Abstract

Neural stem/progenitor cells (NPC) have gained wide interest over the last decade from their therapeutic potential, either through transplantation or endogenous replacement, after central nervous system (CNS) disease and damage. Whereas several growth factors and cytokines have been shown to promote NPC survival, proliferation, or differentiation, the identification of other regulators will provide much needed options for NPC self-renewal or lineage development. Although previous studies have shown that pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP)/vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) can regulate stem/progenitor cells, the responses appeared variable. To examine the direct roles of these peptides in NPCs, postnatal mouse NPC cultures were withdrawn from epidermal growth factor (EGF) and fibroblastic growth factor (FGF) and maintained under serum-free conditions in the presence or absence of PACAP27, PACAP38, or VIP. The NPCs expressed the PAC1(short)null receptor isoform, and the activation of these receptors decreased progenitor cell apoptosis more than 80% from TUNEL assays and facilitated proliferation more than fivefold from bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) analyses. To evaluate cellular differentiation, replicate control and peptide-treated cultures were examined for cell fate marker protein and transcript expression. In contrast with previous work, PACAP peptides downregulated NPC differentiation, which appeared consistent with the proliferation status of the treated cells. Accordingly, these results demonstrate that PACAP signaling is trophic and can maintain NPCs in a multipotent state. With these attributes, PACAP may be able to promote endogenous NPC self-renewal in the adult CNS, which may be important for endogenous self-repair in disease and ageing processes.

Keywords: PACAP, VIP, Neural progenitor cells, Proliferation, Apoptosis, Differentiation

Introduction

Neural stem/precursor cells (NPC) have recently generated much interest as a therapeutic means of reducing neural tissue loss after neurodegenerative diseases or central nervous system (CNS) injury. Identified in embryonic CNS and in discrete adult brain areas such as the subventricular zone (SVZ) and the subgranular layer (SGZ) of the hippocampal dentate gyrus, NPCs are unique for their continuous self-renewal and multipotent abilities to generate neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes upon exposure to specific differentiation signals (Gage 2000; Alvarez-Buylla and Garcia-Verdugo 2002; Doetsch 2003; Taupin 2006). Hence, the critical regulatory events that orchestrate the proliferation and maturation of NPCs are not only important in the cytoarchitectural organization of the developing brain, but also in maintaining neurogenesis in the mature CNS. In the latter processes, adult rodent SVZ NPC migration through the rostral-migratory stream is essential in replacing olfactory bulb interneurons (Kornack and Rakic 2001). Neurogenesis in the adult hippocampal dentate gyrus has crucial roles in learning, memory, and behavioral states (Gould et al. 1999; Ueki et al. 2003; Sahay and Hen 2007). Increasingly, the same population of adult NPCs are recognized to represent a potential endogenous means for neural regeneration and self-repair (Goldman 2005; Martino and Pluchino 2006). Stimulation of NPC proliferation and neurogenesis, for example, has been suggested to improve functional CNS recovery after various injuries such as ischemic insults (Nakatomi et al. 2002; Lichtenwalner and Parent 2006). From these considerations, understanding the mechanisms that can promote NPC survival and proliferation may have important developmental and therapeutic applications.

Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) and vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) belong to the same family of peptides and have well-established trophic properties through shared G protein-coupled receptor signaling (Arimura 1998; Sherwood et al. 2000; Vaudry et al. 2000). Only PACAP peptides exhibit high affinity for the PAC1 receptor, whereas VIP and PACAP have similar high affinities for VPAC1 and VPAC2 receptors. Whereas VPAC receptors appear to be coupled predominantly to adenylyl cyclase, PAC1 receptor isoforms display unique patterns of adenylyl cyclase, phospholipase C (PLC), and other downstream signaling activation, resulting from the alternative splicing of two 84 bp Hip or Hop exons in the region encoding the third cytoplasmic loop (Spengler et al. 1993). The diversity in receptor second messenger activation, including cAMP/PKA, PLC/IP3/DAG/PKC, and MAPK among others, has been suggested to be central to the many trophic responses. PACAP, VIP, and their receptors have been identified during early neural development and have been implicated in precursor cell mitosis, neurogenesis, and neuronal survival (Gressens et al. 1993; Waschek 1996; Lu et al. 1998; Waschek et al. 1998; Nicot and DiCicco-Bloom 2001). Furthermore, PACAP and VIP peptides also protect adult neurons from apoptosis. PACAP increases sensory, autonomic, and cerebellar neuronal survival from growth factor or serum deprivation (Cavallaro et al. 1996; Tanaka et al. 1997; Lioudyno et al. 1998; Przywara et al. 1998; Vaudry et al. 1998); protects cerebellar neurons from apoptosis upon abrogation of depolarizing conditions (Cavallaro et al. 1996; Campard et al. 1997; Tanaka et al. 1997; Villalba et al. 1997; Vaudry et al. 1998); and preserves ventral mesencephalic and cortical neurons from 6-hydroxy-dopamine and glutamate neurotoxicity (Morio et al. 1996; Takei et al. 1998). Moreover, PACAP significantly reduces neuronal apoptosis and cortical infarct size after ischemia (Uchida et al. 1996; Ohtaki et al. 2006). The same survival functions may be related to the proliferative activities of VIP and PACAP in many cell types, including retinal epithelial cells, sympathetic neuroblasts, and olfactory neuroepithelial basal cells. PACAP is frequently several orders of magnitude more potent than VIP in inducing trophic responses, suggesting that the peptide proliferation effects are mediated by PACAP-selective PAC1 receptors (DiCicco-Bloom et al. 2000). However, PACAP and VIP have also been implicated in differentiation and antiproliferative activities in other neuronal systems. PACAP increases rat cerebellar, dorsal root ganglion (DRG) explant, and chromaffin cell neurite outgrowth in vitro (Wolf and Krieglstein 1995; Gonzalez et al. 1997; Lioudyno et al. 1998; Nielsen et al. 2004), and in rat cortical neurons, PACAP decreases the proportion of proliferating cells and promotes morphological and biochemical differentiation, suggesting that PACAP induces cell cycle withdrawal and promotes neuronal development (Lu and DiCicco-Bloom 1997; Nicot and DiCicco-Bloom 2001; Carey et al. 2002).

