Abstract

The increased appreciation of electrical coupling between neurons has led to many studies examining the role of gap junctions in synaptic and network activity. Although the gap junctional blocker carbenoxolone (CBX) is effective in reducing electrical coupling, it may have other actions as well. To study the non–gap junctional effects of CBX on synaptic transmission, we recorded from mouse hippocampal neurons cultured on glial micro-islands. This recording configuration allowed us to stimulate and record excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) or inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs) in the same neuron or pairs of neurons. CBX irreversibly reduced evoked α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-proprionic acid (AMPA) receptor–mediated EPSCs. Consistent with a presynaptic site of action, CBX had no effect on glutamate-evoked whole cell currents and increased the paired-pulse ratio of AMPA and N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor–mediated EPSCs. CBX also reversibly reduced GABAA receptor–mediated IPSCs, increased the action potential width, and reduced the action potential firing rate. Our results indicate CBX broadly affects several neuronal membrane conductances independent of its effects on gap junctions. Thus effects of carbenoxolone on network activity cannot be interpreted as resulting from specific block of gap junctions.

INTRODUCTION

Electrical coupling can synchronize the activity of coupled neurons. Although the properties of gap junction proteins such as connexins and their expression in neurons are now well documented (Connors and Long 2004; Nagy et al. 2004), the impact of electrical coupling on neuronal ensembles or networks is still being explored. Although synchronization of membrane voltage by action potentials (Landisman et al. 2002) or subthreshold depolarizations (Long et al. 2004) can distribute and propagate concerted signals in electrically coupled networks, network activity involves a complex mixture of receptors, channels and intrinsic membrane properties. Thus elucidating the role of gap junctions and electrical coupling requires tools that reliably and specifically block gap junctions. One of the most commonly used gap junction blockers is the glycyrrhetinic acid derivative carbenoxolone (CBX). CBX eliminates electrical and gap junctional coupling in several experimental systems (Martin et al. 1991; Schoppa and Westbrook 2002; Zsiros and Maccaferri 2005). However, in our prior experiments in brain slices, CBX seemed to alter synaptic transmission independently of gap junction block (Schoppa and Westbrook 2002). Here, we examined whether CBX directly affected synaptic transmission and action potential firing by using whole cell voltage- and current-clamp recording in mouse hippocampal neurons cultured on glial micro-islands.

METHODS

Cell culture

Micro-island cultures were prepared using the method of Bekkers and Stevens (1991). Round glass coverslips (15 mm; Bellco Glass) were coated with 0.15% agarose, allowed to dry, and sprayed with a solution containing poly-d-lysine (0.1 mg/ml) and collagen (0.375 mg/ml) in 17 mM acetic acid. Hippocampi dissected from P0 to P1 mice (C57BL/6) were incubated in a papain solution (200 units; Worthington Biochemical) for 30 min (35°C), and the papain was inactivated in complete media containing bovine serum albumin (2.5 mg/ml) and trypsin inhibitor (2.5 mg/ml). The tissue was triturated with fire-polished Pasteur pipettes, and individual cells in suspension were counted using a hemocytometer. To make glial micro-islands, cells were plated at 100,000 cells per 35-mm dish (Nunc). To grow neurons on prepared glial micro-islands, cells were plated at 25,000 cells per 35-mm dish. All cultured cells were grown in 3 ml of complete media. Media contained 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Lonza). Media was replaced weekly by removing 1.5 ml of media per dish and replacing it with the same volume of freshly prepared media.

Electrophysiology

For whole cell voltage-clamp recordings, we used neurons that were 6–15 days in vitro (DIV). Micro-islands were perfused by gravity flow with extracellular solution containing (in mM) 168 NaCl2, 2.4 KCl, 10 HEPES, 10 glucose, and 1.3 CaCl2 (pH 7.4; 325 mOsm). Recording electrodes were pulled from borosilicate glass (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) and had resistances of 2.5–5 MΩ. Recording electrodes were filled with a solution containing (in mM) 140 K-gluconate, 6.23 CaCl2, 8 NaCl, 2 MgCl2, 10 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 2 Na2ATP, and 0.1 Na2GTP (pH 7.4; 320 mOsm). All recordings were at room temperature using Axopatch 1C amplifiers and AxoGraph acquisition software (AxographX, Sydney, Australia). Series resistance was always <10 MΩ and was compensated by ≥80% by the amplifier circuitry. Data were low-pass filtered at 5 kHz and acquired at 10 kHz. The membrane voltage was held at −70 mV. Brief (0.5–1 ms) depolarizations to 20 mV triggered unclamped action potentials in the axon, and evoked voltage-clamped synaptic currents in the dendrite. Neurons were stimulated at low frequency (0.1–0.133 Hz).

