Abstract

AIM: To test this hypothesis of barrett esophagus (BE) classified into two types and to further determine if there was any correlation between the shape of endoscopically suspected esophageal metaplasia (ESEM), prevalence of reflux esophagitis (RE) and heartburn.

METHODS: A total of 6504 Japanese who underwent endoscopy for their annual stomach check-up were enrolled in this study. BE was detected without histological confirmation that is ESEM. We originally classified cases of ESEM into 3 types based on its shape: Tongue-like (T type), Dome-like (D type) and Wave-like (W type) ESEM. The respective subjects were prospectively asked to complete questionnaires concerning the symptoms of heartburn, dysphagia, and abdominal pain for a one-month period.

RESULTS: ESEM was observed in 10.3% of 6504 subjects (ESEM < 1 cm, 9.4%; 1 cm ≤ ESEM < 3 cm, 1.7%; ESEM ≥ 3 cm, 0.5%). The frequency of ESEM was significantly higher in males compared with female subjects. Statistical analysis showed that the prevalence of heartburn and RE were significantly higher in the T type ESEM than in the W type ESEM (P < 0.05).

CONCLUSION: The T type ESEM was strongly asso-ciated with reflux symptoms and RE whereas the W type ESEM was not associated with GERD.

Keywords: Tongue-like endoscopically suspected esophageal metaplasia, Dome-like endoscopically suspected esophageal metaplasia, Wave-like endoscopically suspected esophageal metaplasia, Gastroesophageal reflux disease

INTRODUCTION

Barrett’s esophagus (BE) is considered to be a significant complication of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) due to its association with adenocarcinoma[1]. For many years, BE was considered as an acquired disorder that developed as a result of GERD[2]. Patients with BE tended to have higher esophageal acid exposure compared with normal subjects, patients with non-erosive reflux disease, or those with erosive esophagitis[3]. The age of onset, duration of symptoms, and complications of GERD have been also demonstrated to be markers for increased risk of BE[4]. Interestingly, similar clinical risk factors were identified for esophageal adenocarcinoma[5].

According to Montreal definitions, the term endoscopically suspected esophageal metaplasia (ESEM) describes endoscopic findings consistent with BE that await histological evaluation[6]. The epidemiology of ESEM in Japan has been investigated[7,8]. It has been reported that the prevalence of long-segment ESEM was estimated to be 0.2%-0.4%[7], which is consistent with reports from several other studies[8]. However, there appears to be considerable variation in reports of prevalence of short segment ESEM. The estimated range of short segment ESEM has been reported, varying from 6.0%-20.6%[7,8]. It is difficult to compare previous reports on the prevalence of ESEM because of the diverse methodologies used and the different methods of sample selection. However, because of considerable differences in the reported prevalence of short segment ESEM, we hypothesize that short segment ESEM may not always be associated with reflux esophagitis (RE). In fact, there are paradoxical reports in which no association between RE and BE has been reported[9]. Although ESEM is generally a complication of GERD, some cases of ESEM, especially the short segment type, have an obscure connection with GERD[10,11]. Therefore, ESEM may be best described as having two types: ESEM non-short segment type, which is closely associated with GERD, and ESEM short segment type, which may not be associated with GERD.

The aim of the present study was to determine whether there was a correlation between the shape and localization of ESEM and the prevalence of GERD.We also tested the hypothesis that ESEM might result from replacement of erosions in RE, thus we compared the circumferential involvement by erosions in RE and ESEM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

A total of 160 983 Japanese patients (male/female, 60 774/100 209; mean age, 61.9 ± 11.1), who underwent a stomach exam at the Miyagi Cancer Society between January and December 2003, were enrolled in this study. In order to check for gastric cancer, X-ray examinations were performed on all enrolled subjects. In addition, we evaluated disease classifications based on X-ray examinations. There were 15 616 subjects in whom further endoscopic testing was necessary because they were suspected of having gastric cancer. From this group, a total of 6504 subjects (male/female, 3197/3307; mean age 62.7 ± 10.7) who underwent further endoscopic testing at the above center between January and December 2003 were enrolled in this study.

