Abstract

Rapid advances have been made in decreasing acute rejection rates and improving short-term graft survival in kidney transplant recipients. Whether these advances ultimately will lead to a commensurate improvement in long-term survival is not yet known. In recent years, greater attention has been placed on defining the precise etiology of graft loss, determining how far and with what agents we can minimize immunosuppression, and delineating the nature of both T cell-mediated as well as antibody-mediated rejection. In addition, with the growing disparity of available organs and patients in need of a transplant, greater attention has been placed on optimizing allocation. In this mini-review, we will focus on developments over the last couple of years, paying particular attention to insights, studies, and observations that may attempt to elucidate some of these open questions.

Registry analyses demonstrated a lack of improvement in overall kidney graft survival over the period from 1988 to 1995, despite marked decrease in acute rejection (AR) rates (1). Whether these findings will hold true for the most recent era is not yet known, but they have spurred further inquiry into the reasons for allograft damage and failure, as well as the development of novel ways to prolong graft survival and expand the donor pool. In this review, we hope to cover some major advances and areas of need that have been identified over the last few years.

Current outcomes and the search for specific causes of graft loss

The kidney waiting list continues to grow each year, with over 70,000 candidates registered (2). Over the past decade, the number of standard criteria donor (SCD) transplants, expanded criteria donor (ECD) transplants, and transplanted kidneys recovered through donation after cardiac death (DCD) grew by 22%, 59%, and 684%, respectively. Despite an increase in overall transplants, living donor transplants have remained relatively stable since 2004. Patient survival following renal transplantation remains excellent, with one-year unadjusted survival rates ranging from 95% to 98% for recipients of deceased donor and living donor transplants, respectively (2). Five-year patient survival is clearly higher for recipients of living donor kidneys (90%) than for recipients of non-ECD (83%) or ECD (69%) deceased donor kidneys. The last five years have seen a small trend toward improved unadjusted allograft survival for living and deceased donor kidneys. However, there continues to be a chronic attrition of grafts long-term, with five-year survival rates of 80% for living donor kidneys and 68% for deceased donor kidneys (2).

According to registry data, the most frequent cause of late graft loss is “chronic rejection.” However, this classification is misleading, as it implies that all late scarring is due to a specific T cell mediated alloimmune injury. Although introduction of the term chronic allograft nephropathy (CAN) was successful in reversing this misconception, CAN has now been removed from the Banff classification for kidney allograft pathology, as its use tended to undermine recognition of morphological features enabling diagnosis of specific causes of chronic graft dysfunction (3). Thus, there is an emerging need for an appropriate classification of chronic allograft injury and loss. As Banff criteria evolve to reflect improved methods for accurate detection of the distinctive features of individual allograft pathologies, registry classifications must keep pace. Recently, a concerted effort has been placed on finding specific etiologies that lead to the lesions of interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy (IF/TA), as well as chronic glomerular injury. As these lesions are non-specific responses to injury, antibody-mediated endothelial activation, calcineurin inhibitor (CNI) toxicity, recurrent disease, chronic inflammation, innate immune mechanisms, as well as diabetes mellitus and hypertension have all been invoked as potential etiologies. The large National Institutes of Health-sponsored DeKAF study is currently addressing this issue, as have several detailed histopathologic studies from the Mayo Clinic group and others. A putative mechanism of fibrosis that may be a common pathway after tubular damage is epithelial-mesenchymal transition, whereby damaged tubules (immune or nonimmune) transform into activated myofibroblasts that migrate into the interstitium to produce profibrotic molecules (4).

Expanding the donor pool

To address donor shortage, the National Organ Donation Breakthrough Collaborative was launched in 2003, with the goal of increasing the national donation conversion rate to 75% (2). A second round initiated in 2005, the National Organ Transplantation Breakthrough Collaborative endeavors to increase the average number of organs transplanted per donor to 3.75. Some of the innovations promoted by the Collaborative include: (1) placement of in-house trained requestors; (2) greater involvement of critical care specialists; (3) routine use of DCD kidneys from donors under age 50 years for standard recipients and of ECD kidneys for select recipients with long waiting times; (4) transplantation of kidneys with acute renal failure but previous excellent function; and (5) utilization of donors at high risk for transmission of Hepatitis C or HIV in select recipients. Since the first Collaborative, national organ donation rates have increased 23% and the number of transplantable organs from deceased donors has increased by 25%.

