Abstract

In order to identify new metabolic abnormalities in patients with complex neurodegenerative disorders of unknown aetiology, we performed high resolution in vitro proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy on patient cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples. We identified five adult patients, including two sisters, with significantly elevated free sialic acid in the CSF compared to both the cohort of patients with diseases of unknown aetiology (n = 144; P < 0.001) and a control group of patients with well-defined diseases (n = 91; P < 0.001). All five patients displayed cerebellar ataxia, with peripheral neuropathy and cognitive decline or noteworthy behavioural changes. Cerebral MRI showed mild to moderate cerebellar atrophy (5/5) as well as white matter abnormalities in the cerebellum including the peridentate region (4/5), and at the periventricular level (3/5). Two-dimensional gel analyses revealed significant hyposialylation of transferrin in CSF of all patients compared to age-matched controls (P < 0.001)—a finding not present in the CSF of patients with Salla disease, the most common free sialic acid storage disorder. Free sialic acid content was normal in patients’ urine and cultured fibroblasts as were plasma glycosylation patterns of transferrin. Analysis of the ganglioside profile in peripheral nerve biopsies of two out of five patients was also normal. Sequencing of four candidate genes in the free sialic acid biosynthetic pathway did not reveal any mutation. We therefore identified a new free sialic acid syndrome in which cerebellar ataxia is the leading symptom. The term CAFSA is suggested (cerebellar ataxia with free sialic acid).

Keywords: cerebellar ataxia, free sialic acid, cerebrospinal fluid, neurometabolic disorder, nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy

Introduction

In vitro Nuclear Magnetic Resonance spectroscopy (NMRS) is a validated biochemical tool for metabolic analyses of human body fluids and diagnosis of inborn errors of metabolism in children and adults. The technique is of special interest because it requires minimal sample preparation, it can simultaneously detect compounds of different nature and it offers structural information on the metabolites present in body fluids. In the last decade, in vitro NMRS contributed to the identification of new inborn errors of metabolism, some of which are amenable to therapeutic intervention (Moolenaar et al., 2003; Engelke et al., 2004, 2008; Oostendorp et al., 2006). A number of neurological metabolic disorders are defined by elevation of key metabolites in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). We hypothesized that NMRS could allow the identification of small metabolites in the CSF of patients with complex neurodegenerative disorders for which extensive metabolic and genetic work-up was negative. As a result, we identified a new metabolic entity named CAFSA (cerebellar ataxia with free sialic acid), which extends the range of human diseases involving free sialic acid metabolism.

Materials and Methods

Children and adults from three referral centres for neurogenetics and neurometabolism were enrolled in clinical protocols approved by the local ethics committees of the Assistance Publique des Hôpitaux de Paris, France, the National Institutes of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Bethesda, MD, USA and the Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center, the Netherlands. Written informed consent was obtained for all patients or their legal guardians.

Patients’ cohorts

Two hundred thirty five patients with progressive and complex neurological diseases were included in the study, with ages at examination ranging from 1 to 80 years. Patients with disorders of unknown aetiology (n = 144) were classified according to the leading neurological symptom: psychomotor retardation (n = 17), cerebellar ataxia (n = 25), spastic paraplegia (n = 9), parkinsonism or other extrapyramidal manifestations (n = 31), neuropathy (n = 7), psychiatric symptoms (n = 13) and leukodystrophy (n = 42). The disease control group consisted of 91 patients with similar clinical presentation but well-defined clinical diagnoses that can be classified as (i) hypomyelinating diseases: Salla disease, Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease, CACH/Vanishing White Matter disease, hypomyelination hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and hypodontia syndrome (4H syndrome); (ii) demyelinating diseases: Alexander disease, Krabbe disease, L-2-hydroxy glutaric aciduria, adult polyglucosan body disease, leukoencephalopathy with brain stem and spinal cord involvement and lactate elevation (LBSL), X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy, megalencephalic leukoencephalopathy with subcortical cysts, adult autosomal dominant leukodystrophy with Lamin B1 duplication, cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis; (iii) genetic diseases that can affect the white matter: Wilson disease, respiratory chain defects (mutations in nuclear and mitochondrial genes), Fabry disease, tetrahydrobiopterin deficiency, type 3 Gaucher (chronic neuronopathic) disease, Niemann-Pick type C disease, spastic paraplegia 11 and 15, chromosomal abnormalities (Turner syndrome, 18q ter deletion); (iv) genetic diseases that affect the basal ganglia: neuroacanthocytosis, Fahr disease, Aicardi-Goutières syndrome; (v) genetic diseases that affect the cerebellum: spinocerebellar ataxia 17, ataxia with oculomotor apraxia type 1; (vi) acquired diseases affecting the white matter: multiple sclerosis, corticobasal degeneration and antiphospholipid syndrome; (vii) patients with progressive conditions such as Alzheimer disease, frontotemporal dementia, neurosarcoidosis and (viii) patients with non-neurodegenerative neurological condition such as normal pressure hydrocephalus, stroke, Korsakoff syndrome, fish odour syndrome.

