Protein modification by ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like molecules is a critical regulatory process. Like most regulated protein modifications, ubiquitination is reversible. Deubiquitination, the reversal of ubiquitination, is quickly being recognized as an important regulatory strategy. Nearly a hundred human deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) in five different gene families oppose the action of several hundred ubiquitin ligases, suggesting that both ubiquitination and its reversal are highly regulated and specific processes. It has long been recognized that ubiquitin ligases are modular enzyme systems that often depend on scaffolds and adaptors to deliver substrates to the catalytically active macromolecular complex. While many DUBs bind ubiquitin with reasonable affinities (nM to μM) a larger number have little affinity but exhibit robust catalytic capability. Thus, it is apparent that these DUBs must acquire their substrates by binding the target protein in a conjugate or by associating with other macromolecular complexes [1]. We would then expect that a study of protein partners of DUBs would reveal a variety of substrates, scaffolds, adapters and ubiquitin receptors. In this review we suggest that, like ligases, much of the regulation and specificity of deubiquitination arises from the association of DUBs with these protein partners.

The Ubiquitin System

Over the last few decades, protein modification by ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like molecules has emerged as a critical regulatory process in virtually all aspects of cell biology. This importance is underscored by the fact that the 2004 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded for the discovery of ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis [2].

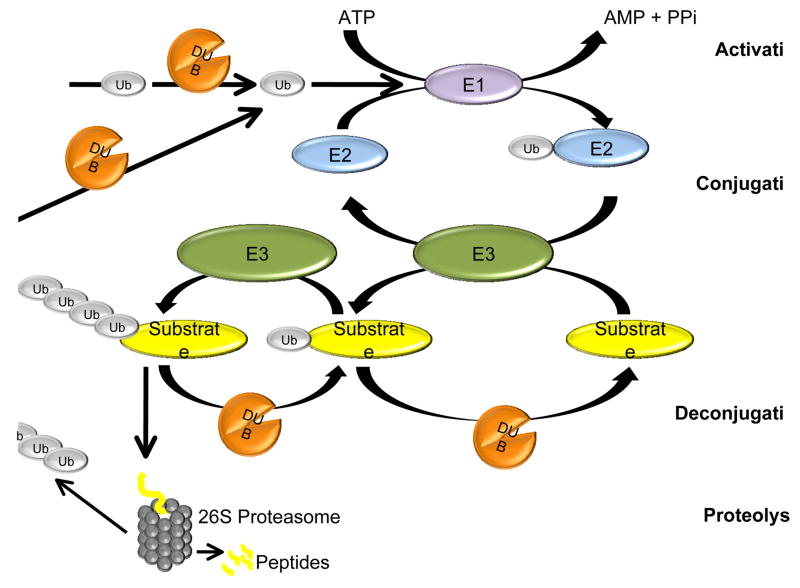

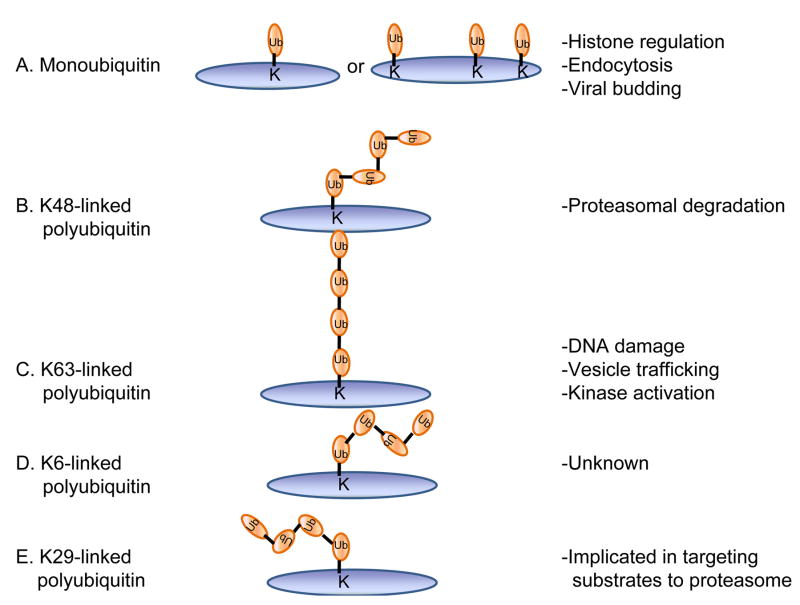

Ubiquitination, which is the process of covalently conjugating ubiquitin to a target protein, is accomplished through a series of reactions. In the first step an ubiquitin activating enzyme (E1) forms a thiol ester bond with the ubiquitin molecule in an ATP-dependent manner. The ubiquitin moiety is then transferred to one of a few dozen ubiquitin conjugating enzymes (E2) and then to a specific target protein via the action of one of several hundred ubiquitin ligases (E3), leading to the formation of an isopeptide bond between the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin and the epsilon-amino group on a lysine residue of the target protein [3–5]. The conjugation of one ubiquitin to a lysine residue on the target protein (monoubiquitination) has been implicated in different cellular processes including membrane trafficking, histone function, transcription regulation, DNA repair, and DNA replication [6]. Additional rounds of ubiquitination can modify the first ubiquitin to result in the formation of polyubiquitin chains linked through the C-terminus of one ubiquitin and a lysine residue of the preceding ubiquitin. Different chain topologies can be formed depending on which lysine residue on ubiquitin is used for conjugation. Different chain types have been implicated in signaling different outcomes, including protein degradation, directing the localization of the modified protein or modifying its activity, macromolecular interactions, or half-life [7, 8]. Ubiquitin modifications can be reversed by the action of enzymes collectively known as deubiquitinating enzymes.

Deubiquitinating Enzymes

Deubiquitination is performed by the action of deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), ubiquitin-specific proteases that can reverse target protein ubiquitination by editing or disassembling polyubiquitin chains and play an important role in several aspects of the ubiquitin–proteasome system [1]. Mutations in genes expressing DUBs have been implicated in a number of diseases including hereditary cancer and neurodegeneration [9–11].

There are five families of DUBs. Most are cysteine proteases but there is one family of metalloproteases. DUBs specifically cleave ubiquitin from ubiquitin-conjugated protein substrates, ubiquitin precursors, ubiquitin adducts and polyubiquitin [12]. The cysteine protease DUBs can be further organized into four subclasses based on their ubiquitin protease domains: ubiquitin-specific proteases (USP), ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolases (UCH), Otubain proteases (OTU), and Machado-Joseph disease proteases (MJD). All DUBs that are metalloproteases have an ubiquitin protease domain called JAMM (JAB1/MPN/Mov34 metalloenzyme). In addition, viruses [13] and bacteria [14] have both acquired or evolved deubiquitinating enzymes, probably to interfere with host cell processes as part of their mechanisms of virulence.

Nijman et al., 2005 used the ENSEMBLE human genome database to retrieve all putative DUBs from the human genome by selecting genes whose transcripts encode one of the five ubiquitin protease domains. This analysis indicated that the human genome encodes approximately 95 putative DUBs, including many that had not been previously reported. These were broken down into 58 USP, 4 UCH, 5 MJD, 14 OTU, and 14 JAMM domain-containing genes, many of which were associated with multiple transcripts [10]. The abundance of DUB family members presumably allows for diversity and specificity of DUB activity, although relatively little is known about the physiological substrates of individual members of the family.

Structural and biochemical studies on isolated DUBs have shown that many exist in conformations that require substrate binding [15, 16] or association with binding partners [17] to achieve the active conformation. Also, while many DUBs bind ubiquitin with reasonable affinities (nM to μM) a larger number have little affinity. A number of these poor binders have good catalytic capability, exhibiting kcat/Km values in excess of 105 M−1s−1 (unpublished observations). Thus, it is apparent that these DUBs must acquire their substrates by binding the target protein in a conjugate or by associating with other macromolecular complexes [1]. We would then expect that a study of protein partners of DUBs would reveal a variety of substrates, scaffolds, adaptors and ubiquitin receptors.

The specific biological roles of most DUBs remains unknown [18] and defining these roles may be facilitated by determining what their protein partners are. For instance, many DUBs have been shown to physically associate with ubiquitin ligases and their role in the ubiquitin pathway have often been inferred from the roles of the associated ligase. Given that the modes of regulation of DUBs and of their substrate specificity are not well understood this review collates the currently available information about DUBs and their interacting proteins. Some are biological substrates while others modulate activity of the DUBs. The DUBs chosen for discussion are those for which interacting proteins (other than ubiquitin) have been identified and we hope that this review will help shed light on the functions of DUBs based on their protein partners. Table 1 lists the DUBs mentioned in this paper and their respective binding partners.

