lipid increased, suggestive of a dose-dependent trend.

Effect of lipid dose on GIP secretion.

To test the effects of varying lipid doses on GIP secretion, we calculated the product of the hourly GIP concentration and lymph flow rate (Fig. 2C). All five lipid doses stimulated GIP secretion above baseline. By 0.5 h, GIP secretion had peaked and was decreasing to baseline levels for 0.275- and 0.55-kcal lipid doses (695.29 ± 98.77 and 655.64 ± 111.83 pg/h, respectively). On the other hand, GIP secretion for the remaining three lipid doses peaked at later time points before returning to baseline. At 1 h, the 1.1-kcal lipid dose generated a peak in GIP secretion that was significantly greater than that generated by saline (1,147.56 ± 160.65 pg/h). Lipid doses of 2.2 and 4.4 kcal yielded peaks at 2 h (1,142.93 ± 160.36 and 1,375.95 ± 240.02 pg/h, respectively). At 2 h, GIP output generated by saline was significantly different from that generated by 2.2- and 4.4-kcal lipid doses.

Total 3-h GIP secretion was calculated from the sum of the hourly GIP output values (Fig. 3C). GIP secretion ranged from 1,331.58 ± 148.23 pg for the 0.275-kcal lipid dose to 3,352.24 ± 575.07 pg for the 4.4-kcal lipid dose. Multiple comparisons allowed further analysis of the differences among the lipid doses. Five significant differences were detected: 4.4 kcal vs. saline, 4.4 kcal vs. 0.275 kcal, 4.4 kcal vs. 0.55 kcal, 2.2 kcal vs. saline, and 1.1 kcal vs. saline. Similar to GLP-1 secretion, total GIP secretion appeared to follow a dose-dependent trend in response to increasing amounts of lipid.

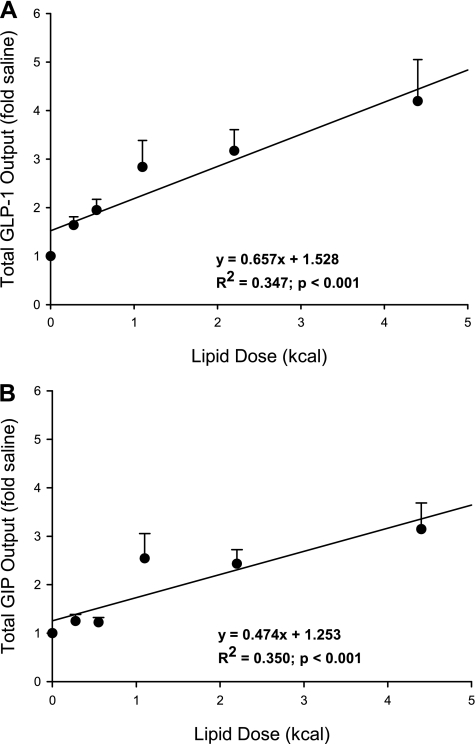

GLP-1 vs. GIP secretion.

To compare the secretory ability of GLP-1-producing cells with that of GIP-producing cells, we plotted the cumulative output data as a function of infused lipid calories after normalization to saline levels (Fig. 4). The equations for the best-fit lines generated for GLP-1 and GIP are as follows: y = 0.657x + 1.528 (R2 = 0.347, P < 0.001) and y = 0.474x + 1.253 (R2 = 0.350, P < 0.001), respectively. Although both lines have slopes significantly greater than zero, indicative of a dose-dependent relationship, the steeper slope for the GLP-1 data suggests that the GLP-1-secreting cells are more sensitive to changes in intraluminal lipid content.

Fig. 4.

Cumulative lymphatic GLP-1 (A) and GIP (B) output plotted as a function of infused lipid dose (0.275, 0.555, 1.1, 2.2, and 4.4 kcal) were tested. Values (fold amounts above saline) are means ± SE. Equations for best-fit lines generated for GLP-1 and GIP are shown. Both slopes are significantly greater than zero (P < 0.001) and differed between the two lines.

