Abstract

Sex influences adrenal glucocorticoid responses to ACTH in experimental animals. Whether similar sex differences operate in humans is unknown. To test this notion, we estimated ACTH-cortisol dose-response properties analytically in 48 healthy adults (n = 22 women, n = 26 men), ages 18–77 yr, body mass index (BMI) 18–32 kg/m2, previously studied at two medical centers. Plasma ACTH and cortisol concentrations were measured every 10 min for 24 h. The 145 sample pairs were used in each subject to estimate ACTH-cortisol drive via a logistic function. Statistical analyses revealed that 24-h cortisol secretion (>82% pulsatile) fell in men (r = −0.38, P = 0.028) and rose in women (r = +0.37, P = 0.045) with age (P = 0.01 sex effect). The mechanisms involved decreased ACTH efficacy with age in men (r = −0.35, P = 0.04), and increased ACTH efficacy with age in women (r = +0.42, P = 0.025) [P = 0.009 sex effect]. ACTH potency diminished with higher BMI in men (r = +0.38, P = 0.029) and in the cohort as a whole (r = 0.34, P = 0.0085). These outcomes demonstrate that sex, age, and BMI modulate selective properties of endogenous ACTH-cortisol drive in humans, thereby indicating the need to control these three major variables in experimental comparisons.

Keywords: adrenal, aging, sex, men, women, secretion

in experimental animals, estrogens sensitize and androgens mute corticotropic-axis responses to stress (15, 21, 60, 75). Data in the human are indirect and controversial. For example, in one study in eight hypogonadal men, cortisol production rates were normal (77), whereas in another study, leuprolide-induced gonadoprivation unmasked greater ACTH and cortisol responses to corticotropin-releasing hormones (CRH) in young and middle-aged men than premenopausal women (59). Analyses of young hypogonadal adults further suggest that serotoninergic agonists and psychosocial stress stimulate greater corticotropic-adrenal responses in young men than young women (49, 61). On the other hand, cortisol concentrations are reportedly higher in women than men during early sleep, dexamethasone suppression, interleukin-6 infusion, growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH) injection, CRH stimulation, physostigmine administration, and psychosocial stress (8, 43, 48, 64, 78).

In some investigations, age appears to augment ACTH and cortisol release in both sexes after selected stressors (8, 26, 30, 43, 48). Nonetheless, other studies have reported no age or sex effects (19, 29, 32, 46, 48, 53). Certain of these discrepancies could be due to ethnicity differences (14, 80), time-of-day effects (72), measurement of cortisol in plasma, saliva, or urine (41, 43, 58), nature of stressor (54, 71), basal vs. stressed states (2, 81), concurrent obesity (1, 23, 33, 67, 68, 70), estrogen use (46), stage of menstrual cycle (40), dietary carbohydrate intake (65), and potential sex-by-age interactions (78). The last consideration has been assessed in untreated children (28) and in adults following sequential dexamethasone/CRH exposure (30).

To date, no clinical studies have appraised the individual and interactive effects of sex and age on adrenal responses to endogenous pulses of ACTH. Indirect estimates of adrenal responsivity have used the ratio of plasma cortisol to ACTH concentrations, and thereby inferred elevated, equivalent, or reduced cortisol/ACTH ratios in older compared with young adults and/or in women compared with men (2, 8, 19, 26, 33, 64, 81). However, interpretation of cortisol/ACTH ratios assumes a simple linear relationship between ACTH and cortisol concentrations. This simplifying assumption is demonstrably incorrect, inasmuch as increasing ACTH concentrations (or doses) drive nonlinear (asymptotic, saturable) increases in cortisol concentrations in animals and humans (51, 52, 69).

A recent analytical method allows noninvasive estimation of physiological (nonlinear) dose-response functions from serially sampled hormone effector-response pairs, such as LH and testosterone, GnRH, and LH, or ACTH and cortisol without the injection of hormone agonists, antagonists, or labeled compounds (13, 34). This new tool is used to assess the unknown effects of sex and age on specific attributes of ACTH's concentration-dependent drive of cortisol secretion in 48 healthy adults over 24 h.

METHODS

Overview

Paired 10-min plasma ACTH and cortisol concentration-time series collected over 24 h in 48 healthy adults from two centers were reanalyzed (11, 47). The present analysis does not overlap with earlier outcomes or methods in any manner. ACTH efficacy and potency were estimated analytically in each subject, then regressed on age in women and men. The null hypothesis was that sex does not determine the effect of age on endogenous ACTH efficacy or potency.

Human Subjects

Healthy, unmedicated volunteers participated in the study (26 men and 22 women). Each subject provided written informed consent, and the protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board. The age range was 18–77 yr. Participants maintained conventional work and sleeping patterns and reported no recent (within 10 days) transmeridian travel, weight change (>2 kg in 6 wk), shift work, intercurrent psychosocial stress, prescription medication use, substance abuse, neuropsychiatric illness, or acute or chronic systemic disease. A complete medical history, physical examination, and screening tests of hematological, renal, hepatic, metabolic, and endocrine function were normal. No subject had been exposed to glucocorticoids within the preceding 3 mo.

Volunteers were admitted to the Study Unit the evening before sampling for adaptation. Premenopausal women were studied in the follicular phase. No women were receiving estrogens, and no men were receiving androgens. Ambulation was permitted to the lavatory only. Vigorous exercise, daytime sleep, snacks, caffeinated beverages, and cigarette smoking were disallowed. Meals were provided at 0800, 1230, and 1730, and room lights were turned off between 2200 and 2400 depending upon individual sleeping habits. Blood samples (2.0 ml) were withdrawn at 10-min intervals for 24 h beginning either at midnight (17 subjects) or at 0900 (31 subjects). Blood was collected in prechilled siliconized tubes containing EDTA (ACTH) or heparin (cortisol), centrifuged at 4 C to separate plasma, and frozen at −20°C within 30 min of collection. Total blood loss was < 360 ml. Volunteers were compensated for the time spent in the study.

