Abstract

Background

Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) produce attaching/effacing (A/E) lesions on eukaryotic cells mediated by the outer membrane adhesin intimin. EPEC are sub-grouped into typical (tEPEC) and atypical (aEPEC). We have recently demonstrated that aEPEC strain 1551-2 (serotype O non-typable, non-motile) invades HeLa cells by a process dependent on the expression of intimin sub-type omicron. In this study, we evaluated whether aEPEC strains expressing other intimin sub-types are also invasive using the quantitative gentamicin protection assay. We also evaluated whether aEPEC invade differentiated intestinal T84 cells.

Results

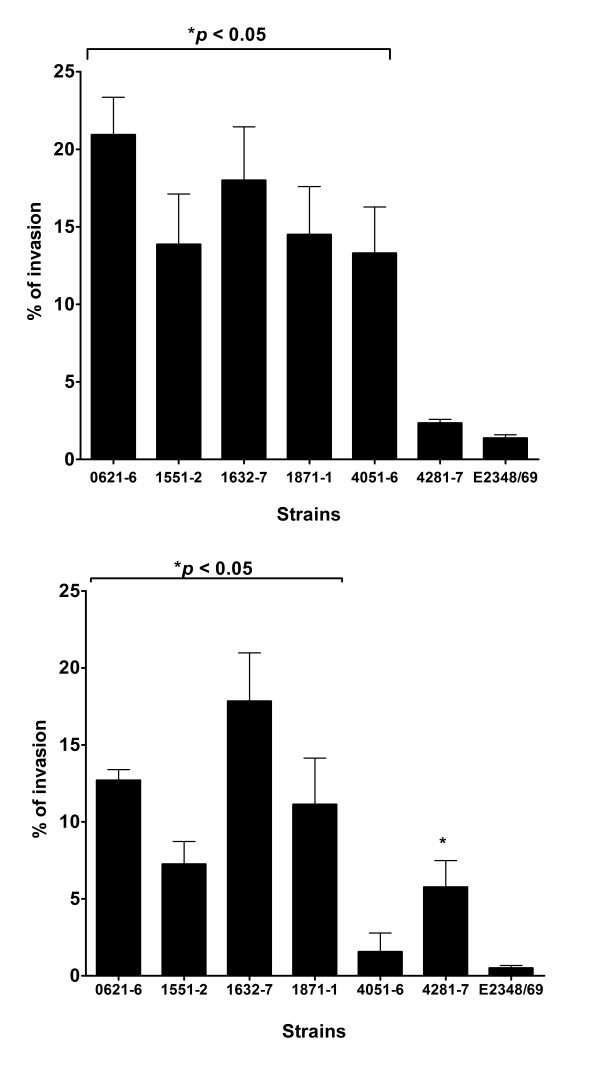

Five of six strains invaded HeLa and T84 cells in a range of 13.3%–20.9% and 5.8%–17.8%, respectively, of the total cell-associated bacteria. The strains studied were significantly more invasive than prototype tEPEC strain E2348/69 (1.4% and 0.5% in HeLa and T84 cells, respectively). Invasiveness was confirmed by transmission electron microscopy. We also showed that invasion of HeLa cells by aEPEC 1551-2 depended on actin filaments, but not on microtubules. In addition, disruption of tight junctions enhanced its invasion efficiency in T84 cells, suggesting preferential invasion via a non-differentiated surface.

Conclusion

Some aEPEC strains may invade intestinal cells in vitro with varying efficiencies and independently of the intimin sub-type.

Background

Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) are important human intestinal pathogens. This pathotype is sub-grouped into typical (tEPEC) and atypical (aEPEC) EPEC [1-3]. These sub-groups differ according to the presence of the EAF plasmid, which is found only in the former group [1,3]. Recent epidemiological studies have shown an increasing prevalence of aEPEC in both developed and developing countries [4-9].

The main characteristic of EPEC's pathogenicity is the development of a histopathologic phenotype in infected eukaryotic cells known as attaching/effacing (A/E) lesion. This lesion is also formed by enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC), another diarrheagenic E. coli pathotype whose main pathogenic mechanism is the production of Shiga toxin [10]. The A/E lesion comprises microvillus destruction and intimate bacterial adherence to enterocyte membranes, supported by a pedestal rich in actin and other cytoskeleton components [11]. The ability to produce pedestals can be identified in vitro by the fluorescence actin staining (FAS) assay that detects actin accumulation underneath adherent bacteria indicative of pedestal generation [12]. The genes involved in the establishment of A/E lesions are located in a chromosomal pathogenicity island named the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) [13]. These genes encode a group of proteins involved in the formation of a type III secretion system (T3SS), an outer membrane adhesin called intimin [14], its translocated receptor (translocated intimin receptor, Tir), chaperones and several other effector proteins that are injected into the targeted eukaryotic cell by the T3SS [15,16].

Differentiation of intimin alleles represents an important tool for EPEC and EHEC typing in routine diagnosis as well as in pathogenesis, epidemiological, clonal and immunological studies. The intimin C-terminal end is responsible for receptor binding, and it has been suggested that different intimins may be responsible for different host tissue cell tropism (reviewed in [17]). The 5' regions of eae genes are conserved, whereas the 3' regions are heterogeneous. Thus far 27 eae variants encoding 27 different intimin types and sub-types have been established: α1, α2, β1, β2 (ξR/β2B), β3, γ1, γ2, δ (δ/β2O), ε1, ε2 (νR/ε2), ε3, ε4, ε5 (ξB), ζ, η1, η2, θ, ι1, ι2 (μR/ι2), κ, λ, μB, νB, ο, π, ρ and σ [[18-26] and unpublished data].

In HeLa and HEp-2 cells, tEPEC expresses localized adherence (LA) (with compact bacterial microcolony formation) that is mediated by the Bundle Forming Pilus (BFP), which is encoded on the EAF plasmid. In contrast, most aEPEC express the LA-like pattern, which is often detected in prolonged incubation periods (with loose microcolonies) [[2], reviewed in [3]]. However, during the characterization of an aEPEC collection, Vieira et al. [27] detected 9 strains that formed characteristic LA on HeLa cells despite the absence of BFP. Further studies showed that these strains also lacked the adhesin-encoding genes of other diarrheagenic E. coli pathotypes [28]. Therefore, an exemplary strain (aEPEC 1551-2) was studied in further detail. Subsequently, it was shown that in this strain the LA pattern actually corresponded to an invasion process mediated by the interaction of the intimin sub-type omicron [29]. The clinical significance of these findings in the pathogenicity of aEPEC in vivo is currently unknown.