Table 1.

| Name of DUB | Interacting Proteins | Role of Interaction | Comments | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E3 | Substrate | Regulatory | |||

| Ubiquitin-Specific Proteases (USP) | |||||

| USP1 | FANCD2 | X | USP1 implicated in Fanconi anemia-related cancer | ||

| UAF1 | X | ||||

| USP2a | Mdm2 | X | X | USP2a implicated in prostate cancer | |

| FAS | X | ||||

| USP4 | Ro52/TRIM21 | X | X | X | The two proteins trans-regulate each other by ubiquitination and deubiquitination |

| Adenosine receptor | X | Localization is regulated by USP4 | |||

| USP6/Tre2 | Myl2 | X | Localization is regulated by USP6 | ||

| LOC91256 | X | Localization is regulated by USP6 | |||

| USP7/HAUSP | p53 | X | USP7 potential target for anti-cancer drugs | ||

| Mdm2 | X | X | |||

| Mdmx | |||||

| EBNA1 | X | ||||

| ICP0 | X | ||||

| USP8/UBPY | SH3 domain proteins | X | USP8 is a target for cancer therapy | ||

| Nrdp1 | X | X | Function together in EGFR regulation | ||

| 14-3-3 epsilon | X | Regulates USP8 localization and stability | |||

| USP9 | AMPK kinases | X | |||

| Mind bomb 1 (Mib1) | X | ||||

| Vasa (VAS) | X | ||||

| Epsin/Lqf | X | ||||

| USP10/UBP3 | G3BP | X | |||

| Androgen receptor | X | Receptor function regulated by USP10 | |||

| USP11 | RelB complex | X | Regulate NF-kB pathway | ||

| BRCA2 | X | ||||

| USP14/UBP6 | 26S Proteasome | X | |||

| USP15/UBP12 | Signalosome (CSN) | X | |||

| USP20/VDU2 | VHL | X | X | Associated with the hereditary cancer syndrome von Hippel-Lindau | |

| HIF-1alpha | X | Proposed as a USP20 substrate | |||

| USP22/UBP8 | SAGA complex | X | |||

| USP28 | FBW7alpha | X | X | Co-regulate FBW7alpha substrate stability | |

| USP33/VDU1 | VHL | X | X | VHL regulates USP33 by ubiquitination | |

| Type 2 Deiodinase | X | ||||

| CYLD | NF-kB pathway proteins | X | Regulates NF-kB pathway | ||

| Bcl-3 | X | X | Localization regulated by CYLD | ||

| Ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolases (UCH) | |||||

| UCH-L1/PGP9.5 | JAB1 | X | |||

| UCH37 | S14 | X | S14 is a proteasome subunit | ||

| UIP1 | X | Competes with proteasome binding site on UCH37 | |||

| Rpn13 (Adrm1) | X | Binding activates UCH37 DUB activity | |||

| Smad7 | X | ||||

| BAP1 | BRCA1 | X | X | Implicated in breast and lung cancers | |

| Otubain proteases (OTU) | |||||

| A20 | NF-kB pathway proteins | X | Regulates NF-kB pathway | ||

| Cezanne | TRAF6 | X | Regulates NF-kB pathway | ||

| VCIP135 | Cdc48/p97 complex | X | Involved in golgi assembly and ER network formation | ||

| Machado-Joseph disease proteases (MJD) | |||||

| Ataxin-3 (AT3) | PLIC-1 | X | |||

| HDAC3 | X | ||||

| JAB1/MPN/Mov34 Metalloprotease (JAMM) | |||||

| AMSH | STAM | X | |||

| Clathrin | X | ||||

| ESCRT-III complex | X | Puts AMSH in functional vicinity | |||

| Rpn11/POH1 | 26S Proteasome | X | Rpn11 DUB activity activated upon proteasome binding | ||

I. CYSTEINE PROTEASES

A. Ubiquitin-Specific Proteases (USP)

USP1

USP1 is a DUB that has been implicated in Fanconi anemia (FA)-related cancer [19]. USP1 is involved in the process of DNA repair through its regulation of ubiquitinated Fanconi anemia protein FANCD2 levels [20, 21].

FANCD2

USP1 was found to co-immunoprecipitate with FANCD2 in HEK293 cell lysates, and the proteins are observed to co-localize in chromatin after DNA damage [20]. This study showed that knockdown of USP1 by siRNA lead to hyper-accumulation of monoubiquitinated FANCD2. USP1 is proposed to deubiquitinate FANCD2 when cells exit S phase or recommence cycling after DNA damage and may play a critical role in the FA pathway by recycling FANCD2 [20].

UAF1

USP1 isolated from HeLa cells was found to contain stoichiometric amounts of USP1 associated factor 1 (UAF1), a WD40 repeat-containing protein [22]. USP1 deubiquitinating enzyme activity against purified monoubiquitinated FANCD2 protein could be reconstituted in vitro, demonstrating that UAF1 functions as an activator of USP1. UAF1 binding increases the catalytic turnover (kcat) but not the affinity of the USP1 enzyme for the substrate (Km). DNA damage rapidly shuts down transcription of the USP1 gene, and leads to a rapid decline in the amount of the USP1/UAF1 protein complex.

USP2a

USP2a is a DUB with oncogenic properties that has been implicated in prostate cancer [23]. USP2a regulates the p53 pathway through its deubiquitinating activity [24] and has also been shown to deubiquitinate the anti-apoptotic protein Fatty Acid Synthase (FAS) [23]. The finding that USP2a is over-expressed in human prostate tumors has made it a potential therapeutic target in prostate cancer [23]. USP2a has also been suggested to play a part in normal spermatogenesis [25], another process in which p53 is thought to be involved [26, 27].

Mdm2

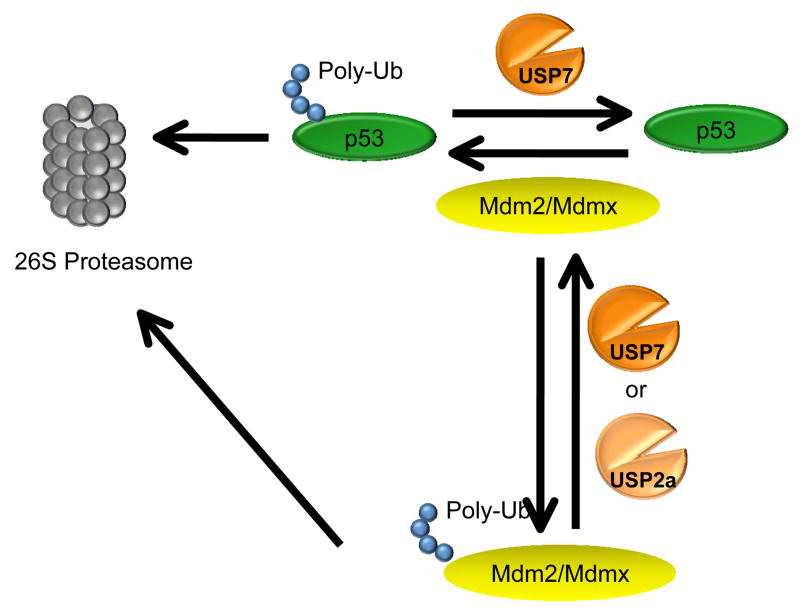

Mdm2 (Murine double minute 2) is an E3 ubiquitin ligase oncoprotein and a key regulator of the p53 tumor suppressor protein. It acts to ubiquitinate p53 and target the tumor suppressor for proteasome-mediated degradation [28]. A yeast 2-hybrid screen using Mdm2 as bait identified USP2a as a protein partner [24]. In this study, full-length USP2a was found to interact with and deubiquitinate Mdm2, thereby causing the accumulation of Mdm2 in a dose-dependent manner. Consequently, USP2a-medited deubiquitination and stabilization of Mdm2 promoted Mdm2-mediated p53 ubiquitination and degradation. p53 is one of the most important tumor suppressor proteins and plays an essential role in regulating the cell-cycle and apoptosis by sensing the integrity of the genome [29]. The fact that USP2a regulates p53 implies a role for the protein in human cancers. The action of USP2a within the cell is antagonistic to that of another DUB called USP7/HAUSP (see below). USP7 interacts with and deubiquitinates p53, thereby stabilizing and protecting it from Mdm2-mediated degradation [30]. A second USP2 isoforms (USP2b) results from alternative splicing and this isoform may also interact with Mdm2 [31].

Fatty Acid Synthase (FAS)

Fatty Acid Synthase (FAS), a protein expressed from an androgen-regulated gene [23], is often over-expressed in biologically aggressive human tumors [32] and promotes tumor growth by promoting the resistance to apoptosis [33]. FAS was found to interact with His-tagged USP2a via affinity-chromatography and mass spectrometry of an LNCaP (human prostate cancer cell) lysate and this interaction was confirmed by co-immunoprecipitation [32]. The findings from this study suggest that the USP2a enzyme acts by inhibiting FAS protein degradation by the proteasome, thereby resulting in the protection of prostate cancer cells from apoptosis. The finding that USP2a is involved in human prostate cancer, coupled with information derived from the crystal structure of the UPS2a catalytic domain [34] has made it a potential target for therapeutic drugs [23].

USP4/UnpEL/Unph

USP4 is a DUB with a suggested role as an oncogene because USP4 protein levels have been found to be elevated in small cell lung carcinomas and adenocarcinomas of the lung and overexpression of a mouse cDNA encoding Unp (USP4) leads to oncogenic transformation of NIH3T3 cells [35, 36].

Ro52/TRIM21

USP4 was found to interact with the protein Ro52 (also known as TRIM (tripartite motif) 21) in a yeast 2-hybrid assay and the interaction was confirmed by a mammalian 2-hybrid interaction in COS-1 cells [12]. Ro52 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that can ubiquitinate itself (self-ubiquitination) as well as ubiquitinate USP4 in vitro and in vivo. In contrast, USP4 can deconjugate ubiquitin from itself (self-deubiquitination) as well as deubiquitinate self-ubiquitinated Ro52 [37]. In other words the two proteins trans-regulate each other by ubiquitination and deubiquitination. The two proteins were shown to co-localize to cytoplasmic rod-like structures in HEK293 cells, suggesting that Ro52 interacts with USP4 in mammalian cells to form a heteromeric protein complex that mediates both ubiquitination and deubiquitination of substrates [38].

Adenosine A2A receptor

Adenosine A2A receptors are G protein-coupled receptors that have been shown to interact with USP4 through their C-terminal tail [39]. Intracellular A2A receptors are thought to be ubiquitinated, presumably because of misfolding and subsequent intervention by the “endoplasmic reticulum quality control” mechanism, thereby leading to degradation of the receptors by proteasomes [39]. The importance of the USP4-Adenosine A2A interaction lies in the ability of USP4 to stimulate receptor deubiquitination thereby increasing cell surface expression of functional receptors [40].