Laboratory Assays

Plasma ACTH concentrations were quantitated in duplicate by high-sensitivity (3 ng/l) and high-specificity double-monoclonal immunoradiometric assay, using reagents from Nichols Diagnostics Institute (San Clemente, CA) between the years 1994 and 1997. Median within- and between-assay coefficients of variation of (CVs) were 5.3 and 6.5%, respectively. Cortisol was assayed by high-sensitivity (25 nmol/l) solid-phase RIA (Sorin Biomedica, Milan, Italy). Intra-assay and interassay CVs were 5.1 and 6.4%, respectively. No samples were undetectable in either assay. Current ACTH assays may give similar or considerably lower results that the erstwhile Nichols assay (57, 79).

Analytical Formulation

The analytical objective was to estimate properties of the in vivo dose-response relationship mediating pulsatile ACTH concentration-dependent drive of cortisol secretion over 24 h in individual subjects without administering an agonist, antagonist, or labeled marker (34, 35).

The core model equations provide a representation of admixed basal and pulsatile secretion, cortisol subject-specific slow-phase half-lives with a fixed rapid-phase half-life of 2.4 min comprising 37% of the decay amplitude, allowable random effects on successive cortisol secretory-burst mass values, and experimental uncertainty due to sample withdrawal, processing, and assay (35, 36). Key features are highlighted below.

Secretion and elimination functions.

Time-varying cortisol concentrations, X(t), can be described by the solution to a set of coupled differential equations incorporating basal (time-invariant) and pulsatile (burst-like) secretion and exponential elimination. Total secretion is given by the sum of basal and pulsatile: Z (•) = β0 + P (•), as follows:

|

(1) |

“concentration due to basal secretion” + “concentration due to pulsatile secretion,” where a is the proportion of rapid to total elimination (0.37), α1 and α2 are the respective rate constants of the rapid (0.298) and slow (estimated) elimination phases, X(0) is the starting hormone concentration, β0 is the basal secretion rate, t time and P(r)dr are the instantaneous pulsatile secretion rate over the infinitesimal time interval (r, r + dr) (35, 36).

The function defining pulsatile cortisol secretion was given by

|

(2) |

where Ψ(s) denotes the waveform function (burst shape), a three-parameter generalized gamma probability distribution normalized to integrate to unity; Mj denotes the (deterministic plus random) mass of cortisol released per unit distribution volume in the jth burst; η0 is the fixed basal cortisol synthesis rate in the adrenal gland; η1 is the rate of additional cortisol accumulation over the time interval, Tj - Tj−1; and, Aj are random effects on the mass of the jth cortisol burst. Asymmetric and symmetric (e.g., Gaussian) secretion events are well approximated by the three-parameter gamma density [above psi function]. Such flexibility is important, inasmuch as discrete pulses of ACTH evoke rapid onset and prolonged cortisol secretion in vivo in the sheep, rat, and dog and in vitro during perifusion of adrenal cells (5, 25).

Dose-response estimation.

A statistical basis exists for analytical estimation of four-parameter logistic functions relating time-varying agonist (ACTH) concentrations to target-gland (adrenal cortisol) secretion rates (34–36). One parameter is simply basal secretion. The two main parameters are efficacy and potency, as defined in Primary model parameters. Experimental validation was accomplished by frequent (5 min) and extended (4–12 h) direct sampling of hypothalamo-pituitary portal and jugular venous blood in the unrestrained, conscious unmedicated sheep and horse, and repetitive sampling (every 20 min for 17 h) of LH and testosterone concentrations in the human spermatic vein (34, 35). Statistical verification was by formal mathematical proof of unbiased asymptotic properties of maximum likelihood-based estimates (MLE) of all parameters simultaneously (13). The motivation for and detailed methodological steps used in estimating a four-parameter logistic dose-response function are given for the reader by Keenan and Veldhuis (37).

Primary model parameters.

Primary analytical outcomes include 1) basal (nonpulsatile) cortisol secretion (μmol/l/24 h); 2) reconstructed (reconvolved) cortisol-concentration time series; 3) slow-phase half-life (min) of cortisol; 4) the mass of cortisol (μmol/l) secreted per burst; 5) cortisol secretory-event frequency (per 24 h), and 6) specific dose-response properties defined by efficacy (asymptotically projected maximal ACTH-stimulated cortisol secretion rate, nmol·l−1·min−1); and ED50 or potency (ACTH concentration in pmol/l driving half-maximal cortisol secretion). Secondary measures were basal (nonpulsatile) cortisol secretion and adrenal sensitivity (maximal positive slope of the ACTH concentration-cortisol secretion relationship) (13, 35, 36). Random effects on mean dose-response efficacy (averaged across all ACTH pulses in each subject) were permitted, but not required, on a pulse-by-pulse basis over 24 h in each subject (34). This allows for possible biological variability of the ACTH concentration-cortisol secretion relationship in any given individual over 24 h. The foregoing ensemble of parameters is evaluated simultaneously, conditioned statistically on a priori estimates of ACTH pulse-onset times, as described, wherein cortisol secretory bursts inherit pulse times from ACTH. Cortisol mass units are normalized per liter distribution volume (nmol/l or μmol/l), given that reported cortisol distribution volumes vary absolutely from 4.8 to 44 liters (nominal literature mean 8.2 l/m2) (73). Secretion rates would need to be multiplied by each person's independently determined distribution volume to obtain absolute production rates. Hence, the term secretion (rather than production rate) is employed here.

Statistics.

Data are given as the mean ± SE (median). An unpaired two-tailed Student's t-statistic was used to compare outcomes in men and women. Linear regression analysis and Pearson's correlation coefficient were applied to relate dose-response parameter estimates to age or body mass index (BMI). Significance was construed for P < 0.05.

