Abstract

Nitrogenase activity in Rhodospirillum rubrum and in some other photosynthetic bacteria is regulated in part by the availability of light. This regulation is through a posttranslational modification system that is itself regulated by PII homologs in the cell. PII is one of the most broadly distributed regulatory proteins in nature and directly or indirectly senses nitrogen and carbon signals in the cell. However, its possible role in responding to light availability remains unclear. Because PII binds ATP, we tested the hypothesis that removal of light would affect PII by changing intracellular ATP levels, and this in turn would affect the regulation of nitrogenase activity. This in vivo test involved a variety of different methods for the measurement of ATP, as well as the deliberate perturbation of intracellular ATP levels by chemical and genetic means. To our surprise, we found fairly normal levels of nitrogenase activity and posttranslational regulation of nitrogenase even under conditions of drastically reduced ATP levels. This indicates that low ATP levels have no more than a modest impact on the PII-mediated regulation of NifA activity and on the posttranslational regulation of nitrogenase activity. The relatively high nitrogenase activity also shows that the ATP-dependent electron flux from dinitrogenase reductase to dinitrogenase is also surprisingly insensitive to a depleted ATP level. These in vivo results disprove the simple model of ATP as the key energy signal to PII under these conditions. We currently suppose that the ratio of ADP/ATP might be the relevant signal, as suggested by a number of recent in vitro analyses.

The PII family of regulatory proteins is one of the most broadly distributed in nature, being found in all three domains of life (1, 20, 39, 51). PII was originally found to be involved in the regulation of glutamine synthetase (GS) activity by interaction with adenylyltransferase (ATase or GlnE, encoded by glnE) (63, 65). However, PII has subsequently been shown to regulate many other processes involving nitrogen assimilation and metabolism, by directly interacting with different proteins, termed PII receptors (51). In many organisms, more than one PII homolog has been identified. The “housekeeping” homolog is usually referred to as GlnB, encoded by glnB, with other secondary homologs named GlnK, GlnK2, GlnJ, GlnY, GlnZ, or Pz (1, 12, 47, 69, 78). In a few species of Archaea, a distinct group of PII proteins was named NifI, which is encoded by the nifH-linked gene (39).

Because of its physiological diversity, the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodospirillum rubrum is a good model organism in which to study the role of PII. It has three PII homologs—GlnB, GlnK, and GlnJ—that play distinct and overlapping functions by interacting with at least six receptors in the cell (71, 78, 81). Some of these are common to other bacteria, such as GlnE (ATase) that is involved in the regulation for GS activity, the two-component regulatory protein NtrB, and the ammonium transporter (gas channel) AmtB1 (71, 78). Other PII receptors in R. rubrum are involved in nitrogen fixation: NifA is the transcriptional activator for nitrogen fixation genes, and two additional proteins perform posttranslational regulation of nitrogenase activity (78-80).

In Klebsiella pneumoniae and Azotobacter vinelandii NifA activity is regulated by direct interaction with NifL, another nif gene product, and PII is involved in the NifA-NifL interaction (24, 29, 44, 45). However, in R. rubrum, NifA activity requires direct interaction with the uridylylated form of GlnB, and neither GlnK nor GlnJ can activate NifA (81). A similar regulation of NifA activity by GlnB has been reported in Azospirillum brasilense, Rhodobacter capsulatus, and Herbaspirillum seropedicae (2, 4, 18).

The posttranslational regulation of nitrogenase activity in R. rubrum involves the reversible mono-ADP-ribosylation of dinitrogenase reductase, the terminal electron donor to dinitrogenase (53, 80). Two enzymes perform this reversible reaction. Dinitrogenase reductase ADP-ribosyl transferase (referred to as DRAT, the gene product of draT) carries out the transfer of the ADP-ribose from NAD to one subunit of the dinitrogenase reductase homodimer, resulting in the inactivation of that enzyme. The ADP-ribose group attached to dinitrogenase reductase can be removed by another enzyme, dinitrogenase reductase activating glycohydrolase (referred to as DRAG, the gene product of draG), thus restoring nitrogenase activity. This regulatory system has also been found in A. brasilense, Azospirillum lipoferum, R. capsulatus, and a few other nitrogen-fixing bacteria (21, 48, 49, 74). It negatively regulates nitrogenase activity in response to exogenous NH4+ or to energy limitation in the form of dark shift (in the cases of R. rubrum and R. capsulatus) or anaerobiosis shifts (in A. brasilense) (41, 48, 73). The regulation of the ADP-ribosylation of dinitrogenase reductase is effected through the posttranslational regulation of both DRAT and DRAG activities, and PII is involved in the regulation of both enzymes (25, 27, 28, 67, 70, 77, 78).

The activity of PII and its interaction with different receptors is mainly dependent on the conformation of PII in the cell. PII exists in multiple forms, depending on the carbon and nitrogen levels in the cell. The conformational change of PII is caused by its direct binding of small molecules such as 2-oxoglutarate or α-KG (as a signal of carbon excess) and ADP/ATP, and indirectly by its covalent modification of the protein in response to nitrogen status (16, 17, 31-34, 51, 66, 71). In many bacteria, PII is modified by uridylylation, which is carried out by a bifunctional, uridylyltransferase/uridylyl-removing enzyme (UTase/UR). This enzyme is encoded by glnD and senses the intracellular concentration of glutamine in the cell (32). Through the action of UTase/UR the uridylylated form of PII signals a nitrogen deficiency.

Because the DRAT/DRAG system responds to changes in energy and has been shown to be regulated by PII, it was a plausible hypothesis that PII itself senses the status of energy in some way (78, 82). For example, the DRAT/DRAG regulatory system in R. rubrum mutants lacking GlnB and GlnJ failed to lower nitrogenase activity in response to a removal of light (78). Similarly, AmtB1 sequesters PII under conditions of nitrogen excess, and the mutation of amtB1 in R. rubrum eliminated the regulation of nitrogenase activity not only in response to NH4+ addition, but also in response to a shift to darkness (82). Given the clear role of ATP binding on PII function in vitro (51), the level of ATP was an obvious candidate for the energy signal sensed by PII in vivo. However, previous studies by two different groups showed different conclusions. Li et al. reported that the pool of ATP in R. rubrum decreased rapidly following the dark shift and then recovered slowly and partially. The ATP pool fully recovered after the cells were returned to light (40). In contrast, using a different extraction and detection method, Paul and Ludden saw that the pool of ATP decreased slightly and then increased rapidly within 30 s of a dark shift. These authors also reported further ATP fluctuations during the incubation in the dark, but overall the pool of ATP remained high (56). Recently, a variety of in vitro analysis have indicated that the ratio of ADP to ATP might be critical for a number of PII functions (26, 31, 66, 71). Nevertheless, there has been no direct in vivo test of the impact of changes in internal ATP levels on PII function, and the focus of the present study was to measure that impact by monitoring the DRAT/DRAG system.

ATP plays many critical roles in living cells (3, 7, 11, 13), and there are clearly cases where absolute ATP level is also an important indicator of the physiological state in prokaryotes (54, 55, 59, 60). Schneider et al. reported that the changes in ATP concentration affect the transcription of the rrnB P1 promoter (59). These authors perturbed the internal ATP levels through the use of a purE mutant, which has an impaired purine synthesis pathway, and showed that a sixfold-elevated ATP level correlated with high rrnB P1 promoter activity (59).

However, there are three main challenges in attempting to correlate ATP levels with physiological phenomena. (i) The metabolism of the cell must be stopped rapidly so that the ATP pool is not altered during processing. (ii) ATP exists in association with many proteins in the cell, and it is impossible to know which fraction of the ATP is liberated by different extraction methods. (iii) Finally, it is impossible to know which fraction of this variously bound ATP pool is relevant for any single ATP-binding protein.

Many ATP extraction methods have been developed and tested in Escherichia coil and other bacteria, but these have produced dramatically different results (37, 46, 60). Even a single method performs differently when applied to different organisms (37, 46). An alternative technique to measure ATP involves the injection of firefly luciferase into mammalian cells (5, 36). The luciferase reporter system has also been used for monitoring ATP in the intact cells of E. coli and R. capsulatus (10, 14, 22, 60). However, this method has some challenges for its use. The substrate luciferin must be rapidly introduced into the cell, and this has typically demanded that the cells be treated with a permeabilizing drug such as polymyxin B (10, 14, 60). Such permeabilization almost certainly perturbs the ATP pool to some extent and prevents monitoring rapid changes in that pool. Another problem is that wild-type luciferase has a very low Km for ATP and is therefore saturated even if ATP levels fluctuate (14). However, Schneider et al. studied the change in ATP concentration and its relationship with regulation of rRNA expression in E. coli by using a variant of luciferase (with an H245F substitution) that raises the enzyme's Km for ATP to a physiologically reasonable level (6, 60).

