Abstract

The deep sea (water depth of >2,000 m) represents the largest biome on Earth. Yet relatively little is known about its microbial community's structure, function, and adaptation to the cold and deep biosphere. To provide further genomic insights into deep-sea planktonic microbes, we sequenced a total of ∼200 Mbp of a random whole-genome shotgun (WGS) library from a microbial community residing at a depth of 4,000 m at Station ALOHA in the Pacific Ocean and compared it to other available WGS sequence data from surface and deep waters. Our analyses indicated that the deep-sea lifestyle is likely facilitated by a collection of very subtle adaptations, as opposed to dramatic alterations of gene content or structure. These adaptations appear to include higher metabolic versatility and genomic plasticity to cope with the sparse and sporadic energy resources available, a preference for hydrophobic and smaller-volume amino acids in protein sequences, unique proteins not found in surface-dwelling species, and adaptations at the gene expression level. The deep-sea community is also characterized by a larger average genome size and a higher content of “selfish” genetic elements, such as transposases and prophages, whose propagation is apparently favored by more relaxed purifying (negative) selection in deeper waters.

The oceans cover over two-thirds of our planet, with an average depth of ∼3,800 m. Microbes dominate the oceans' interior (42) and thus drive the biochemical cycles that sustain life in this habitat. Yet our knowledge of deep-sea bacteria and archaea has been severely impeded by the difficulties in isolating naturally important organisms and in simulating the in situ conditions of high pressure, low temperature, and low energy availability in the laboratory (45). Most of the deep-sea microbes studied to date either represent allochthonous and piezotolerant bacteria or are copiotrophic piezophiles isolated in rich media. There are very few isolates (with the possible exception of some relatively abundant Alteromonas species) that appear to be truly representative of predominant deep-sea planktonic microbes (9, 23). Therefore, the common characteristics that typify free-living planktonic deep-sea microbes remain largely unknown.

Some initial insights into microbial adaptations to the cold and high-pressure environment have started to emerge from recently completed genomic projects (recently reviewed in reference 23). For example, the genome of Photobacterium profundum, an organism isolated from a depth of 2,500 m, indicated that metabolic versatility encoded in a rather large genome (6.4 Mbp) (39) and flagellum-based motility (11) might be essential for survival in the deep-sea environment. Colwellia psychrerythraea, a psychrophilic marine bacterium living in ambient atmospheric pressure, employs several mechanisms to cope with low environmental temperatures, including changes to membrane fluidity and uptake and synthesis of compounds conferring cryotolerance (26). This and other studies (41, 43) have also implied that gene regulation and expression may constitute an important strategy for adaptation to cold and high-pressure conditions, although it is unlikely that differential expression of the same genes alone distinguishes piezotolerant from piezophilic organisms.

Metagenomics approaches can complement culture-based approaches and sidestep some of their limitations, providing new perspectives on life's adaptations to the deep-sea environment. Metagenomic libraries of planktonic microbes from seven different depths of the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre have recently revealed depth-specific trends in carbon and energy metabolism, gene mobility, host-viral interactions, and phylogenetic composition of microbial assemblages, among others (10). Several of these depth-stratified genomic features were further corroborated by another recent study that analyzed end sequences recovered from a microbial community residing at a depth of 3,000 m in the Mediterranean Sea (25). Nonetheless, the relatively shallow sequence coverage of the indigenous communities (∼10 Mbp per library) (10, 25) limited the resolution and depth of the phylogenetic and gene content analyses performed in these previous studies.

To provide more information on the qualitative and quantitative attributes of deep-sea microbial populations, we analyzed ∼200 Mbp of a random whole-genome shotgun (WGS) DNA sequence data library recovered from a microbial community residing at a depth of 4,000 m in the Pacific Ocean and compared it to similar WGS data from surface waters. Although an exhaustive comparison against many available surface WGS data sets was performed, we report here on comparisons against five representative samples of the Global Ocean Survey (GOS) project (31), since the results obtained for the remaining data sets were similar (data not shown). Surface water comparisons included samples 3 and 4 of the Sargasso Sea metagenome (38) (SAR3 and SAR4; also identified as GS000_S03 and GS000_S13, respectively, in the more-recent GOS study [31]), samples from the Caribbean open ocean (GS018), the Eastern Tropical Pacific open ocean (GS023), and the coastal Eastern Tropical Pacific (GS034, off the Galapagos islands). Comparisons between each of these data sets and our 4,000-m-depth sample provided very similar results (see, for instance, Fig. 1 and 5), suggesting the existence of specific trends that differentiated surface water microbial assemblages from those found at bathypelagic depths in the cold deep ocean.

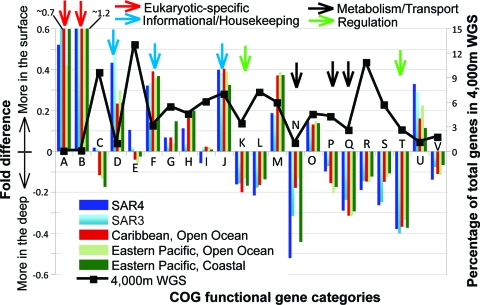

FIG. 1.

Differential abundance of genes in surface waters versus those at Station ALOHA at a depth of 4,000 m, based on COG functional categories. All nonredundant proteins predicted in the GOS surface water and the Pacific Ocean 4,000-m-depth WGS data sets were searched against the COG database to assign each protein to a major gene functional category. The differential abundance (y axis) of proteins assignable to each category (x axis) is shown. GOS samples shown are as follows: SAR3 and SAR4 (also identified as GS000_S03 and GS000_S13, respectively), Sargasso Sea (38); GS018, Caribbean open ocean; GS023, Eastern Tropical Pacific open ocean; and GS034, Eastern Tropical Pacific coastal (off the Galapagos islands) (31). COG categories are as follows (adapted from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/COG/): A, eukaryotic RNA processing and modification; B, eukaryotic chromatin structure and dynamics; C, energy production and conversion; D, cell division, chromosome partitioning; E, amino acid transport and metabolism; F, nucleotide transport and metabolism; G, carbohydrate transport and metabolism; H, coenzyme transport and metabolism; I, lipid transport and metabolism; J, translation and biogenesis; K, transcription; L, replication, recombination, and repair; M, cell wall/membrane/envelope; N, cell motility; O, protein turnover, chaperones; P, inorganic ion transport and metabolism; Q, secondary metabolism; R, general function prediction only; S, function unknown; T, signal transduction mechanisms; U, intracellular trafficking and secretion; and V, defense mechanisms.

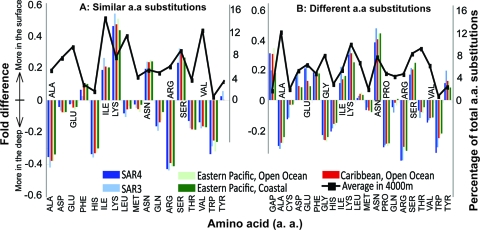

FIG. 5.