RESULTS

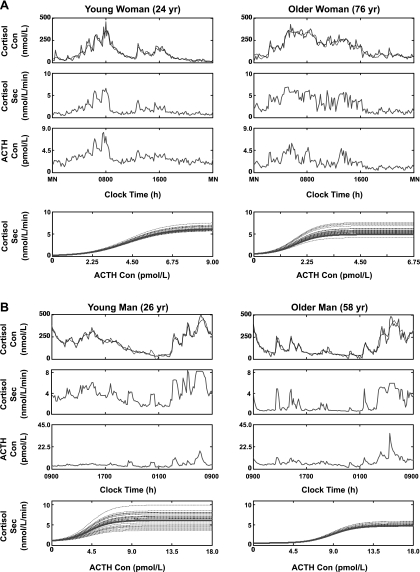

General subject characteristics are given in Table 1. Figure 1 depicts measured (dark line) and model-estimated (lighter line) plasma cortisol concentrations sampled every 10 min for 24 h in a 24- and a 76 yr-old woman (A, top) and in a 26- and a 58-yr-old man (B, top). Matching cortisol secretion rate estimates (upper middle) and measured (untransformed) ACTH concentrations (lower middle) are given. The analytical model relates measured ACTH concentrations (pmol/l) via an estimated four-parameter dose-response function to cortisol secretion rates (nmol·l−1·min−1) calculated simultaneously (bottom). In each subject, multiple dose-response curves are plotted, each with a different efficacy. The curves reflect random effects on the mean efficacy (solid line) due to small response variations among different ACTH/cortisol pulse pairs in that person (interrupted lines). To be representative, profiles include data from midnight to midnight (A) and from 0900 to 0900 (B). Axes are scaled to highlight differences in the dynamics.

Table 1.

Baseline Subject Characteristics

| Men (n = 26) | Women (n = 22) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 45±2.5 (46) | 46±3.0 (45) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26±0.60 (25) | 24±0.85 (23) |

| ACTH,* pmol/l | 4.7±0.29 (4.7) | 3.3±0.27 (3.3) |

| Cortisol,* nmol/l | 198±11 (184) | 170±10 (172) |

Data are expressed as means ± SE (median). Men and women did not differ. BMI, body mass index.

Twenty-four hour mean value in each subject.

Fig. 1.

Illustrative ACTH-cortisol concentration-secretion profiles and dose-response estimates in a young and older woman (A) and a young and older man (B). Top row: measured plasma cortisol concentrations sampled every 10 min over 24 h (dark lines) and model-estimated values (light lines) (multiply nmol/l cortisol by 0.0363 to obtain μg/dl). Upper-middle row: cortisol secretion rates. Lower-middle row: ACTH concentrations (multiply pmol/l by 4.5 to convert to ng/l or pg/ml). Bottom row: ACTH concentration dose-cortisol secretory-response curves reconstructed for the set of ACTH pulses identified in each subject (interrupted lines). The solid dark line is the subject's mean dose-response estimate over 24 h. Note different scales to visualize the dynamics.

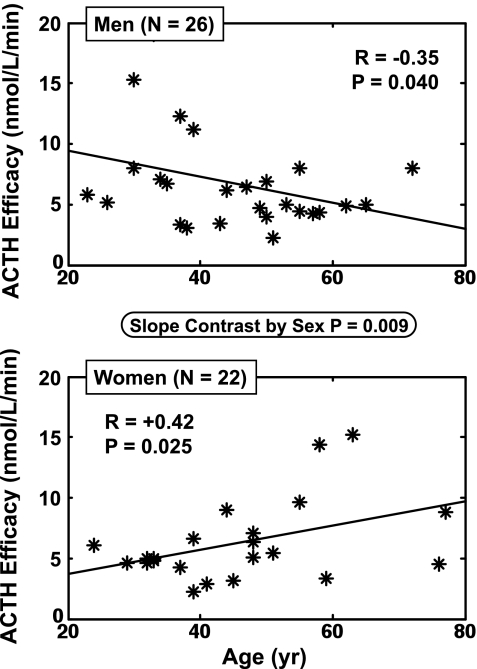

Linear regression analysis was used to evaluate whether sex influences how age alters ACTH-cortisol dose-responsiveness for 1) all 48 subjects, 2) men only (n = 26), and 3) women only (n = 22): Fig. 2. The two primary dose-response parameters were ACTH ED50 (potency) and ACTH efficacy (asymptotically projected maximal cortisol-secretory response). ACTH efficacy correlated with age negatively in men (P = 0.025) and positively in women (P = 0.040). The slopes in men and women differed significantly (P = 0.009 by two-tailed Student's t-test). Thus, sex affects the age dependence of ACTH efficacy in this cohort. This outcome was specific, since regressions of ACTH ED50, and secondarily adrenal sensitivity and basal cortisol secretion on age, yielded no age or sex dependencies (Table 2). The opposite effects of age on ACTH efficacy in men and women were reflected in analogous differences in both total (pulsatile plus basal) daily cortisol secretion (sex effect P = 0.01) and the mass of cortisol secreted per burst (sex effect: P = 0.03). In particular, age diminished ACTH drive in men (P = 0.028 for total cortisol secretion, P = 0.045 for cortisol mass per burst), whereas age augmented total cortisol secretion in women (P = 0.045). Neither age nor sex affected percentage pulsatile cortisol secretion (mean 84 ± 1.3%; n = 48), cortisol half-life (53 ± 2.5 min) or secretory-burst frequency (21 ± 1 pulses/day).

Fig. 2.

Opposite impact of age (independent variable) on ACTH efficacy (asymptotically maximal ACTH-stimulated pulsatile cortisol secretory rate) in men (n = 26, top) and women (n = 22, bottom). Pearson's product-moment correlation coefficients are shown for the regressions. The P value in the ellipse denotes the sex difference in slopes.

Table 2.

Summary of Regression Statistics on Age

|

Men (n = 26) |

Women (n = 22)

|

Gender Comparison

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Cortisol Secretion | Cortisol Mass per Pulse | ACTH Efficacy | Total Cortisol Secretion | Cortisol Mass per Pulse | ACTH Efficacy | Total Cortisol Secretion | Cortisol Mass per Pulse | ACTH Efficacy | |

| Correlation | −0.38 | −0.34 | −0.35 | 0.37 | 0.29 | 0.42 | |||

| Slope | −66.7 | −3.0 | −0.24 | 45.3 | 1.7 | 0.22 | |||

| SE | 33.1 | 1.7 | 0.13 | 25.5 | 1.2 | 0.11 | |||

| t | −2.02 | −1.76 | −1.82 | 1.78 | 1.37 | 2.09 | −2.68 | −2.23 | −2.73 |

| df | 24 | 24 | 24 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 40 | 39 | 41 |

| P value | 0.028 | 0.045 | 0.04 | 0.045 | 0.09 | 0.025 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.009 |

