Abstract

The goal of this investigation was to determine the distribution of myocardial apoptosis in myocytes and nonmyocytes in primates and patients with heart failure (HF). Almost all clinical cardiologists and cardiovascular investigators believe that myocyte apoptosis is considered to be a cardinal sign of HF and a major factor in its pathogenesis. However, with the knowledge that 75% of the number of cells in the heart are nonmyocytes, it is important to determine whether the apoptosis in HF is occurring in myocytes or in nonmyocytes. We studied both a nonhuman primate model of chronic HF, induced by rapid pacing 2–6 mo after myocardial infarction (MI), and biopsies from patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. Dual labeling with a cardiac muscle marker was used to discriminate apoptosis in myocytes versus nonmyocytes. Left ventricular ejection fraction decreased following MI (from 78% to 60%) and further with HF (35%, P < 0.05). As expected, total apoptosis was increased in the myocardium following recovery from MI (0.62 cells/mm2) and increased further with the development of HF (1.91 cells/mm2). Surprisingly, the majority of apoptotic cells in MI and MI + HF, and in both the adjacent and remote areas, were nonmyocytes. This was also observed in myocardial biopsies from patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. We found that macrophages contributed the largest fraction of apoptotic nonmyocytes (41% vs. 18% neutrophils, 16% fibroblast, and 25% endothelial and other cells). Although HF in the failing human and monkey heart is characterized by significant apoptosis, in contrast to current concepts, the apoptosis in nonmyocytes was eight- to ninefold greater than in myocytes.

Keywords: myocytes, macrophages, cardiomyopathy, caspase-3

since the report of apoptosis in the ischemia-reperfused rabbit heart (17), it has been suggested that apoptosis may be responsible for a significant amount of cardiomyocyte death during the acute and chronic stages of myocardial infarction (MI) (5, 32, 38, 50). The importance of apoptosis in the pathogenesis of heart failure (HF) has also been emphasized in both animal models and humans (1, 11, 13, 16, 18, 29, 32, 42, 44, 50). Further evidence supporting an important role for apoptosis in left ventricular (LV) dysfunction and HF comes from studies of coronary artery occlusion (CAO) and reperfusion (6, 34, 36). Conversely, other studies, using transgenic or knockout mice, have found that the inhibition of apoptosis results in a reduced infarct size and in the maintenance of LV function (9, 20, 23, 27, 28). Therefore, it has been suggested that apoptosis plays an adverse role in LV remodeling and contributes to the development of HF after chronic MI (1, 5, 18, 35, 37, 38, 42). Although most studies of apoptosis have focused on the infarct area in the central ischemic zone (1, 5), others have observed apoptosis in adjacent and remote myocardium (1, 5, 33, 34, 41). It is tacitly assumed that apoptosis in myocytes may ultimately diminish the number of contractile elements in the heart, resulting in LV dysfunction and HF. In view of the fact that 75% of the cells in the heart are nonmyocytes (21), it is not unreasonable to expect that apoptosis may also occur in these cells, as well as in myocytes. We tested this hypothesis both in a nonhuman primate model of chronic HF, induced by rapid pacing initiated 2–6 mo following MI, and also in myocardial biopsies from patients with HF.

METHODS

Monkey model of HF following chronic MI.

Twenty 3.4–9.5-yr-old male monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) were assigned to one of three groups: chronic MI with and without HF or sham-operated controls. Monkeys were fed a standard primate diet containing 5 to 6% fat, 18 to 25% protein, and 0.2 to 0.3% sodium chloride as previously described (3). All monkeys had normal laboratory values for fasting plasma glucose, cholesterol, and triglycerides. This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and the Institutional Review Board at the New Jersey Medical School.

After 1 mo quarantine, animals were tranquilized with ketamine hydrochloride (2 to 3 mg/kg im) and then anesthetized with isoflurane (1.0 to 2.0 vol/100 ml in oxygen) and were instrumented for measurements of LV hemodynamics as we have reported previously (3, 4, 43). Tygon catheters were implanted in the descending aorta and left atrium for pressure measurements. A miniature solid-state pressure gauge (Konigsberg Instruments; Pasadena, CA) was inserted into the LV through the apex for measurements of LV pressure and the first derivative of LV pressure. After that, the mid-left anterior descending coronary artery and its branches were occluded to induce MI. For the MI group, myocardial tissue samples were obtained after 2 mo of MI. For the MI + HF group, rapid ventricular pacing, at a rate of 270 beats/min, was initiated after 2–6 mo of MI and continued until the development of HF, at which point tissue samples were obtained.