USP6/Tre2

USP6/Tre2 is expressed from the Tre2 oncogene, which is derived from the chimeric fusion of two genes: USP32 (NY-REN-60), coding for an ubiquitin-specific protease, and TBC1D3, encoding a Rab GTPase-activating protein (RabGAP) [41]. USP6 is structurally related to the Ypt/RabGTPase-activating proteins (Ypt/RabGAP) and is involved in various human cancers, including Ewing’s sarcoma [42].

Light regulatory chain of myosin II (Myl2) and LOC91256

In order to identify proteins that interact with the GAP domain of USP6 a yeast 2-hybrid screen was done with two cDNA libraries from human tissues (skeletal muscle and placenta). Two components of the cytoskeleton were identified: light regulatory chain of myosin II (Myl2) and LOC91256 [43]. Myl2 is a component of Myosin II that stabilizes the long alpha-helical neck of the myosin head and regulates its ATPase activity [44]. LOC91256 is a protein containing ankyrin repeats and shows similarity to a region of the cytoskeletal anchor protein ankyrin 1. Both proteins were confirmed to interact with USP6 by a GST-pull down assay in vitro and co-immunoprecipitation, and co-localization experiments in vivo [43]. Although the biological significance of these interactions remains unknown, the observation that USP6 appeared to cause redistribution of Myl2 and LOC91526 to the cell membrane lead to the proposal that the binding of USP6 to Myl2 participates in RhoGTPase signaling [43, 45].

USP7/HAUSP

USP7 is a deubiquitinating enzyme also known as HAUSP (herpesvirus-associated ubiquitin-specific protease). USP7 contains four structural domains, at least three of which are responsible for binding to other proteins [46]. Like USP2a, USP7 is involved in the complex regulation of the p53 tumor suppressor through its interactions with p53, Mdm2 and Mdmx. USP7 also interacts with the viral proteins EBNA1 and ICP0.

p53, Mdm2 and Mdmx

USP7 was identified by mass spectrometry analysis of affinity-purified p53-associated factors [30]. USP7 was found to bind directly to p53 in vitro as well as in vivo via co-immunoprecipitation assays [30]. USP7 was found to regulate p53 levels through its deubiquitinating activity as part of a feedback loop involving the E3 ligase enzyme Mdm2, which is also a substrate for USP7 deubiquitinase activity [47, 48]. While USP7 can directly regulate p53 levels, these levels can also be regulated by the DUB USP2a. By regulating p53 levels through their deubiquitinating activities, USP7 and USP2a may contribute to cancer pathogenesis and therapeutic strategies that target these p53-specific DUBs may become important as cancer treatments [29].

USP7 can directly bind Mdm2 in vitro [48]. The DUB stabilizes Mdm2 in a p53-independent manner, providing an interesting feedback loop in p53 regulation [48, 49]. Notably, USP7 is required for Mdm2 stability in normal cells and, in USP7-ablated cells, self-ubiquitinated Mdm2 becomes extremely unstable, leading indirectly to p53 activation [48].

New evidence supports a role for USP7 in the regulation of Mdmx stability as well [50]. Mdmx is an Mdm2 family member that is also involved in p53 degradation and contains a RING domain but does not appear to have any ubiquitin E3 ligase activity [51, 52]. USP7 was shown to bind directly to and deubiquitinate Mdmx in vitro and in vivo [50].

EBNA1 and ICP0

EBNA1 (The Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen-1) interacts in the N-terminus of USP7, the same domain that interacts with p53 and the two proteins appear to compete for the same binding site [46]. By disrupting the p53-USP7 interaction, EBNA1 would be expected to promote cell-cycle progression and prevent apoptosis, which could be important for the host cell immortalization typical of EBV [46]. Using an in vitro affinity column assay and in vivo tandem affinity purification (TAP)-tagging to profile cellular protein interactions with EBNA1, USP7 was found to specifically interact with EBNA1 in both assays [53]. Furthermore, purified USP7 was shown to deconjugate ubiquitin from EBNA1 [46].

The C-terminus of USP7 binds another viral protein, the ICP0 protein of herpes simplex type 1 [46]. The ICP0 protein has ubiquitin E3 ligase activity in vitro and is important for induction of the lytic infectious cycle [54]. The interaction of viral proteins with USP7 suggests that some viruses may influence cellular events by sequestering or altering the activity of USP7 [46].

USP8/UBPY

USP8 is an Src homology 3 (SH3)-binding protein [55]. It was first identified as a protein whose levels accumulate upon growth stimulation of human fibroblast cells and decrease in response to growth arrest [56]. USP8 is implicated in ubiquitin remodeling, regulation of epidermal growth factor receptors, clathrin-mediated internalization, endosomal sorting, and the control of receptor tyrosine kinases in vivo [18, 57]. The USP8 protein has several domains including a rhodanese-homology domain (RD) and the cysteine and histidine boxes of the catalytic core [55]. USP8 also interacts with the HRS-STAM complex. The biological importance of USP8 was revealed by studies using Cre-loxP-mediated gene targeting in mice showing that lack of USP8 results in embryonic lethality [57].

SH3 domain containing proteins

Src homology 3 (SH3) domains are protein-interaction modules that are involved in signal transduction networks [58]. USP8 has been shown to interact with the SH3 domain of the signal transducing adaptor molecule-2 (STAM2). Upon binding to STAM2, USP8’s DUB activity appears to be activated resulting in the deubiquitination of STAM2 and its protection from proteasomal-mediated degradation [55, 59]. The crystal structure of the STAM2 SH3 domain in complex with the USP8 binding peptide was solved and the interactions observed explained why the binding was tight, with a dissociation constant (Kd) of 27μ9]. STAM2, in cooperation with the protein Hrs, functions in the endocytic degradation pathway of growth factor-receptor complexes and USP8 may indirectly regulate this process [60].

Another Hrs binding protein with an SH3 domain is Hbp (Hrs-binding protein). Using full-length Hbp as a probe in a far Western assay with a mouse liver cDNA expression library, researchers identified a USP8 cDNA clone that encoded a Hbp binding protein. Mouse USP8 shares approximately 80% amino acid sequence identity with human USP8 and it is likely that human USP8 would also bind this protein [55].

Row et al., 2007 identified and characterized a Microtubule Interacting and Transport (MIT) domain at the N-terminus of USP8 and showed that, like other MIT domain-containing proteins (such as AMSH, which is discussed later in this review), it bound CHMP proteins [61]. CHMP proteins are involved in the formation of multivesicular bodies and the degradation of internalized transmembrane receptor proteins [62]. There are several CHMP proteins and the MIT domain of USP8 was found to interact with CHMP1A, 1B, 4C and 7. The USP8-CHAMP1B interaction was later shown to be direct by using bacterially-expressed proteins in vitro and then confirmed in vivo by a co-immunoprecipitation assay.

Nrdp1

USP8 was first identified in an affinity purification assay of proteins that bound to Nrdp1 (neuregulin receptor degradation protein-1). Nrdp1 is a RING finger ubiquitin E3 ligase involved in ligand-stimulated epidermal growth factor receptor down-regulation [63] and has been implicated in the degradation of the inhibitor-of-apoptosis protein BRUCE [64]. USP8 and Nrdp1 were shown to interact in vitro via affinity chromatography experiments with cell lysates from C2C12 myotubes and the two proteins were also shown to interact in vivo by co-immunoprecipitation experiments [63]. The study found that the rhodanese and catalytic domains of USP8 mediate its interaction with Nrdp1 [63]. The crystal structure of the rhodanese domain of USP8 in complex with Nrdp1 was solved and revealed that the USP8-Nrdp1 interaction appeared to be dominated by salt bridges [18]. The biological significance of the USP8-Nrdp1 interaction is at least partially due to its effect on EGFR regulation. Nrdp1 catalyzes the ubiquitination of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR/ErbB) family of receptor tyrosine kinases [65, 66]. Nrdp1 not only associates with the ErbB3 receptor and stimulates its ubiquitination and degradation by proteasomes but also promotes its own ubiquitination and subsequent proteasome-mediated degradation [63]. Deubiquitination activity of USP8 is required for Nrdp1 stability. By stabilizing Nrdp1, USP8 indirectly regulates ErbB3 stability and therefore may represent an attractive target for cancer therapy [66].

14-3-3epsilon

USP8 was identified by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis of a pull down assay designed to find 14-3-3epsilon interacting partners from primary mouse tissue [67]. 14-3-3 protein family members execute diverse regulatory roles, primarily via interactions with proteins phosphorylated in a conserved sequence motif [68]. The study found that phosphorylation of USP8 at serine 680 was essential for its interaction with 14-3-3epsilon and for retaining/stabilizing USP8 in the cytosol [67]. The USP8-14-3-3 interaction was also confirmed in three other studies: one used tandem affinity purification (TAP) coupled with multidimensional protein identification technology [69]; another used 14-3-3 affinity chromatography with HeLa cell extracts and found that the USP8-14-3-3 interaction appears to occur in a cell-cycle dependent manner [70]; 14-3-3 epsilon, gamma, and zeta were identified as USP8-binding proteins using co-immunoprecipitation followed by mass spectrometric analysis [71]. The latter study showed that 14-3-3epsilon inhibited the activity of USP8 in vitro. While the biological significance of the USP8/14-3-3epsilon interaction remains unknown, one hypothesis is that USP8 deubiquitinates and stabilizes negative regulators of the cell-cycle that also bind 14-3-3 isoforms such as the tumor suppressors neurofibromin (NF1) and the Tuberous Sclerosis Complex proteins 1 and 2 (TSC1 and 2) which have been found to interact with 14-3-3epsilon and are known to undergo ubiquitin-dependent degradation [67]. Another hypothesis is that USP8 is catalytically inhibited in a phosphorylation-dependent manner by 14-3-3 proteins during the interphase stage of the cell-cycle, and this regulation is reversed in the M phase [71].