A wide panel of metabolic and genetic investigations was performed in the cohort of 144 patients and showed no abnormality (Supplementary methods).

Proton NMRS of body fluids

In order to identify new metabolic abnormalities, CSF was stored at −80°C waiting for serial proton NMRS analyses. In case of abnormal findings in CSF, urine and plasma samples were also obtained from patients and stored at −80°C. CSF, urine and plasma samples were prepared for NMRS with minimal handling (Supplementary methods) (Engelke et al., 2004; Mochel et al., 2007).

Investigation of sialic acid metabolism

Following significant findings by NMRS in the CSF of five patients, further investigations were conducted. In addition to NMRS, urinary free and bound sialic acid levels were determined by a quantitative colorimetric assay as previously described (Romppanen and Mononen, 1995). Free and total sialic acid levels were also measured in cultured skin fibroblasts (Kleta et al., 2003).

All exons and their surrounding intron/exon boundaries of four candidate genes of the sialic acid biosynthetic pathway were PCR amplified from genomic DNA and analysed by bi-directional direct sequencing: the SLC17A5 gene (GenBank NM_012434), Neu5Ac pyruvate lyase (NPL, GenBank NM_030769), CMP-Neu5Ac synthase (CMAS, GenBank NM_018686), as well as exon 5 of GNE (GenBank NM_005476), coding for the allosteric site of UPD-GlcNAc 2-epimerase. Total RNA was also isolated from confluent fibroblast cultures with and without cycloheximide treatment (Supplementary methods) and converted into two overlapping SLC17A5 cDNA fragments for subsequent bi-directional sequencing (Supplementary methods).

Proteomics studies of CSF

We performed two-dimensional gel electrophoresis, as well as MS and MS/MS for protein and glycoform identification in patients’ CSF (Supplementary methods). The volume and intensity of spots of interest were determined and automated calculation of a ratio of asialotransferrin to total transferrin was obtained as previously described (Vanderver et al., 2005, 2008). 2-DG analysis and ratio calculation were performed by an investigator (B.K) blinded to the values of free sialic acid in CSF.

Gangliosides analyses

Due to the presence of a peripheral neuropathy, two out of five patients have had a sural nerve biopsy, which was studied by routine light and electron microscopy. Analysis of the ganglioside patterns were performed on peripheral nerve tissue stored at −80°C as described in a previous study (Timmons et al., 2006).

Statistical analysis

To compare the ratio of asialotransferrin to total transferrin between the different patient groups, an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed with age as a covariate. The Bonferroni method was used to adjust the P-values associated with the multiple comparisons between the age-adjusted means.

Results

Isolated elevation of free sialic acid in the CSF of five patients

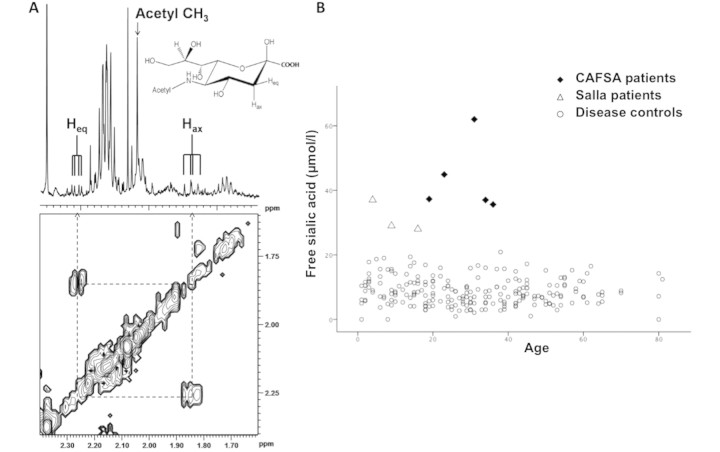

Among the cohort of 144 patients with complex neurological disorders of unknown aetiology, high resolution in vitro proton NMRS of CSF revealed an increased concentration of free sialic acid in five patients, from four families. The one-dimensional proton NMR spectrum of free sialic acid, also called N-acetylneuraminic acid (Neu5Ac), is characterized by the presence of a main peak at 2.05 ppm, corresponding to the methyl group of free sialic acid, associated with smaller peaks around 1.85 and 2.26 ppm corresponding to the pyranose ring protons of the carbon-3 atom (Fig. 1A). The two-dimensional proton NMR spectrum confirms that these smaller peaks are coupled and therefore belong to the same molecule of free sialic acid (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Identification of elevated free sialic acid by NMR spectroscopy (NMRS) in the CSF of five patients. (A) One-dimensional 1H (upper) and two-dimensional 1H–1H COSY (lower) 500 MHz spectrum of the CSF of CAFSA Patient 2. The cross peaks of the H3eq (equatorial) and H3ax (axial) protons in Neu5Ac are connected by dashed lines. The structure represents the beta-anomer of N-acetylneuraminic acid (=free sialic acid or Neu5Ac). (B) Values of free Neu5Ac in the CSF of the 235 patients cohort, including CAFSA and Salla patients. The elevation of free sialic acid is even greater in the CAFSA patients than in the Salla patients. Note that higher free Neu5Ac levels can be observed in the first 4–6 months of life (data not shown).

