Abstract

Plasma α-linolenic acid (α-LNA, 18:3n-3) or linoleic acid (LA, 18:2n-6) does not contribute significantly to the brain content of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6n-3) or arachidonic acid (AA, 20:4n-6), respectively, and neither DHA nor AA can be synthesized de novo in vertebrate tissue. Therefore, measured rates of incorporation of circulating DHA or AA into brain exactly represent the rates of consumption by brain. Positron emission tomography (PET) has been used to show, based on this information, that the adult human brain consumes AA and DHA at rates of 17.8 and 4.6 mg/day, respectively, and that AA consumption does not change significantly with age. In unanesthetized adult rats fed an n-3 PUFA “adequate” diet containing 4.6% α-LNA (of total fatty acids) as its only n-3 PUFA, the rate of liver synthesis of DHA is more than sufficient to replace maintain brain DHA, whereas the brain’s rate of synthesis is very low and unable to do so. Reducing dietary α-LNA in an DHA-free diet fed to rats leads to upregulation of liver coefficients of α-LNA conversion to DHA and of liver expression of elongases and desaturases that catalyze this conversion. Concurrently, the brain DHA loss slows due to downregulation of several of its DHA-metabolizing enzymes. Dietary α-LNA deficiency also promotes accumulation of brain docosapentaenoic acid (22:5n-6), and upregulates expression of AA-metabolizing enzymes, including cytosolic and secretory phospholipase A2 and cyclooxygenase-2. These changes, plus reduced levels of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB), likely render the brain more vulnerable to neuropathological insults.

Keywords: docosahexaenoic acid, liver, brain, rat, n-3 PUFAs, imaging, metabolism, phospholipase A2, BDNF, diet, arachidonic acid

1. Introduction

Brain structure and function, particularly neurotransmission, depend on interactions between arachidonic acid (AA, 20:4n-6) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6n-3) at multiple target sites 1–6. These long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) and their respective shorter-chain PUFA precursors, linoleic acid (LA, 18:2n-6) and α-linolenic acid (α-LNA, 18:3n-3), are nutritionally essential and cannot be synthesized de novo in vertebrate tissue 7.

Animal studies with different proportions of PUFAs in the diet have identified broad dietary requirements for maintaining optimal brain function 8, and have demonstrated that metabolic and behavioral defects arise from severe long-term n-3 PUFA dietary deprivation. Additionally, clinical studies indicate that low dietary consumption of n-3 PUFAs or a low plasma DHA concentration is correlated with a number of brain diseases and with cognitive and behavioral defects in development and aging 9–11, and that dietary n-3 PUFA supplementation may be beneficial in some of these conditions 6, 12.

Effects on the brain of minor n-3 PUFA dietary deprivation associated with small declines in plasma DHA concentrations of the order found in the clinic have rarely been studied in animal models. Additionally, controversy exists about which dietary PUFA compositions are optimal for human brain function 6, 12–16. The liver’s in vivo capacity to convert α-LNA or eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, 20:5n-3) to DHA, or LA to AA, has not be quantified in animals or in humans, although changes in this capacity with development, aging or disease likely impact brain PUFA metabolism 17–21.

Several important questions regarding the relation of brain PUFA metabolism to diet and liver PUFA metabolism have recently been partially resolved, and we shall discuss them in this brief review. These are: (1) What are the rates of brain consumption of AA and DHA in rats and humans? (2) How does brain DHA metabolism depend on dietary n-3 PUFA composition and the liver’s ability to convert α-LNA to DHA? (3) How do brain lipid enzymes and trophic factors respond to dietary n-3 PUFA deprivation?

We have developed kinetic methods and models to address these questions in the intact awake organism. The methods include brain imaging with quantitative autoradiography or positron emission tomography (PET), intravenous injection of radiolabeled PUFAs to examine incorporation, turnover and synthesis rates of PUFAs in brain or liver, enzyme assays to evaluate activities of lipid metabolizing enzymes, and molecular techniques to examine transcriptional regulation and protein levels of these enzymes.

2. Methods and Models

AA and DHA are found in high concentrations in the stereospecifically numbered (sn)-2 position of brain membrane phospholipids, from where they can be released by selective phospholipase A2 (PLA2) enzymes 1, 22–27. After release, most of the unesterified AA or DHA will be rapidly reincorporated into an unesterified sn-2 position in a lysophospholipid via the acyl-CoA pool, through serial actions of an acyl-CoA synthetase and acyltransferase with the consumption of two molecules of ATP 28. A small fraction, however, will be lost through any of a number of catabolic pathways, including β-oxidation and conversion to eicosanoids or docosanoids by cyclooxygenases (COXs), lipoxygenases, or cytochrome P450 29–33.

