Nanomedicine utilizes nanoscale materials and principles to effect medical intervention at the molecular scale with the goal of curing diseases or repairing tissues. Drug delivery is arguably one of the most important and promising areas in nanomedicine.1 Among the many recently developed drug carriers, inorganic nanomaterials,2,3 in particular amorphous mesoporous silica nanoparticles, are very attractive because of their biocompatibility combined with high surface area and pore volume as well as uniform, tunable pore diameters and surface chemistries.4 Through simple electrostatic interactions, drugs can be loaded at very high concentrations. Recently, such porous silica particles have been utilized to deliver a wide range of drugs and therapeutic agents, including chemotherapy drugs, proteins, and DNA.5–7

Achieving high drug loading, however, is only one facet of the drug delivery problem. It is equally important that loaded drugs are retained and protected before reaching target tissues or cells to maximize drug efficacy and minimize toxicity. For drugs loaded by electrostatic interactions or physical adsorption in freely accessible pores, metabolites/ ions in the body fluid can displace the drugs (Figure 1A, pathway 1), resulting in premature drug release. To avoid this, molecular-gating strategies based on coumarin,8 azobenzenes,9,10 rotaxanes,11 polymers,12, 13 and nanoparticles14,15 have been designed, wherein drugs are released only upon gate opening or removal.

