Abstract

The goals of this study were to optimize processing methods of cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) for immunological assays, identify acceptance parameters for the use of cryopreserved PBMC for functional and phenotypic assays, and to define limitations of the information obtainable with cryopreserved PBMC. Blood samples from 104 volunteers (49 human immunodeficiency virus-infected and 55 uninfected) were used to assess lymphocyte proliferation in response to tetanus, candida, and pokeweed-mitogen stimulation and to enumerate CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and T-cell subpopulations by flow cytometry. We determined that slowly diluting the thawed PBMC significantly improved viable cell recovery, whereas the use of benzonase improved cell recovery only sometimes. Cell storage in liquid nitrogen for up to 15 months did not affect cell viability, recovery, or the results of lymphocyte proliferation assays (LPA) and flow cytometry assays. Storage at −70°C for ≤3 weeks versus storage in liquid nitrogen before shipment on dry ice did not affect cell viability, recovery, or flow cytometric results. Storage at −70°C was associated with slightly higher LPA results with pokeweed-mitogen but not with microbial antigens. Cell viability of 75% was the acceptance parameter for LPA. No other acceptance parameters were found for LPA or flow cytometry assay results for cryopreserved PBMC. Under optimized conditions, LPA and flow cytometry assay results for cryopreserved and fresh PBMC were highly correlated, with the exception of phenotypic assays that used CD45RO or CD62L markers, which seemed labile to freezing and thawing.

Utilization of cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) for immunologic assays has dramatically increased in recent years. Cryopreserved PBMC are particularly useful in clinical trials with low end-point frequencies because they allow the immunologic assays to be performed after the conclusion of the studies, when all the end points have already been identified (1, 14, 18). In addition, the use of cryopreserved PBMC allows all assays to be performed in a single laboratory, eliminating interlaboratory variability, which has been a confounder in some studies (15). Furthermore, if changes in immunologic parameters over time are the main outcome of the immunologic studies, interassay variability may become a confounder, too. Testing all the cryopreserved PBMC per subject at one time can eliminate this confounder.

The use of cryopreserved PBMC in immunological assays poses challenges, including the availability of adequate equipment (7) and the need for technical proficiency. Assays have to be adapted and validated for the use of cryopreserved PBMC (4, 6, 9, 11, 17, 19), and the quality of the frozen cells has to be monitored (5) to ensure reliable results in functional and phenotypic assays.

The Cryopreservation Working Group (WG) of the Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group (PACTG), which operated between 1999 and 2006, developed a series of experiments aimed at optimizing methods of PBMC cryopreservation for assays requiring viable cells, adapting immunologic assays to cryopreserved PBMC, and establishing quality control parameters for immunologic assays with cryopreserved PBMC. The group focused on highly complex functional and phenotypic assays commonly used as outcome measures in studies that address immune suppression or reconstitution. Unlike previous studies of cryopreserved PBMC in immunologic assays, which were done at single laboratories (3, 8, 13, 17), our study presents results obtained at eight laboratories, substantiating the generalizibility of our findings.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

PACTG Cryopreservation WG participation and activities.

The WG included seven PACTG immunology laboratories located at the Universities of Colorado, Massachusetts, and California in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Diego and Children's Hospital of Philadelphia and Baylor School of Medicine and statistical support from the Statistical and Data Analysis Center (SDAC; Harvard School of Public Health) and the Immunology Quality Assurance Laboratory (IQA; New Jersey School of Medicine and Dentistry) for the division of AIDS-sponsored clinical trials networks. Approximately every 6 months, the laboratories exchanged fresh blood samples and/or cryopreserved PBMC from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected and uninfected volunteers. The first exchange used local methods for freezing and thawing, after which a consensus protocol was developed and implemented. Data from the first exchange were used only in the analysis of the association between viability and lymphocyte proliferation assay (LPA) results. PBMC were also tested with functional and phenotypic assays according to consensus protocols using the same reagents across all laboratories. Results were transcribed on standardized spreadsheets and submitted to SDAC, where the data were analyzed. The group met to interpret and discuss the analyses by conference call or at PACTG meetings, with an average of 10 to 12 meetings/year.

PBMC cryopreservation.

PBMC were processed according to the PACTG consensus protocol (2), except where mentioned otherwise. Briefly, cells were separated on Ficoll-Hypaque gradients and cryopreserved in 10% dimethyl sulfoxide in fetal calf serum using a slow temperature-lowering method (Mr. Frosty polyethylene vial holder [Nalgene Labware] or rate-controlled freezer). Cells were stored in liquid nitrogen for ≥1 week before thawing. Viability and recovery were measured using trypan blue exclusion.

LPA.

LPA were performed according to the adult and pediatric LPA consensus protocol (2) using candida (Greer) and tetanus toxoid (Connaught) antigens and pokeweed mitogen (PWM; Sigma) at the pre-established final optimal dilutions of 10 μg/ml (candida), 2.5 μg/ml (tetanus), and 10 μg/ml (PWM). The same assay conditions were used for fresh and cryopreserved PBMC, for which 105 viable PBMC were plated in each well. Intralaboratory results were analyzed using median counts per minute (cpm) or stimulation indices (SI) calculated by the ratio of median cpm in antigen- or mitogen-stimulated wells divided by the median cpm in unstimulated control wells. Due to the previously reported high interlaboratory cpm variability (2), interlaboratory comparisons used SI exclusively. Responses to tetanus and candida were defined as SI of ≥3, while responses to PWM were defined by SI of ≥5.

Flow cytometric assays.

Frequencies of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and T-cell subpopulations were determined by flow cytometry, as previously described (http://impaact.s-3.com/immlab.htm) using custom-made premixed monoclonal antibodies manufactured by Becton-Dickinson/Pharmingen, including monoclonal antibodies anti-CD3, -CD4, -CD8, -CD28, -CD38, -CD45RA, -CD45RO, -CD62L, -CD95, and -HLADR. Technical modifications specific to frozen-cell assays are described in the PACTG PBMC cryopreservation protocol (http://www.hanc.info/labs/pages/PBMCSOP.aspx). Of the seven PACTG laboratories, five used Becton Dickinson and two Beckman Coulter flow cytometers. The IQA used a Becton Dickinson flow cytometer for this study.

