Abstract

PCR primers targeting loci in the current Burkholderia cepacia complex multilocus sequence typing scheme were redesigned to (i) more reliably amplify these loci from B. cepacia complex species, (ii) amplify these same loci from additional Burkholderia species, and (iii) enable the use of a single primer set per locus for both amplification and DNA sequencing.

The multilocus sequence typing (MLST) scheme for the Burkholderia cepacia complex has provided important insights into the population dynamics, diversity, and recombination events in this group of opportunistic pathogens (1-3, 7). It has also been effective in identifying previously misclassified strains and has proved useful in the recent identification of seven novel species in the B. cepacia complex (9, 10). This expansion of the B. cepacia complex and our growing appreciation that other Burkholderia species, particularly B. gladioli, are also involved in human infection, provide an opportunity to expand the capacity of the current MLST scheme. We thus sought to redesign the primers targeting the loci in the current MLST scheme to (i) more reliably amplify these seven loci from all 17 B. cepacia complex species; (ii) amplify these loci from additional Burkholderia species, including B. gladioli and as yet unclassified Burkholderia species; and (iii) enable the use of a single primer set per locus for both amplification and DNA sequencing.

We aligned all seven loci (atpD, gltB, gyrB, lepA, phaC, recA, and trpB) in the current MLST scheme from Burkholderia strains for which complete genome sequences were available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/lproks.cgi) or Joint Genome Institute (http://www.jgi.doe.gov/genome-projects/) database. These strains included Burkholderia ambifaria AMMD, B. cenocepacia J2315, B. cenocepacia AU1054, B. cenocepacia PC184, B. multivorans ATCC 17616, B. vietnamiensis G4, B. dolosa AU0158, B. xenovorans LB400, B. phymatum STM815, B. phytofirmans PsJN, B. mallei ATCC 23344, Burkholderia sp. strain 383, and Burkholderia sp. strain H160. Open reading frames were aligned by using MegAlign (DNASTAR Inc., Madison, Wis.), and Burkholderia genus-level primers were designed to amplify sequences that include the regions amplified by the original MLST primers (3) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primer sequences and annealing temperatures for the amplification and sequencing of seven MLST loci for Burkholderia species

| Gene | Amplicon size (bp) | Primer sequence (5′→3′) | Annealing temp (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| atpD | 756 | ATGAGTACTRCTGCTTTGGTAGAAGG | 56 |