For current-clamp experiments, we first patched onto the neuron in voltage-clamp mode and determined whether the neuron was excitatory or inhibitory by evoking postsynaptic currents as described above. We then bathed the recorded neuron in NBQX (5 μM), d-AP5 (100 μM) or d-CPP (5–10 μM), and SR 95531 (10 μM) to block AMPA, NMDA, and GABAA receptors, respectively. For current-clamp experiments, the membrane voltage was maintained near −65 mV by small current injections (±20 pA).

CBX was solubilized in water and stored as a 50 μM stock solution at 4°C for no longer than 4 wk. For all experiments, drugs were applied via gravity-fed flowpipes positioned 50–200 μM away from recorded neurons. The flowpipes were attached to a piezo-electric bimorph for fast exchange of agonists or antagonists.

Data analysis

We used AxographX analysis software for all analyses. We measured input resistance from voltage-clamp records and repolarization potentials after the first spike. All data were compared using ANOVA or paired Student's t-test with significance set at P < 0.05. Data are reported as mean ± SE.

RESULTS

Carbenoxolone and synaptic function

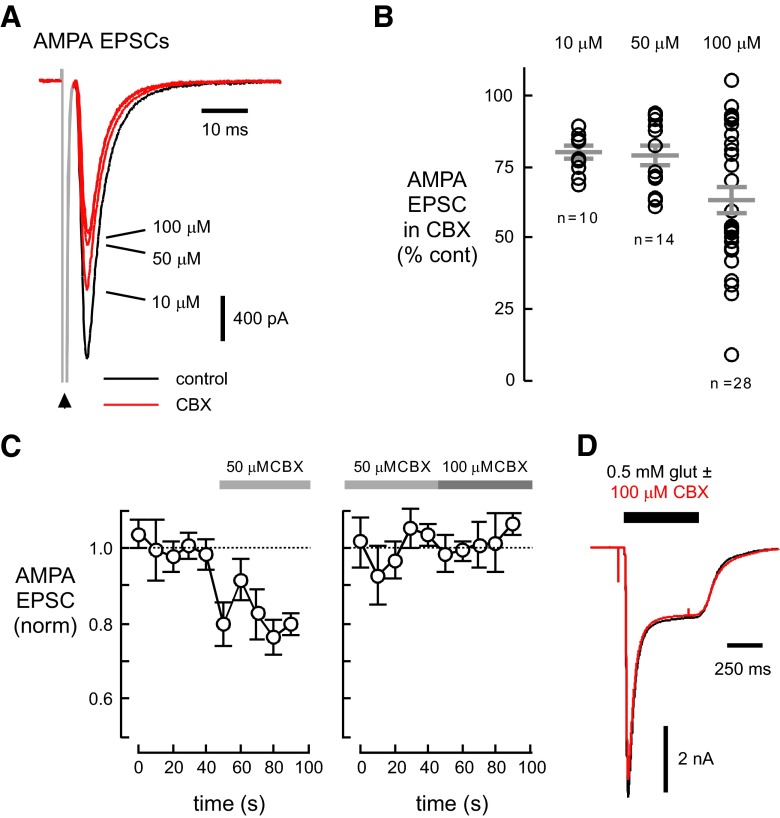

We tested CBX at concentrations (50–100 μM) commonly used to block gap junctions in brain slices (Schoppa and Westbrook 2002; Zsiros and Maccaferri 2005). CBX (100 μM) reduced AMPA receptor–mediated EPSCs to 63.3 ± 4.5% of the control amplitude (n = 28). The onset of the EPSC reduction was fast, occurring within the 7.5-s interstimulus interval (Fig. 1 C, left). Lower concentrations of CBX also reduced EPSC amplitudes (80.0 ± 2.2, n = 10 and 79.2 ± 3.3, n = 14 for 10 and 50 μM, respectively; Fig. 1, A and B). Recovery of the EPSC amplitude after removal of CBX was incomplete and thus prevented us from examining the dose-response relationship on single cells. Although 50 μM CBX was marginally less effective than 100 μM when comparing groups of cells, increasing the CBX concentration from 50 to 100 μM CBX on an individual cell did not produce further inhibition (Fig. 1C, right).

FIG. 1.