Statistical analyses.

The statistical significance of all paired comparisons was assessed by means of the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test. Spearman correlation coefficients were used to estimate the correlations between results obtained with fresh versus frozen flow markers and fresh versus frozen LPA SI. P values were not calculated for correlations based on an n value of <5. For analyses in which specimens from the same donors were sent to seven different laboratories, paired comparisons between and correlation analyses of fresh and frozen samples were conducted for each laboratory. These analyses are summarized in the tables by presenting the results from the laboratory having the median value, along with the range across laboratories. Laboratories with median differences between fresh versus frozen conditions or median SI ratios (fresh over frozen) were selected as representative for purposes of graphical illustrations depicting fresh-versus-frozen comparisons. Linear regressions were used to evaluate whether frozen viability, frozen viable recovery, flow markers, or LPA SI declined with increased frozen times. Improvements in frozen viability and viable cell recovery over specimen sendouts were also evaluated for each laboratory by means of linear regressions, with sequential sendouts treated as an ordinal variable. The power to detect differences between freezing methods (−70°C versus liquid nitrogen), given the current sample sizes, was calculated by using the SAS POWER procedure for paired t tests and applying a compensation to adjust for the use of the nonparametric Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test. SAS version 9.1.3 was used for statistical analysis; STATA 8 and S-Plus version 6.0 were used for graphics.

RESULTS

Description of samples and processing.

This study, conducted between April 1999 and March 2006, analyzed PBMC from 49 HIV-infected and 55 uninfected volunteers. Initially, 21 samples were obtained by the IQA from healthy donors; PBMC were tested at the IQA under fresh and after on-site, same-day cryopreservation conditions; both fresh and frozen aliquots were shipped by the IQA to the PACTG laboratories; the PACTG laboratories assayed both the fresh shipped blood samples and the cells frozen at the IQA; the PACTG laboratories also cryopreserved the blood samples shipped fresh from the IQA and assayed the cells that were frozen on site; aliquots of PBMC cryopreserved at the PACTG laboratories were sent back to the IQA, where they were also tested. Subsequent sendouts originated from the IQA and involved one of the following two formats: (i) 28 samples from 26 HIV-infected and 2 uninfected donors were shipped fresh to the seven PACTG laboratories, where PBMC were isolated and cryopreserved and assays were locally performed on both fresh and frozen samples; or (ii) 32 samples from 18 HIV-infected and 14 uninfected donors were used by the IQA to perform fresh blood assays and/or for same-day PBMC cryopreservation, and cryopreserved PBMC were subsequently shipped to the PACTG laboratories, where functional and phenotypic assays were performed on frozen cells only. An additional seven samples from healthy donors (one at each site), identified by the PACTG laboratories, were cryopreserved in multiple aliquots in liquid nitrogen. Different aliquots were tested over time at each site to assess the stability of cryopreserved PBMC. Samples from 5 HIV-infected and 12 uninfected donors were used in optimization assays. The HIV-infected donors had CD4+ cell numbers of ≥200 cells/μl. Plasma HIV RNA copies/ml and antiretroviral treatment data were not collected and may have varied among donors.

Optimization of viability and recovery of cryopreserved PBMC.

To identify factors that may maximize the viability and recovery of cryopreserved PBMC, we investigated the effect of the speed of diluting PBMC after thawing and of benzonase (Novagen) added to the thawing medium at 100 units/ml. The slow method consisted of the following: after bringing the temperature of the PBMC-containing cryovials to 0°C quickly in a water bath, the first 5 ml of wash medium was slowly added over 2 to 3 min in a dropwise fashion. The fast method consisted of rapid addition of the first 5 ml of wash medium. The viability of the frozen PBMC was usually ≥85% and did not vary with the method (not depicted), but slow dilution significantly improved the viable cell recovery, with a mean difference of 32% (95% confidence interval,18 to 45; n = 8). We also found that addition of benzonase increased the viable cell recovery in some cases but not consistently (mean difference of 12% [95% confidence interval = −7 to 31; n = 9]). Addition of benzonase to the thawing medium did not affect the results of functional assays (not depicted). Because of the sizable increase of viable cell recovery associated with the slow dilution method, this was incorporated into the standard PACTG cryopreservation protocol and used in all subsequent experiments. The use of benzonase was left optional.

Viability and recovery of cryopreserved PBMC over time.

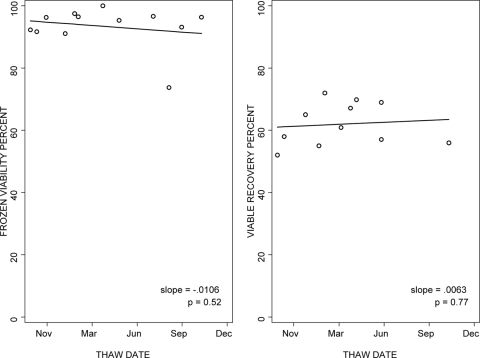

Using the standardized freezing and thawing protocol, the median viability of cryopreserved PBMC was 93% both for samples shipped fresh by the IQA and frozen at the PACTG laboratories and for samples frozen at the IQA and shipped frozen to the PACTG laboratories (ranges of 84% to 99% and n = 21 to 26/laboratory and 88% to 97% and n = 12/laboratory, respectively). The viable cell recovery had a wider variation, with medians of 69% (ranges of 49% to 87% and n = 21 to 26) and 82% (ranges of 40% to 84% and n = 12) for PBMC shipped fresh and frozen, respectively. To evaluate the stability over time of the viability and viable cell recovery of cryopreserved PBMC, large pools of PBMC from healthy volunteers were cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen in multiple aliquots at each laboratory and thawed at regular intervals over 15 months. One laboratory was not included in the analysis, because of a change of donors during the study. The data from the remaining six laboratories did not show any clinically significant changes in cell viability over time, with a median slope of −0.0053 across laboratories (Fig. 1). Likewise, viable cell recovery did not change significantly over time in five of six laboratories, with a median slope of 0.0069 (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Viability and viable cell recovery of cryopreserved PBMC after variable periods of storage in liquid nitrogen. The graphs show the data from the laboratory with typical performance among the six participating laboratories. Data were generated using multiple aliquots of cryopreserved PBMC from a single donor tested after 1 to 15 months of storage in liquid nitrogen. The lines depict the regression of the outcome measure as a function of time.

