Abstract

The enzyme ADP-ribosyl (ADPR) cyclase plays a significant role in mediating increases in renal afferent arteriolar cytosolic calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) in vitro and renal vasoconstriction in vivo. ADPR cyclase produces cyclic ADP ribose, a second messenger that contributes importantly to ryanodine receptor-mediated Ca2+ mobilization in renal vascular responses to several vasoconstrictors. Recent studies in nonrenal vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) have shown that nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP), another second messenger generated by ADPR cyclase, may contribute to Ca2+ signaling. We tested the hypothesis that a Ca2+ signaling pathway involving NAADP receptors participates in afferent arteriolar [Ca2+]i responses to the G protein-coupled receptor agonists endothelin-1 (ET-1) and norepinephrine (NE). To test this, we isolated rat renal afferent arterioles and measured [Ca2+]I using fura-2 fluorescence. We compared peak [Ca2+]i increases stimulated by ET-1 and NE in the presence and absence of inhibitors of acidic organelle-dependent Ca2+ signaling and NAADP receptors. Vacuolar H+-ATPase inhibitors bafilomycin A1 and concanamycin A, disruptors of pH and Ca2+ stores of lysosomes and other acidic organelles, individually antagonized [Ca2+]i responses to ET-1 and NE by 40–50% (P < 0.05). The recently discovered NAADP receptor inhibitor Ned-19 attenuated [Ca2+]i responses to ET-1 or NE by 60–70% (P < 0.05). We conclude that NAADP receptors contribute to both ET-1- and NE-induced [Ca2+]i responses in afferent arterioles, an effect likely dependent on acidic vesicle, possibly involving lysosome, signaling in VSMC in the renal microcirculation.

Keywords: adenosine 5′-diphosphate-ribosyl cyclase, calcium mobilization, vascular smooth muscle cells, renal circulation

renal blood flow (RBF) and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) are regulated by afferent arteriolar resistance as dictated by the balance between vasodilator and vasoconstrictor factors. In turn, the renal microcirculation affects Na+ and water excretion, extracellular fluid volume, and systemic arterial pressure (AP). (1). Cytosolic Ca2+ concentration [Ca2+]i in endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) is central to the regulation of the overall contractile state of resistance arterioles. Many local and circulating vasoactive agents exert their effects by influencing [Ca2+]i in either cell type. In endothelial cells, [Ca2+]i activates endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and production of the vasodilator NO as well as PLA2 and arachidonic acid metabolites. In VSMC, [Ca2+]i activates myosin light chain kinase, leading to phosphorylation of myosin fibers and vessel contraction. Elucidating mechanisms affecting Ca2+ signaling in glomerular arterioles is therefore essential to a comprehensive understanding of basic function of the renal microcirculation in health and disease.

Afferent arteriolar [Ca2+]i is generally kept low (∼100 nM) in an environment of high extracellular [Ca2+] (∼1 mM). High [Ca2+] is maintained in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), mitochondria, and lysosomal and endo/exocytic vesicles by the sarco(endo)plasmic reticular Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA), mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter, and vacuolar H+-ATPase, respectively (1, 33). [Ca2+]i is regulated by a combination of Ca2+ entry through channels in the plasma membrane and Ca2+ mobilization or release from SR stores with apparent agonist/stimulus specificity. Ca2+ mobilization from other intercellular stores is less well characterized.

Recent in vitro evidence from afferent arterioles as well as coronary and pulmonary arterial VSMC indicates that the enzyme ADP-ribosyl cyclases (ADPR cyclases) regulate ryanodine receptor (RyR)-mediated SR Ca2+ release to cause global increases in [Ca2+]i and contraction (13, 22, 44). Importantly, animal studies indicate that this novel second messenger system plays a major role in increasing renal vascular resistance to the vasoconstrictors angiotensin II (ANG II), endothelin-1 (ET-1), and norepinephrine (NE) (36, 37). ADPR cyclases in the sea hare (Aplysia californica) and mammals produce two second messengers: cyclic ADP ribose (cADPR) and nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP) (3). cADPR is produced by plasma membrane-bound ADPR cyclase at relatively neutral physiological pH. NAADP, on the other hand, is primarily generated at very low pH such as that found in lysosomal and endo/exocytic vesicles (16, 41). Whereas NAADP may be generated by nonenzymatic means, the ADPR cyclase from the A. californica and the mammalian ADPR cyclase CD38 are the only enzymes currently known to produce NAADP (19, 25). Recently, NAADP has been shown to elicit Ca2+ release from reserve granules in sea urchin eggs (5) and acidic organelles, possibly lysosomes, in mammalian cells such as pancreatic acinar cells and pulmonary arterial VSMC (22, 23, 42). It is currently thought that ADPR cyclases produce NAADP in acidic organelles, with NAADP binding to a receptor/channel, perhaps a transient receptor potential-mucolipid 1 (TRP-ML1) channel (45), in the organelle membrane to allow exit of Ca2+ into the cytosol in coronary and pulmonary VSMC (22). The identity of which particular acidic organelle synthesizes NAADP is currently uncertain and has been hypothesized to be late endosome, lysosome, and/or exocytic vesicles (22, 23, 6). Although such localized Ca2+ release is not normally sufficient to produce a widespread global Ca2+ response leading, for example, to vessel contraction, acidic organelles bearing NAADP-sensitive receptor/channels appear to lie in close proximity to the SR to form a “trigger zone” with nearby RyR (apparently subtype 3, RyR3) on the SR of pulmonary VSMC (23). A small efflux of Ca2+ appears to activate RyR3 and causes Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release from the SR. NAADP increases Ca2+ release from mesangial cell microsomes, and NAADP increases [Ca2+]i when administered in microbubbles to coronary VSMC or given by intracellular dialysis to pulmonary arterial VSMC (22, 43, 46). Physiologically, NAADP production may be stimulated downstream of G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling, since Ca2+ responses to the GPCR agonist ET-1 appear to be attenuated in the absence of functional vesicles (22, 46). In testicular peritubular smooth muscle cells, ET-1-induced contraction depends in part on caveolae and NAADP (17). No study to date has investigated whether endogenous NAADP participates in GPCR stimulation of [Ca2+]i in a resistance arteriole in general or a renal afferent arteriole in particular.