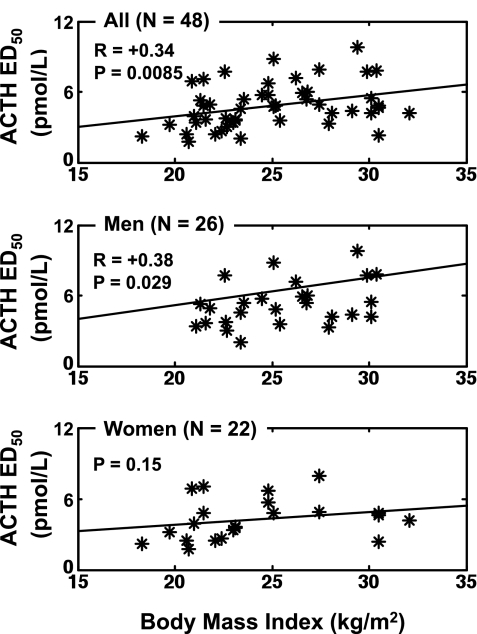

A secondary postulate was that BMI influences ACTH-cortisol dose-response coupling. As depicted in Fig. 3, BMI was a significantly positive correlate of ACTH ED50 (potency) in the cohort as a whole (r = 0.34, P = 0.0085, n = 48). The same was true in men (r = 0.38, P = 0.029), but not in women (P = 0.15). The male/female slope difference for the BMI effect on ACTH potency was not significant. Sensitivity to ACTH, ACTH efficacy, basal cortisol secretion, cortisol half-life, total cortisol secretion, cortisol secretory-burst frequency, and mass were unrelated to BMI over the range 18–32 kg/m2.

Fig. 3.

Impact of body mass index (BMI) in the combined cohort (top), in men (middle) but not women (bottom) on the ED50 of the ACTH-cortisol dose-response function. Data are presented as described in Fig. 2, except that the independent variable is BMI. The ED50 is the concentration of ACTH driving one-half maximal cortisol secretion.

DISCUSSION

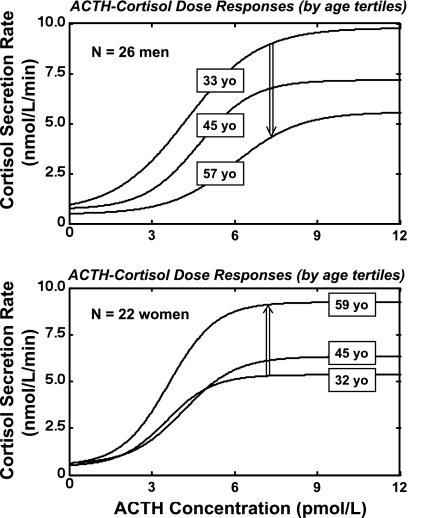

The present paradigm complements a concept of dose-dependent ACTH-cortisol drive (here designated as feedforward) developed in 1983 by Keller-Wood et al. (39) and based upon 40-min infusions of dose-varying α-1,24-ACTH in dogs. The current paradigm differs by comprising paired 24-h endogenous ACTH and cortisol times series based upon 10-min sampling (145 samples of both hormones), and a noninvasive analytical model to estimate feedforward (stimulatory) properties of endogenous ACTH-concentration pulses on cortisol secretion in 48 healthy adults ages 18–77 yr with BMI's of 18–32 kg/m2. Salient outcomes are that sex determined the effects of age on 1) total (pulsatile plus basal) daily cortisol secretion, 2) the stimulatory efficacy of ACTH, and 3) the mean amount (mass) of cortisol secreted per burst. Each of the three measures increased with age in women, but decreased with age in men. Figure 4 illustrates this by showing ACTH-cortisol dose-response functions by age tertile and sex. The opposite effects of age on ACTH efficacy in men and women are not readily explicable by the known trend of cortisol-binding globulin (CBG) concentrations to decline with age in both sexes and to decrease in a low estrogenic milieu in women (41, 55, 66). The sex effects were selective, because sex did not affect ACTH potency, the slow-phase half-life of cortisol, basal (nonpulsatile) cortisol secretion, secretory-burst frequency, or estimated adrenal sensitivity to ACTH (Table 3).

Fig. 4.

Illustrative mean dose-response functions estimated for ACTH-cortisol drive in 26 men (top) and 22 women (bottom) assessed by tertiles of age. The boxed number on each curve is the mean age for that tertile in that sex. The broad double-vertical arrows indicate that estimated ACTH efficacy falls with age in men (top) but rises with age in women (bottom). Efficacy denotes the asymptotically maximal pulsatile cortisol-secretory response to ACTH as estimated by the model.

Table 3.

Summary of Estimated ACTH-Cortisol Dose-Response Parameters

| Men (n = 26) | Women (n = 22) | |

|---|---|---|

| ACTH: efficacy, nmol/l/min | 6.7 (5.5)±0.77 | 6.3 (5.1)±0.72 |

| ED50 (potency), min | 5.3 (5.1)±0.38 | 4.2 (4.0)±0.38 |

| Cortisol: total secretion, nmol/l/day | 1297 (1132)±119 | 1132 (1049)±102 |

| Cortisol: basal secretion, nmol/l/day | 243 (226)±33 | 207 (190)±19 |

| Mass per pulse, nmol/l | 63 (52)±6.1 | 55 (47)±4.7 |

| Cortisol: slow half-life, pmol/l | 57 (56)±3.1 | 45 (45)±2.9 |

Data are expressed as means (median) ± SE. MPP, mass per pulse.

The strong effects of sex on age's determination of total cortisol secretion were reflected in corresponding differences in the amount of cortisol secreted per burst. ACTH efficacy in the present construction denotes analytically extrapolated asymptotically maximal pulsatile cortisol secretion. In the cohort evaluated here, cortisol secretory-burst size (nanomoles of cortisol released per ACTH-associated secretory burst per liter distribution volume) increased in parallel with ACTH efficacy. This finding is not dissimilar to the net experimental outcome in dogs, wherein higher ACTH doses increase total cortisol secretion by initially increasing the height and subsequently also prolonging the duration of the cortisol secretory response, thereby together increasing total cortisol secretion (39). In the present model, although the duration of individual cortisol pulses was not estimable, the total amount (mass) of cortisol secreted per burst is the integral of the secretion pulse (similar to a height-width product) (37). The estimated mass per pulse is multiplied by the number of ACTH pulses to obtain total pulsatile cortisol secretion. ACTH pulse frequency did not change with age and did not differ by sex. Thus, age and sex primarily modulate the amount of cortisol secreted in bursts. New analytical models will be needed to discern the extent to which individual cortisol secretory-burst shape (waveform) and size (amplitude) are determined by ACTH concentrations. Since our data were not obtained after imposition of stressors, we cannot readily predict how ACTH-cortisol relationships would change with age and sex in the presence of illness, disease, or experimental stress.

