Abstract

UVB irradiation of DNA produces photodimers in adjacent DNA bases and on rare occasions in non-adjacent bases. UVB irradiation (312 nm) of d(GTATCATGAGGTGC) gave rise to an unknown DNA photoproduct in approximately 40% yield at acidic pH of about 5. This product has a much shorter retention time in reverse phase HPLC compared to known dipyrimidine photoproducts of this sequence. A large upfield shift of two thymine H6 NMR signals and photoreversion to the parent ODN upon irradiation with 254 nm light indicates that the photoproduct is a cyclobutane thymine dimer. Exonuclease-coupled MS assay establishes that the photodimer forms between T2 and T7, which was confirmed by tandem mass spectrometric MS/MS identification of the endonuclease P1 digestion product d(T2[A3])=pd(T7[G8]). Acidic hydrolysis of the photoproduct gave a product with the same retention time on reverse phase HPLC and the same MS/MS fragmentation pattern as authentic Thy[c,a]Thy. 2D NOE NMR data are consistent with a cis-anti cyclobutane dimer between the 3′-sides of T2 and T7 in anti glycosyl conformations that had to have arisen from an inter-stand type reaction. In addition to pH-dependent, the photoproduct yield is highly sequence specific and concentration dependent, indicating that it results from a higher order folded structure. The efficient formation of this inter-strand-type photoproduct suggests the existence of a new type of folding motif and the possibility that this type of photoproduct might also form in other folded structures, such as G-quadruplexes and i-motif structures which can be now studied by the methods described.

Keywords: cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer, Dewar photoproduct, DNA, enzyme-coupled, inter-strand, mass spectrometry, non-adjacent, NMR, Nuclease P1, phosphodiesterase, photoproduct, UV

Introduction

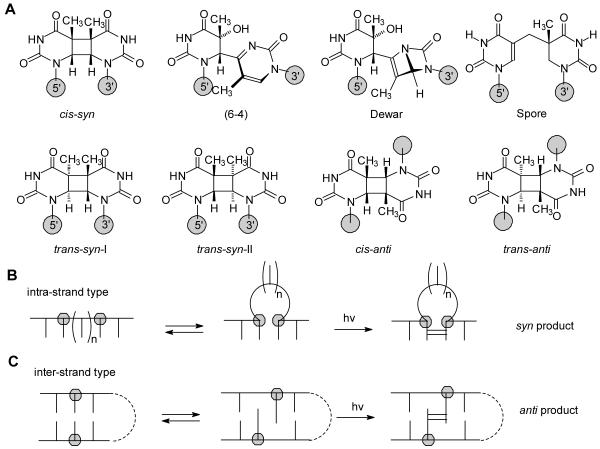

Exposure of cells to ultraviolet light results in the formation of DNA photoproducts, many of which have been linked to skin cancer.1-4 The majority of these photoproducts arise from a photoreaction between two pyrimidines, the structure and stereochemistry of which depend on the conformation of the two bases at the time of irradiation. Irradiation of double stranded B form DNA under physiological conditions mainly produces cis-syn cyclobutane pyridine dimers (CPDs), pyrimidine (6-4) pyrimidone photoproducts, and their Dewar valence isomers (Figure 1A).5-9 Minor amounts of the trans-syn-I cyclobutane dimer have been detected in irradiated samples of native double stranded DNA, and presumably form from single-stranded sections of DNA in which the thymine base has rotated into a syn glycosyl conformation prior to photodimerization. A form DNA, on the other hand appears to suppress these photoproducts, and instead favors formation of the spore photoproduct.10,11

Figure 1.

Photochemistry of DNA. A) Structures of the major type of photoproducts,. B) Intra- and C) inter-strand-type photoreactions, both of which lead to non-adjacent photoproducts, except when n = 0 for B), which results in an adjacent photoproduct.

Non-adjacent photodimers of both intra-strand and inter-strand types are much rarer. Intra-strand-type non-adjacent dimers form when one or more nucleotides between two pyrimidines become extrahelical, due to the formation of single strand DNA or a slipped structure, thereby allowing the two pyrimidines to photodimerize in a co-linear arrangement, as if the intervening sequence was not present (Figure 1B). Because non-adjacent dimer formation effectively shortens the DNA template, this type of photoproduct has been implicated in the formation of UV-induced deletion mutations.12 Non-adjacent thymine dimers having a predominantly cis-syn configuration form in d(GT)n upon germicidal lamp irradiation (λmax 254 nm)12 and near-ultraviolet irradiation (λmax 310 nm)13. A non-adjacent cis-syn cyclobutane dimer between the two T’s of TCT was subsequently prepared in good yield by triplet-sensitized irradiation of a bulged loop duplex DNA structure formed between the 13-mer d(GAGTATCTATGAG) and the 12-mer d(CTCATAATACTC).14

Inter-strand-type DNA photoproducts arise from reactions between bases on opposing strands of duplex DNA in a parallel or antiparallel orientation (Figure 1C) and have not been detected under native, aqueous conditions. An early study showed that d(GT)n·d(CA)n could be photocrosslinked in ethanolic solutions, or in aqueous solutions containing a high concentration of manganese.15 More recently, UVC irradiation of freeze-dried and alcoholic solutions of calf thymus DNA have been reported to give significant amounts of inter-strand photoproducts.11 Enzymatic degradation of DNA irradiated under these conditions revealed the formation of non-adjacent spore photoproduct, as well as non-adjacent cis-syn, cis-anti, and trans-anti cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers. Non-adjacent photoproducts were distinguished from adjacent photoproducts by the absence of an inter-nucleotide phosphate linkage following enzymatic digestion. The formation of the non-adjacent photoproducts was attributed to inter-strand-type reactions between the bases (Figure 1B, bottom row), but some of these products could have arisen from intra-strand-type reactions (Figure 1B, top row). The method used, however, doesn’t allow distinction between inter- and intra-strand non-adjacent photodimers.

In the course of irradiating d(GTATCATGAGGTGC) with UVB light to prepare a site-specific cis-syn TC cyclobutane dimer photoproduct for study, we discovered a new DNA photoproduct that was produced in unusually high yield at acidic pH. Herein, we report physical, enzymatic, MS and NMR evidence that this photoproduct is an inter-strand-type non-adjacent cis-anti cyclobutane thymine dimer product formed between T2 and T7. This novel and unexpected photoproduct can be explained to arise from an inter-strand-type reaction due to an unusual higher order folded DNA structure. This is the first inter-strand-type non-adjacent photoproduct to be characterized in DNA and the first to be produced efficiently in aqueous solution, and points to the existence of a new type of DNA folding motif. The facile formation of this inter-strand photoproduct also suggests that such a photoproduct may form in other folded structures, such as G-quadruplexes in telomeres and promoters, and i-motif structures,16,17 which could now be studied by the methods described herein.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Oligodeoxynucleotides were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (IDT) (Coralville, Iowa). Snake venom phosphodiesterase from Crotalus adamanteus was provided by Worthington Biochemical Corp. (Lakewood, NJ). Bovine spleen phosphodiesterase, nuclease P1 (NP1) from Penicillium citrinum, thymine, and 70% hydrogen fluoride in pyridine were all from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Ammonium citrate and 3-hydroxy-picolinic acid (3-HPA) for use as MALDI matrices were purchased from Fluka (Milwaukee, WI). “100%” D2O (99.96% atom %D) for NMR was from Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Milli-Q (18.2 mΩ/ cm) water was obtained from Millipore Corporation (Billerica, MA) Milli-Q water purification system. HPLC solvents were from Fisher (Fair Lawn, NJ).

