Abstract

Objective

The optimal biphasic defibrillation dose for children is unknown. Postresuscitation myocardial dysfunction is common and may be worsened by higher defibrillation doses. Adult-dose automated external defibrillators are commonly available; pediatric doses can be delivered by attenuating the adult defibrillation dose through a pediatric pads/cable system. The objective was to investigate whether unattenuated (adult) dose biphasic defibrillation results in greater postresuscitation myocardial dysfunction and damage than attenuated (pediatric) defibrillation.

Design

Laboratory animal experiment.

Setting

University animal laboratory.

Subjects

Domestic swine weighing 19 ± 3.6 kg.

Interventions

Fifty-two piglets were randomized to receive biphasic defibrillation using either adult-dose shocks of 200, 300, and 360 J or pediatric-dose shocks of ~50, 75, and 85 J after 7 mins of untreated ventricular fibrillation. Contrast left ventriculograms were obtained at baseline and then at 1, 2, 3, and 4 hrs postresuscitation. Postresuscitation left ventricular ejection fraction and cardiac troponins were evaluated.

Measurements and Main Results

By design, piglets in the adult-dose group received shocks with more energy (261 ± 65 J vs. 72 ± 12 J, p < .001) and higher peak current (37 ± 8 A vs. 13 ± 2 A, p < .001) at the largest defibrillation dose needed. In both groups, left ventricular ejection fraction was reduced significantly at 1, 2, and 4 hrs from baseline and improved during the 4 hrs postresuscitation. The decrease in left ventricular ejection fraction from baseline was greater after adult-dose defibrillation. Plasma cardiac troponin levels were elevated 4 hrs postresuscitation in 11 of 19 adult-dose piglets vs. four of 20 pediatric-dose piglets (p = .02).

Conclusions

Unattenuated adult-dose defibrillation results in a greater frequency of myocardial damage and worse postresuscitation myocardial function than pediatric doses in a swine model of prolonged out-of-hospital pediatric ventricular fibrillation cardiac arrest. These data support the use of pediatric attenuating electrodes with adult biphasic automated external defibrillators to defibrillate children.

Keywords: ventricular fibrillation, defibrillation, pediatrics, left ventricular ejection fraction, myocardial dysfunction, postresuscitation

Recognition and treatment of ventricular fibrillation (VF) are underappreciated pediatric problems. Ventricular fibrillation occurs in 5% to 22% of pediatric out-of-hospital cardiac arrests and is the initial documented rhythm in 10% of pediatric in-hospital cardiac arrests (1–4).

Automated external defibrillators (AEDs) designed for adults are often the first defibrillators available for out-of-hospital cardiac arrests. Recognizing that some adult AEDs now have diagnostic algorithms that are accurate in children, recent international guidelines recommend that “For children 1 to 8 yrs of age the rescuer should use a pediatric dose-attenuator system if one is available. If the rescuer provides CPR to a child in cardiac arrest and does not have an AED with a pediatric attenuator system, the rescuer should use a standard AED” (5). A specific biphasic pediatric defibrillation dose was not stipulated. Notably, the standard weight-based dosing strategy for pediatric defibrillation that varies with each child’s weight cannot be set in AEDs (5). New commercially available technology has enabled the delivery of a pediatric dose, approximately one fourth to one third (50–86 J) of the standard adult energy output of the AED (6–10). This attenuated (i.e., pediatric) dosing strategy is effective in pediatric piglet models of VF (6, 8–10) and in children (7).

In an earlier study comparing pediatric-dose and adult-dose defibrillation in piglets, we found worse postresuscitation myocardial dysfunction and 24-hr neurologic outcome in the adult-dose group but no difference in 24-hr survival between groups (8). We undertook the present study, substantially extending the sample size of our previous work, to more clearly determine whether the postresuscitation dysfunction, survival, and neurologic outcomes of the two groups differ. Because postresuscitation myocardial dysfunction occurs commonly after successful resuscitation from cardiac arrest and is known to be a major cause of death in the postresuscitation phase, our primary end point was left ventricular function 4 hrs after defibrillation. Secondary end points included postresuscitation myocardial damage (i.e., abnormal plasma troponin levels), return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), survival to 24 hrs, and 24-hr neurologic outcome. We hypothesized that adult defibrillation doses would result in worse postshock myocardial function and greater myocardial damage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal Preparation

The University of Arizona Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved this experimental protocol. The animal preparation and instrumentation have been detailed previously (8). Briefly, female Yorkshire swine, of weight ranging from 12 to 26 kg, to model 4- to 8-yr-old children, were anesthetized with 5% isoflurane anesthetic in oxygen administered by nose cone. A tracheal tube was placed orally, and minute ventilation was maintained with mechanical ventilation on a mixture of room air and titrated isoflurane. The isoflurane concentration needed was between 1% and 2% to maintain an acceptable level of anesthesia during the experiment. A single anesthetic agent, isoflurane, was used in an attempt to avoid potential physiologic confounders associated with many other agents (e.g., endogenous epinephrine release and hypertension with ketamine or myocardial depression with barbiturates or propofol) (11, 12). Ventilator settings were adjusted to maintain end-tidal carbon dioxide at 40 ± 4 mm Hg.

