Abstract

Objectives. More than one quarter of HIV-infected people are undiagnosed and therefore unaware of their HIV-positive status. Blacks are disproportionately infected. Although perceived racism influences their attitudes toward HIV prevention, how racism influences their behaviors is unknown. We sought to determine whether perceiving everyday racism and racial segregation influence Black HIV testing behavior.

Methods. This was a clinic-based, multilevel study in a North Carolina city. Eligibility was limited to Blacks (N = 373) seeking sexually transmitted disease diagnosis or screening. We collected survey data, block group characteristics, and lab-confirmed HIV testing behavior. We estimated associations using logistic regression with generalized estimating equations.

Results. More than 90% of the sample perceived racism, which was associated with higher odds of HIV testing (odds ratio = 1.64; 95% confidence interval = 1.07, 2.52), after control for residential segregation, and other covariates. Neither patient satisfaction nor mechanisms for coping with stress explained the association.

Conclusions. Perceiving everyday racism is not inherently detrimental. Perceived racism may improve odds of early detection of HIV infection in this high-risk population. How segregation influences HIV testing behavior warrants further research.

Despite decreases in mortality because of AIDS, the prevalence of HIV infection in the United States remains high overall, and the proportion of diagnoses among Blacks is increasing.1 Although Blacks represent less than 13% of the US population, they account for 42% of prevalent HIV infections and 54% of annual diagnoses.1 An estimated one fourth of all HIV-infected US residents have not been diagnosed.2 HIV-positive Blacks delay seeking care more, progress to AIDS faster, and die from AIDS sooner than do Whites, underscoring the need to improve HIV screening in this population.3,4

Sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinics are an important setting for reaching people at elevated risk of sexual transmission, the primary mode by which infection occurs.5 These clinics provide testing regardless of an individual's ability to pay. The prevalence of undiagnosed HIV infection is higher in STD-clinic populations than in the general population, and people engaging in STD risk behaviors are by definition at risk for HIV transmission. Furthermore, although not every exposure to HIV results in seropositivity, epidemiologic synergy between HIV and classic STDs such as gonorrhea renders STD-infected people more susceptible to HIV infection upon exposure to the virus.6

Population-based surveys suggest that Blacks obtain HIV testing at higher rates than do other racial/ethnic groups7; however, self-reports may overestimate actual testing behavior. In one nationally representative study, 25% of Blacks reporting prior HIV tests had assumed they were tested during some clinical visit in which they had neither requested nor consented to a test.8 Among STD-clinic patients, Blacks may actually be less likely to test.9

For Blacks, negative attitudes toward HIV prevention are linked to racism.10 Racism has been defined as “an organized system, rooted in an ideology of inferiority that categorizes, ranks, and differentially allocates societal resources to human population groups.”11(p76) Racism is a multilevel construct fundamentally influenced by macrolevel factors such as residential segregation.12–14 Research suggests that perceiving or experiencing racial discrimination contributes to hypertension,15–17 preterm birth,18 mental health outcomes,19,20 and unhealthful coping behaviors (e.g., cigarette smoking and alcohol use).21 Exactly how individuals respond to perceived racism also is important. In the CARDIA (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults) study, for instance, people who perceived and challenged racism on the job had lower systolic blood pressures (i.e., better outcomes) than did those whom investigators described as internalizing it.16 For some Blacks, however, overachieving in response to racism may adversely affect health, a phenomenon described as “John Henryism.”22

Racism can be thought of as an element in the social environment; perceived racism is the extent to which individuals are aware of that element. Perceived everyday racism reflects individuals' assessments of potentially negative routine interactions (e.g., being followed while shopping in a store) as resulting from racism rather than other causes (e.g., coincidence).23 In some contexts, perceiving racism is detrimental, whereas in others it is self-protective.24

Most racism-related HIV-prevention research examines extreme forms of racism rather than everyday racism. These studies indicate that awareness of the US Public Health Services' study of untreated syphilis among Black men and beliefs that “the government is … using AIDS as a way of killing off minority groups”25 are prevalent and associated with negative attitudes about HIV prevention.26–29 Few studies have examined perceived racism's association with HIV preventive behaviors, and these primarily assess self-reports of behavior. A national phone survey28 of Blacks (N = 500) and a Houston-based survey30 of a multiracial sample (N = 1494) found negative associations between conspiracy beliefs and self-reported condom use for Black men.28,30 One study31 found perceived everyday racism was positively associated with condom use. These studies did not account for residential context.