To determine the effect of cryopreserved PBMC storage conditions on viability and viable cell recovery, paired samples of PBMC frozen at the IQA within 8 h of collection were stored at −70°C for ≤3 weeks or in liquid nitrogen before being shipped on dry ice to the PACTG laboratories (Table 1). Comparisons between these methods of storage revealed no significant differences in cryopreserved PBMC obtained from 17 donors, with respect to viability and viable cell recovery, with mean differences of 1.7% and 0%, respectively (P = 0.46 and 0.51, respectively).

TABLE 1.

Comparison of viability and viable cell recovery of cryopreserved PBMC stored at −70°C versus PBMC stored in liquid nitrogen before shipment

| Parameter | No. of samples | Median difference (%) between cells stored at −70°C or in liquid nitrogen (1st quartile; 3rd quartile) | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frozen viability | 17 | 1.7 (−5.9; 8.1) | 0.46 |

| Viable cell recovery | 17 | 0.0 (−8.0; 16.0) | 0.51 |

Wilcoxon matched-pair signed-rank test. The experiment had >80% power to detect differences of ≥8% in viability and ≥13% in viable cell recovery.

LPA optimization for cryopreserved PBMC.

To evaluate the acceptance parameters of LPA results using cryopreserved PBMC, we investigated the association of LPA SI with viability and viable cell recovery using blood samples from 21 healthy donors in the first cell exchange, performed before standardization of the cryopreservation methods. The difference between the SI obtained with cryopreserved PBMC and SI obtained with fresh PBMC increased across all stimulants, with lower viability of the cryopreserved PBMC (r = −0.82 to −0.54, P ≤ 0.01) (Table 2), indicating that cell viability accounted for a considerable amount of the difference in proliferation between fresh and frozen cells. This correlation diminished when the analysis was restricted to samples with viability levels of ≥75% (r = −0.50 to −0.27, P ≥ 0.12), indicating that among cryopreserved PBMC with viability levels of ≥75%, the viability accounted for a considerably reduced proportion of the difference in proliferation between fresh and frozen cells. There were no significant associations between LPA results and viable cell recovery for any of the stimulants (not depicted).

TABLE 2.

Effect of viability of cryopreserved PBMC on LPA results

| Viability level or stimulant | n | Difference between log10 SI (fresh) and log10 SI (frozen)

|

Spearman correlation

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | Correlation coefficient | P value | ||

| Lower viability | |||||

| Tetanus | 21 | 0.816 | 1.08 | −0.62 | <0.01 |

| Candida | 21 | 0.818 | 1.226 | −0.54 | 0.01 |

| PWM | 21 | 0.143 | −0.376 | −0.82 | <0.0001 |

| Viability ≥75% | |||||

| Tetanus | 11 | 0.281 | 0.232 | −0.21 | 0.53 |

| Candida | 11 | 0.351 | 0.689 | −0.5 | 0.12 |

| PWM | 11 | −0.963 | −0.757 | −0.27 | 0.43 |

To determine the relationship between LPA results with frozen PBMC and results with fresh PBMC, correlation analyses were performed for SI obtained with fresh versus frozen PBMC after tetanus, candida, and PWM stimulation (Table 3). The data showed significant associations for all stimulants in six of seven laboratories that tested PBMC obtained from 26 HIV-infected donors. The median correlations across laboratories were 0.62 for tetanus, 0.63 for candida, and 0.55 for PWM. The median SI ratios between fresh and frozen PBMC across laboratories were 1.1, 1.3, and 1.4 for tetanus, candida, and PWM, respectively. These SI ratios indicated that cryopreservation may slightly lower the SI, but the qualitative analysis of LPA results showed 81%, 88%, and 94% median concordance for tetanus, candida, and PWM, respectively, between LPA results obtained with fresh and frozen PBMC. This indicated that cryopreservation does not interfere significantly with the ability to detect the presence of antigen-specific responses by LPA.

TABLE 3.

Comparability of LPA results obtained with fresh and cryopreserved PBMC

| Stimulant | No. of subjects/lab | Median SI for fresh (frozen) cells | Median (range) SI ratio for fresh/frozen cellsa | Median (range) correlation coefficientsb | No. (%) of labs with significant correlationsc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tetanus | 16-26 | 2.0 (1.6) | 1.10 (0.82 to 1.41) | 0.62 (0.07 to 0.84) | 6 (86) |

| Candida | 16-26 | 44.2 (38.8) | 1.31 (0.29 to 4.65) | 0.63 (−0.41 to 0.85) | 6 (86) |

| PWM | 16-26 | 71.4 (52.8) | 1.44 (1.14 to 2.03) | 0.55 (−0.26 to 0.92) | 6 (86) |

SI ratios of the indicated stimulant in fresh versus frozen PBMC were calculated by dividing the SI of the indicated stimulant in fresh PBMC by the SI of the indicated stimulant in cryopreserved PBMC. The data in the column represent the median SI ratio from the median laboratory and the range of median SI ratios at all laboratories.

Spearman correlation analysis of SI from fresh PBMC and SI from frozen PBMC in each laboratory was used to generate the correlation coefficient. The data indicate the median and range of correlation coefficients among all laboratories.

Significance was defined by P ≤ 0.05.

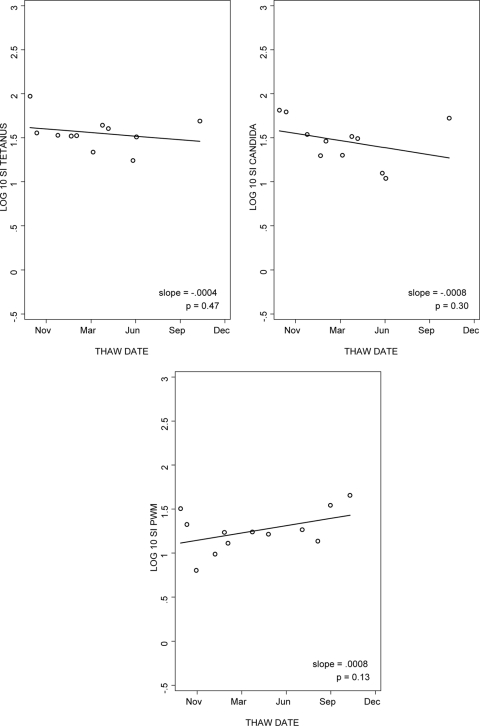

To evaluate the stability of LPA results using PBMC stored in liquid nitrogen for variable periods of time, we analyzed the data from the five laboratories that performed LPA with aliquots of frozen cells obtained from the same donor for 15 months. The median slopes of log SI over time for tetanus, candida, and PWM were −0.0004, −0.0008, and 0.0008 (Fig. 2). Thus, LPA results were relatively stable over the time of cryopreservation, with no overall trend toward lower values. Similar patterns were observed for the log cpm analysis over time (data not depicted).