A new initiative, named the “58 DSA Challenge” is based on the observation that the 58 donation service areas (DSA) vary widely in the utilization of conventional donors, representing untapped kidney donor potential (2). The challenge is for each DSA to perform ten additional transplants per month, which translates into nearly 7,000 transplants per year nationally. Projections are that fulfillment of the challenge would eliminate the active kidney transplant waiting list by as early as 2015. A recent large international randomized, controlled trial demonstrated a significant reduction in DGF and improved one-year graft survival following hypothermic machine perfusion of deceased donor kidneys (5).

The Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network Kidney Committee is considering recommending an allocation system for deceased donor kidneys that incorporates life years from transplant (LYFT), which is defined as the difference in expected median survival for a candidate with a kidney transplant from a specific donor and the expected median survival for that candidate without any transplant at all (6). Life-years without a transplant have a lower quality of life and are weighted accordingly in the calculation. The scheme would continue current allocation priority for pediatric and sensitized candidates, years on dialysis, and prior living donation. By matching deceased donor kidneys and candidates with the longest potential survival, the LYFT-based allocation should reduce the rate of death with a functioning graft and increase the total number of years of life that can be achieved from the existing deceased donor pool. Criticisms have been voiced over concerns that old or frail candidates, though no less deserving, will have less opportunity to receive a kidney transplant. However, if elimination of the active waiting list can be achieved, all viable candidates would be guaranteed a transplant.