Micromanometer-tipped catheters (5F, MPC-500, Millar Instruments, Houston, TX) were surgically introduced and positioned in the right atrium, left ventricle, and aorta. A pacing catheter was placed temporarily into the right ventricle to induce VF. Correct catheter placement was verified by fluoroscopy. Electrode position and adhesion were verified before each defibrillation attempt.

Measurements

Electrocardiograms and aortic, right atrial, and left ventricular pressures were recorded continuously (P3P Ponemah Physiology Platform, LDS Test and Measurement, Middleton, WI). Tau, the time constant of ventricular relaxation and a quantitative measure of diastolic performance, was calculated. Left ventriculograms were obtained by injection of radio-opaque dye into the left ventricle, and the fluoroscopic movies were recorded in normal sinus rhythm at baseline and at 1, 2, 3, and 4 hrs postresuscitation. The ventriculograms were digitally converted to allow computerized calculation of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), determined over two to six consecutive sinus rhythm beats (13).

We measured cardiac troponin levels at baseline and 4 hrs after induction of VF. Due to test availability, we assayed troponin T in the first series of piglets and troponin I in the subsequent series. We used a commercially available, quantitative immunologic measurement of cardiac troponin. Using either assay we sought to identify animals with markedly elevated troponin levels qualitatively indicative of massive myocardial damage. Cardiac troponin T (Cardiac reader, Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) concentrations ≥0.1 ng/mL were considered positive, and very high concentrations >0.4 ng/mL were considered as indicative of massive myocardial damage (14–16). Similarly, cardiac troponin I concentrations >0.4 ng/mL were considered positive and very high concentrations >5 ng/mL as indicative of massive mycardial damage (17, 18).

Voltage and current waveforms for each shock were recorded by a digital oscilloscope (TDS5054, Tektronix, Beaverton, OR) connected to a custom-built voltage and current sensor for subsequent determination of defibrillation waveform characteristics and transthoracic impedance. Pre- and postshock electrocardiographic waveforms were recorded (Lifepak 12 defibrillator/monitor and Code-Stat Suite medical informatics system, Physio-Control, Redmond, WA) for later evaluation. Termination of VF was determined at 10 secs after the shock.

Experimental Protocol

After baseline data collection, VF was induced with 100 Hz alternating current delivered in the right ventricle and confirmed by the electrocardiographic waveform and precipitous decline in aortic pressure. Mechanical ventilation was discontinued and the endotracheal tube was left in place. After 7 mins of untreated VF, defibrillation was attempted with one to three shocks of adult or pediatric dose, as determined by randomization. If VF persisted, or if aortic pressure was < 50 mm Hg, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) was provided for 90 secs, followed by a brief (<10 secs) pause for rhythm assessment. Manual chest compressions were provided at a metronome-guided rate of 100 compressions per minute and mechanical ventilation at 12 breaths/min with 100% oxygen. CPR intervals of 1 min were alternated with rhythm assessment and single shocks until ROSC or until 27 mins after VF induction. ROSC was defined as an aortic peak systolic pressure of ≥50mm Hg and a pulse pressure of ≥20 mm Hg for >1 min. Epinephrine (0.02 mg/kg) was administered intravenously if ROSC was not attained by 20 mins after VF induction, mimicking a typical time interval until drug delivery for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (19–22). Repeat epinephrine doses were provided at 3-min intervals during continued CPR. For persistent VF, defibrillation was attempted with single shocks 90 secs after each epinephrine bolus. If ROSC was achieved, anesthesia was resumed and the animals were monitored for a 4-hr intensive care period. Surviving animals were recovered from anesthesia and placed in observation pens for the next 20 hrs.

Treatment Groups

All defibrillation waveforms delivered, whether adult or pediatric dose, were biphasic truncated exponential shocks (Lifepak 12 defibrillator/monitor with ADAPTIV biphasic technology). The adult-dose experimental group (n = 26) received shocks set to deliver 200, 300, and 360 J. Standard adult-sized pads with a conductive area of 111 cm2 were used. For the pediatric-dose group (n = 26), the same defibrillator was set to deliver the same energy dosage through attenuating pediatric electrodes (Infant/Child Reduced Energy Defibrillation Electrodes, Physio-Control), which reduced the delivered energy to ~50, 75, and 86 J. These defibrillation pads have a conductive area of 52 cm2.