We demonstrate here the technical problems with different in vitro ATP assays and then show that a luciferase reporter system in R. rubrum coincidentally avoids many of these problems and allows us to monitor the change of ATP concentration in the cells after dark-light shifts or the addition of NH4+. We then use purE mutants in R. rubrum to perturb intracellular ATP levels deliberately by providing different exogenous adenine levels. In the presence of limited concentrations of adenine, the ATP concentration was dramatically decreased in purE mutants, but the effects on nitrogenase activity and its regulation were surprisingly small; only the recovery of nitrogenase activity after the restoration of light was strongly affected. The modification state of GlnB was also altered under these conditions, a finding consistent with the model that PII senses energy status in some way and then regulates DRAT/DRAG activity. Based on these results and a number of recent biochemical analyses that indicate the importance of the ADP/ATP ratio for the regulation of PII functions in vitro (26, 31, 66, 71), we suggest that the important impact of light and dark in vivo might be on the ADP pool, which then affects that ratio. The results also suggest that the ATP-dependent electron transfer from dinitrogenase reductase to dinitrogenase is surprisingly insensitive to severely decreased ATP levels.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth conditions and in vivo nitrogenase activity assay.

E. coli was grown in LC medium (similar to Luria-Bertani medium, but with 5 g of NaCl/liter). R. rubrum was grown in yeast extract-supplemented malate-NH4+ (SMN) rich medium, malate-glutamate (MG) medium, or nitrogen-free (MN−) malate medium as described previously (19, 38, 41). The whole-cell nitrogenase activity assay and the methods of dark/light shifts and NH4+ treatments have been described previously (72). Antibiotics were used as necessary at the levels described previously (79).

ATP extraction and assay.

Four different extraction methods were compared for their effectiveness in extracting ATP from R. rubrum grown in MG medium involving the use of boiling, trichloroacetic acid (TCA), formic acid, or formaldehyde. The boiling and TCA methods were based on previously published methods (46) with some modifications. For the TCA method, 0.2 ml of R. rubrum culture was quickly mixed with 0.2 ml of 10% TCA and 4 mM EDTA solution. After incubation on ice for 10 min, the extract was centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was saved at −80°C for the ATP assay. For the boiling method, 0.1 ml of culture was mixed with 0.9 ml of preboiling Tris-EDTA buffer (0.1 M Tris and 2 mM EDTA with pH at 7.75), boiled for 2 min at 100°C, and incubated on ice for 10 min, and the extract was centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was saved at −80°C for the ATP assay. The formic acid method was performed according to a published method (30) with the following modification: 0.5 ml of culture was quickly mixed with 0.1 ml of 2 M formic acid. After incubation on ice for 30 min, the extract was centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was saved for the ATP assay. The formaldehyde method was based on the published method (43) except that 1 ml of culture was quickly mixed with 0.1 ml of 1.9% formaldehyde. After incubation on ice for 10 min, the extract was centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was discarded. Pellets were dissolved in 50 μl of 0.1 M KOH by vortexing and incubated on ice for 30 min, and then 50 μl of 8.8% H3PO4 was added to neutralize the KOH. The extract was centrifuged again at 20,000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was saved at −80°C for the ATP assay.

The ENLITEN ATP assay system bioluminescence detection kit (Promega, Madison, WI) was used for the ATP assay. Before carrying out the assay, samples from TCA, formic acid, and formaldehyde extraction were diluted 100-fold with Tris-EDTA buffer, and the boiled samples were diluted 10-fold in the same buffer. The luminescence was measured with a TD-20/20 luminometer (Turner Biosystems, Sunnyvale, CA) with a 2-s delay period and a 10-s integration period. The ATP concentration was expressed as nmol per mg of dry weight, based on previous data that the dry weight of R. rubrum was 0.28 ± 0.01 mg per ml of culture at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1 (76).

Expression of luciferase in R. rubrum and assay of ATP concentration in intact cells.

The luciferase expression vector was constructed as follows. The promoter region of aacC1 (gentamicin resistance [Gmr] gene) from pUCGM (62) was first amplified by PCR and cloned into pBSKS(−) (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), yielding pUX2519. An NdeI site was created at the first methionine codon of aacC1. The structural gene encoding Photimus pyralis luciferase with the H245F substitution was then amplified from a pGEX derivative (60) (kindly provided by R. Gourse) and subcloned into pUX2519, yielding pUX2523. Similarly, an NdeI site was created at the start codon of the luciferase gene so that it could be ligated perfectly to the aacC1 promoter. The fragment carrying the region encoding the luciferase-H245F linked with the promoter of aacC1 was then cloned into pRK404 (15), yielding pUX2524, which was transferred into R. rubrum by a standard triparental mating procedure as described previously (23).

The ATP assay in intact cells of R. rubrum was done in an assay buffer containing 10 mM HEPES (pH 6.8), 150 mM NaCl, 0.6 mM KCl, 10 mM MgSO4, 0.2% glucose, and 4 mM luciferin unless indicated otherwise. Polymyxin B was only used in the initial experiments and omitted in the routine assays because it was unnecessary for the assay with R. rubrum cells. Then, 10 μl of R. rubrum cells was mixed with 100 μl of assay buffer by brief vortexing, and the relative light units (RLU) were measured with a TD-20/20 luminometer with a 2-s delay period and a 2-min integration period. The ATP assay was done in a 12-by-15-mm tube under aerobic conditions, since oxygen is necessary for luciferase activity. Control experiments showed that the RLU were constant in the range of 30 s to 15 min (data not shown). In vivo ATP concentration is expressed as RLU per mg of dry weight.

Cloning and construction of purE mutant from R. rubrum.

The sequence of the purE homolog of R. rubrum was obtained from the genomic sequence of R. rubrum, which is available from the U.S. Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute (http://genome.jgi-psf.org/finished_microbes/rhoru/rhoru.home.html). A 4-kb fragment of the purEK region was amplified from the genomic DNA of wild-type R. rubrum using Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene) and a pair of oligonucleotide primers with StuI and PstI sites at their ends. After digestion with StuI and PstI, the amplified DNA fragment was cloned into pUX19 (42), yielding pUX2112, which was confirmed by sequencing.

To construct the purE insertion mutants, pUX2112 was digested with EcoRV, which cuts purE at codon 143, and a Gmr cartridge from pUCGM (62) was inserted in either orientation, yielding pUX2362 and pUX2363. Both pUX2362 and pUX2363 were digested with PvuII, and the fragments containing pruE::aacC1were cloned into pSUP202 (64), yielding pUX2364 and pUX2365, respectively. These plasmids were transformed into E. coli S17-1 (64) and then conjugated into R. rubrum wild-type (UR2) by a previously described method (41). Streptomycin-resistant Gmr R. rubrum colonies were selected and replica printed to identify chloramphenicol-sensitive colonies resulting from a double-crossover recombination event. In UR2187 (purE1::aacC1) purE and aacC1 are transcribed in the same direction, whereas in UR2188 (purE2::aacC1) they are transcribed in the opposite direction.

Generating GlnB antiserum and immunoblotting procedures.

R. rubrum GlnB was overexpressed and purified as described previously (83). For generation of R. rubrum GlnB antiserum, a rabbit was immunized by intradermal injection of 1 mg of pure R. rubrum GlnB protein with complete Freund adjuvant and then with two subsequent boosts. The serum was collected at 4 weeks after the final boost.

As described previously, a TCA precipitation method was used to extract proteins, and a low cross-linker (ratio of acrylamide-bisacrylamide, 172/1) Tricine gel (16.5%) was used to separate the modified and unmodified PII (58, 82). Proteins obtained from sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis were electrophoretically transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane, immunoblotted with polyclonal antibody against R. rubrum GlnB, and visualized with horseradish peroxidase color detection reagents (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA).

RESULTS

Different extraction methods yield very different measurements of ATP concentrations in R. rubrum. To monitor the ATP concentration in R. rubrum that was grown in MG medium, four extraction methods were used, as described in detail in Materials and Methods. As shown in Table 1, the TCA method gave the highest values, which is consistent with previous observations made with other bacteria (37, 46). Formic acid extraction gave slightly lower values. The boiling method is very simple, but this method and formaldehyde extraction gave much lower values than the other two methods for R. rubrum. Given the challenges noted above, it is tempting to favor methods that give higher ATP values, since these high values suggest both that metabolism has been rapidly terminated and that ATP was effectively extracted. However, the biologically important value for ATP is probably not the total, but rather the pool available to the particular biological process in question. Because of the difficulty in knowing this by any in vitro methods, we considered an in vivo assay to complement these data.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of ATP levels in MG-grown R. rubrum wild type (UR2) with different extraction methods

| Method | Mean ATP concn (nmol/mg of dry wt) ± SD |

|---|---|

| TCA extraction | 5.29 ± 0.39 |

| Formic acid extraction | 4.57 ± 0.43 |

| Formaldyhyde extraction | 0.93 ± 0.14 |

| Boiling | 2.50 ± 0.29 |

Development of a luciferase reporter system to measure ATP in vivo in R. rubrum.