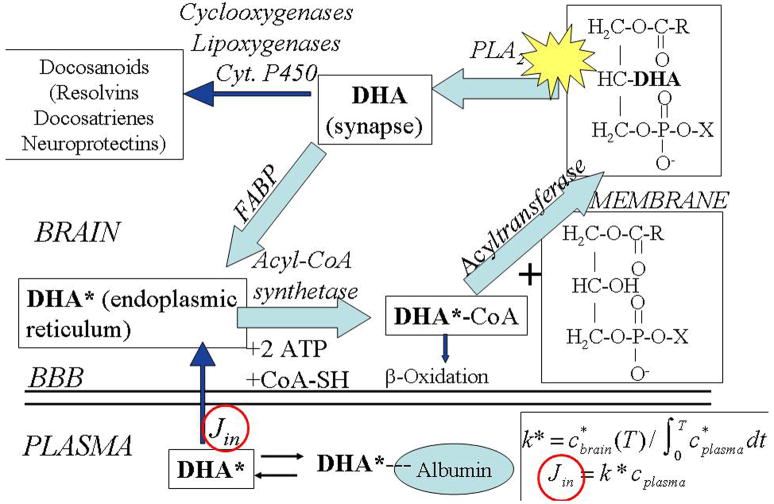

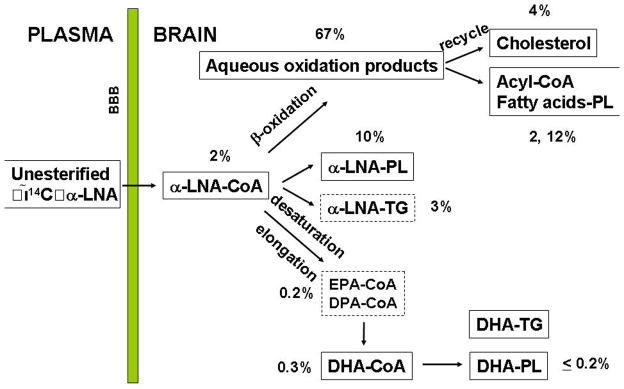

Figure 1 illustrates major pathways that DHA can take after it is released from phospholipids by activation of PLA2; a similar figure exists for the AA cascade 3, 27, 34. The figure identifies two ways in which brain turnover of DHA (or AA) can be considered 35. The first is deacylation followed by rapid reacylation into phospholipid 30, 36, a process which is associated for both DHA and AA with neurotransmission via receptors that are coupled to PLA2 1, 2, 37. The second relates to the net loss of DHA from brain, followed by its replacement by plasma unesterified DHA. It turns out that the rate of replacement of AA or DHA, Jin in Figure 1 (entry arrow) exactly equals the rate of loss (sum of small arrows to β-oxidation and docosanoids and other catabolic pathways not shown), because the circulating precursors LA and α-LNA, do not contribute significantly (< 1% converted) to brain AA or DHA, respectively (e.g. Figure 2), and neither AA nor DHA can be synthesized de novo in vertebrate tissue 7, 38, 39. Replacement occurs independently of changes in cerebral blood flow 31, 40, 41.

Figure 1. Model of brain docosahexaenoic acid cascade at the synapse.

Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), esterified at the sn-2 position of a phospholipid, is liberated by activation (star) of PLA2 at the synapse, secondary to neuroreceptor activation 1, 37. A fraction of the unesterified DHA is converted to docosanoids by COX, lipoxygenase or P450 enzymes, whereas the remainder is transported by a fatty acid binding protein (FABP) to the endoplasmic reticulum. From there, DHA is activated to docosahexaenoyl-CoA by an acyl-CoA synthetase with the consumption of two ATPs, then esterified into an available lysophospholipid by an acyltransferase. Unesterified DHA also can be lost by β-oxidation in mitochondria or peroxisomes, or by other pathways (not shown). The endoplasmic reticulum compartment is in very rapid equilibrium with unesterified plasma DHA that has been dissociated from circulating albumin, whereas the synaptic compartment does not exchange with plasma DHA 70. This allows injecting radiolabeled DHA* intravenously and determining the incorporation rates Jin (circled), a critical parameter, of unesterified unlabeled plasma DHA into individual membrane phospholipids, as well as DHA turnover rates and half-lives in those phospholipids. Adapted from 35.

Figure 2. Fractional distribution of [1-14C]α-LNA in different lipid compartments of rat brain, following 5 min of intravenous its intravenous infusion in unanesthetized rats on a high 2.3% DHA containing diet.

Less than of the tracer has been elongated to EPA or DHA in the acyl-CoA, phospholipid(PL) or triacylglycerol (TG) pools. From 38.

3. Results and modeling

Equations for incorporation rates and half-lives

We can quantify Jin for AA or DHA by infusing intravenously albumin-bound radiolabeled PUFA in an organism, then imaging regional brain radioactivity in frozen brain, or determining radioactivity in individual stable lipids (phospholipids, triacylglycerols and cholesteryl esters) in high-energy microwaved brain 1, 37.

For imaging, we first determine an incorporation coefficient k* (ml/sec/g brain) using quantitative autoradiography or PET following the intravenous injection of the labeled AA or DHA, by dividing regional brain radioactivity by the integrated plasma radioactivity (input function),

| (Eq. 1) |

where t is time after beginning tracer infusion, nCi/g is brain radioactivity at time T of sampling (often 5 min), and nCi/ml is plasma radioactivity. Then, Jin nmol/sec/g brain is calculated by multiplying k* by the unlabeled unesterified plasma AA or DHA concentration, cplasma nmol/ml,

| (Eq. 2) |

The half-life for net loss of the PUFA from brain is given as follows, where the unlabeled PUFA concentration in net brain stable lipid (mainly phospholipid) equals cbrain nmol/g,

| (Eq. 3) |

AA and DHA incorporation rates and half-lives in rat brain

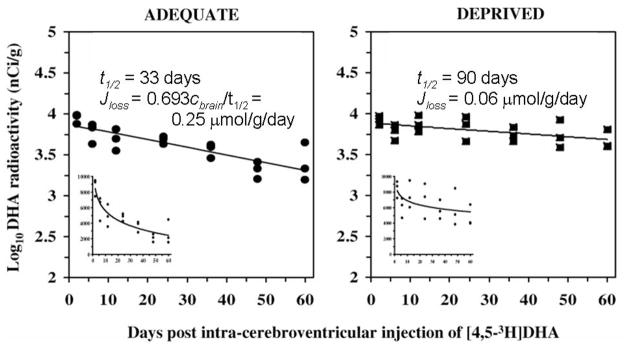

Measured net brain incorporation rates Jin, which were determined following intravenous tracer injection in unanesthetized rats fed standard rat chow (NIH-31), equaled 24 – 48 nmol/g/s × 10−4 (0.21–0.42 μmol/g/day) for DHA and 22.0 nmol/g/s × 10−4 (0.19 μmol/g/day) for AA 42–45. As illustrated in Figure 3 (left), the DHA incorporation rate determined this way approximates the DHA rate of loss from rat brain phospholipid, 0.25 μmol/day, which was determined using Eq. 3 from the loss half-life following intracerebral injection of [4,5-3H]DHA 46. This approximation confirms that Jin as calculated following intravenous tracer AA or DHA infusion represents the rate of metabolic loss within brain, and that the circulating precursors LA or α-LNA, respectively, or the esterified PUFAs with circulating lipoproteins, do not contribute significantly to the measured Jin.

Figure 3. Fifteen weeks of dietary n-3 PUFA deprivation in post-weaning rats prolongs half-life and slows DHA loss in rat brain phospholipid.

[4,5-3H]DHA was injected into the brain radioactivity due to it was followed in individual phospholipids for 60 days, from which half-lives t1/2 were calculated (Eq. Jloss was calculated from half-life as illustrated in figure (Eq. 3). From Demar et al. 46.

Half-lives for net DHA or AA loss from rat brain (Eq. 3) are the order of weeks to months (e.g. Figure 3, left side) 35, 46. They are much longer than the half-lives due to recycling (deacylation-reacylation) (Figure 1) 30, 36, which can be minutes to hours 35, 47. Recycling is promoted by PLA2-mediated release of AA or DHA from membrane phospholipid, initiated by neurotransmission (see above) 1–3, 22, 37.