DISCUSSION

The incretin hormones GIP and GLP-1 are secreted from the enteroendocrine K and L cells, respectively, and enhance postprandial insulin secretion. The primary stimulus for the secretion of the incretin hormones is the ingestion of nutrients. Carbohydrate, fat, and protein alone, as well as mixed meals, have been reported to induce the release of GIP and GLP-1 (8, 15). Whether there are dose-response relationships between the amount and type of macronutrient ingested and the secretion of incretins in vivo, however, has not been well defined.

The incretin hormones are typically measured in the systemic blood; however, the concentration of GIP and GLP-1 in plasma is low because of portal dilution and rapid degradation by dipeptidyl-peptidase IV. Additionally, incretin measurements in plasma are difficult because of the limited volume of blood that can be removed from an animal. Recently, we found that intestinal lymph is an alternative fluid compartment in which to measure the incretin hormones (7, 18, 19). In the lymph fistula rat, a catheter is inserted into the superior mesenteric lymphatic duct, which allows for drainage from the entire gastrointestinal tract (4). The concentration of GIP and GLP-1 is higher in intestinal lymph than in portal or peripheral plasma. The high concentration is due, in part, to less dipeptidyl-peptidase IV degradation. Also, since lymph has a lower flow rate than portal blood, the hormones are less diluted once secreted from the enteroendocrine cells, thereby raising the concentration of GIP and GLP-1. The lymph fistula rat model is an excellent tool to study incretin hormone release because the measured concentrations more closely mimic the amount of hormone sensed by the enteric neurons. In addition, the elevated concentrations allow for sensitive detection of incretin secretion changes in response to external stimuli, such as nutrients.

Using the lymph fistula rat model, we investigated the effects of increasing doses of lipid on postprandial GIP and GLP-1 secretion over a 3-h time period. Here, we have shown that both GIP and GLP-1 cumulative 3-h outputs, as well as peak hourly outputs, respond dose dependently to increasing doses of dietary lipid ranging from 0.275 to 4.4 kcal. Consistent with our present findings, it has been suggested that GLP-1 secretion is dependent on the caloric size of the ingested meal (1). In vitro, α-linolenic (12), oleic (13), and palmitoleic (27) acids have been found to have a dose-dependent stimulatory effect on GLP-1 secretion. Additionally, Vilsbøll and colleagues (34) reported that GIP and GLP-1 secretion was higher in lean and obese humans, as well as in type 1 and type 2 diabetic patients, after a large mixed meal than after an identical meal of lower caloric value. Furthermore, GLP-2, a proglucagon-derived peptide cosecreted with GLP-1, appears to be secreted in a calorically dependent manner (36).

Although both hormones responded dose dependently to increasing caloric amounts of lipid, the secretion pattern was not as well defined for GIP as for GLP-1. As shown in Fig. 3C, total GIP secretion seemed to exhibit a trend toward a fairly constant response within a certain dose range. The lower two lipid doses (0.275 and 0.55 kcal) induced the same amount of cumulative GIP release, whereas the larger three lipid doses (1.1, 2.2, and 4.4 kcal) stimulated a similar level of GIP secretion that was ∼2.3-fold higher than that produced by the lower two doses. It is tempting to suggest an all-or-nothing phenomenon, in which only those lipid doses containing ≥1.1 kcal are capable of stimulating a substantial and prolonged GIP response; however, the statistical analysis is not clear enough to make this conclusion. We are unaware of data that suggest that the secretion of GIP in response to nutrient intake follows an all-or-nothing pattern.