The mean value of free sialic acid in the CSF of the CAFSA patients was 43.4 ± 11.0 μmol/l, ranging from 35.6 to 67 μmol/l (Fig. 1B), and was highly significantly increased compared to the cohort of patients with diseases of unknown aetiology (8.2 ± 4.2 μmol/l, P < 0.001) as well as to the control cohort of patients with well-defined diseases (9.9 ± 5.6 μmol/l, P < 0.001) (Fig. 1B). The mean values in the two cohorts are similar to those found in a previous study where free sialic acid was measured by high performance liquid chromatography in a small group of normal controls (Hayakawa et al., 1993). As expected, patients with Salla disease (n = 3), a well-known disease involving free sialic acid [OMIM 604369; (Verheijen et al., 1999)], had elevation of free sialic acid in CSF as well although to a lesser degree (31.3 ± 4.9 μmol/l) (Fig. 1B).

Brain tumours and pyogenic meningitis, two reported conditions leading to elevation of free sialic acid in CSF, were ruled out. In the case of our five patients, the elevation of free sialic acid was restricted to their CSF. Free sialic acid was indeed normal in urine and plasma, unlike Salla patients who usually have a marked elevation of free sialic acid in their urine. Free and total sialic acid was also normal in patients’ cultured skin fibroblasts. Sequencing of all exons, as well as exon–intron junctions, of SLC17A5, mutated in patients with free Sialic Acid Storage Diseases (SASD) (Verheijen et al., 1999), did not reveal any mutation. RT-PCR did not display any abnormal splicing variants, even when cycloheximide was added to the cultured media in order to inhibit non-sense mediated decay. Sequencing of exon 5 of GNE, encoding the allosteric site of UDP-GlcNAc 2-epimerase/ManNAc kinase, mutated in sialuria patients (Seppala et al., 1999), as well as the coding regions of Neu5Ac pyruvate lyase (NPL, Neu5Ac aldolase) (Wu et al., 2005), and CMP-Neu5Ac synthase (CMAS) (Lawrence et al., 2001), did not reveal any mutation either.

Clinical characteristics of five patients with isolated elevation of free sialic acid in CSF

Two out of the five patients (Patients 1 and 2) were siblings but with no reported consanguinity. All patients presented with progressive cerebellar ataxia that started during early adulthood except in patient 5 (Table 1). Cognitive and/or noticeable behavioural decline started concomitantly (Table 1). A peripheral neuropathy was also found in all patients on clinical and/or electrophysiological examination (Table 1). Three patients manifested non-neurological symptoms such as bifascicular block, QT interval increase and glomerulosclerosis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristic of five CAFSA patients. Patients 1 and 2 are siblings

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | Female | Male | Male | Female |

| Age of onset (ataxia) (years) | 24 | 20 | 22 | 20 | 10 |

| Age at examination (years) | 34 | 37 | 23 | 35 | 19 |

| Family history | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Cerebellar gait ataxia | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Cerebellar dysarthria | ++ | + | + | + | ++ |

| Eye movements | Slow saccades | Slow saccades | Normal | Slow saccades | Slow saccades |

| Tendon reflexes UL | +2 | +1 | +4 | +2 | 0 |

| Tendon reflexes LL | +1 | 0 | +1 | +2 | 0 |

| Plantar reflexes | Flexor | Flexor | Flexor | Flexor | Extensor |

| Peripheral nerve electrophysiology | Sensory axonal neuropathy | ND | Motor axonal neuropathy | Motor axonal neuropathy | Sensory and motor demyelinating neuropathy |

| Conduction velocities; Amplitudes (normal values) | Ulnar Sensory; amplitude | ND | Peroneal Motor | Peroneal Motor | Peroneal Motor |

| 5.7 μV (>8 μV) | 45 m/s (>42 m/s); 0.4 mV | 32 m/s (>45 m/s); | 21 m/s (>40 m/s); | ||

| (>3 mV) | 0.5 mV (>3.4 mV) | 2.1 mV (>2.4 mV) | |||

| Cognition/Behavioral decline | Frontal syndrome (attention deficit) | Paranoid episodes | Marked mental slowness | Frequent anger outbursts | Low range IQ (88), attention deficit |

| Other | Dystonia/Epilepsy | _ | _ | Ptosis/external ophthalmoplegia | _ |

| Hearing loss | _ | _ | +++ | +++ | + |

| Vision loss | _ | _ | _ | Mixed retinal dystrophy | _ |

| Non-neurological | _ | _ | Growth retardation | Bifascicular block | Growth retardation |

| Features | Cataract | Long QT interval | |||

| Glomerulosclerosis |

UL = upper limbs; LL = lower limbs; + (mild), ++ (moderate), +++ (severe); – (not present).