FIG. 2.

Reproducibility of LPA results for cryopreserved PBMC after variable periods of storage in liquid nitrogen. The data were derived from the laboratory with typical performance. Multiple aliquots from a single donor were tested after 1 to 15 months of storage in liquid nitrogen. The line represents the log SI regression as a function of time.

LPA results were compared between PBMC frozen at the IQA within 8 h of collection and stored for ≤3 weeks at −70°C and PBMC stored in liquid nitrogen before being shipped on dry ice to the PACTG laboratories (Table 4). There were no significant differences in SI by storage method for tetanus (SI ratio for samples at −70°C versus in liquid nitrogen, 0.97; P = 0.9) or candida (SI ratio = 1.17; P = 0.82). Statistically significant higher SI values were observed for PWM-stimulated PBMC stored at −70°C compared with PBMC stored in liquid nitrogen (SI ratio = 1.44; P = 0.02), although the biological relevance of this small difference is unclear. When analyzed in terms of meeting response criteria, LPA results did not show strong differences by method of storage prior to shipment on dry ice, with 69%, 88%, and 100% concordance of the qualitative response to tetanus, candida, and PWM, respectively. For tetanus, fresh and cryopreserved cell assays generated many values relatively close to the response cutoff (SI = 3), resulting in qualitative discordance equally distributed between fresh-cell SI of <3 paired with frozen-cell SI of >3 and vice versa. Of the 17 sets of PBMC, 3 and 4 samples had SI of ≥3 when assayed fresh but of <3 when stored at −70°C or in liquid nitrogen, respectively; 1 and 2 samples had SI of <3 when assayed fresh and ≥3 after storage at −70°C or in liquid nitrogen, respectively.

TABLE 4.

Comparison of LPA results for cryopreserved PBMC stored at −70°C versus PBMC stored in liquid nitrogen before shipment on dry ice

| Stimulant | n | Median SI ratio (1st quartile; 3rd quartile)a | P valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tetanus | 16 | 0.97 (0.55; 2.14) | 0.90 |

| Candida | 16 | 1.17 (0.69; 1.57) | 0.82 |

| PWM | 16 | 1.44 (1.08; 2.48) | 0.02 |

The SI of aliquots stored at −70°C were divided by the SI of aliquots stored in liquid nitrogen. The data are the medians of the SI ratios.

Wilcoxon matched-pair signed-rank test.

A formal analysis of the effect of HIV status on the comparability of LPA results using fresh versus frozen PBMC was not performed, because assays using HIV-infected and uninfected donor blood were performed on different sendouts, thus introducing a potential bias. However, there were no significant differences between fresh and frozen PBMC assay results across sendouts, indicating that the HIV status of the donors may not affect the results.

Flow cytometric enumeration of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.

This was performed by two-color or three-color flow cytometry according to laboratory-specific procedures. The number of gated events was >300 for all experiments but varied amply. Flow purity, defined by the percentage of cells in the analysis gates that are lymphocytes, and recovery, defined by the percentage of lymphocytes in the analysis gate, were recorded for all experiments. The median purity and recovery of any laboratory were ≥92%. The flow-measured purity and recovery did not appreciably change over 15 months of PBMC storage in liquid nitrogen, with median slopes across laboratories of 0.0007 and −0.0007, respectively, with laboratories showing a balanced number of positive and negative slopes, none of which were statistically significant.

Comparisons of the CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell percentages in fresh versus frozen PBMC were performed with 17 to 26 HIV-infected subjects per laboratory (Table 5). The CD4 percentage in frozen PBMC significantly correlated with those measured with fresh PBMC in six of seven laboratories (median r = 0.86; P < 0.0001). The CD8 percentages measured with frozen PBMC were significantly correlated with those measured with fresh PBMC in all seven laboratories (median r = 0.82; P < 0.0001). The median differences between fresh and frozen cells were 0% for CD4 and 1% for CD8, indicating that there was no biologically significant loss or gain of T-cell populations during cryopreservation. To identify acceptance parameters of the results for enumeration of CD4+ or CD8+ T-cells in frozen PBMC, we performed correlation analysis of the differences between the CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell percentages in fresh versus frozen PBMC with cryopreserved PBMC viability, viable cell recovery, flow purity, flow recovery, and number of gated events. We did not find any consensus associations across laboratories.

TABLE 5.

Comparability of flow cytometric enumerations of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in fresh and cryopreserved PBMC

| Phenotype | No. of subjects per lab | Median (%) in fresh (frozen) PBMC | Median difference between % in fresh and % in frozen PBMC (range)a | Median correlation coefficient (range)b | No. (%) of labs with significant correlationsc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4+ | 17-26 | 26 (25) | 0.0 (−3.0-1.0) | 0.86 (0.46-0.94) | 6 (86) |

| CD8+ | 17-26 | 51 (48) | 1.0 (−2.5-3.3) | 0.82 (0.74-0.94) | 7 (100) |

Differences in the percentages of the indicated phenotype in fresh versus frozen PBMC were calculated by subtracting the percentage of the indicated phenotype in cryopreserved PBMC from the percentage of the phenotype in fresh PBMC. The data represent the median differences across all laboratories and the ranges of median differences at individual laboratories.

Spearman correlation analysis of fresh and frozen PBMC in each laboratory was used to generate a coefficient of correlation. The data indicate the median and the range of medians of the coefficient of correlations at individual laboratories.

Significance was defined by P ≤ 0.05.