Alternative techniques to measure ATP based on firefly luciferase have been developed and used in bacterial and mammalian cells. Luciferase has been injected into mammalian cells to monitor ATP (5, 36), and a luciferase reporter system has also been used to monitor ATP in intact cells of E. coli and R. capsulatus (10, 14, 22, 60). The main challenge for this assay in bacterial systems is that cells typically must be treated with permeabilizing drugs such as polymyxin B to allow diffusion of luciferin into cells. Presumably, this also allows time for ATP metabolism and flux through the bacterial membrane, so this treatment almost certainly interferes with one's ability to rapidly monitor ATP pools with confidence.

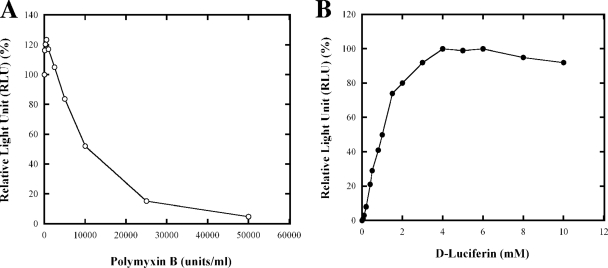

As described in Materials and Methods, an expression vector for the luciferase variant was constructed. This variant (with a H245F substitution) has a Km for Mg-ATP of 830 μM, whereas the Km for Mg-ATP of wild-type luciferase is 160 μM (6), and is thus able to respond to the changes in ATP concentration in the predicted physiological range (14, 60). The gene encoding H245F luciferase expressed from the aacC1 (Gmr gene) promoter was cloned into a low-copy plasmid pRK404, yielding pUX2524. The otherwise wild-type R. rubrum strain with this plasmid was termed UR2379. We first titrated the RLU at different concentrations of polymyxin B and luciferin. As shown in Fig. 1A, in the presence of 4 mM luciferin, a high RLU was detected even without treatment of polymyxin B. Treatment with very low levels of polymyxin B caused a slight but reproducible increase in RLU, but concentrations >5,000 U/ml dramatically decreased the RLU. Thus, polymyxin B was not necessary for high luciferase detection in R. rubrum, which was surprising because of the completely opposite results seen in R. capsulatus, in which 10,000 to 50,000 U of polymyxin B/ml are required to reach the maximal RLU (14). As shown in Fig. 1B, in the absence of polymyxin B, the maximal RLU in R. rubrum was reached when the luciferin concentration in the assay was 4 to 6 mM. The apparent ability of luciferin to diffuse into the cells without treatment with polymyxin B dramatically simplifies the assay in R. rubrum and eliminates concerns over ATP loss. We then used this in vivo reporter system to monitor the change in ATP concentration in R. rubrum during dark-light shifts and NH4+ addition.

FIG. 1.

In vivo analysis of ATP levels in R. rubrum strain UR2379 (wild type with plasmid pUX2524 carrying the luciferase reporter system). (A) Effect of the concentration of polymyxin B on the RLU at 4 mM luciferin. The values are normalized to the value obtained when polymyxin B concentration was at 0 mM. (B) Effect of the concentration of luciferin on the RLU in the absence of polymyxin B. The values are normalized to the maximum value obtained, when the luciferin concentration was 4 mM. Aliquots (10 μl) of cells were mixed with 100 μl of luciferase assay buffer solution, and the luminescence signal was measured with a luminometer for 2 min. Each point represents an average of at least three replicate assays, with a standard deviation of <10%.

Treatment with uncoupling agents dramatically lowers the ATP pool and nitrogenase activity.

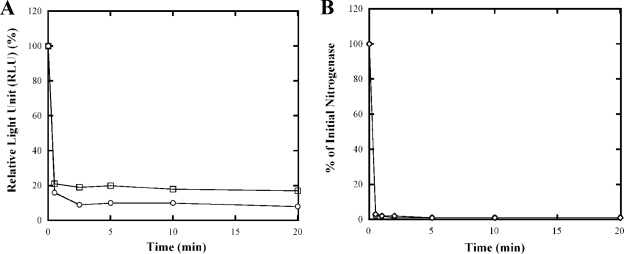

The uncoupling agents carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone (FCCP) and carbonyl cyanide 3-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) have been previously used in R. rubrum to study the role of adenylate nucleotide pools in the regulation of nitrogenase activity (35, 52, 56). Both were shown to cause a rapid decrease of both the ATP pool and the nitrogenase activity. As a control for the effectiveness of the in vivo luciferase reporter system in monitoring the changes in ATP pools, UR2379 was treated with FCCP or CCCP at final concentrations of 25 and 30 μM, respectively, and the ATP concentration and nitrogenase activity were monitored in intact cells. As demonstrated in Fig. 2A, the ATP pool was rapidly diminished after the treatments, but some residual level of ATP remained. This result is consistent with previous results of ATP measurement after TCA extraction (52). Similarly, almost all nitrogenase activity was eliminated in 2 min after the treatment with both FCCP and CCCP (Fig. 2B). Thus, the luciferase method reports an extremely rapid and substantial drop in ATP levels, which correlate with a loss of nitrogenase activity.

FIG. 2.

Effect of FCCP and CCCP on ATP pools (A) and nitrogenase activity (B) in R. rubrum strain UR2379 (wild type carrying the luciferase reporter system). At time zero, FCCP (○) or CCCP (□) was added to MG-grown cultures at final concentrations of 25 and 30 μM, respectively. At the times indicated, 1-ml aliquots of cells were withdrawn anaerobically and assayed under illumination for nitrogenase activity for 2 min. Initial nitrogenase activity (100%) in UR2379 was ∼700 nmol of ethylene produced per h per ml of cells at an OD600 of 1.0. Similarly, 10-μl aliquots of cells were mixed with 100 μl of luciferase assay buffer, and the luminescence signal was measured with a luminometer. The initial ATP concentration is ∼85,000 RLU/ml of cells at an OD600 of 1.0. Each point represents an average of at least three replicate assays, with standard deviation of <10%.

ATP concentration changes slightly in response to removal of light, but not after NH4+ addition.

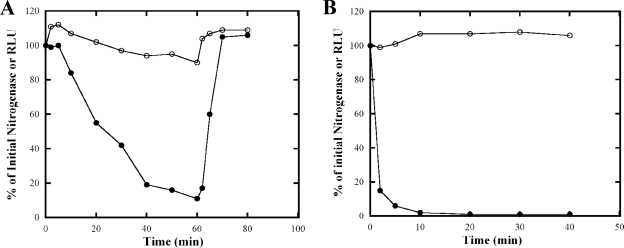

In R. rubrum, the DRAT/DRAG regulatory system controls nitrogenase activity in response to exogenous NH4+ and to dark-light shifts (53, 80). One hypothesis for the regulation of DRAT/DRAG in response to a dark-light shifts has been that the shift to darkness causes a change in the ATP pool, which is sensed by PII, and PII in turn regulates DRAT/DRAG activities through protein-protein interactions. We therefore monitored changes of the ATP pool and nitrogenase activity in intact cells of UR2379 (wild-type R. rubrum expressing luciferase) during dark-light shifts and after NH4+ addition. MG (malate-glutamate medium)-grown cultures were used for dark-light shifts, and MN− (malate-NH4+-free medium)-grown cultures were used for NH4+ treatment, since these respond to NH4+ more rapidly than do MG-grown cultures (77). As shown in Fig. 3A, the ATP concentration increased slightly but reproducibly just after the cells were shifted to dark and then decreased slowly. After 60 min of darkness, the ATP concentration was still ca. 90% of the initial level. ATP concentration increased ca. 10 to 15% after a return to light. The change in nitrogenase activity was much more dramatic, as has been demonstrated numerous times (23, 41, 72). NH4+ addition also had a dramatic effect on nitrogenase activity but an even less apparent effect on measurable ATP (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Changes in nitrogenase activity and in vivo ATP concentration of R. rubrum UR2379 (wild type carrying the luciferase reporter system) in response to dark-light shifts (panel A) or the addition of NH4+ (B). (A) UR2379 was grown in MG medium for about 2 days, and cells were shifted to dark at time zero and returned to light at 60 min. The nitrogenase activity (•) and ATP concentration (○) were measured as described in Fig. 2. Similar initial nitrogenase activity and ATP concentration were seen as in Fig. 2. (B) UR2379 was grown in MN− medium for about 2 days, and NH4Cl was added at final concentration of 10 mM at time zero. The nitrogenase activity (•) and ATP concentration (○) was measured as described in Fig. 2. The initial nitrogenase activity (100%) in UR2379 was ∼200 nmol of ethylene produce per h per ml of cells at an OD600 of 1.0. The initial ATP concentration was ∼76,000 RLU per ml of cells at an OD600 of 1.0.

The very modest change in the ATP pool after a shift to dark was surprising to us, since we expected the change of the ATP pool would be more dramatic. It therefore seemed unlikely that the small change of the ATP pool in response to these shifts is responsible for the dramatic regulation of nitrogenase activity.

Construction of R. rubrum purE mutants to perturb ATP levels in vivo.

