Abstract

Objectives. We sought to assess the effectiveness of approaches targeting improved sexually transmitted infection (STI) sexual partner notification through patient referral.

Methods. From January 2002 through December 2004, 600 patients with Neisseria gonorrhoeae or Chlamydia trachomatis were recruited from STI clinics and randomly assigned to either a standard-of-care group or a group that was counseled at the time of diagnosis and given additional follow-up contact. Participants completed an interview at baseline, 1 month, and 6 months and were checked at 6 months for gonorrhea or chlamydial infection via nucleic acid amplification testing of urine.

Results. Program participants were more likely to report sexual partner notification at 1 month (86% control, 92% intervention; adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 1.8; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.02, 3.0) and were more likely to report no unprotected sexual intercourse at 6 months (38% control, 48% intervention; AOR = 1.5; 95% CI = 1.1, 2.1). Gonorrhea or chlamydial infection was detected in 6% of intervention and 11% of control participants at follow-up (AOR = 2.2; 95% CI = 1.1, 4.1), with greatest benefits seen among men (for gender interaction, P = .03).

Conclusions. This patient-based sexual partner notification program can help reduce risks for subsequent STIs among urban, minority patients presenting for care at STI clinics.

Surveillance data document high rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in the United States, with estimates ranging from 15 to 20 million cases per year.1–3 Sexually transmitted infections are an important public health concern given their contribution to reproductive and other health problems.4,5 The estimated health care costs of STIs total $17 billion annually.6 The burden of STIs among Americans of African descent is particularly high.3,7–11

Prevention and control of STIs such as gonorrhea and chlamydia rely to a large degree on timely identification, diagnosis, and treatment of infected individuals.12 Given that a large proportion of persons with gonorrhea or chlamydial infection are asymptomatic,2,13 notification of sexual partners helps increase evaluation of those who may not otherwise be aware of the need to seek medical care. From a broader perspective, sexual partner notification serves to reduce the morbidity of infection within a population and to reduce the duration of infectiousness on an individual level, thereby reducing risks for reinfection.14

Sexual partner notification efforts are generally categorized into 3 approaches. In patient referral, STI patients are asked to notify their sexual partners. In provider referral, a trained health care worker typically employed by a health department elicits identifying information about sexual partners from patients and notifies partners. In conditional or contract referral, a patient is provided with a period of time to notify sexual partners, after which time a health care worker intercedes if the partner is not known to have sought appropriate evaluation and treatment.15

Although reviews suggest that provider referral is the more effective of these approaches in terms of sexual partners presenting for care and infections identified in sexual partners of index patients,14–16 clinical resources are infrequently available for this service and are typically reserved for HIV and syphilis tracing. For gonorrhea and chlamydial infections, patient referral is used in the vast majority of cases.17,18 Despite the reliance on patient referral, there has been inadequate investigation into the effectiveness of this, and other, sexual partner notification methods. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CD C's) Sexually Transmitted Disease Treatment Guidelines note that there is uncertainty regarding the extent to which sexual partner notification effectively decreases the prevalence and incidence of infections.12

It has been estimated that patient referral for gonorrhea and chlamydial infection results in treatment of 29% to 59% of partners,19–24 and some research has demonstrated that enhancements to the patient referral process can increase the likelihood of patient referral and improve the likelihood of identifying and treating sexual partners.25,26 In keeping with the need for more-effective patient referral methods, we developed a clinic-based program designed to promote patient referral among patients with chlamydial infection or gonorrhea and evaluated the program in clinics serving urban, minority patients in geographic areas with high morbidity of infection. We hypothesized that more-effective patient referral would occur when patients were adequately motivated and prepared with the skills to contact sexual partners about their risk for STI and able to effectively influence the health-seeking behaviors of their sexual partners.

METHODS

Respondents

Participant recruitment took place at 2 STI clinics in Brooklyn in New York City that both rely on patient referral for sexual partner notification of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. The first of these was 1 of only 2 non–Department of Health clinics for the evaluation and care of STIs in New York City; the other was a Department of Health STI clinic. More than 24 000 visits occur annually for STI treatment and HIV counseling services at these clinics. Participants were approached sequentially on days of recruitment and were eligible for participation if they had a microbiologically confirmed diagnosis of C trachomatis or N gonorrhoeae and if they met the following criteria: were 18 years or older, able to complete an interview in English or Spanish, reported a diagnosis with either chlamydia or gonorrhea within the previous 2 weeks, sexually active in the 2 months prior to enrollment (to include those patients who would benefit from sexual partner notification activities), and were residing in the New York City area for the evaluation period.

