Abstract

This is a randomized factorial design clinical trial which investigates the efficacy and feasibility of providing prognostic information on wound healing. Prognostic information was provided based on baseline or four-week wound characteristics. Healing rates were then determined at 24 weeks for venous leg ulcers and 20 weeks for diabetic neuropathic foot ulcers. Centers that had access to baseline information for venous leg ulcer prognosis had an OR of healing of 1.42 (95%CI: 1.03, 1.95) while centers that had access to information at four weeks had an OR of healing of 1.43 (95%CI: 1.05, 1.95) compared to controls. Diabetic neuropathic foot ulcer patients treated in centers that had been randomized to receive only four-week prognostic information were more likely to heal than individuals seen in centers randomized to receive no intervention (OR 1.50, 95%CI: 1.05, 2.14). Our study found that it is feasible and efficacious to provide prognostic information on venous leg and diabetic neuropathic foot ulcers in a wound care setting using an existing administrative database. This intervention was easy to administer and likely had low associated costs. This method of dispersing prognostic information to healthcare providers should be expanded to include recently published treatment algorithms.

Keywords: venous leg ulcer, diabetic foot ulcer, randomized trial, prognostic information

INTRODUCTION

Chronic wounds of the lower extremities affect a substantial proportion of the population. The most common types of wounds include those associated with venous disease, arterial insufficiency, or diabetes with insensate neuropathy and/or arterial insufficiency1, 2. The prevalence of lower extremity wounds ranges between 0.18% and 1.3% in the adult population2–5. Venous leg ulcers (VLU) account for 40–70% of lower extremity wounds1 and the mainstay of treatment is lower limb compression. Unfortunately, this standard of care has success rates between 30% and 60% after 24 weeks of treatment in clinical trials and the best success rates after a year of therapy range between 70% and 85%6–16. Approximately 15% of diabetic patients in the United States (US) will develop a foot ulcer17, 18 and about 20% of these patients will primarily have arterial insufficiency, about 50% will primarily have diabetic neuropathy, and about 30% will have both conditions (neuroischemia)19. Some recent reports in Europe have indicated a higher prevalence of neuroischemia in those with diabetes20. The standard treatment of diabetic neuropathic foot ulcers (DNFU) (insensate ulcers with adequate arterial perfusion) is wound debridement, moist wound dressing, and off-loading of pressure from the affected lower extremity. Cure rates of 20% to 47% are seen in clinical trials but cure rates as high as 80% have been noted in wound care practices after 20 weeks of care especially if non-removable forms of off-loading are used21. The likelihood of successful treatment for both VLU and DNFU is associated with several baseline factors21–26.

Due to the long treatment time required for these standard therapies and their relatively low success rates, physicians and healthcare providers would benefit from insight into which patients are more likely to respond to standard care therapy. Wasted time and resources could be avoided if patients unlikely to respond could be identified and counseled regarding options for other treatment modalities. Several previous studies have elucidated specific risk factors for delayed or failed healing of both VLU and DNFU21–23, 25–27. Such risk factor profiles have been developed based on wound characteristics obtained at the first visit and after the initiation of care. Wound duration and wound size were both found to be significantly associated with failure of a VLU to heal by the 24th week,27 while wound duration, wound size, and anatomic depth (or grade) of wound were all associated with failure of a DNFU to heal by the 20th week of care21–23. It has also been shown that by the fourth week of care it is often possible to differentiate between those lower extremity ulcers that will heal and those that will not. In addition to the ability to predict the likelihood of healing, information on how much a patient improves by the fourth week of care has also been described as a potential surrogate to be used in clinical trials. These four-week wound algorithms are similar for VLU and DNFU and have been described as percentage change in area, log healing rate, and log area ratio24, 26.

Prognostic algorithms may serve a beneficial role for healthcare providers and patients in identifying which lower extremity wounds are unlikely to heal by the 20th week of standard care. The prognostic algorithms have been validated in cohort studies and have even been used to risk stratify wound healing outcomes. For example, data from multicenter wound care clinics showed that about 51% of patients with DNFU were likely to heal in 1999 but only 34% were likely to heal in 1990. While these results seem to show an improvement over time, those treated in 1999 were more likely to heal based on prognostic factors (i.e., wounds ≤ 2 cm2, wounds ≤ 2 months old, and wound of grade ≤ 2)28. Although developed for their potential clinical benefit, the prognostic algorithms have not been evaluated prospectively or in a randomized clinical trial.