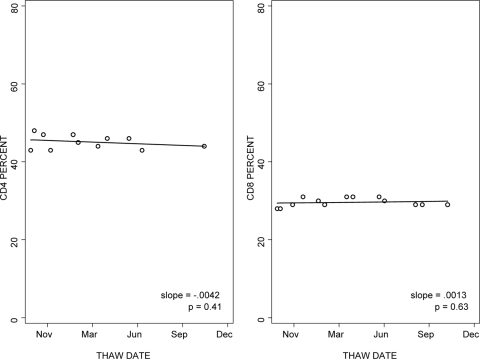

The stability of the CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell percentages in cryopreserved PBMC was analyzed over 15 months of storage in liquid nitrogen. Results were highly reproducible over time in all laboratories, with median slopes of 0.0005 for the CD4 percentage and 0.0023 for the CD8 percentage (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Reproducibility of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell enumeration with cryopreserved PBMC after variable periods of storage in liquid nitrogen. Multiple aliquots from a single donor were tested after 1 to 15 months of storage in liquid nitrogen. The graphs show the results of the laboratory with typical performance. The lines represent the regression analysis of results over time.

The effect of storage at −70°C for ≤3 weeks versus storage in liquid nitrogen before shipment on dry ice was studied with paired blood samples obtained from 17 donors (Table 6). The median differences in the CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell percentages were 0 and 1%, respectively, with P values for the paired comparisons of 0.75 and 0.14, respectively, showing a lack of significant difference between the two processing methods.

TABLE 6.

Comparison of enumerations of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells in cryopreserved PBMC stored at −70°C versus PBMC stored in liquid nitrogen before shipment on dry ice

| Phenotype | No. of samples | Median difference (1st quartile; 3rd quartile)b | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD4 | 17 | 0.0 (−1.0; 2.0) | 0.99 |

| CD8 | 17 | 1.0 (0.0; 1.0) | 0.14 |

Wilcoxon matched-pair signed-rank test. Applied to the sample size of 17, this test had ≥80% power to detect a 3% difference in the percentage of either CD4+ or CD8+.

Median differences are between the percentages of CD4+ or CD8+ in PBMC stored at −70°C and in PBMC in liquid nitrogen.

Phenotypic characterization of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell subpopulations using cryopreserved PBMC.

The ability to enumerate T-cell subpopulations was studied by the expression of the following marker combinations: CD45RA+ CD62L+, CD28+ CD95−, or CD45RA+ CD95− for naïve; CD45RO+ for total memory; CD28+ CD95+ for effector memory; and CD38+ HLADR+ for activated cells. Comparisons of the frequencies of each subpopulation in fresh versus frozen PBMC were performed with samples from 2 to 20 HIV-infected subjects per laboratory (Table 7). Data from ≥83% of participating laboratories showed significant associations between fresh and frozen cell results for naïve (CD4+ CD45RA+ CD95− and CD4+ CD28+ CD95−), effector memory (CD4+ CD28+ CD95+), and activated (CD4+ CD38+ HLADR+ and CD8+ CD38+ HLADR+) cells, with median correlation coefficients of ≥0.73 and P < 0.01 across laboratories. The correlation analysis of the percentage of naïve CD8+ CD28+ CD95− and the percentage of effector memory CD8+ CD28+ CD95+ cells in fresh versus frozen PBMC showed median coefficients of correlation of ≥0.65. However, the results for the percentage of naïve CD8+ CD28+ CD95− and the percentage of effector memory CD8+ CD28+ CD95+ cells in fresh versus frozen PBMC from three and five laboratories, respectively, did not reach statistically significant correlations due to the small sample sizes of three to eight subjects. The median differences between fresh and frozen PBMC for the percentages of CD4+ CD45RA+ CD95−, CD4+ CD28+ CD95−, CD4+ CD28+ CD95+, CD4+ CD38+ HLADR+, and CD8+ CD28+ CD95+ subpopulations represented ≤10% of the fresh-cell population, indicating little change in numbers of these subpopulations during cryopreservation. For the percentages of CD8+ CD38+ HLADR+, the median difference represented 20% of the fresh-cell population, suggesting a loss of cells during cryopreservation. For the percentages of CD8+ CD28+ CD95−, the median difference between fresh- and frozen-cell preparations represented 14% of the median fresh-cell measurements and 10% of the median frozen-cell measurements.

TABLE 7.

Differences and correlations between fresh and cryopreserved PBMC flow cytometric enumeration of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell subpopulations

| Phenotype | No. of subjects per lab | Median % in fresh (frozen) PBMC | Median difference (%) (range) between fresh and frozen PBMCa | Median (range) of correlation coefficientb | No. (%) of labs with significant correlationsc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4+ CD45RA+ CD95− | 11-18 | 36 (34) | −3.0 (−6.0-4.0) | 0.90 (0.51-0.94) | 6 (86) |

| CD4+ CD28+ CD95− | 11-12 | 37 (41) | −3.0 (−8.0-−0.6) | 0.87 (0.76-0.93) | 7 (100) |

| CD4+ CD28+ CD95+ | 11-12 | 57 (52) | 5.7 (−1.4-6.5) | 0.90 (0.81-0.94) | 7 (100) |

| CD4+ CD38+ HLADR+ | 4-12 | 7 (7) | 0.0 (−2.0-1.0) | 0.73 (0.52-0.76) | 5 (83) |

| CD4+ CD45RA+ CD62L+ | 2-8 | 35 (22) | 11.0 (6.0-14.5) | 0.47 (−1.0-0.70) | 0 |

| CD3+ CD4+ CD45RO+ | 3-8 | 18 (15) | 3.0 (−6.0-12.0) | 0.32 (−1.0-1.0) | 0 |

| CD8+ CD28+ CD95− | 3-8 | 7 (10.0) | −1.0 (−9.5-8.0) | 0.65 (0.12-0.92) | 2 (40) |

| CD8+ CD28+ CD95+ | 3-8 | 25 (23) | 1.1 (−2.0-12.0) | 0.74 (−0.50-1.0) | 2 (40) |

| CD8+ CD38+ HLADR+ | 13-20 | 33 (25) | 6.5 (3.0-12.0) | 0.85 (0.76-0.93) | 7 (100) |

Differences of the indicated phenotype in fresh versus frozen PBMC were calculated by subtracting the percentage of the indicated phenotype in cryopreserved PBMC from the percentage of the phenotype in fresh PBMC. The data represent the median difference across all laboratories and the range of median differences at individual laboratories.