Carbenoxolone (CBX) reduces α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-proprionic acid (AMPA) receptor–mediated excitatory postsynpatic currents (EPSCs). A: In this autaptic culture, we evoked AMPA receptor mediated EPSCs by brief (0.5 ms) depolarizations of the soma. Increasing concentrations of CBX applied sequentially to a neuron reduced the EPSC. The arrowhead indicates the action current (rendered in gray). B: CBX at 100 μM produced a greater decrease in AMPA receptor–mediated EPSCs than 10 or 50 μM (ANOVA, P < 0.05). C: CBX effect occurs quickly. Once CBX was applied, reduction occurred within the 7.5-s interstimulus interval. D: CBX did not reduce whole cell currents evoked by direct application of glutamate. In A and D, black traces are control recordings; red traces indicate recordings from the same cell in the presence of the indicated concentration of CBX. Recordings were done in d-AP5 (100 μM) or d-CPP (10 μM) to block N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors.

To test whether CBX had a direct postsynaptic effect on AMPA receptors, we applied glutamate (500 μM) in the presence of 0.5 μM TTX, 10 μM SR-95531 and 100 μM d-AP5 or 5 μM d-CPP. The flowpipes used for drug applications were translated using a piezo-electric bimorph. As shown in Fig. 1D, CBX (100 μM) did not reduce whole cell glutamate–activated currents (95.7 ± 1.2% of the control amplitude, n = 5) indicating that CBX did not directly inhibit AMPA receptors.