USP9

Fat facets/ubiquitin specific protease-9 (USP9) is a DUB that has been implicated in development, probably due to a specific role in regulating Delta and Notch signaling. The mouse and Drosophila orthologs of USP9 are essential for early embryonic development [72].

AMPK Kinases

USP9 was identified in a modified tandem affinity purification strategy to find proteins that interact with AMP-activated (AMPK) protein kinases in 293 cells. The study found that USP9 was associated with two AMPK kinases MARK4 and NUAK1 [73]. MARK proteins have an ubiquitin-associated (UBA) domain and regulate anterior-posterior cell polarity development at the one-cell stage of embryonic development in C. elegans and Drosophila [74, 75].

Mind bomb 1 (Mib1)

Mib1 (Mind bomb 1) is an ubiquitin E3 ligase enzyme found in the post synaptic density of neurons. Using a GST-affinity purification method with rat-brain lysates followed by tandem mass spectrometry, the USP9 ortholog was identified as an interacting protein [76].

VAS

Vasa (VAS) protein is a DEAD-box RNA helicase that is essential maternally for posterior patterning and germ cell function in Drosophila [77, 78]. VAS-containing complexes with USP9 were cross-linked, isolated by a tandem immunoprecipitation approach and identified by mass spectrometry [77]. Using this method, the USP9 ortholog was identified as a major VAS-binding protein from both embryo and ovarian extracts.

Epsin/Lqf

Liquid facets (Lqf), a homolog of the vertebrate endocytic protein epsin, was found to associate with the Drosophila ortholog of USP9 [79]. In this study the USP9 ortholog was identified in an anti-Lqf immunoprecipitate from embryo extracts. The study also showed that Lqf was ubiquitinated in vivo and deubiquitinated by Faf (the Drosophila ortholog of USP9). These results are consistent with previous genetic evidence implicating Lqf as a candidate for the key substrate of the USP9 ortholog [80].

USP10/UBP3

Increased expression of USP10 has been associated with the disease glioblastoma multiforme [81]. At the cellular level, USP10 and its yeast homolog, UBP3, have been implicated in regulating anterograde and retrograde traffic between the golgi and endoplasmic reticulum.

G3BP/Bre5

A yeast 2-hybrid assay using USP10 as bait isolated a cDNA clone encoding a protein called RasGAP SH3 domain binding protein (G3BP). This protein was shown to specifically interact with USP10 but not with other USP baits tested. The interaction was validated by performing the reverse 2-hybrid assay, by in vitro binding and in vivo co-immunoprecipitation assays in human cells. The two proteins appeared to co-purify as part of a large macromolecular complex that contains other proteins including perhaps a USP10 substrate [82].

Interestingly, an interaction between the yeast homologues of USP10 and G3BP (UBP3 and Bre5, respectively) has also been detected in a high-throughput 2-hybrid analysis of the yeast genome, thereby suggesting a role for the DUB in golgi to endoplasmic reticulum retrograde transport [83]. In yeast, UBP3 has been shown to regulate gene silencing through its interaction with SIR4 and contribute to the cellular response to DNA damage [84, 85].

The biological function of USP10 remains unknown. Soncini et al., 2007 showed that although G3BP does not appear to be a substrate of USP10 it appears to inhibit the ability of USP10 to disassemble ubiquitin chains [82]. Ubiquitin chain disassembly is not only important for the regeneration of free ubiquitin from chains released before proteasomal degradation, but also for generation of free ubiquitin subunits from the synthesized linear polyubiquitin chains or from ubiquitin fusion proteins [86]. On the other hand, it appears that binding of the yeast homologues is required for the deubiquitination of Sec23, a substrate for Bre5–UBP3 [87].

Androgen Receptor

USP10 was identified as part of DNA-bound androgen receptor (AR) complexes purified from nuclear extracts of PC-3 cells stably expressing the AR in vivo [88]. This interaction was then confirmed in vitro by GST pull-down assays. USP10 appeared to modulate AR function. Cell-based trans-activation assays in PC-3 cells stably expressing the AR revealed that overexpression of wild-type USP10, but not of an enzymatically inactive form, stimulated AR activation of reporter constructs harboring selective androgen response elements (AREs), non-selective steroid response elements (SREs) or the mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) promoter. Conversely, knock-down of USP10 expression was found to impair the MMTV response to androgen [88].

USP11

USP11 positively regulates IkappaB kinase alpha (IKKalpha). In response to TNFalpha, USP11 functions as an upstream regulator of IKKalpha, which in turn stabilizes and activates p53 [89].

RelB complex

Using a tandem affinity purification (TAP) strategy to isolate complexes from control and TNFalpha-stimulated HEK293 cells, USP11 was identified in a complex including components of the TNFalpha/NF-kB signaling pathway [90]. RelB is a transcription factor that forms a heterodimeric complex with p52 during NF-kB signaling [91, 92]. Using TAP-tagged RelB, USP11 was specifically found in a complex that included the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex, the histone deacetylase 6 and the lymphoid transcription factor REQ [90].

BRCA2

USP11 was identified using an immunopurification-mass spectrometry approach to find novel proteins that associate with the BRCA2 gene product [93]. The study showed that in the cellular response to MMC-induced DNA damage, BRCA2 appears to be regulated by ubiquitination that targets it for degradation at the proteasome. They showed that the two proteins interact in vivo but whether this interaction was direct or mediated by other members of a multi-protein complex, remains to be resolved. They found that overexpression of USP11, but not a catalytically inactive USP11 mutant, could deubiquitinate BRCA2. BRCA2 functions in the repair of DNA double-strand breaks by homologous recombination [94] and is an important protein in human disease because individuals carrying a germ line mutation in the BRCA2 gene are predisposed to breast, ovarian, and other types of cancer [93].

USP14/UBP6

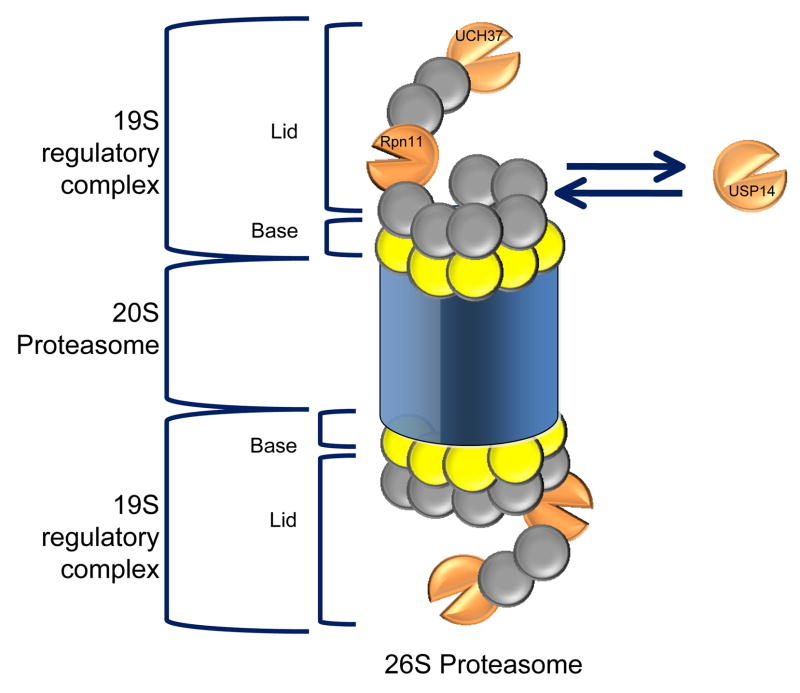

USP14 is a DUB that binds the Rpn1 subunit of the proteasome through its N-terminal ubiquitin-like (UBL) domain [95]. Other studies have implicated USP14 in colorectal cancer [96] and ataxia in mice [97].

26S Proteasome

Unlike the Rpn11 and UCH37 DUBs, which are two constituent proteasome subunits, the USP14 interaction with the proteasome is reversible [98]. The catalytic activity of USP14 is activated upon specific association with the 26S proteasome. The crystal structures of the 45-kDa catalytic domain of USP14 in isolation and in a complex with ubiquitin aldehyde revealed details about the significant conformational change that allows access of the ubiquitin C-terminus to the active site [17]. USP14 appears to function in the maintenance of cellular levels of monomeric ubiquitin in mammalian cells, and alterations in the levels of ubiquitin may contribute to neurological disease [99].

USP15/UBP12

USP15 is a zinc-finger-containing DUB that has been shown to function in the cleavage of isopeptide bonds of polyubiquitin chains as well as in the cleavage of the ubiquitin–proline bond, a property previously thought to be unique to USP4, a protein with which USP15 shares significant sequence identity [100, 101]

COP9 signalosome

The COP9 signalosome (CSN) is a conserved protein complex that harbors deneddylating activity and contains subunits similar to the 26S proteasome lid [102]. It reverses the conjugation of the ubiquitin-like protein Nedd8 to cullins, a modification necessary for optimal ubiquitination by the SCF ubiquitin ligases [103]. CSN activity is involved in the regulation of the ubiquitin proteasome system, DNA repair, cell-cycle regulation and development [104–106]. The biological role of the USP15/CSN complex may be in the protection of cullin-RING-ubiquitin ligases from auto-ubiquitination [102]. Interestingly, the USP15 ortholog in Saccharomyces pombe (UBP12) also binds the CSN [107].

USP20/VDU2

USP20 (also called VHL-interacting deubiquitinating enzyme 2 (VDU2)) is a DUB that shares approximately 59% identity with USP33/VDU1 (see below) [108]. Both proteins have been shown to interact with the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor ubiquitin E3 ligase enzyme [109, 110].

von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) and HIF-1alpha

USP20 was shown to interact with the VHL beta-domain and also be ubiquitinated and degraded in a VHL-dependent manner. USP20 is unique from USP33 (another DUB that also interacts with VHL) in that it also interacts with hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1alpha. HIF-1alpha is the primary transcriptional response factor for cellular adaptation to hypoxic conditions and is ubiquitinated and degraded through the VHL pathway [111]. The action of USP20 may be to deubiquitinate HIF-1alpha, resulting in its stabilization and neovascalaturization [110].