Instrumentation

HPLC separation and analysis were carried out on System Gold HPLC BioEssential with a binary gradient 125 pump and a diode array 168 detector (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Fullerton, CA). An X-Bridge column (C18, 4.6 ×75 mm, 2.5 μm, 135 Ǻ) from Waters Corporation (Milford, MA) was used for reverse-phase HPLC. UVB (280-320 nm) irradiation was carried out with two Spectroline® XX-15B UV 15W tubes (312 nm) with peak UV intensity of 1,150 μW/cm2 at 25 cm and LONGLIFE™ filter glass from Spectronics Corporation (Westbury, New York). UVC irradiation was carried out with a model UVG-254 Mineralight lamp (254 nm, Ultra-Violet Products, Inc., San Gabriel, CA). MALDI mass spectra were collected on an Applied Biosystems 4700 tandem time-of-flight mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and ESI mass spectra were collected on an Thermo Finnigan LCQ classic mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA). NMR spectra were recorded with Varian Inova-600 (Varian Assoc., Palo Alto, CA) spectrometers and the data were processed off-line with Varian VNMR software.

UV irradiation of oligodeoxynucleotides

Oligodeoxynucleotides (ODNs) from IDT were used without further purification. ODN d(GTATTATGAGGTGC) in Milli-Q water and d(GTATCATGAGGTGC) in 10 mM acetate buffer, pH 4.8, (50 μM) were purged with nitrogen for 5 min and placed in a polyethylene Ziplock bag filled with nitrogen. The bags were placed on ice and irradiated for 2-2.5 h at a distance of about 1 cm from a UVB lamp. For the pH study the following buffers were used: 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 3.6), sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.6, 4.8, 5.0, 5.2, 5.4, 5.6), 10 mM sodium 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonate (MES) buffer (pH 5.7), 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), and 10 mM Tris (hydroxymethyl)-aminomethane-HCl (pH 7.8).

Reverse phase HPLC analysis and purification of products

Four gradients were used, all at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. Method A: 50 min 0-20% solvent B in solvent A (solvent A: 50 mM ammonium acetate, pH 6.8; Solvent B: 50% acetonitrile in 50 mM ammonium acetate, pH 6.8); Method B: 50 min 0-15% solvent B in solvent A (solvent A: 5% acetonitrile in 50 mM triethylammonium acetate, pH 7.0; solvent B: 50% acetonitrile in 50 mM triethylammonium acetate, pH 7.0); Method C: 50 min 0-20% solvent B in solvent A (solvent A: 50 mM triethylammonium acetate, pH 7.0; solvent B: 50% acetonitrile in 50 mM triethylammonium acetate, pH 7.0); Method D: 100% Milli-Q water. The effluent was monitored at 260 nm for Methods A-C, and 205 nm for Method D.

Thermal and hydrolytic stability assay

The thermal and hydrolytic stability of the photoproducts were determined with 100 μl of 50 μM UVB irradiated ODN in 10 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH = 4.8) in an Eppendorf microcentrifuge tube in a 37 °C water bath.

Exonuclease-coupled MS sequencing

The ODN (150 pmol) was incubated with 0.01 units of snake venom phosphodiesterase in 8 μL of 10 mM ammonium citrate (pH at 9.4) at 37 °C or with 0.01 units of bovine spleen phosphodiesterase in 8 μL of Milli-Q water at room temperature. Aliquots (0.5 μL) were removed at various time points and placed in dry ice for 1 min after which they were mixed with 0.5 μL of MALDI matrix solution. The premixed solution (0.5 μL) was spotted on an ABI-192-AB stainless steel plate and allowed to dry at ambient temperature. The matrix solution consisted of 70 mg of 3-hydroxypicolinic acid and 10 mg of ammonium citrate in 700 μL of 50% aqueous acetonitrile. MS spectra were acquired in the reflector positive ion mode with an accelerating voltage of 20 kV. Each spectrum was averaged by summing 8 sub-spectra each of which consisted of 125 shorts/subspectrum.

Nuclease P1-coupled MALDI-TOF-MS assay

Nuclease P1 (NP1) digestion was carried out by adding 1 μL of 1 unit/μL aqueous NP1 to 1.8 nmol of ODN in 10 μL of Milli-Q water. After 5 h at room temperature, the solution was submitted to reverse phase HPLC using method C. The product eluting after the mononucleotides was isolated, dried, and redissolved in MilliQ water to give a 50 μM solution and mixed with an equal amount of the MALDI matrix. MS experiments were carried out in the reflector positive ion mode as described above. MS/MS experiments were carried out at medium pressure in the positive ion mode. The accelerating voltage was 8 kV and 15 kV for source 1 and source 2, respectively; air was the collision gas. Each spectrum was averaged by summing 8 sub-spectra, each of which consisted of 125 shots/spectrum. Data were collected with the metastable ion suppressor on, and 3 sub-spectra used for the precursor whose intensity was optimized. The precursor ion was selected with a relative mass window that was 50-fold the specified resolution (full-width at half maximum peak height) of the selected precursor.

Glycosidic bond hydrolysis

Acid catalyzed glycosidic bond hydrolysis was carried out by adding 40 μL of 70 % hydrogen fluoride in pyridine to 65 μg of ODN in a 1.5 mL of a polyethylene micro-centrifuge tube. The solution was incubated at 37 °C for 3 h, diluted to 1 mL with Milli-Q water, neutralized with 120 mg calcium carbonate by vortexing for 5 min, and filtered through an Xpertek 13 mm 0.45 μm nylon syringe filter (P.J. Cobert Associates, Inc., St Louis, MO). The filtrate was evaporated in a SpeedVac (Thermo Savant, Holbrook, NY) and redissolved in 100 μL of Milli-Q water for HPLC analysis with Method D. For the hydrolysis of authentic T[c,s]T and T[t,s]T dinucleotide intermediates, 23 μL of 70% hydrogen fluoride in pyridine was added to 45 μg of the dinucleotide intermediate in a microcentrifuge tube and incubated in 37 °C water bath for 3 h. The hydrolysis solution was diluted to 600 μL aqueous solution with Milli-Q water and neutralized by adding 69 mg calcium carbonate. After filtering and drying, the residue was redissolved in 300 μL Milli-Q water and analyzed by HPLC with Method D. A mixture of authentic thymine cyclobutane dimers for comparison was prepared by irradiating 2 mM thymine in 5% acetone aqueous solution with UVB for 4 h as described above for the ODNs.