Curative Health Services (CHS) was directly involved in the care of individuals with chronic wounds between 1988 and 200529, 30. Their involvement centered on marketing, healthcare provider education, treatment algorithms, and dispensing of an autologous product that they believe improves the probability that a chronic wound will heal. CHS was associated with more than 130 wound centers in the US and maintained an administrative database containing information on every patient seen in a wound care center since 1988 that has been previously validated to study DFNU31 and similarly used to study VLU26, 27. While the purpose of the database was mainly administrative it also contained information on diagnosis, wound size, wound duration, and anatomic depth. The CHS system has recently merged with another national wound care provider.

Our current study was planned prior to administrative changes at CHS. Our hypothesis was that prognostic algorithms could be clinically useful to wound care providers. This hypothesis is consistent with recent treatment guidance documents32, 33. To that end, CHS began to provide prognostic information to their healthcare providers. Information was provided for patients with DNFU and VLU. Information was based on either baseline prognostic factors or on wound changes at four weeks. In order to explore whether providing this information was beneficial, it was first provided in a limited setting. The initial design was that of a cluster randomized trial. The goals of the trial were to determine if it was feasible to provide this information on the scale of a wound care system and to initially determine if this information was useful. It is important to note that the information was provided without any guidance as to how to change care for those that were identified as unlikely to heal.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Population

We utilized data from the CHS wound care system. This system included as part of their day-to-day function an administrative and limited patient record database. In total, data on more than 120,000 chronic wounds can be accessed in this database. We have previously used this database to study chronic wounds21, 22, 24, 26–28, 31, 34, 35.

Seventy-four centers agreed to participate in this study to evaluate the addition of a prognostic output function to the CHS database. Traditionally, the database was used for patient billing, to determine wound center volume and acuity, and was often used for quality assurance with respect to wound center and provider performance. Our study was designed in collaboration with CHS in order to determine the feasibility of altering the CHS database so that information about a patient’s wound prognosis could be provided to the healthcare professional. In the setting of this evaluation, information already collected in the database about the patient’s outcome and knowledge of which center received which type of prognostic information served as the basis for our analysis. The “prognostic information” was based on calculations programmed into the database on routinely collected data. Calculations were based on previously published algorithms that were initially derived using the CHS database (see below). The prognostic information was calculated by the database for each patient. In a fashion similar to print-outs received from laboratory tests, a print-out of this information was then provided to the healthcare provider and added to the patient’s chart. With respect to our analysis, we sought to determine if providing this information was useful (i.e., whether providing prognostic information based on database programmed algorithms resulted in a change in the proportion of patients who healed). However, it is important to note that while the wound care providers were given information about the prognosis of their patients, they were not given information on how to treat or change their patient’s treatment plan based on the prognostic information. The quality assessment study was conducted for approximately 8 months in 2004–2005.

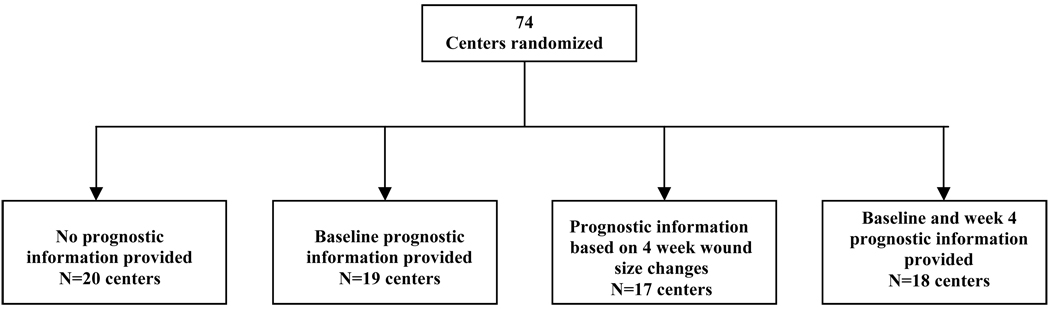

Two specific interventions were tested simultaneously, one for VLU and another for DNFU. Prognostic information was provided based on baseline information and/or four-week information (Figure 1). The algorithms used for these estimations are unique for each ulcer type21, 24, 26, 27. For our study, all individuals were followed prospectively through anonymized data collected in the database. These algorithms are similar to many published in the literature and to those recommended in recent guidance documents16, 25, 26, 31–34, 36.