Perceptions about racism are influenced by interracial interactions. More integrated Blacks perceive more racism.32 Outside the workplace, residential areas are the most likely arenas for interactions; often, however, residential areas are racially segregated. The systematic residential isolation of Blacks from Whites through de facto segregation is a fundamental cause of disparities, differentially influencing access to health care, socioeconomic status, and quality of services.13,33,34 Segregation historically has affected communities in the US South. The most widely assessed dimension of segregation is unevenness. Calculated via the dissimilarity index, D, it indicates an area's relative proportions of minority and majority populations.35

Studies using census geographies, such as block groups, permit monitoring of area socioeconomic and demographic trends across time and place; census designations are well-defined units of analysis, and the socioeconomic data are systematically collected.36 Block groups, which average 1500 residents, are the smallest geographic units for which the US Census Bureau provides sample data.37 Although many studies operationalize neighborhoods as tracts or zip code regions, block groups may be more appropriate units when studying smaller cities or regions in which neighborhood boundaries change rapidly.

The purpose of our study was to examine perceived everyday racism's association with routine HIV testing among at-risk Blacks while accounting for racialized residential contexts.

METHODS

Population and Setting

Data were collected from March to June 2003 in a public STD clinic located in a North Carolina city with high HIV and STD prevalences. Blacks make up 20% of the county's and 28% of the city's population.37 The city's residential segregation (dissimilarity index = 0.54; see appendix available as an online supplement at http://www.ajph.org) exceeds that of 85% of US cities with comparable population size.38 The Black population resides primarily within 2 contiguous zip code regions in which STD and HIV prevalences are highest. Most people who obtain care at the clinic reside in these neighborhoods. As established in extensive formative research,39 access (e.g., transportation) to the clinic was not a barrier to testing in this population. The clinic is the primary source of HIV tests in the county, providing between 3000 and 4000 HIV tests annually.40 Blacks account for more than 60% of the clinic's patients.

Study Design

This was a multilevel, cross-sectional study estimating individual-level associations relative to the behavioral outcome (i.e., visit-specific uptake of routine HIV testing) while accounting for population-averaged residential (i.e., “neighborhood”) characteristics and other factors. The conceptual framework guiding the study integrated Critical Race Theory41 concepts and Andersen's access to care model.42 The University of North Carolina's School of Public Health institutional review board approved all aspects of the study.

Sample

Eligible clinic participants were consecutively enrolled during routine clinic hours. Only outpatients seeking diagnosis or screening for STD or HIV infection were eligible for participation; people seeking follow-up care, information, or other services were not eligible for the study. Inclusion criteria were self-reported race as Black, being 18 years or older, and presenting for diagnosis of or screening for possible STD infection. Of those eligible and invited (N = 474), 61 (41 men, 20 women) declined participation, resulting in an 87% response rate; 413 patients consented to and enrolled in the study. Responses from 38 participants (9%) were excluded from the analyses because data on their visit-specific HIV testing behavior, the outcome of interest, were missing. Two additional observations were excluded because of incomplete questionnaires. The final sample size for individual-level analyses was 373, 56% (n = 210) women. Block group analyses further excluded 61 observations because participant addresses were unreported (e.g., because of homelessness) or impossible to validate using a geographic information system. The final sample size for block group analyses was 312 individuals living within 117 block groups.

Data Collection

Participants completed the 101-item questionnaire while seated in the clinic lobby. To enable privacy and to accommodate possible low levels of literacy, participants listened to an audio-taped version of the questionnaire using headsets and marked responses on a corresponding paper form. The audio-taped recording was completed by a Black research assistant native to the region. Each participant's visit-specific HIV testing behavior was ascertained from the clinic's daily log of diagnostic tests and recorded in a manner blinded to questionnaire data collection. All names were then removed from questionnaires.

Outcome Variable

The outcome was visit-specific uptake of HIV testing via blood draw with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, as recorded in the clinic lab's daily log of administered tests. As standard practice at the clinic, STD patients seeking non–follow-up care were automatically offered an HIV antibody test during their visit. Test uptake was coded yes (1) or no (0). Each time a study participant was seen, lab technicians summarized patient information (name, chart number, and whether HIV testing was performed) in the daily log relevant to HIV antibody test acceptance.

Explanatory Variables and Covariates

Perceived racism and residential segregation were the key explanatory variables. The questionnaire assessed perceived racism,43,44 coping mechanisms for stress, individuals' demographic characteristics, HIV prevention–related constructs (e.g., perceived risk, HIV knowledge), and clinical encounter factors (e.g., previous clinic use). In the pilot study, internal consistency was high (Cronbach's α ≥ 0.70) for the perceived racism,43,44 patient satisfaction,45 HIV knowledge,46 and perceived HIV susceptibility47 scales. Reliability and validity of the perceived racism scale had been established previously for in-person43 and telephone administration.44 We used the 10-item subscale of the perceived racism scale to assess respondents' perceptions about the extent to which Blacks generally encounter several types of White-on-Black perceived racist experiences on the job, in social settings, and in public settings. For instance, “In general, when Blacks shop, they are followed or watched by White security guards or White clerks.” Response options ranged across a 4-point Likert-type scale from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.”