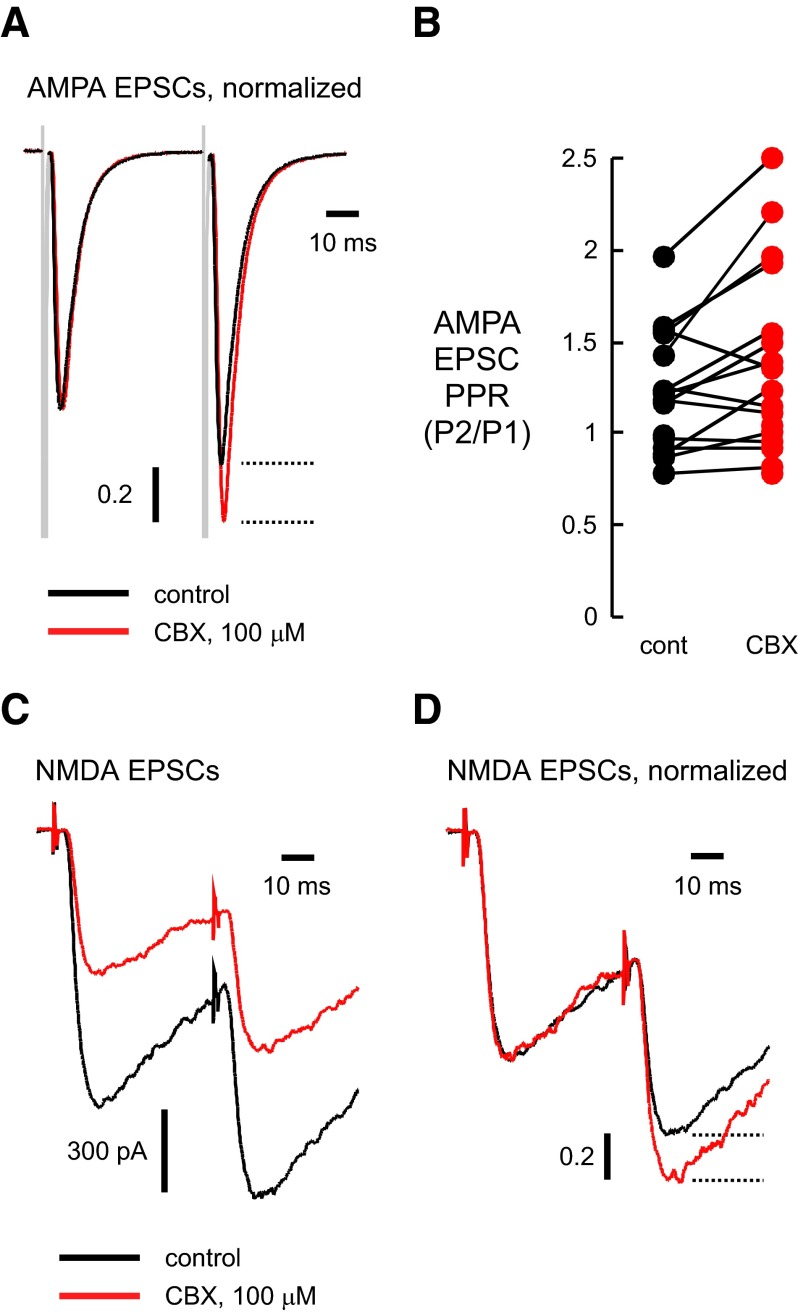

The above results suggest that the reduction of the AMPA receptor–mediated EPSC involves a presynaptic mechanism. Consistent with this possibility, CBX increased the paired-pulse ratio (PPR) of AMPA receptor–mediated EPSCs. The ratio of the second EPSC to the first (P2/P1; 50-ms interstimulus interval) was 1.38 ± 0.12 in CBX (100 μM) compared with 1.19 ± 0.08 in control (P < 0.01, n = 17; Fig. 2, A and B). 50 μM CBX also increased the AMPA PPR (0.94 ± 0.07 in control; 1.05 ± 0.06 in CBX, n = 14, P < 0.005; data not shown). As expected for a presynaptic mechanism, the extent of block of the EPSC by CBX (100 μM) correlated with its effect on the PPR (r = 0.78). However, there was no relationship between the control PPR and the extent of block (r = 0.23 for 100 μM CBX and r = 0.02 for 50 μM CBX), indicating that all the synapses were susceptible to CBX inhibition.

FIG. 2.

AMPA receptor–mediated EPSC reduction results from a presynaptic effect of CBX. We used the paired-pulse ratio (PPR) to assess the release probability. A: pairs of AMPA receptor–mediated EPSCs were stimulated at 50-ms interpulse intervals. We normalized the first EPSC of the pair to show that CBX reduced the 2nd EPSC to a lesser extent than the 1st EPSC. B: the PPR of the AMPA receptor–mediated EPSC was higher in CBX (100 μM) compared with control, consistent with a presynaptic site of action. C: NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs (in 5 μM NBQX to block AMPA receptors) were also reduced by CBX (100 μM) as shown in this recording (50-ms interstimulus interval) D: similar to AMPA receptor–mediated EPSCs, normalizing the 1st EPSC showed that the 2nd EPSC was reduced less by CBX (50-ms interstimulus interval). Dashed lines in A and D indicate the difference in amplitude of the 2nd peaks in control and CBX. Vertical scale bars in A and D indicate the amplitude fraction from the normalized EPSC of the pair. In A, C, and D, black traces are control recordings; red traces indicate recordings from the same cell in the presence of the indicated concentration of CBX.

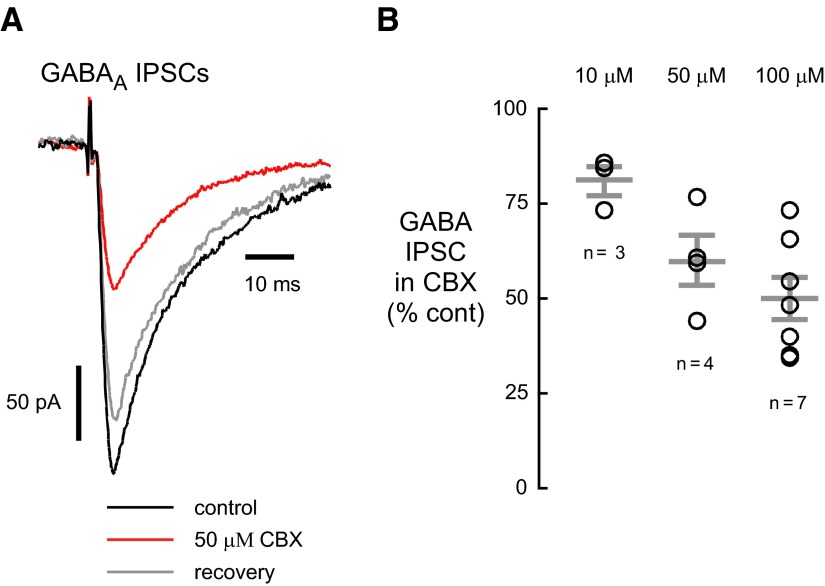

AMPA and NMDA receptors co-localize at most postsynaptic sites in central neurons (Bekkers and Stevens 1989; Jones and Baughman 1991). As predicted for a presynaptic locus of action, CBX also irreversibly reduced NMDA receptor–mediated EPSCs (Fig. 2C). In CBX (100 μM), the NMDA receptor–mediated EPSC was reduced to 69.1 ± 3.2% of control (n = 14), and PPR increased (Fig. 2D; 1.78 ± 0.13 in CBX, 1.41 ± 0.04 in control, n = 14, P < 0.01). CBX also reduced the amplitude of GABAA receptor-mediated IPSCs. In 10, 50, or 100 μM CBX, peak IPSCs were reduced by 81.2 ± 3.9 (n = 3), 60.0 ± 6.7 (n = 4), and 49.8 ± 5.7% (n = 7) of control (Fig. 3, A and B). Unlike the reduction in EPSCs, the inhibition of GABAA IPSCs was rapidly and fully reversible and did not affect the PPR (0.71 ± 0.04 for control; 0.68 ± 0.05 for 100 μM CBX, n = 7).