In the current study, we tested the hypothesis that native NAADP contributes to the increase in [Ca2+]i produced in response to GPCR stimulation by ET-1 and NE in afferent arterioles isolated from the kidneys of healthy rats. We measured [Ca2+]i responses to each agonist in the presence and absence of the acidic organelle Ca2+ disrupters bafilomycin A1 and concanamycin A and the selective NAADP receptor antagonist Ned-19. We have demonstrated, for the first time, a dependence of ET-1 and NE effects on NAADP signaling in [Ca2+]i responses in individual renal afferent arterioles.

METHODS

Sprague-Dawley rats were fed standard laboratory chow and given tap water ad libitum and were kept on a 12:12-h light-dark cycle. Animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Isolation of afferent arterioles.

Afferent arterioles were harvested from a total of 62 rats (3.5–6 wk of age) obtained from our in-house breeding facility. Our standard magnet/sieving preparation was used to isolate resistance arterioles (13, 14, 15). Briefly, animals were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (55 mg/kg). Through a midline incision, the aorta was clamped above the renal arteries and cannulated at the bifurcation of the common iliac arteries using a 23-gauge butterfly needle. Kidneys were perfused with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS: 137 mM NaCl, 4.1 mM KCl, 0.66 mM KH2PO4, 3.4 mM Na2HPO4, 2.5 mM NaHCO3, 1.0 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM glucose, pH 7.4) followed by magnetized microspheres (Spherotech, Libertyville, IL). Kidneys were removed, decapsulated, homogenized, and filtered through a number 120 sieve to remove tubules and glomeruli. Tissue was then treated with collagenase (type IV, 5–10 μg/ml; Worthington, Lakewood, NJ) in a 50:50 mixture of Hanks' buffered salt solution (HBSS) and PBS (pH 7.38) containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) at 37°C for 18 min. Arterioles were then loaded with fura-2 AM (2 μM) in HBSS-PBS with 0.1% BSA for 55 min in the dark. Vessels were placed in a solution of HBSS-PBS and 1.1 mM CaCl2 (pH 7.35) just before the start of the experiment.

Afferent arterioles were identified by diameter (<20 μm) and morphology (8–14). Arterioles were attached to an interlobular artery. A single afferent arteriole was centered in the optical field so that only afferent arteriolar [Ca2+]i was measured. Endothelial cells were present but had been shown to be unresponsive in this preparation to stimuli added to the external bathing solution (14). As a result, [Ca2+]i measurements were due only to changes in VSMC [Ca2+]i. Arterioles were placed on slides pretreated with Cell Tak (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), placed in 20 μl of PBS solution containing 1.1 mM CaCl2, and excited at alternating wavelengths of 340 and 380 nm by using a Delta-Scan equipped with dual monochronometers and a chopper [Photon Technology International (PTI)] (13, 14, 15). Signals were passed through an emission barrier filter (510-nm band pass), and fluorescence was detected by a photomultiplier tube. Signals were processed using an IBM-compatible Pentium computer and Felix software (PTI). [Ca2+]i calibration was based on a 340- to 380-nm signal ratio and known [Ca2+]i concentrations as previously described (8, 13, 14). [Ca2+]i was calculated using the equation [Ca2+]i = [(R − Rmin)/Rmax − R] × (Sf/Sb) × Kd, where R is the ratio of the 340- to 380-nm signal, Rmax is the ratio in the presence of Ca2+ saturation, Rmin is the ratio in the presence of Ca2+-free buffer, and Sf/Sb is the 340-to 380-nm ratio in Ca2+-free buffer compared with a Ca2+-replete solution (8, 21). Background was subtracted for each vessel. After a control baseline reading of at least 30 s, ET-1 or NE was added during continuous recording. In other arterioles, an inhibitor was added to the bath 1–2 min before stimulation with either ET-1 or NE. A vessel that did not respond to 40 mM KCl at the end of either the control or experimental period was discarded. KCl-induced changes in [Ca2+]i in the presence of inhibitors served as a positive control to ensure maintenance of responsiveness at the end of an experiment. Peak responses were defined as the highest signal occurring within the first 30 s after agonist addition. Plateau responses were taken as the [Ca2+]i recorded at 90 s after agonist addition.

Reagents.