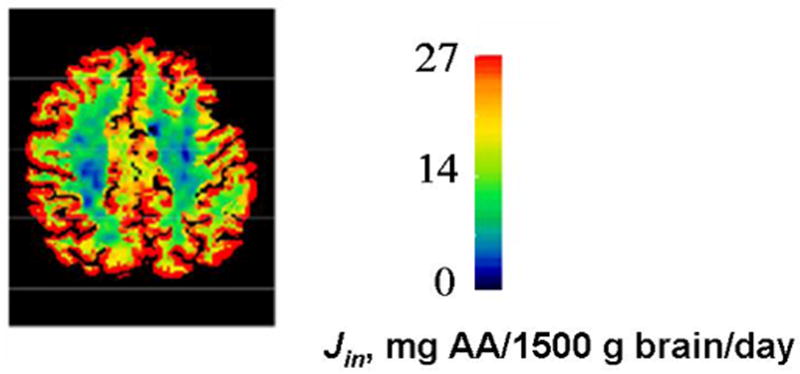

PUFA incorporation and consumption rates of the human brain

Recognizing that Jin for AA or DHA represents the rate of brain metabolic consumption, we determined Jin for both PUFAs in the human brain using PET and the positron emitting tracers, [1-11C]AA and [1-11C]DHA, respectively 48–51 (Umhau et al., unpublished results). Whole-brain Jin in healthy adults equaled 17.8 mg/day per 1500 g brain for AA (Figure 4) 49 and 4.6 mg/day per 1500 g brain for DHA (Umhau et al., unpublished results). Jin for AA did not decline with age in healthy subjects 49.

Figure 4. Horizontal section of regional incorporation rates of plasma unesterified arachidonic acid into human brain, after correction for partial voluming.

. Rates are given in terms of color-coding. The global rate, obtained by integrating regional rates for whole brain, equaled 17.8 mg/1500 g brain/day. From 49.

Dividing Jin for DHA by the estimated human brain DHA content, based on a DHA concentration in gray matter phospholipid of 11.2 μmol/g [Ma et al., unpublished], gives an estimated whole brain DHA concentration of 5.13 g, in agreement with a prior estimate 52, and a DHA half-life of 773 days (2.1 years) by Eq. 3. For AA, whose gray matter concentration is 8.27 μmol/g [Ma et al., unpublished], we calculate a whole brain AA concentration of 3.78 grams and a brain half-life of 147 days.

While a half-life of 2.1 years for DHA seems at first very long, inserting this value in the following equation,

| (Eq. 4) |

where cbrain at the initial time 0 and at time t thereafter are designated, shows that brain DHA would fall by 5% within only 41 days after the disappearance of DHA from plasma. We don’t as yet know how sensitive human brain function is to a 5% drop in its DHA content, but if it is, DHA deprivation for only a few months may lead to functional brain changes.

The dietary intakes of n-3 PUFAs for maintaining optimal human brain PUFA metabolism are not agreed on, but now might be estimated by relating intake to PET-determined brain DHA incorporation (consumption) rates. Different committees have recommended eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, 20:5n-3) + DHA intakes of 0.11–0.16 g/day 53, 0.2 g/day 14, 0.65 g/day 15, and 1.6 g/day 16. Another committee recommended that adult men and women should consume 1.6 g/day and 1.1 g/day, respectively, of α-LNA, plus an additional 10% of EPA + DHA 53. Our PET-determined Jin for DHA, 4.6 mg/day, equals 2.5–5% of the estimated average daily dietary intake of EPA + DHA in the United States, 100–200 mg/day 13.

Brain and liver conversion of circulating α-LNA to DHA with different diets

Controversy exists about the ability of the brain and liver to convert α-LNA to DHA so as to supplement the brain’s DHA, when DHA is absent from the diet or when dietary n-3 PUFAs are low. We evaluated this issue in unanesthetized rats by determining brain consumption rates of DHA under different dietary conditions and by quantifying coefficients and rates of conversion and esterification of circulating α-LNA to DHA in brain and liver 20, 21, 38, 39, 54.

We studied rats that had been fed, for 15 weeks post-weaning (starting at 21 days of age), one of three diets (Table 1, row 1): (1) a high DHA containing diet (DHA 2.3% of total fatty acids, 5.1% α-LNA, 4% fat); (2) a DHA-free diet containing 4.6% α-LNA (of total fatty acids), 10% fat; or (3) a DHA-free diet containing 0.2% α-LNA, 10% fat. We term the latter two diets n-3 PUFA “adequate” and “deficient,” respectively, following the convention of Bourre 8. The rats fed the “deficient” compared with “adequate” diet had increased scores on behavioral measures of depression and aggression 55.

Table 1. Plasma and brain parameters in unanesthetized rats fed different diets for 15 weeks.

Row 1: dietary composition. Row 2: unesterified plasma concentration of α-LNA and DHA (in brackets). Row 3: unesterified plasma concentrations of AA and DPAn-6 (in brackets); Row 4: Brain phospholipids DHA concentration. Row 5: AA and DPAn-6 (in brackets) concentrations in brain phospholipids. Row 6: DHA incorporation coefficient calculated by Eq. 1. Row 7: brain DHA incorporation rate calculated by Eq. 2. Row 8: whole brain (1.5 g) DHA incorporation (consumption) rate, in units of μmol/day.

| Diet During 15 Weeks Post-weaning | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Parameter | Units | High DHA diet (5.1% α-LNA, 2.3% DHA, 4% fat) | High α-LNA diet (4.6% α-LNA, no DHA, 10% fat) | n-3 PUFA inadequate diet (0.2% α-LNA, no DHA, 10% fat) |

| 2 | cplasma(α-LNA) [cplasma(DHA)] | nmol/ml | 41 ± 13# a [26 ± 12] a | 27 ± 6# [6.5 ± 2.6] b | 1.0 ± 0.45* [0.23 ± 0.10]* b |

| 3 | cplasma(AA) [cplasma(DPAn-6] | nmol/ml | 22.5 ± 5.6 [2.3 ± 1.2] c | 25 ± 4.8 [ND] b | 34 ± 5.9 [8.7 ± 1.1]* b |

| 4 | DHA concentration in brain phospholipid, cbrain | μmol/g | 17.6 ± 2.8 a 13.8 ± 4.9 c |