To measure LV function, transthoracic echocardiography was performed in monkeys using ultrasonography (Sequoia C256; Acuson, Malvern, PA) with a 13-MHz annular array transducer. Measurements of the LV end-diastolic diameter were taken at the time of the apparent maximal LV diastolic dimension, whereas measurements of the LV end-systolic diameter were taken at the time of the most anterior systolic excursion of the posterior wall. LV ejection fraction (LVEF) was calculated as LVEF = [(LV end-diastolic diameter)3 − (LV end-systolic diameter)3]/(LV end-diastolic diameter)3.

Cardiomyopathy and HF in patients.

All LV biopsies were collected in patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy at the time of clinically indicated cardiac catherization; informed consent was obtained from all patients. The biopsies were fixed in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin. DNA fragmentation was detected in situ by using terminal deoxynucleotide transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL). The apoptotic rate was expressed as the percentage of TUNEL-positive cells per nuclei.

Evaluation of apoptosis.

Tissue samples were collected from the adjacent and remote areas of the myocardium. Samples of the LV were fixed by immersion in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin. To have a representative quantification of apoptosis, serial 6-μm sections were cut. Sections 300 μm apart (3 sections per monkey) were analyzed.

Apoptosis was detected by TUNEL. The procedure was performed using an in situ cell death detection kit (Roche) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, deparaffinized sections were treated with proteinase K (20 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min and DNA fragments labeled with biotin-conjugated dUTP and terminal deoxyribonucleotide transferase for 1 hr at 37°C and visualized with Streptavidin Alexa fluorescent-dye conjugates (IgG, green, dilution, 1:500; Invitrogen). Sections were mounted using Vectashield mounting medium containing 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI).

Apoptosis was also evaluated by immunostaining for the cleaved form of caspase-3 (12, 52). For this, antigen retrieval was performed by immersing the sections in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0) and boiling under pressure for 30 min. Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched by an incubation of 3% H2O2 in methanol for 10 min, and 5% serum was used for blocking nonspecific binding. Monoclonal antibody against the cleaved form of caspase-3 (5A1E, dilution 1:400; Cell Signaling) was used for detecting apoptosis. After an overnight incubation with the primary antibody, the sections were incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to biotin (Vector), followed by peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin (Vectastatin Elite ABC peroxidase kit, Vector), amplification with TSA Biotin system (Tyramide Signal Amplification, PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences), and detection by Streptavidin Alexa fluorescent-dye conjugates (IgG, green; Invitrogen).

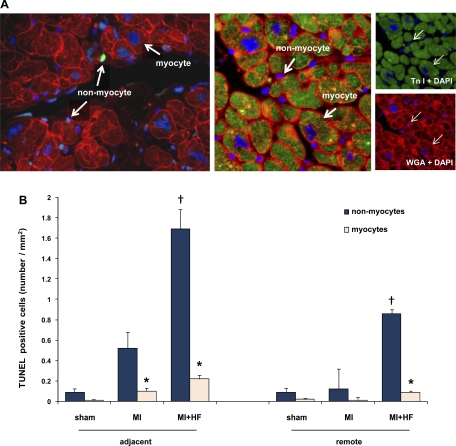

To discriminate apoptosis in nonmyocytes and myocytes, the tissue sections were dual stained for the cleaved form of caspase-3 and either counterstained with rhodamine-conjugated wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) (Vector) or with an antibody against cardiac troponin I (clone2D5; Lab Vision). WGA stains all cell membranes, allowing for a discrimination of myocytes and nonmyocytes based on cell size, myocytes being the largest cells present in myocardium. In addition, in LV myocytes, the pattern of WGA staining not only was seen at the outer membrane but also followed a striated pattern in longitudinal sections (Fig. 1A, left). To confirm the identity of myocytes stained by WGA, the sections were double stained with WGA and troponin I, which is a specific antibody for human cardiac troponin subunit I. Representative WGA/troponin I images are shown in Fig. 1A, right. The glycocalyx of the sarcolemma, both at the lateral surface and intercalated disk region, was clearly stained with WGA (red), and immunolabeled troponin I (green) was confined to myocytes. The merged image (Fig. 1A, middle) shows the complete match of WGA and troponin I staining of myocytes. The total field area (in mm2) of the slide was measured using the trace function in ImageProPlus (Media Cybernetics). Results are expressed as the number of positive cells per squared millimeters.

Fig. 1.