Concentrations of agonists and inhibitors used were based on previously published observations and on occasion were altered slightly in preliminary experiments to obtain a maximum effect. They were as follows: ET-1, 10−7 M; NE, 10−5 M; bafilomycin A1, 10−7 M; concanamycin A, 10−6 M; and Ned-19, 10−5 M (14, 22, 26, 30, 32). We purchased ET-1 from American Peptide (Vista, CA) and NE (Levophed) from Abbott Labs (Abbott Park, IL). Bafilomycin A1 was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), and concanamycin A was obtained from Wako Chemical (Richmond, VA). Ned-19 is a recently discovered novel specific NAADP receptor antagonist (26). Ned-19 was identified in a virtual library screen and has been shown to effectively inhibit [Ca2+]i responses to NAADP but not inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) or cADPR. Antagonistic actions of Ned-19 on NAADP receptors are evident in its ability to displace radiolabeled NAADP binding.

Data analysis and statistics.

Data were analyzed using Felix software (Photon Technology International). Statistical analyses were performed using a Student's t-test with SigmaStat software.

RESULTS

NAADP receptors are thought to rely on Ca2+ stores in acidic compartments to influence [Ca2+]i. To test the importance of these Ca2+ stores in afferent arteriolar [Ca2+]i responses to ET-1 and NE, we inhibited the vacuolar H+-ATPase using pharmacological agents. The vacuolar H+-ATPase maintains the low pH of acidic organelles by actively pumping in H+ ions from the cytoplasm, an influx of H+ that provides a gradient for Ca2+ entry via a Ca2+/H+ exchanger located in the organelle membrane (27). As a result, the employed vacuolar H+-ATPase inhibitors bafilomycin A1 and concanamycin A attenuate Ca2+ signaling generated by acidic compartments by deacidification of vesicles and disruption of the H+ gradient needed for Ca2+ accumulation.

Afferent arteriolar [Ca2+]i responses to ET-1 depend on Ca2+ stores in acidic vesicles.

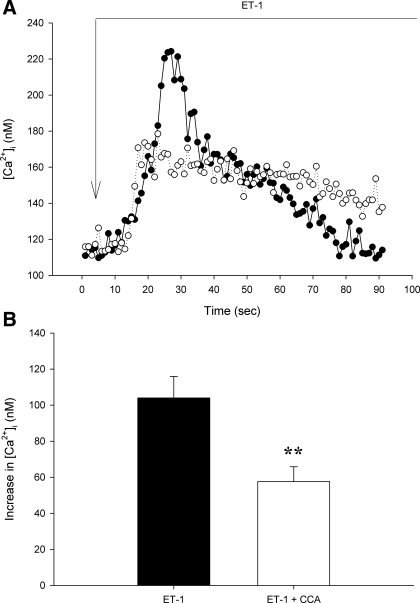

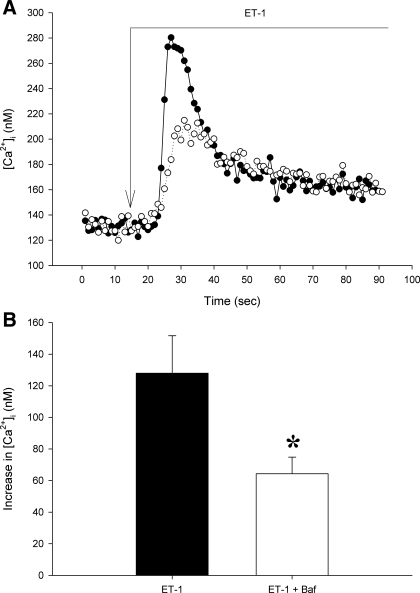

In untreated control arterioles, ET-1 produced an immediate 104 ± 12 nM increase in [Ca2+]i (Fig. 1). Pretreatment with concanamycin A for 1–2 min did not alter baseline [Ca2+]i (135 ± 10 vs. 117 ± 21 nM, P > 0.4) but attenuated the peak response to ET-1 to an increase of 58 ± 8 nM (P < 0.02 vs. controls). In contrast, the sustained plateau phase of the ET-1 [Ca2+]i response was not altered by concanamycin A (30 ± 4 vs. 25 ± 4 nM, P > 0.4). Similarly, pretreatment with bafilomycin A1 did not affect baseline [Ca2+]i (209 ± 24 vs. 186 ± 25 nM, P > 0.5). The peak increase in [Ca2+]i elicited by ET-1 was reduced by bafilomycin A1 (128 ± 24 to 64 ± 10 nM, P < 0.05), whereas the plateau [Ca2+]i following ET-1 stimulation was unaffected (52 ± 27 vs. 51 ± 18 nM, P > 0.9, Fig. 2). Collectively, these data strongly suggest the involvement of lysosome-like acidic vesicles and mobilization of their Ca2+ stores in immediate peak [Ca2+]i response to ET-1 in afferent arterioles but not in the basal resting [Ca2+]i or the sustained plateau ET-1-induced [Ca2+]i change.

Fig. 1.

Responses of afferent arteriolar cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) to endothelin-1 (ET-1) in the absence and presence of concanamycin A (CCA; 10−6 M) inhibition of the vacuolar H+-ATPase. A: representative tracings of ET-1 [Ca2+]i responses in the presence (○) or absence (•) of CCAA. Long arrow indicates addition of ET-1. B. group average of the maximum increase in [Ca2+]i in response to ET-1 with or without CCA. Values are means ± SE; n ≥ 9. **P < 0.02.

Fig. 2.

