Abstract

There are contradictory literature reports on the role of verotoxin (VT) in adherence of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 (O157 EHEC) to intestinal epithelium. There are reports that putative virulence genes of O island 7 (OI-7), OI-15, and OI-48 of this pathogen may also affect adherence in vitro. Therefore, mutants of vt2 and segments of OI-7 and genes aidA15 (gene from OI-15) and aidA48 (gene from OI-48) were generated and evaluated for adherence in vitro to cultured human HEp-2 and porcine jejunal epithelial (IPEC-J2) cells and in vivo to enterocytes in pig ileal loops. VT2-negative mutants showed significant decreases in adherence to both HEp-2 and IPEC-J2 cells and to enterocytes in pig ileal loops; complementation only partially restored VT2 production but fully restored the adherence to the wild-type level on cultured cells. Deletion of OI-7 and aidA48 had no effect on adherence, whereas deletion of aidA15 resulted in a significant decrease in adherence in pig ileal loops but not to the cultured cells. This investigation supports the findings that VT2 plays a role in adherence, shows that results obtained in adherence of E. coli O157:H7 in vivo may differ from those obtained in vitro, and identified AIDA-15 as having a role in adherence of E. coli O157:H7.

Escherichia coli O157:H7 is the prototypical enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) strain and is the most common serotype associated with large outbreaks and sporadic cases of hemorrhagic colitis (HC) and hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS) (25). It is well established that EHEC O157:H7 can colonize the intestine of humans and animals and that adherence to intestinal epithelial cells occurs through the formation of attaching-and-effacing (AE) lesions, which is a critical early step in infection. Some researchers have suggested that EHEC uses fimbriae to make the initial contact with epithelial cells, prior to intimate attachment mediated by locus of enterocyte effacemen-encoded proteins (15). Several potential adherence factors of EHEC O157:H7 have been described, but only the outer membrane protein intimin has been demonstrated to play a role in intestinal colonization in animal models (16). Intimin mediates the intimate adherence component of the AE lesion by binding to the translocated intimin receptor Tir, resulting in close attachment of the bacteria to the host cell membrane (17). Intimin can also bind to β1 integrins and nucleolin on host cells (9, 36). Severe damage due to infection with EHEC is attributable to the cytotoxic verotoxin (VT), which damages epithelial and endothelial cells, leading to bloody diarrhea and HUS (16). Several investigators have reported that VT does not play a role in colonization of the intestine (2, 4, 34). However, Robinson et al. (30) reported recently that VT enhances adherence to epithelial cells and colonization of the mouse intestine by E. coli O157:H7. Therefore, the present study examined the involvement of VT in adherence in vitro and in vivo.

Several putative virulence genes have been identified in O islands (OIs) in EHEC O157:H7 strain EDL 933 (26), including those encoding Iha and AIDA-I in OI-43/48, AIDA-I in OI-15, and a ClpB chaperone protein and a putative macrophage toxin in OI-7 (26, 27). OI-7 also contains many unknown open reading frames (ORFs) whose function in the pathogenesis of EHEC O157:H7 has not been investigated. Iha, an adherence-conferring outer membrane protein similar to IrgA (the product of iron-regulated gene A) (38), is a virulence factor in uropathogenic E. coli strain CFT073 (14). AIDA-I, encoded by aidA, was first identified in EPEC and confers the capacity for diffuse adhesion of the bacteria to epithelial cells (1). AIDA-I-like adhesins from OI-15 and OI-43/48 show 55% and 68% homology, respectively, to the AIDA-I of EPEC (26, 27). All three AIDA proteins show characteristics of an autotransporter membrane protein with a β-barrel structure (20), which is exposed at the surface of the bacteria (13). These observations suggest that the two homologs of AIDA-I may also function as adhesins in EHEC O157:H7; however, the roles of the AIDA-I-like adhesins in EHEC have yet to be determined.

EHEC O157:H7 has been isolated from pigs, and conventional pigs are a permissive host and therefore a potential reservoir for human infection with EHEC O157:H7 (8). One recent family outbreak was associated with pork salami (3). Pigs are highly relevant models for the study of virulence of EHEC O157:H7 in humans and have been extensively used to characterize putative virulence factors and to investigate the pathogenesis of EHEC O157:H7 and other verotoxigenic E. coli strains (6, 11, 21). The present study was designed to examine VT2-negative mutants, OI-7 deletions, and aidA knockouts from OI-15 and OI-48 of EHEC O157:H7 in vitro and in the pig intestines for their roles in adherence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1. Mutant strains were constructed in EHEC O157:H7 strain 86-24.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| E. coli strain or plasmid | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| 86-24NS | EHEC O157:H7 strain 86-24 | 40 |

| 86-24NR | EHEC O157:H7 strain 86-24 Nalr | This study |

| SM10(λpir) | Kmr; RP4-2-Tc::Mu, broad-host-range conjugation strain; Tra functions conferred by chromosomal RP4 | 7 |

| DH5α-λpir | F−hsdR17 thi-1 gyrA Δ(lacZYA-argF) supE44 recA1[Ν80dΔ(lacZ)M15] relA λpir | 7 |

| 86-24NSΔaidA48 | 86-24ΔaidA48::Kan (OI-48) | This study |

| 86-24NSΔaidA15 | 86-24ΔaidA15::Gm (OI-15) | This study |

| 86-24NSΔaidA15(pA15) | 86-24ΔaidA15 containing pA15 | This study |

| 86-24NSΔescN | 86-24ΔescN::Gm (OI-48) | This study |

| 86-24NSK21 | 86-24 ΔZ0244-Z0250::Kan (OI-7) Z0250 putative macrophage toxin | This study |

| 86-24NSGm3 | 86-24 ΔZ02550-Z0253::Gm (OI-7) | This study |

| 86-24NSGm0254 | ΔZ0254::Gm (OI-7) putative protease, Hsp | This study |

| 86-24NSGm31 | 86-24 ΔZ0255-Z0260::Gm (OI-7) | This study |

| 86-24NSGm5 | 86-24 ΔZ0260-Z0266::Gm (OI-7) | This study |

| 86-24NSGm6 | 86-24 ΔZ0266-Z0268::Gm (OI-7) VgrG protein, Rhs element associated | This study |

| 86-24NSGm56 | 86-24 ΔZ0260-Z0268::Gm (OI-7) | This study |

| 86-24NSK2D | 86-24 ΔZ0268-Z0276::Kan (OI-7) Rhs element associated, putative receptor | This study |

| 86-24NRΔvt2 | 86-24 vt2A::Gm Nalr | This study |

| 86-24NRΔvt2(pVT2) | 86-24NRΔvt2 containing pVT2 | This study |

| 86-24NSΔvt2-1 | 86-24 vt2A::Gm | This study |

| 86-24NSΔvt2-2 | 86-24 vt2A::Gm | This study |

| 86-24NSΔvt2(pVT2) | 86-24Δvt2-1 containing pVT2 | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUCGM | Template plasmid for Gm resistance | 33 |

| pUCKan | Template plasmid for Kan resistance | 22 |

| pBAD-TOPO | Cloning expression vector PBAD; Apr | Invitrogen |

| pKM208 | Red and gam expressed from Ptac; AprlacI; IPTGa inducible | 24 |

| pA15 | pBAD-TOPO containing aidA15 (OI-15) | This study |

| pVT2 | pBAD-TOPO containing vt2 genes | This study |

| pRE107 | Mobilizable suicide vector; Apr | 7 |

| pRE107-vt2 | pRE107 containing vt2 mutation cassette | This study |

| pGEM-T Easy | TA cloning vector; Apr | Promega |

| pGEM-vt2 | pGEM-T Easy containing vt2 mutation cassette Gmr inserted in the A subunit | This study |

IPTG, isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside.