The increase of apoptosis after chronic myocardial infarction (MI) and after MI + heart failure (HF). A: representative examples of the staining used to discriminate apoptosis in myocytes from nonmyocytes (left). Myocytes were stained with cardiac troponin I (TnI) (green; A, right, top) and counterstained with rhodamine wheat germ agglutinin (WGA; red; A, right, bottom). Nuclei were stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; blue). A, middle: merged image. B: quantification of apoptosis in myocytes and nonmyocytes in adjacent and remote regions. In all conditions, the increase in apoptosis was greater in nonmyocytes than myocytes. Sham-operated (n = 6), MI (n = 5), MI + HF (n = 9) monkeys are represented. TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotide transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling. *P < 0.05, nonmyocytes vs. myocytes; †P < 0.05, compared with MI vs. MI + HF. These sections were obtained from myocardium sufficiently distant from the chronic infarct, so that myocyte structure remained intact and cardiac troponin I could be used as a marker for the myocytes.

Immunohistochemical staining for identification of nonmyocytes.

For the identification of nonmyocyte cell types, serial tissue sections were immunostained with the following antibodies: monoclonal antibody to macrophage (clone HAM56) (dilution 1:20; Novus Biologicals) for macrophages, neutrophil elastase (clone NP57) (dilution 1:50; DAKO) for neutrophils, heat shock protein 47 (dilution 1:50; Stressgen) for fibroblasts, and CD31 (platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1) (clone 1A10, dilution 1:100; Zymed) for endothelial cells. Primary antibodies were detected by Streptavidin Alexa fluorescent-dye conjugates (Invitrogen): Alexa 555 (IgM), Alexa 594 (IgG), and Alexa 488 (IgG). Apoptotic nonmyocytes were detected by dual staining with cleaved caspase-3 or by TUNEL assay.

Statistics.

All data are expressed as means ± SE. Comparisons between apoptotic nonmyocytes and myocytes were made using the Student's t-test. For statistical analysis of data from multiple groups, ANOVA was used. P < 0.05 was taken as a minimal level of significance.

RESULTS

Chronic MI + HF monkey model.

Following 2–6 mo of CAO-induced MI, LV function was already depressed, as reflected by a rise in LV end-diastolic pressure and a decrease in LVEF (Table 1). With a superimposition of pacing, severe HF developed, characterized by a further increase in LV end-diastolic pressure and a decrease in LVEF, which fell from 78 ± 8% in the sham-operated animals to 60 ± 4% following MI and further in HF (35 ± 5%, P < 0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Hemodynamics

| Sham | MI | MI + HF | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 6 | 5 | 9 |

| LVSP, mmHg | 121±10 | 129±5 | 90±5*† |

| LVEDP, mmHg | 5±1 | 15±3* | 18±1* |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 169±10 | 168±12 | 164±8 |

| LVEF, % | 78±8 | 60±4* | 35±5*† |

Values are means ± SE; n, number of monkeys. MI, myocardial infarction; HF, heart failure; LVSP, left ventricular (LV) systolic pressure; LVEDP, LV end-diastolic pressure; LVEF, LV ejection fraction.

P < 0.05 vs. sham;

P < 0.05 vs. MI.

Apoptosis in adjacent and remote myocardium.

Significant increases in total apoptosis occurred following chronic MI and increased further after HF developed. There was significantly more total apoptosis in the area adjacent to the infarct compared with the remote myocardium (P < 0.05, Fig. 1B). However, the rates of apoptosis in the adjacent myocardium, in both myocytes and nonmyocytes, in MI and MI + HF were greater than in controls. In the adjacent myocardium in MI + HF, we observed a significantly greater (8-fold) increase in TUNEL-positive cells in nonmyocytes (1.69 ± 0.19 cells/mm2) compared with myocytes (0.22 ± 0.04 cells/mm2) (P < 0.05) (n = 9). In the remote area, TUNEL-positive cells were also eight- to ninefold more (P < 0.05) in nonmyocytes (0.86 ± 0.20 cells/mm2) compared with myocytes (0.09 ± 0.03 cells/mm2) (n = 9). The nonmyocytes were characteristically smaller than myocytes (Fig. 1). The quantitation of the total apoptotic cells and the percentage of nonmyocyte apoptosis in sham-operated, MI, and MI + HF monkeys are shown in Fig. 1B and Table 2, respectively.

Table 2.

Apoptosis

| Sham | MI | MI + HF | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 6 | 5 | 9 |

| Adjacent area | |||

| Total apoptosis, cells/mm2 | 0.08±0.04 | 0.62±0.18* | 1.91±0.22*† |

| %Nonmyocyte apoptosis | 88±8 | 84±3 | 89±2 |

| Remote area | |||

| Total apoptosis, cells/mm2 | 0.04±0.04 | 0.14±0.05 | 0.95±0.21*† |

| %Nonmyocyte apoptosis | 75±1 | 86±10 | 91±3 |

Values are means ± SE; n, number of monkeys.