Figure 1.

Study design schematic

Design

The design of this study is complex in that the type of prognostic information that was provided to each center was determined by cluster randomization (centers were randomized to the type of prognostic intervention) and in order to test all combinations we used a factorial design (i.e., none, baseline only, four week only or baseline followed by four week).

Cluster randomization

This was a cluster randomized trial. Centers were randomly assigned to receive information about the prognosis of a VLU or DNFU treated in CHS centers based on data obtained during the initial history and physical (duration of the wound, size of the wound, and anatomic depth of the wound) or on change in the size of the wound between the first office visit and one on week 4 after commencing therapy. In many ways this study was like a large educational (or behavioral) intervention. Logistically it would have been very difficult to randomize at the patient level without causing individuals to become accidentally exposed by wound care providers that were aware of different prognostic algorithms. Therefore, the unit of randomization and therefore the unit of analysis was the wound care center. In total, 74 centers were randomized based on a simple randomization procedure. While the centers did know of the modification to the database and understood that they might be selected to provide the wound care providers with a new print-out, they did not know that different centers might receive different print-outs. They were also not presented with any educational information about prognostic models.

Factorial Design

Factorial clinical trials test the effect of more than one treatment using a design that allows the investigator to examine interactions among the treatments. The experimental groups are arranged in a way that permits testing if the combination of treatments is better (or worse) than individual treatments. In this study, each wound care center was randomized to receive either no intervention, baseline wound prognostic information, four-week prognostic information, or a combination of both baseline and four-week prognostic information (Figure 1). By using a factorial design, we were able to investigate any possible interaction (synergistic or antagonistic) that could have occurred from receiving the baseline prognostic information followed by the prognostic information provided at four weeks. For example, it might seem reasonable that a wound care provider who received more than one notice that a patient’s wound was unlikely to heal might be more likely to respond to this information.

Wound type and outcome

Subjects were classified as having a VLU in the database if they received a diagnostic code for a venous leg ulcer and no codes for a wound due to another etiology such as diabetes, poor arterial blood flow, or pressure. Subjects were classified as having a DNFU if a diagnostic code was used in the database that was consistent with a diabetic foot or diabetes and foot ulcer, and the subject had no codes consistent with a wound due to another etiology such as poor arterial blood flow to the lower extremity, venous leg ulcer, or a pressure ulcer. The outcome was defined in the database as a healed wound, fully epithelialized and not requiring bandage for at least two wound clinic visits. These are the same methods that have been used and validated in previous CHS records-based studies for ascertaining whether a patient indeed had a DNFU or a VLU and whether the wound had healed21, 22, 24, 26–28, 31, 34, 35.

Prognostic algorithms

Baseline prognostic models were estimated on previous studies conducted using the CHS database for patients starting a new course of therapy 22, 24, 26, 27. For VLU this model was based on logistic regression using wound area and wound duration. The wound care provider was given a probability that the patient’s wound would heal by the 24th week of care and a table placing the wound’s likelihood of healing in perspective with respect to other patients21, 27. Similar information was provided at baseline for those with a DNFU except that wound area, wound duration, and curative wound score, which is based on the anatomic depth of the wound, were used to estimate the probability that a subject would heal by the 20th week of care.

Prognostic information based on changes in wound size after four weeks of care were also based on previous data obtained from CHS. This algorithm was based on log healing rate, log wound area ratio, and percentage change in wound area for VLUs and DFNUs, respectively, and the print-out contained direct percentages as well as information that the change after four weeks had surpassed a landmark such that nearly 70% of the time the patient was likely to heal. As noted above, the print-outs contained only prognostic information on the likelihood of healing and did not include any clinical guidance on how to treat the patient.

Determination of Study Endpoint

All subjects were followed to determine if they had healed by the 24th week of care if they had a VLU and by the 20th week of care if they had a DNFU. A wound was considered healed if it was fully epithelialized and did not require a bandage for at least two visits. Any individual lost to follow-up with an open wound or any individual who received an amputation was considered unhealed. Some subjects had more than one wound. In order to simplify our primary analysis and the information provided to the wound care provider, we only analyzed the subject’s first wound.