Mutant generation. (i) Generation of vt2 isogenic mutants.

Construction of vt2-negative mutants of EHEC O157:H7 strains 86-24NR and 86-24NS was accomplished by allelic exchange (10) and by phage λ-Red mediated recombination, respectively. For allelic exchange, primers vt2-F03-SalI and vt2-R03-SphI (Table 2) were used to amplify a fragment of 1,216 bp from position 14 of Z1464 (encoding vt2 A subunit) to position 258 of Z1465 (encoding vt2 B subunit) from wild-type EHEC O157:H7 strain 86-24 using the Expand high-fidelity PCR system (Roche Diagnostics). The amplicon was cloned into pGEM-T Easy (Promega, Madison, WI). A gentamicin (Gm) resistance gene (855 bp) from pUC-GM was released with SmaI and inserted into the unique Eco47III site of the vt2 A subunit gene at position 418 of the cloned fragment in pGEM-T Easy, resulting in pGEM-vt2 with a mutation cassette of 2,071 bp. The cassette was subcloned into the SalI and SphI sites in the suicide vector pRE107, creating pRE107-vt2. Donor (E. coli SM10 λpir containing pRE107-vt2) and recipient (EHEC O157:H7 strain 86-24NR) were mated, and transconjugants were selected on tryptic soy agar plates with nalidixic acid (50 μg/ml) and Gm (20 μg/ml). Colonies that appeared were tested for susceptibility to sucrose and ampicillin. A sucrose-resistant, ampicillin-sensitive clone was examined by PCR using primers vt2-F03 and vt2-R03 (Table 2), generating an amplicon of 2,071 bp for the mutant with an insertion while generating an amplicon of 1,216 bp for the wild-type strain (data not shown). Sequencing of the 2,071-bp amplicon from the mutant confirmed the insertion of the Gm gene, and the mutant was named 86-24NRΔvt2. To complement this mutation, plasmid pVT2 was introduced into 86-24NRΔvt2, generating a complemented mutant strain, 86-24NRΔvt2(pVT2) (Tables 1 and 2). pVT2 was generated by cloning of the amplicon (enclosing the complete vt2 A and B subunits plus a 409-bp sequence upstream of the vt2 gene) with primers vt2-F06B and vt2-R06 into the expression vector pBAD-TOPO. The loss and restoration of VT production from the mutant and complemented strains were determined by a Vero cell cytotoxicity assay (VCA) and by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (see below).

TABLE 2.

Primers used for PCR

| Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Function(s) |

|---|---|---|

| vt2-F03-SalI | gtcgacTATTTAAATGGGTACTGTGCCTa | PCR for cloning |

| vt2-R03-SphI | gcatgcAAACTGCACTTCAGCAAATCCGb | PCR for cloning |

| vt2-F03 | TATTTAAATGGGTACTGTGCCT | Confirmation of vt2 mutagenesis |

| vt2-R03 | AAACTGCACTTCAGCAAATCCG | Confirmation of vt2 mutagenesis |

| vt2-F06B | CACCCAGAATGTAGTCAGTCAGAACc | For vt2 complementation |

| vt2-R06 | CCCTGACAACATCATAGTGT | For vt2 complementation |

| aidA48-KF | GAATCTCTTCATCATGCAGAACGGAATTGCACACAACAGACTGACTAACTAGGAGGAATAA | For aidA48 mutagenesis |

| aidA48-KR | GAAATCGTATTTCCGGGATACCGTATAATCAGAAAGTCATATTCATTATTCCCTCCAGGTAC | For aidA48 mutagenesis |

| aidA48-LF | TGATGAGCGCCAGACCAATC | Confirmation of aidA48 mutagenesis |

| aidA48-RR | TAATATGCGCCTGTAGTGACTG | Confirmation of aidA48 mutagenesis |

| aidA15-GF | TGATGAATAAAATATATCGGCTAAAGTGGAACAGGTCCCGTCGAGCTCGAATTGACATAAG | For aidA15 mutagenesis and confirmation |

| aidA15-GR | AACCATTGCAGAGGTGTCATTATATCCCCTATCGGCAACCTGCGTTGTGACAATTTACCGAA | For aidA15 mutagenesis and confirmation |

| aidA15-F2B | CACCGATATTCTTGACCAGTACGAG | For aidA15 complementation |

| aidA15-R2 | AACACTCAAATCATGCGAAGC | For aidA15 complementation |

| escN-GF | ACGAATAGATAAAATTCTGTCCAACATACTCAGGCAACCACTCGTTGTGACAATTTACCGAA | For escN mutagenesis |

| escN-GR | AATATCGAACTTAAAGTATTAGGAACGGTAAATGATTTCAGACGAGCTCGAATTGACATAAG | For escN mutagenesis |

| escN-Fm | GATAAAATTCTGTCCAACATAC | Confirmation of escN mutagenesis |

| escN-Rm | TCGAACTTAAAGTATTAGGAAC | Confirmation of escN mutagenesis |

| K21-LF | GAACTATCAAATGACCATGTTACGGAAGCGCAACTGTTTAATTGACTAACTAGGAGGAATAA | For K21 mutagenesis and confirmation |

| K21-RR | GCCAGCATCTTCACTGCCAGTTACCGGTTTACGTGGTACTGATCATTATTCCCTCCAGGTAC | For K21 mutagenesis and confirmation |

| Gm3-F | GAACGGGTTATCTTCCGTGTCGGTATGCACACGGTAGGTCATCGTTGTGACAATTTACCGAA | For Gm3 mutagenesis |

| Gm3-R | ACGAGTCCGTCACAAAGGATGAAACGGTTTTATGAGCAGGTTCGAGCTCGAATTGACATAAG | For Gm3 mutagenesis |

| Gm3-Fm | AACGGGTTATCTTCCGTGTC | Confirmation of Gm3 mutagenesis |

| Gm3-Rm | CCGTCACAAAGGATGAAACG | Confirmation of Gm3 mutagenesis |

| Gm0254-LF | AACCTGCTCATAAAACCGTTTCATCCTTTGTGACGGACTCGTCGAGCTCGAATTGACATAAG | For Gm0254 mutagenesis and confirmation |

| Gm0254-RR | ATAAGGACGTTTATGATCCAGATTGATCTTCCCACGCTGGTACGTTGTGACAATTTACCGAA | For Gm0254 mutagenesis and confirmation |

| Gm31-LF | AATTCCAGCAGATCCTGGTAACGTTTGGGTTCACGGATCAGCGAGCTCGAATTGACATAAG | For Gm31 mutagenesis and confirmation |

| Gm31-RR | TTGAAAGTTTCAGCCATCAGATGGAATACAGCCGGAAGCGGCGTTGTGACAATTTACCGAA | For Gm31 mutagenesis and confirmation |

| Gm5-LF | TTCAGCGCGTCCGTATCCAGTAATGACAGATAATTCAGGTTCCGAGCTCGAATTGACATAAG | For Gm5 mutagenesis and confirmation |

| Gm5-RR | GGTAGTGAAATAATGCTCCTGTTTGCCTTCCACAGAGGTACGCGTTGTGACAATTTACCGAA | For Gm5 mutagenesis and confirmation |

| Gm6-LF | TGGTCTCCTTTCATCTGAACCAGTCACTCTCTTCGCTTTTTTCGAGCTCGAATTGACATAAG | For Gm6 mutagenesis and confirmation |

| Gm6-RR | TATATGTTCAATAGGATTGAGTGGGTACTGATACAGGTTCCACGTTGTGACAATTTACCGAA | For Gm6 mutagenesis and confirmation |

| K2D-LF | TGGAACCTGTATCAGTACCCACTCAATCCTATTGAACATATATGACTAACTAGGAGGAATAA | For K2D mutagenesis and confirmation |

| K2D-RR | TTCAGAAAGGGATGTTTAGTGTGCTGAGCGAGAGTTAAATAATCATTATTCCCTCCAGGTAC | For K2D mutagenesis and confirmation |

Lowercase letters show SalI site.