P < 0.05 MI vs. sham;

P < 0.05, HF vs. MI.

Immunostaining for the cleaved form of caspase-3 in adjacent and remote myocardium of MI + HF.

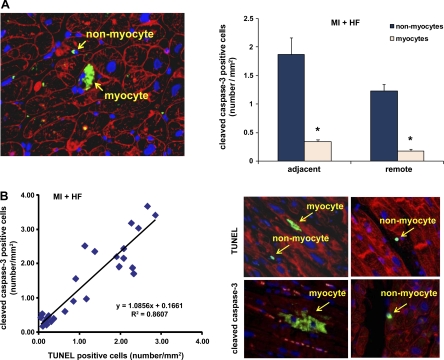

Apoptosis, assessed by cleaved caspase-3 staining, was similar to data described for TUNEL, i.e., the majority of apoptosis occurred in nonmyocytes (Fig. 2A, right). The results between TUNEL and cleaved caspase-3 immunostaining show a strong positive correlation (Fig. 2B, left). Representative TUNEL- and cleaved caspase-3-positive cells are shown in Fig. 2B, right. A representative immunohistochemical image of double staining with cleaved caspase-3 and WGA is shown in Fig. 2A, left.

Fig. 2.

Immunohistochemical staining of cleaved caspase-3 in remote and adjacent myocardium. A, left: representative photograph of double staining with cleaved caspase-3 and WGA. Arrows signify a cleaved caspase-3-positive nonmyocyte and myocyte in the myocardium from a monkey with HF. The staining for cleaved caspase-3 is green. The outlines of myocytes were shown by WGA staining (red), and nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). A, right: quantification of cleaved caspase-3-positive cells. The number of cleaved caspase-3-positive nonmyocytes is significantly greater (*P < 0.05) than that of myocytes, both in the adjacent and remote areas of the myocardium. B, left: correlation of TUNEL and cleaved caspase-3 in chronic HF. In the representative photographs (B, top), TUNEL-positive myocytes and nonmyocytes (green) are shown. B, bottom: shown in green are a cleaved caspase-3-positive myocyte (left) and a nonmyocyte (right).

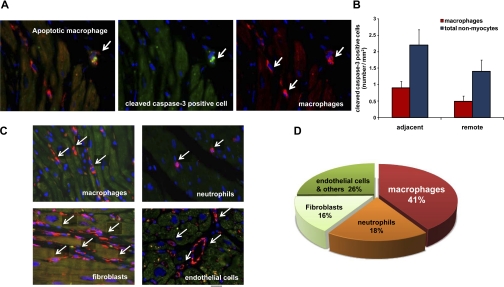

Characterization of nonmyocyte apoptosis.

Representative images of nonmyocytes in MI + HF are shown in Fig. 3C. We then determined the cell types of the apoptotic nonmyocytes. The percentage of apoptotic macrophages among total apoptotic nonmyocytes was 41% (n = 9) in the adjacent area (Fig. 3D) and 35% (n = 9) in the remote area. Representative apoptotic macrophages are shown in Fig. 3A. The percentage of apoptotic neutrophils among total TUNEL-positive nonmyocytes was 18%, and apoptotic fibroblast among total cleaved caspase-3-positive nonmyocytes was 16% in the adjacent area.

Fig. 3.

Dual immunostaining for macrophages and cleaved caspase-3 and cell types of nonmyocytes. A: representative photographs of apoptotic macrophages in the myocardium of a monkey with HF. The macrophages were stained with HAM56 (red) and cleaved caspase-3 (green). B: quantification of apoptotic macrophages among apoptotic nonmyocytes. C: different cell types of nonmyocytes (red); macrophages, neutrophils, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells. D: a quantitative distribution of cell types of apoptotic nonmyocytes. Values for each cell type were rounded to 2 integers, and, therefore, the sum on the chart is greater than 100%. If we had used 3 integers, this would most likely not have occurred.

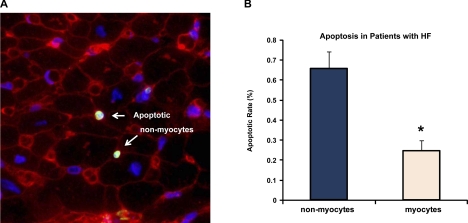

Data from patients with HF.