Spearman correlation analysis of fresh and frozen PBMC in each laboratory was used to generate a coefficient of correlation. The data indicate the median and the range of medians of the coefficient of correlations at individual laboratories.

Significance, defined by P ≤ 0.05, was calculated only for laboratories that tested PBMC from five or more donors.

We found little correlation between fresh and cryopreserved PBMC enumerations of naïve cells characterized by the percentage of CD4+ CD45RA+ CD62L+ or memory cells characterized by the percentage of CD3+ CD4+ CD45RO+, with coefficients of correlation of ≤0.47. The median differences between fresh and frozen PBMC preparations for these two marker combinations represented 31% and 17%, respectively, of the fresh-cell populations, suggesting a significant loss of cells or marker signal during cryopreservation.

Differences in the proportions of T-cell subpopulations between fresh and frozen PBMC did not show a consistent pattern of association with cryopreserved PBMC viability, viable cell recovery, flow cytometry-measured purity, or recovery across laboratories.

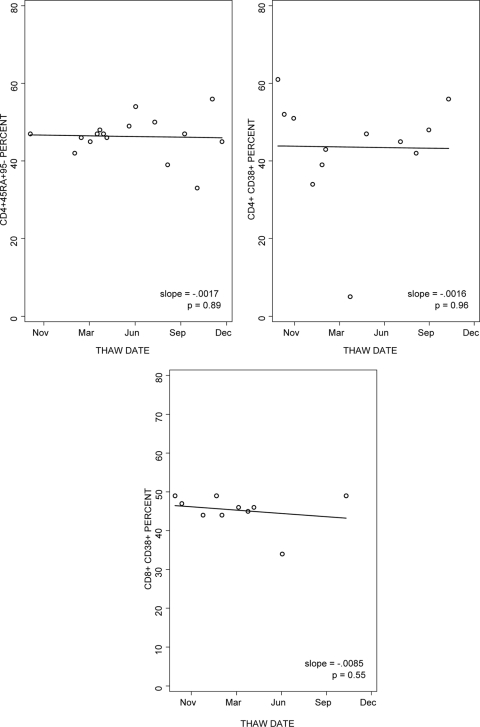

The stability over time of the percentages of naïve CD4+ CD45RA+ CD95− and of the percentages of CD4+ CD38+ and CD8+ CD38+ in cryopreserved PBMC was analyzed (Fig. 4). The data showed slopes over time of close to 0 in six of six laboratories for the percentage of CD4+ CD45RA+ CD95− (median slope = −0.0002), five of six laboratories for the percentage of CD4+ CD38+ (median slope = −0.0012), and four of six laboratories for the percentage of CD8+ CD38+ (median slope = −0.0003).

FIG. 4.

Reproducibility of the enumeration of the percentages of CD4+ CD45RA+ CD95−, CD4+ CD38+, and CD8+ CD38+ in cryopreserved PBMC after variable periods of storage in liquid nitrogen. The graphs show the results of the laboratory with typical performance. Multiple aliquots of PBMC from a single donor cryopreserved on a single occasion were tested after 1 to 15 months of storage in liquid nitrogen. The lines represent regression analyses.

The effect of storage at −70°C versus storage in liquid nitrogen prior to shipment on dry ice was examined for 17 PBMC preparations cryopreserved within 8 h of collection (Table 8). Median differences of −1%, 0%, and 0% for the percentages of CD4+ CD45RA+ CD95−, CD4+ CD38+ HLADR+, and CD8+ CD38+ HLADR+, respectively, were observed between results for samples stored at −70°C versus those stored in liquid nitrogen (P = 0.13, 0.78, and 0.25, respectively).

TABLE 8.

Comparison of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell subpopulations enumerated with cryopreserved PBMC stored at −70°C versus PBMC stored in liquid nitrogen before shipment on dry ice

| T-cell subpopulation | No. of samples | Median difference (%) between −70°C and liquid nitrogen storage (1st; 3rd quartile) | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD4+ CD38+ HLADR+ | 16 | 0.0 (−1.0; 0.5) | 0.78 |

| CD4+ CD45RA+ CD95− | 16 | −1.0 (−2.0; 0.5) | 0.13 |

| CD8+ CD38+ HLADR+ | 16 | 0.0 (0.0; 1.0) | 0.25 |

Wilcoxon matched-pair signed-rank test. This test, applied to the sample size of 16, had statistical power to detect differences of 2.3%, 1%, and 2.7% in the percentages of CD4+ CD38+ HLADR+, CD4+ CD45RA+ CD95−, and CD8+ CD38+ HLADR+, respectively.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we evaluated the feasibility of high-complexity immunologic assays using cryopreserved PBMC. The data showed that results of immunologic assays using fresh and frozen PBMC generally correlate very well, such that differences, when present, tended to be consistent across subjects. Furthermore, most of the results were highly reproducible across multiple laboratories. For the areas where the laboratories were consistent, it is reasonable to assume that the results could be further generalized to other laboratories using similar equipment and methods. Our overall results provide support for the use of cryopreserved PBMC for high-complexity immunologic assays, with the caveat that a mixture of fresh and frozen results in the same analysis is counterindicated for many assays.

The viability of the cryopreserved PBMC was the most important determinant of the quality and reliability of the results of functional assays, with a viability of 75% being the threshold for acceptance of LPA results. Although the viable cell recovery in cryopreserved PBMC was not a critical determinant of the quality or reliability of the results of immunologic assays, it has the potential of limiting assay feasibility because it may create a shortage of usable cells. In this study, we identified two technical aspects that improved the viable cell recovery: (i) diluting the cells slowly after a quick thaw, which consistently improved viable cell recovery; and (ii) the use of benzonase in the thawing medium, which only sometimes had a beneficial effect on viable cell recovery. Of note, benzonase did not alter the results of functional or immunophenotypic assays.

Enumeration of CD4+ and CD8+ cells by flow cytometry showed an excellent correlation between fresh and cryopreserved PBMC, without any significant differences in the CD4+ or CD8+ T-cell percentages between cell preparations. This obviates the need to establish cryopreserved cell-specific normative data for the CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell percentages.