Lowercase letters show SphI site.

Underlined letters show 5′ overhang required for directional cloning into pBAD-TOPO.

Two vt2-negative mutants of the nalidixic acid-sensitive (NS) strain were generated by the phage λ-Red-mediated recombination system as described below. The PCR amplicon obtained from pRE107-vt2 with primers vt2-F03 and vt2-R03 was electroporated into EHEC O157:H7 strain 86-24 cells containing pKM208. Two vt2-negative mutant strains were created in separate experiments and were named 86-24NSΔvt2-1 and 86-24NSΔvt2-2. Possession of an in-frame insertion was confirmed by sequencing and PCR (data not shown). The complemented mutant 86-24NSΔvt2(pVT2) was created by introduction of pVT2 into 86-24NSΔvt2-1.

(ii) Construction of isogenic mutants of OI genes by the λ-Red-mediated recombination system.

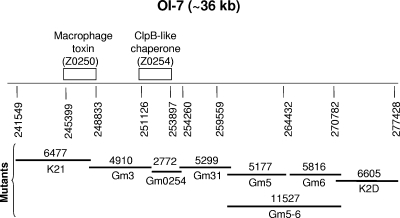

Deletions of genes for the AIDA-like adhesins of OI-48 (AIDA-48) and OI-15 (AIDA-15), escN of the locus of enterocyte effacement, and segments of OI-7 were generated through the phage λ-Red-mediated recombination system as described previously (24). Briefly, competent EHEC O157:H7 strain 86-24 cells containing pKM208 were electroporated with PCR products. The PCR products were generated with primers containing 40- to 42-nucleotide overhangs at the 5′ end homologous to the gene to be replaced and 20 nucleotides at the 3′ end targeting the drug resistance genes derived from either the template plasmid pUCGM (carrying a Gm resistance cassette) or pUCKan (carrying a kanamycin [Kan] resistance cassette) (Tables 1 and 2). After electroporation, cells were incubated at 37°C overnight with shaking and plated on medium containing either 20 μg/ml Gm or 50 μg/ml Kan. The resulting colonies were confirmed for absence of the genes by PCR using primers flanking the deleted region. Positive clones with gene deletions were tested for ampicillin sensitivity for the loss of pKM208. Mutant strains 86-24NSΔaidA48, 86-24NSΔaidA15, 86-24NSΔescN, 86-24NSK21, 86-24NSGm3, 86-24NSGm0254, 86-24NSGm31, 86-24NSGm5, 86-24NSGm6, 86-24NSGm5-6, and 86-24NSK2D were generated using the primer pairs listed in Table 2. The whole OI-7 was deleted by the eight overlapping deletion mutants (Fig. 1). To complement the mutant 86-24NSΔaidA15, wild-type aidA15 (gene from OI-15) was amplified by PCR with primers aidA15-F2B/aidA15-R2 and cloned into the expression vector pBAD-TOPO (behaving as a low-copy-number plasmid under uninduced conditions), resulting in pA15. The latter was then electroporated into 86-24ΔaidA15, yielding 86-24ΔaidA15(pA15) (Tables 1 and 2).

FIG. 1.

Scheme for creation of eight deletion mutants that covered the entire OI-7 of EHEC O157:H7 strain 86-24NS. The deletions were made with the phage λ-Red system. Each deletion mutant is shown with its name and size in base pairs. Mutant K21 contains a deletion of the gene for a putative macrophage toxin (Z0250), and mutant Gm0254 represents a major deletion of Z0254, encoding a putative ClpB-like chaperone protein.

In vitro adherence assay.

Effects of the mutants on adherence in vitro were evaluated by comparison with adherence of the wild-type bacteria to HEp-2 and IPEC-J2 cells. The bacteria were grown for 16 to18 h in 3 ml of brain heart infusion (BHI) broth plus 44 mM NaHCO3 (BHIN) in tightly capped 12-ml sterile plastic tubes (Fisher Scientific, Nepean, Ontario, Canada) without shaking. The density of all bacterial cultures was adjusted photometrically so that cultures contained approximately 5 × 108 CFU/ml prior to their use in the assay.

HEp-2 (ATCC CCL23) cells were maintained in Eagle's minimal essential medium (EMEM) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The IPEC-J2 pig jejunal epithelial cells (a gift from Joshua Gong of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada) were maintained in Dulbecco's minimal essential medium (Invitrogen). Both media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin (100 IU/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). HEp-2 and IPEC-J2 cell adherence assays were conducted as previously described (31), with some modifications. Briefly, approximately 2 × 105 HEp-2 or IPEC-J2 cells per well were dispensed in six-well cell culture plates (Corning, NY) and grown in EMEM or Dulbecco's minimal essential medium, respectively, overnight in the presence of 5% CO2. For the adherence assay, cell monolayers at ∼50% confluence were washed and reconstituted with fresh EMEM (800 μl per well) without antibiotics. A 20-μl volume (approximately 107 bacteria) of an overnight culture of each strain was added individually to sets of duplicate wells. After incubation for 6 h at 37°C in 5% CO2 with a medium change at 3 h, the plates were washed with phosphate-buffered saline to remove unbound bacteria, fixed with 70% methanol, stained with 1:40 Giemsa stain (Sigma), and examined by light microscopy. Adherence was quantified by examining 100 consecutive cells per well and recording the percentage of HEp-2 or IPEC-J2 cells with clusters of 5 to 9, 10 to 19, and ≥20 bacteria. The percentage of cells with at least five adherent bacteria per cell was calculated as a measure of total adherence. Data are expressed as the means of at least three separate experiments ± standard deviation (SDs).

VT detection by the Vero cell assay and ELISA.

VT2 production was determined by the following methods. Overnight bacterial cultures were subcultured into two tubes with 5 ml fresh Luria-Bertani broth (LB) and grown with shaking at 37°C to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.6 (mid-log phase). Mitomycin C induction and whole-cell lysate preparation were performed according to the method of Ritchie et al. (29). The VT concentrations in each sample of culture supernatant and sonicated whole-cell lysate were determined by ELISA and by VCA (18). The ELISA was performed as described previously (5) with VT concentrations determined from a standard curve generated with purified VT2. For the VCA, 100 μl of serially diluted samples was mixed with 100 μl of Vero cell suspension (4 × 105 cells/ml) in 96-well plates and incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. After 3 days of incubation, the plates were stained with crystal violet and were examined visually to determine the 50% cytotoxic dose (CD50), the dilution at which half of the cells had detached from the monolayer. The titer of a preparation was the number of CD50s per ml of the preparation.

Pig gut loop experiments.

The mutants were tested in ligated ileal loops of pigs. The experimental protocols and care of the animals were approved by the University of Guelph Animal Care Committee. Bacteria were grown without shaking at 37°C overnight in BHIN, concentrated by centrifugation, and resuspended to a concentration of 5 × 1010 CFU/ml in EMEM containing 10% FBS.

