Abstract

Vibrio cholerae causes the disease cholera and inhabits aquatic environments. One key factor in the environmental survival of V. cholerae is its ability to form matrix-enclosed, surface-associated microbial communities known as biofilms. Mature biofilms rely on Vibrio polysaccharide to connect cells to each other and to a surface. We previously described a core regulatory network, which consists of two positive transcriptional regulators, VpsR and VpsT, and a negative transcriptional regulator HapR, that controls biofilm formation by regulating the expression of vps genes. In this study, we report the identification of a sensor histidine kinase, VpsS, which can control biofilm formation and activates the expression of vps genes. VpsS required the response regulator VpsR to activate vps expression. VpsS is a hybrid sensor histidine kinase that is predicted to contain both histidine kinase and response regulator domains, but it lacks a histidine phosphotransferase (HPT) domain. We determined that VpsS acts through the HPT protein LuxU, which is involved in a quorum-sensing signal transduction network in V. cholerae. In vitro analysis of phosphotransfer relationships revealed that LuxU can specifically reverse phosphotransfer to CqsS, LuxQ, and VpsS. Furthermore, mutational and phenotypic analyses revealed that VpsS requires the response regulator LuxO to activate vps expression, and LuxO positively regulates the transcription of vpsR and vpsT. The induction of vps expression via VpsS was also shown to occur independent of HapR. Thus, VpsS utilizes components of the quorum-sensing pathway to modulate biofilm formation in V. cholerae.

Vibrio cholerae, the causative agent of the diarrheal disease cholera, is a natural inhabitant of aquatic environments (14). The environmental survival and transmission of V. cholerae are facilitated by its ability to form biofilms (1, 15), which are surface-associated microbial communities composed of microorganisms and the extrapolymeric substances that they produce (10). The ability of V. cholerae to form biofilms depends on the production of the major extracellular matrix component Vibrio polysaccharide (VPS). VPS is produced by proteins encoded by the vps genes, which are organized into the vps-I (vpsU [VC0916], vpsA to vpsK [VC0917 to VC0927]) and vps-II (vpsL to vpsQ [VC0934 to VC0939]) coding regions (41).

The regulation of vps expression and biofilm formation in V. cholerae involves multiple two-component signal transduction proteins. A typical two-component system consists of a sensor histidine kinase (HK) and a response regulator (RR) (for a review, see reference 37). A stimulus received by the HK initiates a phosphorelay event. The HK autophosphorylates at a conserved histidine residue, and the phosphoryl group is then transferred to a conserved aspartate residue on the RR. Phosphorylation of the RR leads to activation and altered protein function or regulation of gene expression. More complex multicomponent systems can consist of hybrid HK proteins containing both HK and RR domains, proteins harboring histidine phosphotransferase (HPT) domains, and RRs. In these cases, the received stimulus results in autophosphorylation of a conserved histidine residue on the HK domain of the hybrid kinase, which in turn transfers the phosphoryl group intramolecularly to the conserved aspartate residue on the RR domain. The HPT then acts as an intermediate receiver and donor of the phosphoryl group for the RR domain of the hybrid kinase and another RR (24, 37). HPT domains can occur on the same protein with HK and RR domains or on separate proteins.

In V. cholerae, a quorum-sensing signal transduction system negatively regulates biofilm formation (17). In quorum sensing, bacteria produce signaling molecules termed autoinducers (AIs) that are secreted and accumulate in the medium in proportion to the population density. V. cholerae produces two AIs, known as cholerae autoinducer-1 (CAI-1) and autoinducer-2 (AI-2), that are detected via the hybrid HKs CqsS and LuxQ, respectively (17, 32). At a low cell density when the AI concentration is low, CqsS and LuxQ act as kinases and are autophosphorylated. Information from the sensors is then transduced through a phosphorelay, first to the HPT protein LuxU and then to the σ54-dependent RR LuxO (32, 43). Phosphorylated LuxO then activates the transcription of four genes encoding the Qrr regulatory small RNAs (sRNAs), which destabilize the mRNA encoding the quorum-sensing master regulator, HapR (27). When the cell density is high, the AI concentration is high; LuxQ and CqsS bind their respective AIs and act as phosphatases. Under such conditions, LuxU and LuxO are unphosphorylated and HapR is produced at high levels, leading to a decrease in vps expression. A mutation in HapR leads to increased production of VPS, indicating that one of the normal roles of HapR is to suppress biofilm formation (17, 40, 42).

VpsR, a positive regulator of vps expression, exhibits homology to the NtrC subclass of two-component response regulators (39). Disruption of vpsR prevents expression of the vps genes and production of VPS and abolishes formation of the typical three-dimensional biofilm structure, demonstrating that VpsR is required for biofilm formation. In a typical two-component system, VpsR is phosphorylated by an HK. Indeed, VpsR contains the conserved aspartate residue (D59) that is predicted to be necessary for phosphorylation. Conversion of this aspartate to alanine renders VpsR inactive, while conversion to glutamate generates a constitutively active VpsR, supporting the premise that phosphorylation controls the activity of VpsR (25). A second positive regulator of vps expression is VpsT, which is similar to proteins belonging to the UhpA (FixJ) family of transcriptional regulators (8). Disruption of vpsT reduces vps gene expression and reduces the capacity to form biofilms. While VpsR is essential for VPS production and biofilm formation, VpsT plays an accessory role, possibly by increasing the level or activity of VpsR (3, 8).

To better understand the regulatory network controlling biofilm formation, we attempted to identify the cognate HK for VpsR and searched for HKs regulating vps gene expression. In this study, we report the identification of a hybrid HK, VpsS, which positively regulates vps gene expression. VpsS requires the presence of VpsR and the quorum-sensing signal transduction proteins LuxU and LuxO to induce vps expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. All V. cholerae and Escherichia coli strains were grown aerobically at 30°C and 37°C, respectively, unless otherwise noted. The growth medium was Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 1% NaCl; pH 7.5). LB agar contained 1.5% (wt/vol) granulated agar (Difco). The concentrations of antibiotics used, where appropriate, were as follows: ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; rifampin, 100 μg/ml; kanamycin, 50 μg/ml; and gentamicin, 30 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant properties | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| TOP10 | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 recA1 araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7697 galU galK rpsL (Smr) endA1 nupG | Invitrogen |

| CC118(λpir) | Δ(ara-leu) araD ΔlacX74 galE galK phoA20 thi-1 rpsE rpoB argE(Am) recA1 λpir | 19 |

| S17-1(λpir) | Tpr Smr, recA thi pro rK− mK+ RP4:2-Tc:MuKm Tn7 λpir | 12 |

| V. cholerae strains | ||

| FY_Vc_1 | Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor A1552, smooth variant, Rifr | 39 |

| FY_Vc_237 | FY_Vc_1, mTn7-gfp, Gmr | 4 |

| FY_Vc_616 | vpsLp-lacZ, Rifr | 35 |

| FY_Vc_2402 | vpsLp-lacZ ΔvpsS, Rifr | This study |

| FY_Vc_2715 | vpsLp-lacZ ΔvpsV, Rifr | This study |

| FY_Vc_2405 | vpsLp-lacZ ΔvpsR, Rifr | 35 |

| FY_Vc_3884 | vpsLp-lacZ vpsR(D59A), Rifr | This study |

| FY_Vc_3887 | vpsLp-lacZ vpsR(D59E), Rifr | This study |

| FY_Vc_3463 | vpsLp-lacZ ΔvpsT, Rifr | 35 |

| FY_Vc_3900 | vpsLp-lacZ ΔvpsR ΔvpsT, Rifr | This study |

| FY_Vc_2398 | vpsLp-lacZ ΔluxU, Rifr | This study |

| FY_Vc_2394 | vpsLp-lacZ ΔVC1080, Rifr | This study |

| FY_Vc_3445 | vpsLp-lacZ ΔVC2038, Rifr | This study |

| FY_Vc_3386 | vpsLp-lacZ ΔluxQ, Rifr | This study |

| FY_Vc_3389 | vpsLp-lacZ ΔcqsS, Rifr | This study |

| FY_Vc_3392 | vpsLp-lacZ ΔluxQ ΔcqsS, Rifr | This study |

| FY_Vc_3395 | vpsLp-lacZ ΔluxQ ΔvpsS, Rifr | This study |

| FY_Vc_3398 | vpsLp-lacZ ΔcqsS ΔvpsS, Rifr | This study |

| FY_Vc_3401 | vpsLp-lacZ ΔluxQ ΔcqsS ΔvpsS, Rifr | This study |

| FY_Vc_2469 | vpsLp-lacZ ΔluxO, Rifr | This study |

| FY_Vc_3841 | vpsLp-lacZ ΔhapR, Rifr | This study |

| FY_Vc_3466 | vpsLp-lacZ ΔhapR ΔluxO, Rifr | This study |

| FY_Vc_4169 | vpsTp-lacZ, Rifr | This study |

| FY_Vc_4178 | vpsTp-lacZ ΔluxO, Rifr | This study |

| FY_Vc_4166 | vpsRp-lacZ, Rifr | This study |

| FY_Vc_4175 | vpsRp-lacZ ΔluxO, Rifr | This study |

| FY_Vc_4286 | vpsLp-lacZ mTn7-luxO, Rifr | This study |

| FY_Vc_4288 | vpsLp-lacZ ΔluxO mTn7-luxO, Rifr | This study |

| FY_Vc_4290 | vpsLp-lacZ ΔhapR mTn7-luxO, Rifr | This study |

| FY_Vc_4292 | vpsLp-lacZ ΔhapR ΔluxO mTn7-luxO, Rifr | This study |

| FY_Vc_4310 | vpsLp-lacZ ΔVCA0939, Rifr | This study |

| FY_Vc_4313 | vpsLp-lacZ ΔVCA0939 ΔluxO, Rifr | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBAD/myc-His-B | Arabinose-inducible expression vector with C-terminal myc epitope and six-His tags | Invitrogen |