Endoscopic findings

At the Miyagi Cancer Society, when endoscopically examining and photographing the esophageal mucosa, the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) is always prospectively photographed, and the ventral side of the esophagus is positioned at 12 o’clock, in the top upper part of the photograph. The Miyagi Cancer Society operates a digital filing system for endoscopic images (ScopeReader DCR. Rise Co., Ltd). All digital endoscopic images were independently and retrospectively reviewed by two endoscopists to investigate the presence and localization of RE and ESEM. If there was any inconsistency in the assessment of the digital endoscopic images, a final diagnosis was decided upon by a joint review of the digital endoscopic images. Furthermore, if less than 60% of the esophageal mucosa could be seen in any photograph, that patient was excluded from the analysis. A total of 134 cases were excluded from the analysis because of difficulty in assessment.

ESEM

Although endoscopy with biopsy is the only validated technique to diagnose BE[6], it has clear limitations as a screening tool due to cost, risk, and complexity. We therefore chose to assess ESEM in study patients.Diagnosed ESEM was defined as any length of columnar epithelium that extended continuously from the gastric lumen to the esophagus, and the GEJ was defined as the end of the palisade vessel of the lower esophagus[12]. If palisade vessels were not visible, the proximal margin of the gastric fold was used for detection of the GEJ. Furthermore, we also defined ESEM based on length and the following grading system was used.

Length of ESEM

ESEM < 1: Defined as segments of columnar epithe-lium from the GEJ measuring <1 cm in length; 1 ≤ ESEM < 3: Defined as segments of columnar epithelium from the GEJ measuring 1 ≤ ESEM<3 cm in length; ESEM ≥ 3: Defined as segments of columnar epithelium from the GEJ (measuring at the uppermost extent of red columnar epithelium) ≥ 3 cm in length, whether the columnar lining was circumferential or not.

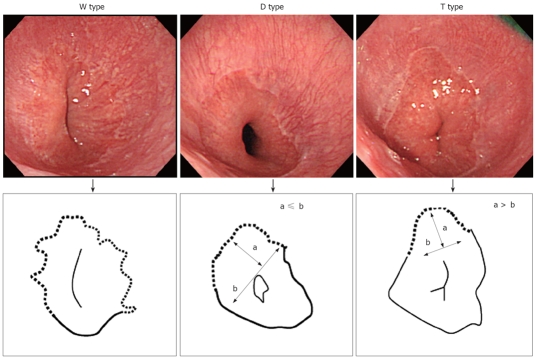

Shape of ESEM

We originally classified ESEM into 3 types based on shape. As shown in Figure 1, we classified the shape of ESEM as the following: (1) W type, in which the ESEM was defined by a columnar epithelium that extended continuously from the gastric lumen to the esophagus, in which the uppermost extent of the visible red columnar epithelium could be observed as a wave-like formation. The broken line in Figure 1 shows this type of ESEM; (2) D type, in which the length of basal part of the ESEM (b) was longer than the length of the major part of the ESEM (a) (i.e. a < b). The columnar epithelium of the ESEM is observed as a dome-like shape. The broken line in Figure 1 shows this type of ESEM; (3) T type, in which the length of the major axis of the ESEM (a) is longer than the basal part of ESEM (b) (i.e. a ≥ b). The columnar epithelium of the ESEM is observed as a tongue-like shape.

Figure 1.

The shape of ESEM. We originally divided ESEM into 3 types based on its shape. The W type, in which the ESEM was defined by a columnar epithelium which extended continuously from the gastric lumen to the esophagus, in which the uppermost extent of the visible red columnar epithelium could be observed as a wave-like formation (W). The broken line in the illustration shows the ESEM. The D type, in which the length of basal part of the ESEM (b) was longer than the length of the major part of the ESEM (a; i.e. a < b) The columnar epithelium of the ESEM is observed as a dome-like shape (D). The broken line in the illustration shows the ESEM. The T type in which the length of the major axis of the ESEM (a) is longer than the basal part of ESEM (b; i.e. a ≥ b). The columnar epithelium of the ESEM is observed as a tongue-like shape (T).

Reflux esophagitis

RE is divided endoscopically into four grades, A to D, according to the severity of the mucosal breaks as defined by the Los Angeles (LA) classification[13]. A mucosal break was defined as "an area of slough or an area of erythema, with a discrete lined demarcation from the adjacent or normal looking mucosa"[13].