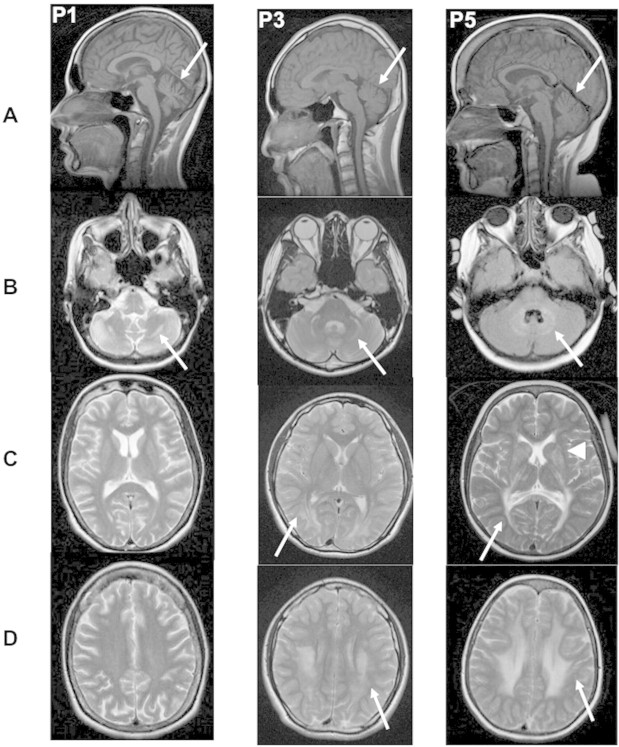

Brain MRI revealed a mild to moderate vermian atrophy in all patients (Fig. 2A). White matter abnormalities were observed in the cerebellum (n = 4), particularly in the hilus of the dentate nucleus and peridentate white matter (Fig. 2B), and in the brainstem (n = 2). White matter signal abnormality was also seen at the supratentorial level, involving the periventricular white matter and sparing the juxtacortical U fibres (n = 3) (Fig. 2C and D). This abnormality extended to the pyramidal tracts in the thalamus and to the basal ganglia in two patients (Fig. 2C). Note that, apart from mild vermian atrophy, one of the two affected sisters presented with almost normal brain imaging.

Figure 2.

Brain MRI of CAFSA Patients 1, 3 and 5. For each patient, (A) T1-weighted mid-sagittal view (arrow points to cerebellar atrophy); B–D: axial T2-weighted images at the level of the posterior fossa (B) basal ganglia (C) and centrum semi ovale (D). Arrows point to white matter abnormalities, and arrowhead to the involvement of the basal ganglia in Patient 5.

Due to the complex neurological presentation, a muscle biopsy was performed in three patients (Patients 1, 4 and 5 from Table 1) with immunohistochemistry and enzymatic studies that showed no abnormality. Sequencing of genes commonly involved in cerebellar ataxia (SCA 1-2-3-6-7-14-17, FRDA, AO1, AO2, DRPLA, mitochondrial DNA) was negative in all five patients. In addition, Patient 4 had no mutation in the POLG1 gene (Milone et al., 2008).