| pFY-672 | pBAD/myc-His-B::VC0303, Apr | This study |

| pFY-673 | pBAD/myc-His-B::VC1831, Apr | This study |

| pFY-873 | pBAD/myc-His-B::VCA0709, Apr | This study |

| pFY-774 | pBAD/myc-His-B::VCA0719, Apr | This study |

| pFY-674 | pBAD/myc-His-B::chiS, Apr | This study |

| pFY-670 | pBAD/myc-His-B::cqsS, Apr | This study |

| pFY-671 | pBAD/myc-His-B::luxQ, Apr | This study |

| pFY-875 | pBAD/myc-His-B::varS, Apr | This study |

| pFY-564 | pBAD/myc-His-B::vpsS, Apr | This study |

| pFY-565 | pBAD/myc-His-B::vpsV, Apr | This study |

| pGP704-sacB28 | pGP704 derivative, mob/oriT sacB, Apr | 8 |

| pFY-217 | pGP704-sac28::vpsLp-lacZ transcriptional fusion, Apr | 35 |

| pFY-717 | pGP704-sac28::vpsTp-lacZ transcriptional fusion, Apr | This study |

| pFY-716 | pGP704-sac28::vpsRp-lacZ transcriptional fusion, Apr | This study |

| pFY-475 | pGP704-sac28::ΔvpsS, Apr | This study |

| pFY-563 | pGP704-sac28::ΔvpsV, Apr | This study |

| pFY-277 | pGP704-sac28::ΔvpsSΔvpsV, Apr | This study |

| pFY-16 | pGP704-sac28::ΔvpsR, Apr | 39 |

| pFY-214 | pGP704-sac28::vpsR(D49A), Apr | This study |

| pFY-215 | pGP704-sac28::vpsR(D49E), Apr | This study |

| pFY-15 | pGP704-sac28::ΔvpsT, Apr | 8 |

| pFY-9 | pGP704-sac28::ΔhapR, Apr | 40 |

| pFY-477 | pGP704-sac28::ΔluxU, Apr | This study |

| pFY-538 | pGP704-sac28::ΔVC1080, Apr | This study |

| pFY-732 | pGP704-sac28::ΔVC2038, Apr | This study |

| pFY-153 | pGP704-sac28::ΔVCA0939, Apr | This study |

| pFY-734 | pGP704-sac28::ΔluxQ, Apr | This study |

| pFY-733 | pGP704-sac28::ΔcqsS, Apr | This study |

| p28-luxO | pGP704-sac28::ΔluxO, Apr | 30 |

| pUX-BF13 | oriR6K helper plasmid, mob/oriT, provides the Tn7 transposition function in trans, Apr | 2 |

| pMCM11 | pGP704::mTn7-gfp, Gmr Apr | G. Schoolnik |

| pFY-720 | pGP704::mTn7, Gmr Apr | This study |

| pFY-724 | pGP704-Tn7-luxO, Gmr Apr, pGP704-Tn7 containing luxO promoter and coding regions | This study |

| pENTR/D-TOPO | ENTRY vector for Gateway cloning system, Kanr | Invitrogen |

| pFY-607 | pENTR-CqsS-HK, HK domain of cqsS in pENTR/D-TOPO | This study |

| pFY-608 | pENTR-CqsS-RD, RR RD of cqsS in pENTR/D-TOPO | This study |

| pFY-611 | pENTR-LuxQ-HK, HK of luxQ in pENTR/D-TOPO | This study |

| pFY-612 | pENTR-LuxQ-RD, RD of luxQ in pENTR/D-TOPO | This study |

| pFY-609 | pENTR-LuxO-RD, RD of luxO in pENTR/D-TOPO | This study |

| pFY-610 | pENTR-LuxO-Full, full length of luxO in pENTR/D-TOPO | This study |

| pFY-613 | pENTR-LuxU, full length of luxU in pENTR/D-TOPO | This study |

| pFY-614 | pENTR-VpsR-RD, RD of vpsR in pENTR/D-TOPO | This study |

| pFY-615 | pENTR-VpsR-Full, full length of luxO in pENTR/D-TOPO | This study |

| pFY-616 | pENTR-VpsS-HK, HK of vpsS in pENTR/D-TOPO | This study |

| pFY-617 | pENTR-VpsS-RD, RD of vpsS in pENTR/D-TOPO | This study |

| pFY-618 | pENTR-VpsS-Full, full length of vpsS in pENTR/D-TOPO | This study |

| pFY-619 | pENTR-VC0303-RD, RD of VC0303 in pENTR/D-TOPO | This study |

| pFY-620 | pENTR-VC1831-RD, RD of VC1831 in pENTR/D-TOPO | This study |

| pFY-727 | pENTR-ChiS-RD, RD of chiS in pENTR/D-TOPO | This study |

| pFY-728 | pENTR-VieS-RD, RD of vieS in pENTR/D-TOPO | This study |

| pFY-730 | pENTR-VC2369-RD, RD of VC2369 in pENTR/D-TOPO | This study |

| pFY-731 | pENTR-VarS-RD, RD of varS in pENTR/D-TOPO | This study |

Generation of in-frame deletion mutants and lacZ reporter and gfp-tagged strains.

Deletion mutants, reporter strains carrying promoter regions of either vpsL, vpsT, or vpsR fused to lacZ (vpsLp-lacZ, vpsTp-lacZ, and vpsRp-lacZ) inserted into the lacZ locus on the chromosome, and gfp-tagged strains were generated with the V. cholerae strains using the protocols described previously (16, 28, 35). vpsR(D59A) and vpsR(D59E) point mutations were introduced by amplifying coding regions of vpsR with primers vpsR_5′, vpsR_3′, vpsR_D59A_F, vpsR_D59A_R, vpsR_D59E_F, and vpsR_D59E_R and joining them together using splicing by overlap extension (26). To introduce the mutated version of vpsR into the chromosome, 5′ and 3′ regions of vpsR were amplified with vpsR_5′_F, vpsR_5′_R, vpsR_3′_F, and vpsR_3′_R, ligated to the splicing-by-overlap-extension product, and cloned into the suicide vector pGP704-sacB28. Primers used in this study are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Deletion mutants, reporter strains, and gfp-tagged strains were verified by PCR.

Recombinant DNA techniques.

DNA manipulations were carried out using standard molecular techniques (33). Restriction and DNA modification enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs. PCRs were carried out using primers purchased from Operon Technologies (Alameda, CA) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) and a high-fidelity PCR kit (Roche). Construction of vpsR site-directed mutagenesis plasmids harboring point mutations was carried out using a previously described protocol (5). Overexpression plasmids were generated using the pBAD/myc-His B vector (Invitrogen). Sequences of the plasmids that were constructed were verified by DNA sequencing.

Flow cell experiments and CLSM.

Flow cell experiments were carried out using a procedure described previously (20, 28). Briefly, chambers were sterilized with 0.5% (vol/vol) hypochlorite overnight, and this was followed by addition of sterile MilliQ water and 2% LB medium (0.2 g/liter tryptone, 0.1 g/liter yeast extract, 1% NaCl) at a flow rate of 4.5 ml/h. Overnight cultures of gfp-tagged V. cholerae strains were diluted to obtain an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1, and 350-μl aliquots of the diluted cultures were inoculated by injection into the flow cell chambers. After inoculation, the chambers were allowed to stand inverted, with no flow, for 1 h. The flow was resumed at a rate of 4.5 ml/h with the chambers standing upright. Flow cell experiments were carried out at room temperature with 2% LB medium containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and arabinose (0.2%, wt/vol), when they were needed. Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) images of the biofilms were captured with an LSM 5 PASCAL system (Zeiss) using an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and an emission wavelength of 543 nm. Three-dimensional images of the biofilms were reconstructed using Imaris software (Bitplane) and quantified using COMSTAT (21). Flow cell experiments were carried out with at least two biological replicates.