Although several studies have now shown that PACAP-related peptides or their receptors are highly expressed in the subventricular zone in the developing and mature CNS in vivo (Jaworski and Proctor 2000) and that embryonic stem cells and neural progenitor cells respond to PACAP peptides in vitro, the effects of PACAP or VIP on multipotent cells have remained equivocal. Whereas some studies demonstrate that PACAP may stimulate murine neural progenitor cell (mNPC) proliferation (Mercer et al. 2004), there are also reports suggesting that the neuropeptides promote stem or progenitor cell differentiation into neurons or astrocytes (Ohta et al. 2006; Watanabe et al. 2006; Nishimoto et al. 2007). Some of the variability in responses may have reflected the influence of growth factors in the culture preparation (Sievertzon et al. 2005). In clarifying and extending these observations, we demonstrate that mNPCs express almost exclusively the PAC1(short)null receptor isoform and that the activation of these receptors in the absence of complex growth factor signaling can stimulate mNPC survival and proliferation and maintain progenitor cells in an undifferentiated state.

Materials and Methods

Isolation of Murine Neural Progenitor Cells (mNPC)

NPCs were prepared from postnatal day 4 C57/BL6 mouse brains by Dr. Jeffrey Spees at the University of Vermont College of Medicine Stem Cell Core Facility. The tissues were minced and enzymatically dissociated using the NeuroCult Enzymatic Dissociation Kit (StemCell Technologies), and the resulting cells were cultured under optimal conditions for neurosphere formation. The undifferentiated progenitor cells and neurospheres were maintained in Neurobasal-A medium containing B27 supplement, 10 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (EGF), 10 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF), 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 µg/ml streptomycin. For mNPC survival, proliferation, and differentiation assays, the cells (passage 4–5) were cultured on poly-D-lysine- and laminin-coated plates until 80% confluency before growth factor withdrawal. The cultures were subsequently rinsed and maintained in the same Neurobasal-A and B27-supplemented medium without added EGF and FGF. PACAP and VIP peptides were from American Peptide.

Cell Viability Assays

Terminal transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay was performed to assess cell apoptosis. Biotinylated dUTP was incorporated into late stage fragmented DNA using terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (Promega), and labeled cell nuclei were visualized after incubation with streptavidin fluorescein isothiocyanate (1:1,000; Jackson Immunoresearch) by fluorescence microscopy. The number of TUNEL-labeled apoptotic cells is expressed as a fraction of total cells enumerated from Hoechst nuclear staining. At least four nonoverlapping fields were counted per slide and three replicates were prepared for each experimental group. Cell viability was also assessed using membrane permeable calcein acetomethoxy ester (calcein AM), which fluoresces after uptake, and intracellular hydrolysis by esterases. After growth factor withdrawal and treatments, the mNPC cultures were incubated in 2 µM calcein AM solution at 37°C for 30 min before quantitative fluorescence measurements. Data represent the mean of four replicate cultures±standard error of the mean (SEM).

Cell Proliferation Assay

Cell proliferation was assessed using the S phase marker bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU). Upon 80% culture confluency, mNPCs were incubated in 100 µM BrdU for 90 min before processing in Zamboni’s 4% paraformaldehyde–picric acid fixative. The cultures were rinsed, exposed to 2 N HCl for 1 h, blocked in 10% horse serum, and incubated overnight in 1:100 mouse anti-BrdU IgG (Roche). After washing and incubation with a Cy3-conjugated donkey antimouse antibody (1:500), the proliferating BrdU-labeled cells were enumerated as a proportion of total cells in four random nonoverlapping fields in each of three coverslips per experimental group. Data represent the mean±SEM.

Western Blot Analyses

For Western blot analyses, the mNPC cultures were lysed in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 120 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 0.1% SDS) containing 0.3 mg/ml phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and protease inhibitor mix (16 µg/ml benzamidine, 2 µg/ml leupeptin, 50 µg/ml lima bean trypsin inhibitor, 2 µg/ml pepstatin A). The proteins (32 µg) were fractionated on 4–12% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred onto Immobilon-P PVDF membranes (Millipore) for Western blot analyses using primary antibodies to βIII tubulin (Sigma), glial fibrillary acid protein (GFAP; Applied Biological Material), myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG; R&D Systems), and actin (Santa Cruz); the blots were stripped in 62.5 mM Tris–HCl, pH 6.7, containing 2% SDS and 100 mM β-mercaptoethanol at 50°C for 90 min before each reprobing procedure. The blots were processed for enhanced electrochemical detection; all blots were exposed to autoradiographic film to ensure signal removal before readdition of antisera. From high-resolution densitometry (Odyssey 2.0), relative changes in protein expression were determined from data normalized to actin.

Semiquantitative and Quantitative PCR

mNPC cultures were homogenized in Stat-60 total RNA/mRNA isolation reagent (Tel-Test “B”, Friendswood, TX, USA) as described previously (Braas and May 1999; Girard et al. 2002, 2004). The RNA was used to synthesize first-strand cDNA using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase and random hexamer primers with the SuperScript II Preampli-fication System (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) in a 20-µl final reaction volume. After the reverse transcriptase reaction, the cDNA samples were treated with RNase H to remove residual RNA. Semiquantitative PCR for PAC1, VPAC1, and VPAC2 receptors was performed exactly as describe previously (Braas and May 1999). For real-time quantitative PCR measurements, TaqMan Master Mix and TaqMan primers and probes for βIII tubulin, MOG, and GFAP were all from Applied Biosystems. The amplification was performed on an ABI 7500 Fast Real-time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) using the following standard conditions: (1) heating at 95°C for 10 min and (2) amplification performed over 50 cycles at 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 60 s. Transcript levels were determined using the comparative 2(−ΔΔCT) method; all data were normalized to actin levels in the same sample. Data represent the mean of six replicates±SEM.