ESI-MS and MS/MS assay

ESI-MS and MS/MS experiments were carried out in the positive ion mode with the ion-trap mass spectrometer. A solution of 80/20 (v/v) methanol/water with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) was used as the spray solvent. The spray voltage was 4.6 kV. The capillary voltage and temperature were 46 V and 200 °C, respectively. MS/MS experiments were done by using collision activated dissociation (CAD) with helium as collision gas. The mass window for precursor-ion selection was 3 m/z units. The collision energy was 30% of the maximum value, corresponding to a peak-to-peak excitation voltage of 5 V. Approximately 20 scans were averaged for each spectrum. Each scan consisted of 3 microscans with a maximum injection time of 300 ms.

NMR Analysis

Approximately 0.26 μmol of photoproduct I purified by HPLC method B was dissolved in “100%” D2O for 1D and 2D NMR analysis. Proton chemical shifts were measured in parts per million (ppm) downfield from the H resonance of an internal 3-(trimethylsilyl)propionic acid (TSP) standard and 31P chemical shifts were measured using trimethyl phosphate as an external reference. The total correlation (TOCSY) spectra were recorded by using an MLEV-17 mixing sequence of 120 ms flanked by two 2 ms trim pulses. Phase-sensitive 2D spectra were obtained by employing the hypercomplex method. A 2 × 256 × 2048 data matrix with 16 scans per t1 increment was collected. Gaussian and sine-bell apodization functions were used in weighting the t2 and t1 dimensions, respectively. After two-dimensional Fourier transformation, the 2048 × 2048 frequency domain representation was phase and baseline corrected in both dimensions. The NOESY spectrum resulted in a 2 × 256 × 2049 data matrix with 32 scans per t1 increment. Spectra were recorded with 80, 150, 250 and 450 ms mixing times. The hypercomplex method was used to yield phase-sensitive spectra. The time domain data were zero-filled to yield a 2048 × 2048 data matrix and were processed with digital filtering to minimize the water signal. The proton-detected heteronuclear 1H-31P HSQC spectrum was recorded by using a 20 ms delay period in the sequence. The 90° 1H pulse width was 6.5 μs and the 90° 31P pulse width was 18 μs. The proton spectral width was set to 1500 Hz and the 31P spectral width was set to 700 Hz. Phase-sensitive 2D spectra were obtained by employing the hypercomplex method. A 2 × 128 × 2048 data matrix with 64 scans per t1 value was collected. Gaussian line broadening was used in weighting both the t2 and the t1 dimension. After two-dimensional Fourier transform, the spectra (256 × 2048 data points) were phase and baseline corrected in both dimensions.

Results and Discussion

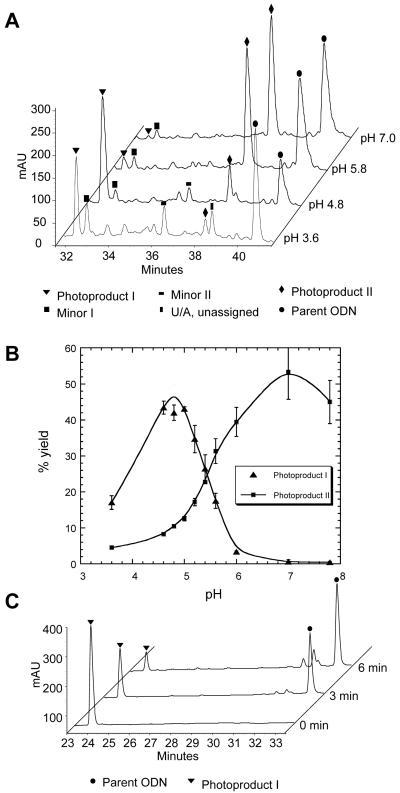

Our interest in the photochemistry of the 14-mer d(GTATCATGAGGTGC) sequence was to prepare a T[c,s]C cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer for mechanistic studies of C→T mutations. The sequence has a single adjoining dipyrimidine site and is devoid of any stable secondary structure based on Watson Crick base pairing. Irradiation of the ODN with UVB light led to the formation of two major photoproducts, I and II, with retention times of 32.5 min and 38.5 min, respectively, compared to 40.9 min for the starting ODN (Figure 2A). Photoproduct I was produced with an unexpectedly high yield and had an unusually short retention time compared to other known adjacent T=T photoproducts. No such unusual products were previously observed when the identical sequence containing a 5-methyl-CT site in place of the TC site had been irradiated.18 In trying to understand why this TC sequence but not the previous mCT sequence led to this unusual product, we discovered that the pH of the solution that was irradiated was much lower than 7. A systematic study of pH (Figure 2B) showed that photoproduct I was produced most efficiently at a pH of approximately 5, whereas photoproduct II was favored at higher pH. MALDI-TOF analysis of the two photoproducts showed that they both have the same mass (within 3 ppm) as the parent ODN, indicating that they are isomeric photoproducts.

Figure 2.

HPLC analysis of photoproduct formation and reversal A) Reverse phase HPLC analysis with method A of UVB irradiation mixture of d(GTATCATGAGGTGC) at different pHs. Accurate m/z of the molecular ion [M+H]+ of the unknown photoproduct I is 4317.7778 with mass error of +3.1 ppm comparing with a calculated value of 4317.7644. B) Plot of the percent yield (calculated by peak area) of photoproduct I and the photoproduct II-Dewar photoproduct as a function of pH. The error bars were produced from three independent trails of experimental data. C) Reverse phase HPLC analysis with method B of the products of 254 nm irradiation of photoproduct I for 0, 3 and 6 min. The major reversion product was confirmed to be the parent ODN by MALDI analysis of the PDE I and PDE II digestion products. The smaller peaks eluting around 32 min are attributable 254 nm irradiation products of the reversal product, as confirmed by separate irradiation of the parent ODN.

Photoreversal of Photoproducts I and II

Irradiation of photoproducts with 254 nm can be used to distinguish various classes of DNA photoproducts. Cyclobutane dimers are reverted to the parent nucleotides, whereas Dewar photoproducts are reverted back to the parent (6-4) photoproduct. When a pure sample of photoproduct II was irradiated with 254 nm light, it was converted to the (6-4) photoproduct which could be identified by its characteristic absorption at 325 nm (data not shown).19,20 This indicates that photoproduct II is likely to be a Dewar valence isomer of the (6-4) product of the TC site. This was confirmed by independently preparing the T(6-4)C photoproduct by 254 nm irradiation of the parent ODN and converting the (6-4) photoproduct to its Dewar valence isomer by irradiation with Pyrex-filtered medium pressure mercury arc light. When photoproduct I was irradiated with 254 nm light, however, it was converted to the parent ODN (Figure 2C) suggesting that it was a cyclobutane dimer, or some other [2+2] cycloadduct, but not of adjacent nucleotides, which would have a longer retention time.