FIG. 3.

GABAA receptor–mediated inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs) are reduced by CBX. A: the reduction of IPSCs by CBX was reversible, as shown in this example using 50 μM CBX. B: CBX reduced GABAA IPSCs in a dose-dependent manner. Black traces are control recordings; red traces indicate recordings from the same cell in the presence of the indicated concentration of CBX.

Effects on action potentials and repetitive firing

To evoke synaptic currents, we used brief depolarizing voltage injections that triggered an unclamped action potential in the axon. In the soma, the resulting action current was followed by an evoked synaptic current (Fig. 1A). In the presence of CBX, we noticed a consistent increase in the width of the action currents. We examined this issue in greater detail by evoking action potentials in current clamp in the presence of AMPA, NMDA, and GABAA receptor antagonists.

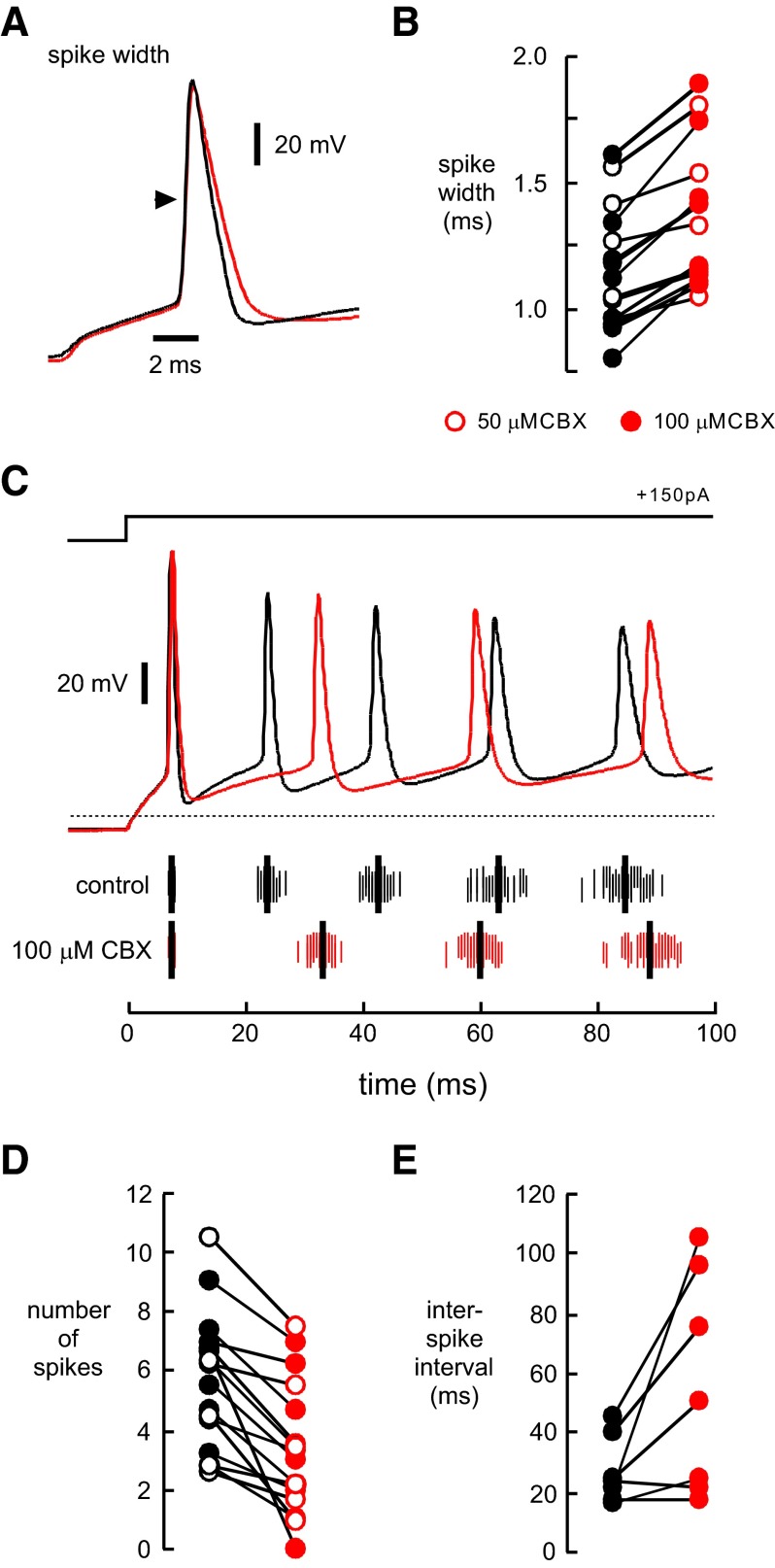

Consistent with our observations using voltage clamp, CBX increased the width of action potentials evoked by current pulses by 11.4 ± 1.9% (n = 7; P < 0.005; 50 μM) and 24.5 ± 2.9% (n = 8; P < 0.00005; 100 μM; Fig. 4, A and B). During long current injections, action potentials in control and CBX gradually accommodated (Fig. 4C). However, neurons in CBX fired fewer action potential during a 200-ms current injection. The reduction in the number of action potentials was 1.8 ± 0.48 (n = 7; P < 0.01) for 50 μM CBX and 2.6 ± 0.57 (n = 9; P < 0.01) for 100 μM CBX (Fig. 4D). In our experiments, 10 μM CBX did not affect action potential width or the number of action potentials (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 4E, the interval between the first and second spike was increased to 56.1 ± 13.8 ms in 100 μM CBX compared with 27.4 ± 4.2 ms in control (n = 7; P < 0.05). CBX at 10 or 50 μM did not affect the first interspike interval (data not shown). The maximum hyperpolarization after the first spike (repolarization potential) was 1.1 ± 0.4 mV more depolarized in CBX (100 μM) than in control (n = 8, P < 0.05). The effects on spike width and the repolarization potential are consistent with a reduction of potassium conductances that repolarize the membrane. CBX (100 μM) also decreased the resting membrane input resistance by 20.6% (134.9 ± 15.1 MΩ control compared with 107.1 ± 12.5 MΩ in CBX, n = 24; P < 0.001). Thus in excitatory hippocampal neurons, CBX affects membrane conductances that are active at the resting membrane potential as well as voltage-dependent potassium conductances involved in action potential repolarization.

FIG. 4.

