Abstract

Gene conversion can have a profound impact on both the short- and long-term evolution of genes and genomes. Here, we examined the gene families that are located on the X-chromosomes of human (Homo sapiens), chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes), mouse (Mus musculus) and rat (Rattus norvegicus) for evidence of gene conversion. We identified seven gene families (WD repeat protein family, Ferritin Heavy Chain family, RAS-related Protein RAB-40 family, Diphosphoinositol polyphosphate phosphohydrolase family, Transcription Elongation Factor A family, LDOC1-related family, Zinc Finger Protein ZIC, and GLI family) that show evidence of gene conversion. Through phylogenetic analyses and synteny evidence, we show that gene conversion has played an important role in the evolution of these gene families and that gene conversion has occurred independently in both primates and rodents. Comparing the results with those of two gene conversion prediction programs (GENECONV and Partimatrix), we found that both GENECONV and Partimatrix have very high false negative rates (i.e. failed to predict gene conversions), which leads to many undetected gene conversions. The combination of phylogenetic analyses with physical synteny evidence exhibits high resolution in the detection of gene conversions.

INTRODUCTION

Gene conversions are the exchange of genetic information between two genes which are initiated by a double-strand break in one gene (acceptor) followed by the repair of this gene through the copying of the sequence of a similar gene (donor). This process has important implications for the evolution of an organism. On the one hand, gene conversion between genes can lead to homogenization of these genes, thus preventing their divergence and leading to evolutionary conservation of the genes. On the other hand, gene conversion between alleles can lead to increased polymorphism and genetic diversity.

The X-chromosome (along with the Y-chromosome) plays an important role in sex determination in humans and other mammals. It contains many genes that are important for reproduction, such as genes that are testis specific (1). In addition it also contains an abundance of genes that are linked to mental development and cognitive ability (2,3) and is considered highly conserved in size, gene content and gene order (4). The X-chromosome contains a disproportionately high number of Mendelian diseases. A summary lists 168 diseases explained by 113 X-linked genes (1) and a recent search through OMIM listed 1049 inheritable disorders that originated from the X-chromosome (5). This large number is explained through the fact that males only have one X-chromosome and thus males express recessive phenotypes, which is in many cases the disease-causing phenotype.

Many occurrences of gene conversion between genes on the X-chromosome have been reported. A well-studied gene conversion is the one that occurs between OPN1LW and OPN1MW, the red and green opsin genes, respectively. These genes are located only 24 kb apart from each other and a gene conversion between the two can lead to a type of color blindness also known as blue cone monochromacy (6,7). Additionally, analysis of OPN1LW has revealed a large amount of alleles created through gene conversions on exon 3 (8). Another interesting gene conversion was discovered between the genes Pgk and Pdha (9). These genes are both located on the X-chromosome but are not tandemly arranged, as is the case with the majority of gene conversions. Instead they are in ‘widely separated chromosome locations’. The authors hypothesize the occurrence of two major recombination (i.e. gene conversion) events: one near the placental–marsupial split and one near the primate–rodent split.

Gene conversions on the X-chromosome have been shown to be linked with genetic diseases and disorders. For instance, intrachromosomal gene conversions occurring on intron 1 or 22 of the F8 gene lead to sequence inversion (10), which in turn leads to severe hemophilia A. The gene family SPANX (which consists of five genes) owes its high amount of diversity to gene conversions (11,12). This high amount of variation leads to haplotypes with an increased susceptibility to prostate cancer.

Due to the importance of the X-chromosome and the amount of important gene conversions discovered on it, we undertook a wide-scale analysis of the X-chromosome in order to identify more gene conversions. Starting with known gene families (as gene conversions typically occur between duplicated genes), we attempt to identify gene conversions through a variety of methods, including using the existing programs designed for identification of gene conversion and combining phylogenetic tree analyses with evidence of gene physical linkage. Our results show the limitations of existing software for gene conversion prediction, and the need to incorporate a variety of information to increase the resolution of gene conversion detection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We selected the human (Homo sapiens), mouse (Mus musculus), rat (Rattus norvegicus), chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) and rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) genomes for our X-chromosome gene conversion analysis. We selected these genomes because they are relatively well-studied and well-annotated. Furthermore, this set of genomes allows us to draw conclusions based on biological order, i.e. primates versus. rodents.

Gene conversions typically occur between genes that have a high level of sequence similarity and are a major mechanism of concerted evolution within gene families. Since our focus is on gene conversions between genes on the X chromosome, we started our search with gene families that are located on the X-chromosome. We used PANTHER (13), a gene family database that combines sequence similarity information with expert knowledge on protein function to cluster genes into families.

This database provides us with gene families that are similar in both function and sequence, allowing us assessment about the functional importance of any potential gene conversions. The only shortcoming with using the PANTHER database is that it only has gene families for the human, mouse and rat genomes.

After extracting only those families that have the majority of their genes on the X-chromosome, we picked those subfamilies that contained at least two genes in humans. We then used three approaches to find orthologs of these genes in other species. The first method of establishing orthology is by examining genes that are in the same subfamily in another species (this is limited to mouse and rat genes). The second method utilized listings of orthologs from Evola (14), HomoloGene (5), and Ensembl (15), which allowed us to include chimpanzee and rhesus monkey genes. The third method was through selection of genes that have the same name as those original human genes in the other species. This method was used because orthology can be obscured through concerted evolution.

The coding sequences of the gene families were aligned using the alignments of protein sequences. Pairwise distance matrices were computed using the HKY model (16). Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the neighbor-joining method with 1000 bootstraps in Phylip (17). Gene conversions were then identified by visually inspecting all the trees. Instances of genes grouped with other genes within the same species (or the same biological order) instead of with their known orthologs were marked as having gene conversions. These genes were so marked because the hypothesis is that gene conversions have kept these sequences more similar to each other within the species due to gene conservation and concerted evolution.

In order to determine that these genes are orthologs and not paralogs, we also established synteny for these genes across the species. The physical locations of these genes were retrieved from Ensembl. We included genes around and between those genes exhibiting conversions. Figures of this synteny provide visual evidence that the orthologous genes are located in the same syntenic regions across all species, thus providing evidence for their conservation across these species.