Statistics

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine the differences among treatments. Newman–Keuls test was used in post hoc analysis to determine which treatments were different from others. P<0.05 was considered significant. All values represent the mean±SEM. Calculations were performed using SigmaStat and SigmaPlot (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Murine Neural Precursor Cells Express PAC1 and VPAC2 Receptors

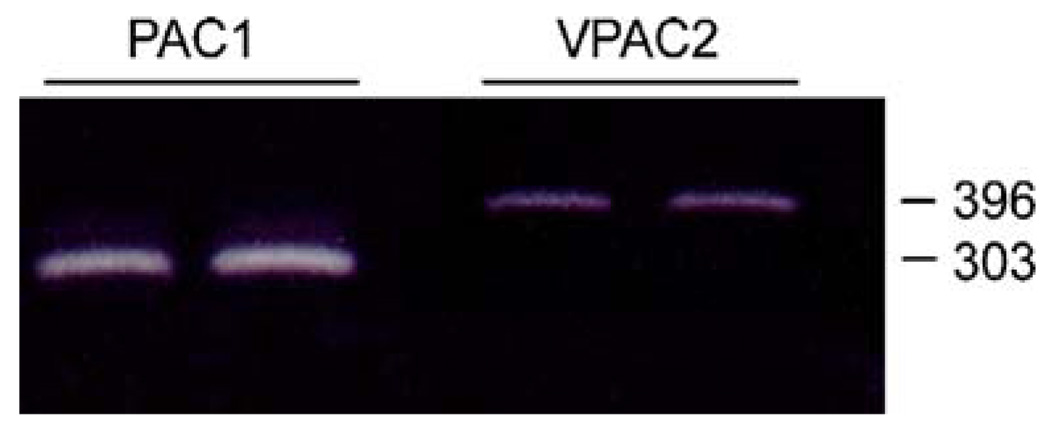

Many developing and mature neural cells express the different PACAP and VIP receptor subtypes. To assess PACAP and VIP receptor expression in mNPC isolated from postnatal mouse brain, total RNA was isolated from the cultures for semiquantitative PCR analyses. Using oligonucleotide primers flanking sequences encoding the third cytoplasmic loop of the PAC1 receptor, only a 303-bp product was amplified, suggesting that mNPCs expressed exclusively the PAC1null receptor isoform containing neither HIP nor HOP cassettes (Fig. 1). PCR of the same mNPC cDNA templates with primers to the receptor N-terminal region demonstrated the presence of exons 4 and 5 corresponding to the 21 amino acid insert for the short receptor variant. The VPAC2 receptor transcript abundance was extremely low, and the VPAC1 receptor transcript was not apparent under current culture or amplification parameters (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Murine NPCs express PAC1 and VPAC2 receptors. Total RNA from NPC neurospheres was reversed transcribed and the cDNA prepared for PAC1 and VPAC receptor transcript analyses by semiquantitative PCR as described previously (Braas and May 1999). Oligonucleotide primers for the PAC1 receptor flanked sequences encoding the third cytoplasmic loop and amplified a 303-bp product corresponding to the PAC1 null (neither Hip nor Hop cassette insert isoforms); the one and two cassette variants appeared negligible. VPAC2 transcript expression (396 bp) in mNPCs was less abundant and VPAC1 receptor mRNA expression was not detected (not shown). Receptor transcript expression patterns were the same in mNPCs seeded onto coated substrates. Each lane represents an independent culture replicate

PACAP and VIP Promote mNPC Viability

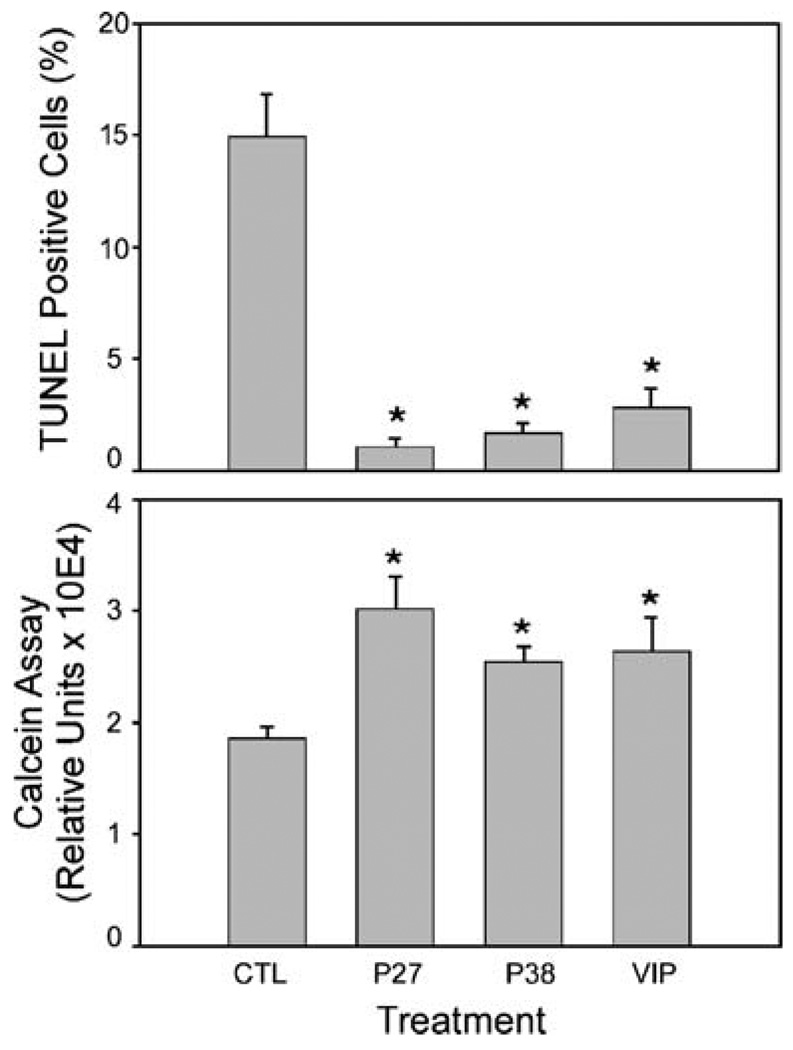

EGF and FGF supplements in the culture medium maintain mNPCs in a proliferative and undifferentiated state. PACAP and VIP peptides have well-described trophic properties and can abrogate apoptosis in many neural and peripheral tissues under diverse insult paradigms. To determine whether mNPC apoptosis upon growth factor withdrawal can be attenuated by PACAP or VIP peptides, mNPCs were first cultured in media with EGF and FGF until 80–90% confluency. The cultures were subsequently rinsed and maintained in EGF/FGF-free medium in the presence or absence of 100 nM PACAP27, PACAP38, or VIP peptide for 24 h before TUNEL analyses for fragmented genomic DNA. From cell enumeration, approximately 15% of total culture mNPCs were apoptotic after growth factor withdrawal (Fig. 2, top panel). The addition of PACAP or VIP peptides dramatically diminished the number of TUNEL positive cells 80–95%. Although PACAP appeared more efficacious and diminished the number of TUNEL-labeled mNPC to a greater extent compared to VIP, the differences among peptides were not statistically different. Treatment of the cultures with 100 nM PACAP or VIP elicited maximal neuroprotective effects. Treatment with 10 nM peptide concentrations produced similar survival response patterns but the response efficacies were more variable from cell passage to passage which may have reflected slight alterations in receptor density, maturation, or coupling to signaling effectors (data not shown).