Thermal and Hydrolytic Stability of Photoproduct I

C/mC-containing cis-syn cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer photoproducts readily deaminate in neutral or acidic aqueous solution to afford U/T containing cis-syn dimers.18,21,22 This deamination reaction is accompanied by an increase in mass of 1 u. MS analysis of photoproduct I recovered after 1, 5 and 20 h of incubation at pH 4.8 at 37 °C revealed that the molecular weight was unchanged, excluding the possibility that photoproduct I was a T[c,s]C product.

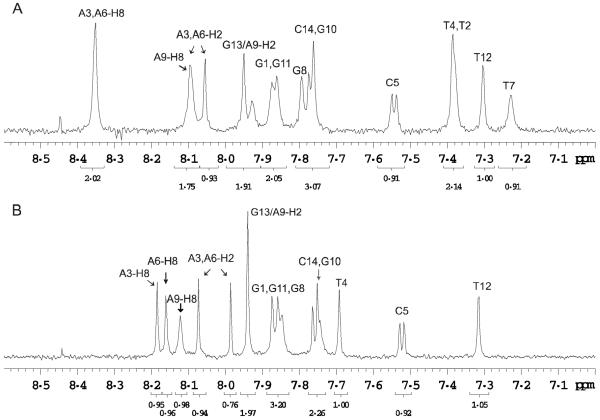

1H NMR Analysis of Photoproduct I

Comparison of the aromatic region of the one dimensional 1H NMR spectra of photoproduct I and the parent ODN showed that the characteristic H6 protons of the two C’s were present in both cases (confirmed by 2D NMR). On the other hand, two aromatic TH6 protons were missing, consistent with cyclobutane dimer formation between two non-adjacent T’s which would shift the H6 signal upfield (Figure 3). The two upfield shifted H6 protons could be identified through correlations to two methyl groups by 2D NMR spectroscopy (vide infra) and had shifts of 3.59 and 3.62 ppm (Table S1).

Figure 3.

NMR spectra of photoproduct I and the parent ODN. 1D 1H-NMR spectra of the aromatic region of A) the parent ODN d(GTATCATGAGGTGC) and B) photoproduct I at room temperature in D2O. The spectra show that two of the four aromatic TH6 proton signals are missing in photoproduct I indicating formation of a T=T photoproduct.

DNA Ladder Sequencing

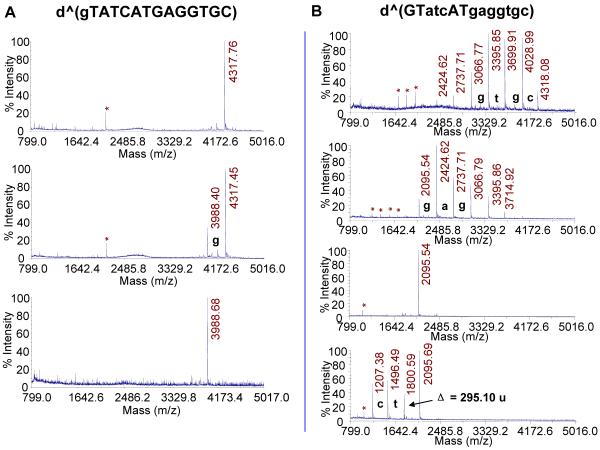

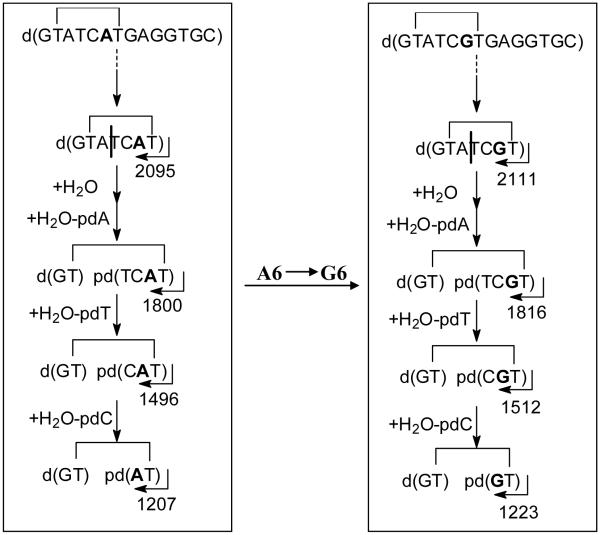

To determine which two of the four non-adjacent T’s had photodimerized we used a previously developed exonuclease-coupled MS method to map DNA damage sites. This method employs phosphodiesterase type I and II enzymes to degrade ODNs from the 3′- and 5′-directions respectively, and MALDI to assay the fragments formed.23-26 This method can map abasic sites and adjacent photodimers, both of which terminate the progressive enzymatic cleavage.27-29

For 5′-exonucleolytic cleavage we used bovine spleen phosphodiesterase (BSP), which removes 3′-nucleotide monophosphates from DNA with a free 5′-OH. The activity depends on contact with both the 5′- and 3′- bases flanking a phosphodiester bond, although contact with a 3′-base is not absolutely required30,31 Digestion of the parent ODN gave the expected fragments corresponding to the sequential loss of 3′-nucleotide monophosphates (+H2O-dNp) up to G11 in 5.5 minutes from which the majority of the sequence could be confirmed (Figure S1A). When the same procedure was carried out with BSP on photoproduct I (Figure 4A), excision of G1 was much slower than that of normal nucleotides and degradation terminated immediately after loss of only G1, indicating that one of the T’s involved in the unknown photodimer was T2. The reduced activity of BSP for cleaving G1 of the photoproduct containing DNA is consistent with the presence of a damaged base 3′ to the phosphodiester bond which would interfere with binding to the enzyme. Subsequent cleavage is then inhibited by the presence of a damaged base that is 5′ to the phosphodiester bond.

Figure 4.

Exonuclease-coupled MS ladder sequencing of photoproduct I. A) BSP digestion coupled MALDI sequencing at room temperature for 0 min, 110 min, and at 37 °C for 40 min (top to bottom). B) SVP digestion coupled MALDI sequencing at 37° for 1, 2.5, 5.5, and 85 min (top to bottom). The mass losses of 289.05, 304.05, 313.06, and 329.05 u correspond to exonucleotytic cleavage of pdC, pdT, pdA, and pdG, respectively (+ H2O - pdN). Nucleotides that were enzymatically removed are represented by small-case letters. Peaks labeled with “*” are doubly charged digestion fragments. “^” indicates photodamaged ODNs.