Two or three 12- to 14-day-old female pigs from the same litter were used at a time. The pigs were fed only electrolytes in warm water (Vetoquinol, Lavaltrie, Quebec, Canada) for 24 h before surgery. The pigs were premedicated with a mixture of ketamine (50 mg/ml), xylazine (10 mg/ml), and butorphenol (1 mg/ml), given intramuscularly at 0.2 ml/kg of body weight. About 10 min later, anesthesia was achieved by slow intravenous injection of sodium pentobarbital (55 mg/100 ml). Following cleaning and disinfection of the abdomen, a ventral midline laparotomy was performed aseptically and the distal ileum was exteriorized. Six to eight ligated loops (each about 10 cm long) were created with nylon ligatures in the distal ileum, beginning approximately 10 cm from the ileocecal junction. Each loop was followed by a short intervening segment (2 to 3 cm) that was not inoculated. A 2-ml volume of inoculum containing 1011 CFU of the test organisms was injected into the lumen of the ileal loops with a 25-gauge needle. In each pig, the treatments were assigned randomly: one loop received the positive control of wild-type EHEC strain 86-24 and one loop received the negative-control EMEM with 10% FBS. After inoculation, the ileum was replaced in the abdomen and the laparotomy incision was closed. Immediately following the surgery and at 4-h intervals thereafter, the pigs were injected intramuscularly with butorphenol (Wyeth Canada, St. Laurent, Quebec, Canada) at 0.4 mg/kg body weight. The pigs were euthanized by an overdose of pentobarbital 15 to 16 h after inoculation of the loops, and pieces of the ligated intestine were quickly excised from each loop for histopathology, electron microscopy, and bacteriology. Fluid accumulation in the ileal loops was measured as the volume per loop.

A total of 63 pigs were used in the ligated intestine tests. Comparison of adherence of the mutants and the wild-type parent was based on tests conducted in the same pigs, and data were considered valid when the positive control showed adherent bacterial clusters and the negative control showed no adherent bacterial clusters.

Histological examination, immunoperoxidase staining with anti-O157 antibody, and electron microscopy.

Tissues taken from the loops were fixed immediately in 10% neutral buffered formalin for at least 24 h at room temperature. Additional 4-mm-square pieces were immediately immersed in cacodylate-HCl-buffered glutaraldehyde for possible electron microscopy. The fixed tissues were cut into smaller pieces, and every second piece of tissue was chosen for a total of four pieces from each loop that were processed by routine methods. After the tissue was embedded in paraffin, 1-μm-thick sections were cut and stained with Giemsa stain and with hematoxylin and eosin. All villi in these sections were examined by light microscopy to determine the percentage of villi with adherent bacterial clusters (≥5 bacteria). The score for each treatment was calculated as the mean percentage (±SD) of villi with adherent bacterial clusters for all loops subjected to the treatment. Bacteria seen in these sections were tested for the O157 antigen by indirect immunoperoxidase staining of adjacent sections with anti-O157 antibody (Difco, Detroit, MI) using Histostain (Zymed Laboratories, San Francisco, CA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Selected fixed tissues likely to contain AE lesions as identified by the light microscopic examination were processed for electron microscopy. Thin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined with a 100S transmission electron microscope (JEOL, Japan).

RNA isolation and RT-PCR.

To determine the expression of the plasmid-carried genes for the complemented strains, reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) was performed from bacterial total RNA that was isolated using the RiboPure-Bacteria kit protocol (Ambion, Texas). Briefly, bacteria grown overnight in BHIN at 37°C without shaking were harvested and treated in RNAlater solution (Ambion) overnight. Subsequent RNA isolation and purification and DNase I treatment steps were done according to the manufacturer's protocol. Total RNA from tissue culture cells was isolated with an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) according to the manufacturer's instructions. All the RNAs that were treated with DNase I were confirmed free of DNA contamination as determined by PCR using RNA as template. Total RNA concentration was determined with a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE), and RNA integrity was verified by visualization on an agarose gel.

First-strand cDNA was synthesized from the DNase I-treated total RNA using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase with 100 ng of random primer pd(N)9 for bacterial RNA or with olig(dT)12 for RNA from tissue-cultured cells according to the procedures recommended by the supplier (Invitrogen). Reverse-transcribed cDNAs were amplified by PCR in a final volume of 50 μl, containing 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate mixture, 10 pmol of each primer as indicated in Table 2, and 2.5 units of Taq DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs, MA). An initial exposure to 94°C for 4 min was followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 55 to 58°C (depending on the primers used) for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 120 s and a final extension step of 10 min at 72°C.

Statistical analysis.

All analyses were performed with SAS for Windows version 8.02 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). The in vitro adherences of the various strains to cultured cells were compared by analysis of variance of the percent adherence of clusters with 5 to 9, 10 to 19, and ≥20 bacteria per cell, as well as the total percent adherence (≥5 adherent bacteria per cell) using PROC GLM. In vivo adherences of the tested strains were compared similarly by analysis of variance of the mean percentage of villi with adherent bacteria (≥5 bacteria per villus) for the total number of loops that were tested. P values of ≤0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

VT2 production by wild-type and mutant O157:H7 EHEC.

Production of VT2 by the NS and NR wild-type O157:H7 EHEC varied markedly, with mean titers in the VCA of 23,040 and 436,906 CD50/ml, respectively. VT2 antigen production, as measured by ELISA, was also considerably higher with 86-24NR than with strain 86-24 NS (data not shown). The three vt2-negative mutants exhibited no cytotoxicity in the VCA and produced little detectable VT antigen in the ELISA (data not shown). The complemented mutants produced low levels of VT2 (1,706 and 5,120 CD50/ml, respectively, for the NS and NR strains), indicating that VT2 was not efficiently produced in strains with the plasmid-carried vt2 compared with the wild type with a chromosomal vt2 gene.

Effect of vt2 gene on adherence of EHEC O157:H7 in vitro.

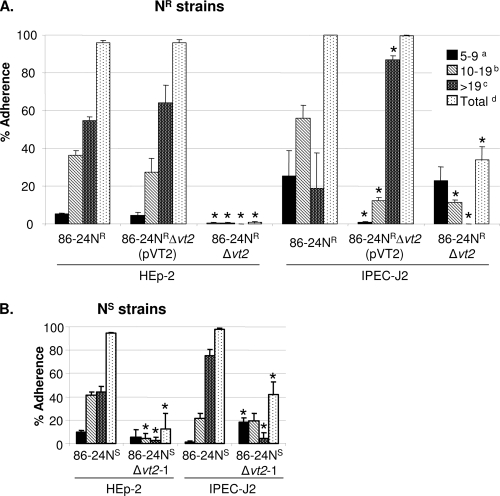

All three vt2 gene insertion mutants, generated independently (Table 1), showed significant reduction in adherence to HEp-2 and IPEC-J2 cells compared with the wild type (Fig. 2). Since data obtained from the in vitro adherence assays were similar for mutants 86-24NSΔvt2-1 and 86-24NSΔvt2-2, only the mutant 86-24NSΔvt2-1 was used for subsequent experiments. For all three vt2 mutants, the reduction in adherence to IPEC-J2 cells was less marked than that for the HEp-2 cells. This is consistent with the tendency of EHEC O157:H7 to adhere more efficiently to IPEC-J2 cells than to HEp-2 cells. Adherence by the complemented mutant 86-24NRΔvt2(pVT2) was restored to the wild-type level (Fig. 2), but this was not the case for the complemented mutant 86-24NSΔvt2(pVT2) (data not shown). Mutant 86-24NSΔescN was used in this study as a control, which caused no adherence to HEp-2 or IPEC-J2 cells.

FIG. 2.

Adherence to HEp-2 and IPEC-J2 cells by wild-type 86-24NR, mutant 86-24NRΔvt2, and complemented mutant 86-24NRΔvt2(pVT2) (A) and by wild-type 86-24NS and mutant 86-24NSΔvt2-1 (B), grown in BHI plus NaHCO3 without shaking. Adherence was quantified by examining 100 cells for each assay and averaged as the mean percentage of cells (+SD) with clusters of 5 to 9 (a), 10 to 19 (c), and >19 (b) adherent bacteria per cell and the total percentage of cells with a cluster of ≥5 adherent bacteria per cell (d). *, P < 0.05.