Neurologic Evaluation

Two observers evaluated neurologic function 24 hrs postresuscitation using a previously described swine Cerebral Performance Category score of global neurologic function (6). The Cerebral Performance Category evaluation is widely employed in animal model CPR research and is an adaptation for swine of the University Pittsburgh Canine Cerebral Performance Categories (23–25). The Cerebral Performance Category uses a 5-point scale to assess neurologic function. Category 1 was assigned to piglets that appeared normal on the basis of level of consciousness, gait, feeding behavior, response to an approaching human, and response to human restraint. Category 2, mildly abnormal, was assigned when the piglets had subtle dysfunction with regard to these characteristics. Category 3, severely disabled, referred to more severe dysfunction, such as inability to stand, walk, or eat. Category 4, vegetative state or deep coma, referred to piglets with minimal response to noxious stimuli. Category 5 referred to animals with no response to their environment. Categories 1 and 2 were considered good neurologic outcome. After the 24-hr evaluation, survivors were euthanized.

Data Analysis

Comparisons of continuous variables between the two experimental treatment groups were evaluated by unpaired Student’s t-test and described as mean ± SD, unless otherwise noted. Longitudinal data (e.g., LVEF) were analyzed using a repeated-measures analysis of variance (26) and a generalized estimating equation. Briefly, the generalized estimating equation approach is appropriate for analyzing data collected in groups (animals) where observations within a group may be correlated but observations in separate groups (adult-dose vs. pediatric-dose shocks) may be assumed to be independent (27). Comparisons of discrete variables were evaluated with Fisher’s exact test. Statistical analyses were performed with Statview 5.0 and GraphPad Instat 3.0 software.

RESULTS

We studied 52 total piglets in two treatment groups that did not differ at baseline in regard to weight, blood gases, temperature, or hemodynamic variables (Table 1). All animals were normothermic.

Table 1.

Data at baseline and 1 and 4 hours postresuscitation

| Baseline | 1 Hour Postresuscitation | 4 Hours Postresuscitation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pediatric | Adult | Pediatric | Adult | Pediatric | Adult | |

| n | 26 | 26 | 21 | 23 | 21 | 23 |

| Weight | 19.2 ± 3.9 | 18.8 ± 3.3 | ||||

| Temperature | 36.7 ± 1 | 37.1 ± 1.2 | 35.9 ± 1.4 | 36.6 ± 1.5 | 35.6 ± 2.0 | 36.0 ± 1.9 |

| Heart rate | 115 ± 20 | 117 ± 14 | 122 ± 18 | 146 ± 26 | 100 ± 17 | 117 ± 23 |

| AoS | 73 ± 10 | 70 ±9 | 66 ±6 | 71 ±9 | 67 ±8 | 68 ± 12 |

| AoD | 49 ±8 | 46 ±8 | 45 ±4 | 48 ±6 | 44 ±6 | 44 ± 8 |

| Ao mean | 61 ±9 | 57 ± 10 | 55 ±5 | 58 ±9 | 55 ±7 | 56 ± 12 |

| RAP | 8 ±3 | 7±3 | 11 ±4 | 11 ±5 | 9±3 | 11 ± 5 |

| LVEDP | 10 ±4 | 10 ±4 | 12 ±5 | 13 ±6 | 11 ±6 | 13 ± 6 |

| Tau | 35 ± 14 | 37 ±7 | 48a ± 16 | 47a ± 16 | 49a ± 21 | 49a ± 17 |

| pHa | 7.44 ± 0.05 | 7.46 ± 0.03 | — | — | — | — |

| PaO2 | 84 ± 18 | 95 ± 75 | — | — | — | — |

Mean ± SD.

p=.03 from baseline.

Ao, aorta; AoS, aortic systolic pressure; AoD, aortic diastolic pressure; RAP, right atrial pressure; LVEDP, left ventricular end-diastolic pressure; pHa, arterial pH.

Pediatric refers to pediatric-dose shocks, adult refers to adult-dose shocks.