Understanding the mechanisms of rejection

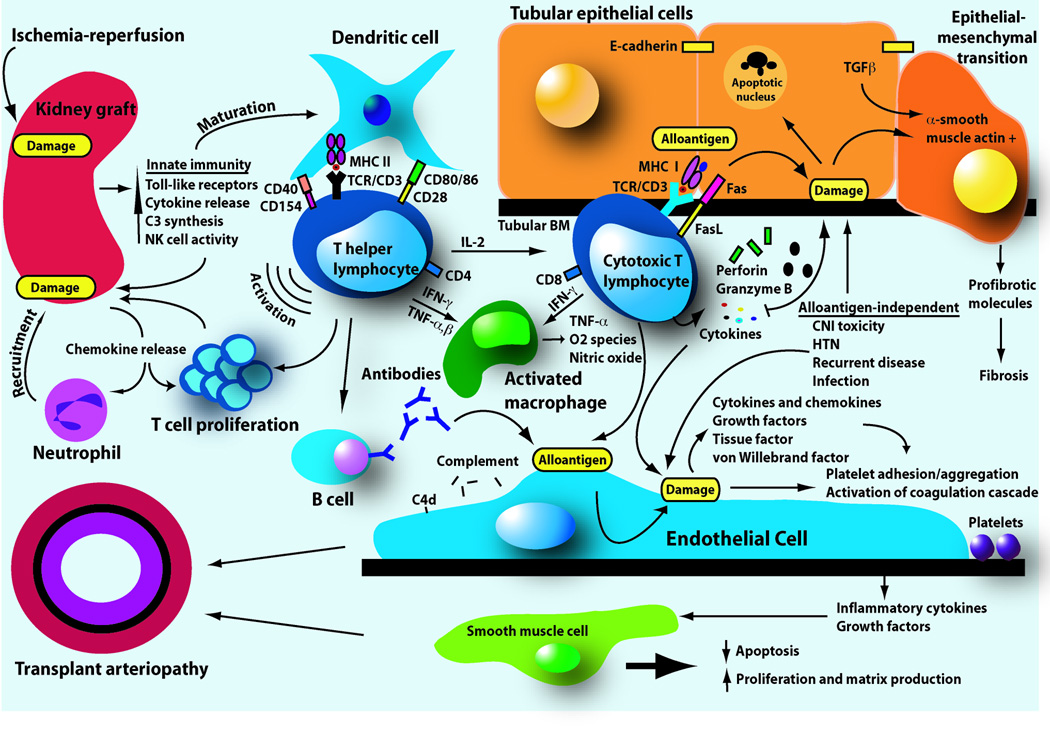

Allograft rejection is caused by several elements of the immune system, including antibody, complement, T cells and other cell types (reviewed in (7)), and Banff criteria have been modified to reflect their individual involvement (8). Although there are a variety of target cells in the graft, endothelial and tubular cells are particularly affected by these mediators (Figure 1). Pathologically, acute T cell mediated rejection (TCMR) is manifested by the accumulation of mononuclear cells (mostly T cells and macrophages) in the interstitium, accompanied by inflammation of tubules and sometimes of arteries (7). The precise mechanisms by which T cells mediate graft injury are still uncertain. The two leading theories include cell-mediated cytotoxicity of parenchymal cells and local cytokine release. CD8+ class I reactive T cells kill target cells through perforin and granzyme B, or through Fas/FasL cytolytic pathways. Cytokines may act directly on tubular cells or indirectly via effects on endothelium and vascular supply. Recent gene expression analysis of human renal allograft biopsy and urine samples during AR demonstrates selective expression of mRNA transcripts for cytotoxic T cell (CTL)-associated molecules and for several cytokines, supporting these theories (9, 10). The role of regulatory T cells during TCMR continues to be debated (11).

Figure 1. Diagram of postulated events leading to graft damage during kidney transplantation.

At engraftment, ischemia-reperfusion injury occurs with activation of Toll-like receptors of the innate immune system and subsequent cytokine release. These pro-inflammatory mediators induce tubular epithelial cells to attract neutrophils and T cells by production of chemokines. Innate immune system activation induces maturation of dendritic cells, leading the transition to the adaptive or antigen-specific phase of transplantation immunity. Dendritic cells activate CD4+ T helper cells through presentation of alloantigen in the context of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules and ligation of appropriate T cell surface costimulatory molecules. After activation, CD4+ T helper cells induce further T cell proliferation, the production of alloantibodies from B cells, activation of macrophages, and differentiation of naïve CD8+ T cells into cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Mononuclear cells, especially cytotoxic T lymphocytes, enter between tubular cells and induce apoptosis by releasing cytolytic granules containing perforin and granzyme or by exposure to FasL on the T cell surface. Tubular cells chronically exposed to transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) may undergo epithelial-mesenchymal transition, an aberrant phenotype evidenced by epithelial cell expression of α-smooth muscle actin and loss of E-cadherin expression. These cells then may migrate to the interstitium and contribute to fibrosis. Both T cells and antibody likely recognize alloantigen on target endothelium. While T cells may cause cytotoxicity directly, alloantibody is usually directed against the MHC molecule, followed by activation of complement. Antigen recognition leads to endothelial secretion of factors that activate the immune and coagulation systems. These activities promote rejection and chronic changes of the endothelium and underlying smooth muscle layer, resulting in the characteristic histopathologic findings of transplant arteriopathy. Alloantigen-independent factors also contribute to tubular and endothelial cell damage.

Acute antibody-mediated rejection (AMR) is now widely recognized as a distinct clinicopathologic entity that occurs with or without a component of TCMR (12). Histologic features include accumulation of neutrophils and monocytes in peritubular and glomerular capillaries. Detection of AMR is substantially easier since the introduction of C4d staining, which correlates highly with histologic features of neutrophils or fibrinoid necrosis. Antibodies to donor HLA class I or II antigens are present in roughly 90% of patients who have C4d deposition and acute graft dysfunction versus less than 10% in C4d-negative AR. Deposition of C4d without detectable circulating antibody can be due to antibody absorption by the graft or antibodies to non-HLA antigens. Conversely, glomerulitis can occur in the absence of C4d deposition but in the presence of circulating donor antibodies. Using microarray technology, recent analysis of pathogenesis-based transcript sets (PBT) indicated a large scale of disturbances across all biopsies in a continuous rather than dichotomous fashion, with many other forms of injury having similar disturbances, albeit at lower levels than rejection (13). PBT changes correlated with histopathological lesions and were similar between TCMR and AMR, although the latter was discriminated by increased endothelial cell activation gene expression (8). Whether this technology will lead to an advanced understanding of the rejection process and/or improved methods of detection is still unclear.