Differential usage of amino acids in protein sequences from surface versus deep waters. Homologs between a surface water WGS library (figure key) and the 4,000-m-depth WGS library were identified and aligned, in a pair-wise fashion, i.e., one sequence from a surface water library against a sequence from the 4000-m-depth library, based on a BLAST approach. The amino acid substitutions at similar (A) and different (B) substitution positions in the pair-wise alignments were compared to provide the differential usage of each amino acid in proteins from a depth of 4000 m relative to ones sampled by each surface water library. Bars represent the n-fold difference (y axes) in the usage of each corresponding amino acid (x axes). The black dotted line represents the fraction of the total amino acid substitution positions evaluated (secondary y axis) for each corresponding amino acid (x axis). For instance, alanine (Ala) constituted the largest fraction of the total substitution positions evaluated among all amino acids (∼10%), whereas tryptophan (Trp) and cysteine (Cys) represented the smallest fraction (constituting ∼1%). Amino acid usage trends were based on a total of about 800,000 substitution positions evaluated for each surface water WGS library. GAP represents the relative abundance of gaps in the alignments of homologous protein sequences.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sequencing, gene annotation, and nonredundant gene list.

Fosmid and WGS libraries were constructed and fully sequenced as described previously, using Sanger sequencing technology (10, 17). The deep-sea WGS library originated from the same sample and the same DNA preparation as the 4,000-m-depth fosmid library (the 4,000-m-depth Hawaii fosmid [HF] library), whose end sequences were published previously (10) (seawater samples were prefiltered through a 1.6-μm prefilter and collected on a 0.22-μm collection filter). Fosmid and untrimmed WGS sequences were annotated with the FGENESB pipeline for automatic annotation of bacterial genomes from Softberry, using the following parameters and cutoffs: general parameter file; open reading frame size, 90 nucleotide bases; expectation e-value, 1 × 10−10. Automated FGENESB annotations were manually refined and corrected, when necessary, by searching the annotated proteins against the GenBank (4), Pfam (12), and Clusters of Orthologous Genes (COG) (35) databases. tRNAs were identified using tRNAscan-SE 1.21 (http://selab.janelia.org/software.html).

To directly compare gene distributions in the surface water libraries of the GOS project with those of the deep-sea Pacific Ocean library, it was first important to determine the total unique sequence space sampled in each corresponding library. For this, the average insert size of each library was determined by searching the sister reads of a clone against each other using the BLASTN (nucleotide-level) algorithm, version 2.2.12 (2) (collection filters and library construction were otherwise very similar between the GOS and our WGS libraries). Of the total 101,176 clones, 61,057 in the Pacific library were found to have overlapping sister reads, by an average of ∼500 bp, suggesting an average insert size of ∼1.5 kbp for these clones; 30,528 had no overlapping sister reads, suggesting an average insert size larger than 2 kbp; and 10,176 had only one read per clone, e.g., the sister read sequencing reaction failed. Therefore, although the total sequence space for the 4,000-m-depth Pacific Ocean library was ∼194,517 kbp (average read length for untrimmed WGS reads was ∼1 kbp), the total unique sequence space was ∼162,817 kbp. The sister reads for Sargasso Sea samples 3 and 4 (SAR3 and SAR4) were rarely overlapping, suggesting an average insert size larger than 2 kbp, which is consistent with that reported in the original study (38), while the remaining GOS libraries had typically smaller inserts, similar to those of our 4,000-m-depth library. Raw gene counts within each data set were normalized to the size of the data set by dividing with either the total unique sequence space or the total number of nonredundant proteins (see below) of the data set, in order to make gene counts directly comparable between different data sets (see Table 1 for an example).

TABLE 1.

Comparisons between the SAR4 and 4,000-m-depth Pacific Ocean WGS data setsa

| Characteristic | Sample

|

Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SAR4 | Pacific Ocean (4,000 m) | ||

| Total unique sequence (Mbp) | 278.1 | 165 | 1.68 |

| Avg read length (after Q15 trim) | 837 | 850 | |

| G+C content (%) | 36.3 | 52.1 | |

| Total proteins annotated | 434,156 | 223,464 | |

| Unique protein clusters | 259,297 | 165,986 | |

| Clusters with Pfam matches | 116,503 (44.9%) | 72.327 (43.6%) | |

| Total matches against Pfam | 143,265 | 93,075 | |

| Clusters assignable to COG | 112,523 (43.4%) | 68,093 (41.0%) | |

| Avg aa identity against COG (%) | 44.8 | 46.4 | |

| Total matches against Sargasso | 109,631 (66%) | ||

| Matches for ribosomal proteins | 2,775 | 1,228 | 1.35b |

| Matches for DNA polymerase | 648 | 293 | 1.32b |

| Matches for tRNA synthetases | 2,194 | 966 | 1.35b |

| Genes from Raes et al. (28) (total matches) | 14,993 | 6,593 | 1.35b |

“Total matches against Sargasso” refers to BLASTP searches against the combined sample 3 and 4 protein sequences, using the exact same cutoff for a match as in the COG search. The cutoff in the COG search was 30% amino acid (aa) identity over at least 70% of the length of the COG matching protein.

These ratios have been normalized for the difference in size (1.68-fold, top row) between the two data sets compared. For example, for DNA polymerases, the ratio is (648/293)/1.68 = 1.32.

To get a nonredundant protein list for the gene distribution analyses from the typically overlapping WGS reads of the 4,000-m-depth Pacific Ocean data set, the following procedure was followed. All protein sequences annotated by the FGENESB pipeline were clustered using the BLASTCLUST algorithm (2) with the following parameters: −S 90 (similarity threshold), −L 0.5 (minimum length coverage), and −b F (require coverage on only one sequence of a pair); the remaining parameters were at the default settings. This procedure resulted in 165,986 clusters (from 223,464 original protein sequences), and the largest protein from each cluster was extracted to compile the nonredundant protein list. For consistency purposes, the same clustering approach was applied to the GOS samples as well. For instance, the total 434,156 proteins annotated in SAR4 by the FGENESB pipeline clustered in 259,297 unique clusters. The clustering approach also reduced the effect of uneven species abundance when comparing gene stoichiometries (see also below) between the surface water and deep-sea microbial assemblages, since overlapping sequences originating from the same species would cluster together at the cutoffs used.

Nonredundant proteins from each WGS library were assigned to the functional categories of the COG database (Fig. 1) essentially as described previously (22), requiring as a minimum cutoff for a match 30% amino acid identity over at least 70% of the length of the top-matching COG protein. The same cutoff was used in the analysis that aimed to identify the BLASTP top matches of WGS proteins against GenBank's nonredundant database. Transposase counts (e.g., see Fig. 3) were based on counts of the number of annotated protein sequences in the FGENESB pipeline that contained in their annotation the word “transposase” or “insertion sequence,” typically with no further refinement of the annotation.

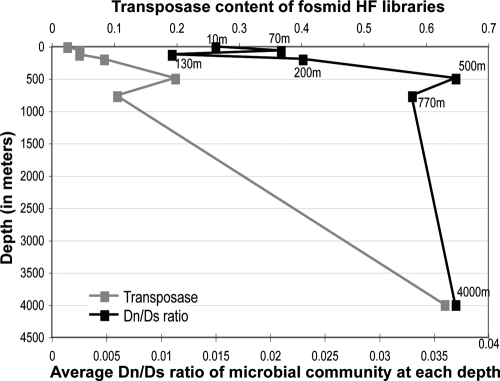

FIG. 3.

Correspondence between transposase gene content and average Dn/Ds ratio with depth as revealed by fosmid libraries. The average Dn/Ds ratio of a fosmid library (10) relative to the 4,000-m-depth (reference) WGS library (black points, primary x axis) is plotted against the depth that the fosmid library originated from (y axis). Note that the transposase content of the HF libraries (secondary x axis) correlates well to the Dn/Ds ratio of the libraries, particularly from a depth of 10 m to 770 m.

Gene stoichiometry based on the Pfam database.