For 3′-exonucleolytic cleavage, we used snake venom phosphodiesterase (SVP) which removes 5′-monophosphates from the 3′-end by binding to the base to the 3′-side of the phosphodiester bond to be cleaved.30 With the undamaged parental DNA, sequential excision of 5′-nucleotide monophosphates (+ H2O - pdN) from the 3′-end was observed up to T4 in 5.5 minutes (Figure S1B). With photoproduct I, sequential loss of seven nucleotides up to and including G8 was observed within the same time frame indicating that T7 was the other base involved in the photodimer which prevented the enzyme from binding T7 and cleaving to its 5′-side (Figure 4B). Upon extended incubation for more than an hour, however, a loss of 295 u was observed, followed by successive losses corresponding to removal of pdT and pdC. The loss of 295 u can be attributed to the sum of masses resulting from rate limiting endonucleotytic cleavage of the loop between the dimer at the A3T4 linkage (+H2O), presumably via binding to T4, followed by rapid 3′-exonucleolytic excision of pdA3 (+H2O - pdA) (Scheme 1). Endonuclease activity is intrinsic to venom phosphodiesterase32 but is usually only observed in reactions with excess SVP or when long incubation times are used.28,33 Subsequent loss of pT4 and pdC5 could be explained by the endonucleolytic cleavage steps after which no further enzymatic degradation occurred since there were no more undamaged bases 3′ to a phosphodiester bond.

Scheme 1.

Proposed enzymatic cleavage pathway by SVP for the T2[c,a]T7 photoproducts of the original sequence and mut6 (A6G).

Support for the proposed cleavage pathway and mechanism comes from SVP degradation of the same photoproduct in a different sequence context in which A6 was replaced by a G (Table 1, mut6). As with the original sequence, degradation occurred rapidly until reaching T7, after which the same mass loss of 295 u corresponding to rate limiting endonucleolytic cleavage of the loop between A3T4 followed by exonucleolytic cleavage of pdA was observed, followed by loss of pT4 and pdC5 (Scheme 1). Exonucleolytic cleavage of the photoproduct I in the original sequence context by bovine intestinal mucosa phosphodiesterase (BIMP), another phosphodiesterase I enzyme used for DNA sequencing,34,35 also resulted in cleavage past T7. Unlike SVP, endonucleolytic cleavage of the loop took place at T4C5 and was followed by combined loss of pT by 3′-exonuclease activity and the 5′-phosphate of C5 by a contaminating phosphatase. This was then followed by loss of pdA by 3′-exonuclease activity and then dC by endonuclease activity followed by rapid loss of the 5′-phosphate by the contaminating phosphatase (Figure S2).

Table 1.

Photoproduct yields for mutant sequences of d(GTATCATGAGGTGC). ODNs (50 μM) were irradiated at pH 4.8 for 2.5 h at 0°C. Mutations are underlined. Only photoproducts detected in greater than 3 % yield are reported

| Name | Sequence | % T2[c,a]T7 | % T2[c,s]T4 | % T4[Dewar]C5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | GTATCATGAGGTGC | 42 | 5 | 10 |

| Mut1 | GTGTCATGAGGTGC | 5 | 4 | 6 |

| Mut2 | GTAACATGAGGTGC | |||

| Mut3 | GTAGCATGAGGTGC | |||

| Mut4 | GTATAATGAGGTGC | |||

| Mut5 | GTATGATGAGGTGC | |||

| Mut6 | GTATCGTGAGGTGC | 30 | 16 | |

| Mut7 | GTATCATAAGGTGC | 4 | 6 | 6 |

| Mut8 | GTATCATGAGGT - - | 7 | 17 | |

| Mut9 | GTATCATGAG - - - - | 9 | 30 | |

| Mut10 | GTATCATG - - - - - - | 13 | 7 |

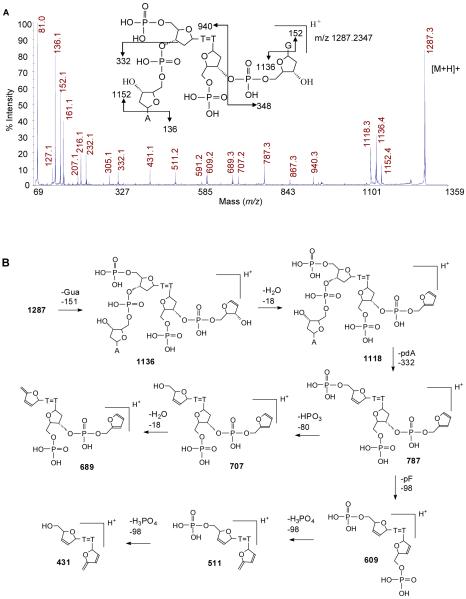

Nuclease P1-Coupled MALDI-TOF MS Assay of Photoproduct I

To confirm that T2 and T7 are actually involved in the photoproduct, we used an endonuclease-coupled MS assay that we previously developed to identify and quantify adjacent dipyrimidine photoproducts.18,36,37 Nuclease P1 (NP1) has both endonuclease activity and 3′-phosphatase activity.38 It has a binding pocket that is specific for the bases in DNA and, upon binding to the 5′-base, catalyzes hydrolysis of the phosphodiester bond to yield deoxynucleotides with a 3′-hydroxyl group.30,31,39,40 Because the bases in dipyrimidine photoproducts are covalently linked together, NP1 cannot bind to either base of the photoproduct, and hence cannot cut to the 3′-side of either nucleotide of the photoproduct. As a result, NP1 degradation of ODNs containing a dipyrimidine photodimer of adjacent bases gives a photodimer-containing trinucleotide of the form pd(Py=PyN).

NP1 digestion of the parent ODN afforded, as expected, major products corresponding to monomers eluting at 3.0 (pdC), 10.0 (pdT), 10.6 (dG), 11.0 (pdG), and 15.6 (pdA) min when using HPLC method C. NP1 digestion of photoproduct I, however, gave an additional product eluting at 33.3 min. This component, after isolation, gave an [M+H]+ by MALDI of m/z 1287.2347, which is within 3 ppm of the calculated value of 1287.2312 for pd(T[A])=pd(T[G]). Such a tetranucleotide can only result from NP1 digestion of a thymidine dimer formed between T2 and T7 or between T2 and T12, both of which have T’s followed by an A and a G. Involvement of T4 is ruled out because it is followed by C not G. Dimer formation between T2 and T12 is ruled out by SVP digestion which showed no inhibition at T12, but did show an unusual product when degrading past T7.

To confirm the assignment of the NP1 digestion product to pd(T2[A3])=pd(T7[G8]), we carried out MALDI-TOF-MS/MS (Figure 5A). Key product ions were as follows: [Ade+H]+ (m/z 136.1), [Gua+H]+ (m/z 152.1), [pdA+H]+ (m/z 332.1), [M-Ade+H]+ (m/z 1152.4), [M-Gua+H]+ (m/z 1136.4), and [M-pdG+H]+ (m/z 940.3). The other product ions are also consistent with the structure as shown in the more detailed fragmentation scheme in Figure 5B.

Figure 5.

Mass spectrometry analysis of the NP1 digestion product of photoproduct I. A) MALDI-TOF-MS/MS spectrum of parent ion [M+H]+ (m/z 1287.3) of HPLC purified ultimate NP1 digestion product of photoproduct I. B) Proposed fragmentation pathway.