To further study the mechanism by which energy status affects nitrogenase regulation in R. rubrum, we constructed purE mutants, which are altered in the IMP synthesis pathway. In E. coli, IMP functions as a precursor for both AMP and GMP nucleotides, and the pathway consists of 11 enzymatic steps (75). In the sixth step 5′-phosphoribosylaminoimidazole (AIR) is converted to 5′-phosphoribosyl-N-5-aminoimidazole carboxylate (CAIR). Previously, this reaction was thought to be catalyzed by a single enzyme (AIR carboxylase), consisting of two subunits encoded by purE and purK. However, Mueller et al. established that these genes encode two different enzymes, N5-carboxyaminoimidazole ribonucleotide (NCAIR) isomerase/mutase and NCAIR synthetase, respectively (50).

As in E. coli and many other bacteria, purE and purK are genetically adjacent in R. rubrum. As described in Materials and Methods, R. rubrum mutants were constructed in which an aacC1 gene was inserted into purE in the same orientation as purE (UR2187) or with the aacC1 in the opposite orientation (UR2188).

These purE mutants are able to grow in rich (SMN) medium, but more slowly than wild type. They failed to grow in minimal MG medium, but they grew normally in SMN and MG media when supplemented with 0.5 mM adenine. To avoid selection for suppressor mutations, we supplemented SMN medium with 0.5 mM adenine when we constructed these purE mutants.

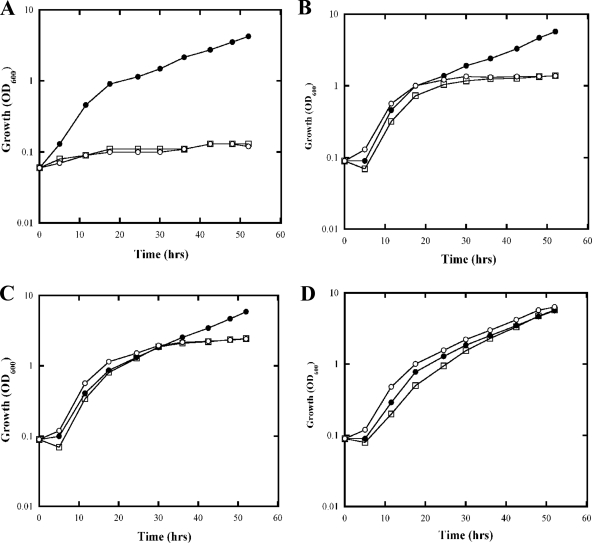

The growth of purE mutants in MG medium was monitored at different levels of added adenine. As shown in Fig. 4A, purE mutants failed to grow in MG medium without adenine. When supplemented with 0.05 mM adenine in MG medium, purE mutants showed doubling times similar to those of the wild type initially but slowed down drastically when the OD600 reached about 1 at about 24 h, presumably because the adenine was depleted (Fig. 4B). When supplemented with 0.1 mM adenine in MG medium, the growth of purE mutants slowed when the OD600 reached about 2 at about 30 h (Fig. 4C), while 0.5 mM adenine allowed the purE mutants to grow similarly to the wild type (Fig. 4D). To study the effect of a perturbed level of ATP, we grew the purE mutant cultures in limiting adenine and examined the cultures after 40 to 44 h, where cultures were in either stationary phase (at 0.05 or 0.1 mM adenine) or late log phase (at 0.5 mM adenine).

FIG. 4.

Growth curve of UR2 (wild type) (•), UR2187 (purE mutant) (□), and UR2188 (purE mutant) (○) in MG with different concentrations of adenine: 0 mM (A), 0.05 mM (B), 0.1 mM (C), and 0.5 mM (D).

The ATP pool in R. rubrum purE mutants is dramatically perturbed by limiting adenine.

pUX2524 (expressing H245F luciferase) was transferred into the purE mutants (UR2187 and UR2188), yielding UR2380 and UR2381. To study the effect of depletion of ATP on the nitrogenase activity, cells were grown in MG with different levels of adenine for 40 to 44 h to either late log or stationary phase as shown in Fig. 4. The ATP concentration was measured directly in vivo with the luciferase reporter system, as well as in vitro after TCA extraction. In this assay, the values for the wild type and the purE mutants cannot be compared with precision because the exact values for the mutants are a function of their degree of adenine starvation. Nevertheless, this allows us to compare methods and approximate the ATP levels in the wild type and the purE mutants.

As shown in Table 2, when assayed after TCA extraction, the ATP concentration in purE mutants (UR2187, UR2188, UR2380, and UR2381) is ca. 25% of that seen in wild-type controls (UR2 and UR2379) when grown in MG with 0.05 or 0.1 mM adenine. However, the ATP concentration in these purE mutants is much higher (ca. 70% of the wild type) when grown in MG with 0.5 mM adenine. When directly measured in intact cells, the ATP concentration in the purE mutants is less than 5% of that seen in wild-type controls when grown in MG with 0.05 or 0.1 mM adenine. As seen with the in vitro assay, the ATP concentration in these purE mutants was more comparable to that of the wild type when grown in MG with 0.5 mM adenine. Thus, both methods show that adenine-starved purE mutants have significantly lower ATP levels, although the magnitude of these differences is much greater using the luciferase assay. We assume that the in vitro assay measures the total ATP pool and the in vivo luciferase system measures some free ATP pool, and it seems plausible that the latter pools would be more dramatically affected by adenine depletion.

TABLE 2.

ATP levels in R. rubrum wild type and purE mutants when they were grown in MG medium containing 0.05, 0.1, or 0.5 mM adenine

| Adenine concn (mM) and R. rubrum strain | Genotype and plasmid | Mean ATP level ± SDa

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro assay after TCA extraction (nmol/mg of dry wt) | In vivo luciferase assay (RLU/mg of dry wt) | ||

| 0.05 | |||

| UR2 | Wild type | 4.46 ± 0.50 | NT |

| UR2187 | ΔpurE1::aacC1 mutant | 1.04 ± 0.07 | NT |

| UR2188 | ΔpurE2::aacC1 mutant | 0.89 ± 0.04 | NT |

| UR2379 | Wild type with pUX2524 (luciferase reporter) | 3.93 ± 0.05 | 318,000 ± 12,500 |

| UR2380 | ΔpurE1::aacC1 mutant with pUX2524 | 1.07 ± 0.07 | 5,400 ± 1,000 |

| UR2381 | ΔpurE2::aacC1 mutant with pUX2524 | 1.04 ± 0.14 | 5,400 ± 900 |

| 0.1 | |||

| UR2 | Wild type | 4.39 ± 0.07 | NT |

| UR2187 | ΔpurE1::aacC1 mutant | 1.04 ± 0.07 | NT |

| UR2188 | ΔpurE2::aacC1 mutant | 0.96 ± 0.04 | NT |

| UR2379 | Wild type with pUX2524 | 5.18 ± 0.32 | 492,000 ± 33,900 |

| UR2380 | ΔpurE1::aacC1 mutant with pUX2524 | 1.14 ± 0.02 | 21,000 ± 1,300 |

| UR2381 | ΔpurE2::aacC1 mutant with pUX2524 | 1.21 ± 0.14 | 19,000 ± 2,300 |

| 0.5 | |||

| UR2 | Wild type | 4.39 ± 0.14 | NT |

| UR2187 | ΔpurE1::aacC1 mutant | 2.78 ± 0.07 | NT |

| UR2188 | ΔpurE2::aacC1 mutant | 3.14 ± 0.14 | NT |

| UR2379 | Wild type with pUX2524 | 4.50 ± 0.61 | 563,000 ± 34,600 |

| UR2380 | ΔpurE1::aacC1 mutant with pUX2524 | 3.25 ± 0.28 | 332,000 ± 30,000 |

| UR2381 | ΔpurE2::aacC1 mutant with pUX2524 | 3.46 ± 0.32 | 402,000 ± 49,600 |

ATP levels were determined by in vitro assay after TCA extraction or determined by directly in vivo assay with luciferase reporter system as described in Materials and Methods. NT, not tested.

Regulation of nitrogenase activity in response to dark-light shifts in these purE mutants.

As mentioned in the introduction, because nitrogen fixation catalyzed by nitrogenase is a very energy-demanding process, the nitrogenase activity in R. rubrum is tightly regulated at both transcriptional and posttranslational levels. First, the transcription of the nif operon is dependent on the NifA activity, which is regulated by GlnB. Second, nitrogenase activity is regulated posttranslationally by DRAT/DRAG. Under N2-fixing conditions, DRAG is active and DRAT is inactive, but after the addition of NH4+ excess or a shift to darkness, DRAG becomes inactive and DRAT becomes transiently active, resulting in the inactivation of dinitrogenase reductase. Both DRAT and DRAG eventually become inactive in the dark. When cultures are shifted back to the light, DRAG becomes active again and reactivates dinitrogenase reductase (80). The regulation of DRAT and DRAG activities certainly involves PII and therefore must also depend on pools of certain small molecules in the cell (25-27, 66, 70, 80).