All nonredundant proteins in a library were searched against the Pfam database (February 2006 release; 8,296 models in total; available at www.sanger.ac.uk/Software/Pfam/) using the hmmpfam algorithm (part of the Hmmer package, which is distributed by the author, Sean Eddy, through the website http://hmmer.janelia.org/#contrib). The number of significant matches, i.e., e-value lower than 0.1 according to the recommendations of the author, for each Pfam model was counted and normalized for the size of the WGS data set, used as described above. Query proteins were allowed to match more than one Pfam model. Proteins were searched first against the full-length models of Pfam; proteins with no significant match at the 0.1 e-value cutoff were subsequently searched against the fragment models of Pfam for significant matches. Proteins with no significant matches against the fragment Pfam models were denoted as hypothetical.

Genome size estimation.

The estimates of the relative genome size difference between the deep-sea and surface water communities were based on the distribution of single-copy genes in the corresponding WGS metagenomic data sets. In particular, all proteins annotated in a data set were searched against the Pfam database, as described above, for significant matches against Pfam models of ribosomal proteins, DNA polymerase subunits, and tRNA synthetases. The matches were counted and normalized for the difference in size between the data sets, and their normalized ratio (deep-sea versus surface water normalized counts) provided an estimate of the relative genome size difference, independently for each of the three protein families evaluated. Raes and colleagues (28) have recently developed a similar approach for calculating average genome size in WGS data that is based on the relative distribution of a selected subset of proteins from the String database (40) and the BLAST algorithm (2). Using the same approach and protein set, we found a protein ratio (i.e., 1.3 to 1.4) that was very comparable to the ratio of our Pfam-based approach (all results are reported in Table 1). Raes and colleagues have estimated the average genome size for SAR3 and SAR4 to be ∼1.5 to 1.6 Mbp (28); by extrapolation, our estimate based on the method of Raes and colleagues for the 4,000-m-depth microbial community was 2.2 to 2.4 Mbp. Raes et al. performed a kingdom assignment of the WGS read prior to the estimation of the bacteria/archaea-specific average genome size; we have not performed a kingdom assignment. However, the deep-sea library contained no detectable eukaryotic DNA, while small amounts (<5%) of eukaryotic DNA were detectable in the GOS surface water libraries based on the COG sequences (Fig. 1) and rRNA gene counts (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Hence, our extrapolation based on the Raes et al. estimate in surface water communities is reliable, although it likely represents a slight underestimation of the deep-sea community average genome size due to the higher abundance of eukaryotic DNA (eukaryotes typically have larger genome sizes) in the surface water libraries.

Dn/Ds ratio calculation.

In order to perform accurate estimations of the nonsynonymous versus synonymous substitution (Dn/Ds) ratios, it was first necessary to normalize for the variation in the sequencing error rate among the WGS and fosmid end sequence data sets used in this study. For this, all raw sequences were cleaned and trimmed using the same Q15 quality cutoff for base calling and the Phrap-Phred package (P. Green, Genome Sciences Department, University of Washington, Seattle, WA [distributed by the author]). Trimmed WGS sequences were similar in length, regardless of the data set considered, averaging ∼840 bp.

(i) HF libraries.

The sequences (about 10 Mbp per library) of the previously published end sequences from the HF libraries (10) were annotated with the FGENESB pipeline, using identical settings as described above for WGS libraries for consistency purposes. Annotated proteins, when larger than 100 amino acids long, were searched against the nonredundant proteins from the 4,000-m-depth Pacific Ocean WGS library using BLASTP (protein level; default settings) for matches of 80% to 95% amino acid identity that covered at least 90% of the length of the query protein. HF proteins and 4,000-m-depth WGS proteins related at this identity cutoff were subsequently aligned, in a pair-wise fashion (i.e., one 4,000-m-depth protein per HF protein) using the CLUSTAL W algorithm (36). The corresponding nucleotide sequences of the aligned protein sequences were subsequently aligned, codon by codon, using the pal2nal script, with “remove mismatched codons” enabled and the protein alignment as the guide (34). The Dn/Ds ratio for each pair of proteins was calculated with the nucleotide codon-based alignments using the codeml module of the PAML package (44). Dn/Ds ratios for all query protein sequences that originated from a single library (and hence depth) were averaged to provide the mean Dn/Ds ratio for the microbial community at the corresponding depth relative to the 4,000-m-depth (reference) microbial community. Dn/Ds ratios were plotted against the Ds value (Fig. 2) or were derived only from protein pairs that showed a Ds value of >1 (Fig. 3), to provide a time-independent assessment of the strength of selection as proposed previously (29). Protein sequences shorter than 100 amino acids long were excluded from the analysis to avoid short spurious open reading frames called by the annotation pipeline, which presumably do not represent genuine protein-coding regions of the genome (24, 27). The high-stringency cutoff on sequence identity ensured that only highly related (homologous) proteins triggered a match; using the same cutoffs for a match for all depths sampled ensured that Dn/Ds results for proteins that originated from different depths were directly comparable. On average, ∼173 protein pairs per depth (minimum, 64; maximum, 323) met the above criteria and hence were used in the calculation of the average Dn/Ds ratio of the corresponding library.

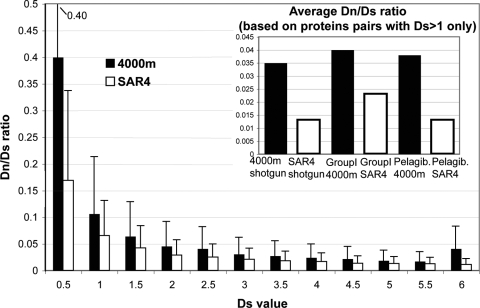

FIG. 2.

Codon substitution patterns between proteins from surface waters versus proteins from a depth of 4,000 m. The average Dn/Ds ratio (y axis) for the 4,000-m-depth Pacific Ocean microbial community (filled bars) and the community sampled in the Sargasso Sea sample 4 metagenome (open bars) is plotted against the synonymous substitution rate (Ds) (x axis). Error bars represent one standard deviation of the mean; most means are statistically different by Student's t test. Note that the Dn/Ds ratio is always two to three times higher in the former community, regardless of the time since divergence of the protein sequences under scrutiny (represented by Ds) (29), revealing more relaxed purifying selection at a depth of 4,000 m. Abundant populations of planktonic group I Crenarchaea and Pelagibacter at a depth of 4,000 m also showed two to three times higher Dn/Ds ratios, on average, compared to their surface water counterparts in the Sargasso Sea (inset).

(ii) GOS and 4,000-m-depth WGS libraries.

Protein sequences in the nonredundant protein list of a WGS library, when larger than 100 amino acid long, were searched against all protein sequences within the same library for matches of 80% to 95% amino acid identity that covered at least 90% of the length of the query protein. Approximately 25,000 to 35,000 proteins per library had one or more significant matches (in addition to the self-match) at this cutoff. These proteins were subsequently aligned against their matching sequence (pair-wise fashion), and the Dn/Ds ratios for each protein pair were calculated as described above for HF proteins. The average Dn/Ds ratio for each shotgun library was based on the Dn/Ds ratios of ∼30,000 protein pairs. All protein sequences used in the average Dn/Ds ratio calculation originated from the same shotgun library, as opposed to the HF libraries above, where one protein originated from the HF library and the other was always from the 4,000-m-depth shotgun (reference) library.

Amino acid substitution analysis.