CBX alters action potential firing. Current injections (200–500 ms; 50–300 pA) in whole cell current clamp resulted in trains of action potentials. The action potentials in A are averaged aligned action potentials in control and CBX (100 μM) from a single neuron. B: pairwise comparison shows that CBX (50 and 100 μM) increased the action potential width at half-height (arrowhead in A). We used only the 1st action potential in the train for analysis. C: CBX (100 μM) reduced the number of action potentials and increased the interspike interval in the 1st 200 ms of depolarizing current injection (red traces) compared with control (black traces). The mean spike times for this neuron are shown below the voltage traces by the thick black vertical hash marks, whereas the individual spike times (25 repetitions per condition) are show in thin vertical hash marks. D: a pairwise comparison shows the reduction in the number of spikes in the 1st 200 ms in CBX (50 and 100 μM) compared with control. E: CBX (100 μM) also increased the interspike interval of the 1st pair of action potentials in response to sustained current injections. Open red circles are 50 μM CBX; closed red circles are 100 μM CBX.

DISCUSSION

Our results showed that the commonly used gap junction blocker CBX has a broad range of non–gap junctional actions, including a reduction in excitatory and inhibitory synaptic currents, attenuation of membrane repolarization and spike rate, and decreases in input resistance. We focused on excitatory neurons from the mouse hippocampus, a relatively homogenous cell group. However, CBX had similar actions on GABAergic interneurons, strongly suggesting that our results are not limited to specific cell types.

We applied CBX in the same concentration range necessary to block gap junctions. CBX affected synaptic transmission at concentrations as low as 10 μM, whereas the effects on action potentials required ≥50 μM. Cultured neurons generally provide greater access to drug applications than brain slices. For example, the non–gap junctional actions of CBX occurred within a few seconds in our experiments. Equilibration is slower in brain slices, but the concentration at neuronal membranes should reach similar levels within the tens of minutes used in brain slice perfusion of drugs. CBX is membrane permeant (Monder et al. 1989) and will diffuse readily across membranes, perhaps aiding access but delaying recovery. Thus this drug cannot be reliably used to indicate a role for gap junctions in complex physiological responses such as network activity. Although CBX generally reduced excitatory transmission, the reduction in inhibitory transmission could lead under appropriate circumstances to net increases in network activity.