β-Galactosidase assays.

β-Galactosidase assays were performed using exponentially grown cultures by first growing V. cholerae overnight (18 to 20 h) aerobically in LB medium. The cells were then diluted 1:200 in fresh LB medium and grown aerobically to an OD600 of 0.3 to 0.4. Cells were then diluted again 1:200 in LB medium, allowed to grow to an OD600 of 0.3 to 0.4, and immediately harvested for assays. β-Galactosidase assays with cells overexpressing vpsS were carried out with overnight cultures grown in the absence of arabinose that were diluted 1:200 or 1:500 in fresh media with and without the inducer 0.2% arabinose. Assays were then performed 3 and 24 h after induction. The β-galactosidase assays were carried out in MultiScreen 96-well microtiter plates fitted onto a MultiScreen filtration system (Millipore) using a previously described procedure (16) which is similar to the procedure described by Miller (31). The assays were repeated with four biological replicates and eight technical replicates.

Biofilm formation assays.

Biofilm formation assays in 96-well microtiter plates (polyvinyl chloride) were carried out with 100-μl portions of overnight cultures diluted to an OD600 of 0.2. The microtiter plates were incubated at 30°C for 8 h. Crystal violet staining and ethanol solubilization were carried out as previously described (16, 41). The assays were repeated with two different biological replicates and eight technical replicates.

Protease assays.

V. cholerae cells harboring a vpsS overexpression plasmid were cultured by first growing cells in the absence of arabinose overnight and then diluting them 1:200 in fresh LB media with and without the inducer 0.2% arabinose. Protease assays were performed 24 h after induction. Protease activity was assayed using an EnzChek protease assay kit (Invitrogen) by following the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, culture supernatants were collected by centrifugation and diluted 1:100 in LB media. Each diluted supernatant was then further diluted 1:10 in 1× digestion buffer, and 100-μl aliquots were mixed with 100 μl of a BODIPY FL casein solution. The reaction mixtures were incubated for 1 h at 30°C, and fluorescence was measured with a Victor3 microplate reader (PerkinElmer) and normalized to cell density. The assays were performed with three technical replicates per strain and repeated with three biological replicates.

In vitro analysis of phosphotransfer relationships.

Full-length coding regions for VpsS, VpsR, LuxU, and LuxO were cloned into the Invitrogen Gateway ENTRY vector pENTR/D-TOPO according to the manufacturer's instructions. We also cloned the coding regions of the HKs and receiver domains (RDs) of VpsS (VpsS-HK and VpsS-RD), LuxQ (LuxQ-HK and LuxQ-RD), and CqsS (CqsS-HK and CqsS-RD) separately, as well as the RDs of LuxO (LuxO-RD), VpsR (VpsR-RD), ChiS (ChiS-RD), VC0303 (VC0303-RD), VC1831 (VC1831-RD), VieS (VieS-RD), VC2369 (VC2369-RD), and VarS (VarS-RD). The sequences of all constructs were verified, and the constructs were then mobilized into expression vectors using the Gateway system. RD proteins were purified using an N-terminal thioredoxin-His6 tag, while HK and HPT proteins were purified using an N-terminal His6-maltose binding protein tag. Proteins were purified as described previously (36). Phosphotransfer reactions were carried out as described previously (6). Briefly, LuxQ-HK (2 μM), LuxQ-RD (2 μM), and LuxU (20 μM) were incubated together in HKEDG buffer supplemented with 5 mM MgCl2 in the presence of 0.5 μCi [γ-32P]ATP and 0.5 mM ATP for 30 min at 30°C in a 10-μl reaction mixture. This reaction mixture was then diluted 1:10 in HKEDG buffer supplemented with 5 mM MgCl2. Aliquots (5 μl) of the reaction mixture were then added to 5 μl of each individual RD in HKEDG buffer supplemented with 5 mM MgCl2 to obtain a final RD concentration of 10 μM in HKEDG buffer. The reaction mixtures were then incubated at room temperature for 1 or 5 min, and then the reactions were stopped and the mixtures were analyzed by using sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and phosphorimaging.

RESULTS

Identification of a sensor HK positively regulating vps gene expression.

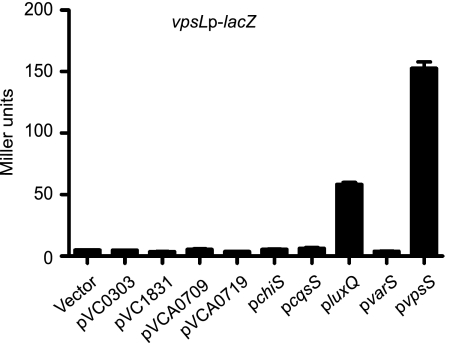

In many two-component signal transduction systems, genes encoding cognate HKs and RRs are arranged in operons. However, vpsR (VC0665), encoding the most downstream RR for vps gene regulation, does not occur in an operon with an HK gene, and no cognate HK has been identified. We therefore hypothesized that an orphan HK (an HK protein whose gene is not found in an operon with or next to a gene encoding an RR domain-containing protein) would be a likely phosphodonor for VpsR. We searched Pfam and InterPro databases and found 42 genes encoding proteins with an HK domain in the V. cholerae genome. Nine of the proteins are predicted to be orphan HKs. We therefore screened each orphan HK for the ability to induce vps expression upon overexpression. To this end, each HK gene was cloned into an inducible pBAD expression vector, and the plasmids were introduced individually into a reporter strain harboring a vpsLp-lacZ transcriptional fusion at the lacZ locus on the V. cholerae chromosome. Each HK was then assessed to determine its ability to upregulate vpsL expression by determining the β-galactosidase activity in cells that were grown for 24 h in the presence and absence of the inducer arabinose. This initial screen revealed that overexpression of luxQ (VCA0736) and VC1445 resulted in increased vpsL expression (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Overexpression of vpsS and luxQ activates vps expression. Expression of vpsL in a vpsLp-lacZ reporter strain harboring either the vector pBAD or pVC0303, pVC1831, pVCA0709, pVCA0719, pchiS, pcqsS, pluxQ, pvarS, or pvpsS was examined. Overnight cultures were diluted 1:500 and grown for 24 h in LB medium supplemented with ampicillin and 0.2% arabinose to induce HK overexpression. The error bars indicate standard deviations of eight technical replicates. The results of one representative experiment of four biological replicates are shown.

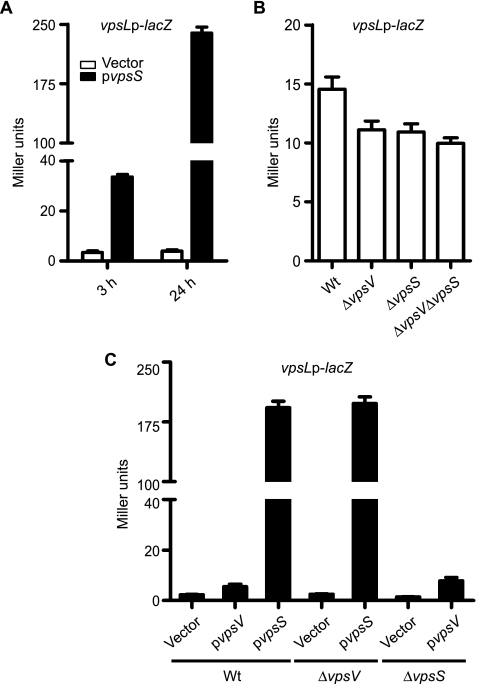

We then focused on VC1445 as it has not been studied previously. To further confirm these results, we performed β-galactosidase assays with the vpsLp-lacZ strain harboring the VC1445 (designated vpsS for vibrio polysaccharide biosynthesis sensor) overexpression plasmid or the vector in the presence or absence of the inducer arabinose. Overexpression of vpsS resulted in an increase in vpsL expression after 3 and 24 h of induction (Fig. 2A). As expected, strains carrying the vector did not exhibit elevated vpsL expression in the presence of arabinose. Strains carrying either the vector or pvpsS grown in the absence of arabinose did not show elevated vpsL expression (data not shown). Because vpsL expression was greater after 24 h of induction and the production of Myc-tagged VpsS was also found to be greater after 24 h of induction when it was analyzed by Western analysis (data not shown), we chose this time point for subsequent overexpression studies.

FIG. 2.