To study the preferential usage of specific amino acids in deep-sea proteins relative to their homologs from surface waters, the following approach was undertaken: nonredundant protein sequences from a GOS WGS data set were searched, using the BLASTP algorithm, against the nonredundant proteins from the 4,000-m-depth WGS data set for matches of at least 50% amino acid identity over at least 70% of the length of the query protein. The amino acids at all positions in the alignment of matching proteins, which were different but were scored with a positive score by BLAST (i.e., similar amino acid substitutions), were counted for both aligned protein sequences (i.e., one from the GOS and the other from the 4,000-m-depth shotgun library). The amino acids that differed but were scored with a negative score by BLAST (i.e., different amino acids substitutions) were also counted separately. For each of the 20 common amino acids, the total number of times they were encountered in all substitution positions in the sequences of all query surface proteins were compared to the same number for all matching deep-sea proteins to provide the preferential usage of the amino acid in the surface water versus deep-sea proteins (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material, which shows a graphical illustration of the method). Three estimates were performed, i.e., similar substitution positions only, different positions only, and similar and different combined. The high-stringency cutoff on sequence identity ensured that only homologous proteins (either orthologous or paralogous) triggered a match (30, 32).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

All fully sequenced fosmids and the WGS data from the 4,000-m-depth sample are available in GenBank under accession numbers EU016559 to EU016674 and ABEF00000000, respectively.

RESULTS

Uniqueness of the deep-sea metagenome.

The majority (∼55%) of the nonredundant proteins annotated in the 4,000-m-depth microbial library did not share a significant match against common protein databases such as Pfam (12) and COG (35), revealing that most of the deep-sea microorganisms had genetic makeups very different from those of the cultured organisms available in the public databases. This fraction of hypothetical proteins, however, was not substantially different from the fraction of hypothetical proteins in the surface water microbial populations sampled in the GOS metagenomes. For instance, the SAR4 and 4,000-m-depth data sets had a very similar number of proteins assignable to Pfam (44.9% versus 43.6%, Sargasso versus deep-Pacific data, respectively), and these proteins showed an average amino acid identities similar to their COG top matches (44.8% versus 46.4%). Therefore, the deep-sea microbial genome content was not substantially more novel than that of the surface waters. In addition, the surface water and deep-sea microbial assemblages were related in terms of gene content, since ∼60% of the hypothetical proteins (i.e., no significant match against the public databases) from the deep sea shared a significant match of 52.2% amino acid identity, on average, with the Sargasso Sea proteins (Table 1).

The great majority of the organisms sampled in the deep-sea WGS library were planktonic bacteria and archaea, as indicated by the absence of eukaryotic rRNA genes (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) and the low number (<50) of annotated proteins that had their top matches in a eukaryotic-specific COG gene category (Fig. 1). Bacteria appeared to dominate the deep-sea microbial library, with ∼70% of the total rRNA genes derived from bacteria versus ∼10% from archaea (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). About 20% of the rRNA genes recovered could not be assigned with high confidence to the bacterial or the archaeal domain due to their very short sequence lengths and/or because they were representative of uncharacterized deep-branching taxa. The majority of these unassigned rRNA gene sequences, however, were presumably bacterial, given that analysis of the top matches of all annotated proteins against all microbial genomes in GenBank revealed that only ∼7% of the top matches were archaeal. Eukaryotic rRNA genes or protein sequences with top matches in the eukaryotic sequences of GenBank were virtually undetectable in the 4,000-m-depth data set (Fig. 1; also see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

Adaptations at the gene content level.

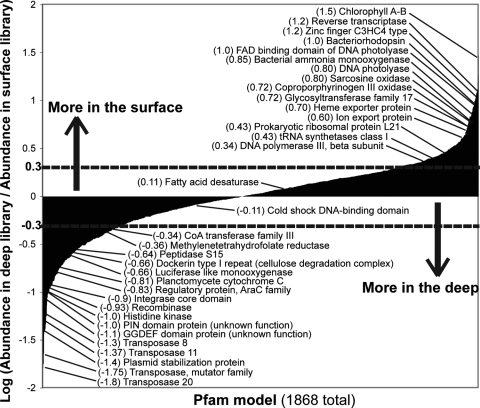

Analysis of differential gene abundance in the deep-sea WGS data relative to the surface water WGS data has the potential to reveal important biochemical and functional adaptations specific to each environment. The majority of genes, however, appeared evenly distributed, e.g., 1,176 out of a total of 1,868 (63%) Pfam families evaluated showed less than a twofold difference in abundance between the surface water versus deep-sea normalized data sets (Fig. 4), indicating that fundamental physiology and metabolism do not differ greatly between the surface and the abyss. Several genes previously implicated in high-pressure and/or cold adaptation, such as cold-shock domains and fatty acid desaturases (26, 39), did not appear to be greatly enriched in the deep-sea metagenome, indicating that these adaptations might be controlled at the expression or the posttranslation level. Although energy sources differ greatly between the photic zone and the deep sea, genes for autotrophic CO2 assimilation showed comparable abundances between these habitats, whereas representative genes of the nitrogen cycle were two- to threefold more abundant in the surface water data sets (with the exception of the nitrite reductase, NirK [see Table S2 in the supplemental material]).

FIG. 4.

Differential abundance of genes in surface waters versus those at Station ALOHA at a depth of 4,000 m, based on the Pfam database. All nonredundant proteins predicted in the Sargasso Sea sample 4 (SAR4) and the 4,000-m-depth Pacific Ocean WGS data sets were searched against the Pfam database to assign each protein to a Pfam model. The differential abundance (y axis) of proteins assignable to 1,868 Pfam models (x axis), which had at least one significant match in both data sets, is shown. Several important models (discussed in the text) have been annotated. All underlying data of the Pfam analysis, including Pfam models that found significant matches in only one of the data sets, are provided in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Dashed lines represent the log 2 boundary in relative abundance.

Several significant differences in gene content were, however, observed. As anticipated and noted previously (10), genes related to photosynthesis, such as chlorophyll A-B binding proteins and rhodopsin photoproteins (3), as well as to processes accessory to photosynthesis, such as pigmentation proteins (e.g., coproporphyrinogen production) and heme exporters, were among the most abundant genes in the surface samples, in contrast to the deep-sea microbial plankton (>10-fold difference) (Fig. 4). Additionally, genes involved in repairing UV-induced DNA damage (e.g., DNA photolyase) and in oxidative stress response (e.g., sarcosine oxidase) were also more enriched in the surface water WGS data than in the deep-sea community. In contrast, transposases, phage integrases, plasmids, recombinases, and hypothetical proteins (see Table S3 in the supplemental material) predominated in the deep sea, compared to the surface water samples (>10-fold difference). These results corroborate the high abundance of transposases in the subphotic zone, as reported previously, based on a shallower sequencing coverage of large DNA fragment fosmid libraries (10). Regulatory proteins, including transcription factors and signal transduction systems, as well as metabolic genes, were also encountered more frequently in the 4,000-m-depth data set than in the surface water set, regardless of the location of the surface water data set used in the analysis (e.g., open versus coastal ocean, or Caribbean Sea versus Pacific Ocean [Fig. 1]). The latter genes reflected several presumably prevalent modes of carbon and energy metabolism in the bathypelagic microbial communities. Among the most notable examples, threefold more luciferase oxygenase homologs (bioluminescence production) and dockerin type I repeats (involved in cellulose degradation) were found in the normalized deep-sea data set than in the surface water WGS data set.