Project interviewers completed a brief screening form with potential participants to assess eligibility. If eligible, the study procedures were described, including randomization procedures, the nature of the control and intervention group participation, methods for maintaining confidentiality of information, and requirements for data collection, including self-report interviews, medical chart abstraction to confirm study eligibility, and analysis of urine samples for gonorrhea or chlamydial infection. Project interviewers read aloud the consent form, and if participants agreed to participate, they were asked to provide written study consent and were given a copy of the consent form. Participants were paid for each of 3 self-report evaluation instruments completed; total compensation across visits for study completion was $70. Participants were not paid to complete health education activities. All program activities, evaluation methods, and methods for maintaining confidentiality were approved by the institutional review boards at participating sites and at the CDC.

Sexually Transmitted Infection Diagnoses

To verify baseline diagnoses, we used information from medical charts to document the confirmation techniques employed for each patient. Enrollees must have had biological evidence of disease as determined by methods used at the sites, which consisted primarily of nucleic acid amplification testing. Nucleic acid amplification testing can be used to analyze for the presence of C trachomatis– or N gonorrhoeae–specific DNA that is amplified. Patients referred on the basis of a presumptive diagnosis but whose tests were subsequently either inconclusive or negative were disenrolled after the baseline visit as per procedures outlined in the informed consent process. Clinic procedures at each site were to provide medications directly to patients at the time of diagnosis for all presumptive diagnoses.

Intervention Activities

Intervention activities were guided by leading behavioral theories, including social cognitive theory27,28 and the theory of reasoned action.29 Constructs addressed in the program included improved skills for sexual partner notification and for reduced sexual risk behavior, improved attitudes for both sexual partner notification and condom use consistency, establishment of sexual partner notification as a socially appropriate and expected response to an STI diagnosis, and increased expectations that engaging in sexual partner notification would benefit the patient, his or her sexual partners, and the public health of the community in general. Partner notification was recommended for all sexual partners within 60 days prior to diagnosis or onset of symptoms, whichever occurred first, as per CDC sexual partner management guidelines.12 To help identify ways to target these constructs, we conducted several phases of pilot work, including a qualitative free-elicitation methodology aimed at identifying beliefs likely to impact patient referral for STI testing and treatment and reduction of sexual risk behavior.29

With this information, we developed a program and supporting materials that were culturally and linguistically appropriate for our sample population. This program consisted of 2 sessions. The first of these sessions was designed to occur in the clinic at the time of STI diagnosis. Activities to support behavior change included one-on-one counseling that involved discussion of any client behaviors that may have put him or her at risk for STI, identification of eligible sexual partners for notification, development of a sexual partner notification plan, role-playing exercises, and completion of a signed behavioral contract to notify sexual partners according to the notification plan. Identification of eligible sexual partners followed a method that has been successful in eliciting higher number of partners in other studies.30 Support materials included a written pamphlet summarizing steps to successful sexual partner notification as discussed with the health educator and provision of referral slips to give to sexual partners with information on where to access free, confidential STI testing and treatment. No personally identifying information was collected on any of the sexual partners discussed during the session.

The second session was designed to take place by phone or in person at a target of 4 weeks from the initial session; the absolute window for completion of this session was 2 to 10 weeks after the first session. Activities for the second session included a review of progress and discussion of any remaining barriers to completion of the notification process.

The resulting program and supporting materials were reviewed by members of the program's Community Advisory Group, and were also tested and revised based on a pilot sample of STI clinic patients. Modifications to graphics, wording, and content were conducted based on these reviews. All health educators were trained regarding appropriate techniques of interviewing and sexual partner elicitation and on STI epidemiology. Training was conducted by a disease intervention specialist at the New York City Department of Health and by project investigators.