USP 22/UBP8

USP22 is a DUB that has been postulated to play a critical role in cell-cycle progression [112]. USP22 is encoded by a gene in the 11 gene Polycomb/stem cell signature, members of which play well documented roles in cancer [113].

SAGA complex

The SAGA (Spt–Ada–Gcn5–acetyltransferase) complex is a multi-protein histone acetyltransferase transcriptional cofactor complex that is required for the function of sequence-specific transcription activators in eukaryotes [114]. USP22 was identified as a subunit of the human SAGA transcriptional cofactor complex [112]. In this study, USP22 was affinity purified under non-denaturing conditions from nuclear extracts of H1299 human lung cancer cells stably expressing FLAG epitope-tagged USP22. Tandem mass spectrometry analysis of the USP22 complexes revealed that most contained components of the SAGA complex. The yeast homolog of USP22 (UBP8) has also been shown to be a constitutive subunit of the yeast SAGA complex and to be required for SAGA-dependent transcription at some yeast genes [115, 116]. USP22 appears to play a functional role in the human SAGA complex by deubiquitinating histone H2B and as such may regulate gene transcription [112].

USP28

USP28 was found to regulate the Chk2-p53-PUMA pathway, a major regulator of DNA-damage-induced apoptosis in response to double-strand breaks in vivo [117]. The DUB is also required for maintaining stability of the MYC oncoprotein through its interaction with FBW7alpha [118].

FBW7alpha

USP28 was found to interact with FBW7alpha, an F-box protein that is part of an SCF-type ubiquitin ligase [117]. This ligase degrades proto-oncogenes in cellular growth and division pathways, including MYC, cyclin E, Notch and JUN. Using a co-immunoprecipitation assay, USP28 and FBW7alpha were shown to form a ternary complex with the MYC protein in vivo and to regulate MYC stability [119]. This study found that USP28 was required for MYC stability in human tumor cells and the stabilizing effect of USP28 was dependant on both its catalytic activity and its ability to reverse FBW7-mediated ubiquitination. While it is not known if this mechanism pertains to all the FBW7alpha substrates, this interaction is clearly important in the regulation of MYC, an oncogenic transcription factor that is involved in many human tumors [120].

USP33/VDU1

USP33 (also known as VHL-interacting deubiquitinating enzyme 1 (VDU1)) was originally identified as a protein partner of the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) protein [109]. VHL is a tumor suppressor ubiquitin E3 ligase enzyme and mutations in the VHL gene result in the hereditary cancer syndrome called von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease. The DUB interacts with both VHL as well as the type 2 iodothyronine deiodinase (D2).

von Hippel-Lindau (VHL)

In a study by Li et al., (2002) [109], USP33 was identified in a yeast 2-hybrid assay using VHL as bait. The two proteins were later shown to interact directly in vitro and in vivo. The USP33-VHL interaction may have clinical significance because naturally occurring mutations that have been found in the beta-domain of USP33 disrupt the interaction between the two proteins. USP33 was found to be ubiquitinated in a VHL-dependent manner which targeted it for proteasomal degradation, and VHL mutations that disrupt the protein’s interaction with the DUB abrogated USP33 ubiquitination. The findings from this study imply that USP33 is a downstream target for ubiquitination and degradation by the VHL E3 ligase.

Type 2 iodothyronine deiodinase (D2)

USP33 was also identified in a yeast 2-hybrid screen of a human-brain library using the type 2 iodothyronine deiodinase (D2) as bait [121]. The study found that D2 interacted with both USP33 and USP20/VDU2. The USP33-D2 interaction was then confirmed in mammalian cells. USP33 was found to co-localize with D2 in the endoplasmic reticulum, and co-expression prolonged the half-life and activity of D2 by deubiquitination. USP33 is found to be increased in brown adipocytes by norepinephrine or cold exposure, further amplifying the increase in D2 activity that results from catecholamine-stimulated de novo synthesis. Thus, through its interaction with and subsequent degradation of D2, USP33 is believed to regulate thyroid hormone activation.

CYLD

The CYLD gene encodes a tumor suppressor protein that is mutated in familial cylindromatosis [122]. The CYLD DUB functions in the deconjugation of lysine-63 linked polyubiquitin chains from target proteins and is involved in the negative regulation of NF-kB signaling [123–127].

NF-kB Pathway Proteins

CYLD was found to interact with NEMO (also known as IKKgamma) via a yeast 2-hybrid assay [124, 126]. NEMO is a component of the IkappaB kinase (IKK) complex, which functions in the phosphorylation of the NF-kB inhibitor (IkB) and subsequent release of the NF-kB transcription factor into the nucleus where it acts as a transcription factor.

CYLD also interacts directly with tumor-necrosis factor receptor (TNFR)-associated factor 2 (TRAF2), an adaptor molecule involved in signaling by members of the family of TNF/nerve growth factor receptors [124]. The inhibition of NF-kB activation by CYLD is mediated, at least in part, by the deubiquitination and inactivation of TRAF2 and, to a lesser extent, TRAF6 [126].

The clinical significance of the interactions with NEMO and TRAF2 and the subsequent regulation of the NF-kB pathway lie in the effect of CYLD on cancer pathogenesis. Mutations within the DUB domain of CYLD are found in cylindromatosis patients. Because they impair the deubiquitination of NEMO, TRAF2 and TRAF6, these mutations may lead to the enhanced activation of NF-kB, thereby contributing to tumor pathogenesis [127].

Full-length CYLD was also shown to interact the RING finger protein TRIP (TRAF-interacting protein) through a yeast 2-hybrid screen using an HaCaT cDNA library [125]. This study confirmed the interaction of CYLD with the C-terminal domain of TRIP by far Western analysis and co-immunoprecipitations in mammalian cells.

Bcl-3

More recently, CYLD has been shown to regulate Bcl-3 [128]. Bcl-3 is a constitutively nuclear protein, has transcriptional activation domains and can associate with p50 and p52 homodimers to act as a transcriptional co-activator [129]. Bcl-3 and CYLD were shown to interact specifically in vitro via a yeast 2-hybrid assay and in vivo via co-immunoprecipitation analysis. This study showed that in response to TPA or UV light, CYLD translocates from the cytoplasm to the perinuclear region, where it binds to and deubiquitinates Bcl-3, thereby preventing nuclear accumulation of Bcl-3 and p50-Bcl-3- or p52-Bcl-3-dependent proliferation.

B. Ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolases (UCH)

UCL-L1/PGP9.5

Mutations of the UCH-L1 gene and alterations of its proteins’ activity have been found to associate with several neurodegenerative disorders, including Parkinson’s, Huntington’s and Alzheimer’s diseases [11]. UCH-L1 has also been found to be highly expressed in primary lung cancers and lung cancer cell lines, suggesting that it may play a role in lung cancer tumorigenesis [130].

JAB1 (CSN subunit)

Using UCH-L1 as bait in a yeast 2-hybrid assay with an expression cDNA library derived from fetal brain, the DUB was shown to interact with JAB1 (Jun activation domain-binding protein 1) [131]. JAB1 is a subunit of the COP9 signalosome (CSN) complex and mediates numerous cellular processes, including the cytoplasmic transportation of cyclin-dependent kinase (cdk) inhibitor p27 (Kip1) and its subsequent proteasome-mediated degradation [103]. The study confirmed that the two proteins interact in vivo via co-immunoprecipitation. This interaction appeared to be functionally important because both proteins appeared to be part of a heteromeric complex containing p27 in the nucleus of lung cancer cells. UCH-L1 may contribute to p27 degradation via its interaction and nuclear translocation with JAB1 [131].

UCH2/UCH -L5/UCH37

UCH37 functions by processively removing ubiquitin from the distant end of polyubiquitin chains and has been suggested to serve an “editing” function that can rescue poorly ubiquitinated proteins from a proteolytic fate [98]. The best characterized role of UCH37 is through its interaction with the proteasome subunits S14 and Adrm1. It also interacts with UIP1 and Smad proteins.

S14 and UIP1

By using a yeast 2-hybrid screen, two proteins that interacted with UCH37 were identified: S14, a subunit of the 19S regulatory particle of the proteasome, and UIP1 (UCH37 interacting protein 1) [132]. These interactions were then confirmed by in vitro binding assays and in vivo co-immunoprecipitation analyses. The study found that the C-terminus of UCH37 is essential for the interaction with S14 or UIP1. Support for the fact that the two proteins occupy the same binding site came from the observation that UIP1 blocked the interaction between UCH37 and S14 in vitro [132].

Adrm1 (human Rpn13)

UCH37 was found to bind to the proteasome through Adrm1, a previously unrecognized ortholog of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rpn13, which in turn is bound to the S1 (also known as Rpn2) subunit of the 19S complex [133]. Binding of Adrm1 to UCH37 relieved auto-inhibition by the UCH domain and activated its deubiquitination activity [133].

Smad7

A novel specific interaction between Smad transcription factors and UCH37 was identified [134]. Using GST pull down assays, UCH37 was shown to specifically interact with Smad7 in vitro and in vivo via co-immunoprecipitation with HA-tagged UCH37 in transfected HEK-293 cells. UCH37 displayed weaker associations with Smad2 and Smad3. The UCH37-interaction region was distinct from the motif on Smad7 that interacts with Smurf (Smad-ubiquitin regulatory factors) ubiquitin ligases. This study demonstrated that UCH37 may have biological roles distinct from its role at the proteasome [135]. The study hypothesized that Smad7 could act as an adaptor to recruit UCH37 to the type I TGF-beta receptor and showed that UCH37 dramatically up-regulates TGF-beta-dependent gene expression by deubiquitinating and stabilizing the type I TGF-beta receptor [134].