Phylogenetic analysis and sequence comparisons indicated that the majority of differences involving abundant protein families were, most often, representative of community-wide signatures, as opposed to the differential distribution of one or a few specific microbial groups. For example, the 658 deep-sea sequences (versus 28 in SAR4) belonging to the most abundant transposase family (COG2801) showed a distribution of G+C content from 40% to 70% (the community average is ∼52%). About 295 of these (45%) did not match any other transposase at a 97% nucleotide identity cutoff (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). (The transposase sequences originated from untrimmed WGS sequencing reads, which had an estimated maximum sequencing error of 2%; hence, the 97% cutoff was used to group together only recently duplicated transposase gene copies.) If these 658 sequences belonged mainly to a single (or a few) close phylogenetic group(s) or represented the recent expansion (duplication) of a few invasive transposase variants, many more similar sequences would have been observed. Further, the sister reads of many of the transposase-containing WGS sequences were phylogenetically affiliated (based on best-match analysis against all available sequenced genomes at the end of 2007) with many different taxa, as well as different phyla (see Table S4 in the supplemental material). A few cases where the gene content differences were presumably due to the presence (or absence) of a specific group were also noted. Most notably, cytochromes that appeared to originate from Planctomycetes representatives based on phylogenetic analyses were relatively more abundant in the deep-sea sample (Fig. 4), a signature corroborated by the apparent absence of this phylum in the surface water samples, as indicated by rRNA gene counts (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

Relaxed selection in the deep sea appears to explain some gene content differences.

The increased content of mobile elements in the deep-sea versus the surface water metagenome, clearly the most profound signature of the deep-sea community, raised the question of whether relaxed purifying (negative) selection or positive selection for the functions associated with these mobile elements has fostered their expansion. Analysis of the Dn/Ds ratio can provide some clues about the strength of selection, with lower Dn/Ds values being indicative of stronger negative selection on protein sequences. Homologous proteins within the 4,000-m-depth data set showed two to three times higher Dn/Ds ratios than their surface water counterparts (Fig. 2). Similar results were noted when proteins of two abundant and phylogenetically unrelated autochthonous populations, as opposed to randomly selected WGS proteins, were examined. Proteins encoded in deep-sea Crenarchaea (20) and Pelagibacter (Alphaproteobacteria) (15) genomes showed average Dn/Ds values of 0.035 and 0.04 versus 0.01 and 0.02 for their shallow-water relatives, respectively (Fig. 2, inset). Notably, Dn/Ds analysis on a small number of available protein sequences from seven different depths of the Pacific Ocean (10) indicated that Dn/Ds ratios increased with depth, which corresponded with increased transposase content at greater depths (Fig. 3).

Although it is possible that some of the transposase sequences may have been under positive selection, the results generally indicated that relaxed selection promoted the expansion of the majority of mobile elements in the deep-sea genomes. The identification of several instances where transposases truncated evolutionarily conserved (hence, presumably essential) genes or were in close proximity with other transposases and/or prophage integrases (see Table S4 in the supplemental material for an example) is also consistent with the latter hypothesis. Relaxed selection might be due to the slower growth rates and/or smaller population sizes that typify deep-sea microbial communities.

Protein amino acid adaptations.

To provide insights into deep-sea adaptations at the protein level, the protein sequences recovered in the surface water WGS data sets (31) were aligned and compared against their orthologs in the 4,000-m-depth WGS data set. In particular, the preferential usage of an amino acid at positions that differed in the alignment of orthologs was calculated, essentially as performed previously (16, 46) (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material and Materials and Methods for details). In general, amino acid usage patterns showed only subtle differences between the surface water and deep-sea proteins, e.g., no greater than a 0.3-fold difference was observed between any of the samples analyzed. Nonetheless, several noteworthy trends became evident. The most prevalent trend was an increased content of nonpolar and hydrophobic residues, i.e., alanine (Ala), glycine (Gly), proline (Pro), and valine (Val), in proteins from the deep waters, at the expense of polar residues, such as asparagines (Asn) and serine (Ser), and charged residues, such as lysine (Lys) (Fig. 5). On average, the deep-sea protein sequences contained ∼10% more nonpolar and hydrophobic amino acids and showed a preference for lower-volume amino acid residues than their surface water analogs (see Fig S6 in the supplemental material). Comparable results were obtained when similar amino acid substitution positions (the substituted amino acid is biochemically related) were evaluated separately from different amino acid substitution positions (the substituted amino acid is not related), which underlines the robustness of the trends observed. Furthermore, gaps in the alignments of orthologous proteins were more abundant in the proteins from the surface water, suggesting that proteins from deep-sea microbes are larger in size, potentially a consequence of less “streamlining” (relaxed purifying selection) in deeper waters (Fig. 5).

Variations in average G+C content also accounted for some of the differences observed in amino acid usage patterns between the surface water and deep-sea proteins. For instance, the preferential usage of lysine and asparagine, which are encoded by AT-rich codons, in surface water proteins from the Sargasso and Caribbean Seas relative to their counterparts from 4,000 m deep in the Pacific Ocean might be attributable to the lower G+C contents of the former metagenomes (36.3% versus 52.1%). However, the influence of G+C content or other site-specific environmental parameter variations on the derived results should be rather minor. For instance, the coastal Tropical Pacific Ocean metagenome (GS034) had a significantly higher G+C content (40.2%) than the other GOS data sets used in our study; yet, it showed amino acid usage trends very comparable to those observed with the other GOS data sets (Fig. 5). Further, amino acid usage patterns analogous to those reported for the surface water WGS data sets were observed for proteins recovered in the end sequences of seven fosmid libraries constructed from samples from different depths in the Pacific Ocean (10) (see Fig. S4 and S5 in the supplemental material). The latter comparisons also revealed, as expected, that amino acid usage patterns for sequences from deeper samples (i.e., 500 and 770 m) and the 4,000-m-depth reference sequences were more similar than sequences from 130 m (chlorophyll maximum depth) and 200 m (lower euphotic zone). (Some of the variation observed may be due to the shallow sequencing obtained in the previous study [10] and the unique physicochemical properties characterizing each depth sampled.) The congruence in the results obtained with different surface water WGS data sets and the fosmid libraries suggests that the trends in amino acid usage patterns revealed by our analyses are real, reproducible, and relatively independent of the sampling site or the library used.

Species composition of the deep-sea microbial communities. (i) Taxa distribution and community complexity.

rRNA gene counts in the WGS data (normalized for library size) suggested that the deep-sea and surface water communities were in some respects similar in terms of phyla representation (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Alpha- and gammaproteobacteria appeared to dominate both communities, together comprising 50 to 70% of the total rRNA genes identified, with alphaproteobacteria representing a relatively higher fraction of the surface water community rRNA genes than the deep-sea ones (∼40% versus 25%). Several phyla were, however, differentially abundant. The most obvious examples were the presence of photosynthetic Cyanobacteria only in the shallow waters and the higher proportions of Crenarchaea, Deltaproteobacteria, Planctomycetes, and Chloroflexi at a depth of 4,000 m. With the exception of the Deltaproteobacteria, which comprised ∼12% of the deep-sea rRNA genes, none of the differentially abundant phyla constituted more than about 5% of total rRNAs within a community.

To provide a high-resolution comparison of the complexity (species richness and evenness) of the deep-sea microbial community relative to the community of the surface waters of the Sargasso Sea, we evaluated the assemblies of comparable subsets of the WGS data sets. Analysis showed that the number of unassembled (singletons) WGS reads and the number and average length of assembled contigs were comparable between the deep-sea and the surface water assemblies (Table 2). Thus, these results are not supportive of large differences in the complexity of the surface water and the deep-sea microbial communities. The high similarity between the two communities based on rRNA gene counts (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) is also consistent with these interpretations. A high number of species and/or rare species constituting a large fraction of the communities probably accounts for the very short contigs assembled from both the deep-sea and surface water metagenomes.