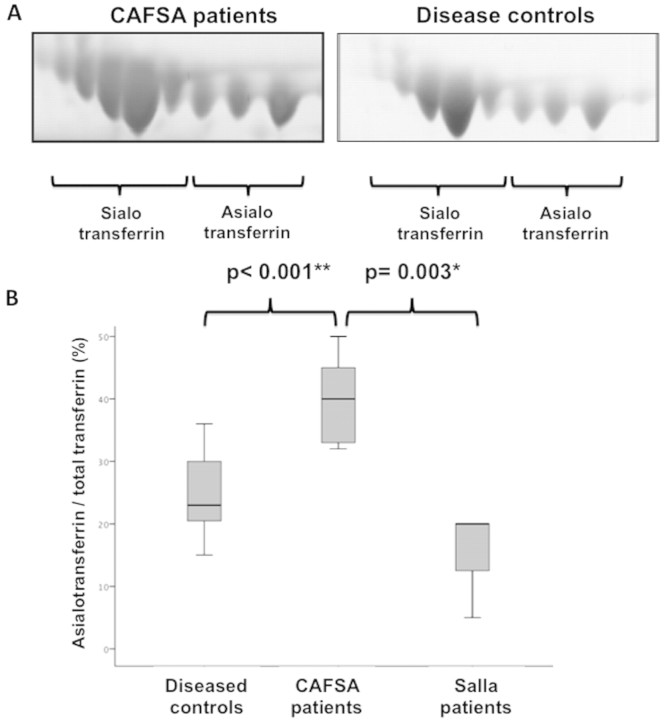

Hyposialylation of CSF transferrin of the five CAFSA patients

In order to determine whether the elevation of CSF free sialic acid could reflect functional changes in the metabolism of free sialic acid, we studied the patterns of sialylation of an abundant CSF protein, transferrin. Proteomic studies were performed on the five CAFSA patients, as well as on 15 age-matched disease controls from the cohort previously described. All CAFSA patients displayed elevated total protein in the CSF (range 54–1.72 mg/dl). Using two-dimensional gel electrophoresis followed by protein and glycoforms analysis using MS and MS/MS, a difference in the neuraminic acid isoforms of one of the most abundant CSF proteins, transferrin, was identified (Fig. 3A). When compared to age-matched disease controls and Salla patients, affected patients had a greater ratio of asialotransferrin (not containing sialic acid) to total transferrin (40 ± 7.7 versus 24.9 ± 6.4 and 15 ± 8.7) (Fig. 3B). The asialotransferrin/total transferrin ratio in CAFSA patients was significantly elevated compared to this ratio in disease controls (P < 0.001) and also compared to Salla disease patients (P = 0.003). There was no significant difference between disease controls and Salla patients.

Figure 3.

Proteomic studies in the CSF of CAFSA patients. (A) Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis of CSF transferrin with identification of sialic acid-containing isoforms versus nonsialic acid-containing isoforms confirmed in all patient groups by MALDI-TOF TOF as previously described (Vanderver et al., 2005). (B) Ratio of asialotransferrin to total transferrin showing a significant difference between CAFSA patients (n = 5) and disease controls (n = 15), as well as between CAFSA and Salla patients (n = 3).

Investigation of peripheral nerve in two patients

Light and electronic microscopy of the sural nerve biopsy of Patient 3 showed mild loss of large myelinated fibres and hypomyelination of small and regenerating fibres. No other abnormality was seen (data not shown). Similar findings were seen in the nerve biopsy of Patient 5 with the addition of marked polylobulation of Schwann cell nuclei (data not shown).

Oligosaccharides are key components of nerve gangliosides, and require the transfer of free sialic acid molecules by sialyltransferases. Therefore, we analysed the profile of nerve gangliosides in order to better characterize the biochemical defects in CAFSA patients. Ganglioside profiles studied in peripheral nerve biopsies of Patients 3 and 5 did not reveal any qualitative abnormality compared to control nerves. No abnormality was either detected in a patient with Salla disease. In all cases, 3′LM1 was the major ganglioside entity, and the proportion of major di- and trisialosialogangliosides was unchanged (Supplementary figure). The total concentration of gangliosides could not be measured accurately due to the small size of the biopsies, but appeared normal from visual inspection of the chromatograms.

Discussion

We describe a novel neurometabolic entity involving free sialic acid in five patients with cerebellar ataxia as the leading symptom, named CAFSA (cerebellar ataxia with free sialic acid). The five patients had an elevation of free sialic acid in CSF but not in urine, plasma or in cultured skin fibroblasts. This new entity emphasizes the original contribution of NMRS of CSF in the investigation of neurological disorders of unknown aetiology. Increased asialotransferrin relative to total transferrin was also found in the CSF of all CAFSA patients, suggesting that the sialylation of key central nervous system proteins is altered. This prompted us to investigate gangliosides in the peripheral nerve but we found no evidence of abnormal sialylation of sphingolipids in this tissue.

In addition to cerebellar ataxia, all patients had peripheral neuropathy and cognitive decline or important behavioural changes. A mild to moderate cerebellar atrophy restricted to the vermis was observed in all CAFSA patients, often associated with supra- and infratentorial white matter abnormalities, especially around the dentate nucleus. The peridentate white matter hyperintense signal on T2-weighted images is similar to the one seen in cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis where it is due to the accumulation of cholestanol (Sedel et al., 2008) and in some mitochondrial diseases. These diseases could be considered as differential diagnoses. Three out of the four patients tested presented with axonal peripheral neuropathy. Confounding factors such as post kidney-transplant type 2 diabetes and multiple medications may have modified the neuropathy of Patient 5. Yet, the pathological findings on the sural nerve biopsy of Patient 5 were similar to those of Patient 3.

Based on this combination of clinical and imaging characteristics we prospectively identified a sixth patient suspected of having CAFSA. A 44-year-old male was diagnosed with deafness as a child and developed cerebellar ataxia at the age of 40 years, together with cognitive decline. His brain MRI was quite similar to the pattern described in the CAFSA patients, i.e. moderate cerebellar atrophy and white matter abnormalities both at the periventricular level and in the region of the dentate nucleus. NMRS confirmed a marked elevation of free sialic acid in his CSF (66 μmol/l). Despite unifying clinical characteristics, the intrafamilial and extrafamilial phenotypic heterogeneity observed in the CAFSA patients is compatible with either genetic homogeneity with variable expression or genetic heterogeneity. The occurrence of the disease in two siblings with unaffected parents suggests an autosomal recessive transmission.