Though the lesions of IF/TA are a source of considerable controversy, much headway has been made in defining the histology associated with chronic AMR (8). Characteristic features on biopsy include transplant glomerulopathy, peritubular capillaropathy, transplant arteriopathy, and less specifically, IF/TA. Any one of these findings, when accompanied by C4d deposition in peritubular capillaries and by circulating donor-specific antibody, is diagnostic of chronic AMR and portends a poor prognosis. It is also possible that antibody mediated glomerular injury may not always be detected by the strict Banff criteria. Antibodies to MICA (a polymorphic HLA class I-related antigen) may also be associated with late graft failure, even in the absence of measurable HLA antibodies (14).

Optimizing immunosuppression

The combination of CNI, anti-metabolite, and corticosteroid (CS) remains the most common maintenance IS regimen at discharge among US transplant centers, although significant changes have occurred over the past decade (2). In contrast to 1997, when 77% of patients were discharged on cyclosporine (CYA), 82% were initiated on tacrolimus (TAC) in 2006. This shift is based on a multitude of mostly uncontrolled, and often conflicting, trials demonstrating less AR, improved graft function and better blood pressure control with TAC, at the expense of increased new onset diabetes, neurologic and gastrointestinal (GI) side effects. These differences will prove meaningful only if well-designed trials demonstrate altered patient survival. Despite the preference by the transplant community for TAC-based regimens, the Food and Drug Administration has been reluctant to adopt this agent as the control arm in clinical studies for drugs under development. This policy has the potential to alter patient enrollment and therefore, may call into question the results of these studies.

Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) remains the anti-metabolite of choice, based on three large multicenter trials demonstrating significant reduction of AR compared to azathioprine (AZA) in patients receiving the older formulation of CYA. More recent reports have questioned whether there is such a benefit in patients receiving the microemulsion formulation of CYA (15). Despite controlled trials failing to demonstrate any reduction of GI adverse effects with mycophenolate sodium, increased use of this agent has occurred. Use of mTOR inhibitors has steadily declined since a peak in 2001 (2), due in large part to higher AR rates, questionable improvement in graft function, poor tolerability, synergistic nephrotoxicity with CNI, and an association with proteinuria. The use of CS at the time of discharge has decreased over the past decade from 97% to 68%. Over that same period, the use of induction therapy has increased from 35% to 79%, and usage is higher in patients not placed on maintenance steroids (2). Thymoglobulin is now the favored induction agent (42%), followed by IL-2 receptor antagonists (IL-2RA; daclizumab and basiliximab – 29%) and alemtuzumab (10%). Randomized prospective trials have demonstrated lower AR rates but higher adverse event rates with thymoglobulin versus IL-2RA in patients at high risk for delayed graft function (DGF) and AR (16), while short-term graft survival appears equivalent. Studies directly comparing alemtuzumab with these two biological agents are limited. The powerful immunosuppression associated with many induction agents has real potential for significant short- and long-term toxicity, and will ultimately prove acceptable only if a clear benefit in long-term graft or patient survival can be demonstrated.

In an effort to reduce toxicities associated with IS, attention has been directed toward minimizing exposure to CNI and CS. Withdrawal of CYA from patients with stable graft function in both the AZA and MMF eras has uniformly resulted in increased rates of AR, with worsened graft survival in most studies (17). In contrast, withdrawal or reduction of CNI in patients with deteriorating graft function has shown a beneficial impact on renal function, suggesting a more favorable risk-benefit ratio in this population. When used as maintenance therapy in a CNI-free regimen, costimulation blockade with belatacept achieved equivalent AR rates compared to a CYA-based regimen, and while only measured in a minority of patients, graft function was significantly improved (18). As with most biologic agents, however, scheduled outpatient intravenous infusions are required. Efforts to avoid CNI in de novo renal transplant recipients by substituting low-dose rapamycin (RAPA) in the recent SYMPHONY study were met with higher AR rates and worse graft survival in patients receiving RAPA/MMF/CS compared to standard-dose CYA/MMF/CS, despite IL-2RA induction in the RAPA group (19). In this study, patients treated with IL-2RA/MMF/CS in combination with low-dose TAC had the best outcomes, suggesting this regimen may represent the optimal balance between nephrotoxicity and prevention of AR. Recent results from the CONVERT study (20) suggest that conversion from CNI to RAPA after six months may be undertaken safely in patients with baseline GFR greater than 40 mL/min and normal urinary protein. However, the benefits of such conversion on graft function were small, and this approach has not yet demonstrated improved graft survival. Furthermore, conversion was associated with higher adverse events, although a significantly lower malignancy rate.