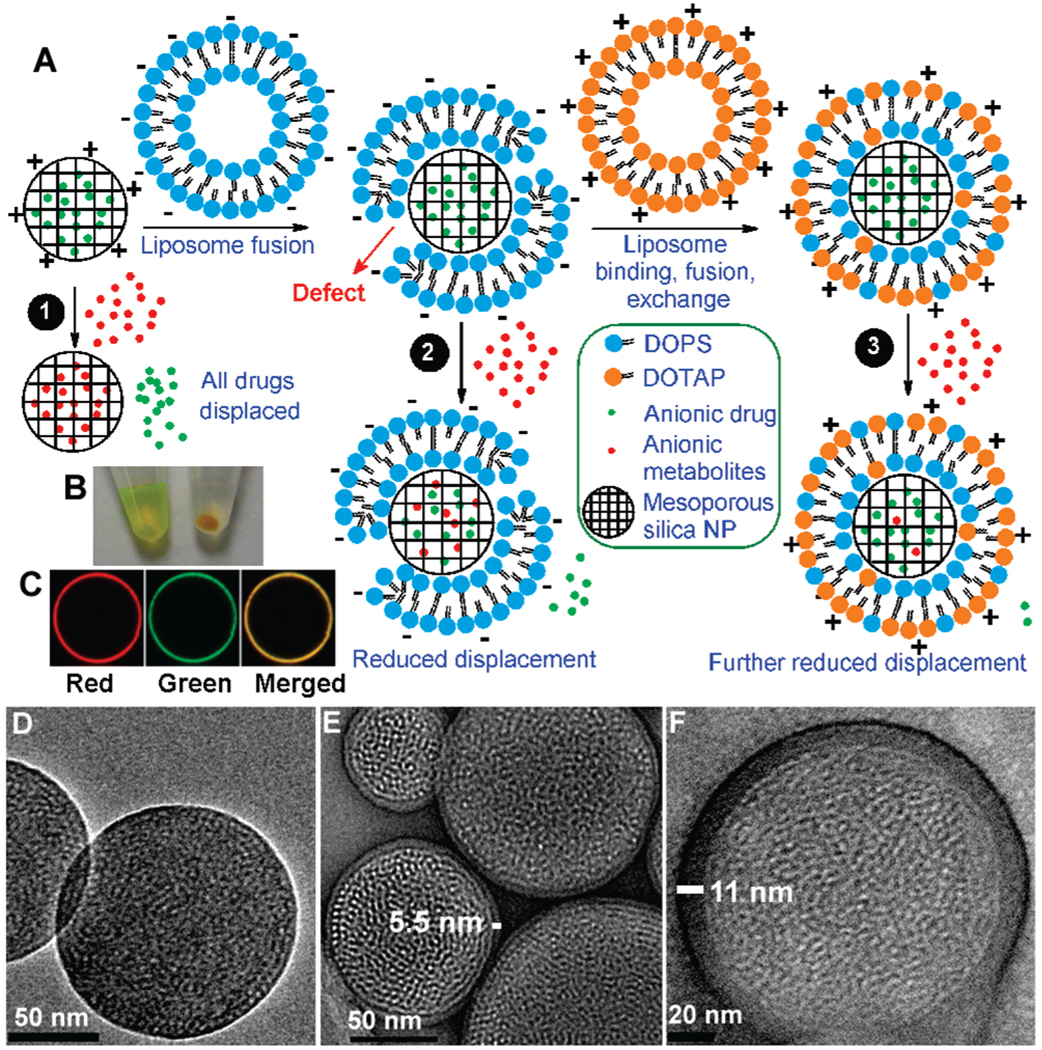

Figure 1.

(A) A negatively charged drug (green dots) is adsorbed into the pores of a cationic mesoporous silica nanoparticle. Other anions that are adsorbed more strongly (red dots) can displace the loaded drugs (pathway 1). Fusion with a negatively charged liposome reduces the displacement (pathway 2), and further lipid exchange/fusion with cationic liposomes reduces it even more (pathway 3). (B) Photograph of samples after mixing (left) anionic and (right) cationic mesoporous silica particles with calcein followed by centrifugation. (C) Confocal fluorescence microscopy images of a large (15 µm) anionic mesoporous silica particle fused first with Texas Red-DHPE-labeled DOTAP (red) and then mixed with NBD-PC-labeled DOPS liposome (green). The merged image shows colocalization of the red- and green-labeled lipids. (D–F) Representative TEM images of bare anionic mesoporous silica cores (D) and protocells with single (E) or dual (F) supported bilayers formed after successive DOTAP and DOPS fusion/ exchange steps (lipid-fixed and negative-stained).

When confronted with the similar problem of controlling materials exchange, cells utilize lipid membranes to retain and protect intracellular components. Most charged hydrophilic molecules and ions cannot diffuse through the hydrophobic lipid bilayer and are effectively confined inside cells. Inspired by nature’s designs, we have fused liposomes on mesoporous silica nanoparticles and investigated these “protocell” constructs for applications in drug delivery. To date, supported lipid bilayers have been studied extensively as models of the cell membrane,16 but their applications in nanomedicine have yet to be explored. Here we report that liposome fusion on silica cores followed by successive steps of electrostatically mediated lipid exchange between silica-supported bilayers and oppositely charged free liposomes reduces bilayer defects and controls surface charge, allowing cargo retention, delivery, and release inside cells.

Calcein, a negatively charged and membrane-impermeable fluorophore, was used as a model drug. Because of its negative charge, calcein is excluded from negatively charged silica mesopores. As shown in Figure 1B (left side), after calcein and mesoporous silica nanoparticles were mixed and centrifuged, the dye remained in the supernatant, and the particles were colorless. We previously communicated a synergistic loading system in which calcein is loaded into negatively charged silica by fusion of a cationic liposome, 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammoniumpropane (DOTAP).17 In the present work, calcein loading was achieved by incorporation of a cationic amine-modified silane, 3-[2-(2-aminoethylamino)ethylamino]propyltrime-thoxysilane (AEPTMS), (see the Supporting Information) into the silica framework. Cationic mesoporous silica cores with ~2 nm diameter pores were prepared by aerosol-assisted self-assembly18 using tetra-ethylorthosilicate (TEOS) + 10 mol % AEPTMS as silica precursors and CTAB as the structure-directing agent. When the cationic silica particles were dispersed in water at 25 mg/mL in the presence of 1 mM calcein, >99.9% of the calcein (determined by fluorimetry) was adsorbed into the pores (Figure 1B, right side), resulting in a 2.5 wt % loading relative to silica (with saturated calcein, loading can reach 24.2%).