Shock Characteristics

By design, the mean highest energy delivered was much lower for pediatric shocks (74 ± 12 J) than adult shocks (261 ± 65 J) (p < .001). Similarly, the mean largest delivered peak current was much lower with pediatric shocks (13 ± 2 A) than adult shocks (37 ± 8 A) (p < .001). As expected, transthoracic impedance was inversely related to pad size and shock intensity; therefore, the mean impedance measured for pediatric shocks (68 ± 8 Ω) was higher than for adult shocks (41 ± 7 Ω) (p < .0001) (Table 2). The cumulative energy delivered was 430 ± 471 J in the pediatric-dose group and 930 ± 1528 J in the adult-dose animals (p = 0.18). Despite weights ranging from 12 to 26 kg, there was no difference in mean weight for the piglets in which the first pediatric dose shock succeeded in terminating VF compared with those that required more than one shock (18.4 ± 3.7 kg, n = 8 vs. 19.6 ± 4.0 kg, n = 18).

Table 2.

Shock characteristics

| Pediatric | Adult | |

|---|---|---|

| Largest peak current delivered (A) | 13 ± 2a | 37 ± 8 |

| Largest energy delivered (J) | 74 ± 12a | 261 ± 65 |

| Median (interquartile range) | 79 (73, 81) | 218 (202, 308) |

| Impedance (Ω) | 68 ±8 | 41 ± 7 |

| Mean total shocks delivered | 6.4 ± 7.2b | 3.1 ± 4.3 |

| Cumulative delivered energy (J) | 430 ± 471 | 930 ± 1528 |

Mean ± SD

differs from adult p< .0001

differs from adult p= .05.

Pediatric refers to pediatric-dose shocks, adult refers to adult-dose shocks.

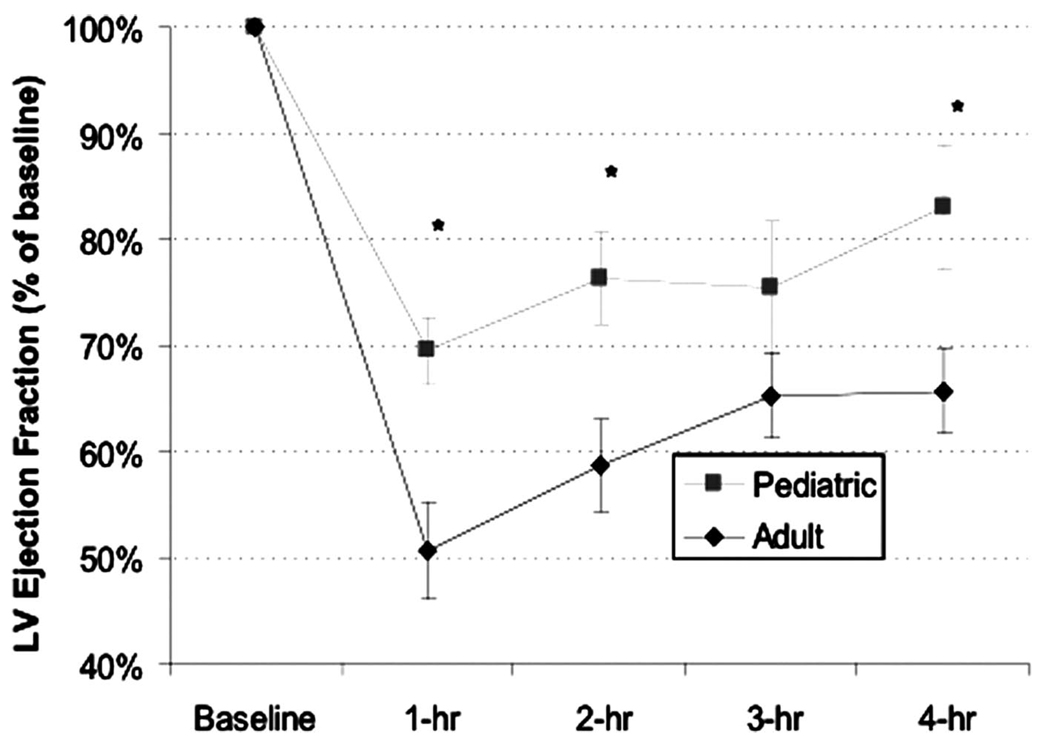

Postresuscitation Myocardial Function

Postresuscitation myocardial function data are displayed in Figure 1. We found more pronounced left ventricular myocardial dysfunction after adult-dose defibrillation. The LVEF at 1 hr postresuscitation decreased relative to baseline in both groups, and the decrease in LVEF was significantly greater after adult-dose than pediatric-dose defibrillation (p < .05). This effect persisted throughout the 4-hr monitoring period. Tau (Table 1) rose from base-line to 1 hr postresuscitation in both groups (p = .03).

Figure 1.

Postresuscitation myocardial function data. LV, left ventricular.