Figure 2.

PACAP and VIP peptides promote mNPC survival. Murine NPCs were cultured on poly-D-lysine-coated substrates to 80–90% confluence before EGF and FGF growth factor withdrawal (CTL control) and 100 nM PACAP27 (P27) PACAP38 (P38) or VIP treatment (VIP) After 24 h, the cultures were prepared for TUNEL genomic DNA fragmentation analyses (top panel) or calcein AM measurements (lower panel) as described in the “Materials and Methods” section; n=4 separate coverslips or culture wells. Data represent the mean percent change compared to the control±SEM. *p<0.05, significantly different from the control

The abilities for PACAP and VIP to protect mNPCs from apoptosis were corroborated with calcein AM assays for cell viability. In separate experiments using the same treatment paradigms above, the addition of PACAP or VIP to the cultures after EGF and FGF withdrawal increased calcein fluorescence levels 35–60% compared to untreated controls (Fig. 2, lower panel). Consistent with TUNEL assays, similar peptide concentration dependence experiments demonstrated no apparent differences in efficacy among the different PACAP and VIP peptides examined.

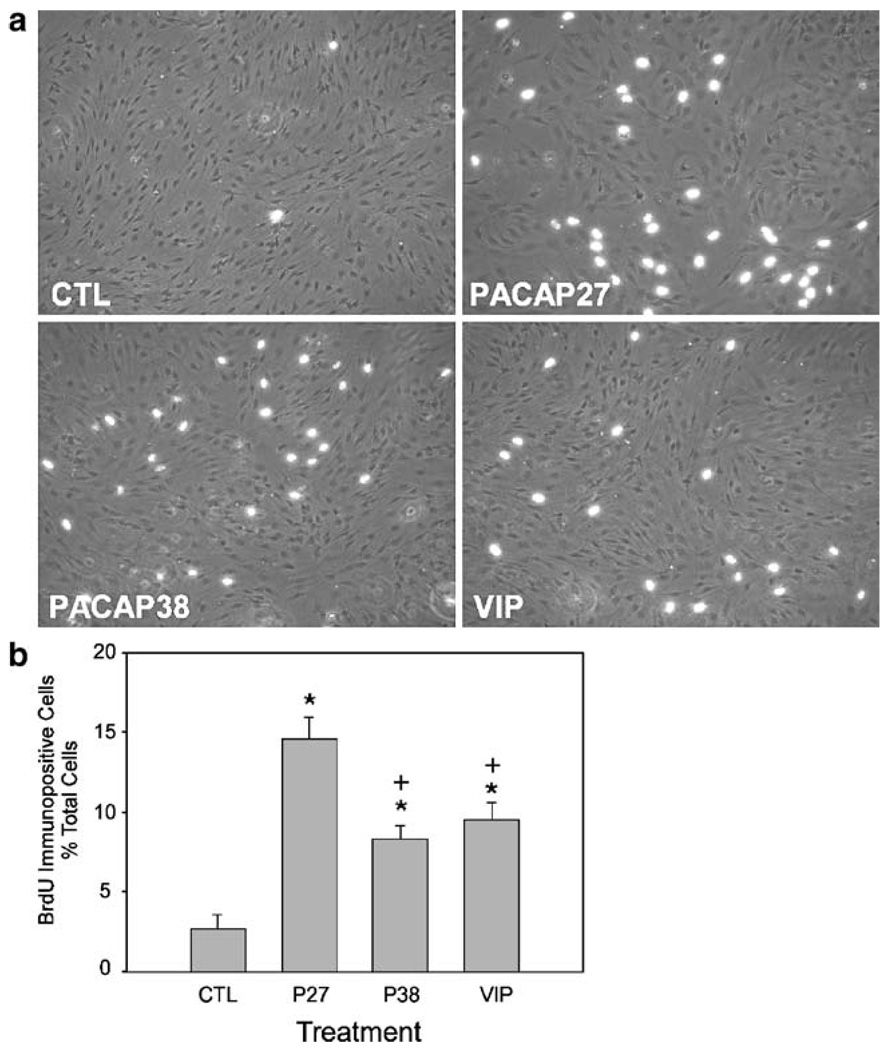

PACAP Stimulates mNPC Proliferation After EGF and FGF Withdrawal

The maintenance of undifferentiated stem and progenitor cell proliferation in vitro is dependent on EGF and FGF signaling. In many neuronal systems, PACAP and VIP neurotrophic signaling cannot only abrogate apoptotic cascades to facilitate survival, but also stimulate proliferation which may be important in establishing the appropriate neuronal populations and densities in specific CNS regions during development. To assess whether PACAP and VIP peptides are solely protective against growth factor withdrawal or possess parallel neuroproliferative properties in mNPC cultures, a series of BrdU-labeling studies were performed. In EGF- and FGF-supplemented medium, more than 60% of mNPCs were labeled with BrdU to demonstrate the high proliferative state of the cells under optimal culture conditions. Whereas growth factor withdrawal diminished mNPC proliferation precipitously to less than 3% of the population (Fig. 3), treatment of the same cultures with 100 nM PACAP27, PACAP38, or VIP for 24 h increased the number of BrdU-labeled mNPCs increased threefold to fivefold. In contrast to the survival assays, PACAP27 was more efficacious than either PACAP38 or VIP in these studies. However, PACAP and VIP were unable to completely supplant the mitogenic effects of EGF and FGF. Even after daily peptide additions, the number of proliferating BrdU-labeled mNPCs diminished upon chronic treatments to the minimal levels observed in growth factor-free conditions.

Figure 3.