We operationalized residential areas as the Census 2000 block groups in which study respondents resided based on addresses sample members reported in the questionnaires. We obtained data on block group racial composition from census summary file one and assessed segregation using the dissimilarity index (D). This index reflects the proportion of Blacks who must move to achieve racially equal population distributions.35 Block group segregation was derived from each block group's constituent blocks' racial composition and compared across the block groups making up the study area. Index values may range from 0 to 1, with 1 indicating complete segregation.

Covariates included patient satisfaction, a potential confounder. Based on focus groups, we derived a 5-item, ordinal scale from Marshall and Hays' 18-item questionnaire.45 Each response was scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale (strongly agree to strongly disagree). Stress coping mechanisms were assessed via responses to the statement “How often do you cope with stress by … ” Responses were categorized as passive (e.g., sleeping), healthful (e.g., exercising), or negative (e.g., drinking). Standard HIV prevention–related constructs such as perceived HIV risk were assessed using measures borrowed from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.47,48

Additional variables reflecting neighborhood deprivation or inequity were derived from census summary files 1 and 3. These included relative income (ratio of block group median income to median income for the region), concentrated poverty (40% or greater poverty within a block group),49 percentage of Black residents (proportion of block group population that was Black alone or in combination with some other race relative to the block group total population), percentage of vacant households, percentage unemployed, mean educational attainment, and percentage of female-headed households.

Statistical Analyses

We used nonautomatic, backward elimination to specify multivariable logistic regression models50 with generalized estimating equations (GEE) to account for variance clustering that occurs when one level of data (e.g., individual) is nested within another (e.g., block group). GEE is preferred to other multilevel approaches (e.g., mixed models) when, as in this study, the group-level units are not a random sample of some universe of block groups.51 We specified an exchangeable correlation structure (i.e., any 2 responses within a cluster have the same correlation) and used robust variance estimators to derive 95% confidence intervals (CIs) around each estimate. In exploratory analyses, we examined variable distributions, collinearity, interaction, and potential statistical confounding. We also compared estimates obtained using the dissimilarity index to those obtained using percentage Black. Analyses were conducted using Stata version 8 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

Perceived risk of HIV infection was low across age groups and gender categories. Forty-six percent of sample members were seeking care because they had symptoms of an STD; 10% had been referred by another provider.

Table 1 displays sample demographic characteristics and perceived racism scores. Perceived racism scores ranged from the absolute minimum (10), indicating no perceived racism, to the maximum (40), indicating the highest level of perceived racism assessed on the scale. The observed mean scores revealed, on average, agreement with nearly all of the items on the scale. The range, mean, and median scores did not vary by gender.

TABLE 1.

Sample Demographic Characteristics and Perceived Racism Among Patients at a North Carolina Public Health Clinic: March–June 2003

| Gender |

Testing Behavior |

||||

| Men | Women | No Test | Test | Total | |

| Total, no. (%) | 163 (43.7) | 210 (56.3) | 165 (44.2) | 208 (55.8) | 373 (100) |

| Perceived racism score,a Mean (SD) | 28.0 (5.9) | 28.5 (5.8) | 27.4 (5.9) | 28.9 (5.8) | 28.2 (5.9) |

| Age, y | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 28.7 (8.9) | 27.7 (8.9) | 27.63 (8.2) | 28.50 (9.4) | 28.1 (8.9) |

| Range | 18–57 | 18–55 | 18–54 | 18–57 | 18–57 |

| Education, no. (%) | |||||

| Less than high school | 13 (8.2) | 22 (10.6) | 15 (9.2) | 20 (9.9) | 35 (9.5) |

| High school diploma | 68 (42.8) | 87 (41.8) | 68 (41.5) | 87 (42.9) | 155 (42.2) |

| College degree or more | 78 (49.1) | 99 (47.6) | 81 (49.4) | 96 (47.3) | 177 (48.2) |

| Insurance Status, no. (%) | |||||

| Uninsured | 85 (54.5) | 91 (44.2) | 74 (46.0) | 102 (50.8) | 176 (48.6) |

| Medicaid/Medicare | 20 (12.8) | 64 (31.1) | 33 (20.5) | 51 (25.4) | 84 (23.2) |