Localization of RE and ESEM

We also investigated the location in which mucosal breaks or ESEM occurred in the lower esophageal wall. The circumferential localization of mucosal breaks and the ESEM (according to shape) in the lower esophageal wall were determined according to the numbers on a clock face, with 12 o’clock always situated at the top of the photograph. When multiple mucosal breaks or ESEM were present, for example, grade A and B esophagitis or T type ESEM, the circumferential positions of all the mucosal breaks or ESEM were recorded. In cases of grade C esophagitis or W type ESEM, the transverse extent of the mucosal breaks or the ESEM was assessed, and all the directions in which lesions existed were counted.

Questionnaire

Table 1 showed the questionnaire used in this study. The subjects in each group were prospectively asked to complete the questionnaire concerning symptoms of heartburn, dysphagia, and abdominal pain within a one month period. The subjects were requested to simply answer “yes” or “no” to the symptoms, and if they answered “yes”, they were further questioned on the frequency of symptoms (“usually” or “sometimes”). In addition, concerning the symptom of dysphagia, subjects were asked where the symptom of dysphagia occurred (throat, chest, or stomach). Regarding abdominal pain, its relationship with meals, if any, was elicited. This questionnaire was designed as a self-reporting instrument to measure symptoms experienced over one month previous to returning the completed questionnaire.

Table 1.

Questionnaire used in this study

| Please circle the appropriate responses for each of the following symptoms during a 1-mo period | |

| Do you suffer from the symptom of dysphagia? | |

| 1: yes | 2: no |

| (a: usually; b: sometimes) | |

| (c: throat; d: chest; e: stomach) | |

| Do you suffer from the symptom of heartburn? | |

| 1: yes | 2: no |

| (a: usually; b: sometimes) | |

| Do you suffer from the symptom of abdominal pain? | |

| 1: yes | 2: no |

| (a: usually; b: sometimes) | |

| (f: before eating; g: after eating; h: no relation) | |

Statistical analyses

The Mann-Whitney U test for nonparametric data was used for statistical analysis to compare results among the groups with different ESEM lengths and clinical symptoms. The Kruskal-Wallis rank test was used for statistical analysis to compare the results among the groups with different ESEM shapes. Values were additionally expressed as frequencies. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

The study protocol

The study protocol was approved by the ethical committee of the Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine.

RESULTS

Study population

The mean age of the sample population was 62.7 ± 10.2 years. All subjects responded to the questionnaire on heartburn, dysphagia and abdominal pain. Because the majority of subjects (99%) gave the frequency of the respective symptoms as “sometimes”, the frequency of symptoms was omitted from our analysis. Among the 6504 subjects, 63 who had undergone some degree of stomach resection and 134 in whom judgment was difficult based on the digital photographic data were excluded from the final study analysis. Of the 6307 subjects in the final analysis, the mean age of the sample population was also 62.7 ± 10.2 years. Females accounted for 50.8% of the interviewed subjects (n = 3206).

The prevalence of ESEM

ESEM was observed in 10.3% of subjects (ESEM < 1 cm, 9.4%; 1 cm ≤ ESEM < 3 cm, 1.7%; ESEM ≥ 3 cm, 0.5%). The frequency of ESEM was significantly higher in males compared with female subjects (χ2 test).