12.0 ± 2.4 d | 7.6 ± 1.5*d |

| 5 | Concentrations of AA and [DPAn-6] in brain phospholipid | μmol/g | 11.1 ± 2.9 c [0.1 ± 0.04] c | 9.4 ± 1.1 d [0.25 ± 0.06] d | 9.8 ± 1.5 d [4.4 ± 1.8]* d |

| 6 | DHA incorporation coefficients, k* | ml/s/g × 10−4 | 2.2 ± 0.2 f | 1.99 ± 0.3 e | 2.83 ± 0.6* e |

| 7 | Rate DHA incorporation, Jin # | nmol/s/g × 10−4 | 17.4 ± 2.0 f | 22.0 ± 5.0 e | 0.23 ± 0.05* e |

| 8 | Daily rate DHA consumption by whole (1.5 g) brain | μmol/day | 0.23 f | 0.29 e | 0.003 e |

As illustrated in Table 1, the unesterified plasma α-LNA concentration in rats fed the n-3 PUFA “adequate” diet was 36% less than in rats fed the DHA-containing diet, but 27 times higher than in rats fed the “deficient” diet (row 2). Unesterified plasma AA did not differ markedly among rats on the three diets, whereas the plasma concentration of the AA elongation product, docosapentaenoic acid (DPAn-6, 22:5n-6), while low in rats fed the high DHA or n-3 PUFA “adequate” diet, rose to 8.7 nmol/ml in rats fed the “deficient” diet (row 3, Table 1).

The DHA concentration in brain phospholipid (Table 1, row 4) was lower in rats fed the “adequate” than high DHA diet, but was reduced by an additional 4.4 μmol/g in rats fed the “deficient” diet. While AA concentrations in brain phospholipid were about the same in rats fed each of the three diets (Table 1, row 5), brain DPAn-6 was elevated by 4.2 μmol/g in rats fed the “deficient” diet, largely compensating for the reduced DHA concentration.

Brain DHA incorporation coefficients k* (Eq. 1) did not vary markedly among the three dietary groups (Table 1, row 6), whereas the rate of DHA incorporation into brain, Jin, thus its rate of loss, was reduced in rats fed the deficient diet (Table 1, rows 7 and 8), reflecting the low plasma DHA with this diet (Eq. 2). Reduced values of Jin for DHA in rats fed the “deficient” diet corresponded to a 3-fold prolongation of DHA half-life in brain phospholipid (Figure 3, right) 46.

For evaluating brain and liver conversion rates Jin,i(α–LNA→DHA) of circulating α-LNA to DHA within individual “stable” lipids i (phospholipid, triacylglycerol, cholesteryl ester) 20, 21, 38, 39, 54, we first calculated conversion coefficients for each organ following 5 minutes of intravenous infusion of [1-14C]α-LNA. For example, the conversion coefficient for the liver, in units of ml/sec/g liver, equals,

| (Eq. 5) |

whereas the conversion rate in units of nmol/sec/g liver equals,

| (Eq. 6) |

where nCi/g is DHA radioactivity in “stable” lipid i, nCi/ml is plasma radioactivity of unesterified α-LNA, c plasma(α–LNA) nmol/ml is the plasma concentration of unesterified unlabeled α-LNA. Equivalent equations can be written for brain.

The rate of secretion by liver of the DHA assuming that the amount of DHA synthesized from total circulating (unesterified and esterified) α-LNA by the liver, calculated after 5 min of intravenous [1-14C]α-LNA infusion, would eventually be secreted into blood within lipoproteins. This assumption remains to be tested. We calculated the secretion rate by summing equations 5 for i = phospholipid, triacylglycerol and cholesteryl ester, and then dividing by a “dilution” factor λα–LNA–CoA 21, 31, 54. This factor equals the steady-state ratio of specific activity of liver α-LNA-CoA to specific activity of plasma unesterified α-LNA, during infusion of [1-14C]α-LNA,

| (Eq. 7) |

Taking λα–LNA–CoA into account allows us to estimate the rate of liver DHA secretion from the rate of incorporation only of unesterified circulating α-LNA 31.

We estimated the abilities of the brain and liver to synthesize DHA from circulating α-LNA in unanesthetized rats fed each of the three diets noted in Table 1. As illustrated in row 2 of Table 2, brain conversion coefficients (Eq. 5) of unesterified plasma α-LNA to DHA into “stable” liver lipids i = phospholipid (PL) and triacylglycerol (TG) did not vary markedly among rats fed the three diets. Thus the net conversion rate was related directly by Eq. 6 to the unesterified plasma concentration of α-LNA (row 2 of Table 1). The calculated net rate of DHA synthesis by the brain (row 4 of Table 2) did not differ between animals on the high DHA diet and the “adequate” diet containing 4.6% α-LNA but no DHA, but was reduced as expected (Eq. 6) in rats fed the “deficient” diet because of the very low plasma α-LNA concentration (row 2, Table 1). In any case, comparing synthesis rates in brain with rates of brain DHA consumption (row 8 of Table 1) shows that the brain’s capacity to synthesize DHA is a small fraction of its daily DHA consumption requirement and thus, in the absence of dietary DHA, insufficient to maintain DHA homeostasis.

Table 2. Calculated brain and liver conversion parameters in unanesthetized rats fed different diets.

Row 1: dietary composition. Row 2: conversion coefficients of plasma α-LNA to DHA in brain, calculated by Eq. 5. Row 3: net conversion rate of α-LNA to DHA, in units of nmol/s/g × 10−4. Row 4: net conversion rate for 1.5 g brain, in units of μmol/day. Row 5: conversion coefficients of plasma α-LNA to DHA in brain, calculated by Eq. 5. Row 6: net liver conversion rate of α-LNA to DHA, in units of nmol/s/g × 10−4, calculated by Eq. 6. Row 7: net DHA secretion rate for 11.5 g liver, in units of μmol/day., calculated by Eq. 7.