Control Group Activities

Standard-of-care services regarding STI sexual partner notification occurred at each site. In addition, patients met with our program health educator. The health educator asked the client if he or she had any questions related to the clinic visit, diagnosis, treatment, or prevention. A brief discussion period followed if any questions arose. Patients were also provided with referral slips to give to sexual partners, as was provided in the intervention group. We chose to have the patient sit with the health educator for this interaction (as opposed to using the clinical standard of care alone) to allow for similar rapport-building opportunities between each of the 2 groups, and to help standardize messages provided to control group participants.

Randomization Procedures

Participants were randomized to intervention and control groups through a stratified block randomization algorithm, with stratifications by site of recruitment and gender within site. The randomization key was created by a computerized random number generator. The principal investigator preassigned study identification numbers to groups by using the random number generator, and participants were assigned study identification numbers sequentially as they enrolled in the study. The health educator conducted program activities as indicated by the identification number. Health educators were trained to provide both intervention and control activities and conducted appropriate activities based on the assigned participant's group. We also varied the clinic and clinic sessions for health educators to help minimize the impact of specific characteristics of the health educator.

Evaluation Procedures

Evaluation activities for the study included testing for N gonorrhoeae and C trachomatis at 6-month follow-up and completion of a standardized, interviewer-administered measure provided at baseline and at 1 and 6 months after baseline. The baseline interview took place before any intervention activities, and the 1-month interview took place after all health education activities had taken place. Study interviewers were not employees of study clinics, nor did they engage in any health education activities with participants with whom they completed study instruments. Study interviewers were not informed of participant group assignment.

Our primary outcome was self-reported sexual partner notification. We assessed sexual partner notification activities at an interview 1 month after baseline. The timing of this interview was chosen to help maximize recall of sexual partner notification behaviors and to help assess the impact of early notification behaviors on subsequent risk for STI. Each participant was asked to report whether they had engaged in sexual partner notification activities, and whether any deleterious effects resulted from engaging in partner notification, including arguments or instances of physical violence.

Secondary outcomes included safer sexual behavior and STI infection at 6 months. At the 6-month evaluation, sexual behavior was assessed over the previous 90 days. Respondents were asked to report on the total number of sexual partners, gender of partners, whether they had engaged in vaginal or anal intercourse, and the consistency of condom use during vaginal and anal intercourse. Questions about number of sexual partners, sexual behaviors, and condom use consistency were asked separately for main, casual, and “1-time” or anonymous sexual partners. The question stems, response categories, and the timeframe for recall have been found to have adequate reliability and validity across a number of studies.31–35 We derived from these variables an estimate reflecting whether the respondent reported any episode of unprotected anal or vaginal intercourse during the recall period, as in other evaluations of sexual risk reduction programs.36

To assess STI infection at 6 months, we used the Becton Dickinson BD ProbeTec system (BD Biosciences, Sparks, MD) for simultaneous diagnoses of C trachomatis and N gonorrhoeae in urine specimens. The BD ProbeTec system uses strand displacement amplification for detection and has been found to be highly sensitive and specific.37–39 First-void urine specimens were collected and processed within 48 hours, with specimens labeled only by study identification. If patients were positive for infection, they were contacted by study staff and referred to a clinic provider for appropriate treatment. For quality assurance, training and standardization of methods for laboratory and specimen collection were continuous.

On the basis of previous research in the area of sexual partner notification, we posited that the strength of the relationship between intervention activities and partner notification, sexual behavior, and STI infection would be influenced by participant gender.40 We also assessed whether racial/ethnic identification impacted the relationship between intervention activities and study outcomes. These factors were assessed at the baseline interview, along with questions about sexual behaviors identical to the 6-month measures. Other sociodemographic and behavioral variables were assessed at baseline to help characterize the study population and to compare individuals assigned to intervention and control groups.

Statistical Methods

We used analyses of variance (repeated-measures analysis of variance) for continuous predictor variables and χ2 for dichotomous predictor variables to conduct comparisons of those who accepted versus declined study participation, of those who maintained study participation to the end of the program versus those lost to follow-up, and of those randomized to intervention and control groups. We used an intention-to-treat approach to conduct outcome analyses.