Despite the fact that EPEC is generally considered an extracellular pathogen, some studies have shown limited invasion of intestinal epithelium of humans and animals by tEPEC in vivo [30,31]. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that some tEPEC and aEPEC strains are able to invade distinct cellular lineages in vitro [32-36]. Due to variations in the protocols used to determine the invasion indexes, it is difficult to compare the extent of the reported invasion ability among strains of tEPEC and aEPEC pathotypes. Furthermore, in the literature there are only a few studies on the ability of aEPEC strains to invade intestinal cells [34,35]. Most tEPEC and aEPEC invasion studies have been performed on HEp-2 [32,36,37], and polarized intestinal Caco-2 cells [33,35]. Invasion studies with aEPEC and intestinal T84 cells, which are phenotypically similar to human colon epithelial cells are still lacking. Since aEPEC is a heterogeneous pathotype [3,5,28], additional analysis of the invasive ability of aEPEC strains in vitro are necessary. These data could contribute to evaluate whether the invasion capacity might be considered as an additional virulence mechanism in other aEPEC strains. Therefore, in this study, we evaluated aEPEC strains expressing intimin sub-types omicron and non-omicron regarding their ability to invade HeLa and differentiated intestinal T84 cells. The eukaryotic cell structures involved in the initial steps of entry of aEPEC 1551-2 were also examined.

Results and Discussion

Recent studies have shown that aEPEC consist of a heterogeneous group of strains, some of which could represent tEPEC strains that lost the EAF plasmid (or part of it), EHEC/STEC strains that lost stx phage sequences, or even E. coli from the normal flora that had gained the LEE region [2,27,38-40]. It remains to be elucidated whether these strains bear additional and/or specific virulence properties that are not present in tEPEC.

Recently, it has been shown that aEPEC strain 1551-2 invades HeLa cells in a process dependent on intimin omicron [29]. The aEPEC 1551-2 invasive index was about 3 folds that of tEPEC prototype strain E2348/69 tested in the same conditions. However, it is not known whether other aEPEC strains expressing intimin omicron or other intimin sub-types are also invasive. In the present study this issue was investigated.

In order to identify the intimin sub-type of four strains carrying unknown intimin sub-types, a fragment of the 3' variable region of the eae gene from the four aEPEC strains included in this study was amplified and sequenced (Table 1). Four different intimin types were identified: θ2 (theta), σ (sigma), τ (tau) and upsilon (Table 1). We have detected in aEPEC strains 4281-7 and 1632-7 (serotypes O104:H- and O26:H-, respectively) two new intimin genes eae-τ and eae-ν that showed less than 95% nucleotide sequence identity with existing intimin genes. Furthermore, a third new variant of the eae gene (theta 2 - θ2) was identified in the aEPEC strain 1871-1 (serotype O34:H-). The complete nucleotide sequences of the new eae-θ2 (FM872418), eae-τ (tau) (FM872416) and eae-upsilon; (FM872417) variant genes were determined. By using CLUSTAL W [41] for optimal sequence alignment, we determined the genetic relationship of the three new intimin genes and the remaining 27 eae variants. A genetic identity of 90% was calculated between the new eae-τ (tau) variant and eae-γ2 (gama2), eae-θ (theta) and eae-σ (sigma) genes. The eae-upsilon; showed a 94% of identity with eae-ι1. The eae-θ2 (theta-2) gene is very similar (99%) to eae-θ of Tarr & Whittam [20] and to eae-γ2 of Oswald et al. [19].

Table 1.

Characteristics of the aEPEC strains studied.

| Strain | Serotype | Intimin Type | Adherence pattern | FAS test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HeLa cells | T84 cells | ||||

| 0621-6 | ONT:H- | σ * | LA | + | + |

| 1551-2 | ONT:H- | ο | LA | + | + |

| 1632-7 | O26:H- | upsilon; ** | DA | + | + |

| 1871-1 | O34:H- | θ2 ** | LAL | + | + |

| 4051-6 | O104:H2 | ο | AA | + | + |

| 4281-7 | O104:H- | τ** | LAL | + | + |

| E2348/69 | O127:H6 | α1 | LA | + | + |

Adhesion pattern detected on HeLa cells: localized adherence (LA), localized adherence like (LAL), aggregative adherence (AA) and diffuse adherence (DA) (Vieira et al., 2001). (*) Strains that had eae gene sequenced in this study and (**) strains that carry new intimin subtypes (GenBank accession numbers: 1871-1 (FM872418); 4281-7 (FM872416) and 1632-7 (FM872417).

Quantitative assessment of bacterial invasion was performed with all strains, but different incubation-periods were used to test aEPEC strains (6 h) and tEPEC E2348/69 (3 h), because the latter colonizes more efficiently (establishes the LA pattern in 3 h) than aEPEC strains [3] and induce cell-detachment after 6 h of incubation (not shown). The quantitative gentamicin protection assay confirmed the invasive ability of aEPEC 1551-2 in HeLa cells and showed that 4 of the other 5 aEPEC strains studied were also significantly more invasive than tEPEC E2348/69 (Fig. 1A). The percentages of invasion found varied between 13.3% (SE ± 3.0) and 20.9% (SE ± 2.4), respectively, for aEPEC strains 4051-6 (intimin omicron) and 0621-6 (intimin sigma). When compared to tEPEC E2348/69 (intimin alpha 1) (1.4% ± 0.3), the invasion indexes of all strains were significantly higher (p < 0.05), except for aEPEC strain 4281-7 (intimin tau, 2.4% ± 0.3). These data confirmed that invasion of HeLa cells is not exclusively found in strains expressing intimin sub-type omicron. However, different degrees of cell invasion were observed (including strains expressing intimin omicron). Although all aEPEC strains studied were devoid of known E. coli genes supporting invasion [27], they are heterogeneous regarding the presence of additional virulence genes [5]. However, it remains to be evaluated whether the invasion ability as shown for aEPEC 1551-2 [29] of other aEPEC strains could be associated with the intimin sub-type. Furthermore, differences in invasion index could also be related to the presence of other factors, such as LEE and non-LEE effector proteins or expression of additional virulence genes. Alternatively, the affinity of both intimin and a specific Tir counterpart could influence the degree of manipulation of the cytoskeleton thus favoring less or more pronounced invasion.