| Privately insured | 51 (32.70) | 51 (24.8) | 54 (33.5) | 48 (23.9) | 102 (28.2) |

| Employment status, No. (%) | |||||

| Unemployed | 48 (31.4) | 88 (42.7) | 55 (34.4) | 81 (40.7) | 136 (37.9) |

| Part time | 34 (22.2) | 40 (19.4) | 28 (17.5) | 46 (23.1) | 74 (20.6) |

| Full time | 71 (46.4) | 78 (37.9) | 77 (48.1) | 72 (36.2) | 149 (41.5) |

| Income category, no. × $1000 (%) | |||||

| < 5 | 37 (23.9) | 72 (35.8) | 47 (29.6) | 62 (31.5) | 109 (30.6) |

| 5–10 | 20 (12.9) | 43 (21.4) | 24 (15.1) | 39 (19.8) | 63 (17.7) |

| 10–20 | 45 (29.1) | 37 (18 .4) | 40 (25.2) | 42 (21.3) | 82 (23.0) |

| 20–35 | 35 (22.6) | 38 (18.9) | 34 (21.4) | 39 (19.8) | 73 (20.5) |

| > 35 | 18 (11.6) | 11 (5.5) | 14 (8.8) | 15 (7.6) | 29 (8.2) |

The 30-unit scale ranges from 10 to 40, with higher scores indicating higher perceived racism.

Fifty-five percent of participants obtained HIV tests during their clinical visits. Proportionally fewer men than women (χ2 = 6.25; df = 1; P = .01) tested. Relative to younger participants (i.e., age < 30 years), greater proportions of participants 45 years or older tested (54% vs 68%), but this difference was not statistically significant. HIV knowledge and perceived HIV risk were unrelated to testing behavior.

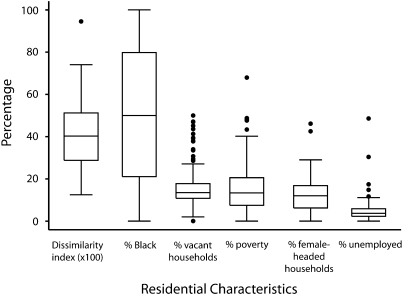

Figure 1 displays summary data on residential characteristics. Spatially, residences clustered around the clinic and loosely followed major roads (data not shown). Between 1 and 14 participants resided in each block group. Block group dissimilarity index scores ranged from 0.13 to 0.94; however, they were heavily clustered around the median, 0.40. Testers resided in more-integrated areas, and nontesters resided in more segregated areas (data not shown).

FIGURE 1.

Boxplots showing distribution of selected Census 2000 residential characteristics (N = 117 block groups): North Carolina.

Note. Horizontal lines within each box indicate medians; each box's lower and upper bounds indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively; the lower and upper whiskers indicate the range of values within 1.5 times the interquartile range; and darkened circles indicate outliers.

The final statistical model is shown in Table 2. The full model included perceived racism, individual demographic characteristics, patient satisfaction, symptoms, ever previously obtaining an HIV test, perceived HIV risk, coping mechanisms, HIV knowledge, and block group characteristics. Perceived racism was associated with higher odds of obtaining routine HIV testing during the clinic visit in crude analyses; this association persisted in the final model (odds ratio [OR] = 1.64; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.07, 2.52). Each 10-unit increase (e.g., from “medium” to “high”) on the 30-unit perceived racism scale corresponded with approximately 60% higher odds of testing. The point estimate for the dissimilarity index (OR = 0.32; 95% CI = 0.05, 2.18) in the final model suggested higher levels of segregation were associated with not testing; however, the 95% CI included the null value. In models replacing the dissimilarity index with percentage Black, the percentage of Blacks in block groups was unassociated with HIV testing (OR = 0.99; 95% CI = 0.99, 1.00).

TABLE 2.

Logistic Regression Generalized Estimating Equations Model Assessing Perceived Racism, Block Group Characteristics, and Testing

| Model 1, OR (95% CI) | Model 2, OR (95% CI) | Model 3, OR (95% CI) | Model 4, OR (95% CI) | Model 5, OR (95% CI) | |

| Perceived racism | 1.68 (1.17, 2.40) | 1.67 (1.14, 2.44) | 1.59 (1.07, 2.38) | 1.72 (1.14, 2.60) | 1.64 (1.07, 2.52) |

| Patient satisfaction | … | … | 1.00 (0.94, 1.06) | 0.99 (0.93, 1.05) | 0.99 (0.93, 1.05) |