An additional reason for expecting to see an effect of lower ATP levels on nitrogenase activity is because of the nature of the nitrogenase enzyme complex itself. Because of the concomitant and obligate reduction of protons to H2, the reduction of N2 to NH3 involves eight electron transfers between dinitrogenase and its terminal electron donor, dinitrogenase reductase (8). Each electron transfer requires the hydrolysis of two ATP molecules by dinitrogenase reductase, so one might suppose that nitrogenase activity would be sensitive to ATP levels even in the absence of the different levels of regulation.

Prior to the analysis of the ATP levels reported in Table 2, the same cultures were analyzed for nitrogenase activity. As shown in Table 3, little nitrogenase activity was seen in the purE mutants when grown in MG without adenine because of very poor growth. When supplemented with 0.05 or 0.1 mM adenine, the purE mutants showed moderate nitrogenase activity and responded normally to dark shift, but poor recovery of nitrogenase activity was seen after the cultures were returned back to light (Table 3). However, these purE mutants showed a normal recovery of nitrogenase activity when grown in MG medium supplemented with 0.5 mM adenine. The initial nitrogenase activity was somewhat lower in the wild type and the purE mutants when they were grown in the presence of 0.5 mM adenine, perhaps because of some indirect adenine inhibition of nitrogenase. This inhibition was seen in the wild type when treated with high levels of adenine (data not shown). Because the ATP assays in Table 2 were performed on the same cultures, we can conclude that limiting adenine caused a dramatic decrease in the ATP concentration, but remarkably little effect on nitrogenase activity. At most, the very low ATP pools do correlate with a poor recovery of nitrogenase activity by the DRAT/DRAG system after restoration of light.

TABLE 3.

Nitrogenase activity and its response to dark-light shifts in R. rubrum purE mutants in MG with different concentrations of adenine

| Adenine concn (mM) and R. rubrum strain | Chromosomal genotype | Nitrogenase activity

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial level (nmol of ethylene/h/ml)a | % Activityb

|

|||

| 40 min, dark | 10 min, light | |||

| 0 | ||||

| UR2 | Wild type | 800 | 13 | 108 |

| UR2187 | purE1::aacC1 | <20 | NT | NT |

| UR2188 | purE2::aacC1 | <20 | NT | NT |

| 0.05 | ||||

| UR2 | Wild type | 700 | 7 | 105 |

| UR2187 | purE1::aacC1 | 450 | 21 | 25 |

| UR2188 | purE2::aacC1 | 550 | 27 | 35 |

| 0.1 | ||||

| UR2 | Wild type | 600 | 10 | 105 |

| UR2187 | purE1::aacC1 | 450 | 20 | 22 |

| UR2188 | purE2::aacC1 | 450 | 25 | 27 |

| 0.5 | ||||

| UR2 | Wild type | 450 | 8 | 104 |

| UR2187 | purE1::aacC1 | 400 | 8 | 97 |

| UR2188 | purE2::aacC1 | 350 | 9 | 94 |

The nitrogenase activity was derepressed in MG medium with different levels of adenine under illumination. Each unit of nitrogenase activity is expressed as the nmol of ethylene produced per h per ml of cells at an optical density at 600 nm of 1. Each activity value is from at least five replicate assays from different individually grown cultures. The standard deviation is about 10 to 15%. Initial levels were considered the 100% levels.

That is, the percentage of the initial nitrogenase activity remaining after a shift to darkness or reillumination (light).

Nitrogenase activity is a measure of the competing activities of DRAT and DRAG, so the failure of these cultures to recover nitrogenase activity after the restoration of light might indicate that the activity of either of these enzymes is altered. The use of a draG mutant has allowed us to study DRAT activity without the interference of DRAG activity (41), so we constructed purE draG double mutants to examine the impact of the ATP pool on DRAT activity alone. Adenine limitation caused substantial amounts of DRAT to be activated under derepression conditions, resulting in the low initial activity in purE draG mutants (Table 4). The low nitrogenase activity is caused by the modification of dinitrogenase reductase by DRAT, as confirmed by Western blots of the protein (data not shown). Thus, DRAT is inappropriately active under these conditions. Because of this result, the relatively high nitrogenase activity in the DraG+ background indicates that DRAG is still active under these conditions. These results indicated that the adenine limitation in purE mutants significantly perturbs the regulation of both DRAT and DRAG activities, although these purE mutants showed moderate nitrogenase activity and appeared to respond to dark shifts normally.

TABLE 4.

Nitrogenase activity in R. rubrum purE draG mutants in MG with different concentrations of adenine

| Adenine concn (mM) and R. rubrum strain | Chromosomal genotype | Nitrogenase activity (nmol of ethylene/h/ml) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.05 | ||

| UR2 | Wild type | 750 |

| UR2187 | purE1::aacC1 | 420 |

| UR2330 | purE1::aacC1 draG4::kan | 80 |

| UR2378 | purE2::aacC1 draG4::kan | 70 |

| 0.1 | ||

| UR2 | Wild type | 650 |

| UR2187 | purE1::aacC1 | 500 |

| UR2330 | purE1::aacC1 draG4::kan | 70 |

| UR2378 | purE2::aacC1 draG4::kan | 70 |

| 0.5 | ||

| UR2 | Wild type | 500 |

| UR2187 | purE1::aacC1 | 400 |

| UR2330 | purE1::aacC1 draG4::kan | <20 |

| UR2378 | purE2::aacC1 draG4::kan | <20 |

The modification of GlnB in response to dark-light shifts in wild type and purE mutants.

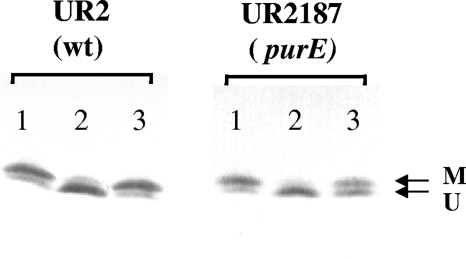

As mentioned in the Introduction, the DRAT/DRAG regulatory system is itself regulated by PII. We therefore monitored the modification of PII state in both the wild type and purE mutants in response to dark-light shifts to test if the low ATP pool in purE mutants has any effect on the PII modification. As shown in Fig. 5, in UR2 (wild type) most GlnB is accumulated in a UMP-modified form under derepression conditions (N-limiting conditions), and it becomes deuridylylated after a shift to darkness. When returned to the light, most GlnB becomes uridylylated again. The pattern of the modification of GlnB is consistent with the current model that PII activates DRAT and inactivates DRAG under nitrogen-excess conditions, while PII-UMP inhibits DRAT and activates DRAG under nitrogen-deficient conditions. The modification of GlnB is consistent with the regulation of nitrogenase and the modification of dinitrogenase activity. Similar to that seen in UR2, most GlnB in the purE mutant (UR2187) is accumulated in the modified form under derepression conditions and it becomes deuridylylated after a shift to darkness. However, only a small part of GlnB becomes modified again after a return to light, which is also consistent with the failure of this mutant to recover nitrogenase activity (Table 3). Similar to the modification of GlnB, the modification of GlnJ was also altered; a poor reuridylylation of GlnJ was also seen in purE mutants after a return to light (data not shown). These results indicate that adenine depletion has significant effects on PII modification, especially on uridylylation after restoration of light. The failure of uridylylation of PII presumably affects its role in the reactivation of DRAG and the restoration of nitrogenase activity after a return to light.

FIG. 5.

Western immunoblots of GlnB in UR2 (wild type) and UR2187 (purE mutant). Cells were grown in MG medium with 0.1 mM adenine for about 2 days, with OD600 at 2.0 to 2.5. Then, 1-ml portions of the same culture were rapidly extracted by TCA precipitation of derepressed cultures of UR2 and UR2187 (lane 1), 60 min after a shift to dark (lane 2), and 10 min after a return to light (lane 3). Protein samples were loaded on low cross-linker SDS-Tricine gels and immunoblotted with antibody to R. rubrum GlnB. Arrow M indicates the position of the modified subunit, and arrow U indicates the position of the unmodified subunit.

DISCUSSION

In some nitrogen-fixing bacteria, such as R. rubrum, A. brasilense and R. capsulatus, nitrogenase activity is regulated not only by the addition of NH4+ but also in response to energy depletion (by a dark shift for R. rubrum and R. capsulatus or an anaerobic shift for A. brasilense) (35, 48, 74, 80). Although the change of ATP levels might be the basis for these effects, previous measurements of the ATP pool yielded inconsistent results. Li et al. reported that the pool of ATP in R. rubrum decreased after the dark shift, stayed at low levels, and then recovered after cells were returned to light (40). However, using a different extraction method, Paul and Ludden saw the pool of ATP increase rapidly after the dark shift and then decrease slightly, but they also reported further ATP fluctuations during dark incubation (56). In response to NH4+ addition, no obvious changes in ATP levels were detected in R. rubrum and K. pneumoniae, although a change was seen with Clostridium pasteurianum (56, 68). However, the ADP/ATP ratio decreased in the latter two organisms when they were switched from N2 to NH4+ as the sole N source (68).