We used separate multiple logistic regression models to predict the likelihood of (1) having engaged in sexual partner notification at 1 month, (2) reporting any episode of unprotected anal or vaginal intercourse in the past 90 days at 6-month follow-up, and (3) a positive nucleic acid amplification test for C trachomatis or N gonorrhoeae at 6 months. For each multiple logistic regression, we utilized generalized estimating equations to account for the study design whereby gender was nested within site. Intervention group membership was entered as the primary independent variable, with adjustment for age, baseline number of partners, and baseline diagnosis. We assessed the interaction effect of gender with group membership on each of our 3 outcomes and also examined whether there were interactions with participant's identification as African American or African Caribbean. Statistical significance for all calculations was defined as a P value at less than .05 based on a 2-tailed test of significance. All statistical procedures were conducted with SPSS version 15.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

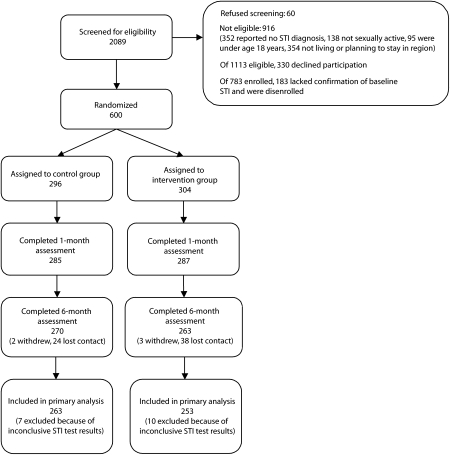

Between January 2002 and December 2004, we screened 2089 patients. Of these, 60 (3%) refused screening and 916 (44%) were not eligible on the basis of screening questions. Many of those who were ineligible reported that they had not been told, by the time of study screening, that they had gonorrhea or chlamydial infection (n = 352; Figure 1), and others reported plans to relocate prior to the end of study activities (n = 354). Of 1113 eligible persons, 783 (70%) agreed to participate. Of these 783, 183 (23%) were subsequently disenrolled, because their confirmatory tests were either negative for both infections or inconclusive. Of the 600 participants enrolled (304 in the intervention group and 296 in the control group), 520 had baseline diagnoses confirmed through nucleic acid amplification testing. Of the other 80 participants, all of whom were enrolled for gonorrhea, 57 had diagnoses confirmed via Gram stain and 23 via culture.

FIGURE 1.

Study participant flowchart of patients presenting for care at 2 sexually transmitted infection (STI) clinics: New York, NY, 2002–2004.

Note. CT = Chlamydia trachomatis; GC = Neisseria gonorrhoeae; NAAT = nucleic acid amplification testing.

At baseline, participants identified as African American (40%) and African Caribbean (52%), with 55% born in the United States. All participants were sexually active, and most reported exclusively opposite-sex sexual partners (96%). Control participants were more likely to have been diagnosed with chlamydia, and intervention participants were more likely to have been diagnosed with gonorrhea; groups did not differ in terms of other sociodemographics, sexual behaviors, self-reported STI history, or whether patient referral of sexual partners was recommended by a clinician prior to intervention activities (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients (N = 600) With Neisseria gonorrhoeae or Chlamydia trachomatis Presenting for Care at 2 Sexually Transmitted Infection (STI) Clinics: New York, NY, 2002–2004

| Control Group (n = 296) Mean (SD) or % | Intervention Group (n = 304) Mean (SD) or % | Participants, No. | P | |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Age, y | 24.9 (6.5) | 25.1 (6.9) | 600 | .69 |

| Female | 42 | 40 | 600 | .60 |

| Study site 1 | 43 | 41 | 600 | .54 |

| Born in United States | 54 | 55 | 600 | .89 |

| Race/ethnicity | 600 | |||

| African American | 42 | 38 | .99 | |

| Afro-Caribbean | 50 | 55 | .87 | |

| Other | 8 | 7 | .41 | |

| Hispanic | 12 | 9 | 600 | .19 |

| Married or living with a sexual partner | 27 | 28 | 600 | .80 |

| Completed high school or equivalent | 60 | 64 | 599 | .26 |

| Have full-time employment | 42 | 42 | 599 | .99 |

| Clinic experiences | ||||

| Presented to clinic with STI symptoms | 58 | 63 | 600 | .24 |

| Baseline diagnosis | 600 | |||

| Chlamydia | 52 | 42 | .99 | |

| Gonorrhea | 35 | 43 | .01 | |

| Both | 13 | 15 | .21 | |

| Received provider advice to notify sexual partners prior to study activities | 91 | 94 | 600 | .14 |