BAP1 (BRCA1-asscociated Protein 1)

The N-terminus of BAP1 has a UCH domain that shows high sequence homology to other members of the UCH family. BAP1 is unique, however, in that it also harbors a large C-terminal extension that appears to be important in substrate recognition.

BRCA1

BAP1 is a putative tumor suppressor that was first discovered in a yeast 2-hybrid screen to identify proteins that interact with the RING finger domain of the breast cancer susceptibility gene product, BRCA1 [9, 136]. In this study, BAP1 was shown to interact with the wild-type BRCA1 RING finger domain but not with cancer-associated RING finger mutants. Furthermore, the two proteins appeared to interact in a biologically significant manner because BAP1 augmented the growth suppressive properties of BRCA1 in breast cancer cells.

C. Otubain proteases (OTU)

A20

A20 is a tumor necrosis factor (TNF)- and interleukin 1 (IL-1)-inducible zinc finger protein that has been characterized as an inhibitor of both NF-kB activation and apoptosis [137, 138]. A20 is unique in that it contains both deubiquitinase activity as well as ubiquitin E3 ligase activity [139, 140]. A20 inhibits NF-kB signaling through various pathways including those involving TNF receptor-associated proteins, TNF receptor-associated death domain protein (TRADD), receptor interacting protein (RIP), and TNF receptor-associated factor 2 (TRAF2) [138].

NF-kB Pathway Proteins

The N-terminal region of A20 (that lacks the zinc finger structures) binds to TRAF2 complexes [141]. A20 was identified in a yeast 2-hybrid assay to search for TRAF2-interacting proteins and this interaction was confirmed in vivo [141]. Mutational analysis revealed that the N-terminal half of A20 interacts with the conserved TRAF domain of both TRAF1 and TRAF2. TRAF2 functions in the activation of the NF-kB transcription factor triggered by TNF and the CD40 ligand [142]. Co-transfection experiments revealed that A20 blocked TRAF2-mediated NF-kB activation [141].

The C-terminal region (containing the functional zinc finger structures) mediates A20 dimerization and binding to several other proteins that might be involved in the inhibition of NF-kB activation and apoptosis by A20 [141]. The C-terminal region has been found to interact with Receptor Interacting Protein (RIP) and to a novel protein, ABIN (A20 binding inhibitor of NF-kB activation) [138].

Cezanne

Cezanne (cellular zinc finger anti-NF-kappa B) is an OTU domain-containing protein that, like A20, is an inhibitor of the NF-kB signaling pathway [143]. Cezanne may have some functions that are distinct from A20. While A20 does not have a global deubiquitinating activity and does not participate in ubiquitin recycling, expression of Cezanne has been shown to prevent the buildup of polyubiquitinated cellular proteins in cultured cells in response to the proteasome inhibitor MG132 [144].

TRAF6

Cezanne was found to interact with TRAF6 via co-immunoprecipitation studies in vivo. In contrast, reporter gene experiments revealed a specific ability of Cezanne to down-regulate NF-kB. It is likely, therefore, that Cezanne participates in the regulation of inflammatory processes [143].

VCIP135

VCIP135 (VCP[p97]/p47 complex–interacting protein, p135) is a deubiquitinating enzyme that was originally identified as an essential factor for p97/p47-mediated membrane fusion [145]. VCIP135 contains a region with homology to the catalytic domains of the deubiquitinating enzymes, Cezanne and A20 [146]. Cdc48/p97 (also called VCP for valosin-containing protein) is an AAA-ATPase which, together with its adaptor p47, regulates several membrane fusion events, including reassembly of Golgi cisternae after mitosis [146].

Cdc48/p97 complex

Using affinity chromatography, VCIP135 was found to bind to the p97/p47/syntaxin5 complex [145]. The study used a fragment of p47 (containing only one (residues 171-270) of the p97-binding sites) immobilized onto a bead, incubated it with rat liver cytosol and identified interacting proteins by microsequencing via electrospray mass spectrometry. This study further found that VCIP135 dissociates the p97/p47/syntaxin5 complex via p97 catalyzed ATP hydrolysis. In addition, by microinjection of antibodies to VCIP135 and p47 into living cells they showed that VCIP135 and p47 are required for Golgi assembly and ER network formation in vivo [145]. Other studies have confirmed that the p97/p47/VCIP135 complex is required for cell-cycle-dependent reformation of the ER network and that p97-p47-mediated reassembly of Golgi cisternae requires the deubiquitinating activity of VCIP135 [146, 147].

D. Machado-Joseph disease proteases (MJD)

Ataxin-3 (AT3)

Ataxin-3 is the main protein affected in the disease spinocerebellar ataxia type 3, a human neurodegenerative disease resulting from polyglutamine tract expansion [148]. The protein contains an N-terminal Josephin domain followed by tandem ubiquitin-interacting motifs (UIMs) and a polyglutamine stretch.

PLIC-1

Ataxin-3 was found to interact with the ubiquitin-like domain (UBL) of PLIC-1 (protein linking IAP to the cytoskeleton). PLIC-1 is an ubiquitin-like protein that binds to several ubiquitin-interacting motif (UIM)-containing proteins including Ataxin-3 [149]. In this study glutathione S-transferase (GST) pull-downs showed that Myc-tagged Ataxin-3 exogenously expressed in cultured cells interacted with GST-fused PLIC-1 UBL domain in vitro. Furthermore, the study showed that the two proteins co-localize in small punctuate structures in BHK cells [149].

HDAC3

Another protein that interacts with Ataxin-3 is HDAC3. Ataxin-3 was found to bind to target DNA sequences in specific chromatin regions of the matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) gene promoter and repress transcription by recruitment of histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3) and the nuclear receptor co-repressor (NCoR) [150]. Both normal (Q23) and expanded (Q70) human full-length Ataxin-3 physiologically interacted with HDAC3 and NCoR in a SCA3 rat cell line and human pons tissue. The interaction between Ataxin-3 and HDAC3 is thought to result in the deacetylation of histones and reduce binding of the transcription factor GATA-2 to target regions of the MMP-2 promoter.

Ataxin-3 has also been shown to interact with the major histone acetyltransferases cAMP-response-element binding protein (CREB)-binding protein, p300, and p300/CREB-binding protein-associated factor in vitro and in vivo and inhibit transcription by these co-activators [151].

II. JAMM (JAB1/MPN/Mov34) METALLOPROTEASES

AMSH

AMSH (Associated molecule with SH3 domain of STAM) is a zinc-containing endosomal DUB that can limit EGF receptor down-regulation [152]. AMSH was found to interact with the SH3 domain of STAM (signal transducing adaptor molecule), a component of the multivesicular body (MVB) pathway [153] as well as components of the ESCRT-III complex [154].

STAM and Clathrin

STAM is a protein that regulates receptor sorting at the endosome [152]. Using an in vitro binding assay, GST-AMSH was found to interact with purified His6-tagged STAM and this interaction required the SH3 domain of STAM but not the ubiquitin-interacting motif (UIM) domain [153]. This study also identified clathrin as a novel binding partner of AMSH and confirmed the interaction in vivo via co-immunoprecipitation experiments from transiently transfected HEK293T cells. Another study found that the AMSH–STAM interaction enhanced the deubiquitination of STAM-bound K63-linked ubiquitins. The study showed that STAM functions by binding to ubiquitinated substrates and holding the ubiquitin molecules in place for deubiquitination by AMSH [155].

ESCRT-III complex

AMSH has also been shown to interact with subunits of the endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT-III). These include CHMP1A, CHMP1B, CHMP2A, CHMP3, CHMP4A and CHMP4B. These interactions have been observed via yeast 2-hybrid assays, however only the CHMP3, 1A, 1B and 2A interactions have been confirmed by alternative protein interaction assays [62, 153, 154]. These interactions are consistent with a role of AMSH in the deubiquitination of the endosomal cargo preceding lysosomal degradation. It has been suggest that both the DUB activity of AMSH and its CHMP3-binding ability are required to clear ubiquitinated cargo from endosomes [154][156].

Rpn11/POH1

Rpn11 is a JAMM metalloprotease that appears to be required for proper proteasomal processing of ubiquitinated substrates. Rpn11 (along with UCH37) is a constituent component of the proteasome [98]. Its enzymatic activity has only been detected in context with the 19S or 26S proteasome complexes.

26S Proteasome

Rpn11 is one of four DUBs associated with the 19S regulatory core of the proteasome and is the most conserved lid component [157]. The biological significance of the interaction can be inferred from studies showing that RNA interference (RNAi) of Rpn11 decreases cellular proteasome activity via disrupted 26S proteasome assembly, and inhibits cellular protein degradation [98].

III. PROTEASOME-BOUND DUBs

The 26S proteasome is an important component for the maintenance of cellular homeostasis. It is composed of different sub-complexes, a 20S core proteasome harboring the proteolytic active sites hidden within its barrel-like structure and two 19S caps that execute regulatory functions [158]. The 19S regulatory complex can be further subdivided into two sub-complexes, the base and the lid [159]. Cumulative evidence points to a partitioning of proteasome action between proteolysis and deubiquitination [160]. Ubiquitinated proteins that are targeted to the 26S proteasome for degradation first bind–possibly via the proteasome subunit Rpt2–and are subsequently deubiquitinated, unfolded by the base and degraded inside the 20S core [157].

The key proteasome-associated DUBs include 1) Rpn11/POH1, 2) UCH37/UCH2 and 3) UBP6/USP14 [160]. Rpn11 and UCH37 are two constituent proteasome subunits, while the USP14 interaction is reversible [98]. Structural and biochemical studies on isolated DUBs have shown that many exist in conformations that require substrate binding [15, 16] or association with binding partners [17] in order to achieve the active conformation. The idea that most DUBs must bind their target protein in a conjugate or associate with a macromolecular complex [1] in order to carry out their function can be further illustrated by studying the proteasome-associated DUBs. For example, the deubiquitinating activity of USP14 increases upon binding to the proteasome, suggesting that the proteasome is a physiological site of USP14 function [161]. Also, the enzymatic activity of Rpn11 has only been detected in context with the 19S or 26S proteasome complexes [98]. This property of DUBs may be intended for preventing non-specific deubiquitination of cellular proteins, which could lead to a disease state.