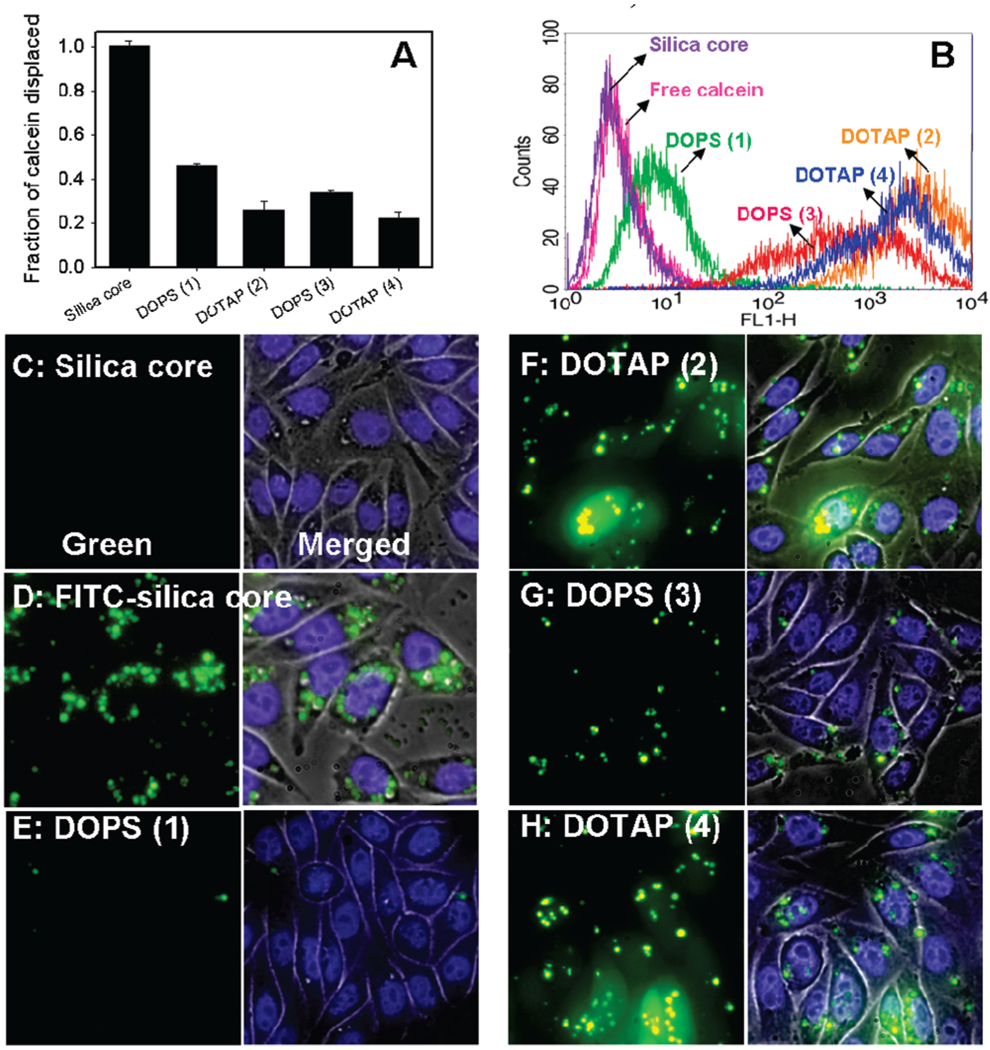

We further tested such calcein-loaded cationic silica particles for delivery of calcein into Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells. Surprisingly, no calcein uptake was observed, as evidenced by the lack of any green fluorescence associated with the cells (Figure 2C). This was also confirmed by flow cytometry studies (Figure 2B), where the fluorescence histogram of cells incubated with the calcein-loaded particles was similar to that of cells incubated with free calcein. The failure of calcein delivery could not be attributed to inhibited nanoparticle uptake, because nanoparticles were clearly observed when silica with covalently labeled FITC was used (Figure 2D). Instead, this failure was attributed to the displacement of calcein by molecules/ions in the culture media. To confirm this, the fluorescence of the F-12K medium after particle centrifugation was measured and compared with that of free calcein dispersed in the same medium. As shown in the first bar in Figure 2A, calcein was quantitatively displaced into the medium. Further experiments showed that small polyvalent anions, such as phosphate, sulfate, and carbonate, as well as chloride are effective in promoting calcein displacement (see the Supporting Information).