To provide additional evidence of gene conversions, we used two programs that are designed to identify genetic recombination. The first program is GENECONV which is a program specifically designed to identify gene conversions (18). It identifies highly similar sequence subsets within a set of aligned sequences and then determines their statistical significance by computing a global P-value and a local P-value. In addition, it lists data such as the length and location of these subsets (which we list as the gene conversion lengths in Tables 1 and 2). Those with low P-values (the default is <0.05) are considered to be indicative of gene conversion events. As global P-value is calculated based on consideration of all sequences in the alignments, as opposed to the pairwise P-value, which is based on consideration of only the pair of sequences of interest, global comparison is considered to be a more conservative method than pairwise (18).

Table 1.

Global GENECONV P-values

| Family | Gene 1 | Gene 2 | Sim P-value | KA P-value | GC Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTHR14754 | RN_TCEAL5 | RN_TCEAL3 | 0.0000 | 0.00000 | 313 |

| MM_Tceal5 | MM_Tceal6 | 0.0000 | 0.00000 | 244 | |

| MM_Tceal5 | MM_Tceal3 | 0.0000 | 0.00000 | 222 | |

| HS_TCEAL5 | HS_TCEAL6 | 0.0064 | 0.03491 | 130 | |

| PT_TCEAL5 | PT_TCEAL6 | 0.0065 | 0.03537 | 140 | |

| PTHR19860:SF2 | PT_WDR40C | PT_WDR40B | 0.0089 | 0.02628 | 74 |

| PTHR19818:SF18 | MM_Zxdb | MM_Zxda | 0.0000 | 0.00000 | 2107 |

| PT_ZXDB | PT_ZXDA | 0.0000 | 0.00018 | 456 | |

| HS_ZXDB | HS_ZXDA | 0.0001 | 0.00022 | 462 |

Table 2.

Pairwise GENECONV P-values

| Family | Gene 1 | Gene 2 | Sim P-value | KA P-value | GC Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTHR14754 | HS_TCEAL5 | HS_TCEAL6 | 0.0001 | 0.00063 | 130 |

| PT_TCEAL5 | PT_TCEAL6 | 0.0006 | 0.00092 | 95 | |

| HS_TCEAL6 | HS_TCEAL3 | 0.0173 | 0.03593 | 141 | |

| MM_Tceal5 | MM_Tceal3 | 0.0000 | 0.00000 | 124 | |

| MM_Tceal5 | MM_Tceal6 | 0.0000 | 0.00000 | 244 | |

| PTHR19860:SF2 | PT_WDR40C | PT_WDR40B | 0.0007 | 0.00073 | 74 |

| HS_WDR40B | HS_WDR40C | 0.0073 | 0.01019 | 55 | |

| MM_Wdr40c | MM_Wdr40b | 0.0078 | 0.01129 | 30 | |

| PTHR11708:SF146 | PT_RAB40A | PT_RAB40AL | 0.0109 | 0.02073 | 103 |

| PTHR12629 | HS_NUDT11 | HS_NUDT10 | 0.0158 | 0.09260 | 228 |

| RN_Nudt10 | RN_Nudt11 | 0.0015 | 0.24290 | 495 | |

| MM_Nudt11 | MM_Nudt10 | 0.0288 | 0.19226 | 395 | |

| PTHR15503 | MM_Cxx1c | MM_Cxx1a | 0.0420 | 0.05943 | 136 |

| MM_Cxx1c | MM_Cxx1b | 0.0364 | 0.05324 | 136 | |

| PTHR19818:SF18 | HS_ZXDB | HS_ZXDA | 0.0000 | 0.00001 | 462 |

| PT_ZXDB | PT_ZXDA | 0.0000 | 0.00000 | 456 | |

| MM_Zxdb | MM_Zxda | 0.0000 | 0.00000 | 1184 |

The second program is Partimatrix (19). Partimatrix takes a set of aligned sequences and then partitions it into subsets of one or more sequences that are equivalent to branches in a phylogenetic tree. Each partition is then given a support score for a recombination event having occurred between the sequences sharing this partition. This support score is balanced with a conflict score that indicates the uniqueness of this partition. Partitions with a high support score and low conflict score provide evidence for a gene conversion event.

RESULTS

Altogether, we identified seven gene families that exhibit signs of gene conversions. They are (using the PANTHER IDs): PTHR14754, PTHR19860:SF2, PTHR11431:SF14, PTHR11708:SF146, PTHR12629, PTHR15503 and PTHR19818:SF18. In the following sections, we show the results of gene conversion analyses for each of these families.

PTHR14754

This family is referred to as ‘Transcription Elongation Factor A’ and the protein products of these genes are involved in mRNA transcription elongation.

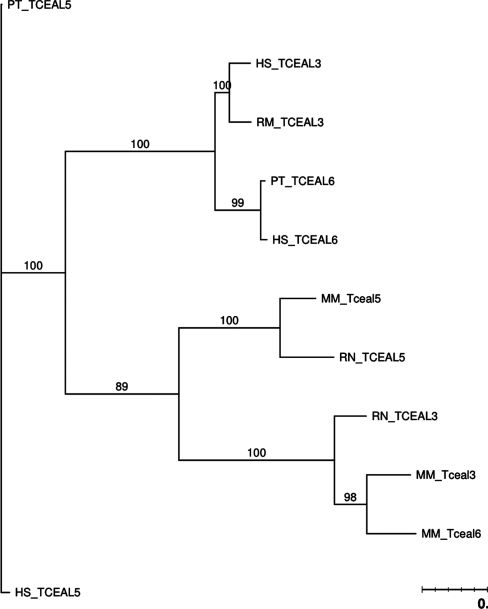

Figure 1 shows the phylogeny of the human TCEAL3, TCEAL5 and TCEAL6 genes and their orthologs across the other four species. Again, we have an example of gene conversions occurring within biological order (primates and rodents), as the mouse and rat genes are more similar to each other, and the human/chimpanzee/rhesus genes show a similar pattern. Within mouse there may even be a stronger level of gene conversion between TCEAL3 and TCEAL6; however, we were unable to identify TCEAL6 in the rat genome.

Figure 1.

PTHR14754 phylogenetic tree.