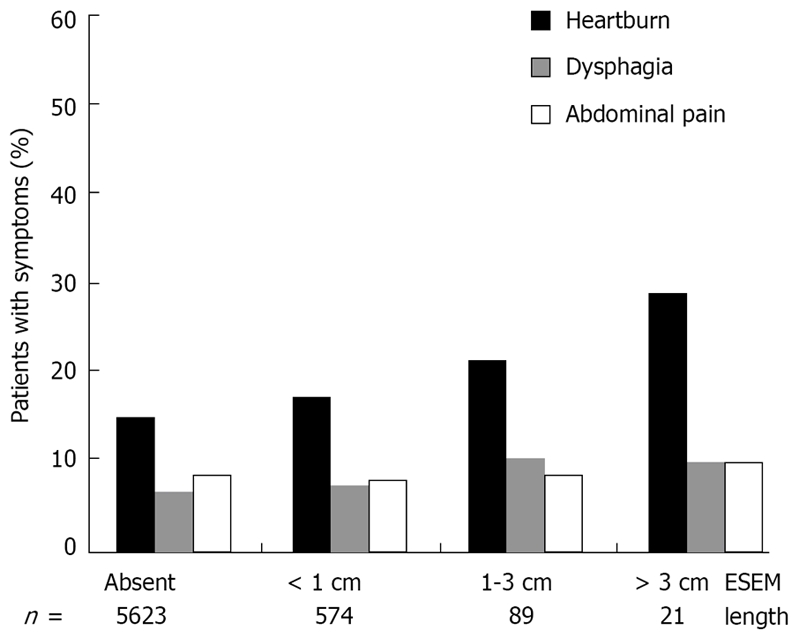

Correlation between ESEM and clinical symptoms

Figure 2 shows the correlation between ESEM length grading and each clinical symptom. The prevalence of heartburn significantly increased concomitantly with the endoscopic ESEM length grading (Mann-Whitney U test). No significance was observed between the length of the ESEM and the prevalence of dysphagia and abdominal pain (Mann-Whitney U test).

Figure 2.

Correlation between ESEM length grading and each clinical symptom. The prevalence of heartburn significantly increased in direct proportion to endoscopic ESEM length grading (P < 0.05). No significance was observed between the length of ESEM and symptoms of dysphagia and abdominal pain.

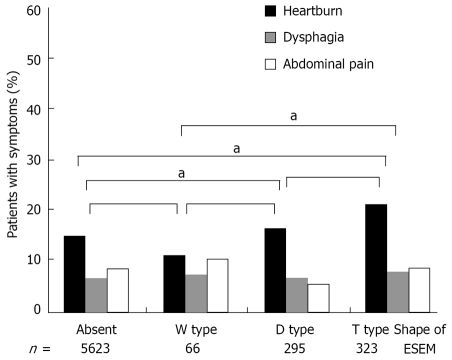

Figure 3 shows the correlation between ESEM shape and each clinical symptom. The prevalence of heartburn was significantly higher in T type ESEM than W type ESEM and those subjects who did not have ESEM (χ2 test). The subjects with T type ESEM tended to suffer from a high prevalence of heartburn compared to the subjects with D type ESEM, but without statistical significance (χ2 test). No significance was observed between the shape of the ESEM and the prevalence of dysphagia and abdominal pain (χ2 test).

Figure 3.

Correlation between the ESEM shape and each clinical symptom. The prevalence of heartburn significantly increased in the T type ESEM than the W type ESEM and ESEM-free patients (χ2 test; aP < 0.05).

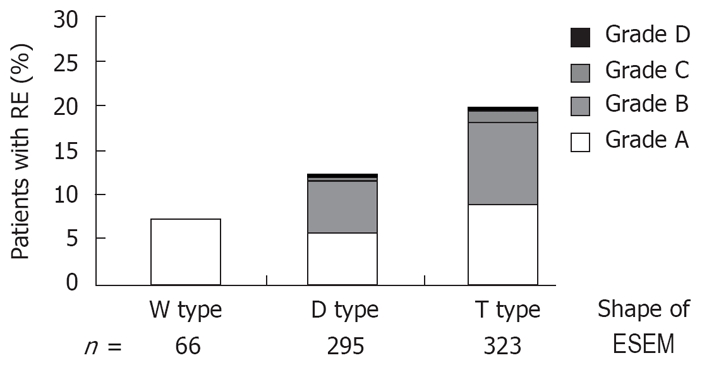

Correlation between ESEM and the prevalence of RE

Figure 4 shows the correlation between the shape of the ESEM and the prevalence of RE. The prevalence of RE was significantly higher in subjects with T type ESEM than those with the other shapes (Kruskal-Wallis rank test).

Figure 4.

Correlation between the shape of ESEM and the prevalence of RE. The prevalence of RE is significantly higher among those suffering from the T type ESEM (Kruskal-Wallis rank test, P < 0.05).