Increases in afferent arteriolar [Ca2+]i caused by ET-1 under control conditions and during inhibition of the vacuolar H+-ATPase with bafilomycin A1 (Baf; 10−7 M). A: representative tracings of [Ca2+]i after stimulation by ET-1 in an untreated control vessel (solid line, •) or in a vessel pretreated with Baf (dotted line, ○). Long arrow indicates addition of ET-1. B: mean peak change in afferent arteriolar [Ca2+]i after ET-1 in the presence or absence of Baf. Values are means ± SE; n ≥ 5. *P < 0.05.

NE-induced changes in afferent arteriolar [Ca2+]i are mediated by Ca2+ release from acidic stores.

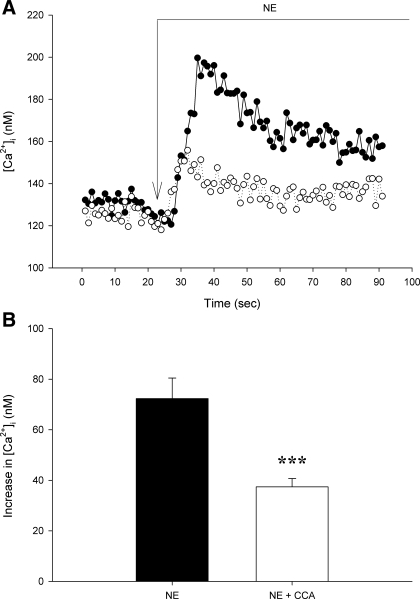

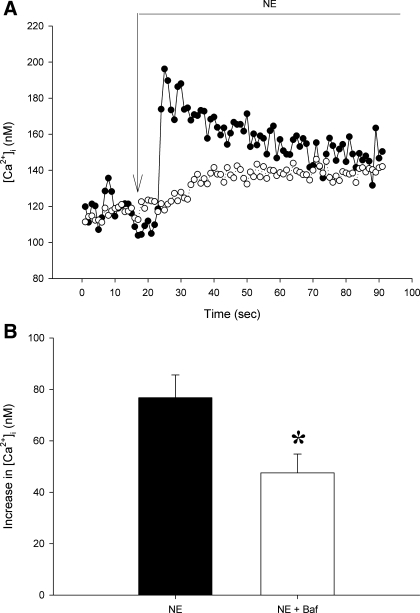

Under control conditions, NE increased [Ca2+]i by 72 ± 8 nM (Fig. 3). Neither bafilomycin A1 nor concanamycin A affected baseline [Ca2+]i.( 101 ± 10 and 123 ± 11 vs. 115 ± 10 and 151 ± 17 nM in respective untreated control groups, P > 0.1 for both, Figs. 3 and 4). Both vacuolar H+-ATPase inhibitors attenuated peak afferent arteriolar [Ca2+]i responses to NE. Concanamycin A decreased this peak response to 37 ± 3 nM [Ca2+]i (P < 0.005, Fig. 4). Concanamycin A reduced the plateau [Ca2+]i response to NE from 32 ± 5 to 18 ± 3 nM (P < 0.05). Bafilomycin A1 attenuated the immediate peak NE response (77 ± 9 to 47 ± 7 nM, P < 0.05) without affecting the [Ca2+]i increase during the plateau phase (33 ± 4 vs. 28 ± 5 nM, P > 0.5). Together, these data indicate that Ca2+ release from acidic compartments contributes to rapid global increases in [Ca2+]i when afferent arteriolar adrenoceptors are stimulated by NE.

Fig. 3.

[Ca2+]i responses to norepinephrine (NE) without and with CCA (10−6 M) inhibition of vacuolar H+-ATPase in 2 afferent arterioles. A: typical [Ca2+]i increases produced by NE in the presence (○) or absence (•) of CCA. Long arrow indicates time of NE addition. B: mean initial peak [Ca2+]i response to NE under control conditions or after pretreatment with CCA. Values are means ± SE; n ≥ 8. ***P < 0.005.

Fig. 4.

NE-induced changes in [Ca2+]i without and with vacuolar H+-ATPase inhibition by Baf (10−7 M). A: original recordings of [Ca2+]i in isolated afferent arterioles in response to NE alone (•) or NE + Baf (○). Long arrow indicates NE addition. B: average maximum increase in afferent arteriolar [Ca2+]i in the presence or absence of Baf. Values are means ± SE; n ≥ 11. *P < 0.05.

NAADP receptors contribute to [Ca2+]i increases downstream of both ET-1 and NE receptors in afferent arterioles.

