Abstract

Fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF23) is a phosphaturic hormone that contributes to several hypophosphatemic disorders by reducing the expression of the type II sodium-phosphate cotransporters (NaPi-2a and NaPi-2c) in the kidney proximal tubule and by reducing serum 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 [1,25(OH)2D3] levels. The FGF receptor(s) mediating the hypophosphatemic action of FGF23 in vivo have remained elusive. In this study, we show that proximal tubules express FGFR1, −3, and −4 but not FGFR2 mRNA. To determine which of these three FGFRs mediates FGF23's hypophosphatemic actions, we characterized phosphate homeostasis in FGFR3−/− and FGFR4−/− null mice, and in conditional FGFR1−/− mice, with targeted deletion of FGFR1 expression in the metanephric mesenchyme. Basal serum phosphorus levels and renal cortical brush-border membrane (BBM) NaPi-2a and NaPi-2c expression were comparable between FGFR1−/−, FGFR3−/−, and FGFR4−/− mice and their wild-type counterparts. Administration of FGF23 to FGFR3−/− mice induced hypophosphatemia in these mice (8.0 ± 0.4 vs. 5.4 ± 0.3 mg/dl; p ≤ 0.001) and a decrease in renal BBM NaPi-2a and NaPi-2c protein expression. Similarly, in FGFR4−/− mice, administration of FGF23 caused a small but significant decrease in serum phosphorus levels (8.7 ± 0.3 vs. 7.6 ± 0.4 mg/dl; p ≤ 0.001) and in renal BBM NaPi-2a and NaPi-2c protein abundance. In contrast, injection of FGF23 into FGFR1−/− mice had no effects on serum phosphorus levels (5.6 ± 0.3 vs. 5.2 ± 0.5 mg/dl) or BBM NaPi-2a and NaPi-2c expression. These data show that FGFR1 is the predominant receptor for the hypophosphatemic action of FGF23 in vivo, with FGFR4 likely playing a minor role.

Keywords: phosphaturia, phosphorus, proximal tubule

phosphate homeostasis is important for many biological processes. A large body of in vivo and in vitro studies has shown that fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF23) is a key regulator of phosphate homeostasis. Mice treated with recombinant FGF23 or transgenic mice overexpressing FGF23 have hypophosphatemia, decreased expression of renal cortical brush-border membrane (BBM) type II sodium-phosphate cotransporter (NaPi-2a and NaPi-2c) protein along with decreased serum levels of 1,25(OH)2D3 (4, 6, 31, 38, 57, 61, 63, 65, 67). FGF23−/− mice, on the other hand, have hyperphosphatemia, increased expression of renal cortical BBM NaPi-2a protein along with increased serum levels of 1,25(OH)2D3 (64, 68).

Several acquired and inherited hypophosphatemic disorders have been associated with upregulation of FGF23. In tumor-induced osteomalacia, high FGF23 levels are produced by the tumor (11, 17, 33, 65). Autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets (ADHR) is due to a missense mutation in the FGF23 gene, resulting in high serum levels of protease-resistant FGF23 (2, 66, 74). X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets (XLH), another inherited hypophosphatemic disorder, is due to a mutation in the PHEX gene (phosphate-regulating gene with homologies to endopeptidases on the X-chromosome), resulting in high serum FGF23 levels (7, 16, 20, 30, 33, 43, 78). In autosomal recessive hypophosphatemic rickets, mutations in the dentin matrix protein-1 gene cause elevated serum levels of FGF23 (19, 44). Some patients with McCune-Albright syndrome, which is due to a somatic mutation in GNAS-1, encoding the α-subunit of stimulatory G protein, also have elevated FGF23 levels and hypophosphatemia (55, 60, 62, 71).

FGF23 is an endocrine member of the FGF family of ligands that mediate their action by binding to and activating FGF receptors (FGFRs) in a heparan sulfate (HS)-dependent fashion (23, 32). Four distinct genes code for FGFRs (FGFR1-FGFR4). A prototypical FGFR consists of an extracellular domain made up of three immunoglobulin-like domains (D1–D3), a single-pass transmembrane domain, and an intracellular domain which contains tyrosine kinase activity (54, 56, 58). A major tissue-specific alternative splicing event in the second half of D3 of FGFR1–3 creates epithelial lineage-specific “b” (FGFR1b-FGFR3b) and mesenchymal lineage-specific “c” (FGFR1c-FGFR3c) isoforms with distinct ligand-binding specificity (46, 49, 54). A structural divergence at the HS binding site of FGF23 reduces FGF23 HS binding affinity to enable this ligand to function in an endocrine fashion (24). FGF23 requires Klotho as a coreceptor, which simultaneously interacts with FGF23 and its cognate FGFR(s) to stabilize FGF23-FGFR binding (36, 37, 70). Thus far, studies published have demonstrated that FGFs bind to FGFRs in a 2:2 FGF-FGFR dimer with heparin sulfate interacting both with the FGFR and FGF (24, 52, 59). Immunoprecipitation studies have shown that for FGF23, Klotho forms a ternary complex with FGF23 and FGFRs (37, 70). No studies have reported heterodimerizing of the FGFRs or the interaction between the different FGFRs.

The FGFR(s) mediating the actions of FGF23 remain controversial. Studies analyzing FGF23-FGFR interaction by surface plasmon resonance (SPR) spectroscopy and measurement of the mitogenic response of BaF3 cells ectopically expressing different FGFRs in the presence of FGF23 have shown that FGF23 binds to and activates FGFR1c, 2c, 3c, and FGFR4 (79, 80). However, another study employing SPR spectroscopy showed that FGF23 binds to FGFR2c and FGFR3c but not to FGFR1c (77). Controversy exists about the specific receptor for FGF23 using cell lines transfected with Klotho and different FGFRs (37, 70). One study showed that FGF23 bound to binary complexes of Klotho with FGFR1c, FGFR3c or FGFR4 (37), whereas another study found that FGF23 exclusively binds to FGFR1c-Klotho (70). Finally, it was shown recently that deletion of FGFR3 or FGFR4 in Hyp mice, a mouse model of human XLH, did not correct the hypophosphatemia in those mice (42). Based on these data, it was concluded that neither FGFR3 nor FGFR4 mediates the phosphaturic activity of FGF23.

The objective of this study was to identify the FGFR(s) responsible for the hypophosphatemic action of FGF23 in vivo. This study delineated the FGFRs on the proximal tubule and used different FGFR−/− mice to examine phosphate regulation at baseline and their response to pharmacological doses of FGF23. Our findings demonstrate the FGFR1 is the predominant receptor mediating the hypophosphatemic action of FGF23.

METHODS

FGFR−/− mice.