Analysis

Data were first analyzed by a simple 4 × 2 contingency table chi square-analysis and then using logistic regression models fitting the prognostic information as a categorical variable and allowing for the unit of analysis to be the wound care center to accommodate the multi-level data. Logistic regression models were also adjusted based on patient age, sex, initial wound size, initial wound duration, and, for the DNFU models, wound grade (initial anatomic depth). Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 9.2 (College Station, TX). This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pennsylvania.

RESULTS

Seventy-four centers agreed to participate in this evaluation and were randomized to one of four groups: no information (control), baseline information only, four-week information only, or baseline followed by four-week information (see Figure 1).

Venous Leg Ulcers

With respect to the VLU evaluation, data from 1,506 individuals were analyzed. Overall, individuals treated in centers that had access to prognostic information were more likely to heal than those who did not have access (Table 1). Even though type of database intervention allocated to a center was randomized, there were some imbalances between the groups with respect to important characteristics like age, sex, initial wound size, and wound duration. Adjusting for these covariates had minimal effect on the estimated odds ratios (ORs) (Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline information about venous leg ulcers randomized to each information group.

| Prognostic information received |

Centers (N) |

Subjects (N) |

Age (sd) |

Gender (Male) |

Baseline wound area (cm2) mean (sd) median (25–75) |

Baseline wound duration (months) mean (sd) median (25–75) |

Percent healed by week 24 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 20 | 372 | 68.8 (16.4) |

47.7% | 14.2 (39.0) 2.4 (0.8,8.0) |

7.2 (29.9) 1 (0.5, 3) |

53.2% |

| Baseline prognostic information |

19 | 516 | 69.8 (15.3) |

41.0% | 11.0 (34.7) 1.9 (0.7,6.2) |

5.6 (13.8) 1 (0.5, 4) |

65.8% |

| Prognostic information based on 4 week wound size changes |

17 | 283 | 66.2 (16.9) |

43.4% | 10.1 (25.8) 2.6 (1.0,7.9) |

9.2 (36.4) 1 (0.5, 4) |

67.4% |

| Baseline and 4 week prognostic information |

18 | 335 | 69.7 (15.9) |

40.9% | 11.5 (35.6) 2.7 (0.8,7.0) |

5.2 (9.5) 1 (0.5, 3) |

66.0% |

Table 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted odds of healing for VLU patients by randomization arm

| Prognostic information received | Unadjusted | Adjusted1 | Adjusted with interaction2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | ref | ref | ref |

| Baseline prognostic information-only | 1.79 (1.22,2.62) | 1.87(1.26,2.79) | |

| Baseline prognostic information | 1.39 (1.03, 1.88) | 1.42 (1.03,1.95) | 1.87 (1.26, 2.79) |

| Prognostic information based on 4 week wound size changes-only | 1.94 (1.34,2.80) | 2.08 (1.41, 3.06) | |

| Prognostic information based on 4 week wound size changes | 1.37 (1.02,1.84) | 1.43 (1.05, 1.95) | 2.08 (1.41,3.06) |

| Baseline and 4 week prognostic information | 1.87 (1.39, 2.52) | 2.00 (1.43,2.81) |

Adjusted for age, gender, baseline area and duration

Adjusted for age, gender, baseline area, duration and interaction based on prognostic information received based on randomization.

Odds ratios are reported based on randomization to one of the four groups, for each combination, and for those who received baseline prognostic factors and those who received prognostic factors based on week four wound data.

For those centers that had access to baseline prognostic information (either baseline only or combined with four-week information) the OR of healing after adjusting for age, sex, baseline area, and duration was 1.42 (95%CI: 1.03, 1.95) compared to centers that received no intervention. For centers that had access to information at four weeks (either four week only or combined with baseline information), the adjusted OR of healing was 1.43 (95%CI: 1.05, 1.95) compared to controls. Interestingly, there was an interaction between the type of prognostic information supplied (i.e., the centers that received two reports) (Table 2). This interaction had an OR of 0.54 (0.32, 0.92, p-value 0.02) indicating that if two notices were received the impact of each of these notices was attenuated. Accounting for this interaction resulted in an adjusted OR of 1.87 (95%CI: 1.26, 2.79) of healing for those centers that received only baseline information and 2.08 (95%CI:1.41,3.06) for those centers that received only information after four weeks of care compared to those centers that did not receive any information (Table 2). No interactions were noted between the efficacy of the prognostic algorithms and baseline wound care characteristics.