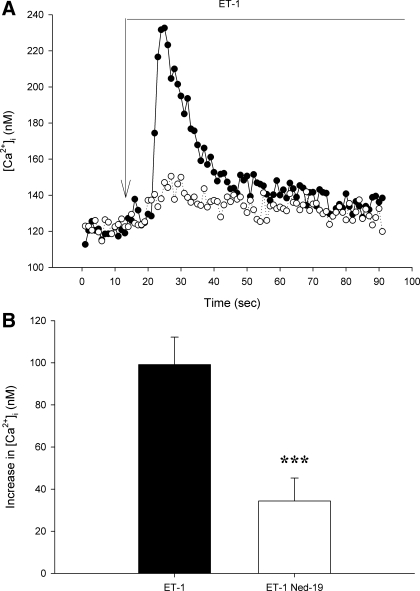

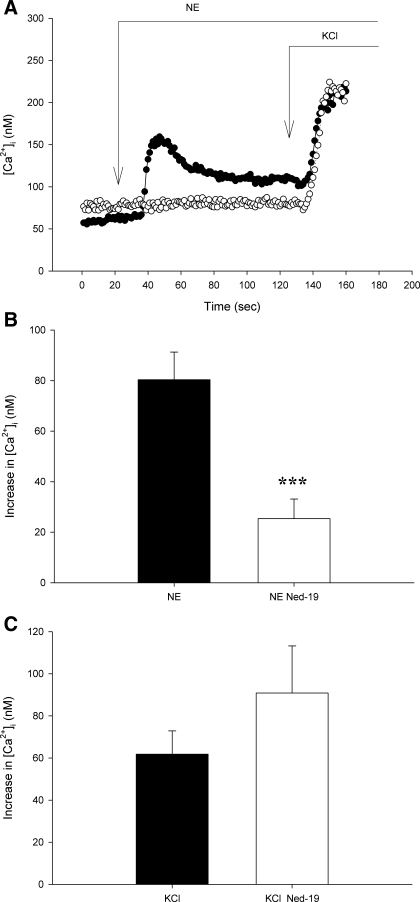

To determine whether NAADP receptors specifically participate in ET-1 induced changes in [Ca2+]i, we used the selective NAADP receptor antagonist Ned-19. In isolated afferent arterioles, pretreatment with Ned-19 did not influence baseline [Ca2+]i (84 ± 10 vs. 86 ± 11 and 95 ± 5 vs. 79 ± 8 nM, P > 0.1 for ET-1 and NE groups). On the other hand, Ned-19 inhibited initial peak [Ca2+]i responses to both ET-1 and NE (Figs. 5 and 6, respectively). ET-1 and NE initially produced 99 ± 13 and 80 ± 11 nM increases in [Ca2+]i, respectively. During Ned-19 inhibition of NAADP receptors, the responses were attenuated. In the presence of Ned-19, ET-1 and NE increased [Ca2+]i by 34 ± 11 and 25 ± 8 nM (P < 0.05 for both). The sustained plateau response to ET-1 was not altered by Ned-19 (33 ± 4 vs. 28 ± 8 nM, P > 0.6), as was the case for the plateau phase during NE stimulation (33 ± 7 vs. 14 ± 5 nM Ca2+, 0.1 > P > 0.05). The increase in [Ca2+]i produced by high KCl given after NE was unaltered by Ned-19 (P > 0.2, Fig. 6), suggesting an action of Ca2+ mobilization rather than entry. Because Ned-19 attenuated the immediate peak [Ca2+]i response to both ET-1 and NE, we conclude that NAADP receptors and related Ca2+ release from acidic compartments contribute importantly to the most rapid afferent arteriolar [Ca2+]i responses to these two GPCR agonists.

Fig. 5.

Attenuated afferent arteriolar responses to ET-1 during antagonism of nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP) receptors with Ned-19 (10−5 M). A: representative recordings of [Ca2+]i changes produced by ET-1 in the presence (○) or absence (•) of Ned-19. B: mean maximum increase in afferent arteriolar [Ca2+]i in the presence or absence of Ned-19. Values are means ± SE; n ≥ 6. ***P < 0.005.

Fig. 6.

Effect of NAADP receptor inhibition with Ned-19 (10−5 M) on NE-induced changes in afferent arteriolar [Ca2+]i. A: individual tracings of NE-induced [Ca2+]i responses in afferent arterioles treated with vehicle (•) or Ned-19 (○) before and after KCl (40 mM) given after NE. B: average peak [Ca2+]i responses to NE in the presence or absence of Ned-19. C: average peak [Ca2+]i responses to KCl given after NE in the presence or absence of Ned-19. Values are means ± SE; n ≥ 7. ***P < 0.005.

DISCUSSION

Our major novel observation is the contribution of the NAADP signaling pathway to GPCR-induced [Ca2+]i responses in a true resistance arteriole <20 μm in diameter, and the afferent arteriole of the renal microcirculation in particular. [Ca2+]i increases produced by the GPCR agonists ET-1 and NE are attenuated during pharmacological inhibition of acidic organelle Ca2+ signaling and of NAADP receptor function. Using bafilomycin A1 and concanamycin A, two vacuolar H+-ATPase inhibitors, we have shown dependence on acidic vesicles, perhaps including lysosomes, for Ca2+ signaling in afferent arterioles stimulated by ET-1. Two prior studies have demonstrated a role of acidic vesicles to ET-1 Ca2+ signaling in VSMC of large diameter arteries, specifically coronary (46) and pulmonary (22) arteries. To our knowledge, our results are the first to demonstrate the importance of acidic organelles in ET-1-elicited Ca2+ signaling in a resistance arteriole freshly isolated from the microcirculation. Using the recently discovered specific NAADP receptor antagonist Ned-19, we have shown that NAADP receptors are involved in ET-1-induced afferent arteriolar [Ca2+]i responses. Our study is original in using this inhibitor in a blood vessel and establishing involvement of NAADP receptors in ET-1 signaling in any cell type. We also observed that vacuolar H+-ATPase disrupters attenuate [Ca2+]i responses to NE in isolated afferent arterioles. We found similar degrees of inhibition with either bafilomycin A1 or concanamycin A. Another new finding is that NAADP receptors are activated downstream of catecholamine adrenoceptors. Ned-19, the best available NAADP receptor antagonist, attenuates NE-induced [Ca2+]i responses in our isolated afferent arterioles. Together, our results are novel in showing activation of NAADP receptors and related Ca2+ stimulation downstream of GPCR agonists in isolated afferent arterioles when VSMC are activation with either ET-1 or NE. An earlier study reported that bafilomycin A1 did not alter NE-induced increase in [Ca2+]i of cultured rat pinealocytes (40), suggesting a possible difference in signaling mechanisms between cell types.