| Sexual behaviors | ||||

| Two or more sexual partners, past 3 months | 55 | 54 | 600 | .72 |

| Sexual behaviors with main sexual partners, past 3 months | ||||

| Vaginal intercourse | 84 | 83 | 600 | .60 |

| Consistent condom use during vaginal intercourse | 10 | 8 | 502 | .62 |

| Anal intercourse | 11 | 12 | 600 | .79 |

| Consistent condom or barrier use during anal intercourse | 26 | 16 | 71 | .29 |

| Sexual behaviors with casual sexual partners, past 3 months | ||||

| Vaginal intercourse | 39 | 35 | 600 | .27 |

| Consistent condom use during vaginal intercourse | 32 | 30 | 224 | .68 |

| Anal intercourse | 6 | 4 | 600 | .30 |

| Consistent condom or barrier use during anal intercourse | 47 | 50 | 29 | .88 |

| Sexual behaviors with 1-time sexual partners | ||||

| Vaginal intercourse | 24 | 26 | 600 | .64 |

| Consistent condom use during vaginal intercourse | 56 | 55 | 149 | .88 |

| Anal intercourse | 4 | 2 | 600 | .15 |

| Consistent condom or barrier use during anal intercourse | 61 | 57 | 20 | .84 |

| Any unprotected vaginal or anal intercourse, past 3 months | 89 | 91 | 593 | .65 |

One-month follow-up evaluations began February 2002, and 6-month evaluations began June 2002. In total, 572 participants completed the 1-month interview (96% control, 94% intervention; P = .28) and 533 participants (89%) completed the 6-month interview (91% control, 87% intervention; P = .07). Those who completed all evaluation activities (n = 533) were not different from those who did not (n = 67) in terms of baseline characteristics including age, gender, racial or ethnic identification, being born in the United States, being married or living with a sexual partner, lifetime STI history, being STI symptomatic, STI diagnosis, or reporting multiple partners (all P > .05). Completion of the 6-month evaluation visit was higher at 1 of our 2 study sites (92% vs 84% completion; P = .001).

Program Implementation

Median time to completion was 30 minutes (mean = 29 minutes; SD = 8) for the first session and 10 minutes for the second session (mean = 11 minutes; SD = 4). All patients assigned to the intervention group received the first session, and 59% completed the second session within the allotted window. Completion of both educational sessions was not associated with baseline characteristics including study site, age, racial or ethnic identification, being born in the United States, being married or living with a sexual partner, lifetime history of STI, being STI symptomatic, STI diagnosis, or reporting multiple partners (all P > .05). Women were more likely than were men to complete both program sessions (53% male, 68% female completion; P = .02).

Partner Notification, Risk Behavior, and STI Rates

Compared with control group participants, those assigned to the intervention group were more likely to have notified at least 1 sexual partner of possible STI exposure at the 1-month interview and were less likely to have reported 1 or more acts of unprotected vaginal or anal intercourse at the 6-month interview (Table 2). Among those who reported having engaged in sexual partner notification, 33% (n = 167) reported having an argument or fight, and 4% (n = 21) reported physical violence after engaging in notification. There were no differences in rates of reported arguments (P = .92) or violence (P = .96) between groups.

TABLE 2.

Sexual Partner Notification Outcomes Among Patients With Neisseria gonorrhoeae or Chlamydia trachomatis Presenting for Care at 2 Sexually Transmitted Infection Clinics, by Control Versus Intervention Group and Gender: New York, NY, 2002–2004

| Notified 1 or More Partners, 1 Month |

Unprotected Anal or Vaginal Intercourse, 6 Months |

Gonorrhea or Chlamydial Infection, 6 Months |

|||||||

| Control | Intervention | P | Control | Intervention | P | Control | Intervention | P | |

| Total, no. | 285 | 287 | 268 | 261 | 263 | 253 | |||

| Overall, % | 86 | 92 | .04 | 62 | 52 | .02 | 11 | 6 | .02 |

| Gender, % | .47a | .55a | .03a | ||||||

| Men | 85 | 93 | 61 | 53 | 12 | 3 | |||

| Women | 87 | 90 | 63 | 51 | 11 | 10 | |||

Note. Analyses were adjusted for baseline sexually transmitted infection diagnosis, age, and baseline number of sexual partners.