| CGTGAAACGGTAGATGTTGTCG | |||

| gltB | 652 | CTGCATCATGATGCGCAAGTG | 58 |

| CTTGCCGCGGAARTCGTTGG | |||

| gyrB | 738 | ACCGGTCTGCAYCACCTCGT | 60 |

| YTCGTTGWARCTGTCGTTCCACTGC | |||

| lepA | 975 | CTSATCATCGAYTCSTGGTTCG | 55 |

| CGRTATTCCTTGAACTCGTARTCC | |||

| phaC | 525 | GCACSAGYATYTGCCAGCG | 58 |

| CCATSTCSGTRCCRATGTAGCC | |||

| recA | 704 | AGGACGATTCATGGAAGAWAGC | 58 |

| GACGCACYGAYGMRTAGAACTT | |||

| trpB | 787 | CGCGYTTCGGVATGGARTG | 58 |

| ACSGTRTGCATGTCCTTGTCG |

To test the utility and range of the new primers, we performed MLST analysis on strains representing multiple Burkholderia species. Strains were obtained from the strain collections of the Burkholderia cepacia Research Laboratory and Repository (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI) and Cardiff University (Cardiff, Wales, United Kingdom). Bacteria were cultured and lysed as described previously (4). Briefly, a single bacterial colony was suspended in 20 μl of lysis buffer containing 0.25% (vol/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate and 0.05 N NaOH. After the suspension was heated for 15 min at 95°C, 180 μl of high-performance liquid chromatography-grade H2O was added, and the bacterial lysate suspension was stored at 4°C. Amplification of targeted DNA was performed in 25-μl reaction mixture volumes containing a final concentration of 2 mM MgCl2, 20 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM KCl, 250 μM of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (ISC Bioexpress, Kaysville, UT), 0.4 μM of each primer, 1 M betaine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma-Aldrich), 2 U Taq polymerase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and 2 μl of bacterial lysate. Amplification was performed with a PTC-100 (MJ Research Inc., Waltham, MA) thermocycler. After an initial denaturation step of 2 min at 95°C, 30 PCR cycles were completed, each PCR cycle consisting of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at the appropriate annealing temperature (Table 1), and 60 s at 72°C, followed by a final extension step of 5 min at 72°C. Sequence analysis and editing of the amplified DNA were performed as previously described (8).

Each distinct sequence (allele) at each of the seven loci was assigned a unique arbitrary number (allele type). For each allelic profile (considered to be isogenic when they were indistinguishable at all seven loci), a unique arbitrary sequence type number was assigned. All sequences were deposited in the Burkholderia cepacia complex MLST database at http://pubmlst.org/bcc. Pairwise analysis using Clustal V (DNAStar) was employed to construct gene trees of the concatenated sequences of all distinct sequence types.

To confirm that the new primers more reliably amplify MLST loci from B. cepacia complex strains, we successfully amplified 43 loci (7 atpD loci, 10 gltB loci, 17 gyrB loci, 2 lepA loci, 3 phaC loci, 2 recA loci, and 2 trpB loci) from 25 B. cepacia complex strains that previously had failed to amplify with the primers and PCR conditions described for the original B. cepacia complex MLST scheme (3) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). To assess the utility of the new primers at the genus level, we amplified all seven loci from 80 strains representing 36 named Burkholderia species (including 16 of the 17 B. cepacia complex species) as well as another 14 Burkholderia strains that remain unclassified with respect to species (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). In all cases, the new genus-level primer sets provided PCR products of the expected size that were confirmed as the intended target by DNA sequence analyses.

The original B. cepacia complex MLST scheme was designed at a time when the B. cepacia complex was comprised of nine species and the complete genome sequences of only three B. cepacia complex strains were available (3). The B. cepacia complex now includes 17 distinct species, and a total of 68 Burkholderia strains have had or are in the process of having their genome sequences determined; at least 16 of these strains represent species within the B. cepacia complex. This expanded Burkholderia taxonomy and the marked increase in Burkholderia genome sequence information have provided an opportunity to address shortcomings in the original MLST methodology. Most problematic is that the original PCR primers fail to amplify the intended target from a significant minority of B. cepacia complex strains. Indeed, we have found that approximately 10% of B. cepacia complex strains analyzed included at least one locus that could not be amplified by using the original MLST primers (data not shown). Commonly, such failures involve strains from the more recently described B. cepacia complex species; however, loci in strains belonging to the older B. cepacia complex species (e.g., B. multivorans and B. cenocepacia) have also failed to amplify with these primers. The original B. cepacia complex MLST method also employed two sets of oligonucleotide primers per locus: one pair to amplify the target locus and a second internal nested pair for DNA sequencing. This approach is advantageous in allowing greater flexibility in designing sequencing primers when the genetic diversity of the targeted loci is unclear. However, the greater Burkholderia genome sequence data now available allowed the design of a single set of primers for both amplification and sequencing.

The MLST primers described herein were specifically designed to amplify sequences that include the regions amplified by the original MLST primers. Therefore, the new primers provide results that are entirely compatible with the current B. cepacia complex MLST scheme. These primers were also designed to amplify larger regions (50 bp to 200 bp) of DNA flanking the loci included in the original MLST scheme. This allows a single PCR per locus to amplify a region with enough flanking DNA to provide high-quality sequence read coverage of the target of interest. The redesigned primers and PCR conditions also improve the performance of MLST for B. cepacia complex species; we observed no loci that failed to amplify with the new primers and PCR conditions, including several from a set of 25 B. cepacia complex strains that failed to amplify with the original B. cepacia complex MLST primers. A potential disadvantage of the new primers and PCR conditions, however, is that since not all loci are amplified with the same annealing temperatures (Table 1), complete MLST analysis cannot be performed with a single PCR run.