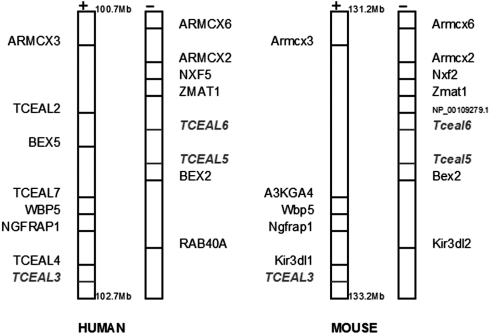

Figure 2 shows the locations of these genes together with upstream and/or downstream neighboring genes in human and mouse (other species show similar information and for brevity are not shown here). However, we can see strong evidence for gene conservation across these species in both figures.

Figure 2.

PTHR14754 synteny.

GENECONV global analysis revealed gene conversion between TCEAL3 and TCEAL5 in the rat genome, between TCEAL5 and TCEAL6 in the mouse genome, between TCEAL3 and TCEAL5 in the mouse genome, between TCEAL5 and TCEAL6 in the human genome and between TCEAL5 and TCEAL6 in the chimpanzee genome (Table 1). The length of converted regions in these gene conversions range from 140 bp to 313 bp. The GENECONV pairwise analysis shows similar results (Table 2). The primary difference is that the pairwise analysis detected an additional gene conversion between TCEAL3 and TCEAL6 in the human genome, and did not detect any conversion between TCEAL3 and TCEAL5 in the rat genome. Partimatrix analysis shows high support scores and low conflict scores for mouse TCEAL3, TCEAL5 and TCEAL6, suggesting gene conversion between these three genes in the mouse genome (Table 3). Similarly, according to the Partimatrix analysis, rat TCEAL3 and TCEAL5 and human TCEAL3 and TCEAL6 appear to have undergone gene conversion.

Table 3.

Partimatrix values

| Family | Gene combination | Support score | Conflict score |

|---|---|---|---|

| PTHR14754 | MM_Tceal5/MM_Tceal3/MM_Tceal6/RN_Tceal5/RN_Tceal3 | 59.5 | 2.53 |

| MM_Tceal5/RN_Tceal5 | 35.5 | 0.64 | |

| MM_Tceal3/MM_Tceal6/RN_Tceal3 | 35.0 | 1.60 | |

| HS_TCEAL5/PT_TCEAL5/MM_Tceal5/RN_Tceal5 | 34.5 | 3.35 | |

| HS_TCEAL5/PT_TCEAL5 | 13.0 | 0.11 | |

| HS_TCEAL6/HS_TCEAL3/PT_TCEAL6/RM_TCEAL6 | 11.5 | 0.77 | |

| PTHR19860:SF2 | MM_Wdr40C/RN_RGD1560768/MM_Wdr40b/RN_RGD1563873 | 82.5 | 2.02 |

| MM_Wdr40b/RN_RGD1563873 | 75.5 | 0.80 | |

| MM_Wdr40C/RN_RGD1560768 | 47.5 | 1.22 | |

| HS_WDR40B/PT_WDR40B | 44.5 | 0.46 | |

| HS_WDR40B/PT_WDR40B/HS_WDR40C/RM_WDR40C | 20.0 | 2.27 | |

| PTHR11431:SF14 | MM_EG436193/RN_RGD1563161 | 44.0 | 1.09 |

| MM_EG436193/RN_RGD1563161/MM_FTHL17 | 35.0 | 1.93 | |

| HS_FTHL19/RM_FTHL19 | 16.5 | 0.59 | |

| MM_EG436193/RN_RGD1563161/PT_FTHL19 | 13.0 | 3.03 | |

| MM_FTHL17/MM_EG436193 | 10.5 | 3.05 | |

| HS_FTHL17/PT_FTHL17/RM_FTHL17 | 10.0 | 0.43 | |

| PTHR11708:SF146 | HS_RAB40A/PT_RAB40A/RM_RAB40A | 21.0 | 2.28 |

| HS_RAB40A/PT_RAB40A | 7.5 | 1.40 | |

| PTHR12629 | RN_Nudt10/RN_Nudt11/MM_Nudt10/MM_Nudt11 | 53.0 | 1.05 |

| PTHR15503 | MM_Ldoc1/RN_Ldoc1/HS_LDOC1 | 23.0 | 0.95 |

| MM_Ldoc1/RN_Ldoc1/HS_LDOC1/PT_LDOC1 | 19.0 | 1.57 | |

| MM_Ldoc1/RN_Ldoc1 | 16.0 | 0.44 | |

| MM_Cxx1a/MM_Cxx1b/MM_Cxx1c/RN_LOC678880/RN_LOC679038 | 12.5 | 1.09 | |

| PTHR19818:SF18 | MM_Zxda/MM_Zxdb/RN_Zxdb | 274.5 | 1.90 |

| MM_Zxda/MM_Zxdb | 117.5 | 1.23 | |

| HS_ZXDA/PT_ZXDA | 20.0 | 1.41 | |

| HS_ZXDA/PT_ZXDA/HS_ZXDB/PT_ZXDA | 15.0 | 3.07 | |

| MM_Zxda/RN_Zxdb | 14.0 | 5.48 | |

| HS_ZXDA/PT_ZXDA/RM_ZXDA | 13.5 | 2.87 | |

| HS_ZXDB/PT_ZXDA | 10.0 | 0.18 |

PTHR19860:SF2

This family contains the human WDR40B and WDR40C genes and their orthologs across the other species. These genes are part of the WD repeat protein family and thought to be involved in a variety of cellular processes, such as cell-cycle progression, signal transduction, apoptosis and gene regulation (5).