Resuscitation and Defibrillation Efficacy

Return of spontaneous circulation occurred in 22 of 26 pediatric-dose piglets and 23 of 26 adult-dose animals. Twenty-four-hour survival after shocks occurred in 17 of 26 pediatric-dose animals vs. 14 of 26 in the adult-dose group (p not significant). Survival to 24 hrs with good neurologic outcome (i.e., cerebral performance category score 1, normal or 2, mild disability) was 14/26 for the group receiving pediatric shocks and 9/26 in the group receiving adult shocks (p not significant).

The pediatric dose was less effective than the adult dose at initial termination of VF with the first shock (eight of 26 vs. 19 of 26, p = .005). However, both doses were quite effective at terminating VF within the first two shocks: 19 of 26 in the pediatric-dose group vs. 23 of 26 in the adult-dose group (p not significant). Shock-refractory VF occurred in two piglets, one in each group. Total duration of CPR in the pediatric-dose vs. adult-dose animals (4.7 ± 5.9 vs. 3.0 ± 3.0 mins) and time elapsed before ROSC (11.7 ± 5.9 vs. 10.0 ± 3.0 mins) were not different between the two groups.

Myocardial Injury: Cardiac Troponin

All swine tested at baseline had normal cardiac troponin levels. For the piglets surviving to 4 hrs that were assayed, only 20% (four of 20) of the animals receiving a pediatric-dose shock had positive troponin (i.e., abnormally high as defined in the methods) vs. 58% (11 of 19) in the adult-dose group (p = .02). Two animals that were defibrillated with adult-dose shocks had very high levels of troponin I consistent with massive damage (18.6 and 40.1 ng/mL), and these levels remained very high for 24 hrs. Both received a large number of shocks (seven and 11), but they were not the only animals to receive that many shocks. None of the piglets treated with pediatric-dose shocks had very high troponin I levels; the highest troponin level after pediatric-dose shocks was 0.98 ng/mL.

DISCUSSION

After we substantially extended the sample size, these data confirm that defibrillation of piglets with adult-dose shocks resulted in worse postresuscitation left ventricular function and a greater frequency of myocardial damage than defibrillation with pediatric doses. The piglets treated with the adult dose exhibited a greater reduction in LVEF and were more likely to have elevated cardiac troponin postresuscitation. Although postresuscitation myocardial dysfunction is a major cause of postresuscitation mortality in humans, and we observed a difference in postresuscitation myocardial function between groups, this did not translate to a difference between groups in 24-hr outcome (28, 29).

The piglets in the adult-dose group received higher energy shocks, delivered through larger electrodes, than the piglets in the pediatric-dose group. Consequently, they were successfully defibrillated with fewer shocks but were exposed to about three times the peak current. However, some of the current may not have gone through the heart because of the larger adult electrodes causing decreased current density (i.e., more current would probably traverse the thorax without traversing the heart because the pads were larger than the piglets’ hearts). Since the two groups did not differ in duration of untreated VF, duration of CPR, or time to ROSC, at least one component of their more pronounced postresuscitation decrease in myocardial function was presumably mediated by the high peak current delivery.

Postresuscitation Myocardial Dysfunction

Clinical and animal studies have established that postresuscitation myocardial dysfunction is common and is a significant cause of intensive care unit morbidity and mortality after initially successful resuscitation from cardiac arrest (28, 29). It is a classic myocardial stunning phenomenon with biventricular systolic and diastolic dysfunction, resolving after 1 or 2 days (13, 29–34). This postarrest myocardial stunning is pathophysiologically similar to sepsis-related myocardial dysfunction (35, 36), including increased production of inflammatory mediators, such as elevated tumor necrosis factor.

Various factors contribute to postresuscitation myocardial dysfunction; longer periods of untreated VF, more prolonged duration of CPR, and defibrillation with overly large shocks are known to result in more pronounced dysfunction (1, 33, 37), but their relative contributions to myocardial dysfunction in pediatric or adult patients have not been well established.

Several animal studies have examined the effect of defibrillation dose on cardiac injury and dysfunction in immature animals (i.e., pediatric models). In neonatal piglets weighing <5 kg receiving sequential individual monophasic shocks of 20–40 J/kg, Gaba and Talner (38) established that substantial myocardial damage occurred only with cumulative doses >150 J/kg. Killingsworth and colleagues (39) found only brief transient changes in myocardial function, resolving within 60 secs, when biphasic shocks up to 360 J (as much as 100 J/kg) were delivered to piglets after brief periods of VF. In contrast to the data from these two studies using short intervals of VF, when shocks were delivered after 7 mins of untreated VF in our study, we found a difference in both myocardial dysfunction and myocardial damage between groups with maximum doses averaging 4 and 15 J/kg. Because we observed dysfunction at lower doses than did those previous studies, and because the dysfunction varied with dosage, postresuscitation myocardial dysfunction was presumably a function of both the dose and the prolonged VF.