VpsS activates vps expression. (A) Expression of vpsL in a vpsLp-lacZ reporter strain harboring either the vector pBAD (open bars) or pvpsS (filled bars). Overnight cultures were diluted 1:500 and grown for 3 or 24 h in LB medium supplemented with ampicillin and 0.2% arabinose. (B) Expression of vpsL in wild-type (Wt), ΔvpsV, ΔvpsS, and ΔvpsV ΔvpsS strains harboring a single copy of the vpsLp-lacZ reporter grown to exponential phase in LB medium. (C) Expression of vpsL in wild-type, ΔvpsV, and ΔvpsS strains carrying a vpsLp-lacZ reporter fusion harboring either the vector pBAD, pvpsV, or pvpsS. The error bars indicate standard deviations of eight technical replicates. The results of one representative experiment of four biological replicates are shown.

To better evaluate the involvement of VpsS in the regulation of vps gene expression, we generated an in-frame vpsS deletion mutant in the vpsLp-lacZ reporter strain and analyzed vps gene expression in cells grown to exponential phase using β-galactosidase assays. We determined that vpsL expression was slightly decreased in the ΔvpsS mutant compared to the wild type (Fig. 2B). Expression of vps genes is negatively regulated by the quorum-sensing signal transduction system in stationary phase, and as expected, we did not see a significant difference in vps gene expression between the wild type and the vpsS mutant when expression was analyzed in cells grown to stationary phase (data not shown). Taken together, these results indicate that VpsS positively regulates vps expression.

vpsS is the second gene in a predicted two-gene operon with VC1444. Transcriptional linkage analysis by reverse transcription-PCR revealed that VC1444 (designated vpsV) and vpsS are in an operon (data not shown). We therefore hypothesized that vpsV might be necessary for VpsS function. To test this possibility, we generated vpsV and vpsV vpsS in-frame deletion mutants in the vpsLp-lacZ reporter strain and analyzed vpsL gene expression. In exponential phase, the level of expression of vpsL was lower in the ΔvpsV and ΔvpsV ΔvpsS strains than in the wild type, similar to the data for the ΔvpsS strain (Fig. 2B). This finding suggests that vpsV and vpsS affect vpsL expression similarly. To determine whether vpsS required vpsV to upregulate vpsL, we overexpressed vpsS in the ΔvpsV background. The expression of vpsL in the ΔvpsV strain was similar to that in the wild-type strain when vpsS was overexpressed (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, overexpression of vpsV did not induce vpsL expression in the wild type and in the ΔvpsS strain. As expected, strains carrying the vector or the overexpression plasmids did not activate vpsL expression in the absence of arabinose (data not shown). This finding suggests that, when overexpressed, VpsS can function without VpsV.

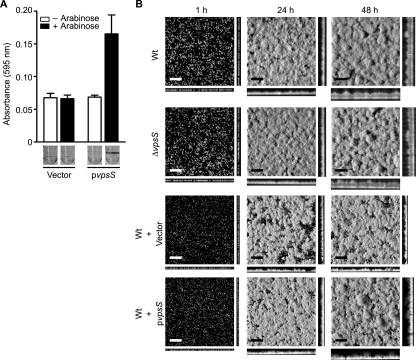

VpsS modulates biofilm formation.

Since both deletion and overexpression of vpsS altered vpsL transcription, we reasoned that VpsS might also modulate biofilm formation in V. cholerae. To examine this possibility, we initially compared the biofilm-forming ability of the ΔvpsS mutant to that of the wild type using a crystal violet staining assay. We determined that the biofilm phenotypes of the ΔvpsS and wild-type strains were similar (data not shown). However, using the same assay, we determined that overexpression of vpsS in the wild-type strain carrying pvpsS markedly increased the biofilm formation compared to that of the same strain containing the vector (Fig. 3A). In the absence of arabinose, strains carrying the vector or pvpsS exhibited similar biofilm-forming capacities.

FIG. 3.

Overexpression of vpsS activates biofilm formation. (A) Quantitative comparison of biofilm formation by wild-type strains harboring the vector or pvpsS. Strains were grown for 8 h in LB medium supplemented with ampicillin in the absence (open bars) or presence (filled bars) of arabinose at 30°C under static conditions. Crystal violet-stained biofilms formed in the wells of polyvinyl chloride microtiter plates are also shown. The error bars indicate standard deviations of eight technical replicates. The results of one representative experiment of two biological replicates are shown. (B) CSLM images of horizontal (xy) and vertical (xz) projections of biofilm structures formed by the wild-type strain (Wt), the ΔvpsS mutant, and wild-type strains carrying the vector or pvpsS. Strains were grown for the times indicated in 2% LB medium in the presence or absence of ampicillin and 0.2% arabinose at room temperature. Bars = 40 μm.

We further evaluated the contribution of VpsS to biofilm formation by analyzing biofilm phenotypes. The biofilm formation by the ΔvpsS strain was similar to that by the wild-type strain over a period of 48 h (Fig. 3B). However, overexpression of vpsS in the wild-type strain carrying pvpsS markedly increased biofilm formation compared to the biofilm formation by the same strain containing the vector. Quantitative analysis of biofilm images with COMSTAT revealed that the total biomass and average and maximum thicknesses of the biofilm formed by the wild-type strain overexpressing vpsS differed from the total biomass and average and maximum thicknesses of the biofilm formed by the wild-type strain harboring the control vector after 48 h (Table 2). No significant differences in the total biomass and average and maximum thicknesses were observed between the wild-type and ΔvpsS strains (Table 2). It should be noted that the growth rates of these strains are identical (data not shown). These results indicate that overexpression, but not deletion, of vpsS modulates biofilm formation. The absence of a clear biofilm phenotype in strains lacking vpsS may indicate that there is functional redundancy in the VpsS regulatory network, that the level of vpsS expression may not be high enough under the experimental conditions used in this study, or that the decreased vps expression in a ΔvpsS mutant is not significant enough to alter biofilm formation.

TABLE 2.

COMSTAT analysis of biofilms of wild-type and ΔvpsS strains and wild-type strains harboring a vector or vpsS overexpression plasmida

| Strain | Time (h) | Total biomass (μm3/μm2) | Thickness (μm)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avg | Maximum | |||

| Wild type | 1 | 11.8 (1.37) | 10.9 (1.37) | 11.0 (1.45) |

| 24 | 23.4 (2.43) | 22.5 (2.43) | 22.5 (2.46) | |

| 48 | 37.4 (4.08) | 36.5 (4.08) | 36.7 (3.93) | |

| ΔvpsS | 1 | 11.2 (1.46) | 10.3 (1.46) | 10.4 (1.61) |

| 24 | 23.5 (3.93) | 22.6 (3.93) | 22.7 (3.91) | |

| 48 | 39.8 (4.39) | 38.9 (4.39) | 39.1 (4.25) | |

| Wild type/vectorb | 1 | 2.0 (0.44) | 3.2 (0.88) | 10.1 (1.87) |

| 24 | 21.1 (2.23) | 23.6 (2.76) | 25.2 (3.12) | |

| 48 | 25.8 (5.10) | 29.4 (5.19) | 30.9 (5.19) | |

| Wild type/pvpsSb | 1 | 3.0 (0.37) | 5.2 (0.83) | 12.8 (2.07) |

| 24 | 23.6 (2.45) | 24.6 (3.40) | 25.3 (3.60) | |

| 48 | 32.0 (2.17) | 37.4 (4.72) | 42.0 (8.06) | |

The values are the means (standard deviations) of data from at least six z-series image stacks.

Cultures were grown in the presence of ampicillin and 0.2% arabinose.

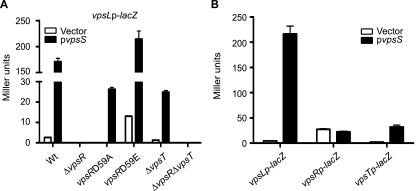

VpsS requires VpsR, but not VpsT, to activate vps expression.

VpsR is an RR and requires phosphorylation to activate vps gene expression and biofilm formation (25; J. Meir and F. H. Yildiz, unpublished data). We reasoned that VpsS could positively regulate vps expression through phosphorylation of VpsR. We therefore evaluated whether VpsS induces vps expression in a VpsR-dependent manner. To this end, we overexpressed vpsS in the vpsLp-lacZ reporter strain harboring an in-frame deletion of vpsR or in mutants in which the chromosomal copy of vpsR was mutated such that aspartate 59 was replaced with alanine [vpsR(D59A), constitutively inactive] or with glutamate [vpsR(D59E), constitutively active] and evaluated vpsL expression using β-galactosidase assays. No significant increase in vpsL expression was observed in the ΔvpsR strain overexpressing vpsS or harboring the vector alone (Fig. 4A), indicating that VpsR is required for VpsS to upregulate vpsL expression. Overexpression of vpsS in a strain harboring a “constitutively inactive” version of VpsR [vpsR(D59A)] resulted in increased vpsLp-lacZ activity compared to the same strain harboring the control vector. The strain harboring a “constitutively active” version of VpsR [vpsR(D59E)] and carrying the control vector exhibited a high level of vpsL expression compared to the wild-type strain carrying the control vector, supporting the idea that VpsR modification modulates its activity. Moreover, a marked increase in vpsL expression was observed in the vpsR(D59E) strain when vpsS was overexpressed compared to the same strain harboring the control vector. Taken together, these results suggest that VpsS has functions other than phosphorylating the canonical aspartate (D59) of VpsR. It is also likely that VpsS can indirectly activate VpsR through another two-component system or control its expression.