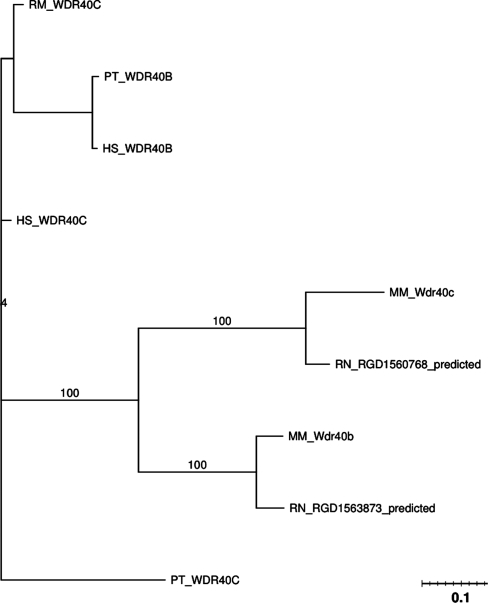

The phylogenetic tree for these genes is shown in Figure 3. The predicted rat genes are presumably the equivalent orthologs of WDR40B and WDR40C as they are within the same subfamily in PANTHER. This is further supported by the high similarity between these genes and the corresponding mouse genes. An ortholog of WDR40B was not found in the rhesus monkey. Figure 3 suggests evidence for gene conversion between biological orders. The rodents (mouse and rat) genes are more similar to each other than to their orthologs in the primates (human, chimpanzee and rhesus). This gives rise to the hypothesis that these genes have maintained similarity within their order in an effort to conserve their sequences. Evidence of gene conversion is further strongly supported by the synteny information of these genes. A figure of the synteny for this family can be seen in the Supplementary Data. All genes of interest are located on the negative strand and are spaced approximately equal distances apart.

Figure 3.

PTHR19860:SF2 phylogenetic tree.

In the global analysis, GENECONV detected a gene conversion between WDR40B and WDR40C in chimpanzees with a length of 74 bp (Table 1). The pairwise analysis of GENECONV detected gene conversions between WDR40B and WDR40C in chimpanzee, human and mouse, with gene conversion lengths of 74, 55 and 30 bp, respectively (Table 2). The Partimatrix analysis shows that the two mouse and rat genes have the highest support scores and very low conflict scores, reflecting gene conversion between the two mouse paralogous genes and the two rat paralogous genes (Table 3). The evidence of gene conversion in the human and chimpanzee genes is not as strong, as suggested by the ‘weak’ conflict and support scores in Partimatrix.

PTHR11431:SF14

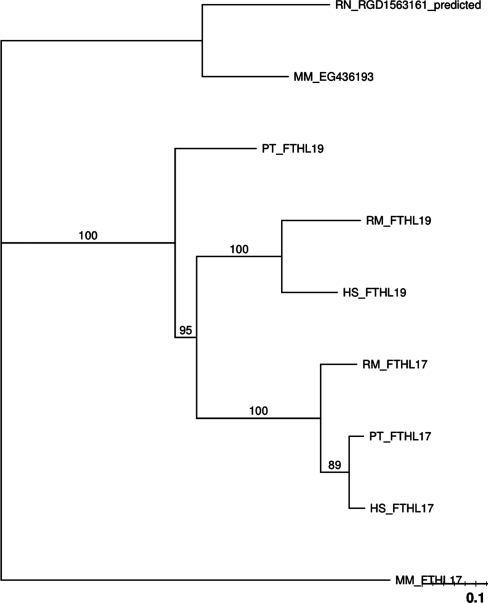

This family is also referred to as the ‘Ferritin Heavy Chain’ family and consists of multiple sequences of which FTHL17 and FTHL19 are the most well-studied members. These genes are involved in cation transport, homeostasis activities and also function as storage proteins.

In Figure 4, we can see the phylogenetic tree for this family. The FTHL17 gene is more closely related to FTHL19 in primates than it is to the mouse FTHL17 gene. This gives evidence for a gene conversion among biological order. Furthermore, the mouse gene EG436193 is part of the same subfamily and is hypothesized to be equivalent to FTHL19, giving further evidence of a gene conversion. We can see this equivalency in the synteny graph in the Supplementary Data.

Figure 4.

PTHR11431:SF14 phylogenetic tree.

GENECONV found no evidence of gene conversion using both pairwise and global analysis (Tables 1 and 2). Partimatrix analysis shows weak evidence of gene conversion between FTHL17 and FTHL19 in the mouse (Table 3).

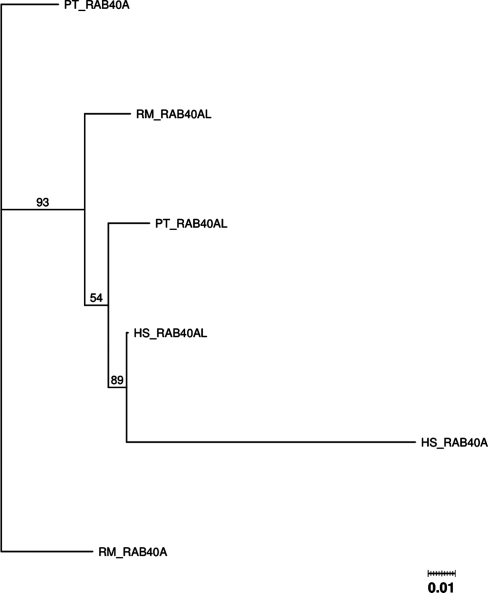

PTHR11708:SF146

This subfamily is referred to as the ‘RAS-related Protein RAB-40’ family and is part of the ‘RAS-related GTPase’ family.

Figure 5 shows the phylogenetic tree for the RAB40A and RAB40AL genes. Here, we can clearly see evidence for a gene conversion event, as the human RAB40A gene and the RAB40AL gene have a closer relation to each other than to their orthologs. In fact, it would seem that RAB40AL has donated part of its sequence to RAB40A, because the human RAB40A is located within the RAB40AL genes subtree. The detailed synteny graph of the region around these genes shown in the Supplementary Data indicates, that this is a highly conserved region where gene order has been well kept including a few other gene families such as the BEX and TCEAL genes.

Figure 5.

PTHR11708:SF146 phylogenetic tree.

GENECONV global analysis did not detect any gene conversion (Table 1). Pairwise GENECONV analysis detected a gene conversion between RAB40A and RAB40AL genes in the chimpanzee with the length of 103 bp (Table 2). Partimatrix detected no gene conversions.