| Healthful coping | … | … | … | … | 1.08 (0.91, 1.27) |

| Negative coping | … | … | … | … | 0.96 (0.89, 1.05) |

| Passive coping | … | … | … | 0.88 (0.78, 1.00) | 0.89 (0.78, 1.01) |

| Symptoms (yes or no) | … | … | 0.56 (0.34, 0.93) | 0.58 (0.35, 0.97) | 0.57 (0.34, 0.96) |

| Previous test (yes or no) | … | … | 1.88 (0.97, 3.63) | 1.77 (0.91, 3.45) | 1.78 (0.91, 3.49) |

| Gender (reference = woman) | … | … | 0.46 (0.26, 0.81) | 0.39 (0.22, 0.71) | 0.37 (0.20, 0.69) |

| Block group | … | 0.26 (0.05, 1.28) | 0.34 (0.06, 1.91) | 0.32 (0.05, 1.96) | 0.32 (0.05, 2.18) |

Note. The estimates excluded observations missing data on any variable included in the model. Model 1 was crude; model 2 included perceived racism and block group residential segregation; model 3 excluded stress coping mechanisms; model 4 included passive coping mechanisms; and model 5 included passive, healthful, and negative coping mechanisms.

DISCUSSION

Nearly all participants in this study perceived everyday racism; the more racism was perceived, the higher the odds of being tested for HIV during an STD clinic visit. Neither patient satisfaction nor stress coping mechanisms explained this association. Previous research linking perceived racism to attitudes has suggested it may negatively influence behaviors.52 Our findings did not support that hypothesis. One reason may be that although this study examined everyday racism, most previous research has focused on extreme forms of racism (e.g., HIV conspiracy beliefs). In racially stratified societies, individuals are constantly exposed to everyday racism43; therefore, it is conceivable that there may be contexts in which perceiving it is health protective.

Although the positive association between perceived racism and HIV testing may seem counterintuitive, support for it exists in previous research. Others have found that perceiving racism is not inherently detrimental and that Blacks who notice it in their social environments and challenge it may have healthier outcomes than do those who deny its existence or blame themselves or other minorities for observed disparities.16 The findings also concur with those of the one other study that examined perceived everyday racism and HIV preventive behaviors.31 Investigators using the 38-item racism and life experiences scale (S. P. Harrell, PhD, unpublished scale, 1997) observed that perceived racism was prevalent and positively associated with condom-related HIV preventive behaviors among Black women.

We controlled for coping mechanisms, because how individuals deal with racism they perceive has implications for their well-being.23 Resiliency, which we did not directly measure, may explain positive associations between perceived racism and health-protective behaviors such as HIV testing. According to the resiliency hypothesis, Blacks who perceive racism and develop ways to function day to day in spite of it have higher resiliency levels and cope better with racism-related stressors. An alternative explanation is that social support, also unmeasured in this study, could have confounded the association between perceived racism and testing if people with greater perceived support felt more comfortable both reporting perceived racism and obtaining HIV tests.

Fewer residents of more-segregated block groups got tested. This finding is consistent both with the hypothesis that more-segregated Blacks perceive racism less53 and with the observed association in this study between lower perceived racism and not getting tested. Although segregation often signals Blacks' poor access to care, extensive formative research preceding this study indicated access to the STD clinic was not a barrier.39 Rather, segregation was included because of its conceptual relevance to perceived racism. The small geographic area studied and its predominately Black composition, however, biased any associations around segregation toward the null. These findings contrast with a Los Angeles study in which, regardless of race/ethnicity, people living in “predominately Black” areas were more likely to obtain HIV tests.54 That study operationalized neighborhoods using zip codes rather than the census designations recommended for monitoring population health.55 It also used percentage Black as a proxy measure of segregation, rather than a segregation index as used in our study. Percentage Black may measure unspecified socioeconomic or racial/ethnic factors. Then, too, our research was conducted in the South, where distinctive racial relations persist and racial groups are less heterogeneous than in other parts of the country. The complex relations between segregation, network characteristics such as network-specific HIV prevalences, and behaviors require further research.56–58

That perceived HIV risk was low corroborates other research.59,60 Denial and fear of becoming HIV infected may explain this common finding.61 Primary prevention to promote accurate risk assessments will remain important in the increasingly screening-oriented prevention climate.62

Greater conceptual and empirical clarification of racism constructs is also needed. This study assessed 2 related concepts: perceived racism, an individual level factor, and residential segregation, a macro-level factor. Most research emphasizes interpersonal discrimination rather than structural factors, which may underlie persistent disparities.63