FIG. 4.

VpsS requires VpsR to activate vps expression. (A) Expression of vpsL in wild-type (Wt), ΔvpsR, vpsR(D59A), vpsR(D59E), ΔvpsT, and ΔvpsR ΔvpsT strains harboring a vpsLp-lacZ reporter carrying the vector (open bars) or pvpsS (filled bars). (B) Expression of vpsL, vpsR, and vpsT from a single-copy chromosomal vpsLp-lacZ, vpsRp-lacZ, or vpsTp-lacZ reporter in the wild-type strain harboring the vector (open bars) or pvpsS (filled bars). vpsS was overexpressed in LB medium supplemented with ampicillin and 0.2% arabinose. The error bars indicate standard deviations of eight technical replicates. The results of one representative experiment of four biological replicates are shown.

Since VpsS does not appear to directly phosphorylate VpsR, we hypothesized that overexpression of VpsS might instead modulate the expression of vpsR. When vpsS was overexpressed in a strain carrying a chromosomal vpsRp-lacZ reporter fusion, the expression was similar to that of a strain carrying the vector alone (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that VpsS does not regulate the expression of vpsR but nonetheless requires VpsR to regulate vpsL expression.

VpsT is another known positive regulator of vps genes. We therefore asked whether the effect of VpsS, in addition to the effect of VpsR, was mediated through VpsT. To examine this possibility, we overexpressed vpsS in the vpsLp-lacZ reporter strain harboring ΔvpsT or ΔvpsR ΔvpsT mutations. As expected, the ΔvpsT strain carrying the control vector had reduced vpsL expression compared to the wild type carrying the control vector (Fig. 4A). However, when vpsS was overexpressed in the ΔvpsT strain, vpsL expression was induced. Furthermore, the ΔvpsR ΔvpsT double mutant showed no change in vpsL expression when vpsS was overexpressed compared to the same strain carrying the control vector. We then hypothesized that VpsS might modulate vpsL expression through the expression of vpsT. Indeed, when VpsS was overexpressed in a chromosomal vpsTp-lacZ strain, the vpsT expression increased compared that in a strain harboring the vector alone (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that VpsS regulates vpsT expression and that VpsT contributes to, but is not essential for, the VpsS-dependent activation of vps genes.

VpsS requires LuxU to activate vps genes.

VpsS is a hybrid kinase that has both HK and RR domains, but it lacks the HPT domain that normally mediates movement of phosphoryl groups from a hybrid HK to a downstream RR. We thus speculated that VpsS does not phosphorylate its cognate RR directly but instead acts via a separate HPT. We therefore searched the genome to identify genes encoding potential cytoplasmic HPT proteins by looking for proteins with characteristics of other HPTs based on the following criteria: (i) smaller than 250 amino acids, (ii) >70% predicted alpha helical secondary structure, and (iii) the presence of a conserved HXXKG motif within the predicted alpha helices (6). This analysis identified LuxU and VC1080 as possible candidates. We also searched the V. cholerae genome for genes predicted to encode HPT domains (PF01627) and identified another HPT, VC2038, that is predicted to localize to the cytoplasmic membrane.

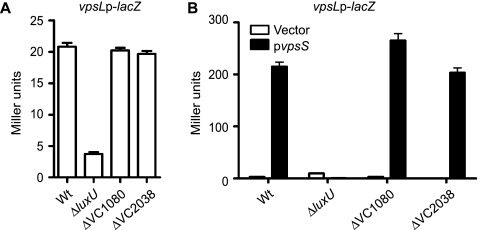

To determine whether these HPT proteins were involved in the phosphorelay inducing vps expression, we generated in-frame deletions of genes encoding each HPT in the vpsLp-lacZ reporter strain. A previous study reported that LuxU positively regulates biofilm formation (17). Indeed, a luxU mutant showed decreased vpsL expression compared to the wild type when the organisms were grown to exponential phase (Fig. 5A). Mutants with in-frame deletions of VC1080 and VC2038, however, did not exhibit differences in vpsL expression compared to the wild type, suggesting that VC1080 and VC2038 are not involved in the regulation of vpsL expression. We then overexpressed vpsS and analyzed vpsL expression in each HPT mutant strain. As expected, strains lacking luxU showed no VpsS-dependent activation of vpsLp-lacZ when vpsS was overexpressed, while the vpsL expression was similar to that of the wild type in VC1080 and VC2038 deletion mutants (Fig. 5B). Strains carrying only the vector did not exhibit activation of vpsL in the presence of arabinose. These results indicate that the VpsS phosphorelay system functions through the HPT LuxU.

FIG. 5.

VpsS requires the HPT LuxU to activate vps expression. (A) Expression of vpsL from a vpsLp-lacZ reporter in wild-type (Wt), ΔluxU, ΔVC1080, and ΔVC2038 strains grown to exponential phase in LB medium. (B) Expression of vpsL from a vpsLp-lacZ reporter in wild-type, ΔluxU, ΔVC1080, and ΔVC2038 strains harboring the vector (open bars) or pvpsS (filled bars). vpsS was overexpressed in LB medium supplemented with ampicillin and 0.2% arabinose. The error bars indicate standard deviations of eight technical replicates. The results of one representative experiment of four biological replicates are shown.

VpsS contributes to the quorum-sensing phosphotransfer cascade.

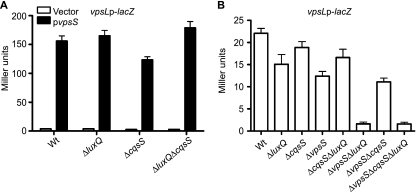

The quorum-sensing hybrid HKs CqsS and LuxQ were previously shown to require LuxU to control quorum-sensing-regulated gene expression (32). We therefore asked whether LuxQ or CqsS contributes to vps upregulation through VpsS. To answer this question, we generated ΔcqsS, ΔluxQ, and ΔcqsS ΔluxQ deletion mutants of the vpsLp-lacZ reporter strain, overexpressed vpsS in these strains, and quantified vpsL expression. Overexpression of vpsS in any of these deletion strains resulted in upregulation of vpsL similar to that in the wild-type strain (Fig. 6A), suggesting that CqsS and LuxQ are not required for VpsS to activate vpsL expression.

FIG. 6.

LuxQ, CqsS, and VpsS regulate vps expression in parallel. (A) Expression of vpsL from a vpsLp-lacZ reporter in wild-type (Wt), ΔluxQ, ΔcqsS, and ΔluxQ ΔcqsS strains harboring the vector (open bars) or pvpsS (filled bars). vpsS was overexpressed in LB medium supplemented with ampicillin and 0.2% arabinose. The error bars indicate standard deviations of eight technical replicates. The results of one representative experiment with four biological replicates are shown. (B) Expression of vpsL from a vpsLp-lacZ reporter in wild-type, ΔluxQ, ΔcqsS, ΔvpsS, ΔcqsS ΔluxQ, ΔvpsS ΔluxQ, ΔvpsS ΔcqsS, and ΔvpsS ΔcqsS ΔluxQ strains grown to exponential phase in LB medium. The error bars indicate standard deviations of eight technical replicates. The results of one representative experiment of four biological replicates are shown.

We further evaluated the contribution of cqsS, luxQ, and vpsS to vps gene expression using epistasis analysis. To this end, we constructed individual ΔluxQ, ΔcqsS, and ΔvpsS deletion mutants and combination ΔcqsS ΔluxQ, ΔvpsS ΔluxQ, ΔvpsS ΔcqsS, and ΔvpsS ΔcqsS ΔluxQ deletion mutants of the vpsLp-lacZ reporter strain and measured vpsL expression in cells grown to exponential phase. Deletion of luxQ, cqsS, or vpsS individually moderately decreased vpsL expression (Fig. 6B). The ΔcqsS ΔluxQ and ΔvpsS ΔcqsS double mutations additively decreased vpsL expression, and the ΔvpsS ΔluxQ double-deletion mutant exhibited the most drastic decrease in vpsL expression, similar to the ΔvpsS ΔcqsS ΔluxQ triple-deletion mutant. These results indicate that CqsS, LuxQ, and VpsS act in parallel through LuxU to regulate vpsL expression.