Figure 1.

Invasion of epithelial cells by aEPEC and tEPEC strains. A) Percent of invasion in HeLa cells. B) Percent of invasion in T84 cells. Monolayers were infected for 6 h (aEPEC) and 3 h (tEPEC). Results of percent invasion are expressed as the percentage of cell associated bacteria that resisted killing by gentamicin and are the means ± standard error from at least three independent experiments in duplicate wells. *significantly more invasive than prototype tEPEC E2348/69 (P < 0.05 by an unpaired, two-tailed t test).

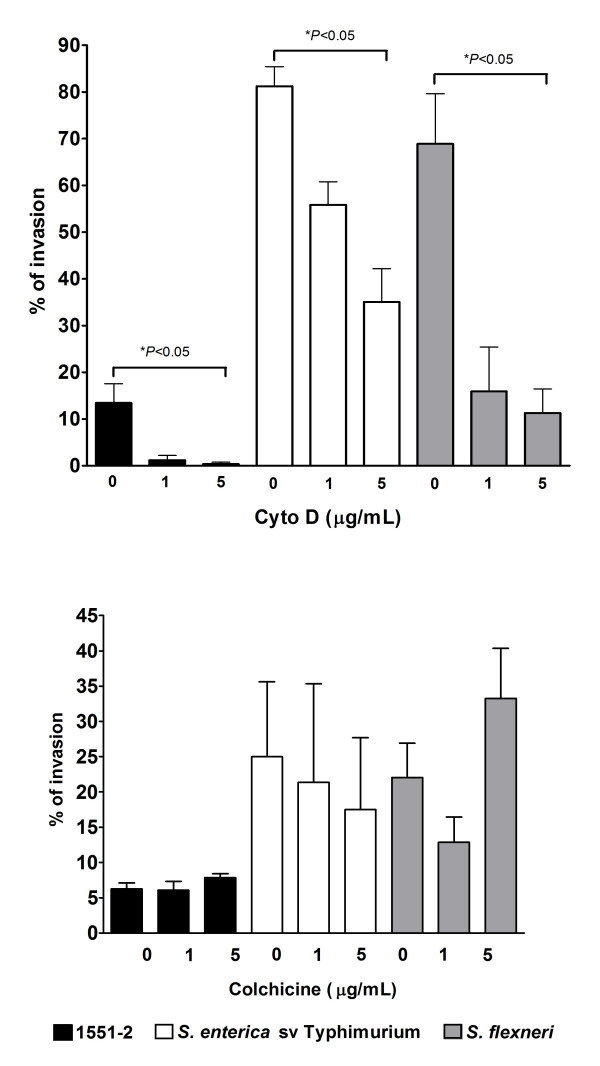

In order to identify the host cell structures and processes that might be involved in HeLa cells invasion by aEPEC 1551-2, we treated the cells with reagents affecting the cytoskeleton such as cytochalasin D (to disrupt actin microfilament formation) or colchicine (to inhibit microtubule function) prior to infection. Optical microscopy analysis revealed that treatment with cytochalasin D did not affect bacterial adhesion (data not shown). However, significantly decreased invasion by aEPEC 1551-2 (from 13.4% ± 4.1 to 1.2% ± 1.0 and 0.4% ± 0.3) was detected, as observed with the invasive S. enterica sv Typhimurium control strain (from 81.3% ± 4.2 to 55.9% ± 4.9 and 35.1% ± 7.1) and S. flexneri (from 68.9 ± 10.7 to 15.9 ± 9.5 and 11.2 ± 5.1). These results indicate that a functional host cell actin cytoskeleton is necessary for aEPEC 1551-2 uptake (Fig. 2A). In addition, this suggests that A/E lesion formation may be necessary for the invasion process since inhibition of actin polymerization resulted in both prevention of A/E lesion formation and decreased invasion. In contrast, aEPEC 1551-2 adherence (not shown) and invasion (Fig. 2B) were unaffected by colchicine cell treatment (invasion indexes of 6.2% ± 0.9 and 7.8% ± 0.6, non-treated and treated, respectively). This indicates that the microtubule network is not involved in the invasion process. As expected, S. enterica sv Typhimurium (25.0% ± 10.6 and 17.5% ± 10.2, respectively), and S. flexneri (22.1% ± 4.0 and 33.2% ± 7.1, respectively), were neither affected by treating cells with colchicine.

Figure 2.

Invasion of HeLa (epithelial) cells by aEPEC 1551-2 after treatment with cytoskeleton polymerization inhibitors. A) Cytochalasin D; B) Colchicine. Monolayers were infected for 6 h (aEPEC) and 3 h (tEPEC). S. enterica sv Typhimurium and S. flexneri were used as controls and monolayers were infected for 4 h and 6 h, respectively. Results as percent invasion are means ± standard error from at least three independent experiments performed in duplicate. * P < 0.05 by an unpaired, two-tailed t test.