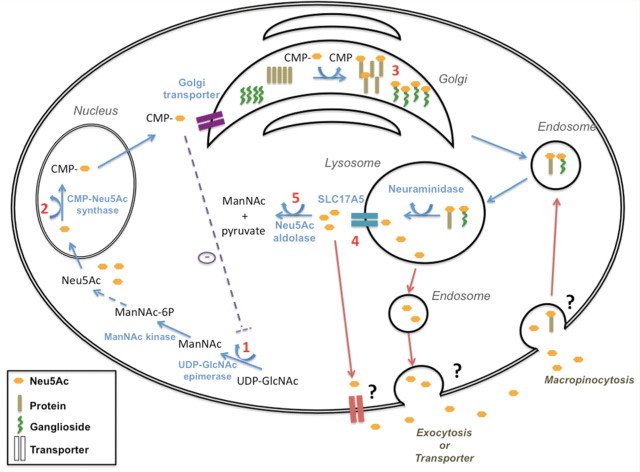

The first two committed steps of cytoplasmic free Neu5Ac synthesis is mediated by the bifunctional enzyme UDP-GlcNAc 2-epimerase/ManNAc kinase (encoded by the GNE gene). The epimerase enzymatic domain converts UDP-GlcNAc to N-acetylmannosamine (ManNAc) and the kinase domain subsequently phosphorylates ManNAc to ManNAc-6-P. The epimerase domain is feed-back inhibited by CMP-sialic acid in its allosteric site (encoded by exon 5 of GNE, Fig. 4, Step 1) (Hinderlich et al., 1997; Seppala et al., 1999). ManNAc-6-P is sequentially further converted to Neu5Ac. Neu5Ac is then translocated to the nucleus, where it is activated to CMP-Neu5Ac, by the CMAS (Fig. 4, Step 2). After exiting the nucleus, CMP-Neu5Ac can either cytoplasmically inhibit UDP-GlcNAc 2-epimerase activity, or be transported into the Golgi where various sialyltransferases utilize CMP-Neu5Ac to sialylate oligosaccharides that participate in the synthesis of glycoproteins and gangliosides (Fig. 4, Step 3) (Varki, 1997; Keppler et al., 1999). For recycling, glycoproteins and gangliosides enter the lysosome, where free Neu5Ac is cleaved from the sialyl-oligosaccharides by neuraminidase and is then exported out of the lysosome by SCL17A5 (Fig. 4, Step 4) (Verheijen et al., 1999). Neu5Ac pyruvate lyase (Neu5Ac aldolase) finally catalyzes the cleavage of Neu5Ac into pyruvate and ManNAc (Fig. 4, Step 5). It has recently been suggested that Neu5Ac can also be taken up from an exogenous source through macropinocytosis and incorporated into different subcellular fractions (Fig. 4) (Bardor et al., 2005). Free sialic acid levels can be measured in human body fluids such as urine, plasma or CSF. Urinary excretion of free sialic acid is increased in two disorders associated so far with sialic acid metabolism (Strehle, 2003), the SASD—due to mutations in SLC17A5, and sialuria—caused by mutations in the allosteric site of GNE (Seppala et al., 1999). To appear in urine or serum, free sialic has to exit the cell, but such mechanisms have not been described. The cellular exit of free sialic acid could involve exocytosis or a membrane transporter (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Free sialic acid metabolism and transport. See the Discussion for details. Numbers 1–5 designate the metabolic steps that we investigated in the five CAFSA patients, with steps 1, 2, 4 and 5 indicating the four candidate genes sequenced in the free sialic acid biosynthetic pathway that did not reveal any mutation.

In order to identify possible aetiologies of CAFSA syndrome, we investigated several metabolic and genetic aspects of free sialic acid metabolism. The association of increased cerebrospinal sialic acid and hyposialylation of CSF proteins has never been described, especially in the context of absence of intracellular accumulation of free sialic acid. Hereditary inclusion body myopathy (HIBM) is due to mutations in the GNE gene resulting in reduced activity of both the UDP-GlcNAc 2-epimerase and the ManNAc kinase enzymes. HIBM is associated with hyposialylation of α-dystroglycan, an integral component of the dystrophin–glycoprotein complex, in HIBM muscle (Huizing et al., 2004; Saito et al., 2004) but normal sialylation profile in serum (Savelkoul et al., 2006). Likewise, we hypothesized that our patients may display mutations in one or more genes of the free sialic acid pathway, possibly resulting in hyposialylation of brain proteins, such as transferrin. We therefore excluded mutations in the SLC17A5 gene of the five patients, at the genomic and mRNA levels. No mutations in exon 5 of GNE, and in the coding regions of the genes for CMP-Neu5Ac synthase and Neu5Ac pyruvate lyase were found (Fig. 4). Since the free sialic acid elevation appears to be restricted to the CSF, there may exist unreported—exclusively neuronal expressed—alternative transcripts of some of these genes. Table 2 shows the comparison of the main features of CAFSA with the known free sialic disorders.

Table 2.