Effect of vt2 gene on adherence of EHEC O157:H7 in the pig intestine.

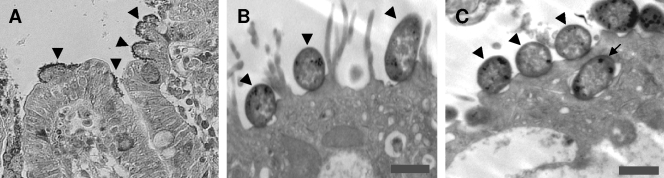

Typical bacterial clusters on the ileal villi under a light microscope are shown in Fig. 3A. Electron microscopy of a sample of sections with adherent bacteria showed typical AE lesions (Fig. 3B), sometimes with invasion (Fig. 3C). The adherent bacteria were confirmed to be O157 by immunohistochemistry (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

(A) Clusters of adherent bacteria associated with the villi of pig ileal loops inoculated with wild-type EHEC O157:H7 strain 86-24NS, grown in BHI plus NaHCO3 without shaking. Adherence was quantified as the percentage of villi that had clusters of ≥5 adherent bacteria per villus. Arrowheads point to clusters of bacteria. The sections were stained with Giemsa stain. Magnification, ×200. (B and C) Transmission electron micrographs of AE lesions in pig ileal loops inoculated with wild-type EHEC O157:H7 strain 86-24NS. Arrowheads show bacteria intimately adherent to epithelial cells. The arrow shows bacterial invasion of the epithelium. Bars, 1 μm.

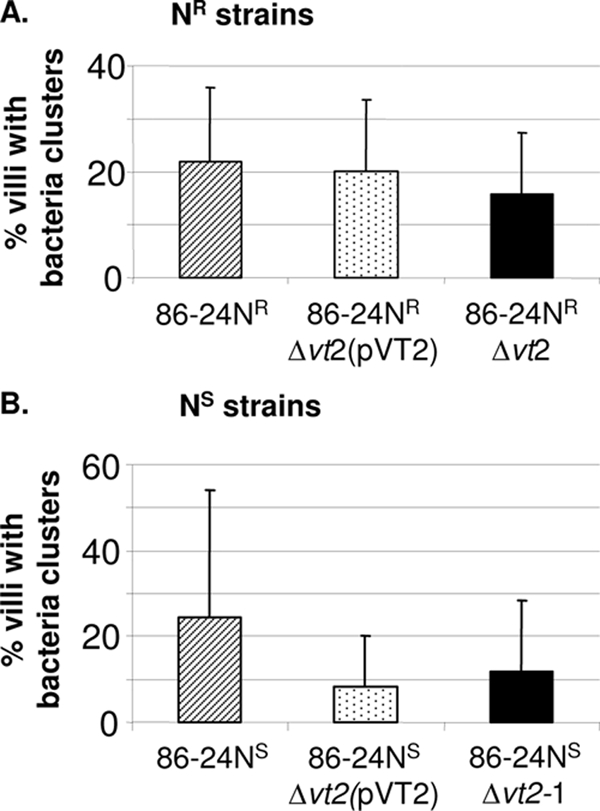

Initial data obtained with cultures grown in LB with shaking showed that in five pigs the average percentage of villi with clusters of 86-24NSΔvt2-1 was 0.93% ± 1.3%, significantly lower than the level of 7.14% ± 3.7% for the wild-type 86-24NS (P = 0.0072). Subsequent tests were all done with static cultures in BHIN, because it was later shown that cultures grown without shaking in BHIN caused the most extensive intimate adherence of bacteria in ligated ileal loops. Seven pigs were inoculated with the bacteria grown without shaking in BHIN and showed 14.9% ± 16.5% of the villi with adherent bacterial clusters in loops inoculated with the mutant, significantly lower than the 39.1% ± 19.6% for the wild-type organism (Table 3). To test the effect of vt2 complementation, strains 86-24NS, 86-24NSΔvt2-1, and 86-24NSΔvt2(pVT2) were evaluated in ileal loops of three pigs, only two of which yielded valid data (Fig. 4). Adherence of the mutant was less than that of the wild type, but the difference was not significant and there was no evidence of complementation. Since complementation of the mutant 86-24NRΔvt2 had restored the adherence phenotype of the wild-type strain in in vitro assays, the complemented strain 86-24NRΔvt2(pVT2) was then evaluated in ileal loops in five pigs together with the corresponding wild-type and mutant strains. Valid data were obtained from three pigs, which showed that there was a reduction in adherence of the mutant and that adherence of the complemented mutant was greater than that of the mutant, but the differences in adherence were not significant (Fig. 4). The control mutant 86-24NSΔescN caused almost no adherence to the villi in the pig ligated intestines (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Frequency of adherence in pig ileal loops induced by mutants and wild-type EHEC O157:H7 strain 86-24NS grown in BHI plus NaHCO3 without shakinga

| Strain | No. of loops testedb | No. of loops with clusters of bacteriac | Mean (±SD) % of villi with clusters of bacteriad | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 86-24NSΔvt2-1 | 9 | 7 | 14.9 ± 16.5 (39.1 ± 19.6) | 0.027 |

| 86-24NSΔaidA15 | 9 | 8 | 10.7 ± 4.2 (34 ± 16.6) | 0.0018 |

| 86-24NSΔaidA48 | 6 | 6 | 30.4 ± 18.4 (32.9 ± 18.9) | 0.8204 |

| 86-24NSK21 | 6 | 5 | 27.1 ± 11.8 (28.6 ± 15.5) | 0.869 |

| 86-24NSGm0254 | 6 | 4 | 15.7 ± 7.3 (30.3 ± 10.9) | 0.0681 |

| 86-24NSΔescN | 16 | 6 | 3.0 ± 2.44 (44.8 ± 24.9) | 0.0022 |

| Total | 52 | 36 | NAe | NA |

All inocula consisted of a dose of 1011 CFU.

The treatments that were being compared were done in the same pigs.

Number of loops with valid data.

Values in parentheses are those for the wild-type strain in each comparison.

NA, not applicable.

FIG. 4.

Effect of adherence in pig ileal loops associated with introducing a plasmid-carried copy of the vt2 gene into the vt2-negative mutants. The bacteria were grown in BHI plus NaHCO3 without shaking, and adherence was quantified as the percentage of villi with clusters of ≥5 adherent bacteria per villus (mean + SD).

Effect of AIDA-like adhesins of OI-15 and OI-48 on adherence.

aidA genes are found in OI-43/48 and OI-15 (26). OI-48 is identical to OI-43, and some strains contain both OIs. PCR involving OI junction primers demonstrated that strain 86-24 contained only OI-48 and not OI-43 (data not shown). aidA15 and aidA48 are named for the genes encoding AIDA-I-like proteins in OI-15 and -48, respectively. OI-15 contains only one ORF. Mutants 86-24NSΔaidA15 and 86-24NSΔaidA48 (Table 1) showed no significant difference in their capacities to adhere to the HEp-2 and IPEC-J2 cells compared with the wild-type strain (data not shown).