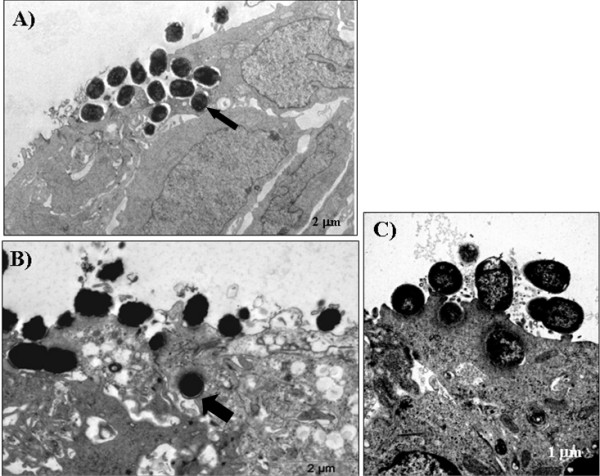

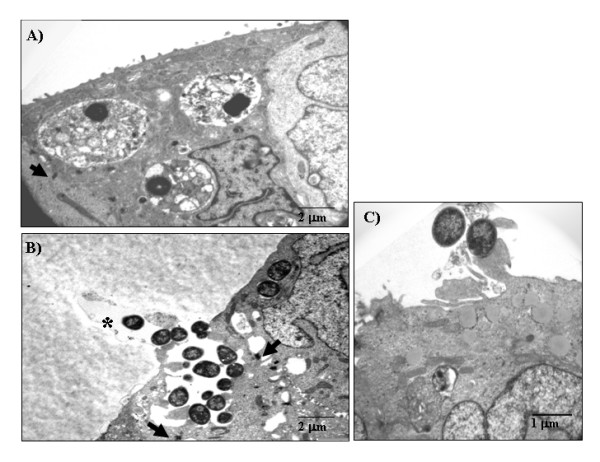

HeLa cells are derived from a human uterine cervix carcinoma. They are widely used to study bacterial interactions with epithelial cells yet they do not represent an adequate host cell type to mimic human gastrointestinal infections. To examine whether aEPEC strains would also invade intestinal epithelial cells, we infected T84 cells (derived from a colonic adenocarcinoma), cultivated for 14 days for polarization and differentiation, with all 6 aEPEC strains. The ability of these strains to promote A/E lesions in T84 cells was confirmed by FAS (Table 1). In the gentamicin protection assays performed with these cells, 5 of 6 strains were significantly more invasive than the prototype tEPEC strain E2348/69 (Fig. 1B). The exception was aEPEC 4051-6 (1.5% ± 1.2) that showed similar invasion index as tEPEC E2348/69 (0.5% ± 0.2). The invasion indexes of the 5 aEPEC strains varied from 5.8% ± 1.7 (aEPEC 4281-7) to 17.8% ± 3.1 (aEPEC 1632-7). These results demonstrate that besides invading HeLa cells, aEPEC strains carrying distinct intimin subtypes invade epithelial cells of human intestinal origin to different levels. Interestingly, the aEPEC invasion indexes were significantly higher than that of tEPEC E2348/69, but this comparison should be made with caution since the incubation-periods used were different. Nonetheless, it has already been demonstrated that tEPEC is unable to efficiently invade fully differentiated intestinal epithelial cells [42]. To confirm invasiveness, we examined T84 cells infected with aEPEC strains by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). This approach confirmed that 5 out of 6 aEPEC strains tested promoted A/E lesion formation and were also internalized (Fig. 3A and 3B). Under the conditions used, although some tEPEC E2348/69 cells were intra-cellular, most remained extra-cellular and intimately attached to the epithelial cell surface (Fig. 3C). Except for aEPEC strains 4281-7 in HeLa cells and 4051-6 in T84 cells, the remaining four strains tested were more invasive than tEPEC E2348/69 and showed heterogeneous invasion index in both HeLa and T84 cells.

Figure 3.

Transmission electron microscopy of infected polarized and differentiated T84. A) aEPEC 1551-2, B) aEPEC 0621-6 and C) prototype tEPEC E2348/69. Monolayers were infected for 6 h (aEPEC) and 3 h (tEPEC). aEPEC 1551-2 and 0621-6 were selected because, according to the data in Fig. 1B, they presented an average invasion index as compared to the other strains studied. Arrows indicate bacterial-containing vacuoles.

It has been reported that the interaction between Afa/Dr adhesins, expressed by strains of the diarrheagenic E. coli pathotype diffusely adherent E. coli (DAEC), and α5β1 integrins also results in bacterial internalization [43]. Adaptation to the intracellular environment help bacteria to avoid physical stresses (such as low pH or flow of mucosal secretions or blood) and many other host defense mechanisms including cellular exfoliation, complement deposition, antibody opsonization and subsequent recognition by macrophages or cytotoxic T cells [44]. Thus, the development of mechanisms for host cell invasion, host immune response escape, intracellular replication and/or dissemination to the neighboring cells is an important strategy for intracellular bacteria [44].

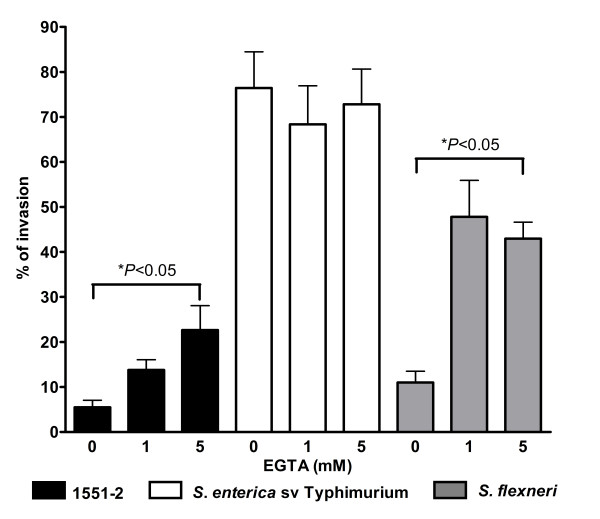

Tight junctions of polarized intestinal cells usually represent a barrier to bacterial invasion. Some studies have shown increased invasion indexes when cells are treated prior to infection with chemical agents that disrupt tight junctions and expose receptors on the basolateral side [35,45]. Similar observations have been made with bacteria infecting undifferentiated (non-polarized) eukaryotic cells [35,45]. These studies have shown a relationship between the differentiation stage of the particular host cells and the establishment of invasion [35,42,45]. Therefore, in order to examine whether aEPEC strains could also invade via the basolateral side of differentiated T84 cells, these cells were treated with different EGTA concentrations to open the epithelial tight junctions. The EGTA effect was accessed by optical microscopy (data not shown). Following this procedure, cells were infected with aEPEC 1551-2 and tEPEC E2348/69. Infections with S. enterica sv Typhimurium and S. flexneri were used as controls. This treatment promoted a significant enhancement of aEPEC 1551-2 and S. flexneri invasion, (Fig. 4) but S. enterica sv Typhimurium and tEPEC E2348/69 invasion indexes were not affected by the disruption of the epithelial cell tight junctions as was also reported previously [45].

Figure 4.

Invasion of differentiated T84 cells by aEPEC 1551-2 after tight junction disruption by EGTA treatment. Monolayers were infected for 6 h (aEPEC) and 3 h (tEPEC). S. enterica sv Typhimurium and S. flexneri were used as controls and monolayers were infected for 4 h and 6 h, respectively. Results of percent invasion are the means ± standard error from at least three independent experiments performed in duplicate. * P < 0.05 by an unpaired, two-tailed t test.