Main features of CAFSA compared with known free sialic acid disorders

| CAFSA | Salla disease (Aula and Gahl, 2001) | ISSD (Lemyre et al., 1999) | Sialuria (Aula and Gahl, 2001) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at onset | 10–24 years | Infancy to Childhood | 1st year of life | Infancy |

| Horizontal nystagmus | No | Common | Yes | No |

| Cerebellar ataxia | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Pyramidal syndrome | No | Yes | ND | No |

| Cognitive abnormalities | Cognitive or behavioural decline | Psychomotor retardation | Psychomotor retardation (severe) | Psychomotor retardation (mild) |

| Peripheral neuropathy | Axonal > demyelinating | 50% (demyelinating) | ND | ND |

| Dysmorphism | No | Mild | Yes | Yes |

| Growth retardation | Possible | Yes | Yes | No |

| Signs of organ storage | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Cerebral MRI | ||||

| Cerebellar atrophy | Mild to moderate | Moderate to severe | Severe | No |

| Thin corpus callosum | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| White matter abnormality | Hilus of dentate nucleus, peridentate white matter and periventricular | Diffuse hypomyelination | Diffuse hypomyelination | No |

| Free sialic acid elevation | ||||

| Urine | No | Common*(+) | Yes (++) | Yes (+++) |

| CSF | Yes | Yes | ND | ND |

| Fibroblasts | No | Yes (lysosomal) | Yes (lysosomal) | Yes (cytoplasmic) |

*Salla patients have been reported without sialuria (Mochel et al., Ann Neurol, in press). ISSD = Infantile free sialic storage disease; ND = not determined; + = mild; ++ = moderate; +++ = massive.

Our results may also suggest that, instead of intracellular, there may be an abnormal trafficking of free sialic acid between the intracellular and the extracellular compartments. The marked elevation of this sugar in the CSF, even above the levels seen in Salla disease, a disorder with intracellular accumulation of free sialic acid, gives some support to this hypothesis. Other research approaches, such as the analysis of bio-orthogonal reactions to monitor the transport and metabolism of sialylated biomolecules in patients’ cell lines (Yarema and Bertozzi, 2001; Prescher and Bertozzi, 2005) may be required to further elucidate this new neurological disorder of free sialic acid metabolism.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Brain online.

Funding

Assistance Publique des Hôpitaux de Paris (CRC 05169); Intramural Program of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Human Genome Research Institute; National Institute of Health; Baylor Research Foundation. Integrated Molecular Core for Rehabilitation Medicine (NIH IDDRC P30HD40677, NIH NCMRR/NINDS 5R24 HD050846).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Drs Odile Dubourg, Maria Tsokos, Mones Abu-Asab and Kondi Wong for the pathological analysis of the patients’ sural nerve, Dr Roseline Froissart and Nathan H. McNeill for their contribution in SLC17A5 sequencing and Dr Jerry N. Thompson for the measurements of free sialic acid in patients’ urine. The authors are also grateful to Nadège Boildieu, Hakima Manseur and Sylvie Forlani for their assistance with patients’ samples.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- CAFSA