Several large uncontrolled trials in the current IS era have reported acceptable AR rates and excellent short-term graft survival following minimization of CS. However, an early landmark study emphasized the importance of longer follow up when assessing the true impact of this intervention on graft survival (21). Two recent randomized controlled trials have demonstrated a significant increase in biopsy-proven AR with CS avoidance (22, 23), and while one study found no difference in graft function at five years, a significant increase in biopsy proven chronic allograft nephropathy was noted in a post hoc analysis (23). Although significant improvements were seen in some elements of the metabolic syndrome, longer follow up will be necessary to determine whether these changes impact significantly on patient survival. Table 1 summarizes recent minimization trials.

Table 1.

Recent Immunosuppression Exposure Minimization Trials

| Trial | Treatment Groups | GFR¶ (mL/min) |

AR¶ (%) |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Larson, et al 36 | Mod-High RAPA | 63* | 19* | *P=NS vs. standard TAC. Mostly living donors |

| Standard TAC | 61 | 14 | ||

| CAESAR 37 | CYA Withdrawal | 51 | 38* | *P=0.04 vs. standard CYA; |

| CYA Minimization | 51 | 25 | *P=0.03 vs. CYA minimization. |

|

| Standard CYA | 49 | 28 | ||

| SYMPHONY 19 | Low TAC | 65* | 12* | *P≤0.001 vs. others. |

| Low CYA | 59 | 24 | “Low-medium risk” mostlydeceased donor transplants Serious adverse events highest in RAPA group. |

|

| Low RAPA | 57 | 37 | ||

| Standard CYA | 57 | 26 | ||

| Belatacept StudyGroup 18 | High Belatacept | 66* | 7 | 6-month results. *P=0.01; |

| Low Belatacept | 62§ | 6 |

§P=0.04 vs. standard CYA. Monthly IV infusions required for Belatacept. |

|

| Standard CYA | 54 | 8 | ||

| FREEDOM 22 | CS Avoidance | 59 | 32* | *P=0.007 vs. standard CS. |

| Early CS Withdrawal | 59 | 26 | Blacks underrepresented. CYA-based regimens. |

|

| Standard CS | 61 | 15 | ||

| Astellas Steroid Withdrawal Group 23 | Early CS Withdrawal | 59 | 18* | 5-year results. *P=0.04 vs. low |

| Low CS | 60 | 11 | CS. More CAN (post hoc). TAC-based regimens |

|

| CONVERT 20 | CNI Conversion to RAPA | 63* | 16 | 2-year results. *P=0.009 vs. |

| CNI Continuation | 60 | 15 | CNI Continuation. Adverse events higher but malignancy lower with RAPA. |

1-year results unless otherwise stated. AR=acute rejection. GFR=glomerular filtration rate. CAN=chronic allograft nephropathy. CYA=cyclosporine A. TAC=tacrolimus. RAPA=rapamycin. CS=corticosteroid. CNI=calcineurin inhibitor.

One of the consequences of heightened immunosuppression is the emergence of BK virus reactivation (24). Retrospective analysis of biopsy specimens confirmed a stepwise increase in the incidence of BK virus nephropathy (BKVN) coinciding with reduction in AR rates, with as high as 10% of new transplants affected in the current decade. Evidence argues for a donor origin of virus, with the net state of immunosuppression rather than a specific agent responsible for reactivation. Immunosuppression reduction is the principle treatment but predisposes to AR and chronic dysfunction, with over half of patients with established BKVN developing graft failure. Currently no approved antiviral agent is available, although leflunomide, cidofovir, quinolones, and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) have been used in uncontrolled trials in concert with reduced immunosuppression, albeit with unproven efficacy. Retransplantation after graft loss has been successful even when performed during active viremia (25).

Encouraging studies have demonstrated that preemptive reduction of immunosuppression upon detection of viremia early post-transplant prevents the development of BKVN without an increase in AR (26). It must be emphasized that these studies did not include a control group without immunosuppression reduction, and the cost effectiveness of frequent monitoring has been brought into question. Furthermore, patients at highest risk for AR may not respond as favorably, and continued need exists for an effective antiviral agent both for prophylaxis and for treatment. However, this approach holds great potential to reduce the incidence of BKVN to manageable levels that no longer appreciably impact overall graft survival.