Given our data and the concerns about the analysis of ATP levels noted in the Introduction, it is difficult to know how to interpret the above results. There seems to be no doubt that detected ATP levels are highly dependent on the extraction method used. We therefore favor the luciferase assay, since it minimally perturbs the cells and reports at least some aspect of “available” ATP. This assay also displayed a particular advantage when used with R. rubrum: surprisingly, luciferin appears to be able to rapidly penetrate into R. rubrum cells without any treatment. This is in contrast to the long treatment time (>30 min) with a low concentration of polymyxin B as originally used for E. coli (10), and a shortened treatment at high polymyxin B concentration used subsequently (60). Thus, without the treatment of polymyxin B we are able to monitor rapid changes in the ATP pool in R. rubrum without any potential ATP loss or delay.

When applied to R. rubrum, this method suggests very modest changes in ATP after removal of light and essentially no change after the addition of NH4+. At the very least, this result implies that ATP levels per se are not the critical signal for the dramatic posttranslational regulation of nitrogenase that we monitor.

Our use of purE mutants showed that we could severely perturb ATP levels in vivo, as determined by both luciferase and an extraction method. Indeed, given the striking change in detected ATP pools, it is very surprising to us that moderate nitrogenase activity was seen in purE mutants under these adenine-limiting conditions (ca. 70% of that seen in wild type). This result implies that relatively low levels of ATP are sufficient to maintain a fairly robust flux of electrons through nitrogenase itself, and DRAG is highly active and keeps dinitrogenase reductase in its active form. Indeed, we confirmed the latter point with the use of the purE draG strain. The only apparent flaw in the regulation in these purE mutants under adenine-depletion conditions was their poor recovery of nitrogenase activity after a return to light. A direct analysis of the modification state of PII showed that a substantial fraction of the PII in purE mutants remained in the deuridylylated form after the return to light, whereas PII in the wild type became uridylylated under the same conditions. This indicates that adenine depletion and low ATP levels have significant effects on PII modification, which in turn alters the DRAT/DRAG regulatory system.

The current hypothesis is that both DRAT and DRAG activities are inhibited in vivo by binding different forms of PII proteins. DRAT-PII interaction was observed with yeast two-hybrid system in R. capsulatus and R. rubrum (57, 83). Pull-down experiments with A. brasilense strains overexpressing His-tagged DRAT or DRAG indicated that DRAT binds only unmodified PII and DRAG binds both unmodified and modified PII (25), although recent in vitro studies showed that DRAT can also bind modified PII under some conditions (26). DRAG-PII interaction was observed in vitro as well, although no interaction was seen in the yeast two-hybrid system.

So how might we imagine a role for the relative levels of ADP and ATP in mitigating these activities, even without the change of PII modification state? The formation of DRAG-PII complex is stimulated by ADP, and partially dissociated by either α-KG or ATP (27). The DRAG-PII complex can also interact with membrane protein AmtB, and the membrane sequestration removes DRAG from its substrate, dinitrogenase reductase. The interaction of R. rubrum GlnJ and AmtB1 is also affected by α-KG, ADP, and ATP (71). Thus, competition between ADP and ATP for PII could affect the availability of DRAG to support nitrogenase activity. The case for ADP/ATP effects on DRAT is less clear, but the simple notion is that ADP-bound, but not ATP-bound PII would bind DRAT to stimulate its activity. Under energy excess conditions, where ADP might be low, PII is saturated by ATP and α-KG and is uridylylated by GlnD, and this would lead it to dissociate from DRAT, resulting in the loss of DRAT activity. In the presence of α-KG, either ADP or ATP can support modification of PII, but the behavior of modified PII with ATP- and ADP-bound PII might well be different in terms of interaction with DRAT. Thus, under energy-limiting conditions, PII is likely in the ADP-bound form (modified or not), and it could activate DRAT. We emphasize that these rationalizations are highly speculative and are merely a framework to consider possible ADP/ATP effects.

Although not related to energy-sensing by PII, we also note that a severe lowering of ATP levels has little impact on the electron flux through dinitrogenase. This surprises us because each electron transfer to dinitrogenase requires hydrolysis of two molecules of ATP and might have been expected to be very sensitive to ATP levels. We have no data to address this result, but it is our working hypothesis that the affinity of dinitrogenase reductase for ATP is sufficiently high, so that it competes particularly well for ATP. This result has implications for efforts to enhance H2 production through nitrogenase for bioenergy purposes.

What role does ATP have in modulating PII function in vivo? The simple answer is that ATP cannot be the sole signal, and we suppose that the ratio of ADP/ATP might be the key issue. Although the impact of ATP or the ADP/ATP ratio has not previously been analyzed in vivo, the notion of the ADP/ATP ratio has been supported by a variety of in vitro analyses. Our previous results showed that the interaction of R. rubrum GlnJ and AmtB1 is disrupted by α-KG and/or ATP, while ADP inhibits the destabilization of the GlnJ-AmtB1 complex in the presence of ATP and α-KG. These results support a role for PII as an energy sensor that measures the ratio of ATP to ADP (71). Recently, several lines of in vitro evidence suggest that the ratio of ADP/ATP plays an important role in the interaction of PII with its different receptors in different bacteria. Jiang and Ninfa have shown that ADP has a significant effect on PII function in the regulation of NtrB and GlnE in an in vitro E. coli system, and their results indicate that PII acts as a sensor of both ATP and ADP signals (31). Teixeira et al. found that the interaction of R. rubrum GlnJ with its targets (AmtB1, GlnD, and GlnE) is also dependent on the ratio of ADP/ATP in vitro and that the ADP/ATP ratio can override the α-KG signal (66). Finally, Huergo et al. reported that ATP, ADP, and α-KG play a key role in A. brasilense PII interaction with the DRAT/DRAG regulatory protein in vitro (26). Consistent with an important role for ADP binding by PII, the crystal structures of Thermotoga maritima PII and the E. coli PII-AmtB protein complex show ADP bound to PII even though no ADP was added during crystallization (9, 61).

Unfortunately, we are not in a position to address the level of ADP in the cell under these conditions. The luciferase assay is not useful because it only reports the presence of ATP. Although some extraction methods for ADP have been described, these have technical challenges similar to those for ATP quantitation, with different extraction methods yielding dramatically different ADP values (37, 46). The TCA extraction method is the most effective for extraction of both ATP and ADP. However, the TCA has to be removed by an additional extraction method so the ADP/AMP can be enzymatically converted to ATP. These multiple-step manipulations greatly reduce the reliability of ADP quantitation. Thus, we are skeptical that values from these analyses are informative.

In conclusion, the data show that removal and restoration of light to cultures of R. rubrum has dramatic effects on nitrogenase activity and the modification status of PII, but the plausible hypothesis that these effects reflect a change in ATP levels seems to be incorrect. It is therefore our working hypothesis, based primarily on the in vitro analyses noted above, that either ADP levels or the ADP/ATP ratio is the primary metabolic signal, although a completely new method of analysis will be necessary to test that hypothesis. We also saw that a dramatic lowering of ATP in the purE mutants had little impact on nitrogenase activity, suggesting that this system is surprisingly effective in competing with other ATP-utilizing systems in the cell.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the College of Agricultural and Life Sciences, University of Wisconsin-Madison, and NIGMS grant GM65891 to G.P.R.