Figure 2.

(A) Fraction of calcein release into the F-12K medium after mixing and centrifugation of calcein-loaded cationic silica cores and of cores (1) fused or (2–4) fused and successively exchanged with liposomes of opposite charges, as determined by fluorimetry. The x axis indicates the last liposome added, and the number of lipid fusion/exchange steps is shown in the parentheses. (B) Flow cytometry histogram of CHO cells incubated with different particles/ protocells. Higher intensity along the x axis (FL1-H) indicates more calcein delivery. (C, E–H) Fluorescence microscopy studies of CHO cells incubated with calcein-loaded cationic silica core or protocells after successive lipid fusion/ exchange with oppositely charged liposomes. Stronger green emission indicates a higher level of calcein delivery. (D) Uptake of cationic silica with covalently linked FITC. Cell nuclei were stained by Hoechst 33342 (blue).

To address the problem of premature drug release, our approach employs phospholipid bilayers fused on hydrophilic mesoporous silica cores to create a cell-like structure. We postulated that this supported bilayer “protocell” construct should reduce drug displacement in a manner similar to the cell membrane. Compared with other synthetic organic molecules or nanoparticles used for gating silica pores,8–15 liposome fusion provides a simpler method with better biocompatibility. Additionally, the bilayer remains fluid, and it is possible to graft functional moieties such as targeting ligands and PEG chains on the bilayer to effect targeting and enhanced circulation. Positively charged silica nanoparticles readily fuse with anionic 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-[phospho-l-serine] (DOPS) liposomes. Indeed, after the DOPS bilayer coating was applied, the release of loaded calcein was reduced by ~55% (Figure 2A, bar 2). However, the cellular uptake of calcein was only slightly improved, as evident from both fluorescence microscopy (Figure 2E) and flow cytometry studies. This was attributed to the negative charge of the supported DOPS bilayer, which is repelled by the negatively charged cell surface. To further improve both drug sealing and delivery, we mixed purified DOPS protocells with free cationic DOTAP liposomes (Figure 1A, pathway 3), reducing the calcein release by ~75% (Figure 2A, bar 3) and significantly improving the calcein delivery to CHO cells (Figure 2F). Additional liposome mixing steps with oppositely charged liposomes (use of up to four steps was tested) provided no additional calcein retention (Figure 2A), suggesting some defects were still present, possibly attributable to the defect-inducing properties of cationic nanoparticles as reported by Banaszak Holl and co-workers,19 which produced a subset of defective protocells. Further refinement of the lipid composition may lead to complete pore sealing.6 Overall, when the liposome added at the final step was positively charged DOTAP, the calcein uptake and release (green emission) were substantially greater than for those prepared with negatively charged DOPS (Figure 2E–H).