Generation of FGFR3−/− and FGFR4−/− mice has previously been described (13, 72). The FGFR4−/− and FGFR3−/− mice are from a mixed 129/Black Swiss background (72). These mice were genotyped before the study to confirm that they had deletion of all splice variants of FGFR3 or FGFR4. Control mice were from the same mixed genetic background as FGFR3−/− and FGFR4−/− mice (13, 72). FGFR1−/− mice are embryonically lethal (15, 76). Therefore, the FGFR1−/− mice used in this study were conditional FGFR1−/− mice where FGFR1 was deleted from the metanephric mesenchyme using the lox-p/cre recombinase technique as described previously (53). Transgenic mice with cre recombinase under the Pax3 promoter (40) were cross bred with mice that had the lox-p sites flanking the critical regions of the FGFR1 gene (29). Cre recombinase under the Pax3 promoter has been shown to express cre recombinase in the metanephric mesenchyme and not in the ureteric bud (18). Deletion of FGFR1 from metanephric mesenchyme will delete the receptor from the proximal tubule, the site of 80% of phosphate reabsorption (8, 69). As FGFR1−/− mice were from a different genetic background, separate controls of the same genetic background as the FGFR1−/− mice were studied and designated as control-1. FGFR1−/− mice were from a mixed genetic background including 129/Sv and C57BL/6J and so were their controls (Control-1) (18, 29, 40). FGFR2−/− mice are also embryonically lethal, and FGFR2 has not been shown to bind to FGF23 and initiate intracellular signaling (3, 37, 70, 75). Thus FGFR2−/− mice were not studied. The mice were studied at 2–4 mo of age and were housed at the animal facility at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center as per recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals with 12:12-h light-dark cycles. Mice were fed a standard rodent diet (diet 7001, Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI, with 2% calcium and 0.94% phosphorus) and had access to water ad libitum. The weights of the different FGFR−/− mice were comparable (data not shown). These studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

Recombinant FGF23 administration.

Human recombinant FGF23 carrying the R176Q and R179Q ADHR mutations (24) was injected intraperitoneally (ip) into FGFR3−/−, FGFR4−/−, and FGFR1−/− mice, and their wild-type counterparts. FGF23 was injected at 12-h intervals for 4 days at the dose of 12 μg·injection−1·mouse−1 as previously described (51). This protocol has previously been shown to decrease 25-hydroxyvitamin D-1α-hydroxylase mRNA abundance and increase 24-hydroxylase mRNA abundance (51). Serum/tissue samples were collected 10–12 h after the last injection. Vehicle (protein sample buffer consisting of 25 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.5, and 1 M NaCl) was administered as a control.

Proximal tubule isolation and RT-PCR.

Kidneys from control and FGFR1−/− mice were quickly removed after the mice were killed. Kidneys were sliced coronally and placed in 10 ml DMEM (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY) containing 1 mg/ml collagenase (Worthington, Lakewood, NJ), and the mixture was shaken vigorously for 15 min in a 5% CO2 chamber at 37°C. The partially digested kidneys were then transferred into Hanks' solution containing (in mM) 137 NaCl, 5 KCl, 0.8 MgSO4, 0.33 Na2HPO4, 0.44 KH2PO4, 1 MgCl2, 10 Tris, 0.25 CaCl2, 2 glutamine, and 2 l-lactate at 4°C. Proximal convoluted tubules (∼20 mm) were dissected and placed in 200 μl of RNA extraction buffer. RNA was then isolated using the Mini RNA isolation kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Zymo Research, Orange, CA). Cells to c-DNA II kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) was used to make cDNA from RNA as per the manufacturer's protocol. The negative control was the preparation without the reverse transcriptase. mRNA was amplified by PCR using a thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) (1). The PCR reaction steps included initial activation of HotStar Taq DNA Polymerase (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) at 95°C for 15 min, 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 45 s, annealing at 55°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 1 min. The final extension step was for 10 min at 72°C. The PCR product obtained was fractionated on a 1% agarose gel with ethidium bromide and visualized by UV transillumination. The PCR primers used are as follows: FGFR1 (forward) 5′-TTC AAG CTG CTG AAG GA and (reverse) 5′-GTC TTG GGG GTG ATG GA; FGFR2 (forward) 5′-CAG GGA TTC CCG TGG A and (reverse) 5′-TGT CCT GTT TGG GGA CA; FGFR3 (forward) 5′-TCT GGG CTA AGG ATG GTA and (reverse) 5′-CAG GTA TAG TTG CCA CGA or FGFR3 (forward) 5′-TGC GTG TAA CAG ATG CTC CAT CCT and (reverse) 5′-AGG GTA CCA CAC TTT CCA TGA CCA; FGFR4 (forward) 5′-TGG AAG GAA ATG TGG CTG CTC TTG and (reverse) 5′-AGA TTG TGT ACG ACG GTC ATG GAG; and GAPDH (forward) 5′-CAC CAT GGA GAA GGC and (reverse) 5′-TGC CAG TGA GCT TCC.

Serum phosphorus and serum creatinine levels.

Blood was collected from the retroorbital vein after the mice were sedated with isoflurane. Serum phosphorus was measured using the Phosphorus Liqui-UV Test (Stanbio Laboratories, Boerne, TX) as per the manufacturer's protocol. Serum creatinine was measured by the Vitros 250 instrument using an enzymatic creatinine amidohydrolase reaction (Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics, Rochester, NY).

Baseline serum FGF23, parathyroid hormone, and 1,25(OH)2D3 levels.

Blood collected from the retroorbital vein was also used to measure the concentrations of FGF23, parathyroid hormone (PTH) and 1,25(OH)2D3. Serum samples were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until the time of assay. Serum PTH concentration was measured by ELISA using an intact mouse PTH kit (Immutopics, San Clemente, CA). Serum FGF23 levels were measured by ELISA using an FGF23 kit (Kainos Laboratories, Tokyo, Japan). Serum 1,25(OH)2D3 levels were measured by RIA using a Gamma-B 1,25-Dihydroxy Vitamin D kit (IDS, Tyne and Wear, UK).

BBM vesicle isolation, SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotting.

Kidneys were quickly removed and placed in ice-cold PBS. The renal cortex was dissected and placed in ice-cold isolation buffer (300 mM mannitol, 16 mM HEPES, and 5 mM EGTA titrated to pH 7.4 with Tris). One microliter per milliliter of protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and 100 μg/ml PMSF (Calbiochem) were added to the isolation buffer. The cortex was homogenized using a Potter Ejevhem homogenizer at 4°C. Using magnesium precipitation and differential centrifugation, BBM vesicles (BBMV) were isolated as described previously (5, 28). RIPA buffer was used to suspend the final BBMV pellet (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris, 5 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% deoxycholate, and 0.1% SDS). BBMV total protein was measured by the Bradford method using BSA as the standard. An equal amount of protein (25 μg) was denatured at 37°C after the samples were diluted with SDS-PAGE loading buffer. BBMV proteins were then fractionated on a 7.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were then transferred at 350–450 mA over 1 h to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The blot was blocked by Blotto (0.05% Tween 20 and 5% nonfat milk in PBS) for 1 h and then probed using a primary antibody to NaPi-2a (1:4,000) or NaPi-2c (1:4,500) overnight at 4°C (generous gifts from Drs. J. Biber and H. Murer, University of Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland). The blots were washed extensively with Blotto and then incubated with the secondary anti-rabbit antibody at 1:10,000 dilution for 1 h. The blots were further washed with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20. Enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Life Sciences) was used to detect bound antibody. An antibody to β-actin at 1:15,000 dilution was used to validate equal loading of the protein (Sigma). NaPi-2a and NaPi-2c protein abundance was quantified in relation to β-actin using Scion Image software (Scion).

Statistical analysis.