| Diet During 15 Weeks Post-weaning | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Parameter | Units | High DHA diet (5.1% α-LNA, 2.3% DHA, 4% fat) | High α-LNA diet (4.6% α-LNA, no DHA, 10% fat) | n-3 PUFA inadequate diet (0.2% α-LNA, no DHA, 10% fat) |

| BRAIN | |||||

| 2 | Conversion coefficients brain, (i = PL, TG) | ml/s/g × 10−4 | 0.0055, 0.00040 | 0.0063, 0.00077 | 0.0051, 0.00089 |

| 3 | Net DHA conversion rate per g brain, Jin,i(α–LNA→DHA)i | nmol/s/g × 10−4 | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.007 |

| 4 | Net daily DHA formation rate from α-LNA by 1.5 g brain## | μmol/day | 0.002 | 0.0016 | 0.0000006 |

| LIVER | |||||

| 5 | Conversion coefficients liver, (i = PL, TG), | ml/s/g × 10−4 | 0.03, 0.1 | 0.053, 0.219 | 0.44, 1.45 |

| 6 | Net DHA conversion rate per g liver Jin,i(α–LNA→DHA)i | nmol/s/g × 10−4 | 6.6 | 7.45 | 1.99 |

| 7 | Net daily DHA secretion rate, per 11.5 g rat liver# | μmol/day | 1.57 | 2.19 | 0.82 |

Comparison of rows 5 and 2 of Table 2 shows that liver conversion coefficients of α-LNA to DHA are many fold their respective brain conversion coefficients. They were increased about 2-times in rats on the “adequate” diet compared with the DHA-containing diet, and a further 7-times in rats fed the “deficient” diet. The increases have since been shown to correspond to increased liver activities of the Δ5 and Δ6 desaturases and elongases 2 and 5 that mediate conversion of α-LNA to DHA and of LA to AA 56. Net liver conversion rates (row 6, table 2) were about the same in rats on the high DHA and n-3 PUFA “adequate” diets, but were reduced in rats fed the “deficient” diet due to the low plasma α-LNA concentration (Eq. 7). The liver’s net DHA secretion rate in rats fed the n-3 PUFA “adequate” diet (row 7, Table 2) was many fold greater than the brain’s DHA synthesis rate (row 4, Table 2). Furthermore, the liver’s secretion rate was about 10-fold the brain’s DHA consumption rate (row 8, Table 1), clearly sufficient to supply the brain’s DHA.

In summary, in rats fed an n-3 PUFA “adequate” diet containing only 4.6% α-LNA, brain DHA is maintained by the DHA formed and secreted from circulating α-LNA by the liver, as the brain’s capacity for DHA synthesis is relatively insignificant. When dietary α-LNA is reduced, the liver increases its coefficients for DHA synthesis by upregulating activities of relevant desaturases and elongases.

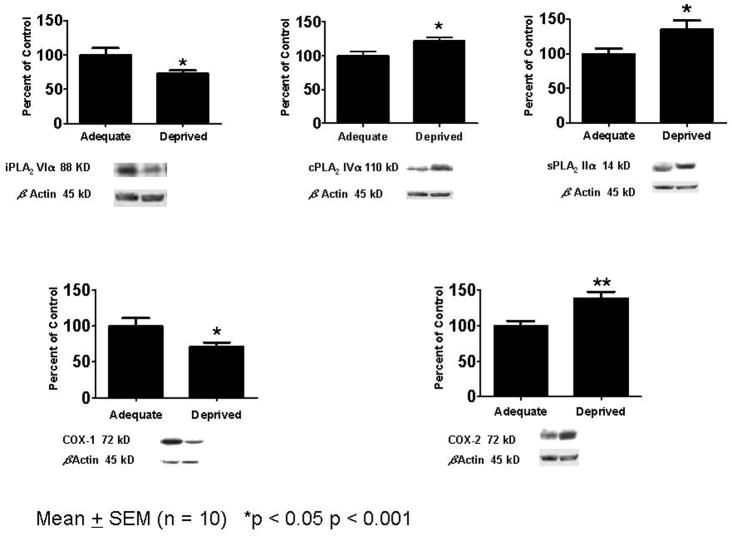

Enzymes of the brain AA and DHA cascades in relation to diet

Figure 3 illustrates that the half-life of DHA in brain was prolonged 3-fold in rats fed the n-3 PUFA “deficient” compared with the “adequate” diet 46. This prolongation corresponds to reduced brain of mRNA, protein and activity levels of the DHA-selective Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2 (iPLA2) 25 and of COX-1 57, as illustrated in Figure 5. Other evidence indicates that these two enzymes are functionally coupled in different tissues 58.

Figure 5. Fifteen weeks of n-3 PUFA dietary deprivation, compared with an n-3 PUFA “adequate” diet, decreases rat frontal cortex iPLA2 and COX-1 protein but increases sPLA2, cPLA2 and COX-2 protein.

From 57.

Also illustrated in Figure 5, the 15-week n-3 PUFA “deficient” diet led to increases in brain mRNA, protein and activity levels of AA-selective cPLA2, secretory sPLA2 and COX-2 57, enzymes that are involved directly in brain AA metabolism 26, 58, 59. These changes, in the context of an increased brain DPAn-6 concentration (Table 1, row 3), imply that the “deficient” diet upregulated brain n-6 PUFA metabolism, and thus that dietary n-3 PUFA supplementation may have an opposite effect.

Excess AA metabolism can contribute to neuronal damage in experimental ischemia, glutamate excitotoxicity, neuroinflammation, and cerebral trauma 45, 60–64. This, among other factors, may explain why an n-3 PUFA dietary deficiency might increase brain vulnerability to these insults. In this regard, a low dietary n-3 PUFA content has been suggested to increase brain vulnerability in a number of human diseases, including Alzheimer disease and bipolar disorder, in which neuroinflammation and excitotoxicity play a role 9, 10, 65, 66.

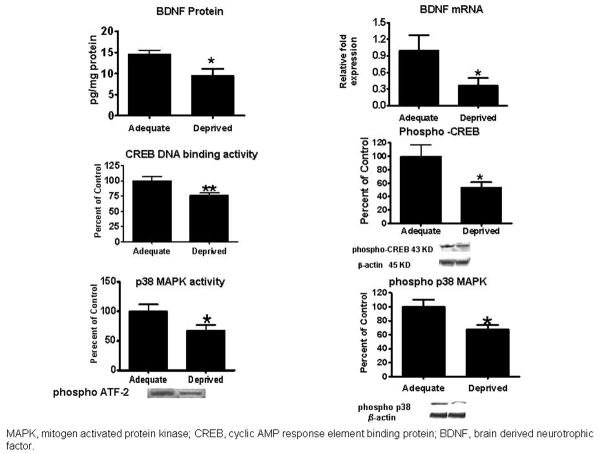

BDNF and CREB

Another way in which dietary n-3 PUFAs may be neuroprotective is by upregulating brain trophic factors. For example, brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) promotes neuronal survival, plasticity, differentiation and growth 67. Transcription of the BDNF gene is regulated by the cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB), following CREB’s phosphorylation by protein kinases including p38 mitogen activated protein (MAP) kinase 68. In rats fed the n-3 PUFA “deficient” compared with “adequate” diet, brain mRNA and protein levels of BDNF, CREB DNA binding activity, the phosphorylated CREB protein level and p38 MAP kinase activity were reduced significantly (Figure 6) 68. Another important role of CREB is to modulate memory performance 69.