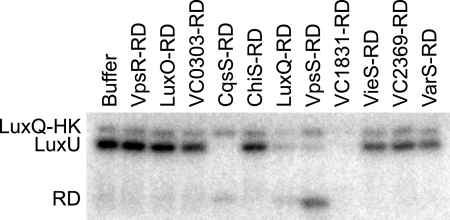

LuxU participates in phosphotransfer with VpsS.

To further analyze the relationships between VpsS and LuxU, we evaluated the in vitro phosphotransfer relationship between LuxU, VpsS, CqsS, and LuxQ. To this end, we separately purified LuxU and the HK domains and RDs from VpsS, CqsS, and LuxQ. Only the kinase domain of LuxQ (LuxQ-HK) exhibited significant autophosphorylation in vitro. Incubation of LuxQ-HK, LuxQ-RD, and LuxU led to accumulation of phosphorylated LuxU, as expected if LuxQ can transfer phosphoryl groups to LuxU. As we could not test whether VpsS phosphotransfers to LuxU, we then tested whether LuxU∼P could serve as a phosphodonor to the RDs of VpsS, CqsS, and LuxQ. To assess the specificity of an in vitro LuxU∼P phosphotransfer, we also performed the assay with the RDs of six other hybrid histidine kinases, VC0303, ChiS, VC1831, VieS, VC2369, and VarS. Incubation of LuxU∼P with the RDs of VpsS, CqsS, and LuxQ led to depletion of radiolabel from LuxU, indicating that there was phosphotransfer (Fig. 7). A band corresponding to the phosphorylated RD was seen in each case, although this band was faint for LuxQ-RD and CqsS-RD. For these two RDs, the residual LuxQ-HK in the reactions (used to produce LuxU∼P) may drive their dephosphorylation, or they may be intrinsically less stable. For the other six RDs, there was no evidence of phosphotransfer, except for VC1831. It has not been determined whether VC1831 is part of the quorum-sensing pathway in V. cholerae or whether LuxU exhibits some promiscuity in vitro. We also tested for phosphotransfer from LuxU∼P to the RDs of LuxO and VpsR but did not observe any significant transfer. LuxO, a predicted substrate for LuxU∼P in vivo, may require additional factors for phosphotransfer in vitro. Whether VpsR is a substrate for LuxU∼P is unclear. Our data do, however, support a model in which VpsS can drive the phosphorylation of LuxU, as it does with LuxQ and CqsS.

FIG. 7.

LuxU phosphotransfers to the RDs of VpsS, CqsS and LuxQ. In vitro phosphotransfer analyses showed transfer of phosphoryl groups from LuxU∼P to the RDs of VpsS, CqsS, LuxQ, and VC1831. Each phosphotransfer reaction mixture containing LuxQ-HK, LuxQ-RD, and LuxU was incubated with radiolabeled ATP before dilution and addition of the RDs indicated for 1 or 5 min at room temperature. Incubation for 1 min and incubation for 5 min produced similar results; only data for 1 min of incubation are shown. Buffer was used as a negative control.

VpsS requires LuxO for induction of vps expression.

LuxU relays a phosphate signal from the hybrid HKs CqsS and LuxQ to the RR LuxO, leading to the regulation of HapR (32). Since VpsS requires LuxU to activate vps expression, we hypothesized that VpsS could positively regulate vps expression through the known quorum-sensing pathway involving LuxU, LuxO, and HapR.

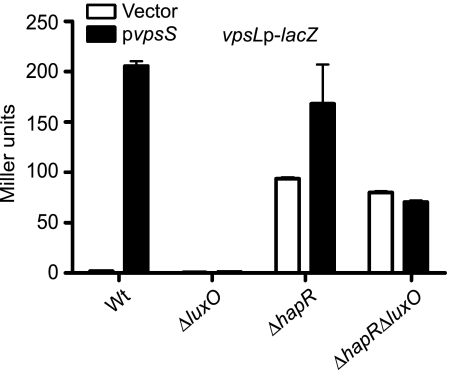

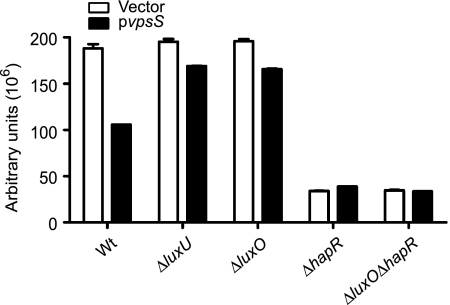

To determine whether VpsS requires LuxO and/or HapR for its effect on vpsL expression, we generated ΔluxO, ΔhapR, and ΔluxO ΔhapR deletion mutants of the vpsLp-lacZ reporter strain, overexpressed vpsS, and analyzed vpsL expression. Overexpression of vpsS in the ΔluxO strain did not result in enhanced vpsL expression compared to the wild-type expression (Fig. 8). As expected from deletion of a negative regulator, the ΔhapR mutant harboring the vector alone exhibited increased expression of vpsL compared to the wild type harboring the vector. However, when vpsS was overexpressed in the ΔhapR background, a further increase in vpsL expression was observed compared to the same strain harboring the vector. This additional activation of vpsL expression, due to overexpression of vpsS, was abolished in the ΔluxO ΔhapR mutant. Therefore, VpsS requires LuxO, but not HapR, to upregulate vpsL expression. Furthermore, the vpsL expression phenotypes of the ΔluxO and ΔluxO ΔhapR mutants could be complemented by inserting a single copy of luxO into the chromosome (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Together, these results indicate that VpsS activates vpsL expression through LuxO, and this activation is not dependent on HapR.

FIG. 8.

VpsS requires LuxO, but not HapR, to activate vps. Expression of vpsL from a vpsLp-lacZ reporter in wild-type (Wt), ΔluxO, ΔhapR, and ΔluxO ΔhapR strains harboring the vector (open bars) or pvpsS (filled bars) was examined. vpsS was overexpressed in LB medium supplemented with ampicillin and 0.2% arabinose. The error bars indicate standard deviations of eight technical replicates. The results of one representative experiment of four biological replicates are shown.

Our results described above suggest that LuxO regulates the expression of vpsL independent of HapR. To our knowledge, the only other gene shown to be regulated by LuxO independent of HapR is VCA0939 (18). VCA0939 is predicted to encode a protein containing a GGDEF domain. Proteins with GGDEF domains are known to act as diguanylate cyclases, which produce cyclic diguanylate (c-di-GMP), a secondary messenger that affects virulence, motility, VPS production, and biofilm formation in V. cholerae (11). The stability of VCA0939 mRNA was shown to be mediated by the Qrr sRNAs, which are positively regulated by LuxO (18). We thus tested whether VpsS was dependent on VCA0939 to regulate vpsL. We found that deleting VCA0939 did not alter vpsL expression when vpsS was overexpressed (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), suggesting that VpsS does not require VCA0939 for upregulation of vpsL expression and that LuxO activates vpsL independent of VCA0939.

LuxO positively regulates vpsR and vpsT expression.

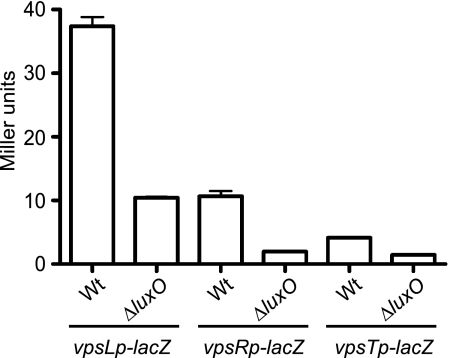

As described above, the V. cholerae quorum-sensing system acts through LuxO to modulate vps expression (17, 38). Additionally, the master quorum-sensing regulator, HapR, was shown to negatively regulate the expression of the two positive vps regulators, VpsR and VpsT (3). We therefore asked whether LuxO modulates the expression of vpsR and vpsT. To examine this possibility, luxO was deleted in reporter strains carrying chromosomal vpsL, vpsR, or vpsT promoter-lacZ fusions (vpsLp-lacZ, vpsRp-lacZ, and vpsTp-lacZ, respectively). When these strains were grown to mid-exponential phase and assayed for β-galactosidase activity, the expression of vpsL, vpsR, and vpsT was lower in the ΔluxO mutant than in the wild type (Fig. 9). These results link the quorum-sensing phosphotransfer cascade of LuxO to the positive regulation of both vpsR and vpsT.

FIG. 9.

LuxO positively regulates vpsL, vpsR, and vpsT expression. Expression of vpsL, vpsR, and vpsT in wild-type (Wt) and ΔluxO strains harboring single-copy chromosomal vpsLp-lacZ, vpsRp-lacZ, and vpsTp-lacZ reporters and grown to exponential phase in LB medium was examined. The error bars indicate standard deviations of eight technical replicates. The results of one representative experiment of four biological replicates are shown.