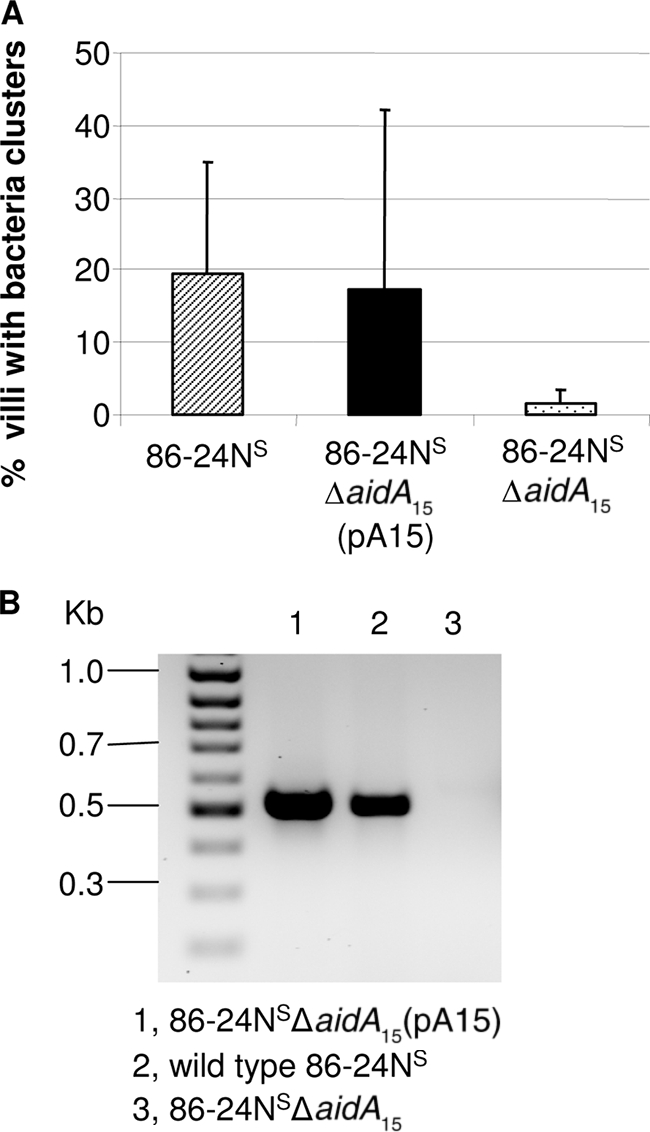

For mutant 86-24NSΔaidA15, grown initially in LB with shaking, loops from four pigs showed that deletion of aidA15 caused a significant reduction in adherence (1.92% ± 3.0%) compared to the wild-type 86-24NS (8.28% ± 3.0%, P = 0.042). Tests with bacteria grown without shaking in BHIN in loops of eight pigs also showed that formation of adherent clusters by the same mutant strain was significantly lower (10.7% ± 4.2%) than that for the wild-type 86-24NS (34% ± 16.6%, Table 3). Tests with the complemented mutant strain 86-24NSΔaidA15(pA15) in ileal loops in three pigs showed that the complemented strain resulted in adherent clusters on an average of 17.1% ± 25.1% of the villi, similar to the value of 19.5% ± 15.3% for the wild-type bacterium, while the value for the mutant strain was 1.7% ± 1.6% (Fig. 5A). Despite this marked reduction for the mutant, the difference from the wild type was not statistically significant (P = 0.0559), likely due to the marked variation in the data for the wild type. Detection of gene transcripts showed that aidA15 was efficiently produced in the complemented 86-24NSΔaidA15(pA15) while no transcripts were detected for the mutant strain 86-24NSΔaidA15 (Fig. 5B). The deletion of aidA48 did not result in any significant difference in bacterial adherence between the mutant and the wild type (Table 3).

FIG. 5.

(A) Effect of complementation of 86-24NSΔaidA15 on adherence in pig ileal loops inoculated with bacteria grown in BHI plus NaHCO3 without shaking. Adherence was quantified as the percentage of villi with clusters of ≥5 adherent bacteria per villus (mean + SD). (B) RT-PCR for the transcripts of aidA15 for the complement and mutant strains grown in BHI plus NaHCO3 without shaking with primers 15aidA-F and 15aidA-R (expected size, 518 bp).

Effect of OI-7 on adherence.

None of the eight mutants with overlapping deletions in OI-7 (Fig. 1) showed any significant difference from the wild type in their capacity to adhere to the HEp-2 and IPEC-J2 cells (data not shown). Mutant 86-24NSK21, which encompasses deletions of seven ORFs (Z0244 to Z0250) including a putative macrophage toxin (Z0250), and mutant 86-24NSGm0254, which represents a deletion of Z0254 encoding a putative ClpB-like protease/hsp (heat shock protein) (26), were evaluated for their adherence in the ileal loops. In four loops, 86-24NSGm0254 induced adherence to 15.7% ± 7.3% of the villi, lower than the 30.3% ± 10.9% for the wild-type 86-24NS. However, the difference was not significant (Table 3). Deletion of Z0244 to Z0250 (strain 86-24NSK21) did not influence adherence (Table 3).

Effects of the mutations on fluid accumulation in ligated ileal loops.

No significant difference in fluid accumulation was observed in ileal loops inoculated with mutants compared with the loops inoculated with the wild-type strain.

DISCUSSION

VT is well established as a major virulence factor of EHEC O157:H7 that plays a central role as a toxin in HUS and HC (39), but its role in adherence is controversial (4). It is only recently that evidence supported a role for VT in adherence to HEp-2 cells and in colonization of the intestine of mice; this enhanced colonization correlated with a VT-induced increase in nucleolin, a receptor for intimin on the host epithelial cells (30). VT could also facilitate colonization indirectly by inhibition of the activation and proliferation of lymphocytes (23). This modulation of the host immune response could affect pathogen-host interaction in favor of colonization by the pathogen (37). VT was reported to bind to Gb3 on Paneth cells in the crypt intestinal epithelia of human biopsy specimens (32). This binding could have an inhibitory effect on antibacterial peptide secretion, as has been described for Shigella spp., thereby promoting bacterial colonization (12, 32).

The present study showed that inactivation of VT2 caused a marked decrease on adherence of EHEC O157:H7 strain 86-24 to both HEp-2 and IPEC-J2 epithelial cells. This reduction in adherence to cultured cells by mutant 86-24NRΔvt2, generated by allele exchange, was restored to the wild-type level by introduction of the wild-type vt2 genes in a plasmid (Fig. 2). But this was not the case for mutant 86-24NSΔvt2-1, made by the λ-Red recombination system. The failure of complementation for the NS mutant in vitro might be due to inadequate production of VT2 by the complemented strain, which produced a relatively small amount of VT2. It is also possible that secondary mutations might have affected adherence, because the plasmid-encoded λ-Red recombination system is able to generate secondary mutations (24). Complementation was also attempted with the plasmid (pCR2.1) for the NS mutant, but the results were unchanged (data not shown).

It is interesting that the vt2 mutant had similar effects on adherence to both HEp-2 and IPEC-J2 cells. IPEC-J2 cells, originating from pig intestine, do not appear to carry nucleolin or Gb3 synthase, as an in silico search failed to identify homologs of human nucleolin and Gb3 synthase against a porcine (Sus scrofa) genome and expressed sequence tags, and transcripts for Gb3 synthase and nucleolin were not detected by RT-PCR using primers based on human genome sequences. However, transcripts for β1-integrin and Gb4 synthase were detected by RT-PCR in IPEC-J2 cells (data not shown). This suggests that the effect of VT2 on adherence was independent of nucleolin or Gb3. Therefore, β1-integrin, Gb4, and other unidentified factors may be involved in the VT2-mediated effect on adherence to IPEC-J2 cells by O157:H7.