Figure 6. Fifteen weeks of n-3 PUFA dietary deprivation, compared with an n-3 PUFA adequate diet, downregulates rat frontal cortex expression of p38 MAP kinase activity and phospho p38 MAP kinase protein, CREB DNA binding activity and phospho-CREB protein, and BDNF protein and mRNA. From 68.

In summary, rats subjected to our 15-week dietary n-3 PUFA deprivation have a reduced brain DHA concentration and a prolonged DHA half-life, accompanied by reduced activities of presumably DHA-selective iPLA2 and COX-1; an increased brain DPAn-6 concentration accompanied by increased activities of AA-selective cPLA2, sPLA2 and COX-2; and reduced expression of BDNF that corresponds to CREB DNA binding activity and p38 MAP-kinase activity.

3. Conclusions

In this brief review, we have shown how radiotracer methods and kinetic models can be used to determine quantitative aspects of brain and/or liver metabolism of nutritionally essential PUFAs in the intact organism. We have presented experimentally determined regional and global brain AA and DHA consumption rates in humans, and in brain and liver of unanesthetized rats in relation to dietary PUFA composition. In the absence of dietary DHA, we conclude that a normal brain DHA content can be maintained by liver conversion of α-LNA to circulating DHA, provided sufficient α-LNA is in the diet, as the brain’s capacity for conversion is quantitatively insignificant. Liver but not brain conversion coefficients are increased by further α-LNA deprivation, in relation to increased expression of liver elongases and desaturases. Brain DHA depletion caused by 15 weeks of dietary n-3 PUFA deprivation in rats is associated with slowed DHA loss from brain and reduced expression of DHA-metabolizing enzymes, tending to conserve brain DHA. At the same time, increased brain expression of AA-metabolizing enzymes and a high DPAn-6 concentration, and reduced brain BDNF, phospho-CREB and p38 MAP kinase activity levels, suggest upregulated brain n-6 PUFA metabolism. Some of these changes are consistent with neuroprotective effects of n-3 PUFAs.

Now that appropriate quantitative techniques are available for studying the relations among brain and liver PUFA metabolism and diet animal and humans, future studies using these techniques might address a number of additional relevant questions: (1) To what extent does the liver convert EPA to DHA under different dietary conditions? (2) What are the effects of graded n-3 PUFA dietary deprivation on the markers and kinetics of brain metabolism and function that we have presented in this paper? (3) What are the effects of dietary n-6 PUFA deprivation on these markers? (4) How do liver conversion rates of α-LNA and EPA to secreted DHA vary with age and liver disease in rats? (5) In humans, how do brain AA and DHA consumption rates change with aging or disease, and how might human diets be tailored to maintain normal consumption rates with these variable conditions?

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Program of the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA. We thank Dr. Richard Bazinet for his helpful comments