The molecular basis of the broad effects of CBX is not clear. CBX (18-β-glycyrrhetinic acid sodium hemisuccinate) is a water-soluble derivative of a compound from licorice root, which has a steroid-like structure (Davidson and Baumgarten 1988). Other steroid-like molecules can duplicate the effect of CBX on gap junctions (Davidson and Baumgarten 1988; Davidson et al. 1986), although neurosteroids like aldosterone (50 μM), prednisolone (100 μM), hydrocortisone (100 μM), or cholesterol (100 μM) did not block gap junctions in cultured human fibroblasts (Davidson et al. 1986). The incomplete reversibility of AMPA receptor–mediated EPSC inhibition likely reflects a large number of nonspecific membrane binding sites that slow CBX clearance. Calcium channels are the most likely presynaptic target causing the reduction in release probability in excitatory neurons. For example, CBX can block calcium channels in retinal cone photoreceptors (Vessey et al. 2004). Our results confirm and extend prior reports of gap junction–independent effects of CBX on membrane properties of hippocampal neurons (Rekling et al. 2000; Rouach et al. 2003). Although Rouach et al. (2003) saw no effect of CBX on the frequency of miniature EPSCs, our results clearly indicate that CBX can affect evoked release of glutamate. Rouach et al. (2003) reported a reversible effect of CBX on spike threshold, whereas only the block of GABAA IPSCs was completely reversible in our experiments. Our results also indicate that the actions of CBX cannot be attributed to one type of ion channel.

CBX is effective in blocking gap junctions when assessed in isolation. However, our results and those of others (Chepkova et al. 2008; Rekling et al. 2000; Rouach et al. 2003; Vessey et al. 2004) indicate that CBX acts on multiple membrane conductances and thus should not be used to assess the role of gap junctions on network activity. Given the gap junction–independent effects of CBX, studies that used CBX exclusively to infer the role of gap junctions in epileptiform activity (Gigout et al. 2006; Jahromi et al. 2002; Ross et al. 2000; Traub et al. 2001), pain (Spataro et al. 2004), cardiac pathology (Kojodjojo et al. 2006), and even synaptic transmission (Yang and Ling 2007) may need reassessment. Unfortunately other gap junction blockers also have effects on other channels (Cruikshank et al. 2004). The parent compound of CBX, glycyrrhizic acid, does not block gap junctions and thus has been used to test the specificity of CBX on network activity (Elsen et al. 2008; Rouach et al. 2003). However, glycyrrhizic acid also has non-gap junctional actions, which greatly complicates the assessment of network activity. Thus genetic ablation or dominant negative approaches (Hormuzdi et al. 2001; Placantonakis et al. 2006) should remain the standard for network studies in the absence of more specific gap junction blockers.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant NS-26494 to G. L. Westbrook.

Acknowledgments

Present address of B. J. Maher: University of Connecticut, Physiology and Neurobiology, 75 North Eagleville Rd., Rm. 175, U-3156, Storrs, CT 06268.