The basis for higher estimated ACTH efficacy in young men and aging women is not yet known. This cannot be explained by CBG differences, since CBG is actually greater in young women than young men, and declines with age in both sexes (41, 55, 66). Estrogen potentiates and testosterone represses adrenal steroidogenic responses to exogenous ACTH in animal models (15, 60). The same sex-steroid effects on adrenal responsivity to ACTH have not been demonstrated directly in primates. However, the observation that sex differences in cortisol availability exist even in prepubertal children and hypogonadal adults (28, 59) would suggest that either sex steroids do not mediate sex differences in adrenal responsiveness or that their effects are exerted early in life and sustained. Further studies will be required to address these considerations.

The rise in calculated ACTH efficacy with age in women is consistent with measurements of cortisol concentrations and production rates in several clinical studies (27, 43, 48, 48, 54). Conversely, the fall in ACTH efficacy with age in men is consistent with declining cortisol levels inferred in other investigations (2, 16, 24, 40, 43, 49, 55, 61, 63, 64, 78). Our finding of opposing effects of age on ACTH-cortisol efficacy in men and women explain the absence of an overall effect of age when data from both sexes are considered together. The present outcomes supported by some (12, 32, 46, 53, 62, 81), but not other (18, 48, 55, 70), indirect analyses. Contradictory earlier data may reflect in part the influence of stressor type on sex differences (71); small numbers of subjects studied (40, 59, 77, 78); morning vs. late-day sampling (72); and possible effects of ethnicity (14, 80).

BMI was used as a surrogate of relative adiposity. Previous reports suggest variously that BMI does not predict (53), predicts decreased (33, 67, 70), and predicts increased (1, 20, 23, 68, 76) cortisol concentrations, production and/or metabolism. The current analyses show that higher BMI in men is associated with lower calculated ACTH potency (higher ED50), but no difference in 24-h cortisol secretion. The decline in ACTH potency with increased BMI cannot be readily explained by changes in CBG concentrations, which change principally with massive increases in BMI in unmedicated and nonhormonally treated adults (43, 45, 50). On technical grounds, variations in CBG could influence efficacy calculations but would not affect analytical estimates of potency as determined here (35, 37).

Caveats include the need to extend studies to multiple ethnic groups; confirm analytical estimates using dose-varying pulses of exogenous ACTH delivered intravenously in a diurnal pattern; simultaneously determine cortisol distribution volumes in each subject; assess the impact of experimentally controlled CBG concentrations on endogenous cortisol kinetics; evaluate larger cohorts to subanalyze changes within sex; assess the degree of interdependence of the effects of age and BMI; and test directly the effect(s) of clamped sex-steroid milieus on ACTH-cortisol dose responsiveness.

In a group of 24 men and 30 women (ages 19–70 yr, BMI 19–64 kg/m2), daily cortisol production rates ranged from 6.6 to 39 μmol/m2 based upon isotope-dilution mass spectrometry (55, 56). In the present sample of 26 men and 22 women (ages 21–79 yr, BMI 19–32 kg/m2), analytical estimates predict approximate daily pulsatile cortisol production rates of 15.5 and 17.0 μmol in men and women [assuming nominal mean cortisol distribution volumes of 8.4 and 8.0 l/m2 and body surface areas of 1.73 and 1.60 m2, respectively (9, 42)]. In contrast, analytically estimated ACTH efficacy (defined by asymptotically maximal ACTH-stimulated pulsatile cortisol secretion) would be 136 and 113 μmol/day in men and women, respectively. These estimates imply that, according to an asymptotic dose-response model, mean projected maximal endogenous cortisol secretion is about 8.5-fold the unstimulated cortisol secretion rate. Reported (free) cortisol responses to maximal stress (e.g., sepsis or near exsanguination) fall in this range, namely, 6–12-fold elevations (6, 7, 10, 31). Thus, the asymptotic logistic model applied here in uninfused humans can provide seemingly reasonable predictions.

In five available clinical papers that allowed post hoc estimation of ACTH potency, the mean was 8.2 (range 5.6–13) pmol/l (3, 4, 51, 52, 69). These indirectly inferred values are slightly higher than the present analytical estimate of 5.3 ± 1.9 (SD) and 4.2 ± 1.9 pmol/l, in men and women, respectively. ACTH potency in a guinea-pig bioassay is 3.2 pmol/l (44). Model-based estimates obtained in the 48 subjects studied here closely approximated mean (24-h) ACTH concentrations in the same individuals (3.7–4.7 pmol/l). Accordingly, we postulate that ACTH concentrations fluctuate around and near in vivo ACTH potency, as estimated by the noninvasive methodology. An analogous inference has been made for luteinizing hormone-testosterone coupling in vivo (34, 38). In all, the data suggest utility of the present analytical method for investigating other agonist-driven physiological systems in vivo.

In conclusion, noninvasive analytical estimation of endogenous ACTH concentration-dependent drive of pulsatile cortisol secretion delineates sex-by-age interactions in determining ACTH efficacy, the mass of cortisol secreted per burst, and 24-h pulsatile (but not basal) cortisol secretion in healthy adults. The ensemble data introduce a potentially unifying hypothesis, in which age potentiates ACTH-adrenal coupling in women while attenuating the same in men.