Limitations and Strengths

The study had several limitations. Thirty eight observations were excluded because the participants' testing behaviors were not recorded in the clinic's log. This only occurred if individuals reported a false name to the study or clinic, suggesting distrust or stigma in this population. Sensitivity analyses using single-unit contrasts on the 30-unit perceived racism scale indicated that these missing cases did not substantially distort the findings. Although slightly lower mean perceived racism scores biased the results slightly away from the null, similar point estimates and substantially overlapping CIs were obtained whether these 38 observations were excluded (OR = 1.04; 95% CI = 1.01, 1.09), recoded to “no test” (OR = 1.05; 95% CI = 1.02,1.09), or recoded to “test” (OR = 1.03; 95% CI = 1.00, 1.06). The study did not control for risk behaviors such as injection drug use, which could influence testing behavior.

Although the dissimilarity index is the most widely used measure of residential segregation, it is insensitive to extremely high or low minority population concentrations, may underestimate overall levels of segregation, and does not address geographic considerations captured by other measures (e.g., local area spatial autocorrelations).35,64 The geographic region studied here was small and limited in its racial heterogeneity. Block group estimates, therefore, were biased toward the null.

Lastly, data were sparse (n ≤ 5) in most blockgroups. One strength of GEE is that it accommodates sparse or missing data65; nonetheless, we confirmed the main association by conducting logistic regression analyses that excluded block group–level variables and found basically the same results (OR = 1.64; 95% CI = 1.06, 2.55).

Use of actual, not self-reported, HIV testing reassures us of the validity of this measure of stigmatized behavior. Similarly, our operationalization of residential areas as block groups may better approximate neighborhood patterns in small cities, where neighborhood boundaries may be small or may shift quickly. The public health literature on racism, which primarily targets mental health, chronic disease, and birth-related outcomes, is advanced by this research on an infectious disease–related outcome. Although social context was not empirically confirmed as a risk factor for testing or failure to test, the field is advanced conceptually by the inclusion of context in the study's design.66

Implications for Practice and Policy

Blacks are not merely victims of racism but also exercise agency within and regarding their social contexts. Those who perceive everyday racism may draw on health-promoting assets relative to their behaviors. We recommend that practitioners work closely with this population to identify transferable, health-protective skills to promote preventive behaviors among other Blacks. Future research can help to clarify the settings, outcomes, and subpopulations in which perceiving racism is detrimental versus constructive.

Fullilove suggested that racism is the “elephant in the room” when providers and educators deliver counseling, testing, and education among this population.67 By showing that perceived racism was not a barrier to HIV prevention, our findings, like Fullilove's argument, challenge assumptions that awareness of racism necessarily inhibits HIV prevention among Blacks. Intervention research is needed to explore whether discussing racism during counseling, testing, or education can reduce distrust and improve communication between Blacks and prevention professionals. For residents of more segregated areas who may be less likely to obtain clinic-based HIV testing, outreach may prove to be effective for reaching this population.

Policies attentive to assets-based interventions, cultural competence, and equity are needed to guide the development and implementation of any prevention strategies (e.g., targeted outreach) that aim to integrate racism-related concerns and prevention efforts.68

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (fellowship 1 F31 AI058914-01), the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (grant T32-HS00032), and the W. K. Kellogg Foundation Kellogg Health Scholars Program (grant P0117943) administered via the Center for the Advancement of Health. The following units at the University of North Carolina also provided support: Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and Development, Department of Social Medicine, Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, Center for AIDS Research (grant P0117943), North Carolina Rural Health Research Program, and Center for the Study of the American South. The authors acknowledge Anissa Vines, Lori Carter-Edwards, and Dionne Godette for their constructive feedback.

Human Participant Protection

The study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of North Carolina's School of Public Health.