Diabetic Neuropathic Foot Ulcers

The same centers also received prognostic information with respect to individuals with DNFU and data from 1,810 individuals were analyzed (Table 3). Although there were some imbalances between the groups with respect to important characteristics like age, sex, wound grade, initial wound size, and wound duration, adjusting for these covariates had minimal effect on the estimated ORs (Table 3 and Table 4). Those individuals treated in centers that had been randomized to receive only four-week prognostic information were more likely to heal than individuals seen in centers randomized to receive no intervention (adjusted OR 1.50, 95%CI: 1.05, 2.14). There was a tendency for those centers that had access to baseline information and a combination of baseline and four-week information to have greater odds of healing than those centers that received no intervention but the difference was not statistically significant (Table 4). Unlike the VLU data, an interaction between receiving a combination of interventions (both baseline and four week) was not noted as measured by an OR of 0.71 (0.42, 1.19, p-value 0.19). No interactions were noted between the efficacy of the prognostic algorithms and baseline wound care characteristics.

Table 3.

Baseline information about diabetic neuropathic foot ulcers randomized to each information group.

| Prognostic information received |

Centers (N) |

Subjects (N) |

Age (sd) | Gender (Male) |

Baseline wound area (cm2) mean (sd) median (25– 75) |

Baseline wound duration (months) mean (sd) median (25– 75) |

Baseline grade > 2 |

Percent healed by week 20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 20 | 521 | 61.6 (14.1) | 53.9% | 6.2 (33.8) 1.1 (0.4,3.8) |

3.2 (11.7) 1 (0.5,2.0) |

19.4% | 48.9% |

| Baseline prognostic information |

19 | 424 | 64.05 (14.3) |

54.2% | 4.9 (13.4) 1.1 (0.3,3.5) |

4.3 (15.2) 1 (0.5,3.0) |

19.8% | 52.1% |

| Prognostic information based on 4 week wound size changes |

17 | 366 | 63.04 (14.2) |

57.6% | 6.8 (22.7) 1.4 (0.4,4.2) |

4.0 (15.6) 1 (0.5,3.0) |

23.4% | 58.2% |

| Baseline and 4 week prognostic information |

18 | 499 | 63.07 (14.4) |

50.5% | 6.4 (28.7) 1.0 (0.3,3.8) |

6.7 (16.1) 1 (0.5,3.0) |

19.2% | 53.1% |

Table 4.

Unadjusted and adjusted odds of healing for DNFU patients by randomization arm

| Prognostic information received | Unadjusted | Adjusted1 | Adjusted with interaction2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | ref | Ref | ref |

| Baseline prognostic information-only | 1.14 (0.81,1.58) | 1.18 (0.80, 1.73) | |

| Baseline prognostic information | 1.00 (0.77,1.29) | 1.00 (0.75,1.31) | 1.18(0.80,1.72) |

| Prognostic information based on 4 week wound size changes-only | 1.45 (1.04,2.02) | 1.50 (1.05, 2.14) | |

| Prognostic information based on 4 week wound size changes | 1.22 (0.94,1.58) | 1.21(0.92,1.59) | 1.50(1.05,2.14) |

| Baseline and 4 week prognostic information | 1.18 (0.81,1.58) | 1.18 (0.85,1.63) |

Adjusted for age, gender, baseline area and duration

Adjusted for age, gender, baseline area, duration and interaction based on prognostic information received based on randomization.

Odds ratios are reported based on randomization to one of the four groups, for each combination, and for those who received baseline prognostic factors and those who received prognostic factors based on week four wound data.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge this is the first and largest randomized evaluation of an administrative and educational intervention in wound care. Without providing any guidance on wound care treatment, we provided information to healthcare providers on the prognosis of their current patients based on outcomes of subjects previously cared for in affiliated wound care programs. We were able to provide prognostic information by using a pre-existing electronic database that was common to all of the wound care centers. Programming the database to provide this information was easily accomplished as was providing the reports to the wound care providers. We were able to show that even in a setting of not providing clinical guidance, providing baseline or four-week prognostic information to centers appeared to have a small but positive effect on healing rates by the 24th week of care for patients with VLU. We found similar results in patients with DNFU. Providing prognostic information after four weeks of treatment appeared to have a positive effect on cure rates by the 20th week of care. A small trend was noted with respect to baseline prognostic information. This study confirms recommendations made in guidance documents concerning the importance of evaluating prognostic information with respect to a patient’s treatment plan and the importance of using information on improvement within four weeks of initiation of care32, 33. It also validates, using randomized clinical trial design, the usefulness of using change in wound size after four weeks of care as a surrogate marker for a healed wound.