The use of degenerate primers allowed expansion of the B. cepacia complex MLST scheme to include analysis of other Burkholderia species, including the clinically relevant species B. gladioli, B. mallei, and B. pseudomallei, as well as species important in agriculture and the environmental sciences, such as B. fungorum, B. glumae, and B. plantarii. Given their degenerate design, however, it is unlikely that these primers are specific only for Burkholderia species; further testing of a broader range of related genera is required in this regard. MLST analysis of B. mallei and B. pseudomallei may also be performed by using a previously described scheme that includes two of the seven target genes (gltB and lepA) in the B. cepacia complex MLST scheme (5).

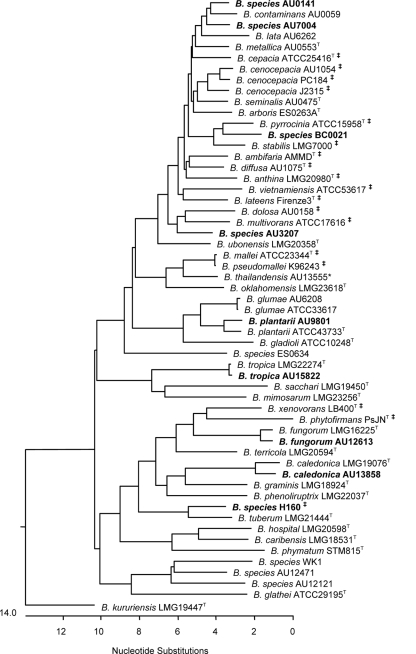

We included in our analysis four Burkholderia strains that previous analyses, including recA and 16S rRNA gene sequencing, indicated were members of the B. cepacia complex but could not be placed into any of the 17 named species in this group. MLST analysis of these strains (AU0141, AU7004, BC0021, and AU3207; Fig. 1) supports their taxonomic position within the B. cepacia complex and their status as being currently unclassified with respect to species. We also included four strains (AU9801, AU15822, AU12613, and AU13858; Fig. 1) that were recovered from patient specimens and previously identified to the Burkholderia genus level by 16S rRNA-directed PCR analyses (6). MLST analysis of strains AU9801, AU15822, AU12613, and AU13858 provided tentative assignment as Burkholderia plantarii, B. tropica, B. fungorum, and B. caledonica, respectively. These species are rarely recovered from infected humans, and all were initially misidentified by commercial phenotype-based identification systems. The analysis of clinical isolates representing potentially novel B. cepacia complex species and Burkholderia species that are rarely encountered from human specimens highlights the utility and expanded capacity of the revised MLST scheme.

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic tree of concatenated nucleotide sequences from the seven MLST loci, generated by using Clustal V. Burkholderia strains included are representatives of the strain set analyzed as part of this study (see supplemental material) or strains for which genome sequence data were available in public databases (indicated by ‡ symbol). Burkholderia strains in bold type are discussed in the text. Strains belonging to various Burkholderia species and Burkholderia sp. strains are shown.

Finally, our study also revealed a potential limitation to the Burkholderia MLST scheme that has not been described in previous studies. Amplification and sequence analysis of the phaC locus in Burkholderia sp. strain H160 suggested the presence of two copies of this gene. In silico analysis of the draft genome sequence of this strain (currently being sequenced by the Joint Genome Institute [http://genome.jgi-psf.org]) confirmed the presence of two phaC homologues with 83% sequence identity, one on each of the two replicons of this genome. The presence of multiple copies, which may not be 100% identical, of any MLST locus confounds the interpretation of results and could limit the utility of this method for epidemiologic and population genetic studies. This finding also highlights a limitation of applying MLST analysis to genetically plastic bacterial species in which large-scale genetic rearrangements, which may or may not be apparent by MLST, are possible. Depending on the questions being addressed, other genotyping methods that provide a more comprehensive assessment of the whole bacterial genome may complement MLST analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the U.S. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. A. Baldwin, C. G. Dowson, and E. Mahenthiralingam acknowledge the United Kingdom Cystic Fibrosis Trust (grant PJ 535) and the Wellcome Trust (grant 072853) for funding their MLST-based research. A. Baldwin was also supported by the Medical Research Fund (United Kingdom).