REFERENCES

- Bekkers and Stevens 1989.Bekkers JM, Stevens CF. NMDA and non-NMDA receptors are co-localized at individual excitatory synapses in cultured rat hippocampus. Nature 341: 230–233, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekkers and Stevens 1991.Bekkers JM, Stevens CF. Excitatory and inhibitory autaptic currents in isolated hippocampal neurons maintained in cell culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88: 7834–7838, 1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chepkova et al. 2008.Chepkova AN, Sergeeva OA, Haas HL. Carbenoxolone impairs LTP and blocks NMDA receptors in murine hippocampus. Neuropharmacology 55: 139–147, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connors and Long 2004.Connors BW, Long MA. Electrical synapses in the mammalian brain. Annu Rev Neurosci 27: 393–418, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruikshank et al. 2004.Cruikshank SJ, Hopperstad M, Younger M, Connors BW, Spray DC, Srinivas M. Potent block of CX36 and CX50 gap junction channels by mefloquine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 12364–12369, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson and Baumgarten 1988.Davidson JS, Baumgarten IM. Glycyrrhetinic acid derivatives: a novel class of inhibitors of gap-junctional intercellular communication. Structure-activity relationships. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 246: 1104–1107, 1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson et al. 1986.Davidson JS, Baumgarten IM, Harley EH. Reversible inhibition of intercellular communication by glycyrrhetinic acid. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 134: 29–36, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsen et al. 2008.Elsen FP, Shields EJ, Roe MT, Vandam RJ, Kelty JD. Carbenoxolone induced depression of rhythmogenesis in the pre-Botzinger complex. BMC Neurosci 9: 46, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gigout et al. 2006.Gigout S, Louvel J, Pumain R. Effects in vitro and in vivo of a gap junction blocker on epileptiform activities in a genetic model of absence epilepsy. Epilepsy Res 69: 15–29, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hormuzdi et al. 2001.Hormuzdi SG, Pais I, LeBeau FEN, Towers SK, Rozov A, Buhi EH, Whittington MA, Monyer H. Impaired electrical signaling disrupts gamma frequency oscillations in connexin 36-deficient mice. Neuron 31: 487–495, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahromi et al. 2002.Jahromi SS, Wentlandt K, Piran S, Carlen PL. Anticonvilsant actions of gap junctional blockers in an in vitro seizure model. J Neurophysiol 88: 1893–1902, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones and Baughman 1991.Jones KA, Baughman RW. Both NMDA and non-NMDA subtypes of glutamate receptors are concentrated at synapses on cerebral cortical neurons in culture. Neuron 7: 593–603, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojodjojo et al. 2006.Kojodjojo P, Kanagaratnam P, Segal OR, Hussain W, Peters NS. The effects of carbenoxolone on human myocardial conduction: a tool to investigate the role of gap junctional uncoupling in human arrhythmogenesis. J Am Coll Cardiol 48: 1242–1249, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landisman et al. 2002.Landisman CE, Long MA, Beierlein M, Deans MR, Paul DL, Connors BW. Electrical synapses in the thalamic reticular nucleus. J Neurosci 22: 1002–1009, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long et al. 2002.Long MA, Deans MR, Paul DL, Connors BW. Rhythmicity without synchrony in the electrically uncoupled inferior olive. J Neurosci 22: 10898–10905, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long et al. 2004.Long MA, Landisman CE, Connors BW. Small clusters of electrically coupled neurons generate synchronous rhythms in the thalamic reticular nucleus. J Neurosci 24: 341–349, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin et al. 1991.Martin W, Zempel G, Hulser D, Willecke K. Growth inhibition of oncogene-transformed rat fibroblasts by cocultured normal cells: relevance of metabolic cooperation mediated by gap junctions. Cancer Res 51: 5348–5354, 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monder et al. 1989.Monder C, Stewart PM, Lakshmi V, Valentino R, Burt D, Edwards CR. Licorice inhibits corticosteroid 11 beta-dehydrogenase of rat kidney and liver: in vivo and in vitro studies. Endocrinology 125: 1046–1053, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy et al. 2004.Nagy JI, Dudek FE, Rash JE. Update on connexins and gap junctions in neurons and glia in the mammalian nervous system. Brain Res Rev 47: 191–215, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Placantonakis et al. 2006.Placantonakis DG, Bukovsky AA, Aicher SA, Kiem HP, Welsh JP. Continuous electrical oscillations emerge from a coupled network: a study of the inferior olive using lentiviral knockdown of connexin36. J Neurosci 26: 5008–5016, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rekling et al. 2000.Rekling JC, Shao XM, Feldman JL. Electrical coupling and excitatory synaptic transmission between rhythmogenic respiratory neurons in the PreBotzinger complex. J Neurosci 20: 1–5, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross et al. 2000.Ross FM, Gwyn P, Spanswick D, Davies SN. Carbenoxolone depresses spontaneous epileptiform activity in the CA1 region of rat hippocampal slices. Neuroscience 100: 789–796, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouach et al. 2003.Rouach N, Segal M, Koulakoff A, Giaume C, Avignone E. Carbenoxolone blockade of neuronal network activity in culture is not mediated by and action on gap junctions. J Physiol 553: 729–745, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoppa and Westbrook 2002.Schoppa NE, Westbrook GL. AMPA autoreceptors drive correlated spiking in olfactory bulb glomeruli. Nat Neurosci 5: 1194–1202, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spataro et al. 2004.Spataro LE, Sloane EM, Milligan ED, Wieseler-Frank J, Schoeniger D, Jekich BM, Barrientos RM, Maier SF, Watkins LR. Spinal gap junctions: potential involvement in pain facilitation. J Pain 5: 392–405, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub et al. 2001.Traub RD, Whittington MA, Buhl EH, LeBeau FE, Bibbig A, Boyd S, Cross H, Baldeweg T. A possible role for gap junctions in generation of very fast EEG oscillations preceding the onset of, and perhaps initiating, seizures. Epilepsia 42: 153–170, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vessey et al. 2004.Vessey JP, Lalonde MR, Mizan HA, Welch NC, Kelly MEM, Barnes S. Carbenoxolone inhibition of voltage-gated Ca channels and synaptic transmission in the retina. J Neurophysiol 92: 1252–1256, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang and Ling 2007.Yang L, Ling DS. Carbenoxolone modifies spontaneous inhibitory and excitatory synaptic transmission in rat somatosensory cortex. Neurosci Lett 416: 221–226, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zsiros and Maccaferri 2005.Zsiros V, Maccaferri G. Electrical coupling between interneurons with different excitable properties in the stratum lacunosum-moleculare of the juvenile CA1 rat hippocampus. J Neurosci 25: 8686–8695, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]