By using a factorial design, we were able to investigate whether there was an added benefit to providing centers with baseline followed by four-week prognostic information. Interestingly, for VLU, we found that there was an interaction such that the OR for healing among centers that received two prognostic reports was less than that for centers that only received one report. It is difficult to speculate as to why providing both baseline and four-week information would attenuate the results of either treatment alone. One possibility is that healthcare providers may have disregarded the second notices (i.e., the notice at four weeks) because they had already altered care based on the reporting of prognostic information provided on baseline factors. Or, clinicians may have felt that the reports were not sufficiently useful clinically to engage their interests for the entire study period. This may also be related to the fact that the reports did not include guidance on therapy. This belief is reflected in results of a sensitivity analysis of only those subjects who began treatment at centers within the first two months of the commencement of this study. In this analysis no interaction was seen (data not shown). No interaction was seen in the DNFU population with regard to whether or not centers received both interventions (baseline and four weeks).

The cost and difficulty involved in programming the database to provide prognostic information to healthcare providers were minimal and therefore even small benefits in cure rates would mean that there is value to this application. This very-low-cost behavioral intervention had effects on cure rates of chronic lower extremity wounds that approach those of the only FDA-approved treatments such as the recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor, 0.01% becaplermin gel (treatment rates of 36–50% vs. rates of 32–36% in placebo groups according to the package insert) and the use of skin substitutes like apligraf and dermagraft37. It is very likely that improved healing rates were due to healthcare providers altering treatment plans, which may have resulted in increased utilization of these therapies, other therapies, or treatment plans based on previously published treatment guidelines‥ However, the main goals of this study were to determine the feasibility of altering an electronic database to provide real-time prognostic information and to evaluate the usefulness of this intervention, we did not provide therapeutic advice.

Like all epidemiologic studies there are strengths and weaknesses to this study design. To our knowledge, this is the first randomized behavioral intervention using a database in wound care centers. In order to avoid any contamination between treatment arms, we randomized at the level of the wound care center rather than the individual patient. By using a factorial design, we were able to determine if there was any benefit to combining two prognostic models (baseline and four-week information). However, we cannot be sure if the wound care providers actually read the prognostic information and we certainly do not know if they overtly reacted to it. The results of this study suggest that providers did respond in some manner because patients treated in wound care centers that were randomized to receive prognostic information were more likely to heal. We can only assume that their response was an early modification of a patient’s treatment plan for those who were not likely to heal. The method for identification of patients with ulcers using this database has been previously validated; it is possible that there may be some misclassification of ulcer status and or outcome. Our design incorporated randomized allocation of the prognostic information available to a wound care center. As such, randomization is a powerful tool to prevent treatment selection bias. Participation by a center in this study was voluntary and the reason for non participation is not known. It is therefore possible that fundamental differences between centers which agreed to participate and those which did not could result in a loss of generalizability. However, rates of healed ulcers in centers, before this study started, which were randomized to receive no intervention were similar to cure rates found in previous studies using this database and were similar to centers that did not participate in the study21, 25. However, like randomized clinical trials the generalizability of our study, which was based within a wound care provider network, needs to be carefully evaluated when other practice settings are considered. With respect to wound attributes we did not find an interaction between the effectiveness of the database interventions and a wound healing.

As the US population ages, there will likely be an increase in the prevalence of chronic wounds. Currently, there exists a desire among clinicians, patients, and third-party payers for consistency and a higher standard of care in the treatment of this costly and clinically important disease state. To that end, evidence-based guidelines have been developed by several societies, including those recently published by the Wound Healing Society32, 33. Such published guidelines have suggested that changing therapy based on patient response after four weeks of care may be prudent. Our results show that centers that received the intervention indeed did have higher cure rates. Providing centers with additional information on guidance for those less likely to heal will likely result in further improved rates of healing and greater engagement by the wound care providers interpreting the prognostic information. Furthermore, an electronic medical record system could be an ideal system for dispensing information about prognosis as well as linking this information to treatment guidelines. Because it is computer based, the costs to update this system should be minimal as medical knowledge and drug development advance.