All the data are expressed as means ± SE. Student's t-test was used to assess the difference between two groups. Differences among multiple groups were assessed using one-way ANOVA followed by a post hoc Student-Newman-Keuls test. A P value <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

To identify the FGFR(s) that mediate FGF23's action in vivo, we studied phosphate homeostasis in mice deficient for each of the four FGFRs before and after administration of recombinant FGF23. We reasoned that mice lacking FGF23's principal FGFR should exhibit hyperphosphatemia, increased expression of renal cortical BBM NaPi-2a and NaPi-2c protein, elevated serum levels of 1,25(OH)2D3 along with increased serum levels of FGF23 due to the negative feedback regulation. Second, we reasoned that administration of recombinant FGF23 into mice deficient in the principal FGFR should not cause hypophosphatemia.

We first determined which FGFRs were present in the proximal convoluted tubule, the nephron segment where at least 80% of phosphorus is reabsorbed (8, 69). RT-PCR showed that FGFR1, -3, and -4, but not FGFR2, mRNA are expressed in the proximal convoluted tubule (Fig. 1A). Previous studies showed that while all the splice variants of FGFR1–3 were expressed in the adult rat renal cortex (12), only FGFR3 was localized to the proximal tubule using immunohistochemistry (12, 42). Immunohistochemistry in the adult mouse showed localization of FGFR1 in the distal tubule (42). The discrepancy between the two results is that the expression of FGFR1 is likely lower in the proximal tubule and thus not detected by immunohistochemistry but still detected by RT-PCR, a more sensitive technique.

Fig. 1.

A: mRNA expression of different FGF receptors (FGFRs) in the proximal tubule. Proximal tubules were dissected, total RNA was isolated, and the products of RT-PCR were fractionated on a 1% agarose gel. FGFR1, FGFR3, and FGFR4 but not FGFR2 mRNA are expressed in the proximal tubule. The details of the primer sequences are described in methods. Either of the FGFR3 primer sets was used. The negative control for each primer set was a RT-PCR in which RT (reverse transcriptase) was omitted. B: absence of FGFR1 transcript in the proximal tubule of FGFR1−/− mice. Proximal tubules were dissected, total RNA was isolated, and the products of RT-PCR were fractionated on a 1% agarose gel. FGFR1 mRNA was not detected in the proximal tubules of FGFR1−/− mice, whereas FGFR3 and FGFR4 mRNA are expressed in the proximal tubule. RT-PCR in which RT was omitted served as a negative control, and mRNA from a wild-type mouse was used as a positive control.

Based on these data, we decided to study phosphate homeostasis in mice null for FGFR1, FGFR3, or FGFR4. Since FGFR1 deletion leads to embryonic lethality, we studied conditional FGFR1−/− mice where FGFR1 is deleted from the metanephric mesenchyme using a lox-p/cre recombinase technique. As is shown in Fig. 1B, FGFR1 mRNA is deleted from these mice but FGFR3 and FGFR4 mRNA are expressed.

In the first set of experiments, we examined basal serum phosphorus levels and renal cortical BBM NaPi-2a and NaPi-2c protein expression in FGFR−/− mice along with serum levels of PTH, FGF23, and 1,25(OH)2D3, all of which are known regulators of serum phosphorus. As shown in Figs. 2 and 3, there was no increase in the serum phosphorus levels and renal cortical BBM NaPi-2a or NaPi-2c protein expression in FGFR−/− mice relative to their respective controls. Basal serum FGF23 levels were higher in FGFR1−/− and FGFR4−/− mice relative to their controls (Table 1). The maintenance of phosphate homeostasis in FGFR1−/− and FGFR4−/− mice despite higher FGF23 levels is likely due to compensatory mechanisms. Some of the compensatory mechanisms might include increased expression of other receptors or some yet unidentified mechanisms. FGF23 levels were higher in vehicle-treated control and FGFR4−/− mice compared with baseline FGF23 levels, and the reason for this disparity is unclear. Serum levels of 1,25(OH)2D3 were significantly elevated in FGFR3−/− mice and also tended to be higher in FGFR4−/− mice compared with control mice (P = 0.1). Serum PTH levels at baseline tended to be higher in FGFR3−/− mice compared with their controls but did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.1) (Table. 1). Serum creatinine was measured as described in methods, and all the mice had comparable creatinine levels [control 0.18 ± 0.007, FGFR3−/− 0.16 ± 0.009, and FGFR4−/− 0.166 ± 0.009 mg/dl, P = not significant (NS); control-1, 0.14 ± 0.03 and FGFR1−/− 0.14 ± 0.009 mg/dl, P = NS].

Fig. 2.

Renal cortical brush-border membrane (BBM) type II sodium-phosphate cotransporter (NaPi-2a) protein expression in FGFR−/− mice at baseline. NaPi-2a expression relative to β-actin from renal cortical BBMV of FGFR−/− mice was analyzed by immunoblotting. NaPi-2a expression at baseline did not differ between FGFR−/− mice and their respective controls. Values are means ± SE.

Fig. 3.

Renal cortical BBM NaPi-2c protein expression in FGFR−/− mice at baseline. NaPi-2c expression relative to β-actin from renal cortical BBM vesicles (BBMV) of FGFR−/− mice was analyzed by immunoblotting. NaPi-2c expression at baseline did not differ between FGFR−/− mice and their respective controls. Values are means ± SE.

Table 1.

Baseline data in different FGFR−/− mice

| Control-1 | FGFR1−/− | Control | FGFR3−/− | FGFR4−/− | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum phosphorus, mg/dl | 6.6±0.4 (n=16) | 6.2±0.4 (n=15) | 7.6±0.4 (n=12) | 7.0±0.4 (n=12) | 7.9±0.4 (n=12) |

| Serum FGF23, pg/ml | 116.9±7.5 (n=23) | 173.9±17.3† (n=21) | 151.3±9.6 (n=15) | 140.4±11.4 (n=16) | 190.7±10.4*‡ (n=14) |

| Serum 1,25(OH)2D3, pmol/l | 81.1±11.0 (n=16) | 85.8±13.0 (n=15) | 88.9±15.9 (n=10) | 208.7±27.3*(n=11) | 154.2±35.0 (n=10) |

| Serum PTH, pg/ml | 148.4±16.1 (n=14) | 115.2±17.6 (n=17) | 130.4±26.6 (n=29) | 213.6±41.3 (n=31) | 100.9±16.3 (n=21) |

Values are means ± SE; n=no. of mice. FGFR, FGF receptor; PTH, parathyroid hormone.

P < 0.05 vs. control.

P < 0.05 vs. control-1.

P < 0.05 vs. FGFR3−/−.