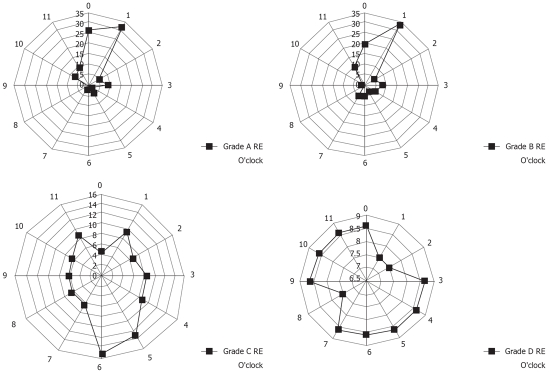

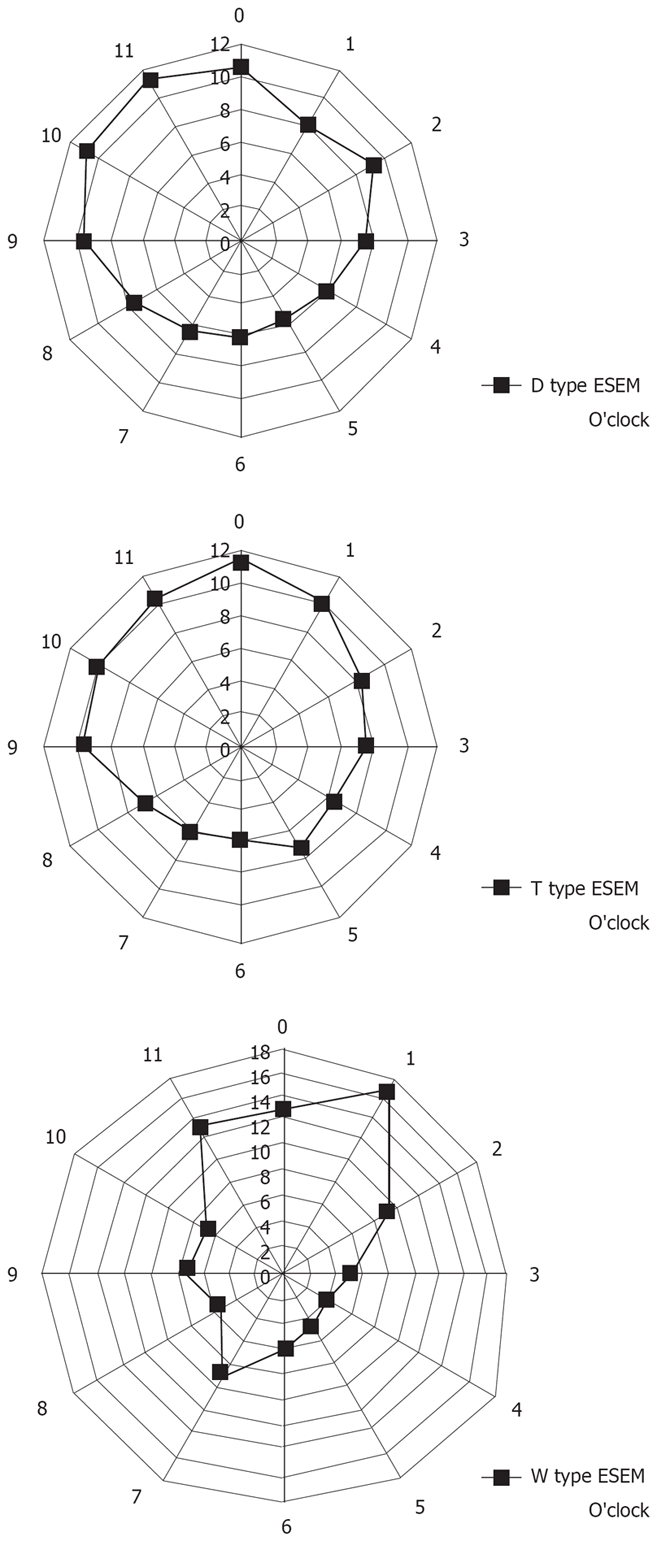

Localization of ESEM

Figure 5 shows the localization of ESEM. In subjects with T type ESEM, the ESEM was located mainly at the 12 o’clock and 1 o’clock wall (right anterior) of the lower esophagus, whereas in subjects with the D and W types, the ESEM was mainly located at the 9 o’clock to 12 o’clock wall (left anterior) of the lower esophagus. The circumferential location of the ESEM significantly differed among the different types of ESEM (χ2 test).