Abbreviations

- AA

arachidonic acid

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- DHA

docosahexaenoic acid

- LA

linoleic acid

- PET

positron emission tomography

- PUFA

polyunsaturated fatty acid

- PLA2

phospholipase A2

- α-LNA

α-linolenic acid

- BDNF

brain derived growth factor

- CREB

cAMP response element-binding protein

- EPA

eicosapentaenoic acid

- DPA

docosapentaenoic acid

- MAP

mitogen activated protein

- sn

stereospecifically numbered

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

September 11, 2007 For Prostaglandins other Lipid Mediators, Quebec Conference

References

- 1.DeGeorge JJ, Nariai T, Yamazaki S, Williams WM, Rapoport SI. Arecoline-stimulated brain incorporation of intravenously administered fatty acids in unanesthetized rats. J Neurochem. 1991;56(1):352–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb02603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Axelrod J, Burch RM, Jelsema CL. Receptor-mediated activation of phospholipase A2 via GTP-binding proteins: arachidonic acid and its metabolites as second messengers. Trends Neurosci. 1988;11(3):117–23. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(88)90157-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rapoport SI. In vivo fatty acid incorporation into brain phospholipids in relation to plasma availability, signal transduction and membrane remodeling. J Mol Neurosci. 2001;16:243–61. doi: 10.1385/JMN:16:2-3:243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Contreras MA, Rapoport SI. Recent studies on interactions between n-3 and n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids in brain and other tissues. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2002;13:267–72. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200206000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Youdim KA, Martin A, Joseph JA. Essential fatty acids and the brain: possible health implications. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2000;18(4–5):383–99. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(00)00013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Innis SM. The role of dietary n-6 and n-3 fatty acids in the developing brain. Dev Neurosci. 2000;22(5–6):474–80. doi: 10.1159/000017478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holman RT. Control of polyunsaturated acids in tissue lipids. J Am Coll Nutr. 1986;5(2):183–211. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1986.10720125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bourre JM, Francois M, Youyou A, et al. The effects of dietary alpha-linolenic acid on the composition of nerve membranes, enzymatic activity, amplitude of electrophysiological parameters, resistance to poisons and performance of learning tasks in rats. J Nutr. 1989;119(12):1880–92. doi: 10.1093/jn/119.12.1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conquer JA, Tierney MC, Zecevic J, Bettger WJ, Fisher RH. Fatty acid analysis of blood plasma of patients with Alzheimer’s disease, other types of dementia, and cognitive impairment. Lipids. 2000;35(12):1305–12. doi: 10.1007/s11745-000-0646-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Noaghiul S, Hibbeln JR. Cross-national comparisons of seafood consumption and rates of bipolar disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(12):2222–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.12.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pawlosky RJ, Salem N., Jr Alcohol consumption in rhesus monkeys depletes tissues of polyunsaturated fatty acids and alters essential fatty acid metabolism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23:311–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stoll AL, Severus WE, Freeman MP, et al. Omega 3 fatty acids in bipolar disorder: A preliminary double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:407–12. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.5.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kris-Etherton PM, Taylor DS, Yu-Poth S, et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acids in the food chain in the United States. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71(1 Suppl):179S–88S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.1.179S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.British Nutrition Foundation. Unsaturated fatty acids nutritional and physiological significance: the report of the British Nutrition Foundation’s task force. Chapman and Hall; New York: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simopoulos AP. Commentary on the workshop statement. Essentiality of and recommended dietary intakes for Omega-6 and Omega-3 fatty acids. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2000;63(3):123–4. doi: 10.1054/plef.2000.0177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scientific Review Committee. Minister of National Health and Welfare. Canadian Government Publishing Centre; Ottawa, Canada: 1990. p. 208. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bourre JM, Piciotti M. Delta-6 desaturation of alpha-linolenic acid in brain and liver during development and aging in the mouse. Neurosci Lett. 1992;141(1):65–8. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90335-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burke PA, Ling PR, Forse RA, Lewis DW, Jenkins R, Bistrian BR. Sites of conditional essential fatty acid deficiency in end stage liver disease. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2001;25(4):188–93. doi: 10.1177/0148607101025004188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scott BL, Bazan NG. Membrane docosahexaenoate is supplied to the developing brain and retina by the liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86(8):2903–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Igarashi M, Demar JC, Jr, Ma K, Chang L, Bell JM, Rapoport SI. Rate of synthesis of docosahexaenoic acid from alpha-linolenic acid by rat brain is not altered by dietary N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid deprivation. J Lipid Res. 2007 doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600549-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Igarashi M, DeMar JC, Jr, Ma K, Chang L, Bell JM, Rapoport SI. Upregulated liver conversion of alpha-linolenic acid to docosahexaenoic acid in rats on a 15 week n-3 PUFA-deficient diet. J Lipid Res. 2007;48(1):152–64. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600396-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones CR, Arai T, Bell JM, Rapoport SI. Preferential in vivo incorporation of [3H]arachidonic acid from blood in rat brain synaptosomal fractions before and after cholinergic stimulation. J Neurochem. 1996;67(2):822–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67020822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bayon Y, Hernandez M, Alonso A, et al. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 is coupled to muscarinic receptors in the human astrocytoma cell line 1321N1: characterization of the transducing mechanism. Biochem J. 1997;323:281–7. doi: 10.1042/bj3230281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clark JD, Lin LL, Kriz RW, et al. A novel arachidonic acid-selective cytosolic PLA2 contains a Ca(2+)-dependent translocation domain with homology to PKC and GAP. Cell. 1991;65(6):1043–51. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90556-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strokin M, Sergeeva M, Reiser G. Prostaglandin synthesis in rat brain astrocytes is under the control of the n-3 docosahexaenoic acid, released by group VIB calcium-independent phospholipase A(2) J Neurochem. 2007 doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dennis EA. Diversity of group types, regulation, and function of phospholipase A2. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:13057–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rapoport SI. In vivo approaches to quantifying and imaging brain arachidonic and docosahexaenoic acid metabolism. J Pediatr. 2003;143(4 Suppl):S26–34. doi: 10.1067/s0022-3476(03)00399-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Purdon AD, Rapoport SI. In: Neural Energy Utilization: Handbook of Neurochemistry and Molecular Biology. Gibson G, Dienel G, editors. Springer; New York: 2007. pp. 401–27. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horrocks LA, Farooqui AA. Docosahexaenoic acid in the diet: its importance in maintenance and restoration of neural membrane function. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2004;70(4):361–72. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2003.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun GY, MacQuarrie RA. Deacylation-reacylation of arachidonoyl groups in cerebral phospholipids. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1989;559:37–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1989.tb22597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robinson PJ, Noronha J, DeGeorge JJ, Freed LM, Nariai T, Rapoport SI. A quantitative method for measuring regional in vivo fatty-acid incorporation into and turnover within brain phospholipids: Review and critical analysis. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1992;17:187–214. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(92)90016-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fitzpatrick FA, Soberman R. Regulated formation of eicosanoids. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:1347–51. doi: 10.1172/JCI13241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sugiura T, Kondo S, Sukagawa A, et al. Transacylase-mediated and phosphodiesterase-mediated synthesis of N-arachidonoylethanolamine, an endogenous cannabinoid-receptor ligand, in rat brain microsomes. Comparison with synthesis from free arachidonic acid and ethanolamine. Eur J Biochem. 1996;240(1):53–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0053h.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shimizu T, Wolfe LS. Arachidonic acid cascade and signal transduction. J Neurochem. 