Additionally, our data demonstrated that the GLP-1-secreting L cells may be more sensitive than the GIP-secreting K cells to changes in intraluminal lipid content. Plotting the cumulative 3-h outputs against the amount of infused lipid generated best-fit lines with slopes of 0.657 for GLP-1 and 0.474 for GIP. The larger slope for the GLP-1 data suggests that the GLP-1-secreting cells are more responsive to changes in the amount of dietary lipid. Indeed, in previously published reports from our laboratory (18, 19), we found that the peak stimulation was 10-fold greater than fasting levels for GLP-1 vs. 4-fold greater than fasting levels for GIP in response to a 4.4-kcal lipid bolus, further signifying that the GLP-1-secreting cells respond more robustly to intestinal lipid loads. Although supported in the literature, this result is somewhat surprising. Since fat absorption occurs predominantly within the jejunum, it would be expected that less lipid would reach the distal portion of the small intestine, where the majority of L cells are located. Less available lipid would therefore mean less nutrient stimulation and lower levels of GLP-1 release. However, this explanation is based on the assumption that the regulation of GIP and GLP-1 secretion is the same. It is commonly accepted that GIP secretion is dependent on nutrient absorption, whereas the presence of the nutrients in the intestinal lumen is sufficient to stimulate GLP-1 secretion, indicating that the underlying mechanisms behind GIP and GLP-1 secretion may differ. For instance, in observations from patients with intestinal malabsorption (2) and studies using pharmacological agents that impede nutrient uptake (9, 10), GIP secretion was diminished, whereas GLP-1 secretion was unaffected. Because of the differences in nutrient sensing, it is reasonable to suggest that the K cells and L cells may have different levels of responsiveness to a given amount of lipid.

The enhanced sensitivity of GLP-1 secretion to increasing lipid loads reflects the hormone's role in the ileal brake reflex (17, 20, 24, 29, 30). The ileal brake is a distal-to-proximal feedback loop that slows the gastrointestinal transit of nutrients to aid digestion and absorption. The presence of nutrients in the ileum induces a signal to the proximal gut to delay gastric emptying and reduce intestinal motility. Although the identity of the ileal brake mediators is not entirely clear, GLP-1 is considered a strong candidate. In the present experiment, to eliminate the effects of variable rates of nutrient entry due to gastric emptying, we infused the lipid doses intraduodenally. The duodenal infusion increases the likelihood that fat would reach the distal portion of the gut and, subsequently, indicates to the body that nutrients have not yet been absorbed. Previous studies (5, 28) have detected radiolabeled lipid in the ileum within 15 min of an intragastric dose of triolein as small as 10 mg (0.9 kcal) and a 1-kcal intragastric dose of Intralipid. Although we cannot be certain that the lipid is reaching the ileum in a dose-dependent manner, we hypothesize that as the infused lipid dose increases, more fat reaches the ileum and, consequently, the secretion of GLP-1 increases. The elevated levels of GLP-1 would then, in turn, act on the proximal gut by slowing intestinal transit, thereby promoting increased fat digestion and absorption.

