Abstract

It has been reported that patients with “chronic Lyme disease” have a decreased number of natural killer cells, as defined by the CD57 marker. We performed immunophenotyping in 9 individuals with post-Lyme disease syndrome, 12 who recovered from Lyme disease, and 9 healthy volunteers. The number of natural killer cells was not significantly different between the groups.

Lyme disease, the most common vector-borne illness in the United States, is caused by Borrelia burgdorferi and transmitted by the bite of the Ixodes sp. tick (the deer tick). The disease usually begins with erythema migrans, an expanding skin lesion at the site of the tick bite. Within several days or weeks, there is hematogenous dissemination of the spirochetes, and patients may present with dermatologic, neurological, cardiac, and rheumatologic involvement (7). “Chronic Lyme disease” is a controversial term applied to a broad spectrum of patients, including individuals with Lyme disease and those with post-Lyme disease syndrome (PLDS), as well as patients with no evidence of current or past B. burgdorferi infection (5, 6). PLDS is defined as the persistence or relapse of nonspecific symptoms (such as fatigue, musculoskeletal pain, and cognitive complaints) in patients who have had Lyme disease and have received an adequate course of antibiotic therapy.

It has been reported that patients diagnosed with chronic Lyme disease have a decreased number of natural killer cells, as defined by the CD57 marker, and that the changes in the number of CD57+ cells can be monitored as evidence of response to therapy (8-10). CD57 was initially used as a marker for NK cells, but it is not expressed by all NK cells and is also expressed by T-cell subpopulations. It is thought that CD57 is a marker of terminally differentiated cells (4). Currently, the most common approach for identifying NK cells utilizes a combination of CD56 and CD16 surface markers used together with CD3 to exclude T cells expressing NK markers (NK T cells). The CD57 test is offered in some clinical laboratories and is being used by some health practitioners to evaluate and follow patients diagnosed with chronic Lyme disease. To further evaluate the utility of NK cell numbers in evaluating and/or monitoring this patient group, we performed immunophenotyping in 9 patients with PLDS, 12 individuals who recovered from Lyme disease, and 9 healthy volunteers.

Patients with PLDS had a past history of Lyme disease according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention clinical definition (1, 2), a prior positive serologic analysis confirmed by immunoglobulin G Western blotting (3), received at least one course of recommended antibiotic therapy (11), and had persistent or intermittent symptoms for at least 6 months after appropriate antibiotic therapy for Lyme disease. Common symptoms included widespread musculoskeletal pain and fatigue, memory and/or concentration impairment, and radicular pain, paresthesias, or dysesthesias. The onset of symptoms was coincident with or within 6 months of initial B. burgdorferi infection, symptoms were severe enough to interfere with daily life activities, and other causes were excluded. Individuals who recovered from Lyme disease also had a past history of Lyme disease according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention clinical definition and received recommended antibiotic therapy but had no complaints attributed to the disease. Controls included healthy volunteers from areas of endemicity (n = 9) with no previous history compatible with Lyme disease and who were seronegative for B. burgdorferi. The study was approved by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Institutional Review Board, and all individuals signed informed consent forms.

Peripheral blood specimens were obtained by phlebotomy on site. Anticoagulated (EDTA) samples were stained using the whole-blood lysis method and analyzed concurrently on a dual-laser FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) using CellQuest software (BD Biosciences). Directly conjugated mouse anti-human monoclonal antibodies against CD3, CD4, CD8, CD20, CD16, CD56, and CD57 were used. Irrelevant, directly conjugated, mouse anti-human monoclonal antibodies were used to define background staining. All monoclonal antibodies were obtained from BD Biosciences and Beckman Coulter and used as recommended by the manufacturers. Lymphocytes were identified by forward and side scatter, and the lymphocyte gate was confirmed using the CD45/CD14 LeucoGate reagent (BD Biosciences). To calculate the absolute numbers of each lymphocyte subset, the percentage of positive cells was multiplied by the absolute peripheral blood lymphocyte count obtained using an automated hematology instrument on the same blood sample. Results were compared by Kruskal-Wallis test or Mann-Whitney test. The Spearman rank correlation coefficient was used to calculate quantitative correlations. All P values were two sided and regarded as statistically significant if P was <0.05.