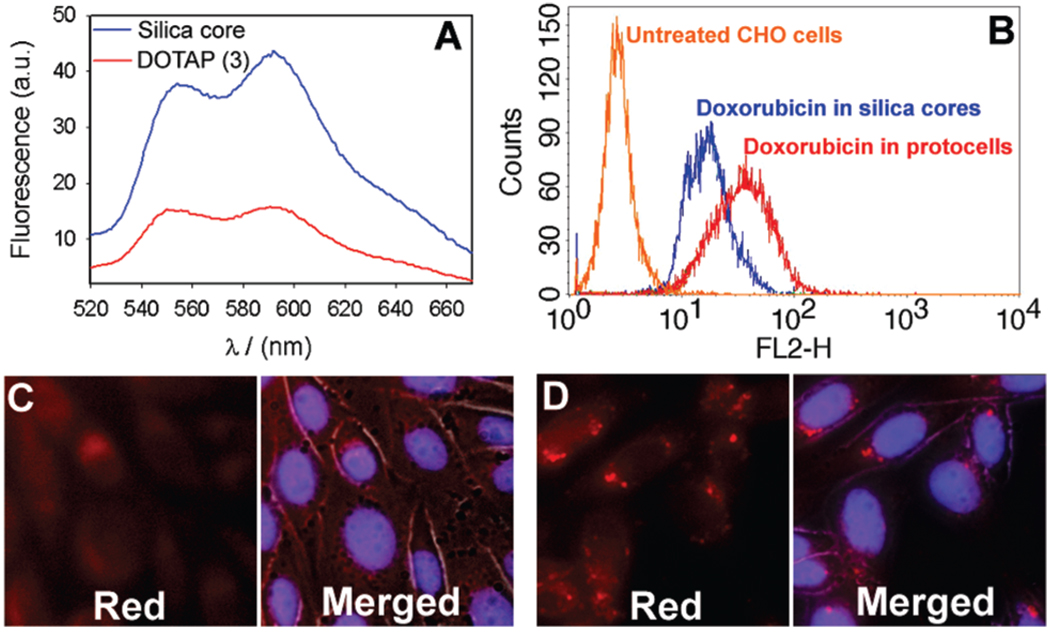

To investigate the generality of this method, we further tested the delivery of doxorubicin, a red-fluorescent chemotherapeutic drug. Positively charged doxorubicin is readily adsorbed by pure anionic mesoporous silica particles (4 wt % loading relative to silica). We compared cellular uptake of doxorubicin-loaded naked silica cores with that of cationic protocells constructed by successive addition of three liposomes (DOTAP/DOPS/DOTAP). Unlike membrane-impermeant calcein, free doxorubicin can be internalized by cells, which contributes to its cytotoxicity. With doxorubicin-loaded naked silica particles, a relatively uniform red fluorescence was observed within the cells (Figure 3C), similar to that resulting from incubation with free doxorubicin. In contrast, the protocells produced a very bright punctuated pattern typical of nanoparticle endocytosis (Figure 3D), suggesting that at least a fraction of the doxorubicin was delivered by the protocells. Flow cytometry studies also showed higher doxorubicin fluorescence when the cells were mixed with protocells (Figure 3B). When the medium supernatant fluorescence data were compared, the emission from the protocells was only about one-third of that from the doxorubicin-loaded naked silica (Figure 3A). This is important because avoiding premature drug release is crucial for reducing drug toxicity. We also tested the toxicity of the drug carriers, and even DOTAP protocells yielded >98% cell viability (see the Supporting Information).

Figure 3.

(A) Doxorubicin fluorescence spectra of the supernatant after mixing of the F-12K medium with doxorubicin-loaded anionic silica cores or cores mixed successively with three liposomes (DOTAP/DOPS/DOTAP) for 20 min, followed by centrifugation. (B) Flow cytometry histogram (doxorubicin fluorescence) of CHO cells incubated with different particles. (C, D) Fluorescence microscopy studies of CHO cells incubated with (C) doxorubicin-loaded silica cores or (D) cores mixed with the three liposomes. Intense red dots in (D) indicate endocytosis instead of nonspecific uptake. Cell nuclei were stained by Hoechst 33342 (blue).