We chose to study the effects of NAADP pathway inhibitors on Ca2+ signaling initiated by NE and ET-1 activation of distinct GPCR classes. In all VSMC, alterations in [Ca2+]i are a primary determinant of vascular tone. Arterial pressure and organ blood flow are therefore largely controlled by the actions of various regulators of VSMC [Ca2+]I, including GPCR agonists (1). In afferent arterioles, renal nerves release NE to act on VSMC and produce vasoconstriction evidenced as decreases in RBF and GFR (18, 31). Locally, endothelial cells release ET-1 to act on endothelial cells in an autocrine manner and on VSMC in a paracrine fashion (34). Thus our results strongly suggest participation of acidic Ca2+ stores and NAADP in the neural and autocrine/paracrine regulation of RBF and GFR, advancing an area ripe for future investigation.

We used three pharmacological inhibitors of various steps in the NAADP signaling pathway. Bafilomycin A1 and concanamycin A should have two effects: an increase in pH that leads to decreased production of NAADP by ADPR cyclases located in the membranes of acidic organelles (5, 24) and a reduced H+ gradient favoring less H+ efflux and Ca2+ entry into acidic vesicles. Thus acidic Ca2+ stores are diminished and release through NAADP receptors is attenuated (22), resulting in attenuated NAADP signaling. Very recently, Churchill and colleagues (26) discovered a novel selective inhibitor of the NAADP receptor, Ned-19, that blocks the effects of NAADP on Ca2+ signaling in sea urchin egg homogenates and in mouse pancreatic β-cells. This antagonist provided us with a more specific tool to examine NAADP signaling, since Ned-19 is known to strongly attenuate [Ca2+]i responses to NAADP in sea urchin eggs but have no effect on responses to IP3 or cADPR. Our results indicate that NAADP production in acidic vesicles is activated downstream of ET-1 and NE cell surface receptors to produce increases in [Ca2+]i in isolated afferent arterioles.

It is important to note that the inhibitors used in our study, concanamycin A and bafilomycin A1, inhibit H+ and, subsequently, Ca2+ uptake into all acidic organelles. Thus it is not clear which particular organelle is involved in mediating afferent arteriolar NE and ET-1 Ca2+ responses. Likewise, other studies on coronary and pulmonary VSMC also have used general vacuolar ATPase inhibitors or lysotracker, a fluorescent dye that labels all acidic organelles (22, 23, 46). Recent evidence obtained on sea urchin eggs suggests that the site of NAADP synthesis may be exocytic vesicles (6). Future studies are required to determine the precise identity of this compartment in VSMC.

Noteworthy is the preferential inhibition of the antagonists on the initial peak vs. sustained plateau Ca2+ responses. Peak responses to both NE and ET-1 were blunted significantly by all inhibitors tested. However, the ET-1-induced Ca2+ plateau was not altered by any inhibitor. Apparent effects on plateaus during NE stimulation were more variable, on the other hand, affected by some inhibitors but not others. Application of a Ca2+ free external solution to isolated rat interlobular arteries and afferent arterioles abolishes the plateau [Ca2+]i response to NE but not the peak response (8, 32), suggesting a role of Ca2+ release in the immediate response and a predominance of Ca2+ entry through plasma membrane channels in maintaining the plateau response. Our results suggest that Ned-19 inhibits Ca2+ mobilization from internal stores to a greater extent than Ca2+ entry from extracellular sources.

Previous studies have shown blunting of ET-1 [Ca2+]i responses in afferent arterioles by using inhibitors of Ca2+ entry channels (28) and Ca2+ mobilization (14). NE responses also are substantially attenuated by a large percentage in the absence of Ca2+ entry and IP3 receptor function (32). We find >50% inhibition of NE- and ET-1-induced increases in [Ca2+]i with inhibitors of the vacuolar H+-ATPase and NAADP receptors in the present study. If one assumes that all entry and mobilization pathways are separate and noninteracting, then the overall contribution of currently known Ca2+ channels to afferent arteriolar NE- and ET-1-induced [Ca2+]i responses greatly exceeds 100%. This conundrum suggests a complex overlap of pathways with interactions. RyR also can amplify Ca2+ responses in arteriolar VSMC and contraction of the renal vasculature initiated by Ca2+ entry through voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ channels (15, 36). RyR appear to be localized adjacent to NAADP receptors in membranes of acidic organelles (22) and also are reported to reside near large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BKCa) channels in the plasma membrane of VSMC (38). The two products of ADPR cyclase may enhance the actions of one another as well. Although NAADP works in the manner described above, cADPR enhances RyR open probability, possibly by removing inhibitory FK506 binding proteins (35). It is possible that, in this way, cADPR can amplify effects of NAADP to produce a larger [Ca2+]i response such that the combined effect is greater than activation of a single second messenger. It is currently unknown whether cADPR and NAADP are produced by two distinct populations of ADPR cyclases or whether cADPR is produced at the plasma membrane followed by internalization of the same enzyme and subsequent production of NAADP. Our understanding of precise interactions between these sources of ADPR cyclase metabolites and their relative roles in regulating [Ca2+]i awaits future investigation.