We thank Richard Gourse and Tamas Gaal for generously providing the luc plasmid and the TD-20/20 luminometer for the luciferase assay, Mary Conrad and Jose Serate for the purification of GlnB, and David Wolfe and Emily Welch for valuable criticisms of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 19 June 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arcondéguy, T., R. Jack, and M. Merrick. 2001. PII signal transduction proteins, pivotal players in microbial nitrogen control. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 6580-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arsene, F., P. A. Kaminski, and C. Elmerich. 1996. Modulation of NifA activity by PII in Azospirillum brasilense: evidence for a regulatory role of the NifA N-terminal domain. J. Bacteriol. 1784830-4838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atlante, A., S. Giannattasio, A. Bobba, S. Gagliardi, V. Petragallo, P. Calissano, E. Marra, and S. Passarella. 2005. An increase in the ATP levels occurs in cerebellar granule cells en route to apoptosis in which ATP derives from both oxidative phosphorylation and anaerobic glycolysis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 170850-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benelli, E. M., E. M. Souza, S. Funayama, L. U. Rigo, and F. O. Pedrosa. 1997. Evidence for two possible glnB-type genes in Herbaspirillum seropedicae. J. Bacteriol. 1794623-4626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowers, K. C., A. P. Allshire, and P. H. Cobbold. 1992. Bioluminescent measurement in single cardiomyocytes of sudden cytosolic ATP depletion coincident with rigor. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 24213-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Branchini, B. R., R. A. Magyar, M. H. Murtiashaw, S. M. Anderson, and M. Zimmer. 1998. Site-directed mutagenesis of histidine 245 in firefly luciferase: a proposed model of the active site. Biochemistry 3715311-15319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burgener, A., K. Coombs, and M. Butler. 2006. Intracellular ATP and total adenylate concentrations are critical predictors of reovirus productivity from Vero cells. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 94667-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burris, R. H. 1991. Nitrogenases. J. Biol. Chem. 2669339-9342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conroy, M. J., A. Durand, D. Lupo, X. D. Li, P. A. Bullough, F. K. Winkler, and M. Merrick. 2007. The crystal structure of the Escherichia coli AmtB-GlnK complex reveals how GlnK regulates the ammonia channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1041213-1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dement'eva, E. I., N. N. Ugarova, and P. H. Cobbold. 1996. Measurement of ATP in intact Escherichia coli cells, containing recombinant firefly luciferase. Biokhimiia 611285-1293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dennis, P. B., A. Jaeschke, M. Saitoh, B. Fowler, S. C. Kozma, and G. Thomas. 2001. Mammalian TOR: a homeostatic ATP sensor. Science 2941102-1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Zamaroczy, M., A. Paquelin, G. Peltre, K. Forchhammer, and C. Elmerich. 1996. Coexistence of two structurally similar but functionally different PII proteins in Azospirillum brasilense. J. Bacteriol. 1784143-4149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dhar-Chowdhury, P., B. Malester, P. Rajacic, and W. A. Coetzee. 2007. The regulation of ion channels and transporters by glycolytically derived ATP. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 643069-3083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Di Tomaso, G., R. Borghese, and D. Zannoni. 2001. Assay of ATP in intact cells of the facultative phototroph Rhodobacter capsulatus expressing recombinant firefly luciferase. Arch. Microbiol. 17711-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ditta, G., T. Schmidhauser, E. Yakobson, P. Lu, X.-W. Liang, D. R. Finlay, D. Guiney, and D. R. Helinski. 1985. Plasmids related to the broad host range vector, pRK290, useful for gene cloning and for monitoring gene expression. Plasmid 13149-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dodsworth, J. A., N. C. Cady, and J. A. Leigh. 2005. 2-Oxoglutarate and the PII homologues NifI1 and NifI2 regulate nitrogenase activity in cell extracts of Methanococcus maripaludis. Mol. Microbiol. 561527-1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dodsworth, J. A., and J. A. Leigh. 2006. Regulation of nitrogenase by 2-oxoglutarate-reversible, direct binding of a PII-like nitrogen sensor protein to dinitrogenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1039779-9784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drepper, T., S. Gross, A. F. Yakunin, P. C. Hallenbeck, B. Masepohl, and W. Klipp. 2003. Role of GlnB and GlnK in ammonium control of both nitrogenase systems in the phototrophic bacterium Rhodobacter capsulatus. Microbiology 1492203-2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fitzmaurice, W. P., L. L. Saari, R. G. Lowery, P. W. Ludden, and G. P. Roberts. 1989. Genes coding for the reversible ADP-ribosylation system of dinitrogenase reductase from Rhodospirillum rubrum. Mol. Gen. Genet. 218340-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forchhammer, K. 2008. PII signal transducers: novel functional and structural insights. Trends Microbiol. 1665-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fu, H. A., A. Hartmann, R. G. Lowery, W. P. Fitzmaurice, G. P. Roberts, and R. H. Burris. 1989. Posttranslational regulatory system for nitrogenase activity in Azospirillum spp. J. Bacteriol. 1714679-4685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Funabashi, H., T. Imajo, J. Kojima, E. Kobatake, and M. Aizawa. 1999. Bioluminescent monitoring of intracellular ATP during fermentation. Luminescence 14291-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grunwald, S. K., D. P. Lies, G. P. Roberts, and P. W. Ludden. 1995. Posttranslational regulation of nitrogenase in Rhodospirillum rubrum strains overexpressing the regulatory enzymes dinitrogenase reductase ADP-ribosyltransferase and dinitrogenase reductase activating glycohydrolase. J. Bacteriol. 177628-635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He, L., E. Soupene, A. Ninfa, and S. Kustu. 1998. Physiological role for the GlnK protein of enteric bacteria: relief of NifL inhibition under nitrogen-limiting conditions. J. Bacteriol. 1806661-6667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huergo, L. F., L. S. Chubatsu, E. M. Souza, F. O. Pedrosa, M. B. R. Steffens, and M. Merrick. 2006. Interactions between PII proteins and the nitrogenase regulatory enzymes DraT and DraG in Azospirillum brasilense. FEBS Lett. 5805232-5236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huergo, L. F., M. Merrick, R. A. Monteiro, L. S. Chubatsu, M. B. R. Steffens, F. O. Pedrosa, and E. M. Souza. 2009. In vitro interactions between the PII proteins and the nitrogenase regulatory enzymes dinitrogenase reductase ADP-ribosyltransferase (DraT) and dinitrogenase reductase-activating glycohydrolase (DraG) in Azospirillum brasilense. J. Biol. Chem. 2846674-6682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huergo, L. F., M. Merrick, F. O. Pedrosa, L. S. Chubatsu, M. S. Araujo, and E. M. Souza. 2006. Ternary complex formation between AmtB, GlnZ and the nitrogenase regulatory enzyme DraG reveals a novel facet of nitrogen regulation in bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 661523-1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huergo, L. F., E. M. Souza, M. S. Araujo, F. O. Pedrosa, L. S. Chubatsu, M. B. R. Steffens, and M. Merrick. 2006. ADP-ribosylation of dinitrogenase reductase in Azospirillum brasilense is regulated by AmtB-dependent membrane sequestration of DraG. Mol. Microbiol. 59326-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jack, R., M. De Zamaroczy, and M. Merrick. 1999. The signal transduction protein GlnK is required for NifL-dependent nitrogen control of nif gene expression in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 1811156-1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jensen, K. F., U. Houlberg, and P. Nygaard. 1979. Thin-layer chromatographic methods to isolate 32P-labeled 5-phosphoribosyl-α-1-pyrophosphate (PRPP): determination of cellular PRPP pools and assay of PRPP synthetase activity. Anal. Biochem. 98254-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang, P., and A. J. Ninfa. 2007. Escherichia coli PII signal transduction protein controlling nitrogen assimilation acts as a sensor of adenylate energy charge in vitro. Biochemistry 4612979-12996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang, P., J. A. Peliska, and A. J. Ninfa. 1998. Enzymological characterization of the signal-transducing uridylyltransferase/uridylyl-removing enzyme (EC 2.7.7.59) of Escherichia coli and its interaction with the PII protein. Biochemistry 3712782-12794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jonsson, A., and S. Nordlund. 2007. In vitro studies of the uridylylation of the three PII protein paralogs from Rhodospirillum rubrum: the transferase activity of R. rubrum GlnD is regulated by α-ketoglutarate and divalent cations but not by glutamine. J. Bacteriol. 1893471-3478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kamberov, E. S., M. R. Atkinson, and A. J. Ninfa. 1995. The Escherichia coli PII signal transduction protein is activated upon binding 2-ketoglutarate and ATP. J. Biol. Chem. 27017797-17807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kanemoto, R. H., and P. W. Ludden. 1984. Effect of ammonia, darkness, and phenazine methosulfate on whole-cell nitrogenase activity and Fe protein modification in Rhodospirillum rubrum. J. Bacteriol. 158713-720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koop, A., and P. H. Cobbold. 1993. Continuous bioluminescent monitoring of cytoplasmic ATP in single isolated rat hepatocytes during metabolic poisoning. Biochem. J. 295165-170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Larsson, C.-M., and T. Olsson. 1979. Firefly assay of adenine nucleotides from algae: comparison of extraction methods. Plant Cell Physiol. 20145-155. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lehman, L. J., and G. P. Roberts. 1991. Identification of an alternative nitrogenase system in Rhodospirillum rubrum. J. Bacteriol. 1735705-5711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leigh, J. A., and J. A. Dodsworth. 2007. Nitrogen regulation in bacteria and archaea. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 61349-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li, J. D., C. Z. Hu, and D. C. Yoch. 1987. Changes in amino acid and nucleotide pools of Rhodospirillum rubrum during switch-off of nitrogenase activity initiated by NH4+ or darkness. J. Bacteriol. 169231-237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liang, J. H., G. M. Nielsen, D. P. Lies, R. H. Burris, G. P. Roberts, and P. W. Ludden. 1991. Mutations in the draT and draG genes of Rhodospirillum rubrum result in loss of regulation of nitrogenase by reversible ADP-ribosylation. J. Bacteriol. 1736903-6909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lies, D. P. 1994. Genetic manipulation and the overexpression analysis of posttranslational nitrogen fixation regulation in Rhodospirillum rubrum. Ph.D. thesis. University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison.