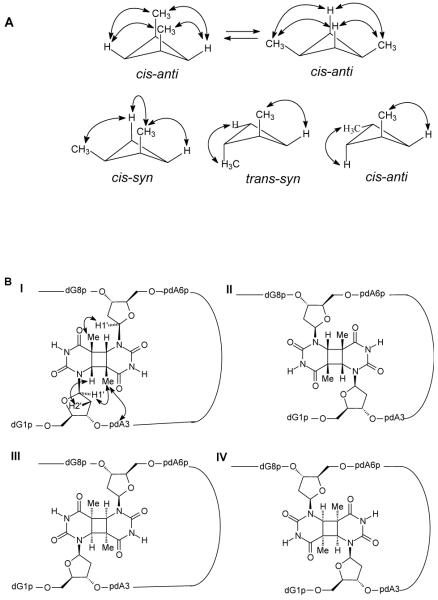

Stereochemistry of the cyclobutane dimer in photoproduct I

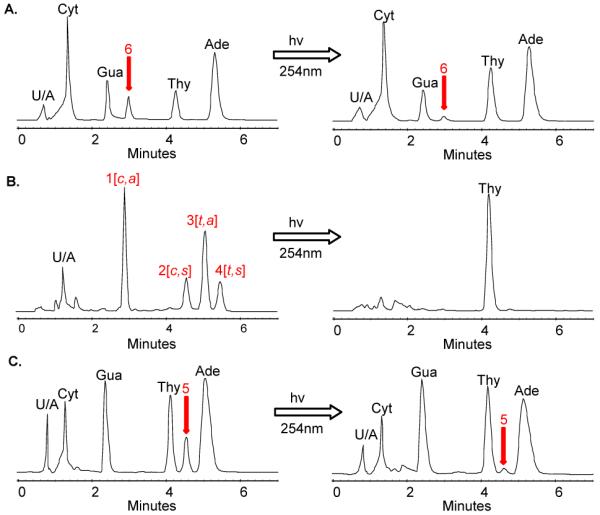

To determine the relative stereochemistry of the non-adjacent dimer, the thymine dimer was released from photoproduct I by acid-catalyzed glycosidic bond hydrolysis and was compared with authentic samples of the four possible thymine dimers: cis-syn, d,l-trans-syn, d,l-cis-anti, and d,l-trans-anti. The authentic products were produced by sensitized UVB irradiation of thymine in aqueous acetone and separated by reverse phase HPLC according to a recently described procedure.41 Thy[c,s]Thy, Thy[t,s]Thy, Thy[c,a]Thy, and Thy[t,a]Thy were produced in nearly quantitative yield and eluted at 4.2, 5.2, 2.6, and 4.8 min respectively on reverse-phase HPLC with water (Figure 6B left). ESI-MS confirmed them to be thymine dimers as all gave [M+H]+ ions of m/z 253.1. Irradiation of the mixture with 254 nm light prior to HPLC caused nearly quantitative photoreversal of all the dimers back to thymine (Figure 6B, right).

Figure 6.

Structure correlation of the cyclobutane thymine dimer. The acid hydrolysis products of photoproduct I were compared to an authentic mixture of cyclobutane thymine dimers by HPLC using method D. HPLC traces of A) the acid hydrolysis products of photoproduct I, B) the product mixture from the irradiation of thymine, and C) the acid hydrolysis products of the cis-syn TT dimer containing photoproduct d(GTAT[c,s]TATGAGGTGC). To the left are the HPLC traces before irradiation with 254 nm light, and to the right, after irradiation. The peaks labeled with U/A are unassigned peaks.

To release the thymine dimer from photoproduct I, we used hydrogen fluoride in pyridine which cleaves both the N-glycosidic and phosphodiester bonds of both undamaged and photodimer-containing DNA without degrading the bases or the photodimers.42-44 To test the method, we used authentic samples of d(T[c,s]T) and d(T[t,s]T) dinucleotide intermediates used in the synthesis of photodimer building blocks for DNA synthesis.45-47 The hydrolysis product of the cis-syn dimer eluted with the component corresponding to peak 2 and while the hydrolysis product of the trans-syn dimer eluted with the component corresponding to peak 4, confirming our original assignment of the thymine dimers based on their relative retention time (data not shown).41 Hydrolysis of an ODN 14-mer containing authentic cis-syn dimer d(GTAT[c,s]TATGAGGTGC), gave peak 5 (Figure 6C, left) which eluted with the same retention time as Thy[c,s]Thy. Photoreversal with 254 nm light resulted in disappearance of the cis-syn dimer peak 5 and an increase in the thymine peak (Figure 6C, right). Hydrolysis of photoproduct I, however, released a product peak 6 (Figure 6A, left) which had the same retention time as the authentic Thy[c,a]Thy, establishing it as a cis-anti thymine dimer. Photoreversal with 254 nm light, likewise, resulted in disappearance of the dimer peak 6, and an increase in the thymine peak (Figure 6A, right).

To confirm further that photoproduct I has the cis-anti and not the cis-syn stereochemistry, we compared the tandem MS of the hydrolysate of photoproduct I with that of the cis-syn thymine dimer-containing ODN 14-mer, and the authentic Thy[c,a]Thy (peak 1) and Thy[c,s]Thy (peak 2). The thymine dimer molecular ion [M+H]+ of m/z 253.1 is known to undergo different fragmentation for the cis-syn and cis-anti stereoisomers.48 MS/MS of the cis-syn stereoisomer produced a most abundant m/z 210.0 ion by loss of CHNO (43 u) whereas the cis-anti stereoisomer produced a most abundant ion of m/z 127.1 suggesting that reversion to thymine occurs under the collision activation conditions (Figure S3). Reversion of the cis-anti, but not the cis-syn isomer during MS/MS is consistent with the thermal instability of the anti stereoisomers compared to the syn stereoisomers.41,49 MS/MS of the precursor ion of m/z 253.1 produced by photoproduct I hydrolysate afforded the ion of m/z 127.1 characteristic of the cis-anti stereochemistry.

Minor Photoproducts

Two minor photoproducts, minor I and minor II (Figure 2A) were also analyzed by nuclease P1-coupled MS/MS, and exonuclease-coupled MS sequencing, and by comparison of acid hydrolysates to the authentic thymine dimers (Figure S4-8). On the basis of these data, minor I was assigned to a T2[c,s]T4 non-adjacent dimer, and minor II to a T2[t,a]T7 non-adjacent dimer.