Crossing incompatible immunologic barriers

The last ten years has seen an explosion of interest in transplantation across or around positive T cell crossmatch and ABO group incompatibilities (27). Successful living donor transplant incompatible protocols vary among centers but generally include plasmapheresis or immunoadsorption to remove anti-HLA or –ABO group antibodies followed by infusion of low-dose IVIG for putative immunomodulatory effects (28). Rituximab (anti-CD20 antibody) is usually reserved for sensitized patients at highest risk for severe AMR but now replaces splenectomy in most ABO-incompatible protocols. Induction therapy with thymoglobulin or IL-2RA, followed by maintenance immunosuppression with TAC/MMF/CS is standard. Short-term outcomes following ABO incompatible transplants are comparable to compatible live donor transplants (29). However, new regulations implemented by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services that mandate centers meet expected levels of patient outcome as determined by registry data may discourage centers from performing positive crossmatch transplants, which currently have inferior outcomes. Ultimately, large randomized-controlled trials will be necessary for both types to assess the true impact on cost, quality of life, and long-term outcomes.

Plasmapheresis-based protocols are usually not suitable for highly sensitized patients awaiting deceased donor transplantation because availability of suitable organs is unpredictable and plasmapheresis is both difficult and very expensive to continue indefinitely. The combination of rituximab and high-dose IVIG was recently used to desensitize 16 of 20 highly sensitized patients, allowing transplantation by either living or deceased donor kidneys (30). Graft and patient survival were acceptable, although the incidence of AR, including AMR, was high. This approach may prove useful in the care of sensitized patients but needs to be validated by larger controlled multi-center trials with longer follow-up, including treatment arms that assess whether rituximab improves outcomes compared to IVIG alone.

The safest and most cost-effective approach for incompatible patients with an available living donor is to seek a suitable kidney through the Living Donor Exchange, where computer algorithms are used to match compatible donors and recipients. Computer simulations suggest that a national program, particularly one that optimizes HLA matching, could significantly increase the number of paired kidney donation/transplants (31). A more controversial strategy is the List Donor Kidney Exchange, which involves the incompatible crossmatch living donor (usually ABO-A or ABO-B) donating a kidney to the deceased donor list. This donation allows the partner of the donor (usually ABO-O) to ascend to the top of the list and receive a compatible kidney rather quickly. Concerns are that already-waitlisted ABO-O patients will wait slightly longer, although future ABO-O candidates would benefit from an extra ABO-O patient not being added to the list.

The quest for transplant tolerance

Operational tolerance includes prevention of acute and chronic rejection, normal graft function with long-term indefinite graft survival, and no requirement for maintenance immunosuppression in an immunocompetent host (32). It has been known for nearly two decades that patients treated with bone marrow transplantation (BMT) for multiple myeloma who develop renal failure can subsequently accept kidney allografts from the same donor without immunosuppression. However, the standard conditioning regimen is far too toxic for routine use in patients with end stage renal disease (ESRD). Using nonmyeloablative marrow transplantation from HLA-identical sibling donors, the team at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) demonstrated excellent tumor responses in six patients with multiple myeloma and ESRD, with operational tolerance to simultaneously transplanted donor renal allografts (33). While complete remission was not achieved in all patients, this approach allowed for the possibility of a second potentially curative BMT by restoring renal function. Although steroid-responsive AR and graft-versus-host disease requiring immunosuppression occurred in some patients, this regimen can be regarded as a clinical reality for a specific patient population typically ineligible for either renal transplantation or BMT.

Using the nonmyeloablative regimen for patients with ESRD in the absence of hematologic malignancy, the MGH team recently reported stable graft function after planned complete withdrawal of immunosuppression in five recipients of HLA-mismatched kidney allografts (34). Enthusiasm for this approach was tempered somewhat by the development of irreversible acute antibody-mediated rejection with graft failure in one recipient, prompting the addition of rituximab to the conditioning regimen. Using a similar approach, the Stanford group reported complete withdrawal of immunosuppression in one recipient of an HLA-matched sibling donor (35). While it is evident that true clinical transplant tolerance has yet to be achieved, these reports indicate true progress in the field is being made.