References

- 1.Kaiser Family Foundation The HIV/AIDS Epidemic in the United States. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacKellar DA, Valleroy LA, Secura GM, et al. Unrecognized HIV infection, risk behaviors, and perceptions of risk among young men who have sex with men: opportunities for advancing HIV prevention in the third decade of HIV/AIDS. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005:38;603–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cunningham WE, Markson LE, Andersen RM, et al. Prevalence and predictors of highly active antiretroviral therapy use in patients with HIV infection in the United States. HCSUS Consortium. HIV cost and services utilization. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;25:115–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turner BJ, Cunningham WE, Duan N, et al. Delayed medical care after diagnosis in a US national probability sample of persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2614–2622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report: Cases of HIV Infection and AIDS in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2005. Vol. 17 Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fleming DT, Wasserheit JN. From epidemiological synergy to public health policy and practice: the contribution of other sexually transmitted diseases to sexual transmission of HIV infection. Sex Transm Infect. 1999;75:3–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ebrahim SH, Anderson JE, Weidle P, Purcell DW. Race/ethnic disparities in HIV testing and knowledge about treatment for HIV/AIDS: United States, 2001. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2004;18:27–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aragon R, Kates J, Greene L. African Americans' Views of the HIV/AIDS Epidemic at 20 Years. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwarcz SK, Spitters C, Ginsberg MM, Anderson L, Kellogg T, Katz MH. Predictors of human immunodeficiency virus counseling and testing among sexually transmitted disease clinic patients. Sex Transm Dis. 1997;24:347–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dalton HL. AIDS in blackface. Daedalus. 1989;118:205–227 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams DR, Rucker TD. Understanding and addressing racial disparities in health care. Health Care Financ Rev. 2000;21(4):75–90 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones CP. Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener's tale. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1212–1215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep. 2001;116:404–416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gee GC. A multilevel analysis of the relationship between institutional and individual racial discrimination and health status. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:615–623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams DR, Neighbors HW. Racism, discrimination and hypertension: evidence and needed research. Ethn Dis. 2001;11:800–816 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krieger N, Sidney S. Racial discrimination and blood pressure: the CARDIA Study of young black and white adults. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:1370–1378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clark R. Self-reported racism and social support predict blood pressure reactivity in Blacks. Ann Behav Med. 2003;25:127–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dole N, Savitz DA, Hertz-Picciotto I, Siega-Riz AM, McMahon MJ, Buekens P. Maternal stress and preterm birth. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:14–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jackson JS, Brown TN, Williams DR, Torres M, Sellers SL, Brown K. Racism and the physical and mental health status of African Americans: a thirteen year national panel study. Ethn Dis. 1996;6:132–147 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neighbors HW, Jackson JS, Broman CL, Thompson E. Racism and the mental health of African Americans: the role of self and system blame. Ethn Dis. 1996;6:167–175 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kwate NO, Valdimarsdottir HB, Guevarra JS, Bovbjerg DH. Experiences of racist events are associated with negative health consequences for African American women. J Natl Med Assoc. 2003;95:450–460 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.James SA, Hartnett SA, Kalsbeek WD. John Henryism and blood pressure differences among Black men. J Behav Med. 1983;6:259–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McNeilly MD, Anderson NB, Armstead CA, et al. The perceived racism scale: a multidimensional assessment of the experience of white racism among African Americans. Ethn Dis. 1996;6:154–166 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mays VM, Cochran SD, Barnes NW. Race, race-based discrimination, and health outcomes among African Americans. Annu Rev Psychol. 2006;58:201–225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herek GM, Capitanio JP. Conspiracies, contagion, and compassion: trust and public reactions to AIDS. AIDS Educ Prev. 1994;6:365–375 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas SB, Quinn SC. The Tuskegee Syphilis Study, 1932 to 1972: implications for HIV education and AIDS risk education programs in the Black community. Am J Public Health. 1991;81:1498–1504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klonoff EA, Landrine H. Do Blacks believe that HIV/AIDS is a government conspiracy against them? Prev Med. 1999;28:451–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bogart LM, Thorburn S. Are HIV/AIDS conspiracy beliefs a barrier to HIV prevention among African Americans? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;38:213–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Green B, Maisiak R, Wang M, Britt M, Ebeling N. Participation in health education, health promotion, and health research by African Americans: effects of the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment. J Health Educ. 1997;28(4):196–204 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ross MW, Essien EJ, Torres I. Conspiracy beliefs about the origin of HIV/AIDS in four racial/ethnic groups. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41:342–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jipguep M-C, Sanders-Phillips K, Cotton L. Another look at HIV in African American women: the impact of psychosocial and contextual factors. J Black Psychol. 2004;30:366–385 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jackson PB. Health inequalities among minority populations. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005;60(Spec No 2):63–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Acevedo-Garcia D. Residential segregation and the epidemiology of infectious diseases. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51:1143–1161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Massey DS, Denton NA. American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Massey DS, Denton NA. The dimensions of residential segregation. Soc Forces. 1988;67:281–315 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krieger N, Williams DR, Moss NE. Measuring social class in US public health research: concepts, methodologies, and guidelines. Annu Rev Public Health. 1997;18:341–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.US Census Bureau, Geography Division, Cartographic Operations Branch Census Block Groups: Cartographic Boundary Files Descriptions and Metadata, 2002

- 38.US Census. Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2000. Available at: http://factfinder.census.gov. Accessed November 15, 2004.