TABLE 2.

Statistics of the assemblies of the SAR4 and 4,000-m-depth Pacific Ocean WGS data setsa

| Characteristic | Sample

|

|

|---|---|---|

| SAR4 | Pacific Ocean (4,000 m) | |

| No. of reads used | 102,000 | 102,297 |

| No. of singlets | 82,866 (81.2%) | 80,965 (79.2%) |

| No. of contigs | 7,124 | 8,450 |

| Avg contig length | 1,190 | 1,241 |

| Avg read length | 830 | 818 |

For consistency purposes, a subset of the SAR4 data set that was comparable in size and was trimmed with the same quality criteria for base calling as the 4,000-m-depth Pacific Ocean data set was used. Sequences were selected at random, provided that sister reads of the same clone did not overlap, in which case only one of the sister reads was used in the assembly. Assemblies were performed with the Phrap-Phred package (P. Green, Genome Sciences Department, University of Washington, Seattle, WA [distributed by the author]) using identical parameters for both data sets.

(ii) Genes for chemolithotrophic ammonia oxidation in deep-sea Crenarchaea.

Queries of available genomic sequences in GenBank against the 4,000-m-depth WGS metagenome revealed that planktonic Crenarchaea represented the most abundant population, constituting about ∼3% of the total WGS reads available (21). This relatively high in situ abundance allowed the assembly of a large genomic scaffold representing the deep-sea Crenarchaea from crenarchaeal fosmid clones from the same 4,000-m-depth sample (21). These sequences, together with the crenarchaeal WGS sequences identified in this study, allowed a sequence-based assessment of crenarchaeal ammonia monooxygenase subunit genes, which were recently reported to be substantially depleted, by at least one to two orders of magnitude in the genomes of deep-sea versus surface water Crenarchaea (1, 8). Our genomic assessment revealed that all the known crenarchaeal genes associated with nitrification (18) were present in the 4,000-m-depth crenarchaeal genomic scaffold, including ammonia monooxygenase subunit genes (amoA, amoB, and amoC), the urease operon, and the ammonia permease gene. The ratio of individual crenarchaeal ammonia monooxygenase sequence reads to crenarchaeal 16S rRNA sequence reads in the unassembled 4,000-m-depth WGS library was 1 to ∼3 (1 to ∼5 for 23S rRNA). This stoichiometry is consistent with a 1:1 ratio of amoA genes to 16S rRNA genes, since the length of the amo genes (∼600 bp) is approximately one-third of that of the 16S rRNA gene, and planktonic Crenarchaea genomes contain only one rRNA operon (17). Using an identical approach, we found a similar stoichiometry between crenarchaeal amo and rRNA genes in winter samples of the Sargasso Sea, where Crenarchaea were present in substantial abundance (Table 3; note that the slightly higher abundance of the amo genes in the surface water data set is within the sampling error of the metagenomic libraries). We conclude that most if not all crenarchael cells at a depth of 4,000 m in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre contain genes associated with ammonia oxidation. The discrepancy of our findings with the quantitative PCR results reported previously (1, 8) may be due to the failure of quantitative PCR primers to amplify the amoA genes of some deep-sea Crenarchaea. Consistent with this hypothesis, the reverse amoA oligonucleotide primer sequence used in prior studies has three mismatches with the deep-sea crenarchael amoA sequences reported here, with one occurring toward the 3′ end of the sequence, a critical region for primer annealing and extension (see Fig. S7 in the supplemental material). These data do not support well the hypothesis of Agogue et al. (1) that most deep-sea Crenarchaea lack amoA genes and therefore are heterotrophic.

TABLE 3.

Crenarchaeal nitrogen metabolism gene presence in WGS data setsa

| Gene | Lengthb | No. in sample

|

Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAR3 | Pacific Ocean (4,000 m) | |||

| amoA | 588 | 7 | 2 | 3.5 |

| amoB | 573 | 7 | 2 | 3.5 |

| amoC | 568 | 5 | 2 | 2.5 |

| Ammonia permease | 1,866 | 15 | 6 | 2.5 |

| 16S rRNA | 1,473 | 13 | 7 | 1.9 |

| 235 rRNA | 2,995 | 24 | 13 | 1.8 |

Selected Cenarchaeum symbiosum genes (first column) were queried against the unassembled WGS data sets using TBLASTN (protein level) or BLASTN (nucleotide level for rRNA) algorithms. The resulting alignments, when longer than 100 aligned nucleotides (33 amino acids), were visually inspected to determine the number of WGS sequences per data set that contained crenarchaeal homologs (third and fourth columns). In general, the distinction of crenarchaeal homologs from homologs of unrelated organisms or spurious matches was greatly facilitated by the fact that the former homologs typically showed much higher identity to the C. symbiosum query proteins (>80% for proteins and >90% for rRNAs versus <50% and <70%, respectively).

Gene length in bp.

DISCUSSION

Our analyses identified several key genomic features that together may facilitate microbial survival and growth in the deep-sea environment, such as metabolic tuning toward the energy sources available in the deep sea (Fig. 1 and 4), genomic plasticity (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), and protein alterations potentially important for function in the cold, high-pressure environment (Fig. 5). Although these adaptations are subtle (excluding genomic plasticity and abundance of mobile elements) compared to the major features observed in surface water communities (e.g., photosynthesis, UV damage repair, and streamlining, to name a few examples) (Fig. 4), they do reflect the divergence and isolation of the deep-sea microorganisms and their genes from their surface water counterparts. Consistent with these interpretations, abundant planktonic microbial populations, such as Crenarchaea and Pelagibacter, are genomically distinct between different depths (Fig. 2; amino acid identities are shown in Table 1 and in our previous study [21]). The high similarity in the results obtained from comparisons with different surface water metagenomes, including those from the North and Eastern Tropical Pacific Ocean, the Sargasso Sea, and the Caribbean Sea (Fig. 1 and 5), also suggests that the differences between the deep sea and the surface are robust and reproducible and probably independent of the specific site sampled. Although there is a constant rain of biological material from shallow to deep waters, resulting in a largely unidirectional material and genetic transfer, the selective pressures at greater depths seem to ameliorate most of this potential surface water signature in the deep.

If dramatic adaptations specific to the deep-sea microbial assemblages are to be found, our analysis indicates that these likely occur at levels not detectable solely by sequence data. More likely, these adaptations will be manifested as changes in gene expression, posttranslational modifications, or coordinated enzymatic and physiological responses, as has been suggested previously (23, 41, 43). Several (>50) hypothetical or conserved hypothetical protein families (clusters) were found to be among the most differentially abundant genes in the surface waters versus the deep sea (see Table S3 in the supplemental material), in patterns similar to the enrichment of mobile genes in the deep-sea microbial assemblage or photosynthetic genes in the surface waters. Therefore, it also seems plausible that some dramatic differences in gene content can be found in deep-sea-adapted microorganisms but remain obscured within uncharacterized hypothetical genes. Given that about half of the protein sequences recovered in the deep-sea metagenome were hypothetical or conserved hypothetical (Table 1), these findings underscore our limited knowledge of the genetic and physiological mechanisms important for living in the bathypelagic habitat (23, 41, 43).