Gender by group interactions.

Of 533 participants who completed the 6-month follow-up, 516 (97%) had conclusive results from the urine analysis; the remaining 17 samples were collected and analyzed but were inconclusive. Persons with conclusive results were not different from those with inconclusive results in terms of sociodemographic characteristics, STI history, or baseline sexual risk behaviors (all P > .05). C trachomatis or N gonorrhoeae was detected in urine samples of 11% of control and 6% of intervention participants; control group participants were more than 2 times more likely to have a positive test result than were those in the intervention group (adjusted odds ratio = 2.15; 95% confidence interval = 1.12, 4.14). Among those in the intervention group who finished only the first intervention session, rates of gonorrhea or chlamydial infection at 6 months were 9%; among those who completed both sessions, rates of gonorrhea or chlamydial infection at 6 months were 4% (P = .13).

Among those who reported having engaged in sexual partner notification, rates of gonorrhea or chlamydial infection were 6% in the intervention and 12% in the control group (P = .04). Among those who did not report sexual partner notification, rates of gonorrhea or chlamydial infection were 4% in the intervention and 10% in the control group (P = .41). The test for an interaction between these variables was not statistically significant (for interaction, adjusted P = .98). Reporting an episode of unprotected sexual intercourse was not related to gonorrhea or chlamydial infection (P = .67), nor did these relationships differ as a function of group membership (for interaction, adjusted P = 0.95).

Interactions With Outcome Effects

The interaction of gender and group membership on follow-up STI testing was statistically significant (P = .03; Table 2). Among men, rates of gonorrhea or chlamydial infection were 12% for the control and 3% for the intervention group (P = .01). Among women, rates of gonorrhea or chlamydial infection were 11% for the control and 10% for the intervention group (P = .82). We did not detect statistically significant interactions between group membership and other primary and secondary outcomes as a function of racial/ethnic identification.

DISCUSSION

Our evaluation of a clinic-based program to promote effective STI partner notification revealed improvements in self-reported sexual partner notification, decreases in sexual risk behavior, and a reduction in recurrent or persistent infection among index patients. Although we had hoped that our intervention would reduce risks for arguments and violence as a result of the sexual partner notification process, there were no differences in these variables as a function of group membership.

The reduction in infection was seen primarily among men. Women in both groups had infection rates similar to those reported among men in the control group. These differences were not accounted for by differences in baseline number of sexual partners. Previous research has shown that men were less likely than were women to have their sexual partners treated,40 and this result was therefore not surprising. We did not, however, detect interactions with intervention group and gender on sexual partner notification behaviors or on sexual risk behaviors. There may have been partner-specific factors not accounted for in our design that impeded male sexual contacts from presenting for care. Or, it may have been that women were not notifying the sexual partners most likely to have infection. Additional research should address these issues, and build considerations for gender differences into sexual partner management approaches. This is particularly important given some estimates that having male sexual partners of female index patients treated is more cost-effective than having female sexual partners of male index patients treated, in terms of prevention of pelvic inflammatory disease.41

Our findings should be considered in light of several factors. First, although our intervention was relatively brief, a 30-minute counseling session with a follow-up phone contact would still be impractical to implement in many STI treatment venues, such as primary care settings, emergency departments, or in busy public STI clinics. Given that most people seek STI-related care in alternate settings,42 further work would need to demonstrate whether effects could be translated effectively to different clinical environments and whether the program could be adapted to fit the needs of diverse populations.

Second, we found that fewer than 60% of participants completed the second session within the allotted window and that completion of the second session was unrelated to STI outcomes within our specific population and setting. It is likely that the clinic-based, in-depth initial session was the important factor in sexual partner notification behaviors. Future research should be conducted to further evaluate the essential elements of the program. Third, many patients (17%) were screened out for reporting that they may not reside in the geographic area for the full study period. Although our sample reflected the racial/ethnic composition of the patient census at our sites of recruitment, there is still a potential of sampling bias. It is possible that foreign-born patients, who might be more likely to report plans to leave the area during the study period, had a higher likelihood of being screened out of the study. Finally, for this analysis, sexual partner notification was defined as a report of having successfully notified at least 1 sexual partner at the 1-month follow-up. This variable, although it is informative as an overall index of initiation of sexual partner notification efforts, is only partially descriptive. For instance, this measure cannot be used to ascertain whether notification was done with the sexual partner who was the original source of infection, nor is it known whether our program resulted in a greater number of sexual partners successfully identified and treated.