Biopsies from four patients with congestive cardiomyopathy and HF were examined. These patients had reduced LVEF (26 ± 7%) and high LV end-diastolic pressure (26 ± 7 mmHg), indicative of HF. In these biopsies, we also observed that the apoptotic rate was greater in nonmyocytes than in myocytes, although sufficient tissue was not available to permit identification of the nonmyocyte cell types. Representative images of apoptotic nonmyocytes in patients with HF are shown in Fig. 4A. The percentage of TUNEL-positive cells per nuclei was 0.66 ± 0.16% in nonmyocytes and 0.25 ± 0.09% in myocytes in the adjacent myocardium (P < 0.05) (n = 4) (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Apoptosis of myocardium in patients with HF. A: representative photograph of dual staining with TUNEL and WGA. Arrows signify TUNEL-positive nonmyocytes (positive nuclei are green). B: quantification of apoptotic rate (in %). The percentage of TUNEL-positive nonmyocytes was greater than that of myocytes (*P < 0.05) in the human cardiomyopathy tissue, similar to that observed in the monkey HF model (Fig. 1).

DISCUSSION

Since the initial studies demonstrating both increased apoptosis following MI (17) and increased apoptosis with HF (29), it has generally been assumed that apoptosis following chronic CAO leading to remodeling and HF occurs in myocytes. Some investigators have suggested that myocyte apoptosis is a critical step in the development of HF (32, 39, 42, 48, 51). Knowing that 75% (by cell number) of cells in the heart are nonmyocytes (21), we tested the hypothesis that apoptosis following chronic MI may not necessarily occur only in myocytes. Although numerous studies have found that apoptosis is increased following chronic MI (34, 36) or during the development of HF (10, 26, 32, 35, 38, 51), the prior studies identifying apoptosis in adjacent and remote myocardium following chronic MI indicated that the cell types were myocytes (2, 34, 36, 38). Our goal was to examine this in a primate model of chronic MI resulting in HF, since it is physiologically closer to patients than rodents, and confirm our data in myocardial biopsies from patients with HF. Nonmyocyte apoptosis has also been observed in other cardiovascular models that do not involve HF, e.g., acute ischemia and reperfusion (15, 40) and atherosclerosis (7).

The primate model of MI + HF, a model physiologically close to patients, was induced by a permanent occlusion of the mid-left anterior descending coronary artery, which resulted in chronic MI and cardiac decompensation, and was then followed 2–6 mo later by rapid pacing to induce severe HF. This novel experimental model of HF could be important for studies examining the pathogenesis of HF or its relief by therapeutic interventions.

In this model, we confirmed the findings of others that total apoptosis increased in MI and increased significantly further following the superimposition of HF. However, the major new finding of this study, and indeed a critical point, is that the majority of the apoptosis occurred in nonmyocytes. This observation challenges the general assumption that the development of HF following chronic MI involves only apoptosis of myocytes resulting in fewer contractile elements. We do not challenge the concept that apoptosis may be important in the development of HF, following chronic MI, but rather that its role may be different due to the fact that the majority of apoptosis occurs in nonmyocytes. A few other studies have noted that nonmyocytes underwent apoptosis following CAO, but these studies focused on the infarcted area after acute or chronic MI (19, 46). Many of the prior studies examined the role of apoptosis in scar formation (26, 47). For example, it was reported that the proportion of TUNEL-positive macrophages was 29.4% among TUNEL-positive interstitial cells in the infarcted area at 4 wk after MI (46). One study, which examined apoptosis in an experimental model of HF, observed that only a small fraction (roughly 10%) of apoptosis occurred in nonmyocytes (8).

The next goal of the current investigation was to determine the apoptotic cell types of nonmyocytes in the adjacent and remote myocardium following chronic MI and the development of HF. We found that the increased apoptosis in nonmyocytes occurred in a variety of cell types, was most abundant in macrophages, but was also observed in fibroblasts, neutrophils, and endothelial cells. It is also possible that a small fraction of the apoptotic cells could be stem cells or newly formed myocytes in the heart, since they would also be smaller than adult myocytes (25). It is known that nonmyocytes may play an important role in cardiac remodeling following MI (2, 30, 31, 45–47), and the increased activity of nonmyocytes, especially macrophages and granulocytes, could be beneficial in this setting (19, 47). The role of macrophages in the remodeling process following chronic MI and the development of HF are well recognized (22, 24). The depletion of macrophages using clodronate-containing liposomes impairs wound healing after myocardial cryoinjury (47), suggesting the necessity of macrophages for healing. Conversely, the injection of activated macrophages into the ischemic myocardium after acute MI improved LV remodeling and preserved LV function (24). Therefore, the infiltration of macrophages and other interstitial cells appears to exert a beneficial effect on remodeling following chronic MI, and apoptosis might be considered to have a negative impact on this process. However, since these cells have a relatively short life span in the heart after MI (49) and since apoptosis is a natural mechanism for their elimination (14, 46), the increased apoptosis of these cells would be expected as a natural consequence of their short life span.