To address a putative effect of EGTA on the invasion ability of the aEPEC strains we also cultivated T84 cells for 14 days on the lower surface of a Transwell membrane. In this manner, bacterial contact with the basolateral cell surface can be achieved without prior treatment of the T84 cells. Preparations were examined by TEM and the images suggest enhanced bacterial invasion and show bacteria within vacuoles (Fig. 5) confirming the results obtained with EGTA treated T84 cells. Regarding tEPEC E2348/69, no internalized bacteria was found in the microscope fields observed. Enteropathogens may gain access to basolateral receptors and promote host cell invasion in vivo by transcytosis through M cells [46]. Alternatively, some infectious processes can cause perturbations in the intestinal epithelium, e.g., neutrophil migration during intestinal inflammation; as a consequence, a transitory destabilization in the epithelial barrier is promoted exposing the basolateral side and allowing bacterial invasion [47]. With regard to tEPEC, it has been reported that an effector molecule, EspF is involved in tight junction disruption and redistribution of occludin with ensuing increased permeability of T84 monolayers [48,49]. Whether EspF is involved in the invasion ability of the aEPEC strains studied in vivo remains to be investigated.

Figure 5.

Transmission electron microscopy of polarized and differentiated T84 cells infected via the basolateral side. A) aEPEC 1551-2. B) aEPEC 0621-6. C) prototype tEPEC E2348/69. Monolayers were infected for 6 h (aEPEC) and 3 h (tEPEC). Arrows indicate tight junction and (*) indicates a Transwell membrane pore.

In conclusion, we showed that aEPEC strains expressing distinct intimin sub-types are able to invade both HeLa and differentiated T84 cells. At least for the invasive aEPEC 1551-2 strain, HeLa cell invasion requires actin filaments but does not involve microtubules. In differentiated T84 cells, disruption of tight junctions increases the invasion capacity of aEPEC 1551-2. This observation could be significant in infantile diarrhea since in newborns and children the gastrointestinal epithelial barrier might not be fully developed [45]. As observed in uropathogenic E. coli [50], besides representing a mechanism of escape from the host immune response, invasion could also be a strategy for the establishment of persistent disease. It is possible, that the previously reported association of aEPEC with prolonged diarrhea [8] is the result of limited invasion processes. However, the in vivo relevance of our in vitro observations remains to be established. Moreover, further analyses of the fate of the intracellular bacteria such as persistence, multiplication and spreading to neighboring cells are necessary.

Conclusion

In this study we verified that aEPEC strains, carrying distinct intimin sub-types, including three new ones, may invade eukaryotic cells in vitro. HeLa cells seem to be more susceptible to aEPEC invasion than differentiated and polarized T84 cells, probably due to the absence of tight junctions in the former cell type. We also showed that actin microfilaments are required for efficient invasion of aEPEC strain 1551-2 thus suggesting that A/E lesion formation is an initial step for the invasion process of HeLa cells, while microtubules are not involved in such phenomenon. Our results also showed that tight junctions' disruption increased significantly the invasion of T84 cells by aEPEC strain 1551-2. Altogether, our findings suggest that aEPEC strains may invade intestinal cells in vitro with varying efficiencies and that the invasion process proceeds apparently independently of the intimin sub-type.

Methods

Bacterial strains and cell culture conditions

Six aEPEC strains (two carrying intimin subtype omicron and four carrying unknown intimin sub-types randomically chosen from our collection) isolated from children with diarrhea and potentially enteropathogenic due to a positive FAS assay (Table 1), and the prototype tEPEC strain E2348/69 were studied. Strains were cultured statically in Luria Bertani broth for 18 h at 37°C. Under this condition cultures reached an OD600 of 0.5–0.6. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (a gift from J.R.C. Andrade, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro) and Shigella flexneri M90T [51] were used as controls in some experiments in infection assays of 4 and 6 h, respectively. All strains were shown to be susceptible to 100 μg/mL of gentamicin prior to the invasion experiments. HeLa cells (105 cells) were cultured in Dulbecco Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% bovine fetal serum (Gibco Invitrogen) and 1% antibiotics (Gibco Invitrogen), and kept for 48 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. T84 cells (105 cells) were cultured in DMEM-F12 medium (Gibco Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% bovine fetal serum (Gibco Invitrogen), 1% non-essential amino acids (Gibco Invitrogen) and 1% antibiotics (Gibco Invitrogen), and kept for 14 days at 37°C and 5% CO2 for differentiation. For some transmission electron microscopy analysis, T84 cells (105 cells) were cultivated on the lower surface of Corning Transwell polycarbonate membrane inserts pore size 3.0 μm, membrane diameter 12 mm. In addition to apical adhesion this procedure allowed bacterial inoculation directly at the basolateral surface of the cells avoiding the use of chemical treatment to expose such surface.

Serotyping

The determination of O and H antigens was carried out by the method described by Guinée et al. [52] employing all available O (O1-O185) and H (H1-H56) antisera. All antisera were obtained and absorbed with the corresponding cross-reacting antigens to remove the nonspecific agglutinins. The O antisera were produced in the Laboratorio de Referencia de E. coli (LREC) (Lugo, Spain) and the H antisera were obtained from the Statens Serum Institut (Copenhagen, Denmark).

Typing of intimin (eae) genes

Intimin typing was performed by sequencing a fragment of the 1,125 bp from 3' variable region of the eae genes from four aEPEC strains included in this study. The complete nucleotide sequences of the new θ2 (FM872418), τ (FM872416) and ν (FM872417) variant genes were determined. The nucleotide sequence of the amplification products purified with a QIAquick DNA purification kit (Qiagen) was determined by the dideoxynucleotide triphosphate chain-termination method of Sanger, with the BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit and an ABI 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Bio-Systems). The new eae sequences of strains analyzed were deposited in the European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL Nucleotide Sequence Database).