cerebellar ataxia with free sialic acid

- CMAS

CMP-Neu5Ac synthase

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- HIBM

hereditary inclusion body myopathy

- Neu5Ac

N-acetylneuraminic acid

- NMRS

nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- NPL

Neu5Ac pyruvate lyase

- SASD

free sialic acid storage diseases

References

- Aula P, Gahl WA. Disorders of free sialic acid storage. In: Valle D, Beaudet AL, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW, Antonarakis SE, Balabio A, editors. The online metabolic & molecular bases of inherited disease. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001. pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bardor M, Nguyen DH, Diaz S, Varki A. Mechanism of uptake and incorporation of the non-human sialic acid N-glycolylneuraminic acid into human cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4228–37. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412040200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelke UF, Liebrand-van Sambeek ML, de Jong JG, Leroy JG, Morava E, Smeitink JA, et al. N-acetylated metabolites in urine: proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopic study on patients with inborn errors of metabolism. Clin Chem. 2004;50:58–66. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.020214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelke UF, Sass JO, Van Coster RN, Gerlo E, Olbrich H, Krywawych S, et al. NMR spectroscopy of aminoacylase 1 deficiency, a novel inborn error of metabolism. NMR Biomed. 2008;21:138–47. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa K, De Felice C, Watanabe T, Tanaka T, Iinuma K, Nihei K, et al. Determination of free N-acetylneuraminic acid in human body fluids by high-performance liquid chromatography with fluorimetric detection. J Chromatogr. 1993;620:25–31. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(93)80047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinderlich S, Stasche R, Zeitler R, Reutter W. A bifunctional enzyme catalyzes the first two steps in N-acetylneuraminic acid biosynthesis of rat liver. Purification and characterization of UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerase/N-acetylmannosamine kinase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:24313–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.39.24313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huizing M, Rakocevic G, Sparks SE, Mamali I, Shatunov A, Goldfarb L, et al. Hypoglycosylation of alpha-dystroglycan in patients with hereditary IBM due to GNE mutations. Mol Genet Metab. 2004;81:196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keppler OT, Hinderlich S, Langner J, Schwartz-Albiez R, Reutter W, Pawlita M. UDP-GlcNAc 2-epimerase: a regulator of cell surface sialylation. Science. 1999;284:1372–6. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleta R, Aughton DJ, Rivkin MJ, Huizing M, Strovel E, Anikster Y, et al. Biochemical and molecular analyses of infantile free sialic acid storage disease in North American children. Am J Med Genet A. 2003;120A:28–33. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence SM, Huddleston KA, Tomiya N, Nguyen N, Lee YC, Vann WF, et al. Cloning and expression of human sialic acid pathway genes to generate CMP-sialic acids in insect cells. Glycoconj J. 2001;18:205–13. doi: 10.1023/a:1012452705349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemyre E, Russo P, Melancon SB, Gagne R, Potier M, Lambert M. Clinical spectrum of infantile free sialic acid storage disease. Am J Med Genet. 1999;82:385–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milone M, Brunetti-Pierri N, Tang LY, Kumar N, Mezei MM, Josephs K, et al. Sensory ataxic neuropathy with ophthalmoparesis caused by POLG mutations. Neuromuscul Disord. 2008;18:626–32. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochel F, Barritault J, Boldieu N, Eugene M, Sedel F, Durr A, et al. Contribution of in vitro NMR spectroscopy to metabolic and neurodegenerative disorders. Rev Neurol. 2007;163:960–5. doi: 10.1016/s0035-3787(07)92640-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moolenaar SH, Engelke UF, Wevers RA. Proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy of body fluids in the field of inborn errors of metabolism. Ann Clin Biochem. 2003;40:16–24. doi: 10.1258/000456303321016132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oostendorp M, Engelke UF, Willemsen MA, Wevers RA. Diagnosing inborn errors of lipid metabolism with proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Clin Chem. 2006;52:1395–405. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.069112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescher JA, Bertozzi CR. Chemistry in living systems. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:13–21. doi: 10.1038/nchembio0605-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romppanen J, Mononen I. Age-related reference values for urinary excretion of sialic acid and deoxysialic acid: application to diagnosis of storage disorders of free sialic acid. Clin Chem. 1995;41:544–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito F, Tomimitsu H, Arai K, Nakai S, Kanda T, Shimizu T, et al. A Japanese patient with distal myopathy with rimmed vacuoles: missense mutations in the epimerase domain of the UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerase/N-acetylmannosamine kinase (GNE) gene accompanied by hyposialylation of skeletal muscle glycoproteins. Neuromuscul Disord. 2004;14:158–61. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savelkoul PJ, Manoli I, Sparks SE, Ciccone C, Gahl WA, Krasnewich DM, et al. Normal sialylation of serum N-linked and O-GalNAc-linked glycans in hereditary inclusion-body myopathy. Mol Genet Metab. 2006;88:389–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2006.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedel F, Tourbah A, Fontaine B, Lubetzki C, Baumann N, Saudubray JM, et al. Leukoencephalopathies associated with inborn errors of metabolism in adults. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2008;31:295–307. doi: 10.1007/s10545-008-0778-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seppala R, Lehto VP, Gahl WA. Mutations in the human UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerase gene define the disease sialuria and the allosteric site of the enzyme. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64:1563–9. doi: 10.1086/302411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strehle EM. Sialic acid storage disease and related disorders. Genet Test. 2003;7:113–21. doi: 10.1089/109065703322146795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmons M, Tsokos M, Asab MA, Seminara SB, Zirzow GC, Kaneski CR, et al. Peripheral and central hypomyelination with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and hypodontia. Neurology. 2006;67:2066–9. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000247666.28904.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderver A, Hathout Y, Maletkovic J, Gordon ES, Mintz M, Timmons M, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of decreased CSF asialotransferrin for eIF2B-related disorder. Neurology. 2008;70:2226–32. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000313857.54398.0e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderver A, Schiffmann R, Timmons M, Kellersberger KA, Fabris D, Hoffman EP, et al. Decreased asialotransferrin in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with childhood-onset ataxia and central nervous system hypomyelination/vanishing white matter disease. Clin Chem. 2005;51:2031–42. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.055053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varki A. Sialic acids as ligands in recognition phenomena. Faseb J. 1997;11:248–55. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.4.9068613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verheijen FW, Verbeek E, Aula N, Beerens CE, Havelaar AC, Joosse M, et al. A new gene, encoding an anion transporter, is mutated in sialic acid storage diseases. Nat Genet. 1999;23:462–5. doi: 10.1038/70585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M, Gu S, Xu J, Zou X, Zheng H, Jin Z, et al. A novel splice variant of human gene NPL, mainly expressed in human liver, kidney and peripheral blood leukocyte. DNA Seq. 2005;16:137–42. doi: 10.1080/10425170400020373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarema KJ, Bertozzi CR. Characterizing glycosylation pathways. Genome Biol. 2001;2:REVIEWS0004. doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-2-5-reviews0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.