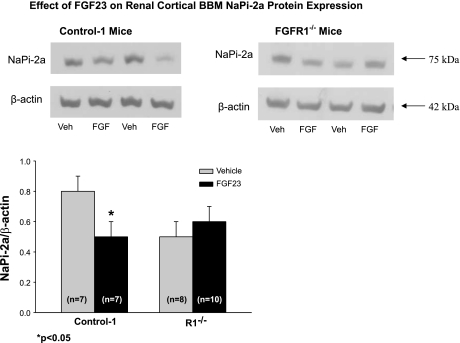

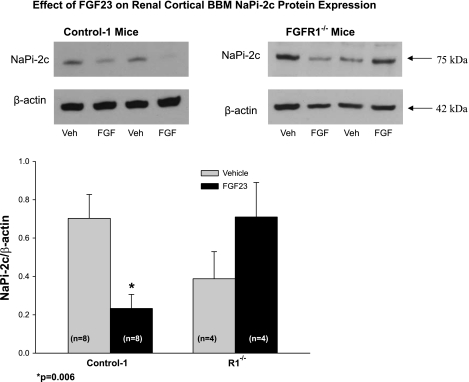

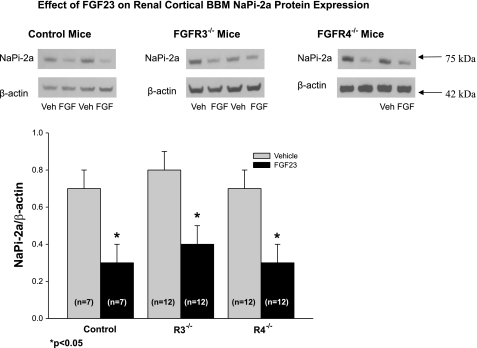

We next examined the effects of pharmacological doses of FGF23 on serum phosphorus, 1,25(OH)2D3, and PTH and on renal cortical BBM NaPi-2a and NaPi-2c protein expression. To ensure that all the animals that received FGF23 expressed high FGF23 levels, serum FGF23 levels were measured 10–12 h after the last injection of FGF23 and the FGF23 levels were indeed higher in the group that received FGF23 (Tables 2 and 3). FGF23 levels were higher in vehicle-treated control and FGFR4−/− mice compared with baseline FGF23 levels. The reason for this disparity is unclear. As shown in Table 2, serum phosphorus decreased in control-1 mice on administration of FGF23. Similarly, renal cortical BBM NaPi-2a and NaPi-2c protein expression also decreased in control-1 mice that received FGF23 (Figs. 4 and 5). As shown in Table 3, serum phosphorus levels also decreased in FGFR3−/− and FGFR4−/− mice and in their controls with administration of FGF23. As expected, a decrease in renal cortical BBM NaPi-2a and NaPi-2c protein expression was noted in FGFR3−/− and FGFR4−/− mice and in their controls with administration of FGF23 (Figs. 6 and 7). In contrast, serum phosphorus levels did not decrease in FGFR1−/− mice in response to FGF23 administration (Table 2). Similarly, renal cortical BBM NaPi-2a and NaPi-2c protein expression did not change in FGFR1−/− mice in response to FGF23 injection (Figs. 4 and 5). All FGFR−/− mice and their respective controls showed a decrease in 1,25(OH)2D3 levels in response to FGF23 treatment (Tables 2 and 3). Serum PTH levels were reduced in FGFR1−/− mice after administration of FGF23 compared with the vehicle-treated mice, but the effect did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.1) (Table 2). In FGFR3−/− and FGFR4−/− mice, there was no change in serum PTH levels in response to FGF23 injection. Furthermore, serum PTH levels were significantly elevated in vehicle-treated FGFR1−/− and FGFR3−/− mice compared with the respective vehicle-treated controls, which contrasts with the baseline results (compare Tables 2 and 3 with Table 1). However, at baseline, serum PTH levels were higher in FGFR3−/− mice compared with control mice (130 ± 26 vs. 213 ± 41 pg/ml) but did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.1). The reason for this disparity is unclear, but the vehicle-treated mice were handled and injected twice daily.

Table 2.

Serum parameters in control-1 and FGFR1−/− mice post-FGF23 administration

| Control-1 |

FGFR1−/− | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | FGF23 | Vehicle | FGF23 | |

| Serum phosphorus, mg/dl (pre- vs. post-FGF23 | 5.9±0.4 vs. 6.6±0.3 (n=11) | 5.8±0.3 vs. 4.2±0.4*(n=11) | 6.2±0.5 vs. 6.9±0.5 (n=8) | 5.6±0.3 vs. 5.2±0.5 (n=10) |

| Serum FGF23, pg/ml | 137.8±3.4 (n=6) | 809.7±75.2‡ (n=6) | 247.0±32.7§ (n=8) | 941.1±184.3† (n=10) |

| Serum 1,25(OH)2D3, pmol/l | 87.5±18.7 (n=8) | 11.8±0.7‡ (n=10) | 86.8±20.1 (n=6) | 11.3±0.8‡ (n=7) |

| Serum PTH, pg/ml | 122.8±16.4 (n=13) | 107.8±27.4 (n=10) | 209.4±42.1§ (n=10) | 130.8±15.8 (n=8) |

Values are means ± SE; n = no. of mice.

P < 0.05, pre vs. post-FGF23.

P ≤ 0.005, vehicle vs. FGF23.

P ≤ 0.001, vehicle vs. FGF23.

P=0.05, control-1 vehicle vs. FGFR1−/− vehicle.

Table 3.

Serum parameters in control, FGFR3−/−, and FGFR4−/− mice post-FGF23 administration

| Control |

FGFR3−/− | FGFR4−/− | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | FGF23 | Vehicle | FGF23 | Vehicle | FGF23 | |

| Serum phosphorus, mg/dl (pre- vs. post-FGF23 | 7.7±0.3 vs. 8.1±0.5 (n=12) | 8.5±0.4 vs. 6.5±0.5a (n=12) | 8.4±0.6 vs. 8.9±0.4 (n=12) | 8.0±0.4 vs. 5.4±0.3a (n=12) | 8.4±0.6 vs. 9.0±0.5 (n=12) | 8.7±0.3 vs. 7.6±0.4a (n=12) |

| Serum FGF23, pg/ml | 239±29.5 (n=6) | 1011.5±216.7d (n=6) | 201.2±53.7 (n=6) | 1,658.1±223.3c (n=6) | 279±32.6 (n=6) | 1,548.4±135.2c (n=6) |

| Serum 1,25(OH)2D3, pmol/) | 78.4±32.4 (n=6) | 7.4±0.6b (n=6) | 171.4±28.7 (n=10) | 14.9±5.7d (n=6) | 121.0±17.3 (n=6) | 33.8±6.2d (n=6) |

| Serum PTH, pg/ml | 88.2±18.9 (n=6) | 75.1±20.0 (n=6) | 244.4±31.9e (n=6) | 253.0±55.6 (n=6) | 117.2±25.2f (n=13) | 162.4±39.4 (n=10) |

Values are means ± SE.

P ≤ 0.001, pre- vs. post-FGF23.

P ≤ 0.05, vehicle vs. FGF23.

P < 0.001, vehicle vs. FGF23.

P ≤ 0.005, vehicle vs. FGF23.

P < 0.05, control vehicle vs. FGFR3−/− vehicle.

P < 0.05 FGFR3−/− vehicle vs. FGFR4−/− vehicle.

Fig. 4.

Effect of exogenous FGF23 on renal cortical BBMV NaPi-2a expression in FGFR1−/− mice. Shown are immunoblots of renal cortical BBM NaPi-2a and β-actin. NaPi-2a protein expression (relative to β-actin expression) did not change in FGFR1−/− mice in response to FGF23 treatment, whereas, as expected, it decreased significantly in wild-type mice. Values are means ± SE.

Fig. 5.