- 39.Ford CL, Tilson EC, Smurzynski M, Leone PA, Miller WC. Confidentiality concerns, perceived staff rudeness and other HIV testing barriers. Int J Equity Health. 2008;1:7–21 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anonymous HIV Counseling and Testing Sites. Raleigh, NC: Wake County Human Services; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Delgado R, Stefancic J. Critical Race Theory: An Introduction. 1st ed. New York, NY: New York University Press; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36:1–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McNeilly MD, Anderson NB, Robinson EL, et al. Convergent, discriminant, and concurrent validity of the Perceived Racism Scale: a multidimensional assessment of the experience of racism among African Americans. : Jones Reginald L, Handbook of Tests and Measurements for Black Populations; Hampton, VA: Cobb & Henry Publishers;1996:359–373 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vines AI, McNeilly MD, Stevens J, Hertz-Picciotto I, Baird M, Baird DD. Development and reliability of a telephone-administered perceived racism scale (TPRS): a tool for epidemiological use. Ethn Dis. 2001;11:251–262 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marshall GN, Hays RD. The Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire Short-Form (PSQ-18). Santa Monica, CA: RAND; 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rietmeijer CA, Lansky A, Anderson JE, Fichtner RR. Developing standards in behavioral surveillance for HIV/STD prevention. AIDS Educ Prev. 2001;13:268–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Longshore D, Stein JA, Anglin MD. Psychosocial antecedents of needle/syringe disinfection by drug users: a theory-based prospective analysis. AIDS Educ Prev. 1997;9:442–459 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Holtzman D, Bland SD, Lansky A, Mack KA. HIV-related behaviors and perceptions among adults in 25 states: 1997 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1882–1888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Massey DS. The age of extremes: concentrated affluence and poverty in the twenty-first century. Demography. 1996;33:395–412; discussion 413–396 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kleinbaum DG. Logistic Regression: A Self-Learning Text. 1st ed. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liang K-Y, Zeger SL. Regression analysis for correlated data. Annu Rev Public Health. 1993;14:43–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Quinn SC. Belief in AIDS as a form of genocide: implications for HIV prevention programs for African Americans. J Health Educ. 1997;28(suppl 6):S6–S11 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cole ER, R OS. Race, class and the dilemmas of upward mobility for African Americans. J Soc Issues. 2003;59:785–802 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Taylor SL, Leibowitz A, Simon PA, Grusky O. ZIP code correlates of HIV-testing: a multi-level analysis in Los Angeles. AIDS Behav. 2006:579–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Krieger N, Waterman PD, Chen JT, Soobader MJ, Subramanian SV. Monitoring socioeconomic inequalities in sexually transmitted infections, tuberculosis, and violence: geocoding and choice of area-based socioeconomic measures–the public health disparities geocoding project (US). Public Health Rep. 2003;118:240–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Laumann EO, Youm Y. Racial/ethnic group differences in the prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases in the United States: a network explanation. Sex Transm Dis. 1999;26:250–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wallace R, Wallace D. US apartheid and the spread of AIDS to the suburbs: a multi-city analysis of the political economy of spatial epidemic threshold. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41:333–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ. Social context, sexual networks, and racial disparities in rates of sexually transmitted infections. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(suppl 1):S115–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ford CL, Daniel M, Miller WC. High rates of HIV testing despite low perceived HIV risk among African American sexually transmitted disease patients. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98:841–844 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Obermeyer CM, Osborn M. The utilization of testing and counseling for HIV: a review of the social and behavioral evidence. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1762–1774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kowalewski MR, Henson KD, Longshore D. Rethinking perceived risk and health behavior: a critical review of HIV prevention research. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24:313–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thrasher AD, Ford CL, Nearing KA. Cost-effectiveness of screening for HIV. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2137–2139; author reply 2137–2139 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Griffith DM, Mason M, Yonas M, et al. Dismantling institutional racism: theory and action. Am J Community Psychol. 2007;39:381–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Acevedo-Garcia D, Lochner KA, Osypuk TL, Subramanian SV. Future directions in residential segregation and health research: a multilevel approach. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:215–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stokes ME, Davis CS, Koch GG. Generalized estimating equations. Categorical Data Analysis Using the SAS System. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2000:254 [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bond L, Lauby J, Batson H. HIV testing and the role of individual- and structural-level barriers and facilitators. AIDS Care. 2005;17(2):125–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fullilove RE. HIV prevention in the African American community: why isn't anybody talking about the elephant in the room? AIDScience. 2001;1:1–7 [Google Scholar]

- 68.Airhihenbuwa CO. Eliminating health disparities in the African American population: the interface of culture, gender and power. Health Educ Behav. 2006;33:488–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]