Perspectives and Significance

Endocrine glands signal via putatively nonlinear dose-response functions, as predicted on theoretical grounds for ligand-receptor interactions with coupled second and third-messenger systems (17). The conventional experimental procedure for estimating such interactions is to infuse exogenous, or nullify endogenous, agonists, and measure concentration-dependent responses by the target organ. Usually the agonist is infused repeatedly on separate occasions to avoid confounding by possible response desensitization. A (logistic) dose-response function is then constructed from a collection of five or more agonist doses and matching responses. The present strategy instead is to relate endogenously generated agonist pulses to corresponding endogenous (secretory) responses via an analytically estimated dose-response function. Two advantages of this new analytical approach are 1) the dose-response function so estimated in the unifused host should capture the effects of truly physiological agonist signals, which are difficult to mimic precisely by exogenous infusions, and 2) endogenous (but not necessarily exogenous) agonist pulses occur at physiological time intervals, which should limit artefacts otherwise caused by the random relationship between exogenous pulses and the state of responsiveness or refractoriness of the target organ. An example of the former problem is infusing ACTH continuously to test adrenal responses, when, in fact, ACTH is secreted in distinct pulses possibly synchronized with adrenal innervation (22). An example of the latter is the infusion of growth hormone-releasing hormone without knowledge of pulse times of the endogenous noncompetitive antagonist, somatostatin (74), yielding inconsistent growth-hormone secretion for any given agonist dose. Accordingly, enhanced techniques should continue to be developed to quantify endogenous signal-signal interactions more accurately.

GRANTS

Studies were supported in part by the National Center for Research Resources Grant M01 RR00030 to Duke University Medical Center and P30 MH40159 (Clinical Research Center Study of Depression in Late Life); the National Institutes of Health Grants R01 DK 73148, K01 AG19164, and R21 AG 29215; and the National Sciences Foundation Interdisciplinary Grant DMS-0107680.

Acknowledgments

We thank Donna Scott for support of manuscript preparation and Ashley Bryant for data analysis and graphics.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andrew R, Phillips DI, Walker BR. Obesity and gender influence cortisol secretion and metabolism in man. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83: 1806–1809, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antonijevic IA, Murck H, Frieboes R, Holsboer F, Steiger A. On the gender differences in sleep-endocrine regulation in young normal humans. Neuroendocrinology 70: 280–287, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arvat E, Di Vito L, Lanfranco F, Maccario M, Baffoni C, Rossetto R, Aimaretti G, Camanni F, Ghigo E. Stimulatory effect of adrenocorticotropin on cortisol, aldosterone, and dehydroepiandrosterone secretion in normal humans: dose-response study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85: 3141–3146, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bahr V, Hensen J, Hader O, Bolke T, Oelkers W. Stimulation of steroid secretion by adrenocorticotropin injections and by arginine vasopressin infusions: no evidence for a direct stimulation of the human adrenal by arginine vasopressin. Acta Endocrinol 125: 348–353, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beaven D, Espiner EA, Hart DS. The suppression of cortisol secretion by steroids, and response to corticotrophin, in sheep with adrenal transplants. J Physiol (Lond) 171: 216–230, 1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beishuizen A, Thijs LG, Vermes I. Patterns of corticosteroid-binding globulin and the free cortisol index during septic shock and multitrauma. Intens Care Med 27: 1584–1591, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bendel S, Karlsson S, Pettila V, Loisa P, Varpula M, Ruokonen E. Free cortisol in sepsis and septic shock. Anesth Analg 106: 1813–1819, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Born J, Ditschuneit I, Schreiber M, Dodt C, Fehm HL. Effects of age and gender on pituitary-adrenocortical responsiveness in humans. Eur J Endocrinol 132: 705–711, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bright GM Corticosteroid-binding globulin influences kinetic parameters of plasma cortisol transport and clearance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 80: 770–775, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carlson DE, Gann DS. Effects of vasopressin antiserum on the response of adrenocorticotropin and cortisol to hemorrhage. Endocrinology 114: 317–324, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carroll BJ, Cassidy F, Naftolowitz D, Tatham NE, Wilson WH, Iranmanesh A, Liu PY, Veldhuis JD. Pathophysiology of hypercortisolism in depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand 115: 90–103, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carvalhaes-Neto N, Ramos LR, Vieira JG, Kater CE. Urinary free cortisol is similar in older and younger women. Exp Aging Res 28: 163–168, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chattopadhyay S, Veldhuis JD, Keenan DM. Probabilistic recovery of pulsatile, secretory and kinetic structure: an alternating discrete and continuous schema. Quarterly Appl Math 66: 401–421, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chong RY, Uhart M, McCaul ME, Johnson E, Wand GS. Whites have a more robust hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis response to a psychological stressor than blacks. Psychoneuroendocrinology 33: 246–254, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colby HD, Kitay JI. Interaction of estradiol and ACTH in the regulation of adrenal corticosterone production in the rat. Steroids 24: 527–536, 1974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collins A, Frankenhaeuser M. Stress responses in male and female engineering students. J Human Stress 4: 43–48, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dempsher DP, Gann DS, Phair RD. A mechanistic model of ACTH-stimulated cortisol secretion. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 246: R587–R596, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deuschle M, Weber B, Colla M, Depner M, Heuser I. Effects of major depression, aging and gender upon calculated diurnal free plasma cortisol concentrations: a re-evaluation study. Stress 2: 281–287, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dodt C, Dittmann J, Hruby J, Spath-Schwalbe E, Born J, Schuttler R, Fehm HL. Different regulation of adrenocorticotropin and cortisol secretion in young, mentally healthy elderly and patients with senile dementia of Alzheimer's type. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 72: 272–276, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duclos M, Gatta B, Corcuff JB, Rashedi M, Pehourcq F, Roger P. Fat distribution in obese women is associated with subtle alterations of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity and sensitivity to glucocorticoids. Clin Endocrinol 55: 447–454, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.El HA, Dalle M, Delost P. Role of testosterone in the sexual dimorphism of adrenal activity at puberty in the guinea pig. J Endocrinol 87: 455–461, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Engeland WC, Gann DS. Splanchnic nerve stimulation modulates steroid secretion in hypophysectomized dogs. Neuroendocrinology 50: 124–131, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Esteban NV, Loughlin T, Yergey AL, Zawadzki JK, Booth JD, Winterer JC, Loriaux DL. Daily cortisol production rate in man determined by stable isotope dilution/mass spectrometry. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 72: 39–45, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Forsman L, Lundberg U. Consistency in catecholamine and cortisol excretion in males and females. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 17: 555–562, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garren LD, Ney RL, Davis WW. Studies on the role of protein synthesis in the regulation of corticosterone production by adrenocorticotropic hormone in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 53: 1443–1450, 1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gotthardt U, Schweiger U, Fahrenberg J, Lauer CJ, Holsboer F, Heuser I. Cortisol, ACTH, and cardiovascular response to a cognitive challenge paradigm in aging and depression. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 268: R865–R873, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halbreich U, Asnis GM, Zumoff B, Nathan RS, Shindledecker R. Effect of age and sex on cortisol secretion in depressives and normals. Psychiatry Res 13: 221–229, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hatzinger M, Brand S, Perren S, von WA, von KK, and Holsboer-Trachsler E. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) activity in kindergarten children: importance of gender and associations with behavioral/emotional difficulties. J Psychiatr Res 41: 861–870, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hermus AR, Pieters GF, Smals AG, Benraad TJ, Kloppenborg PW. Plasma adrenocorticotropin, cortisol, and aldosterone responses to corticotropin-releasing factor: modulatory effect of basal cortisol levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 58: 187–191, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heuser IJ, Gotthardt U, Schweiger U, Schmider J, Lammers CH, Dettling M, Holsboer F. Age-associated changes of pituitary-adrenocortical hormone regulation in humans: importance of gender. Neurobiol Aging 15: 227–231, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ho JT, Al-Musalhi H, Chapman MJ, Quach T, Thomas PD, Bagley CJ, Lewis JG, Torpy DJ. Septic shock and sepsis: a comparison of total and free plasma cortisol levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91: 105–114, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huizenga NA, Koper JW, De Lange P, Pols HA, Stolk RP, Grobbee DE, De Jong FH, Lamberts SW. Interperson variability but intraperson stability of baseline plasma cortisol concentrations, and its relation to feedback sensitivity of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis to a low dose of dexamethasone in elderly individuals. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83: 47–54, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katz JR, Taylor NF, Perry L, Yudkin JS, Coppack SW. Increased response of cortisol and ACTH to corticotrophin releasing hormone in centrally obese men, but not in post-menopausal women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 24 Suppl 2: S138–S139, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keenan DM, Alexander SL, Irvine CHG, Clarke IJ, Canny BJ, Scott CJ, Tilbrook AJ, Turner AI, Veldhuis JD. Reconstruction of in vivo time-evolving neuroendocrine dose-response properties unveils admixed deterministic and stochastic elements. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 6740–6745, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Keenan DM, Licinio J, Veldhuis JD. A feedback-controlled ensemble model of the stress-responsive hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 4028–4033, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keenan DM, Veldhuis JD. Cortisol feedback state governs adrenocorticotropin secretory-burst shape, frequency and mass in a dual-waveform construct: time-of-day-dependent regulation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 285: R950–R961, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keenan DM, Veldhuis JD. Mathematical modeling of receptor-mediated interlinked systems. In: Encyclopedia of Hormones, San Diego, CA: Academic, 2003, p. 286–294.