With respect to the use of cryopreserved PBMC to enumerate T-cell subpopulations, we established the lack of stability of CD62L and CD45RO through the freezing process. However, we determined that both CD45RA+ CD95− and CD28+ CD95− marker combinations identify naïve CD4+ T cells without introducing significant differences between fresh and frozen cells and that memory T cells could be enumerated using CD45RA− as a marker. Memory and activated CD4+ or CD8+ T cells expressing CD28+ CD95+ and CD38+ HLADR+, respectively, were strongly correlated between fresh and frozen PBMC preparations but were significantly diminished in cryopreserved compared with fresh PBMC, possibly due to the fragility of these cell populations.

Differences between fresh and frozen PBMC with respect to the total CD4+ or CD8+ T-cell percentage or subpopulations were not associated with flow purity or recovery, viability, viable cell recovery, or the number of gated events in assays performed on cryopreserved PBMC. These observations have to be interpreted with caution because the viability, flow purity, recovery, and number of gated events were consistently high across most samples, and the ranges were relatively narrow, which may have obfuscated the effect of these parameters on the quality of the flow cytometry results. Nevertheless, an acceptance parameter for flow cytometry results related to the quality of the cryopreserved PBMC or technical aspects of the assays was not found.

To define the characteristics of functional assays using cryopreserved PBMC, we measured proliferative responses to tetanus, candida, and PWM. The LPA measures memory T-cell responses. Compared with other functional assays, such as the enzyme-linked immunospot assay or intracellular cytokine detection, the LPA requires that T cells not only retain their ability to recognize cognate antigens and secrete cytokines, but also multiply. The value of proliferation-based functional assays is further supported by their frequently unique ability to correlate with protection against development of infections or disease progression (10, 12). The stimulants used in this study typically result in a range of SI. The comparison of fresh versus frozen PBMC showed high median correlations across laboratories for all antigens. SI for frozen PBMC tended to be slightly lower than those for fresh PBMC across antigens and mitogen, but the qualitative LPA results were comparable between frozen and fresh PBMC, indicating that LPA results obtained with cryopreserved PBMC with viability of ≥75% generally represent the ability of the cells to respond to the antigenic or mitogenic stimulation, independent of the nature or intensity of the stimulus.

In this study, we found that viability and recovery of cryopreserved PBMC were conserved for up to 15 months of storage in liquid nitrogen, as were all other immunologic assay results. Others have not been able to demonstrate similar stability of cryopreserved PBMC (13). Decreased viability and function of cryopreserved PBMC are typically associated with temperature variations during storage (13, 16). This may occur when cells are stored close to the surface of the liquid nitrogen container and/or upon frequently accessing the container. Other potential factors are changes in processing technique and personnel over time.

We also investigated the immunologic parameters that may be affected by shipping cells on dry ice after storage in liquid nitrogen compared with storage in a −70°C freezer for up to 3 weeks, which has previously been shown to preserve the function of PBMC measured by an enzyme-linked immunospot assay (3). There were no appreciable differences in viability, recovery, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, T-cell subpopulations, or LPA-measured responses to microbial antigenic stimulation. In contrast to tetanus- and candida-specific SI, the SI obtained with PWM stimulation were slightly higher in cells stored at −70°C than those in cells stored in liquid nitrogen, a difference that reached statistical significance. This difference between the antigen- versus mitogen-stimulated LPA responses of cells stored in liquid nitrogen versus cells stored at −70°C could not be ascribed solely to the differences in the magnitudes of the responses, because candida-stimulated SI were often of the same magnitude as that of the SI obtained with PWM. A potential explanation is that tetanus and candida generate primarily a CD4+ T-cell-mediated proliferative response, whereas PWM stimulates proliferation of all lymphocytes. It is conceivable that the function of lymphocyte populations other than the CD4+ T cells may be affected by storage in liquid nitrogen followed by shipment on dry ice. Nevertheless, it is important to underscore that even in the case of PWM LPA, the differences in SI introduced by storage in liquid nitrogen prior to shipment on dry ice were small and did not translate into qualitative differences. Collectively, our data indicate that cells stored in liquid nitrogen can be transported on dry ice and subsequently used in functional or phenotypic assays without losing the ability to obtain meaningful results.

Comparisons between fresh and frozen PBMC performed in this study used blood samples from HIV-infected and uninfected individuals. However, because only two sendouts included samples from both types of donors, we did not perform a formal statistical comparison between the quality of the results obtained on cryopreserved PBMC from HIV-infected versus uninfected individuals. Since the overall differences between fresh and frozen PBMC did not vary by sendout (data not shown), it is reasonable to assume that there were no differences between HIV-infected and uninfected individuals, with respect to feasibility of immunologic assay with cryopreserved PBMC, which is in accordance with previous reports (19). In this study, HIV-infected subjects uniformly had ≥200 CD4+ cells/μl, and variable plasma HIV RNA copies/ml or treatment. Further studies are needed to determine if these findings can be extended to HIV-infected subjects with <200 CD4+ cells/μl.

In conclusion, cryopreserved PBMC have stable viability and function over prolonged periods of time when adequately stored and can be used in substitution of fresh PBMC for several phenotypic and functional assays. Due to differences in function and distribution of T-cell subpopulations between fresh and frozen PBMC, it is recommended to use the same cell preparation within individual studies. Some variation across laboratories was observed, indicating the need for training and standardization.

Acknowledgments

We thank Daniella Livnat for support of this project, Rebecca Gelman for critical review of the manuscript and helpful suggestions, and Annie Vazquez for assistance with manuscript preparation.

This study was supported by contracts N01-HD-33162 (A.W.), N01-AI-95356, and U01-AI-068632 and by the Colorado Center for AIDS Research Grant P30 AI054907.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases or the National Institutes of Health.