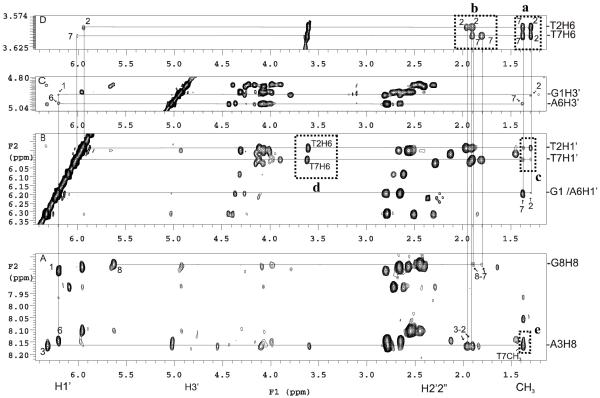

Absolute Stereochemistry of Photoproduct I by 2D NMR analysis

We assigned proton chemical shifts of the parent ODN and photoproduct I by a standard sequential assignment strategy based on TOCSY and NOESY spectra (Figure 7 and Figure S10-13). The assignments confirm that the photodimer formed between T2 and T7. Owing to a loss of aromaticity of the T2 and T7 bases upon the formation of the cyclobutane dimer, the chemical shift of the H6 protons were significantly shifted upfield. As a result, intra-residue aromatic H6-CH3 crosspeaks were not observed for T2 and T7, but were observed for T4 and T12 (Figure S12B). Likewise, aromatic H6/H8 (i)-H1′ (i-1) crosspeaks used in the sequential assignment of DNA were not observed for T2-G1 and T7-A6 (Figure S12A).

Figure 7.

Section of NOESY spectra of photoproduct I at 25 °C. A) Cross correlation between the H6, sugar and methyl protons of T2 and T7. B) Connection of the preceding G1, A6-H1′, T2, T7-H1′ to T2/T7 methyl protons. C) Connection of the preceding G1, A6-H3′ to T2/T7 methyl protons, and D) Connection of the T2/T7 H6-H2′2”/CH3 protons. See text for explanation of the crosspeaks enclosed in the dotted boxes.

The methyl groups of the thymine dimer were assigned based on the observable G1 H1′/H3′-T2CH3 and A6 H1′/H3′-T7CH3 crosspeaks located in the most upfield shifted methyl region (Figure 7B, C). The H6′s of the thymine dimer were then assigned by tracing two intra-residue H6-5CH3 crosspeaks between 3.5-3.7 ppm and 1.3-1.4 ppm (Figure 7D). The corresponding intra-residue T2/T7 H6-H2′2” NOEs were used to reestablish the sequential A3-T2 and G8-T7 pathway through the joint vertical line in the 1.8-2.0 ppm region (Figure 7A, D). In this way, T2H6 could be assigned to 3.59 ppm and T7H6 to 3.62 ppm. The observation of four strong T2/T7 H6-CH3 crosspeaks (Figure 7D, dotted box a) is consistent with a cis-anti stereochemistry for the dimer for which each H6 proton is within NOE distance of each of the methyl groups (Figure 8A). A cis-syn dimer, on the other hand, generally shows only three crosspeaks because of the puckered ring conformation which results in one long, NOE inactive H-CH3 distance. Likewise, a trans-syn or trans-anti dimer generally shows only two crosspeaks. The presence of T2H1′-T7CH3 and T7H1′-T2CH3 (Figure 7B, dotted box c) and T2H1′-T2H6 and T7H1′-T7H6 (Figure 7B, dotted box d) crosspeaks and the absence of T2H1′-T7H6 and T7H1′-T2H6 crosspeaks is also consistent with an anti orientation of C5-C6 bonds of the dimer as illustrated for Structure I in Figure 8B.

Figure 8.

Structure and stereochemistry of the cis-anti stereoisomers of the T2 [c,a]T7 product. A) Conformations of the cyclobutane ring of cis-anti, cis-syn, trans-syn, trans-anti thymine dimers and the NOE active H6-CH3 pairs. B) The four possible cis-anti T2-T7 cyclobutane dimers showing how the observed NOEs are consistent with structure I.

Given the cis-anti stereochemistry of the cyclobutane dimer, there are still four possible structures of the T2[c,a]T7 photoproduct to consider (Figure 8B). Structures I and II would result from photodimerization of the two T’s in anti glycosyl conformations with either a 5′- or 3′-staggered stacking arrangement. Structures III and IV would result from photodimerization of the two T’s in a syn glycosyl conformation with either a 5′- or 3′-staggered stacking arrangement. The presence of a crosspeak between A3H8 and T7CH3 (Figure 7A, dotted box e) is consistent with either structure I or III which places T7 near A3 (Figure 8B, Structure I). The presence of a strong intra-residue crosspeak between H6 - H2′2” for both T2 and T7 (Figure 7D, dotted box b) at various mixing times ranging from 80 ms to 450 ms is consistent with an anti glycosyl conformation of structure I but not structure III (Figure 8B), strongly suggesting that the photoproduct has structure I.

Photodimerization in different sequence contexts and concentrations

To determine the sequence specificity of the photodimerization reaction resulting in the T2[c,a]T7 product, we irradiated an additional ten ODNs corresponding to site-specific mutations within the loop region, and deletions of the sequence to the 3′-side of the photoproduct (Table 1) at pH 4.8. Only irradiation of mut6, in which the A preceding T7 was mutated to G produced the T2[c,a]T7 non-adjacent dimer in a similar high yield as the parent sequence (Figure S9). The requirements for having A3, T4, C5, G8 and the 3′-end of the sequence to produce the photoproduct in high yield indicates that a set of highly specific base pairing interactions are required to form the necessary folded structure.

To determine whether the folded structure leading to the photoproduct was intra-molecular or involved the assembly of two or more strands, we determined the photoproduct yield at two different concentrations. To assure that the DNA in the two samples absorbed the same amount of light, we used samples that differed in concentration by a factor of 10 and placed them in quartz cuvettes with 0.1 and 1 cm pathlengths, so that they each had an absorbance of 0.3 at 260 nm corresponding to absorption of 50% of the incident light. Thus 100 μL of a 20 μM solution at pH 4.8 in a 0.1 cm pathlength quartz cuvette and 1000 μL of a 2 μM solution in a 1 cm cuvette were irradiated side by side for 1h with ice cooling to give the product in 32% and 14% yields respectively, indicating that the folded structure involves two or more strands.

Conclusions

Based on the photoreactivity, spectroscopy, and spectrometry data we determined the structure of the new photoproduct to be a non-adjacent cis-anti cyclobutane dimer formed between T2 and T7 with the absolute stereochemistry depicted by structure I (Figure 8B). This is the first inter-strand type of cyclobutane dimer to be isolated and characterized in DNA. There is no predictable stable Watson-Crick folded structure of d(GTATCATGAGGTGC) that can explain the high yield formation of this product. Based on our mutagenesis and concentration studies, we speculate that the sequence adopts a higher order folded structure at pH 5 by inter- and intra-molecular base pairing between strands, which remains to be elucidated. The formation of this inter-strand photoproduct also suggests that such type of photoproducts might also form in biologically important higher order DNA structures such as between loops of G-quartet structures in telomeres and promoters, and between strands in i-motif structures.16,17 The methods described herein could be used to identify and map such photoproducts which could be used as a probe to distinguish between various folding structures in solution and in vivo. Once the structure-activity relationships of inter-strand photoproduct formation are better understood, it is conceivable that it could also be used for the assembly and/or characterization of higher order DNA structures for nanotechnological applications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ajay Kshetry for providing samples of authentic cis-syn and trans-syn dinucleotide intermediates. We also thank a reviewer for an interpretation of an unusual mass loss that led us to explanations for the phosphodiesterase I cleavage products past the dimer. This research was supported by NIH Grant CA40463 and by the Washington University NIH Mass Spectrometry Resource (Grant No. P41 RR000954) and Washington University NMR facility (Grant No. RR1571501).