We also entertained the notion that LuxO could directly regulate the expression of vpsR and vpsT and thus lead to HapR-independent regulation of vpsL expression. Since LuxO activation is σ54 dependent, we searched for possible σ54 binding sites (5′-TGGCAN-N5-TTGCA/T-3′) (27) upstream of vpsR and vpsT. However, no σ54 binding sites were identified, suggesting that LuxO regulates vpsR and vpsT indirectly.

VpsS regulates protease activity.

Our results indicate that VpsS regulates biofilm formation through the known quorum-sensing pathway involving LuxU, LuxO, and HapR. We therefore hypothesized that other quorum-sensing-dependent phenotypes would be modulated in response to vpsS overexpression. Since protease production is positively regulated by quorum sensing in V. cholerae (23, 43), we hypothesized that overexpression of vpsS would repress the production of extracellular proteases. Indeed, when vpsS was overexpressed in the wild-type strain, the protease activity decreased compared to that in cells containing the vector alone (Fig. 10). Furthermore, overexpression of vpsS in ΔluxU and ΔluxO strains did not result in a significant decrease in protease activity compared to the activity in the same strains carrying the vector alone. These results are congruent with the notion that VpsS contributes to the phosphotransfer cascade involving LuxU and LuxO to modulate hapR expression and protease activity. Consistent with the idea that HapR is a positive regulator of protease production, ΔhapR and ΔhapR ΔluxO strains carrying only the vector exhibited substantially lower protease activities than the wild type carrying the vector. Furthermore, overexpression of VpsS in ΔhapR and ΔhapR ΔluxO mutants appeared not to affect protease activity. Taken together, these results suggest that overexpression of VpsS modulates protease activity in V. cholerae.

FIG. 10.

VpsS negatively regulates protease activity. Protease activity in wild-type (Wt), ΔluxU, ΔluxO, ΔhapR, and ΔluxO ΔhapR strains harboring the vector (open bars) or pvpsS (filled bars) was examined. Strains were grown in LB medium supplemented with ampicillin and 0.2% arabinose to induce vpsS expression. The results are expressed in arbitrary units of fluorescence measured at 530 nm normalized to cell density (OD600). The error bars indicate standard deviations of three technical replicates. The results of one representative experiment of four biological replicates are shown.

DISCUSSION

V. cholerae is an inhabitant of two very different environments, the aquatic milieu and the human digestive tract. Recent studies revealed that V. cholerae's ability to form biofilms facilitates its environmental survival, transmission, and interaction with its human host (1, 14, 15). In this study, we identified a hybrid HK, VpsS, which positively regulates biofilm formation in V. cholerae. VpsS homologs exist in other closely related Vibrio species. These homologs include VF_1296 of Vibrio fischeri (47% identity, 70% positives, 5 gaps), VP1547 of Vibrio parahaemolyticus (50% identity, 69% positives, 4 gaps), and VV1_2622 of Vibrio vulnificus (51% identity, 72% positives, 15 gaps) (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material), but to date, none of these homologs have been characterized. It is intriguing that the upstream genomic contexts of vpsS and its homologs in other Vibrio species are similar (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). It has not been determined yet if VpsS homologs are involved in quorum-sensing signal transduction in other Vibrio species.

VpsS is a hybrid kinase that contains both HK and RR domains but not an HPT domain. The transfer of phosphoryl groups between such a hybrid HK and a downstream RR would normally be mediated by an HPT protein. We thus speculated that VpsS does not phosphorylate its cognate RR directly but acts via a separate HPT. We determined that the HPT LuxU is required for VpsS to upregulate vps expression. Subsequent analysis revealed that LuxU can reverse phosphotranfer to VpsS. In vitro reverse phosphotransfer was shown to occur previously in other systems (13), and we showed that LuxU specifically transfers phosphate to the RDs of other known hybrid HK partners, LuxQ and CqsS, but not to the control RDs of five other hybrid HKs. Interestingly LuxU can also transfers phosphate to the RD of VC1831, and the importance of this hybrid HK in quorum-sensing-regulated processes is currently under investigation. Taken together, our results indicate that VpsS positively regulates biofilm formation through a phosphotransfer signaling cascade previously identified to be involved in quorum sensing.

In this study, we report that VpsS is dependent on only some components of the V. cholerae quorum-sensing system to activate vps expression. VpsS was not dependent on the quorum-sensing master regulator HapR to activate vps genes. We show that VpsS can affect protease activity, a HapR-regulated process, and that the ability of VpsS to upregulate vps expression did, however, require the HPT LuxU and the RR LuxO. We further showed that LuxO positively regulates vpsR and vpsT expression. Both LuxU and LuxO are required for the phosphorelay that responds to the abundance of the V. cholerae AIs CAI-1 and AI-2 (17, 32). CAI-1 [(S)-3-hydroxytridecan-4-one] is synthesized by CqsA and is detected by CqsS (22), while AI-2 [the furanosyl borate diester (2S,4S)-2-methyl-2,3,3,4-tetrahydroxytetrahydrofuran borate] is synthesized by LuxS and is detected by the LuxQP receptor (9, 34). The nature of the signal that initiates autophosphorylation of VpsS has not been determined yet. VpsS is not predicted to contain any transmembrane domains and might therefore receive an intracellular signal, in contrast to its extracellular autoinducer-sensing counterparts, CqsS and LuxQ. Cytoplasmic HKs in other bacteria are known to sense a variety of intracellular signals, such as those involved in cellular metabolism, or environmental signals detectable in the cytoplasm (29). It is well documented that the transcription of genes involved in biofilm formation is enhanced by the cytoplasmic signaling molecule c-di-GMP via an as-yet-unknown mechanism. We hypothesized that VpsS senses c-di-GMP and its activity may be regulated by c-di-GMP. However, purified VpsS did not bind to c-di-GMP (unpublished data), suggesting that VpsS is not a c-di-GMP sensor protein. vpsV precedes vpsS in a predicted two-gene operon, and our results showed that deletion of either vpsS or vpsV leads to a decrease in vps expression. VpsV is annotated as a hypothetical protein and does not contain any putative transmembrane domains. VpsV does, however, contain a FIST (F-box and intracellular signal transduction, PF08495) domain, and such domains are often associated with other well-known signal transduction domains (7). It is therefore possible that VpsV and VpsS are both required to initiate the phosphotransfer cascade in response to a stimulus. The role of VpsV in VpsS-dependent activation of vpsL expression is currently under investigation.

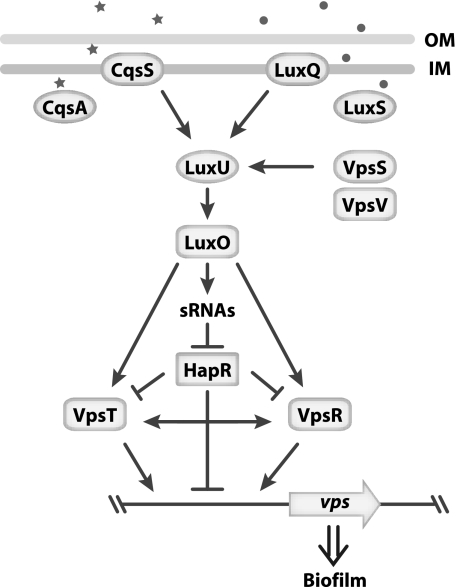

Our current understanding of the regulatory network controlling vps gene expression is summarized in Fig. 11. At low cell density, phosphotransfer is initiated by the hybrid HKs CqsS, LuxQ, and VpsS to the HPT LuxU, which then transfers the phosphoryl group to the quorum-sensing RR LuxO. Phosphorylated LuxO then negatively regulates HapR via the Qrr sRNAs and positively regulates VpsR and VpsT through a yet-to-determined mechanism. HapR negatively regulates the transcription of vpsR, vpsT, and the vps genes, while VpsR and VpsT positively regulate the transcription of vps genes.

FIG. 11.

Model of the VpsS phosphotransfer cascade. VpsS activates vps expression through LuxU and LuxO. LuxO can regulate vps expression through HapR, as well as independent of HapR through VpsR and/or VpsT. Stars and dots represent CAI-1 and AI-2, respectively. Details of the model are discussed in the text.

V. cholerae's ability to cause epidemics is tied to its ability to survive in aquatic habitats in biofilms. A better understanding of the signals and molecular mechanisms involved in biofilm formation is therefore critical for understanding the environmental survival and transmission of V. cholerae.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from NIH R56AI55987-6 and NIH R01 (AI055987) to F.H.Y.