Figure 5.

The circumferential location of ESEM in subjects with the W, D, and T types of ESEM. Data are shown in terms of clock face orientation. The numbers represent the percentage of lesions on each side of the esophageal wall relative to the total number of lesions. The T-type ESEM is located mainly at the 12 and 1 o’clock wall (right anterior) of the lower esophagus, whereas the D and W types of ESEM are mainly located at the 9 to 12 o’clock wall (left anterior) of the lower esophagus. The circumferential distribution of ESEM differed significantly among subjects with different types of ESEM (χ2 test: P < 0.05, T vs D, D vs W and W vs T).

The prevalence of RE

The endoscopic results revealed that 6.3% (grade A 3.7%, grade B 2.3%, grade C 0.2%, grade D 0.1%) of the subjects had RE according to the LA classification. The prevalence of RE was significantly higher in males (7.7%) than in females (6.3%, χ2 test).

Localization of RE

Figure 6 shows the localization of mucosal breaks in the lower esophageal wall. Subjects with grade A and B esophagitis had longitudinal mucosal breaks mainly at the 12 o’clock and 1 o’clock wall of the lower esophagus, whereas subjects with grade C and D esophagitis had transverse mucosal breaks mainly at the 4 o’clock to 6 o’clock wall of the lower esophagus (Figure 6). The circumferential locations of esophageal mucosal breaks significantly differed among different grades of esophagitis.

Figure 6.

The circumferential location of esophageal mucosal breaks in subjects with grade A-D RE. Data are shown in terms of clock face orientation. The numbers represent the percentage of lesions on each side of the esophageal wall relative to the total number of lesions. Patients with grade A and B esophagitis had longitudinal mucosal breaks mainly at the 12 o’clock and 1 o’clock wall of the lower esophagus, whereas patients with grade C and D esophagitis had transverse mucosal breaks mainly at the 4 o’clock to 6 o’clock wall of the lower esophagus. The circumferential distribution of esophageal mucosal breaks differed significantly among subjects with different grades of RE (χ2 test: P < 0.05, A vs B, A vs C, A vs D, B vs C, B vs D and C vs D).

DISCUSSION

BE has been generally accepted as a complication of chronic and severe GERD[2–4]. It is currently accepted that BE places individuals at risk for the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma, which is the most rapidly increasing cancer in the United States[14]. Because the prevalence of RE in Japan is increasing to become near that of Western countries[15,16], there might be a tendency for an increased number of esophageal adenocarcinomas in the Japanese population in the future. The fact that clinical risk factors with BE were also identified for esophageal adenocarcinoma attracted our attention[17]. The more frequent, more severe, and longer lasting the symptoms of acid reflux are, the greater the risk is for the development of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus[5].

Although no one can doubt the importance of strong and chronic acid reflux in the development of BE, there is, however, doubt that all patients with BE will show characteristic GERD symptoms. Ronkainen et al reported that BE may not develop as a late consequence of RE[9]. It is reported that obesity and smoking and drinking habits are also risk factors for developing BE[9,18–21]. A familial aggregation study of BE has been reported[22]. Several studies on BE have been carried out in Japan[7,8]. Kawano et al reported that there is a weak association between short segment BE and RE.

In summary, controversy exists regarding the potential of BE to develop as a late consequence of RE[10,11]. Paradoxical reports lead us to the idea that there are at least two types of short segment BE: one type that is closely associated with GERD and one that is not associated with GERD. We decided to investigate the relationship between ESEM endoscopic findings and clinical symptoms. We hypothesized that ESEM could be distinguished into two morphologically different types, one of which is closely associated with GERD and the other not associated with GERD.

We elucidated a significant correlation between the ESEM shape and each clinical symptom. The prevalence of heartburn was significantly higher in T type ESEM than in W type ESEM and ESEM-free subjects. Furthermore, subjects with T type ESEM tended to be more symptomatic than the subjects with D type ESEM, and the prevalence of RE was highest in T type ESEM subjects. We found that T type ESEM was closely associated with GERD, whereas W type ESEM had a weak or no association with GERD.