1990;55(1):1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb08813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rapoport SI, Chang MC, Spector AA. Delivery and turnover of plasma-derived essential PUFAs in mammalian brain. J Lipid Res. 2001;42(5):678–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lands WEM, Crawford CG. In: The Enzymes of Biological Membranes. Martonosi A, editor. Plenum; New York: 1976. pp. 3–85. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jones CR, Arai T, Rapoport SI. Evidence for the involvement of docosahexaenoic acid in cholinergic stimulated signal transduction at the synapse. Neurochem Res. 1997;22:663–70. doi: 10.1023/a:1027341707837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Demar JC, Jr, Ma K, Chang L, Bell JM, Rapoport SI. alpha-Linolenic acid does not contribute appreciably to docosahexaenoic acid within brain phospholipids of adult rats fed a diet enriched in docosahexaenoic acid. J Neurochem. 2005;94(4):1063–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.DeMar JC, Jr, Lee HJ, Ma K, et al. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1761(9):1050–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Purdon D, Arai T, Rapoport S. No evidence for direct incorporation of esterified palmitic acid from plasma into brain lipids of awake adult rat. J Lipid Res. 1997;38(3):526–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang MC, Arai T, Freed LM, et al. Brain incorporation of [1-11C]-arachidonate in normocapnic and hypercapnic monkeys, measured with positron emission tomography. Brain Res. 1997;755:74–83. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00088-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Contreras MA, Greiner RS, Chang MC, Myers CS, Salem N, Jr, Rapoport SI. Nutritional deprivation of alpha-linolenic acid decreases but does not abolish turnover and availability of unacylated docosahexaenoic acid and docosahexaenoyl-CoA in rat brain. J Neurochem. 2000;75(6):2392–400. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0752392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Contreras MA, Chang MC, Rosenberger TA, et al. Chronic nutritional deprivation of n-3 alpha-linolenic acid does not affect n-6 arachidonic acid recycling within brain phospholipids of awake rats. J Neurochem. 2001;79(5):1090–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chang MC, Grange E, Rabin O, Bell JM, Allen DD, Rapoport SI. Lithium decreases turnover of arachidonate in several brain phospholipids. Neurosci Lett. 220:171–4. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(96)13264-x. Erratum in: Neurosci Lett 1997 31:222–141, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Basselin M, Villacreses NE, Lee HJ, Bell JM, Rapoport SI. Chronic lithium administration attenuates up-regulated brain arachidonic acid metabolism in a rat model of neuroinflammation. J Neurochem. 2007 doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.DeMar JC, Jr, Ma K, Bell JM, Rapoport SI. Half-lives of docosahexaenoic acid in rat brain phospholipids are prolonged by 15 weeks of nutritional deprivation of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. J Neurochem. 2004;91(5):1125–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shetty HU, Smith QR, Washizaki K, Rapoport SI, Purdon AD. Identification of two molecular species of rat brain phosphatidylcholine that rapidly incorporate and turn over arachidonic acid in vivo. J Neurochem. 1996;67:1702–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67041702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Giovacchini G, Chang MC, Channing MA, et al. Brain incorporation of [11C]arachidonic acid in young healthy humans measured with positron emission tomography. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22(12):1453–62. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000033209.60867.7A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Giovacchini G, Lerner A, Toczek MT, et al. Brain incorporation of 11C-arachidonic acid, blood volume, and blood flow in healthy aging: a study with partial-volume correction. J Nucl Med. 2004;45(9):1471–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Esposito G, Giovacchini G, Der M, et al. Imaging signal transduction via arachidonic acid in the human brain during visual stimulation, by means of positron emission tomography. Neuroimage. 2007;34(4):1342–51. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Channing MA, Simpson N. Radiosynthesis of 1-[11C]polyhomoallylic fatty acids. J Labeled Compounds Radiopharmacol. 1993;33:541–6. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Martinez M. Severe deficiency of docosahexaenoic acid in peroxisomal disorders: a defect of delta 4 desaturation? Neurology. 1990;40(8):1292–8. doi: 10.1212/wnl.40.8.1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Food and Nutrition Board. Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein and Amino Acids (Macronutrients) National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Igarashi M, Ma K, Chang L, Bell JM, Rapoport SI, Demar JC., Jr Low liver conversion rate of alpha-linolenic to docosahexaenoic acid in awake rats on a high-docosahexaenoate-containing diet. J Lipid Res. 2006;47(8):1812–22. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600030-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Demar JC, Jr, Ma K, Bell JM, Igarashi M, Greenstein D, Rapoport SI. One generation of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid deprivation increases depression and aggression test scores in rats. J Lipid Res. 2006;47(1):172–80. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500362-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Igarashi M, Ma K, Chang L, Bell JM, Rapoport SI. Dietary n-3 PUFA deprivation for 15 weeks upregulates elongase and desaturase expression in rat liver but not brain. J Lipid Res. 2007 doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700315-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rao JS, Ertley RN, DeMar JC, Jr, Rapoport SI, Bazinet RP, Lee HJ. Dietary n-3 PUFA deprivation alters expression of enzymes of the arachidonic and docosahexaenoic acid cascades in rat frontal cortex. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12(2):151–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Murakami M, Kambe T, Shimbara S, Kudo I. Functional coupling between various phospholipase A2s and cyclooxygenases in immediate and delayed prostanoid biosynthetic pathways. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(5):3103–15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.5.3103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bosetti F, Weerasinghe GR. The expression of brain cyclooxygenase-2 is down-regulated in the cytosolic phospholipase A2 knockout mouse. J Neurochem. 2003;87(6):1471–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bazan NG, Aveldano de Caldironi MI, Rodriguez de Turco EB. Rapid release of free arachidonic acid in the central nervous system due to stimulation. Prog Lipid Res. 1981;20:523–9. doi: 10.1016/0163-7827(81)90092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Choi SH, Langenbach R, Bosetti F. Cyclooxygenase-1 and -2 enzymes differentially regulate the brain upstream NF-kappaB pathway and downstream enzymes involved in prostaglandin biosynthesis. J Neurochem. 2006;98:801–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03926.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rosenberger TA, Villacreses NE, Hovda JT, et al. Rat brain arachidonic acid metabolism is increased by a 6-day intracerebral ventricular infusion of bacterial lipopolysaccharide. J Neurochem. 2004;88(5):1168–78. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Basselin M, Chang L, Bell JM, Rapoport SI. Chronic Lithium Chloride Administration Attenuates Brain NMDA Receptor-Initiated Signaling via Arachidonic Acid in Unanesthetized Rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31(8):1659–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rabin O, Chang MC, Grange E, et al. Selective acceleration of arachidonic acid reincorporation into brain membrane phospholipid following transient ischemia in awake gerbil. J Neurochem. 1998;70:325–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70010325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Krystal JH, Sanacora G, Blumberg H, et al. Glutamate and GABA systems as targets for novel antidepressant and mood-stabilizing treatments. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7 (Suppl 1):S71–80. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McGeer EG, McGeer PL. Inflammatory processes in Alzheimer’s disease. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2003;27(5):741–9. doi: 10.1016/S0278-5846(03)00124-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chao MV, Rajagopal R, Lee FS. Neurotrophin signalling in health and disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 2006;110(2):167–73. doi: 10.1042/CS20050163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rao JS, Ertley RN, Lee HJ, et al. n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid deprivation in rats decreases frontal cortex BDNF via a p38 MAPK-dependent mechanism. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12(1):36–46. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Barco A, Pittenger C, Kandel ER. CREB, memory enhancement and the treatment of memory disorders: promises, pitfalls and prospects. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2003;7(1):101–14. doi: 10.1517/14728222.7.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Neufeld EJ, Majerus PW, Krueger CM, Saffitz JE. Uptake and subcellular distribution of [3H]arachidonic acid in murine fibrosarcoma cells measured by electron microscope autoradiography. J Cell Biol. 1985;101(2):573–81. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chang MC, Bell JM, Purdon AD, Chikhale EG, Grange E. Dynamics of docosahexaenoic acid metabolism in the central nervous system: lack of effect of chronic lithium treatment. Neurochem Res. 1999;24(3):399–406. doi: 10.1023/a:1020989701330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Igarashi M, DeMar JC, Jr, Ma K, Chang L, Bell JM, Rapoport SI. Docosahexaenoic acid synthesis from alpha-linolenic acid by rat brain is unaffected by dietary n-3 PUFA deprivation. J Lipid Res. 2007;48(5):1150–8. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600549-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]