In summary, the results of the current investigation require a rethinking of the role of apoptosis in the development of HF, particularly since it occurs predominantly in nonmyocytes. This was observed in patients with cardiomyopathy and HF as well as in a primate model of HF. Thus the mechanism of cardiac dysfunction in HF is not simply due to a loss of contractile elements through apoptosis in adjacent and remote myocardium. Rather, the HF is likely due most importantly to the extent of MI-induced necrosis and scar formation with secondary complex contributions from remodeling.

GRANTS

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants AG-027211, HL-033107, HL-059139, and HL-069752 (to S. F. Vatner) and HL-069020, AG-023137, and AG-014121 (to D. E. Vatner).

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbate A, Biondi-Zoccai GG, Baldi A. Pathophysiologic role of myocardial apoptosis in post-infarction left ventricular remodeling. J Cell Physiol 193: 145–153, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akasaka Y, Morimoto N, Ishikawa Y, Fujita K, Ito K, Kimura-Matsumoto M, Ishiguro S, Morita H, Kobayashi Y, Ishii T. Myocardial apoptosis associated with the expression of proinflammatory cytokines during the course of myocardial infarction. Mod Pathol 19: 588–598, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asai K, Kudej RK, Shen YT, Yang GP, Takagi G, Kudej AB, Geng YJ, Sato N, Nazareno JB, Vatner DE, Natividad F, Bishop SP, Vatner SF. Peripheral vascular endothelial dysfunction and apoptosis in old monkeys. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 20: 1493–1499, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asai K, Kudej RK, Takagi G, Kudej AB, Natividad F, Shen YT, Vatner DE, Vatner SF. Paradoxically enhanced endothelin-B receptor-mediated vasoconstriction in conscious old monkeys. Circulation 103: 2382–2386, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baldi A, Abbate A, Bussani R, Patti G, Melfi R, Angelini A, Dobrina A, Rossiello R, Silvestri F, Baldi F, Di Sciascio G. Apoptosis and post-infarction left ventricular remodeling. J Mol Cell Cardiol 34: 165–174, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bialik S, Geenen DL, Sasson IE, Cheng R, Horner JW, Evans SM, Lord EM, Koch CJ, Kitsis RN. Myocyte apoptosis during acute myocardial infarction in the mouse localizes to hypoxic regions but occurs independently of p53. J Clin Invest 100: 1363–1372, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cai W, Devaux B, Schaper W, Schaper J. The role of Fas/APO 1 and apoptosis in the development of human atherosclerotic lesions. Atherosclerosis 131: 177–186, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cesselli D, Jakoniuk I, Barlucchi L, Beltrami AP, Hintze TH, Nadal-Ginard B, Kajstura J, Leri A, Anversa P. Oxidative stress-mediated cardiac cell death is a major determinant of ventricular dysfunction and failure in dog dilated cardiomyopathy. Circ Res 89: 279–286, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Z, Chua CC, Ho YS, Hamdy RC, Chua BH. Overexpression of Bcl-2 attenuates apoptosis and protects against myocardial I/R injury in transgenic mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280: H2313–H2320, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Condorelli G, Morisco C, Stassi G, Notte A, Farina F, Sgaramella G, de Rienzo A, Roncarati R, Trimarco B, Lembo G. Increased cardiomyocyte apoptosis and changes in proapoptotic and antiapoptotic genes bax and bcl-2 during left ventricular adaptations to chronic pressure overload in the rat. Circulation 99: 3071–3078, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crow MT, Mani K, Nam YJ, Kitsis RN. The mitochondrial death pathway and cardiac myocyte apoptosis. Circ Res 95: 957–970, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Boer RA, van Veldhuisen DJ, van der Wijk J, Brouwer RM, de Jonge N, Cole GM, Suurmeijer AJ. Additional use of immunostaining for active caspase 3 and cleaved actin and PARP fragments to detect apoptosis in patients with chronic heart failure. J Card Fail 6: 330–337, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fliss H, Gattinger D. Apoptosis in ischemic and reperfused rat myocardium. Circ Res 79: 949–956, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frangogiannis NG The immune system and cardiac repair. Pharmacol Res 58: 88–111, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freude B, Masters TN, Robicsek F, Fokin A, Kostin S, Zimmermann R, Ullmann C, Lorenz-Meyer S, Schaper J. Apoptosis is initiated by myocardial ischemia and executed during reperfusion. J Mol Cell Cardiol 32: 197–208, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garg S, Narula J, Chandrashekhar Y. Apoptosis and heart