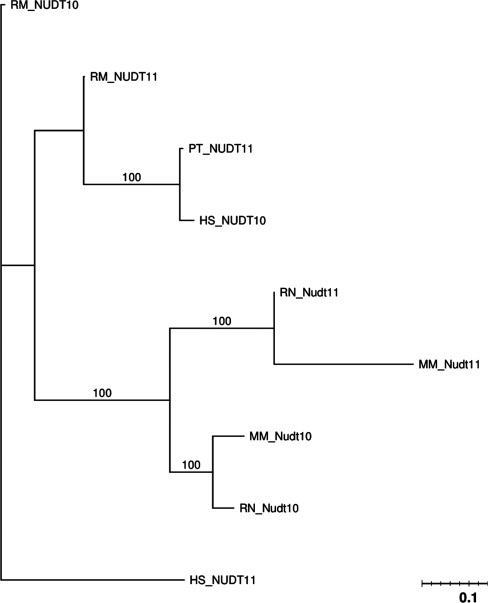

PTHR12629

Referred to as the ‘Diphosphoinositol polyphosphate phosphohydrolase’ family, genes belonging to this family create phosphotase and are involved in phospholipid metabolism. NUDT10 and NUDT11 are phosphohydrolases that preferentially attack diphosphoinositol polyphosphates (20) and are strongly expressed in testis and brain (21). These two genes are highly similar having 6 nt differences in humans (21). Due to this high similarity and their close proximity, it has been assumed that they are the result of a recent gene duplication . However, as can be seen in Figure 6, we identified orthologs in mouse and rat, leading us to speculate that this duplication occurred before the speciation event between primates and rodents, and that this high similarity is maintained between these genes by gene conversion.

Figure 6.

PTHR12629 phylogenetic tree.

Additionally, the synteny graph in the Supplementary Data indicates that an inversion event has occurred in the mouse and rat X-chromosomes at this location because the gene order in rat is similar to that of the mouse. The highly conserved synteny further supports that NUDT10 and NUDT11 arose from a duplication that predates the split of rodents and primates, and the high sequence similarity between the two genes is due to frequent gene conversion.

GENECONV global analysis detected no gene conversions. GENECONV pairwise analysis indicates that there have been gene conversions between NUDT10 and NUDT11 in the human, mouse and rat genomes of lengths 228, 495 and 395, respectively (Table 2). Partimatrix analysis reveals gene conversions between NUDT10 and NUDT11 in both the mouse and rat genomes (Table 3).

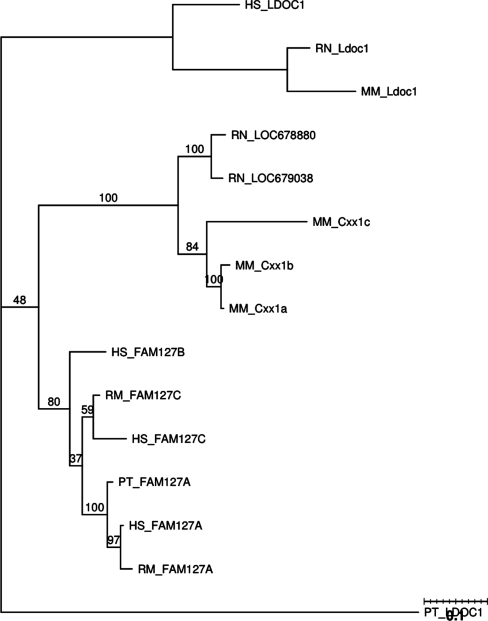

PTHR15503

This family is the ‘LDOC1 Related’ family and is involved in cell proliferation and differentiation. LDOC1 has been shown to be highly expressed in both brain and thyroid tissues, while being downregulated in cancer cell lines (22).

The phylogenetic tree for this family can be seen in Figure 7. Notably, the Cxx1 genes from mouse are considered to be homologous to the FAM127 genes of the human genome. HomoloGene lists Cxx1a/FAM127C and Cxx1c/FAM127A as orthologs. More precise homology appears to be obscured by the high sequence similarity between these genes. This is most likely to gene conversion events. Here, again we can see a clear grouping by biological order. Furthermore, the Cxx1 set of genes in the mouse genome appear highly conserved as they are grouped closer to the rat genes that were listed as belonging to this family as well. Synteny for this family can be seen in the Supplementary Data.

Figure 7.

PTHR15503 phylogenetic tree.

GENECONV global analysis detected no gene conversion (Table 1). However, GENECONV pairwise analysis indicates that there is gene conversion between Cxx1c and Cxx1a, and between Cxx1c and Cxx1b in the mouse genome (Table 2). Thus, a gene conversion seems to have occurred between Cxx1c and the two other genes, and interestingly, the converted regions appear to overlap when we look at more detailed GENECONV output. Partimatrix indicates supporting evidence for gene conversion among Cxx1c, Cxx1a and Cxx1b in mouse, and gene conversion between the two rat genes (Table 3).

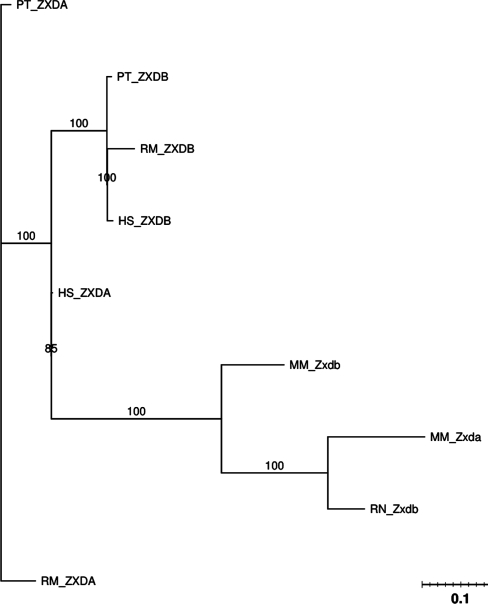

PTHR19818:SF18

This subfamily is part of the ‘Zinc Finger Protein ZIC and GLI’ family, as noted in PANTHER. Its molecular function consists of creating the zinc finger transcription factor that can regulate mRNA transcription. Two X-linked gene members of the subfamily, ZXDA and ZXDB, derive from a very ancient and highly conserved gene duplication event and are subject to X-inactivation (23).

In the phylogenetic tree in Figure 8, we can see that again we have a split by biological order. Furthermore, the genes appear to have very high similarity which is indicated by very short branch lengths. This high similarity could account for the similarity between the rat ZXDA gene and the mouse ZXDA gene. Unfortunately, we could not find a definitive rat ZXDA gene.

Figure 8.

PTHR19818:SF18 phylogenetic tree.