Effect of exogenous FGF23 on renal cortical BBMV NaPi-2c expression in FGFR1−/− mice. Shown are immunoblots of renal cortical BBM NaPi-2c and β-actin. NaPi-2c protein expression (relative to β-actin expression) did not change in FGFR1−/− mice in response to FGF23 treatment, while, as expected, it decreased significantly in wild-type mice. Values are means ± SE.

Fig. 6.

Effect of exogenous FGF23 on renal cortical BBM NaPi-2a protein expression in FGFR3−/− and FGFR4−/− Mice. Shown are immunoblots of renal cortical BBM NaPi-2a and β-actin. After FGF23 administration, NaPi-2a (relative to β-actin expression) significantly decreased in FGFR3−/− and FGFR4−/− mice similar to that seen in their wild-type counterparts. Values are means ± SE.

Fig. 7.

Effect of Exogenous FGF23 on renal cortical BBM NaPi-2c protein expression in FGFR3−/− and FGFR4−/− mice. Shown are immunoblots of renal cortical BBM NaPi-2c and β-actin. After FGF23 administration, NaPi-2c (relative to β-actin expression) significantly decreased in FGFR3−/− and FGFR4−/− mice similar to that seen in their wild-type counterparts. Values are means ± SE.

Mice overexpressing FGF23 have hypophosphatemia, decreased expression of renal cortical BBM NaPi-2a and NaPi-2c protein along with decreased serum levels of 1,25(OH)2D3 (4, 6, 31, 38, 57, 61, 63, 65, 67). On the contrary, mice with deletion of FGF23 have hyperphosphatemia, increased expression of renal cortical BBM NaPi-2a protein along with increased serum levels of 1,25(OH)2D3 (64, 68). Therefore, we reasoned that if the critical receptor for the hypophosphatemic action of FGF23 is deleted, the mice with this deletion will have hyperphosphatemia, increased BBM NaPi-2a and NaPi-2c expression, and increased serum levels of 1,25(OH)2D3. The explanation for this phenotype not occurring is that it is unlikely that a single receptor is responsible for the hypophosphatemic action of FGF23. Although FGFR1 is the predominant receptor for the hypophosphatemic action of FGF23, these mice have normal phosphate homeostasis, indicating that compensatory mechanisms exist to maintain normal phosphate homeostasis at baseline. Together, these data show that FGFR1 is the predominant receptor mediating the hypophosphatemic action of FGF23 although a relatively minor role for FGFR4 cannot be ruled out.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we showed that the proximal convoluted tubule expresses FGFR1, FGFR3, and FGFR4 mRNA. Based on these data, serum phosphorus, FGF23, PTH, and 1,25(OH)2D3 levels along with renal cortical BBM NaPi-2a and NaPi-2c protein expression were examined in FGFR1−/−, FGFR3−/−, and FGFR4−/− mice before and after administration of recombinant FGF23. Analysis of the basal serum phosphorus levels and renal cortical BBM NaPi-2a and NaPi-2c expression did not implicate any of these FGFRs in mediating FGF23's hypophosphatemic activity as these parameters were comparable between FGFR1−/−, FGFR3−/−, and FGFR4−/− mice and their wild-type counterparts. Injection of recombinant FGF23 decreased the serum phosphorus and renal cortical BBM NaPi-2a and NaPi-2c protein expression in FGFR3−/− and FGFR4−/− mice. FGFR1−/− mice, however, did not respond to exogenous FGF23 with hypophosphatemia or decrease in renal cortical BBM NaPi-2a or NaPi-2c protein expression, indicating that FGFR1 is the primary receptor for the hypophosphatemic action of FGF23.

Interestingly, relative to their respective control mice, FGFR1−/− mice had higher serum FGF23 levels, which probably reflects the presence of negative feedback regulation. Even with high FGF23 levels, serum phosphorus levels are normal in FGFR1−/− mice, which indicates that compensatory mechanisms are responsible for preventing high serum phosphorus levels. The role for FGFR4 in FGF23's hypophosphatemic activity is uncertain from our data. At baseline, FGFR4−/− mice had higher serum FGF23 levels, but the serum FGF23 levels were comparable in control and FGFR4−/− mice post-vehicle administration. The reason for this discrepancy in the serum FGF23 levels is unclear. Unlike FGFR1−/− mice, FGFR4−/− mice responded to administration of FGF23 with a small but significant decrease in serum phosphorus and cortical BBM NaPi-2a and NaPi-2c protein expression. It should be noted that the decrease in serum phosphorus was less in FGFR4−/− mice (1.2 ± 0.3 mg/dl) compared with control mice (2.0 ± 0.5 mg/dl), although this did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.1). Taken together, our data show that FGFR1 is the predominant receptor for the hypophosphatemic action of FGF23, and FGFR4 might play a minor role.

Both FGFR1 and FGFR3 were shown to be present in parathyroid gland tissue by immunohistochemistry (9). The role of FGF23 in the regulation of PTH remains controversial. Studies so far have suggested both positive and negative regulation of PTH by FGF23. In rats, acute exposure to FGF23 results in a decrease in PTH mRNA expression and PTH secretion (9). This is in contrast to what is seen in transgenic mice overexpressing FGF23 (chronic exposure), where PTH levels were elevated compared with controls (4, 38), which could be explained by the fact that FGF23 decreases serum 1,25(OH)2D3 levels in vivo (41, 50, 63), which in turn would stimulate PTH secretion (34, 48). In an in vitro study, where the confounding effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 was excluded, incubation of bovine parathyroid cells with FGF23 resulted in a decrease in PTH mRNA expression and PTH secretion (35). In our study, there was a tendency for higher PTH levels at baseline in FGFR3−/− mice, which could be explained by the loss of negative control of FGF23 on PTH secretion despite the higher serum levels of 1,25(OH2)D3 in the FGFR3−/− mice (P = 0.1). PTH upregulates 1α-hydroxylase and thus increases serum levels of 1,25(OH2)D3 (21), and in turn 1,25(OH2)D3 decreases PTH synthesis and secretion (14, 45), completing the feedback loop. Therefore, the high 1,25(OH2)D3 levels in FGFR3−/− mice are likely due to the higher PTH levels. However, after vehicle administration not only FGFR3−/− but also FGFR1−/− mice had elevated serum PTH levels compared with their respective controls, suggesting that FGFR3 might play a role in the negative regulation of PTH by FGF23. The role of FGFR1 in the regulation of PTH remains unclear as FGFR1 was deleted from the metanephric mesenchyme using a Pax3 promoter. It has recently been shown that Pax3-deficient embryonic mice have rudimentary parathyroid glands, and thus it is possible that FGFR1 was deleted in the parathyroid gland in our FGFR1 mice (27). The reason for the discrepancy between the baseline data and the data obtained from vehicle injection is unclear. Serum PTH levels did not change in FGFR−/− mice in response to FGF23 treatment, except a slight decrease observed in FGFR1−/− mice (P = 0.1). The fact that serum PTH remained unchanged after FGF23 administration is likely due to the fact that, on one hand, FGF23 decreases PTH secretion, but on the other hand FGF23 decreases 1,25(OH2)D3, which would stimulate PTH secretion, thus normalizing PTH levels in FGFR−/− mice as well as in their wild-type counterparts.