Conclusions

Renal transplantation remains the treatment of choice for patients with ESRD and acceptable operative risk. Through better understanding of the causes of graft failure, advances in pharmacologic therapy, and concerted efforts by the transplant community and regulatory agencies to maximize the existing donor pool, it is hopeful that incremental improvements in outcomes following this procedure will continue to be made.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The data and analyses reported in the 2007 Annual Report of the U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients have been supplied by UNOS and Arbor Research under contract with Health and Human Services. The authors alone are responsible for reporting and interpreting these data; the views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the U.S. Government.

This work was supported with funding from NIH 5K08DK066319 (KW).

REFERENCES

- 1.Meier-Kriesche HU, Schold JD, Srinivas TR, Kaplan B. Lack of improvement in renal allograft survival despite a marked decrease in acute rejection rates over the most recent era. Am J Transplant. 2004;4(3):378–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.2007 Annual Report of the U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients: Transplant Data 1997–2006. Rockville, MD: Health Resources and Services Administration, Healthcare Systems Bureau, Division of Transplantation. In.

- 3.Solez K, Colvin RB, Racusen LC, Sis B, Halloran PF, Birk PE, et al. Banff '05 Meeting Report: differential diagnosis of chronic allograft injury and elimination of chronic allograft nephropathy ('CAN') Am J Transplant. 2007;7(3):518–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vongwiwatana A, Tasanarong A, Rayner DC, Melk A, Halloran PF. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition during late deterioration of human kidney transplants: the role of tubular cells in fibrogenesis. Am J Transplant. 2005;5(6):1367–1374. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moers C, Smits JM, Maathuis MH, Treckmann J, van Gelder F, Napieralski BP, et al. Machine perfusion or cold storage in deceased-donor kidney transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(1):7–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolfe RA, McCullough KP, Schaubel DE, Kalbfleisch JD, Murray S, Stegall MD, et al. Calculating life years from transplant (LYFT): methods for kidney and kidney-pancreas candidates. Am J Transplant. 2008;8(4 Pt 2):997–1011. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cornell LD, Smith RN, Colvin RB. Kidney transplantation: mechanisms of rejection and acceptance. Annu Rev Pathol. 2008;3:189–220. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.151508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solez K, Colvin RB, Racusen LC, Haas M, Sis B, Mengel M, et al. Banff 07 classification of renal allograft pathology: updates and future directions. Am J Transplant. 2008;8(4):753–760. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Desvaux D, Schwarzinger M, Pastural M, Baron C, Abtahi M, Berrehar F, et al. Molecular diagnosis of renal-allograft rejection: correlation with histopathologic evaluation and antirejection-therapy resistance. Transplantation. 2004;78(5):647–653. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000133530.26680.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarwal M, Chua MS, Kambham N, Hsieh SC, Satterwhite T, Masek M, et al. Molecular heterogeneity in acute renal allograft rejection identified by DNA microarray profiling. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(2):125–138. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muthukumar T, Dadhania D, Ding R, Snopkowski C, Naqvi R, Lee JB, et al. Messenger RNA for FOXP3 in the urine of renal-allograft recipients. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(22):2342–2351. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colvin RB. Antibody-mediated renal allograft rejection: diagnosis and pathogenesis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(4):1046–1056. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007010073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mueller TF, Einecke G, Reeve J, Sis B, Mengel M, Jhangri GS, et al. Microarray analysis of rejection in human kidney transplants using pathogenesis-based transcript sets. Am J Transplant. 2007;7(12):2712–2722. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.02005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zou Y, Stastny P, Susal C, Dohler B, Opelz G. Antibodies against MICA antigens and kidney-transplant rejection. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(13):1293–1300. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Remuzzi G, Lesti M, Gotti E, Ganeva M, Dimitrov BD, Ene-Iordache B, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil versus azathioprine for prevention of acute rejection in renal transplantation (MYSS): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;364(9433):503–512. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16808-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brennan DC, Daller JA, Lake KD, Cibrik D, Del Castillo D. Rabbit antithymocyte globulin versus basiliximab in renal transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(19):1967–1977. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Srinivas TR, Meier-Krieschex HU. Minimizing immunosuppression, an alternative approach to reducing side effects: objectives and interim result. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3 Suppl 2:S101–S116. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03510807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vincenti F, Larsen C, Durrbach A, Wekerle T, Nashan B, Blancho G, et al. Costimulation blockade with belatacept in renal transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(8):770–781. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ekberg H, Tedesco-Silva H, Demirbas A, Vitko S, Nashan B, Gurkan A, et al. Reduced exposure to calcineurin inhibitors in renal transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(25):2562–2575. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schena FP, Pascoe MD, Alberu J, del Carmen Rial M, Oberbauer R, Brennan DC, et al. Conversion from calcineurin inhibitors to sirolimus maintenance therapy in renal allograft recipients: 24-month efficacy and safety results from the CONVERT trial. Transplantation. 2009;87(2):233–242. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181927a41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sinclair NR The Canadian Multicentre Transplant Study Group [see comments] Low-dose steroid therapy in cyclosporine-treated renal transplant recipients with well-functioning grafts. CMAJ. 1992;147(5):645–657. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vincenti F, Schena FP, Paraskevas S, Hauser IA, Walker RG, Grinyo J. A randomized, multicenter study of steroid avoidance, early steroid withdrawal or standard steroid therapy in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2008;8(2):307–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.02057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woodle ES, First MR, Pirsch J, Shihab F, Gaber AO, Van Veldhuisen P. A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter trial comparing early (7 day) corticosteroid cessation versus long-term, low-dose corticosteroid therapy. Ann Surg. 2008;248(4):564–577. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318187d1da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dall A, Hariharan S. BK virus nephritis after renal transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3 Suppl 2:S68–S75. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02770707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Womer KL, Meier-Kriesche HU, Patton PR, Dibadj K, Bucci CM, Foley D, et al. Preemptive retransplantation for BK virus nephropathy: successful outcome despite active viremia. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(1):209–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brennan DC, Agha I, Bohl DL, Schnitzler MA, Hardinger KL, Lockwood M, et al. Incidence of BK with tacrolimus versus cyclosporine and impact of preemptive immunosuppression reduction. Am J Transplant. 2005;5(3):582–594. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Magee CC. Transplantation across previously incompatible immunological barriers. Transpl Int. 2006;19(2):87–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2005.00257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stegall MD, Dean PG, Gloor JM. ABO-incompatible kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2004;78(5):635–640. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000136263.46262.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Montgomery R, Locke J, King K, Segev D, Warren D, Kraus E, et al. ABO incompatible renal transplantation: A paradigm ready for broad implementation. Transplantation. 2009 doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31819f2024. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vo AA, Lukovsky M, Toyoda M, Wang J, Reinsmoen NL, Lai CH, et al. Rituximab and intravenous immune globulin for desensitization during renal transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(3):242–251. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Segev DL, Gentry SE, Warren DS, Reeb B, Montgomery RA. Kidney paired donation and optimizing the use of live donor organs. Jama. 2005;293(15):1883–1890. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.15.1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salama AD, Womer KL, Sayegh MH. Clinical transplantation tolerance: many rivers to cross. J Immunol. 2007;178(9):5419–5423. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.9.5419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fudaba Y, Spitzer TR, Shaffer J, Kawai T, Fehr T, Delmonico F, et al. Myeloma responses and tolerance following combined kidney and nonmyeloablative marrow transplantation: in vivo and in vitro analyses. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(9):2121–2133. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kawai T, Cosimi AB, Spitzer TR, Tolkoff-Rubin N, Suthanthiran M, Saidman SL, et al. HLA-mismatched renal transplantation without maintenance immunosuppression. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(4):353–361. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scandling JD, Busque S, Dejbakhsh-Jones S, Benike C, Millan MT, Shizuru JA, et al. Tolerance and chimerism after renal and hematopoietic-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(4):362–368. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Larson TS, Dean PG, Stegall MD, Griffin MD, Textor SC, Schwab TR, et al. Complete avoidance of calcineurin inhibitors in renal transplantation: a randomized trial comparing sirolimus and tacrolimus. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(3):514–522. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ekberg H, Grinyo J, Nashan B, Vanrenterghem Y, Vincenti F, Voulgari A, et al. Cyclosporine sparing with mycophenolate mofetil, daclizumab and corticosteroids in renal allograft recipients: the CAESAR Study. Am J Transplant. 2007;7(3):560–570. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]