In summary, we have determined that it is feasible and efficacious to provide prognostic information on venous leg and diabetic neuropathic foot ulcers in a wound care setting using an existing, but modified, real-time administrative database. Because of the ease of administering this intervention as well as low associated costs (e.g., no additional personnel were hired, etc.), even modest improvements in cure rates would have a positive cost-benefit ratio. Using prognostic information from baseline visits and after four weeks of care has been recommend in guidance documents and our study validates this recommendation. Future studies linking real-time prognostic information to treatment recommendations based on recently published guidance documents are needed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Financial Support: This study was supported in part by a National Research Service Award from the National Institute of Health (SKK) and NIH K24-AR002212 (DJM)

Potential COI: None to declare (SKK, OJH, WBB). DJM has consulting relationships with many companies that have interests in wound care. He does not have a consulting relationship with Curative Health Services and does not know of a company that is interested in marketing the intervention described in this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Phillips TJ. Chronic cutaneous ulcers: etiology and epidemiology. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;102:38S–41S. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12388556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hallbook T. Leg ulcer epidemiology. Acta Chir Scand Suppl. 1988;544:17–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angle N, Bergan JJ. Chronic venous ulcer. Bmj. 1997;314:1019–1023. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7086.1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coon WW, Willis PW, 3rd, Keller JB. Venous thromboembolism and other venous disease in the Tecumseh community health study. Circulation. 1973;48:839–846. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.48.4.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Callam MJ, Harper DR, Dale JJ, Ruckley CV. Chronic ulcer of the leg: clinical history. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1987;294:1389–1391. doi: 10.1136/bmj.294.6584.1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Margolis DJ, Cohen JH. Management of chronic venous leg ulcers: a literature-guided approach. Clin Dermatol. 1994;12:19–26. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(94)90253-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheatle TR, Scurr JH, Smith PD. Drug treatment of chronic venous insufficiency and venous ulceration: a review. J R Soc Med. 1991;84:354–358. doi: 10.1177/014107689108400616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fletcher A, Cullum N, Sheldon TA. A systematic review of compression treatment for venous leg ulcers. Bmj. 1997;315:576–580. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7108.576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skog E, Arnesjö B, Troëng T, Gjöres JE, Bergljung L, Gundersen J, Hallböök T, Hessman Y, Hillström L, Månsson T, Eilard U, Eklöff B, Plate G, Norgren L. A randomized trial comparing cadexomer iodine and standard treatment in the out-patient management of chronic venous ulcers. Br J Dermatol. 1983;109:77–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1983.tb03995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cordts PR, Hanrahan LM, Rodriguez AA, Woodson J, LaMorte WW, Menzoian JO. A prospective, randomized trial of Unna’s boot versus Duoderm CGF hydroactive dressing plus compression in the management of venous leg ulcers. J Vasc Surg. 1992;15:480–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lippmann HI, Fishman LM, Farrar RH, Bernstein RK, Zybert PA. Edema control in the management of disabling chronic venous insufficiency. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1994;75:436–441. doi: 10.1016/0003-9993(94)90168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubin JR, Alexander J, Plecha EJ, Marman C. Unna'boot vs polyurethane foam dressings for the treatment of venous ulceration A randomized prospective study. Arch Surg. 1990;125:489–490. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1990.01410160075016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eriksson G. Comparison of two occlusive bandages in the treatment of venous leg ulcers. Br J Dermatol. 1986;114:227–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1986.tb02801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Falanga V, Margolis D, Alvarez O, Auletta M, Maggiacomo F, Altman M, Jensen J, Sabolinski M, Hardin-Young J. Rapid healing of venous ulcers and lack of clinical rejection with an allogeneic cultured human skin equivalent. Human Skin Equivalent Investigators Group. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:293–300. doi: 10.1001/archderm.134.3.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lyon RT, Veith FJ, Bolton L, Machado F. Clinical benchmark for healing of chronic Venous ulcer. Study Collaborators. Am J Surg. 1998;176:172–175. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(98)00136-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skene AI, Smith JM, Dore CJ, Charlett A, Lewis JD. Venous leg ulcers: a prognostic index to predict time to healing. Bmj. 1992;305:1119–1121. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6862.1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McNeely MJ, Boyko EJ, Ahroni JH, Stensel VL, Reiber GE, Smith DG, Pecoraro RF. The independent contributions of diabetic neuropathy and vasculopathy in foot ulceration.How great are the risks? Diabetes Care. 1995;18:216–219. doi: 10.2337/diacare.18.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reiber GE. The epidemiology of diabetic foot problems. Diabet Med. 1996;13 Suppl 1:S6–S11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reiber GE, Vileikyte L, Boyko EJ, del Aguila M, Smith DG, Lavery LA, Boulton AJ. Causal pathways for incident lower-extremity ulcers in patients with diabetes from two settings. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:157–162. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abbott CA, Garrow AP, Carrington AL, Morris J, Van Ross ER, Boulton AJ. Foot ulcer risk is lower in South-Asian and african-Caribbean compared with European diabetic patients in the U.K.: the North-West diabetes foot care study. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1869–1875. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.8.1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Margolis DJ, Allen-Taylor L, Hoffstad O, Berlin JA. Diabetic neuropathic foot ulcers: predicting which ones will not heal. Am J Med. 2003;115:627–631. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Margolis DJ, Allen-Taylor L, Hoffstad O, Berlin JA. Diabetic neuropathic foot ulcers: the association of wound size, wound duration, and wound grade on healing. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1835–1839. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.10.1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Margolis DJ, Kantor J, Santanna J, Strom BL, Berlin JA. Risk factors for delayed healing of neuropathic diabetic foot ulcers: a pooled analysis. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1531–1535. doi: 10.1001/archderm.136.12.1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Margolis DJ, Gelfand JM, Hoffstad O, Berlin JA. Surrogate end points for the treatment of diabetic neuropathic foot ulcers. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1696–1700. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.6.1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Margolis DJ, Berlin JA, Strom BL. Risk factors associated with the failure of a venous leg ulcer to heal. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:920–926. doi: 10.1001/archderm.135.8.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gelfand JM, Hoffstad O, Margolis DJ. Surrogate endpoints for the treatment of venous. leg ulcers. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;119:1420–1425. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.19629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Margolis DJ, Allen-Taylor L, Hoffstad O, Berlin JA. The accuracy of venous leg ulcer prognostic models in a wound care system. Wound Repair Regen. 2004;12:163–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1067-1927.2004.012207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Margolis DJ, Allen-Taylor L, Hoffstad O, Berlin JA. Healing diabetic neuropathic foot ulcers: are we getting better? Diabet Med. 2005;22:172–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glover JL, Weingarten MS, Buchbinder DS, Poucher RL, Deitrick GA, 3rd, Fylling CP. A 4-year outcome-based retrospective study of wound healing and limb salvage in patients with chronic wounds. Adv Wound Care. 1997;10:33–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doucette MM, Fylling C, Knighton DR. Amputation prevention in a high-risk population through comprehensive wound-healing protocol. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1989;70:780–785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kantor J, Margolis DJ. The accuracy of using a wound care specialty clinic database to study diabetic neuropathic foot ulcers. Wound Repair Regen. 2000;8:169–173. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.2000.00169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robson MC, Cooper DM, Aslam R, Gould LJ, Harding KG, Margolis DJ, Ochs DE, Serena TE, Snyder RJ, Steed DL, Thomas DR, Wiersma-Bryant L. Guidelines for the treatment of venous ulcers. Wound Repair Regen. 2006;14:649–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2006.00174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steed DL, Attinger C, Colaizzi T, Crossland M, Franz M, Harkless L, Johnson A, Moosa H, Robson M, Serena T, Sheehan P, Veves A, Wiersma-Bryant L. Guidelines for the treatment of diabetic ulcers. Wound Repair Regen. 2006;14:680–692. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2006.00176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Margolis DJ, Allen-Taylor L, Hoffstad O, Berlin JA. Diabetic neuropathic foot ulcers and amputation. Wound Repair Regen. 2005;13:230–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1067-1927.2005.130303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malay DS, Margolis DJ, Hoffstad OJ, Bellamy S. The incidence and risks of failure to heal after lower extremity amputation for the treatment of diabetic neuropathic foot ulcer. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2006;45:366–374. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cardinal M, Eisenbud DE, Phillips T, Harding K. Early healing rates and wound area measurements are reliable predictors of later complete wound closure. Wound Repair Regen. 2008;16:19–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pharmaceutical OM. [Accessed March 2008];Regranex Gel (0.01%) package insert. http://www.jnjgateway.com/public/USENG/REGRANEX_Full_Labeling_PI.pdf.