Findings from this study are timely in light of recent attention to the issue of providing “expedited therapy” to sexual partners of index patients. Expedited therapy is an approach to sexual partner treatment in which an index patient is provided medication to give to sexual partners. In a recent evaluation of this approach, follow-up rates of infection among those who had received expedited therapy compared with patient referral were significantly lower for gonorrhea and chlamydial infections.43 Although that finding presents an important model for the management of sexual partners of index patients, it has been noted that this approach carries with it the risk that notified sexual partners who may have otherwise presented for care would not have the opportunity to benefit from clinic-based prevention services.44 Improved patient referral strategies such as the one presented here add another tool to existing models of sexual partner management.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (grant R30 CCR219136).

The authors would like to thank the following people for their contributions to data collection: Angelette Cintron, Rhonda Curney, and Joy Williams (State University of New York Downstate) who were paid for their contributions; Lucindy Williams (New York City Department of Health) and Lorraine DuBouchet and Chellyanne Hinds (Kings County Hospital Center); and the staff and administrators at the Kings County Hospital Center; the New York City Department of Health, Bureau of Sexually Transmitted Disease Control; and the New York City Department of Health Sexually Transmitted Disease Clinic.

Note. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Human Participant Protection

Institutional review board approval was received at all participating sites, and all participants provided consent for all study procedures. All study procedures were approved by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.Cates W., Jr Estimates of the incidence and prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases in the United States. American Social Health Association Panel. Sex Transm Dis. 1999;26(4 suppl):S2–S7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller WC, Zenilman JM. Epidemiology of chlamydial infection, gonorrhea, and trichomoniasis in the United States—2005. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2005;19:281–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trends in Reportable Sexually Transmitted Diseases in the United States, 2005: National Surveillance Data for Chlamydia, Gonorrhea, and Syphilis. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Hidden Epidemic: Confronting Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aral SO. Sexually transmitted diseases: magnitude, determinants and consequences. Int J STD AIDS. 2001;12:211–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tracking the Hidden Epidemics: Trends in STDs in the United States 2000. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mertz KJ, McQuillan GM, Levine WC, et al. A pilot study of the prevalence of chlamydial infection in a national household survey. Sex Transm Dis. 1998;25:225–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trends in Reportable Sexually Transmitted Diseases in the United States, 2003. National Data on Chlamydia, Gonorrhea, and Syphilis. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coleman PJ, McQuillan GM, Moyer LA, Lambert SB, Margolis HS. Incidence of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States, 1976–1994: estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. J Infectious Dis. 1998;178:954–959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fleming DT, Wasserheit JN. From epidemiological synergy to public health policy and practice: the contribution of other sexually transmitted diseases to sexual transmission of HIV infection. Sex Transm Infect. 1999;75:3–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Racial/ethnic disparities in diagnoses of HIV/AIDS—33 states, 2001–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55:121–125 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Workowski KA, Berman SM. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-11):1–94 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farley TA, Cohen DA, Elkins W. Asymptomatic sexually transmitted diseases: the case for screening. Prev Med. 2003;36:502–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mathews C, Coetzee N, Zwarenstein M, et al. A systematic review of strategies for partner notification for sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV/AIDS. Int J STD AIDS. 2002;13:285–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macke BA, Maher JE. Partner notification in the United States: an evidence-based review. Am J Prev Med. 1999;17:230–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oxman AD, Scott EA, Sellors JW, et al. Partner notification for sexually transmitted diseases: an overview of the evidence. Can J Public Health. 1994;85(suppl 1):S41–S47 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Golden MR, Hogben M, Handsfield HH, St Lawrence JS, Potterat JJ, Holmes KK. Partner notification for HIV and STD in the United States: low coverage for gonorrhea, chlamydial infection, and HIV. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30:490–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.St Lawrence JS, Montaño DE, Kasprzyk D, Phillips WR, Armstrong K, Leichliter JS. STD screening, testing, case reporting, and clinical and partner notification practices: a national survey of US physicians. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1784–1788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Potterat JJ, Rothenberg R. The case-finding effectiveness of self-referral system for gonorrhea: a preliminary report. Am J Public Health. 1977;67:174–176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woodhouse DE, Potterat JJ, Muth JB, Pratts CI, Rothenberg RB, Fogle JS., II A civilian–military partnership to reduce the incidence of gonorrhea. Public Health Rep. 1985;100:61–65 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van de Laar MJ, Termorshuizen F, van den Hoek A. Partner referral by patients with gonorrhea and chlamydial infection. Case-finding observations. Sex Transm Dis. 1997;24:334–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chacko MR, Smith PB, Kozinetz CA. Understanding partner notification (Patient self-referral method) by young women. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2000;13:27–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Golden MR, Whittington WL, Handsfield HH, et al. Partner management for gonococcal and chlamydial infection: expansion of public health services to the private sector and expedited sex partner treatment through a partnership with commercial pharmacies. Sex Transm Dis. 2001;28:658–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fortenberry JD, Brizendine EJ, Katz BP, Orr DP. The role of self-efficacy and relationship quality in partner notification by adolescents with sexually transmitted infections. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:1133–1137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jarvis RR, Curless E, Considine K. Outcome of contact tracing for Chlamydia trachomatis in a district general hospital. Int J STD AIDS. 1999;10:250–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Low N, McCarthy A, Roberts TE, et al. Partner notification of chlamydia infection in primary care: randomised controlled trial and analysis of resource use. BMJ. 2006;332:14–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31:143–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1975 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brewer DD, Garrett SB. Evaluation of interviewing techniques to enhance recall of sexual and drug injection partners. Sex Transm Dis. 2001;28:666–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Upchurch DM, Weisman CS, Shepherd M, et al. Interpartner reliability of reporting of recent sexual behaviors. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;134:1159–1166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Udry J, Morris N. A method for validation of reported sexual data. J Marriage Fam. 1967;29:442–446 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jaccard J, McDonald R, Wan CK, Guilamo-Ramos V, Dittus P, Quinlan S. Recalling sexual partners: the accuracy of self-reports. J Health Psychol. 2004;9:699–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jaccard J, Wan CK. A paradigm for studying the accuracy of self-reports of risk behavior relevant to AIDS: empirical perspectives on stability, recall bias, and transitory influences. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1995;25:1831–1858 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fishbein M, Pequegnat W. Evaluating AIDS prevention interventions using behavioral and biological outcome measures. Sex Transm Dis. 2000;27:101–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Richardson JL, Milam J, McCutchan A, et al. Effect of brief safer-sex counseling by medical providers to HIV-1 seropositive patients: a multi-clinic assessment. AIDS. 2004;18:1179–1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Der Pol B, Ferrero DV, Buck-Barrington L, et al. Multicenter evaluation of the BDProbeTec ET System for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in urine specimens, female endocervical swabs, and male urethral swabs. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:1008–1016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Akduman D, Ehret JM, Messina K, Ragsdale S, Judson FN. Evaluation of a strand displacement amplification assay (BD ProbeTec-SDA) for detection of Neisseria gonorrhoeae in urine specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:281–283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chan EL, Brandt K, Olienus K, Antonishyn N, Horsman GB. Performance characteristics of the Becton Dickinson ProbeTec System for direct detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in male and female urine specimens in comparison with the Roche Cobas System. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:1649–1652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Apoola A, Mantella I, Wotton M, Radcliffe K. Treatment and partner notification outcomes for gonorrhoea: effect of ethnicity and gender. Int J STD AIDS. 2005;16:287–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Howell MR, Kassler WJ, Haddix A. Partner notification to prevent pelvic inflammatory disease in women. Cost-effectiveness of two strategies. Sex Transm Dis. 1997;24:287–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brackbill RM, Sternberg MR, Fishbein M. Where do people go for treatment of sexually transmitted diseases? Fam Plann Perspect. 1999;31:10–15 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Golden MR, Whittington WL, Handsfield HH, et al. Effect of expedited treatment of sex partners on recurrent or persistent gonorrhea or chlamydial infection. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:676–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Erbelding EJ, Zenilman JM. Toward better control of sexually transmitted diseases. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:720–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]