The adherence of the VT2-negative mutant in pig ileal loops was also reduced significantly. Complementation of the NR-vt2-negative strain caused adherence in the pig ileal loops that was similar to that of the wild type (Fig. 4A) but not significantly different from that of the uncomplemented mutant. This might be due to the pig-to-pig variation in response to the strains and to the limited number of valid tests. However, complementation of the NS-vt2-negative mutant failed to restore the adherence to the wild-type level in the loops (Fig. 4B). In addition to the reasons as stated above, this failure of complementation for the NS-vt2-negative mutant might also represent the difference in the regulation of VT production in vivo between the plasmid-carried vt2 genes and chromosomally carried vt2 genes, as VT2 production by the plasmid-carried vt2 genes was only a small fraction of the level of the wild type.

The nucleotide sequences of aidA15 and aidA48 share 37.3% homology in EHEC EDL933. During the mutant generation, primers that targeted either aidA15 or aidA48 were designed so as to be specific for the target. RT-PCR showed that the aidA gene that was not targeted remained intact (data not shown). Deletion of aidA48 did not affect adherence in vitro or in the pig ileal loops; it is possible that loss of AIDA-48 might have been compensated for by AIDA-15 or other virulence factors of similar function. A double mutant would be useful to test this hypothesis. Deletion of the aidA15 gene significantly impaired the ability of EHEC O157:H7 to cause adherence in pig ileal loops (Table 3). When the complementation studies were done (Fig. 5), complemented mutant 86-24NSΔaidA15 resulted in adherence similar to that of the wild type. In this experiment, however, pig-to-pig variation prevented the substantial decrease in adherence of the mutant from achieving statistical significance. These data strongly suggest that aidA15 plays a role in colonization of the pig's intestine by EHEC O157:H7. The notion that OI-15 may encode an adhesin in EHEC O157:H7 is further supported by the recent study by Wells et al. (41), in which overexpression of aidA15 (named ehaA) in E. coli K-12 conferred the ability to form large cell aggregates, promote strong biofilm formation, and adhere to primary epithelial cells of the bovine terminal rectum. However, deletion of aidA15 (ehaA) from EHEC O157:H7 strain EDL933 and O111:H− did not cause decreased biofilm growth, suggesting that redundant factors may compensate for the deletion (41).

OI-7 was not involved in the adherence of EHEC O157:H7 to HEp-2 or IPEC-J2 epithelial cells. Z0250-encoded putative macrophage toxin in OI-7 has 20.6% homology to 949 amino acids of Legionella pneumophila Icmf (26). This similarity implies that Z0250 may also confer an advantage on EHEC O157:H7 in the hostile host intestinal environment; however, deletion of Z0250 did not affect colonization or fluid accumulation in the pig ileal loops. Z0254 of OI-7 encodes a protein with 40% homology to 728 amino acids of the plant Hsp101 (26), a member of the ClpB subfamily, which plays a role in thermotolerance and resolubilization of protein aggregates (19). This function of ClpB suggests that the ClpB-like protein of EHEC O157:H7 could provide similar advantages to the bacteria in hostile host environments such as the low gastric pH, although data from this study showed that deletion of Z0254 did not influence adherence or fluid accumulation in the pig ileal loops. It cannot be ruled out that the putative macrophage toxin and ClpB-like chaperone may play a role in the general stress tolerance of EHEC O157:H7 in the host gastrointestinal tract, the effect of which might not be shown in pig ileal loops, since this system bypasses the acidic stomach and fluctuating pH in the upper gastrointestinal tract. The effect of OI-7 on bacterial pathogenesis and fitness requires further investigation.

Tests of EHEC O157:H7 mutants showed that the in vitro and in vivo data were sometimes different. For example, the deletion of aidA15 did not impair adherence to cultured epithelial cells but caused significant reductions in adherence in the pig ileal loops. This discrepancy between the in vitro and in vivo results may be due to the different environments in which the bacteria and epithelial cells interact, differences in the epithelial cells themselves, differences in the variations observed in the two systems, and/or differences in mechanisms involved in adherence. The in vitro adherence conditions are excellent for bacterial growth and less stressful and lack the full host response component, while the in vivo environment includes the harsh conditions in the intestinal tract, such as the immune response, the indigenous microflora, and competition for nutrients (35). Deletion of aidA15 may influence the ability to colonize efficiently under such conditions. Colonization factors may be host specific and/or environmentally regulated (28), resulting in differential activity or expression of virulence genes.

IPEC-J2 cells were successfully used for bacterial adherence assays with EHEC O157:H7. The results with these porcine intestinal epithelial cells were similar to those with HEp-2 cells, and there was a tendency for the EHEC organisms to adhere to a greater extent to the IPEC-J2 cells than to the HEp-2 cells. Our data indicate that IPEC-J2 cells are a useful in vitro model for studies of adherence of EHEC O157:H7. Although the pig ileal loops allowed comparisons to be made in adjacent segments of intestine, pig-to-pig variation was considerable. Further studies using intact pigs are required. However, our attempts to establish a conventional pig model were thwarted by extreme resistance of pigs to colonization by O157:H7 strain 86-24. A total of 76 conventional pigs of various ages ranging from less than 8 h to 3 days were tested by oral challenge (unpublished data), but the inoculated O157:H7 organisms failed to establish in any of them. It is possible that modifications such as treatment with corticosteroids might reduce this colonization resistance.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hai Yu for assistance with statistical analysis.