- 43.Little, R., and H. Bremer. 1982. Quantitation of guanosine 5′,3′-bisdiphosphate in extracts from bacterial cells by ion-pair reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal. Biochem. 126381-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Little, R., V. Colombo, A. Leech, and R. Dixon. 2002. Direct interaction of the NifL regulatory protein with the GlnK signal transducer enables the Azotobacter vinelandii NifL-NifA regulatory system to respond to conditions replete for nitrogen. J. Biol. Chem. 27715472-15481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Little, R., F. Reyes-Ramirez, Y. Zhang, W. C. van Heeswijk, and R. Dixon. 2000. Signal transduction to the Azotobacter vinelandii NIFL-NIFA regulatory system is influenced directly by interaction with 2-oxoglutarate and the PII regulatory protein. EMBO J. 196041-6050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lundin, A., and A. Thore. 1975. Comparison of methods for extraction of bacterial adenine nucleotides determined by firefly assay. Appl. Microbiol. 30713-721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martin, D. E., T. Hurek, and B. Reinhold-Hurek. 2000. Occurrence of three PII-like signal transmitter proteins in the diazotrophic proteobacterium Azoarcus sp. BH72. Mol. Microbiol. 38276-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Masepohl, B., T. Drepper, A. Paschen, S. Gross, A. Pawlowski, K. Raabe, K. U. Riedel, and W. Klipp. 2002. Regulation of nitrogen fixation in the phototrophic purple bacterium Rhodobacter capsulatus. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 4243-248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Masepohl, B., R. Krey, and W. Klipp. 1993. The draTG gene region of Rhodobacter capsulatus is required for posttranslational regulation of both the molybdenum and the alternative nitrogenase. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1392667-2675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mueller, E. J., E. Meyer, J. Rudolph, V. J. Davisson, and J. Stubbe. 1994. N5-carboxyaminoimidazole ribonucleotide: evidence for a new intermediate and two new enzymatic activities in the de novo purine biosynthetic pathway of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 332269-2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ninfa, A. J., and M. R. Atkinson. 2000. PII signal transduction proteins. Trends Microbiol. 8172-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nordlund, S., and L. Höglund. 1986. Studies of the adenylate and pyridine nucleotide pools during nitrogenase ‘switch-off’ in Rhodospirillum rubrum. Plant Soil. 90203-209. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nordlund, S., and P. W. Ludden. 2004. Post-translational regulation of nitorgenase in photosynthetic bacteria, p. 175-196. In W. Klipp, B. Masepohl, J. R. Gallon, and W. E. Newton (ed.), Genetics and regulation of nitrogen fixation in free-living bacteria. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

- 54.Ohmori, M., and A. Hattori. 1978. Transient change in the ATP pool of Anabaena cylindrica associated with ammonia assimilation. Arch. Microbiol. 11717-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Palmfeldt, J., M. Paese, B. Hahn-Hagerdal, and E. W. Van Niel. 2004. The pool of ADP and ATP regulates anaerobic product formation in resting cells of Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 705477-5484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paul, T. D., and P. W. Ludden. 1984. Adenine nucleotide levels in Rhodospirillum rubrum during switch-off of whole-cell nitrogenase activity. Biochem. J. 224961-969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pawlowski, A., K. U. Riedel, W. Klipp, P. Dreiskemper, S. Groβ, H. Bierhoff, T. Drepper, and B. Masepohl. 2003. Yeast two-hybrid studies on interaction of proteins involved in regulation of nitrogen fixation in the phototrophic bacterium Rhodobacter capsulatus. J. Bacteriol. 1855240-5247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schägger, H., and G. von Jagow. 1987. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal. Biochem. 166368-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schneider, D. A., T. Gaal, and R. L. Gourse. 2002. NTP-sensing by rRNA promoters in Escherichia coli is direct. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 998602-8607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schneider, D. A., and R. L. Gourse. 2004. Relationship between growth rate and ATP concentration in Escherichia coli: a bioassay for available cellular ATP. J. Biol. Chem. 2798262-8268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schwarzenbacher, R., F. von Delft, P. Abdubek, E. Ambing, T. Biorac, L. S. Brinen, J. M. Canaves, J. Cambell, H. J. Chiu, X. Dai, et al. 2004. Crystal structure of a putative PII-like signaling protein (TM0021) from Thermotoga maritima at 2.5 Å resolution. Proteins 54810-813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schweizer, H. P. 1993. Small broad-host-range gentamycin resistance gene cassettes for site-specific inserrtion and deletion mutagenesis. BioTechniques 15831-834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shapiro, B. M., and E. R. Stadtman. 1968. Glutamine synthetase deadenylylating enzyme. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 3032-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Simon, R., U. B. Priefer, and A. Pühler. 1983. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in gram-negative bacteria. Bio/Technology 1784-791. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stadtman, E. R. 2001. The story of glutamine synthetase regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 27644357-44364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Teixeira, P. F., A. Jonsson, M. Frank, H. Wang, and S. Nordlund. 2008. Interaction of the signal transduction protein GlnJ with the cellular targets AmtB1, GlnE, and GlnD in Rhodospirillum rubrum: dependence on manganese, 2-oxoglutarate, and the ADP/ATP ratio. Microbiology 1542336-2347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tremblay, P. L., T. Drepper, B. Masepohl, and P. C. Hallenbeck. 2007. Membrane sequestration of PII proteins and nitrogenase regulation in the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodobacter capsulatus. J. Bacteriol. 1895850-5859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Upchurch, R. G., and L. E. Mortenson. 1980. In vivo energetics and control of nitrogen fixation: changes in the adenylate energy charge and adenosine 5′-diphosphate/adenosine 5′-triphosphate ratio of cells during growth on dinitrogen versus growth on ammonia. J. Bacteriol. 143274-284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.van Heeswijk, W. C., S. Hoving, D. Molenaar, B. Stegeman, D. Kahn, and H. V. Westerhoff. 1996. An alternative PII protein in the regulation of glutamine synthetase in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 21133-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang, H., C. C. Franke, S. Nordlund, and A. Norén. 2005. Reversible membrane association of dinitrogenase reductase activating glycohydrolase in the regulation of nitrogenase activity in Rhodospirillum rubrum; dependence on GlnJ and AmtB1. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 253273-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wolfe, D. M., Y. Zhang, and G. P. Roberts. 2007. Specificity and regulation of interaction between the PII and AmtB1 proteins in Rhodospirillum rubrum. J. Bacteriol. 1896861-6869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang, Y., R. H. Burris, P. W. Ludden, and G. P. Roberts. 1995. Comparison studies of dinitrogenase reductase ADP-ribosyl transferase/dinitrogenase reductase activating glycohydrolase regulatory systems in Rhodospirillum rubrum and Azospirillum brasilense. J. Bacteriol. 1772354-2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang, Y., R. H. Burris, P. W. Ludden, and G. P. Roberts. 1993. Posttranslational regulation of nitrogenase activity by anaerobiosis and ammonium in Azospirillum brasilense. J. Bacteriol. 1756781-6788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang, Y., R. H. Burris, P. W. Ludden, and G. P. Roberts. 1997. Regulation of nitrogen fixation in Azospirillum brasilense. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 152195-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang, Y., M. Morar, and S. E. Ealick. 2008. Structural biology of the purine biosynthetic pathway. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 653699-3742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang, Y., E. L. Pohlmann, M. C. Conrad, and G. P. Roberts. 2006. The poor growth of Rhodospirillum rubrum mutants lacking PII proteins is due to an excess of glutamine synthetase activity. Mol. Microbiol. 61497-510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang, Y., E. L. Pohlmann, C. M. Halbleib, P. W. Ludden, and G. P. Roberts. 2001. Effect of PII and its homolog GlnK on reversible ADP-ribosylation of dinitrogenase reductase by heterologous expression of the Rhodospirillum rubrum dinitrogenase reductase ADP-ribosyl transferase-dinitrogenase reductase-activating glycohydrolase regulatory system in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 1831610-1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhang, Y., E. L. Pohlmann, P. W. Ludden, and G. P. Roberts. 2001. Functional characterization of three GlnB homologs in the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodospirillum rubrum: roles in sensing ammonium and energy status. J. Bacteriol. 1836159-6168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang, Y., E. L. Pohlmann, P. W. Ludden, and G. P. Roberts. 2000. Mutagenesis and functional characterization of the glnB, glnA, and nifA genes from the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodospirillum rubrum. J. Bacteriol. 182983-992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhang, Y., E. L. Pohlmann, P. W. Ludden, and G. P. Roberts. 2003. Regulation of nitrogen fixation by multiple PII homologs in the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodospirillum rubrum. Symbiosis 3585-100. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhang, Y., E. L. Pohlmann, and G. P. Roberts. 2004. Identification of critical residues in GlnB for its activation of NifA activity in the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodospirillum rubrum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1012782-2787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhang, Y., D. M. Wolfe, E. L. Pohlmann, M. C. Conrad, and G. P. Roberts. 2006. Effect of AmtB homologs on the posttranslational regulation of nitrogenase activity in response to ammonium and energy signals in Rhodospirillum rubrum. Microbiology 1522075-2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhu, Y., M. C. Conrad, Y. Zhang, and G. P. Roberts. 2006. Identification of Rhodospirillum rubrum GlnB variants that are altered in their ability to interact with different targets in response to nitrogen-status signals. J. Bacteriol. 1881866-1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]