The synteny graph in the Supplementary Data shows the locations of ZXDA and ZXDB in the human and mouse genome. The locations of these genes are similar for all species. Furthermore, these genes are relatively isolated across all species with other genes located further downstream and upstream by relatively large margins.

GENECONV global and pairwise analyses show similar results; both identified gene conversions between ZXDA and ZXDB genes in the human, chimpanzee and mouse genomes (Tables 1 and 2). Interestingly, predicted gene conversion lengths are long, with the human and chimpanzee genome having >450 bp, and the mouse genome having >1000 bp (pairwise analysis) and 2000 bp (global detection). The results from Partimatrix are consistent with the results of GENECONV, also suggesting gene conversions in the three species (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

At its most fundamental level, gene conversion is mutagenic. The mutagenic nature of gene conversion, among the many roles that gene conversion can play, is the most neglected aspect in current research (24). Because gene conversion involves double-strand breaks and because repair of double-strand breaks can introduce nucleotide mutations (24,25), frequent gene conversion can increase the amount of DNA variation and lead to rapid rates of evolution. It has been shown that some mutation hot spots in the human genome may actually be the results of biased gene conversions rather than of adaptation (26). In the short-term, gene conversion can shape the short-range patterns of linkage disequilibrium (LD) in a genome (27). Disregarding the effect of gene conversion can lead to spurious inferences of a species population history and effective population size (28). In addition, gene conversion between recently duplicated genes can create novel haplotypes in the population (29). The process of gene conversion becomes especially important to consider in studies of human populations due to large-scale segmental duplications in the human populations (30,31).

The best known effect of gene conversion is on sequence evolution of gene families. Ample instances of gene conversion on the X-chromosome have been identified. A case of gene conversion that is relevant to the current study is the region between 100.5 Mb and 102.8 Mb. Within this region there are 20 genes (encompassing three families: BEX, WEX and GASP) that have undergone concerted evolution in humans. While the coding regions within these families are highly diverged, the 5′-UTR regions are highly conserved. A more extensive analysis of the BEX family across multiple species confirmed gene conversion in the 5′-UTR regions and suggested evidence of positive selection on these genes (32). Interestingly,our study reveals additional gene conversion activities in the region surrounding the BEX genes. RAB40AL is located 124360 bp upstream of BEX1 and RAB40A is located 188733 bp downstream of BEX2. TCEAL6 is located 10742 bp upstream of BEX5, TCEAL5 is 32482 bp upstream of BEX2 and TCEAL3 is located 296434 bp downstream of BEX2. Therefore, this large syntenic region seems to be ripe with gene conversion. These gene conversions have been ongoing independently in multiple mammalian species. Furthermore, it is interesting to note the similarity of these genes' functions and expressions in the brain. The BEX gene family is known to be highly expressed in brains, accounting for >12% of the expressed sequenced tags in the rat brain (33). The RAB40AL and RAB40A genes create a small GTPase, that regulates many intracellular processes such as cytoskeletal organization and secretion. It is also involved in biological processes, such as receptor-mediated endocytosis and general vesicle transport. Research has shown that defects in the RAB40AL gene can lead to mental retardation (34), indicating that these genes play an important role in mental development.

Our study demonstrates the effect of gene conversion on deterring the sequence divergence of duplicated genes. However, gene conversion can also promote genetic diversity, as in the case of immunoglobulin genes (35). The relative contribution that gene conversion makes to sequence diversity and conservation is not known. It is likely that, depending on the functional requirement of the genes, gene conversion can be utilized to achieve both diversity and conservation. Our recent extensive survey of literature on gene conversion (‘A Pattern Analysis of Gene Conversion Literature’, submitted for publication) indicates that among the 2478 papers, 551 of them focus on the role of gene conversion in boosting genetic diversity of genes and 402 of them on the role of gene conversion to deter divergence in certain gene families. These raw numbers seem to suggest that the two consequences are equally likely manifested in the literature. Whether this reflects the relative contribution of gene conversion to diversity and conservation in nature needs further investigation.

The balance between gene conversion and mutations is an intricate and dynamic process. Constant gene conversion can slow down the divergence of two duplicated genes. However, because frequency of gene conversion is a function of sequence identity, rates of gene conversion will, presumably, decrease as mutation erodes sequence identity and will eventually stop when the sequence identity reaches a certain threshold. It is unclear what threshold value of sequence identity is required for gene conversion. Analysis of pathogenic gene conversion events in humans suggests that at least 92% sequence identity might be required for gene conversion to occur (36). However, the identities could be the result of current detection methods which fail to identify more ancient gene conversions. To our knowledge, no theoretical studies are available to examine when the process of gene conversion will eventually stop. In our study, it is also possible that mutation rates in these genes happen to be very slow, which enables gene conversion to occur frequently and relatively recently in both primates and rodents. If this is the case, we expect that these X-chromosome orthologous genes in human and mouse should have lower sequence divergences than the autosomal orthologs that belong to the same gene family. We therefore obtained the autosomal genes for the gene families and calculated and compared the sequence identity of autosomal orthologs and X-chromosome orthologs between human and mouse. We found no suggestions of slower rate of evolution in the X-linked genes than autosome-linked genes (Table 4).

Table 4.

Sequence identities between human and mouse orthologs

| Family | X-chromosome orthologs | Percent Ident | Autosome orthologs | Percent Ident |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTHR11431:SF14 | HS_FTHL17-MM_FTHL17 | 59.2 | HS_FTH1-MM_FTH1 | 61.0 |