failure: clinical relevance and therapeutic target. J Mol Cell Cardiol 38: 73–79, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gottlieb RA, Burleson KO, Kloner RA, Babior BM, Engler RL. Reperfusion injury induces apoptosis in rabbit cardiomyocytes. J Clin Invest 94: 1621–1628, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goussev A, Sharov VG, Shimoyama H, Tanimura M, Lesch M, Goldstein S, Sabbah HN. Effects of ACE inhibition on cardiomyocyte apoptosis in dogs with heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 275: H626–H631, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayakawa K, Takemura G, Kanoh M, Li Y, Koda M, Kawase Y, Maruyama R, Okada H, Minatoguchi S, Fujiwara T, Fujiwara H. Inhibition of granulation tissue cell apoptosis during the subacute stage of myocardial infarction improves cardiac remodeling and dysfunction at the chronic stage. Circulation 108: 104–109, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Imahashi K, Schneider MD, Steenbergen C, Murphy E. Transgenic expression of Bcl-2 modulates energy metabolism, prevents cytosolic acidification during ischemia, and reduces ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circ Res 95: 734–741, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jugdutt BI Ventricular remodeling after infarction and the extracellular collagen matrix: when is enough enough? Circulation 108: 1395–1403, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lambert JM, Lopez EF, Lindsey ML. Macrophage roles following myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol 130: 147–158, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee P, Sata M, Lefer DJ, Factor SM, Walsh K, Kitsis RN. Fas pathway is a critical mediator of cardiac myocyte death and MI during ischemia-reperfusion in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 284: H456–H463, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leor J, Rozen L, Zuloff-Shani A, Feinberg MS, Amsalem Y, Barbash IM, Kachel E, Holbova R, Mardor Y, Daniels D, Ocherashvilli A, Orenstein A, Danon D. Ex vivo activated human macrophages improve healing, remodeling, and function of the infarcted heart. Circulation 114: I94–I100, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leri A, Kajstura J, Anversa P. Cardiac stem cells and mechanisms of myocardial regeneration. Physiol Rev 85: 1373–1416, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Y, Takemura G, Kosai K, Takahashi T, Okada H, Miyata S, Yuge K, Nagano S, Esaki M, Khai NC, Goto K, Mikami A, Maruyama R, Minatoguchi S, Fujiwara T, Fujiwara H. Critical roles for the Fas/Fas ligand system in postinfarction ventricular remodeling and heart failure. Circ Res 95: 627–636, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsui T, Tao J, del Monte F, Lee KH, Li L, Picard M, Force TL, Franke TF, Hajjar RJ, Rosenzweig A. Akt activation preserves cardiac function and prevents injury after transient cardiac ischemia in vivo. Circulation 104: 330–335, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miao W, Luo Z, Kitsis RN, Walsh K. Intracoronary, adenovirus-mediated Akt gene transfer in heart limits infarct size following ischemia-reperfusion injury in vivo. J Mol Cell Cardiol 32: 2397–2402, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Narula J, Haider N, Virmani R, DiSalvo TG, Kolodgie FD, Hajjar RJ, Schmidt U, Semigran MJ, Dec GW, Khaw BA. Apoptosis in myocytes in end-stage heart failure. N Engl J Med 335: 1182–1189, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niu J, Azfer A, Kolattukudy PE. Monocyte-specific Bcl-2 expression attenuates inflammation and heart failure in monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1)-induced cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Res 71: 139–148, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okada H, Takemura G, Kosai K, Li Y, Takahashi T, Esaki M, Yuge K, Miyata S, Maruyama R, Mikami A, Minatoguchi S, Fujiwara T, Fujiwara H. Postinfarction gene therapy against transforming growth factor-beta signal modulates infarct tissue dynamics and attenuates left ventricular remodeling and heart failure. Circulation 111: 2430–2437, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olivetti G, Abbi R, Quaini F, Kajstura J, Cheng W, Nitahara JA, Quaini E, Di Loreto C, Beltrami CA, Krajewski S, Reed JC, Anversa P. Apoptosis in the failing human heart. N Engl J Med 336: 1131–1141, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olivetti G, Quaini F, Sala R, Lagrasta C, Corradi D, Bonacina E, Gambert SR, Cigola E, Anversa P. Acute myocardial infarction in humans is associated with activation of programmed myocyte cell death in the surviving portion of the heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol 28: 