A mutual requirement appears to exist between the proteasome and the DUBs that associate with it. On the one hand, as we have previously mentioned in this review, some DUBs require binding to the proteasome in order to function. Conversely, it seems that the proteasome also requires its associated DUBs (Rpn11 plus either UCH37 or USP14) for proper processing of ubiquitinated substrates.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

References

- 1.Amerik AY, Hochstrasser M. Mechanism and function of deubiquitinating enzymes. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2004;1695:189–207. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilkinson KD. Ubiquitin: a Nobel protein. Cell. 2004;119:741–745. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pickart CM. Mechanisms underlying ubiquitination. Annual review of biochemistry. 2001;70:503–533. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jentsch S, Seufert W, Hauser HP. Genetic analysis of the ubiquitin system. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 1991;1089:127–139. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(91)90001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilkinson KD. Roles of ubiquitinylation in proteolysis and cellular regulation. Annual review of nutrition. 1995;15:161–189. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.15.070195.001113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sigismund S, Polo S, Di Fiore PP. Signaling through monoubiquitination. Current topics in microbiology and immunology. 2004;286:149–185. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-69494-6_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Welchman RL, Gordon C, Mayer RJ. Ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins as multifunctional signals. Nature reviews. 2005;6:599–609. doi: 10.1038/nrm1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pickart CM, Fushman D. Polyubiquitin chains: polymeric protein signals. Current opinion in chemical biology. 2004;8:610–616. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jensen DE, Proctor M, Marquis ST, Gardner HP, Ha SI, Chodosh LA, Ishov AM, Tommerup N, Vissing H, Sekido Y, Minna J, Borodovsky A, Schultz DC, Wilkinson KD, Maul GG, Barlev N, Berger SL, Prendergast GC, Rauscher FJ., 3rd BAP1: a novel ubiquitin hydrolase which binds to the BRCA1 RING finger and enhances BRCA1-mediated cell growth suppression. Oncogene. 1998;16:1097–1112. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nijman SM, Luna-Vargas MP, Velds A, Brummelkamp TR, Dirac AM, Sixma TK, Bernards R. A genomic and functional inventory of deubiquitinating enzymes. Cell. 2005;123:773–786. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gong B, Leznik E. The role of ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase L1 in neurodegenerative disorders. Drug news & perspectives. 2007;20:365–370. doi: 10.1358/dnp.2007.20.6.1138160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Donato F, Chan EK, Askanase AD, Miranda-Carus M, Buyon JP. Interaction between 52 kDa SSA/Ro and deubiquitinating enzyme UnpEL: a clue to function. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2001;33:924–934. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(01)00055-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sulea T, Lindner HA, Menard R. Structural aspects of recently discovered viral deubiquitinating activities. Biological chemistry. 2006;387:853–862. doi: 10.1515/BC.2006.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Catic A, Misaghi S, Korbel GA, Ploegh HL. ElaD, a Deubiquitinating protease expressed by E. coli. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e381. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu M, Li P, Li M, Li W, Yao T, Wu JW, Gu W, Cohen RE, Shi Y. Crystal structure of a UBP-family deubiquitinating enzyme in isolation and in complex with ubiquitin aldehyde. Cell. 2002;111:1041–1054. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01199-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnston SC, Riddle SM, Cohen RE, Hill CP. Structural basis for the specificity of ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolases. The EMBO journal. 1999;18:3877–3887. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.14.3877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu M, Li P, Song L, Jeffrey PD, Chenova TA, Wilkinson KD, Cohen RE, Shi Y. Structure and mechanisms of the proteasome-associated deubiquitinating enzyme USP14. The EMBO journal. 2005;24:3747–3756. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Avvakumov GV, Walker JR, Xue S, Finerty PJ, Jr, Mackenzie F, Newman EM, Dhe-Paganon S. Amino-terminal dimerization, NRDP1-rhodanese interaction, and inhibited catalytic domain conformation of the ubiquitin-specific protease 8 (USP8) The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:38061–38070. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606704200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y, Zhou X, Huang P. Fanconi anemia and ubiquitination. Journal of genetics and genomics = Yi chuan xue bao. 2007;34:573–580. doi: 10.1016/S1673-8527(07)60065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nijman SM, Huang TT, Dirac AM, Brummelkamp TR, Kerkhoven RM, D’Andrea AD, Bernards R. The deubiquitinating enzyme USP1 regulates the Fanconi anemia pathway. Molecular cell. 2005;17:331–339. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fujiwara T, Saito A, Suzuki M, Shinomiya H, Suzuki T, Takahashi E, Tanigami A, Ichiyama A, Chung CH, Nakamura Y, Tanaka K. Identification and chromosomal assignment of USP1, a novel gene encoding a human ubiquitin-specific protease. Genomics. 1998;54:155–158. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohn MA, Kowal P, Yang K, Haas W, Huang TT, Gygi SP, D’Andrea AD. A UAF1-containing multisubunit protein complex regulates the Fanconi anemia pathway. Molecular cell. 2007;28:786–797. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Priolo C, Tang D, Brahamandan M, Benassi B, Sicinska E, Ogino S, Farsetti A, Porrello A, Finn S, Zimmermann J, Febbo P, Loda M. The isopeptidase USP2a protects human prostate cancer from apoptosis. Cancer research. 2006;66:8625–8632. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stevenson LF, Sparks A, Allende-Vega N, Xirodimas DP, Lane DP, Saville MK. The deubiquitinating enzyme USP2a regulates the p53 pathway by targeting Mdm2. The EMBO journal. 2007;26:976–986. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin H, Keriel A, Morales CR, Bedard N, Zhao Q, Hingamp P, Lefrancois S, Combaret L, Wing SS. Divergent N-terminal sequences target an inducible testis deubiquitinating enzyme to distinct subcellular structures. Molecular and cellular biology. 2000;20:6568–6578. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.17.6568-6578.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rotter V, Schwartz D, Almon E, Goldfinger N, Kapon A, Meshorer A, Donehower LA, Levine AJ. Mice with reduced levels of p53 protein exhibit the testicular giant-cell degenerative syndrome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1993;90:9075–9079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.9075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwartz D, Goldfinger N, Kam Z, Rotter V. p53 controls low DNA damage-dependent premeiotic checkpoint and facilitates DNA repair during spermatogenesis. Cell Growth Differ. 1999;10:665–675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coutts AS, La Thangue NB. Mdm2 widens its repertoire. Cell cycle (Georgetown, Tex) 2007;6:827–829. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.7.4086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheon KW, Baek KH. HAUSP as a therapeutic target for hematopoietic tumors (review) International journal of oncology. 2006;28:1209–1215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li M, Chen D, Shiloh A, Luo J, Nikolaev AY, Qin J, Gu W. Deubiquitination of p53 by HAUSP is an important pathway for p53 stabilization. Nature. 2002;416:648–653. doi: 10.1038/nature737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gousseva N, Baker RT. Gene structure, alternate splicing, tissue distribution, cellular localization, and developmental expression pattern of mouse deubiquitinating enzyme isoforms Usp2-45 and Usp2-69. Gene expression. 2003;11:163–179. doi: 10.3727/000000003108749053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Graner E, Tang D, Rossi S, Baron A, Migita T, Weinstein LJ, Lechpammer M, Huesken D, Zimmermann J, Signoretti S, Loda M. The isopeptidase USP2a regulates the stability of fatty acid synthase in prostate cancer. Cancer cell. 2004;5:253–261. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baron A, Migita T, Tang D, Loda M. Fatty acid synthase: a metabolic oncogene in prostate cancer? Journal of cellular biochemistry. 2004;91:47–53. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Renatus M, Parrado SG, D’Arcy A, Eidhoff U, Gerhartz B, Hassiepen U, Pierrat B, Riedl R, Vinzenz D, Worpenberg S, Kroemer M. Structural basis of ubiquitin recognition by the deubiquitinating protease USP2. Structure. 2006;14:1293–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gray DA, Inazawa J, Gupta K, Wong A, Ueda R, Takahashi T. Elevated expression of Unph, a proto-oncogene at 3p21.3, in human lung tumors. Oncogene. 1995;10:2179–2183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gupta K, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Jenkins NA, Gray DA. Unp, a mouse gene related to the tre oncogene. Oncogene. 1993;8:2307–2310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wada K, Kamitani T. UnpEL/Usp4 is ubiquitinated by Ro52 and deubiquitinated by itself. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2006;342:253–258. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.01.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wada K, Tanji K, Kamitani T. Oncogenic protein UnpEL/Usp4 deubiquitinates Ro52 by its isopeptidase activity. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2006;339:731–736. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.11.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Toews ML. Adenosine receptors find a new partner and move out. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:1075–1078. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.022699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Milojevic T, Reiterer V, Stefan E, Korkhov VM, Dorostkar MM, Ducza E, Ogris E, Boehm S, Freissmuth M, Nanoff C. The ubiquitin-specific protease Usp4 regulates the cell surface level of the A2A receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:1083–1094. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.015818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paulding CA, Ruvolo M, Haber DA. The Tre2 (USP6) oncogene is a hominoid-specific gene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:2507–2511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437015100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakamura T, Hillova J, Mariage-Samson R, Onno M, Huebner K, Cannizzaro LA, Boghosian-Sell L, Croce CM, Hill M. A novel transcriptional unit of the tre oncogene widely expressed in human cancer cells. Oncogene. 1992;7:733–741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dechamps C, Bach S, Portetelle D, Vandenbol M. The Tre2 oncoprotein, implicated in Ewing’s sarcoma, interacts with two components of the cytoskeleton. Biotechnology letters. 2006;28:223–231. doi: 10.1007/s10529-005-5523-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Macera MJ, Szabo P, Wadgaonkar R, Siddiqui MA, Verma RS. Localization of the gene coding for ventricular myosin regulatory light chain (MYL2) to human chromosome 12q23-q24.3. Genomics. 