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 10 June 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Autran, B., G. Carcelain, T. S. Li, C. Blanc, D. Mathez, R. Tubiana, C. Katlama, P. Debre, and J. Leibowitch. 1997. Positive effects of combined antiretroviral therapy on CD4+ T cell homeostasis and function in advanced HIV disease. Science 277112-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Betensky, R. A., E. Connick, J. Devers, A. L. Landay, M. Nokta, S. Plaeger, H. Rosenblatt, J. L. Schmitz, F. Valentine, D. Wara, A. Weinberg, and H. M. Lederman. 2000. Shipment impairs lymphocyte proliferative responses to microbial antigens. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 7759-763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bull, M., D. Lee, J. Stucky, Y. L. Chiu, A. Rubin, H. Horton, and M. J. McElrath. 2007. Defining blood processing parameters for optimal detection of cryopreserved antigen-specific responses for HIV vaccine trials. J. Immunol. Methods 32257-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costantini, A., S. Mancini, S. Giuliodoro, L. Butini, C. M. Regnery, G. Silvestri, and M. Montroni. 2003. Effects of cryopreservation on lymphocyte immunophenotype and function. J. Immunol. Methods 278145-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dyer, W. B., S. L. Pett, J. S. Sullivan, S. Emery, D. A. Cooper, A. D. Kelleher, A. Lloyd, and S. R. Lewin. 2007. Substantial improvements in performance indicators achieved in a peripheral blood mononuclear cell cryopreservation quality assurance program using single donor samples. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 1452-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horton, H., E. P. Thomas, J. A. Stucky, I. Frank, Z. Moodie, Y. Huang, Y. L. Chiu, M. J. McElrath, and S. C. De Rosa. 2007. Optimization and validation of an 8-color intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) assay to quantify antigen-specific T cells induced by vaccination. J. Immunol. Methods 32339-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hviid, L., G. Albeck, B. Hansen, T. G. Theander, and A. Talbot. 1993. A new portable device for automatic controlled-gradient cryopreservation of blood mononuclear cells. J. Immunol. Methods 157135-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kierstead, L. S., S. Dubey, B. Meyer, T. W. Tobery, R. Mogg, V. R. Fernandez, R. Long, L. Guan, C. Gaunt, K. Collins, K. J. Sykes, D. V. Mehrotra, N. Chirmule, J. W. Shiver, and D. R. Casimiro. 2007. Enhanced rates and magnitude of immune responses detected against an HIV vaccine: effect of using an optimized process for isolating PBMC. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 2386-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kleeberger, C. A., R. H. Lyles, J. B. Margolick, C. R. Rinaldo, J. P. Phair, and J. V. Giorgi. 1999. Viability and recovery of peripheral blood mononuclear cells cryopreserved for up to 12 years in a multicenter study. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 614-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lambotte, O., F. Boufassa, Y. Madec, A. Nguyen, C. Goujard, L. Meyer, C. Rouzioux, A. Venet, and J. F. Delfraissy. 2005. HIV controllers: a homogeneous group of HIV-1-infected patients with spontaneous control of viral replication. Clin. Infect. Dis. 411053-1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maecker, H. T., A. Rinfret, P. D'Souza, J. Darden, E. Roig, C. Landry, P. Hayes, J. Birungi, O. Anzala, M. Garcia, A. Harari, I. Frank, R. Baydo, M. Baker, J. Holbrook, J. Ottinger, L. Lamoreaux, C. L. Epling, E. Sinclair, M. A. Suni, K. Punt, S. Calarota, S. El-Bahi, G. Alter, H. Maila, E. Kuta, J. Cox, C. Gray, M. Altfeld, N. Nougarede, J. Boyer, L. Tussey, T. Tobery, B. Bredt, M. Roederer, R. Koup, V. C. Maino, K. Weinhold, G. Pantaleo, J. Gilmour, H. Horton, and R. P. Sekaly. 2005. Standardization of cytokine flow cytometry assays. BMC Immunol. 613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martinez, V., D. Costagliola, O. Bonduelle, N. N′go, A. Schnuriger, I. Theodorou, J. P. Clauvel, D. Sicard, H. Agut, P. Debre, C. Rouzioux, and B. Autran. 2005. Combination of HIV-1-specific CD4 Th1 cell responses and IgG2 antibodies is the best predictor for persistence of long-term nonprogression. J. Infect. Dis. 1912053-2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Owen, R. E., E. Sinclair, B. Emu, J. W. Heitman, D. F. Hirschkorn, C. L. Epling, Q. X. Tan, B. Custer, J. M. Harris, M. A. Jacobson, J. M. McCune, J. N. Martin, F. M. Hecht, S. G. Deeks, and P. J. Norris. 2007. Loss of T cell responses following long-term cryopreservation. J. Immunol. Methods 32693-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reimann, K. A., M. Chernoff, C. L. Wilkening, C. E. Nickerson, A. L. Landay, et al. 2000. Preservation of lymphocyte immunophenotype and proliferative responses in cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells from human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected donors: implications for multicenter clinical trials. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 7352-359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shearer, W. T., H. M. Rosenblatt, R. S. Gelman, R. Oyomopito, S. Plaeger, E. R. Stiehm, D. W. Wara, S. D. Douglas, K. Luzuriaga, E. J. McFarland, R. Yogev, M. H. Rathore, W. Levy, B. L. Graham, and S. A. Spector. 2003. Lymphocyte subsets in healthy children from birth through 18 years of age: the Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group P1009 study. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 112973-980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith, J. G., H. R. Joseph, T. Green, J. A. Field, M. Wooters, R. M. Kaufhold, J. Antonello, and M. J. Caulfield. 2007. Establishing acceptance criteria for cell-mediated-immunity assays using frozen peripheral blood mononuclear cells stored under optimal and suboptimal conditions. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 14527-537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weinberg, A., R. A. Betensky, L. Zhang, and G. Ray. 1998. Effect of shipment, storage, anticoagulant, and cell separation on lymphocyte proliferation assays for human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 5804-807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weinberg, A., C. Tierney, M. A. Kendall, R. J. Bosch, J. Patterson-Bartlett, A. Erice, M. S. Hirsch, and B. Polsky. 2006. Cytomegalovirus-specific immunity and protection against viremia and disease in HIV-infected patients in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J. Infect. Dis. 193488-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weinberg, A., L. Zhang, D. Brown, A. Erice, B. Polsky, M. S. Hirsch, S. Owens, and K. Lamb. 2000. Viability and functional activity of cryopreserved mononuclear cells. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 7714-716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]