We thank James Meir and Vanessa Soliven for constructing pFY-214 and pFY-215. We also thank Karen Ottemann, Manel Camps, and members of the Yildiz laboratory for their valuable comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 12 June 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alam, M., M. Sultana, G. B. Nair, A. K. Siddique, N. A. Hasan, R. B. Sack, D. A. Sack, K. U. Ahmed, A. Sadique, H. Watanabe, C. J. Grim, A. Huq, and R. R. Colwell. 2007. Viable but nonculturable Vibrio cholerae O1 in biofilms in the aquatic environment and their role in cholera transmission. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104:17801-17806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bao, Y., D. P. Lies, H. Fu, and G. P. Roberts. 1991. An improved Tn7-based system for the single-copy insertion of cloned genes into chromosomes of gram-negative bacteria. Gene 109:167-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beyhan, S., K. Bilecen, S. R. Salama, C. Casper-Lindley, and F. H. Yildiz. 2007. Regulation of rugosity and biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae: comparison of VpsT and VpsR regulons and epistasis analysis of vpsT, vpsR, and hapR. J. Bacteriol. 189:388-402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beyhan, S., A. D. Tischler, A. Camilli, and F. H. Yildiz. 2006. Transcriptome and phenotypic responses of Vibrio cholerae to increased cyclic di-GMP level. J. Bacteriol. 188:3600-3613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beyhan, S., and F. H. Yildiz. 2007. Smooth to rugose phase variation in Vibrio cholerae can be mediated by a single nucleotide change that targets c-di-GMP signalling pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 63:995-1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biondi, E. G., J. M. Skerker, M. Arif, M. S. Prasol, B. S. Perchuk, and M. T. Laub. 2006. A phosphorelay system controls stalk biogenesis during cell cycle progression in Caulobacter crescentus. Mol. Microbiol. 59:386-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borziak, K., and I. B. Zhulin. 2007. FIST: a sensory domain for diverse signal transduction pathways in prokaryotes and ubiquitin signaling in eukaryotes. Bioinformatics 23:2518-2521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casper-Lindley, C., and F. H. Yildiz. 2004. VpsT is a transcriptional regulator required for expression of vps biosynthesis genes and the development of rugose colonial morphology in Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor. J. Bacteriol. 186:1574-1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, X., S. Schauder, N. Potier, A. Van Dorsselaer, I. Pelczer, B. L. Bassler, and F. M. Hughson. 2002. Structural identification of a bacterial quorum-sensing signal containing boron. Nature 415:545-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costerton, J. W., Z. Lewandowski, D. E. Caldwell, D. R. Korber, and H. M. Lappin-Scott. 1995. Microbial biofilms. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 49:711-745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cotter, P. A., and S. Stibitz. 2007. c-di-GMP-mediated regulation of virulence and biofilm formation. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10:17-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Lorenzo, V., and K. N. Timmis. 1994. Analysis and construction of stable phenotypes in gram-negative bacteria with Tn5- and Tn10-derived minitransposons. Methods Enzymol. 235:386-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dutta, R., and M. Inouye. 1996. Reverse phosphotransfer from OmpR to EnvZ in a kinase−/phosphatase+ mutant of EnvZ (EnvZ.N347D), a bifunctional signal transducer of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 271:1424-1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faruque, S. M., M. J. Albert, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1998. Epidemiology, genetics, and ecology of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:1301-1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faruque, S. M., K. Biswas, S. M. Udden, Q. S. Ahmad, D. A. Sack, G. B. Nair, and J. J. Mekalanos. 2006. Transmissibility of cholera: in vivo-formed biofilms and their relationship to infectivity and persistence in the environment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:6350-6355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fong, J. C., K. Karplus, G. K. Schoolnik, and F. H. Yildiz. 2006. Identification and characterization of RbmA, a novel protein required for the development of rugose colony morphology and biofilm structure in Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 188:1049-1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hammer, B. K., and B. L. Bassler. 2003. Quorum sensing controls biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae. Mol. Microbiol. 50:101-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hammer, B. K., and B. L. Bassler. 2007. Regulatory small RNAs circumvent the conventional quorum sensing pathway in pandemic Vibrio cholerae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104:11145-11149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herrero, M., V. de Lorenzo, and K. N. Timmis. 1990. Transposon vectors containing non-antibiotic resistance selection markers for cloning and stable chromosomal insertion of foreign genes in gram-negative bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 172:6557-6567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heydorn, A., B. K. Ersboll, M. Hentzer, M. R. Parsek, M. Givskov, and S. Molin. 2000. Experimental reproducibility in flow-chamber biofilms. Microbiology 146:2409-2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heydorn, A., A. T. Nielsen, M. Hentzer, C. Sternberg, M. Givskov, B. K. Ersboll, and S. Molin. 2000. Quantification of biofilm structures by the novel computer program COMSTAT. Microbiology 146:2395-2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higgins, D. A., M. E. Pomianek, C. M. Kraml, R. K. Taylor, M. F. Semmelhack, and B. L. Bassler. 2007. The major Vibrio cholerae autoinducer and its role in virulence factor production. Nature 450:883-886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jobling, M. G., and R. K. Holmes. 1997. Characterization of hapR, a positive regulator of the Vibrio cholerae HA/protease gene hap, and its identification as a functional homologue of the Vibrio harveyi luxR gene. Mol. Microbiol. 26:1023-1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laub, M. T., E. G. Biondi, and J. M. Skerker. 2007. Phosphotransfer profiling: systematic mapping of two-component signal transduction pathways and phosphorelays. Methods Enzymol. 423:531-548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lauriano, C. M., C. Ghosh, N. E. Correa, and K. E. Klose. 2004. The sodium-driven flagellar motor controls exopolysaccharide expression in Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 186:4864-4874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lefebvre, B., P. Formstecher, and P. Lefebvre. 1995. Improvement of the gene splicing overlap (SOE) method. BioTechniques 19:186-188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lenz, D. H., K. C. Mok, B. N. Lilley, R. V. Kulkarni, N. S. Wingreen, and B. L. Bassler. 2004. The small RNA chaperone Hfq and multiple small RNAs control quorum sensing in Vibrio harveyi and Vibrio cholerae. Cell 118:69-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lim, B., S. Beyhan, J. Meir, and F. H. Yildiz. 2006. Cyclic-diGMP signal transduction systems in Vibrio cholerae: modulation of rugosity and biofilm formation. Mol. Microbiol. 60:331-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mascher, T., J. D. Helmann, and G. Unden. 2006. Stimulus perception in bacterial signal-transducing histidine kinases. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 70:910-938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meibom, K. L., M. Blokesch, N. A. Dolganov, C. Y. Wu, and G. K. Schoolnik. 2005. Chitin induces natural competence in Vibrio cholerae. Science 310:1824-1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller, J. H. 1972. Assay of β-galactosidase, p. 352-355. In J. H. Miller (ed.), Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 32.Miller, M. B., K. Skorupski, D. H. Lenz, R. K. Taylor, and B. L. Bassler. 2002. Parallel quorum sensing systems converge to regulate virulence in Vibrio cholerae. Cell 110:303-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 34.Schauder, S., K. Shokat, M. G. Surette, and B. L. Bassler. 2001. The LuxS family of bacterial autoinducers: biosynthesis of a novel quorum-sensing signal molecule. Mol. Microbiol. 41:463-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shikuma, N. J., and F. H. Yildiz. 2009. Identification and characterization of OscR, a transcriptional regulator involved in osmolarity adaptation in Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 191:4082-4096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Skerker, J. M., M. S. Prasol, B. S. Perchuk, E. G. Biondi, and M. T. Laub. 2005. Two-component signal transduction pathways regulating growth and cell cycle progression in a bacterium: a system-level analysis. PLoS Biol. 3:e334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stock, A. M., V. L. Robinson, and P. N. Goudreau. 2000. Two-component signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69:183-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Waters, C. M., W. Lu, J. D. Rabinowitz, and B. L. Bassler. 2008. Quorum sensing controls biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae through modulation of cyclic di-GMP levels and repression of vpsT. J. Bacteriol. 190:2527-2536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yildiz, F. H., N. A. Dolganov, and G. K. Schoolnik. 2001. VpsR, a member of the response regulators of the two-component regulatory systems, is required for expression of vps biosynthesis genes and EPSETr-associated phenotypes in Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor. J. Bacteriol. 183:1716-1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yildiz, F. H., X. S. Liu, A. Heydorn, and G. K. Schoolnik. 2004. Molecular analysis of rugosity in a Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor phase variant. Mol. Microbiol. 53:497-515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yildiz, F. H., and G. K. Schoolnik. 1999. Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor: identification of a gene cluster required for the rugose colony type, exopolysaccharide production, chlorine resistance, and biofilm formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:4028-4033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu, J., and J. J. Mekalanos. 2003. Quorum sensing-dependent biofilms enhance colonization in Vibrio cholerae. Dev. Cell 5:647-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhu, J., M. B. Miller, R. E. Vance, M. Dziejman, B. L. Bassler, and J. J. Mekalanos. 2002. Quorum-sensing regulators control virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:3129-3134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.