1992;13:829–831. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(92)90161-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Masuda-Robens JM, Kutney SN, Qi H, Chou MM. The TRE17 oncogene encodes a component of a novel effector pathway for Rho GTPases Cdc42 and Rac1 and stimulates actin remodeling. Molecular and cellular biology. 2003;23:2151–2161. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.6.2151-2161.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Holowaty MN, Sheng Y, Nguyen T, Arrowsmith C, Frappier L. Protein interaction domains of the ubiquitin-specific protease, USP7/HAUSP. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:47753–47761. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307200200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cummins JM, Vogelstein B. HAUSP is required for p53 destabilization. Cell cycle (Georgetown, Tex. 2004;3:689–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li M, Brooks CL, Kon N, Gu W. A dynamic role of HAUSP in the p53-Mdm2 pathway. Molecular cell. 2004;13:879–886. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00157-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meulmeester E, Pereg Y, Shiloh Y, Jochemsen AG. ATM-mediated phosphorylations inhibit Mdmx/Mdm2 stabilization by HAUSP in favor of p53 activation. Cell cycle (Georgetown, Tex. 2005;4:1166–1170. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.9.1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meulmeester E, Maurice MM, Boutell C, Teunisse AF, Ovaa H, Abraham TE, Dirks RW, Jochemsen AG. Loss of HAUSP-mediated deubiquitination contributes to DNA damage-induced destabilization of Hdmx and Hdm2. Molecular cell. 2005;18:565–576. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brooks CL, Gu W. Dynamics in the p53-Mdm2 ubiquitination pathway. Cell cycle (Georgetown, Tex. 2004;3:895–899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Linares LK, Hengstermann A, Ciechanover A, Muller S, Scheffner M. HdmX stimulates Hdm2-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of p53. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:12009–12014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2030930100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Holowaty MN, Zeghouf M, Wu H, Tellam J, Athanasopoulos V, Greenblatt J, Frappier L. Protein profiling with Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen-1 reveals an interaction with the herpesvirus-associated ubiquitin-specific protease HAUSP/USP7. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:29987–29994. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303977200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boutell C, Sadis S, Everett RD. Herpes simplex virus type 1 immediate-early protein ICP0 and is isolated RING finger domain act as ubiquitin E3 ligases in vitro. Journal of virology. 2002;76:841–850. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.2.841-850.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kato M, Miyazawa K, Kitamura N. A deubiquitinating enzyme UBPY interacts with the Src homology 3 domain of Hrs-binding protein via a novel binding motif PX(V/I)(D/N)RXXKP. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2000;275:37481–37487. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007251200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Naviglio S, Mattecucci C, Matoskova B, Nagase T, Nomura N, Di Fiore PP, Draetta GF. UBPY: a growth-regulated human ubiquitin isopeptidase. The EMBO journal. 1998;17:3241–3250. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.12.3241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Niendorf S, Oksche A, Kisser A, Lohler J, Prinz M, Schorle H, Feller S, Lewitzky M, Horak I, Knobeloch KP. Essential role of ubiquitin-specific protease 8 for receptor tyrosine kinase stability and endocytic trafficking in vivo. Molecular and cellular biology. 2007;27:5029–5039. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01566-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mayer BJ. SH3 domains: complexity in moderation. Journal of cell science. 2001;114:1253–1263. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.7.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kaneko T, Kumasaka T, Ganbe T, Sato T, Miyazawa K, Kitamura N, Tanaka N. Structural insight into modest binding of a non-PXXP ligand to the signal transducing adaptor molecule-2 Src homology 3 domain. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:48162–48168. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306677200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Takata H, Kato M, Denda K, Kitamura N. A hrs binding protein having a Src homology 3 domain is involved in intracellular degradation of growth factors and their receptors. Genes Cells. 2000;5:57–69. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2000.00303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Row PE, Liu H, Hayes S, Welchman R, Charalabous P, Hofmann K, Clague MJ, Sanderson CM, Urbe S. The MIT domain of UBPY constitutes a CHMP binding and endosomal localization signal required for efficient epidermal growth factor receptor degradation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:30929–30937. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704009200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tsang HT, Connell JW, Brown SE, Thompson A, Reid E, Sanderson CM. A systematic analysis of human CHMP protein interactions: additional MIT domain-containing proteins bind to multiple components of the human ESCRT III complex. Genomics. 2006;88:333–346. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu X, Yen L, Irwin L, Sweeney C, Carraway KL., 3rd Stabilization of the E3 ubiquitin ligase Nrdp1 by the deubiquitinating enzyme USP8. Molecular and cellular biology. 2004;24:7748–7757. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.17.7748-7757.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Qiu XB, Markant SL, Yuan J, Goldberg AL. Nrdp1-mediated degradation of the gigantic IAP, BRUCE, is a novel pathway for triggering apoptosis. The EMBO journal. 2004;23:800–810. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Diamonti AJ, Guy PM, Ivanof C, Wong K, Sweeney C, Carraway KL., 3rd An RBCC protein implicated in maintenance of steady-state neuregulin receptor levels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:2866–2871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052709799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Qiu XB, Goldberg AL. Nrdp1/FLRF is a ubiquitin ligase promoting ubiquitination and degradation of the epidermal growth factor receptor family member, ErbB3. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:14843–14848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232580999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ballif BA, Cao Z, Schwartz D, Carraway KL, 3rd, Gygi SP. Identification of 14-3-3epsilon substrates from embryonic murine brain. Journal of proteome research. 2006;5:2372–2379. doi: 10.1021/pr060206k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yaffe MB, Rittinger K, Volinia S, Caron PR, Aitken A, Leffers H, Gamblin SJ, Smerdon SJ, Cantley LC. The structural basis for 14-3-3:phosphopeptide binding specificity. Cell. 1997;91:961–971. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80487-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Benzinger A, Muster N, Koch HB, Yates JR, 3rd, Hermeking H. Targeted proteomic analysis of 14-3-3 sigma, a p53 effector commonly silenced in cancer. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:785–795. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500021-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Meek SE, Lane WS, Piwnica-Worms H. Comprehensive proteomic analysis of interphase and mitotic 14-3-3-binding proteins. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:32046–32054. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403044200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mizuno E, Kitamura N, Komada M. 14-3-3-dependent inhibition of the deubiquitinating activity of UBPY and its cancellation in the M phase. Experimental cell research. 2007;313:3624–3634. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Khut PY, Tucker B, Lardelli M, Wood SA. Evolutionary and Expression Analysis of the Zebrafish Deubiquitylating Enzyme, Usp9. Zebrafish. 2007;4:95–101. doi: 10.1089/zeb.2006.0502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Al-Hakim AK, Goransson O, Deak M, Toth R, Campbell DG, Morrice NA, Prescott AR, Alessi DR. 14-3-3 cooperates with LKB1 to regulate the activity and localization of QSK and SIK. Journal of cell science. 2005;118:5661–5673. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Guo S, Kemphues KJ. par-1, a gene required for establishing polarity in C. elegans embryos, encodes a putative Ser/Thr kinase that is asymmetrically distributed. Cell. 1995;81:611–620. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shulman JM, Benton R, St Johnston D. The Drosophila homolog of C. elegans PAR-1 organizes the oocyte cytoskeleton and directs oskar mRNA localization to the posterior pole. Cell. 2000;101:377–388. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80848-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Choe EA, Liao L, Zhou JY, Cheng D, Duong DM, Jin P, Tsai LH, Peng J. Neuronal morphogenesis is regulated by the interplay between cyclin-dependent kinase 5 and the ubiquitin ligase mind bomb 1. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9503–9512. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1408-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liu N, Dansereau DA, Lasko P. Fat facets interacts with vasa in the Drosophila pole plasm and protects it from degradation. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1905–1909. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sengoku T, Nureki O, Nakamura A, Kobayashi S, Yokoyama S. Structural basis for RNA unwinding by the DEAD-box protein Drosophila Vasa. Cell. 2006;125:287–300. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chen X, Zhang B, Fischer JA. A specific protein substrate for a deubiquitinating enzyme: Liquid facets is the substrate of Fat facets. Genes & development. 2002;16:289–294. doi: 10.1101/gad.961502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cadavid AL, Ginzel A, Fischer JA. The function of the Drosophila fat facets deubiquitinating enzyme in limiting photoreceptor cell number is intimately associated with endocytosis. Development (Cambridge, England) 2000;127:1727–1736. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.8.1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Grunda JM, Nabors LB, Palmer CA, Chhieng DC, Steg A, Mikkelsen T, Diasio RB, Zhang K, Allison D, Grizzle WE, Wang W, Gillespie GY, Johnson MR. Increased expression of thymidylate synthetase (TS), ubiquitin specific protease 10 (USP10) and survivin is associated with poor survival in glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) Journal of neuro-oncology. 2006;80:261–274. doi: 10.1007/s11060-006-9191-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Soncini C, Berdo I, Draetta G. Ras-GAP SH3 domain binding protein (G3BP) is a modulator of USP10, a novel human ubiquitin specific protease. Oncogene. 2001;20:3869–3879. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cohen M, Stutz F, Belgareh N, Haguenauer-Tsapis R, Dargemont C. Ubp3 requires a cofactor, Bre5, to specifically de-ubiquitinate the COPII protein, Sec23. Nature cell biology. 2003;5:661–667. doi: 10.1038/ncb1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]