| HS_FTHL19-MM_FTHL19 | 51.6 | HS_FTMT-MM_Ftmt | 52.4 | |

| PTHR12629 | HS_NUDT11-MM_Nudt11 | 69.2 | HS_NUDT4-MM_Nudt4 | 45.6 |

| HS_NUDT10-MM_Nudt10 | 68.1 | HS_NUDT3-MM_Nudt3 | 45.5 | |

| PTHR15503 | HS_LDOC1-MM_Ldoc1 | 65.4 | HS_PEG10-MM_Peg10 | 54.1 |

| HS_FAM127A-MM_Cxx1c | 51.6 | HS_LDOC1L-MM_Ldoc1l | 48.6 | |

| HS_FAM127B-MM_Cxx1b | 61.5 | |||

| HS_FAM127C-MM_Cxx1a | 40.5 | |||

| PTHR19818:SF18 | HS_ZXDB-MM_Zxdb | 68.9 | HS_ZXDC-MM_Zxdc | 61.8 |

| HS_ZXDA-MM_Zxda | 32.1 | |||

| PTHR19860:SF2 | HS_WDR40B-MM_Wdr40b | 63.7 | HS_WDR40A-MM_Wdr40a | 39.1 |

| HS_WDR40C-MM_Wdr40c | 39.7 |

Confusion and errors can be caused by gene conversion. For example, in our study, there is the case of NUDT10 and NUDT11. From the synteny map and sequence information, it is clear that the annotation of the two human genes is incorrect. Furthermore, Ensembl lists two mouse genes as being NUDT11 with no NUDT10 being listed. We determined the identity of the NUDT10 gene based on the surrounding genes. In the case of TCEAL3 and TCEAL6, the highly conserved synteny map across species suggests that these genes arose before the split of primates and rodents. However, the literature considers them to be the product of a recent gene duplication. Besides the erroneous gene annotation caused by gene conversion, gene conversion can also lead to estimates of rates of gene duplication that are artificially inflated by several orders of magnitude (37).

Characterizing the process of gene conversion has been challenging. Our recent analysis of literature indicates that most studies of gene conversion mechanisms have been done on yeast (‘A Pattern Analysis of Gene Conversion Literature’, submitted for publication), due to the convenience of observing the direct product of gene conversion. Identification of gene conversion in sequence evolution is another challenging problem. Our results and methodology clearly demonstrate the difficulty. Using phylogenetic trees alone to identify gene conversion is insufficient, particularly in the case of independent gene conversions in multiple species. In this case, taking the tree literally will lead to the conclusion of independent duplications instead of multiple gene conversions in multiple species. As we know little about the relative frequencies of gene conversion and gene duplication, which likely varies from gene to gene or even species to species, it is hard to draw a definite conclusion on which scenario is more likely. Our study shows that the strongest evidence of gene conversion comes from the combination of phylogeny and synteny maps. For all the seven gene families that we examined, the well-conserved synteny maps shared between the rodents and primates offers strong evidence for the existence of regions and therein genes in the regions before the split of the two groups of species.

The current software packages are also far from sufficient, as illustrated by the results of GENECONV and Partimatrix analyses, both of which can have as high as 100% false negative rates (e.g. GENECONV finds no gene conversions in PTHR11431:SF14). Our previous study shows that GENECONV and Partimatrix are to some extent complementary in terms of sequence divergence, with GENECONV more powerful in predicting highly identical sequences and Partimatrix performing more steadily with respect to sequence divergence. However, combining the two programs' predictions together using a boosting algorithm still does not raise the accuracy significantly (38). Taken together, we believe that many incidences of gene conversion have gone undetected due to the technical difficulty in identifying these events. This might be one of the evolutionary issues that have ‘blind spots’: gene conversion has been a wide-spread and frequent process that affects the divergence of duplicated genes, yet using the existing programs to predict gene conversion in large scale may only give one ‘prominent’ gene conversion cases, while many of less ‘prominent’ gene conversion cases might go undetected.