PACAP peptides increase mNPC proliferation. Murine NPC cultures on coated coverslips were prepared as described in Fig. 2 and in the “Materials and Methods” section before 10 µM BrdU treatment (1.5 h) and processing using a Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody. a Representative micrographs under dual-phase and fluorescence microscopy; proliferating cells with BrdU-labeled nuclei in white. b BrdU-labeled cells shown in a were enumerated for quantitative analyses. CTL control, P27 PACAP27, P38 PACAP38; n=5 separate coverslips. Data represent the mean percent change compared to the control±SEM. *p<0.05, significantly different from the control; p<0.05, statistically different from PACAP27

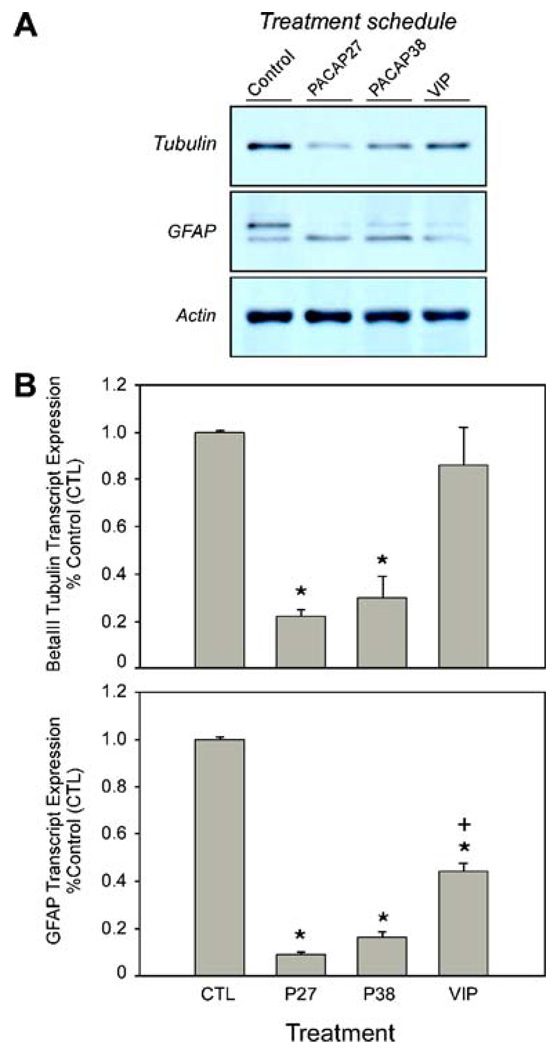

PACAP Inhibits mNPC Differentiation After Growth Factor Withdrawal

Despite the apparent transient nature of the PACAP- and VIP-mediated responses in mNPC cultures, the results above demonstrated that the trophic effects of PACAP and VIP share attributes with EGF and FGF receptor tyrosine kinase signaling. However, in facilitating proliferation, the EGF and FGF growth factors also generally downregulate neuronal precursor cell differentiation. As PACAP and VIP peptides have been implicated in differentiation processes, whether these peptides regulate mNPC fate and identities were also examined. To determine the regulatory effects of PACAP and VIP on the differentiation of NPCs, Western blot and quantitative PCR analyses were performed for neural phenotypic marker expression. Compared to control mNPC cultures maintained in growth factor-free medium, PACAP27 diminished neuronal βIII tubulin and astrocyte GFAP protein levels approximately 50% by quantitative Western blot analyses (Fig. 4); expression of the oligodendrocyte MOG protein was not apparent under these experimental conditions. Similar to the proliferation studies, VIP appeared to be less efficacious. The results were corroborated by quantitative PCR measurements for βIII tubulin and GFAP transcript expression in separate studies. In aggregate, these experiments demonstrated that PACAP signaling, in promoting cellular survival and proliferation, also extended the undifferentiated state of mNPCs.

Figure 4.

PACAP decreases mNPC cell lineage marker expression. a Murine NPCs were cultured to near confluence before growth factor withdrawal (CTL control) and treatments with 100 nM PACAP27, PACAP38, or VIP. After 72 h, the cultures were harvested for protein fractionation and Western blot analyses using antibodies to βIII tubulin, GFAP, MOG, and actin; the blots were stripped between each reprobing step; representative blot of three independent cultures for each group. For GFAP, the 50 kD intermediate filament protein is upper band. b Parallel cultures from the Western blot studies were prepared for quantitative PCR analyses using TaqMan primers and probes as described in the “Materials and Methods” section. MOG protein and transcripts were not identified in these studies (data not shown). Data represent the mean from six cultures±SEM. *p<0.05, significantly different from control; p<0.05, statistically different from PACAP27 or PACAP38

Discussion

Among the VIP and PACAP receptor subtypes, mNPC predominantly expressed the PAC1 receptor, in agreement with previous work. Expression of the VIP-preferring VPAC2 receptor mRNA appeared relatively low and VPAC1 receptor transcripts were not apparent in mNPCs despite high primer amplification efficiency in adult mouse brain cDNA samples. Whereas characterizations of the PAC1 receptor isoform appeared equivocal from previous studies (Mercer et al. 2004; Ohta et al. 2006), the current results, using primers spanning established splice sites, demonstrated that mNPC express the null receptor variant with neither Hip nor Hop alternative exons within the third cytoplasmic loop; similar diagnostic PCR analyses for N-terminal receptor sequences established the presence of the 63 nucleotide insert for the “short” receptor variant. These results coincided with data from Ohta et al. (2006). As the PAC1(short)null receptor is the predominant isoform in brain, its expression in mNPCs may be a reflection of CNS tissue specificity.

The preferential expression of the PAC1(short)null receptor in mNPCs may have important implications in downstream signaling and progenitor cell responses. Unlike the PAC1HOP1 receptor which demonstrates near equal high potency in cAMP/PKA and PLC activation, many primary neuronal studies have suggested that the PAC1(short)null receptor signaling is distinct and efficiently coupled solely to cAMP/PKA cascades (Lu et al. 1998; Nicot and DiCicco-Bloom 2001). Neuroblast expression of the PAC1(short)null receptor is better correlated with mitotic inhibition and differentiation, whereas the PAC1HOP1 receptor variant is better associated with proliferation events. Indeed, whereas PACAP signaling at the PAC1null receptor in embryonic cortical cells typically inhibited mitosis, ectopic expression of the PAC1HOP1 receptor isoform into the same cells transformed the response into neuronal proliferation (Nicot and DiCicco-Bloom 2001). In the current BrdU studies, whether PAC1(short)null receptor activation facilitated mNPC proliferation solely from cAMP/PKA signaling or from other second messenger pathway activation, including PLC/IP3 as suggested from heterologous cell line transfection studies (Spengler et al. 1993), remains to be established.