Quantitative invasion assay

Quantitative assessment of bacterial invasion was performed as described previously [53] with modifications. Briefly, washed HeLa and polarized and differentiated T84 cells were infected with 107 colony-forming units (c.f.u.) of each aEPEC strain for 6 h or 3 h for tEPEC E2348/69. The different incubation-periods used were due to the more efficient colonization of tEPEC in comparison with the aEPEC strains; moreover, tEPEC E2348/69 induced cell-detachment in 6 h. Thereafter, cell monolayers were washed five times with PBS, and lysed in 1% Triton X-100 for 30 min at 37°C. Following cell lysis, bacteria were re-suspended in PBS and quantified by plating serial dilutions onto MacConkey agar plates to obtain the total number of cell-associated bacteria (TB). To obtain the number of intracellular bacteria (IB), a second set of infected wells was washed five times and further incubated in fresh media with 100 μg/mL of gentamicin for one hour. Following this incubation period, cells were washed five times, lysed with 1% Triton X-100 and re-suspended in PBS for quantification by plating serial dilutions. The invasion indexes were calculated as the percentage of the total number of cell-associated bacteria (TB) that was located in the intracellular compartment (IB) after 6 h (or 3 h for tEPEC E2348/69) (IBx100/TB) of infection. Assays were carried out in duplicate, and the results from at least three independent experiments were expressed as the percentage of invasion (mean ± standard error).

Cytoskeleton polymerization inhibitor

In order to evaluate the participation of cytoskeleton components in the invasion of aEPEC 1551-2, HeLa cell monolayers were incubated with 1 and 5 μg/mL of Cytochalasin-D or Colchicine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) 60 min prior to bacterial inoculation [33]. After that, cells were washed three times with PBS and the invasion assay was performed as described above. S. enterica sv Typhimurium and S. flexneri were used as controls.

EGTA treatment for tight junction disruption

In order to evaluate the interaction of aEPEC 1551-2 with the basolateral surfaces of T84 cells, differentiated cell monolayers (14 days) were incubated with 1 or 5 mM of EGTA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) 60 min prior to bacterial inoculation [35]. After that, cells were washed three times with PBS and the invasion assay was performed as describe above. S. enterica sv Typhimurium and S. flexneri were used as controls.

Detection of actin aggregation

To detect actin aggregation the Fluorescence Actin Staining (FAS) assay was performed as described previously [12]. Briefly, cell monolayers were infected for 3 h, washed three times with PBS and incubated for further 3 h with fresh medium. Subsequently, monolayers were washed five times with PBS, fixed with 3.5% paraformaldehyde, and lysed in 1% Triton X-100 for 5 min at room temperature. Monolayers were then washed three times, incubated in a dark chamber with 5 μg/mL phalloidin (20 min), and washed. Coverslips were mounted in glycerol with 0.1% para-phenylenediamine to reduce bleaching.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

T84 cells were cultured in Transwell membranes (Costar) for 14 days and infected as described above. Then they were washed 3 times (10 min each) with D-PBS (Sigma) and fixed with 2% glutaraldehyde (Serva) for 24 h at 4°C. After fixation, cells were washed 3 times with D-PBS (10 min) and post-fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide (Plano). Cells were dehydrated through a graded ethanol series (30%, 50% and 70%), then filters were cut out from the cell culture system holder and preparations were treated with ethanol (90%, 96% and 99.8%), followed by propylenoxid (100%), Epon:Propylenoxid (1:1, Serva), and Epon 100%. Afterward, filters were embedded in flat plates and kept for 2 days for polymerization. Ultrathin sections were prepared, stained with 4% uranyl acetate (Merck) and Reynold's lead citrate (Merck), and were examined with a Tecnai G2 Spirit Twin, Fei Company at 80 kV.

Alternatively, T84 cells were cultured on 35 mm diameter plates for 14 days. Infection, fixation and dehydration were performed as described above. Subsequently, the cells were examined with a LEO 906E transmission electron microscope (Zeiss, Germany) at 80 kV.

Statistical analyses

Differences in the percentages of invasion were assessed for significance by using an unpaired, two-tailed t test (GraphPad Prism 4.0).

Authors' contributions

DY and RH carried out all invasion assays and drafted this manuscript. MB, GD and AM carried out the typing of the eae gene. LG and SMC carried out transmission electron microscopies of T84 cell. JEB performed serotyping. MAS and JB contributed to the experimental design and co-wrote the manuscript with TATG. TATG supervised all research, was instrumental in experimental design, and wrote the final manuscript with DY.

This research was carried out as thesis work for a PhD (DY) in the Department of Microbiology at the Universidade Federal de São Paulo. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Denise Yamamoto, Email: dyamamoto@unifesp.br.

Rodrigo T Hernandes, Email: hernandes@unifesp.br.

Miguel Blanco, Email: miguel.blanco@usc.es.

Lilo Greune, Email: lilo@uni-muenster.de.

M Alexander Schmidt, Email: infekt@uni-muenster.de.

Sylvia M Carneiro, Email: sycarneiro@butantan.gov.br.

Ghizlane Dahbi, Email: ghizlane.dahbi@usc.es.

Jesús E Blanco, Email: jesuseulogio.blanco@usc.es.

Azucena Mora, Email: azucena.mora@usc.es.

Jorge Blanco, Email: jorge.blanco@usc.es.

Tânia AT Gomes, Email: tatg.amaral@unifesp.br.

Acknowledgements

Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP, grant 08/53812-4), and Programa de Apoio a Núcleos de Excelência – PRONEX MCT/CNPq/FAPERJ supported this work. DY received a fellowship from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq, fellowship 141708/04); DY and RTH received sandwich fellowships from Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior and Programa Brasil Alemanha (CAPES – Probral 281/07). Additional funding of this work was obtained from DAAD PPP-Brasilien (D/06/33942) and the European Network ERA-NET PathoGenoMics (Project 0313937C) and from Spanish Ministry of Health and Consumer Affairs (Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria, Spanish Network for the Research in Infectious Diseases, REIPI, RD06/0008-1018), Spanish Ministry of Education and Science (AGL-2008-02129) and the Autonomous Government of Galicia (Xunta de Galicia, PGIDIT065TAL26101P, 07MRU036261PR). A. Mora acknowledges the Ramón y Cajal programme from The Spanish Ministry of Education and Science. We also thank Dr. Cecilia Mari Abe for her help in some of the TEM procedures and J.R.C. Andrade for donating the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium control strain.