We found that resting baseline [Ca2+]i is not altered during the initial 1–2 min of inhibition of vacuolar H+-ATPase and/or NAADP receptors, suggesting that NAADP is likely not produced in sufficient amounts under our basal ex vivo conditions. In marked contrast, acute GPCR activation by ET-1 or NE stimulates ADPR cyclase production of NAADP in a manner similar to production of cyclic ADP-ribose, both of which enhance RyR-mediated Ca2+ release. The TRP-ML1 channel is reported to function as a NAADP receptor in coronary arterial myocytes (45). Future experiments should help determine whether NAADP is produced by some or all GPCR acting to increase [Ca2+]i or Ca2+ signaling elicited by other vasoconstrictor stimuli, e.g., pressure-induced myogenic response.

In summary, our novel findings provide insight into mechanisms mediating Ca2+ signal transduction in a small-diameter resistance arteriole in the renal microcirculation. Our new evidence demonstrates that NAADP receptors contribute to GPCR-induced [Ca2+]i changes in isolated rat afferent arterioles. This holds for GPCR acutely stimulated by either ET-1 or NE. Immediate peak responses to both agonists are markedly attenuated during pharmacological inhibition of the vacuolar H+-ATPase and NAADP receptors. Our observations indicate major involvement of this NAADP second messenger pathway in ET-1- and NE- induced Ca2+ signaling in renal arteriolar VSMC. This work advances our understanding of Ca2+ signal transduction in a resistance arteriole such as the afferent arteriole and provides a rationale and background for future experiments investigating the importance of this ADPR cyclase/NAADP pathway in the regulation of renal hemodynamics and blood flow in other organs in health and disease.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-02334 (to W. J. Arendshorst) and Biological Sciences Research Council Grant BB/D012694/1 (to G. C. Churchill).

REFERENCES

- 1.Arendshorst WJ, Navar LG. Renal circulation in glomerular hemodynamics. In: Diseases of the Kidney and Urinary Tract, edited by Schrier RW. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins, 2007, p. 54–95.