We also hypothesized that T type ESEM might originate as a direct result of columnar replacement of areas damaged by RE. If this was correct, the localization of RE and localization of the T type ESEM should be in accord. Thus, we investigated the relationship between the localization of RE and ESEM and demonstrated that the localization of T type ESEM was also mainly at the 12 o’clock and 1 o’clock wall of the lower esophagus, which was similar in the case with grade A and B RE. This fact may support the proposition that RE plays an important part in the development of T type ESEM.

The reason why the circumferential location of esophageal mucosal breaks differs among different grades of esophagitis has not yet been fully investigated, but several speculative proposals have been put forward by Katsube et al and Winans[23,24]. Winans investigated the circumferential pressure of the lower esophageal sphincter, and confirmed that a significantly higher localized pressure existed in the orifices directed towards the left posterior quadrant of the esophagus in normal subjects without hiatal hernia. Differing degrees of pressure due to the circumferential asymmetry of the lower esophageal sphincter could be a major cause of the differences in the localization of RE. With these dynamic causes in grade A and B RE, the mucosal breaks mainly exist at the 12 o’clock and 1 o’clock wall of the lower esophagus mucosal breaks. We may surmise that the mild type of RE, which is the most prevalent form of RE in Japan, may lead to the development of T type ESEM.

Two studies[25,26] in particular have attracted our attention. It has been reported that the localization of dysplasia in BE and cardiac cancer is dominant at the 12 o’clock and 3 o’clock wall of the lower esophagus[25,26]. However, we did not detect any corroborative findings in histological examinations in this study, thus more epidemiological studies will be required to examine this issue further.

The present study has a potential limitation. We collected data from subjects who had undergone further endoscopic testing among subjects who were suspected of having gastric cancer (cancer s/o) based on an X ray examination. Subjects who were suspected of having gastric cancer might have had a high degree of atrophic gastritis that resulted in low acid output, whereby the prevalence of GERD might be relatively low compared to the general Japanese population.

In conclusion, the prevalence of heartburn and RE was significantly higher in the T type of ESEM. The localization of ESEM was similar to the localization of mild RE, which is the most prevalent form of RE in Japan. We therefore propose that T type ESEM may arise as a result of RE.

COMMENTS

Background

Although Barrett esophagus (BE) is generally in place as a complication of Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), some cases of BE, especially the short segment type, have an obscure connection with GERD.

Research frontiers

We hypothesized that endoscopically suspected esophageal metaplasia (ESEM) could be distinguished into two morphologically different types, one of which is closely associated with GERD, and the other not associated with GERD.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The controversy still exists regarding the potential of BE to develop as a late consequence of RE. These paradoxical reports lead us to the hypothesis that there are at least two type of short segment BE, namely one type that is closely associated with GERD, and one that is not associated with GERD.

Applications

The prevalence of heartburn was significantly higher in the Tongue like (T-type) ESEM than in the Wave-like (W type) ESEM, and the prevalence of RE was highest in T type ESEM subjects. We found that the T type ESEM was closely associated with GERD, whereas the W type ESE had a weak or no association with GERD.

Peer review

This is a good study that explores the possibility that Barrett’s esophagus is not a homogeneous entity, but its shape and location may suggest a correlation with reflux symptoms and GERD. The authors have done a systematic job and have based their conclusions on sound reasoning.

Peer reviewer: Dr. Philip Abraham, Professor, Consultant Gastro-enterologist & Hepatologist, P. D. Hinduja National Hospital & Medical Research Centre, Veer Savarkar Marg, Mahim, Mumbai 400 016, India