References

- Kaper JB. Defining EPEC. Rev Microbiol. 1996;27:130–133. [Google Scholar]

- Beinke C, Laarmann S, Wachter C, Karch H, Greune L, Schmidt MA. Diffuse-adhering Escherichia coli strains induce attaching-and effacing phenotypes and secrete homologues of Esp proteins. Infect Immun. 1998;66:528–539. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.528-539.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trabulsi LR, Keller R, Gomes TA. Typical and atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:508–513. doi: 10.3201/eid0805.010385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regua-Mangia AH, Gomes TA, Vieira MA, Andrade JR, Irino K, Teixeira LM. Frequency and characteristics of diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli strains isolated from children with and without diarrhea in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. J Infect. 2004;48:161–167. doi: 10.1016/S0163-4453(03)00138-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes TAT, Irino K, Girão DM, Girão VB, Vaz TM, Moreira FC, Chinarelli SH, Vieira MA. Emerging enteropathogenic Escherichia coli strains? Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:1851–1855. doi: 10.3201/eid1010.031093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MB, Nataro JP, Bernstein DI, Hawkins J, Roberts N, Staat MA. Prevalence of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli in acute childhood enteritis: a prospective controlled study. J Pediatr. 2005;146:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.08.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzolin MR, Alves RC, Keller R, Gomes TA, Beutin L, Barreto ML, Milroy C, Strina A, Ribeiro H, Trabulsi LR. Prevalence of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli in children with diarrhea in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2005;100:359–63. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762005000400004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen RN, Taylor LS, Tauschek M, Robins-Browne RM. Atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli infection and prolonged diarrhea in children. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:597–603. doi: 10.3201/eid1204.051112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo JM, Tabarelli GF, Aranda KR, Fabbricotti SH, Fagundes-Neto U, Mendes CM, Scaletsky IC. Typical enteroaggregative and atypical enteropathogenic types of Escherichia coli are the most prevalent diarrhea-associated pathotypes among Brazilian children. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:3396–3399. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00084-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karch H, Tarr PI, Bielaszewska M. Enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli in human medicine. Int J Med Microbiol. 2005;295:405–418. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon HW, Whipp SC, Argenzio RA, Levine MM, Giannella RA. Attaching and effacing activities of rabbit and human enteropathogenic Escherichia coli in pig and rabbit intestines. Infect Immun. 1983;41:1340–1351. doi: 10.1128/iai.41.3.1340-1351.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutton S, Baldwin T, Williams PH, McNeish AS. Actin accumulation at sites of bacterial adhesion to tissue culture cells: basis of a new diagnostic test for enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1290–1298. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.4.1290-1298.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel TK, Jarvis KG, Donnenberg MS, Kaper JB. A genetic locus of enterocyte effacement conserved among diverse enterobacterial pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1664–1668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerse AE, Yu J, Tall BD, Kaper JB. A genetic locus of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli necessary for the production of attaching and effacing lesions on tissue culture cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7839–7843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.20.7839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny B, DeVinney R, Stein M, Reinscheid DJ, Frey EA, Finlay BB. Enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) transfers its receptor for intimate adherence into mammalian cells. Cell. 1997;91:511–520. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80437-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel G, Phillips AD. Attaching effacing Escherichia coli and paradigms of Tir-triggered actin polymerization: getting off the pedestals. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:549–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres AG, Zhou G, Kaper JB. Adherence of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli strains to epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2005;73:18–29. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.1.18-29.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adu-Bobie J, Frankel G, Bain C, Goncalves AG, Trabulsi LR, Douce G, Knutton S, Dougan G. Detection of intimins α, β, γ, and δ, four intimin derivatives expressed by attaching and effacing microbial pathogens. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:662–668. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.3.662-668.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald E, Schmidt H, Morabito S, Karch H, Marchès O, Caprioli A. Typing of intimin genes in human and animal enterohemorrhagic and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli: characterization of a new intimin variant. Infect Immun. 2000;68:64–71. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.1.64-71.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarr CL, Whittam S. Molecular evolution of the intimin gene in O111 clones of pathogenic Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:479–487. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.2.479-487.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang WL, Köhler B, Oswald E, Beutin L, Karch H, Morabito S, Caprioli A, Suerbaum S, Schmidt H. Genetic diversity of intimin genes of attaching and effacing Escherichia coli strains. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:4486–4492. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.12.4486-4492.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido P, Blanco M, Moreno-Paz M, Briones C, Dahbi G, Blanco JE, Blanco J, Parro V. STEC-EPEC oligonucleotide microarray: a new tool for typing genetic variants of the LEE pathogenicity island of human and animal Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) and enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) strains. Clin Chem. 2006;52:192–201. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.059766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco M, Blanco JE, Mora A, Dahbi G, Alonso MP, González EA, Bernárdez MI, Blanco J. Serotypes, virulence genes and intimin types of Shiga toxin (Verotoxin)-producing Escherichia coli isolates from cattle in Spain: identification of a new intimin variant gene (eae-ξ) J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:645–651. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.2.645-651.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco M, Schumacher S, Tasara T, Zweifel C, Blanco JE, Dahbi G, Blanco J, Stephan R. Serotypes, intimin variants and other virulence factors of eae positive Escherichia coli strains isolated from healthy cattle in Switzerland. Identification of a new intimin variant gene (eae-η2) BMC Microbiol. 2005;5:23. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-5-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco M, Blanco JE, Dahbi G, Alonso MP, Mora A, Coira MA, Madrid C, Juárez A, Bernárdez MI, González EA, Blanco J. Identification of two new intimin types in atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Int Microbiol. 2006;9:103–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco M, Blanco JE, Dahbi G, Mora A, Alonso MP, Varela G, Gadea MP, Schelotto F, Gonzalez EA, Blanco J. Typing of intimin (eae) genes from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) isolated from children with diarrhea in Montevideo, Uruguay: identification of two novel intimin variants (μB and ξR/β2B) J Med Microbiol. 2006;55:1165–1174. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46518-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira MA, Andrade JR, Trabulsi LR, Rosa AC, Dias AM, Ramos SR, Frankel G, Gomes TA. Phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of Escherichia coli strains of non-enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) serogroups that carry EAE and lack the EPEC adherence factor and Shiga toxin DNA probe sequences. J Infect Dis. 2001;5:762–772. doi: 10.1086/318821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandes RT, Vieira MAM, Carneiro SM, Salvador FA, Gomes TAT. Characterization of atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli strains that express typical localized adherence in HeLa cells in the absence of the bundle-forming pilus. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:4214–4217. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01022-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandes RT, Silva RM, Carneiro SM, Salvador FA, Fernandes MC, Padovan AC, Yamamoto D, Mortara RA, Elias WP, da Silva Briones MR, Gomes TA. The localized adherence pattern of an atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli is mediated by intimin omicron and unexpectedly promotes HeLa cell invasion. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:415–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polotsky YE, Dragunskaya EM, Seliverstova VG, Avdeeva TA, Chakhutinskaya MG, Kétyi I, Vertényl A, Ralovich B, Emödy L, Málovics I, Safonova NV, Snigirevskaya ES, Karyagina EI. Pathogenic effect of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli and Escherichia coli causing infantile diarrhoea. Acta Microbiol Acad Sci Hung. 1977;24:221–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzipori S, Robins-Browne RM, Gonis G, Hayes J, Withers M, McCartney E. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli enteritis: evaluation of the gnotobiotic piglet as a model of human infection. Gut. 1985;26:570–578. doi: 10.1136/gut.26.6.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnenberg MS, Donohue-Rolfe A, Keusch GT. Epithelial cell invasion: an overlooked property of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) associated with the EPEC adherence factor. J Infect Dis. 1989;160:452–459. doi: 10.1093/infdis/160.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis CL, Jerse AE, Kaper JB, Falkow S. Characterization of interactions of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli O127:H6 with mammalian cells in vitro. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:693–703. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.4.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaletsky IC, Pedroso MZ, Fagundes-Neto U. Attaching and effacing enteropathogenic Escherichia coli O18ab invades epithelial cells and causes persistent diarrhea. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4876–4881. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4876-4881.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa AC, Vieira MA, Tibana A, Gomes TA, Andrade JR. Interactions of Escherichia coli strains of non-EPEC serogroups that carry eae and lack the EAF and stx gene sequences with undifferentiated and differentiated intestinal human Caco-2 cells. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2001;200:117–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins-Browne RM, Bordun AM, Tauschek M, Bennett-Wood VR, Russell J, Oppedisano F, Lister NA, Bettelheim KA, Fairley CK, Sinclair MI, Hellard ME. Escherichia coli and community-acquired gastroenteritis, Melbourne, Australia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:1797–1805. doi: 10.3201/eid1010.031086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel G, Philips AD, Novakova M, Batchelor M, Hicks S, Dougan G. Generation of Escherichia coli intimin derivatives with differing biological activities using site-directed mutagenesis of the intimin C-terminus domain. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:559–570. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller D, Greune L, Heusipp G, Karch H, Fruth A, Tschäpe H, Schmidt MA. Identification of unconventional intestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli expressing intermediate virulence factor profiles with a novel single step multiplex PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:3380–3390. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02855-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afset JE, Anderssen E, Bruant G, Harel J, Wieler L, Bergh K. Phylogenetic backgrounds and virulence profiles of atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli strains from a case-control study using multilocus sequence typing and DNA microarray analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:2280–2290. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01752-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielaszewska M, Middendorf B, Köck R, Friedrich AW, Fruth A, Karch H, Schmidt MA, Mellmann A. Shiga toxin-negative attaching and effacing Escherichia coli: distinct clinical associations with bacterial phylogeny and virulence traits and inferred in-host pathogen evolution. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:208–217. doi: 10.1086/589245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabastou JM, Kernéis S, Bernet-Camard MF, Barbat A, Coconnier MH, Kaper JB, Servin AL. Two stages of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli intestinal pathogenicity are up and down-regulated by the epithelial cell differentiation. Differentiation. 1995;59:127–134. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.1995.5920127.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plancon L, Du Merle L, Le Friec S, Gounon P, Jouve M, Guignot J, Servin A, Le Bouguenec C. Recognition of the cellular beta1-chain integrin by the bacterial AfaD invasin is implicated in the internalization of afa-expressing pathogenic Escherichia coli strains. Cell Microbiol. 2003;5:681–693. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizarro-Cerdá J, Cossart P. Bacterial adhesion and entry into host cells. Cell. 2006;124:715–727. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Loessner MJ. Enterobacter sakazakii invasion in human intestinal Caco-2 cells requires the host cell cytoskeleton and is enhanced by disruption of tight junction. Infect Immun. 2008;76:562–570. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00937-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grützkau A, Hanski C, Hahn H, Riecken EO. Involvement of M cells in the bacterial invasion of Peyer's patches: a common mechanism shared by Yersinia enterocolitica and other enteroinvasive bacteria. Gut. 1990;31:1011–1015. doi: 10.1136/gut.31.9.1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick BA, Parkos CA, Colgan SP, Carnes DK, Madara JL. Apical secretion of a pathogen-elicited epithelial chemoattractant activity in response to surface colonization of intestinal epithelia by Salmonella typhimurium. J Immunol. 1998;160:455–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara BP, Koutsouris A, O'Connell CB, Nougayréde JP, Donnenberg MS, Hecht G. Translocated EspF protein from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli disrupts host intestinal barrier function. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:621–629. doi: 10.1172/JCI11138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peralta-Ramírez J, Hernandez JM, Manning-Cela R, Luna-Muñoz J, Garcia-Tovar C, Nougayréde JP, Oswald E, Navarro-Garcia F. EspF Interacts with nucleation-promoting factors to recruit junctional proteins into pedestals for pedestal maturation and disruption of paracellular permeability. Infect Immun. 2008;76:3854–68. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00072-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvey MA, Schilling JD, Hultgren SJ. Establishment of a persistent Escherichia coli reservoir during the acute phase of a bladder infection. Infect Immun. 2001;69:4572–4579. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.7.4572-4579.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansonetti PJ, Kopecko DJ, Formal SB. Involvement of a plasmid in the invasive ability of Shigella flexneri. Infect Immun. 1982;35:852–860. doi: 10.1128/iai.35.3.852-860.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinée PAM, Jansen WH, Wadström T, Sellwood R. In: Laboratory Diagnosis in Neonatal Calf and Pig Diarrhoea: Current Topics in Veterinary and Animal Science. Leeww PW, Guinée PAM, editor. Martinus-Nijhoff, The Hague, Netherlands; 1981. Escherichia coli associated with neonatal diarrhoea in piglets and calves; pp. 126–162. [Google Scholar]

- Luck SN, Bennett-Wood V, Poon R, Robins-Browne RM, Hartland EL. Invasion of epithelial cells by locus of enterocyte effacement-negative enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 2005;73:3063–3071. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.5.3063-3071.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]