- 2.Arendshorst WJ, Thai TL. Regulation of the renal circulation by ryanodine receptors and calcium-induced calcium release. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 18: 40–49, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bai N, Lee HC, Laher I. Emerging role of cyclic ADP-ribose (cADPR) in smooth muscle. Pharmacol Ther 105: 189–207, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowman EJ, Siebers A, Altendorf K. Bafilomycins: a class of inhibitors of membrane ATPases from microorganisms, animal cells, and plant cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 85: 7972–7976, 1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Churchill GC, Okada Y, Thomas JM, Genazzani AA, Patel S, Galione A. NAADP mobilizes Ca2+ from reserve granules, lysosome-related organelles, in sea urchin eggs. Cell 111: 703–708, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis LC, Morgan AJ, Ruas M, Wong JL, Graeff RM, Poustka AJ, Lee HC, Wessel GM, Parrington J, Galione A. Ca2+ signaling occurs via second messenger release from intraorganelle synthesis sites. Curr Biol 18: 1612–1618, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drose S, Altendorf K. Bafilomycins and concanamycins as inhibitors of V-ATPases and P-ATPases. J Exp Biol 200: 1–8, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Facemire CS, Mohler PJ, Arendshorst WJ. Expression and relative abundance of short transient receptor potential channels in the rat renal microcirculation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 286: F546–F551, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Facemire CS, Arendshorst WJ. Calmodulin mediates norepinephrine-induced receptor-operated calcium entry in preglomerular resistance arteries. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 289: F127–F136, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fellner SK, Arendshorst WJ. Capacitative calcium entry in smooth muscle cells from preglomerular vessels. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 277: F533–F542, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fellner SK, Arendshorst WJ. Ryanodine receptor and capacitative Ca2+ entry in fresh preglomerular vascular smooth muscle cells. Kidney Int 58: 1686–1694, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fellner SK, Arendshorst WJ. Store-operated Ca2+ entry is exaggerated in fresh preglomerular vascular smooth muscle cells of SHR. Kidney Int 61: 2132–2141, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fellner SK, Arendshorst WJ. Angiotensin II Ca2+ signaling in rat afferent arterioles: stimulation of cyclic ADP ribose and IP3 pathways. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 288: F785–F791, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fellner SK, Arendshorst WJ. Endothelin-A and -B receptors, superoxide, and Ca2+ signaling in afferent arterioles. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F175–F184, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fellner SK, Arendshorst WJ. Voltage-gated Ca2+ entry and ryanodine receptor Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release in preglomerular arterioles. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F1568–F1572, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galione A, Churchill GC. Interactions between calcium release pathways: multiple messengers and multiple stores. Cell Calcium 32: 343–354, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gambara G, Billington RA, Debidda M, D'Alessio A, Palombi F, Ziparo E, Genazzani AA, Filippini A. NAADP-induced Ca2+ signaling in response to endothelin is via the receptor subtype B and requires the integrity of lipid rafts/caveolae. J Cell Physiol 216: 396–404, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gottschalk CW Renal nerves and sodium excretion. Annu Rev Physiol 41: 229–240, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guse AH, Lee HC. NAADP: a universal Ca2+ trigger. Sci Signal 1: re10, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Hayashi K, Wakino S, Sugano N, Ozawa Y, Homma K, Saruta T. Ca2+ channel subtypes and pharmacology in the kidney. Circ Res 100: 342–353, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iversen BM, Arendshorst WJ. ANG II and vasopressin stimulate calcium entry in dispersed smooth muscle cells of preglomerular arterioles. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 274: F498–F508, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kinnear NP, Boittin FX, Thomas JM, Galione A, Evans AM. Lysosome-sarcoplasmic reticulum junctions: a trigger zone for calcium signaling by nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate and endothelin-1. J Biol Chem 279: 54319–54326, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kinnear NP, Wyatt CN, Clark JH, Calcraft PJ, Fleischer S, Jeyakumar LH, Nixon GF, Evans AM. Lysosomes co-localize with ryanodine receptor subtype 3 to form a trigger zone for calcium signalling by NAADP in rat pulmonary arterial smooth muscle. Cell Calcium 44: 190–201, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee HC, Walseth TF, Bratt GT, Hayes RN, Clapper DL. Structural determination of a cyclic metabolite of NAD+ with intracellular Ca2+-mobilizing activity. J Biol Chem 264: 1608–1615, 1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee HC Nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP)-mediated calcium signaling. J Biol Chem 280: 33693–33696, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Naylor E, Arredouani A, Vasudevan SR, Lewis AM, Parkesh R, Mizote A, Rosen D, Thomas JM, Izumi M, Ganesan A, Galione A, Churchill GC. Identification of a chemical probe for NAADP by virtual screening. Nat Chem Biol 5: 220–226, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nelson N Structural conservation and functional diversity of V-ATPases. J Bioenerg Biomembr 24: 407–414, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pollock DM, Jenkins JM, Cook AK, Imig JD, Inscho EW. L-type calcium channels in the renal microcirculatory response to endothelin. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 288: F771–F777, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Putney J Recent breakthroughs in the molecular mechanism of capacitative calcium entry (with thoughts on how we got here). Cell Calcium 42: 103–110, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rothenberger F, Velic A, Stehberger PA, Kovacikova J, Wagner CA. Angiotensin II stimulates vacuolar H+-ATPase activity in renal acid-secretory intercalated cells from the outer medullary collecting duct. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2085–2093, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salomonsson M, Arendshorst WJ. Calcium recruitment in renal vasculature: NE effects on blood flow and cytosolic calcium concentration. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 276: F700–F710, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salomonsson M, Arendshorst WJ. Norepinephrine-induced calcium signaling pathways in afferent arterioles of genetically hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 281: F264–F272, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salomonsson M, Sorensen CM, Arendshorst WJ, Steendahl J, Holstein-Rathlou NH. Calcium handling in afferent arterioles. Acta Physiol Scand 181: 421–429, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schneider MP, Boesen EI, Pollock DM. Contrasting actions of endothelin ETA and ETB receptors in cardiovascular disease. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 47: 731–759, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang WX, Chen YF, Zou AP, Campbell WB, Li Role of FKBP12 PL.6. in cADPR-induced activation of reconstituted ryanodine receptors from arterial smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 282: H1304–H1310, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thai TL, Fellner SK, Arendshorst WJ. ADP-ribosyl cyclase and ryanodine receptor activity contribute to basal renal vasomotor tone and agonist-induced renal vasoconstriction in vivo. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F1107–F1114, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thai TL, Arendshorst WJ. ADP-ribosyl cyclase and ryanodine receptors mediate endothelin ETA and ETB receptor-induced renal vasoconstriction in vivo. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F360–F368, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thorneloe KS, Nelson MT. Ion channels in smooth muscle: regulators of intracellular calcium and contractility. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 83: 215–242, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Troncoso Brindeiro CM, Fallet RW, Lane PH, Carmines PK. Potassium channel contributions to afferent arteriolar tone in normal and diabetic rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F171–F178, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamada H, Hayashi M, Uehara S, Kinoshita M, Muroyama A, Watanabe M, Takei K, Moriyama Y. Norepinephrine triggers Ca2+-dependent exocytosis of 5-hydroxytryptamine from rat pinealocytes in culture. J Neurochem 81: 533–540, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamasaki M, Churchill GC, Galione A. Calcium signalling by nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP). FEBS J 272: 4598–4606, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamasaki M, Thomas JM, Churchill GC, Garnham C, Lewis AM, Cancela JM, Patel S, Galione A. Role of NAADP and cADPR in the induction and maintenance of agonist-evoked Ca2+ spiking in mouse pancreatic acinar cells. Curr Biol 15: 874–878, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yusufi AN, Cheng J, Thompson MA, Chini EN, Grande JP. Nicotinic acid-adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP) elicits specific microsomal Ca2+ release from mammalian cells. Biochem J 353: 531–536, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang AY, Li PL. Vascular physiology of a Ca2+ mobilizing second messenger—cyclic ADP-ribose. J Cell Mol Med 10: 407–422, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang F, Jin S, Yi F, Li PL. TRP-ML1 functions as a lysosomal NAADP-sensitive Ca2+ release channel in coronary arterial myocytes. J Cell Mol Med. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Zhang F, Zhang G, Zhang AY, Koeberl MJ, Wallander E, Li PL. Production of NAADP and its role in Ca2+ mobilization associated with lysosomes in coronary arterial myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H274–H282, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]