S- Editor Zhong XY L- Editor Lutze M E- Editor Zhang WB

References

- 1.Falk GW. Barrett's esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1569–1591. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kahrilas PJ. Gastroesophageal reflux disease. JAMA. 1996;276:983–988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dickman R, Bautista JM, Wong WM, Bhatt R, Beeler JN, Malagon I, Risner-Adler S, Lam KF, Fass R. Comparison of esophageal acid exposure distribution along the esophagus among the different gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) groups. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2463–2469. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eisen GM, Sandler RS, Murray S, Gottfried M. The relationship between gastroesophageal reflux disease and its complications with Barrett's esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lagergren J, Bergstrom R, Lindgren A, Nyren O. Symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux as a risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:825–831. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903183401101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900–1920; quiz 1943. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hongo M, Shoji T. Epidemiology of reflux disease and CLE in East Asia. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38 Suppl 15:25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hongo M. Review article: Barrett's oesophagus and carcinoma in Japan. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20 Suppl 8:50–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ronkainen J, Aro P, Storskrubb T, Johansson SE, Lind T, Bolling-Sternevald E, Vieth M, Stolte M, Talley NJ, Agreus L. Prevalence of Barrett's esophagus in the general population: an endoscopic study. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1825–1831. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hassall E. Barrett's esophagus: congenital or acquired? Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:819–824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nandurkar S, Talley NJ. Barrett's esophagus: the long and the short of it. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:30–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoshihara Y, Hashimoto M. [Endoscopic classification of reflux esophagitis] Nippon Rinsho. 2000;58:1808–1812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Armstrong D, Bennett JR, Blum AL, Dent J, De Dombal FT, Galmiche JP, Lundell L, Margulies M, Richter JE, Spechler SJ, et al. The endoscopic assessment of esophagitis: a progress report on observer agreement. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:85–92. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8698230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Devesa SS, Blot WJ, Fraumeni JF Jr. Changing patterns in the incidence of esophageal and gastric carcinoma in the United States. Cancer. 1998;83:2049–2053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El-Serag HB, Petersen NJ, Carter J, Graham DY, Richardson P, Genta RM, Rabeneck L. Gastroesophageal reflux among different racial groups in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1692–1699. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.03.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujimoto K, Iwakiri R, Okamoto K, Oda K, Tanaka A, Tsunada S, Sakata H, Kikkawa A, Shimoda R, Matsunaga K, et al. Characteristics of gastroesophageal reflux disease in Japan: increased prevalence in elderly women. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38 Suppl 15:3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Solaymani-Dodaran M, Logan RF, West J, Card T, Coupland C. Risk of oesophageal cancer in Barrett's oesophagus and gastro-oesophageal reflux. Gut. 2004;53:1070–1074. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.028076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chow WH, Blot WJ, Vaughan TL, Risch HA, Gammon MD, Stanford JL, Dubrow R, Schoenberg JB, Mayne ST, Farrow DC, et al. Body mass index and risk of adenocarcinomas of the esophagus and gastric cardia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:150–155. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El-Serag HB, Kvapil P, Hacken-Bitar J, Kramer JR. Abdominal obesity and the risk of Barrett's esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2151–2156. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Avidan B, Sonnenberg A, Schnell TG, Sontag SJ. Hiatal hernia and acid reflux frequency predict presence and length of Barrett's esophagus. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:256–264. doi: 10.1023/a:1013797417170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gerson LB, Shetler K, Triadafilopoulos G. Prevalence of Barrett's esophagus in asymptomatic individuals. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:461–467. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.34748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chak A, Lee T, Kinnard MF, Brock W, Faulx A, Willis J, Cooper GS, Sivak MV Jr, Goddard KA. Familial aggregation of Barrett's oesophagus, oesophageal adenocarcinoma, and oesophagogastric junctional adenocarcinoma in Caucasian adults. Gut. 2002;51:323–328. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.3.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katsube T, Adachi K, Furuta K, Miki M, Fujisawa T, Azumi T, Kushiyama Y, Kazumori H, Ishihara S, Amano Y, et al. Difference in localization of esophageal mucosal breaks among grades of esophagitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:1656–1659. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winans CS. Manometric asymmetry of the lower-esophageal high-pressure zone. Am J Dig Dis. 1977;22:348–354. doi: 10.1007/BF01072193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moriyama N, Amano Y, Okita K, Mishima Y, Ishihara S, Kinoshita Y. Localization of early-stage dysplastic Barrett's lesions in patients with short-segment Barrett's esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2666–2667. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00809_5.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Derakhshan MH, Yazdanbod A, Sadjadi AR, Shokoohi B, McColl KE, Malekzadeh R. High incidence of adenocarcinoma arising from the right side of the gastric cardia in NW Iran. Gut. 2004;53:1262–1266. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.035857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]