Abbreviations

- (6-4)

pyrimidine-(6-4)-pyrimidone

- Ade

adenine

- BIMP

bovine intestinal mucosa phosphodiesterase

- BSP

bovine spleen phosphodiesterase

- [c,a]

cis,anti

- [c,s]

cis,syn

- CPD

cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer

- Cyt

cytosine

- Dewar

pyrimidine-(6-4)-Dewar pyrimidone

- ESI

electrospray ionization

- Gua

guanine

- MALDI

matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization

- MS

mass spectrometry

- NP1

nuclease P1

- ODN

oligodeoxynucleotide

- PDE

phosphodiesterase

- Py

pyrimidine

- Py=Py

pyrimidine dimer

- RP-HPLC

reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography

- SVP

snake venom phosphodiesterase

- Thy

thymine

- [t,a]

trans,anti

- [t,s]

trans,syn

References

- (1).Pfeifer GP, You YH, Besaratinia A. Mutat. Res. 2005;571:19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Cleaver JE, Crowley E. Front. Biosci. 2002;7:d1024–1043. doi: 10.2741/A829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Sarasin A. Mutat. Res. 1999;428:5–10. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(99)00025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Grossman D, Leffell DJ. Arch. Dermatol. 1997;133:1263–1270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Taylor J-S, Taylor and Francis Group . In: DNA Damage Recognition. Siede W, Kow YW, Doetsch PW, editors. New York: 2006. pp. 67–94. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Cadet J, Sage E, Douki T. Mutat. Res. 2005;571:3–17. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Begley TP. In: Comprehensive Natural Products Chemistry. Poulter CD, editor. Vol. 5. Elsevier; New York: 1999. pp. 371–399. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Taylor J-S. Pure Appl. Chem. 1995;67:183–190. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Cadet J, Vigny P. In: Bioorganic Photochemistry. Morrison H, editor. Vol. 1. Wiley; New York: 1990. pp. 1–272. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Douki T, Cadet J. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2003;2:433–436. doi: 10.1039/b300173c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Douki T, Laporte G, Cadet J. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3134–3142. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Nguyen HT, Minton KW. J. Mol. Biol. 1988;200:681–693. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90480-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Nguyen HT, Minton KW. J. Mol. Biol. 1989;210:869–874. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90114-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Lingbeck JM, Taylor JS. Biochemistry. 1999;38:13717–13724. doi: 10.1021/bi991035i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Love JD, Nguyen HT, Or A, Attri AK, Minton KW. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:10051–10057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Dai J, Carver M, Yang D. Biochimie. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2008.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Qin Y, Hurley LH. Biochimie. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2008.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Vu B, Cannistraro VJ, Sun L, Taylor JS. Biochemistry. 2006;45:9327–9335. doi: 10.1021/bi0602009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Hauswirth W, Wang SY. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1973;51:819–826. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(73)91388-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Taylor JS, Lu HF, Kotyk JJ. Photochem. Photobiol. 1990;51:161–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1990.tb01698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Celewicz L, Mayer M, Shetlar MD. Photochem. Photobiol. 2005;81:404–418. doi: 10.1562/2004-06-15-ra-201.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Lemaire DGE, Ruzsicska BP. Biochemistry. 1993;32:2525–2533. doi: 10.1021/bi00061a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Schuette JM, Pieles U, Maleknia SD, Srivatsa GS, Cole DL, Moser HE, Afeyan NB. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 1995;13:1195–1203. doi: 10.1016/0731-7085(95)01534-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Bentzley CM, Johnston MV, Larsen BS, Gutteridge S. Anal. Chem. 1996;68:2141–2146. doi: 10.1021/ac951213n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Smirnov IP, Roskey MT, Juhasz P, Takach EJ, Martin SA, Haff LA. Anal. Biochem. 1996;238:19–25. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Owens DR, Bothner B, Phung Q, Harris K, Siuzdak G. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1998;6:1547–1554. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(98)00098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Zhang LK, Gross ML. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2002;13:1418–1426. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(02)00701-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Zhang LK, Rempel D, Gross ML. Anal. Chem. 2001;73:3263–3273. doi: 10.1021/ac010042l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Zhang LK, Ren Y, Rempel D, Taylor JS, Gross ML. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2001;12:1127–1135. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(01)00291-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Weinfeld M, Liuzzi M, Paterson MC. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:3735–3745. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.10.3735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Weinfeld M, Soderlind KJ, Buchko GW. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:621–626. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.3.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Pritchard AE, Kowalski D, Laskowski M., Sr. J. Biol. Chem. 1977;252:8652–8659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Bourdat AG, Gasparutto D, Cadet J. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:1015–1024. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.4.1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Landt M, Everard RA, Butler LG. Biochemistry. 1980;19:138–143. doi: 10.1021/bi00542a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Garcia-Diaz M, Avalos M, Cameselle JC. Eur. J. Biochem. 1991;196:451–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb15836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Wang Y, Gross ML, Taylor JS. Biochemistry. 2001;40:11785–11793. doi: 10.1021/bi0111552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Wang Y, Taylor JS, Gross ML. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1999;12:1077–1082. doi: 10.1021/tx9900831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Shishido K, Ando T. In: Nucleases. Linn SM, Roberts RJ, editors. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1982. pp. 155–209. [Google Scholar]

- (39).Volbeda A, Lahm A, Sakiyama F, Suck D. EMBO J. 1991;10:1607–1618. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07683.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Romier C, Dominguez R, Lahm A, Dahl O, Suck D. Proteins. 1998;32:414–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Shetlar MD, Basus VJ, Falick AM, Mujeeb A. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2004;3:968–979. doi: 10.1039/b404271a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Douki T, Voituriez L, Cadet J. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1995;8:244–253. doi: 10.1021/tx00044a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Lipkin D, Phillips BE, Abrell JW. J. Org. Chem. 1969:1539–1547. [Google Scholar]

- (44).Lipkin D, Howard FB, Nowotny D, Sano M. J. Biol. Chem. 1963:2249–2251. [Google Scholar]

- (45).Taylor POJ-S. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3783–3786. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.19.3783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Taylor JS, Brockie IR. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:5123–5136. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.11.5123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Taylor JS, Brockie IR, O’Day CL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987:6735–6742. [Google Scholar]

- (48).Douki T, Court M, Cadet J. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biol. 2000;54:145–154. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(00)00009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Wang MNKSY. Tetrahedron. 1972;28:945–957. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.