In summary, we have demonstrated that, in response to increasing lipid calories, the secretion of TG and the incretin hormones GIP and GLP-1 into the lymph increased dose dependently over a 3-h time period. Additionally, we have shown that the GLP-1-secreting cells are more responsive than GIP-secreting cells to changes in intraluminal lipid content. The different sensitivities of the K cells and L cells to changes in intestinal lipid support the concept that separate mechanisms may underlie lipid-induced GIP and GLP-1 secretion. Furthermore, we speculate that the increased sensitivity of GLP-1 to intestinal lipid content reflects the hormone's role in the ileal brake reflex. As lipid reaches the distal portion of the gut, GLP-1 is secreted in a dose-dependent manner to reduce intestinal motility and enhance proximal fat absorption. Whether this paradigm is dependent on the type of macronutrient and will be altered in diet-induced obese or type 2 diabetic animals is of considerable interest to basic and clinical scientists.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants DK-056863 (P. Tso), DK-059360 (P. Tso), and DK-082205 (T. L. Kindel).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Drs. Min Liu and Ron Jandacek for advice on the statistical analysis and for suggestions during the preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baggio LL, Drucker DJ. Biology of incretins: GLP-1 and GIP. Gastroenterology 132: 2131–2157, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Besterman HS, Cook GC, Sarson DL, Christofides ND, Bryant MG, Gregor M, Bloom SR. Gut hormones in tropical malabsorption. Br Med J 2: 1252–1255, 1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bollman JL A cage which limits the activity of rats. J Lab Clin Med 33: 1348, 1948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bollman JL, Cain JC, Grindlay JH. Techniques for the collection of lymph from the liver, small intestine, or thoracic duct of the rat. J Lab Clin Med 33: 1349–1352, 1948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Booth CC, Read AE, Jones E. Studies on the site of fat absorption: the sites of absorption of increasing doses of 131I-labelled triolein in the rat. Gut 2: 23–31, 1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chu Z, Carroll C, Alfonso J, Gutierrez V, He H, Lucman A, Pedraza M, Mondala H, Gao H, Bagnol D, Chen R, Jones RM, Behan DP, Leonard J. A role for intestinal endocrine cell-expressed G protein-coupled receptor 119 in glycemic control by enhancing glucagon-like peptide-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide release. Endocrinology 149: 2038–2047, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D'Alessio D, Lu W, Sun W, Zheng S, Yang Q, Seeley R, Woods SC, Tso P. Fasting and postprandial concentrations of glucagon-like peptide 1 in intestinal lymph and portal plasma: evidence for selective release of GLP-1 into the lymph system. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 293: R2163–R2169, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deacon CF What do we know about the secretion and degradation of incretin hormones? Regul Pept 128: 117–124, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fukase N, Takahashi H, Manaka H, Igarashi M, Yamatani K, Daimon M, Sugiyama K, Tominaga M, Sasaki H. Differences in glucagon-like peptide-1 and GIP responses following sucrose ingestion. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 15: 187–195, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fushiki T, Kojima A, Imoto T, Inoue K, Sugimoto E. An extract of Gymnema sylvestre leaves and purified gymnemic acid inhibits glucose-stimulated gastric inhibitory peptide secretion in rats. J Nutr 122: 2367–2373, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gutzwiller JP, Göke B, Drewe J, Hildebrand P, Ketterer S, Handschin D, Winterhalder R, Conen D, Beglinger C. Glucagon-like peptide-1: a potent regulator of food intake in humans. Gut 44: 81–86, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirasawa A, Tsumaya K, Awaji T, Katsuma S, Adachi T, Yamada M, Sugimoto Y, Miyazaki S, Tsujimoto G. Free fatty acids regulate gut incretin glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion through GPR120. Nat Med 11: 90–94, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iakoubov R, Izzo A, Yeung A, Whiteside CI, Brubaker PL. Protein kinase Cζ is required for oleic acid-induced secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1 by intestinal endocrine L cells. Endocrinology 148: 1089–1098, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jang H, Kokrashvili Z, Theodorakis MJ, Carlson OD, Kim B, Zhou J, Kim HH, Xu X, Chan SL, Juhaszova M, Bernier M, Mosinger B, Margolskee RF, Egan JM. Gut-expressed gustducin and taste receptors regulate secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 15069–15074, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karhunen LJ, Juvonen KR, Huotari A, Purhonen AK, Herzig KH. Effect of protein, fat, carbohydrate and fibre on gastrointestinal peptide release in humans. Regul Pept 149: 70–78, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larsen PJ, Fledelius C, Knudsen LB, Tang-Christensen M. Systemic administration of the long-acting GLP-1 derivative NN2211 induced lasting and reversible weight loss in both normal and obese rats. Diabetes 50: 2530–2539, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Layer P, Peschel S, Schlesinger T, Goebell H. Human pancreatic secretion and intestinal motility: effects of ileal nutrient perfusion. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 258: G196–G201, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu WJ, Yang Q, Sun W, Woods SC, D'Alessio D, Tso P. The regulation of the lymphatic secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) by intestinal absorption of fat and carbohydrate. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 293: G963–G971, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu WJ, Yang Q, Sun W, Woods SC, D'Alessio D, Tso P. Using the lymph fistula rat model to study the potentiation of GIP secretion by the ingestion of fat and glucose. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 294: G1130–G1138, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maljaars PWJ, Peters HPF, Mela DJ, Masclee AAM. Ileal brake: a sensible food target for appetite control. Physiol Behav 95: 271–281, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Margolskee RF, Dyer J, Kokrashvili Z, Salmon KSH, Ilegems E, Daly K, Maillet EL, Ninomiya Y, Mosinger B, Shirazi-Beechey SP. TIR3 and gustducin in gut sense sugars to regulate expression of Na+-glucose cotransporter 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 15075–15080, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mentlein R, Gallwitz B, Schmidt WE. Dipeptidyl-peptidase IV hydrolyses gastric inhibitory polypeptide, glucagon-like peptide-1 (7–36)amide, peptide histidine methionine, and is responsible for their degradation in human serum. Eur J Biochem 214: 829–835, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mortensten K, Christensen LL, Holst JJ, Orskov C. GLP-1 and GIP are colocalized in a subset of endocrine cells in the small intestine. Regul Pept 114: 189–196, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nauck MA, Niedereichholz U, Ettler R, Holst JJ, Ørskov C, Ritzel R, Schmiegel WH. Glucgaon-like peptide 1 inhibition of gastric emptying outweighs its insulinotropic effects in healthy humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 273: E981–E988, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Näslund E, Barkeling B, King N, Gutniak M, Blundell JE, Holst JJ, Rössner S, Hellström PM. Energy intake and appetite are suppressed by glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) in obese men. Int J Obes 23: 304–311, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perley MJ, Kipnis DM. Plasma insulin response to oral and intravenous glucose: studies in normal and diabetic subjects. J Clin Invest 46: 1954–1962, 1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rocca AS, Brubaker PL. Stereospecific effects of fatty acids on proglucagon-derived peptide secretion in fetal rat intestinal cultures. Endocrinology 136: 5593–5599, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodriguez MD, Kalogeris TJ, Wang XL, Wolf R, Tso P. Rapid synthesis and secretion of intestinal apolipoprotein A-IV after gastric fat loading in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 272: R1170–R1177, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spiller RC, Trotman IF, Adrian TE, Bloom SR, Misiewicz JJ, Silk DBA. Further characterization of the “ileal brake” reflex in man—effect of ileal infusion of partial digests of fat, protein, and starch on jejunal motility and release of neurotensin, enteroglucagon, and peptide YY. Gut 29: 1042–1051, 1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spiller RC, Trotman IF, Higgins BE, Ghatei MA, Grimble GK, Lee YC, Bloom SR, Misiewicz JJ, Silk DBA. The ileal brake—inhibition of jejunal motility after ileal fat perfusion in man. Gut 25: 365–374, 1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Theodorakis MJ, Carlson O, Michopoulos S, Doyle ME, Juhaszova M, Petraki K, Egan JM. Human duodenal enteroendocrine cells: source of both incretin peptides, GLP-1 and GIP. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 290: E550–E559, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turton MD, O'Shea D, Gunn I, Beak SA, Edwards CMB, Meeran K, Choi SJ, Taylor GM, Heath MM, Lambert PD, Wilding JPH, Smith DM, Ghatei MA, Herbert J, Bloom SR. A role for glucagon-like peptide-1 in the central regulation of feeding. Nature 379: 69–72, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vilsbøll T, Krarup T, Deacon CF, Madsbad S, Holst JJ. Reduced postprandial concentrations of intact biologically active glucagon-like peptide 1 in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes 50: 609–613, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vilsbøll T, Krarup J, Sonne S, Madsbad A, Vølund AG, Holst JJ. Incretin secretion in relation to meal size and body weight in healthy subjects and people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88: 2706–2713, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Y, Montrose-Rafizadeh C, Adams L, Raygada M, Nadiv O, Egan JM. GIP regulates glucose transporters, hexokinases, and glucose-induced insulin secretion in RIN 1046-38 cells. Endocrinology 116: 81–87, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiao Q, Boushey RP, Drucker DJ, Brubaker PL. Secretion of the intestinotropic hormone glucagon-like peptide 2 is differentially regulated by nutrients in humans. Gastroenterology 117: 99–105, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]