After EGF and FGF growth factor withdrawal, a large proportion of mNPCs rapidly demonstrated apoptosis from TUNEL assays. Under these conditions, PACAP and VIP peptides promoted mNPC survival and abrogated the apoptosis response as measured by both TUNEL and calcein fluorescence measurements. As in the proliferation assays, PACAP27, PACAP38, and VIP were effective prosurvival peptides in mNPCs; the efficacy of the various peptides for the survival vs proliferation trophic responses, however, appeared to be slightly different. Whereas 100 nM PACAP and VIP peptides demonstrated apparent equal efficacy in promoting mNPC survival, PACAP27 appeared to be more efficacious in promoting mitosis. The former may be related to high peptide potency in activating survival signaling cascades at either the PAC1 and/or VPAC2 receptors in mNPCs. Although VPAC2 receptor transcript levels appeared relatively low in mNPCs, for example, VPAC2 receptor protein expression and efficacy in second messenger activation may be significant to either mediate survival or coordinate prosurvival responses with PAC1 receptor signaling. For the latter, the PACAP/VIP proliferation response pattern may be more consistent with mNPC PAC1 receptor isoform signaling. In good agreement with other work, VIP was less efficacious than PACAP27 in stimulating proliferation, which may be a reflection of PAC1 receptor ligand selectivity (Mercer et al. 2004). As noted in other studies, the efficacy of PACAP27 and PACAP38 in mNPC proliferation appeared different. Whereas the responses may have reflected differences in peptide isoform binding to the N-terminal of the PAC1 receptor variants (Pantaloni et al. 1996), the relative stability of PACAP27 vs PACAP38 may have been a contributing factor in these studies (Bourgault et al. 2008).

Although the mechanisms underlying the PACAP- and VIP-mediated trophic effects in mNPC require further study, the dramatic abilities for these peptides to supplant FGF and EGF and promote survival and facilitate mitogenic regulation were entirely consistent with other work in adult and developing neural tissues. PACAP or the PAC1/VPAC receptors have been identified in proliferative zones of the CNS. PACAP and VIP peptides protect neurons from apoptosis under a variety of injury paradigms and can enhance diverse neuroblast proliferation in vivo and in vitro. In the current studies, the abilities for PACAP signaling to facilitate mNPC survival and proliferation are also in good agreement with other neural stem and progenitor cell reports. PACAP promoted embryonic and adult neural stem cell survival and/or proliferation; interestingly, the preponderance of data from inhibitor studies demonstrate that these trophic responses are PLC/PKC-dependent and PKA-independent (Mercer et al. 2004; Ohta et al. 2006). Our ongoing work will determine whether the same second messenger pathways are operational for survival and proliferation in our mNPCs. But as forskolin cannot fully recapitulate the current PACAP studies, the trophic responses may depend on multiple signaling pathway activation. Also, the proliferative effects of PACAP and VIP appeared transient. Whereas the underlying mechanisms are unclear, they may be related to receptor internalization/desensitization processes. In our preliminary work with cell lines transfected with GFP-tagged PAC1 receptors, chronic PACAP treatments appear to result in increasingly progressive receptor translocation into intracellular compartments which may contribute to the transient nature of the signaling response.

It is interesting to note that many of the same studies have also suggested that PACAP signaling can guide stem/progenitor cell differentiation to a neuronal or astrocyte cell fate (Cazillis et al. 2004; Mercer et al. 2004; Ohta et al. 2006; Watanabe et al. 2006; Nishimoto et al. 2007). These observations appear contrary to expectations as proliferation is frequently associated with cells in an undifferentiated state. Whereas the withdrawal of growth factors from the mNPC cultures can induce neuronal and astrocyte marker expression, as described in previous studies, the addition of PACAP in our current work suppressed both βIII tubulin and GFAP protein and transcript expression in mNPCs. Whereas these results contrast with other work for reasons that are unclear, they may be related to the original source of the neural progenitor cells and culture maintenance and treatment conditions (Sievertzon et al. 2005). Whereas most stem or progenitor studies with PACAP include one of the growth factor supplements to ensure culture viability, the current studies reflected signaling from the PACAP or VIP peptide alone. As the progenitor cell gene expression profile with PACAP can be very different in the presence of FGF and EGF, the differentiation responses observed in other studies may represent consequences of coordinate G protein-coupled receptor and receptor tyrosine kinase signaling. Similar to the proliferation responses, PACAP appeared to be more efficacious than VIP in suppressing lineage transcript marker expression. Coupled with the prosurvival and proliferation functions of PACAP, these results suggest that PACAP signaling may be capable of maintaining mNPCs in an undifferentiated state for population self-renewal and expansion.

The identification of factors capable of maintaining CNS NPC populations is important in a variety of contexts. Developmentally, the rates of NPC proliferation and differentiation are determinants that define neuronal populations and cytoarchitecture. In adults, continuous NPC renewal has been implicated in learning and memory, maintaining olfactory function, mediating therapeutics for behavioral or psychiatric disorders, and providing an endogenous means of neuronal repair after injury (Gould et al. 1999; Santarelli et al. 2003; Ueki et al. 2003; Goldman 2005; Sohur et al. 2006; Okano et al. 2007; Sahay and Hen 2007; Zhang et al. 2008). More recently, diminished adult NPC proliferation and function has been implicated in CNS ageing and degenerative processes (Sharpless and DePinho 2007). If accumulating cellular insults or changes in environmental niches result in decreased NPC regenerative capacity to repair CNS damage from degenerative diseases or injury, then diminished NPC proliferation may be an important contributor to the constellation of neurological defects associated with CNS ageing. Several growth factors and cytokines, including EGF, bFGF, vascular endothelial growth factor, brainderived nerve growth factor, prolactin, leukemia inhibitory factor, and ciliary neurotrophic factor have been shown to be capable of promoting stem cell renewal; the addition of PACAP/VIP peptides to the repertoire not only presents alternatives, but also options for coordinate treatments to amplify and refine NPC responses.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Molecular Biology Core Facility at the University of Vermont Neuroscience Center for Biomedical Research Excellence (COBRE) for the assistance with some PCR assays, Jeffrey Spees from Vermont Stem Cell Core for the preparation of murine NPCs, and Mari Tobita and Hillel Panitch for the helpful discussions.

Contributor Information

Eugene Scharf, Department of Neurology, College of Medicine, University of Vermont, 1 South Prospect Street, UHC—Neurology, Burlington, VT 05401, USA.

Victor May, Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology, University of Vermont College of Medicine, 149 Beaumont Avenue, Burlington, VT 05405, USA.

Karen M. Braas, Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology, University of Vermont College of Medicine, 149 Beaumont Avenue, Burlington, VT 05405, USA

Kristin C. Shutz, Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology, University of Vermont College of Medicine, 149 Beaumont Avenue, Burlington, VT 05405, USA

Yang Mao-Draayer, Email: yang.mao-draayer@uvm.edu, Department of Neurology, College of Medicine, University of Vermont, 1 South Prospect Street, UHC—Neurology, Burlington, VT 05401, USA.