Postresuscitation myocardial damage with elevated cardiac enzymes and poor ventricular function is well documented after pediatric cardiac arrests (34), although it is impossible to know how much of this to attribute to defibrillation shocks. There are few clinical data addressing myocardial injury and dysfunction in children treated with adult-dose defibrillation shocks. One case report documented a 3-yr-old child who had no elevations of creatine kinase or cardiac troponin I and echocardiographically normal postresuscitation ventricular function after receiving a biphasic shock of 150 J (9 J/kg) (40).

Shock Efficacy

The recommendation for pediatric defibrillation with monophasic shocks is 2–4 J/kg and is based on animal studies of short-duration VF and a single retrospective study of in-hospital (short duration) VF with 91% (52 of 57) defibrillation success (41). We recently evaluated the efficacy of 2-J/kg monophasic shocks in victims of cardiac arrest <13 yrs old, finding that failure of that dose to terminate prolonged out-of-hospital VF was more common than in the previously reported in-hospital data (seven of 14 vs. five of 57 failures, p = .001) (42). This greater difficulty terminating VF in the out-of-hospital setting is consistent with the findings in our piglet studies that model prolonged out-of-hospital VF (6, 8).

Biphasic shocks have been shown, in multiple settings, to be more effective at terminating VF than monophasic shocks (43–45). This study and previous studies have demonstrated that biphasic shocks of 50–86 J (2–15 J/kg) are safe and effective for the treatment of prolonged VF in a pediatric swine model (6, 9, 10). We have further shown that these shocks result in better outcomes than monophasic weight-based doses of 2–4 J/kg (6, 9, 10). Perhaps these biphasic pediatric shocks will improve prehospital defibrillation rates in children compared with historical monophasic shock data.

In the present study, we delivered a first biphasic shock dose averaging 2.7 J/kg in the pediatric-dose group and 11.1 J/kg in the adult-dose group. Although the first shock success of the adult dose was higher than the pediatric dose, both doses were quite effective at terminating prolonged VF within the first two shocks.

Two recent articles reported on treatment of infants and children with pediatric-capable AEDs. In one case report of an infant with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, VF was terminated at home after ~70 secs with a 50-J (8-J/kg) shock from a biphasic AED. Postarrest echocardiograms revealed “transient mild depression of ventricular function,” and the infant survived without apparent sequelae (46). In a case series of 27 children and young adults connected to pediatric AEDs, eight patients (age 4.5 months to 10 yrs) were shocked, receiving a mean of 1.9 shocks; all eight survived to hospital admission and five of eight survived to discharge (7). No evidence was presented to assess the potential shock-induced damage. Clearly, pediatric-capable AEDs can save lives.

The Right Pediatric Dose

Both large defibrillation doses and prolonged VF can increase postresuscitation dysfunction. Currently, defibrillation from an adult-only AED is likely to be available to the child in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest before pediatric-dose defibrillation. When only an adult-dose defibrillator is immediately available for a child in VF, the risk of inducing postresuscitation myocardial dysfunction from an excessive defibrillation dose must be weighed against the risk of delaying defibrillation for a pediatric-capable AED. Moreover, any delay to defibrillation increases the risk of neurologic injury in surviving patients. Our observation of increased myocardial dysfunction but the same outcome for adult-dose shocks suggests that prompt defibrillation with an adult dose is preferable to delayed defibrillation with a pediatric dose.

Limitations

Although this experiment was not blinded, piglets were randomly assigned to a defibrillation dose, and the resuscitation and postresuscitation protocols were standardized and strictly followed. Because postresuscitation myocardial function was the primary outcome measure, we did not provide postresuscitation hemodynamic support. It is possible that aggressive postresuscitation care could have improved the 24-hr survival and neurologic outcome in both study groups.

The piglets were evaluated at 24 hrs, but myocardial damage and function were not evaluated after 4 hrs. It is possible that in some cases, the damage and dysfunction observed postresuscitation were transient and did not directly affect the outcome (e.g., of the eight 24-hr surviving adult-dose piglets with elevated troponin at 4 hrs, five achieved a good neurologic outcome).

CONCLUSIONS

Both pediatric and adult doses effectively terminated VF in this piglet model of out-of-hospital VF, but the pediatric doses resulted in fewer cases of myocardial damage and less postresuscitation myocardial dysfunction. Our findings suggest that the use of adult rather than pediatric defibrillation doses may increase the risk of transient myocardial dysfunction in children, yet the outcomes evaluated were comparable between the two groups. These animal data support the use of both new pediatric-capable AEDs and adult biphasic AEDs to defibrillate children. Although the optimal pediatric defibrillation dose remains unknown and should be further investigated, pediatric defibrillation at any dose offers a chance of survival, whereas failure to shock provides none.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge Sacha Cueto and Nancy Coleman for their administrative assistance.