Although largely neglected, the role of gene conversion in the evolutionary conservation of noncoding regions, has begun to emerge from recent studies. It has been shown that the 5′-UTR of the BEX gene family achieved high conservation due to gene conversions in the region (39) and that a functional motif was discovered in the region, suggesting that selection for motif conservation may keep gene conversion ongoing (39). In another example of this, a study of the RNAase noncoding regions (including 5′-UTR, intron and 3′-UTR) in leaf-eating African and Asian Colobine Monkeys has revealed a high level of homogenization through gene conversion in the regions. Gene conversion seems to be largely restricted to the noncoding regions of the gene, whereas coding regions display much higher divergence than that of noncoding regions. This has been considered to be the result of selection to prevent gene conversion in coding regions in order to keep two functionally distinct pRNase proteins in these species (40). Clearly, a complete understanding of the functional significance of gene conversion in noncoding regions calls for more studies like this one, which will benefit from the development of algorithms that identify gene conversion specifically in noncoding regions.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Funding for open access charge: NSF Grant IIS-0710945.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank David Beck for helpful comments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ross M, Grafham D, Coffey A, Scherer S, McLay K, Muzny D, Platzer M, Howell G, Burrows C, Bird C, et al. The DNA sequence of the human X chromosome. Nature. 2005;434:325–337. doi: 10.1038/nature03440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skuse D. X-linked genes and mental functioning. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005;14:R27–R32. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zechner U, Wilda M, Kehrer-Sawatzki H, Vogel W, Fundele R, Hameister H. A high density of X-linked genes for general cognitive ability: a run-away process shaping human evolution? Trends Genet. 2001;17:697–701. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(01)02446-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graves J, Koina E, Sankovi CN. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2006. How the gene content of human sex chromosomes evolved. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wheeler DL, Barrett T, Benson DA, Bryant SH, Canese K, Chetvernin V, Church DM, DiCuccio M, Edgar R, Federhen S, et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D13–D21. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reyniers E, Vanthienes M, Meire F, Boulle K, Devries K, Kestelijn P, Willems P. Gene conversion between red and defective green opsin gene in blue cone monochromacy. Genomics. 1995;29:323–328. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.9998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayashi T, Motulsky AG, Deeb SS. Position of a ‘green-red’ hybrid gene in the visual pigment array determines colour-vision phenotype. Nat. Genet. 1999;22:90–93. doi: 10.1038/8798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verrelli B, Tishkoff S. Signatures of selection and gene conversion associated with human color vision variation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004;75:363–375. doi: 10.1086/423287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fitzgerald J, Dahl H, Jakobsen I, Easteal S. Evolution of mammalian X-linked and autosomal Pgk and Pdh E1 alpha subunit genes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1996;13:1023–1031. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bagnall R, Ayres K, Green P, Giannelli F. Gene conversion and evolution of Xq28 duplicons involved in recurring inversions causing severe hemophilia a. Genome Res. 2005;15:214–223. doi: 10.1101/gr.2946205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kouprina N, Mullokandov M, Rogozin I, Collins N, Solomon G, Otstot J, Risinger J, Koonin E, Barrett J, Larionov V. The spanx gene family of cancer/testis-specific antigens: rapid evolution and amplification in African great apes and hominids. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:3077–3082. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308532100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kouprina N, Pavlicek A, Noskov V, Solomon G, Otstot J, Isaacs W, Carpten J, Trent J, Schleutker J, Barrett J, et al. Dynamic structure of the SPANX gene cluster mapped to the prostate cancer susceptibility locus HPCX at Xq27. Genome Res. 2005;15:1477–1486. doi: 10.1101/gr.4212705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mi H, Lazareva-Ulitsky B, Loo R, Kejariwal A, Vandergriff J, Rabkin S, Guo N, Muruganujan A, Doremieux O, Campbell M, et al. The panther database of protein families, subfamilies, functions and pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D284–D288. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsuya A, Sakate R, Kawahara Y, Koyanagi KO, Sato Y, Fujii Y, Yamasaki C, Habara T, Nakaoka H, Todokoro F, et al. Evola: ortholog database of all human genes in H-INvDB with manual curation of phylogenetic trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D787–D792. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flicek P, Aken BL, Beal K, Ballester B, Caccamo M, Chen Y, Clarke L, Coates G, Cunningham F, Cutts T, et al. Ensembl 2008. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D707–D714. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hasegawa M, Kishino H, Yano T. Dating of the human-ape splitting by a molecular clock of mitochondrial DNA. J. Mol. Evol. 1985;22:160–174. doi: 10.1007/BF02101694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Felsenstein J. Distributed by the author. Seattle: Department of Genome Sciences, University of Washington; 2005. Phylip (phylogeny inference package) version 3.6. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sawyer S. Statistical tests for detecting gene conversion. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1989;6:526–538. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jakobsen IB, Wilson SR, Easteal S. The partition matrix: exploring variable phylogenetic signals along nucleotide sequence alignments. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1997;14:474–484. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hidaka K, Caffrey JJ, Hua L, Zhang T, Falck JR, Nickel GC, Carrel L, Barnes LD, Shears SB. An adjacent pair of human NUDT genes on chromosome X are preferentially expressed in testis and encode two new isoforms of diphosphoinositol polyphosphate phosphohydrolase. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:32730–32738. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205476200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leslie NR, McLennan AG, Safrany ST. Cloning and characterisation of hAps1 and hAps2, human diadenosine polyphosphate-metabolising nudix hydrolases. BMC Biochem. 2002;3:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-3-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagasaki K, Manabe T, Hanzawa H, Maass N, Tsukada T, Yamaguchi K. Identification of a novel gene, LDOC1, down-regulated in cancer cell lines. Cancer Lett. 1999;140:227–234. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(99)00087-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greig GM, Sharp CB, Carrel L, Willard HF. Duplicated zinc finger protein genes on the proximal short arm of the human X chromosome: isolation, characterization and X-inactivation studies. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1993;2:1611–1618. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.10.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marais G. Biased gene conversion: implications for genome and sex evolution. Trends Genet. 2003;19:330–338. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(03)00116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Birdsell JA. Integrating genomics, bioinformatics, and classical genetics to study the effects of recombination on genome evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2002;19:1181–1197. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galtier N, Duret L. Adaptation or biased gene conversion? Extending the null hypothesis of molecular evolution. Trends Genet. 2007;23:273–277. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ardlie K, Liu-Cordero SN, Eberle MA, Daly M, Barrett J, Winchester E, Lander ES, Kruglyak L. Lower-than-expected linkage disequilibrium between tightly linked markers in humans suggests a role for gene conversion. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001;69:582–589. doi: 10.1086/323251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frisse L, Hudson RR, Bartoszewicz A, Wall JD, Donfack J, Di Rienzo A. Gene conversion and different population histories may explain the contrast between polymorphism and linkage disequilibrium levels. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001;69:831–843. doi: 10.1086/323612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lazzaro BP, Clark AG. Evidence for recurrent paralogous gene conversion and exceptional allelic divergence in the Attacin genes of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2001;159:659–671. doi: 10.1093/genetics/159.2.659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bailey JA, Gu Z, Clark RA, Reinert K, Samonte RV, Schwartz S, Adams MD, Myers EW, Li PW, Eichler EE. Recent segmental duplications in the human genome. Science. 2002;297:1003–1007. doi: 10.1126/science.1072047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang LQ, Lu HHS, Chung WY, Yang J, Li WH. Patterns of segmental duplication in the human genome. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2005;22:135–141. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang L. Adaptive evolution and frequent gene conversion in the brain expressed X-linked gene family in mammals. Biochem. Genet. 2008;46:293–311. doi: 10.1007/s10528-008-9148-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alvarez E, Zhou W, Witta SE, Freed CR. Characterization of the BEX gene family in humans, mice, and rats. Gene. 2005;357:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saito-Ohara F, Fukuda Y, Ito M, Agarwala KL, Hayashi M, Matsuo M, Imoto I, Yamakawa K, Nakamura Y, Inazawa J. The Xq22 inversion breakpoint interrupted a novel Ras-like GTpase gene in a patient with duchenne muscular dystrophy and profound mental retardation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;71:637–645. doi: 10.1086/342208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maizels N. Immunoglobulin gene diversification. Ann. Rev. Genet. 2005;39:23–46. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.073003.110544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen JM, Cooper DN, Chuzhanova N, Ferec C, Patrinos GP. Gene conversion: mechanisms, evolution and human disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2007;8:762–775. doi: 10.1038/nrg2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pan D, Zhang L. Quantifying the major mechanisms of recent gene duplications in the human and mouse genomes: a novel strategy to estimate gene duplication rates. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R158. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-8-r158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lawson MJ, Heath LS, Ramakrishnan N, Zhang L. Using cost-sensitive learning to determine gene conversions. In: Huang D-S, II DCW, Levine DS, Jo K-H, editors. ICIC (2), Vol. 5227 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 2008. pp. 1030–1038. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Winter E, Ponting C. Mammalian BEX, WEX and GASP genes: coding and non-coding chimaerism sustained by gene conversion events. BMC Evol. Biol. 2005;5 doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-5-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schienman JE, Holt RA, Auerbach MR, Stewart CB. Duplication and divergence of 2 distinct pancreatic ribonuclease genes in leaf-eating African and Asian colobine monkeys. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2006;23:1465–1479. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.