References

- Alvarez-Buylla A, Garcia-Verdugo JM. Neurogenesis in the adult subventricular zone. Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;22:629–634. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-03-00629.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arimura A. Perspectives on pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide (PACAP) in the neuro-endocrine, endocrine, and nervous systems. Japanese Journal of Physiology. 1998;8:301–331. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.48.301. doi:10.2170/jjphysiol.48.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgault S, Vaudry D, Botia B, Couvineau A, Laburthe M, Vaudry H, et al. Novel stable PACAP analogs with potent activity towards the PAC1 receptor. Peptides. 2008;29:919–932. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2008.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braas KM, May V. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptides directly stimulate sympathetic neuron NPY release through PAC1 receptor isoform activation of specific intracellular signaling pathways. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:27702–27710. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.39.27702. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.39.27702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campard PK, Crochemore C, Rene F, Monnier D, Koch B, Loeffler JP. PACAP type I receptor activation promotes cerebellar neuron survival through the cAMP/PKA signaling pathway. DNA and Cell Biology. 1997;16:323–333. doi: 10.1089/dna.1997.16.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey RG, Li B, DiCicco-Bloom E. Pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide anti-mitogenic signaling in cerebral cortical progenitors is regulated by p57Kip2-dependent CDK2 activity. Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;22:1583–1591. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-05-01583.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavallaro S, Copani A, D’Agata V, Musco S, Petralia S, Ventra C, et al. Pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide prevents apoptosis in cultured cerebellar granule neurons. Molecular Pharmacology. 1996;50:60–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazillis M, Gonzalez BJ, Billardon C, Lombet A, Fraichard A, Samarut J, et al. VIP and PACAP induce selective neuronal differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;19:798–808. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816x.2004.03138.x. doi:10.1111/j.0953-816X.2004.03138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiCicco-Bloom E, Deutsch PJ, Maltzman J, Zhang J, Pintar JE, Zheng J, et al. Autocrine expression and ontogenetic function of the PACAP ligand/receptor system during sympathetic development. Developmental Biology. 2000;219:197–213. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9604. doi:10.1006/dbio.2000.9604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doetsch F. A niche for adult neural stem cells. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 2003;13:543–550. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2003.08.012. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2003.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage FH. Mammalian neural stem cells. Science. 2000;287:1433–1438. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5457.1433. doi:10.1126/science.287.5457.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard BM, Keller ET, Schutz KC, May V, Braas KM. Pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide and PAC1 receptor signaling increase Homer 1a expression in central and peripheral neurons. Regulatory Peptides. 2004;123:107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2004.05.024. doi:10.1016/j.regpep.2004.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard BM, May V, Bora SH, Fina F, Braas KM. Regulation of neurotrophic peptide expression in sympathetic neurons: Quantitative analysis using radioimmunoassay and real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Regulatory Peptides. 2002;109:89–101. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(02)00191-x. doi:10.1016/S0167-0115(02)00191-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman S. Stem and progenitor cell-based therapy of the human central nervous system. Nature Biotechnology. 2005;23:862–871. doi: 10.1038/nbt1119. doi:10.1038/nbt1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez BJ, Basille M, Vaudry D, Fournier A, Vaudry H. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide promotes cell survival and neurite outgrowth in rat cerebellar neuroblasts. Neuroscience. 1997;78:419–430. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00617-3. doi:10.1016/S0306-4522(96)00617-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould E, Beylin A, Tanapat P, Reeves A, Shors TJ. Learning enhances adult neurogenesis in the hippocampal formation. Nature Neuroscience. 1999;2:260–265. doi: 10.1038/6365. doi:10.1038/6365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gressens P, Hill JM, Gozes I, Fridkin M, Brenneman DE. Growth factor function of vasoactive intestinal peptide in whole cultured mouse embryos. Nature. 1993;362:155–158. doi: 10.1038/362155a0. doi:10.1038/362155a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaworski DM, Proctor MD. Developmental regulation of pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide and PAC(1) receptor mRNA expression in the rat central nervous system. Developmental Brain Research. 2000;120:27–39. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(99)00192-3. doi:10.1016/S0165-3806(99)00192-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornack DR, Rakic P. The generation, migration, and differentiation of olfactory neurons in the adult primate brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:4752–4757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081074998. doi:10.1073/pnas.081074998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenwalner RJ, Parent JM. Adult neurogenesis and the ischemic forebrain. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2006;26:1–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600170. doi:10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lioudyno M, Skoglösa Y, Takei N, Lindholm D. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) protects dorsal root ganglion neurons from death and induces calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) immunoreactivity in vitro. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 1998;51:243–256. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980115)51:2<243::AID-JNR13>3.0.CO;2-9. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980115)51:210.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980115)51:2<243::AID-JNR13>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu N, DiCicco-Bloom E. Pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide is an autocrine inhibitor of mitosis in cultured cortical precursor cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94:3357–3362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3357. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.7.3357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu N, Zhou R, DiCicco-Bloom E. Opposing mitogenic regulation by PACAP in sympathetic and cerebral cortical precursors correlated with differential expression of PACAP receptor (PAC1-R) isoforms. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 1998;53:651–662. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980915)53:6<651::AID-JNR3>3.0.CO;2-4. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980915) 53:6<651::AID-JNR3>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino G, Pluchino S. The therapeutic potential of neural stem cells. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 2006;7:395–406. doi: 10.1038/nrn1908. doi:10.1038/nrn1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer A, Rönnholm H, Holmberg J, Lundh H, Heidrich J, Zachrisson O, et al. PACAP promotes neural stem cell proliferation in adult mouse brain. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2004;76:205–215. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20038. doi:10.1002/jnr.20038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morio H, Tatsuno I, Hirai A, Tamura Y, Saito Y. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide protects ratcultured cortical neurons from glutamate-induced cytotoxicity. Brain Research. 1996;741:82–88. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)00920-1. doi:10.1016/S0006-8993(96)00920- 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatomi H, Kuriu T, Okabe S, Yamamoto S, Hatano O, Kawahara N, et al. Regeneration of hippocampal pyramidal neurons after ischemic brain injury by recruitment of endogenous neural progenitors. Cell. 2002;110:429–441. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00862-0. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00862-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicot A, DiCicco-Bloom E. Regulation of neuroblast mitosis is determined by PACAP receptor isoform expression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:4758–4763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071465398. doi:10.1073/pnas.071465398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen KM, Chaverra M, Hapner SJ, Nelson BR, Todd V, Zigmond RE, et al. PACAP promotes sensory neuron differentiation: Blockade by neurotrophic factors. Molecular and Cellular Neurosciences. 