In vivo and in vitro studies have shown that 1,25(OH)2D3 levels are reduced by FGF23 by suppressing 1α-hydroxylase and increasing 24-hydroxylase activity (41, 51, 63, 64). 1α-Hydroxylase is the enzyme responsible for the conversion of inactive 25-(OH)2-vitamin D3 to active 1,25(OH)2D3, and it is predominantly expressed in the proximal tubule (10, 22, 25, 26, 39, 47). Irrespective of which FGFR was knocked out, FGF23 administration lowered serum 1,25(OH)2D3 levels similarly as it did in their respective control mice. It is intriguing that serum 1,25(OH)2D3 levels decreased in all the FGFR−/− mice, including FGFR1−/− mice and their respective controls, even though 1α-hydroxylase, NaPi-2a, and NaPi-2c proteins are expressed primarily in the proximal tubule. These data suggest that more than one FGFR may mediate the effect of FGF23 on vitamin D metabolism and/or that other compensatory mechanisms may be involved.

The mutation in osteoglophonic dysplasia is an activating mutation of FGFR1. The patients with osteoglophonic dysplasia have hypophosphatemia and low 1,25(OH)2D3 levels along with a skeletal phenotype including craniosynostosis, dwarfism, and nonossifying bone lesions (73). One of the patients with osteoglophonic dysplasia had high serum levels of FGF23. The cause for the high serum FGF23 level is unclear.

There is evidence that FGF23 decreases NaPi-2b expression in the small intestine, and this is dependent on an intact 1,25(OH)2D3 receptor. One of the limitations of the study is that we have not examined the effects of FGF23 on the expression of NaPi-2b in the small intestine. In addition, while we measured basal serum phosphorus and BBM NaPi-2a and NaPi-2c protein expression and the effect of FGF23 in control and FGFR null mice, we did not directly measure phosphate transport due to the limited number of animals available. The potential effects of the presence of nonrenal FGFR1 were not studied as the aim of our study was to determine the renal receptor for FGF23 that is responsible for FGF23's hypophosphatemic action.

In conclusion, this in vivo study shows that basal phosphate homeostasis is unaffected in FGFR1−/−, FGFR3−/−, and FGFR4−/− mice, indicating that FGFRs can compensate for one another in phosphate homeostasis. However, administration of recombinant FGF23 shows that FGFR1 is the predominant renal receptor for the hypophosphatemic effect of FGF23, with FGFR4 likely playing a minor role.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK-065842, DK-41612, IP30-DK-079328-01 (Core B-Physiology), and T32 DK-07257, DE-13686 (to M. Mohammadi), and a Children's Medical Center Research Foundation Grant (to J. Gattineni).