We are indebted to the patients with cystic fibrosis, their families, and the cystic fibrosis care centers, without whose commitment to cystic fibrosis research this report would not have been possible.

None of the authors has financial interests to declare.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 3 June 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jcm.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baldwin, A., E. Mahenthiralingam, P. Drevinek, C. Pope, D. J. Waine, D. A. Henry, D. P. Speert, P. Carter, P. Vandamme, J. J. LiPuma, and C. G. Dowson. 2008. Elucidating global epidemiology of Burkholderia multivorans in cases of cystic fibrosis by multilocus sequence typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46290-295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baldwin, A., E. Mahenthiralingam, P. Drevinek, P. Vandamme, J. R. Govan, D. J. Waine, J. J. LiPuma, L. Chiarini, C. Dalmastri, D. A. Henry, D. P. Speert, D. Honeybourne, M. C. Maiden, and C. G. Dowson. 2007. Environmental Burkholderia cepacia complex isolates in human infections. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 13458-461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baldwin, A., E. Mahenthiralingam, K. M. Thickett, D. Honeybourne, M. C. Maiden, J. R. Govan, D. P. Speert, J. J. LiPuma, P. Vandamme, and C. G. Dowson. 2005. Multilocus sequence typing scheme that provides both species and strain differentiation for the Burkholderia cepacia complex. J. Clin. Microbiol. 434665-4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coenye, T., and J. J. LiPuma. 2002. Multilocus restriction typing: a novel tool for studying global epidemiology of Burkholderia cepacia complex infection in cystic fibrosis. J. Infect. Dis. 1851454-1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Godoy, D., G. Randle, A. J. Simpson, D. M. Aanensen, T. L. Pitt, R. Kinoshita, and B. G. Spratt. 2003. Multilocus sequence typing and evolutionary relationships among the causative agents of melioidosis and glanders, Burkholderia pseudomallei and Burkholderia mallei. J. Clin. Microbiol. 412068-2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.LiPuma, J. J., B. J. Dulaney, J. D. McMenamin, P. W. Whitby, T. L. Stull, T. Coenye, and P. Vandamme. 1999. Development of rRNA-based PCR assays for identification of Burkholderia cepacia complex isolates recovered from cystic fibrosis patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 373167-3170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahenthiralingam, E., A. Baldwin, P. Drevinek, E. Vanlaere, P. Vandamme, J. J. LiPuma, and C. G. Dowson. 2006. Multilocus sequence typing breathes life into a microbial metagenome. PLoS One 1e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spilker, T., T. Coenye, P. Vandamme, and J. J. LiPuma. 2004. PCR-based assay for differentiation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from other Pseudomonas species recovered from cystic fibrosis patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 422074-2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vanlaere, E., A. Baldwin, D. Gevers, D. Henry, E. De Brandt, J. J. LiPuma, E. Mahenthiralingam, D. P. Speert, C. Dowson, and P. Vandamme. 2009. Taxon K, a complex within the Burkholderia cepacia complex, comprises at least two novel species, Burkholderia contaminans sp. nov. and Burkholderia lata sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 59102-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vanlaere, E., J. J. Lipuma, A. Baldwin, D. Henry, E. De Brandt, E. Mahenthiralingam, D. Speert, C. Dowson, and P. Vandamme. 2008. Burkholderia latens sp. nov., Burkholderia diffusa sp. nov., Burkholderia arboris sp. nov., Burkholderia seminalis sp. nov. and Burkholderia metallica sp. nov., novel species within the Burkholderia cepacia complex. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 581580-1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.