- 38.Keenan DM, Veldhuis JD. Divergent gonadotropin-gonadal dose-responsive coupling in healthy young and aging men. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 286: R381–R389, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keller-Wood ME, Shinsako J, Dallman MF. Integral as well as proportional adrenal responses to ACTH. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 245: R53–R59, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kirschbaum C, Kudielka BM, Gaab J, Schommer NC, Hellhammer DH. Impact of gender, menstrual cycle phase, and oral contraceptives on the activity of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis. Psychosom Med 61: 154–162, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Klose M, Lange M, Rasmussen AK, Skakkebaek NE, Hilsted L, Haug E, Andersen M, Feldt-Rasmussen U. Factors influencing the adrenocorticotropin test: role of contemporary cortisol assays, body composition, and oral contraceptive agents. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92: 1326–1333, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kraan GP, Dullaart RP, Pratt JJ, Wolthers BG, De Bruin R. Kinetics of intravenously dosed cortisol in four men. Consequences for calculation of the plasma cortisol production rate. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 63: 139–146, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kudielka BM, Buske-Kirschbaum A, Hellhammer DH, Kirschbaum C. HPA axis responses to laboratory psychosocial stress in healthy elderly adults, younger adults, and children: impact of age and gender. Psychoneuroendocrinology 29: 83–98, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lambert A, Frost J, Garner C, Robertson WR. Cortisol production by dispersed guinea-pig adrenal cells; a specific, sensitive and reproducible response to ACTH and its fragments. J Steroid Biochem 21: 157–162, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lewis JG, Shand BI, Elder PA, Scott RS. Plasma sex hormone-binding globulin rather than corticosteroid-binding globulin is a marker of insulin resistance in obese adult males. Diabetes Obes Metab 6: 259–263, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lindheim SR, Legro RS, Bernstein L, Stanczyk FZ, Vijod MA, Presser SC, Lobo RA. Behavioral stress responses in premenopausal and postmenopausal women and the effects of estrogen. Am J Obstet Gynecol 167: 1831–1836, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu PY, Pincus SM, Keenan DM, Roelfsema F, Veldhuis JD. Analysis of bidirectional pattern synchrony of concentration-secretion pairs: implementation in the human testicular and adrenal axes. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 288: R440–R446, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luisi S, Tonetti A, Bernardi F, Casarosa E, Florio P, Monteleone P, Gemignani R, Petraglia F, Luisi M, Genazzani AR. Effect of acute corticotropin releasing factor on pituitary-adrenocortical responsiveness in elderly women and men. J Endocrinol Invest 21: 449–453, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maes M, Vandewoude M, Schotte C, Maes L, Martin M, Blockx P. Sex-linked differences in cortisol, ACTH and prolactin responses to 5-hydroxy-tryptophan in healthy controls and minor and major depressed patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 80: 584–590, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Manco M, Fernandez-Real JM, Valera-Mora ME, Dechaud H, Nanni G, Tondolo V, Calvani M, Castagneto M, Pugeat M, Mingrone G. Massive weight loss decreases corticosteroid-binding globulin levels and increases free cortisol in healthy obese patients: an adaptive phenomenon? Diabetes Care 30: 1494–1500, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oelkers W, Boelke T, Bahr V. Dose-response relationships between plasma adrenocorticotropin (ACTH), cortisol, aldosterone, and 18-hydroxycorticosterone after injection of ACTH-(1–39) or human corticotropin-releasing hormone in man. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 66: 181–186, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Orth DN, Jackson RV, DeCherney GS, Debold CR, Alexander AN, Island DP, Rivier J, Rivier C, Spiess J, Vale W. Effect of synthetic ovine corticotropin-releasing factor. Dose response of plasma adrenocorticotropin and cortisol. J Clin Invest 71: 587–595, 1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Patel RS, Shaw SR, Macintyre H, McGarry GW, Wallace AM. Production of gender-specific morning salivary cortisol reference intervals using internationally accepted procedures. Clin Chem Lab Med 42: 1424–1429, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Petrie EC, Wilkinson CW, Murray S, Jensen C, Peskind ER, Raskind MA. Effects of Alzheimer's disease and gender on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis response to lumbar puncture stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology 24: 385–395, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Purnell JQ, Brandon DD, Isabelle LM, Loriaux DL, Samuels MH. Association of 24-hour cortisol production rates, cortisol-binding globulin, and plasma-free cortisol levels with body composition, leptin levels, and aging in adult men and women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89: 281–287, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Purnell JQ, Kahn SE, Samuels MH, Brandon D, Loriaux DL, Brunzell JD. Enhanced cortisol production rates, free cortisol, and 11 Beta HSD-1 expression correlate with visceral fat and insulin resistance in men: effect of weight loss. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 296: E351–E357, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Raff H Immulite vs Scantibodies IRMA plasma ACTH assay. Clin Chem 54: 1409–1410, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Raven PW, Taylor NF. Sex differences in the human metabolism of cortisol. Endocr Res 22: 751–755, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roca CA, Schmidt PJ, Deuster PA, Danaceau MA, Altemus M, Putnam K, Chrousos GP, Nieman LK, Rubinow DR. Sex-related differences in stimulated hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis during induced gonadal suppression. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90: 4224–4231, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ruhmann-Wennhold A, Nelson DH. Testosterone inhibition of estradiol- induced stimulation of adrenal 11-beta- and 18-hydroxylation. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 133: 493–496, 1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schmidt PJ, Raju J, Danaceau M, Murphy DL, Berlin RE. The effects of gender and gonadal steroids on the neuroendocrine and temperature response to m-chlorophenylpiperazine in leuprolide-induced hypogonadism in women and men. Neuropsychopharmacology 27: 800–812, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Seeman TE, Robbins RJ. Aging and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal response to challenge in humans. Endocr Rev 15: 233–260, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Seeman TE, Singer B, Wilkinson CW, McEwen B. Gender differences in age-related changes in HPA axis reactivity. Psychoneuroendocrinology 26: 225–240, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Silva C, Ines LS, Nour D, Straub RH, and da Silva J. A. Differential male and female adrenal cortical steroid hormone and cortisol responses to interleukin-6 in humans. Ann NY Acad Sci 966: 68–72, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stimson RH, Johnstone AM, Homer NZ, Wake DJ, Morton NM, Andrew R, Lobley GE, Walker BR. Dietary macronutrient content alters cortisol metabolism independently of bodyweight changes in obese men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92: 4480–4484, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stolk RP, Lamberts SW, De Jong FH, Pols HA, Grobbee DE. Gender differences in the associations between cortisol and insulin in healthy subjects. J Endocrinol 149: 313–318, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Strain GW, Zumoff B, Kream J, Strain JJ, Levin J, Fukushima D. Sex difference in the influence of obesity on the 24 hr mean plasma concentration of cortisol. Metabolism 31: 209–212, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Therrien F, Drapeau V, Lalonde J, Lupien SJ, Beaulieu S, Tremblay A, Richard D. Awakening cortisol response in lean, obese, and reduced obese individuals: effect of gender and fat distribution. Obesity 15: 377–385, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thomas MA, Rebar RW, LaBarbera AR, Pennington EJ, Liu JH. Dose-response effects of exogenous pulsatile human corticotropin-releasing hormone on adrenocorticotropin, cortisol, and gonadotropin concentrations in agonadal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 72: 1249–1254, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Travison TG, O'Donnell AB, Araujo AB, Matsumoto AM, McKinlay JB. Cortisol levels and measures of body composition in middle-aged and older men. Clin Endocrinol 67: 71–77, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Uhart M, Chong RY, Oswald L, Lin PI, Wand GS. Gender differences in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis reactivity. Psychoneuroendocrinology 31: 642–652, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Van Cauter E, Leproult R, Kupfer DJ. Effects of gender and age on the levels and circadian rhythmicity of plasma cortisol. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 81: 2468–2473, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Veldhuis JD, Keenan DM, Roelfsema F, Iranmanesh A. Aging-related adaptations in the corticotropic axis: modulation by gender. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am 993–1014, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 74.Veldhuis JD, Roemmich JN, Richmond EJ, Bowers CY. Somatotropic and gonadotropic axes linkages in infancy, childhood, and the puberty-adult transition. Endocr Rev 27: 101–140, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Viau V, Meaney MJ. Variations in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal response to stress during the estrous cycle in the rat. Endocrinology 129: 2503–2511, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vicennati V, Ceroni L, Genghini S, Patton L, Pagotto U, Pasquali R. Sex difference in the relationship between the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and sex hormones in obesity. Obesity 14: 235–243, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vierhapper H, Nowotny P, Waldhausl W. Production rates of cortisol in obesity. Obes Res 12: 1421–1425, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vierhapper H, Nowotny P, Waldhausl W. Sex-specific differences in cortisol production rates in humans. Metabolism 47: 974–976, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wilkinson CW, Raff H. Comparative evaluation of a new immunoradiometric assay for corticotropin. Clin Chem Lab Med 44: 669–671, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhao ZY, Lu FH, Xie Y, Fu YR, Bogdan A, Touitou Y. Cortisol secretion in the elderly. Influence of age, sex and cardiovascular disease in a Chinese population. Steroids 68: 551–555, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zietz B, Hrach S, Scholmerich J, Straub RH. Differential age-related changes of hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis hormones in healthy women and men–role of interleukin 6. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 109: 93–101, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]