REFERENCES

- 1.Abuazza G, Becker A, Williams SS, Chakravarty S, Truong HT, Lin F, Baum M. Claudins 6, 9, and 13 are developmentally expressed renal tight junction proteins. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 291: F1132–F1141, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ADHR Consortium. Autosomal dominant hypophosphataemic rickets is associated with mutations in FGF23. Nat Genet 26: 345–348, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arman E, Haffner-Krausz R, Chen Y, Heath JK, Lonai P. Targeted disruption of fibroblast growth factor (FGF) receptor 2 suggests a role for FGF signaling in pregastrulation mammalian development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 5082–5087, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bai X, Miao D, Li J, Goltzman D, Karaplis AC. Transgenic mice overexpressing human fibroblast growth factor 23 (R176Q) delineate a putative role for parathyroid hormone in renal phosphate wasting disorders. Endocrinology 145: 5269–5279, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baum M, Dwarakanath V, Alpern RJ, Moe OW. Effects of thyroid hormone on the neonatal renal cortical Na+/H+ antiporter. Kidney Int 53: 1254–1258, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baum M, Schiavi S, Dwarakanath V, Quigley R. Effect of fibroblast growth factor-23 on phosphate transport in proximal tubules. Kidney Int 68: 1148–1153, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baum M, Syal A, Quigley R, Seikaly M. Role of prostaglandins in the pathogenesis of X-linked hypophosphatemia. Pediatr Nephrol 21: 1067–1074, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baumann K, de RC, Roinel N, Rumrich G, Ullrich KJ. Renal phosphate transport: inhomogeneity of local proximal transport rates and sodium dependence. Pflügers Arch 356: 287–298, 1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ben-Dov IZ, Galitzer H, Lavi-Moshayoff V, Goetz R, Kuro O, Mohammadi M, Sirkis R, Naveh-Many T, Silver J. The parathyroid is a target organ for FGF23 in rats. J Clin Invest 117: 4003–4008, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brunette MG, Chan M, Ferriere C, Roberts KD. Site of 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D3 synthesis in the kidney. Nature 276: 287–289, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cai Q, Hodgson SF, Kao PC, Lennon VA, Klee GG, Zinsmiester AR, Kumar R. Brief report: inhibition of renal phosphate transport by a tumor product in a patient with oncogenic osteomalacia. N Engl J Med 330: 1645–1649, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cancilla B, Davies A, Cauchi JA, Risbridger GP, Bertram JF. Fibroblast growth factor receptors and their ligands in the adult rat kidney. Kidney Int 60: 147–155, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colvin JS, Bohne BA, Harding GW, McEwen DG, Ornitz DM. Skeletal overgrowth and deafness in mice lacking fibroblast growth factor receptor 3. Nat Genet 12: 390–397, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Demay MB, Kiernan MS, DeLuca HF, Kronenberg HM. Sequences in the human parathyroid hormone gene that bind the 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptor and mediate transcriptional repression in response to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89: 8097–8101, 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deng CX, Wynshaw-Boris A, Shen MM, Daugherty C, Ornitz DM, Leder P. Murine FGFR-1 is required for early postimplantation growth and axial organization. Genes Dev 8: 3045–3057, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Du L, Desbarats M, Viel J, Glorieux FH, Cawthorn C, Ecarot B. cDNA cloning of the murine Pex gene implicated in X-linked hypophosphatemia and evidence for expression in bone. Genomics 36: 22–28, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Econs MJ, Drezner MK. Tumor-induced osteomalacia–unveiling a new hormone. N Engl J Med 330: 1679–1681, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Engleka KA, Gitler AD, Zhang M, Zhou DD, High FA, Epstein JA. Insertion of Cre into the Pax3 locus creates a new allele of Splotch and identifies unexpected Pax3 derivatives. Dev Biol 280: 396–406, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feng JQ, Ward LM, Liu S, Lu Y, Xie Y, Yuan B, Yu X, Rauch F, Davis SI, Zhang S, Rios H, Drezner MK, Quarles LD, Bonewald LF, White KE. Loss of DMP1 causes rickets and osteomalacia and identifies a role for osteocytes in mineral metabolism. Nat Genet 38: 1310–1315, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Francis F, Strom TM, Hennig S, Boddrich A, Lorenz B, Brandau O, Mohnike KL, Cagnoli M, Steffens C, Klages S, Borzym K, Pohl T, Oudet C, Econs MJ, Rowe PS, Reinhardt R, Meitinger T, Lehrach H. Genomic organization of the human PEX gene mutated in X-linked dominant hypophosphatemic rickets. Genome Res 7: 573–585, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fraser DR Regulation of the metabolism of vitamin D. Physiol Rev 60: 551–613, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fraser DR, Kodicek E. Unique biosynthesis by kidney of a biological active vitamin D metabolite. Nature 228: 764–766, 1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Givol D, Yayon A. Complexity of FGF receptors: genetic basis for structural diversity and functional specificity. FASEB J 6: 3362–3369, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goetz R, Beenken A, Ibrahimi OA, Kalinina J, Olsen SK, Eliseenkova AV, Xu C, Neubert TA, Zhang F, Linhardt RJ, Yu X, White KE, Inagaki T, Kliewer SA, Yamamoto M, Kurosu H, Ogawa Y, Kuro-o M, Lanske B, Razzaque MS, Mohammadi M. Molecular insights into the klotho-dependent, endocrine mode of action of fibroblast growth factor 19 subfamily members. Mol Cell Biol 27: 3417–3428, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gray R, Boyle I, DeLuca HF. Vitamin D metabolism: the role of kidney tissue. Science 172: 1232–1234, 1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gray RW, Omdahl JL, Ghazarian JG, DeLuca-Hydroxycholecalciferol-1-hydroxylase. Subcellular location and properties. J Biol Chem 247: 7528–7532, 1972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Griffith AV, Cardenas K, Carter C, Gordon J, Iberg A, Engleka K, Epstein JA, Manley NR, Richie ER. Increased thymus- and decreased parathyroid-fated organ domains in Splotch mutant embryos. Dev Biol 327: 216–227, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gupta N, Tarif SR, Seikaly M, Baum M. Role of glucocorticoids in the maturation of the rat renal Na+/H+ antiporter (NHE3). Kidney Int 60: 173–181, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hebert JM, Lin M, Partanen J, Rossant J, McConnell SK. FGF signaling through FGFR1 is required for olfactory bulb morphogenesis. Development 130: 1101–1111, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.HYP Consortium. A gene (PEX) with homologies to endopeptidases is mutated in patients with X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets. The HYP Consortium. Nat Genet 11: 130–136, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Inoue Y, Segawa H, Kaneko I, Yamanaka S, Kusano K, Kawakami E, Furutani J, Ito M, Kuwahata M, Saito H, Fukushima N, Kato S, Kanayama HO, Miyamoto K. Role of the vitamin D receptor in FGF23 action on phosphate metabolism. Biochem J 390: 325–331, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jaye M, Schlessinger J, Dionne CA. Fibroblast growth factor receptor tyrosine kinases: molecular analysis and signal transduction. Biochim Biophys Acta 1135: 185–199, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jonsson KB, Zahradnik R, Larsson T, White KE, Sugimoto T, Imanishi Y, Yamamoto T, Hampson G, Koshiyama H, Ljunggren O, Oba K, Yang IM, Miyauchi A, Econs MJ, Lavigne J, Juppner H. Fibroblast growth factor 23 in oncogenic osteomalacia and X-linked hypophosphatemia. N Engl J Med 348: 1656–1663, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kawahara M, Iwasaki Y, Sakaguchi K, Taguchi T, Nishiyama M, Nigawara T, Tsugita M, Kambayashi M, Suda T, Hashimoto K. Predominant role of 25OHD in the negative regulation of PTH expression: clinical relevance for hypovitaminosis D. Life Sci 82: 677–683, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krajisnik T, Bjorklund P, Marsell R, Ljunggren O, Akerstrom G, Jonsson KB, Westin G, Larsson TE. Fibroblast growth factor-23 regulates parathyroid hormone and 1alpha-hydroxylase expression in cultured bovine parathyroid cells. J Endocrinol 195: 125–131, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuro-o M Endocrine FGFs and Klothos: emerging concepts. Trends Endocrinol Metab 19: 239–245, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kurosu H, Ogawa Y, Miyoshi M, Yamamoto M, Nandi A, Rosenblatt KP, Baum MG, Schiavi S, Hu MC, Moe OW, Kuro-o M. Regulation of fibroblast growth factor-23 signaling by klotho. J Biol Chem 281: 6120–6123, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Larsson T, Marsell R, Schipani E, Ohlsson C, Ljunggren O, Tenenhouse HS, Juppner H, Jonsson KB. Transgenic mice expressing fibroblast growth factor 23 under the control of the alpha1(I) collagen promoter exhibit growth retardation, osteomalacia, and disturbed phosphate homeostasis. Endocrinology 145: 3087–3094, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lawson DE, Fraser DR, Kodicek E, Morris HR, Williams DH. Identification of 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol, a new kidney hormone controlling calcium metabolism. Nature 230: 228–230, 1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li J, Chen F, Epstein JA. Neural crest expression of Cre recombinase directed by the proximal Pax3 promoter in transgenic mice. Genesis 26: 162–164, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu S, Tang W, Zhou J, Stubbs JR, Luo Q, Pi M, Quarles LD. Fibroblast growth factor 23 is a counter-regulatory phosphaturic hormone for vitamin D. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 1305–1315, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu S, Vierthaler L, Tang W, Zhou J, Quarles LD. FGFR3 and FGFR4 do not mediate renal effects of FGF23. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 2342–2350, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu S, Zhou J, Tang W, Jiang X, Rowe DW, Quarles LD. Pathogenic role of Fgf23 in Hyp mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 291: E38–E49, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lorenz-Depiereux B, Bastepe M, et-Pages A, Amyere M, Wagenstaller J, Muller-Barth U, Badenhoop K, Kaiser SM, Rittmaster RS, Shlossberg AH, Olivares JL, Loris C, Ramos FJ, Glorieux F, Vikkula M, Juppner H, Strom TM. DMP1 mutations in autosomal recessive hypophosphatemia implicate a bone matrix protein in the regulation of phosphate homeostasis. Nat Genet 38: 1248–1250, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martin KJ, Gonzalez EA. Vitamin D analogs: actions and role in the treatment of secondary hyperparathyroidism. Semin Nephrol 24: 456–459, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mohammadi M, Olsen SK, Ibrahimi OA. Structural basis for fibroblast growth factor receptor activation. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 16: 107–137, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Norman AW, Midgett RJ, Myrtle JF, Nowicki HG. Studies on calciferol metabolism. I. Production of vitamin D metabolite 4B from 25-OH-cholecalciferol by kidney homogenates. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 42: 1082–1087, 1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Okazaki T, Igarashi T, Kronenberg HM. 5′-flanking region of the parathyroid hormone gene mediates negative regulation by 1,25-(OH)2 vitamin D3. J Biol Chem 263: 2203–2208, 1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ornitz DM, Itoh N. Fibroblast growth factors. Genome Biol 2: REVIEWS3005, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perwad F, Azam N, Zhang MY, Yamashita T, Tenenhouse HS, Portale AA. Dietary and serum phosphorus regulate fibroblast growth factor 23 expression and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D metabolism in mice. Endocrinology 146: 5358–5364, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perwad F, Zhang MY, Tenenhouse HS, Portale AA. Fibroblast growth factor 23 impairs phosphorus and vitamin D metabolism in vivo and suppresses 25-hydroxyvitamin d-1α-hydroxylase expression in vitro. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F1577–F1583, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Plotnikov AN, Hubbard SR, Schlessinger J, Mohammadi M. Crystal structures of two FGF-FGFR complexes reveal the determinants of ligand-receptor specificity. Cell 101: 413–424, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Poladia DP, Kish K, Kutay B, Hains D, Kegg H, Zhao H, Bates CM. Role of fibroblast growth factor receptors 1 and 2 in the metanephric mesenchyme. Dev Biol 291: 325–339, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Powers CJ, McLeskey SW, Wellstein A. Fibroblast growth factors, their receptors and signaling. Endocr Relat Cancer 7: 165–197, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Riminucci M, Collins MT, Fedarko NS, Cherman N, Corsi A, White KE, Waguespack S, Gupta A, Hannon T, Econs MJ, Bianco P, Gehron RP. FGF-23 in fibrous dysplasia of bone and its relationship to renal phosphate wasting. J Clin Invest 112: 683–692, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ruta M, Burgess W, Givol D, Epstein J, Neiger N, Kaplow J, Crumley G, Dionne C, Jaye M, Schlessinger J. Receptor for acidic fibroblast growth factor is related to the tyrosine kinase encoded by the fms-like gene (FLG). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 86: 8722–8726, 1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schiavi SC, Kumar R. The phosphatonin pathway: new insights in phosphate homeostasis. Kidney Int 65: 1–14, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schlessinger J Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell 103: 211–225, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schlessinger J, Plotnikov AN, Ibrahimi OA, Eliseenkova AV, Yeh BK, Yayon A, Linhardt RJ, Mohammadi M. Crystal structure of a ternary FGF-FGFR-heparin complex reveals a dual role for heparin in FGFR binding and dimerization. Mol Cell 6: 743–750, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schwindinger WF, Francomano CA, Levine MA. Identification of a mutation in the gene encoding the alpha subunit of the stimulatory G protein of adenylyl cyclase in McCune-Albright syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89: 5152–5156, 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Segawa H, Kawakami E, Kaneko I, Kuwahata M, Ito M, Kusano K, Saito H, Fukushima N, Miyamoto K. Effect of hydrolysis-resistant FGF23–R179Q on dietary phosphate regulation of the renal type-II Na/Pi transporter. Pflügers Arch 446: 585–592, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shenker A, Weinstein LS, Moran A, Pescovitz OH, Charest NJ, Boney CM, Van Wyk JJ, Merino MJ, Feuillan PP, Spiegel AM. Severe endocrine and nonendocrine manifestations of the McCune-Albright syndrome associated with activating mutations of stimulatory G protein GS. J Pediatr 123: 509–518, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shimada T, Hasegawa H, Yamazaki Y, Muto T, Hino R, Takeuchi Y, Fujita T, Nakahara K, Fukumoto S, Yamashita T. FGF-23 is a potent regulator of vitamin D metabolism and phosphate homeostasis. J Bone Miner Res 19: 429–435, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shimada T, Kakitani M, Yamazaki Y, Hasegawa H, Takeuchi Y, Fujita T, Fukumoto S, Tomizuka K, Yamashita T. Targeted ablation of Fgf23 demonstrates an essential physiological role of FGF23 in phosphate and vitamin D metabolism. J Clin Invest 113: 561–568, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shimada T, Mizutani S, Muto T, Yoneya T, Hino R, Takeda S, Takeuchi Y, Fujita T, Fukumoto S, Yamashita T. Cloning and characterization of FGF23 as a causative factor of tumor-induced osteomalacia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 6500–6505, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shimada T, Muto T, Urakawa I, Yoneya T, Yamazaki Y, Okawa K, Takeuchi Y, Fujita T, Fukumoto S, Yamashita T. Mutant FGF-23 responsible for autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets is resistant to proteolytic cleavage and causes hypophosphatemia in vivo. Endocrinology 143: 3179–3182, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shimada T, Urakawa I, Yamazaki Y, Hasegawa H, Hino R, Yoneya T, Takeuchi Y, Fujita T, Fukumoto S, Yamashita T. FGF-23 transgenic mice demonstrate hypophosphatemic rickets with reduced expression of sodium phosphate cotransporter type IIa. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 314: 409–414, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sitara D, Razzaque MS, Hesse M, Yoganathan S, Taguchi T, Erben RG, Juppner H, Lanske B. Homozygous ablation of fibroblast growth factor-23 results in hyperphosphatemia and impaired skeletogenesis, and reverses hypophosphatemia in Phex-deficient mice. Matrix Biol 23: 421–432, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ullrich KJ, Rumrich G, Kloss S. Phosphate transport in the proximal convolution of the rat kidney. I. Tubular heterogeneity, effect of parathyroid hormone in acute and chronic parathyroidectomized animals and effect of phosphate diet. Pflügers Arch 372: 269–274, 1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Urakawa I, Yamazaki Y, Shimada T, Iijima K, Hasegawa H, Okawa K, Fujita T, Fukumoto S, Yamashita T. Klotho converts canonical FGF receptor into a specific receptor for FGF23. Nature 444: 770–774, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Weinstein LS, Shenker A, Gejman PV, Merino MJ, Friedman E, Spiegel AM. Activating mutations of the stimulatory G protein in the McCune-Albright syndrome. N Engl J Med 325: 1688–1695, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Weinstein M, Xu X, Ohyama K, Deng CX. FGFR-3 and FGFR-4 function cooperatively to direct alveogenesis in the murine lung. Development 125: 3615–3623, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.White KE, Cabral JM, Davis SI, Fishburn T, Evans WE, Ichikawa S, Fields J, Yu X, Shaw NJ, McLellan NJ, McKeown C, Fitzpatrick D, Yu K, Ornitz DM, Econs MJ. Mutations that cause osteoglophonic dysplasia define novel roles for FGFR1 in bone elongation. Am J Hum Genet 76: 361–367, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.White KE, Carn G, Lorenz-Depiereux B, et-Pages A, Strom TM, Econs MJ. Autosomal-dominant hypophosphatemic rickets (ADHR) mutations stabilize FGF-23. Kidney Int 60: 2079–2086, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Xu X, Weinstein M, Li C, Naski M, Cohen RI, Ornitz DM, Leder P, Deng C. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2)-mediated reciprocal regulation loop between FGF8 and FGF10 is essential for limb induction. Development 125: 753–765, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yamaguchi TP, Harpal K, Henkemeyer M, Rossant J. fgfr-1 is required for embryonic growth and mesodermal patterning during mouse gastrulation. Genes Dev 8: 3032–3044, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yamashita T, Konishi M, Miyake A, Inui K, Itoh N. Fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-23 inhibits renal phosphate reabsorption by activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. J Biol Chem 277: 28265–28270, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yamazaki Y, Okazaki R, Shibata M, Hasegawa Y, Satoh K, Tajima T, Takeuchi Y, Fujita T, Nakahara K, Yamashita T, Fukumoto S. Increased circulatory level of biologically active full-length FGF-23 in patients with hypophosphatemic rickets/osteomalacia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87: 4957–4960, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yu X, Ibrahimi OA, Goetz R, Zhang F, Davis SI, Garringer HJ, Linhardt RJ, Ornitz DM, Mohammadi M, White KE. Analysis of the biochemical mechanisms for the endocrine actions of fibroblast growth factor-23. Endocrinology 146: 4647–4656, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhang X, Ibrahimi OA, Olsen SK, Umemori H, Mohammadi M, Ornitz DM. Receptor specificity of the fibroblast growth factor family. The complete mammalian FGF family. J Biol Chem 281: 15694–15700, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]