2005–2016, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palojoki E, Saraste A, Eriksson A, Pulkki K, Kallajoki M, Voipio-Pulkki LM, Tikkanen I. Cardiomyocyte apoptosis and ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280: H2726–H2731, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prabhu SD, Wang G, Luo J, Gu Y, Ping P, Chandrasekar B. Beta-adrenergic receptor blockade modulates Bcl-X(S) expression and reduces apoptosis in failing myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol 35: 483–493, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qin F, Liang MC, Liang CS. Progressive left ventricular remodeling, myocyte apoptosis, and protein signaling cascades after myocardial infarction in rabbits. Biochim Biophys Acta 1740: 499–513, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sabbah HN, Sharov VG, Gupta RC, Todor A, Singh V, Goldstein S. Chronic therapy with metoprolol attenuates cardiomyocyte apoptosis in dogs with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 36: 1698–1705, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sam F, Sawyer DB, Chang DL, Eberli FR, Ngoy S, Jain M, Amin J, Apstein CS, Colucci WS. Progressive left ventricular remodeling and apoptosis late after myocardial infarction in mouse heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 279: H422–H428, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saraste A, Pulkki K, Kallajoki M, Heikkila P, Laine P, Mattila S, Nieminen MS, Parvinen M, Voipio-Pulkki LM. Cardiomyocyte apoptosis and progression of heart failure to transplantation. Eur J Clin Invest 29: 380–386, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scarabelli T, Stephanou A, Rayment N, Pasini E, Comini L, Curello S, Ferrari R, Knight R, Latchman D. Apoptosis of endothelial cells precedes myocyte cell apoptosis in ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circulation 104: 253–256, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharov VG, Sabbah HN, Ali AS, Shimoyama H, Lesch M, Goldstein S. Abnormalities of cardiocytes in regions bordering fibrous scars of dogs with heart failure. Int J Cardiol 60: 273–279, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharov VG, Sabbah HN, Shimoyama H, Goussev AV, Lesch M, Goldstein S. Evidence of cardiocyte apoptosis in myocardium of dogs with chronic heart failure. Am J Pathol 148: 141–149, 1996. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takagi G, Asai K, Vatner SF, Kudej RK, Rossi F, Peppas A, Takagi I, Resuello RR, Natividad F, Shen YT, Vatner DE. Gender differences on the effects of aging on cardiac and peripheral adrenergic stimulation in old conscious monkeys. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H527–H534, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takemura G, Fujiwara H. Morphological aspects of apoptosis in heart diseases. J Cell Mol Med 10: 56–75, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takemura G, Fujiwara H. Role of apoptosis in remodeling after myocardial infarction. Pharmacol Ther 104: 1–16, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takemura G, Ohno M, Hayakawa Y, Misao J, Kanoh M, Ohno A, Uno Y, Minatoguchi S, Fujiwara T, Fujiwara H. Role of apoptosis in the disappearance of infiltrated and proliferated interstitial cells after myocardial infarction. Circ Res 82: 1130–1138, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van Amerongen MJ, Harmsen MC, van Rooijen N, Petersen AH, van Luyn MJ. Macrophage depletion impairs wound healing and increases left ventricular remodeling after myocardial injury in mice. Am J Pathol 170: 818–829, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van Empel VP, Bertrand AT, Hofstra L, Crijns HJ, Doevendans PA, De Windt LJ. Myocyte apoptosis in heart failure. Cardiovasc Res 67: 21–29, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vandervelde S, van Amerongen MJ, Tio RA, Petersen AH, van Luyn MJ, Harmsen MC. Increased inflammatory response and neovascularization in reperfused vs. nonreperfused murine myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Pathol 15: 83–90, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Veinot JP, Gattinger DA, Fliss H. Early apoptosis in human myocardial infarcts. Hum Pathol 28: 485–492, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wencker D, Chandra M, Nguyen K, Miao W, Garantziotis S, Factor SM, Shirani J, Armstrong RC, Kitsis RN. A mechanistic role for cardiac myocyte apoptosis in heart failure. J Clin Invest 111: 1497–1504, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zidar N, Dolenc-Strazar Z, Jeruc J, Stajer D. Immunohistochemical expression of activated caspase-3 in human myocardial infarction. Virchows Arch 448: 75–79, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]