The higher proportions of regulatory, mobile, and metabolic genes relative to genes included in information processing (e.g., ribosomal proteins and polymerase subunits) (Fig. 4) suggested the importance of metabolic diversity and genome plasticity in the deep-sea microbial assemblages. This pattern resembles the gene content shifts with (larger) genome size observed through the comparative analysis of whole-genome sequences of cultivars (22, 37), implying that the genome size of many deep-sea-adapted microorganisms is significantly larger than that of their surface water-adapted counterparts. Using a recently developed method for genome size estimation in WGS data (28), we estimated a 1.35- ± 0.25-fold increase in genome size in bethypelagic versus shallow-water microbial genomes, with an average genome size of 2 to 2.2 Mbp in the deep-water community (Table 1). Table 1 may represent a slight underestimation, given that eukaryotic DNA is more abundant in the surface water than in the deep-sea library, based on ribosomal rRNA gene (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) and COG homolog (Fig. 1) counts. It has been previously hypothesized that larger-genome-sized species may dominate in environments where resources are scarce but diverse, and where there is little penalty (e.g., reduced purifying selection) for slow growth, such as soil (22). Our results (Fig. 1 and 2) provide some evidence in support of this hypothesis, since resource scarcity and heterogeneity, and relaxed selection, appear to characterize the deep versus the shallow waters, and the average microbial genome size appeared significantly larger in the deep sea (Table 1). Some of these ecological trends in gene content appear therefore to apply across habitats as diverse as soils and the deep sea.

Several previous studies have suggested that more charged (ionized and/or polar) and higher-volume residues are preferred in organisms living at higher temperatures (5, 19, 26), consistent with the opposite trend (more neutral and nonpolar residues) observed here for microbial assemblages of the deep and cold deep sea (Fig. 5; also see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). Zeldovich and colleagues (46), based on the analysis of 204 complete bacterial and archaeal genomes, suggested a universal set of amino acids, namely isoleucine, valine, tryptophan, arginine, glutamic acid, and leucine (Ile, Val, Tyr, Arg, Glu, and Leu), that highly correlated with the optimum temperature for growth of every organism. From this universal set, only isoleucine, valine, and arginine were found to differ moderately in abundance in our surface water versus deep-sea comparisons. Lysine, asparagine, and serine (Lys, Asn, and Ser) constituted a much more important fraction of the total amino acid substitutions than did the latter three residues (Fig. 5). Further, Grzymski and colleagues recently noted decreased proline and arginine (Pro and Arg) content in six cold-adapted fosmid clone sequences from Antarctica (16), whereas these residues were among the most differentially abundant residues in the deep-sea microbial proteins according to our evaluations. This discrepancy may be due to the combined effects of high pressure and low temperature in the deep sea, and the smaller sample sizes of previous studies, which may not be as representative. Interestingly, hydrophobicity, which appears important for the thermostability of proteins at high temperatures (19, 46), was also important in the deep-sea proteins in our metagenomic comparisons. Enzyme adaptation to low temperatures is conferred, in part, by weaker intramolecular interactions that favor greater molecular flexibility and higher catalytic efficiencies (6, 33). In the deep sea, preserving protein conformation and stability represents an additional challenge. Thus, deep-sea protein adaptations likely reflect the balance for maintaining the added flexibility required at low temperatures and stability in the face of high pressure (6, 33). Clearly, protein adaptation to the deep-sea physicochemical conditions is complex and requires further investigations of many parameters, including buried versus exposed amino acid residues, physical and structural interactions among amino acid residues, and the kinetics and volume changes associated with the different reactions (7, 14).

Microbial metagenomic data sets such as the 4,000-m-depth genomic sample described here represent useful resources for future investigations. These data sets, coupled with future cultivation-dependent and cultivation-independent studies, should help to better refine our understanding of the specific genetic, biochemical, physiological, and metabolic properties of deep-sea-adapted microbes and microbial communities. Transcriptomic approaches (13), functional protein characterization, and time series measurements can complement these efforts and bring a deeper perspective on the biology and ecology of the most abundant inhabitants in Earth's largest biome.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Hawaii Ocean Time series staff and crew for assistance in sample collection at Station ALOHA.

This work was supported by a grant from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and NSF Science and Technology Center Award EF0424599, to E.F.D. and D.M.K., NSF Microbial Observatory Award MCB-0348001 to E.F.D., and sequencing support from the Department of Energy Genomics GTL Program.