Supported, in part, by Medtronic Physio-Control, Redmond, WA.

Drs. Banville, Chapman, and Walker are employed by Medtronic and hold Medtronic stock and stock options. Dr. Kern is a consultant for Medtronic Emergency Response Systems. Dr. Robert Berg has received a grant from Medtronic Emergency Response Systems. The remaining authors have not disclosed any potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

For information regarding this article, E-mail: marcb@peds.arizona.edu

REFERENCES

- 1.Part 12: Pediatric Advanced Life Support. Circulation. 2005;112 24 Suppl:IV167–IV187. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lopez-Herce J, Garcia C, Dominguez P, et al. Characteristics and outcome of cardiorespiratory arrest in children. Resuscitation. 2004;63:311–320. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nadkarni VM, Larkin GL, Peberdy MA, et al. First documented rhythm and clinical outcome from in-hospital cardiac arrest among children and adults. JAMA. 2006;295:50–57. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reis AG, Nadkarni V, Perondi MB, et al. A prospective investigation into the epidemiology of in-hospital pediatric cardiopulmonary resuscitation using the international Utstein reporting style. Pediatrics. 2002;109:200–209. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.2.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Part 5: Electrical therapies: Automated external defibrillators, defibrillation, cardioversion, and pacing. Circulation. 2005;112 24 Suppl:IV35–IV46. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.970954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berg RA, Chapman FW, Berg MD, et al. Attenuated adult biphasic shocks compared with weight-based monophasic shocks in a swine model of prolonged pediatric ventricular fibrillation. Resuscitation. 2004;61:189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2003.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atkins DL, Jorgenson DB. Attenuated pediatric electrode pads for automated external defibrillator use in children. Resuscitation. 2005;66:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2004.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berg RA, Samson RA, Berg MD, et al. Better outcome after pediatric defibrillation dosage than adult dosage in a swine model of pediatric ventricular fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:786–789. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark CB, Zhang Y, Davies LR, et al. Pediatric transthoracic defibrillation: Biphasic vs. monophasic waveforms in an experimental model. Resuscitation. 2001;51:159–163. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(01)00398-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang W, Weil MH, Jorgenson D, et al. Fixed-energy biphasic waveform defibrillation in a pediatric model of cardiac arrest and resuscitation. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:2736–2741. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200212000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jasani MS, Salzman SK, Tice LL, et al. Anesthetic regimen effects on a pediatric porcine model of asphyxial arrest. Resuscitation. 1997;35:69–75. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(96)01094-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wenzel V, Padosch SA, Voelckel WG, et al. Survey of effects of anesthesia protocols on hemodynamic variables in porcine cardiopulmonary resuscitation laboratory models before induction of cardiac arrest. Comp Med. 2000;50:644–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kern KB, Hilwig RW, Rhee KH, et al. Myocardial dysfunction after resuscitation from cardiac arrest: An example of global myocardial stunning. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;28:232–240. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(96)00130-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goktekin O, Melek M, Gorenek B, et al. Cardiac troponin T and cardiac enzymes after external transthoracic cardioversion of ventricular arrhythmias in patients with coronary artery disease. Chest. 2002;122:2050–2054. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.6.2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lai CS, Hostler D, D’Cruz BJ, et al. Prevalence of troponin-T elevation during out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:754–756. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.11.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Landesberg G, Vesselov Y, Einav S, et al. Myocardial ischemia, cardiac troponin, and long-term survival of high-cardiac risk critically ill intensive care unit patients. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:1281–1287. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000166607.22550.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng YJ, Chen C, Fallon JT, et al. Comparison of cardiac troponin I, creatine kinase-MB, and myoglobin for detection of acute ischemic myocardial injury in a swine model. Am J Clin Pathol. 1998;110:70–77. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/110.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vikenes K, Westby J, Matre K, et al. Release of cardiac troponin I after temporally graded acute coronary ischaemia with electrocardiographic ST depression. Int J Cardiol. 2002;85:243–251. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(02)00162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kudenchuk PJ, Cobb LA, Copass MK, et al. Amiodarone for resuscitation after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest due to ventricular fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:871–878. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909163411203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown CG, Martin DR, Pepe PE, et al. A comparison of standard-dose and high-dose epinephrine in cardiac arrest outside the hospital. The Multicenter High-Dose Epinephrine Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1051–1055. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199210083271503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stiell I, Hebert P, Weitzman B, et al. High-dose epinephrine in adult cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1045–1050. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199210083271502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Callaham M, Madsen C, Barton C, et al. A randomized clinical trial of high-dose epinephrine and norepinephrine vs standard-dose epinephrine in prehospital cardiac arrest. JAMA. 1992;268:2667–2672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vaagenes P, Cantadore R, Safar P, et al. Amelioration of brain damage by lidoflazine after prolonged ventricular fibrillation cardiac arrest in dogs. Crit Care Med. 1984;12:846–855. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198410000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bircher N, Safar P. Cerebral preservation during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Crit Care Med. 1985;13:185–190. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198503000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berg R, Kern K, Sanders A, et al. Bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation: Is ventilation necessary? Circulation. 1993;88:1907–1915. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.4.1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sherrill D, Enright P, Kaltenborn W, et al. Predictors of longitudinal change in diffusing capacity over 8 years. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:1883–1887. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.6.9812072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diggle P, Heagerty P, Liang K, et al. Analysis of Longitudinal Data. Second Edition. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mullner M, Domanovits H, Sterz F, et al. Measurement of myocardial contractility following successful resuscitation: Quantitated left ventricular systolic function utilising non-invasive wall stress analysis. Resuscitation. 1998;39:51–59. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(98)00122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laurent I, Monchi M, Chiche J, et al. Reversible myocardial dysfunction in survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:2110–2116. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02594-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruiz-Bailen M, Aguayo de Hoyos E, Ruiz-Navarro S, et al. Reversible myocardial dysfunction after cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2005;66:175–181. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kern K, Hilwig R, Berg R, et al. Postresuscitation left ventricular systolic and diastolic dysfunction: Treatment with dobutamine. Circulation. 1997;95:2610–2613. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.12.2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tang W, Weil M, Sun S, et al. The effects of biphasic and conventional monophasic defibrillation on postresuscitation myocardial function. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:815–822. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00270-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Checchia P, Sehra R, Moynihan J, et al. Myocardial injury in children following resuscitation after cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2003;57:131–137. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(03)00003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meyer R, Kern K, Berg R, et al. Post-resuscitation right ventricular dysfunction: Delineation and treatment with dobutamine. Resuscitation. 2002;55:187–191. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(02)00204-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adrie C, Adib-Conquy M, Laurent I, et al. Successful cardiopulmonary resuscitation after cardiac arrest as a “sepsis-like” syndrome. Circulation. 2002;106:562–568. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000023891.80661.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Niemann J, Garner D, Lewis R. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha is associated with early postresuscitation myocardial dysfunction. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1753–1758. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000132899.15242.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xie J, Weil M, Sun S, et al. High-energy defibrillation increases the severity of postresuscitation myocardial dysfunction. Circulation. 1997;96:683–688. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.2.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gaba D, Talner N. Myocardial damage following transthoracic direct current counter-shock in newborn piglets. Pediatr Cardiol. 1982;2:281–288. doi: 10.1007/BF02426974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Killingsworth C, Melnick S, Chapman F, e, et al. Defibrillation threshold and cardiac responses using an external biphasic defibrillator with pediatric and adult adhesive patches in pediatric-sized piglets. Resuscitation. 2002;55:177–185. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(02)00157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gurnett C, Atkins D. Successful use of a biphasic waveform automated external defibrillator in a high-risk child. Am J Cardiol. 2000;86:1051–1053. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01151-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gutgesell H, Tacker W, Geddes L, et al. Energy dose for ventricular defibrillation of children. Pediatrics. 1976;58:898–901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berg M, Samson R, Meyer R, et al. Pediatric defibrillation doses often fail to terminate prolonged out-of-hospital ventricular fibrillation in children. Resuscitation. 2005;67:63–67. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2005.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bardy G, Ivey T, Allen M, et al. A prospective randomized evaluation of biphasic vs. monophasic waveform pulses on defibrillation efficacy in humans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989;14:728–733. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90118-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schneider T, Martens P, Paschen H, et al. Multicenter, randomized, controlled trial of 150-J biphasic shocks compared with 200- to 360-J monophasic shocks in the resuscitation of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest victims. Optimized Response to Cardiac Arrest (ORCA) Investigators. Circulation. 2000;102:1780–1787. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.15.1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Higgins S, O’Grady S, Banville I, et al. Efficacy of lower-energy biphasic shocks for transthoracic defibrillation: A follow-up clinical study. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2004;8:262–267. doi: 10.1016/j.prehos.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bar-Cohen Y, Walsh E, Love B, et al. First appropriate use of automated external defibrillator in an infant. Resuscitation. 2005;67:135–137. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]