There were six women and three men in the PLDS group, six women and six men in the recovered group, and four women and five men in the healthy volunteer group. All participants were Caucasian. The median ages in the PLDS, recovered, and healthy volunteer groups were 52, 59, and 52 years, respectively. The initial presentation of the disease was a single erythema migrans lesion in two patients, a flu-like illness in one, multiple erythema migrans lesions in one, and neurological disease in five patients in the PLDS group. In the recovered group, three patients presented with a single erythema migrans lesion, four patients presented with multiple erythema migrans lesions, and five presented with neurological disease. The time that elapsed from the initial presentation of the disease to the date of lymphocyte phenotyping was longer in the PLDS group (mean, 84 months) than for the recovered group (mean, 50 months), but the difference did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.095).

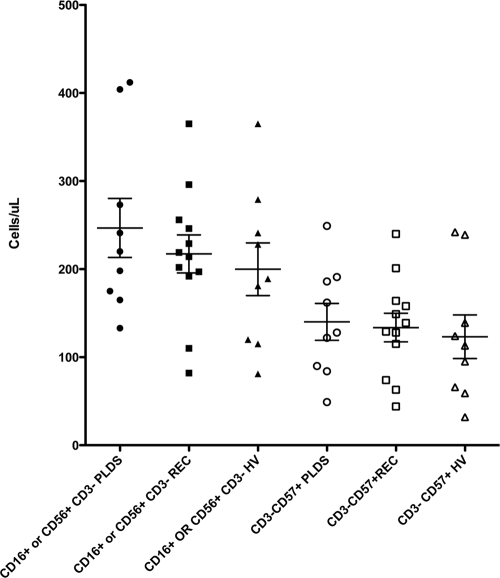

There was no significant difference between the three groups regarding the number of CD3− CD57+ (P = 0.68) or CD16+ or CD56+ CD3− cells (P = 0.65) (Fig. 1). There was also no difference between the groups regarding the numbers of CD3− CD8+ CD57+ (P = 0.54), CD3− CD56+ CD57+ (P = 0.75), and CD3− CD56− CD57+ cells (P = 0.13). Very few cells were CD3− CD56− CD57+, and the Spearman rank-order correlation coefficient between CD3− CD57+ and CD3− CD56+ CD57+ cells was 0.98 (P < 0.0001). We conclude that the numbers of NK cells do not differ between patients with PLDS, individuals who have recovered from Lyme disease, and healthy volunteers and that the number of CD57+ non-T (CD3−) cells is not helpful in evaluation or management of these patients.

FIG. 1.

Natural killer cell numbers (CD16+ or CD56+ CD3−) and CD3− CD57+ cell numbers do not differ between PLDS patients, individuals who have recovered from Lyme disease (REC), and healthy volunteers (HV).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the intramural research program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 10 June 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bacon, R., K. Kugeler, and P. Mead. 2008. Surveillance for Lyme disease—United States, 1992-2006. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 571-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1997. Case definitions for infectious conditions under public health surveillance. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 461-55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1995. Recommendations for test performance and interpretation from the Second National Conference on Serologic Diagnosis of Lyme Disease. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 44590-591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chattopadhyay, P. K., M. R. Betts, D. A. Price, E. Gostick, H. Horton, M. Roederer, and S. C. De Rosa. 2009. The cytolytic enzymes granyzme A, granzyme B, and perforin: expression patterns, cell distribution, and their relationship to cell maturity and bright CD57 expression. J. Leukoc. Biol. 8588-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feder, H. M., Jr., B. J. Johnson, S. O'Connell, E. D. Shapiro, A. C. Steere, and G. P. Wormser. 2007. A critical appraisal of “chronic Lyme disease.” N. Engl. J. Med. 3571422-1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marques, A. 2008. Chronic Lyme disease: a review. Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 22341-360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steere, A. C. 2006. Lyme borreliosis in 2005, 30 years after initial observations in Lyme, Connecticut. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 118625-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stricker, R. B., J. Burrascano, and E. Winger. 2002. Longterm decrease in the CD57 lymphocyte subset in a patient with chronic Lyme disease. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 9111-113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stricker, R. B., and E. E. Winger. 2001. Decreased CD57 lymphocyte subset in patients with chronic Lyme disease. Immunol. Lett. 7643-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stricker, R. B., and E. E. Winger. 2003. Musical hallucinations in patients with Lyme disease. South. Med. J. 96711-715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wormser, G. P., R. J. Dattwyler, E. D. Shapiro, J. J. Halperin, A. C. Steere, M. S. Klempner, P. J. Krause, J. S. Bakken, F. Strle, G. Stanek, L. Bockenstedt, D. Fish, J. S. Dumler, and R. B. Nadelman. 2006. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 431089-1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]