2004;25:629–641. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2003.12.004. doi:10.1016/j.mcn.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimoto M, Furuta A, Aoki S, Kudo Y, Miyakawa H, Wada K. PACAP/PAC1 autocrine system promotes proliferation and astrogenesis in neural progenitor cells. Glia. 2007;55:317–327. doi: 10.1002/glia.20461. doi:10.1002/glia.20461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta S, Gregg C, Weiss S. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide regulates forebrain neural stem cells and neurogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2006;84:1177–1186. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21026. doi:10.1002/jnr.21026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtaki H, Nakamachi T, Dohi K, Aizawa Y, Takaki A, Hodoyama K, et al. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) decreases ischemic neuronal cell death in association with IL-6. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:7488–7493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600375103. doi:10.1073/pnas.0600375103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okano H, Sakaguchi M, Ohki K, Suzuki N, Sawamoto K. Regeneration of the central nervous system using endogenous repair mechanisms. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2007;102:1459–1465. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04674.x. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantaloni C, Brabet P, Bilanges B, Dumuis A, Houssami S, Spengler D, et al. Alternative splicing in the N-terminal extracellular domain of the pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) receptor modulates receptor selectivity and relative potencies of PACAP-27 and PACAP-38 in phospholipase C activat. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:22146–22151. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.36.22146. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.36.22146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przywara DA, Kulkarni JS, Wakade TD, Leontiev DV, Wakade AR. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide and nerve growth factor use the proteasome to rescue nerve growth factor-deprived sympathetic neurons cultured from chick embryos. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1998;71:1889–1897. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71051889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahay A, Hen R. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis in depression. Nature Neuroscience. 2007;10:1110–1115. doi: 10.1038/nn1969. doi:10.1038/nn1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santarelli L, Saxe M, Gross C, Surget A, Battaglia F, Dulawa S, et al. Requirement of hippocampal neurogenesis for the behavioral effects of antidepressants. Science. 2003;301:805–809. doi: 10.1126/science.1083328. doi:10.1126/science.1083328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpless NE, DePinho RA. How stem cells age and why this makes us grow old. Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology. 2007;8:703–713. doi: 10.1038/nrm2241. doi:10.1038/nrm2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood NM, Krueckl SL, McRory JE. The origin and function of the pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP)/glucagon superfamily. Endocrine Reviews. 2000;21:619–670. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.6.0414. doi:10.1210/er.21.6.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sievertzon M, Wirta V, Mercer A, Frisén J, Lundeberg J. Epidermal growth factor (EGF) withdrawal masks gene expression differences in the study of pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) activation of primary neural stem cell proliferation. BMC Neuroscience. 2005;6:55. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-6-55. doi:10.1186/1471-2202-6-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohur US, Emsley JG, Mitchell BD, Macklis JD. Adult neurogenesis and cellular brain repair with neural progenitors, precursors and stem cells. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 2006;361:1477–1497. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1887. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spengler D, Waeber C, Pantaloni C, Holsboer F, Bockaert J, Seeburg PH, et al. Differential signal transduction by five splice variants of the PACAP receptor. Nature. 1993;365:170–175. doi: 10.1038/365170a0. doi:10.1038/365170a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takei N, Skoglosa Y, Lindholm D. Neurotrophic and neuroprotective effects of pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) on mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 1998;54:698–706. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19981201)54:5<698::AID-JNR15>3.0.CO;2-5. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19981201)54:5<698::AID-JNR15>3.0.CO;2–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka J, Koshimura K, Murakami Y, Sohmiya M, Yanaihara N, Kato Y. Neuronal protection from apoptosis by pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide. Regulatory Peptides. 1997;72:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(97)01038-0. doi:10.1016/S0167-0115(97)01038-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taupin P. Adult neural stem cells, neurogenic niches, and cellular therapy. Stem Cell Reviews. 2006;2:213–219. doi: 10.1007/s12015-006-0049-0. doi:10.1007/s12015-006-0049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida D, Arimura A, Somogyvari-Vigh A, Shioda S, Banks WA. Prevention of ischemia-induced death of hippocampal neurons by pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide. Brain Research. 1996;736:280–286. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00716-0. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(96)00716-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueki T, Tanaka M, Yamashita K, Mikawa S, Qiu Z, Maragakis NJ, et al. A novel secretory factor, Neurogenesin-1, provides neurogenic environmental cues for neural stem cells in the adult hippocampus. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23:11732–11740. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-37-11732.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaudry D, Gonzalez BJ, Basille M, Anouar Y, Fournier A, Vaudry H. Pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide stimulates both c-fos gene expression and cell survival in rat cerebellar granule neurons through activation of the protein kinase pathway. Neuroscience. 1998;84:801–812. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00545-9. doi:10.1016/S0306-4522(97)00545-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaudry D, Gonzalez BJ, Basille M, Yon L, Fournier A, Vaudry H. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide and its receptors: From structure to functions. Pharmacological Reviews. 2000;52:269–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villalba M, Bockaert J, Journot L. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP-38) protects cerebellar granule neurons from apoptosis by activating the mitogenactivated protein kinase (MAP kinase) pathway. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:83–90. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-01-00083.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waschek JA. VIP and PACAP receptor-mediated actions on cell proliferation and survival. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1996;805:290–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb17491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waschek JA, Casillas RA, Nguyen TB, DiCicco-Bloom EM, Carpenter EM, Rodriguez WI. Neural tube expression of pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating peptide (PACAP) and receptor: Potential role in patterning and neurogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:9602–9607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9602. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.16.9602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe J, Ohba M, Ohno F, Kikuyama S, Nakamura M, Nakaya K, et al. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide-induced differentiation of embryonic neural stem cells into astrocytes is mediated via the beta isoform of protein kinase C. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2006;84:1645–1655. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21065. doi:10.1002/jnr.21065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf N, Krieglstein K. Phenotypic development of neonatal rat chromaffin cells in response to adrenal growth factors and glucocorticoids: Focus on pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide. Neuroscience Letters. 1995;200:207–210. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)12116-l. doi:10.1016/0304-3940(95)12116-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C-L, Zou Y, He W, Gage FH, Evans RM. A role for adult TLX-positive neural stem cells in learning and behavior. Nature. 2008;451:1004–1007. doi: 10.1038/nature06562. doi:10.1038/nature06562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]