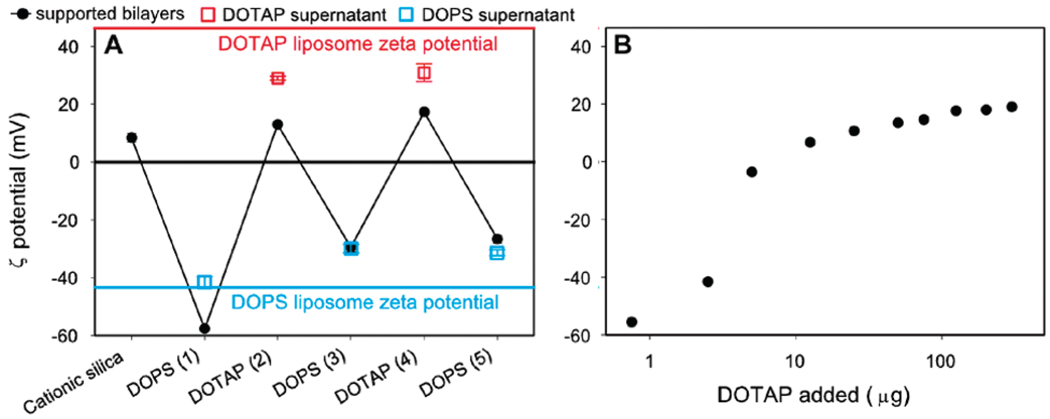

When a supported lipid bilayer is mixed with oppositely charged free liposomes, three outcomes are possible.20 First, the liposomes may fuse with the supported bilayers to form supported multilayers.6 Second, the liposomes may be adsorbed onto supported bilayers as a result of electrostatic interactions. Third, lipid exchange between the supported and free liposomes may occur. Previous work on planar surface-supported bilayers favors the lipid exchange mechanism;20–23 however, Akita et al.6 observed double bilayer fusions with DNA/ polycationic nanoparticle cores. To discern between these various possible outcomes, we monitored the ζ potential of both silica nanoparticle supported bilayers (protocells) and the empty liposomes of the supernatant after mixing and centrifugation. The pure empty DOPS and DOTAP liposomes had ζ potentials of −43 and 46 mV, respectively (blue and red lines in Figure 4A). The surface charge of the protocells can be made positive or negative, depending on the last liposome added. However, after the first fusion step, the absolute values of the ζ potentials for both the protocells and liposomes were less than those of the free liposomes, suggesting that the surface layer is composed of a lipid mixture. These results support the conclusion that after the first fusion step between the anionic DOPS liposome and the naked cationic silica core, the following steps involve lipid exchange; otherwise (e.g., for fusion or adsorption), the ζ potentials of the protocells and liposomes should be identical to those of the pure liposomes. By addition of different concentrations of DOTAP liposomes to supported DOPS bilayers, the surface charge of the resulting supported bilayers can be systematically tuned (Figure 4B). However, even with very high concentrations of DOTAP liposomes, the final particle surface charge was still less than that of pure DOTAP liposomes (46 mV). These results provide a physical picture of the process. When DOPS liposomes are fused with cationic silica nanoparticles, defects are likely to form, and these are difficult to heal because of electrostatic considerations.19,24,25 Subsequent addition of cationic DOTAP liposomes results in electrostatically driven association and lipid exchange up until the point where the diminishing electrostatic interaction and van der Waals attraction are exceeded by the disjoining pressure, after which the associated exchanged liposome is released; this process is qualitatively similar to that seen between oppositely charged liposomes and flat supported bilayers.20

Figure 4.

(A) ζ potentials of cationic mesoporous silica core protocells (black dots), free liposome in the supernatant (red and blue squares) after successive lipid exchange/fusion steps, and pure DOTAP and DOPS liposomes (in 10 mM MOPS, pH 7.0, 60 mM NaCl). (B) ζ potential of protocells made by adding different concentrations of DOTAP liposomes to cationic silica nanoparticle-supported DOPS bilayers.

To confirm the liposome fusion and lipid exchange hypothesis, we performed confocal fluorescence microscopy (CFM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Figure 1C shows CFM images of large (~15 µm) anionic mesoporous silica particles fused first with Texas Red-labeled DOTAP and then mixed with NBD-labeled DOPS. Colocalization of the red and green fluorescence established the presence of both DOTAP and DOPS. Corresponding TEM studies of fixed and stained protocells showed a majority of particles (after both the initial fusion step and subsequent exchange steps) with a ~5.5 nm thick rim (Figure 1E), indicative of a single supported bilayer,26 while a very small fraction of particles (<1%) show a layer of ~11 nm (Figure 1F), indicative of dual bilayers. Therefore, while a majority of the particles underwent lipid exchange, fusion cannot be completely ruled out. Under no conditions did we observe double bilayer fusion6 in a single step.