This work is a contribution from the Center for Microbial Oceanography: Research and Education (C-MORE).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 19 June 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agogue, H., M. Brink, J. Dinasquet, and G. J. Herndl. 2008. Major gradients in putatively nitrifying and non-nitrifying Archaea in the deep North Atlantic. Nature 456:788-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beja, O., E. N. Spudich, J. L. Spudich, M. Leclerc, and E. F. DeLong. 2001. Proteorhodopsin phototrophy in the ocean. Nature 411:786-789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benson, D. A., I. Karsch-Mizrachi, D. J. Lipman, J. Ostell, and D. L. Wheeler. 2007. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:D21-D25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berezovsky, I. N., K. B. Zeldovich, and E. I. Shakhnovich. 2007. Positive and negative design in stability and thermal adaptation of natural proteins. PLoS Comput. Biol. 3:e52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brindley, A. A., R. W. Pickersgill, J. C. Partridge, D. J. Dunstan, D. M. Hunt, and M. J. Warren. 2008. Enzyme sequence and its relationship to hyperbaric stability of artificial and natural fish lactate dehydrogenases. PLoS ONE 3:e2042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cavicchioli, R. 2006. Cold-adapted archaea. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4:331-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Corte, D., T. Yokokawa, M. M. Varela, H. Agogue, and G. J. Herndl. 2009. Spatial distribution of Bacteria and Archaea and amoA gene copy numbers throughout the water column of the Eastern Mediterranean Sea. ISME J. 3:147-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delong, E. F., D. G. Franks, and A. A. Yayanos. 1997. Evolutionary relationships of cultivated psychrophilic and barophilic deep-sea bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:2105-2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeLong, E. F., C. M. Preston, T. Mincer, V. Rich, S. J. Hallam, N. U. Frigaard, A. Martinez, M. B. Sullivan, R. Edwards, B. R. Brito, S. W. Chisholm, and D. M. Karl. 2006. Community genomics among stratified microbial assemblages in the ocean's interior. Science 311:496-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eloe, E. A., F. M. Lauro, R. F. Vogel, and D. H. Bartlett. 2008. The deep-sea bacterium Photobacterium profundum SS9 utilizes separate flagellar systems for swimming and swarming under high-pressure conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:6298-6305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finn, R. D., J. Mistry, B. Schuster-Bockler, S. Griffiths-Jones, V. Hollich, T. Lassmann, S. Moxon, M. Marshall, A. Khanna, R. Durbin, S. R. Eddy, E. L. Sonnhammer, and A. Bateman. 2006. Pfam: clans, web tools and services. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:D247-D251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frias-Lopez, J., Y. Shi, G. W. Tyson, M. L. Coleman, S. C. Schuster, S. W. Chisholm, and E. F. Delong. 2008. Microbial community gene expression in ocean surface waters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105:3805-3810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Georlette, D., V. Blaise, T. Collins, S. D'Amico, E. Gratia, A. Hoyoux, J. C. Marx, G. Sonan, G. Feller, and C. Gerday. 2004. Some like it cold: biocatalysis at low temperatures. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 28:25-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giovannoni, S. J., T. B. Britschgi, C. L. Moyer, and K. G. Field. 1990. Genetic diversity in Sargasso Sea bacterioplankton. Nature 345:60-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grzymski, J. J., B. J. Carter, E. F. DeLong, R. A. Feldman, A. Ghadiri, and A. E. Murray. 2006. Comparative genomics of DNA fragments from six Antarctic marine planktonic bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:1532-1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hallam, S. J., K. T. Konstantinidis, N. Putnam, C. Schleper, Y. Watanabe, J. Sugahara, C. Preston, J. de la Torre, P. M. Richardson, and E. F. DeLong. 2006. Genomic analysis of the uncultivated marine crenarchaeote Cenarchaeum symbiosum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:18296-18301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hallam, S. J., T. J. Mincer, C. Schleper, C. M. Preston, K. Roberts, P. M. Richardson, and E. F. DeLong. 2006. Pathways of carbon assimilation and ammonia oxidation suggested by environmental genomic analyses of marine Crenarchaeota. PLoS Biol. 4:e95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haney, P. J., J. H. Badger, G. L. Buldak, C. I. Reich, C. R. Woese, and G. J. Olsen. 1999. Thermal adaptation analyzed by comparison of protein sequences from mesophilic and extremely thermophilic Methanococcus species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:3578-3583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karner, M. B., E. F. DeLong, and D. M. Karl. 2001. Archaeal dominance in the mesopelagic zone of the Pacific Ocean. Nature 409:507-510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Konstantinidis, K. T., and E. F. DeLong. 2008. Genomic patterns of recombination, clonal divergence and environment in marine microbial populations. ISME J. 2:1052-1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Konstantinidis, K. T., and J. M. Tiedje. 2004. Trends between gene content and genome size in prokaryotic species with larger genomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:3160-3165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lauro, F. M., and D. H. Bartlett. 2008. Prokaryotic lifestyles in deep sea habitats. Extremophiles 12:15-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lawrence, J. 2003. When ELFs are ORFs, but don't act like them. Trends Genet. 19:131-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin-Cuadrado, A. B., P. Lopez-Garcia, J. C. Alba, D. Moreira, L. Monticelli, A. Strittmatter, G. Gottschalk, and F. Rodriguez-Valera. 2007. Metagenomics of the deep Mediterranean, a warm bathypelagic habitat. PLoS ONE 2:e914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Methe, B. A., K. E. Nelson, J. W. Deming, B. Momen, E. Melamud, X. Zhang, J. Moult, R. Madupu, W. C. Nelson, R. J. Dodson, L. M. Brinkac, S. C. Daugherty, A. S. Durkin, R. T. DeBoy, J. F. Kolonay, S. A. Sullivan, L. Zhou, T. M. Davidsen, M. Wu, A. L. Huston, M. Lewis, B. Weaver, J. F. Weidman, H. Khouri, T. R. Utterback, T. V. Feldblyum, and C. M. Fraser. 2005. The psychrophilic lifestyle as revealed by the genome sequence of Colwellia psychrerythraea 34H through genomic and proteomic analyses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:10913-10918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ochman, H. 2002. Distinguishing the ORFs from the ELFs: short bacterial genes and the annotation of genomes. Trends Genet. 18:335-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raes, J., J. O. Korbel, M. J. Lercher, C. von Mering, and P. Bork. 2007. Prediction of effective genome size in metagenomic samples. Genome Biol. 8:R10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rocha, E. P., J. M. Smith, L. D. Hurst, M. T. Holden, J. E. Cooper, N. H. Smith, and E. J. Feil. 2006. Comparisons of dN/dS are time dependent for closely related bacterial genomes. J. Theor. Biol. 239:226-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rost, B. 1999. Twilight zone of protein sequence alignments. Protein Eng. 12:85-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rusch, D. B., A. L. Halpern, G. Sutton, K. B. Heidelberg, S. Williamson, S. Yooseph, D. Wu, J. A. Eisen, J. M. Hoffman, K. Remington, K. Beeson, B. Tran, H. Smith, H. Baden-Tillson, C. Stewart, J. Thorpe, J. Freeman, C. Andrews-Pfannkoch, J. E. Venter, K. Li, S. Kravitz, J. F. Heidelberg, T. Utterback, Y. H. Rogers, L. I. Falcon, V. Souza, G. Bonilla-Rosso, L. E. Eguiarte, D. M. Karl, S. Sathyendranath, T. Platt, E. Bermingham, V. Gallardo, G. Tamayo-Castillo, M. R. Ferrari, R. L. Strausberg, K. Nealson, R. Friedman, M. Frazier, and J. C. Venter. 2007. The Sorcerer II Global Ocean Sampling expedition: northwest Atlantic through eastern tropical Pacific. PLoS Biol. 5:e77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sander, C., and R. Schneider. 1991. Database of homology-derived protein structures and the structural meaning of sequence alignment. Proteins 9:56-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Somero, G. N. 1992. Adaptations to high hydrostatic pressure. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 54:557-577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suyama, M., D. Torrents, and P. Bork. 2006. PAL2NAL: robust conversion of protein sequence alignments into the corresponding codon alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:W609-W612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tatusov, R., N. Fedorova, J. Jackson, A. Jacobs, B. Kiryutin, E. Koonin, D. Krylov, R. Mazumder, S. Mekhedov, A. Nikolskaya, B. S. Rao, S. Smirnov, A. Sverdlov, S. Vasudevan, Y. Wolf, J. Yin, and D. Natale. 2003. The COG database: an updated version includes eukaryotes. BMC Bioinformatics 4:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Nimwegen, E. 2003. Scaling laws in the functional content of genomes. Trends Genet. 19:479-484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Venter, J. C., K. Remington, J. F. Heidelberg, A. L. Halpern, D. Rusch, J. A. Eisen, D. Wu, I. Paulsen, K. E. Nelson, W. Nelson, D. E. Fouts, S. Levy, A. H. Knap, M. W. Lomas, K. Nealson, O. White, J. Peterson, J. Hoffman, R. Parsons, H. Baden-Tillson, C. Pfannkoch, Y. H. Rogers, and H. O. Smith. 2004. Environmental genome shotgun sequencing of the Sargasso Sea. Science 304:66-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vezzi, A., S. Campanaro, M. D'Angelo, F. Simonato, N. Vitulo, F. M. Lauro, A. Cestaro, G. Malacrida, B. Simionati, N. Cannata, C. Romualdi, D. H. Bartlett, and G. Valle. 2005. Life at depth: Photobacterium profundum genome sequence and expression analysis. Science 307:1459-1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.von Mering, C., L. J. Jensen, M. Kuhn, S. Chaffron, T. Doerks, B. Kruger, B. Snel, and P. Bork. 2007. STRING 7—recent developments in the integration and prediction of protein interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:D358-D362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang, F., J. Wang, H. Jian, B. Zhang, S. Li, X. Zeng, L. Gao, D. H. Bartlett, J. Yu, S. Hu, and X. Xiao. 2008. Environmental adaptation: genomic analysis of the piezotolerant and psychrotolerant deep-sea iron reducing bacterium Shewanella piezotolerans WP3. PLoS ONE 3:e1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Whitman, W. B., D. C. Coleman, and W. J. Wiebe. 1998. Prokaryotes: the unseen majority. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:6578-6583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu, K., and B. G. Ma. 2007. Comparative analysis of predicted gene expression among deep-sea genomes. Gene 397:136-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang, Z. 2007. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24:1586-1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yayanos, A. A. 1995. Microbiology to 10,500 meters in the deep sea. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 49:777-805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zeldovich, K. B., I. N. Berezovsky, and E. I. Shakhnovich. 2007. Protein and DNA sequence determinants of thermophilic adaptation. PLoS Comput. Biol. 3:e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.