The research was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). X.Y. was financially supported by AAFC. J.Z. and B.L. were visiting scholars supported by the China Scholarship Council.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 12 June 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Benz, I., and M. A. Schmidt. 1989. Cloning and expression of an adhesin (AIDA-I) involved in diffuse adherence of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 57:1506-1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Best, A., R. M. La Ragione, W. A. Cooley, C. D. O'Connor, P. Velge, and M. J. Woodward. 2003. Interaction with avian cells and colonisation of specific pathogen free chicks by Shiga-toxin negative Escherichia coli O157:H7 (NCTC 12900). Vet. Microbiol. 93:207-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conedera, G., E. Mattiazzi, F. Russo, E. Chiesa, I. Scorzato, S. Grandesso, A. Bessegato, A. Fioravanti, and A. Caprioli. 2007. A family outbreak of Escherichia coli O157 haemorrhagic colitis caused by pork meat salami. Epidemiol. Infect. 135:311-314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cornick, N. A., A. F. Helgerson, and V. Sharma. 2007. Shiga toxin and Shiga toxin-encoding phage do not facilitate Escherichia coli O157:H7 colonization in sheep. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:344-346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donohue-Rolfe, A., D. W. Acheson, A. V. Kane, and G. T. Keusch. 1989. Purification of Shiga toxin and Shiga-like toxins I and II by receptor analog affinity chromatography with immobilized P1 glycoprotein and production of cross-reactive monoclonal antibodies. Infect. Immun. 57:3888-3893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donohue-Rolfe, A., I. Kondova, S. Oswald, D. Hutto, and S. Tzipori. 2000. Escherichia coli O157:H7 strains that express Shiga toxin (Stx) 2 alone are more neurotropic for gnotobiotic piglets than are isotypes producing only Stx1 or both Stx1 and Stx2. J. Infect. Dis. 181:1825-1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edwards, R. A., L. H. Keller, and D. M. Schifferli. 1998. Improved allelic exchange vectors and their use to analyze 987P fimbria gene expression. Gene 207:149-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feder, I., F. M. Wallace, J. T. Gray, P. Fratamico, P. J. Fedorka-Cray, R. A. Pearce, J. E. Call, R. Perrine, and J. B. Luchansky. 2003. Isolation of Escherichia coli O157:H7 from intact colon fecal samples of swine. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9:380-383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frankel, G., O. Lider, R. Hershkoviz, A. P. Mould, S. G. Kachalsky, D. C. Candy, L. Cahalon, M. J. Humphries, and G. Dougan. 1996. The cell-binding domain of intimin from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli binds to beta1 integrins. J. Biol. Chem. 271:20359-20364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gunzer, F., U. Bohn, S. Fuchs, I. Muhldorfer, J. Hacker, S. Tzipori, and A. Donohue-Rolfe. 1998. Construction and characterization of an isogenic slt-ii deletion mutant of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 66:2337-2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gunzer, F., I. Hennig-Pauka, K. H. Waldmann, and M. Mengel. 2003. Gnotobiotic piglets as an animal model for oral infection with O157 and non-O157 serotypes of STEC. Methods Mol. Med. 73:307-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Islam, D., L. Bandholtz, J. Nilsson, H. Wigzell, B. Christensson, B. Agerberth, and G. Gudmundsson. 2001. Downregulation of bactericidal peptides in enteric infections: a novel immune escape mechanism with bacterial DNA as a potential regulator. Nat. Med. 7:180-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jain, S., P. van Ulsen, I. Benz, M. A. Schmidt, R. Fernandez, J. Tommassen, and M. B. Goldberg. 2006. Polar localization of the autotransporter family of large bacterial virulence proteins. J. Bacteriol. 188:4841-4850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson, J. R., S. Jelacic, L. M. Schoening, C. Clabots, N. Shaikh, H. L. Mobley, and P. I. Tarr. 2005. The IrgA homologue adhesin Iha is an Escherichia coli virulence factor in murine urinary tract infection. Infect. Immun. 73:965-971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaper, J. B., S. Elliott, V. Sperandio, N. T. Perna, G. F. Mayhew, and F. R. Blattner. 1998. Attaching-and-effacing intestinal histopathology and the locus of enterocyte effacement, p. 163-182. In J. B. Kaper and A. D. O'Brien (ed.), Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other Shiga toxin-producing E. coli strains. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 16.Kaper, J. B., J. P. Nataro, and H. L. Mobley. 2004. Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2:123-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knutton, S., T. Baldwin, P. H. Williams, and A. S. McNeish. 1989. Actin accumulation at sites of bacterial adhesion to tissue culture cells: basis of a new diagnostic test for enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 57:1290-1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Konowalchuk, J., J. I. Speirs, and S. Stavric. 1977. Vero response to a cytotoxin of Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 18:775-779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee, Y. R., R. T. Nagao, and J. L. Key. 1994. A soybean 101-kD heat shock protein complements a yeast HSP104 deletion mutant in acquiring thermotolerance. Plant Cell 6:1889-1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maurer, J., J. Jose, and T. F. Meyer. 1999. Characterization of the essential transport function of the AIDA-I autotransporter and evidence supporting structural predictions. J. Bacteriol. 181:7014-7020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKee, M. L., A. R. Melton-Celsa, R. A. Moxley, D. H. Francis, and A. D. O'Brien. 1995. Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 requires intimin to colonize the gnotobiotic pig intestine and to adhere to HEp-2 cells. Infect. Immun. 63:3739-3744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Menard, R., P. J. Sansonetti, and C. Parsot. 1993. Nonpolar mutagenesis of the ipa genes defines IpaB, IpaC, and IpaD as effectors of Shigella flexneri entry into epithelial cells. J. Bacteriol. 175:5899-5906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Menge, C., L. H. Wieler, T. Schlapp, and G. Baljer. 1999. Shiga toxin 1 from Escherichia coli blocks activation and proliferation of bovine lymphocyte subpopulations in vitro. Infect. Immun. 67:2209-2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphy, K. C., and K. G. Campellone. 2003. Lambda Red-mediated recombinogenic engineering of enterohemorrhagic and enteropathogenic E. coli. BMC Mol. Biol. 4:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nataro, J. P., and J. B. Kaper. 1998. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:142-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perna, N. T., J. D. Glasner, V. Burland, and G. Plunkett III. 2002. The genomes of Escherichia coli K-12 and pathogenic E. coli, p. 3-53. In M. S. Donnenberg (ed.), Escherichia coli: virulence mechanisms of a versatile pathogen. Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

- 27.Perna, N. T., G. Plunkett III, V. Burland, B. Mau, J. D. Glasner, D. J. Rose, G. F. Mayhew, P. S. Evans, J. Gregor, H. A. Kirkpatrick, G. Posfai, J. Hackett, S. Klink, A. Boutin, Y. Shao, L. Miller, E. J. Grotbeck, N. W. Davis, A. Lim, E. T. Dimalanta, K. D. Potamousis, J. Apodaca, T. S. Anantharaman, J. Lin, G. Yen, D. C. Schwartz, R. A. Welch, and F. R. Blattner. 2001. Genome sequence of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Nature 409:529-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rashid, R. A., T. A. Tabata, M. J. Oatley, T. E. Besser, P. I. Tarr, and S. L. Moseley. 2006. Expression of putative virulence factors of Escherichia coli O157:H7 differs in bovine and human infections. Infect. Immun. 74:4142-4148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ritchie, J. M., P. L. Wagner, D. W. Acheson, and M. K. Waldor. 2003. Comparison of Shiga toxin production by hemolytic-uremic syndrome-associated and bovine-associated Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:1059-1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robinson, C. M., J. F. Sinclair, M. J. Smith, and A. D. O'Brien. 2006. Shiga toxin of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli type O157:H7 promotes intestinal colonization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:9667-9672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sandhu, K. S., R. C. Clarke, and C. L. Gyles. 1999. Virulence markers in Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolated from cattle. Can. J. Vet. Res. 63:177-184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schuller, S., R. Heuschkel, F. Torrente, J. B. Kaper, and A. D. Phillips. 2007. Shiga toxin binding in normal and inflamed human intestinal mucosa. Microbes Infect. 9:35-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schweizer, H. D. 1993. Small broad-host-range gentamycin resistance gene cassettes for site-specific insertion and deletion mutagenesis. BioTechniques 15:831-834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheng, H., J. Y. Lim, H. J. Knecht, J. Li, and C. J. Hovde. 2006. Role of Escherichia coli O157:H7 virulence factors in colonization at the bovine terminal rectal mucosa. Infect. Immun. 74:4685-4693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shin, R., M. Suzuki, and Y. Morishita. 2002. Influence of intestinal anaerobes and organic acids on the growth of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. J. Med. Microbiol. 51:201-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sinclair, J. F., and A. D. O'Brien. 2002. Cell surface-localized nucleolin is a eukaryotic receptor for the adhesin intimin-gamma of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. J. Biol. Chem. 277:2876-2885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith, D. G., S. W. Naylor, and D. L. Gally. 2002. Consequences of EHEC colonisation in humans and cattle. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 292:169-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tarr, P. I., S. S. Bilge, J. C. Vary, Jr., S. Jelacic, R. L. Habeeb, T. R. Ward, M. R. Baylor, and T. E. Besser. 2000. Iha: a novel Escherichia coli O157:H7 adherence-conferring molecule encoded on a recently acquired chromosomal island of conserved structure. Infect. Immun. 68:1400-1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tarr, P. I., C. A. Gordon, and W. L. Chandler. 2005. Shiga-toxin-producing Escherichia coli and haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Lancet 365:1073-1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tarr, P. I., M. A. Neill, C. R. Clausen, J. W. Newland, R. J. Neill, and S. L. Moseley. 1989. Genotypic variation in pathogenic Escherichia coli O157:H7 isolated from patients in Washington, 1984-1987. J. Infect. Dis. 159:344-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wells, T. J., O. Sherlock, L. Rivas, A. Mahajan, S. A. Beatson, M. Torpdahl, R. I. Webb, L. P. Allsopp, K. S. Gobius, D. L. Gally, and M. A. Schembri. 2008. EhaA is a novel autotransporter protein of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 that contributes to adhesion and biofilm formation. Environ. Microbiol. 10:589-604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]