In summary, we have used lipid fusion and exchange between free and nanoparticle-supported liposomes to reduce defects and control the surface charge of protocells. These parameters are crucial for drug containment and delivery to mammalian cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health through the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research, the DOE Office of Science, and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Methods and materials and Figures S1 – S6. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Langer R. Nature. 1998;392:5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sokolova V, Epple M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:1382–1395. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosi NL, Mirkin CA. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:1547–1562. doi: 10.1021/cr030067f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Vallet-Regi M, Balas F, Arcos D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:7548–7558. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Slowing II, Trewyn BG, Giri S, Lin VSY. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2007;17:1225–1236. [Google Scholar]; (c) Schlossbauer A, Schaffert D, Kecht J, Wagner E, Bein T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:12558–12559. doi: 10.1021/ja803018w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Torney F, Trewyn BG, Lin VSY, Wang K. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2007;2:295–300. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Slowing II, Trewyn BG, Lin VSY. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:8845–8849. doi: 10.1021/ja0719780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lu J, Liong M, Zink JI, Tamanoi F. Small. 2007;3:1341–1346. doi: 10.1002/smll.200700005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akita H, Kudo A, Minoura A, Yamaguti M, Khalil IA, Moriguchi R, Masuda T, Danev R, Nagayama K, Kogure K, Harashima H. Biomaterials. 2009;30:2940. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kogure K, Akita H, Yamada Y, Harashima H. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2008;60:559–571. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mal NK, Fujiwara M, Tanaka Y. Nature. 2003;421:350–353. doi: 10.1038/nature01362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu NG, Dunphy DR, Atanassov P, Bunge SD, Chen Z, Lopez GP, Boyle TJ, Brinker CJ. Nano Lett. 2004;4:551–554. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Angelos S, Choi E, Vogtle F, De Cola L, Zink JI. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2007;111:6589–6592. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguyen TD, Tseng HR, Celestre PC, Flood AH, Liu Y, Stoddart JF, Zink JI. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:10029–10034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504109102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang YJ, Caruso F. Chem. Commum. 2004:1528–1529. doi: 10.1039/b403871a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Radu DR, Lai CY, Wiench JW, Pruski M, Lin VSY. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:1640–1641. doi: 10.1021/ja038222v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lai CY, Trewyn BG, Jeftinija DM, Jeftinija K, Xu S, Jeftinija S, Lin VSY. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:4451–4459. doi: 10.1021/ja028650l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giri S, Trewyn BG, Stellmaker MP, Lin VSY. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005;44:5038–5044. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Sackmann E. Science. 1996;271:43–48. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5245.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ariga K. Chem. Rec. 2004;3:297–307. doi: 10.1002/tcr.10071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Troutier AL, Ladaviere C. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2007;133:1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Davis RW, Flores A, Barrick TA, Cox JM, Brozik SM, Lopez GP, Brozik JA. Langmuir. 2007;23:3864–3872. doi: 10.1021/la062576t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Yang TH, Yee CK, Amweg ML, Singh S, Kendall EL, Dattelbaum AM, Shreve AP, Brinker CJ, Parikh AN. Nano Lett. 2007;7:2446–2451. doi: 10.1021/nl071184j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu J, Stace-Naughton A, Jiang X, Brinker CJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:1354–1355. doi: 10.1021/ja808018y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu YF, Fan HY, Stump A, Ward TL, Rieker T, Brinker CJ. Nature. 1999;398:223–226. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leroueil PR, Berry SA, Duthie K, Han G, Rotello VM, McNerny DQ, Baker JR, Orr BG, Banaszak Holl MM. Nano Lett. 2008;8:420–424. doi: 10.1021/nl0722929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wikstrom A, Svedhem S, Sivignon M, Kasemo B. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:14069–14074. doi: 10.1021/jp803938v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reinl HM, Bayerl TM. Biochemistry. 1994;33:14091–14099. doi: 10.1021/bi00251a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Solon J, Streicher P, Richter R, Brochard-Wyart F, Bassereau P. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:12382–12387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601400103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sapuri AR, Baksh MM, Groves JT. Langmuir. 2003;19:1606–1610. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benz M, Gutsmann T, Chen NH, Tadmor R, Israelachvili J. Biophys. J. 2004;86:870–879. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74162-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khan A, Ducker WA, Mao M. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:23365–23372. doi: 10.1021/jp063498l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mornet S, Lambert O, Duguet E, Brisson A. Nano Lett. 2005;5:281–285. doi: 10.1021/nl048153y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.